Résumés

Summary

This paper presents a structurationnist analysis model that aims to revise the classic industrial relations theories. The model, primarily based on the re-definition of the notion of actor in industrial relations (Bellemare, 2000), proposes to reconsider the frontiers of the industrial relations system (Bellemare and Briand, 2006; Legault and Bellemare, 2008), to replace the notion of “system” by the concept of “region,“ and to extend the model to the study of issues related to “life politics” (Giddens, 1991).

The proposed model is illustrated by the study of the influence of users/patients on the work organization and on the decisions of the governing bodies of a French university hospital, and on the French health system (public policies, research priorities and methods, etc.).

The results of the study show that the users/patients have become actors in the work relation regions through their mobilization on issues related to life politics: they have challenged the border between expert knowledge and common knowledge, and they have gained greater control over their health and the care they receive. Patients’ associations and individual patients, for their part, have modified the work relations regions at the organizational and worksite levels.

Our results pave the way for future investigations that will integrate the dynamic conceptions of “actor” and of “regions of work relationships,“ as well as issues related to the life politics, in order to validate the generalizing scope of the model proposed.

Keywords:

- industrial relations,

- users/patients,

- life politics,

- work organization,

- health system,

- new actors,

- work relations regions

Résumé

Ce texte présente un modèle d’analyse structurationniste qui, partant d’une re-définition de la notion d’acteur en relations industrielles (Bellemare, 2000), propose de reconsidérer les frontières des systèmes de relations industrielles (Bellemare et Briand, 2006; Legault et Bellemare, 2008) en substituant la notion de « région » à celle de « système », et en élargissant le modèle à l’étude des enjeux liés au champ politique de la vie (Giddens, 1991).

Ce modèle est illustré dans le cadre d’une étude de l’influence des usagers/patients portant sur l’organisation du travail, les décisions des instances de gouvernance d’un hôpital universitaire français, ainsi que le système de santé de manière générale (politiques publiques, priorités et modalités de la recherche, etc.).

Les résultats de cette étude montrent que les usagers/patients sont devenus des acteurs des « régions de rapports de travail » par le biais de leur mobilisation autour des enjeux liés au champ politique de la vie : ils ont contesté la frontière entre le savoir expert et le savoir profane et, ainsi, ils se sont approprié un plus grand contrôle sur leur santé et les soins qui leur sont prodigués. Les associations de patients, tout comme les patients à un niveau individuel, ont, pour leur part, modifié les « régions de relations de travail » au niveau organisationnel, ainsi que sur le plan des situations de travail.

Nos résultats tracent également la voie à de futures recherches intégrant les notions dynamiques « d’acteurs » et de « régions de rapports de travail », ainsi que des enjeux liés au champ politique de la vie, afin de valider la portée généralisatrice du modèle d’analyse structurationniste proposé.

Mots-clés:

- relations industrielles,

- usagers/patients,

- politiques de santé,

- organisation du travail,

- système de santé,

- nouveaux acteurs,

- régions de rapports de travail

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un modelo de análisis estructuracionista que, partiendo de una redefinición de la noción de actor en las relaciones laborales (Bellemare, 2000), propone de reconsiderar las fronteras de los sistemas de las relaciones industriales (Bellemare et Briand, 2006; Legault et Bellemare, 2008), de remplazar la noción de « sistema » por el concepto de « región », y ampliar el modelo incluyendo el estudio de las cuestiones reas a las « políticas de vida » (Giddens, 1991).

El modelo propuesto es ilustrado mediante el estudio de la influencia de los utilizadores/pacientes sobre la organización del trabajo y sobre las decisiones de las instancias de gobernanza de un hospital universitario francés y, de manera más general, sobre el sistema de salud francés (políticas públicas, prioridades y métodos de investigación, etc.).

Los resultados de este estudio muestran que los utilizadores/pacientes se han convertido en actores de las regiones de relaciones de trabajo mediante su movilización alrededor de las cuestiones vinculados a las políticas de la vida: ellos han cuestionado la frontera entre el saber experto y el saber profano y han se han apropiado así de un mayor control sobre su salud y los cuidados que le son prodigados. Las asociaciones de pacientes, así como los pacientes a nivel individual, por su lado, han modificado las regiones de relaciones de trabajo a nivel organizacional y a nivel del lugar de trabajo.

Nuestros resultados trazan igualmente la vía a futuras investigaciones que integren las nociones dinámicas de « actor » y de « regiones de relaciones de trabajo », así como las cuestiones vinculadas a las políticas de vida, con el fin de validar el alcance generalizador del modelo propuesto.

Palabras claves:

- relaciones laborales,

- utilizadores/pacientes,

- políticas de salud,

- organización del trabajo,

- sistema de salud,

- nuevos actores,

- regiones de relaciones de trabajo

Corps de l’article

Introduction: revisiting the user/patient concept

Over the last fifteen years in France, the behaviour of “users/patients“ in hospitals has changed: they are now better informed, express their expectations more freely and are represented in the hospital’s organization. In this paper, “user/patient“ refers to a recipient of health care services and is based on Gadrey’s (1996) generic term “end-user of goods and services.“

Users/patients’ groups, whose aim is to collectively defend user/patient rights, have grown in number since the 1970s. Under French regulation, users/patients now have access to their medical files. Access to information has also been facilitated by the widespread use of information technologies. Moreover, in 2002, French hospitals established the institutionalization of user/patient representatives in hospital governance, allowing for their participation on the board.

These developments are manifestations of new social movements (Giddens, 1991), i.e. the revision of the frontier between expert and lay knowledge combined with the intensification of “life politics“, which entails that actors act on all issues that are central to their identities. In France, users/patients’ associations pushed for remedies in response to the infected blood scandal and have promoted the advancement of research on rare diseases. On an individual basis, users/patients request information on their symptoms and diseases as well as on the available treatments, and argue with medical staff even though they are not experts. These changes have led users/patients to become co-producers with care services actors (Grosjean et al., 2004; van Eijk and Steen, 2014; Minvielle et al., 2014) and have transformed user/patient relations with medical institutions and staff.

The aim of this article is to develop a dynamic theoretical framework of labour relations and illustrate it by investigating the extent to which users/patients have become industrial relations actors in a French hospital. We propose an analytical framework that uses the notion of region, defined as “the structuration of social conduct across time-space” (this concept will be developed in the next section). In the case of the hospital surveyed, the analysis brought out three different regions that influence one another:

the state region, within which users/patients influence national medical priorities, including those of hospitals;

the worksite region, within which users/patients influence the work organization of the nursing and other medical staff;

the organizational regions, within which users/patients’ representation on the board influences the decision-making process, especially decisions dealing with human resource management and collective bargaining.

This article is structured as follows: we first present the analytical model; secondly, we briefly outline the methodology; thirdly, we explain user/patient actions within the national, worksite and hospital governance regions; and, finally, we discuss the results. To conclude, we present the limitations and avenues for future research.

End-users as work relations actors: an analytical model

The notion of actor in the “industrial relations (IR) system“

As proposed by Bellemare (2000), an actor is defined as an individual, group or institution that is capable, through its own actions, of (directly or indirectly) influencing industrial relations processes, including the causal powers deployed by other actors in the industrial relations environment. The notion of actor has two dimensions: “an instrumental dimension, which refers to the means by which an actor exerts a certain degree of influence on the system, and an outcomes dimension, characterized by the goals and ends being pursued“ (Bellemare, 2000: 388). In this analytical framework, “the traditional dichotomy between actors and non-actors in industrial relations is set aside in favour of the influence continuum resulting from the actions of individuals, groups, and institutions whose importance as industrial relations actors varies across time and space“ (Legault and Bellemare, 2008: 745).

Bellemare’s (2000) notion of actor has been largely used in the industrial relations literature and enhanced by other authors over the years. Drawing on Bellemare’s (2000) framework, Abbott (2006) has shown that it is not essential for an IR actor to have influence on all regions or be influential at all times to have an impact on the definition of work conditions. Kessler and Bach (2011: 593) argue that “end users should not be considered as a homogeneous actor“ and point out that not all individual end-users have the same resources and opportunities to develop effective action. Hickey (2012), for his part, showed that organizational reforms in the public sector, pursued in the context of new public management, could lead to efforts by management to co-opt and control end-users.

To analyze user/patient action, we draw on Giddens’ structuration theory and Bellemare and Briand’s (2011) adaptation of it for the industrial relations field. Thus, in line with Giddens’ hypothesis on the duality of structure, we consider that an IR system involves both the conditions for and results of the interaction of actors. From a structurationist perspective, work relations are conceived in terms of the “appropriation“ and “transformation“ of an environment by actors, rather than as the passive localization of activities in specific situations (within both the local and national regions). Furthermore, the structurationist perspective posits that the competence of an actor no longer rests on his or her expertise or role but rather on the possibilities for any actor to influence a social system: in other words, industrial relations actors cannot always be identified a priori. Finally, the contexts cannot be totally defined or circumscribed, since actors and contexts are defined through interactions.

To clearly express our break from system- and strategic-based IR theories, which define IR features in a static way (with predefined actors and roles, a separation between context and the IR system and a positivist epistemology) and have difficulty considering new IR actors (Bellemare, 2000), we replace the notion of “IR system” by that of “work relations regions” (WRRs) and propose that, in order to understand a specific work relations region, it is necessary to analyze its “regionalization“ (or the systematization of the system).

The “work relations region” and “regionalization” concepts: definition and potential explanatory power

We use the concepts of “region“ and “regionalization“ proposed by Giddens. “Region“ refers to “the structuration of social conduct across time-space“ (Giddens, 1984: 122). A region can be identified by its physical, social or cultural characteristics: it can be an office, an organization, a value chain, a sector, a country or a set of supranational practices, such as capitalism. A region can also pertain to male-female or inter-racial relations or the relationship between expert and lay knowledge (Lamont and Molnar, 2002).

Regionalization is the term used to describe and explain practices that contribute to the transformation of sets of labour relations. It is a conflictual process that considers the asymmetry of power relations and of the actors’ strategies. It refers to the “time-space differentiation of regions either within or between locales“ (Giddens, 1984: 376). While the concept of the work relations region refers to a set of labour relations that are relatively stable over a given space-time, the concept of regionalization focuses particularly on the transformation of regions. It implies that social systems rarely have easily identified boundaries. Thus, the concept of regionalization does not require that micro and macro regions be defined in order to study the transformation of a social system. Regionalization implies that the smallest unit of interaction (a meeting between two people) can never take place or be explained in isolation. Arbitrary definitions of the micro and macro regions, which distort the overall analysis, are therefore avoided (Giddens, 1984: 142).

In the model proposed by Bellemare (2000), “new and old actors are given the power to produce results in the form of new modes of regulation and new social relations parties“ (Legault and Bellemare, 2008: 747). The concepts of region and regionalization are sufficiently abstract to allow for the identification of: 1- the relevant regions of action, whether they be infranational (for instance, organizational and worksite regions), national or supranational; and 2- the influences between the various regions. These concepts also provide the means to recognize the changes taking place at the boundaries of regions, i.e. late modernity’s de-differentiation of social practices in regions that were once considered separate, such as the private and public spheres or, as will be the case here, the de-differentiation of expert and lay knowledge (Bellemare and Briand, 2011). With regard to the latter aspect, it should be pointed out that the activity of experts introduces specialized knowledge into the general culture of a system. However, according to Giddens (1976), this specialized knowledge is integrated by all the agents in a social system, even though these agents do not come from the field of expertise and, moreover, lack the ability to express this knowledge using the specialized discourse. The de-differentiation of expert and lay knowledge is echoed in Giddens’ (1976) suggestion that the mutual knowledge of a given social system is an amalgam of conventions derived from shared meaning and the specialized knowledge introduced by the activity of experts.

Work relations regions and life politics

In late modernity, Giddens (1991) identifies the appearance and intensification of issues related to life politics, i.e. the idea that personal identity is no longer simply inherited from an individual’s social situation but, rather, that each individual builds his or her own identity reflexively, by choosing among a variety of possible lifestyles, in contexts of local and global interpenetration. According to Giddens (1991; see also Offe, 1985), struggles in the field of life politics have been influenced by new social movements. Hence, the issues raised by new social movements are supplanting the quest for emancipation, which, in modernity, was led primarily by the trade union movement. This recognition of life politics issues is important to social actors in terms of recognizing issues that are not primarily related to wages and working conditions but rather to the question of identity. In this paper, emancipation and life politics issues are not considered in opposition, but rather in complementarity (Bellemare and Briand, 2011).

The development of the field of life politics, thus, requires that industrial relations researchers: 1- introduce new actors into their studies (Heery, Abbott and Williams, 2012; Kessler and Bach, 2011; Michelson et al., 2008); and 2- identify the new social movements (environmentalism, feminism, etc.) that are likely to have an impact on work (sustainable development or gender issues, for example), as well as the emancipatory projects that drive the individual actors involved in a given region.

In this paper, we posit that, in the health care sector, life politics and emancipation issues are giving way to the rising protest movements of users/patients who, individually and collectively, have decided not to leave the determination of diagnoses and treatments entirely up to medical experts. Through their mobilization, users/patients are contributing to the redefinition of: 1- the boundaries between expert knowledge and lay knowledge; 2- the roles of medical staff and users/patients; and, ultimately, 3- the definition of work. The concept of region makes it possible to recognize a wide range of areas of interactions and issues (related to emancipation and life politics) that produce, or are produced by, work relations. This concept makes it possible to recognize IR systems in traditional approaches (shop, nation, etc.) while also encompassing areas (“vertical” regions)—the worksite and organizational regions in particular—and life politics issues (“horizontal” regions) that are overlooked in Dunlopian and strategic theories (see Bellemare, 2000 and Heery et al., 2012 for a presentation and critique of these theories).

A structurationist model for the analysis of work relations regions

We conclude this section by presenting the overall model (Figure 1) and recapitulating some of the core concepts that will be used for the analysis of work relations and their transformations.

In the proposed model, the actor (individual or collective) and his action are at the intersection of two axes: 1- a vertical axis, that of the regions (supranational, national, infranational); and 2- a horizontal axis, that of the life politics (identity) and emancipation (working conditions) issues. The bi-directional links that connect the various elements of the model express the duality of structure and the reflexivity, central to the structurationist analysis. Finally, according to the theory of structuration, regions as well as life politics and emancipation issues are indeterminate a priori.

Figure 1

The Model of Work Relations Region(s) (WRRs)

In this model, the following definition apply:

Actors in a given IR system assume their role in multiple ways in an organization’s or a sector’s internal social relations as they influence the organization of work, the management of human resources, and the determination of working conditions. As well, they can act within a national region by participating in the definition of the political and legislative policies of society […] Their action can vary in intensity (occasional or continuous), scope (limited to the organization or extended to include regulatory institutions), or outcome (lead to or impose large-scale durable transformation or remain circumscribed and prompt minor changes).

Legault and Bellemare, 2008: 746

These intensity/outcome processes represent the structuration processes that contribute to the reproduction or transformation of the work relations regions.

In the model presented above, regionalization is the term used to describe and explain practices that contribute to the transformation of work relations. When work relations are relatively stable over a certain time-space, they are referred to as “work relations regions“ (WRRs). WRRs are both the medium and the outcome of action. They are routinely reproduced by actors, but can also be (intentionally or unintentionally) transformed.

In analyzing WRRs, it is necessary to identify the actors who participate in the structuration of work relations, and the rules governing them, by examining how the actors structure and are structured by the various social relations regions (work, gender, ethnic group, religion, etc.). Moreover, since regionalization is a conflictual process, and given the asymmetrical power relations and strategies of the actors, it is understood that actors may wish one type of regionalization to predominate over others.

This WRR model will be used to analyze the development of the French social movement led by users/patients and the latter’s influence on work relations in a public hospital in France. Are users/patients becoming actors in the work relations regions in the hospital sector? Why have they organized collectively to act on the health system? What kind of actions do they use? What are the effects of their actions on the work relations regions in the hospital sector?

Methodology

Adopting structuration theory requires that the researcher choose between two research schemes, namely analyzing strategic behaviours or analyzing institutions (Giddens, 1987), since structures are actualized through human activity. In accordance with Giddens, research must therefore consider the conditions and knowledge that have enabled and constrained the action that actualizes and transforms work relations. Thus, this research is based on a dual methodology used to illustrate the analytical model presented above.

To analyze the national region, we identified documents developed in France on the emergence of users/patients’ associations in the health care sector over the last 15 years. This movement is often referred to as “health care democracy“. We used the following keywords (translated into English here) to locate and investigate the literature: “social movement and hospital,” “2002 Law on Patients’ Rights,” “user representation,” “users’ association,” “patients’ associations,” “patients and hospital,” “health care democracy,” “health policy“ and “activism.“

To analyze the organizational and worksite regions, we conducted a new analysis of data collected for an exploratory case study carried out in a French hospital. Exploratory case studies offer the advantages of exploring phenomena that are multidimensional and difficult to understand (Yin, 2014). Moreover, they facilitate the understanding of research goals, allow for questions to be adjusted, and can reveal complementary or new dimensions of a social reality (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Our case study represented an opportunity to explore the dimensions of a new social reality associated with the influence of users/patients in a hospital.

The data were collected in a University Hospital in France (Havard and Naschberger, 2015) between 2005 and 2006. At the time of data collection, the hospital employed approximately 10,200 employees (1800 medical staff and 8400 non-medical staff). Thirteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with management representatives (the Director of regulations and users/patients, the Human Resources Director and two Nursing Staff Supervisors), four Union Representatives, three User/Patient Representatives, and two Nursing Professionals. All interviewees had a high level of seniority and a good knowledge of the hospital surveyed. The aim of the in-depth interviews was to collect diverse views on the changes that had been carried out in the hospital (relating to users/patients’ awareness, users/patients’ behaviour, and changes in organizational structure, working conditions and methods of collective bargaining) and perceptions of interactions between some chosen actors (users/patients and nursing staff; user/patient representatives and union representatives). We chose to focus on the working conditions of the nursing staff because the latter have regular and close contact with users/patients, and to overlook other occupational groups (physicians, for example) that have been the subject of numerous studies (Castel, 2005) and are less in direct contact with users/patients and their entourage. The interviews (lasting 90 to 120 minutes) were recorded and fully transcribed verbatim. Different actors were interviewed on the following points: the role of users/patients in the hospital; the mechanisms of their representation; the behaviours of users/patients, and their evolution; the relations between users/patients and nursing staff; and changes affecting the nursing staff as a result of contact with users/patients. Hospital documents (pluri-annual plan, social project, Charter of Patients’ Rights) were also collected and examined to supplement the data collected through the interviews. All the data were analyzed using content analysis techniques, in three phases (Creswell, 2013): 1- a pre-analysis aimed at identifying the different topics related to the structurationist model; 2- categorization of the data; and 3- interpretation by crossing the analyses of two of the researchers. The internal validity of the information presented below is limited by the small number of interviews conducted (Miles and Huberman, 1994). However, the information provided by the different interviewees (management, users/patients, nursing staff, unions) was crossed to formulate some substantial illustrations of the developments produced by the growing involvement of users/patients. The external validity of this illustrative study can be assessed in the light of other research (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Johnson, 1997), however the results produced for the organizational region cannot be generalized.

Emergence of users/patients in the health care and hospital regions

The results will be presented by region, as they emerged through the data analysis. It should be noted that there is no a priori causal hierarchy between the regions identified, in accordance with the precepts of structuration theory.

In the following subsections, we first present the “national region,“ then the “worksite region“ and lastly the “organizational region.“ The order in which the regions are presented follows the importance of the actions (intensity of actions) and transformations (outcomes) observed therein. The order of presentation also follows a temporal logic, considering that:

Patients began individually contesting patient-medical staff relations in the 1970s;

These protests empowered users/patients in their action in the worksite region;

During the 1980s and 1990s, patients organized collectively and pressured the state for changes in the national health system and hospital governance, which, in turn, also empowered users/patients in their action in the worksite region.

We will first present the “national region,” then the “worksite region“ and lastly the “organizational region.“

National Region: Establishing the user/patient as an actor

In France, the rise of demands and the mobilization of users in the field of health grew out of associations formed by patients with rare diseases. The mobilization of patients with rare diseases was itself inspired by “the American feminist movement around health issues“ (Quéré, 2016: 36). These movements illustrate the will of users/patients to have a say in medical practices in an era characterized by a lack of confidence in biomedicine (Bureau and Hermann-Mesfen, 2014: 5).

Consequently, users/patients and their associations have come to demand that public policies, prevention practices, research programs, the modes of organization of care, and work practices in hospitals be co-designed, co-produced and co-monitored (Bellemare, 2000) as defined in the research on service activities (Reboud, 2001; Gadrey, 2003; Korczinki, 2013; Gofen, 2015). “The notion of co-production posits that an end user’s action influences, either voluntarily or involuntarily, the efficiency, productivity and manner in which the service is delivered“ (Bellemare, 2000: 390). End users, individually or through an association, act as “co-supervisors of employees, directly or indirectly, either as witnesses or initiators of disciplinary measures“ (Ibid., 392).

Finally, end users can act as co-designers of the service relationship:

End users are invited as individuals, as members of focus groups, or in a more political capacity (pressure groups, end user representatives) to participate in the definition of their needs or of the product and methods of production. They are also frequently called upon to evaluate the quality of the product, its price and how it should be marketed.

Bellemare, 2000: 394

The action of users is multi-scalar and transforms the boundaries between patients and caregivers, and between expert and lay knowledge:

[A]utonomy and self-determination, individual responsibility, and the ability to influence matters of self-concern, identify and meet one’s needs, solve problems and control one’s own life, are symbolic values of contemporary individualism […] Shared knowledge and power, equality, respect, kindness, and giving importance to the subjectivity of the individual are now placed at the heart of medical practice.

Bureau and Hermann-Mesfen, 2014: 7, trans.

Starting in the 1950s, French patients’ associations began to undergo significant changes:

[M]ore rare disease-related associations were created and led by patients and their relatives. At the same time, the rise of AIDS and the crisis that ensued, favoured the emergence of a new model of organization. HIV patients, feeling very much abandoned, became active, informed and organized, thus deconstructing the image of the passive patient who is ignorant and in need of the expertise provided by the medical elite. The active mobilization of AIDS patients was followed by the creation of a significant number of patients’ associations.

Chalamon, 2009: 95, trans.

Between 1985 and 2002, the number of French patients’ associations increased from 50 to 310 (Chalamon, 2009: 95). These associations provide various forms of support to patients, namely “social, legal and financial support“ (Bureau and Hermann-Mesfen, 2014: 5, trans.).

The combined effects of research developments and social movements led to the development of a community that: “encourages vulnerable groups to participate in the development, implementation and management of health programs […] and promotes the idea that the best way to inform individuals about disease is to educate them through their peers“ (Bureau and Hermann-Mesfen, 2014: 4, trans.). In turn, these developments were followed by legislative changes in France. The Order of April 24 1996 introduced user/patient representatives on the boards of public health facilities as well as on “numerous hospital committees, where their lay knowledge and proximity to patients are considered assets […]. User representatives play a ‘lookout’ role within the institution through their repeated contacts with patients and members of their association“ (Bréchat et al., 2006: 252-253, trans.).

In 1999, a report on the general state of health in France led to the adoption of the Law of March 4, 2002, enshrining the right of patients to receive quality care:

The law introduces representation and participation rights (accreditation of associations, users’ representation in hospitals and regional health agencies, and the creation of a committee on relations with users and the quality of internal support at each institution) […]. A second part strengthens the individual rights of each patient (information, conditions of access to medical records and freedom of expression, particularly with regard to the quality of care).

Lecoeur-Boender, 2007: 637, trans.

The mobilization of patients has altered the boundaries of the health system, reducing the distance between expert and lay knowledge and between researchers and patients (Quéré, 2016; Akrich and Rabeharisoa, 2012). For instance, through its effective fundraising campaigns, the French Association against Myopathies has taken an active role in the direction of genetic research. Patients’ associations have been able to mobilize their members and influence the development of public health policies (priorities, funding, clinical trial designs). They have also been able to influence the national research orientations such that orphan drugs and diseases are now covered by the French health system. New multi-discipline hospitals, acting as reference centres, have been created (Chalamon, 2009).

The 2002 Law provides opportunities for action by local actors in hospitals, individually and collectively, to assert their interests and needs. However, these new opportunities are constrained by power inequalities between medical staff and users/patients, in the therapeutic physician-patient relationship (Bureau and Hermann-Mesfen, 2014), and the relationship between user/patient representatives and representatives of other groups (administrators, medical staff) in decision-making and local deliberation bodies, such as boards and committees (Lecoeur-Boender, 2007; Ghadi et al., 2006). Indeed, Tabuteau (2010) showed the limits of health care democracy. These new citizens’ rights in the field of health have coincided with a reform of the health system that has extended state control, through regional health agencies, “over the regulation and control of the entire health system” (p. 83, trans.). This extension of state power over the health system can limit democratization within the regional agencies and hospitals.

Nevertheless, users/patients’ power has risen nationally, through the influence of representatives of various users/patients’ associations. These representatives have succeeded in developing strong medical and organizational expertise generated by their communications networks with their members and the networks of expertise they have managed to mobilize.

Overall, the empowerment of users/patients has been somewhat paradoxical. In fact, there appears to be a global strategy on the part of the state to empower users/patients, while, at the same time, reducing public investment by transferring costs to individuals and their private insurance, a phenomenon referred to by Batifoulier et al. (2008: 32, trans) as “patient market reconfiguration.“ This strategy has led to decreased access to the health system for less fortunate or uninsured patients. It has also led to the creation of new positions in the health system, those of mediators (Compagnon et al., 2006), who sometimes support the empowerment of users/patients and occasionally deter it.

Individual challenges to the therapeutic relationship have become generalized and spread to various regions through the creation and reorientation of users/patients’ associations. Political and economic actions (fundraising campaigns that have subsequently made it possible to steer research) have been taken in the national region. In this region, users/patients’ associations have helped transform the work organization at the ministerial and research levels. They have participated in the co-design of health policies and health research and, in the case of some users/patients’ associations, in co-monitoring, by participating in various ministerial and health program committees. As brought out in our literature review, the work of health researchers has been transformed by the co-design of research protocols and the choice of research priorities. Overall, in the national work relations region, the action of users/patients has been major with respect to the co-design of health and research policies, but relatively minor when it comes to changing the work relations between researchers and users/patients.

These actions in the national region on the part of users/patients’ associations have also led to laws enabling their members’ actions in the hospital. Their actions in the worksite and governance regions had an effect on the work of care personnel and supervisors, more so in the worksite region than in the governance region, as will be seen in the following sections.

Worksite region: users/patients are changing the “rules of the game“

Over the last twenty years, the behaviour of users/patients in hospitals has changed. Users/patients are better represented, better informed and express their expectations regarding hospital services more freely. These changes in behaviour have led to a significant transformation in the work practices of nursing staff, whose work has come under pressure.

The changing behaviour of users/patients

The comments collected during our interviews show how user/patient behaviour has changed. Users/patients are better informed and more demanding with hospital staff and express their expectations more readily (see Table 1).

Table 1

Users / Patients’ Expectations and Behaviours (verbatim)

* Note: Hospital visitors refer to individuals who are members of users/patients’ associations. They visit patients in hospital voluntarily and collect comments from them, which they then pass on to user/patient representatives.

On the whole, users/patients are better informed of their rights. This change can be explained by the implementation of the Law of March 4, 2002, which allows patients to access their medical records and gives them the right to information—from diagnosis to prognosis. Their access to information has also been facilitated by the widespread distribution of information and the use of new technologies (specialist medical reviews, hospital ratings in the press, the internet, blogs, forums, etc.). Users/patients’ associations have also played a role by encouraging users/patients to demand information concerning their health status and the treatment provided. This development also reflects new types of behaviour that are evolving outside the hospital environment, in the broader society. Users/patients are better able to understand information provided by hospital staff. They grant themselves the right to contest medical diagnoses, as well as the way they are treated in the hospital process. This has led to a profound change in the relationship between nursing staff and users/patients, with users/patients becoming more active in their relationship with care providers. Since 2002, users/patients have been able to file complaints concerning their medical care. The Committee on relations with users/patients and the quality of health care is tasked with helping, guiding and informing all those who deem themselves to be victims of prejudice in the hospital.

According to the nursing staff interviewed in our study, the emergence of better informed and more demanding users/patients has had an effect on the nature and methods of their work.

The effects on the work of the nursing staff

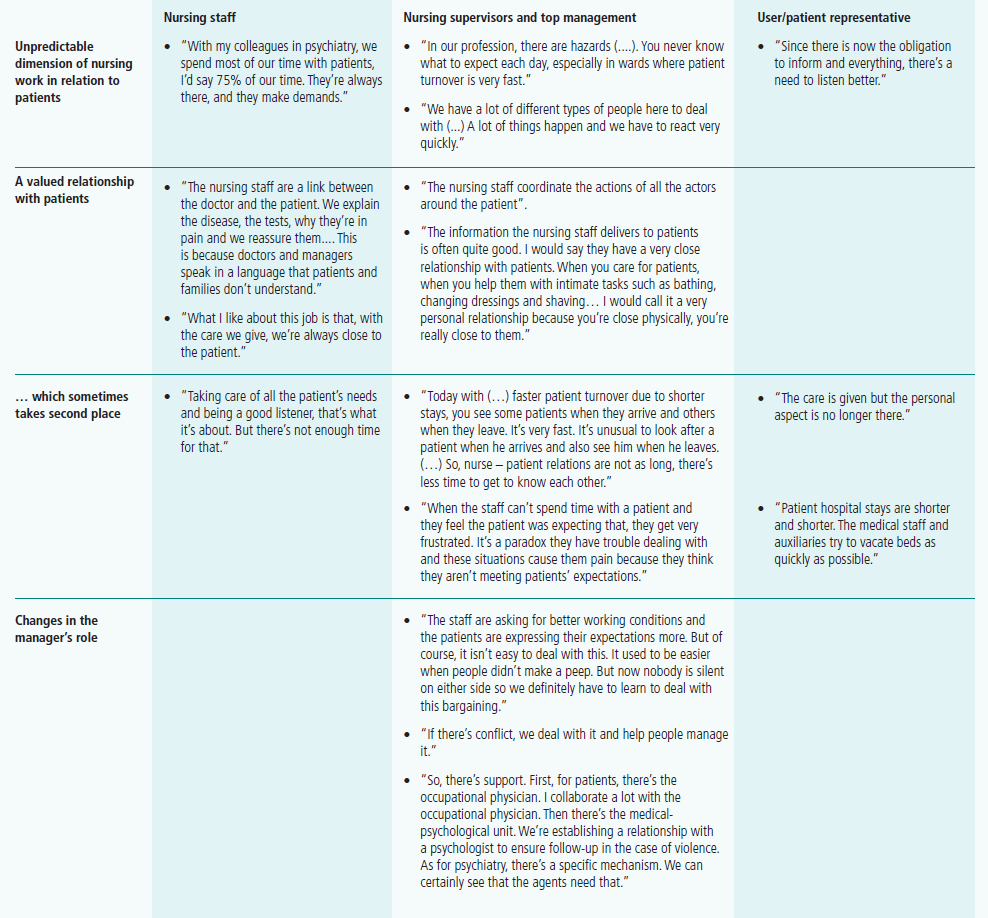

The emergence of more demanding—even consumer-like—users/patients has significantly changed the nature of the work of the nursing staff and led to new behaviours (See Table 2).

The work of the nursing staff and other personnel has become increasingly unpredictable, as they find themselves having to respond to the more salient and diverse demands of users/patients (Raveyre and Ughetto, 2003). In addition, this situation has been exacerbated by the increasing turnover of users/patients, whose length of stay has been gradually decreasing (Acker, 2005).

The hospital staff’s interactions with users/patients have, of course, always had an effect on their work (Goffman, 1961). However, these relations are currently taking on greater importance, both in the eyes of the staff, due to increasing patient demands, and also in the eyes of users/patients themselves. These relations can range from a simple discussion to a very close relationship between users/patients and the care personnel. This closer relationship has grown out of the greater need for explanations expressed by users/patients and their desire for more personalized treatment (in terms of care, but also material comfort). It also corresponds to strong expectations on the part of the nursing staff, for whom the relationship with users/patients is at the heart of the nursing profession and fits with their image of nursing (Acker, 2005; Baret and Robelet, 2010). However, based on the comments of the nursing staff and user/patient representatives interviewed, this relationship unfortunately takes second place to administrative tasks.

Table 2

The Transformation of Nursing Work (verbatim)

* Note: Hospital visitors refer to individuals who are members of users/patients’ associations. They visit patients in hospital voluntarily and collect comments from them, which they then pass on to user/patient representatives.

This phenomenon reveals one of the tensions experienced by the nursing staff. In fact, paradoxically, while patients have high expectations in terms of personal relations, it appears that the relationship aspect is not always given priority. The relationship requirement is in conflict with the nursing staff’s administrative duties, related to traceability and safety issues (updating patient notes and recording all medical acts, for example). The nursing staff’s administrative duties have also increased due to higher patient turnover. Finally, the time that can be allocated to users/patients has also been reduced because of the need to coordinate between the different hospital professions interacting with the patient (physicians, nurses and auxiliary nurses). All these changes have increased the workload of the nursing staff and reduced the time available for users/patients.

The nursing staff thus find themselves caught between users/patients’ need for a personal relationship, something they endorse, and the reduced time they have to spend with them. For the nursing staff, this conundrum challenges their image of their work and the meaning it holds for them. Previously, their relationship with users/patients gave meaning to their work (Baret and Robelet, 2010). However, having less time to spend with users/patients has altered their professional identity (Micheau and Molière, 2014). The quality of their work is perceived as being more dependent on interactions with users/patients and other care professionals (Douguet et al., 2005; Benallah and Domin, 2017) and the way they can manage the paradoxical requirements (Grévin, 2011). The nursing staff have to make arbitrary judgements and prioritize their actions. These judgements are made individually, within the nursing teams (Ruiller, 2012) or with the help of supervisors.

Faced with these developments in the workload of the nursing staff, one nursing staff supervisor that we interviewed felt that she should play more of a supporting role for them. She sought to adopt a listening posture and provide advice and training to help the nursing staff manage the difficult situations facing users/patients (Husser, 2011; Dumas and Ruiller, 2013). The other nursing staff supervisor also wished to play the role of arbitrator between the expectations of users/patients and those of different categories of employees and said that she could also intervene directly to sort out conflicts with union representatives. Moreover, to address the violence of some user/patient behaviours, the nursing management has developed some specific mechanisms aimed at supporting the nursing staff (a medical-psychological unit, a partnership with occupational medicine). In the absence of help from supervisors, the pressure perceived by the nursing staff can be a source of frustration (and even pain). They feel that they are not able to provide the quality care expected by users/patients and which they themselves wish to provide (Baret and Robelet, 2010).

To conclude, the work of the nursing staff and their supervisors thus appears to have been significantly affected by the increasing demands of users/patients with regard to co-designing the kind of care provided or co-producing care, or their contesting of the decisions made (co-monitoring). The actions of users/patients can thus have a significant influence on the nature of nursing work.

Organizational region: users/patients are present but are having difficulty changing the “rules of the game“

The hospital surveyed has adopted a Charter of Patients’ Rights and introduced user/patient representatives on the board of directors. The hospital has also facilitated the participation of user/patient representatives on steering committees. These changes in governance have given user/patient representatives the opportunity to influence decision making in the hospital. However, the data collected show that user/patient representatives have encountered some difficulties in asserting their legitimacy, especially with union representatives.

The collective representation of users/patients and their participation in the hospital’s governing body

Since 1996, two user/patient representatives have sat on the board along with management, medical and nursing staff. The board defines the general hospital policy and decides on the main actions to be implemented (hospital development plan, social projects, medical projects, investment programs, budget, etc.). Being on the board gives user/patient representatives opportunities to voice their opinions on the management of the hospital. Top management has invited user/patient representatives to participate in consultative committees and working groups in the hospital. Thus, user/patient representatives sit on the tender committee, the committee in charge of improving the quality of patient care, and a working group on the hospital’s strategic plan.

In 2002, management encouraged the different users/patients’ associations in the hospital (representing different diseases) to come together under a single entity called the “Space for Users.” This body encompasses individual users/patients’ and disease-related associations and aims to hear users/patients’ complaints, transmit users/patients’ opinions to the executive and defend users/patients’ interests. This federation of users/patients’ associations gives greater legitimacy to user/patient representatives and facilitates relations between these representatives and the top management of the hospital. It collects feedback from the different patients’ associations, lodges users/patients’ complaints with the director of users/patients and coordinates visits to users/patients by volunteer “hospital visitors,” who listen to users/patients’ complaints and pass them along to user/patient representatives.

Being informed of users/patients’ expectations and complaints, user/patient representatives can exert some influence on the decisions of the various decision-making bodies (see Table 3 for illustrations). First, during executive board meetings, user/patient representatives can voice their opinion and vote. However, according to the user/patient representatives interviewed, these opinions are sometimes formulated, through consultations with the director of regulations and users/patients, before the meetings take place. Second, their participation in various committees and working groups gives user/patient representatives the opportunity to defend users/patients’ interests. User/patient representatives can express users/patients’ views concerning the quality of care. They can also, for example, contribute to the creation of communication tools for users/patients. Moreover, user/patient representatives can participate in joint committees tasked with promoting or evaluating employees and give their opinion. They can be asked to participate in disciplinary committees to share their point of view on the reintegration or dismissal of employees found to be at fault. According to the user/patient representatives interviewed, their opinion has been listened to, even though the ultimate decision, in the case concerned, was made by management. This shows a certain openness with regard to the evaluation of the nursing staff, although this situation came up only once, according to the user/patient representatives. These two examples show that user/patient representatives can influence decisions regarding human resource management issues. In sum, through their participation in the hospital’s various decision-making bodies, user/patient representatives have the “opportunity“ to influence some decisions, as mentioned above.

The dialogue between union representatives and user/patient representatives is still difficult and the “door” of social dialogue remains closed to the latter

The participation of user/patient representatives in hospital governance is perceived as an important milestone by various stakeholders. However, while their participation in the hospital governing body is seen by management representatives as being legitimate, it has met with some reluctance on the part of union representatives. Table 4 illustrates these findings.

Table 3

User / Patient Representation in Governance and Associations (verbatim)

Table 4

Dialogue Between Top Management, Employee Representatives and User / Patient Representatives (verbatim)

Indeed, the legitimacy of user/patient representatives is questioned by union representatives. First, union representatives make a distinction between users/patients who participate in the hospital’s decision-making bodies and users/patients who are hospitalized. Second, some union representatives consider the participation of users/patients to be an “invasion” in issues relating to hospital management and employees, thus revealing users/patients’ empowerment in this work relations region. In the union representatives’ view, user/patient representatives constitute a threat to the balance of power between the management and employees because they are influenced and guided by management in making decisions. This suspicion is also demonstrated by the fact that union representatives have not expressed a need to meet user/patient representatives and vice versa. Union representatives once invited user/patient representatives to join a coalition to defend the quality of care in a retirement home and guarantee certain working conditions for employees, but the user/patient representatives declined the invitation. Therefore, union representatives do not see the need for user/patient representatives when it comes to defending the quality of hospital care through their collective demands and action. Just as they do not consider themselves as representing users/patients, they feel that user/patient representatives are only interested in defending the interests of users/patients and prefer to stay neutral regarding questions related to hospital employees. Thus, the two types of representatives limit their actions to their own interests and do not engage in any real dialogue.

Discussion: The significant but mitigated influence of users/patients in the work relations regions

The results of the empirical study will first be discussed with regard to the extent to which users/patients have influence in the WRRs and then with regard to the nature of this influence.

Users/patients have become actors in work relations regions through their mobilization regarding life politics issues. This mobilization has been effective within the national region (adoption of new public policies empowering users/patients in the organizational and worksite regions, individually and collectively, impact on research program orientations) and in the organizational and worksite regions. The move to the national region found its legitimacy in the prior resistance of the medical apparatus to the demands of users/patients, who were trapped in an individual relationship with their physicians and with nursing staff. Longstanding individual dissatisfaction in the local region legitimated the emergence of users/patients’ associations, which carry out actions in the organizational and national regions. These actions have been empowered by the global level epistemic (Cross, 2013) and activist communities of different kinds of users/patients (Quéré, 2016), which have facilitated the transfer of knowledge and a certain type of activism from the American to the European continent. These actions in the various regions have nurtured one another, in accordance with Giddens’ core concept of the duality of structure.

Within the national region, the activities of user/patient organizations have led to the emergence of a new form of representation of users/patients and their relationship with disease and the health system. Gradually, as this new representation has spread, the number of user/patient organizations has increased in France. Their mobilization has played an important role in the development of public health policies and research priorities and was influential in the adoption of the Law of March 4, 2002. In turn, this law has empowered user/patient representatives in hospital settings. We first observed the strengthening of the regulation, giving more rights to users/patients, who have become better informed and more demanding. This has helped transform the national and organizational work relations regions by opening them up to issues other than those of modernity (working conditions, pay, etc.), including life politics issues, particularly those relating to the desire of users/patients to be actors in their own health and care.

Within the infranational regions, our results are more contrasted. According to the dimensions analyzed, the impact of users/patients on hospital practices has been mixed. Within the worksite region, the relationship between users/patients and the nursing staff has been affected by users/patients’ behaviours and demands. Users/patients have become more active, participating to a greater extent in the delivery of care, and are less likely to “submit“ to the care provided to them than they were in the past (Minvielle et al., 2014). These developments have significantly affected the work of the nursing staff (Acker, 2005; Roques and Roger, 2004) and their representation of their work (Micheau and Molière, 2014). Indeed, our data bring out the growing uncertainty and unpredictability in their work, with tensions arising due to users/patients’ expectations and the complexity of administrative and coordination tasks combined with patient turnover (Grosjean, 2001; Baret and Robelet, 2010). The managerial work has also changed, aiming to reduce some tensions created by changes in user/patient behaviours (Husser, 2011; Dumas and Ruiller, 2013).

Within the organizational region, the influence of users/patients is increasing with their representation on the governing bodies of the hospital. At the board level, user/patient representatives can express users/patients’ rights and needs and contribute to the redefinition of health care services. Through their involvement in joint committees (evaluation, disciplinary committees, etc.), these representatives can influence managerial decisions, including those pertaining to the career of some employees. However, this opportunity for user/patient representatives has not been widely taken up. Indeed, according to a professional report produced for the Health Care Ministry (Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé, France), the influence of users/patients in the decision-making process of the hospital is limited (Couty and Scotton, 2013; Burstin et al., 2013). Moreover, the dialogue between users/patients and union representatives remains difficult. Union representatives have collectively refused to transcend the boundary that exists between themselves and user/patient representatives.

This case study shows that users/patients can be considered as actors in the work relations regions in the health care system and in hospitals. They are actors as individuals, as a group and as an institution (Bellemare, 2000). Their actions have led to changes in the national and infranational (organizational and worksite) regions. They have had an impact on work relations in different regions and have reduced the distinction between expert and lay knowledge.

This study brings out the interactions between the different regions: between the national and organizational regions through users/patients’ associations, representing users/patients, and through the implementation of the Law of March 4, 2002; and between the worksite and organizational regions through the role of supervisors, who strive to manage the tensions created by the more demanding behaviours of users/patients vis-à-vis administrative requirements.

All of these changes require engagement and continuous actions on the part of users/patients in all regions. While the results of user/patient activism have been slow to take root—and have been uneven from one region to another—, they have, nonetheless, become conditions for the action of other actors.

Up until the 1970s, the work relations regions involved managerial (at the state and hospital levels) and union actors, tasked with determining working conditions and the organization of work. Users/patients had no role to play. In the worksite region, their involvement in labour relations and the work of the nursing staff was limited. Patients were still generally passive and obedient, believing in the professional expertise of the hospital staff. These work relations regions changed most particularly during the 1980s and 1990s.

The main factors leading users/patients to contest the cultural boundary between expert knowledge and lay knowledge, and the social boundary between care personnel and users/patients were identified in a previous section. We also pointed out the desire of users/patients to co-design, co-produce and co-monitor the work of care personnel through their actions in various regions. Finally, we showed that action in one region can fuel action in another region, which can then fuel it in return. For example, individual protests led to the forming of several disease-related associations defending users/patients, and then the meetings and concerted actions of these associations in the national region led to changes in public health and research policies, which, in turn, empowered the action of these associations and individuals in the worksite and hospital governance regions. These local associations and user/patient representatives have participated in decisions concerning the organization of hospital services and, thus, the work organization of hospitals. They have developed various means of informing users/patients concerning their rights, the diseases affecting them and possible treatments, and the complaint procedures and progress of complaints, thus helping to strengthen their competence as actors. Finally, on an individual basis, users/patients now express their expectations to care personnel to a greater extent, discuss their situation, and demand much more than users/patients did in the 1970s. These user/patient actions in various regions, and especially in the worksite region, have had profound effects on the nature of the work of care personnel, who have also been exposed to a decrease in the resources (human and in terms of time) available to them to carry out their work. These tensions experienced in the worksite region reflect current underlying societal trends: social movements are aspiring to a greater democratization in all spheres of life, including, as in the case studied here, in the field of health, whereas the state’s austerity measures and new public management have contributed to a tighter control of the resources devoted to health care services. These two underlying trends can be instrumentalized by the actors involved in each of them, in various regions.

Conclusion, limitations and research avenues

The aim of this article was to propose an analytical model of “work relations regions” (WRR), emphasizing the different types of influence an actor can have on work relations in various regions, as well as the implications of this influence. This model was illustrated through a French hospital and the literature dealing with developments in the French health system. We also brought out the emergence of social movements relating to users/patients’ needs and expectations (life politics), which are driving the actions of users/patients, and their representatives, in all regions expressing “regionalization,” i.e. the structuration of social conduct across time and space. We then explored the extent to which users/patients constitute an actor in the WRR in a hospital.

This research presents some methodological limitations related to the exploratory nature of the empirical study used. The goal of using this empirical study was more to illustrate the analytical model than to highlight a widespread movement. We, thus, acknowledge some limitations related to our methodological choice:

The collected data are not recent and the interviews were not originally conducted for the purposes of this research;

The small number of interviews conducted and the fact that user/patient representatives, rather than users/patients themselves, were met reduce the validity of the empirical study;

While user/patient representatives can certainly express users/patients’ opinions, users/patients are heterogeneous and their claims vary from one disease to another (Chalamon et al., 2013; Hickey, 2012);

Moreover, the researchers did not directly observe the interactions between the chosen actors (users/patients and nursing staff; user/patient representatives and union representatives).

A more detailed analysis of the interactions between the chosen actors (users/patients and nursing staff; user/patient representatives and union representatives) could draw on some aspects of Husser’s (2010) operationalization, combining elements of structuration theory and interactionism, in order to study the transformation of the modalities of organizational control and to describe in more detail the modalities of establishing new control routines.

Among the several research avenues possible, we would point out the relevance of conducting new multiple case studies to provide empirical evidence of the influence that users/patients can have on work relations in the worksite and organizational regions. Other research could build on the work of Debril et al. (2014) and Cross (2013) on “epistemic communities“ to provide insight into the regionalization process within the supranational region. Pursuing this avenue of research would help provide insight into the tensions between regions (supranational, national, and infranational). Finally, it would also be worthwhile to further investigate the implementation of new public management in French hospitals using the WRR model. Changes in hospitals have often been explained using the frameworks proposed by Simonet (2013) or Minvielle et al. (2014). Since WRRs can help identify and explain both contradictions and harmonies between public policies and public management practices, we propose enriching these frameworks.

Parties annexes

Bibliography

- Abbott, Brian (2006) “Determining the Significance of the Citizens’ Advice Bureau as an Industrial Relations Actor“, Employee Relations, 28 (5), 435-448.

- Acker, Françoise (2005) “Les reconfigurations du travail infirmier à l’hôpital,“ Revue française des Affaires sociales, 59, 161-181.

- Akrich, Madeleine and Vololona Rabeharisoa (2012) “L’expertise profane dans les associations de patients. Un outil de démocratie sanitaire,” Santé publique, 24 (1), 69-74.

- Baret, Christophe and Magali Robelet (2010) “Quelles nouvelles pratiques pour réduire les tensions de la relation patient-soignant à l’hôpital?,“ in D. Retour, M. Dubois and M. E. Bobillier Chaumon (éd.), Nouveaux services, nouveaux usages, Bruxelles : De Boeck.

- Batifoulier, Philippe, Jean-Paul Domin and Maryse Gadreau (2008) “Mutation du patient et construction d’un marché de la santé. L’expertise française,“ Revue française de socio-économie, 1 (1), 27-46.

- Bellemare, Guy (1999) “Marketing et gestion des ressources humaines postmodernes. Du salarié-machine au salarié-produit?,“ Sociologie du travail, 41 (1), 89-103.

- Bellemare, Guy (2000) “End Users: Actors in the Industrial Relations System?,“ British Journal of Industrial Relations, 38, (3), 383-405.

- Bellemare, Guy and Louise Briand (2011) “Penser les relations industrielles : de la notion de système à la notion de région,“ in G. Bellemare et J.L. Klein, Innovations sociales et territoire: convergences théoriques et pratiques, Québec : PUQ/Collections Innovations sociales, p. 43-76.

- Bellemare, Guy and Louise Briand (2006) Transformations du travail/transformations des frontières des “ systèmes “ de relations industrielles, Montréal, CRISES, document de recherche RT-0606, 47 pages.

- Benallah Samia and Jean-Paul Domin (2017) “Réforme de l’hôpital. Quels enjeux en termes de travail et de santé des personnes,“ Revue de l’IRES, 91/92 (1-2), 155-183.

- Bréchat, Pierre-Henri, Alain Bérard, Christian Magnin-Feysot, Christophe Segouin and Dominique Bertrand (2006) “Usagers et politiques de santé : bilan et perspectives,“ Santé publique, 18 (2), 245-262.

- Brewis, Joanna (2004) “Refusing to be Me,“ Identity Politics at Work, New York, Routledge, 23-39.

- Burstin, Anne, Hubert Garrigue-Guyonnaud, Claire Scotton and Pierre-Louis Bras (2013) L’Hôpital - Rapport de l’Inspection Générale des Affaires sociales 2012, Paris : La Documentation française.

- Bureau, Eve and Judith Hermann-Mesfen (2014) “Les patients contemporains face à la démocratie sanitaire,“ Anthropologie et santé, 8, 1-18.

- Castel, Patrick (2005) “Le médecin, son patient et ses pairs – une nouvelle approche de la relation thérapeutique,“ Revue française de Sociologie, 46 (3), 443-467.

- Chalamon, Isabelle (2009) “Formation de la contestation et action collective,“ Revue française de Gestion, 193, 89-106.

- Chalamon, Isabelle, Inès Chouk and Benoit Heilbrunn (2013) “Does the Patient Really Act like a Supermarket Shopper? Proposal of a Typology of Patients’ Expectations towards the Healthcare System,“ International Journal of Healthcare Management, 6 (3), 142-151.

- Compagnon, Claire, Anne Festa and Philippe Amiel (2005) “Information médicale des malades et des proches par des non-soignants à l’Institut Gustave-Roussy: expérimentation, évaluation et logiques de formation,“ Revue française des Affaires sociales, 1, 261-270.

- Creswell, John W. (2013) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design – Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd edition, Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publishing

- Cross, Mai’a (2013) “Rethinking Epistemic Communities Twenty Years Later,“ Review of International Studies, 39, 137-160.

- Debril, Thomas and Giovanni Prete (2014) “Devenir ‘acteur de santé’ : des limites organisationnelles de la montée en puissance des associations de malades,“ Revue Sociologie Santé, 37, 215-233.

- Douguet, Florence, Jorge Munoz and Danièle Leboul (2005) “Les effets de l’accréditation et des mesures d’amélioration de la qualité des soins sur l’activité des personnels soignants,“ Document de travail de la DREES, no 48, juin.

- Dumas, Marc and Caroline Ruiller (2013) “Être cadre de santé de proximité à l’hôpital, quels rôles à tenir?,“ Revue de gestion des ressources humaines, 87, 42-58.

- (van) Eijk, Carola J. A. and Trui P. S. Steen (2014) “Why People Co-Produce: Analysing Citizens’ Perceptions on Co-Planning Engagement in Health Care ,“ Public Management Review, 16 (3), 358-382.

- Gadrey, Jean (2003) Socio-économie des services, Paris: Éditions La Découverte.

- Ghadi, Véronique and Michel Naiditch (2006) “Comment construire la légitimité de la participation des usagers à des problématiques de santé ?,“ Santé publique, 18, 171-186.

- Giddens, Anthony (1984) The Constitution of Society, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Giddens, Anthony (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity, Standford: Standford University Press.

- Giddens, Anthony (1976) New Rules of Sociological Method, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Gofen, Anat (2015) “Citizens’ Entrepreneurial Role in Public Service Provision,“ Public Management Review, 17 (3), 404-424.

- Goffman, Erwin (1961) Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, New York: Anchor Books.

- Grévin, Annouk (2011) Les transformations du management des établissements de santé et leur impact sur la santé au travail : l’enjeu de la reconnaissance des dynamiques de don. Étude d’un Centre de soins de suite et d’une Clinique privée malades de ”gestionnite,“ Thèse de doctorat en Sciences de Gestion, Université de Nantes.

- Grosjean, Michèle (2001) “La régulation interactionnelle des émotions dans le travail hospitalier,“ Revue internationale de psychosociologie, 7 (16), 339-355.

- Grosjean, Michèle, Johann Henry, André Barcet and Joël Bonamy (2004) “La négociation constitutive et instituante. Les co-configurations du service en réseau de soins,“ Négociations, 2 (2), 75-90.

- Havard, Christelle and Christine Naschberger (2015) “L’influence du patient sur le travail des soignants et le dialogue social à l’hôpital,“ @GRH, 4 (17), 9-41.

- Heery, Edmund, Brian Abbott and Stephen Williams (2012) “The Involvement of Civil Society Organizations in British Industrial Relations: Extent, Origins and Significance,“ British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50 (1), 47-72.

- Hickey, Robert (2012) “End-Users, Public Services, and Industrial Relations: The Restructuring of Social Services in Ontario,“ Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 67 (4), 590-611.

- Husser, Jocelyn (2010) “La théorie de la structuration : quel éclairage pour le contrôle des organisations?,“ Vie et sciences de l’entreprise,183-184 (1), 33-55.

- Husser, Jocelyn (2011) “Le pilotage des équipes hospitalières par le management quotidien d’articulation,“ Vie et sciences de l’entreprise, 189 (3), 23-45.

- Johnson, Burke R. (1997) “Examining the Validity Structure of Qualitative Research,“ Education, 118 (3), 282-292.

- Kessler, Ian and Stephen Bach (2011) “The Citizen-Consumer as Industrial Relations Actor: New Ways of Working and the End-User in Social Care,“ British Journal of Industrial Relations, 49 (1), 80-102.

- Korczinki, Marek (2013) “The Customer in the Sociology of Work: Different Ways of Going beyond the Management-Worker Dyad,“ Work, Employment and Society, 27 (6), 1-7.

- Lamont, Michèle and Virag Molnar (2002) “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences,“ Annual Review of Sociology, 28 (August), 167-195.

- Lecoeur-Boender, Marie (2007) “L’impact du droit relatif à la démocratie sanitaire sur le fonctionnement hospitalier,“ Revue Droit et société, 67 (3), 631-647.

- Legault, Marie-Josée and Guy Bellemare (2008) “Theoretical Issues with New Actors and Emergent Modes of Labour Regulation,“ Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 63 (4), 742-768.

- Micheau, Julie and Éric Molière (2014) Étude qualitative sur le thème de l’emploi du temps des infirmières et infirmiers du secteur hospitalier, Document de travail de la Direction de la recherche, des études et de l’évaluation et des statistiques, 132, 34 pages.

- Michelson, Grant, Suzanne Jamieson and John Burgess (2008) New Employment Actors. Developments from Australia, Berne: Peter Lang.

- Miles, Matthew B. and Michael A. Huberman (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis, An Expanded Sourcebook, second edition, Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publishing, translated in French Lhady Rispal Martine (2003) Analyse des données qualitatives, Louvain-La-Neuve: De Boeck.

- Minvielle, Etienne, Mathias Waelli, Claude Sicotte and John R. Kimberly (2014) “Managing Customization in Health Care: A Framework Derived from the Services Sector Literature,“ Health Policy, 117 (2), 216-227.

- Offe, Clauss (1985) “New Social Movements: Challenging the Boundaries of Institutional Politics,“ SocialResearch, 52, 817-868.

- Quéré, Lucille (2016) “Luttes féministes autour du consentement. Héritages et impensés des mobilisations contemporaines sur la gynécologie,“ Nouvelles questions féministes, 35 (1), 32-47.

- Raveyre, Marie and Pascal Ughetto (2003) “Le travail, part oubliée des restructurations hospitalières,“ Revue française des Affaires sociales, 52, 97-119.

- Ruiller, Caroline (2012) “Le caractère socio-émotionnel des relations de soutien social à l’hôpital,“ Management et Avenir, 52, 15-34.

- Roques, Olivier and Alain Roger (2004) “Pression au travail et sentiment de compétence dans l’hôpital public,“ Politiques et management public, 22 (4), 47-63.

- Simonet, Daniel (2013) “New Public Management and the Reform of French Public Hospitals,“ Journal of Public Affairs, 13 (3), 260-271.

- Strauss, Anselm and Juliet Corbin (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, (2nd ed.), Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publishing.

- Tabuteau, Didier (2010) “Loi Hôpital, patients, santé et territoires (HPST) : des interrogations pour demain!,“ Santé publique, 22 (1), 78-90.

- Swyngedouw, Erik (1997) “Neither Global nor Local. ‘Glocalization’ and the Politics of Scale,“ in K.R. Cox (Ed.), Spaces of Globalization. Reasserting the Power of the Local, New York: Guilford Press, 137-166.

- Yin, Robert K. (2014) Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publishing.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

The Model of Work Relations Region(s) (WRRs)

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Users / Patients’ Expectations and Behaviours (verbatim)

Table 2

The Transformation of Nursing Work (verbatim)

Table 3

User / Patient Representation in Governance and Associations (verbatim)

Table 4

Dialogue Between Top Management, Employee Representatives and User / Patient Representatives (verbatim)

10.7202/019545ar

10.7202/019545ar