Résumés

Abstract

Health sector reform of the 1990s affected most health care workers in Ontario and in other provinces. As a result of organizational changes, many workers experienced work intensification. This paper examines the associations between work intensification, stress and job satisfaction focusing on nurses in three teaching hospitals in Ontario. Data come from our 2002 survey of 949 nurses who worked in their employing hospital since the early 1990s when the health sector reform era began. Results show that nurses feel their work has intensified since the health sector reform of the 1990s, and work intensification contributed to increased stress and decreased job satisfaction. Results provide empirical support to the literature which suggests that work intensification has an adverse effect on workers’ health and well-being, and work attitudes.

Résumé

Les changements organisationnels apportés dans les années 80 et 90 ont contribué à l’intensification du travail dans les pays industrialisés (Green, 2004; Lapido et Wilkinson, 2002). Des recherches effectuées dans des pays européens et sept pays membres de l’OCDE démontrent que la satisfaction au travail est stable ou en déclin (Clark, 2005) et que l’intensification du travail est l’un des facteurs contribuant au déclin de la satisfaction au travail (Green et Tsitsianis, 2005). Au Canada, aucune étude ne s’est intéressée au lien entre la satisfaction au travail et l’intensification du travail. Toutefois, deux récents sondages indiquent qu’un travailleur canadien sur dix n’est pas satisfait au travail (Catlin, 2001; WES Compendium, 2001).

Les changements organisationnels constituent communément une source d’intensification du travail (Green, 2004). Les organisations du secteur de la santé ont subit de nombreux changements organisationnels depuis le début des années 90 (CHSRF, 2000). Le personnel infirmier a été très affecté par les réformes du secteur de la santé. Plusieurs infirmières et infirmiers ont été mis à pied et le personnel restant a dû mettre les bouchées doubles pour prendre en charge le surplus de travail occasionné par ces départs involontaires (O’Brien-Pallas et al., 2004). Les réformes du secteur de la santé reposant sur de petits budgets peuvent avoir de lourdes conséquences pour le personnel : leur travail peut s’intensifier, devenir plus exigeant et stressant (Wetzel, 2005a), amenant une baisse de la satisfaction au travail.

L’objectif de cette étude est d’examiner le lien entre l’intensification du travail, le stress et la satisfaction au travail. Notre étude contribue à l’avancement des connaissances en gestion des ressources humaines en examinant l’une des conséquences de la réforme du secteur de la santé, c’est-à-dire l’intensification du travail, sur la santé et le bien-être du personnel infirmier et sur son attitude envers son emploi. Dans un contexte de pénurie de main-d’oeuvre dans le secteur de la santé et d’un besoin grandissant de services infirmiers, notre étude porte précisément sur la satisfaction au travail des infirmières et infirmiers et est ainsi importante et d’actualité. Les données de cette étude ont été recueillies auprès de 949 infirmières et infirmiers déjà en emploi avant l’implantation de la réforme du secteur de la santé travaillant dans trois hôpitaux universitaires de l’Ontario. Toutes les infirmières et infirmiers de ces établissements ont été sélectionnés pour l’étude. Au total, 1 396 d’entre eux ont participé à l’étude, représentant un taux de réponse de 52 %. Le New Health Care Worker Questionnaire (des auteurs) est l’outil ayant servi à amasser les données. La variable dépendante, la satisfaction au travail, a été mesurée à partir du Spector’s 1985 Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) (1997). Les deux sous-échelles sont la satisfaction liée aux avantages pécuniaires et la satisfaction liée à l’emploi et à l’environnement de travail. L’intensification du travail est la variable indépendante de notre étude. Il n’y pas d’outil mesurant l’intensification du travail faisant consensus (Burchell, 2002; Green, 2004). Nous avons utilisé dans cette étude un outil mesurant la perception d’une intensification du travail que nous avons nous-mêmes développé. Cet outil stipule l’énoncé suivant : « Il y a eu plusieurs changements dans le système de santé depuis le début des années 90. En comparant le temps présent et le début des années 90, veuillez indiquer votre accord ou désaccord avec chacun des énoncés ». Les énoncés sont : « mon travail s’est intensifié; ma charge de travail a augmenté; les infirmières et infirmiers doivent traiter plus de patients par quart de travail; je fais de plus en plus de travail pour lequel je ne reçois pas de rémunération; il y a moins de leaders parmi le personnel infirmier; et la complexité des cas à traiter a augmenté ». Les réponses ont été recueillies à partir d’une échelle de type Likert à cinq niveaux allant de 1 : « je suis tout à fait en désaccord », à 5 : « je suis tout à fait en accord » et les résultats ont été additionnés pour créer l’échelle mesurant l’intensification du travail. Nous avons effectué une analyse factorielle utilisant la méthode d’extraction de l’analyse de la composante principale (Principal Component Analysis). Une composante principale fut extraite. L’échelle de mesure de l’intensification du travail démontre une forte fiabilité de l’outil grâce à un alpha de Cronbach de 0,80 (voir le tableau 1 de l’article). Pour ce qui est de la cohérence externe de l’outil de mesure, notre échantillon est comparable à celui d’autres études qui ont trouvé une intensification plus grande du travail dans le secteur de la santé et des services sociaux (Boisard et al., 2003b), pour les femmes (Burchell et Fagan, 2002) et pour les travailleurs du secteur public (Green, 2004). Le Symptoms of Stress Scale (Denton et al., 2002b) est la variable modératrice dans cette étude.

Les résultats démontrent que le personnel infirmier est dans une certaine mesure satisfait des avantages pécuniaires (M = 33,7; S.D. = 6,5) et modérément satisfait de son emploi et de son environnement de travail (M = 76,6; S.D. = 11,1). Il existe une perception généralisée que le travail s’est intensifié durant la dernière décennie (M = 24,2; S.D. = 3,9) et le personnel infirmier se sent stressé (M = 32,5; S.D. = 7,9). En contrôlant la satisfaction à l’égard des avantages pécuniaires, l’intensification du travail et le stress sont significativement et négativement corrélés (–0,343; p ≥ .01 et –0,502; p ≥ .01, respectivement). Le modèle global (voir le tableau 3, colonne 4 de l’article) démontre que le stress est significativement et négativement associé à la satisfaction liée aux avantages pécuniaires et que le stress a un effet modérateur partiel sur l’intensification du travail. Le modèle de la satisfaction liée aux avantages pécuniaires est sain, expliquant 29 % de la variance. Tel que présenté, dans le modèle global (tableau 4, colonne 4 de l’article), le stress a un effet modérateur sur l’intensification du travail en relation avec la satisfaction liée à l’emploi et à l’environnement de travail. Il est intéressant de noter que notre modèle de la satisfaction liée à l’emploi et à l’environnement de travail explique à lui seul près de 68 % de la variance totale.

Notre étude confirme les prédictions de Wetzel (2005a) quant au personnel infirmier et démontre que la perception de l’intensification du travail est un facteur significatif contribuant à augmenter le niveau de stress chez les infirmières et infirmiers. Ce stress, en retour, affecte négativement leur satisfaction au travail. Considérant que l’attraction et la rétention du personnel travaillant dans le secteur de la santé est le défi le plus important posé aux gestionnaires du système de santé canadien, nos résultats sont importants. Ils expliquent pourquoi le personnel infirmier se sent stressé et comment ce stress contribue à diminuer leur satisfaction au travail. Nous recommandons fortement aux décideurs de tous les niveaux, et en particulier à ceux qui élaborent les politiques, de porter une attention particulière aux effets à long terme occasionnés par les décisions stratégiques qu’ils prennent concernant leurs personnels.

Resumen

La reforma del sector de salud de los años 1990 afectó la mayoría de los trabajadores de la salud en Ontario y otras provincias. Como resultado de los cambios organizacionales, muchos trabajadores experimentaron intensificación del trabajo. Este documento examina las asociaciones entre intensificación del trabajo, estrés y satisfacción del trabajo focalizando la situación de las enfermeras en tres hospitales de enseñanza en Ontario. Los datos provienen de nuestra encuesta administrada en 2002 a 949 enfermeras que trabajaban en esos hospitales desde los comienzos de los años 90 cuando la reforma del sector salud comenzaba. Los resultados muestran que las enfermeras sienten que su trabajo se ha intensificado con la reforma del sector de los años 1990 y que la intensificación del trabajo contribuye a incrementar el estrés y disminuir la satisfacción del trabajo. Los resultados proveen soporte empírico a la literatura que sugiere que la intensificación del trabajo tiene un efecto adverso en la salud y el bienestar de los trabajadores y en las actitudes en el trabajo.

Corps de l’article

There are concerns that organizational changes in the 1980s and 1990s have intensified work in industrialized countries (Green, 2004; Ladipo and Wilkinson, 2002). Research from European countries and from seven OECD countries shows that job satisfaction is either stable or declining (Clark, 2005) and that work intensification is one of the factors associated with declining job satisfaction (Green and Tsitsianis, 2005). In Canada, there are no studies on the trend of job satisfaction and its association with work intensification. However, two recent surveys show that one in ten workers in Canada is not satisfied with his/her job (Catlin, 2001; WES Compendium, 2001). Organizational changes are a common source of work intensification (Green, 2004). Health sector organizations went through major organizational changes since the early 1990s (CHSRF, 2000). The nursing labour force was heavily affected by the health sector reforms. Many nurses were laid off, and remaining nurses had to take on greater workloads (O’Brien-Pallas et al., 2004). Health sector reforms implemented on short budgets can have long-term effects on staff: their work can become intensified, increasingly demanding and stressful (Wetzel, 2005a), leading to decreased job satisfaction.

At a time when there are shortages of nurses and projections for increased demand for nursing labour, our study focusing on nurses’ job satisfaction is important and timely. The Romanow Commission (2002a, 2002b) on the future of Canada’s health care system and public consultations on health sector reform policy all identify human resources issues of attracting and retaining workers as the most pressing challenge facing Canada’s health care system (see, for example, the Health Council of Canada, 2005, the CHSRF, 2002, and Dault, Lomas and Barer, 2004).

The purpose of this study is to examine the associations between work intensification, stress and job satisfaction. Our study contributes to human resource knowledge by examining one outcome of health sector reform, i.e. work intensification, on nurses’ health and well-being, and attitude towards their jobs.

Background on Health Sector Reform and Its Effect on Nurses

Nurses experienced health sector reform in the first half of the 1990s in Canada (Bourbonnais et al., 2005; Wetzel, 2005b). Health care work environments changed with many nurses experiencing successive rounds of downsizing and layoffs (Tepper and Larente, 2004). Job insecurity became a part of nursing in the early- to mid-1990s. Nurses who survived the layoffs were expected to be more productive and care for an increased number of acutely ill patients (RNAO, 2003). Nurses felt overworked, stressed and betrayed by their organizations (Baumann et al., 2001). Their job satisfaction decreased as they provided complex care to a large number of patients (O’Brien-Pallas et al., 2004). Sick leave increased during restructuring (Bourbonnais et al., 2005), and many nurses left their positions due to increased workloads (Tepper and Larente, 2004).

With this background, we conducted our study in 2002. Although nurses were considered surplus in the early 1990s and many jobs were eliminated, by the time we conducted our study shortages existed and were expected to persist. Nurse managers and human resource managers in the three teaching hospitals included in our study and policy makers in the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario were increasingly concerned about the quality of nurses’ working lives and the effect of health sector reform on nurses’ job satisfaction and retention. Managers and policy makers desired evidence on factors that affect nurses’ job satisfaction. Such evidence would allow managers and policy makers to take measures to alleviate nursing shortages and retention problems. The managers gave the research team access to survey nurses employed in their hospitals. The 949 nurses who had worked in their employing hospital since the early 1990s provided a sample for measuring their feelings on work intensification and its association with stress and job satisfaction.

The Theory and the Conceptual Model of Factors Associated With Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is studied in the academic disciplines of economics, sociology and psychology, and the interdisciplinary fields of industrial relations (Meltz, 1993) and human resources (Lawler III, 1973, 2005). Each of these disciplines takes a different disciplinary perspective which contributes to the theoretical foundations of job satisfaction. In this study, we incorporate the individual choice and labour market perspectives of economists (see, for example, Hamermesh, 1977), the structural work environment and work context perspectives of sociologists (see, for example, Ducharme and Martin, 2000), and the individual personality focus of psychologists (see, for example, Judge and Watanabe, 1993; Spector, 1997). The overarching framework of the study is the industrial relations systems framework (Dunlop, 1958) where strategic choices of decision-makers shape employees’ working conditions (Kochan, Katz and McKersie, 1986) and affect their job satisfaction. Applying this theoretical foundation to the health care sector, the strategic decision of the federal government in the 1990s to cut transfer payments to provinces initiated a system-wide change and reform in provincial health care sectors (Wetzel, 2005b). This, in turn, led to the reforms which restructured hospitals and reshaped nurses’ work and working conditions. Within this changed organizational environment context, we examine nurses’ views of their work intensification, feelings of stress and job satisfaction, and the associations between these factors. Job satisfaction is the major worker outcome variable we focus on in this study. Job satisfaction is a construct of workers’ feelings about their jobs and includes nine facets (Spector, 1997). Each facet contributes to the feeling of ‘overall’ job satisfaction, and there are no definitive predictions about which facets are most important in determining overall job satisfaction. In this study we join these nine different facets of job satisfaction to form two summary constructs: satisfaction with financial rewards, and satisfaction with the work and work environment. These are two distinct components of job satisfaction and it is possible that the associations between work intensification and stress are different for each. We use these two summary constructs of job satisfaction in our study.

The feeling of work intensification is the major factor we examine as associated with job satisfaction. Although there are no studies in Canada examining the effect of work intensification on job satisfaction, macro-level analysis and case studies from Europe show that job satisfaction declines as work becomes intense (Boisard et al., 2003a, 2003b; Burchell and Fagan, 2002; Green and Tsitsianis, 2005; Wichert, 2002). Work intensification is seen across occupations and sectors, though women, people older than 40 and service-sector and public sector workers perceive more of an increase in work effort (Green, 2004). In Canada, concerns are being raised about how nurses’ fast pace, time pressures and intense work affect their commitment, job satisfaction and the overall quality of their work life (Baumann et al. 2001; Blythe, Baumann and Giovannetti, 2001). A European study (Hasselhorn et al., 2005) and a study in progress in Canada (O’Brien-Pallas et al., 2004) are showing an inverse relationship between work intensification and job satisfaction for nurses.

Canadian workers show high levels of stress (Wilkins and Beaudet, 1998; Williams, 2003), and research shows that work intensification leads to stress and has long-term detrimental effects on workers’ psychological health and well-being (Boisard et al., 2003a, 2003b; Merllié and Paoli, 2001; Wichert, 2002). We examine stress as an individual worker health and wellness outcome as well as a mediator of work intensification on job satisfaction.

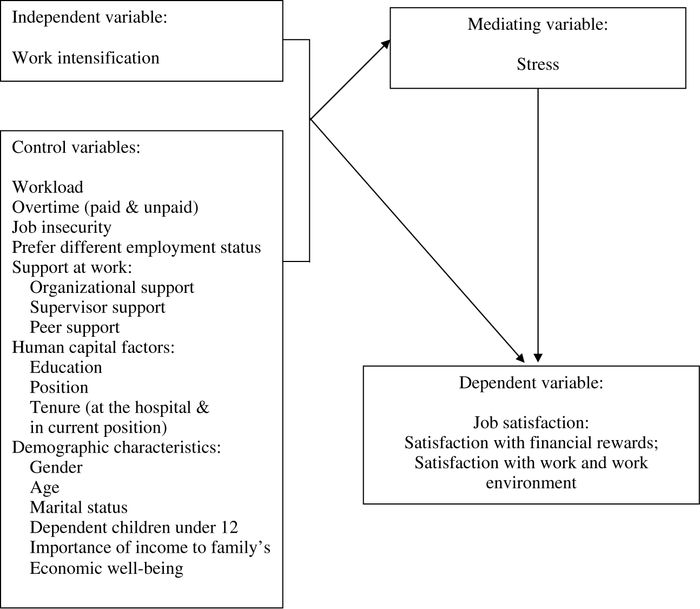

Based on the literature to date, we expect to find nurses’ work intensification to be associated with increased stress and decreased job satisfaction, and stress to mediate the effect of work intensification on job satisfaction. Effects of other factors, such as work and work environment, human capital and personal characteristics that are demonstrated in earlier research as affecting job satisfaction, are controlled for in our study. The relationships between these factors are schematically presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Conceptual Model of Associations between Work Intensification, Stress and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Ontario

Methodology

Data and Data Collection Process

Data are collected from three large teaching hospitals in Southern Ontario, Canada. Each hospital provides tertiary level care and has more than 400 beds. This study is limited to a purposeful sample of three hospitals that experienced restructuring due to health sector reform in Ontario. Focusing on a small number of sites allows examination of the issues in greater depth. One hospital is situated in a large city and the other two in medium-sized cities. All three are in densely populated areas of the country. The large-city hospital is one of the larger employers of nurses in that city, and the hospitals in medium-sized cities are the largest employers of nurses in their respective cities. Data for the study come from our survey of 949 nurses employed in these hospitals prior to the health sector reform.

All nurses in each institution are selected for the study. The total population of nurses in these three hospitals is 2,684. All nurses employed in these hospitals are included in the sample because the multivariate statistical analysis that we conduct using a large number of dependent variables and independent variables with many control factors requires a large sample size of about 1,500 respondents. In addition, we aimed for a 50% response rate from the surveyed nurses to give us a good representation of the nurses’ population in each hospital. Data are collected through a mail out questionnaire following the usual surveying procedures of pilot testing, first mail-out, sending a reminder card and a second mail out (all conducted in 2002). In both mail-outs a small incentive (a $2 coupon of a locally popular cafe chain) was included. A total of 1,396 nurses responded, representing a response rate of 52%. The respondents are representative of the nursing population at the three hospitals as the comparison of human resources data in terms of gender, age and tenure show. This study focuses on the 949 nurses (of the 1,396 nurses who responded) who are employed since the 1990s.

Instrument

The New Health Care Worker Questionnaire is the instrument for data collection. Most questions are either developed by the research team for this survey or adapted from the Health and Worklife Questionnaire (Denton et al., 2002a). Some questions are adapted from other studies (as referenced below). The questionnaire is divided into several sections. The employment status and worklife section includes job satisfaction questions, and the restructuring section has questions on work intensification. A health section incorporates a set of questions on symptoms of stress. The survey also includes questions on other work environment, human capital and personal characteristic factors.

Variables

The dependent variable of job satisfaction uses Spector’s 1985 Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) (1997). The JSS assesses nine facets of job satisfaction consisting of 36 items. The scale responses are on a five-point scale from “1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.” To create scores for each subscale, responses to each item are summed together. In creating the scales some of the items are reverse-scored. Most job satisfaction sub-scales have high reliabilities (alpha above .70) except for satisfaction with rules and procedures and satisfaction with co-workers sub-scales (with alpha’s .62 and .60) (Spector, 1997). The two sub-scales, satisfaction with financial rewards and satisfaction with work and work environment, that we use here show good reliability with high Cronbach’s alphas (see Table 1).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics, Scale Reliabilities and Range of All Variables (Means, standard deviations or proportions, scale reliabilities and ranges) N = 949

Variables |

% |

Mean (S.D.) |

Scale Reliability (α) |

Scale Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dependent Variables |

|

|

|

|

Satisfaction with financial rewards |

|

33.7 (6.5) |

.81 |

12-60 |

Satisfaction with work and work environment |

|

76.6 (11.1) |

.86 |

24-120 |

Mediating Variable |

|

|

|

|

Stress (symptoms of stress) scale |

|

32.5 (7.9) |

.87 |

14-70 |

Item percentages: |

|

|

|

|

I feel exhausted at the end of the day |

48 |

|

|

|

I am not feeling energized on the job |

31 |

|

|

|

I am not able to sleep through the night |

22 |

|

|

|

I feel burnt out most or all of the time |

15 |

|

|

|

There is nothing more to give |

12 |

|

|

|

I have little or no control over my life |

10 |

|

|

|

Others: |

8 to 1 |

|

|

|

I feel irritable and tense, suffering from headaches or migraines, feeling helpless, feeling like yelling at people, feeling angry, like crying, having difficulty concentrating, feeling dizzy |

|

|

|

|

Independent Variable |

|

|

|

|

Work intensification scale |

|

24.2 (3.9) |

.80 |

6-30 |

Item percentages: Compared to early 1990s, |

|

|

|

|

My work intensity is higher |

91 |

|

|

|

My workload is heavier |

84 |

|

|

|

Nurses are assigned more patients per shift |

71 |

|

|

|

The amount of unpaid work I do increased |

53 |

|

|

|

There are fewer nurse leaders |

73 |

|

|

|

Patient complexity has increased |

94 |

|

|

|

Control variables |

|

|

|

|

Workload |

|

20.5 (4.5) |

.85 |

6-30 |

Paid overtime |

27 |

|

|

|

Unpaid overtime |

22 |

|

|

|

Job insecurity |

|

15.6 (5.1) |

.89 |

7-35 |

Prefer different status |

21 |

|

|

|

Support at work: |

|

|

|

|

Organizational |

|

16.2 (3.8) |

.73 |

6-30 |

Supervisor |

|

19.0 (5.5) |

.94 |

6-30 |

Peer |

|

15.5 (2.5) |

.82 |

4-20 |

Education |

|

|

|

|

University degree or higher |

19 |

|

|

|

Lower than university degree |

81 |

|

|

|

Position |

|

|

|

|

RN |

91 |

|

|

|

RPN |

9 |

|

|

|

Tenure in the position (in months) |

|

122.9 (94.5) |

N/A |

|

Tenure at the hospital (in months) |

|

203.1 (101.3) |

N/A |

|

Gender (Female) |

97 |

|

|

|

Age |

|

45 (8.2) |

N/A |

|

Marital status: |

|

|

|

|

Married/Common Law |

75 |

|

|

|

Widowed |

2 |

|

|

|

Divorced/Separated |

10 |

|

|

|

Never Married |

12 |

|

|

|

Other |

1 |

|

|

|

Child(ren) under 12 |

41 |

|

|

|

The importance of income to family’s economic well-being |

|

4.43 (.83) |

|

Item range: 1-5 |

Work intensification is the independent variable in our study. Since there is no well-accepted measurement of work intensification, a variety of measures appear in the literature (Burchell, 2002, Green, 2004). Our study uses a perceived work intensification measure developed based on qualitative studies of restructured nursing work environments in hospitals (Baumann et al., 2003) and in home care (Denton, Zeytinoglu and Davies, 2003). We use a perception based measure because when exposed to the same objective situation of increased workload, the feeling of whether work intensification occurred may differ from one individual to another. While some may consider increased workload as work intensification, others may consider increased workload as the appropriate level of workload for their job and do not perceive work intensification. One other reason for using a perception-based measure is that the objective data on nursing workload in Ontario, from which one can calculate workload change, is not reliable as Scott (2006) presented in a symposium sponsored by the Dr. O’Brien-PallasCHSRF/CIHR Chair in Nursing/Health Human Resources. Scott’s study found that objective nursing workload data collected for the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario has serious flaws.

Perceptions show one’s feelings. Although what we perceive can be different from reality, perceptions are important because employees’ attitudes, such as job satisfaction, are based on the perception of what reality is, not on reality itself (Robbins and Langton, 2003). A perceived work intensification measure can capture all aspects that might contribute to the feeling of work intensification (Burchell, 2002). Research shows sufficient reliability to consider perception based measures to be accurate (Spector et al., 2000).

Our work intensification measure starts by stating that “There have been many changes in the health care system since the early 1990s. Comparing the present time to the early 1990s, please indicate if you agree or disagree with each statement.” The items are: “my work intensity is higher; my workload is heavier; nurses are assigned more patients per shift; the amount of unpaid work I do increased; there are fewer nurse leaders; and patient complexity has increased.” Responses are collected on a five-point Likert scale with “1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree” and the scores are summed to create the work intensification measure. We conducted factor analysis using Principal Component Analysis extraction method. One component is extracted. The work intensification measure shows a good reliability with high Cronbach’s alpha = .80 (see Table 1). In terms of the external consistency of the measure, our sample is comparable to other studies that found greater work intensification in the health care and social work sector (Boisard et al., 2003b), for women (Burchell and Fagan, 2002) and for workers in the public sector (Green, 2004).

The symptoms of stress scale (Denton et al., 2002b) is the mediating variable in this study. Stress has been studied in medical, behavioural and social science research over the past 60 years, but there are wide discrepancies in the literature on how experts define and operationalize stress, and there are numerous scales to measure stress (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll, 2001). In this study stress refers to self-reported symptoms occurring as a result of transactions between the individual and the environment (Lazarus, 1990). Respondents are presented with 14 symptoms of stress statements. These statements are, for example, feeling exhausted at the end of the day, not being able to sleep through the night, (not) feeling energized on the job. Participants are asked how often they felt this way during the past month and gave their responses on a five-point scale with “1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time.” The stress scale is obtained by summing these stress symptoms. Stress scores range from 14 (lowest) to 70 (highest) stress score. The scale shows a good reliability with high Cronbach’s alpha (see Table 1).

Control variables refer to factors that have been found in previous research to affect job satisfaction. Heavy workload (Clark, 2005) and overtime are well-known factors that decrease job satisfaction. The workload scale (Denton et al., 2002b) consists of statements that a person might use to describe his/her job situation and asks respondents to indicate whether they agree or disagree with the statements of “my workload is heavy; my job requires that I do more with less; I work at home in order to complete my work; my job requires a high level of skill; my job is very complex.” It focuses on the complexity of nurses’ work environment as suggested by Hayes et al. (2006). The responses for workload questions are coded on a Likert scale with “1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.” The summative scale has a very good reliability with high Cronbach’s alpha (see Table 1). Note that this variable refers to current working conditions whereas work intensification asks about changes in workload. Paid and unpaid overtime is measured by asking respondents if they had worked paid overtime and if they had worked unpaid overtime in the last two week pay period. Responses to each of these questions are dichotomized with “1 = Yes, worked overtime, and 0 = No, not worked overtime.”

Research also shows that feelings of job security contribute to increased job satisfaction (Rose, 2005) and conversely that job insecurity decreases job satisfaction (Chirulombolo and Hellgren, 2003). The job insecurity scale is adapted from Cameron, Horsburgh and Armstrong-Stassen (1994). It uses seven items regarding workers’ feelings or worries about their future employment at their respective hospitals to measure job security. Sample statements are “I am presently safe from dismissal at this hospital. I am worried about my future with this hospital. I am worried about my job security.” Responses are given on a Likert scale with “1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.” The summative scale shows a good reliability with high Cronbach’s alpha (see Table 1).

Prefer different employment status is included as a control variable since research shows that it is not the current employment status but whether nurses are employed in their preferred employment status that affects their stress (Zeytinoglu et al., 2006). Our survey asks nurses first about their current employment status. They are given response options of “full-time,” “part-time,” or “casual.” This is followed by the question “would you prefer a different employment status?” and a “yes = 1 or no = 0” response is selected.

Lack of support at work is another important factor decreasing job satisfaction (Jex and Crossley, 2005). Three types of support at work are controlled for in this study. Organizational support and supervisor support scales are each measured using a six-item Likert scale and peer support is measured using four items (Denton et al., 2002b). Scales show a good reliability with high Cronbach’s alpha (see Table 1).

Other control variables that can affect job satisfaction include human capital and personal characteristics. As a literature review by Hayes et al. (2006) shows, low job satisfaction is concentrated in highly educated, newly qualified and young nurses. Those with more years of work experience report higher job satisfaction. Education is coded as “1 = university degree; 0 = other,” position is coded as “1 = RPN, 0 = RN,” tenure is measured as months worked at the hospital and months worked in the current position. Personal characteristics can affect job satisfaction and the ones included here are gender coded as “1 = female, 0 = male,” age coded in years, marital status coded as “married or common law, widowed, divorced, never married, and other,” and child(ren) under age 12 coded as “1 = yes, 0 = no.” Zeytinoglu et al. (2006) showed that the importance of income to a nurse’s family affected nurses’ turnover intentions. Since job satisfaction is an attitude closely associated with turnover intention, we assume that importance of income to family’s economic well-being can affect job satisfaction and controlled for in the analysis. It is measured as a single item with a five-point Likert scale coded as “1 = not at all important to 5 = very important.”

Analysis

We begin analysis with descriptive statistics giving means, standard deviations, proportions, Cronbach’s alphas for scale reliabilities, and the range of each scale. Next we show correlations between key dependent, mediating and independent variables. Following that, we proceed to multivariate analysis of the ordinary least square (OLS) regression analysis. The OLS regression shows the association between the independent variable and the dependent variable when all other factors are controlled for. To show the variance explained by these factors, we provide Adjusted R2. Since the subjectively assessed variables may not be completely independent of each other, collinearity diagnostics are also conducted. Since collinearity is not found, they are not reported here. The mediation effect of stress is tested using the three-stage mediation test of Baron and Kenny (1986).

Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of this study is that, as a cross sectional study, we are able to show associations but cannot show causal relationships. Despite that limitation, this is one of the few studies to focus on work intensification and perhaps others can consider the issues identified in our study and conduct longitudinal analysis to show causal relationships. The second limitation of our study is that it is a case study of three hospitals. Since our respondents work in hospitals in Southern Ontario, it is not possible to generalize our results to nurses elsewhere. In addition, because we focused on three large hospitals, we must be cautious of generalizing to all nurses. Nurses employed by large hospitals may have different attitudes and experiences from nurses employed by smaller hospitals, clinics and other work settings. Also, since teaching hospitals may differ from non-teaching hospitals, results cannot be generalized to all hospitals. Thus, the location, the size and the type of the hospital affect the generalizability of results. Having said this, it is important to note that the study allowed an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon of work intensification as it affects job satisfaction.

Third, we caution readers that the work intensification measure consists of negatively worded statements and the lack of positive statements can create bias in responses. At the time when we were constructing the study we were exploring the phenomenon and decided to include what nurses and other employees said in qualitative studies of Baumann et al. (2003) and Denton, Zeytinoglu and Davies (2003). Though the measure is not perfect, our justification is that using that to explore this growing phenomenon is better than not examining it.

Fourth, work intensification, stress and job satisfaction are subjective measures that can be considered as closely related to each other. However, they are conceptually different and are processed sequentially in the minds of an individual. Workers’ feelings of work intensification are derived from their perceptions of the work environment. Work intensification affects their emotional health and well-being contributing to their stress, and the stress, in turn, affects their job satisfaction.

Characteristics of the Respondents and their Working Conditions

Personal and human capital characteristics of our respondents and their working conditions are presented in Table 1 to give context to our findings on work intensification, stress and job satisfaction.

Almost all nurses responding to our survey are women. The average age of the respondents is 45. Three-quarters are married and 41% have a child or children under age 12. They consider earnings from their nursing jobs to be important to their family’s economic well-being. In terms of human capital characteristics, about one in five has a university degree or above, and most of the respondents (91%) work as RNs. Respondents have an average of about 17 years of tenure at their hospitals and 10 years in their current positions.

In terms of working conditions, nurses feel their workloads are high and their jobs are insecure; 27% say they work paid and 22% say they work unpaid overtime. About one in five nurses would prefer to work in a different job status than she is employed in. Support at work scales show that nurses feel supported by their supervisor(s) and co-workers but feelings of support by their hospital is not strong.

Results

Descriptive Results

Results show that nurses are somewhat satisfied with the financial rewards (M = 33.7, S.D. = 6.5) and moderately satisfied with their work and work environment (M = 76.6, S.D. = 11.1) (see Table 1). In terms of work intensification, survey responses show a general perception that work intensification (M = 24.2, S.D. = 3.9) has occurred over the past decade. In particular, 90% or more agree that their work intensity is higher now. More than 80% of nurses feel they have heavier workloads, and over 70% agree they are being assigned more patients per shift. More than half say that the amount of unpaid work they do increased. Over 70% of nurses agree that they have fewer nurse leaders. Lastly, 90% agree that patient complexity has increased.

The symptoms of stress measure shows that nurses are feeling stressed (M = 32.5, S.D. = 7.9). The levels of stress they show should be considered high since this is a working population, not clinically sick workers. Close to half (48%) say that they feel exhausted at the end of the day. Thirty-one percent of nurses report not feeling energized on the job. With regards to not being able to sleep through the night, 22% of nurses respond affirmatively. Nearly 15% of nurses say they feel burnt out most or all of the time. Some nurses feel like there is nothing more to give (12%), while over 10% feel like they have little or no control over their lives. Other items are (in declining order ranging from 8% to 1%): feeling irritable and tense, suffering from headaches or migraines, feeling helpless, feeling like yelling at people, feeling angry, feeling like crying, having difficulty concentrating, and feeling dizzy.

Correlations

With respect to satisfaction with financial rewards, work intensification and stress are significantly and negatively correlated (–.282, p ≥ .01 and –.323, p ≥ .01, respectively). With regards to satisfaction with work and work environment, work intensification and stress are again significantly and negatively correlated (–.343, p ≥ .01 and –.502, p ≥ .01, respectively). In terms of the correlation between stress and two forms of job satisfaction, stress is more highly correlated with satisfaction with work and work environment than satisfaction with financial rewards.

Table 2

Correlations between Dependent, Independent and Mediating Variables (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients)

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Satisfaction with financial rewards |

--- |

|

|

|

2. Satisfaction with work and work environment |

.490** |

--- |

|

|

3. Work intensification |

‑.282** |

‑.343** |

--- |

|

4. Stress |

‑.323** |

‑.502** |

.298** |

--- |

* p < .05 ** p < .01

Regression Results

Using multiple regression analysis, we show the association between our independent variable and the two dependent variables controlling for many other factors. We examine the association of work intensification with stress before testing to see if stress is a mediating variable. Focusing on the association between work intensification and stress, Table 3 (Column 2) shows that work intensification is significantly (p < .05 level) and positively associated with stress. Workload, feelings of job insecurity, preferring a different employment status, and the importance of income to family’s economic well-being also have significant and positive associations with stress. Organizational support and age (being older) are significantly and negatively associated with stress.

Table 3, Column 3 shows that work intensification is significantly (p < .01 level) and negatively associated with satisfaction with financial rewards. This finding is in line with our expectation that work intensification would be associated with lower job satisfaction among nurses. Other factors that are significantly and negatively associated with satisfaction with financial rewards are working as an RPN, workload, and longer tenure at the current position. Organizational support and supervisory support are significantly and positively associated with satisfaction with financial rewards. The other factors in our model are not significantly associated with satisfaction with financial rewards.

The final model (see Table 3, Column 4) demonstrates that stress is significantly and negatively associated with satisfaction with financial rewards. Stress partially mediates the effect of work intensification. Of the control variables, the effect of workload on satisfaction with financial rewards is partially mediated through stress. Factors that remain significant in the final model (Table 3, Column 4) are organizational and supervisory support (significant and positive), position and tenure in the current position (significant and negative). Other factors are not significantly associated with satisfaction with financial rewards. The model for satisfaction with financial rewards is healthy, explaining 29% of the variance.

Table 3

Factors Associated with Nurses’ Stress and Satisfaction with Financial Rewards

|

Stress |

Satisfaction with Financial Rewards |

Final Model of Satisfaction with Financial Rewards |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(Column 2) |

(Column 3) |

(Column 4) |

|

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

Constant |

23.127 (4.419) |

34.130 (3.449) |

36.302 (3.493) |

|

|

|

|

Work intensification |

.167 (.078)* |

‑.164 (.061)** |

‑.149 (.061)* |

Stress |

----- |

----- |

‑.094 (.029)** |

|

|

|

|

Workload |

.507 (.070)*** |

‑.195 (.054)*** |

‑.147 (.056)** |

Paid overtime |

‑.697 (.578) |

.075 (.451) |

.009 (.449) |

Unpaid overtime |

.476 (.656) |

.459 (.512) |

.503 (.509) |

Job insecurity |

.179 (.058)** |

‑.086 (.045) |

‑.069 (.045) |

Prefer different status |

1.850 (.625)** |

‑.802 (.488) |

‑.628 (.487) |

Organizational support |

‑.402 (.090)*** |

.445 (.070)*** |

.407 (.071)*** |

Supervisory support |

‑.064 (.056) |

.148 (.044)** |

.142 (.044)** |

Peer support |

‑.189 (.107) |

‑.073 (.084) |

‑.091 (.083) |

Education |

‑.129 (.679) |

.536 (.530) |

.524 (.527) |

Position (RPN=1, RN=0) |

‑1.274 (1.003) |

‑3.966 (.783)*** |

‑4.085 (.779)*** |

Tenure at the hospital |

.006 (.004) |

.001 (.003) |

.001 (.003) |

Tenure in current position |

‑.001 (.003) |

‑.005 (.003)* |

‑.005 (.003)* |

Gender |

1.842 (1.429) |

1.335 (1.115) |

1.507 (1.109) |

Age |

‑.090 (.046)* |

.030 (.036) |

.021 (.036) |

Marital status: |

|

|

|

Married/C.Law (Ref) |

----- |

----- |

----- |

Widowed |

.219 (2.148) |

1.030 (1.676) |

1.050 (1.665) |

Divorced/Separated |

‑.216 (.949) |

.784 (.741) |

.764 (.736) |

Never married |

‑.948 (1.307) |

‑1.876 (1.020) |

‑1.786 (1.014) |

Other |

1.227 (3.133) |

‑.445 (2.445) |

‑.330 (2.429) |

Child(ren) under 12 |

.290 (.637) |

‑.211 (.497) |

‑.184 (.494) |

Importance of income to family’s economic well-being |

.892 (.314)** |

‑.386 (.245) |

‑.302 (.245) |

|

|

|

|

Adjusted R2 |

.267 |

.280 |

.290 |

*p < .05 ** p < .01 ***p < .001

The findings shown in Table 4 help to underscore the influence that work environment factors have on nurses’ satisfaction with the work and work environment. The results on stress (in Table 4, Column 2) are a repeat of the previous table (Table 3, Column 2), and therefore explanations are not reviewed again.

Focusing on Column 3 of Table 4, work intensification is significantly (though only at p < .05 level) and negatively associated with satisfaction with work and work environment. Among control variables, workload, job insecurity and tenure in current position are all significantly and negatively associated with nurses’ satisfaction with their work and work environment, while the three forms of support at work are positively and significantly associated with satisfaction with work and work environment.

In the Final Model, as presented in Table 4, Column 4, when stress is included in the model, the significance level of work intensification is diminished to non-significant, suggesting that stress is a mediator of work intensification in relation to satisfaction with work and work environment. Other associated factors that were significant, i.e. workload (negative), all three forms of support at work (positive), and tenure in current job (negative) remain similarly significant when stress is included in the model. The effect of job insecurity is also completely mediated through stress. It is noteworthy that our model of satisfaction with work and work environment explains almost 68% of the total variance. Generally speaking, the results show that our variables explain the variance for satisfaction with work and work environment better than the variance for satisfaction with financial rewards.

Conclusions and Discussion

The results of our study show that nurses feel stressed and moderately satisfied with their jobs. They also perceive that their work has intensified after the health sector reform of the 1990s. Wetzel (2005a) suggested that health sector reforms can have long-term effects on staff, and their work can become intensified and stressful. Our study confirms Wetzel’s predictions for nurses, and shows that perceived work intensification is a significant factor contributing to nurses’ increased stress levels. This stress, in turn, decreases their job satisfaction. Noting that health human resources issues of attracting and retaining health care staff are considered as the most pressing challenge for managers in Canada’s health care system (Dault, Lomas and Barer, 2004; the Health Council of Canada, 2005), our results are important. They explain why nurses feel stressed and how this stress contributes to their decreased job satisfaction.

Table 4

Factors Associated with Nurses’ Stress and Satisfaction with Work and Work Environment

|

Stress |

Satisfaction with Work and Work Environment |

Final Model of Satisfaction with Work and Work Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(Column 2) |

(Column 3) |

(Column 4) |

|

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

Constant |

23.127 (4.419) |

59.730 (4.134) |

64.798 (4.099) |

|

|

|

|

Work Intensification |

.167 (.078)* |

‑.172 (.073)* |

‑.135 (.071) |

Stress |

---- |

----- |

‑.219 (.034)*** |

|

|

|

|

Workload |

.507 (.070)*** |

‑.706 (.065)*** |

‑.595 (.066)*** |

Paid overtime |

‑.697 (.578) |

‑.616 (.541) |

‑.769 (.527) |

Unpaid overtime |

.476 (.656) |

.019 (.614) |

.123 (.597) |

Job insecurity |

.179 (.058)** |

‑.109 (.054)* |

‑.070 (.053) |

Prefer different status |

1.850 (.625)** |

‑.905 (.584) |

‑.500 (.572) |

Organizational support |

‑.402 (.090)*** |

.734 (.084)*** |

.646 (.083)*** |

Supervisory support |

‑.064 (.056) |

.718 (.053)*** |

.704 (.051)*** |

Peer support |

‑.189 (.107) |

.802 (.100)*** |

.760 (.098)*** |

Education |

‑.129 (.679) |

.117 (.635) |

.089 (.618) |

Position (RPN=1, RN=0) |

‑1.274 (1.003) |

.263 (.938) |

‑.017 (.914) |

Tenure at the hospital |

.006 (.004) |

.001 (.003) |

.003 (.003) |

Tenure in current position |

‑.001 (.003) |

‑.006 (.003)* |

‑.006 (.003)* |

Gender |

1.842 (1.429) |

‑.880 (1.337) |

‑.477 (1.302) |

Age |

‑.090 (.046)* |

.038 (.043) |

.018 (.042) |

Marital status: |

|

|

|

Married/C.Law (Ref) |

----- |

----- |

----- |

Widowed |

.219 (2.148) |

‑1.274 (2.009) |

‑1.226 (1.955) |

Divorced/Separated |

‑.216 (.949) |

‑.052 (.888) |

‑.099 (.864) |

Never married |

‑.948 (1.307) |

‑1.972 (1.223) |

‑1.764 (1.190 |

Other |

1.227 (3.133) |

1.729 (2.930) |

1.998 (2.851) |

Child(ren) under 12 |

.290 (.637) |

‑.966 (.596) |

‑.902 (.580) |

Importance of income to family’s economic well-being |

.892 (.314)** |

‑.095 (.294) |

.101 (.288) |

|

|

|

|

Adjusted R2 |

.267 |

.657 |

.675 |

*p < .05 ** p < .01 ***p < .001

Our study shows that there are other factors, in addition to work intensification, associated with nurses’ stress and job satisfaction. First, focusing on stress as an individual worker outcome, our results show that nurses who prefer to be employed in a different job status, such as working part-time but wanting to work full-time, are also the ones reporting stress. Nurses who continue to be employed in their jobs because of the importance of their income for their family’s economic well-being also report symptoms of stress. Heavy workload and perceived lack of organizational support are additional factors contributing to nurses’ increased stress. Our findings give further support to literature which demonstrates an association between perceptions of job insecurity and increased stress (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll, 2001; Chirumbolo and Hellgren, 2003). The association of age with stress is well established in literature (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll, 2001) and our study shows similar results: as nurses age, their stress levels decrease. The factors included in our model, taken together, explain about 27% of nurses’ stress.

Turning to results on satisfaction with financial rewards, our study confirms that in addition to the significant effects of work intensification and stress, working as an RPN, heavy workload and longer tenure are factors which decrease satisfaction with financial rewards. Organizational and supervisory support, however, counteract the negative effects of the above factors, contributing to increased satisfaction with financial rewards. The model, taken together with the variables, explains about 30% of nurses’ satisfaction with financial rewards of their job.

For satisfaction with work and the work environment, as we mentioned above, the effect of work intensification is partially included in their stress, and the effect of job insecurity is completely absorbed in their stress. Stress, in turn, contributes to their decreased satisfaction with work and work environment. While heavy workload and longer tenure in the position are factors contributing to dissatisfaction with work and work environment, the effects of social support at work are major factors affecting this facet of job satisfaction. Our results show that if nurses feel supported by their hospital, supervisor and co-workers, their satisfaction with work and their work environment increases significantly. It is important for managers and policy makers to pay attention to the factors included in our study since, taken together, they explain 68% of nurses’ satisfaction with work and work environment. In conclusion, our results provide empirical support to the literature which suggests that work intensification has an adverse effect on workers’ health and well-being, and work attitudes. The findings of nurses’ feelings of work intensification and its association with their stress and job satisfaction are in line with the findings of macro-level analysis (Boisard et al., 2003b; Burchell and Fagan, 2002; Green, 2004) and case studies in Europe (Wichert, 2002). Examining work intensification and stress can contribute to our understanding of how health sector reforms of the 1990s affected nurses’ job satisfaction. At a time when the health care sector is attempting to attract nurses to the profession and retain nurses in the profession, policy-makers and managers have to consider the adverse affects of their strategic decisions and actions on nurses’ health and well-being, and work attitudes. We strongly recommend decision-makers at all levels, and in particular policy-makers, pay attention to the long-term effects of the strategic decisions on staff.

As our study is limited in geographical scope and to a single occupation, we suggest replication of it in other health care settings and at the national level to provide empirical results that can be generalized to Canadian workers. We argue that the experiences of nurses in the three teaching hospitals in Southern Ontario are not unique to this group of workers. It is possible that work intensification is a factor in high levels of stress that Canadian workers are reporting in Wilkins’ and Beaudet’s (1998) and Williams’ (2003) studies. Many workplaces experienced restructuring in the 1980s and 1990s, and while some workers were forced into early retirement or laid off, others who continued to work carried the workload of their job and of others whose jobs were eliminated. There are no studies in Canada examining whether work intensification occurred in the last two decades’ restructuring in health care and in other sectors. Further studies can examine work intensification, stress and job satisfaction associations to corroborate our findings or provide alternative explanations on the effects of organizational changes on Canadian workers.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the views of the granting organizations. Assistance of A. Higgins in survey preparation and distribution is greatly appreciated. Earlier version of this paper were presented at the SafetyNet and Canadian Association for Work and Health (CARWH) 2006 International Conference in St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador, and at Practice to Policy Global Perspectives on Nursing 2006 Conference in Hamilton, Ontario.

References

- Baron, R. M., and D. A. Kenny. 1986. “The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173–1182.

- Baumann, A., L. O’Brien-Pallas, M. Armstrong-Stassen, J. Blythe, R. Bourbonnais, S. Cameron, D. Doran, M. Kerr, L. Hall, M. Zina, M. Butt and L. Ryan. 2001. “Commitment and Care: The Benefits of a Healthy Workplace for Nurses, their Patients and the System.” Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and The Change Foundation Commissioned Paper, Ottawa, Ontario.

- Baumann, A., J. Blythe, M. Denton, I. Zeytinoglu, A. Higgins and S. Davies. 2003. Summary of the Qualitative Results from the New Health Care Worker: The Implications of Changing Employment Patterns. Nursing Effectiveness, Utilization and Outcomes Research Unit, McMaster University Site.

- Blythe, J., A. Baumann and P. Giovannetti. 2001. “Nurses’ Experiences of Restructuring in Three Ontario Hospitals.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33 (1), 61–68.

- Boisard, P., D. Cartron, M. Gollac and A. Valeyre. 2003a. Time and Work: Duration of Work. Dublin, IE: European Foundation.

- Boisard, P., D. Cartron, M. Gollac, A. Valeyre and J.-B. Besanchon. 2003b. Time and Work: Work Intensity. Dublin, IE: European Foundation.

- Bourbonnais, R., C. Brisson, M. Vézina, B. Masse and C. Blanchette. 2005. “Psychosocial Work Environment and Certified Sick Leave among Nurses during Organizational Changes and Downsizing.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 60 (3), 483–509. Burchell, B. 2002. “The Prevalence and Redistribution of Job Insecurity and Work Intensification.” Job Insecurity and Work Intensification. B. Burchell, D. Ladipo and F. Wilkinson, eds. London: Routledge, 61–76.

- Burchell, B., and C. Fagan. 2002. “Gender and the Intensification of Work: Evidence from 2000 European Working Conditions Survey.” Paper presented at the Work Intensification Conference, Paris, November.

- Cameron, S., M. Horsburgh and M. Armstrong-Stassen. 1994. “Effects of Downsizing on RNs and RNAs in Community Hospitals.” Working Paper Series 94–6. Hamilton, Ontario, McMaster University and University of Toronto, Nursing Effectiveness, Utilization and Outcomes Research Unit.

- Catlin, G. 2001. “How Healthy are Canadians? 2001 Annual Report. Stress and Well-Being.” Health Reports, 12 (3), 21–32.

- Chirulombolo, A., and J. Hellgren. 2003. “Individual and Organizational Consequences of Job Insecurity: A European Study.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 24 (2), 217–240.

- CHSRF (Canadian Health Services Research Foundation). 2000. The Merger Decade: What Have we Learned from Canadian Health Care Mergers in the 1990s? A Report on the Conference on Health Care Mergers in Canada. Organized by the Ottawa Hospital and the Association of Canadian Teaching Hospitals. Ottawa, Ontario: CHSRF. CHSRF. 2002. Issue/Survey Paper: Health Human Resources in Canada’s Health Care System. Ottawa, Ontario: Prepared by Canadian Health Service Research Foundation for the (Romanow) Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

- Clark, A. E. 2005. “Your Money or Your Life: Changing Job Quality in OECD Countries.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43 (3), 377–400. Cooper, C. L., P. J. Dewe and M. O’Driscoll. 2001. Organizational Stress: A Review and Critique of Theory, Research, and Applications. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

- Dault, M., J. Lomas and M. Barer (on behalf of the Listening for Directions II partners). 2004. Listening for Directions II: National Consultation on Health Services Policy Issues for 2004–2007, Final Report. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and Institute for Health Services and Policy Research, CIHR, <http://www.chsrf.ca> (downloaded in February 2006).

- Denton, M., I. Zeytinoglu and S. Davies. 2002a. Health and Worklife Questionnaire. M. Denton as the PI of the research grant, funded by the WSIB under Organizational Change and Health and Well-Being of Home Care Workers research project.

- Denton, M., I. Zeytinoglu, S. Davies and J. Lian. 2002b. “Job Stress and Job Dissatisfaction of Home Care Workers in the Context of Health Care Restructuring.” International Journal of Health Services, 32 (2), 327–357.

- Denton, M., I. Zeytinoglu and S. Davies. 2003. Organizational Change and the Health and Well-Being of Home Care Workers. SEDAP Working Paper #110, <http://socserv2.socsci.mcmaster.ca/sedap>.

- Ducharme, L., and J. Martin. 2000. “Unrewarding Work, Coworker Support, and Job Satisfaction: A Test of the Buffering Hypothesis.” Work and Occupations, 27 (2), 223–243.

- Dunlop, J. T. 1958. Industrial Relations Systems. Revised edition of the 1958 publication in 1993. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 1–41.

- Green, F. 2004. “Why has Work Effort become More Intense?” Industrial Relations, 43 (4), 709–741.

- Green, F., and N. Tsitsianis. 2005. “An Investigation of National Trends in Job Satisfaction in Britain and Germany.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43 (3), 401–429.

- Hamermesh, D. S. 1977. “Economic Aspects of Job Satisfaction.” Essays in Labor Market Analysis. O. Ashenfelter and W. Oates, eds. New York: John Wiley, 53–72.

- Hasselhorn, H. M., P. Tackenberg, A. Buescher, M. Simon, A. Kuemmerling and B. H. Mueller. 2005. Work and Health of Nurses in Europe, Results of the NEXT-Study. <http://www.next-study.net> (downloaded on March 15, 2006).

- Hayes, L. J., L. O’Brien-Pallas, C. Duffield, J. Shamian, J. Buchan, F. Hughes, H. K. Spence Laschinger, N. North and P. Stone. 2006. “Nurse Turnover: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43, 237–263.

- Health Council of Canada. 2005. Modernizing the Management of Health Human Resources in Canada: Identifying Areas for Accelerated Change. <http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca> (downloaded in April 2006).

- Jex, S. M., and C. D. Crossley. 2005. “Organizational Consequences.” Handbook of Work Stress. J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway and M. R. Frone, eds. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage, 575–600.

- Judge, T. A., and A. Watanabe. 1993. “Another Look at the Job Satisfaction – Life Satisfaction Relationship.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 939–948.

- Kochan, T. A., H. C. Katz and R. B. McKersie. 1986. The Transformation of American Industrial Relations. New York: Basic Books, 3–20.

- Ladipo, D., and F. Wilkinson. 2002. “More Pressure, Less Protection.” Job Insecurity and Work Intensification. B. Burchell, D. Ladipo and F. Wilkinson, eds. London: Routledge, 8–38.

- Lawler III, E. E. 1973. Motivation in Work Organizations. Pacific Grove, Calif.: Brooks/Cole.

- Lawler III, E. E. 2005. “Motivating and Satisfying Excellent Individuals.” Management Skills: A Jossey-Bass Reader. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass, 423–449.

- Lazarus, R. S. 1990. “Theory-Based Stress Measurement.” Psychological Inquiry, 1, 3–13.

- Meltz, N. 1993. “Industrial Relations Systems as a Framework for Organizing Contributions to Industrial Relations Theory.” Industrial Relations Theory: Its Nature, Scope and Pedagogy. R. Adams and N. Meltz, eds. Metuchen, N.J.: The Scarecrow Press, 161–182.

- Merllié, D., and P. Paoli. 2001. Third European Survey on Working Conditions, 2000. European Foundation Survey. Luxembourg: Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities. O’Brien-Pallas, L., D. Thomson, L. M. Hall, G. Pink, M. Kerr, S. Wang, X Li and R. Meyer. 2004. Evidence-based Standards for Measuring Nurse Staffing and Performance. Ottawa: CHSRF, <http://www.chsrf.ca/final_research> (downloaded on November 24, 2005).

- RNAO (Registered Nurses Association of Ontario). 2003. Survey ofPart-Time and Casual Registered Nurses in Ontario, 2003. <http://www.rnao.org/html/PDF/ RNAO_part_time_casual_report.pdf>, (downloaded on May 20, 2003).

- Robbins, S. P., and N. Langton. 2003. Organizational Behaviour: Concepts, Controversies, Applications. Toronto: Pearson-Prentice Hall.

- Romanow Commission (prepared by Canadian Health Service Research Foundation). 2002a. Discussion Paper: Homecare in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

- Romanow Commission (prepared by Canadian Health Service Research Foundation). 2002b. Issue/Survey Paper: Health Human Resources in Canada’s Health Care System. Ottawa, Ontario: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

- Rose, M. 2005. “Job Satisfaction in Britain: Coping with Complexity.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43 (3), 455–467.

- Scott, J. 2006. “Nursing Workload Measurement: Treasure or Terror?” Presented at Dr. Linda O’Brien-Pallas, CHSRF/CIHR National Chair in Nursing/Health Human Resources Research Symposium. Toronto, April 25.

- Spector, P. E. 1997. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Cause and Consequences. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Spector, P. E., D. Zapf, P. Y. Chen and M. Frese. 2000. “Why Negative Affectivity Should not be Controlled in Job Stress Research: Don’t Throw the Baby Out with the Bath Water.” Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 21, 79–95.

- Tepper, J., and S. Larente. 2004. 2Health Human Resources: A Key Policy Challenge.” Health Policy Research Bulletin (Health Canada), 8 (5), 3–7.

- WES Compendium. 2001. Workplace and Employee Survey. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 71–585–XIE. Revised, October, 2004.

- Wetzel, K. 2005a. “Comparative Analysis and Conclusions.” Labour Relations and Health Reform. K. Wetzel with contributions from S. Bach, M. Bray and N. White, eds. Hampshire, G.B.: Palgrave Macmillan, 198–222.

- Wetzel, K. 2005b. “The Canadian Context.” Labour Relations and Health Reform. K. Wetzel with contributions from S. Bach, M. Bray and N. White, eds. Hampshire, G.B.: Palgrave Macmillan, 86–90.

- Wichert, I. 2002. “Job Insecurity and Work Intensification: The Effects on Health and Well-Being.” Job Insecurity and Work Intensification. B. Burchell, D. Ladipo and F. Wilkinson, eds. London: Routledge, 154–171.

- Wilkins, K., and M. Beaudet. 1998. “Work Stress and Health.” Health Reports, 10 (3), 47–62.

- Williams, C. 2003. “Sources of Workplace Stress.” Perspectives on Labour and Income. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75–001–XIE, 4 (6), 5–12.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., M. Denton, S. Davies, A. Baumann, J. Blythe and L. Boos. 2006. “Retaining Nurses in their Employing Hospitals and in the Profession: Effects of Job Preference, Unpaid Overtime, Importance of Earnings and Stress.” Health Policy, 79, 57–62.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

The Conceptual Model of Associations between Work Intensification, Stress and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Ontario

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics, Scale Reliabilities and Range of All Variables (Means, standard deviations or proportions, scale reliabilities and ranges) N = 949

Variables |

% |

Mean (S.D.) |

Scale Reliability (α) |

Scale Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dependent Variables |

|

|

|

|

Satisfaction with financial rewards |

|

33.7 (6.5) |

.81 |

12-60 |

Satisfaction with work and work environment |

|

76.6 (11.1) |

.86 |

24-120 |

Mediating Variable |

|

|

|

|

Stress (symptoms of stress) scale |

|

32.5 (7.9) |

.87 |

14-70 |

Item percentages: |

|

|

|

|

I feel exhausted at the end of the day |

48 |

|

|

|

I am not feeling energized on the job |

31 |

|

|

|

I am not able to sleep through the night |

22 |

|

|

|

I feel burnt out most or all of the time |

15 |

|

|

|

There is nothing more to give |

12 |

|

|

|

I have little or no control over my life |

10 |

|

|

|

Others: |

8 to 1 |

|

|

|

I feel irritable and tense, suffering from headaches or migraines, feeling helpless, feeling like yelling at people, feeling angry, like crying, having difficulty concentrating, feeling dizzy |

|

|

|

|

Independent Variable |

|

|

|

|

Work intensification scale |

|

24.2 (3.9) |

.80 |

6-30 |

Item percentages: Compared to early 1990s, |

|

|

|

|

My work intensity is higher |

91 |

|

|

|

My workload is heavier |

84 |

|

|

|

Nurses are assigned more patients per shift |

71 |

|

|

|

The amount of unpaid work I do increased |

53 |

|

|

|

There are fewer nurse leaders |

73 |

|

|

|

Patient complexity has increased |

94 |

|

|

|

Control variables |

|

|

|

|

Workload |

|

20.5 (4.5) |

.85 |

6-30 |

Paid overtime |

27 |

|

|

|

Unpaid overtime |

22 |

|

|

|

Job insecurity |

|

15.6 (5.1) |

.89 |

7-35 |

Prefer different status |

21 |

|

|

|

Support at work: |

|

|

|

|

Organizational |

|

16.2 (3.8) |

.73 |

6-30 |

Supervisor |

|

19.0 (5.5) |

.94 |

6-30 |

Peer |

|

15.5 (2.5) |

.82 |

4-20 |

Education |

|

|

|

|

University degree or higher |

19 |

|

|

|

Lower than university degree |

81 |

|

|

|

Position |

|

|

|

|

RN |

91 |

|

|

|

RPN |

9 |

|

|

|

Tenure in the position (in months) |

|

122.9 (94.5) |

N/A |

|

Tenure at the hospital (in months) |

|

203.1 (101.3) |

N/A |

|

Gender (Female) |

97 |

|

|

|

Age |

|

45 (8.2) |

N/A |

|

Marital status: |

|

|

|

|

Married/Common Law |

75 |

|

|

|

Widowed |

2 |

|

|

|

Divorced/Separated |

10 |

|

|

|

Never Married |

12 |

|

|

|

Other |

1 |

|

|

|

Child(ren) under 12 |

41 |

|

|

|

The importance of income to family’s economic well-being |

|

4.43 (.83) |

|

Item range: 1-5 |

Table 2

Correlations between Dependent, Independent and Mediating Variables (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients)

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Satisfaction with financial rewards |

--- |

|

|

|

2. Satisfaction with work and work environment |

.490** |

--- |

|

|

3. Work intensification |

‑.282** |

‑.343** |

--- |

|

4. Stress |

‑.323** |

‑.502** |

.298** |

--- |

* p < .05 ** p < .01

Table 3

Factors Associated with Nurses’ Stress and Satisfaction with Financial Rewards

|

Stress |

Satisfaction with Financial Rewards |

Final Model of Satisfaction with Financial Rewards |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(Column 2) |

(Column 3) |

(Column 4) |

|

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

Constant |

23.127 (4.419) |

34.130 (3.449) |

36.302 (3.493) |

|

|

|

|

Work intensification |

.167 (.078)* |

‑.164 (.061)** |

‑.149 (.061)* |

Stress |

----- |

----- |

‑.094 (.029)** |

|

|

|

|

Workload |

.507 (.070)*** |

‑.195 (.054)*** |

‑.147 (.056)** |

Paid overtime |

‑.697 (.578) |

.075 (.451) |

.009 (.449) |

Unpaid overtime |

.476 (.656) |

.459 (.512) |

.503 (.509) |

Job insecurity |

.179 (.058)** |

‑.086 (.045) |

‑.069 (.045) |

Prefer different status |

1.850 (.625)** |

‑.802 (.488) |

‑.628 (.487) |

Organizational support |

‑.402 (.090)*** |

.445 (.070)*** |

.407 (.071)*** |

Supervisory support |

‑.064 (.056) |

.148 (.044)** |

.142 (.044)** |

Peer support |

‑.189 (.107) |

‑.073 (.084) |

‑.091 (.083) |

Education |

‑.129 (.679) |

.536 (.530) |

.524 (.527) |

Position (RPN=1, RN=0) |

‑1.274 (1.003) |

‑3.966 (.783)*** |

‑4.085 (.779)*** |

Tenure at the hospital |

.006 (.004) |

.001 (.003) |

.001 (.003) |

Tenure in current position |

‑.001 (.003) |

‑.005 (.003)* |

‑.005 (.003)* |

Gender |

1.842 (1.429) |

1.335 (1.115) |

1.507 (1.109) |

Age |

‑.090 (.046)* |

.030 (.036) |

.021 (.036) |

Marital status: |

|

|

|

Married/C.Law (Ref) |

----- |

----- |

----- |

Widowed |

.219 (2.148) |

1.030 (1.676) |

1.050 (1.665) |

Divorced/Separated |

‑.216 (.949) |

.784 (.741) |

.764 (.736) |

Never married |

‑.948 (1.307) |

‑1.876 (1.020) |

‑1.786 (1.014) |

Other |

1.227 (3.133) |

‑.445 (2.445) |

‑.330 (2.429) |

Child(ren) under 12 |

.290 (.637) |

‑.211 (.497) |

‑.184 (.494) |

Importance of income to family’s economic well-being |

.892 (.314)** |

‑.386 (.245) |

‑.302 (.245) |

|

|

|

|

Adjusted R2 |

.267 |

.280 |

.290 |

*p < .05 ** p < .01 ***p < .001

Table 4

Factors Associated with Nurses’ Stress and Satisfaction with Work and Work Environment

|

Stress |

Satisfaction with Work and Work Environment |

Final Model of Satisfaction with Work and Work Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(Column 2) |

(Column 3) |

(Column 4) |

|

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

B (S.E.) |

Constant |

23.127 (4.419) |

59.730 (4.134) |

64.798 (4.099) |

|

|

|

|

Work Intensification |

.167 (.078)* |

‑.172 (.073)* |

‑.135 (.071) |

Stress |

---- |

----- |

‑.219 (.034)*** |

|

|

|

|

Workload |

.507 (.070)*** |

‑.706 (.065)*** |

‑.595 (.066)*** |

Paid overtime |

‑.697 (.578) |

‑.616 (.541) |

‑.769 (.527) |

Unpaid overtime |

.476 (.656) |

.019 (.614) |

.123 (.597) |

Job insecurity |

.179 (.058)** |

‑.109 (.054)* |

‑.070 (.053) |

Prefer different status |

1.850 (.625)** |

‑.905 (.584) |

‑.500 (.572) |

Organizational support |

‑.402 (.090)*** |

.734 (.084)*** |

.646 (.083)*** |

Supervisory support |

‑.064 (.056) |

.718 (.053)*** |

.704 (.051)*** |

Peer support |

‑.189 (.107) |

.802 (.100)*** |

.760 (.098)*** |

Education |

‑.129 (.679) |

.117 (.635) |

.089 (.618) |

Position (RPN=1, RN=0) |

‑1.274 (1.003) |

.263 (.938) |

‑.017 (.914) |

Tenure at the hospital |

.006 (.004) |

.001 (.003) |

.003 (.003) |

Tenure in current position |

‑.001 (.003) |

‑.006 (.003)* |

‑.006 (.003)* |

Gender |

1.842 (1.429) |

‑.880 (1.337) |

‑.477 (1.302) |

Age |

‑.090 (.046)* |

.038 (.043) |

.018 (.042) |

Marital status: |

|

|

|

Married/C.Law (Ref) |

----- |

----- |

----- |

Widowed |

.219 (2.148) |

‑1.274 (2.009) |

‑1.226 (1.955) |

Divorced/Separated |

‑.216 (.949) |

‑.052 (.888) |

‑.099 (.864) |

Never married |

‑.948 (1.307) |

‑1.972 (1.223) |

‑1.764 (1.190 |

Other |

1.227 (3.133) |

1.729 (2.930) |

1.998 (2.851) |

Child(ren) under 12 |

.290 (.637) |

‑.966 (.596) |

‑.902 (.580) |

Importance of income to family’s economic well-being |

.892 (.314)** |

‑.095 (.294) |

.101 (.288) |

|

|

|

|

Adjusted R2 |

.267 |

.657 |

.675 |

*p < .05 ** p < .01 ***p < .001

10.7202/012156ar

10.7202/012156ar