Résumés

Abstract

How should a sham be treated for tax purposes? In 1524994 Ontario Ltd. v. M.N.R., the Federal Court of Appeal treated a sham as if it reflected the true agreement between the parties in order to uphold a GST assessment. The result was inconsistent with existing jurisprudence and undesirable. Courts should apply the law to the true facts only, and should not overlook or give effect to a sham in order to achieve the desired juridical consequences.

The author reviews the origins and development of the sham doctrine and introduces a three-part typology of sham cases. In situations like 1524994 Ontario Ltd. v. M.N.R., the sham is intended to obtain non-tax benefits from a third-party victim, but in the process triggers unintended tax consequences, which are the subject of litigation. Although the traditional approach in Continental Bank Leasing Corp. v. M.N.R. (under which recharacterization is permissible only if the label attached to a transaction does not reflect its actual legal effect) could result in non-payment of taxes and retention of improperly obtained benefits, the author concludes that this result would be preferable to that of the Federal Court of Appeal judgment. Treating a sham as real, and taxing a wrong as a right (1) will not deter parties from creating shams to obtain non-tax benefits, (2) will violate longstanding principles that tax law be applied with neutrality and equity and without considering its effects, and (3) will increase uncertainty and inconsistency in the case law.

Résumé

Comment une opération fictive devrait-elle être traitée aux fins de l’impôt ? Dans 1524994 Ontario Ltd. c. M.R.N., la Cour d’appel fédérale a traité une opération fictive comme reflétant le vrai accord entre les parties de manière à leur imposer une cotisation à la TPS. Le résultat n’était pas conforme à la jurisprudence actuelle et était indésirable. Les cours devraient appliquer le droit aux faits réels et ne devraient pas ignorer ou prendre en considération une opération fictive afin d’imposer les conséquences juridiques désirées.

L’auteur passe en revue les origines et le développement de la doctrine sur les opérations fictives et introduit une typologie en trois parties des affaires traitant de l’opération fictive. Dans des cas comme 1524994 Ontario Ltd. c. M.R.N., l’opération fictive visait à obtenir un avantage non fiscal d’une tierce partie victime, mais l’opération fictive attira des litiges fiscaux non désirés. L’approche traditionnelle dans Continental Bank Leasing Corp. c. M.R.N., selon laquelle la redéfinition est permise uniquement lorsque le nom attaché à la transaction ne reflète pas ses effets juridiques réels, pourrait résulter en le non-paiement d’impôts et en la rétention de profits obtenus indûment. L’auteur conclut néanmoins que ce résultat serait préférable à celui du jugement de la Cour d’appel fédérale. Le fait de traiter l’opération fictive comme étant réelle et de percevoir des impôts comme si la transaction était légitime (1) ne dissuadera pas les parties à s’engager dans des opérations fictives afin d’obtenir des avantages non fiscaux, (2) violera les principes bien établis voulant que le droit fiscal s’applique de façon neutre, équitable et sans égard à ses effets, et (3) créera plus d’incertitude et d’incohérence dans la jurisprudence.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

How should the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and the courts properly treat a sham[1] for tax purposes? Should they treat it as though it reflects the actual transaction or relationship between the parties, or should they first acknowledge it as a sham and then ignore it in favour of the true facts, once ascertained? Should the proper approach be influenced by whether the sham was intended to obtain a tax or a non-tax benefit?[2] Finally, how does the proper approach in tax cases correspond to the courts’ general treatment of shams where there are no tax implications or at least none being litigated?

In the recent case of 1524994 Ontario Ltd. v. M.N.R.,[3] the Federal Court of Appeal had the opportunity to address these questions in deciding the appropriate goods and services tax[4] (GST) result in respect of a fraudulent agreement designed to obtain funds from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan[5] (OHIP). In my respectful opinion, the Federal Court of Appeal’s decision to tax the sham as opposed to the real underlying situation, while understandable in the circumstances, was both undesirable and inconsistent with existing jurisprudence. Simply put, given the Tax Court of Canada’s factual findings, the wrong should not have been taxed as a right.

This paper has two purposes. The primary purpose is to argue that regardless of the outcome, courts should apply the law only to the true facts in a case. That is, a court should not overlook the possibility of a sham or, even worse, give it legal effect in order to achieve a result that it feels is appropriate in the circumstances, as the Federal Court of Appeal did in 1524994 Ontario Ltd. The second purpose is to use this decision as a warning to parties and their professional advisors of the dangers of inaccurately documenting their transactions and relationships. Specifically, a court may hold parties and apply the relevant law to what they have documented the facts to be, rather than to what the facts actually are.

I. The Sham Doctrine in Canada

A. The Origins and Use of the Sham Doctrine

At least since the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in M.N.R. v. Cameron,[6] Canadian courts have relied on Lord Diplock’s definition of a sham in his decision in Snook v. London and West Riding Investments Ltd.:

[I]t means acts done or documents executed by the parties to the “sham” which are intended by them to give to third parties or to the court the appearance of creating between the parties legal rights and obligations different from the actual legal rights and obligations (if any) which the parties intend to create. ... [F]or acts or documents to be a “sham,” with whatever legal consequences follow from this, all the parties thereto must have a common intention that the acts or documents are not to create the legal rights and obligations which they give the appearance of creating.[7]

Three important points can be derived from this definition. First, a sham is intentional. The parties to the sham must jointly intend to create the appearance of legal rights or a relationship that differs from the actual rights or relationship.[8] Second, the essence of a sham is the attempted deception of a third party.[9] While this deception is typically designed to obtain a benefit that would not otherwise be available to the parties, shams have also been used to avoid a detriment that would otherwise result.[10] Third, while many cases that have applied the sham doctrine have been tax cases, the sham doctrine is not tax-specific.[11] Indeed, Snook was a non-tax case that concerned whether the seizure of a financed vehicle was appropriate in the circumstances. In Canada, the sham doctrine has been applied in practically all areas of the law including: corporate law,[12] pension plans,[13] receivership and bankruptcy law,[14] health law,[15] constitutional law,[16] employment insurance,[17] contract law,[18] and employment law.[19]

B. The Proper Application of the Sham Doctrine: The Continental Bank Approach

In Continental Bank Leasing Corp. v. M.N.R.,[20] Justice Bastarache quoted the following passage from the English Court of Appeal judgment in Orion Finance Ltd. v. Crown Financial Management Ltd. as being the proper approach for identifying and handling a possible sham:

The first task is to determine whether the documents are a sham intended to mask the true agreement between the parties. If so, the court must disregard the deceptive language by which the parties have attempted to conceal the true nature of the transaction into which they have entered and must attempt by extrinsic evidence to discover what the real transaction was. ...

Once the documents are accepted as genuinely representing the transaction into which the parties have entered, its proper legal categorisation is a matter of construction of the documents. This does not mean that the terms which the parties have adopted are necessarily determinative. The substance of the parties’ agreement must be found in the language they have used but the categorisation of a document is determined by the legal effect which it is intended to have, and if when properly construed the effect of the document as a whole is inconsistent with the terminology which the parties have used, then their ill-chosen language must yield to the substance.[21]

This approach was subsequently summarized by Justice McLachlin (as she then was), writing for the Supreme Court of Canada in Shell Canada Ltd. v. Canada:

This Court has repeatedly held that courts must be sensitive to the economic realities of a particular transaction, rather than being bound to what first appears to be its legal form. But there are at least two caveats to this rule. First, this Court has never held that the economic realities of a situation can be used to recharacterize a taxpayer’s bona fide legal relationships. To the contrary, we have held that, absent a specific provision of the Act to the contrary or a finding that they are a sham, the taxpayer’s legal relationships must be respected in tax cases. Recharacterization is only permissible if the label attached by the taxpayer to the particular transaction does not properly reflect its actual legal effect.[22]

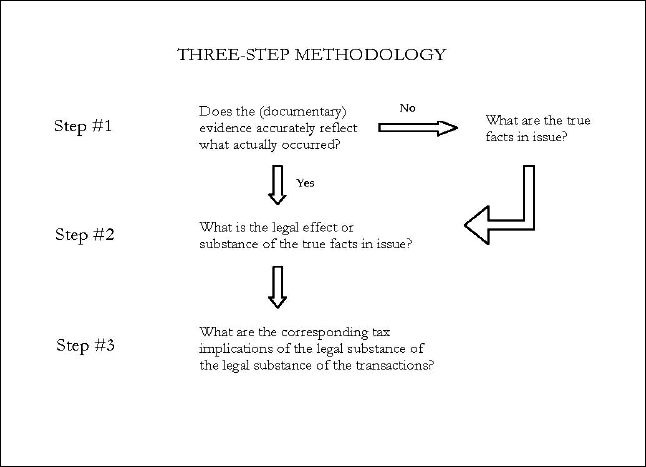

In short, the proper approach for identifying and, if necessary, dealing with a sham consists of two steps generally and three steps in tax cases. First, a court must consider whether the presented documentary evidence accurately reflects the true agreement or relationship between the parties. If it does, then the court can proceed to the second step of determining the legal effect of such evidence. This legal effect may or may not correspond to the description contained in the documents themselves.[23] However, if it is discovered that the documentary evidence does not reflect the

real facts, then the court must ignore such evidence and attempt to ascertain the true facts in issue.[24] It is only after a court has the requisite knowledge of the facts (or has made its best efforts to discover them) that it should proceed to the second step of determining their legal effect. In tax cases, the third step is to apply the relevant tax law to the legal substance previously determined.[25]

While the approach set out in Orion (and the Supreme Court of Canada’s adoption of it) is relatively recent,[26] it has long been a part of Canadian tax jurisprudence and its associated literature.[27] For example, in the Court’s 1933 decision in Palmolive Manufacturing Co. (Ontario) v. Canada, Justice Cannon ruled on behalf of the Court that “the character and substance of the real transaction must, for taxation purposes, be ascertained and the tax levied on that basis.”[28] Similarly, in M.N.R. v. Shields, Justice Cameron held, “I think it is settled law ... that for income tax purposes it is insufficient to establish a partnership in fact merely by the production of a partnership deed. It must also be shown that the parties thereto acted on it and that it governed their transactions in the business being carried on.”[29]

C. The Classification of Sham Cases

While every sham, by definition, is a joint and intentional deception designed to obtain a benefit (or avoid a detriment) from a third party, it is a mistake to think that all sham cases are essentially the same. By paying particular attention to the intended victim of the sham, the benefit sought by the sham, and whether the case is a tax or non-tax case, I believe that it is possible to distinguish between three different types of sham cases. This typology will reveal a shortcoming of the Continental Bank approach and will help explain the Federal Court of Appeal’s deviation from this approach in 1524994 Ontario Ltd.

The first type of sham case (Type I) is one in which the third-party victim is the Minister of National Revenue (Minister), the benefit sought is a tax benefit, and the case is a tax case. Perhaps the most famous example of a Type I sham case is Stubart Investments Ltd. v. M.N.R.[30] In Stubart, two sister corporations, one profitable and the other with significant losses, attempted to restructure business operations between them to transfer the profitable business to the loss corporation in order to reduce the corporations’ overall tax liability.[31] The problem that the Minister had with this restructuring was that, while certain documents were indeed executed to reflect the transfer of assets from the profitable corporation to the loss corporation, there was little else that reflected the change in who was carrying on the profitable business.[32] For example, the employees of the profitable corporation continued to carry on the profitable business, though now as agents for the loss corporation, pursuant to the transfer documents. Accordingly, the Minister reassessed both corporations and taxed the profits as being earned by the profitable rather than the loss corporation. In the Minister’s opinion, the documentary evidence was a sham—an attempt by both corporations (as well as the parent corporation) to deceive the Minister into believing that the loss corporation was now carrying on the profitable corporation’s business when in reality it was not.

At trial, in addition to examining the transfer documents, Justice Flanigan considered other evidence that was brought to his attention by the Minister and the corporations’ lawyer.[33] Based on the totality of this evidence, he concluded that the agreement was a sham: the documentation was designed to utilize the losses in the loss corporation for tax purposes without ever truly transferring the profitable business to the loss corporation.[34] As a result, he ignored the transfer documentation, treated the profits as belonging to the profitable corporation, and upheld the Minister’s reassessment. While this result was confirmed by the Federal Court, Trial Division[35] and the Federal Court of Appeal,[36] it was ultimately overturned by the Supreme Court of Canada.[37]

The second type of sham case (Type II) is one in which the third-party victim is someone other than the Minister, the benefit sought is a non-tax benefit, and the case does not involve a question of taxation. One example of a Type II sham case that is somewhat similar to 1524994 Ontario Ltd. is SHS Optical No. 2.[38] This case arose as a result of an earlier case in which the College of Optometrists of Ontario (College) had taken SHS Optical Ltd., Bruce Bergez,[39] and several others to court to obtain an order that they comply with the applicable health care legislation in Ontario.[40] This legislation required that the diagnosis, prescription and dispensing of glasses be executed with the involvement of a physician or an optometrist.[41] In SHS Optical No. 1, the College successfully convinced the court that SHS Optical Ltd.’s employees (who were neither physicians nor optometrists) were writing their own prescriptions and dispensing glasses, both in contravention of the legislation. As a result, the court ordered Bergez, SHS Optical Ltd., and its employees to discontinue these activities immediately and comply with the legislative requirements.[42]

In response to this court order, Bergez created an elaborate corporate structure and executed various agreements that, in his opinion, brought SHS Optical Ltd., its employees, and its franchisees in compliance with the legislation and the court order. After three years of investigations, the College took SHS Optical Ltd. and Bergez back to court to apply for an order of contempt in respect of the court order given in SHS Optical No. 1.[43] To support this application, the College argued and led evidence that the elaborate structure and agreements were shams and that, in reality, SHS Optical Ltd. and its employees continued to operate in contravention of health care legislation by prescribing and dispensing corrective eyewear without the involvement of a physician or optometrist. After considering all of the evidence, Justice Crane of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice held in favour of the College.[44] He ignored the shams, found the defendants to be in contravention of the applicable legislation and the previously issued court order, and fined them one million dollars to disgorge the profits that they obtained from their illegal activities.[45]

In both of these cases, and indeed in all of the Type I and Type II sham cases that I have reviewed, the courts applied the Continental Bank approach without issue. That is, the courts were open to the possibility that the documents did not accurately represent the true facts in issue and allowed further evidence to confirm or deny their validity. Then, based on the totality of the evidence, they determined whether the documents accurately represented the transactions or relationship. When they did not, the courts ignored the documents creating the sham and applied the relevant law to the true facts in issue.

This finding is not surprising. In Type I and Type II sham cases, following the Continental Bank approach allows a court that discovers a sham to strip away any benefits that the parties received as a result of the sham or to impose the detriment that would have otherwise occurred but for the sham. Put simply, for Type I and Type II sham cases, the result of applying the Continental Bank approach is intuitively satisfying; it takes away from the parties to the sham what they should have never had.[46]

This brings us to the third type of sham case (Type III). Like a Type II sham case, a Type III sham case is one in which the third-party victim is someone other than the Minister and the benefit sought is a non-tax benefit. However, unlike a Type II sham, which does not trigger any tax consequences (or at least none that are litigated), a Type III sham triggers unintended tax consequences that are the subject of the litigation. It is in this type of case that the shortcomings of the Continental Bank approach are revealed. Simply ignoring the sham in favour of the true facts in a Type III sham case could actually help (or at least not hurt) the parties to the sham. Since the case would concern only the tax implications triggered by the sham, disregarding the sham could actually eliminate these unintended tax consequences while having no effect on the non-tax benefits improperly obtained from the sham. In other words, if courts apply the Continental Bank approach to a Type III sham case, the parties to the sham could potentially have their cake (retention of the non-tax benefits improperly obtained from the sham), and eat it too (not pay the associated taxes).[47]

Given this awkward and intuitively unsatisfying result, it becomes readily apparent why a court might want to apply a strategy different from the Continental Bank approach to deal with a Type III sham case. Faced with the real possibility that the victimized third party may never bring the matter to court as a Type II sham case and give it the opportunity to strip the parties to the sham of their undeserved non-tax benefits using the Continental Bank approach, a court might resort to more desperate measures, namely, treating the sham as if it were real. While admittedly not the best solution, a court could at least impose a tax penalty on the parties to a Type III sham.

This alternative approach is what the Federal Court of Appeal appears to have opted for in its recent decision in 1524994 Ontario Ltd. Faced with a Type III sham, the court decided to tax the sham rather than apply the Continental Bank approach, which would have allowed the parties to escape paying GST on their ill-gotten gains.[48] While intuitively this may appear to have been the better approach in the circumstances, for reasons that I will discuss below, I believe that it was not.

II. 1524994 Ontario Ltd. v. M.N.R.

A. The Facts[49]

The taxpayer corporation, 1524994 Ontario Ltd., was incorporated by Brian Field (who also owned all of the outstanding shares) to carry on the business of The Audiology Clinic of Southwestern Ontario (Clinic). The Clinic employed Field as its licensed audiologist and also employed an administrative staff. It leased space and possessed all of the equipment necessary to carry on its business of providing audiology services to individuals living in Ontario. In short, it was a self-sufficient business.

The Clinic and Field faced a major difficulty: in order for the Clinic’s audiology services to be covered by OHIP,[50] the services had to be, among other things, both prescribed and performed by or under the supervision of a medical doctor.[51] While most of the Clinic’s clients appeared to have been referred by doctors, the services were provided by Field (who was not a medical doctor) through the Clinic. As a result, the Clinic’s business presumably suffered because its clients would have to pay for the audiological services out of their own pockets.

In an effort to get its services covered by OHIP, Field, the Clinic, and two family doctors who carried on their separate medical practices across the hall from the Clinic, entered into an agreement in 1989. This agreement was executed approximately two years before the GST came into force.[52] The important terms of the agreement were as follows: the doctors would lease the premises and equipment from the Clinic and also employ Field and the Clinic’s administrative staff to provide audiological services to the Clinic’s clients. The Clinic would otherwise continue to operate the business, and as part of its operation, would prepare the claims for submission to OHIP. The doctors would submit these claims to OHIP (which were over ten thousand dollars per month) using their billing numbers. In return for this service, the doctors would retain ten per cent of the amounts received from OHIP, up to a maximum of one thousand dollars per month each, which was reached each month of the period under appeal. The remaining ninety per cent would be paid by the doctors to the Clinic in respect of: lease costs, employment costs, and management fees. In their respective accounting records, the parties reported these payments in accordance with the agreement; for tax purposes, the doctors issued a T4 employment slip to Mr. Field.[53] However, at no time was GST ever charged or collected by either party in respect of the transferred amounts.

While excluding details, Justice McArthur noted in his judgment that the parties had discussed this agreement with officers from OHIP prior to executing it.[54] Presumably, the OHIP officers were satisfied that if the terms of the agreement were followed by the parties, then the Clinic’s services would be eligible for OHIP coverage.[55]

More than ten years after the agreement was implemented, the CRA provided an assessment of the Clinic for outstanding GST (GST Assessment) in respect of the lease and management fees paid from the doctors to the Clinic for the period from 1 August 1997 to 30 April 2000.[56] The GST Assessment appears to have been based solely on the agreement and supporting records (i.e., the accounting and tax entries) that were examined by the GST auditor.

The Clinic and the doctors objected to the GST Assessment on the basis that nothing they did attracted GST. More specifically, they argued that the true transactions in issue were payments from OHIP (via the doctors) to the Clinic for GST-exempt audiological services,[57] and payments from OHIP to the doctors for participation in the Clinic’s activities.[58] In their notice of objection and in court, both Field and the doctors led evidence that their agreement had been prepared only for the purpose of obtaining OHIP coverage, and that it should otherwise be ignored. According to the parties, the agreement did not reflect (nor was it intended to reflect) the true nature of the relationship between the Clinic, the doctors, and Field, or any of the transactions between them. While they did not call their agreement a sham, the parties asked the court to treat it as one by requesting that they be taxed (or, more accurately, not taxed) on what they testified they did, as opposed to what the agreement and accounting records showed they did.

B. The Tax Court of Canada’s Findings and Decision

Based on a review of the relevant jurisprudence, including the Supreme Court of Canada’s dicta in Shell Canada set out in Part I.B above, Justice McArthur stated that his role was to ascertain the true legal relationship of the parties and give it effect.[59] In this regard, he allowed the oral testimony of Field, whom he described as an “impressive witness”, and considered the correspondence between the CRA and one of the doctors who was party to the agreement.[60] Justice McArthur found this testimony and correspondence (as opposed to other prior documentation including the agreement) to be accurate, reliable, and representative of the true facts. He went on to state that while the parties’ arrangement was “not praiseworthy”,[61] the appellant company was “rendering valuable services to patients and Dr. Rooney’s intentions were laudable in that he believed there was a need in the community for the Appellant’s services.”[62] Based on this evidence and his generally positive view of the parties’ intentions, Justice McArthur found that “the agreement did not reflect the dominant or overall relationship of the parties” and that the parties did not create legally binding lease and employment contracts.[63] Instead, he held that the true relationship between the doctors and the Clinic was one of agency, with the doctors being agents of the Clinic; as such, GST was not applicable to the payments received by the Clinic as they were for non-taxable audiological services.[64]

Despite the facts of the case and the parties’ testimony, Justice McArthur concluded that the agreement was not a sham for two reasons. First, he seemed uncomfortable raising the doctrine of shams when neither the parties nor the Minister presented arguments on the point. Second, the documents had been disclosed to OHIP officials prior to the agreement’s execution.[65]

In summary, Justice McArthur, as trier of fact, found the parties to be credible and, based on their testimony, held that their agreement did not reflect their actions and had to be ignored. He characterized their relationship at law as that of principal and agent to support his decision that GST was not applicable to the payments made between the parties.

C. The Federal Court of Appeal’s Approach and Decision

At the Federal Court of Appeal, Justice Décary, for a unanimous court, made it clear from the outset that the Clinic would not be permitted both to reap the non-tax benefits from deceiving OHIP, and to escape GST (as was the result of Justice McArthur’s decision).[66] Thus, the court overturned both the approach employed by the Tax Court of Canada as well as the ultimate decision that GST was not applicable.

With respect to the Tax Court of Canada’s approach, Justice Décary held that

the Tax Court Judge erred in law in basing his decision on after-the-fact evidence of the parties’ intention to re-characterize an agreement, which was clear, complete, and so effective as between the parties that they had acted upon it to obtain substantial monetary benefits from OHIP.[67]

In his opinion, and without citing any cases or legal principles in support, once the Clinic started receiving payments via the doctors from OHIP, the illusion became real and acquired legal effect. As such, it was no longer open for Justice McArthur to consider the parties’ subsequent, self-serving, oral testimony and written evidence that the agreement did not reflect the true facts in issue. In the Federal Court of Appeal’s opinion, the tax court’s approach caused two significant problems. First, it violated the principle set out by the Supreme Court of Canada in Shell Canada that “the taxpayer’s legal relationships must be respected in tax cases,” and that “[r]echaracterization is only permissible if the label attached by the taxpayer to the particular transaction does not properly reflect its actual legal effect.”[68] Where the agreement had acquired legal effect by the parties receiving payments from OHIP, it was not open for the Tax Court of Canada to recharacterize the agreement for tax purposes. Second, the tax court’s approach would open the floodgates in the future for both taxpayers and the CRA to argue that the documents did not reflect the parties’ true intentions. Quoting from Justice Linden’s judgment in Friedberg v. M.N.R.,[69] Justice Décary reiterated the concern that if such evidence were allowed,

Revenue Canada and the courts would be engaged in endless exercises to determine the true intentions behind certain transactions. Taxpayers and the Crown would seek to restructure dealings after the fact so as to take advantage of the tax law or to make taxpayers pay tax that they might otherwise not have to pay. While evidence of intention may be used by the courts on occasion to clarify dealings, it is rarely determinative. In sum, evidence of subjective intention cannot be used to “correct” documents which clearly point in a particular direction.[70]

In this case, not only did the parties’ agreement reflect the fact that payments were being made by the doctors to the Clinic in respect of rent, salaries and management fees, but so too did the parties’ accounting and tax records. In this situation, where all of the existing documentary evidence was consistent and indicated a particular state of affairs, the Federal Court of Appeal decided that subsequent contradictory testimony should not be considered.[71] Doing otherwise would presumably cause too much uncertainty in the law.

With respect to the Tax Court of Canada’s finding of an agency relationship, the Federal Court of Appeal overturned this conclusion on two grounds. First, the court held that there was no evidence to support an agency relationship.[72] Second, the court held that the doctors could not have been the Clinic’s agents because they possessed a power that the Clinic itself did not have—specifically, the power to submit billings to OHIP. Citing the case of Haggstrom v. Dey,[73] the court restated the rule: “An agent cannot have a legal capacity that exceeds that of the principal. A principal can only appoint an agent to make a contract which the principal himself has the capacity to make.”[74] As the Clinic could not get reimbursed for its services without the assistance and participation of the doctors, the Clinic could not, at law, be the principal, and hence there could not be an agency relationship.

Two final points from the decision are important to note. First, like Justice McArthur, Justice Décary was reluctant to characterize the parties’ agreement as a sham.[75] He too was concerned that the allegation of a sham had not been explicitly raised by either party to the case, and felt it inappropriate to raise on his own. He stated, without providing details how, that labelling the agreement a sham would, at best, only support his ultimate finding that GST should be applied. Second, Justice Décary was concerned that if he allowed the parties to repudiate the contract for tax purposes while still taking its benefit in OHIP fees, this could be interpreted as the court’s endorsement of this type of scheme.[76]

In overturning the Tax Court of Canada’s decision and reinstating GST Assessment against the Clinic, Justice Décary left the parties (and anyone else considering such a scheme) with this final warning:

In the end, I have reached the view that a person who creates a contractual fiction designed intentionally to misrepresent a legal relationship, and who takes advantage of it, cannot later invoke the true economic reality to avoid the tax disadvantages flowing from it. When a fairytale becomes the real world with respect to third parties for one purpose (OHIP), it remains the real world with respect to third parties for other purposes (the Minister). The Supreme Court of Canada has invited us to look at the real economic world when examining a transaction in the context of a tax assessment. Where a taxpayer has created a fiction and has lived by it, his fiction has become its real economic world, for better and for worse, plus GST.[77]

III. The Problems with Taxing a Sham

Was it proper for the Federal Court of Appeal to use an alternative to the Continental Bank approach to deal with the facts in 1524994 Ontario Ltd., a Type III sham case? Strictly speaking, the answer is no: the Supreme Court of Canada did not provide for any exceptions to the application of its approach in either Continental Bank or Shell Canada. That said, both these Supreme Court of Canada decisions were Type I sham cases where applying the Continental Bank approach would have resulted in the parties losing their benefits (assuming the Court had found that the documents indeed constituted a sham).[78] Given this fact, should the Continental Bank approach be limited to Type I and II sham cases, leaving the Federal Court of Appeal’s alternate approach in 1524994 Ontario Ltd. to be used for Type III sham cases?

In my opinion, there are too many problems created and no real benefits realized by this alternate approach to justify its use in dealing with Type III shams. More specifically, the Federal Court of Appeal’s approach (1) will not deter parties from creating shams in order to obtain non-tax benefits, (2) will violate longstanding principles that tax law be applied with neutrality and equity and without considering its effects, and (3) will result in additional uncertainty and inconsistency in the case law. For these reasons, I believe that the Continental Bank approach should continue to be applied to Type III sham cases.[79]

A. The Federal Court of Appeal’s Approach Will Not Discourage Parties from Creating Shams in Order to Obtain Non-Tax Benefits

As previously defined, a Type III sham case involves a sham that is designed to obtain a non-tax benefit but, in the process, triggers unintended tax consequences that are then the subject of litigation. In 1524994 Ontario Ltd., the non-tax benefit was OHIP coverage of audiological services performed without the required direct involvement of a medical practitioner. Given that the primary purpose of a Type III sham is to obtain non-tax benefits, it is highly unlikely that the imposition of taxes on the sham would deter parties from creating such a sham unless such taxes took away all or substantially all of the benefits derived from the sham. In 1524994 Ontario Ltd., the imposition of GST by the Federal Court of Appeal resulted in a seven per cent charge on the funds received from OHIP and paid from the doctors to the Clinic. Viewed the other way, even after the imposition of GST, the parties still retained over ninety per cent of the payments from OHIP (excluding any interest assessed on the outstanding GST balance and any applicable income taxes).[80] Given this fact, it is likely that taxing a Type III sham as if it were real would not deter parties from creating these shams as Justice Décary had hoped. All it would do is reduce the quantum of benefits enjoyed by the parties by allocating a share to the Minister.[81]

B. The Federal Court of Appeal’s Approach Constitutes a Biased, Results- Driven Application of Tax Law

In the interpretation and application of tax law, courts have generally adhered to two basic principles in the absence of a statutory provision to the contrary. First, tax laws are to be interpreted and applied in a neutral and equitable manner without consideration of the possible underlying impropriety of the parties’ behaviour.[82] Second, the interpretation and application of tax law should not be influenced by its results.[83] Both of these principles reflect the courts’ overall view that because tax law is exceedingly complex and full of a variety of legislative objectives, courts should be reluctant to find and apply “an unexpressed legislative intention” as this could inadvertently frustrate any of these objectives.[84]

In taxing a Type III sham as if it reflected the true facts in issue, in the absence of a statutory provision authorizing such an approach, the Federal Court of Appeal in 1524994 Ontario Ltd. violated these general principles of interpretation and application of tax law, and exceeded its judicial authority. If Parliament wishes to tax shams or, phrased in a less controversial manner, to tax the described form of a transaction or relationship as opposed to its actual substance, then it is up to Parliament to enact the appropriate provisions in tax law. Absent such provisions, the courts’ role is simply to apply tax law to the true facts underlying the sham, without consideration of the parties’ arrangement and without regard to its effect. The courts’ role should not extend to manipulating the application of tax law in order to impose a penalty for what is considered inappropriate behaviour. This is neither the purpose of tax law nor the proper role of the courts.

C. The Federal Court of Appeal’s Approach Will Create Additional Uncertainty and Inconsistency in the Law

While there will always be uncertainty in the legal outcome of a particular case,[85] courts will try to minimize this uncertainty by applying the law in a consistent, predictable, and fair manner.[86] Another reason for rejecting the Federal Court of Appeal’s alternate approach is that it will likely increase uncertainty in the law concerning the proper treatment of shams, due to inconsistent application of the alternate approach and inconsistent treatment of the legal effect of shams.

1. Inconsistency in What Behaviour Merits the Application of the Federal Court of Appeal’s Alternate Approach

Why was there such an extreme difference in the two decisions in 1524994 Ontario Ltd.? Based on the same underlying behaviour of the parties, the Tax Court of Canada and the Federal Court of Appeal used two different approaches to facilitate two completely different tax results. In my opinion, the answer is that each court viewed the impropriety of the parties’ behaviour differently.[87] This illustrates one of the problems that will likely result if courts are able to use the Federal Court of Appeal’s alternate approach to dealing with third category shams: the tax consequences to the parties will be based on how the court views the parties’ conduct. Not only will this result in inconsistent decisions as different courts view parties’ behaviour differently, as did the Tax Court of Canada and Federal Court of Appeal in 1524994 Ontario Ltd., but it will also introduce an irrelevant consideration into what should be a neutral application of tax law to the facts in issue.

2. Inconsistency in the Legal Effect of a Sham

Under the Continental Bank approach, a sham, once established, will be disregarded by the court regardless of who alleges it, and the true facts in issue (to the extent they can be ascertained) will be used to decide the case. In this respect, the Continental Bank approach provides for consistency in the law. In all sham cases, once the deception has been established, a court will deny it any legal effect.

In contrast, under the Federal Court of Appeal’s alternate approach to dealing with Type III shams, the treatment of an alleged sham will be inconsistent in its legal effect. Specifically, whether a sham will be given or denied legal effect will depend on who has brought the matter to court and the specific issue being litigated. If the victim of the sham brings the case, then in either a Type I or II sham, the sham will be ignored and all of the benefits obtained taken away. However, if the Minister brings the case, and the Minister is not the intended victim (as in 1524994 Ontario Ltd.), then the sham in a Type III sham case will be given legal effect in order to impose a tax penalty.

Strictly speaking, it might be possible for one court to give a sham legal effect in a tax case and for another court to deny the same sham legal effect in a second case concerning non-tax implications.[88] However, this would create an inconsistency in the law of the kind criticized by Justice McLachlin (as she then was) in her majority decision in Hall v. Hebert,[89] as a threat to the integrity of the legal system. While Hall was a tort case that concerned whether the ex turpi causa doctrine[90] should be applied to deny a plaintiff damages in a personal injury action, the comments by Justice McLachlin summarize another key problem with adopting the Federal Court of Appeal’s alternate approach of taxing Type III shams:

It would put the courts in the position of saying that the same conduct is both legal, in the sense of being capable of rectification by the court, and illegal. It would, in short, introduce an inconsistency in the law. It is particularly important in this context that we bear in mind that the law must aspire to be a unified institution, the parts of which—contract, tort, the criminal law—must be in essential harmony. For the courts to punish conduct with the one hand while rewarding it with the other, would be to “create an intolerable fissure in the law’s conceptually seamless web.” We thus see that the concern, put at its most fundamental, is with the integrity of the legal system.[91]

As further noted by Justice McLachlin[92] and other justices in other cases,[93] though courts have established the principle that they will generally not assist parties whose actions involve illegal behaviour,[94] this principle is not to be applied mindlessly, but only where it protects the integrity of the judicial process.[95] In taxing a Type III sham as if it reflected the true facts in issue, the integrity of the judicial system is harmed more than it is protected.

Conclusion: A Wrong Should Not Be Taxed as a Right

Under the Continental Bank approach, absent a statutory provision to the contrary, a court must consider whether the documents before it represent the true facts in issue. In those few cases where the documents do not, a court must then attempt to determine the true facts before determining their legal and, as appropriate, tax effects. This approach is necessary to preserve consistency and integrity in our legal system. While this may have the unfortunate result of allowing parties to a Type III sham to escape certain tax consequences, this is preferable to taxing the sham, as the Federal Court of Appeal did in 1524994 Ontario Ltd. For the reasons above, a wrong should not be taxed as a right.

That said, this paper should not be interpreted as encouraging parties and their professional advisors to be careless or even fraudulent in recording their transactions and relationships. As aptly stated by Justice Bowman in Molinaro v. M.N.R., “if one makes one’s bed in a particular way one should—particularly if one has had help from professional accountants and lawyers in making the bed—be prepared to lie in it.”[96] It is always open for parties to try to convince the courts (and the CRA) that their documentation does not reflect reality in order to avoid an undesirable legal outcome. However, parties seeking to do so will have to overcome the civil burden of proof by providing “sufficiently clear, convincing and cogent” evidence that satisfies the trier of fact, on a balance of probabilities, that their documentation does not reflect the true facts in issue.[97] In many cases, the parties will be unable to overcome this burden and will have to accept the legal and tax consequences flowing from their documentation.[98] It is important to note, however, that in these cases, a court is not taking the position that it will treat the sham as real despite the finding that the documents do constitute a sham; rather, a court is simply finding that the testimony alleging a sham has not met the burden of proof to be admitted into evidence. In such cases, the documents will necessarily be taken as truly representing the facts since there will be no other admitted evidence to the contrary.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

The definition of a “sham” in Canadian law is provided in Part I, below.

-

[2]

For the purposes of this paper, I am using the definition of a “tax benefit” contained in the Income Tax Act (R.S.C. 1985 (5th Supp.), c. 1): “a reduction, avoidance, or deferral of tax or other amount payable under this Act or an increase in a refund of tax or other amount under this Act” (s. 245(1)).

-

[3]

2007 FCA 74, 278 D.L.R. (4th) 690, [2007] G.S.T.C. 19 [1524994 Ontario Ltd.], rev’g 2006 TCC 87, [2006] G.S.T.C. 20, [2006] G.T.C. 200 [1524994 Ontario Ltd.(T.C.C.)].

-

[4]

Excise Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. E-15, Pt. IX.

-

[5]

OHIP is administered by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and provides health insurance for medically necessary services to Ontario residents. For further information, see Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, “Public Information: OHIP”, online: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care <http://www.health.gov.on.ca/public/programs/ohip>.

-

[6]

(1972), [1974] S.C.R. 1062, 28 D.L.R. (3d) 477 [Cameron]. Even before the Supreme Court of Canada in Cameron (ibid. at 1068) adopted Lord Diplock’s definition of a sham, Canadian courts were already using it in cases. See e.g. Susan Hosiery Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1969] 2 Ex. C.R. 408, [1969] C.T.C. 533 [Susan Hosiery].

-

[7]

Snook v. London and West Riding Investments Ltd., [1967] 2 W.L.R. 1020 at 1030, [1967] 1 All E.R. 518 (C.A.) [emphasis added, Snook].

-

[8]

In cases where one party alone is involved in the façade, courts have typically labelled this as a misrepresentation as opposed to a sham. See e.g. Canada (A.G.) v. N & H Logging Ltd. (1993), 43 M.V.R. (2d) 208 at para. 71, 38 A.C.W.S. (3d) 508 (B.C.S.C.), aff’d [1994] B.C.W.L.D. 2948, (sub nom. Needham v. Hadikin) 52 B.C.A.C. 73.

-

[9]

In the United States, a sham has been held to exist where there has been no intention to deceive but only an intention to obtain a tax benefit and otherwise no commercial or economic purpose. See e.g. Brian A. Felesky & Sandra E. Jack, “Is There Substance to ‘Substance Over Form’ in Canada?” in Report of Proceedings of Forty-Fourth Tax Conference, 1992 Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1993) 50:1 at 50:17. See also Pierre Barasalou, “Review of Judicial Anti-Avoidance Doctrines in Selected Foreign Jurisdictions and Supreme Court of Canada Decisions on Tax Avoidance and Statutory Interpretation” in Report of Proceedings of Forty-Seventh Tax Conference, 1995 Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1996) 11:1 at 11:16-18.

-

[10]

The most common example of this latter scenario is where a person creates the appearance of having no assets in order to prevent these assets from being seized by a creditor in satisfaction of an outstanding debt. This avoidance of a detriment could also be framed as a benefit—namely, the preservation of assets.

-

[11]

The general application of the sham doctrine was acknowledged by Roger Taylor in his summary of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decisions in several cases in the 1990s. “As shams, these agreements or instruments are ineffective for all legal purposes including tax purposes”: Roger Taylor, “The Supreme Court of Canada: Principles of Adjudication of Tax-Avoidance Appeals from Stubart to Shell Canada” in Report of Proceedings of Fifty-First Tax Conference, 1999 Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 2000) 17:1 at 17:6.

-

[12]

See e.g. Trident Foreshore Lands Ltd. v. Brown, 2004 BCSC 1365, 50 B.L.R. (3d) 141, 134 A.C.W.S. (3d) 371 (whether a transfer of voting shares of a non-profit corporation that affected the election of the Board of Directors constituted a sham); Alberta Gas Ethylene v. Canada (1988), 89 D.T.C. 5058, 24 F.T.R. 309 (F.C.T.D.), aff’d (1990), 112 N.R. 399, 90 D.T.C. 6419 (F.C.A.) (whether a Canadian parent corporation had to withhold Canadian taxes on interest paid to a U.S. subsidiary, which was incorporated only for the purpose of obtaining U.S. financing, or whether the U.S. subsidiary was a sham, in which case no withholdings would be required).

-

[13]

See e.g. New Brunswick (Human Rights Commission) v. Potash Corp. of Saskatchewan, 2008 SCC 45, [2008] 2 S.C.R. 604, 295 D.L.R. (4th) 1 (whether a pension plan and its mandatory retirement terms were bona fide or a sham designed to circumvent the Human Rights Act prohibition against age discrimination); Loeb v. Canada, [1978] 2 F.C. 737, [1978] C.T.C. (N.S.) 56 (F.C.T.D.) (whether an agreement signed between a teacher and her federation constituted a sham that allowed her to continue participating in her pension plan while on strike).

-

[14]

See e.g. F.W.C. The Land Co. (Receiver of) v. Bohun (1997), 87 B.C.A.C. 107, 29 B.C.L.R. (3d) 179 (whether an illegal agreement between a real estate salesperson and a licensed real estate agent also constituted a sham and hence precluded the salesperson from making a claim for commissions that were held by the agent, now bankrupt, based on a trust relationship); Re G.M.D. Vending Co. Ltd. (Trustee of) (1994), 45 B.C.A.C. 231, 94 B.C.L.R. (2d) 130 (whether a dividend that was paid from an operating subsidiary corporation to its holding parent company and subsequently loaned back to the subsidiary constituted a sham, or whether such a loan was legitimate and could form the basis of a claim on the now bankrupt subsidiary’s assets).

-

[15]

See e.g. College of Optometrists of Ontario v. SHS Optical Ltd. (2006), 153 A.C.W.S. (3d) 227, 2006 CanLII 39463 (Ont. Sup. Ct.) [SHS Optical No. 2 cited to CanLII], aff’d 2008 ONCA 685, 93 O.R. (3d) 139, 300 D.L.R. (4th) 548 (whether agreements that were set up to satisfy provincial health legislation requiring the involvement of a physician or optometrist in the dispensing of eyewear constituted shams).

-

[16]

See e.g. British Columbia (Milk Marketing Board) v. Bari Cheese Ltd. (1993), 42 A.C.W.S. (3d) 202 (B.C.S.C.), aff’d (1996), 79 B.C.A.C. 34, 26 B.C.L.R. (3d) 279 (whether defendants’ efforts to sell milk products outside the scope of the province’s milk quota system constituted a sham).

-

[17]

See e.g. Martin v. M.N.R., 2000 TCC 98787 (whether four skilled craftsmen who decided to form a corporation were employed by that corporation for employment insurance purposes or whether the arrangement was a sham and they were working together as joint venturers).

-

[18]

See e.g. M.N.R. v. Esskay Farms Ltd. (1975), 76 D.T.C. 6010 (F.C.T.D.) (whether the creation of a corporation and the interim sale of land to that corporation, which was then resold to a municipality—all done for the purpose of allowing the original owner of the land to claim the gain on the sale over a two-year period—was a sham).

-

[19]

See e.g. Semenoff v. Saskatoon Drug & Stationery (1988), 49 D.L.R. (4th) 102, 64 Sask. R. 75 (Q.B.) (whether a joint venture agreement between a former employee and his former employer constituted a sham in a wrongful dismissal case).

-

[20]

[1998] 2 S.C.R. 298, 163 D.L.R. (4th) 385 [Continental Bank cited to S.C.R.].

-

[21]

Orion Finance Ltd. v. Crown Financial Management Ltd., [1996] 2 B.C.L.C. 78 at 84 (C.A.) [Orion], cited in Continental Bank, supra note 20 at para. 21. While Bastarache J. was in the minority, his discussion of the proper approach to dealing with sham cases was affirmed by the majority in that case as well as in subsequent Supreme Court of Canada decisions, including McLachlin J.’s decision for the Court in Shell Canada (infra note 22).

-

[22]

Shell Canada Ltd. v. Canada, [1999] 3 S.C.R. 622 at para. 39, 178 D.L.R. (4th) 26 [emphasis added, references omitted, Shell Canada]. Most recently, this approach was approved by the Federal Court of Appeal: Faraggi v. M.N.R., 2008 FCA 398, [2009] 3 C.T.C. (N.S.) 77, (sub nom. 2529-1915 Québec Inc. v. M.N.R.) 387 N.R. 1 [Faraggi]. After restating the Snook definition of a sham, Noel J.A. stated on behalf of the court, “It follows from the above definitions that the existence of a sham under Canadian law requires an element of deceit which generally manifests itself by a misrepresentation by the parties of the actual transaction taking place between them. When confronted with this situation, courts will consider the real transaction and disregard the one that was represented as being the real one” (ibid. at para. 59 [emphasis added]).

-

[23]

It is important to appreciate the fundamental difference between these two steps. In the first step, the issue is whether the documents are “real” in the sense that they accurately describe the transaction(s) or relationship between the parties. This is not so much a legal issue as an inquiry into whether the court has accurate information with which it can carry out its legal analysis. In contrast, in the second step, the issue is the legal effect of such documents. At this stage of the analysis, while a court may disagree with the parties as to the legal effect of the documents, it does not mean that the documents themselves constitute a fraud or sham. For example, in Wiebe Door Services Ltd. v. M.N.R. ([1986] 3 F.C. 553, 70 N.R. 214 (C.A.)), the issue was not the facts surrounding their relationship, but rather the legal effect of said facts—namely, whether the parties, at law, had an employment or business relationship.

-

[24]

Admittedly, it will not always be an easy and straightforward endeavour. In many cases, it will be the most difficult task for the courts: to find out what really happened or what the true relationship was.

-

[25]

It is only in the third step that the relevant tax law is considered and applied. Prior to this point, all of the analysis generally occurs outside of the taxation realm. Put another way, absent a tax provision to the contrary, tax law will be applied to the legal substance of the transaction or relationship previously determined; tax law will generally not determine the legal effect of the transaction or relationship.

-

[26]

In addition to the Supreme Court of Canada’s approval in Continental Bank (supra note 20), Orion (supra note 21) has also been specifically cited and followed in Canada in the following cases: Pro-Ex Trading v. M.N.R., [2001] G.T.C. 584, [2001] G.S.T.C. 111 (T.C.C.); OSFC Holdings Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1999] 3 C.T.C. (N.S.) 2649, 46 B.L.R. (2d) 195 (T.C.C.).

-

[27]

See e.g. Taylor, supra note 11 at 6-8.

-

[28]

Palmolive Manufacturing (Ontario) v. Canada, [1933] S.C.R. 131 at 139, [1933] 2 D.L.R. 81.

-

[29]

M.N.R. v. Shields, (1962) Ex. C.R. 91, [1962] C.T.C. 548 at 553 (Ex. Ct. Can.). Cameron J. went on to state,

These facts lead me to the conclusion that while there was a partnership agreement, it was never considered by the respondent as binding on him. It was put aside and did not in fact govern the actions of the parties thereto, except to the extent that it was helpful in carrying out his scheme to reduce his own taxable income, namely, by making payments of income tax on account of Victor’s alleged profits.

ibid. at 568In other words, in this case the court found it appropriate to disregard the partnership agreement on the basis that it did not reflect the true relationship and actions between the parties. This approach was approved and adopted by Gibson J. in Susan Hosiery (supra note 6).

-

[30]

[1984] 1 S.C.R. 536, 10 D.L.R. (4th) 1 [Stubart cited to S.C.R.] (typically cited as the leading case concerning the sham doctrine in Canada).

-

[31]

More specifically, the loss corporation attempted to use its accumulated tax losses to reduce (or eliminate) the taxable income generated by the profitable business.

-

[32]

Stubart, supra note 30 at 541-42.

-

[33]

Stubart Investments Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1974] C.T.C. (N.S.) 2284 at 2287, 74 D.T.C. 1209 (T.R.B.). At this time, tax cases were first heard by the Tax Review Board, with the opportunity for a trial de novo at the Federal Court, Trial Division. Appeals from this court were made to the Federal Court of Appeal and, if leave granted, to the Supreme Court of Canada.

-

[34]

Ibid. at 2287-88.

-

[35]

Stubart Investments Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1978] C.T.C. (N.S.) 612, 78 D.T.C. 6414 (F.C.T.D.).

-

[36]

Stubart Investments Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1981] C.T.C. (N.S.) 168, 81 D.T.C. 5120 (F.C.A.). The Federal Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal on the basis that the transfer between the two corporations was incomplete and hence legally ineffective. Given this conclusion, the court did not need to rule on whether the transfer documents constituted a sham.

-

[37]

Stubart, supra note 30. Going through the same process as the lower courts of considering all of the evidence to determine the true facts in issue, the Supreme Court of Canada found that the transfer of the profitable business to the loss corporation was legally effective and complete (ibid. at 552) and accurately represented the transactions between the corporations (ibid. at 580-81). Given these findings, the Court held that the documents did not constitute a sham.

-

[38]

SHS Optical No. 2, supra note 15.

-

[39]

Bergez was the optician who managed three optical stores (operating under the Great Glasses name) that were owned and operated by SHS Optical Ltd. He was also the husband of the sole shareholder of SHS Optical Ltd.

-

[40]

College of Optometrists of Ontario v. SHS Optical Ltd. (2003), 124 A.C.W.S. (3d) 1169, 2003 CanLII 39086 (Ont. Sup. Ct.) [SHS Optical No. 1 cited to CanLII].

-

[41]

Regulated Health Profession Act, S.O. 1991, c. 18, ss. 27, 30; Opticianry Act 1991, S.O. 1991, c. 34, ss. 3, 4, 5(1).

-

[42]

SHS Optical No. 1, supra note 40 at para. 95.

-

[43]

See SHS Optical No. 2, supra note 15.

-

[44]

Ibid. at para. 8.

-

[45]

Ibid. at para. 93.

-

[46]

See also Faraggi, supra note 22. The Federal Court of Appeal, affirming the Tax Court of Canada’s decision, held that the transactions entered into by the parties to create capital gains were shams (ibid. at paras. 67-73). By ignoring these transactions, the court eliminated the benefits sought from them—namely, capital dividends that the third parties could sell for profit to third parties.

-

[47]

Décary J.A. described this situation as allowing “a misrepresenting party to profit twice from its misdeed”: 1524994 Ontario Ltd., supra note 3 at para. 15.

-

[48]

In my opinion, this represents the second time that the Federal Court of Appeal has taken this alternate approach in a Type III sham case, the first time being M.N.R. v. Gurd’s Products Co. Ltd. ([1985] 2 C.T.C. (N.S.) 85, 60 N.R. 184, (F.C.A.) [Gurd’s Products (F.C.A.) cited to C.T.C. (N.S.)]). In this case, the international soft drink conglomerate known as the “Crush Group” wished to establish a franchise in Iraq. The problem was that Iraq would not allow any business activity in its country by U.S. corporations and all of the Crush Group’s international operations were carried out in the United States. To solve this problem, the Crush Group reactivated a Canadian subsidiary corporation, transferred one of its U.S. employees to be the face of the Canadian subsidiary, and flowed all of the correspondence and money associated with the Iraqi franchise operation through the Canadian subsidiary. While this created the appearance that the Iraqi operations were being carried on by a Canadian corporation, in reality it was a sham. All of the decisions and activities were made and carried out by or under the direction of the U.S. corporation. What made this case a Type III sham was that the issue in the case was one of taxation—specifically, were the dividends paid by the Canadian subsidiary to the U.S. corporation subject to Canadian withholding taxes? The Crush Group argued that they were not, since the Canadian subsidiary did nothing in respect of the Iraqi franchise other than create the façade that a non-U.S. corporation was carrying on the business operations. In reality, the payments received by the U.S. corporation were coming from Iraq and not the Canadian corporation. After reviewing all of the evidence, Addy J. of the Federal Court, Trial Division agreed that the involvement of the Canadian subsidiary in the Iraqi operations was a sham and that it did not carry on any business in Canada (which was required to trigger the Canadian withholding taxes): Gurd’s Products Co. Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1981] C.T.C. (N.S.) 195, 81 D.T.C. 5153 (F.C.T.D.). The Federal Court of Appeal disagreed with this decision and reinstated the Canadian withholding taxes as assessed by the Minister. While the basis on which it overturned the decision of the Federal Court, Trial Division is not entirely clear, on behalf of the Federal Court of Appeal, Urie J.A. expressed his serious concerns about allowing the parties who had created the sham to ask the court to disregard it in order to avoid an undesirable tax consequence of the sham (Gurd’s Products (F.C.A.) at 94). In my opinion, while Urie J.A. in Gurd’s Products was not as blatant as Décary J.A. in 1524994 Ontario Ltd. (supra note 3), he did the same thing: he treated the sham as if it were real in order to impose a tax penalty on the parties.

-

[49]

Unless stated otherwise, the facts are taken from the judgment of the Tax Court of Canada. See 1524994 Ontario Ltd. (T.C.C.), supra note 3.

-

[50]

The creation and operation of OHIP is set out primarily in the Health Insurance Act (R.S.O. 1990, c. H.6, ss. 10-29).

-

[51]

Ibid., s. 11.2. Presumably, these requirements were enacted to ensure that (1) the audiology services were in fact medically necessary procedures for the recipient (hence justifying reimbursement by the state), and (2) the services were performed (or supervised) by a competent individual.

-

[52]

Excise Tax Act, supra note 4. This fact makes this a Type III sham case; the parties’ intention was to obtain non-tax benefits from OHIP, but in the process, triggered an unintended GST issue, which was the subject of the litigation.

-

[53]

1524994 Ontario Ltd., supra note 3 at para. 17.

-

[54]

1524994 Ontario Ltd. (T.C.C.), supra note 3 at para. 23.

-

[55]

Nothing in either the Tax Court of Canada decision or the Federal Court of Appeal decision suggests that OHIP ever questioned the agreement or its implementation, or denied coverage for claims made by the doctors.

-

[56]

Excise Tax Act, supra note 4, s. 165(1) (“taxable supply”).

-

[57]

Ibid., Sch. V, Pt. II, s. 7(g) (“audiological services”).

-

[58]

In his Editorial Comment to 1524994 Ontario Ltd. (T.C.C.) (supra note 3), David Sherman raised the question of why the doctors were not assessed GST in respect of the $1,000 payments that they effectively received from the Clinic. He also provided a possible answer, namely, that the CRA might have taken the position that these payments were exempt under “health care service” (Excise Tax Act, supra note 4, Sch. V, Pt. II, s. 5). In any event, the doctors’ share of OHIP payments and the appropriate tax treatment thereof were not at issue in this case.

-

[59]

1524994 Ontario Ltd. (T.C.C.), supra note 3 at paras. 17, 21. In other words, McArthur T.C.J. set out to apply the Continental Bank approach even though he did not cite the case in his judgment.

-

[60]

Ibid. at paras. 6, 19. In response to the GST Assessment, Dr. Rooney’s letter to the CRA dated 8 March 2002, stated that he felt that he did not possess the technical skills necessary to provide the required audiological services.

-

[61]

Ibid. at para. 6.

-

[62]

Ibid. at para. 23.

-

[63]

Ibid. at para. 18.

-

[64]

Ibid. at paras. 23-24.

-

[65]

Ibid. at para. 23.

-

[66]

1524994 Ontario Ltd., supra note 3 at para. 15.

-

[67]

Ibid. at para. 11.

-

[68]

Shell Canada, supra note 22 at para. 39 [reference omitted].

-

[69]

(1991), [1992] 1 C.T.C. (N.S.) 1, 135 N.R. 61 (F.C.A.) [Friedberg cited to C.T.C. (N.S.)], aff’d [1993] 4 S.C.R. 285, 160 N.R. 312.

-

[70]

1524994 Ontario Ltd., supra note 3 at para. 14, citing Friedberg, supra note 69 at 3.

-

[71]

See e.g. Robert M. Beith et al., “Revenue Canada Round Table,” Report of Proceedings of Fortieth Tax Conference, 1988 Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1989) 53:1 at 53:12-13. Revenue Canada (as it then was) stated that its general approach to the characterization of leasing transactions for tax purposes would be simply to follow the form of the parties’ agreement. In other words, if the parties drafted their agreement in the form of a lease, then Revenue Canada would normally assume that the agreement reflected the true (and legal) relationship between the parties and would treat the agreement as a lease for tax purposes. Revenue Canada further stated that while it would always be open to investigate and recharacterize the legal (and tax) effect of the agreement if it felt that the agreement did not represent the true relationship between the parties, it would not be open for taxpayers to do so (i.e., to contradict their own agreement and take the position that the form did not accurately represent the true reality). While certain courts agreed with Revenue Canada’s official position, Thomas Gillespie concluded at the 1992 Corporate Management Tax Conference, based on a review of all of the case law, that the better view was that Revenue Canada’s position was “wrong at law” and that taxpayers could legitimately take the position in court that their agreement did not reflect the true substance of their relationship or transactions. See Thomas Gillespie, “Lease Financing” in Income Tax and Goods and Services Tax Considerations in Corporate Financing, 1992 Corporate Management Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1993) 7:1 at 7:17-20.

-

[72]

1524994 Ontario Ltd., supra note 3 at para. 18.

-

[73]

Haggstrom v. Dey (1965), 54 D.L.R. (2d) 29 (B.C.C.A.).

-

[74]

1524994 Ontario Ltd., supra note 3 at para. 18 [references omitted].

-

[75]

Ibid. at para. 19.

-

[76]

Ibid. at paras. 15-16.

-

[77]

Ibid. at para. 20 [emphasis in original].

-

[78]

Indeed, had England’s Court of Appeal in Orion (supra note 21) found that the documents had constituted a sham (more specifically, a Type II sham), then its approach also would have had the effect of taking away the benefits derived from the sham. Put simply, in all three of these cases, the approach would have worked.

-

[79]

See e.g. United Color and Chemicals Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1992] 1 C.T.C. (N.S.) 2321, 92 D.T.C. 1259 (T.C.C.). In this case, the issue was how to tax properly cash bribes that the corporation made through its owner Mr. Vass, to certain key employees of potential customers in order to ensure the viability of their business (which the litigants stated was the typical practice for that industry). The corporation would make cash payments to Mr. Vass, who would then use the cash to pay off the purchasing agents. As the corporation’s bookkeeper did not believe such amounts could be deducted by the corporation for tax purposes as a business expense, he reported the payments in the corporation’s accounting and tax records as non-deductible dividends to Mr. Vass, who also reported the receipt of cash in his personal tax returns as dividend income. When the Minister denied certain other deductions claimed by the corporation, the corporation, in addition to challenging the Minister’s assessment, also raised the issue of the deductibility of these secret commissions against the corporation’s income and the propriety of the income inclusion to Mr. Vass as dividends. After hearing the oral testimony of various individuals who were involved with the bribes, both internal and external to the corporation, Kempo T.C.J. concluded that such testimony was credible and, as opposed to the existing documentary evidence, reflected what actually occurred, namely, that the corporation had been making cash payments under the table through Mr. Vass to various purchasing agents in order to get their companies’ business. Having knowledge of the true facts in issue, she held that the bribes were misreported as dividends at both the corporate level and in Mr. Vass’s personal income tax return, and that they were properly deductible for tax purposes to the corporation as a business expense with no income inclusion for Mr. Vass. In other words, she disregarded the sham and applied the relevant tax law to the true facts in issue.

-

[80]

As there was nothing in this case concerning compliance with the Income Tax Act (supra note 2), the Clinic was presumably properly reporting and paying income tax in respect of these payments.

-

[81]

Given this fact, it is curious that the Clinic challenged the Minister’s assessment for taxes on its sham benefits. The only possible reason that comes to mind for doing so is that it truly believed that it could have its cake and eat it too. That said, by challenging the Minister’s assessment, in my opinion, the Clinic risked the discovery of its deception by OHIP. If this had occurred and OHIP had brought a case against it, then it appears at least possible that this could have ultimately resulted, as it did in SHS Optical No. 2 (supra note 15), in the Clinic losing all of its benefits from the sham rather than just a small component for GST.

-

[82]

See e.g. 65302 British Columbia Ltd. v. Canada, [1999] 3 S.C.R. 804 at para. 66, 179 D.L.R. (4th) 577. In this case, the issue before the Supreme Court of Canada was whether a corporation that had intentionally violated its quota for egg production could deduct the fine it received from its violation as a business expense for tax purposes. In holding that it could, Iacobucci J. for the majority stated that “tax authorities are not concerned with the legal nature of an activity” (ibid. at para. 56). See also M.N.R. v. Eldridge (1964), [1965] 1 Ex. C.R. 758, [1964] C.T.C. 545 (Ex. Ct. Can.) (the court allowed a taxpayer who had been assessed taxes on the gross revenues of her call-girl operation to deduct the associated expenses she incurred in carrying on that illegal activity). One example of a statutory provision that overrides this general principle is s. 67.6 in the Income Tax Act (supra note 2), which disallows, effective 22 March 2004, the deduction of any fine or penalty imposed under a law of a country by any person or public body that has authority to impose the fine or penalty.

-

[83]

See e.g. M.N.R. v. Antosko, [1994] 2 S.C.R. 312, [1994] 2 C.T.C. (N.S.) 25 [cited to S.C.R.]. Iacobucci J. stated on behalf of the majority that “a normative assessment of the consequences of the application of a given provision is within the ambit of the legislature, not the courts” (ibid. at 330). One example of a statutory provision that overrides this general principle is the general anti-avoidance rule in s. 245 of the Income Tax Act (supra note 2). Pursuant to s. 245(4), a court is required to consider whether a transaction could reasonably be considered to result in a misuse of a particular provision or abuse of the Income Tax Act as a whole. Where this requirement as well as the other requirements in s. 245 are satisfied, then a court can tax the transaction under s. 245(2) in a manner that is reasonable in the circumstances.

-

[84]

Shell Canada, supra note 22 at para. 43. See also Canderel Ltd. v. Canada, [1998] 1 S.C.R. 147 at para. 41, 155 D.L.R. (4th) 257; Royal Bank of Canada v. Sparrow Electric, [1997] 1 S.C.R. 411 at para. 112, 143 D.L.R. (4th) 385.

-

[85]

See e.g. Lipson v. Canada, 2009 SCC 1, [2009] 1 S.C.R. 3 at para. 52, 301 D.L.R. (4th) 34.

-

[86]

Canada Trustco Mortgage v. Canada, 2005 SCC 54, [2005] 2 S.C.R. 601 at para. 12, 259 D.L.R. (4th) 193. See also Still v. M.N.R. (1997), [1998] 1 F.C. 549 at para. 45, 154 D.L.R. (4th) 229 (C.A.) [Still].

-

[87]

While McArthur T.C.J. did not find the parties’ conduct to be praiseworthy, he did believe that the Clinic was providing valuable services to its clients and that Dr. Rooney’s intentions in participating in the scheme were laudable. Given this generally positive view, he was not concerned that the Clinic would escape paying GST as a result of applying the Continental Bank approach. Indeed, I believe that he was so determined to find in favour of the parties that instead of fully applying the Continental Bank approach, once he determined that GST should not be applicable, he tried to justify it by (incorrectly) finding an agency relationship. In contrast, from the tone in the very first paragraph of his decision, it was clear that Décary J.A., on behalf of the Federal Court of Appeal, had a totally different opinion of the parties’ behaviour. Rather than being neutral or even positive towards the parties like McArthur T.C.J., he was offended by their actions. Not surprisingly, he chose to deviate from the Continental Bank approach in order to penalize them for their inappropriate behaviour.

-

[88]

It is unlikely that the Federal Court of Appeal’s finding that the sham had legal effect for tax purposes would ultimately prejudice OHIP on the basis of issue estoppel or abuse of process if it decided to take action against the parties for allegedly violating the provisions of the Ontario Health Insurance Act (supra note 50). However, a discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this paper. See generally C.R.B. Dunlop, Creditor-Debtor Law in Canada, 2d ed. (Toronto: Carswell, 1995) c. 19 (chapter written by P.J.M. Lown).

-

[89]

[1993] 2 S.C.R. 159, 101 D.L.R. (4th) 129 [Hall cited to S.C.R.].

-

[90]

Ibid. at 209. The full expression is ex turpi causa non oritur actio, which, in translation, means “no right of action arises from a base cause.”

-

[91]

Ibid. at 176 [reference omitted].

-

[92]

Ibid. at 169.

-

[93]

See e.g. Norberg v. Wynrib, [1992] 2 S.C.R. 226 at 316, 92 D.L.R. (4th) 449; Still, supra note 86 at paras. 12-37.

-

[94]

See especially Holman v. Johnson (1775), 98 E.R. 1120. Lord Mansfield held:

The principle of public policy is this; ex dolo malo non oritur actio. No Court will lend its aid to a man who founds his cause of action upon an immoral or an illegal act. If, from the plaintiff’s own stating or otherwise, the cause of action appears to arise ex turpi causâ, or the transgression of a positive law of this country, there the Court says he has no right to be assisted. It is upon that ground the Court goes; not for the sake of the defendant, but because they will not lend their aid to such a plaintiff.

ibid. at 1121 -

[95]

Hall, supra note 89 at 170.

-

[96]

Molinaro v. M.N.R., [1998] 2 C.T.C. (N.S.) 2871 at para. 27, 52 D.T.C. 1636 (T.C.C.) [Molinaro], aff’d (2000), 252 N.R. 178, [2000] 2 C.T.C. (N.S.) 12 (F.C.A.).

-

[97]

F.H. v. McDougall, 2008 SCC 53, [2008] 3 S.C.R. 41 at para. 46, 297 D.L.R. (4th) 193 [F.H.]. Prior to this decision, some courts hearing sham cases took the position that while the standard balance of probabilities test governed, it would be more stringently applied or would be a more onerous burden to overcome where the parties who created the documentation were seeking to discredit it in court, especially where professionals were involved in the preparation, or the parties’ actions were generally questionable. For example, in Pallan v. M.N.R. ((1989), [1990] 1 C.T.C. (N.S.) 2257, 90 D.T.C. 1102 (T.C.C.) [Pallan cited to C.T.C. (N.S.)]), Christie A.C.J.T.C. described this increased burden as follows:

It must be understood that if taxpayers create a documented record of things said and done by them, or by them in concert with others, to achieve a commercial purpose and then seek to repudiate those things with evidence of allegations of conduct that is morally blameworthy in order to avoid an unanticipated assessment to tax, they face a formidable task. And that task will not be accomplished, in the absence of some special circumstance, an example of which does not occur to me, by their oral testimony alone. That evidence must be bolstered by some other evidence that has significant persuasive force of its own.

at 2264See also Molinaro, supra note 96; Paxton v. M.N.R. (1996), 97 D.T.C. 5012 at 5018, 206 N.R. 241 (F.C.A.); Al Meghji & Gerald Grenon, “An Analysis of Recent Avoidance Cases” in Report of Proceedings of Forty-Eighth Tax Conference, 1996 Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1997) 66:1 at 66:39-40. Care should be taken in relying on these decisions following the Pallan approach, as this concept of having varying degrees within the balance of probabilities test was specifically rejected in F.H. (supra note 97) by the Supreme Court of Canada. Rothstein J. stated the following on behalf of the Court:

Like the House of Lords, I think it is time to say, once and for all in Canada, that there is only one civil standard of proof at common law and that is proof on a balance of probabilities. Of course, context is all important and a judge should not be unmindful, where appropriate, of inherent probabilities or improbabilities or the seriousness of the allegations or consequences. However, these considerations do not change the standard of proof. I am of the respectful opinion that the alternatives I have listed above should be rejected for the reasons that follow.

ibid. at para. 40 -

[98]

See e.g. Fortin v. M.N.R. (1996), [1998] 2 C.T.C. (N.S.) 2163, 97 D.T.C. 950 (T.C.C.).