Résumés

Abstract

This study examines the effect of chief executive officer (CEO) overconfidence on tax avoidance practices. Based on a sample of French-listed firms, the results show that overconfident CEOs engage in high levels of tax avoidance suggesting that the overconfidence bias may lead CEOs’ to behave unethically and use deceitful tactics to avoid taxes. However, board gender diversity mitigates this behavior suggesting that female directors are good monitors on the board. Our findings give insights to policymakers who may consider gender diversity on top management positions in addition to the board of directors to prevent a loss in tax revenues.

Keywords:

- Tax avoidance,

- CEO overconfidence,

- board gender diversity,

- unethical behavior,

- quantile regression

Résumé

Cette étude examine l’effet de la surconfiance du président directeur général (PDG) sur les pratiques d’évitement fiscal. Sur la base d’un échantillon d’entreprises françaises cotées, les résultats montrent que les PDG surconfiants s’engagent dans des niveaux élevés d’évitement fiscal, ce qui suggère que le biais de surconfiance peut conduire les PDG à se comporter de manière non éthique pour éviter les impôts. Cependant, la diversité du genre dans le conseil atténue ce comportement, ce qui suggère que les femmes administrateurs sont des contrôleurs efficaces au sein du conseil. Nos résultats ont des implications importantes pour les législateurs qui pourraient envisager la diversité du genre aux postes de direction en plus du conseil d’administration pour éviter une perte de recettes fiscales.

Mots-clés :

- Évitement fiscal,

- surconfiance des PDG,

- diversité du genre au sein du conseil d’administration,

- comportement non éthique,

- régression quantile

Resumen

Este estudio examina el efecto del exceso de confianza de los consejeros delegados en las prácticas de evasión fiscal. Basándose en una muestra de empresas francesas que cotizan en bolsa, los resultados muestran que los directores generales con exceso de confianza incurren en altos niveles de evasión fiscal, lo que sugiere que el sesgo de exceso de confianza puede llevar a los directores generales a comportarse de forma poco ética y a utilizar tácticas engañosas para evadir impuestos. Sin embargo, la diversidad de género en los consejos de administración mitiga este comportamiento, lo que sugiere que las directoras son buenas vigilantes en el consejo. Nuestras conclusiones ofrecen una visión a los responsables políticos, que pueden considerar la diversidad de género en los puestos de alta dirección, además del consejo de administración, para evitar una pérdida de ingresos fiscales.

Palabras clave:

- Evasión fiscal,

- exceso de confianza de los directores generales,

- diversidad de género en los consejos de administración,

- comportamiento poco ético,

- regresión cuantílica

Corps de l’article

During the last decades, several high-profile scandals (Enron, Freddie Mac, and Fannie Mae) have triggered researchers to study the effect of the personal traits of chief executive officers (CEOs) on ethical decision-making. The latter is decision-making in situations where ethical conflicts are present (Cohen et al., 2001). Kohlberg’s (1969) theory of cognitive moral development provides an understanding of the ethical behavior of individuals facing ethical dilemmas in their work. According to Rest (1986), an individual first should interpret a given situation as an ethical problem and identify morally correct options. Then, he should have a sufficient strength of character to behave ethically, even if self-interest dictates otherwise. Several factors have an impact on the cognitive moral development of individuals, namely: age (Ponemon and Gabhart, 1990), gender (Sweeney, 1995), academic level (Shaub, 1994) and personal traits (Tao et al. 2020).

The upper echelons theory highlights how top managers’ personal traits can influence organizational strategies, decisions, and outcomes (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). As key senior managers, CEOs play a major role in strategic decision-making (McManus, 2018). Top managers’ values, cognitive profiles, and biases including the overconfidence cognitive bias may influence their individual decision-making processes.

In the psychology literature, Kruger (1999) argues that overconfidence is the tendency of individuals to consider themselves above average on positive characteristics. Aragón and Roulund (2020) document that overconfidence is not only limited to a heightened sense of one’s abilities, but also includes the idea that one is superior to others. Overconfidence affects the basis for judgment and decision-making. In this sense, Plous (1993, p. 217) states that “no problem in judgment and decision-making is more relevant and more potentially catastrophic than overconfidence.” Thus, overconfidence can have strong consequences in different areas, such as wars, strikes, litigation, stock market bubbles, and corporate investments (Malmendier and Tate, 2005). Given its importance, overconfidence has been widely studied, even outside the field of psychology.

Overconfident CEOs influence decision-making such as corporate investments (Malmendier and Tate, 2005), acquisitions (Chatterjee and Hambrick, 2007), debt issuance (Malmendier et al., 2011) dividend policy (Deshmukh et al., 2013), and research and development investments (Hirshleifer et al., 2012). The effect of CEO overconfidence on different outcomes is well documented from the perspective of excessive risk taking. These studies document that overconfident CEOs engage in more risk-taking activities than non-overconfident CEOs (Malmendier and Tate, 2005). The rationale behind these results is that overconfident CEOs are overly optimistic about investments and growth opportunities. They overestimate the expected returns of their investments and underestimate the risk (Banerjee et al., 2015). Consequently, they invest more in riskier activities than non-overconfident CEOs.

However, the effect of overconfidence bias from the ethical behavior perspective needs further investigation. This perspective is relevant because a firm’s ethical climate is significantly influenced by the behavior and decisions of its top executives, especially the CEO (Chen, 2010). Kohlberg’s (1969) theory of cognitive moral development provides an understanding of the ethical behavior of individuals facing ethical dilemmas in their work. The overconfidence cognitive bias is likely to alter the cognitive moral development of CEOs and to affect the CEOs’ ethical behavior regarding firm decisions. In addition, according to Schweitzer et al. (2004), people with unmet goals tend to engage in an unethical behavior. Consequently, overconfident CEOs can be confronted with a gap between their actual performance and their expectations and may then engage in unethical behavior if they fall short of their goals. For instance, McManus (2018) argues that CEOs influenced by hubris are more likely to make unethical choices in the form of earnings manipulation.

We draw on the ethical perspective of CEO overconfidence and examine its effect on tax avoidance practices, particularly, aggressive ones. Kubick et al. (2020) argue that corporate taxes represent a significant cost to firms and shareholders, and tax planning has become an important strategic issue for executives. Indeed, CEOs are generally not tax experts, but they set the tone at the top, which could explain their engagement in tax avoidance. Dyreng et al. (2010) define tax avoidance as anything that reduces a firm’s taxes relative to its pre-tax accounting income. It is considered as one of the dimensions within the broader domain of tax ethics (Doyle et al., 2014). However, according to Payne and Raiborn (2018), only aggressive tax avoidance is ethically unacceptable. Indeed, aggressive tax practices are based on a suspect legal interpretation or a questionable tax position, taking advantage of a legal loophole. Firms that engage in such tax practices are not paying their fair share of taxes that are used to preserve or promote the public good and hence, they are forcing others to compensate for their reduced payments. This supports the fact that aggressive tax avoidance is morally wrong (Payne and Raiborn, 2018). Thus, decisions about tax practices involve ethical conflicts, which makes it worthwhile to study the subject from an ethical perspective.

Hsieh et al. (2018) argue that the effect of the intrinsic personal traits of executives on tax avoidance is still unclear. We then draw on their work to examine the effect of overconfident CEOs on tax avoidance practices and to further explore the role of board gender diversity. Females are usually described as being more ethical than males when making decisions. Compared to males, females hold different attitudes toward codes of ethics and use different decision rules regarding ethical evaluations (Ho et al., 2015). Accordingly, the ethical leadership of female directors contributes to more ethical practices and a better monitoring of managerial actions (Carter et al. 2003; Cumming et al., 2015). We extend this line of research by relating female directors’ ethical behavior to tax avoidance practices and predict a weaker effect of overconfidence on tax avoidance when the board of directors appoints more women.

Based on a sample of 178 French firms listed on the CAC All-Shares index from 2007 to 2017 and using quantile regressions, we find a positive and significant effect of CEO overconfidence on high levels of tax avoidance. The results also show that this effect is less prevalent when a large proportion of women are appointed in the boardroom. This result suggests that women’s ethical characteristics and their monitoring role counterweight the cognitive bias of overconfidence. Our findings are robust to alternative proxies of CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance, as well as to endogeneity concerns.

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we extend previous research on the effect of CEOs cognitive bias on corporate tax avoidance. Unlike previous studies (Hsieh et al., 2018 and Chyz et al., 2019) that focus on the risk-taking behavior, we shed light on the relationship between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance by examining the drivers of tax practices from an ethical perspective. Overconfident CEOs engage in tax avoidance because they take more risks and overestimate their abilities and judgements. However, as the net expected returns to tax avoidance increase with CEO overconfidence and the set goals are more difficult to achieve, overconfident CEOs can adopt unethical behavior by engaging particularly in high levels of tax avoidance practices, that is aggressive tax positions.

Second, we also link the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance to board gender diversity as a good corporate governance device. Hence, our study contributes to the accounting and ethic literature by examining the behavior of overconfident CEO regarding tax practices, taking into consideration the ethical inclinations of female directors on the board.

Third, we use the quantile regression approach to draw a more complete inference on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance. Quantile regressions allow us to determine whether the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance varies across the tax avoidance distribution. Our study would enhance the empirical results on the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance and lead to more nuanced theories of managers-corporate strategy relations, providing us with a deeper appreciation of how CEO overconfidence impacts the different levels of tax avoidance practices, particularly unusual ones.

Finally, although France has high tax rates, a recent note by the Council of Economic Analysis[1], stipulates that the loss of revenue from tax avoidance practices of French companies is estimated at 3.3 billion euros each year[2]. It is therefore important to understand the determinants of these practices to better prevent them. France has also adopted the Copé-Zimmerman law in 2011 with an application in 2017. This law promotes women representation on the board by constraining firms to appoint a quota of 40% of women on boards for French listed companies. This coercive approach may have important changes in the way boards behave regarding managerial decisions including tax behavior.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the sample, model specification, and variable measurement. The empirical results and their discussion are detailed in section 4. The last section concludes the paper.

Literature review and hypotheses’ development

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance

Managerial overconfidence is the tendency of managers to overestimate their knowledge and capabilities, resulting in overly optimistic expectations and even unrealistic outcomes (Hirshleifer et al., 2012). Numerous studies have long documented that overconfident CEOs are more likely to undertake riskier decisions (Malmendier and Tate, 2005; Chatterjee and Hambrick, 2007; Malmendier et al., 2011). Indeed, overconfident CEOs overestimate their investments and opportunities and take more risk compared to other less overconfident CEOs (Banerjee et al., 2015).

Recently, studies have focused on the effect of CEO overconfidence on corporate tax avoidance (Chyz et al. 2019; Hsieh et al., 2018). The literature has come to view tax avoidance as an important corporate strategy (Kanagaretnam et al., 2018). Most prior studies have emphasized corporate governance models, exploring the role of agency frictions in explaining variations in tax avoidance strategies. However, Hanlon and Heitzman (2010) argue that the agency theory perspective is not enough to explain variations in tax avoidance, since the latter can be highly idiosyncratic. Armstrong et al. (2015) argue that tax avoidance analyses should be conducted from a more behavioral perspective. Indeed, individual moral beliefs influence tax compliance decisions (Reckers et al. 1994). As the CEO has significant influence on a firm’s tax strategy, it is important to examine the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance practices.

The existing literature has investigated the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance from a risk-taking perspective (Hsieh et al., 2018 and Chyz et al., 2019). Indeed, overconfident CEOs are likely to engage in tax avoidance practices and may take risky positions to obtain more resources for their investment projects. Hsieh et al. (2018) examine how overconfident CEOs interact with their CFOs to influence firm’s tax avoidance. The authors find that firms engage in tax avoidance activities when both the CEO and CFO are overconfident, compared with companies with other CEO–CFO overconfidence combinations. Chyz et al. (2019) investigate the effect of CEO overconfidence on the tax avoidance behavior, considering exogenous CEO turnover events. They provide evidence that overconfident CEOs positively influence corporate tax avoidance. According to Chyz et al. (2019), overconfident CEOs are optimistically biased in relation to tax avoidance because they overestimate the benefits to tax avoidance and underestimate its costs as well as their subjective probabilities of occurrence which may lead to higher expected net returns from tax avoidance[3].

The effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance could be also examined form an alternative behavioral perspective. Kohlberg’s (1969) theory of cognitive moral development provides an understanding of the ethical behavior of individuals facing ethical dilemmas in their work. According to Tao et al. (2020), personal traits may have an influence on the cognitive moral development which in turn affect their decision-making. Consequently, we argue that the overconfidence bias is likely to alter the cognitive moral development of CEOs and to affect the CEOs’ ethical behavior regarding tax practices. Moreover, since overconfident CEOs tend to overestimate their abilities, judgments, and prospects, it could be difficult for them to achieve their set goals (Hirshleifer et al., 2012). Consequently, falling short of reaching the set goals drives individuals to behave unethically (Schweitzer et al., 2004). Building on this behavioral perspective, we hypothesize that overconfident CEOs may engage in unethical corporate tax practices.

From an ethical point of view, tax avoidance is ethically acceptable when it uses legal means to reduce the amount of tax based on numerated provisions in the tax law (Payne and Raiborn, 2018). According to Desai and Dharmapala (2009), reducing tax payments is viewed as a means to increase shareholder’s wealth. However, aggressive tax avoidance (i.e. high levels of tax avoidance) is considered as a rent extraction strategy and is then designed to expropriate firm resources (Desai and Dharmapala, 2006). Indeed, managers that engage aggressively in tax practices use loopholes in the tax law and complexity to avoid their detection by tax authorities. These high levels in avoiding taxes are considered unethical according to Payne and Raiborn (2018).

The preceding discussion suggests that tax avoidance (low levels of tax avoidance practices) may be ethically acceptable, whereas aggressive tax avoidance (high ones) is not. Given that overconfident CEOs tend to engage in an unethical behavior to meet their goals, we expect overconfident CEOs to engage in high levels of tax practices i.e. aggressive ones. Our first hypothesis is then as follows:

H1. CEO overconfidence positively influences tax avoidance practices, particularly aggressive ones.

The role of board gender diversity

There has been extensive theoretical and empirical work on the benefits to having gender-diverse boards (see Post and Byran, 2015 and Nguyen el al. 2020 for a comprehensive review). Among these benefits, the literature concurs that the presence of women on the boardroom is associated with more ethical decision-making and lower fraudulent strategies (Cumming et al., 2015; Grosh and Rau, 2017). The effect of board gender diversity on the CEO overconfidence-tax avoidance relationship is motivated through two theoretical perspectives.

First, according to the gender socialization theory (Dawson, 1997), since their childhood, men and women learn different values and preoccupations, which build their personalities. As a result, men and women are psychologically and cognitively different when it comes to moral principles. Women have been shown to be more ethically sensitive than men and more risk averse (Cumming et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 1998; Mason and Mudrack, 1996). Previous studies have found that women tend to exhibit higher levels of ethical decision-making in comparison to their male counterparts. Indeed, a review by Collins (2000) shows that 32 of 47 studies highlight that women are more ethically sensitive than their male counterparts. The literature on tax avoidance document that men are less tax compliant and have lower tax morale than women (Torgler and Schneider, 2007).

Kaplan et al. (2009) find that women have a lower likelihood of engaging in unethical behaviors and are less likely to act in immoral ways for financial gain. Moreover, Crozon and Gneezy (2009) report that women tend to view risk situations as threats rather than challenges, which lead to increased risk aversion. Kramer et al., (2006) argue that when firms include women among their board members, a qualitative change is deemed to take place in the nature of group interactions. Women bring a collaborative leadership style that benefits boardroom dynamics by increasing the amount of listening, social support, and win-win problem solving. Consequently, we may expect that the presence of women on boards alleviates the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance, as they will act ethically to prevent the associated risk with tax avoidance practices.

Second, beyond their higher ethical values, and from an agency perspective, the board of directors plays a major role in monitoring and driving strategic decisions. Women directors enhance the effectiveness of board monitoring and are considered as a good corporate governance device (Carter et al. 2003). Adams and Ferreira (2009) argue that more diverse board can be considered a better controlling mechanism for managers as it enhances the board independence and prevents an individual or group of people to dominate the decision-making process. Benkraiem et al., (2021) also document that women are more likely than men to act similarly to independent directors, which may strengthen the monitoring action and reduce agency costs.

Consequently, we consider female presence on boards to improve the monitoring of board decisions and expect that board gender diversity to mitigate the engagement of overconfident CEOs in aggressive tax practices.

Based on the above-cited theoretical perspectives, the presence of high proportion of female directors may serve as a substitute mechanism for corporate governance to avoid unethical strategies and curb aggressive tax avoidance by overconfident CEOs. We then formulate our second hypothesis as follows:

H2. The positive effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance practices is less prevalent in firms with gender diverse boards.

Research design

Data

We use an initial sample of 525 French listed firms listed on the CAC All-Shares index from 2007 to 2017. We exclude 63 companies that were not listed or are delisted from the stock market during the sample period. We also omit financial firms, as they are subject to different regulations and have specific financial and accounting characteristics. Finally, we remove firms with missing or unavailable financial data. The final sample includes 1,958 firm–year observations for 178 firms. Financial and accounting data were extracted from the Compustat database. Data on gender diversity on the top management team and on the board were hand-collected from annual reports. Finally, data on CEO overconfidence were collected from the web site of the French Market Authority (AMF).

Variables’ measurement

Corporate tax avoidance

Following Atwood et al. (2012), we compute tax avoidance as the difference between unmanaged tax and current tax paid scaled by pre-tax income. The unmanaged tax is the amount of pre-tax income multiplied by the French statutory tax rate. To better capture tax avoidance activities, we use a long-term measure over five years. The value of this measure is an increasing function of the level of firm tax avoidance. Our measure of tax avoidance (TaxAvoid) for firm i in year t is calculated as follows:

CEO overconfidence

Following Malmendier and Tate (2005), we use the net buyer measure (NetBuyer). This proxy captures CEO overconfidence through their behavior to buy company’s stocks more than selling those stocks. Malmendier and Tate (2005) argue that NetBuyer is a characteristic of an irrational behavior of under-diversification of risk. Indeed, buying the stocks of the company leads the CEO to be exposed to a high specific risk. This means that when a manager buys more company’s stocks than he sells, he overestimates the performance of his company and is then considered overconfident. We then construct a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the CEO buys more of his own-company stocks than he sells annually and zero otherwise.

Female directors

We estimate the presence of women on the board by the proportion of female directors on the board.

Control variables

Following prior studies, we include control variables to address confounding factors that could predict corporate tax avoidance. Previous literature shows that firm and governance characteristics affect tax avoidance (Overesch et al., 2020). We include firm size (SIZE) and leverage (LEV) to capture differences in the propensity to invest in tax-favored assets. Large firms enjoy economies of scale in tax planning, while firms with great leverage have less incentives to engage in tax avoidance due to the tax shield of debt (Hanlon and Heitzman, 2010).

We also control for firm profitability (ROA), tax-loss carryforwards (LOSS), and growth opportunities (MTB). Firms with negative pre-tax income or significant net operating carryforwards are likely to have less incentive to avoid taxes. Moreover, firms with high growth opportunities invest more in tax planning activities (Hoi et al., 2013). To control for basic operating decisions that could have unintentional tax consequences, as well as for differences in financial and tax reporting rules, we include the following controls: gross property, plant, and equipment, divided by total assets (PPE), and research and development expenses divided by total assets (R&D).

In addition, following Hoi et al., (2013), we use additional control variables for cash holdings (SLACK), information quality (INF_Q), and auditor size (BIG 4). These variables are deemed to influence corporate tax practices. Lastly, since tax planning opportunities can vary by industry and over time, we run the regressions with year and industry dummies effects. The control variables are defined in the Appendix.

Model Specification

We estimate the following regression models using ordinary least squares (OLS) and quantile regressions:

Our goal is to test the effect of CEO overconfidence on different levels of tax avoidance, particularly high (aggressive) ones. The classic linear OLS regression focuses on the effect of CEO overconfidence on the conditional mean of tax avoidance. The assumption in this model is that the CEO overconfidence effect is constant across the tax avoidance distribution. However, quantile regression allows for a more precise description of the conditional distribution of the tax avoidance variable. The quantile regression approach predicts not only the central tendency of our dependent variable, that is, tax avoidance, but also the effects of CEO overconfidence on different quantiles of tax avoidance (25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles). This gives a fuller picture of the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax reduction practices. The quantile regression is suitable for this study as it allows to test a heterogenous effect of CEO overconfidence across the tax avoidance distribution to compare the effect on high levels of tax avoidance (75th and 90th percentiles) with lower levels (25th and 50th percentiles).

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics

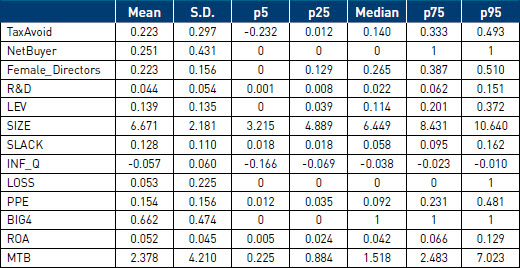

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics. The mean (median) value of TaxAvoid is 0.223 (0.140) which is lower than the values reported by Overesch et al. (2020) for the European (0.28) and American (0.26) firms. French firms seem to avoid less taxes than their peers in the European and U.S context. As for managerial overconfidence, 25.1%% of the managers in our sample are considered overconfident, which is lower than the proportion of 35.3% reported by Kim et al. (2016) in US companies. In addition, the average proportion of female directors in the board is 22.3%. This proportion is comparable to the proportion of 20.28% reported by Brahem et al. (2021) in the French context.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics

This table reports descriptive statistics for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions.

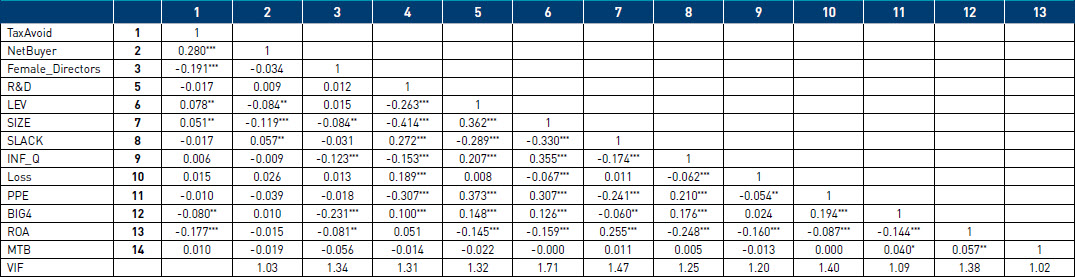

Table 2

Pearson correlation matrix

This table displays Pearson correlation matrix for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 2 reports the Pearson correlations among the variables used in our regression models. CEO overconfidence is positively correlated with TaxAvoid, which is intuitionally consistent with H1. The correlations among the control variables in our models are relatively small and below the critical value of 0.8. In addition, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIFs) for each variable range from 1.02 to 1.71, far below the critical value of 10 (Neter et al., 1989), which suggests that multicollinearity is not likely to be an issue in our multivariate tests.

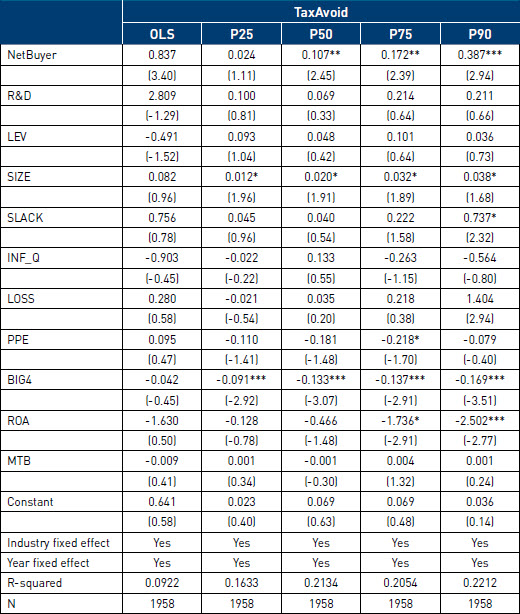

Multivariate regressions

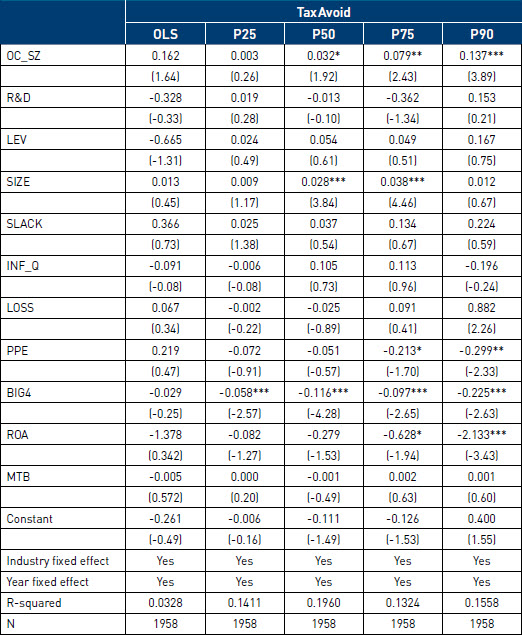

Table 3 reports the results of the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance. The results of the OLS model show a positive but nonsignificant relation between CEO overconfidence (NetBuyer) and corporate tax avoidance (TaxAvoid). However, the results of the quantile regressions reported in the second to fifth columns of Table 3 show different effects of CEO overconfidence across the percentiles of tax avoidance. For instance, at the 25th percentile, that is, for low levels of tax avoidance, there is a nonsignificant relation between the overconfidence Netbuyer measure and tax avoidance. This means that CEO overconfidence does not affect tax avoidance in low tax avoiding firms. However, at high levels of tax avoidance (50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles), we document a positive relation, respectively, at the 5%, and 1% levels of significance. The strongest magnitude is recorded for the highest level of tax avoidance. Indeed, this positive effect of CEO overconfidence is increasing from the 50th percentile (0.107), to reach the highest level of tax avoidance for the last, 90th percentile (0.387). This result suggests that overconfident CEOs actively engage in aggressive tax avoidance practices to minimize the tax burden. This result supports H1 according to which there is a positive effect of CEO overconfidence on particularly high levels of tax avoidance practices.

The findings support the ethical behavior view, suggesting that the CEO overconfidence as a personal trait may have an influence on the cognitive moral development (Tao et al. 2020) and may alter the CEOs’ ethical behavior regarding tax practices. This leads to a high engagement in tax avoidance practices. Moreover, consistent with Payne and Raiborn (2018), this finding suggests that overconfident CEOs are more likely to use tax loopholes to reduce tax payments. Since such CEOs exhibit an optimistic bias and initially overstate earnings, they have high incentives to recourse to high tax avoidance practices i.e. aggressive ones that are considered as unethically acceptable practices.

For the control variables, the results in Table 3 show a positive and significant relation between firm size and all levels of tax avoidance at the 10% level. Large firms are more likely than small firms to engage in corporate tax avoidance. This finding is consistent with Dyreng et al. (2010), who concluded that smaller firms pay more taxes per tax dollar earned.

Moreover, Table 3 documents a negative and significant relation between profitability (ROA) and higher levels of tax avoidance (75th and 90th percentiles), suggesting that firms with a higher return on assets have less incentives to engage in aggressive tax practices. This result is consistent with Gupta and Newberry (1997) who find a positive and significant effect of ROA on effective tax rate (ETR). However, our result is inconsistent with the finding of Armstrong et al. (2015), who argue that more profitable firms have higher income tax expenses, but lower cash tax payments. Our result confirms the inconsistent findings in previous tax avoidance research for ROA (Taylor and Richardson, 2013).

Table 3

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance

This table reports the OLS and quantile regressions results of the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and year. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

The results also show a negative relation between auditor size (BIG 4) and tax avoidance. The negative effect is increasing through the tax avoidance variable percentiles. The strongest magnitude is recorded for a high level of tax avoidance (90th percentile), suggesting that Big 4 auditing firms could curb a firm’s incentive to avoid taxes by strongly monitoring corporate decisions. Finally, the findings show a nonsignificant relation between leverage and tax avoidance, which is inconsistent with the conventional hypothesis according to which the increase in debt is associated with lower tax rates.

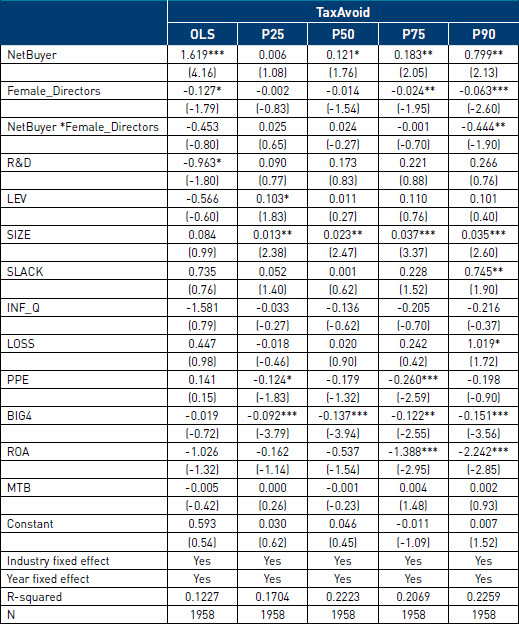

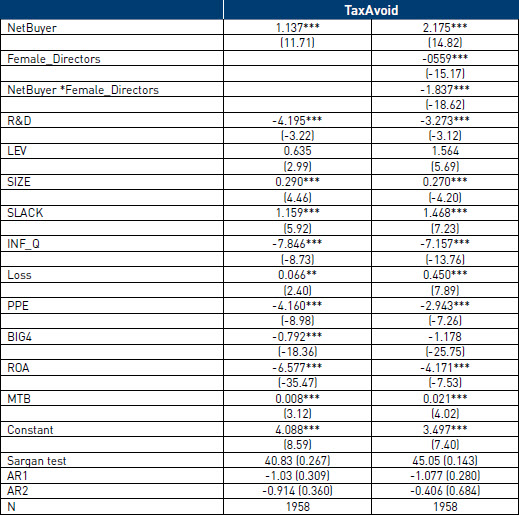

We now test the moderating effect of board gender diversity on the CEO overconfidence-tax avoidance relationship. The results in Table 4 show that the presence of female directors on the board is negatively associated with tax avoidance for the upper percentiles of the tax avoidance variable (75th and 90th). This result suggests that board gender diversity is a good monitoring tool constraining aggressive tax avoidance practices. In addition, women appointed on the board of directors are likely to exhibit ethical decision-making and to be more tax compliant than their male counterparts.

The findings in Table 4 also document a negative association between the interaction term NetBuyer*Female_Directors and tax avoidance at lower and higher percentiles. The most negative and significant effect is recorded for the upper percentile of tax avoidance. This means that the positive effect of CEO overconfidence on high levels of tax avoidance is mitigated when women are standing on the board. These results suggest that beyond their higher ethical values, women directors enhance the effectiveness of board monitoring and are considered as a good corporate governance device in French-listed companies. Hence, the Copé-Zimmermann law adopted in 2011 in France promoting the representation of women on the boardroom, is likely to improve the decision-making of the board. Indeed, the law imposes a quota of 40% of women appointed on the board starting from 2017.

Robustness checks

Alternative proxy for CEO Overconfidence: We check the robustness of our results using an alternative measure of CEO overconfidence. Following Schrand and Zechman (2012) and Kim et al. (2016), our alternative measure of CEO overconfidence (OC_SZ) is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm meets at least three of the following five criteria, and zero otherwise: i) the firm’s excess investment is in a high quartile within industry–years, with excess investment being the residual from a regression of total asset growth on sales growth; ii) net acquisitions, obtained from cash flow statements, are in the top quartile within industry–years; iii) the firm’s debt-to-equity ratio, defined as the sum of long-term and short-term debt, divided by total assets, is in the top quartile within industry–years; iv) the firm uses convertible debt or the preferred stock is higher than zero, indicated by a binary variable; and v) the firm pays dividends, indicated by a dummy variable. Indeed, CEO overconfidence is highly correlated to firm’s risk taking. Table 5 reports the results on the effect of OC_SZ on upper percentiles (50%, 75% and 90%) of tax avoidance suggesting a positive relation between CEO overconfidence and high levels of tax avoidance. These findings give support to our main results.

Alternative proxies for tax avoidance: We check the sensitivity of our findings using alternative proxies for tax avoidance. The first proxy is the effective tax rate (TA_ETR). ETR is computed as total tax expenses, including both current and deferred tax expenses, divided by pre-tax income before special items. TA_ETR is defined as (-1) times ETR. The second proxy is the cash effective tax rate (TA_CETR). Cash effective tax rate (CETR) is defined as cash tax paid divided by pre-tax book income minus special items. TA_CETR is defined as (-1) times CETR. Table 6 shows that the results remain qualitatively the same when these proxies are used for tax avoidance practices.

Table 4

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance: Moderating effect of female directors

This table reports the OLS and quantile regressions results of the moderating effect of female directors on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and year. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 5

Alternative measure of CEO overconfidence

This table reports the quantile regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. OC_SZ is the alternative measure of CEO overconfidence. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 6

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance: Moderating effect of female directors

This table reports the OLS regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance and the moderating effect of female directors on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Tax aggressiveness: We test the effect of overconfidence on tax aggressiveness, that is, high levels of tax avoidance practices. Following Kanagaretnam et al. (2018), we measure tax aggressiveness using a dummy variable that equals to 1 if tax avoidance is within the top quintile in each year–industry combination, and zero otherwise. This measure captures the extreme end of the tax avoidance spectrum. The results reported in Table 7 show a positive and significant effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance. Moreover, similar to our main findings, this positive relation is less prevalent in the presence of female directors.

Table 7

The tax aggressiveness measure

This table reports the OLS regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax aggressiveness and the moderating effect of female directors on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax aggressiveness for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Endogeneity issue: We use the generalized method of moments (GMM), because it helps prevent endogeneity issues. Overconfident CEOs can self-select into companies with high growth and business risk. Moreover, Hasan et al. (2017) show a negative association between firm growth and tax avoidance. This overconfidence–growth matching issue is addressed using firm growth and risk as instrumental variables (the market-to-book ratio and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, respectively). The results of these tests are reported in Table 8 and show that the overall results remain qualitatively the same for GMM estimations.

Table 8

GMM regression

This table reports the GMM regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance and the moderating effect of female directors on the relationship between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax practices particularly, aggressive ones. This study also investigates the moderating effect of board gender diversity on the CEO overconfidence and tax practices relation. Based on a sample of 178 French listed firms on the CAC All-Shares index from 2007 to 2017 and using both OLS and quantile regressions, we find that overconfident CEOs engage in high levels of tax avoidance. The positive effect of overconfidence on tax avoidance increases to reach the highest level of tax avoidance, the last percentile (90th), suggesting that overconfident CEOs actively engage in tax avoidance to minimize the tax burden. The findings also suggest that CEO overconfidence as a personal trait may have an influence on the cognitive moral development and alter the CEOs’ ethical behavior regarding tax practices. This leads CEOs to use deceitful tactics to avoid corporate tax obligations.

We further provide new evidence that female directors moderate the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax practices. We show that female directors are less likely to engage in aggressive tax practices. Female directors are good monitors on the board and exhibit fewer unethical tax saving activities. Our findings are robust to alternative measures of CEO overconfidence, tax avoidance and endogeneity concern.

This study has several practical implications for investors, boards of directors, and regulatory authorities, who are interested in corporate tax practices. First, it helps investors understanding the CEOs’ decision-making process in terms of tax payment. It also gives insights to the board of directors regarding their decisions on CEOs appointments. Finally, following the implementation of the Copé-Zimmerman law, policymakers may also consider top management gender diversity in addition to the board of directors to prevent a loss in tax revenues. In France, the latest governance code of AFEP-MEDEF (2020) has strongly recommended the appointment of women on top management to increase gender diversity in leadership positions which may lead to an increase in tax compliance of French-listed companies.

Parties annexes

Appendix

Appendix A. Variables’ definitions

Biographical notes

Faten Lakhal is a Professor in Accounting at EMLV Business School in France and a fellow researcher at the Institut de Recherche en Gestion at Paris-Est University (France). Her major publications include studies in Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Management International, Managerial Auditing Journal, Gender, Work & Organization, Economic Modelling among others. Her special research interests are in corporate governance, earnings quality, tax avoidance, gender diversity and CSR.

Sabrina Khemiri is an associate professor in corporate finance at Institut Mines-Télécom Business School. She holds her PhD in management from the IAE of Aix-en-Provence, Aix-Marseille University. Her research interests include financing choice, finance innovation through corporate venture capital and corporate governance. She published several papers in international peer-reviewed journals. In addition to her research activities, she teaches several courses related to corporate finance and financial markets.

Sami Bacha is an assistant Professor in accounting and finance at the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management of Sousse. His special research interests are in corporate governance, corporate disclosure, Corporate Social Responsibility, tax avoidance, Bank risks and auditing. His major publications include Bankers, Markets and Investors, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, Corporate Governance, Cogent Economic and Finance, Theoretical Economic Letters, International Journal of Business and Financial Management Research, International Journal of Empirical Finance among others.

Assil Guizani is a Professor of Finance at Nanterre University. He holds a Ph.D. in Finance from Nanterre University in 2020. His research interests lie mainly within the determinates and the consequences of stock price crash, corporate governance, corporate social responsibility. He published several papers in international peer-reviewed journals.

Notes

- [1]

- [2]

-

[3]

The returns of tax avoidance include reduced accounting tax expense and reduced cash tax outflows. The cost of tax avoidance consists of explicit tax costs (if tax practices are overturned) and multiple other costs (tax strategy implementation costs, implicit taxes, costs subsequent litigation and reputational penalties).

Bibliography

- Adams, Renée; Ferreira, Daniel (2009). “Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance”. Journal of financial economics, Vol. 94 N° 2, p. 291-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Aragon, Nicolás; Roulund, Rasmus P. (2020). “Confidence and decision-making in experimental asset markets”. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2020, Vol. 178, p. 688-718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.07.032

- Armstrong, Christopher S.; Blouin, Jennifer L.; Jagolinzer, Alan D.; David A. Larcker (2015). “Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 60, N° 1, p. 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.02.003

- Atwood, T. J.; Drake, Michael S.; Myers, James N.; Linda A. Myers (2012). “Home Country Tax System Characteristics and Corporate Tax Avoidance: International Evidence”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 87, N° 6, p. 1831-1860. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50222

- Banerjee, Suman.; Humphery-Jenner, Mark.; Vikram, Nanda (2015). “Restraining overconfident CEOs through improved governance: Evidence from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 28, N° 10, p. 2812-2858. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhv034

- Benkraiem, Ramzi; Boubaker, Sabri; Brinette, Souad; Khemiri, Sabrina (2021). “Board feminization and innovation through corporate venture capital investments: the moderating effects of independence and management skills”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, p. 120467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120467

- Brahem, Emna; Depoers, Florence; Lakhal, Faten (2021). “Family Control and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effect of the Board of Directors”, Management international-Mi, 25 (2), p. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.7202/1077793ar

- Carter, David A.; Simkins, Betty J.; Simpson, Gary W. (2003). “Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value”, Financial Review, Vol. 38, N° 1, p. 35-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6288.00034

- Chatterjee, Arijit; Donald C. Hambrick (2007). “It’s all about me: Narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 52, N° 3, p. 351-386. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.3.351

- Chen, Stephen (2010). “The role of ethical leadership versus institutional constraints: A simulation study of financial misreporting by CEOs”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 93, N° 1, p. 33-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0625-8

- Chyz, James A.; Gaertner, Fabio B.; Kausar, Asad.; Luke, Watson (2019). “Overconfidence and corporate tax policy”, Review of Accounting Studies, Vol, 24, N° 3, p. 1114-1145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-09494-z

- Cohen, Jeffrey R.; Pant, Laurie W.; Sharp, David J. (1998). “The effect of gender and academic discipline diversity on the ethical evaluations, ethical intentions and ethical orientation of potential public accounting recruits”, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 12, p. 250-270.

- Cohen, Jeffrey R.; Pant, Laurie W.; Sharp, David J. (2001), “An Examination of Differences in Ethical Decision-Making Between Canadian Business Students and Accounting Professionals”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol.30, p. 319-336. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010745425675

- Collins, Denis (2000). “The quest to improve the human condition: The first 1 500 articles published in Journal of Business Ethics”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 26, N° 1, p. 1-73. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006358104098

- Cumming, Douglas.; Leung, Tan Y.; Oliver, Rui (2015). “Gender diversity and securities fraud”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 58, N° 5, p. 1572-1593. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0750

- Dawson, Leslie M. (1997). “Ethical differences between men and women in the sales profession”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 16, p. 1143-1152. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005721916646

- Desai, Mihir A.; Dhammika, Dharmapala (2006) “Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 79, N° 1, p. 145-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.02.002

- Desai, Mihir A.; Dhammika, Dharmapala (2009) “Corporate tax avoidance and firm value”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 91, N° 3, p. 537-546.

- Deshmukh, Sanjay.; Goel, Anand M.; Keith M. Howe (2013). “CEO overconfidence and dividend policy”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 22, N° 3, p. 440-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2013.02.003

- Doyle, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., and Summers, J. (2014). Ethics in tax practice: A study of the effect of practitioner firm size. Journal of Business Ethics 122(4),p. 623-641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1780-5

- Dyreng, Scott D.; Hanlon, Michelle.; Edward L. Maydew (2010). “The effects of executives on corporate tax avoidance”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 85, N° 4, p. 1163-1189. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.4.1163

- Grosch, Kerstin; Rau, Holger A. (2017). “Gender differences in honesty: The role of social value orientation”. Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 62, p. 258-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.07.008

- Gupta, S., & Newberry, K. (1997). “Determinants of the variability on corporate effective tax Rates: Evidence from longitudinal data”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 16, N° 1, p. 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4254(96)00055-5

- Hambrick, Donald C.; Phyllis A. Mason (1984). “Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9, N° 2, p. 193-206. https://doi.org/10.2307/258434

- Hanlon, Michelle.; Shane, Heitzman (2010). “A review of tax research”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 50, N° 3, p. 127-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.002

- Hasan, Mostafa M.; Al-Hadi, Ahmed.; Taylor, Grantley.; Grant, Richardson (2017). “Does a firm’s life cycle explain its propensity to engage in corporate tax avoidance?”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 26, N° 3, p. 469-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2016.1194220

- Hirshleifer, David.; Low, Angie.; Siew H. Teoh (2012). “Are overconfident CEOs better innovators?”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 67, N° 4, p. 1457-1498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01753.x

- Ho, Simon SM.; Li, Annie Y.; Tam, Kinsun.; Zhang, Feida (2015). “CEO gender, ethical leadership, and accounting conservatism”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 127, N° 2, p. 351-370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-2044-0

- Hoi, Chun K.; Wu, Qiang; Zhang, Hao (2013). “Is corporate social responsibility (CSR) associated with tax avoidance? Evidence from irresponsible CSR activities”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 88, N° 6, p. 2025-2059. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50544

- Hsieh, Tien-Shih.; Wang, Zhihong.; Demirkan, Sebahattin (2018). “Overconfidence and tax avoidance: The role of CEO and CFO interaction”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 37, N° 3, p. 241-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2018.04.004

- Kanagaretnam, K., Lee, J., Lim, C. Y., and Lobo, G. J. (2018). “Cross-country evidence on the role of independent media in constraining corporate tax aggressiveness”. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 150, N° 3, p. 879-902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3168-9

- Kaplan, Steven E.; Pany, Kurt, Samuels, Janet; Zhang, Jiang (2009). “An examination of the association between gender and reporting intentions for fraudulent financial reporting”. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 87 N° 1, p. 15-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9866-1

- Kim, Jeong-Bon.; Wang, Zheng.; Zhang, Liandong (2016). “CEO overconfidence and stock price crash risk”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 33, N° 4, p. 1720-1749. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12217

- Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and Sequence: The Cognitive Developmental Approach to Socialization. In Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research (Eds. Goslin, D. A.). Rand McNally, p. 347-380.

- Kramer, Vicky W.; Konrad, Alison M.; Erkut, Sumru; Hooper, Michele J. (2006). Critical mass on corporate boards: Why three or more women enhance governance (p. 2-4). Wellesley, MA: Wellesley Centers for Women.

- Kruger, Justin (1999). “Lake Wobegon be gone! The ‘below-average effect’ and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 77, N° 2, p. 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.221

- Kubick, Thomas R.; Lockhart, Brandon G.; John R. Robinson (2020). “Does Inside Debt Moderate Corporate Tax Avoidance?”, National Tax Journal, Vol. 73, N° 1, p. 47-76. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2020.1.02

- Malmendier, Ulrike.; Tate, Geoffrey (2005). “CEO overconfidence and corporate investment”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, N° 6, p. 2661-2700. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00813.x

- Malmendier, Ulrike.; Tate, Geoffrey.; Yan, Jon (2011). “Overconfidence and early life experiences: The effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 66, N° 5, p. 1687-1733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01685.x

- Mason, Sharon E.; Mudrack, Peter E. (1996), “Gender and ethical orientation: A test of gender and occupational socialization theories”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 15, p. 599-604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00411793

- McManus, Josaph (2018). “Hubris and unethical decision making: The tragedy of the uncommon”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 149, N° 1, p. 169-185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3087-9

- Neter, John.; Wasserman, William.; Kutner, Michael H (1989). Applied Linear Regression Models, Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

- Nguyen, Thi Hong H; Collins, Ntim G.; Malagila, John K. (2020), “Women on corporate boards and corporate financial and non-financial performance: A systematic literature review and future research agenda”, International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 71, 101554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101554

- Overesch, Michael.; Strueder, Sabine.; Wamser, Georg (2020). “Do U.S. Firms Avoid More Taxes Than Their European Peers? On Firm Characteristics and Tax Legislation as Determinants of Tax Differential”, National Tax Journal, Vol. 73, N° 2, p. 361-400. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2020.2.03

- Payne, Dinah M.; Cecily A. Raiborn (2018). “Aggressive tax avoidance: A conundrum for stakeholders, governments, and morality”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 147, N° 3, p. 469-487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2978-5

- Plous, Scott (1993). The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making, New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Ponemon, L. A.; Gabhart, D. R. L. (1990). “Auditor independence judgment: a cognitive developmental model and experimental evidence”. Contemporary Accounting Research, 7 (1), p. 227-251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1990.tb00812.x

- Post, Corinne, Byron, Kris (2015). “Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis”. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 58, N° 5, p. 1546-1571. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0319

- Reckers, Philip MJ.; Debra L. Sanders.; Stephen J. Roark (1994). “The Influence of Ethical Attitudes on Taxpayer Compliance”, National Tax Journal, Vol. 47, N° 4, p. 825-836. https://doi.org/10.1086/NTJ41789111

- Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Praeger.

- Schrand, Catherine M.; Sarah LC. Zechman (2012). “Executive overconfidence and the slippery slope to financial misreporting”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 53, N° 1, p. 311-329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2011.09.001

- Schweitzer, Maurice E.; Ordonez, Lisa.; Douma, Bambi (2004). “Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, N° 3, p. 422-432. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159591

- Shaub, M. K. (1994). “An analysis of the association of traditional demographic variables with the moral reasoning of auditing students and auditors”, Journal of Accounting Education, l-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0748-5751(94)90016-7

- Sweeney, J. T. (1995). “The moral expertise of auditors: An exploratory analysis”, Research on Accounting Ethics, N° 1, p. 213-234.

- Tao, Y., Ying C., Chandni, R., Yuan, Z., (2020), “The impact of the Extraversion-Introversion personality traits and emotions in a moral decision-making task”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 158, 109840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109840

- Taylor, G., Richardson, G. (2013), “The determinants of thinly capitalized tax avoidance structures: Evidence from Australian firms”, Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, Vol. 22, N° 1, p. 12-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2013.02.005

- Torgler, Benno.; Schneider, Friedrich (2007). “What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries”, Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 88, p. 443-470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00466.x

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Faten Lakhal est professeur de comptabilité à l’EMLV Business School en France et chercheur associé à l’Institut de Recherche en Gestion de l’Université Paris-Est (France). Elle a publié dans de nombreuses revues scientifiques, dont Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Management International, Managerial Auditing Journal, Gender, Work & Organization and Economic Modelling. Ses recherches portent sur la gouvernance d’entreprise, les entreprises familiales, la diversité du genre et la RSE.

Sabrina Khemiri est maître de conférences en finance d’entreprise à Institut Mines-Télécom Business School. Elle est docteur en sciences de gestion de l’IAE d’Aix-en-Provence, Université Aix-Marseille. Ses recherches actuelles portent principalement sur les choix de financement, le financement de l’innovation à travers le capital risque industriel et la gouvernance d’entreprises. Elle a publié plusieurs articles dans des revues internationales à comité de lecture. En plus de ses activités de recherche, elle dispense plusieurs enseignements liés à la finance d’entreprise et les marchés financiers.

Sami Bacha est Maître-assistant en comptabilité et finance à la faculté des sciences économiques et de gestion de Sousse. Son domaine de recherche est le gouvernement d’entreprises, la divulgation financière, la responsabilité sociale, les pratiques fiscales, les risques bancaires et l’audit. Sami a publié dans plusieurs revues telles que Bankers, Markets and Investors, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, Corporate Governance, Cogent Economic and Finance, Theoretical Economic Letters, International Journal of Business and Financial Management Research, International Journal of Empirical Finance.

Assil Guizani est enseignant chercheur de finance à l’université Paris Nanterre. Il est titulaire d’un doctorat en finance de l’Université Paris Nanterre obtenu en 2020. Ses recherches portent principalement sur les déterminants et les conséquences de chute du cours d’action, la gouvernance d’entreprise, et la responsabilité sociale des entreprises. Assil GUIZANI a publié de nombreux articles académiques dans des revues internationales.

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Faten Lakhal es profesor de contabilidad en la EMLV Business School en Francia e investigador asociado en el Institut de Recherche en Gestion de la Universidad de Paris-Est (Francia). Ha publicado en numerosas revistas científicas, incluidas Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Management International, Managemental Auditing Journal, Gender, Work & Organization, Economic Modelling, entre otras. Su investigación se centra en el gobierno corporativo, las empresas familiares, la diversidad de género y la RSE.

Sabrina Khemiri es profesora asociada en finanzas corporativas en el Instituto Mines-Télécom Business School. Es doctora en gestión por el IAE de Aix-en-Provence, Universidad de Aix-Marsella. Sus intereses de investigación incluyen la elección de la financiación, la innovación financiera a través del capital riesgo de las empresas y la gobernanza corporativa. Ha publicado varios artículos en revistas internacionales revisadas por expertos. Además de sus actividades de investigación, imparte varios cursos relacionados con las finanzas corporativas y los mercados financieros.

Sami Bacha es profesor adjunto de contabilidad y finanzas en la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Gestión de Sousse. Sus intereses de investigación especiales son el gobierno corporativo, la divulgación corporativa, la responsabilidad social corporativa, la elusión fiscal, los riesgos bancarios y la auditoría. Sus principales publicaciones incluyen Bankers, Markets and Investors, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, Corporate Governance, Cogent Economic and Finance, Theoretical Economic Letters, International Journal of Business and Financial Management Research, International Journal of Empirical Finance, entre otras.

Assil Guizani es profesor de Finanzas en la Universidad de Nanterre. Tiene un doctorado. en Finanzas de la Universidad de Nanterre en 2020. Sus intereses de investigación se encuentran principalmente dentro de los determinantes y las consecuencias de la caída del precio de las acciones, el gobierno corporativo, la responsabilidad social corporativa. Ha publicado varios artículos en revistas internacionales arbitradas.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Descriptive statistics

Table 2

Pearson correlation matrix

Table 3

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance

This table reports the OLS and quantile regressions results of the effect of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and year. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 4

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance: Moderating effect of female directors

This table reports the OLS and quantile regressions results of the moderating effect of female directors on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and year. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 5

Alternative measure of CEO overconfidence

This table reports the quantile regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. OC_SZ is the alternative measure of CEO overconfidence. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 6

CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance: Moderating effect of female directors

This table reports the OLS regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance and the moderating effect of female directors on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 7

The tax aggressiveness measure

This table reports the OLS regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax aggressiveness and the moderating effect of female directors on the relation between CEO overconfidence and tax aggressiveness for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 8

GMM regression

This table reports the GMM regression results of the impact of CEO overconfidence on tax avoidance and the moderating effect of female directors on the relationship between CEO overconfidence and tax avoidance for a sample of 1958 firm-year observations. See Appendix A for variables’ definitions. The t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on standard errors clustered by both firm and time. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.