Résumés

Abstract

In the tourism sector, owner-managers have distinct characteristics. SMEs face unique challenges for growth. This study explores the characteristics of Canadian owner-managers of tourism SMEs. We conducted a research based on focus groups and questionnaires. We developed a method of classifying these owner-managers considering their propensity to invest and renew their offerings and the evolution of their firms in terms of profits. A two-step multidimensional cluster analysis gives us six categories of owner-managers: Lifestyles, Procrastinators, Harvesters, Gamblers, Strugglers, and Performers. We explain these categories and discuss recommendations.

Keywords:

- taxonomy,

- owner-managers,

- tourism SMEs

Résumé

Dans le secteur du tourisme, les dirigeants-propriétaires ont des caractéristiques distinctives et leurs PME font face à des défis uniques. À partir de focus-groups et de questionnaires, nous explorons les caractéristiques des dirigeants-propriétaires canadiens de PME touristiques. Nous avons développé une méthode pour classer les dirigeants-propriétaires basée sur leur propension à investir et à renouveler leurs offres; ainsi que sur l’évolution de leurs bénéfices. L’application du two-step multidimensional cluster analysis a fait émerger six catégories de dirigeants-propriétaires: Style-de-vie, Procrastinateurs, Moissonneurs, Parieurs, Batailleurs, et Performants. Nous analysons ces catégories et proposons des recommandations.

Mots-clés :

- taxonomie,

- dirigeants-propriétaires,

- PME touristiques

Resumen

En el sector turístico, los dirigentes-propietarios tienen características distintivas y sus Pymes se enfrentan con desafíos únicos para crecer. Realizando focus-goups y aplicando cuestionarios, este artículo explora las características de los dirigentes-propietarios canadienses de Pymes turísticas. Se desarrolló un nuevo y práctico método para clasificar los dirigentes-propietarios basado en su propensión a invertir y a renovar la oferta; así como en la evolución de sus empresas en términos beneficios. Aplicando el two-step multidimensional cluster analysis se dentificaron seis categorías de dirigentes-propietarios: Estilo-de-vida, Procrastinadores, Cosechadores, Apostadores, Luchadores, y Alto-rendimiento. En el artículo se analizan las categorías y se discuten algunas recomendaciones.

Palabras clave:

- taxonomía,

- dirigentes-propietarios,

- Pymes turísticas

Corps de l’article

Tourism is an important industry in terms of its direct and indirect contributions to GDP. This sector generated 9.8% of global GDP (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2016). With its growth of 2.8%, it has outpaced that of the global economy (2.3%) since 2010. Its economic development, significant social benefits and spillover effects has been highlighted by several authors (Chou, 2013; Kokkranikal and Morrison, 2011; Proenca and Soukiazis, 2008). In this sector, SMEs are the most common type of businesses (King, Breen and Whitelaw, 2014), but research on tourism SMEs (T-SMEs) is limited (Morrison, Carlsen, and Weber, 2010; Thomas, Shaw, and Page, 2011), and this is especially true for T-SME owner-managers in Canada (Getz, Carlsen, and Morrison, 2004).

Tourism activities play an important role in the Canadian economy (Bédard-Maltais, 2015), account for approximately 9% of overall GDP and provide over 1.6 million (9.1%) of jobs in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2012). Currently, 99.9% of Canadian tourism businesses are SMEs, 98% of these have fewer than 100 employees (Bédard-Maltais, 2015). Quebec accounts for 25% of the T-SMEs. That said, there is still no common definition among federal and provincial agencies for a T-SME (Canadian Tourism Council, 2014). Even in the literature, there is a debate about the definitions of the T-SME (Morrison, Rimmington and Williams, 1999; Thomas et al., 2011).

In this research, we use Pierce’s (2011, p. 2) definition, i.e., an SME is “a business with fewer than 500 employees and less than $50 million in annual revenues.” Tourism SMEs are businesses that meet above SME criteria and operate in the tourism industry (Accommodation, Transportation, Travel Services, Food and Beverage Services, Recreation and Entertainment)”. SMEs’ characteristics include the centralization of management decisions, a low level of labor specialization, and having an informal, implicit, even intuitive, short-term strategy (Julien, 1994 and 1998, Torrès, 2004a). T-SMEs are particularly influenced by the lifestyle (Shaw and Williams, 2004) and values (Di Domenico, 2005) of their owner-manager. These managers look for utility maximization based on a compromise between quality of life and income goals (Dewhurst and Horobin, 1998).

Canadian T-SMEs differ from other SMEs (Pierce, 2011) as they are more likely to innovate with products, tend to be younger and more growth-oriented, have higher growth rates than other types of SME (Bédard-Maltais, 2015), and yet have lower than average profit margins due to higher expenses. Importantly they engage in international business by making foreigners spend in Canada, fostering cross-border labor flows, innovation, and growth (Cohen, 1988; Hovhannisyan and Keller, 2015; Page and Getz, 1997), and helping deal with the pressures of globalization (Croes, 2010; Sinclair-Maragh, and Gursoy, 2015; Temiz and Gökmen, 2014).

However, T-SMEs face difficulties in financing, being perceived as riskier than SMEs in other industries (Pierce, 2011). Obtaining financing thus is an obstacle to improving, modernizing, and expanding operations for these firms. Until recently, little attention has been paid to T-SMEs’ growth (Bridge and O’Neill, 2008; Shaw and Williams 2004). However, seeing T-SMEs “as the economic lifeblood of the sector” (Čivre, Gomezelj Omerzel, 2015, p. 324), policy-makers have turned their attention to this sector.

Hence, while investigating the T-SME owner-managers, we analyzed the growth potential and sustainability of their companies, and examined the complexity of their investments, innovativeness and use of external funding, and their perceived economic performance. These analyses provided the framework by which owner-managers were classified in this research. Our taxonomy is based on a study conducted in the province of Québec. Our paper is structured as follows. The first section presents the theoretical framework as well as some existing taxonomies and typologies of T-SMEs. The second section covers the methods used to collect data and explains how the six specific T-SME clusters were identified. The third section describes the six T-SME clusters and discusses our proposal in relation to some existing theories. The final section presents our conclusions and the limitations of this study.

Literature Review

Classifications (i.e., “ordering entities into groups or classes by their similarities”, Bailey, 1994) aid in our understanding of how the world works, in identifying its mechanisms, in explaining evolutions, and lastly, in making predictions. The two main types of classifications used are: 1) typologies, top-down, theory-driven classifications, and 2) taxonomies, bottom-up, data-driven classifications. Typologies describe ideal types representing unique combinations of elements’ attributes (Doty and Glick, 1994). They require validation against empirical data. Taxonomies attempt to separate elements of a group into subgroups to come up with an exclusive subgroup using “a series of hierarchically nested decision rules” (Doty and Glick, 1994, p. 232), and including all possibilities when taken together. They must be simple and easy to use (Stewart, 2007). Classification categories used for the various SME processes include the internalization of small firms (Aspelund and Moen, 2005), the basics for the technologies developed, the performance or origin of the start-up and how it affects firm growth and size (Birley and Westhead, 1994), commercialization (Libaers, Hicks and Porter, 2010), and the operational strategies employed (Sum, Kow and Chen, 2004).

Identifying the distinguishing characteristics of T-SMEs and their owner-managers, a topic of interest in tourism literature (Heilbrunn, Rozenes, and Vitner, 2011; Koh and Hatten, 2002; Thomas et al., 2011), could help in understanding the motivations of T-SME owner-managers (Haber and Reichel, 2007; Thomas et al., 2011). Therefore, while T-SME founders or owner-managers are complex individuals with varied goals and purposes (Getz et al., 2004), it is both important and possible to characterize them based on a limited set of criteria. Owners, managers, entrepreneurs, and policymakers can then use these classifications to understand the relevant companies’ needs, dynamics, and requirements for growth. Relevant data can also help in international comparisons.

As SME literature is abundant in classifications, an exhaustive inventory is outside the scope of this paper. There exist several typologies, specifically for tourism entrepreneurs, (i.e. Getz and Petersen, 2005), which identifies lifestyle entrepreneurs and growth- oriented entrepreneurs. Hence, we have taken this as our starting point. Additionally, we looked at classifications of tourism entrepreneurs with respect to certain characteristics of the tourism sector, and more generally, the service sector.

Many authors (Getz et al., 2004; Koh and Hatten, 2002; Li, 2008; Thomas et al., 2011) argue that tourism start-ups are different from non-tourism enterprises because “most touristic offerings are intangible: tourism entrepreneurs, therefore, experience greater difficulty in testing their offerings before launch (concept testing versus product testing)” (Koh and Hatten, 2002, p. 32). Additionally, they have “higher service content” than goods-selling companies. They are also highly affected by seasonality. Finally, tourism entrepreneurs face greater uncertainty because the buyers must come to the seller’s territory.

Literature on T-SMEs has highlighted the role of lifestyle as a motivator for owner-managers in establishing a business (Peters and Schuckert, 2014; Uysal, Sirgy, Woo, and Kim, 2016). Getz, Calsen and Morrison (2004) state that “what is unique about the tourism and hospitality industry is that it has held consistently solid appeal to those individuals seeking to combine lifestyle, domestic and commercial activity” (p. 29). Lifestyle motivations predominate in this sector (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Lashley and Rowson, 2010; Mottiar, 2007; Peters and Schuckert, 2014). Consequently, the ‘lifestyle business’ concept has garnered attention in tourism and hospitality literature (Peters, Frehse, and Buhalis, 2009; Thomas et al., 2011; Peters and Schuckert, 2014). The tourism sector is particularly appealing to individuals previously described because of its relatively low entry barriers, its capacity to accommodate the family, the fact that it lends itself to lifestyle business models (Carlsen, Morrison, and Weber, 2008; Peters and Schuckert, 2014), and that it offers business venture opportunities in attractive locations (Getz and Carlsen, 2005). Even if it is a “fuzzy” notion (Markusen, 1999), owner-managers with these motivations place more importance on achieving a certain lifestyle than on achieving monetary objectives (Morrison and Teixeira, 2004). Accordingly, they do not sacrifice their main objective, that is, maintaining their lifestyle, when making business decisions. Business decisions of these entrepreneurs are not primarily driven by an economic focus, and as such, economic well-being cannot be the main component of the interpretative schema of this type of owner-manager (Maitlis and Christianson, 2014). Dewhurst and Horobin (1998) advance that a “lifestyler” is more of a consumer than a producer, that is, success for them is reflected in their quality of life. Shaw and Williams (2004) disagree with this idea. They state that “lifestylers” could lead professional companies within a particular lifestyle framework. Notwithstanding the weight of lifestyle in their motivation, owner-managers still need to adopt and maintain sound business principles to some degree in order to avoid bankruptcy and closure even though for many of them viability comes second to lifestyle aspirations.

Bredvold and Skålén (2016) provide a deeper analysis in their classification of lifestyle tourism entrepreneurs. They disagree with the “uniform conceptualization” of these entrepreneurs based on a narrative understanding of their identity. They propose two axes of “identity construction”, on one end, they place “social and culturally embedded” and “independent”; on the other end, they place “flexible” and “stable”. Using these elements, they identified four types of lifestyle entrepreneurs (see more details in Table 1).

Koh and Hatten (2002) state that “the tourism entrepreneur may be defined as a creator of a touristic enterprise motivated by monetary and/or non-monetary reasons to pursue a perceived market opportunity legally, marginally, or illegally.... he also believes he has the ability and skills to undertake successfully and is willing to assume all the risks and uncertainties associated with launching and operating a touristic enterprise.” (p. 25). They identified nine different types of entrepreneurs (see more details in Table 1).

Getz, Carlsen, and Morrison (2004) (followed by Morrison in 2008present a typology of “entrepreneur profiles” of owner-managers based on entrepreneurial process and organizational context. For them, the different types “should not be regarded as sterile, static, and divorced from each other, as many overlap and will change and alternate according to respective family and business lifecycles” (Getz et al., 2004, p. 27). They identified ten such ideal types (Table 1).

Ferreira, Azevedo and Cruz (2011) introduced a parsimonious taxonomy of SMEs’ growth in the service sector based on life-cycle theories and the resource-based view (RBV). Five different stages in the T-SME (Table 1) were identified.

These classifications focus on different aspects (see more details on Table 1) of T-SME owner-managers or T-SMEs themselves. However, none of these provide explicit information on the owner-manager’s propensity to invest and renew their offerings, nor about the evolution of their firms in terms of profits.

Methodology

Data

Data used in this study are sourced from qualitative (focus groups) and quantitative research (questionnaire survey conducted by the Ministère du Tourisme du Québec (MdTQ) in collaboration with HEC Montréal and the Centre de Recherches sur l’Opinion Publique (Public Opinion Research Center known as CROP). The purpose of this previous exploratory research was to understand the behaviors of T-SME owner-managers, particularly in relation to investments and funding sources[1]. T-SME financing has its own peculiarities that set it apart from the classical financial theories and methods (St-Pierre and Fadil, 2016).

Interviews with five focus groups[2], consisting 60 owner-managers, were conducted to complement and test the adequacy of the survey. To validate the questionnaire’s clarity, a preliminary focus group was conducted. Four more focus groups were added to enhance data and clarify specific aspects of financing per MdTQ’s requirements. In collaboration with MdTQ, industry representatives, excluding travel agencies and Destination Management Organizations (DMOs), were selected based on their experience and influence within the tourism sector (ski resorts, hotels, parks, spas, river cruisers, festivals, outfitters, etc.). Travel agencies and Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) were excluded from the research by the MdTQ. However, respondents have had to answer a question if they asked for help from various development organizations, including DMOs. The tourism firms involved in our research were identified by CROP using the Emploi-Québec (government of Quebec job search agency) and MdTQ’s[3] database. The database was composed of accommodation (hotels, B&B, outfitters, etc.), leisure (parks, hunting and fishing clubs, ski stations, festivals, museums, etc.) and tourism transport companies. Restaurants were excluded due to the inherent difficulty in determining the percentage of tourist versus non-tourist clienteles in restaurant settings. Not-for-profit organizations were excluded since profit evolution is a key element in our analysis. The pilot test results and insight gathered during the first focus group led to further phone interviews with T-SME owner-managers.

The questionnaire contained 60 questions grouped into 5 sections. Section 1 focused on firm profiles. We asked about the businesses’ demographic features such as location, sector, age, and size, as well as economic performance and ownership structure. Tourism firms vary greatly in terms of the number of employees since this depends on fluctuations in demand. (Guzman-Parra, Quintana-García, Benavides-Velasco, and Vila-Oblitas, 2015). The T-SMEs of Quebec are no exception. We found that the number of employees could be up to seven times higher during the high season than in the low season. Consequently, we used Piergiovanni, Santorelli, Klomp, and Thurik’s (2003) method to calculate an estimated average number of employees based on specific survey answers. We multiplied the number of seasonal employees by the number of months in the T-SME’s high season and then divided the resulting number by 12. Finally, respondents’ answers to some questions on the firm’s profile section, (size, location, etc.), were cross-validated against Québec’s business register data[4].

Table 1

Some useful classifications

Section 2 covered funding requests for capital investments during the previous three years. Section 3 looked at the characteristics of the T-SMEs’s investment projects for the following three years including expected financing requirements and type of capital investment envisaged (new buildings, new machinery, site extension or maintenance of the existing). Section 4 focused on the managers’ profiles: age, education level, and previous experience. Finally, section 5 addressed the level of innovativeness of the T-SMEs.

We considered three types of changes to the firm’s offering of service or product: 1) the introduction of new services or products, 2) any kind of improvement to an existing product or service, and 3) the discontinuation of a product or service. We asked respondents whether the strategic change in their offering had occurred over the last three years or if it was an ongoing process. Based on this information, we constructed two indexes to measure the innovation activities of the T-SMEs, the past offering and current offering indexes (see Table 1). An offering index of 1, the lowest value, corresponds to “no new product/services”, “no improvement of an existing products/services”, and “discontinuation of product/services offered”, meaning a diminishing offering and no innovation. An offering index of 8, the highest value, corresponds to a combination of “new product/services”, plus the “improvement of existing products/services” and “no product or service discontinuation,” implying the highest level of innovativeness. For example, firms maintaining an existing offering with no change were assigned a value of 3 (see Table 2).

Table 2

Values assigned for the offering indexes (innovativeness) of a firm[5]

An additional index for the complexity of future investments was developed using both the number of investments and the goal of these investments. It looked at a) maintenance of the current assets and b) acquisition of new assets. A score of 1 was assigned for an investment to repair or replace existing physical (productive) assets, and a score of 2 was assigned for acquisitions of new assets. For two or more similar new investment projects, the score was 4 (maximum). The complexity investments index varies from 0 (if there is no investment) to 6 (if the T-SME has invested in two or more projects to acquire new assets, and for two or more investments for renovation or repair of existing assets). Investments for acquiring new assets were given the highest values, as it was assumed that the owner-managers intended to expand, while the other kind was assumed to be more about the need to maintain productive capacity. Intermediate values (1 to 5) represent different combinations of numbers and types of investment projects.

As all the respondents come from private companies, we could not access detailed financial information. The firms’ economic performances were estimated given the respondents’ self-evaluation of their revenues and profits, namely their evolution over the last three years (growth, stability, or decline).

Descriptive Statistics

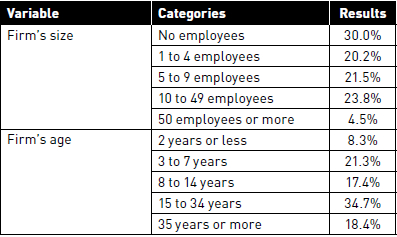

A total of 484 valid responses from owner-managers were retained. The respondents’ main characteristics and the firms’ profiles are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. In our sample, 30% of firms did not have employees, 20.2% had fewer than 5 employees, 21.5% had between 5 and 9 employees, 23.8% had between 10 and 49 employees, and 4.5% had more than 50 employees. These results show that the distribution by firm size within our sample closely matches the Power Law distribution observed in the overall Canadian economy.

Table 3

Profile of Respondents

The average age of respondents was 52. The firms in the sample are relatively small, with average annual sales of CAD 627,000 and less than 10 (8.5) full-time employees, in line with other Canadian SMEs (9.0 employees). If part-time employees are included, the average for T-SMEs increases to 12.5 employees.

Table 4

Profile of Firms

Analysis of Results

A two-step, multidimensional cluster analysis was used to examine the data. First, T-SMEs were classified into five categories using a non-hierarchical method and based on the following variables: 1) the complexity of investments made during the last three years, 2) the complexity of the intended investments for the next three years, 3) changes in the offering of products and/or services either during the last three years or currently, and 4) the recent, perceived evolution in terms of profits. The final number of clusters was determined by the homogeneity within each cluster and by parsimony (Andrews and McNicholas, 2012). Second, since there is a difference in attitude towards the growth of micro-firms compared to larger firms (Delmar and Wiklund, 2008), the largest cluster was further divided into two: 1) SMEs with fwer than 5 employees and 2) SMEs with 5 or more employees.

Using a k-means clustering method, we identified six T-SME clusters: 1) lifestylers, 2) procrastinators, 3) harvesters, 4) gamblers, 5) strugglers, and 6) performers (see Table 5).

For some key elements, differences between the groups are revealed through their standardized values. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 5

Main Characteristics of the Six T-SME Clusters

Cluster 1: Lifestylers

A representative example is a 65-year old woman owning a B&B (in a peripheral area) for the last 20 years, earning CAD 20,000, having no employees, no recent or planned investment nor changes in offering. The enterprise is open all year round. Lifestylers are also found in other sectors, such as leisure, but they are difficult to be found in the transportation sector.

This type of entrepreneurs focus on the convergence of their customers’ needs and their own: “In my case, I created this company to please nature lovers and to please myself. I share with my customers a love of nature. I often accompany them on their walks… I’m not interested in growth because I don’t want to spend more time on management issues and enjoy nature less” (outfitter owner). These owner-managers do not prioritize growth and focus more on their value proposition than on acquiring customers: “We’ve been providing the same service for a long time; I don’t see why I should change anything. If there are fewer tourists, it is because the government has not done enough promotion.” (outfitter owner).

Lifestylers usually have no employees, and if they do, it is usually a family member: “Our company is so little…. My son helps me during the summer because we have more tourists during this period of the year” (tourist attraction owner). In most of the cases (63%), they own micro firms with no employees while the rest have fewer than five employees.

Lifestylers are the second-largest group in our sample at 28%. These owner-managers are, on average, the oldest among all clusters (56 years). Despite being the oldest, their experience in tourism is average (15.6 years). Younger owner-managers are rare in this cluster compared to other clusters, with only 14.5% under 45 years old and 53.4% who are 55 years or older. Most often, average turnover is insufficient to make a living (CAD 52,000 annual average). Two out of three make less than CAD 30,000 a year. We can therefore, surmise that these owner-managers have other sources of livelihood (retirement pension, part-time job, etc.). Among them, 58.5% have earned some stability with their revenues. They seem to be satisfied with the size and revenues of their firms.

FIGURE 1

Standardized averages for key elements of each cluster

“After my retirement, I set up my business. I always wanted to live in Gaspésie. My wife deals with the kitchen and receives the customers and I do the management. Our revenues change according to the seasons, but the annual result is almost the same each year. The company size suits us at present; we do not have large investment projects to come (B&B owner).

The rest of the lifestylers (41.5%) face a decline in revenues and profits but are neither implementing nor planning new investments to offset this decline. They privilege other aspects that enhance their quality of life even when facing problems related to their long-term economic survival: “I really like the things that I do. If my incomes decrease, I will try to improve my offer, to look for new customers or, in the worst case, I will try to adapt myself,” (tourist attraction owner). These firms have the lowest productivity (as measured by turnover divided by the average number of employees).

Lifestylers who have made investments during the last three years (37.8%) are in the minority and only a quarter seek external financing (25.9%). Most (80%) do not intend to invest in the next three years. For the remaining 20% who want to invest, the amounts are small (CAD 69,000). As the majority, lifestylers do not show any desire to grow their business, they are the least concerned about financing. Nonetheless, 24.4% of them think these difficulties are an obstacle to growth, a percentage that is higher than the percentage of actual investors in the cluster.

The most common change in their offering of services and products was the improvement of the existing offer. Almost 50% of the relevant firms (42.2%) made no change in their offering of products and services (Index = 3), while 31.9% made minor adjustments (Index = 4). This cluster is the only one where some owner-managers intend to close their business within the next three years. It also has the second-highest percentage of owner-managers intending to sell (22.0%) their business in the next three years. Noticeably, the owner-managers in other clusters consider selling their business as a form of exit.

Lastly, whether linked to operational or dynamic capabilities, business management issues are not a priority for the lifestylers. The relative autarky in which they run their business is illustrated in that only 13.3% of the lifestylers have contacted a development agency over the last three years, and just 3.7% of them have contacted a DMO. This suggests that most of them accept the status quo and do not intend to grow.

Cluster 2: Procrastinators

A representative procrastinator is a 62-years-old owner of a holiday center in an urban area with 13 employees, and has run the firm for the last 40 years. Most procrastinators are in the accommodation (59.6%) and leisure (36%) sectors. They only made minor changes in their offering (improvement) in the last three years and intend to do the same in the next three years. “Our company has been operating for more than 35 years; for 10 years of this period we had no growth, but our current income is still accepTable to us” (hotel owner). Procrastinators own primarily mature and relatively large firms. They are the most experienced (20.8 years in average versus the sample average of 16.4 years. They own the oldest firms in the sample with an average age of 29 years. Around 66% of them have reached a degree of stability in terms of revenues, while the rest are in decline. The main objective of procrastinators appears to be stability rather than growth. They ride out the market’s downturn by minimizing their efforts both in terms of investment and in varying or adapting their offering. “In the last years, our revenues have decreased slowly. We keep that in mind but for the moment, we do not visualize to invest in the short term. We hope that better times are coming,” (hotel owner).

Procrastinators showed the highest intent to sell their firm over the next three years (25% compared to the sample average of 15.8%) signifying their economic fragility. Despite their size and age, less than half (42.7%) of the firms reportedly made investments over the last three years, and the average amount is lower than for the whole sample (CAD 392,000 versus CAD 406,000). Since procrastinators have the second largest share of declining firms, we surmise that they are barely maintaining their financial performance. At best, they may intend to renovate existing assets partially but none of them plan to expand their activities. Similar to lifestylers, the frequency of investment for the next three years (31.5%) is significantly lower than the average (58.3%) and oriented towards maintaining current assets. “If our incomes fall dramatically or the infrastructure is degraded, we will look for financing or subsidies for remodeling” (small hotel owner).

Indeed, more than two out of every five firms in this cluster have failed to make investments over the last three years and have no plans to do so in the next three years. In other words, these firms have not undertaken any type of investment for six years. Among firms that have invested over the last three years, 39.5% sought external funding: “Before looking for bank loans we do our best to finance ourselves” (hotel owner). Meanwhile, the firms that obtained external funding had a high rate of financing approval (80%).

On the offering indexes, procrastinators’ firms have the lowest values, both for the last three years and in terms of ongoing change, thereby reflecting inertia.

The procrastinators are, by far, the most concerned with recruitment issues. Procrastinators perceive the management of the company as a challenge, more so than the average owner-managers of other clusters. However, they were the least likely to ask for help from a development agency (16.9%), and marginally likely to contact a DMO (6.7%).

Cluster 3: Harvesters

This is the largest cluster of firm owners, representing 30.6% of the total. They are distributed evenly within the sample.

A representative harvester is a 54-year-old owner of hunting and fishing recreational services located more in urban and coastal areas, and less in peripheral areas. He has increased his firm’s profitability in the last three years, and invested in the same period, but does not plan to do more or make any changes in his firm’s offer of services:

“We have invested a lot of money in our facilities in the last years, especially to renew infrastructure and the part dedicated to snowboarding. This paid off and allowed us to grow our turnover. It has allowed us to keep our clientele and to reach other customers such as young people who do snowboarding. Also we hired skillful and highly trained people to be instructors” (ski station owner). Most of these firms are 15 to 34 years old. Owner-managers in this cluster have an average seniority of 10.3 years within the firm and 15 years of experience within the sector, both slightly below the sample averages. In terms of employee numbers, these firms are present across all size groupings, with a distribution that is in line with that of the sample.

Most harvesters have been very active in investments over the last three years. However, their intentions for the future do not follow the same trend, likely because they are currently harvesting the fruits of their past investment efforts. Less than half (41.2%) of them have ongoing investment projects and the vast majority have only one ongoing investment project, usually a new asset. As for past investments, they have the second-highest score on the Offering Index (5.91), and on current investments, they are third on the offering index (5.54), a slightly downward trend. An impressive 90.5% of the firms in this cluster have seen their returns increase during the last three years (with 69.6% seeing an increase in profits compared to an average of 28.7% within the total sample). “For four years we have been investing for remodeling and renovating our infrastructures… of course our sales have increased and every year we are acquiring new customers” (recreational service owner). Despite their investments, only 31.1% of them have contacted a development agency over the last three years and as few as 12.7% of them specifically contacted a DMO.

Cluster 4: Gamblers

A typical example of a gambler is a recent and relatively young owner (39 years old) living in an urban area, owning a new hotel-spa, and who started the business two years earlier without previous experience in the field. The owner-managers in this cluster represent only 3.3% of the sample; all their firms are less than eight years old, with most of them being less than three years old. The average respondent was 48 years old and had been leading the firm for an average of 2.4 years at the time of the study. The sector experience of these owner-managers is 5.5 years, including their experience with their current firm, which indicates that a majority of them had undertaken a recent career change. The majority (69.3%) have fewer than five employees. However, the size of their investments over the last three years totaled more than three times the average of the entire study sample. The average annual revenue of this cluster of firms is CAD 170,000, which pales in comparison to their average past investments (Table 5). However, for as many as 69% of these firms, the revenues are growing while the remaining firms demonstrate that they are maintaining their performance in this regard. The firms enjoy relative stability in terms of their offerings. They do not consider access to external funding a problem for growth. This group has the highest percentage of owner-managers who have not changed their offering over the last three years (62.5%), offering the same services and products with which they entered the market. These owner-managers perceive the day-to-day operation of their business as more challenging than its strategic management (newness liability): “Unhappily I don’t have time enough for thinking about new business opportunities or looking for new clients. The day-to-day operations of the business absorb all my working time” (recent hotel owner).

This cluster includes the highest share of owner-managers with university degrees (50%), and of owner-managers actively seeking help from development agencies (56.3%), which is more than twice the sample average (26.4%). However, contacting a DMO is less frequent (18.7%) for these owner-managers.

Cluster 5: Strugglers

A representative struggler owns an equestrian center (leisure sector) in a coastal area is 48 years old and has a longer-than-average experience (19 years) in tourism. This owner has made significant investments in the last three years and he will double them in the next three years, most likely hoping to reverse the trend of declining profits.

These owner-managers show the most contrasting elements of performance. They usually own mature firms (24.9 years), of greater than average size (18.2 employees), even if they are smaller than those of performers or procrastinators, but their economic performance is modest. Their firms are at a turning point in their lifecycle. They have invested heavily in the past years and intend to continue at this high level for the next three years. The decrease (or, the stagnation) in earnings and profits they have experienced could be the reason they are investing: “We are conscious that the sales are declining, to compensate for that we are investing in offering new services and we are always listening to our customer advice to improve the existing offer. Also, we empower our employees to make decisions fast to satisfy our customer’s needs” (leisure company owner). It is unclear whether their ongoing investments will help them kick-start new growth; however, the high level of investment indicates a good measure of proactivity and further shows that owner-managers are risk-takers. It is noTable that every firm in this cluster had at least one ongoing investment project, and the complexity of these investments obtained the highest scores possible. Indeed, firms in this cluster have been the most active in terms of size of investment over the last three years (average of CAD 763,000). Most of their funding is internal, with only 30% coming from external sources: “We don’t like to use banking loans, until now we have tried to use our own money. We try to maintain our installations and to modernize them where possible,” (hotel owner). Their higher level of investment, both present and future, is associated with a higher than average score on the offering indexes (which is nevertheless lower than those of performers). The firms in this cluster are not only offering new products and services, but also improving their existing products and services. From the owner-managers in this cluster, 35.8% are actively seeking help from development agencies, and 21% contacted DMOs (ranking second place).

Notably, owners in this cluster showed the highest dependency on non-domestic clientele, which may be an explanation for their lower recent performance given the impact of the 2008-2009 crisis outside of Canada.

Cluster 6: Performers

The representative performer is a tour operator (belonging to the accommodation or leisure industry), located in a coastal area, who is 54 years old and who became an owner of an existing firm 10 years ago. On average, performers have seven years’ experience in the firm that is 22.4 years old, meaning that in average, a SME was owned by someone else in its first 15 years of existence. Meanwhile, the average age of these current owner-managers is 43 years, the youngest among all clusters.

Prior investment was more than 10% of turnover and additional investment is planned for the next three years; turnover and profit were growing. The owner-managers in this cluster have continually also improved their offerings:

“I have been in this business for a long time and I am always looking to innovate, for me and for the clients – they are not all from Quebec but also Americans or from the rest of Canada. I am convinced that if we innovate, if our facilities are top, if we have excellent service there will always be customers for us. Since the foundation of our spa, we have not stopped offering new services and growing. We have a long-term strategic plan to continue growing” (spa resort owner).

In terms of employees, the average size of these firms is the largest at 22 employees while their average revenue (CAD 1,061,000) place them second, very close to the average revenues of the strugglers. Nearly all of the firms have had an increase in revenues and profits over the last three years. Without exception, the owners of firms in this cluster have invested over the last three years and have requested external funding. Nonetheless, the average amount of investments made over the last three years was under the sample average (CAD 337,000 compared to CAD 406,000). However, the investments planned for the next three years were larger than the average (CAD 580,000). These firms have several concurrent investment projects (2.8 projects per firm), implying both an extension and improvement of their current assets, and thereby of their offering of products and services. These firms also show the highest dynamic in terms of offering renewal.

Despite their recourse to external funding described above, owner-managers in this cluster perceive access to funding as a real obstacle to growth, implying they are “hungry” for more: “I really want to grow my company but it is so difficult to have a loan adapted to our needs and capacity to pay. I think the banks do not understand our sector. We need to invest in more infrastructure, vehicles and specialized employees,” (tour operator).

Firms in this cluster have sought more external advice and counseling than the rest of the sample (73% to an average of 26.4%), and they contacted the DMO the most often (46.7% to an average of 11.2%). They scored higher than the sample average in terms of perceived managerial challenges and scored relatively low in terms of recruitment and management capabilities. The owner-managers of these firms may have good control over the firm’s day-to-day operations but perceive growth as more challenging. Among these owners, 40% have a university degree. Almost all intend to remain at the helm of the firm for the next three years.

Discussion

According to Getz and Petersen (2005), lifestyle is a dominant factor in understanding the make-up of firms in the cluster we have named lifestylers (Cluster 1). Since the average return is not enough for lifestylers to make a living, achieving a certain degree of independence is likely the reason they strive to become lifestyle entrepreneurs (Peters et al., 2009), as in achieving a certain quality of life (Morrison et al., 1999). Lifestyle is an important motivator for these owner-managers to establish a business (Peters and Schuckert, 2014; Uysal et al., 2016). Getz, Calsen and Morrison (2004) put forward that it is tourism itself rather than the business of tourism, which offers an environment that corresponds to the non-economic motivations of these owner-managers (Dewhurst and Horobin, 1998; Shaw and Williams, 2004). Based on our findings we agree with Morrison and Teixeira (2004) that owner-managers of this type place more importance on achieving a certain lifestyle than on business goals. Their business decisions do not seem primarily driven by financial considerations. The main aim of these owner-managers is maintaining their lifestyle (Koh and Hatten, 2002; Getz et al., 2004). Lower levels of satisficing criteria (Simon, 1959; Smith, 2014) might explain their low level of investments or renewal of their offerings despite a decline in revenues. They also have the highest average age of owner-managers (highest share of owners aged 65 and over) in the sample. This may explain their lower propensity to assume risky investments, as well as infrastructure investments that require amortization periods longer than the expected life span of the firm. This also suggests that they are, often, “bridge entrepreneurs” (Singh and DeNoble, 2003). We may reasonably argue that firms in this cluster have the smallest likelihood to change their dynamics and future. Nevertheless, firms in this cluster have their role in the economy, permitting their owner-managers to maintain a reasonable quality of life instead of pressurizing the social safety net.

Procrastinators appear to face many difficulties to keep their businesses afloat. Many of them show more than one sign of the “shadow of death” effect (Griliches and Ragev, 1995) namely low investments, lack of renewal of their offering, self-centered activity, low productivity, and declining profits.

Though their prospects are not favorable, these owner-managers do not intend, for the most part, to shut down the firm, at least not within the next three years. The considerable experience of these owner-managers could explain their good, old-fashioned management practices, and certain obstacles to renewal. As they do not plan change, they seem close to the “Loyal” type identified by Bredvold and Skalen (2016), being true to tradition. They also show traits attributed to “Maturity” and “Decline” categories of the Ferreira, Azevedo and Cruz (2011) taxonomy.

Their strategies fall in line with the “conservative” ones defined by Covin, Slevin, and Covin (1990) in describing risk-averse and non-innovative firms. However, the third characteristic defined by Covin et al., (1990), reactivity, is not observed in the firms in this cluster. Instead, the owner-managers appear to be waiting out developments rather than initiating change in reaction to developments in the market. Here, we specifically refer to both the lower propensity to ask for support from development agencies and the fact that the majority does not consider access to funding as a major problem to growth. Finally, the owner-managers of these firms may be stuck in their course of action (DeTienne, Shepherd, and De Castro, 2008; Ucbasaran, Shepherd, Lockett and Lyon, 2013). It seems that most of these experienced owners are caught in a once-successful business (original imprinting, Stinchcombe, 1965), for which they are now unable to obtain a better perspective. A radical change in management could be the only solution to revive these firms.

The firms in Cluster 3 (harvesters) have made lots of effort in the recent past, and while they do not intend to continue with new investments or changes in their offering, they are currently reaping the fruits of their past labors. Such behavior highlights the need for a certain period of time in order to achieve the expected results of costly and risky investments. It also suggests that some firms may be following cyclical trajectories. With a relatively high average age, most harvester firms have overcome the liabilities of newness (Jennings, Greenwood, Lounsbury and Suddaby, 2013) and adolescence (Bruderl and Schussler, 1990), and given their average size, their actual growth phase necessarily follows a previous period of stagnation. Their recent growth trajectories may be of the kind identified by Brush, Ceru, and Blackburn (2009), that is, “episodic growth” or “incremental growth”. They are clearly growth-oriented (using the typology of Getz and Petersen, 2005), while their companies could be either in the “Expansion” or “Maturity” categories of Ferreira et al. (2011) taxonomy.

Cluster 4 (gamblers) is composed of owner-managers of very young and relatively small firms (start-ups). They bet on increasing sales, actual or future, through aggressive initial investment policies. Gamblers made important investments when starting the firm, and those seeking to continue in this direction have major projects in mind, with earmarked investment amounts that are considerably higher than their actual return. This suggests a long-term view and a pro-active, entrepreneurial orientation. Their firms’ offerings seem to be currently stable, and they have few intentions to improve them. These sTable offerings indicate that these owners are waiting for the market to validate their original business model. This category is quite similar to the “nascent” entrepreneurs’ type identified by Koh and Hatten (2002) and the owners of “birth” firms in the taxonomy of Ferreira et al. (2011). They are clearly similar to the “growth-oriented” type, according to Getz and Petersen (2005).

Performers and strugglers (clusters 5 and 6) are both proactively looking for new opportunities and sources of funding and are willing to take moderate investment risks but differ substantially regarding their previous years’ performance. Owner-managers who are not prepared to adapt their strategy, or change their mix of existing products and services, are more likely to become obsolete (Carlisle, Kunc, Jones and Tiffin, 2013; Mok, Sparks and Kadampully, 2013). These clusters are closest to the “prospector” type from the typology elaborated by Miles and Snow (1978), or the “entrepreneurial” type elaborated by Mintzberg (1973), showing the highest levels of offering renewal and levels of investment. The owner-managers of these two clusters are the most unsatisfied with accessibility to external funding, which may indirectly signal their wish to maintain their growth path (performers) or to reverse their declining one (strugglers). While the performers are the strongest, the strugglers are below par in terms of performance. Thus, their motivations to invest and renew their offerings may differ substantially. Performers are clearly of the “Growth-oriented” type (Getz and Petersen, 2005) and they belong to the ‘Diversification” category in the taxonomy of Ferreira et al. (2011). While the strugglers are also of “Growth-oriented” type (Getz and Petersen, 2005), they mix the traits of both “Maturity” and “Decline” clusters in the Ferreira et al. (2011) taxonomy.

Overall, the owner-manager’s age and seniority in these firms seem to play an important, indirect role in the clusters’ composition, as the older owner-managers are more likely to be a lifestyler or a procrastinator. They may adopt different strategies due to their awareness of their shorter life expectancy.

DMOs

While DMOs were not included as a focus of this study, as mentioned in the Methodology section, in the questionnaire, they are listed among the organizations to which T-SME may ask for help. While only 26.4% of the respondents asked for help from external organizations, those specifically addressing DMOs were even fewer, with an average of 11.2%. Performers were the (positive) exception: of the 73% who asked for external support, 46.7% specifically contacted DMOs. Therefore, we can assume that there is a virtuous relationship here between the higher value for the performers and their propensity to ask for support from development agencies in general and from DMOs, which are promoters of the tourism to a destination concept (Getz, 2008; Getz and Page, 2016). In contrast, the owner-managers who were reluctant to ask for help, especially from DMOs, had the worst performance. They could potentially have benefitted from DMO services but seemed to accept the status quo (lifestylers and procrastinators). Lastly, Komppula (2014) states that the DMO’s roles in the models of destination competitiveness are overemphasized and that the role of entrepreneurs is underestimated. With these points in mind, additional questions emerge, that is: What is the real benefit that T-SME owner-managers obtain from development agencies and in particular from DMOs? What is the impact on the performer owner-managers’ results of the support given by development agencies and in particular by DMOs? What could result from strengthening the relationship between T-SMEs and DMOs? What could be done to improve this relationship? Whose responsibility is it to do so?

Proximities

Most of the T-SMEs in the sample have fewer than 50 employees (95.6%), which is similar to the distribution found throughout the Canadian economy. Therefore, the proximity principle (Torrès, 1999; 2004a; 2004b) implicitly applies to them, not only because of their small size (spatial proximity), but also because their owners mobilize different types of “proximities” as a federating mechanism to manage them (Torrès, 2004a). As previously observed (Torrès, 1999), there is a mix of proximities. This mix includes hierarchical proximity (centralized management), intrafunctional proximity (high integration of the SME functions and polyvalence of the owner-managers and their collaborators), information systems proximity (low complexity of the internal and external information systems based on closeness), temporal proximity (flexible, and implicitly short-term strategy privileged), and proximity capital (personal and family resources, and business network financing).

Regarding the hierarchical and intrafunctional proximities, our sample has an average firm size that is similar to other sectors. Therefore, we expect that T-SME owner-managers concentrate decisional power. However, we realize that the companies which are investing and innovating the most (e.g. performers and strugglers) have a more complex hierarchical structure. Others struggle to cope with day-to-day operations (e.g. gamblers), which is an issue that is not necessarily related to the size of the T-SME (procrastinators). For future research, it is interesting to find out if these T-SMEs are keeping this intrafunctional proximity out of choice or because they do not know how to do things differently.

With regard to information systems proximity, similar to hierarchical proximity, the spatial closeness related to the size of the firms leads us to expect that the owner-managers would prefer direct, flexible, and informal internal information systems. However, for external information systems proximity, our results show that three clusters, each with a different average firm size (gamblers, strugglers and performers), are not restricted to serving only local customers. We note as well that only one of them (performers) uses DMO support frequently. A new avenue for research could therefore be to investigate how these owner-managers reach their international customers (i.e., distant markets). Contrary to Torrès’ theory (1999; 2004a; 2004b), our results show that half of the clusters do not seem to be aligned with temporal proximity. The clusters investing and innovating the most (performers, gamblers and strugglers) have structured plans. They do not limit themselves to short-term strategies.

The majority of the owner-managers (except performers and gamblers) have expressed their preference for self-financing or patient investment instead of bank loans. Performers point out that the bank’s loans are not well adapted to the tourism sector.

Finally, performers do not generally follow the principle of the proximity mix. This implies that T-SMEs could be different from other sectors’ SMEs, at least from the proximity theory point of view. To be certain, a comparative study, as well as a more detailed sector study, would be necessary. Referring back to Torrès (2004a), two questions emerge. Do the effects of proximity play a specific role in the tourism sector? How do high-performing T-SMEs manage proximities mix?

Conclusion

Literature in tourism evolves quickly; however, the existing published research on the characteristics of T-SME owner-managers is insufficient, especially on the dynamics of their companies. In this study, we aim to propose a novel and practical framework for classifying owner-managers based on their recent and current propensity to invest and innovate as well as their recent economic performance. We identified six main categories: lifestylers, procrastinators, harvesters, gamblers, strugglers and performers. Some of these clusters (categories) have no equivalent in prior published classifications, while some are close (but not identical) to existing classifications. The proposed categories were explained and findings within each category were discussed to contribute to the current understanding of T-SMEs in Canada.

As a basis for evaluation, the different clusters identified in this study could prove useful for management practitioners, especially those working for DMOs, and policy makers. The taxonomy proposed can help identify the T-SMEs requiring differentiated support, and more importantly, those who are most likely to benefit from support from a societal standpoint.

Other Research Avenues and Limitations

Our analyses suggest that longitudinal research could be used to verify if the performance trajectory of T-SMEs follows economic cycles, with periods of growth, plateau periods (when they harvest the results of their past efforts), and periods of decline. We observed that successful owners include those able to shorten their firms’ periods of decline by offering new sets of products and services. They achieved this through the proactive development and synchronization of overall strategy, effective use of available resources, and an immediate response to the evolution of the market. The inability to synchronize these elements could lead to the failure of a firm, particularly for firms unable to foresee the market’s evolution and adapt their strategy. Future research could also focus on comparing Canadian T-SMEs to other countries.

A significant limitation of this study relates to its cross-sectional nature. As suggested, a longitudinal study may find support for (or disprove) the idea that some firms follow a sinusoidal trajectory in their lifecycle with a length of a cycle that is greater than 6 years; and that some of the clusters identified here (harvesters and strugglers) are specific to different phases within the firms’ lifecycle. Another limitation concerns the size of valid sample, which increases the margin of error. Notwithstanding this, with respect to gamblers, the lower share of firms in the cluster is not a problem per se, even in the tertiary sector, since economic studies and statistics show that few new entrants have the capabilities to survive in the early years of their lifecycle.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Mihai Ibanescu, PhD, is research fellow at the Institute for Entrepreneurship National Bank | HEC Montreal, Canada. He published several book chapters on SME growth and macroeconomics, articles on innovation management, entrepreneurship and family business, and he presented his research in various international conferences on management and economics. He is the main author of the latest editions of the yearly Quebec Index of Entrepreneurship. His current research interest focuses on various aspects of entrepreneurship. He is recipient of prizes for his research activity.

Gabriel M. Chiriță: PhD in strategy and entrepreneurship from HEC Montréal, Gabriel M. Chiriță is professor of management and strategy at UQAR. He practiced for several years as a lawyer specializing in tax and commercial legal matters, which allowed him to become familiar with the stakes of the business world. His research focuses on three areas: (1) strengthening the innovation capacities of large enterprises through the business incubators they set up, (2) business model innovation, (3) the emergence of entrepreneurial intentions and hybrid entrepreneurship.

Christian Keen, PhD, is a senior research at Desautels Faculty of Management, McGill University and a consultant. Christian has an extensive research and working experience in emerging and developed economies. His professional experience includes been a member of several the Board of Directors of private companies and NGOs. He teaches MBA and executives courses in entrepreneurship, international business and strategy. Christian is member of the editorial board of the Journal of International Entrepreneurship and International Journal of Entrepreneurship Small Business. He has published and presented his research in several international conferences.

Luis Cisneros is an associate professor of the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Department, and scientific director of the Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial acquisition and Business Families Hub at HEC Montréal (Canada). His research interests focus on entrepreneurship, small business, business modeling and family business. Luis Cisneros holds a doctorate in management (Group HEC Paris, France).

Notes

-

[1]

A descriptive analysis was conducted by CROP and given to MdTQ and HEC Montréal

-

[2]

The length of the focus groups sessions was 120 minutes on average

-

[3]

Database of the Établissement d’hébergement touristique

-

[4]

Registraire des enterprises du Québec

-

[5]

Based on the answers provided to the three questions related to the changes in the offering. This table presents all the possible numeric values for the offering index (both past and current)

Bibliography

- Andrews, J. L.; McNicholas, P. D. (2012). “Model-based clustering, classification, and discriminant analysis via mixtures of multivariate t-distributions”, Statistics and Computing, Vol. 22, Nº 5, p. 1021-1029.

- Aspelund, A.; Moen, O. (2005). “Small International Firms: Typology, Performance and Implications”, Management International Review, Vol. 45, Nº 3, p. 37-57.

- Bailey, K. D. (1994). Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classification Theories, Thousand Oaks: Sage, 90 p.

- Bédard-Maltais, P. O. (2015). “SME Profile: Tourism Industries in Canada”, Industry Canada, Retrieved July 23, 2016, from www.ic.gc.ca.

- Birley, S.; Westhead, P. (1994). “A Taxonomy of Business Start-up reasons and their Impact on Firm Growth and Size”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 9. Nº 1, p. 7-31.

- Bredvold, R.; Skalen, P. (2016). “Lifestyle entrepreneurs and their identity construction: A study of the tourism industry”, Tourism Management, Vol. 56, p. 96-105.

- Bridge, S.; O’Neill, K. (2008). Understanding enterprise, entrepreneurship and small business (3rd ed.). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bruderl, J.; Schussler; R. F. (1990). “Organizational mortality: The liabilities of newness and adolescence”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 39, Nº 4, p. 530-547.

- Brush, C. G.; Ceru, D.J.; Blackburn, R. (2009). “Pathways to entrepreneurial growth: The influence of management, marketing, and money”, Business Horizons, Vol. 52, Nº 5, p. 481-491.

- Canadian Tourism Commission. (2014). Tourism as Canada’s Engine for Growth: 2014-2018 Corporate Plan Summary,https://www.destinationcanada.com/sites/default/files/archive/2014-01-01AboutUs_Publications_CorporatePlanSummary_2014-2018_EN.pdf

- Carlisle, S.; Kunc, M.; Jones, E.; Tiffin, S. (2013). “Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa”, Tourism Management, Vol. 35, p. 3559-3569.

- Carlsen, J.; Morrison, A.; Weber, P. (2008). “Lifestyle Oriented Small Tourism Firms”, Tourism Recreation Research, Vol. 33, Nº 3, p. 255-263

- Chou, M. C. (2013). “Does tourism development promote economic growth in transition countries? A panel data analysis”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 33, Issue C, p. 226-232.

- Čivre, Ž.; Gomezelj Omerzel, D. (2015). “The behaviour of tourism firms in the area of innovativeness”, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, Vol. 28. No 1, p. 312-330.

- Cohen, E. (1988). “Tourism and aids in Thailand”. Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 15 Nº 4, p. 467-486.

- Covin, J. G.; Slevin, D. P.; Covin, T. J. (1990). “Content and Performance of Growth-Seeking strategies: A Comparison of Small Firms in High- and Low-Technology Industries”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 5, Nº 6, p. 391-412.

- Croes, R. (2010). “Measuring and explaining competitiveness in the context of small island destinations”, Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 50, Nº 4, p. 431-442.

- Delmar, F.; Wiklund, J. (2008). “The Effect of Small Business Managers’ Growth Motivation on Firm Growth: A Longitudinal Study”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 32, Nº 3, p. 437-457.

- DeTienne, D. R.; Shepherd; D. A.; De Castro, J. O. (2008). “The fallacy of “only the strong survive”: The effects of extrinsic motivation on the persistence decisions for underperforming firms”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 23, Nº 5, p. 528-546.

- Dewhurst, P.; Horobin, H. (1998). “Small business owners”. In Thomas, R.(Ed.), The Management of Small Tourism and Hospitality Firms (p. 19-38). Cassell, London.

- Di Domenico, M. (2005). “Producing hospitality, consuming lifestyles: lifestyle entrepreneurship in urban Scotland”. In E. Jones, & C. Haven-Tang (Eds.), Tourism SMEs, service quality and destination competitiveness (pp. 109-122). CABI: Wallingford.

- Doty, D. H.; Glick, W. H. (1994). “Typologies as a Unique Form of Theory Building: Toward Improved Understanding and Modelling”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19, Nº 2, p. 230-251.

- Ferreira, J.J.; Azevedo, S.G.; Cruz, R.P. (2011). “SME growth in the service sector: a taxonomy combining life-cycle and resource-based theories”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 31, Nº 2, p.251-271.

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J.; Morrison A. (2004). The Family Business in Tourism and Hospitality, Cabi Publishing, Cambridge, MA.

- Getz, D.; Petersen, T. (2005). “Growth and profit-oriented entrepreneurship among family business owners in the tourism and hospitality industry”, Hospitality Management, Vol. 24, Nº 2, p. 219-242

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. (2005). “Family Business in Tourism: State of the Art”, Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 32, Nº 1, p. 237-258

- Getz, D. (2008). “Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research”, Tourism Management, Vol. 29, p. 403-428.

- Getz, D.; Page, S. J. (2016). “Progress and prospects for event tourism research”, Tourism Management, Vol. 52, p. 593-631.

- Griliches, Z.; Regev, H. (1995). “Firm productivity in Israeli industry 1979-1988”, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 65, Nº 1, p. 175-203.

- Guzman-Parra, V. F.; Quintana-Garcia, C.; Benavides-Velasco, C. A.; Vila-Oblitas, J. R. (2015). “Trends and seasonal variation of tourist demand in Spain: The role of rural tourism”, Tourism Management Perspectives, Vol. 16, p. 123-128.

- Haber, S.; Reichel, A. (2007). “The cumulative nature of the entrepreneurial process: The contribution of human capital, planning and environment resources to small venture performance”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 22, Nº 1, p. 119-145.

- Heilbrunn, S.; Rozenes, S.; Vitner; G. (2011). “A DEA based taxonomy to map successful SMEs”, International Journal of Business and Social Science, Vol. 2, Nº 2, p. 232-241.

- Hovhannisyan, N.; Keller, W. (2015). “International business travel: an engine of innovation?”, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 20, Nº 1, p. 75-104.

- Ibanescu, M., Cisneros, L., et Chirita, G. (2015). “Une taxonomie des entreprises du secteur du tourisme”, 2ème Conférence de l’Association Francophone de Management du Tourisme (AFMAT), EM Strasbourg, 12 et 13 Mai, Strasbourg, France.

- Jennings, P. D.; Greenwood, R.; Lounsbury, M. D.; Suddaby, R. (2013). “Institutions, entrepreneurs, and communities: A special issue on entrepreneurship”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 28, Nº1, p. 1-9.

- Julien, P.A. (1994). Les PME, bilan et perspectives, Economica: Paris.

- Julien, P.A. (1998). The state of the art in small business and entrepreneurship, Ashgate: Aldershot.

- King, B.; Edward, J. B.; Whitelaw, P. A. (2014). “Hungry for Growth? Small and Medium-sized Tourism Enterprise (SMTE) Business Ambitions, Knowledge Acquisition and Industry Engagement”, International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 16, Nº 3, p. 272-281.

- Koh, K.Y.; Hatten, T.S. (2002) “The Tourism Entrepreneur”, International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, Vol. 3, Nº 1, p. 21-48

- Kokkranikal, J.; Morrison, A. (2011). “Community networks and sustainable livelihoods in tourism: the role of entrepreneurial innovation”, Journal of Tourism Planning and Development, Vol. 8, Nº 2, p. 137-156

- Komppula, R. (2014). “The role of individual entrepreneurs in the development of competitiveness for a rural tourism destination – A case study”, Tourism Management, Vol. 40, p. 361-371.

- Lashley, C.; Rowson, B. (2010). “Lifestyle businesses: Insights into Blackpool’s hotel sector”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 29, Nº 3, p. 511-519

- Li, L. (2008). “A review of entrepreneurship research published in the hospitality and tourism management journals”, Tourism Management, Vol. 29, Nº 5, p. 1013-1022.

- Libaers, D.; Hicks, D.; Porter, A. L. (2010). “A taxonomy of small firm technology commercialization”, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 21, Nº 1, p. 1-35.

- Maitlis, S.; Christianson, M. (2014). “Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward”, The Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 8, Nº 1, p. 57-125.

- Markusen, A. (1999). “Fuzzy concepts, scanty evidence, policy distance: the case for rigour and policy relevance in critical regional studies”, Regional Studies, Vol. 33, Nº 9, p. 869-884.

- Miles, R. E.; Snow, C. C.; Meyer, A. D.; Coleman, H. J. (1978). “Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 3, Nº 3, p. 546-562.

- Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work, Harper & Row New York, NY.

- Mok, C.; Sparks, B.; Kadampully, J. (2013). Service quality management in hospitality, tourism, and leisure. Routledge.

- Morrison, A. (2006). “A contextualisation of entrepreneurship”, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, Vol. 12, Nº 4, p. 192-209

- Morrison, A.; Carlsen, J.; Weber, P. (2010). “Small tourism business research change and evolution”, International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 12, Nº 6, p. 739-749

- Morrison, A.; Rimmington, M.; Williams, C. (1999). Entrepreneurship in the Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure Industries. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

- Morrison, A.; Teixeira, R. (2004). “Small business performance: A tourism sector focus”, Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 11, Nº 2, p. 166-173.

- Mottiar, Z. (2007). “Lifestyle entrepreneurs and spheres of inter-firm relations: The case of Westport, Co Mayo, Ireland”, The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 8, Nº 1, p. 67-74.

- Page, S. J.; Getz, D. (1997). The business of rural tourism: International Perspectives, Boston, MA: International Thomson Business Press

- Peters, M.; Schuckert, M. (2014). “Tourism entrepreneurs’ perception of quality of life: an explorative study”, Tourism Analysis, Vol. 19, Nº 6, p. 731-740

- Peters, M.; Frehse, J.; Buhalis, D. (2009). “The importance of lifestyle entrepreneurship: A conceptual study of the tourism industry”, Pasos, Vol. 7, Nº 3, p. 393-405.

- Pierce, A. (2011). “Small Business. Financing Profiles: Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Tourism Industries”, SME Financing Data Initiative, Canadian Government.

- Piergiovanni, R.; Santarelli, E.; Klomp, L.; Thurik, R. (2003). “Gibrat’s Law and firm size/firm growth relationship in Italian small scale services”, Revue d’Économie Industrielle, Vol. 102, Nº 1, p. 69-82

- Proença, S.; Soukiazis, E. (2008). “Tourism as an Economic Growth Factor: A Case Study for Southern European Countries”, Tourism Economics, Vol. 14, Nº 4, p. 791-806.

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A. (2004). “From Lifestyle Consumption to Lifestyle Production: Changing Patterns of Tourism Entrepreneurship”. In R. Thomas (ed.) Small Firms in Tourism: International Perspectives (p.99-113). Oxford: Elsevier,

- Simon, H. A. (1959). “Theories of decision-making in economics and behavioral science”, American Economic Review, Vol. 49, Nº 3, p. 253-283.

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D. (2015). “Imperialism and tourism: The case of developing island countries”, Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 50, p. 143-158.

- Singh, G.; DeNoble, A, (2003). “Early retirees as the next generation of entrepreneurs”, Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, Vol. 23, Nº 3, p. 207-226

- Smith, S. L. J. (2014) Tourism Analysis: A Handbook, 2nd edition, New York: NY, Routledge.

- Statistics Canada (2012) Provincial-Territorial Human Resource Module of the Tourism Satellite Accounts, Research paper Nº 13-604-M

- Stewart, D. (2007). “(Why) Taxonomies need XML”, EContent, Vol. 30, Nº 2, p. 46-51.

- Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). “Social structure and organizations”. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations, (p. 142-193).Chicago: Rand-McNally.

- St-Pierre, J.; Fadil, N. (2016). “Finance entrepreneuriale et réalité des PME: une enquête internationale sur les connaissances et les pratiques académiques des chercheurs”, Management International, Vol. 20, Nº 2, p. 52-68.

- Sum, C.-C; Kow; L. S; Chen, C.-S. (2004). “A taxonomy of operations strategies of high performing small and medium enterprises in Singapore”, International Journal of Operations & Product Management, Vol. 24, Nº 3, p. 321-345.

- Thomas, R.; Shaw, G.; Page, S. J. (2011). “Understanding small firms in tourism: A Perspective on Research Trends and Challenges”, Tourism Management, Vol. 32, Nº 5, p. 963-976.

- Torrès. O. (1999). Les PME, Editions Flammarion, Collection DOMINOS, 128 p.

- Torrès, O. (2004a). “The SME concept of Pierre-André Julien: an analysis in terms of proximity”, Piccola Impresa/Small Business, Nº 2, p. 1-12.

- Torrès, O. (2004b) “The Proximity Law of Small Business Management: Between Closeness and Closure”, 49th International Congress of Small Business (ICSB), Johannesburg, South Africa, 20-3 June.

- Torrès, O.; Julien, P.A. (2005). “Specificity and denaturing of small business”, International Small Business Journal, Vol. 23, Nº 4, p. 355-377.

- Temiz, D.; Gökmen, A. (2014). “FDI inflow as an international business operation by MNCs and economic growth: An empirical study on Turkey”, International Business Review, Vol. 23, Nº 1, p. 145-154.

- Ucbasaran, D.; Shepherd, D. A.; Lockett, A.; Lyon, J. (2013). “Life after business failure: The process and consequences of business failure for entrepreneurs”, Journal of Management, Vol. 39, Nº 1, p. 163-202

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M. J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. L. (2016). “Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism”, Tourism Management, Vol. 53, Nº 1, p. 244-261.

- World and Travel Council (2016). Travel & tourism, economic world impact, https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic%20impact%20research/regions%202016/world2016.pdf.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Mihai Ibanescu est professionnel de recherche à l’Institut d’Entrepreneuriat Banque Nationale | HEC Montréal. Il a publié des chapitres de livres dans le domaine de la croissance des entreprises ou de la macroéconomie, ainsi que des articles concernant le management de l’innovation, de l’entrepreneuriat et des familles en affaires et il a présenté ses recherches dans une variété de conférences internationales en management et en économie. Il est l’auteur principal des dernières éditions de l’Indice Entrepreneurial Québécois. Ses recherches actuelles portent sur différents aspects de l’entrepreneuriat. Il a reçu des prix pour son activité de recherche.

Gabriel M. Chiriță : Titulaire d’un Ph. D. en stratégie et entrepreneuriat de HEC Montréal, Gabriel M. Chiriță est professeur en management et stratégie à l’UQAR. Il a également travaillé plusieurs années en tant qu’avocat spécialisé en droit fiscal et commercial, ce qui lui a permis de se familiariser avec les enjeux du monde des affaires. Ses recherches se concentrent sur trois axes : (1) le renforcement des capacités d’innovation des grandes entreprises par le biais des incubateurs qu’elles mettent en place, (2) l’innovation de modèle économique (ou d’affaires), (3) l’émergence des intentions entrepreneuriales et l’entrepreneuriat hybride.

Christian Keen est chercheur principal à la Faculté de gestion Desautels de l’Université McGill et consultant. Christian possède une vaste expérience de recherche et de travail dans les économies émergentes et développées. Par rapport à son expérience professionnelle, il a été membre de plusieurs conseils d’administration de sociétés privées et d’ONG. Il enseigne au MBA et des cours pour cadres en entrepreneuriat, en commerce international et en stratégie. Christian est membre du comité éditorial du Journal of International Entrepreneurship et du International Journal of Entrepreneurship Small Business. Il a publié et présenté ses recherches dans plusieurs conférences internationales.

Luis Cisneros est professeur agrégé au Département d’entrepreneuriat et innovation ainsi que directeur scientifique du Pôle entrepreneuriat, repreneuriat et familles en affaires à HEC Montréal (Canada). Ses intérêts de recherche portent sur l’entrepreneuriat, les PME, les modèles d’affaires et les entreprises familiales. Luis Cisneros détient un doctorat ès Sciences de gestion (Groupe HEC Paris, France).

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Mihai Ibanescu es investigador en el Instituto de Emprendimiento Banco Nacional | HEC Montreal, Canadá. Ha publicado varios capítulos de libros sobre crecimiento de las PYMES y la macroeconomía; artículos sobre gestión de la innovación, emprendimiento y empresas familiares, y ha presentado sus investigaciones en varias conferencias internacionales sobre gestión y economía. Es el autor principal de las últimas ediciones del Índice de Emprendimiento de Quebec. Su interés actual de investigación se centra en diversos aspectos del emprendimiento. Su actividad de investigación ha sido premiada.

Gabriel M. Chiriță: Doctor en estrategia y emprendimiento por HEC Montreal, Gabriel M. Chiriță es profesor de administración de empresas y estrategia en la UQAR. También trabajó durante varios años como abogado especializado en derecho fiscal y mercantil, lo que le permitió familiarizarse con temas empresariales. Su investigación se centra en tres áreas: (1) el reforzamiento de la capacidad de innovación de las grandes empresas a través de las incubadoras de empresas que éstas implementan, (2) la innovación de los modelos de negocio, (3) la emergencia de intenciones emprendedoras y del emprendimiento híbrido.

Christian Keen es investigador principal senior en la escuela de negocios Desautels de la Universidad McGill y consultor. Christian tiene una amplia experiencia de investigación y trabajo en economías emergentes y desarrolladas. Su experiencia profesional incluye ser miembro de varias juntas directivas de empresas privadas y ONG. Es profesor de MBA y programas ejecutivos en emprendimiento, negocios internacionales y estrategia. Christian es miembro del consejo editorial de las revistas Journal of International Entrepreneurship y International Journal of Entrepreneurship Small Business. Ha publicado y presentado su investigación en varias conferencias internacionales.

Luis Cisneros es profesor asociado en el departamento de Emprendimiento e Innovación y es también el director científico del Polo Emprendimiento, Sucesión emprendedora y Familias empresarias en HEC Montréal (Canadá). Sus temas de interés en investigación son: emprendimiento, PyMEs, modelos de negocio y empresas familiares. Luis Cisneros es doctor en administración de empresas (Grupo HEC Paris, Francia).

Liste des figures

FIGURE 1

Standardized averages for key elements of each cluster

Liste des tableaux