Résumés

Abstract

Far from being restricted to exchanges between experts, specialised knowledge is mediated to audiences with different levels of specialization, from scientific reviews to newspaper articles. This diversity constitutes an often-overlooked challenge for translators. As a matter of fact, while documentation and terminology are always crucial, translation decisions are based on communicative parameters as well as cognitive and linguistic criteria. Although it is self-evident that linguistic choices are determined by the proficiency level of the readership, few authors have attempted to specify what those choices are and how the correlation operates, most notably in popularization discourse, and none of them has considered potential differences between languages and cultural settings. The focus of the paper is a bilingual (French and Spanish) corpus study carried out on newspaper articles dealing with stem cell research and cloning published in four different geographic regions (France, Quebec, Spain, Argentina). An original methodology was implemented for data collection and analysis. The number and nature of expressions used to convey each concept were then analyzed. Discursive strategies widely assumed to be a hallmark of popularization, like definitions and explanations, were also taken into account. Indices of metaphorical conceptualization and the underlying modes of conceptualization were identified. This study provides concrete data to a debate that remains largely theoretical, and supports the conception of specialized communication as a continuum. The results go against well-established ideas about popularized texts, specially regarding the trademark status of “didactic features.” It seems imperative to acknowledge the heterogeneity of popularization and to consider the role of textual genre constraints in the way specialized knowledge is introduced. Furthermore, the data obtained seems to substantiate the recent questioning of the canonical view of popularization as a mere translation.

Keywords:

- specialized translation,

- popularization,

- denomination,

- metaphorical conceptualisation,

- corpus study

Résumé

Loin d’être cantonné parmi les experts, le savoir est diffusé pour différents publics à différents niveaux de spécialisation, des articles de synthèse aux textes journalistiques. Une telle diversité constitue pour les traducteurs un défi rarement mentionné. En effet, bien que la documentation et les recherches terminologiques s’avèrent cruciales, les décisions de traduction se fondent autant sur des critères communicatifs que cognitifs et linguistiques. Or, s’il est évident que les choix sont déterminés par les connaissances des lecteurs, peu de chercheurs précisent quels sont ces choix et comment opère cette corrélation, notamment en ce qui concerne la vulgarisation. De plus, les études linguistiques ne se sont pas penchées sur les différences entre les langues et les cultures. Cet article présente une étude bilingue (français et espagnol) d’un corpus d’articles journalistiques à propos de la recherche sur les cellules souches et sur le clonage publiés dans quatre régions (France, Québec, Espagne, Argentine). Une méthodologie originale a été mise sur pied pour la collecte et l’analyse des données. Le nombre et la nature des expressions employées pour faire référence à chaque notion spécialisée ont été pris en compte, ainsi que certains mécanismes discursifs considérés typiques du discours de vulgarisation, comme les définitions et les explications. Enfin, les indices de conceptualisation et les modes de conceptualisation métaphorique ont été identifiés. Cette étude fournit des données empiriques qui viennent enrichir un débat qui demeure largement théorique, et étaye la conception de la communication spécialisée en tant que continuum. Les résultats contredisent certaines idées ancrées à propos des textes de vulgarisation, particulièrement quant à l’importance des « procédés pédagogiques ». Il semble essentiel de mettre en évidence l’hétérogénéité du discours de vulgarisation et de tenir compte des contraintes posées par le genre textuel dans la façon d’exprimer les connaissances spécialisées. Enfin, les données obtenues sont compatibles avec la récente remise en question de la vision canonique de la vulgarisation comme traduction.

Mots-clés :

- traduction spécialisée,

- vulgarisation,

- dénomination,

- conceptualisation métaphorique,

- étude sur corpus

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

When considering the challenges of translating specialized texts, documentation and terminological research first come to mind, followed by the need to master phraseology as well as the linguistic conventions of the field (from acronyms to stylistic preferences). There is however a difficulty that is frequently overlooked: in the actual texts, specialized concepts may be rendered, not only by terms and their variants but also by elliptic forms, lay denominations, paraphrases, definitions, explanations, and so forth. Far from being restricted to exchanges between experts, knowledge is mediated to different audiences with different levels of specialization, and the diversity of expression is intertwined with the diversity of specialized communication. For instance, in scientific articles written in English, Alzheimer and Alzheimer’s regularly stand for Alzheimer’s disease. The problem for a translator lies not only in the existence of such elliptic forms in other languages, but in their usage in discourse (authors of scientific texts in French seem to favor the full denomination, while the short form is reserved for less specialized texts). More specifically, in order to choose the terminology to be used—or not—, the phraseology needed to render an idiomatic text, and the appropriate discursive strategies, it is crucial to determine the proficiency level of the intended readership. The challenge, obvious to the extent of being taken for granted, resides in the fact that specialized translation decisions are based on communicative parameters as much as cognitive and linguistic criteria.[1]

The communicative aspect of specialized translation has been recently brought to the forefront in a compendium of our discipline, the Oxford Handbook of Translation Studies (Wright 2011). In the article on scientific, technical and medical translation, Wright highlights the diversity of “Sci-Tech” discourse, which she considers to be a continuum, with “scholarly research intended for peer-to-peer communication” at one end, and “plain text instructions for end users of technological products” at the other end. She warns:

Differences in usage register can trigger variations in terminology and style, as well as in the general language matrix surrounding special language. Depending on situational factors and the projected target audience, a given concept may be designated by variant terms reflecting different registers within the same special language. For instance, tummy, stomach, gut, belly, and even a few others might occur appropriately in different situational contexts. These factors affect target-term choice–English appendix might be translated in a specialized text in German as Appendix, but as Blinddarm for lay readers.

Wright 2011: 247

Yet, the correlation between these variables is not well defined; several questions remain: At what point in the continuum of specialized communication is it “safe” to use a lay term like Blinddarm? Should then scientific terms be avoided all together? And if not, which ones are to be used, and how should they be introduced? What are the variations in style and in the “general language matrix,” and how do they relate to each “usage register”? Moreover, it cannot be assumed that the answers to these questions are impervious to language and culture.

The relevance of this issue becomes even more patent when the role of translators as disseminators of scientific and technical knowledge is taken into account. As Wright points out, “requesters may want to shift the function between ST and TT based on their intentions vis-à-vis the target audience” (Wright 2011: 253). Therefore, “heterofunctional approaches are not uncommon,” such as translation “for information,” “indicative translation,” and “adaptation of pure science ST materials to popular science TT articles” (Wright 2011: 254). In other words, translation often doubles as popularization, which begs the need to better understand the interplay of specialization level and linguistic expression, while considering potential differences between languages and cultural settings.

This article presents the results of a bilingual corpus study focused on the way specialized concepts are presented to a lay audience (Raffo 2007). It is intended to further the characterization of specialized discourse—more specifically in popularization texts—from a translator’s standpoint, and provides much needed empirical data to a discussion that remains largely theoretical. After a brief description of the methodological framework and corpus, the data obtained will be discussed within the context of previous work from other authors, mainly in the fields of linguistics and cognitive sciences. In the concluding remarks, current research on public communication of science is also taken into account.

2. When Stem Cells Make News

The main goal of the study was to gather data on how specialized notions are presented to a lay audience in different languages and publication settings. Therefore, several variables had to be taken into account. Since the purpose of the study was to observe native discursive behavior, a corpus of authentic (not translated) texts was compiled. The corpus only comprises texts from one “end” of the specialization scale and one genre: informational newspaper articles dealing with a scientific topic. The articles, in French and Spanish, were published in major newspapers from France, Quebec, Spain and Argentina.[2]

In order to avoid a diachronic bias, the compilation of the corpus was based on a “discursive moment” (moment discursif) as understood by Moirand (2003): a narrow timeframe during which the media deals profusely with a subject matter, usually after a specific event. In this case, the event was the announcement of the extraction of stem cells from a cloned human embryo. Thus, 11 texts published in February 2004 were selected (9,845 words in total, 6,125 in Spanish and 3,720 in French). The choice of a discursive moment proved to be useful to ensure the thematic and–more importantly–conceptual uniformity of the corpus.

The texts were annotated manually following a strict cognitive principle, namely, the reference to a specialized concept.[3] As a consequence, the expressions were collected regardless of their morphology or their syntactic structure. The terminological status was not considered as a criterion for data collection. This avoided formal and terminological biases, and provided data representative of the diversity of expression in discourse, from single units (célula [cell]) to whole propositions (células capaces de formar músculos, huesos, tejidos y neuronas [cell capable of making muscles, bones, tissues and brain cells]), specialized (embryon) and lay terms (malade for the term patient) alike.[4]

A great amount of data was obtained; 475 expressions in Spanish and 280 in French rendered a total of 184 specialized concepts, and a conceptual core of 35 concepts appearing in both languages and in all publication settings was identified, allowing for comparison. It is worth noting that the concepts comprised in this conceptual core are also the most frequently mentioned in the corpus (61.58% of all references to specialized concepts; 221 expressions in Spanish and 167 in French). The present paper focuses on some surprising results that contradict well-established ideas about popularization, and suggest that the opposition between expert communication and popularization is not so clear-cut.

3. Terminology and Variation

The level of specialization of a text is usually thought to be directly proportional to usage of terminology. Terms are considered the realm of expert communication, while popularization is linked to common words and paraphrasing. However, empirical research on this matter has so far been contradictory. On the one hand, according to Ciapuscio (2003), the terminology used in scientific texts is systematically replaced by “banal” terms and paraphrases in newspaper articles, although she acknowledges the existence of an “intermediate zone between the so-called special lexicon and the general lexicon” (Ciapuscio 2003: 90, my translation).[5] On the other hand, Bucchi claims that “in linguistic terms [treatment of scientific themes by the non-specialist press] is often not particularly distant from specialist communication” (Bucchi 2008: 59) on the basis that “Casadei (1994, cited in Bucchi 2008: 59), for example, has conducted lexical analysis of popular science texts, textbooks and specialist articles on physics, finding similar levels of technicality in the three genres” (Bucchi 2008: 73). A third view is represented by other authors who observed a partial overlap of the denominations used in expert and popular texts (Freixa 2002; Cassany and Martí 1998). Most notably Freixa reports an intersection of expression in 35% of the concepts mentioned in two corpora of texts with different levels of specialization (scientific communications and flyers).

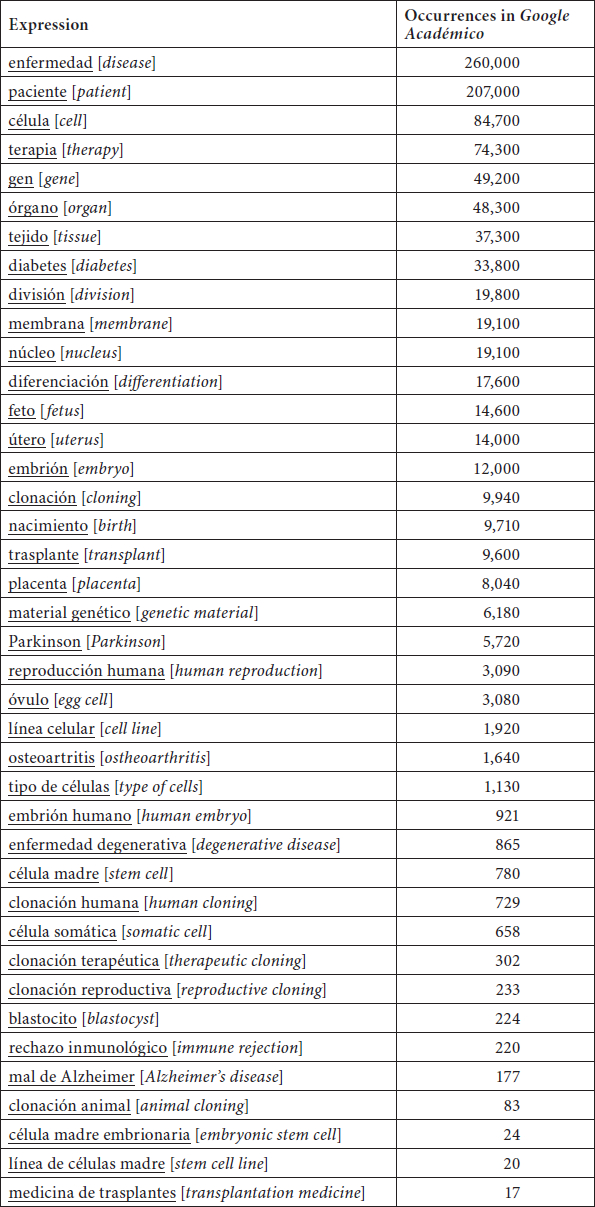

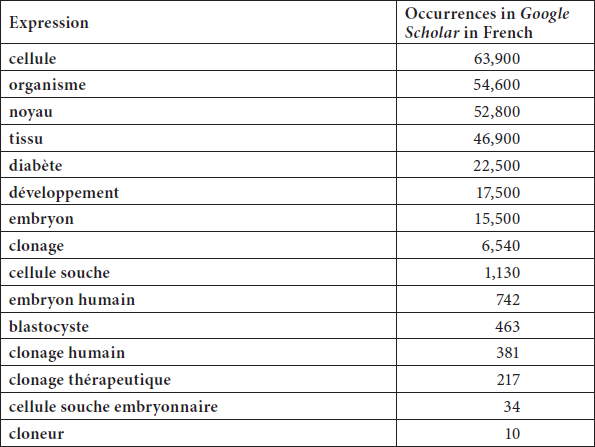

The data gathered during this study support the latter stance. An extensive comparative analysis with scientific articles being out of the scope at this stage, a small-scale test was conducted. From the corpus in each language, a sample of expressions common to both publication settings was selected (see Tables 1 and 2 below). It is important to point out that these linguistic sequences are not necessarily specialized terms, since the data collected include every unit or syntactic construction used to render a specialized concept. The usage of the selected expressions was verified in two extremely large corpora of highly specialized texts—indexed in Google Académico and Google Scholar in French, respectively. In the case of predicative nouns, an argument was added to the query in order to specify the concept (développement, embryon); enfermedad [disease] was added to the search for Parkinson [Parkinson] for the same reason.

All of the expressions from the sample were found in scientific texts, and several even with a very high frequency. The number of occurrences of each expression is shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1

Sample of common expressions in the texts from Spain and Argentina, and number of occurrences in Google Académico

Table 2

Sample of common expressions in the texts from France and Quebec, and number of occurrences in the French version of Google Scholar

The presence of these expressions in the Google Scholar corpora hints to their scientific status, already obvious in some cases (cellule). Their presence in a corpus of newspaper articles is a strong indication of continuity rather than polarity: popularization does not always shy away from specialized terminology.

It is possible to hypothesize that the use of scientific denominations in popular texts, and especially in newspaper articles, is a consequence of the general public being more familiar with the topic. This familiarity could very well vary from one culture to another due to social and economic factors (i.e. research interests and capabilities related to available resources, religious taboos, and/or prevalence of certain diseases). Translation decisions must take into account such factors, and their impact on linguistic choices.

Contrary to the matter of terminology, expressive diversity is usually an undisputed characteristic of popularization. Unbounded by the scientific imperatives of accuracy and economy, authors of popular texts may freely resort to lay denominations and paraphrases to introduce specialized concepts. Nevertheless, Wright reminds us that variants exist even in highly specialized texts since “the myth of mononymy and monosemy […] only applies in narrow contexts” (Wright 2011: 247). In fact, Freixa (2002) observed variation in both levels of specialization, even if it is more important in popular texts.

Actually, a global comparison may not suffice to explain the phenomenon. A more significant aspect lies in the dispersion of the variation, and particularly in its distribution. The results of the present study show a great dispersion: while 1 to 3 expressions refer to most concepts, the concept //to extract a stem cell from a cloned human embryo// was rendered by 20 expressions in the corpus from Spain, 14 in the corpus from Argentina, 15 in the corpus from France, and 4 in the corpus from Quebec. It is interesting to note that the number of expressions used to render each concept does not have a normal distribution, and therefore the mean value is not representative of the phenomenon.

As it is the case with terminology use, it is logical to assume that less variation in the expression of a given concept corresponds to a deeper knowledge of it. This knowledge may also be influenced by social and economic circumstances. However, another cognitive parameter seems to play a key role in the dispersion of the data: the number of expressions varies according to the type of concept. That is, entities bring about notably less variation than processes (//embryo development//) or actions (//to heal a patient//). For instance, the entity //oocyte// was rendered 15 times by 1 expression in the corpus from Spain, 13 times by 4 expressions in the corpus from Argentina, 17 times by 2 expressions in the corpus from France, and 8 times by 1 expression in the corpus from Quebec. The action //to clone an embryo// was rendered 27 times by 15 expressions in the corpus from Spain, 15 times by 10 expressions in the corpus from Argentina, 22 times by 15 expressions in the corpus from France, and 17 times by 10 expressions in the corpus from Quebec. Further research is evidently needed to confirm this finding and examine the correlation of conceptual category and variation in more extensive corpora.

4. Strategies of Popularization

Several discursive features have been considered the hallmark of popularization. They serve a cognitive as well as a textual purpose: to help the reader structure and integrate new knowledge, and to ensure textual coherence and cohesion. Definition, description, paraphrase, narration, modalization, and metaphorical and analogical expressions have been mentioned among other strategies (Calsamiglia and Van Dijk 2004). In this study, metalinguistic and anaphoric constructions, definitions, and explanations, as well as metaphoric expressions were analyzed.

In fact, the most interesting aspect of the results is the lack of data itself, since these discursive strategies are scarcely exploited in the texts of the corpus. Co-reference between expressions is rarely indicated, readers having to rely on context as well as their linguistic and encyclopedic baggage. Nonetheless, their occurrences have several purposes. Anaphoric structures contribute to the organization of knowledge with generic terms (1) and paraphrasis (2).

Anaphor is also used to change the focus from one aspect of the concept to another, as in (3).

Changing the conceptual class with a “false generic” (4), expressing appreciation (5), and paraphrasing in discourse (6) situate specialized knowledge in a social context.

The cited examples illustrate the polemic nature of cloning techniques, and the representation of science as a path to knowledge and progress.

Cassany and Martí Olivella (2000) conceive popularization as a reformulation of scientific material, which entails a great number of conceptual, textual, and discursive transformations of the specialized knowledge structure. The question remains as to the nature of these transformations and whether they are indeed specific to popularization. As a matter of fact, the results of the present study could be explained by the characteristics of the genre studied; namely the strictly informative nature of a newspaper article, as opposed to the expositive function of a magazine article. The influence of generic constraints in the use of discursive resources—or lack thereof—is worth exploring in future research.

5. Metaphor and Conceptualization

Pervasive in ordinary language and thought, metaphor has been recognized as a key feature in popularization (Loffler-Laurian 1994; Liakopoulos 2002). However, the fact that it has also been extensively studied in relation to scientific discourse (among others, Van Rijn-Van Tongeren 1997; Temmerman 2002; Vandaele, Boudreau et al. 2006; Vandaele 2009) belies any claim of specificity to a given discourse. There are also different stances regarding the nature of metaphor at different levels of specialization. Boyd (1993) distinguishes heuristic metaphor, used in science to enable theorization and organization of knowledge, from didactic metaphor, present in popular texts with an exegetical function. This distinction has been challenged by Knudsen (2003), who conducted an analysis of scientific papers and magazine articles.

For the present study, a cognitive view of metaphor has been adopted, that is, it is not considered as a linguistic trope but as a cognitive mechanism. Metaphorical conceptualization operates as a projection of a conceptual source domain onto a target domain, which allows the reader to understand “one kind of thing in terms of another” (Lakoff and Johnson 1980/2003: 5). This approach has been successfully applied in translation studies by Vandaele (2009 for an overview) to describe biomedical discourse. In several works, she shows that modes of metaphorical conceptualization underlie terminology and phraseology in the life sciences (e.g., the conceptualization of cells and molecules as people is manifested in the sentence The millions of cells that make up a multicellular organism can work together). They are therefore closely related to idiomaticity, and they can create equivalence problems (Vandaele 2009). Vandaele also put forward the denomination “indices of conceptualization” for the “lexical entities on which rests the projection and evocation of at least two representations” (Vandaele 2009: 191, my translation).[6]

In this study, the indices of metaphorical conceptualization were identified within the expressions collected, which allowed the identification of two main modes of conceptualization. On the one hand, biological entities (cell, embryo, organism, and cell nucleus) are perceived as intentional beings (living or human beings). This mode of conceptualization underlies a great number of metaphorical expressions (the small capitals indicate the index of conceptualization):

On the other hand, biological entities are understood as objects, machines, manufactured products or equipment.

Here it is possible to distinguish a clash between two ethical stances regarding the living status of an embryo, and the “morality” of the extraction of stem cells. This passage constitutes a clear example.

Needless to say, awareness of this tension is of paramount importance for translators.

When these results are put into perspective with previous work by Vandaele (see 2009), it becomes evident that the modes of conceptualization revealed in the newspaper articles are consistent with the conceptualization present in highly specialized texts.[7] Journalists borrow scientific phraseology (capables above), and expand lexical networks in a manner that is coherent with the underlying mode of conceptualization (enseñarle [to teach] above). The data gathered in this study suggest a cognitive and linguistic continuity. Thus, it is possible to concur with Knudsen: “theory-constructive metaphors can be used for pedagogical purposes, and—as will be suggested below—perhaps even the other way round” (Knudsen 2003: 1259).

6. Translators as Communicators of Science

The conflicting positions regarding the features of popular texts reflect an evolution in the conception of popularization. The traditional view considers it as a transfer of knowledge from scientists to the lay public, mediated by experts or journalists. Bucchi (2008) points out that this “diffusionist conception” relies on a metaphor of translation, which opens the door to the same misgivings: popular texts are seen as fundamentally different from scientific communication; media offers a “dirty mirror,” an “opaque lens.” According to Bucchi:

this vision has emphasized the public’s inability to understand and appreciate the achievements of science due to prejudicial public hostility as well as to misrepresentation by the mass media, and adopts a linear, pedagogical and paternalistic view of communications.”

Bucchi 2008: 58

The canonical stance has been widely criticized by scholars in science communication, science studies, discourse analysis, and applied linguistics. As mentioned above, popularization is seen as a reformulation of scientific material (Cassany and Martí Olivella 2000). It becomes “a matter of interaction as well as information” (Myers 2003: 273), and its communicative dimension is brought to the forefront. Myers illustrates this dynamic:

A study of DNA fingerprinting, on the face of it a scientific topic, found first in scientific journals, would lead to issues of chance and probability, guilt and innocence, race, nationality, and the conception of what it is to be an individual. When reporters frame news articles on DNA fingerprinting, they are thinking of these possible ways of relating the techno-scientific elements to the things people care about, and when readers pick up the articles they interpret them in terms of just these frames.

Myers 2003: 272

Furthermore, a continuum seems to exist, since the boundaries between scientific and popular texts are blurry (Jacobi 1986). Thus, Bucchi (2008) favors the denomination “public communication of science” over “popularization.” He highlights the importance of social, political, and cultural contexts in the introduction of new knowledge, as well as the status and meaning of established scientific facts.

However, research on specialized communication has not yet reached a critical mass, especially with regards to the empirical evidence on which any theoretical claim ought to be based: the expressions in discourse. Studies are isolated and theoretical, methodological frameworks are not always clear, and criteria for analysis are inconsistent. The methodology and results presented in this paper hopefully constitute a stepping-stone to help fill this gap.

As a matter of fact, the data obtained substantiate the critique, and go against well-established ideas. The supposedly characteristic features of popular texts do not seem as important in newspaper articles, which leads us to consider the role of contextual and generic constraints. Moreover, the results support the idea of a continuum, not only at the linguistic level with the shared use of terminology and phraseology, but at the conceptual level as well, since the modes of conceptualization are consistent with highly specialized discourse. Thus, this study opens research avenues for a new and more precise characterization of public communication of science.

From a translation point of view, it seems evident that the characterization of specialized texts cannot be approached in terms of an ill-defined opposition between specialized and general language. Texts are the outcome of many variables: not only the specialized content conveyed and the language chosen to convey it, but also the modes of conceptualization, the time, place, and channel of communication, the knowledge, purpose and attitude of the author, and the intended readers, etc. Discourse, in its referential, conceptual, and communicative dimensions, is the translator’s arena.

Underlying this issue is the problematic definition of “term” as opposed to “word,” which creates “grey zones” and complicates the matter of determining the terminological status of an expression. The concept of “denomination,” as described by Kleiber, seems to be better suited to the reality of discourse.[8] It consists in a strong referential association between a sign and a concept as a result of usage or an actual act of denomination (Kleiber 1984). Such a definition puts forward the conceptual—rather than semantic—relationship between linguistic expressions and referents, and acknowledges its conventional nature.

Translation studies can both benefit from and contribute to research on the public communication of science. Indeed, it might be possible to establish a new metaphor of translation for the understanding of popularization, not as a direct transfer but as a task of “recontextualization” where the translator/communicator presents specialized knowledge in a new communicative situation, in a way that is relevant to the intended audience, thus giving it new meaning.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I have a great debt of gratitude to Sylvie Vandaele, my thesis supervisor, for making heads and tails of my questioning, wading through heaps of data, and imparting scientific rigor into my ideas. Any shortcoming of the project is however solely my responsibility. I also thanks the Social Science and Human Science Research Council of Canada for its support.

Notes

-

[1]

The importance of communicative—or even cognitive—factors does not seem as obvious to everyone. Dollerup argues that word for word translation of specialized texts “works in at least 80% of cases”! (Dollerup 2005)

-

[2]

The newspapers are Le Figaro and Le Monde (France), Le Devoir and La Presse (Quebec), El Mundo and El País (Spain), and La Nación and Clarín (Argentina).

-

[3]

The corpus was annotated manually with a set of XML tags created specifically for this project using the XML editor Oxygen (v.8.1). This method offers several advantages, namely its flexibility. It also allows the formulation of specific queries and data extraction as HTML tables or comma separated lists, which can be readily opened in many applications. The tenants of the method are described in Vandaele and Boudreau (2006).

-

[4]

Expressions in Spanish are underlined while expressions in French are written in bold.

-

[5]

“Zona intermedia entre el llamado léxico especial y el general.”

-

[6]

“Entité linguistique par laquelle opère la projection et qui évoque au moins deux représentations.”

-

[7]

A more detailed comparison between texts having different levels of specialization has been presented in collaboration with Vandaele (Vandaele and Raffo 2007).

-

[8]

Unfortunately, the word “denomination” is used rather liberally in the literature. Since a clear definition is not always provided, it becomes difficult to compare the results from different works (e.g. Cataldi 2004; Van Dijk 2003).

Bibliography

- Boyd, Richard (1993): Metaphor and theory change: What is “metaphor” a metaphor for? In: Andrew Ortony, ed. Metaphor and Thought. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 481-532.

- Bucchi, Massimiano (2008): Of deficits, deviations and dialogues: theories of public communication of science. In: Massimiano Bucchi and Brian Trench, eds. Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology. London / New York: Routledge, 57-76.

- Calsamiglia, Helena and Van Dijk, Teun A. (2004): Popularization Discourse and Knowledge about the Genome. Discourse Studies. 15(4):369-389.

- Casadei, Federica (1994): Il lessico nelle strategie di presentazione dell’informazione scientifica: il caso della fisica [Lexicon use among the strategies of presentation of scientific information: the case of physics]. In: Tullio De Mauro, ed. Studi sul trattamento linguistico dell’informazione scientifica. Rome: Bulzoni, 47-69.

- Cassany, Daniel and Martí, Jaume (1998): Estrategias divulgativas del concepto prión [Popularization Strategies for the concept ‘prion’]. Quark. 12:58-66.

- Cassany, Daniel and Martí Olivella, Jaume (2000): La transformación divulgativa de redes conceptuales científicas. Hipótesis, modelo y estrategias [Transformation in popularization of scientific conceptual networks. Hypothesis, model and strategies]. Discurso y Sociedad. 2(2):73-103.

- Cataldi, Cristiane (2004): El debate sobre los transgénicos en la prensa española: cómo los actores sociales denominan esta biotecnología [The debate over GMOs in the Spanish press: the social actors name the biotechnology]. Quark. 33:57-68.

- Ciapuscio, Guiomar E. (2003): Textos especializados y terminología [Specialized texts and terminology]. Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada.

- Dollerup, Cay (2005): Tackling cultural communication in translation. Interculturality & Translation. 1:11-30.

- Freixa, Judit (2002): La variació terminològica. Anàlisi de la variació denominativa en textos de diferent grau d’especialització de l’área de medi ambient [Terminological variation. Analysis of denominative variation in texts of different levels of specialization in the environmental field]. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona.

- Jacobi, Daniel (1986): Diffusion et vulgarisation: itinéraires du texte scientifique. Paris: Belles Lettres.

- Kleiber, Georges (1984): Dénomination et relations dénominatives. Langages. 76:77-94.

- Knudsen, Susanne (2003): Scientific metaphors going public. Journal of Pragmatics. 35(8):1247-1263.

- Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark (1980/2003): Metaphors we live by. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Liakopoulos, Miltos (2002): Pandora’s Box or panacea? Using metaphors to create the public representations of biotechnology. Public Understanding of Science. 11:5-32.

- Loffler-Laurian, Anne-Marie (1994): Réflexions sur la métaphore dans les discours scientifiques de vulgarisation. Langue française. 101:72-79.

- Moirand, Sophie (2003): Communicative and cognitive dimensions of discourse on science in the French mass media. Discourse Studies. 5(2):175-206.

- Myers, Greg (2003): Discourse studies of scientific popularization: questioning the boundaries. Discourse Studies. 5(2):265-279.

- Raffo, Mariana (2007): Vulgarisation et traduction: représentation discursive des notions scientifiques biomédicales en français et en espagnol. Master dissertation, unpublished. Montréal: Université de Montréal.

- Temmerman, Rita (2002): Metaphorical Models and the Translation of Scientific Texts. Linguistica Antverpiensia. 1:211-226.

- Van Dijk, Teun A. (2003): Specialized discourse and knowledge: A case study of the discourse of modern genetics. Cadernos de Estudos Lingüísticos. 44:21-55.

- Van Rijn-Van Tongeren, Geraldine W. (1997): Metaphors in medical texts. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi.

- Vandaele, Sylvie (2009): Les modes de conceptualisation du vivant: une approche linguistique. In: François-Emmanuël Boucher, Sylvain David et Janusz Przychodzen, eds. Pour ou contre la métaphore? Pouvoir, histoire, savoir et poétique. Paris: L’Harmattan, 187-207.

- Vandaele, Sylvie, Boudreau, Sylvie, Lubin, Leslie, et al. (2006): La conceptualisation métaphorique en biomédecine: indices de conceptualisation et réseaux lexicaux. Glottopol. 8:73-94.

- Vandaele, Sylvie and Boudreau, Sylvie (2006): Annotation XML et interrogation de corpus pour l’étude de la conceptualisation métaphorique. JADT2006, Journées internationales d’analyses statistiques des données textuelles, Besançon, 19-21 avril 2006. Vol. 2, 951-959.

- Vandaele, Sylvie and Raffo, Mariana (2007): Conceptualización metafórica en el discurso científico y en el de divulgación [Metaphorical conceptualization in scientific discourse and popularization]. In: Morales, O. A. et al., (dir.) Actas del I Congreso International sobre Lenguaje y Asistencia Sanitaria, IULMA, Universidad de Alicante, 24-24 october 2007 (cederom).

- Wright, Sue E. (2011): Scientific, Technical, and Medical Translation. In: Kirsten Malmkjaer and Kevin Windler, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Translation Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Online: .

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Sample of common expressions in the texts from Spain and Argentina, and number of occurrences in Google Académico

Table 2

Sample of common expressions in the texts from France and Quebec, and number of occurrences in the French version of Google Scholar