Résumés

Abstract

This paper offers an overview of the development of Legal Translation Studies as a major interdiscipline within Translation Studies. It reviews key elements that shape its specificity and constitute the shared ground of its research community: object of study, place within academia, denomination, historical milestones and key approaches. This review elicits the different stages of evolution leading to the field’s current position and its particular interaction with Law. The focus is placed on commonalities as a means to identify distinctive reference points and avenues for further development. A comprehensive categorization of legal texts and the systematic scrutiny of contextual variables are highlighted as pivotal in defining the scope of the discipline and in proposing overarching conceptual and methodological models. Analyzing the applicability of these models and their impact on legal translation quality is considered a priority in order to reinforce interdisciplinary specificity in line with professional needs.

Keywords:

- Legal Translation Studies,

- interdiscipline,

- scope and historical development,

- legal texts,

- legal translation methodology

Résumé

Le présent article propose un tour d’horizon du développement de la traductologie juridique, une interdiscipline majeure de la traductologie. Il passe en revue des éléments-clés qui ont façonné sa spécificité et qui constituent pour les chercheurs un terrain commun : son objet d’étude, sa place dans le monde universitaire, sa dénomination, ses étapes historiques et ses principales approches. Les différents stades de son évolution sont décrits jusqu’à son état actuel, ainsi que son interaction particulière avec le droit. L’accent est mis sur les points communs afin d’identifier des repères distinctifs et d’établir des pistes pour son futur développement. La catégorisation exhaustive des textes juridiques et l’examen systématique des variables contextuelles sont mis en valeur pour délimiter le champ de la discipline et proposer des modèles conceptuels et méthodologiques intégraux. L’analyse de l’applicabilité et de l’impact de ces modèles sur la qualité des traductions juridiques est considérée comme une priorité pour consolider la spécificité interdisciplinaire en accord avec les besoins professionnels.

Mots-clés :

- traductologie juridique,

- interdiscipline,

- champ et développement historique,

- textes juridiques,

- méthodologie de la traduction juridique

Corps de l’article

Las innovaciones más originales y fecundas resultan de la recombinación de especialidades situadas en el punto de confluencia de varias disciplinas.

Dogan 1997a: 17[1]

1. Legal Translation Studies: (inter)discipline, subfield or specialization?

After decades of consolidation and expansion, Translation Studies (TS) is experiencing a marked trend towards increasing specialization by area of practice and research (see, for example, Brems, Meylaerts et al. 2012). An initial emphasis on building self-assertive conceptual models beyond linguistic-oriented theories paved the way for more sophisticated approaches to specific branches of translation in contact with other disciplines. Since the empowering “cultural turn” (Snell-Hornby 2006) of the 1980s and 1990s, TS has progressively engaged in an “interdisciplinary turn” (Gentzler 2003) characterized by new paths of inquiry, and a “technological turn” (Cronin 2010) favored by new computer tools and interaction with Information Technology.

In fact, given the intrinsic nature of translation as carrier of knowledge across fields and the myriad of influences shaping the emergence of its modern theories (Holmes 1972/1988), TS is “genetically predisposed” to interdisciplinary development. It is through the shared concern with communication that other disciplines engage with translation; in turn, the need to grasp and convey nuances ultimately lead translators and TS scholars to enrich their analytical models with insights from the domains that underpin specialized discourses. This has been the case of legal translation over the last three decades, to the point that, as few would question nowadays, Legal Translation Studies (LTS) has become one of the most prominent fields within TS.

LTS will be understood here as an (inter)discipline concerned with all aspects of translation of legal texts, including processes, products and agents. Linguistic mediation between legal systems or within multilingual legal contexts (such as international or multilingual national systems) and the academic study of such mediation require the coherent integration of concepts from TS, Linguistics (as drawn upon through TS) and Law. Without these elements, it can be argued that legal translation as a problem-solving activity would be an unreliable exercise, and LTS would not stand where it stands today. This intermingling is an example of hybridization, which, according to Dogan (1997b: 435), implies “an overlapping of segments of disciplines, a recombination of knowledge in new specialized fields” that constitutes a major source of knowledge production and innovation in all sciences.

The consideration of an interdisciplinary field like LTS as “discipline” or “interdiscipline” tends to depend on the recognition of scholarly work by academic institutions (McCarty 1999, Munday 2001), and on the degree of autonomy of the field:

New disciplines emerge not only as knowledge grows and spreads but also as power relations and reputations change within academia. Historically, new disciplines have often emerged at the interface of existing ones, and so at first they inevitably have the nature of interdisciplines. […] Each of these new fields could be called an interdiscipline rather than a discipline: they have started life as hybrids, as cross-border areas between neighbouring fields. Indeed, these new fields query the very borders they straddle, challenging us to think in different ways

Chesterman 2002: 4

Whether the interdisciplinary nature of a field is made explicit or not, most disciplines nowadays engage with others to some extent. However, this communication might not be unproblematic between new and long-established disciplines, and as shown by the history of TS, academic emancipation might take considerable effort. Even if this process is still relatively recent, and full recognition is yet to be achieved in some academic constituencies, LTS has clearly benefited from the consolidation of TS in general. If the overriding priority was once to claim TS’s own territory in between adjacent fields, scholars in specialized branches such as LTS are now taking interdisciplinarity into new territory on the basis of TS-specific paradigms. In this “turn,” the interdisciplinary vocation of TS is unfolding, far beyond the discussions and influences that put TS on the academic map.

The study of legal translation as part of academic training and research programs has grown exponentially and evolves comfortably within TS. In this context, terms such as “subfield,” “subdiscipline,” “branch” or “specialization” are often used to refer to legal translation and LTS as subdivisions or categories of translation and TS, respectively. Although the question of denominations will be addressed in section 3, it is worth noting at this point that “legal translation” is used here to refer to the area of practice and the subject of study, while “Legal Translation Studies” (“LTS”) is reserved for the academic discipline, even if “legal translation” is commonly used to refer to the same discipline. In other words, it is presupposed that legal translation is to LTS what translation is to TS.

In the next sections, we will focus on the key elements that shape the identity of LTS today: object of study, place within academia, denomination and historical evolution. For young and dynamically-changing disciplines, this kind of stocktaking exercise can be particularly useful and even a necessity. Chesterman (2002: 2), making this point in relation to TS, suggested that “scholars tend to focus on their particular corners, and communication between different sections of the field may suffer, as people stress more what separates approaches than on what unites them – at least in the initial stages.” Indeed, after a period of intense growth, surveying the common ground of the LTS research community can help to underpin the collective vision and specificity of this maturing field.

2. Scope of legal translation

Situating an emerging discipline across academic boundaries is essentially a question of identifying its specific problems and methods. In the case of LTS, the consideration of legal translation as a category in its own right has been rarely challenged in the past few decades (Harvey 2002, Mayoral Asensio 2002). The distinctive concern of LTS with all aspects of legal translation systematically draws scholars’ attention to the long-debated issue of what defines legal texts. These have been variously classified according to main textual functions (for example, Bocquet 1994, Šarčević 1997), or according to discursive situation parameters (for example, Gémar 1995, Borja Albi 2000, Cao 2007). These classifications converge on the identification of three major groups of texts: normative texts, judicial texts and legal scholarly texts (from more prescriptive to more descriptive and/or argumentative in nature). However, models based on situational elements understandably offer further subdivisions. For instance, contracts are included within normative texts in categorizations according to primary function, whereas they are classified under a separate heterogeneous group of “private legal texts” (for example, Gémar 1995, Cao 2007) or “texts of application of law” (Borja Albi 2000) in the latter models.

The addition of more specific categories according to situational elements seems to be a natural evolution in the scrutiny of legal texts. On the one hand, the blend of functions in legal texts (for example, judgements with a normative value in common law systems) and their high degree of intertextuality (with the typical role of written sources of law as primary references in language use across legal text typologies) call for further differentiation. On the other hand, what matters most for legal translation is the characterization of groups of texts corresponding to specific varieties or styles of legal language, and this is generally a question of text producers and purposes in communicative situations. Since legal language is “a set of related legal discourses” (Maley 1994: 13) and not a uniform language, legal translators need to discriminate the features of the different styles reflected in original texts as part of translation-oriented analysis. As highlighted by Alcaraz Varó and Hughes (2002: 103) when advocating “a more systematic awareness of text typology,” “the translator who has taken the trouble to recognize the formal and stylistic conventions of a particular original has already done much to translate the text successfully.”

Apart from the language of legislators, judges or scholars, it is possible to identify, for instance, a category of texts characterized by the “language of notaries” (langage des notaires; lenguaje notarial), which accounts for a considerable number of legal texts in certain countries. Texts drafted by legislators, judges, scholars or notaries on a particular aspect of probate law, for example, will share key concepts and phraseology (the legislative text normally conditioning and impregnating the other uses), but purposes and discursive conventions will certainly vary by text type. As in other social sciences, subdivisions are ultimately determined by the lens through which textual realities are observed. In turn, legal text typologies comprise a variety of legal genres and subgenres (for example, different kinds of contracts). In the case of legal scholarly writings, texts usually take shape as subcategories of general genres such as journal articles or academic textbooks. They are not always addressed to legal experts (for example, a press report on the details of a particular legal reform, comparable to a report on economic affairs written by an economist), and their stylistic features can be rather heterogeneous, but they all share a minimum degree of thematic specialization in descriptive and argumentative functions.

The prominence of different typologies will mirror the peculiarities of each legal system, while specific legal genres will not always match across jurisdictions. Overall, the more specific the categorization gets (textual function, text type and genre), the more layers of information are activated on discursive conventions, but also the less universal and the more culture-bound those layers become.

Beyond the differences between categorization models, there is consensus around the hybridity of legal texts, which reflects the high interdisciplinarity of law in dealing with all aspects of life. A piece of legislation on financial products, an agreement on the provision of chemical engineering services or an arbitration award on the conditions of trade within the shipbuilding industry will require research on technicalities associated with other specializations. While thematic crossings between fields in different branches of law and legal settings are countless, those encountered in the area of business and finance are traditionally highlighted to illustrate how often two specializations can merge in specific texts; and this can result in the classification of legal texts with predominantly non-legal specialist language under other branches of translation. However, in the examples provided, the text would remain of a legal nature and the subject of legal translation, as would be the case in instances where legal discursive features are minimal (for example, in certain private legal instruments) or intentionally tempered with non-specialist discourse (for example, through plain language movements).

In mapping the “textual territory” of LTS, discrepancies persist at its fringes, particularly regarding the place assigned to texts not dealing with legal matters but used in legal settings. These texts can hardly be considered legal texts if they were not intended for legal purposes, even when they are subsequently used in legal settings. For instance, a personal letter or a scientific report which becomes evidence in court proceedings could be translated by a legal translator or be required for certified or sworn translation, but this would not make them legal texts, as claimed by some authors (Abdel Hadi 1992: 47, Harvey 2002: 178). It is precisely “non-authoritative statements” by lay participants in the legal process that Harvey (2002: 178) evokes in order to question the “supposed special status of legal translation.” He includes contracts, wills, expert reports and court documents in what he calls “ ‘bread and butter’ activities for lawyers and legal translators,” and considers that a “more inclusive definition of what constitutes a legal text would cover documents which are, or may become, part of the judicial process.”

Echoing this view, Cao (2007: 11-12) identifies “ordinary texts such as business or personal correspondence, records and certificates, witness statements and expert reports” as part of “legal translation for general legal or judicial purpose,” and emphasizes that “ordinary texts that are not written in legal language by legal professionals” constitute “a major part of the translation work of the legal translator.” However, while these texts could be submitted to a legal translator in legal settings analyzed in LTS, they cannot be systematically considered legal texts. A scientific expert report on the use of hormones in cattle production with no trace of legal matters or legal language will not lose its scientific nature in a legal setting; and a further distinction must be made between non-lawyers’ texts initially intended for legal purposes (such as private agreements) and ordinary texts produced for other purposes but later used in legal settings (for example, personal correspondence). This distinction helps to delimit the boundaries of legal translation: as opposed to the latter texts, private legal instruments prepared by laypersons, even if more unpredictable in style than other legal text types, include certain performative discourse features in more or less formal provisions, and tend to follow certain legal genre conventions with frequent influences from professional legal models.

Adopting a pragmatic and conciliatory approach, it can be concluded that the link between legal theme and/or function and linguistic features is confirmed as minimum common denominator of legal texts (even if at varying degrees):

Legal texts constitute or apply instruments governing public or private legal relations (including codified law, case-law and contracts), or give formal expression to specialized knowledge on legal aspects of such instruments and relations;

These functions follow certain linguistic patterns that are characteristic of varieties of legal language in different discursive situations, allowing for the identification of legal text types (according to text producers and purposes), as well as legal genres (according to more specific textual functions and conventions);

Legal texts can also contain a great amount of specialized language from non-legal fields covered by law, while legal scholarly writings comprise a wide range of subcategories of general genres such as journal articles and textbooks.

Categorizations based on legal function, theme and discourse serve to differentiate “legal translation” from other categories reflecting context or type of translation and including legal texts but not exclusively: “judicial translation” (even if the bulk of texts in this setting will be comprised under the legal judicial text type); “sworn/official/certified translation” (albeit predominantly reserved for texts of a legal nature); or “institutional translation” (with a traditionally high presence of legal and administrative text subtypes, but a diversity of themes and other specialized discourses).

Table 1

Categorization of legal texts

Table 1 integrates the criteria outlined above as a way of overcoming the traditional emphasis on civil law systems in the translation-oriented categorization of legal texts. Despite differences in the relevance and legal effects of particular text types by legal system, and despite the difficulty in proposing comprehensive categorization models, it is most useful to situate specific genres within general text types in order to better frame the comparison of discursive features. For instance, the lawmaking role played by judicial decisions in common law countries cannot be equated with that of most judicial rulings in civil law systems, and their discursive features vary by genre and jurisdiction. Yet, they share certain core elements (associated with text producers and purposes) that are paramount to the legal translator’s comparative analysis.

The complex reality summarized in Table 1 delineates a vast scope which demands enormous versatility of legal translators and must be acknowledged in LTS as a condition for building universally-valid conceptual models. LTS scholars have often focused on particular legal relations and text types (predominantly legislative) as a basis for generalizations on legal translation.[2] The variability of legal linguistic phenomena and translation settings requires not only flexibility but also regular updating on discursive features, particularly in relation to the more dynamic branches of law and the impact of supranational convergence processes on such features.

3. Disciplinary contours and denominations

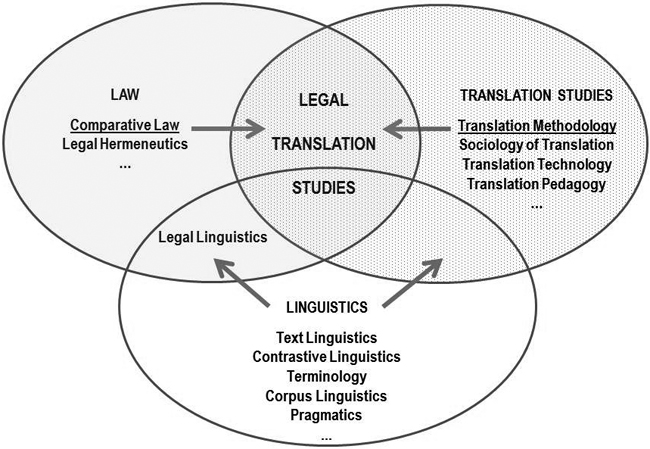

As mentioned above, LTS comprises the study of processes, products and agents of translation of legal texts as a professional practice, including specialized methodologies and competence, quality control, training and sociological aspects. Against the above background, once the “textual territory” of legal translation has been defined, the position of LTS between TS, Linguistics and Law can be pinpointed as represented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Disciplinary boundaries of LTS[3]

LTS builds on the core concepts of TS theories common to all translation specializations, including all aspects of translation methodology, that is, declarative and operative knowledge of the translation process and problem-solving procedures (translation-oriented analysis, translation strategies and competence). These concepts and metalanguage lie at the heart of any branch of translation as subject of study, including LTS. In turn, in developing its own communicative, cultural and cognitive approaches, among others, TS has drawn on notions from Communication Studies, Cultural Studies and Psychology, while studies in Translation Pedagogy, Translation Sociology and Translation Technology emerge as a result of crossings with other disciplines.

However, the major neighboring discipline from which TS has borrowed most heavily is Linguistics, particularly subfields or approaches within the realm of Applied Linguistics which offer relevant variables on language use and tools for translation-oriented and contrastive analysis: Text Linguistics, Discourse Analysis, Contrastive Linguistics, Corpus Linguistics, Terminology, Pragmatics, etc. LTS marries such insights to legal theory and practice in the dissection of legal discourses, terminology, genres and texts for translation from a TS perspective.

It is in the interface between TS (with its diverse influences) and Law that LTS finds its natural place in the academic landscape. LTS crucially relies on networks of legal knowledge in order to build interdisciplinary theories and methods. Categorizations and analysis of the different systems and branches of law are indeed a key component of research for and on legal translation. In the case of international law, translation plays a central role in rendering legal instruments multilingual in institutional settings, which attracts considerable attention in LTS, as has been traditionally the case with multilingual national systems.

In the scrutiny of the different branches of law for translation purposes, Legal Hermeneutics and Comparative Law stand out for their functionality: they offer useful techniques for the interpretation of legal texts and for the contrastive analysis of legal concepts and sources across systems. Legal comparative methodology has proved particularly relevant to legal translation, and its importance for LTS is nowadays uncontested (see section 4). Even if the purposes of legal comparative practice and legal translation practice are different (shedding light on legal issues as opposed to applying adequate translation techniques), both share the same interest in deconstructing semantic elements in their legal contexts in order to determine degrees of correspondence for decision-making (see, for example, works by legal experts De Groot 1987, Sacco 1992, Vanderlinden 1995, Brand 2007). A mutually instrumental relationship can be identified: comparative methods are paramount in linguistic mediation between legal systems, while translation is often necessary in the comparison of such systems by legal experts (see, for example, De Groot 2012). It is largely by merging general translation methodology with such legal analysis that LTS’s methodological specificity is reinforced.

The interdisciplinary concern with legal language is shared by the adjacent field of Legal Linguistics, which analyzes features of legal discourses at large, including comparative studies in Contrastive Legal Linguistics (see, for example, Mattila 2013), but lacks the distinctive TS core of LTS. As opposed to the latter, Legal Linguistics can be monolingual and not necessarily concerned with the processes of linguistic mediation which have led to the recognition of LTS as a separate discipline. In other words, Legal Linguistics is to LTS what Linguistics is to TS.

Although the distinction between Legal Linguistics and LTS is already well-established (in parallel to the distinction between Linguistics and TS), their shared interest in legal language explains the overlap of certain definitions and denominations, particularly in French. In this language, “jurilinguistique” is often used to refer to studies on both legal language and legal translation. This is largely due to the origin of the term in the Canadian context, where concerns about linguistic rights, and the quality of Canada’s French-language legal texts in particular, led to growing linguistic awareness since the 1960s, and eventually resulted in a tailor-made system of co-drafting of Canadian legislation (see, for example, Covacs 1982 and Gémar 2013). The challenges of bilingual legal drafting, beyond the confines of traditional perceptions of legal translation, became the object of scholarly work under the label of “jurilinguistique,” as coined by Jean-Claude Gémar (1982),[4] and translated as “Jurilinguistics” for the same volume. It was defined as follows:

Essentiellement, la jurilinguistique a pour objet principal l’étude linguistique du langage du droit sous ses divers aspects et dans ses différentes manifestations, afin de dégager les moyens, de définir les techniques propres à en améliorer la qualité, par exemple aux fins de traduction, rédaction, terminologie, lexicographie, etc. selon le type de besoin considéré.

Gémar 1982: 135

Gémar’s conception of Jurilinguistics matches standard definitions of Legal Linguistics (“linguistique juridique”) as a field within Applied Linguistics, but with a marked comparative dimension (that is, along the lines of Contrastive Legal Linguistics) suited to the Canadian origin of the term: “étude du langage (langue et discours) du droit comme objet de recherche et d’analyse par les méthodes de la linguistique (appliquée).Au Canada, cette étude est le plus souvent comparative (anglais-français)” (Gémar 1995, II: 182). From this perspective, jurilinguistique is considered as a disciplinary expansion from and transcending legal translation: “La terminologie et la jurilinguistique, entre autres, procèdent directement de la traduction – de l’anglais vers le français, plus particulièrement – et des difficultés qu’elle pose dans le contexte d’un État (fédéral) bilingue et bijuridique” (Gémar 1995, II: 2).[5]

Considering these nuances, and as rightly noted in the Termium database, “jurilinguistique” and “linguistique juridique,” and “Legal Linguistics” and “Jurilinguistics” in English, are not always regarded as perfect synonyms. In any case, the debate on the overlap between Legal Linguistics (linguistique juridique) and LTS (traductologie juridique) should not hinder the distinction between these complementary sister interdisciplines and their denominations. In English, the use of “Legal Translation Studies” has grown significantly with the expansion of the subject field;[6] “Legal Linguistics” is also well-established,[7] and “Jurilinguistics” commonly refers to the Canadian tradition. In French, “jurilinguistique” is widely used for the reasons explained above, often as interchangeable with “linguistique juridique” (despite the persistent connotations of each term; see, for example, Cacciaguidi-Fahy 2008), and co-exists with the specific term for LTS “traductologie juridique” and its variant “juritraductologie.” In the case of Spanish, the use of “Traductología Jurídica” is rather limited to date; “traducción jurídica” (the name of the activity) is predominantly preferred to refer to the discipline. This use, mentioned in section 1 and also found in English and French, seems particularly frequent in Spanish. Finally, “Lingüística Jurídica” and “Jurilingüística” follow the same pattern as in English, with the latter mostly linked to the Canadian tradition.

Even if these names are all compatible, and different culture-bound scholarly labels are a healthy sign of academic diversity, the consolidation of uniform denominations for LTS in line with its status within TS would contribute to its clear identification and further cohesion. In this sense, “traductologie juridique” and “Traductología Jurídica,” by analogy with “traductologie” and “Traductología,” as well as “Legal Translation Studies,” would be expected to find increasing echo within the academic community, together with general denominations of “legal translation” as object of study.

4. Historical development

Let us briefly delve into the historical evolution which has led to the position of LTS outlined above. Rather than an exhaustive review of approaches and authors, an overview will be outlined with focus on major stages and illustrative markers of development.

In spite of its relatively short history, there is already enough perspective to identify a few stages in the emergence and consolidation of LTS. Its recognition as academic field has been associated with that of TS in general since the 1970s, and stimulated by the school of Jurilinguistics in Canada. As a prelude to jurilinguistique, in the first Meta volume ever devoted to LTS, Gémar (1979) already presented legal translation as a new discipline, and highlighted the constraints and specificity of its subject matter. While recognizing that “il reste encore trop d’inconnus,” he regarded his own contribution at the time as a possible “point de départ à l’établissement d’une véritable méthodologie” of legal translation, and identified the need for an interdisciplinary approach: “toute approche devrait s’inspirer d’une forme de logique juridique, seul facteur essentiel de la marche épistémologique parce qu’il part d’un fait établi, celui de la réalité du droit et passe par la méthodologie qui représente le moyen entre la pratique et la théorie” (Gémar 1979: 53). In the same special issue of the journal, Michel Sparer’s views on the cultural dimension of legal translation illustrate how an emphasis on culture-bound communication was crystallizing as a means of empowerment of professionals in Canada: “Nous nous sommes débarrassés depuis peu de la fidélité littérale pour adopter avec profit une conception plus affinée et plus autonome du rôle du traducteur, celle qui consiste à traduire l’idée avant de s’attacher au mot” (Sparer 1979: 68).

Legal experts such as Pigeon (1982), also from Canada, and De Groot (1987) contributed to the debate on the implications of incongruities between legal systems for legal translation, and vindicated the relevance of functional equivalence and comparative legal methods, respectively. In the same period, Šarčević (1985), in a specific journal article, and Weston (1991), in a legal linguistic analysis of the French legal system, made new inroads into the analysis of translation techniques as applied to legal texts.

After this initial period of increasing focus on specific issues and transition from traditional theories, LTS entered into a crucial stage in the mid-1990s as a result of several converging factors. Firstly, three monographs were entirely devoted to paradigms of legal translation by leading representatives of the first generation of LTS scholars: Bocquet (1994, later expanded in 2008), Gémar (1995) and Šarčević (1997), subsequently followed by Alcaraz Varó and Hughes (2002) and Cao (2007) over the span of a decade. In spite of differences between their approaches, they all analyze features of legal language and translation problems resulting from conceptual incongruency, taking pragmatic and legal considerations into account, and defending the active role of the legal translator. These theories contributed to further defining the scope and academic profile of the field, and have inspired many contemporary researchers and translators. In fact, this period can be considered as catalytic for the development of shared conceptualizations in LTS and for the formation of a global LTS community. This was favored by two additional factors: 1) the use of new electronic communication media, which gradually made the dissemination of research results much more dynamic and accessible, as opposed to the slower-moving and geographically-limited expansion in the initial period; and 2) the flourishing of TS in general, with the proliferation of academic programs including legal translation and the exponential increase in the number of researchers in LTS.

As the first and most comprehensive work of its kind in today’s lingua franca, Šarčević (1997) soon became a particularly influential landmark. Her contribution to the progress and internationalization of LTS was pivotal in that she integrated into her analysis new TS communicative theories, especially those by German-speaking scholars (such as Holz-Mänttäri, Reiss, Snell-Hornby, Vermeer or Wilss), as well as several contexts of translation not bound to any single language pair. As Šarčević (2000: 329) put it herself, “by analyzing legal translation as an act of communication in the mechanism of law,” she attempted “to provide a theoretical basis for legal translation within the framework of modern translation theory.” However, Šarčević (1997: 18-19; 2000: 331-332) remained critical of the universal applicability of Vermeer’s skopos theory to legal translation. It was the next generation of researchers that tested and fully embraced functionalist theories, particularly Nord’s version of skopos theory (Nord 1991a, 1991b, 1997), as a useful general framework in LTS (for example, Prieto Ramos 1998 and 2002, Dullion 2000, Garzone 2000). Equally receptive to these theories, Peter Sandrini and Roberto Mayoral Asensio should also be mentioned as major proponents of LTS applied research in the German-speaking countries and in the Spanish context over the same period, especially for their work on comparative analysis of legal terminology (Sandrini 1996a, 1996b) and the translation of official documents (Mayoral Asensio 2003).

Another milestone of that period was the international conference “Legal Translation: History, Theory/ies, Practice” held at the University of Geneva in February 2000. Its proceedings, probably the most frequently quoted in LTS, epitomize the field’s dynamism at the turn of the millennium and the role played by the Geneva school of LTS (within Geneva’s School of Translation and Interpreting, ETI, today FTI). As noted by Bocquet (2000: 17), legal translation had been ETI’s main pole of excellence in translation since its foundation, and a communicative approach (“la méthode communicative axée sur le produit de traduction,” as described in Bocquet 1996) had been applied there in previous decades. This is not surprising considering that: 1) the debate on the spirit versus the letter of the law had originated in multilingual Switzerland at the beginning of the 20th century (that is, even earlier than in Canada), in the context of the translation of the Swiss Civil Code from German into the other national languages (see thorough analysis by Dullion 2007); and 2) ETI’s programs had been designed to respond not only to the needs of national institutions but also, crucially, to those of Geneva-based international organizations, some of whose professionals also contributed to training in various language combinations.[8] This multidimensional orientation continues to shape the Geneva school of LTS as strongly pragmatic (with emphasis on improving models for practice on the basis of professional evidence)[9] and inclusive (of multiple influences, target languages and purposes, including a prominent institutional component and a long-standing combination of translation and legal expertise in training and research).

In the “catalytic period” reviewed, the Geneva school was a key player in advocating LTS’s specific approaches and denominations “traductologie juridique” and “juritraductologie” (see, for example, Bocquet 1994 and Abdel Hadi 2002), and established itself as an academic crucible in the field. The leading figure of the Canadian school, Jean-Claude Gémar, joined the ETI in 1997 and took part in the creation of the GREJUT[10] research group on legal translation with Claude Bocquet and Maher Abdel Hadi a year later. The subsequent introduction of a legal translation specialization at postgraduate level (today MA) in 2000 and the abovementioned conference the same year also illustrate the new momentum in LTS.

Since the mid-2000s, a growing constellation of researchers have continued to expand the interdiscipline by applying cross-cultural paradigms to different branches of law, legal genres and settings in many jurisdictions and languages, and by broadening cross-cutting topics, such as specific competence models, pedagogical issues, or the use of corpora and new resources in legal translation (for example, Biel 2010). While computer-assisted translation tools have attracted growing attention in the context of the “technological turn,” machine translation in particular has not been a primary focus in LTS. This does not seem surprising in a field in which the complex layers of system-bound legal meaning and interpretation make automatic semantic processing a real challenge (see, for example, Hoefler and Bünzli 2010) for the machine production of usable drafts. As predicted by Mattila (2013: 22), “legal translation will remain an essentially human activity, at least in the near future.” Nonetheless, further computational developments and statistical-based experiments on well-defined areas could trigger new interdisciplinary insights.

More interestingly, the relationship between legal translation and comparative law is being further advanced from an LTS perspective (see, for example, Engberg 2013 and Pommer 2014), while legal experts such as Ost (2009) and Glanert (2011) have recently acknowledged the new status of TS and the relevance of its paradigms in studying processes of legal convergence. If we adopt Kaindl’s (1999) model of analysis of interdisciplinary development of TS in general, the increasing dialogue between LTS scholars and comparatists can even be regarded as a symptom of transition from LTS’s “importing stage” of development to one of more “reciprocal cooperation” on issues of shared interest.

The academic self-confidence gained by LTS internationally is also apparent in scholars’ perceptions of its autonomy. The following definitions illustrate the evolution: “Far from being recognized as an independent discipline, legal translation is regarded by translation theorists merely as one of the many subject areas of special-purpose translation, a branch of translation studies” (Šarčević 1997: 1); “La traducción jurídica, una disciplina situada entre el derecho comparado y la lingüística contrastiva” (Arntz 2000: 376); “La juritraductologie est une nouvelle discipline qui cherche à déterminer les règles méthodologiques applicables à la traduction juridique” (Abdel Hadi 2002: 71); “La traductologie juridique est un sous-ensemble de la traductologie au sens large,” “un domaine encore balbutiant” (Pelage 2003: 109, 118); “The debate on the relationship between Legal Translation Studies and the overarching discipline of Translation Studies is still in its infancy, with positions varying according to the degree of specificity or commonality ascribed to the new discipline” (Megale 2008: 11) (translated by the author);[11] “legal translation studies is an interdiscipline which is situated on the interface between translation studies, linguistics, terminology, comparative law, and cultural studies” (Biel 2010: 6).

The intensification of scholarly work in LTS is reaching areas where the impact of previous academic advances has been more limited to date. At the same time, the impressive number of voices and publications on LTS has brought a certain sense of dispersion, which is compounded by the (paradoxically) insufficient communication still persistent between LTS researchers in different languages (Monzó Nebot 2010: 355) in spite of increasing internationalization since the mid-1990s.

5. Conclusions and perspectives

The remarkable expansion of LTS in the past three decades explains the keen interest in stocktaking that has motivated this paper. A review of the field’s development has led to the identification of three historical periods: 1) an initial stage of transition from traditional translation theories since the late 1970s, mostly marked by legal linguistic approaches and the Canadian school of Jurilinguistics; 2) a catalytic stage between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s in which LTS’s conceptual paradigms were solidified under the influence of cultural theories in TS; and 3) the current period of consolidation and expansion, dominated so far by a strong emphasis on applied research and multiple ramifications on the basis of LTS’s own theories.

Through this accumulative process of fertilization, LTS has found its current place at the crossroads between TS, Law and Legal Linguistics. The intersection between linguistic and legal analysis for translation has been a research continuum and a driving feature in that process of fertilization, reshaped by the assimilation of new TS approaches. Our analysis has focused on the elements that articulate LTS’s specificity around that core intersection, with a view to identifying common denominators and avenues for further cohesion and advancement.

1) Since LTS is concerned with all aspects of legal translation as object of study, the definition of its scope relies on our ability to characterize legal texts. The complementary nature of various classifications has been highlighted and a conciliatory approach proposed in which the combination of legal functions, themes and discursive situations serves to determine the legal nature of a text and to cluster linguistic features by text types and genres. This multidimensional categorization, permeable as it must remain to the dynamic and hybrid reality of texts and discourses, provides predictable criteria to outline the scope of legal translation and to avoid questionable generalizations on it.

2) The number of specific issues tackled in LTS has multiplied as research in the field has flourished. Legal translation theories are being applied to multiple corpora of legal texts and mediation contexts around the world, and there is still much to be done in order to shed light on specific genres and translation problems at both national and international levels. Although this might cause some overlaps and a certain sense of fragmentation, such studies are essential to stimulate good practices and further research on existing problems and emerging needs, as apparent in the multiple training, sociological or technological issues being addressed in LTS.

3) Among those challenges, the development of specific methods continues to be of critical importance to disciplinary specificity. Most approaches converge on the need to integrate legal theories and comparative legal analysis into legal translation methodology as a hallmark of the field. Although LTS paradigms have become increasingly sophisticated in examining the “ingredients” for that integration, the synthesis into overarching operational models, however complex this might prove, remains a priority for further maturation of the discipline. As noted by Munday (2001: 188) in relation to TS in general, one of the traditional difficulties in “the construction of an interdisciplinary methodology” is “the necessary expertise in a wide range of subject areas” whereas “the original academic background of the individual researcher inevitably conditions the focus of their approach.” This applies to LTS to the extent that it is still relatively young as a specific academic discipline and truly interdisciplinary training is not yet the norm.

An additional difficulty in building universally-valid methodological models in LTS is the enormous variability of situational factors in legal translation, which explains the limited applicability of many theoretical frameworks, already pointed out by Garzone (2000: 395): “so far most studies have had their starting point in a specific experience in one area of this very broad field, so that the theoretical concepts proposed, however viable, have tended to be all but comprehensive in their scope of application.” Against this backdrop, and given the shared pursuit of “adequacy” in varied communicative situations, modern functionalist considerations have become widely accepted in LTS, even if to different degrees.

4) As regards scholars’ perceptions of common markers of disciplinary identity and development, their metadiscourse shows a constant progression from more hesitant to more self-confident views on LTS’s status as a subdiscipline or interdiscipline within TS. Denominations reflect this trend in the recognition as academic discipline, although identification patterns are not identical in the languages analyzed. In this respect, further consistency in the use of distinct terminology to refer to the discipline (“Legal Translation Studies,” “traductologie juridique,” “Traductología Jurídica”) can only contribute to strengthening its cohesion.

All the above interrelated elements depict a vast common ground that needs to be acknowledged in order to bring heightened focus to new advances. LTS stands today as a maturing discipline whose thematic body resembles that of Law, with specific issues addressed on different “legal textual branches” at national and supranational levels, and it continues to expand through its interaction with other disciplines. Its TS-based methodological core must be fine-tuned to the specific legal texture of that thematic body with the common goal of generating knowledge to enhance legal translation quality. In a context of rapid expansion, it is indeed worth ensuring that research on legal translation methodology progresses by keeping the forest, and not just its trees, in sight.

Such research on professional problem-solving fits a paradigm in which observation and experimentation yield results for improving the observed practice. It is no coincidence that LTS blossomed earliest in countries or regions where the professionalization of translation, and the concomitant institutional concern with translation quality, stimulated research and training in the field. In the case of the Geneva school of LTS (today under its Centre for Legal and Institutional Translation Studies, Transius), emphasis remains on methodology as a fundamental bridge between theory and practice. In line with this school’s pragmatic and inclusive tradition, holistic approaches are advocated in which legal and discursive parameters of contextualization of legal translation are integrated, systematized and put to work in decision-making and competence-building (Prieto Ramos 2011, 2014; Dullion 2014) as the basis for testing applicability and impact on translation quality. This cycle of integration, systematization and testing starts with observation of methodological gaps in practice and consideration of professional requirements in diverse contexts (for an updated overview, see Borja Albi and Prieto Ramos 2013).

From this perspective, LTS scholars should not only be up-to-date with quality standards in the translation settings investigated but also contribute to raising those standards through research and training based on solid empirical foundations. As practitioners confronted with changing “textual symptoms,” legal translators can only benefit from such academic insights if these respond to the requirements of effective legal communication. In turn, this implies embracing the multifaceted nature of legal translation and determining its purpose under each set of communicative conditions, rather than adopting oversimplistic or static conceptions. Only by building on this kind of empowering vision and proving its practical benefits can LTS reinforce the true relevance of its specificity within and beyond academia, and thereby enhance both disciplinary and professional recognition.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Throughout this article, some quotations are provided in French and Spanish (the other two official languages of the journal) that are not translated for the sake of brevity.

-

[2]

Even nowadays, some authors claim that legal translation is limited to normative texts or texts that “regulate relations.” For example, for Ferran Larraz (2012. 345), legal translation is “la traslación de los efectos jurídicos esenciales del documento, en tanto que [sic] su finalidad es siempre cumplir una función social mediante la regulación de comportamientos.”

-

[3]

The figure focuses on primary disciplinary relations and intersections relevant to LTS. Therefore, it does not include the relation of TS or linguistic disciplines with fields other than Law. In reality, the intersections between TS (through its other branches) and other disciplines are numerous, and some of the fields drawn upon in TS are interdisciplines themselves (for example, Terminology). Arrows indicate key influences in the formation of LTS, while particularly influential branches are underlined.

-

[4]

According to Termium, the Government of Canada’s terminology and linguistic data bank, the term actually derives from “jurilinguiste,” used in the late 1970s by Alexandre Covacs, then in charge of French language services at the Legislation Section of Canada’s Department of Justice. He referred to “jurilinguistes” (translated as “jurilinguists”) and a “groupe de jurilinguistique française” within his Section (Covacs 1982: 98, based on a paper presented at a conference in 1980). However, it is Jean-Claude Gémar who first defined the term and has led scholarly work on the subject on the basis of the Canadian experience.

-

[5]

A decade later, in an overview of the field, Gémar described Jurilinguistics as “avant tout un savoir-faire personnel qui a évolué en pratique professionnelle” (2005. 5. and as a “field of endeavor” which had taken shape “in the wake of translation” and “transcends linguistic barriers and legal traditions” (2005. 2).

-

[6]

Trends on denominations mentioned in this section have been confirmed through quantitative and qualitative analysis of results of online searches carried out between October 2009 and January 2013.

-

[7]

“Legilinguistics” is used as a synonym at the Adam Mickiewicz University’s Institute of Linguistics in Poznan, Poland (for example, in the Comparative Legilinguistics journal), where the term was coined.

-

[8]

Translation was thus conceived as “le support d’un dialogue interculturel, interinstitutionnel et international” (Bocquet 1996: 72). On the distinctive features of the Geneva School tradition of training and theory-building in legal translation, see also Bocquet (1996: 70-74, 2008. 77-79).

-

[9]

On the “evidence-based approach to applied translation studies” in general, see Ulrych (2002).

-

[10]

Groupe de recherche en Jurilinguistique et Traduction.

-

[11]

“Si trova invece ancora agli inizi la discussione sui rapporti fra la traduttologia giuridica e il genus traduttologia, con posizioni che oscillano in base al grado di specificità o di comunanza che gli uni e gli altri assegnano alla nuova” (Megale 2008: 11).

Bibliography

- Abdel Hadi, Maher (1992): Géographie politique et traduction juridique, le problème de la terminologie. Terminologie et traduction. 2/3:43-57.

- Abdel Hadi, Maher (2002): La juritraductologie et le problème des équivalences des notions juridiques en droit des pays arabes. Les Cahiers de l’ILCEA. 3:71-78.

- Alcaraz Varó, Enrique and Hughes, Brian (2002): Legal Translation Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Arntz, Reiner (2000): La traducción jurídica, una disciplina situada entre el derecho comparado y la lingüística contrastiva. Revista de lenguas para fines específicos. 7/8:376-399.

- Biel, Łucja (2010): Corpus-Based Studies of Legal Language for Translation Purposes: Methodological and Practical Potential. In: Carmen Heine and Jan Engberg, eds. Reconceptualizing LSP. Online proceedings of the XVII European LSP Symposium 2009. (Aarhus, Denmark, 17-21 August 2009). Visited on 10 October 2012, http://bcom.au.dk/fileadmin/www.asb.dk/isek/biel.pdf.

- Bocquet, Claude (1994): Pour une méthode de traduction juridique. Prilly/Lausanne: Éditions C. B.

- Bocquet, Claude (1996): Traduction spécialisée: choix théorique et choix pragmatique. L’exemple de la traduction juridique dans l’aire francophone. Parallèles. 18:67-76.

- Bocquet, Claude (2000): Traduction juridique et appropriation par le traducteur. L’affaire Zachariae, Aubry et Rau. In: La traduction juridique: Histoire, théorie(s) et pratique / Legal Translation: History, Theory/ies, Practice. (Proceedings, Geneva, 17-19 February 2000). Bern/Geneva: ASTTI/ETI, 15-35.

- Bocquet, Claude (2008): La traduction juridique: fondement et méthode. Brussels: De Boeck.

- Borja Albi, Anabel (2000): El texto jurídico inglés y su traducción al español. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Borja Albi, Anabel and Prieto Ramos, Fernando, eds. (2013): Legal Translation in Context: Professional Issues and Prospects. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Brand, Oliver (2007): Conceptual Comparisons: Towards a Coherent Methodology of Comparative Legal Studies. Brooklyn Journal of International Law. 32(2):405-466.

- Brems, Elke, Meylaerts, Reine and van Doorslaer, Luc (2012): A discipline looking back and looking forward: An introduction. Target. 24(1):1-14.

- Cacciaguidi-Fahy, Sophie, ed. (2008): La linguistique juridique ou jurilinguistique: Hommage à Gérard Cornu. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. 21(4):311-384.

- Cao, Deborah (2007): Translating Law. Clevedon/Buffalo/Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

- Chesterman, Andrew (2002): On the Interdisciplinarity of Translation Studies. Logos and Language. 3(1):1-9.

- Covacs, Alexandre (1982): La réalisation de la version française des lois fédérales du Canada. In: Jean-Claude Gémar, ed. Langage du droit et traduction: Essais de jurilinguistique / The Language of the Law and Translation: Essays on Jurilinguistics. Montreal: Linguatech/Conseil de la langue française, 83-100.

- Cronin, Michael (2010): The Translation Crowd. Revista Tradumàtica. 8. Visited on 23 August 2012, http://www.fti.uab.es/tradumatica/revista/num8/articles/04/04art.htm.

- De Groot, Gérard-René (1987): The point of view of a comparative lawyer. Les Cahiers de droit. 28(4):793-812.

- De Groot, Gérard-René (2012): The Influence of Problems of Legal Translation on Comparative Law Research. In: Cornelis J. W. BAAIJ, ed. The Role of Legal Translation in Legal Harmonization. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International, 139-159.

- Dogan, Mattei (1997a): ¿Interdisciplinas? Revista Relaciones. 157:16-18.

- Dogan, Mattei (1997b): The New Social Sciences: Cracks in the Disciplinary Walls. International Social Science Journal. 49(153):429-443.

- Dullion, Valérie (2000): Du document à l’instrument: les fonctions de la traduction des lois. In: La traduction juridique: Histoire, théorie(s) et pratique / Legal Translation: History, Theory/ies, Practice. (Proceedings, Geneva, 17-19 February 2000). Bern/Geneva: ASTTI/ETI, 83-101.

- Dullion, Valérie (2007): Traduire les lois: un éclairage culturel. La traduction en français des codes civils allemand et suisse autour de 1900. Cortil-Wodon: Éditions Modulaires Européennes.

- Dullion, Valérie (2014): Droit comparé pour traducteurs: de la théorie à la didactique de la traduction juridique. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. Visited on 5 February 2014, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11196-014-9360-2.

- Engberg, Jan (2013): Comparative Law for Translation: The Key to Successful Mediation between Legal Systems. In: Anabel Borja Albi and Fernando Prieto Ramos, eds. Legal Translation in Context: Professional Issues and Prospects. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 9-25.

- Ferran Larraz, Elena (2012): El estudio de las marcas jurídico-discursivas del acto jurídico en el documento negocial: una estrategia para la traducción jurídica de documentos Common Law. Quaderns. Revista de Traducció. 19:341-364.

- Garzone, Giuliana (2000): Legal Translation and Functionalist Approaches: a Contradiction in Terms? In: La traduction juridique: Histoire, théorie(s) et pratique / Legal Translation: History, Theory/ies, Practice. (Proceedings, Geneva, 17-19 February 2000). Bern/Geneva: ASTTI/ETI, 395-414.

- Gémar, Jean-Claude (1979): La traduction juridique et son enseignement: aspects théoriques et pratiques. Meta. 24(1):35-53.

- Gémar, Jean-Claude (1982): Fonctions de la traduction juridique en milieu bilingue et langage du droit au Canada. In: Jean-Claude Gémar, ed. Langage du droit et traduction: Essais de jurilinguistique / The Language of the Law and Translation: Essays on Jurilinguistics. Montreal: Linguatech/Conseil de la langue française, 121-137.

- Gémar, Jean-Claude (1995): Traduire ou l’art d’interpréter. Tome I: Principes. Fonctions, statut et esthétique de la traduction. Tome II: Application. Langue, droit et société: éléments de jurilinguistique. Sainte-Foy: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Gémar, Jean-Claude (2005): De la traduction (juridique) à la jurilinguistique. Fonctions proactives du traductologue. Meta. 50(4):2-10.

- Gémar, Jean-Claude (2013): Translating vs Co-Drafting Law in Multilingual Countries: Beyond the Canadian Odyssey. In: Anabel Borja Albi and Fernando Prieto Ramos, eds. Legal Translation in Context:Professional Issues and Prospects. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 155-178.

- Gentzler, Edwin (2003): Interdisciplinary connections. Perspectives. 11(1):11-24.

- Glanert, Simone (2011): De la traductibilité du droit. Paris: Dalloz.

- Harvey, Malcolm (2002): What is so special about legal translation? Meta. 47(2):177-185.

- Hoefler, Stefan and Bünzli, Alexandra (2010): Controlling the language of statutes and regulations for semantic processing. In: Proceedings of SPLeT 2010: The 3rd Workshop on Semantic Processing of Legal Texts. (Valletta, Malta, 23 May 2010). Visited on 10 October 2012, https://files.ifi.uzh.ch/hoefler/hoeflerbuenzli2010splet.pdf.

- Holmes, James S. (1972/1988): The Name and Nature of Translation Studies. In: James S. Holmes, Translated!: Papers on Literary Translation and Translation Studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 67-80.

- Kaindl, Klaus (1999): Interdisziplinarität in der Translationswissenschaft: Theoretische und methodische Implikationen. In: Alberto Gil, Johann Haller, Erich Steineret al., eds. Modelle der Translation: Grundlagen für Methodik, Bewertung, Computermodellierung. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 137-155.

- Maley, Yon (1994): The Language of the Law. In: John Gibbons, ed. Language and the Law. London/New York: Longman, 11-50.

- Mattila, Heikki E. S. (2013): Comparative Legal Linguistics. 2nd ed. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- MayoralAsensio, Roberto (2002): ¿Cómo se hace la traducción jurídica? Puentes. 2:9-14.

- MayoralAsensio, Roberto (2003): Translating Official Documents. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- McCarty Willard (1999): Humanities Computing as Interdiscipline. Visited on 23 August 2012, http://www.iath.virginia.edu/hcs/mccarty.html.

- Megale, Fabrizio (2008): Teorie della traduzione giuridica. Fra diritto comparato e «Translation Studies». Napoli: Editoriale scientifica.

- Monzó Nebot, Esther (2010): E-lectra: A Bibliography for the Study and Practice of Legal, Court and Official Translation and Interpreting. Meta. 55(2):355-373.

- Munday, Jeremy (2001): Introducing Translation Studies. London: Routledge.

- Nord, Christiane (1991a): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi.

- Nord, Christiane (1991b): Scopos, Loyalty, and Translational Conventions. Target. 3(1):91-109.

- Nord, Christiane (1997): Translating as a Purposeful Activity. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Ost, François (2009): Le droit comme traduction. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval.

- Pelage, Jacques (2003): La traductologie juridique: contours et contenus d’une spécialité. Traduire. 200:109-119.

- Pigeon, Louis-Philippe (1982): La traduction juridique - L’équivalence fonctionnelle. In: Jean-Claude Gémar, ed. Langage du droit et traduction: Essais de jurilinguistique / The Language of the Law and Translation: Essays on Jurilinguistics. Montreal: Linguatech/Conseil de la langue française, 271-281.

- Pommer, Sieglinde (2014): Law as Translation. The Hague/London/Boston: Kluwer Law International.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando (1998): La terminología procesal en la traducción de citaciones judiciales españolas al inglés. Sendebar. 9:115-135.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando (2002): Beyond the Confines of Literality: A Functionalist Approach to the Sworn Translation of Legal Documents. Puentes.Hacia nuevas investigaciones en la mediación intercultural. 2:27-35.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando (2011): Developing Legal Translation Competence: An Integrative Process-Oriented Approach. Comparative Legilinguistics. 5:7-21.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando (2014): Parameters for Problem-Solving in Legal Translation: Implications for Legal Lexicography and Institutional Terminology Management. In: Anne Wagner, King-Kui Sin and Le Cheng, eds. The Ashgate Handbook of Legal Translation. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Sacco, Roberto (1992): Introduzione al diritto comparato. 5th ed. Turin: UTET.

- Sandrini, Peter (1996a): Comparative Analysis of Legal Terms: Equivalence Revisited. In: Christian Galinski and Klaus-Dirk Schmitz, eds. Terminology and Knowledge Engineering (TKE ‘96). Frankfurt am Main: Indeks, 342-351.

- Sandrini, Peter (1996b): Terminologiearbeit im Recht. Deskriptiver begriffsorientierter Ansatz vom Standpunkt des Übersetzers. Vienna: TermNet.

- Šarčević, Susan (1985): Translation of Culture-Bound Terms in Laws. Multilingua. 4(3):127-133.

- Šarčević, Susan (1997): New Approach to Legal Translation. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

- Šarčević, Susan (2000): Legal Translation and Translation Theory: A Receiver-Oriented Approach. In: La traduction juridique: Histoire, théorie(s) et pratique / Legal Translation: History, Theory/ies, Practice. (Proceedings, Geneva, 17-19 February 2000). Bern/Geneva: ASTTI/ETI, 329-347.

- Snell-Hornby, Mary (2006): The Turns of Translation Studies: New Paradigms or Shifting Viewpoints? Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Sparer, Michel (1979): Pour une dimension culturelle de la traduction juridique. Meta. 24(1):68-94.

- Ulrych, Margherita (2002): An evidence-based approach to applied translation studies. In: Alessandra Riccardi, ed. Translation Studies: Perspectives on an Emerging Discipline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 198-213.

- Vanderlinden, Jacques (1995): Comparer les droits. Diegem: E. Story-Scientia.

- Weston, Martin (1991): An English Reader’s Guide to the French Legal System. Providence/Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Disciplinary boundaries of LTS[3]

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Categorization of legal texts

10.7202/002870ar

10.7202/002870ar