Résumés

Abstract

In Spain, the growing number of films depicting characters in multicultural settings bears testimony to the demographic changes experienced by Spanish society since the late 1980s. From a translational point of view, these films attract attention of researchers because of the presence of immigrant characters that use their mother tongue in addition to the language(s) of their host society. In this paper we present the results of the second stage of a research on the linguistic diversity in Spanish films starring immigrants. While the first stage dealt with the original audiovisual texts, we focus on their subtitled versions in two European languages. To do so, a descriptive and empirical methodology has been followed, the first step of which was the creation of a thorough corpus of six Spanish films and their corresponding eight target versions (in English and French). The descriptive and microtextual analysis of the immigrants’ dialogues found in our corpus allows us to define the translation strategies and techniques employed by subtitlers. Then, these techniques are classified in a continuum according to their degree of domestication and foreignisation. Finally, some conclusions are drawn regarding the ideology behind the cinematographic reflection of immigrants’ foreignness.

Keywords:

- subtitling,

- plurilingualism,

- polyglot cinema,

- immigration films,

- ideology

Résumé

Depuis la fin des années 1980, le cinéma espagnol a été enrichi d’un nombre croissant de films mettant en scène des personnages dans un cadre multiculturel, ce qui témoigne des changements démographiques que la société espagnole a subis au cours des dernières décennies. D’un point de vue traductionnel, ces films ont attiré l’attention des chercheurs, car ils mettent en scène des personnages immigrants qui utilisent non seulement la langue (ou les langues) de leur société d’accueil, mais aussi leur langue maternelle. Le présent article fait état des résultats de la deuxième phase d’une étude portant sur la diversité linguistique se manifestant dans des films espagnols dont le rôle principal est joué par des immigrants. Tandis que la première phase se penchait sur les textes audiovisuels originaux, nous analysons ici les versions sous-titrées dans deux langues européennes. Pour ce faire, nous avons employé une méthodologie descriptive et empirique dont le premier objectif a été la création d’un corpus composé de six films espagnols avec leurs huit versions en langue cible (anglais et français). L’analyse descriptive et micro-textuelle des dialogues joués par des immigrants nous a permis de définir les stratégies et les techniques de traduction mises en jeu par les sous-titreurs. Ensuite, ces techniques ont été classées dans un continuum en fonction de leur degré de naturalisation et d’étrangéisation. Nous tirons enfin quelques conclusions sur l’idéologie derrière la réflexion cinématographique relative à la condition d’étranger des immigrants.

Mots-clés :

- sous-titrage,

- plurilinguisme,

- cinéma polyglotte,

- films d’immigration,

- idéologie

Corps de l’article

1. Background

Cinema is an art form that relentlessly explores social changes and the concerns they give rise to. The global phenomenon of immigration is one of the latest issues to be addressed by it. The number of films produced over recent decades depicting characters in multi-cultural settings bears testimony to these demographic changes which are re-shaping contemporary societies. From a sociolinguistic and translational point of view, these films are made interesting by the presence of immigrant characters who use their mother tongue in addition to the language(s) of their host society (for a complete discussion on multilingualism in fiction, see Bleichenbacher 2008). This willingness to present hybrid characters in multicultural settings has led to the emergence of a genre known as polyglot films, in which for the first time, plurilingualism appears as “a discrete mode of narrative and aesthetic expression” (Wahl 2008: 349). Spanish cinema is not an exception to this trend, and the growing presence of plurilingualism reflects the deep impact immigration has had on Spanish society since the late 1980s.

This scenario was the starting point for an article which described how plurilingualism is dealt with by Spanish cinema (Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. 2010). The article focused on 11 films[1] featuring immigrant characters and released in DVD format over the past two decades (1989-2008). Most of these films belong to the above-mentioned polyglot genre (Dwyer 2005, Wahl 2008), a kind of cinema that “respects the cultural ‘aura’ and the individual voices of the actors” and “delivers on a verbal level a naturalistic depiction of the characters” (Wahl 2008: 338). Rather than focusing on the dubbing and subtitling of these films – the latter being the main objective of the present article –, the aims of Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. (2010) were to determine whether or not immigrants’ languages are translated in the original version and to identify the various strategies by which these languages are conveyed to Spanish speaking audiences. The strategies identified were the following: self-translation, liaison interpreting, subtitling and no-translation. Additionally, in these films immigrants also speak Spanish, either standard Spanish or non-standard immigrant Spanish (see below).

The results of the research were twofold: concerning text selection, the number of Spanish films containing immigrant characters did not show a clear upward trend in the period studied (1989-2008). The data invalidated the hypothesis according to which this kind of films would be more common nowadays than ten or twenty years ago. However, the percentage of these films released in DVD format (70%) did indicate a growing interest in this subgenre in the home entertainment market. Concerning the filmmakers’ decisions on how to depict the immigrants’ dialogues, the results of the above mentioned research pointed to a broad use of 1) non-standard immigrant Spanish – the source dominant language with poor syntax and phonetic interference – and 2) their own language with no translation for the Spanish audience; two opposing options from the point of view of linguistic inclusion. The rest of categories were less used.

Linguistic Diversity in Spanish Immigration Films was conceived as a first stage in the study of the strategies used to handle translational problems posed by plurilingualism in original films. Building upon it, the present paper shifts the focus from the original audiovisual texts to their subtitling into two European languages. Dialogues featuring immigrant characters speaking L3 (see below) in the target texts remain the specific objects of study. The translation strategies and techniques found in these subtitled versions will be analysed using a descriptive approach.[2] We hope that this new case study will provide a broader picture of the translation strategies and techniques followed by European audiovisual translators when confronted with the issues posed by polyglot films.

2. Translation Strategies and Techniques

This paper focuses on translation strategies and techniques, regardless of the specific languages involved. Following Corrius (2008), we will use the abbreviations L1 to refer to the original language of the films – namely, Spanish; L2 when referring to the dominant language used in each translated version – specifically, French and English; and L3 to designate any other language spoken by immigrants usually as their mother tongue.

In this second phase of research, we adopt Molina and Hurtado’s terminology (2002), which we find useful for this kind of analysis. Hurtado (1996 and 1999) distinguishes between translation strategy and technique: the former consists in “the procedures (conscious or unconscious, verbal or nonverbal) used by the translator to solve problems that emerge when carrying out the translation process with a particular objective in mind” (quoted in Molina and Hurtado 2002: 508). Examples of translation strategies are: paraphrasing, retranslating, establishing conceptual relationships, etc. Translation techniques on the other hand are “procedures to analyse and classify how translation equivalence works” (Molina and Hurtado 2002: 509), such as adaptation, amplification, calque, compensation, etc. In a nutshell, “[s]trategies open the way to finding a suitable solution for a translation unit. The solution will be materialized by using a particular technique” (Molina and Hurtado 2002: 508).

As will be seen in the next subsections, in the case of the translation of multilingual films, we also distinguish between strategies and techniques. We propose our own taxonomy because each translation problem requires a specific typology of translation techniques based on its specific features and constraints (Marco 2004). Bartoll (2006) points out that in dealing with plurilingual films the translator chooses between two translation strategies for conveying language diversity: either to mark the presence of foreign languages in the source version or not to mark it. Once this decision has been taken, the subtitler selects the techniques with which to convey the content of those dialogues to the target audience – coloured subtitles, italics, no-translation, etc.

2.1. Original Films

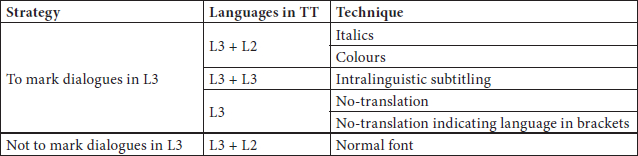

According to Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. (2010), immigrants’ dialogues in Spanish films may be conveyed to the Spanish audience as presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Translation techniques in the original version (adapted from Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. 2010)

Although the choice of language spoken by immigrants may be ideologically and socially significant, it is not the subject matter of this paper and we will not dwell on it.

2.2. Subtitled Films

In this paper we will study the subtitled versions of the Spanish films listed in section 4. We consider the different techniques used to translate plurilingual dialogues, as described in the literature on subtitling. Bartoll (2006) analyses subtitled multilingual films and proposes the following solutions to convey multilingual dialogue lines, some of which are taken from Subtitling for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing studies. Firstly, translators might reflect on which translation strategy to choose. In the case of plurilingual films, they can decide whether or not to mark the use of (a) different language(s) within the film in the subtitles themselves. Each translation strategy materialises into a particular translation technique. If subtitlers decide language diversity should go unnoticed, then the dialogue is subtitled solely into the target language with no indicator showing the use of different languages. If on the contrary, they decide to mark the use of a different language, they can choose one of the following techniques: not to translate it, to transcribe it (intralinguistic subtitling) or to use italics in the subtitles. Finally, to mark the use of more than two languages, there are two solutions: not translating them while indicating the language in brackets, or subtitling the text using different colours.

Agost (2000) also deals with the subtitling of third languages, but she only describes two possibilities: 1) the subtitling of all dialogues – regardless of the language, or 2) the subtitling of the main language of the text plus the no-translation of the foreign language.

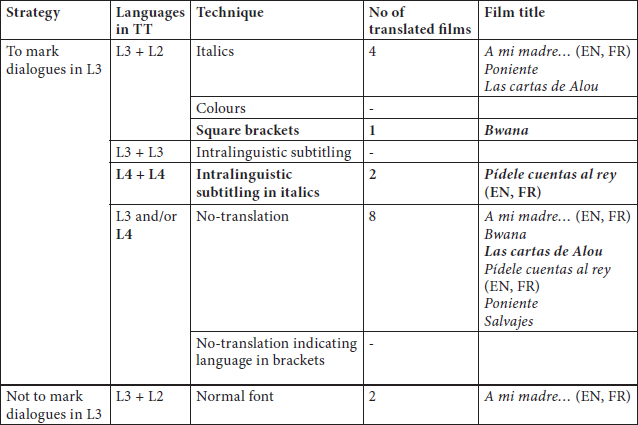

Table 2 is an attempt to summarise Bartoll’s model, while including additional techniques. For the sake of a better comprehension, we use L3 + L2 to show that, in the subtitled film, the original dialogues are in the immigrant’s language and the subtitles are in the target languages – this is, French or English. L3 + L3 means that the original dialogues are in the inmigrant’s language and the subtitles are in the immigrant’s language too. Finally, L3 means that the original dialogues are in the immigrant’s language and there is no translation whatsoever.

Table 2

Model of analysis for the subtitled versions

In the analysis section below, we will provide a definition of each technique and illustrate it with some examples from our corpus. This will allow us to determine the strategies and techniques used to translate immigrant dialogues in the subtitled versions of the Spanish multilingual films analysed.

3. Methodology, Aims and Hypotheses

In this paper empirical analysis centres on sample identification. Whenever immigrant characters appear speaking their mother tongue, the language selection and translation technique are recorded. This methodology allows for hypotheses testing and facilitates the development of a taxonomy of translation techniques, thus allowing research goals to be met. Our main objective is to explore the extent to which the subtitled versions of these films reflect linguistic diversity. How are linguistically complex situations reflected? What strategies and techniques are employed to do so?

Our first hypothesis could be formulated as follows: the strategies and techniques presented by Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. (2010), Corrius (2008) and Bartoll (2006) will be detected in the examples contained in the selected corpus. Nevertheless, we also hypothesise that new categories will be identified.

Our objective, therefore, is not to consider language pairs or differences between audiovisual translation modes yet, but rather to focus on the subtitling of immigrant L3 speech. To this end, and taking prior research (see previous paragraph), a taxonomy of translation strategies and techniques has been developed (Table 2).

In the initial stage the total population of Spanish films released from 1989 onwards was quantified (excluding co-productions, documentaries and animation films).[4] A second filter was applied to this list, namely, that only films in Spanish language with a plot containing immigrant characters would be analysed. A final filter was introduced referring to the format: for practical purposes, only films available in DVD were considered. Thus, a corpus of 11 films was established. For our current purposes, a further filter has been used: only films that include a third language and have been subtitled into other languages are considered. As a result, a corpus of six films has been created; it is presented in the next section.

4. Corpus

The corpus created for this study consists of six Spanish fiction films released during the 1989-2008 period and then translated into other languages (Table 3). These films contain some dialogue by non-Spanish-speaking immigrant characters.[5] The catalogue of Spanish-only fictional productions in this twenty-year period amounts to 863,[6] of which we were left with a mere six after applying our various filters. Thus, ours can be considered a case study which offers a preliminary survey of plurilingual movies in the Spanish film industry.

The films included in our corpus are presented in Table 3 (see also Note 1):

Table 3

Film corpus: source versions, DVD and target versions

5. Analytical Framework and Data Analysis

The analytical model employed for subtitled plurilingual films identifies six different translation techniques. We link the techniques to Venuti’s (1995) concepts of domestication and foreignisation (see Figure 1 below):

Figure 1

A continuum of translation techniques for subtitled plurilingual films

Upon viewing all six films (eight target texts) we found most of the techniques we described previously to be present; as well as others which had not been identified. In this section we include a definition and some examples of the different translation techniques found in the films.

5.1. Subtitles in Normal Font

Because of intrinsic characteristics of this translation mode, plurilingualism in the original film might be perceived by the target audience, but it might not be. The use of subtitles in normal font for translating immigrants speaking their native languages (L3) makes the coexistence of different languages in the original version go unnoticed to viewers of the subtitled versions.

In the English and French versions of A mi madre le gustan las mujeres, the use of subtitles in normal font to translate L3 dialogues in the original can be found when Eliska’s brother speaks Czech to one of the Spanish characters (Sol) at the end of the film, by the river Danube. Although he does not play the role of an immigrant – as he lives in his home country –, we have considered his dialogues in an L3 for our analysis because these scenes are in fact plurilingual.

5.2. Subtitles in Italics or Colours

Bartoll describes two possibilities for marking the presence of an L3 in subtitled versions of films: italics and colours. Although italics are conventionally used in subtitling to indicate off-screen voices, voices from within, distant voices, or voices heard through a machine – a narrator, interior monologues, a radio programme or a TV presenter –, in plurilingual films they may mark foreign language dialogues. A case in point is Poniente, subtitles appear in italics when immigrant characters use their native language. In the French subtitled version of A mi madre le gustan las mujeres, italics are also used to mark Czech language dialogues in the original version.[7] Among the films surveyed no instance of coloured subtitling was encountered.

It may be noted that in Bwana a new technique was discovered. In this case Ombasi’s native language is not translated (in either of the versions), except in the scene in which he dreams of his dead friend who tells him, in their unidentified mother tongue, not to trust white people. As the film unfolds, this message proves crucial to the story, and this is probably why it has been subtitled in both versions; that is, for narrative purposes. What is interesting here is that, in the English subtitled version, square brackets are used to mark the presence of L3.[8]

5.3. Intralinguistic Subtitling

Bartoll (2006) concludes that, in some cases, sentences in a different language are transcribed in order to mark its presence. We have decided to adopt the term intralinguistic translation, coined by Jakobson (1959), to classify the subtitles written in L3. An instance of this technique can be found in both versions of Pídele cuentas al rey. However, subtitles are not written in L3 as we had foreseen, but in what we have termed L4, a European language, other than Spanish, used by immigrants as a lingua franca. Jihad, the Moroccan immigrant, uses French and Italian to communicate with Fidel. In the English subtitled version, these words appear in italics, probably to mark the presence of a different language. This also occurs in the French subtitled version; although one of the words (Madame) is actually French and no translation whatsoever would have been needed.

5.4. No-translation indicating language in brackets

To mark the use of different languages, Bartoll (2006) suggests the inclusion of the name of the language at the beginning of the subtitle in brackets. No examples of this technique have been identified in the corpus.

5.5. No-translation

As defined earlier, no-translation consists in the absence of translation of L3 dialogues – in some cases this technique is used because no translation was provided in the original version. In Pídele cuentas al rey, when Fidel sees policemen arresting Sub-Saharan immigrants, they are heard speaking their own language(s), but no translation is provided in either version.

However, no-translation is also used when liaison interpreting or self-translation appear in some scenes of the films. The reason for this is that translation is not needed, as L3 sentences are instantly translated by the characters in the film; thus making subtitling of L3 redundant. In Las cartas de Alou, Moncef tells Alou an Arab proverb, but the latter is Senegalese and does not understand him; so Moncef translates his own words into Spanish. In the French version, no translation of the Arab proverb is offered, but Moncef’s subsequent explanation in Spanish is translated. In A mi madre le gustan las mujeres, some dialogues in Czech are not subtitled in a scene in which Eliska’s brother is interpreted by her when speaking to Sofía’s daughters.

In Salvajes, no-translation appears in cases in which liaison interpreting is present in the film. At one point Eduardo – the police inspector investigating Omar’s beating by a group of skinheads – interrogates Omar’s wife, who pretends not to speak Spanish, while their son acts as a liaison interpreter. In the English subtitled version, no-translation is provided for her statement, while the child’s words in Spanish are subtitled.

In Las cartas de Alou, English and French (L4) are used just after Alou’s arrival in Spain when he cannot communicate in any other language. These dialogue lines are not translated. The no-translation of French lines is understandable as the target text is actually the French subtitled version. In the case of English, it is not subtitled.

6. Results and Conclusions

6.1. Results

The analysis revealed some unexpected findings. In the case of dialogues in L3, only the English and French versions of A mi madre le gustan las mujeres include non-marked subtitles, but these are not consistent. This film, and most of the films analysed, contain techniques marking L3 in one way or another, no-translation being the most widely used technique. Whereas no instances of coloured subtitles were detected, our analysis revealed the use of square brackets (Bwana), a choice we had not found in the previous literature.

Finally, in our analysis we also took into account the use of an L4 by immigrants. Both versions of Pídele cuentas al rey resort to intralinguistic subtitling in italics to solve this translation problem, while Las cartas de Alou offers no translation in these cases.

The conclusions drawn from the analysis of subtitled versions are summarised in Table 4, new findings being highlighted in bold.

Table 4

Strategies and techniques found in the analysis of subtitled versions

There is a tendency to clearly mark the use of a third or fourth language in the source text. Thus, no-translation (eight target versions) is the dominant technique, followed by subtitling in italics (four target versions). Intralinguistic subtitling in italics appears in two target versions, while the least preferred technique is the use of square brackets. Two instances of normal subtitling were found. No instances of coloured subtitling, normal intralinguistic subtitling or notes indicating languages in brackets were detected.

However, these conclusions cannot be made extensive to the whole population of Spanish films, since further studies involving wider corpora would be needed to formulate a norm.

6.2. Conclusions

From all the above mentioned, we can conclude that, as to the filmmakers’ and subtitling agents’ will to portray the foreignness of immigrant characters, the predominant strategy is to mark the use of L3 and L4 through different techniques. This is probably the reason why no-translation – the most foreignising technique – is so widely used in the films analysed.

Besides, and despite the fact that subtitling is the predominant mode of audiovisual translation in the European DVD market, the variety of translation techniques found shows that no clear guidelines are followedto convey dialogues in plurilingual films.

Our two hypotheses have been validated. On the one hand, half of the techniques presented by Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. (2010), Corrius (2008) and Bartoll (2006) have been detected in the examples contained in the selected corpus: subtitling in italics, subtitling in normal font and no-translation. On the other hand, two new categories have been identified: subtitling in square brackets and intralinguistic subtitling in italics (of L4).

Consequently, the elaboration of quality standards that are suited to the role of the immigrant within films is sorely needed to put an end to this chaotic scenario. This will only be possible through the development of further interdisciplinary studies drawing from fields such as Sociology, Anthropology, Perception Studies and Intercultural Communication.

Parties annexes

Appendix

The specific volumes of Cine para leer consulted for this research are the following:

Equipo Reseña (1990): Cine para leer 1989. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1991): Cine para leer 1990. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1992): Cine para leer 1991. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1993): Cine para leer 1992. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1994): Cine para leer 1993. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1995): Cine para leer 1994. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1996): Cine para leer 1995. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1997): Cine para leer 1996. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1998): Cine para leer 1997. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (1999): Cine para leer 1998. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2000a): Cine para leer 1999. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2000b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2000. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2001a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2000. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2001b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2001. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2002a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2001. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2002b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2002. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2003a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2002. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2003b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2003. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2004a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2003. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2004b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2004. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2005a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2004. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2005b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2005. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2006a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2005. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2006b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2006. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2007a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2006. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2007b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2007. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2008a): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2007. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2008b): Cine para leer. Enero-junio 2008. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Equipo Reseña (2009): Cine para leer. Julio-diciembre 2008. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rosa Pinilla and Valeria Ten, undergraduate students at the Universitat Jaume I (Castelló, Spain), for their help extracting information from Cine para leer.

Notes

-

[1]

These films are:

A mi madre le gustan las mujeres (2002): Directed by Daniela Fejerman and Inés París. DVD (2003). WE & CO / Optimale.

Bajarse al moro (1989): Directed by Fernando Colomo. DVD (2001). Madrid: Producciones JRB.

Bwana (1996): Directed by Imanol Uribe. DVD (1997). Madrid: Aurum Producciones, SA.

El próximo Oriente (2006): Directed by Fernando Colomo. DVD (2006). Madrid: Sogepaq.

El traje (2002): Directed by Alberto Rodríguez. DVD (2003). Madrid: Tesela Producciones Cinematográficas.

Fuerte Apache (2007): Directed by Jaume Mateu-Adrover. DVD (2007). Barcelona: DeAPlaneta.

Las cartas de Alou (1990): Directed by Montxo Armendáriz. DVD (2004). Barcelona: Manga.

Pídele cuentas al rey (1999): Directed by José Antonio Quirós. DVD (2000). Madrid: Enrique Cerezo Producciones.

Poniente (2002): Directed by Chus Gutiérrez. DVD (2002). Madrid: Araba Films.

Salvajes (2001): Directed by Carlos Molinero. DVD (2002). Barcelona: Filmax Home Video.

Tapas (2005): Directed by José Corbacho and Juan Cruz. DVD (2005). Barcelona: Filmax Home.

-

[2]

This involves micro-textual, descriptive analysis, identifying all samples in which immigrants communicate and classifying translation strategies and techniques into various European languages according to different degrees of domestication and foreignisation.

-

[3]

Although we only found instances of four translation strategies in our previous research (self-translation, liaison interpreting, subtitling and no-translation), we will include voice-over as a fifth possibility, since all five strategies could theoretically be used to translate these dialogues (Corrius 2008).

-

[4]

Co-productions reflect the situation and attitudes of different countries (rather than those of just one). This calls for a more complex analysis that lies beyond the scope of our current research. Likewise, our intention was to focus on the drama genre and not on the informative genre (see Luyken, Langham-Brown et al. 1991), this explains why documentaries are not considered. Following Argote (2003), we also decided not to analyse animation films on this occasion.

-

[5]

Most of the films studied can be considered migration films (see Wahl 2008). Just as in Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. (2010), this paper focuses on post-colonial migration and its role within globalisation, so the films in our corpus portray only non-European Union characters from Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe (in the latter case we include countries that did not belong to the EU during the period studied). Films containing immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America have been left out because their main language of communication is Spanish, and therefore these films do not fit the plurilingual focus of this paper.

-

[6]

This information was obtained from Cine para leer, a publication edited by Equipo Reseña, which lists the films released in Madrid every semester. See appendix for the specific volumes consulted for this research.

-

[7]

In the English subtitled version of A mi madre le gustan las mujeres, we also found the use of italics to render misspellings in the L1, like prisent for present to translate regala instead of the standard regalo.

-

[8]

Besides the techniques described above, in the French subtitling of A mi madre le gustan las mujeres, we detected the use of inverted commas to convey the misspelling mentioned in endnote 7: /Mon “prisent”/.

Bibliography

- Agost, Rosa (2000): Traducción y diversidad de lenguas. In: Lourdes Lorenzo and Ana María Pereira, eds. Traducción subordinada (I) (inglés-español/galego). Vigo: Universidade de Vigo, 49-67.

- Argote, Rosabel (2003): La mujer inmigrante en el cine español del inaugurado siglo XXI. Imaginando a la mujer, Feminismo/s. 2:121-138. Visited on 15 March 2013, http://media-diversity.org/en/additional-files/documents/b-studies-reports/The%20Immigrant%20Woman%20in%20Spanish%20Cinema%20%5BES%5D.pdf.

- Bartoll, Eduardo (2006): Subtitling multilingual films. In: Mary Carroll, Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast and Sandra Nauert, eds. Audiovisual Translation Scenarios. (Marie Curie Euroconferences MuTra, Copenhaguen, 1-5 May 2006). Visited on 30 November 2010, http://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2006_Proceedings/2006_Bartoll_Eduard.pdf.

- Bleichenbacher, Lukas (2008): Multilingualism in the Movies. Hollywood Characters and Their Language Choices. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

- Corrius, Montserrat (2008): Translating Multilingual Audiovisual Texts. Priorities, Restrictions, Theoretical Implications. Doctoral thesis, unplublished. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Dwyer, Tessa (2005): Universally speaking: Lost in Translation and polyglot cinema. In: Dirk Delabastita and Rainier Grutman, eds. Fictionalising Translation and Multilingualism. Linguistica Antverpiensia. 4:295-310.

- Hurtado, Amparo (1996): La cuestión del método traductor. Método, estrategia y técnica de traducción. Sendebar. 7:39-57.

- Hurtado, Amparo ed. (1999): Enseñar a traducir. Metodología en la formación de traductores e intérpretes. Madrid: Edelsa.

- Jakobson, Roman (1959/2000): On linguistic aspects of translation. In: Lawrence Venuti, ed. The Translation Studies Reader. London/New York: Routledge, 113-118.

- Luyken, Georg-Michael, Langham-Brown, Jo, Reid, Helen, et al. (1991): Overcoming language barriers in television. Manchester: The European Institute for the Media.

- Marco, Josep (2004): Les tècniques de traducció (dels referents culturals): retorn per a quedar-nos-hi. Quaderns. Revista de traducció. 11:129-149.

- Martínez-Sierra, Juan José, Martí-Ferriol, José Luis, De Higes-Andino, Irene, et al. (2010): Linguistic Diversity in Spanish Immigration Films. A Translational Approach. In: Verena Berger and Miya Komori, eds. Plurilingualism in Cinema: Cultural Contact and Migration in France, Italy, Portugal and Spain. Vienna: Lit Verlag, 15-32.

- Molina, Lucía and Hurtado, Amparo (2002): Translation Techniques Revisited: A Dynamic and Functionalist Approach. Meta. 47(4):498-512.

- Venuti, Lawrence (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation. London/New York: Routledge.

- Wahl, Chris (2008): “Du Deutscher, toi Français, You English: Beautiful” – The Polyglot Film as a Genre. In: Miyase Christensen and Nezih Erdŏgan, eds. Shifting Landscapes: Film and Media in European Context. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 334-350.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

A continuum of translation techniques for subtitled plurilingual films

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Translation techniques in the original version (adapted from Martínez-Sierra, Martí-Ferriol et al. 2010)

Table 2

Model of analysis for the subtitled versions

Table 3

Film corpus: source versions, DVD and target versions

Table 4

Strategies and techniques found in the analysis of subtitled versions

10.7202/008033ar

10.7202/008033ar