Résumés

Abstract

This article reports on an investigation which forms part of a comprehensive empirical project aimed at investigating the status of professional translators and interpreters in a variety of contexts. The purpose of the research reported on here was to investigate the differences in terms of occupational status between the three groups of professional business translators which we were able to identify in relatively large numbers on the Danish translation market: company, agency and freelance translators. The method involves data from questionnaires completed by a total of 244 translators belonging to one of the three groups. The translators’ perceptions of their occupational status were examined and compared through their responses to questions evolving around four parameters of occupational prestige: (1) salary/income, (2) education/expertise, (3) visibility, and (4) power/influence. Our hypothesis was that company translators would come out at the top of the translator hierarchy, closely followed by agency translators, whereas freelancers would position themselves at the bottom. Although our findings largely confirm the hypothesis and lead to the identification of a number of differences between the three groups of translators in terms of occupational status, the analyses did in fact allow us to identify more similarities than differences. The analyses and results are discussed in detail, and avenues for further research are suggested.

Keywords:

- translator status,

- the translation profession,

- business translators,

- occupational prestige,

- professionalization

Résumé

Le présent article rend compte d’une étude qui s’inscrit dans un vaste projet de recherche empirique visant à enquêter sur le statut des traducteurs et des interprètes professionnels dans des contextes variés. L’objectif de l’étude était d’enquêter sur les différences de statut professionnel entre les trois groupes de traducteurs spécialisés professionnels, qui sont, d’après nos estimations, en nombre relativement important sur le marché danois de la traduction : les traducteurs employés dans une société, les traducteurs employés dans une agence, et les traducteurs indépendants. La méthodologie fait appel à des données provenant de questionnaires remplis par un total de 244 traducteurs appartenant à l’un de ces trois groupes. Les perceptions des traducteurs à l’égard de leur statut professionnel ont été étudiées et comparées grâce aux réponses fournies à des questions regroupées autour de quatre paramètres relatifs au prestige professionnel : (1) salaire/revenus, (2) formation/expertise, (3) visibilité, (4) pouvoir/influence. Notre hypothèse était que les traducteurs employés dans une société arriveraient au sommet de la hiérarchie en termes de statut professionnel, suivis de près par ceux qui sont employés dans une agence, tandis que les traducteurs indépendants se positionneraient au bas de la hiérarchie. Bien que les résultats corroborent largement notre hypothèse et conduisent à l’identification de certaines différences, les analyses nous ont, en fait, permis de repérer plus de similarités que de différences. Les analyses et les résultats sont présentés en détail, et de nouvelles voies de recherche sont suggérées.

Mots-clés :

- statut des traducteurs,

- la profession de traducteur,

- traducteurs spécialisés,

- prestige professionnel,

- professionnalisation

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Translator status has received very little attention in Translation Studies (TS) as a subject in its own right. Although the literature abounds with references to translation as a low-status profession, few empirical studies have addressed the topic systematically and exhaustively (for an overview of the literature on translator status, see Dam and Zethsen 2008). To start filling this vacuum, the authors of the present paper have embarked on a comprehensive empirical project with the long-term aim of investigating the status of professional translators and interpreters of various kinds and in various contexts.

In a previous article, the first study in our project was published (Study 1; Dam and Zethsen 2008). In that study, we explored the status of a group of translators we assumed to be at the high end of the translator-status continuum, namely Danish translators with an MA in translation who were employed full-time on permanent contracts in major companies with a visible translation function and a clear translation profile. We took these professionals to be a relatively strong group of translators not least due to their background in the Danish system which – in contrast with many other countries – has for many years offered a system of state certification (accreditation) and an MA in translation. The status of the translators was explored on the basis of questionnaires focusing on four occupational status parameters: (1) salary, (2) education/expertise, (3) visibility, and (4) power/influence. Due to the relatively strong professional profile of the translators chosen for the study, we expected the analyses to yield a relatively high-status picture for these particular translators. Although the findings did not indicate an extremely low perception of the translators’ occupational status, they did suggest a much lower status than expected. The results thus support the general picture of translation as a low-status occupation that we meet in the translation literature.

Following the study of the company translators (Study 1), we have conducted two similar studies which focused on the status of two other important groups of Danish business translators, namely agency translators (Study 2) and freelance translators (Study 3). These two studies draw on the same methodology as Study 1, and the results may therefore be compared. The purpose of the investigation reported on in this article is to compare the occupational status of all three groups of translators that we have examined so far: company, agency and freelance translators. Taken together, the three studies cover all categories of professional business translators in Denmark which we were able to identify in sufficiently large numbers to conduct a quantitative investigation (some 50 or more).

Please note that we use the delimitative term professional not only to identify translators with a certain set of qualifications, but also in the classical sense of the term, to signify people who engage in an occupation – in this case translation – to make a living (for a discussion of professionalization in a sociological sense, see section 2.). All the translators who participated in our studies are professionals in that sense: they view translation as their main occupation and main source of income. The investigation is further restricted to business translators, by which we mean translators who translate for business and industry. These kinds of translators are often referred to in the literature as “non-literary translators,” a negative term which we find belittles the role and importance of these translators, who are in fact responsible for the bulk of translations in today’s globalized world, as “technical translators“, which is too narrow, or as “commercial translators,” which in our view may have negative connotations. Several other terms appear in the literature, among which we find that only “business translators” describes who these professionals are and what they do in a sufficiently telling way. Finally, the present investigation is delimited to translators operating on the Danish market, although the project will eventually be extended to include translators in other countries as well. Incidentally, these delimitations exclude interpreters as a group from participating in our investigation: in Denmark next to no one – probably less than a handful – claim interpreting as their main occupation and source of income. Virtually no Danish companies or organisations count full-time interpreters among their staff, and only very few freelancers claim interpreting as their main occupation. Within the specified delimitation, our sample covers all the important groups of (professional) translators (in the Danish business translation market).

2. The Concepts of Professionalization and Status

2.1. What is a Profession?

According to Weiss-Gal and Welbourne (2008: 282), numerous attempts have been made over the years to develop a theoretical framework to distinguish professions from non-professions and to identify the factors that influence their development. Two main approaches have emerged, namely the attribute approach and the power approach. As the name implies, the attribute approach relies on core traits which define a profession (as opposed to a mere occupation). Greenwood (1957: 45) identified five critical attributes: (1) systematic theory, (2) authority, (3) community sanction, (4) ethical codes, and (5) a culture. Though other scholars have pointed out other traits, the original five are still considered the essential traits. The power approach emerged in the 1970s and it focuses on how occupations establish and maintain dominance when confronted with threats to their status from competing interests (such as other occupational groups, government, their clients, etc.). Basically, the approach assumes that professions struggle for an exclusive right to perform certain types of work and are in constant conflict with other groups over issues of boundaries, clients, resources and licensing (Weiss-Gal and Welbourne 2008: 282). In accordance with the power approach, Freidson (1970) defined professions as occupations which have a dominant position of power in the division of labour in their area of practice and thus have control over the content of their work. In their 2008 article, Weiss-Gal and Welbourne combine the two influential approaches and list the following eight criteria as indicative of a profession: (1) public recognition of professional status, (2) professional monopoly over specific types of work, (3) professional autonomy of action, (4) possession of a distinctive knowledge base, (5) professional education regulated by members of the profession, (6) an effective professional organization, (7) codified ethical standards, and (8) prestige and remuneration reflecting professional standing.

2.2. Translation in Denmark – a Semi-Profession?

Because Danish is a minority language in Europe (about five million speakers), Denmark has, from an early date, had to deal with the need for translation. In 1910, a system of certification based on testing was introduced, and at the same time the Danish Association of Translators – which still exists – was founded. In 1966 Denmark passed the world’s first translator’s act, which put in place a system of certification, rights and obligations and a code of translation ethics. This coincided with the introduction of a new MA in specialised translation which led more or less directly to certification. Translation has thus been an independent academic discipline in Denmark for more than 40 years. Despite this history, however, it was not until the 1970s that the volume of translation work increased to the point that translation became a full-time occupation and career. Today the Danish translation market is probably among the most well-organised and well-educated national markets in the world, but it is doubtful whether it has developed into a full-fledged profession in accordance with the criteria outlined above. Fully meeting the following criteria in particular seems problematic to us: (1) public recognition of professional status, (2) professional monopoly over specific types of work and (3) prestige and remuneration reflecting professional standing. Translation in Denmark could probably be called a semi-profession aspiring to become a full profession, and it seems quite clear to us that the barriers to full professionalization are closely connected to status and prestige. In the following we shall account for the concept of status and how we understand it in the present context.

2.3. The Concept of Status

In the 1940s the sociologists North and Hatt developed occupational prestige scales which sparked a heated debate about the inferences which could be drawn from such scales – did they, for example, reflect the worthiness of occupations or the material rewards connected with a certain occupation (Ollivier 2000). Ollivier suggests that some status parameters are important to some people or in some contexts, and others, to other people in other contexts. That is, status is a complex, subjective and context-dependent construct and as such it is not an absolute notion.

A national Danish study of occupational status conducted in 2006 (Nyrup Madsen 2006)[1] identifies four main parameters for determining status in a Danish context:

High level of education/expertise

Visibility/fame

High salary

Power/influence

Worthiness/value to society is not given as a parameter. This does of course not necessarily mean that these qualities are not considered important, but merely that they are not considered important in a prestige context (at least not in Denmark it would seem). The four parameters confirm what is often mentioned in the translation literature as being of importance, so generally speaking we assume that these parameters apply across the Western world, but in various combinations, with different weights, in different contexts, at different times. Consequently, they have formed the basis of our empirical research.

2.4. Translator Status – a Continuum

As indicated, status is not a binary concept, but can be more adequately described by means of a continuum. Within the translation profession, conference interpreters and to a certain degree translators working for international organisations are often perceived as having the highest status due to their presumed glamorous working conditions and high salaries, whereas so-called commercial translators, community interpreters and other public-service translators and interpreters are generally considered to be at the lower end of the status continuum for the opposite reasons (e.g., Diriker 2004; Gile 2004: 12-14; see Fraser and Rogers comments, in Schäffner 2004b: 35-48; Sela-Sheffy and Shlesinger 2008: 81). As the continuum is subjective and context-dependent, the high salary of conference interpreters and staff translators in international organisations may of course not be seen by all as being as attractive and prestigious as earning a meagre living as an intellectually satisfied literary translator. Indeed, if anything, translation scholars tend to place literary translators at the top of the prestige scale (e.g., Fraser, in Schäffner 2004: 35; Sela-Sheffy and Shlesinger 2008: 81), although the present authors are convinced that in a Danish context, literary translation would be associated with lower status than translation in a business context in most communities.

Apart from such general and relatively loose considerations about highly different groups of translators/interpreters and their relative position at either end of the status continuum, the TS-literature does not address the issue of translator-status segmentation in any systematic way, neither theoretically nor empirically. This is where the present investigation comes in: an empirical investigation of the occupational status of three different but well-defined groups of translators operating within the same national and cultural context. It takes the first steps towards filling a gap in the TS-literature.

3. Introduction to our Investigation

With the study reported on here we set out to compare the occupational status of the three groups of professional business translators which we were able to identify in sufficiently large numbers on the Danish translation market – company, agency and freelance translators – in order to study differences between the three groups and to identify their relative position in the status hierarchy. The research question which will be addressed can thus be summarized as follows: what is the relative position of company, agency and freelance translators on the status continuum for professional business translators in Denmark?

Our hypothesis about the three groups of translators’ relative position on the status continuum was that company translators would come out at the top of the hierarchy, closely followed by agency translators, whereas freelancers would be at the bottom. The hypothesis was based on considerations about the nature of their employment, the two former groups being staff translators – with all the benefits this entails in terms of security and stability of employment and income – and the latter not, and about the presumably isolated nature of the freelancers’ work situation, which we assumed would have implications for their visibility and possibilities of exercising influence. The freelancers’ influence on their own work situation is of course unique, and in this respect they resemble the classic professions, such as doctors and lawyers, more than the other two groups. Also, as pointed out by Janet Fraser, we cannot ignore “the model of the freelance translator as a successful exponent of ‘new’ or ‘boundaryless’ careers” (Fraser 2004: 60). However, the inclination towards self-employment in Denmark is known to be exceptionally low compared to other countries: Danes simply seem to prefer the stability of a steady job to the freedom associated with self-employment. In this respect, our hypothesis is clearly influenced by the Danish context in which the research was conducted and it is therefore not necessarily globally valid. As to the relative position of the two presumably strongest groups – company and agency translators – our assumption was that company translators, as on-site employees in large and complex companies, would have slightly higher visibility and possibly also more influence in relation not only to translator colleagues, but also to non-translators. Agency translators obviously have ample possibilities to interact extensively with other translators, their work colleagues, but they probably interact less with other professionals, and hence they are likely to have less visibility in the non-translation world. Moreover, it stands to reason that company translators’ perception of their occupational image is influenced by the fact that they are usually employed in large and important international companies (as our respondents are). Working for a company of that kind may be perceived as connected with prestige per se. The translation firms for which the agency translators work, on the other hand, are typically small (or at least smaller) and unknown to people outside the translation business. All in all, our expectation was that company translators in our investigation would turn out to have the highest occupational status, that they would be followed closely by the other group of staff translators – agency translators – and that freelance translators would prove to be the group with the lowest occupational status.

4. Data and Methods

The data were collected over a period of two years and are based on a total of 244 completed questionnaires with the following distribution over the three studies and groups of translators:

Study 1: company translators: 47 (from 13 companies)

Study 2: agency translators: 66 (from 12 agencies)

Study 3: freelance translators: 131

The Danish translation market is relatively small and the number of translators who have participated in the investigation represent a very large section of the total number of Danish translators. In 2009, the total number of certified translators, for all languages, is 2,746 individuals.[2] Many of these individuals are not practising translators, but we cannot say how large a percentage. Once certification is granted (even if 30 years ago), it is not withdrawn, even if the translator does not work in the field. In addition, maintaining certification is free so there is no reason for the translator to relinquish it. A more reliable source for the number of practising translators (or rather freelance and agency translators) in Denmark is likely to be the two associations which organise only certified translators. In total, their membership is approximately 265.

Apart from the differences in the contexts in which they work (companies, agencies or independently), an attempt was made to select a sample of translators which was as homogenous as possible: only business translators working on the Danish market, holding an MA in specialized translation and/or state certification and for whom translation was their main occupation were selected to participate in the whole project. For company and agency translators, a further requirement was that they be employed on permanent contracts, whereas the freelancers were required not to be employed by others or have employees themselves (the majority of the freelancers in the sample do in fact translate for translation agencies and pass on work to other freelance translators on a regular basis, but in no case is the latter their main source of income). Apart from serving a homogeneity purpose for reasons of comparability, these selection criteria served to ensure a sample of translators with a strong professional profile and presumably at the high end of the translator-status continuum.

The data collection process ran as follows: In Study 1 we sought out and contacted all the private Danish companies which employ three or more translators with the specified profile and we ended up with a total of 50 companies, most of them among the largest Danish companies. In Study 2 we identified and contacted all Danish translation agencies with a minimum of three translators with the specified profile, a total of 28 agencies. And finally, in Study 3 we contacted all members of the two Danish organisations for state-certified translators whom we did not already know to be permanent employees of a translation agency or a company, a total of 265 translators. Thus, all Danish translators who might match the above profiles and whose agencies or companies seemed to match the profiles were contacted, not merely a representative selection or sample. The large majority of the companies, agencies and individual translators who were contacted, but who did not participate in the project, did not participate because, upon further scrutiny, they turned out not to fulfil the criteria for participation. Only two companies, two translation agencies and six individual translators actually declined to participate. Having identified the relevant participants, we sent out questionnaires to 78 agency translators and 153 freelance translators, out of which 76 and 148, respectively, were completed and returned (i.e., the final response rates were 97% for both Studies - 2 and 3). For Study 1 we are not able to present similar figures as the company translators were not directly contacted by us but through an intermediary within each participating company who had agreed to ask all the company’s translators with the desired profile to complete a questionnaire and to collect and return them to us. Based on our correspondence with the intermediaries in the companies, we are certain to have obtained completed questionnaires from the majority of eligible translators in their employ. Virtually all the translators with whom we were in contact during the process of data collection showed an immense interest in the research and were eager to participate. In all three studies, some of the respondents (4 in Study 1, 10 in Study 2, and 17 in Study 3) ultimately turned out not to fulfil the criteria for participation, as evidenced by their responses to a series of control questions in the questionnaires. The questionnaires from these translators were filtered out and were not included in the final sample, which thus consists of data from a total of 47 company translator questionnaires, 66 agency translator questionnaires and 131 freelance translator questionnaires, as indicated above. The data from the three studies were collected in January 2007, 2008 and 2009, respectively.

The questionnaires for all three studies were as similar as possible; they were only modified as required by the varying contexts. We did ensure that the different questionnaires covered the same parameters, notably the four main status parameters identified in section 2. The questions will be described in more detail below, specifically in the analysis section, as will other issues related to methodology. Suffice to say here that the questions focused on opinions, not facts, and that most were designed to be answered by ticking (typically) one of five statements representing different degrees of agreement with the question, as specified in section 5.

5. Analyses and Results

The data from the completed questionnaires were entered into the statistical software programme SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), which allows statistical analyses and cross searches of all kinds. The few instances of multiple replies and unanswered questions found in the data were omitted and do not form part of the analysed sample. The graded response categories accompanying the questions in the questionnaires were converted into numerical values as follows:

To a very high degree |

→ | 5 |

To a high degree |

→ | 4 |

To a certain degree |

→ | 3 |

To a low degree |

→ | 2 |

To a very low degree or not/none at all |

→ | 1 |

The conversion into numerical values allowed us to calculate the mean values of the graded responses and thus made it possible to reduce the original five-dimensional response to a one-dimensional representation, which again made intergroup comparisons feasible. Correspondingly, most of the data are presented in figures in the sections below through columns indicating the mean values of the three respondent groups’ ratings in relation to each of the analysed questions. The between-group differences were tested for statistical significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test for analysis of variance and the Dunn method for analysis of confidence intervals. The statistical analyses were conducted at a level of significance of 5%. The details of each of the many significance tests are not specified below, but as a general rule we only discuss differences which were found to be statistically significant. Exceptions to this rule are specifically indicated.

In the following subsections we shall consider the results of the analyses in relation to each of the status parameters which formed the focus of the research: salary/income, education/expertise, visibility and power/influence. Also, results from questions oriented towards delving more generally and directly into the issue of translator status and prestige are shown. Although these questions were placed at the very end of the questionnaires to avoid being too explicit about the topic of the research project, they will be considered first in our analysis. Several direct and indirect questions were asked in relation to each parameter, but we shall limit ourselves to discussing the results for the most central questions only.

5.1. Translator Status and Prestige in General

As the last or one of the last questions in the questionnaires, the three groups of respondents were asked how they perceived their status as translators in society. The five verbal response categories (in this case very high status, high status, a certain status, low status and very low status) were converted into numerical values between 1 and 5 as explained above, and the mean values of the responses for each group were calculated, yielding the results shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1

Translator status[*] as perceived by the company, agency and freelance translators

As we can see, the average rating of agency and freelance translators are very similar, close to identical (2.55 and 2.53, respectively), whereas the company translators rated their occupational status slightly higher than the two other groups (2.87). Although the difference is not large, it is still statistically significant. Similar response patterns can be identified for other questions oriented towards directly inquiring into the issue of translator status and/or prestige in the data. These response patterns lend certain evidence to our hypothesis where company translators are ranked at the high end of the status continuum, but our assumption that freelancers would come out at the very bottom of the hierarchy seems more doubtful in view of the practically identical status scores for agency and freelance translators. In fact, this pattern of agency and freelance translators giving very similar responses, which are slightly different from those of company translators, runs through the entire sample, as we shall see below, and it suggests a need for a revised hypothesis about the relative position of the three groups on the status continuum.

Whatever the similarities and dissimilarities in the responses of the three groups, there is in fact an overall consensus even among these relatively high-profile translators that translation is not a high-status profession, as can be derived from the fact that the average ratings for all three groups are below the midscale value (i.e., 3) on the 1-5 rating scale.

5.2. Salary/Income

Salary or income is often claimed to be an important status parameter in the translation literature (e.g., Chan 2005); an observation also reflected in the national Danish study of occupational status on which our project is based. In addition, a remuneration reflecting professional standing is included in Weiss-Gal and Welbourne’s list of criteria defining a profession, as explained in section 2.1. However, some translation scholars have also noted that translation is a low-status occupation in spite of high remuneration (e.g., Hermans and Lambert 1998: 123; Koskinen 2000: 61). Thus, although salary is potentially a good indicator of status, it is not necessarily the decisive factor.

In our research, the translators were asked to indicate their salary (or income in the case of the freelancers, who strictly speaking do not earn a salary) by marking one of the following monthly income ranges: below 25,000 DKK[3]; 25,000-29,000 DKK; 30,000-34,000 DKK; 35,000-39,000 DKK; 40,000-44,000 DKK; 45,000-49,000 DKK; 50,000-54,000 DKK; 55,000 DKK or more. In the analyses and in Figure 2, which summarizes the results, these ranges were merged into three manageable categories: (1) below average, (2) average, and (3) above average. In this context, average refers to the average salary for professionals with a level of education, work experience and job context comparable to that of the translator respondents in our study, i.e., holders of an MA degree who graduated in 1997, 1996 and 1992, respectively, (the mean graduation years of the respondents in our Studies 1, 2 and 3) with employment in the private labour market in Denmark. The average salary of this group of professionals ranged between approximately 41,500 and 43,500 DKK per month, depending on the mean graduation year and the time of data collection.[4] Consequently, the category referred to as average covers the income range given in the questionnaires as 40,000-44,000 DKK, whereas below average covers all the lower ranges, and above average all the higher ranges, cf. Figure 2. Note that in Figure 2 the income responses from the translators who stated that they work less than full time have been filtered out in order to neutralize the possible (and likely) effect of part-time work on the income level.

Figure 2

The company, agency and freelance translators’ monthly income expressed as below average, average and above average with respect to the income of a group of comparable professionals

As can be derived from Figure 2, none of the three groups have a high level of income. By far most of the translators have an income below the average for comparable professionals in Denmark (94% of the company translators, 83% of the agency translators and 70% of the freelancers), and only very few have remuneration levels above average (3% of the company translators, 11% of the agency translators and 24% of the freelancers). Generally, these results are in line with the low overall status ratings described in section 5.1.

Still, there are certain differences between the three groups. The company translators clearly hit the bottom: as many as 94% have income levels below the comparable average, and only 3% have a higher than average salary. The freelance translators, on the other hand, count the highest income levels: “only” 70% of them have a monthly income below average, whereas 24% have earnings above average. The agency translators lie somewhere between company and freelance translators in terms of remuneration. This result is interesting as it indicates a negative correlation between status perceptions and income levels. Although the generally low status assessments and the generally low income levels found in our data support each other well, at the group level there is no direct relationship between status evaluations and income – quite the contrary. Company translators have the highest status ratings, but the lowest salaries. With the freelance translators it is the opposite: they have the lowest status perceptions (though closely followed by agency translators, the difference between these two groups being not statistically significant), but the highest salaries. This lends support to Hermans and Lambert’s and Koskinen’s observation that there may not necessarily be a close link between occupational status and remuneration (cf. above). This was also partly corroborated by a correlation analysis conducted on the company translator responses in a previous article (Dam and Zethsen 2009). This analysis did show a correlation between salary level and low status perceptions (low salary correlated with low status ratings, and high salary correlated with an absence of low status ratings), but it showed no correlation between salary level and high status ratings. As we tentatively explained this finding, a certain level of remuneration may be a necessary condition for translators not to view the status of their profession as low, but it may not by itself be sufficient to ensure a high-status perception.

5.3. Education/Expertise

In the Danish study of occupational status described above, jobs requiring a high level of education and a high degree of expertise and specialised knowledge came out in the absolute top of the prestige scale. In much the same way, education and knowledge appear as dominant features in the various definitions of a profession (cf. section 2.1.), and in the translation literature frequent references to the relationship between education/training and status are made (e.g., Chesterman and Wagner 2002: 35; Schäffner 2004a: 8). The parameter of education/expertise thus seems to be very important for occupational status.

In this investigation, there was no point in asking the translators factual questions about their level of education, as it was known in advance, but we asked them a series of questions relating to their own and others’ perceptions of their level of education, expertise and specialized knowledge. In one question, we inquired into the translators’ own assessment of the degree of expertise required to perform their job as translators, and the answers for each of the three groups of translators are shown in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3

Degree of expertise[*] required to translate as assessed by the company, agency and freelance translators

Figure 3 shows a general tendency in all three groups of translators to see translation as an expert function. Company, agency and freelance translators all gave an average expertise score of over 4 on the 1-5 point scale. Especially agency and freelance translators, whose average scores of 4.67 and 4.69 are almost identical (much in the same way as their general status scores, cf. section 5.1.) tend to see themselves as highly skilled experts, whereas company translators rate their level of expertise lower (4.09 on average), this difference being the only statistically significant one. The response patterns identified in connection with the income analyses in section 5.2. repeat themselves in the current analysis of expertise, insofar as company translators, who have the highest general status ratings, also have the lowest expertise ratings, whereas the highest expertise ratings, which were given by agency and freelance translators, correlate with the lowest general status ratings.

It is not surprising that agency and freelance translators should have a strong professional identity and consider themselves highly skilled experts to an even higher degree than company translators, since the former groups work in or own a translation firm whose core service, with which they are likely to identify themselves, is … translation. They are simply always immersed in translation. Company translators, on the other hand, are members of (larger) organisations whose core product or service is everything but translation, be it legal aid, financial services, pumps or coolers, and this is likely to shape their professional identities and perceptions of the nature of their role and skills. In fact, the questionnaire data lend certain evidence to the idea that agency and freelance translators should have stronger professional identities than company translators, with the freelancers taking the absolute lead position. For example, the data show that agency and freelance translators tend to refer to their professional selves as “translators” more often (in 88% and 99% of the cases, respectively) than company translators do (61%). Also, “only” 85% of company translators have chosen to take out state certification as translators (although they are all qualified to do so because of their MA in specialized translation), whereas this is the case for 94% of agency and 100% of freelance translators. Still, it is rather surprising, or at least intriguing, that there is a directly inverse relationship between status and expertise perceptions. However, when it comes to expertise, external evaluations are likely to play an important role, perhaps even more important than internal assessments. A profession’s status is always shaped by both profession-internal and profession-external views, but when it comes to perceptions of expertise, external recognition is likely to be of particular importance. In our data, there is quite a lot of evidence to indicate that people outside the translation profession hold translators’ expertise in low esteem.

In a previous article (Dam and Zethsen 2008) we analysed the occupational status of company translators (group 1 in the current article) as perceived not only by themselves, but also by their fellow employees and internal clients – the so-called core employees of the companies (in a law firm, the lawyers – in a bank, the economists, etc.). Though their general ratings of translator expertise were relatively high (3.88, i.e., lower than the self-assessments made by company translators, cf. Figure 3, but still relatively high), their ratings were seriously challenged when they were asked in more indirect ways about translator expertise. In one analysis, it turned out that almost half of the core employees (49%) viewed translation as a secretarial function to a certain, a high or a very high degree (Dam and Zethsen 2008: 86-87). In another analysis, we found that the majority (59%) assessed the length of translator education to be 3-4 years or even 1-2 years, whereas only 41% thought or knew that an MA (5-6 years) was required (Dam and Zethsen 2008: 87-88). These findings suggest something of a contradiction in the attitudes and understandings of the core employees. On the one hand, they claim to value the expertise of translators, yet on the other, they underestimate the level of knowledge and skills involved in translating and in becoming a professional translator.

In the two other studies which are included in this article – the one on agency translators (Study 2) and the one on freelance translators (Study 3) – the perception of others was not represented by any concrete group of people within the translators’ immediate surroundings (simply because no such groups could be identified), but by the translators’ own answers to questions about the views held by people outside the profession. Thus, for each status parameter we asked the translators to indicate both their own perception and what they thought other people’s perceptions were – for example on the issue of translator expertise. As a general rule, the response patterns to the questions on the translators’ own views were mirrored in their responses to the questions on the views of people outside the profession. Only did the latter type of questions systematically elicit lower ratings. We interpret this to mean that translators generally find that people from outside the field hold the translation profession in lower esteem than it deserves. Still, when the respondents were asked about the degree of expertise they thought people outside the profession would attribute to translators, their responses were unusually negative and resulted in far lower ratings than for the question about how much expertise they themselves feel is required to translate (cf. Figure 3). The mean ratings given by agency translators to the question about the perception of people outside the profession were 2.52 – very low compared to their own average assessments of translator expertise (4.67, cf. Figure 3). The corresponding mean values for freelance translators’ responses to the same questions show the same pattern: 2.74 (assessed external views on their expertise) vs. 4.69 (their own view, cf. Figure 3). Furthermore, agency translators estimated that people outside the profession, if asked, would presume, in 80% of the cases, that translator education takes less time than it actually does. The corresponding percentage in Study 3 (freelancers) was 88%. Considering the 59% incorrect core employee answers in Study 1 (company translators; cf. above), our translator respondents’ assessments of other people’s views are not completely out of line with reality, although their pessimism tends to be exaggerated.

Finally, the questionnaires contained an open question where respondents were invited to state comments of any kind. Our analyses of the large volume of comments this invitation produced show that translators are particularly preoccupied with the lack of recognition of the expertise and skills it takes to translate (Dam and Zethsen 2010). The “anyone-can-do-it” attitude seems to be extremely widespread and to constitute one of the most important threats to the occupational status of the profession.

In sum, we have much and varied evidence to indicate that people outside the profession underestimate the expertise required to translate, which may serve to explain the apparent discrepancy between the (low) general status ratings and the (high) self-assessed expertise ratings found in our data. Although translators see themselves as highly skilled experts, they are painfully aware that others do not. Moreover, it is not unlikely that the more translators (and other professionals) see themselves as experts, the more frustrating it is not to be recognized as such by the outside world.

5.4. Visibility

The parameter of visibility/fame, which was deemed to be an important factor in the national Danish study of occupational status described in section 2.3, is not wholly applicable to this investigation. Translators are by definition not famous. As noted by Christina Schäffner, “there are no widely known ‘stars’ in the profession” (Schäffner 2004a: 1). While it may be the case that stardom is sometimes associated with literary translators (see e.g., Sela-Sheffy (2005) who describes an “emerging ‘star system’” among Israeli literary translators), and that conference interpreters are sometimes associated with fame and glamour (Diriker 2004; Gile 2004: 12-13), the same cannot be said of business translators. We therefore focused our research on the visibility aspect of the dual parameter visibility/fame – a concept frequently discussed in translation studies.

Translators are often described in the literature as physically and professionally isolated (e.g., Hermans and Lambert 1998: 123; Risku 2004: 190). Two aspects of visibility that we have chosen to highlight in our research are therefore the physical location of the translators’ workplaces and their professional contact with other people. Apart from these more tangible aspects of visibility, we studied the issue by asking translators a more abstract question about their perception of their visibility as translators.

As for the physical location of the translators’ workplaces, we asked company translators where in the company their office or workplace was situated. 41% of them answered in a central location, 11% said in a peripheral location, and 48% stated that it was situated neither in a central nor in a peripheral location. That is, overall, company translators did not feel physically isolated in the company, but rather felt that they were placed in central or at least in “neutral” locations. Apart from the possibilities of being physically seen by others, a central location in a company obviously has symbolic value, as it is associated with importance and prestige. Agency translators in our sample do not work in large companies, but often in relatively small translation firms, so asking them about the centrality of their office or workplace was not relevant. On the other hand, agency translators are known to sometimes work from home, and thus in physical isolation. We therefore asked them whether they usually worked at home or in their office at the agency. Only 8% answered that they usually work at home, whereas the remaining 92% list their agency’s office as their regular daily workplace. Physical isolation is therefore not characteristic of this group of translators either. With freelance translators, the situation is different. 90% of them work from home (87% always, 3% mostly), while only 10% share an office with other translators or other professionals and use it regularly. Whereas the work situation for freelancers is thus characterised by physical isolation, both company and agency translators have many options available to them to avoid physical isolation at work.

Professional isolation, on the other hand, was not an issue for any of the groups, as suggested by the columns in Figure 4, which represent the three groups of translators’ responses to a question concerning their degree of professional contact with others (colleagues, clients, etc.):

Figure 4

The degree of professional contact of company, agency and freelance translators[*]

As indicated in Figure 4, the degree of professional contact is rated above the midscale value (3) by all three groups. Company and agency translators in particular have high scores (4.19 and 4.24, respectively, a difference that is not statistically significant). Although the mean contact score for freelancers (3.64) is more moderate and significantly lower than that of the two other groups, this group has a surprisingly high degree of professional contact when you consider their physically isolated work situation. However, apart from the regular contact they are likely to have with their customers and the agencies for which most of them work on a regular basis, it stands to reason that they tend to engage in professional networks with fellow (freelance) translators, most likely through the nowadays widespread on-line communities (Risku and Dickinson 2009). So far, we have not yet asked them about the nature of their professional contacts.

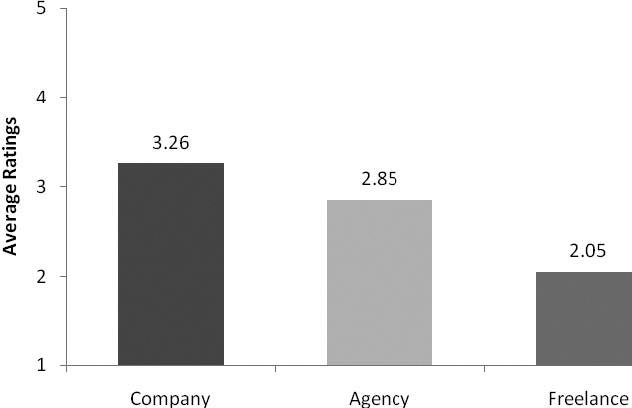

The questions concerning the more abstract concept of translator visibility had to be phrased somewhat differently for the different groups of translators. The idea was to ask how they perceived their visibility in relation to a well-defined context in order to have them assess how people in their (preferably immediate) surroundings viewed their visibility as translators. It was easy to define an immediate context for company translators; however it was not as easy in the case of agency translators and very difficult for freelancers. For company translators we chose their immediate surroundings: the company, their fellow company employees and clients – i.e., we asked about their visibility in the company. For agency translators we opted for a similar but slightly more distant context, namely their clients – i.e., we asked about their visibility with respect to their clients.[5] For freelance translators the only possibility, for lack of a relevant immediate context,[6] was to ask about their general visibility as a professional group. These different phrasings of the visibility question may of course have influenced the respondents’ answers, although the respondents in our sample did in fact show a general tendency to give identical responses to questions concerning the same issue with different contextualisations (for example, company translators were asked to rate both their status within the company and their status in society, and the ratings for these questions turned out completely identical). The three groups of responses to the question about visibility were distributed as shown in Figure 5 below:

Figure 5

The company, agency and freelance translators’ perception of the degree of their visibility[*]

As we can see in Figure 5, none of the three groups assesses their visibility as high, though the ratings for company translators (3.26) are slightly higher than the midscale value and therefore not exactly low. Freelancers assess their visibility as extremely low (2.05), and agency translators position themselves in the middle with a score just below 3 (2.85). These differences are statistically significant. In spite of the potential methodological weaknesses in connection with these results, they fit quite well with the findings in relation to the other visibility parameters, physical and professional isolation/contact, with relatively high scores (though not necessarily the highest) by company translators on all accounts and relatively low scores on all accounts by freelancers. The picture for agency translators is more complex, as they state having close physical and professional contacts, but at the same time relatively low visibility. We attribute this finding to the agency translators’ presumably high degree of contact with their translator colleagues, on the one hand, and apparently low degree of contact with their clients, on the other.

In contrast to the two status parameters previously dealt with – income and expertise (sections 5.2. and 5.3.) – which were found to correlate negatively with status ratings (section 5.1.), these findings show a partly positive correlation between perceived visibility and perceived status, insofar as company translators have the highest status ratings and also the highest visibility scores (though followed closely by agency translators), whereas freelance translators have the lowest status ratings (though followed closely by agency translators, the difference being not statistically significant) and also the lowest scores on all visibility parameters. These findings with regard to visibility also support the hypothesis put forward in section 3 about the relative position of company and freelance translators on the assumed status continuum, partly based on considerations of their relative visibility. The situation for agency translators is less clear-cut. They rank number two in status (but with ratings almost identical to those of freelancers, the difference being not statistically significant) and also number two in the visibility ratings in Figure 5, but they were found to have very high degrees of physical and professional contact with others (most likely their translator colleagues), which are also considered visibility parameters here.

5.5. Power/Influence

The last parameter included in the Danish study of occupational status on which the present investigation is based is that of power/influence – a feature also indicative of a profession as we saw in section 2.1., but which translators are often said to lack (e.g., Baker 1997: xiv; Chesterman and Wagner 2002: 78; Lefevere 1995: 131; Snell-Hornby 2006: 172; Venuti 1995: 131). In order to shed light on the translators’ power/influence, the respondents were asked to answer a handful of similar questions, although once again it was not possible to ask them the exact same questions due to their different job situations. All of them were, however, asked a very general question about job influence, namely to what extent they perceived their job as a translator as connected with influence. The answers we obtained are specified in Figure 6 below:

Figure 6

The company, agency and freelance translators’ perception of the degree of influence connected with their job[*]

As we can see in Figure 6, company translators stand out as those with the highest ratings on influence, but their scores are still low, well below the midscale value of 3 (2.57). Still, agency and freelance translators, whose ratings are also almost identical in this case, indicate a significantly lower degree of influence (1.80 and 1.87). We may also note that, much in the same way as the visibility ratings, the influence scores correlate positively with the general status ratings, insofar as company translators have the highest status ratings and also the highest scores on influence, whereas the freelance translators have one of the two lowest status ratings and also one of the two lowest scores on influence (agency translators actually have lower scores, but the difference is tiny and certainly not statistically significant). The results on influence therefore also support the hypothesis put forward in section 3 about the relative position of company and freelance translators on the assumed status continuum, partly based on considerations of the relative possibilities for them to obtain influence. A result that does not support the hypothesis is agency translators’ mean influence ratings. According to the hypothesis, these results should follow those of company translators rather closely, but they are in fact essentially identical to those of freelance translators – a pattern that has turned out to be the rule rather than the exception.

At a more general level, we may note that, even if there are differences, all three groups of translators report having very little influence, two of the groups with mean scores even below 2. These are the lowest ratings we have seen so far.

The low-influence picture is partly confirmed by the other data we have on translator influence. To inquire further into the issue of influence, company and agency translators were asked two questions concerning management positions and possibilities of promotion, which were not relevant to freelancers, who are by definition their own bosses. The first question asked whether the translators held an executive office or managerial position in the company. Of the possible answers, yes or no, 96% of company translators said they did not have managerial responsibilities, only 4% did. Among agency translators, the percentage of yes was much higher, 28%, while 72% answered no.

We also asked the two groups what the possibilities for them were to achieve an executive office or managerial position. The answers reflected the actual number of translation managers in the two branches and were thus very negative in the case of company translators, who on average assessed their promotion possibilities at 1.96 on a 1-5 scale, and less negative, but far from optimistic in the case of agency translators, whose average score was 2.53. Thus, rather surprisingly, the possibilities of promotion and actual number of management positions do not seem to have any direct bearing on the translators’ perception of their influence in general, as the group most likely to hold or achieve a management position – agency translators – rate their influence lowest, cf. Figure 6, and for company translators the inverse situation applies. Still, all the responses suggest an overall agreement that management positions are hard to achieve in the field of translation, and that translators’ influence in general is limited to an extent that it may be described as one of the profession’s most serious challenges.

6. Conclusion

With the present investigation, we set out to examine the differences in terms of occupational status between the three groups of professional business translators which we were able to identify in sufficiently large numbers on the Danish translation market: company, agency and freelance translators. Our hypothesis about the three groups of translators’ relative position on the translator-status continuum was that company translators would come out at the top of the hierarchy, closely followed by agency translators, whereas freelancers would position themselves at the bottom. The hypothesis was based on considerations about the nature of their employment, the two former groups being staff translators and the latter not, and about the presumably isolated nature of the work situation for freelancers, which we assumed would have implications for their visibility and possibilities of obtaining influence.

On the whole, the results confirmed the hypothesis with some modifications. Thus, company translators came out at the top of the occupational prestige scale and freelancers at the bottom. However, the position of agency translators turned out differently than hypothesized. Rather than a position close to company translators at the top of the hierarchy, they rated themselves closer to freelancers at the bottom, with responses that more often than not resembled those of freelancers to the point of being virtually identical. Being a staff translator, on a permanent contract with stability in employment and income, which we hypothesized would be a decisive factor, may after all not be that important in a status context, but it remains to be investigated which factors are decisive. However, the following summary of the findings may point to certain relevant parameters.

As we have seen, the general status assessments did not always point in the same direction as the evaluations of the individual status parameters. Even if company translators rated their general occupational status higher than the two other groups, they also had the lowest salaries, while freelancers, who – together with agency translators – had the lowest status ratings also had the highest salaries. This indicates that there is no direct relationship between occupational status and income level. There was also a negative correlation between the translators’ assessments of their status and their self-assessed degree of expertise, but this discrepancy may be attributed to the translators’ possible frustration over the attitudes of people outside the profession, whose lack of recognition of translators’ skills and level of expertise is amply documented in this and other studies. On the other hand, our research has shown a predominantly positive correlation between the general status assessments and the ratings on the visibility and influence parameters. Company translators had thus both the highest status ratings and the highest general visibility ratings (though agency translators also had a very high degree of physical and professional contact in their favour), and vice versa with freelancers, who had the lowest status ratings (together with agency translators) and the lowest scores on all visibility parameters. As for influence, company translators felt most influential, in spite of the fact that managerial positions were virtually non-existent and unobtainable in their field, whereas freelance translators assessed their influence as extremely low. More surprisingly, agency translators evaluated their influence as extremely low as well, despite the fact that as many as 28% of them stated having managerial responsibilities. All in all, judging from the results, visibility, (perceived) influence and societal recognition of translation skills and expertise seem to play an important role for the translators’ perception of their occupational status, whereas the apparently most tangible status parameter of them all, money, appears to be less important. This finding is in line with the results of one of our previous studies, also mentioned earlier, in which we correlated status ratings with a number of parameters having a possible influence on the perception of occupational status (Dam and Zethsen 2009). What we found to be most important to translators was relatively “soft” parameters such as responsibility and appreciation.

It is important to emphasise that our comparisons of the three groups did in fact lead us to identify more similarities than differences. Whereas the differences between the groups were often found to be small, subtle or statistically speaking non-existing, lots of general patterns run through the entire sample. For one thing, all the translators rated their occupational status as low, below the midscale value of 3. Secondly, their income generally turned out to be low. The “below average” responses constituted 94%, 83% and 70% in the three groups’ total responses – a remarkably low level of income for all three groups. Thirdly, all the groups reported having a relatively low level of visibility – company translators just over the midscale value of 3, but still not high (3.26), agency translators below the midscale value (2.85) and for freelancers it was dramatically low (2.05). Fourthly, a low degree of influence turned out to be a common denominator – all the ratings were below an average of 3 and two of them even below an average of 2 (2.57, 1.80 and 1.87, respectively). Again, this is dramatically low. A fifth similarity is that the translators truly see themselves as highly skilled experts, with self-assessed expertise ratings above 4 by all groups (4.09, 4.67 and 4.69, respectively), but they also agree that their expertise is not recognized by others. All in all, there are more similarities than differences in the sample, and the overall relatively low-status picture of all three groups of translators, in spite of their strong professional profiles, is probably the most robust finding of the entire investigation.

It remains to be seen whether it is possible to identify a high degree of occupational prestige for those who are generally considered the highest status translators of all, i.e., conference interpreters and translators working for the EU or similar international organizations. These groups will be the focus in our next study in our on-going investigation of translator status, which we are presently extending to include qualitative analyses in order to move from description to explanation and from there hopefully to action.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Nyrup Madsen, Tanja (2006): Danskernes nye rangorden. Ugebrevet A4. Updated last on 23 October 2006. Visited on 28 October 2009, http://www.ugebreveta4.dk/2006/36/Baggrundoganalyse/Danskernesnyerangorden.aspx.

-

[2]

According to the Danish Commerce and Companies Agency, contacted on 4 August 2009.

-

[3]

One Euro corresponds to approximately 7.50 Danish Kroner (DKK), and one US Dollar to approximately 6.00 DKK.

-

[4]

According to statistics from DM, one of the main Danish trade unions for MA graduates.

-

[5]

In many large translation agencies, it is not the translators themselves who have direct contact with the clients, and the question is therefore more relevant than it may seem at first glance.

-

[6]

Freelance translators, on the other hand, virtually always have direct contact with their clients (except when they translate for agencies), and it would not be relevant to ask this group about their visibility in relation to their clients.

Bibliography

- Baker, Mona, ed. (1997): The Routledge encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London/New York: Routledge.

- Chan, Andy Lung Jan (2005): Why are most translators underpaid? A descriptive explanation using asymmetric information and a suggested solution from signalling theory. Translation Journal. 9(2). Visited on 13 August 2009, http://accurapid.com/journal/32asymmetric.htm.

- Chesterman, Andrew and Wagner, Emma (2002): Can Theory Help Translators? A Dialogue Between the Ivory Tower and the Wordface. Manchester/Northhampton: St. Jerome.

- Dam, Helle V. and Zethsen, Karen Korning (2008): Translator status. A study of Danish company translators. The Translator. 14(1):71-96.

- Dam, Helle V. and Zethsen, Karen Korning (2009): Who said low status? A study on factors affecting the perception of translator status. JoSTrans - Journal of Specialized Translation. 12:2-36.

- Dam, Helle V. and Zethsen, Karen Korning (2010): Translator status – helpers and opponents in the ongoing battle of an emerging profession. Target. 22(2):194-211.

- Diriker, Ebru (2004): De-/Re-Contextualizing Conference Interpreting: Interpreters in the Ivory Tower? Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Fraser, Janet (2004): Translation research and interpreting research: Pure, applied, action or pedagogic? In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation Research and Interpreting Research. Traditions, Gaps and Synergies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 57-61.

- Freidson, Eliot (1970): Professional Dominance: The Social Structure of Medical Care. New York: Atherton Press.

- Gile, Daniel (2004): Translation research versus interpreting research: Kinship, differences and prospects for partnership. In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation Research and Interpreting Research. Traditions, Gaps and Synergies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 10-34.

- Greenwood, Ernest (1957): Attributes of a profession. Social Work. 2(3):45-55.

- Hermans, Johan and Lambert, José (1998): From translation markets to language management: The implications of translation services. Target. 10(1):113-132.

- Koskinen, Kaisa (2000): Institutional illusions. Translating in the EU Commission. The Translator. 6(1):49-65.

- Lefevere, André (1995): Translators and the reins of power. In: Jean Delisle and Judith Woodsworth, eds. Translators Through History. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 131-155.

- Ollivier, Michèle (2000): “Too much money off other people’s backs”: Status in late modern societies. The Canadian Journal of Sociology. 25(4):441-470.

- Risku, Hanna (2004): Migrating from translation to technical communication and usability. In: Gyde Hansen, Kirsten Malmkjaer and Daniel Gile, eds. Claims, Changes and Challenges in Translation Studies. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 181-195.

- Risku, Hanna and Dickinson, Angela (2009): Translators as networkers: The role of virtual communities. Hermes. 42:49-70.

- Schäffner, Christina (2004a): Researching translation and interpretation. In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation Research and Interpreting Research. Traditions, Gaps and Synergies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1-9.

- Schäffner, Christina ed. (2004b): Translation Research and Interpreting Research. Traditions, Gaps and Synergies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Sela-Sheffy, Rakefet (2005): How to be a (recognized) translator. Rethinking habitus, norms, and the field of translation. Target. 17(1):1-26.

- Sela-Sheffy, Rakefet and Shlesinger, Miriam (2008): Strategies of image-making and status advancement of translators and interpreters as a marginal occupational group. A research project in progress. In: Anthony Pym, Miriam Shlesinger and Daniel Simeoni, eds. Beyond Descriptive Translation Studies. Investigations in Homage to Gideon Toury. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 79-90.

- Snell-Hornby, Mary (2006): The Turns of Translation Studies. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Venuti, Lawrence (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation. London/New York: Routledge.

- Weiss-Gal, Idit and Welbourne, Penelope (2008): The professionalisation of social work: a cross-national exploration. International Journal of Social Welfare. 17(4):281-290.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Translator status[*] as perceived by the company, agency and freelance translators

Figure 2

The company, agency and freelance translators’ monthly income expressed as below average, average and above average with respect to the income of a group of comparable professionals

Figure 3

Degree of expertise[*] required to translate as assessed by the company, agency and freelance translators

Figure 4

The degree of professional contact of company, agency and freelance translators[*]

Figure 5

The company, agency and freelance translators’ perception of the degree of their visibility[*]

Figure 6

The company, agency and freelance translators’ perception of the degree of influence connected with their job[*]