Résumés

Abstract

Building on a common view of translation as a human intentional activity, this article presents a translation studies thesaurus in which all concepts from the multitude of different translation studies areas listed in Baker (1998a), the “Bibliography of Translation Studies” (1998-), Williams and Chesterman (2002) and the “EST-Directory 2003” are brought together on a single map that revises Holmes’s map (1972). Additional practical advantages for the study of translation studies are pointed out.

Keywords:

- translation studies,

- Holmes’s map,

- thesaurus,

- meta study

Résumé

Cet article perçoit la traduction comme une activité humaine intentionnelle et présente un thésaurus des études de la traductologie. Il contient tous les concepts de la multitude des différents domaines de la traductologie dans Baker (1998a), la « Bibliography of Translation Studies » (1998-), Williams and Chesterman (2002) et la « EST-Directory 2003 ». Tous sont réunis dans une seule carte qui révise la carte de Holmes (1972). Des avantages pratiques additionels pour la traductologie sont mis en relief.

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

The proliferation of translation studies from the second half of the twentieth century until now has produced a multitude of approaches, models, concepts and terms. Translation studies has become a labyrinth of ideas and findings in which it is hard to find one’s way and about which explicit consensus has been formulated fairly rarely. However, within the framework of the Bologna-agreement, European Union institutions are now obliged to work towards transparency and mutual recognition of degrees, a fact that stimulates translation studies to reflect on its own status. Recent surveys of the field’s contents can be found in Baker (1998a), the “Bibliography of Translation Studies” (1998-), Williams and Chesterman (2002) and the “EST-Directory 2003.” These overviews are very incongruent, however: the few subdivisions of types of translation studies areas that are marked clearly differ from one another, and, taken together, these contributions result in a collection of fairly long lists of translation studies approaches that lack a consistent basis. Consequently, one still turns to Holmes’s map of translation studies to build some coherence into the complex collection of theories and findings about translation. The present article explains why Holmes’s map is inadequate for this purpose, outlines its shortcomings and develops an alternative.

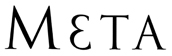

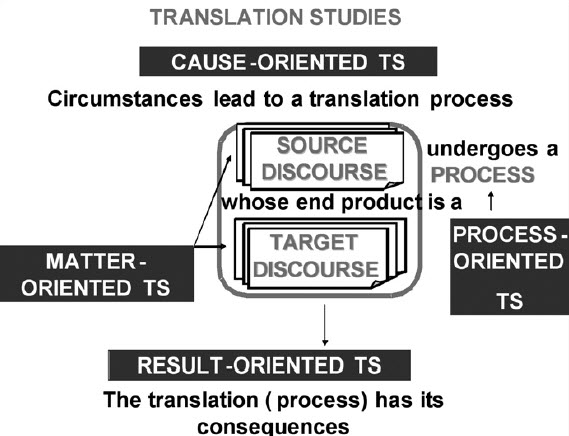

2. Translation as a state of affairs within a causal sequence

There is no question in translation studies that translation is an act of human communication. Even more generally speaking, translation is an intentional human activity that is carried out by an agent. Whether one distinguishes translational types like Jakobson (1959), follows Hermans’s scheme of the communicative process of translation (1998: 155), applies Delisle et al.’s “Steps of a Translation” (1999) or even Bloemen and Segers’s Dutch translation of those steps (2003), with its different order and nomenclature (2003), under all views, the translation activity is applied by a human agent to an object, the source text or source discourse, and the result is a new product, i.e., the target text or target discourse. This activity takes place in certain circumstances: with certain means in a certain place at a certain time. As we will see, it is important to recognize that this activity constitutes one distinct state of affairs[2] on its own (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Translation as a state of affairs

Indeed, some of the circumstances preceding the activity of translation may be seen as the causal factors of translation. Like any other activity, translation is the result of certain willed circumstances. In addition, it also has its own consequences, so that it can be seen as the middle stage in a causal sequence (Chesterman 2000; Figure 2). Since an important characteristic of translation is the fact that the source and target discourses usually belong to different cultures, the translation activity is also a intercultural process.

Figure 2

Translation as a state of affairs in a causal sequence

3. Holmes’s map of translation studies

Presenting a survey of what happens within translation studies is a complicated task. Holmes made the first attempt in 1972. This map (Figure 3) is widely accepted (Baker 1998b: 277b) and consists first of a division into pure and applied translation studies. Pure translation studies is subdivided into theoretical and descriptive translation studies, and applied translation studies is subdivided into translation training, translation aids and translation criticism. Descriptive translation studies is further subdivided into process-oriented, product-oriented and function-oriented studies. There is a further subdivision[3] but I would like to return to the descriptive translation studies because it is these studies, according to Toury in his volume on descriptive translation studies (1995; cf. also Baker 1998b: 279), that are so closely interrelated that they do not need to be separated. Toury also points out another interrelationship in the map, i.e., that between the pure studies and the applied ones and says that the former should influence the applied extensions and not vice versa.

Figure 3

Holmes’s map

However, Holmes’s map is marred by conceptual and heuristic inconsistencies that become apparent when his terms are submitted to the norms developed in the discipline of terminology. In terminology (Aitchison et al. 2000), a field closely related to translation studies, terms, Lead Terms, may conceptually cover different types of Narrow Terms. These different classes are indicated by means of ‘type by …’ followed by a particular criterion. In the following extract from a mini-thesaurus, two criteria for subdividing among human beings are age and gender:

-

LT: Human beings

-

Types by age

-

NT: children

-

NT: adults

-

NT: elderly

-

-

Types by gender

-

NT: males

-

NT: females

-

-

If this thesaurus needs to include another characteristic along which all human beings can be classified, for instance, the language they speak, it will not be entered into one of the subclassifications above, but as a third criterion, viz. ‘type by language’ of ‘human beings’:

-

LT: Human beings

-

Types by age

-

NT: children

-

NT: adults

-

NT: elderly

-

-

Types by gender

-

NT: males

-

NT: females

-

-

Types by language

-

NT: Afro-Asiatic

-

NT: Sino-Tibetan

-

NT: Indo-European

-

NT: Iroquoian

-

NT: Arawakan

-

NT: Austronesian

-

…

-

-

It is precisely this consistent application of criteria which is missing in Holmes’s map. The first distinction in his map, between pure translation studies branches and the applied ones, is based on what one could call the purpose of the study: pure branches aim at knowledge, whereas applied sciences also aim at a particular change. Looking at the subdivision of the pure studies no longer reveals the criterion of purpose, but rather that of method. This criterion is, however, not used for the subdivision among the applied studies: they are further subdivided according to the subject they focus on (Figure 4). This is the point at which the consistency is interrupted: both criteria of ‘method’ and ‘subject’ are not exclusively reserved for the subclassification into which Holmes has put them. Indeed, applied studies, too, rely on theoretical frameworks: all topics within translation studies can be described objectively by means of a theoretical framework. And applied translation studies are also based on empirical findings, a fact which Toury tries to solve by pointing out the interrelationships. In Holmes’s map, however, theoretical and descriptive translation studies are restricted to the domain of pure studies only. Conversely, pure studies may also cover topics that are the alleged province of applied translation studies. Clearly, as Toury pointed out, too, translation theory and applied translation studies are not separate entities.

Figure 4

Criteria in Holmes’s map

This criterion of inconsistency leads to further problems with Holmes’s map. Toury, for instance, rightly notes that Holmes “neglected to duplicate his division of the theoretical branch into ‘partial theories’ in descriptive translation studies” (1995: 11 n.5). But there are more troublesome points. One is the separation between translation aids (among the applied sciences) and the translation process (among the pure ones). Obviously, translation tools, which Holmes would classify among translation aids, are used to facilitate the translation process and should form an integral part of that process.

Another problem is the presentation of product, process and function as colleague terms. According to the definition, product and process are both definitional entities of the translation event. Function, however, refers to one of the important results of the translation: it is a state of affairs in itself. Even though its “envisaging” may be interacting with the translation process, it is temporally quite distinct from the other two.

4. Remapping translation studies

The new map presents its categories according to a rigid set of criteria, placing all kinds of translation studies into a coherent visualized survey. The map elements are all translation studies areas taken from the lists drawn up by Holmes (1972), Baker (1998a), the “Bibliography of Translation Studies” (1998-), Williams and Chesterman (2002) and the “EST-Directory 2003.” Starting-point for this new map is the notion of scientific or academic discipline. Since any academic discipline – whether it be literary studies, Asian, Buddhist, medieval, gender or strategic studies, sociology, psychology, medicine, or physics – has its own purposes, its own methods, and its own object (which can be split up into various parts), the map distinguishes the following three typologies of translation studies:

-

translation studies typology based on the purpose aimed at, in other words the research question that is formulated;

-

translation studies typology based on the method employed; and

-

translation studies typology based on the subject covered.

These typologies are not fixed regiments with their fixed number of soldiers. Instead, they provide labels for distinguishing the specific character of a particular study within the various typological contexts that each study participates in. Each study can – and in a field bibliography needs to – be characterized by means of a label from each of the three different typologies. Needless to say, an investigation may have more than one purpose, use different methods, and cover different areas of the translation studies field.

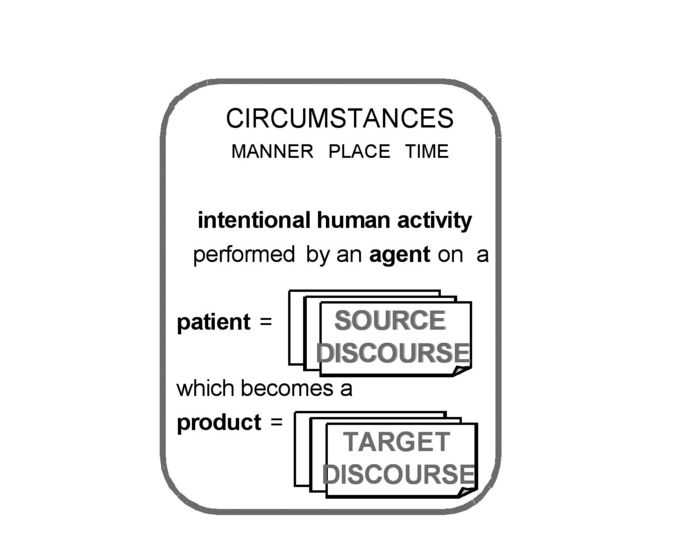

4.1. Translation studies typology based on the purpose aimed at

Research involves at least three different stages: description, explanation and prediction. Descriptive translation studies or DTS (Toury 1995) can therefore be distinguished from explanatory translation studies (e.g., Gutt 2000) and from predictive translation studies (e.g., Olohan 1998). Note that Toury (1995) actually includes the three types within his ‘descriptive translation studies.’ And although the best theoretical studies indeed include these three types, those focussing on just one research stage may also be worthwhile and contribute to a translation theory (Holmes’s ‘pure translation studies’ 1972, “Bibliography of Translation Studies” 1998-, Venuti 2004) or translatology in its broad sense (e.g., Uwajeh 2002).

The three different knowledge-oriented types of studies differ from those studies that aim at something beyond pure knowledge, i.e., some or other outcome or change (see also Figure 5). These are usually normative studies: with the new knowledge achieved, they also aim at particular norms, standards, or practical outcomes. Most of those studies (but not all) are found among Holmes’s ‘applied translation studies.’ They include many models within translation teaching that aim at students performing translation in a certain way: Lederer’s interpretive model (1980 and 1981) or teaching models proclaiming particular translation ethics are good examples. Other less purely knowledge-oriented studies include cultural translation (with its performative theory) or translation ethics (studies that discuss and prescribe a particular type of ethics, starting from specific but not always specified cultural and ideological norms).[4]

Figure 5

Categorization according to purpose

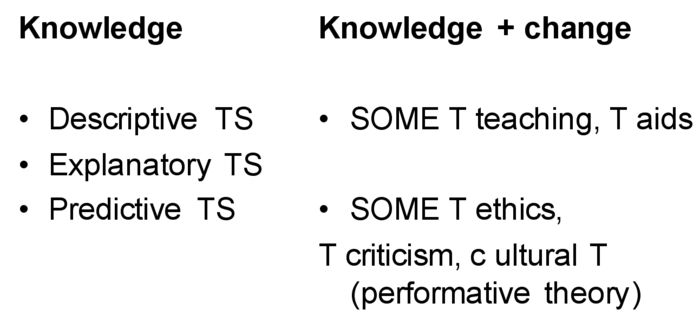

4.2. Translation studies typology based on the method employed

To a large extent, each investigation method is determined by the purpose and the subject. The map distinguishes four main types: deductive translation studies, experimental approaches, speculative ones and inductive translation studies (incl. corpus-based studies, e.g., Olohan 2004) with its qualitative, quantitative and hermeneutic approaches.

Some fields of translation study also apply methods typically related to their field: linguistic, neurolinguistic, cognitive, psycholinguistic, behavioural, communicative / functional, semiotic, sociological approaches in interpreting, etc. Figure 6 illustrates the diversity of methodological approaches:

Figure 6

Categorization according to method

4.3. Translation studies typology based on the subject covered

It is the third type of typology that is most commonly used in science: it groups studies according to the subject under investigation. This may vary from a very specific aspect to a broader subject and even a whole field or domain. For practical purposes, the investigations studying a single item of the translation process will be referred to as the single-subject studies, the studies covering more than one single focus as multi-focus studies,[5] and those that cover all foci will be called ‘umbrella’ studies.

5. Single-subject studies: four translation studies foci

In building a subject-based typology or ontology of translation studies, it is useful to start from the translation situation and to distinguish four translation foci. Two are derived from the definition of translation (discourse and process) and two come from the causal view that is taken (cause and result).

In the definition of translation two types of foci can be distinguished. On the one hand, there is the translation process itself with all its component processes: all the activities and change-inducing events involved in the translation process (5.1). On the other hand, the process is applied to some discourse, viz. the source text / discourse, and the outcome is a second piece of discourse, viz. the target text / discourse or product (5.2).

Both the translation process and the discourse to which it is applied are to be found in a particular situation: the translation process is one link in a causal chain, with some circumstances, i.e., the causal factors, leading to the translation process (5.3), and with some circumstances, i.e., the results, derived from the translation process (5.4). Cause and result are, indeed, the other two translation foci. For a survey, see Figure 7 below:

Figure 7

Categorization according to subject

5.1. Process-oriented studies

The process-oriented translation studies collate with Holmes’s process-oriented studies: they focus on the process of translating itself. Research questions here deal with various aspects of the translation process: individuals’ translation competence and its development, and the actual performance of the translators within their professional situation.

a. Translation competence research

In translation competence research, translators are seen as individuals going through the translation process and taking many decisions, e.g., in translation commentaries (considering either introspective or retrospective aspects of the translation process). Decisions are taken consciously or unconsciously: they may involve translation strategies[6] (aiming at equivalence, explicitation, free translation vs. literal translation[7] vs. sense-for-sense translation (Jerome AD 395), rank-bound vs. unbounded translation (Catford 1965), imitation, metaphrase, paraphrase, pseudotranslation, adaptation, domestication vs. foreignization, etc.) or linguistic translation techniques (leading to linguistic translation shifts). Whether the translation process takes place with or without technological aids, studies of translation and technology also belong to this type of translation study, i.e., studies of machine(-aided) translation, (evaluation of) translation software, localizing software, the effects of technology and website translation (Williams and Chesterman 2002: 14-5). Very often, translation decisions are influenced by (un)conscious ideological assumptions: ideology and translation (e.g., Bassnett and Lefevere 1990). The directionality of the translation, too, may influence the translation process. Other issues related to translation competence are translatability and the functioning of the translation unit as the input of the translation process, game theory (e.g., Levý 1967) and obtaining Walter Benjamin’s ‘pure language’ (Bush 1998: 194-196).

b. Translation competence development research

How to improve students’ translation competence is a very frequent subject in translation studies: translation teaching / training / didactics forms a fruitful field of study (for instance, the Paris school teaching model of interpretive translation). The area includes issues such as translation curriculum design, programme implementation, translation assessment or evaluation, translator training institutions and the place of technology in translation training (Williams and Chesterman 2002: 16).

c. Translation profession research

The translation profession as such generates scholarly attention too, regarding issues such as the workplace (incl. societies like AIIC and FIT), professional development and other professional issues, ethics (sometimes made explicit in codes of practice, cf. Williams and Chesterman 2002: 19) and quality assessment of professional translations, i.e., translation quality.

5.2. Discourse-oriented studies

The discourse-oriented studies cover Holmes’s product-oriented studies and can moreover be seen to correspond to Chesterman’s source-target supermeme (2000a). They should be subdivided into two main categories: either they investigate both the source and target texts and are therefore of a comparative nature (Williams and Chesterman 2002: 6-7) or they look at texts in general and belong to the collection of what has often been referred to as the ‘auxiliary studies’ in translation studies.

Among the comparative discourse-oriented translation studies, we can count studies comparing source with target texts – whether or not corpus-based. Examples are source-oriented translation quality assessment studies (Williams and Chesterman 2002: 8), and studies that investigate language-related contrasts relying on methods from contrastive linguistics, contrastive pragmalinguistics, contrastive pragmatics, or contrastive discourse analysis (one research question could be: what happens to the multilingualism in a source text?) Other investigations rather focus on the similarities in different discourses (and rely on comparative linguistics). Discourse-oriented studies also include contrastive area studies (with research questions like “what are the cultural, political, economic institutions in one area and what are their equivalents in another area?”) and analytical philosophy, which claims that translation is indeterminate (Quine) because it is impossible for source and target texts to have the same meaning.

Further, some comparative discourse-oriented studies compare translations with a corpus of comparable, non-translated texts as in studies of translation universals and target-language oriented translation quality assessment (Williams and Chesterman 2002: 8).

Among the non-comparative discourse-oriented translation studies belong discussions of translation anthologies (Essman 1992) and of script in translation. Most studies, however, look at features of texts within just one language or at those features that are seen as universal. They include linguistics (semantics, syntax, phonology), text linguistics, textology, translation of humour / wordplay / metaphor, critical linguistics, applied linguistics, stylistics, terminology (incl. term banks, applications, standardization), terminography, lexicology, lexicography, terminotics, thesaurus / ontology building, semiotics, or discourse studies, incl. dialogue language and technical writing. Since interpretation is essential to the translation process, the map introduces automatic content retrieval as a new area.

5.3. Cause-oriented studies

Studies focussing on the cause of the translation process usually investigate translation politics and translation publishing strategies. Discussions of translation and ethics or socio-political aspects belong to this type of translation studies. Researchers also consider cultural and ideological factors that have influenced translation (power, colonialism, cultural identity) and zoom in on notions such as the ethnocentric violence of translation (Venuti 1995) and the cultural turn in translation studies (Bassnett and Lefevere 1990).

5.4. Result-oriented studies

Result-oriented studies primarily concentrate on the consequences resulting from a certain translation (activity). This may be its effectiveness, the topic of effect-oriented translation quality assessment studies (Williams and Chesterman 2002: 8-9), or how a certain translation (activity) functions either in language teaching or at a more general level (Holz-Mänttäri’s action theory, Vermeer’s skopos theory, Even-Zohar’s polysystem theory) or how it contributes to the construction of an ethics, or a literary canon, or a cultural identity (translation and cultural identity, the translator’s invisibility Venuti 1995).

6. Multi-focus and ‘umbrella’ studies

These single-subject studies are complemented by studies whose research questions involve more than one subject focus. The areas of discourse and process are often considered together, as is evident in examinations of the direction of translation (incl. bi-directionality), hermeneutic motion,[8] and in translation commentaries relating the target text to the translation process. Both discourse and result play a major role in translation reviewing and criticism as well as in other quality assessment studies. Cause and result are focussed in studies of translational norms[9] (e.g., Toury 1995: 53). You will also find them in investigations discussing translation ethics and Otherness or the image of the Other (cf. Chesterman’s supermeme of untranslatability, 2000a). Cause, discourse and result are subjects in the poetics of translation, which compares the “poetics of a source text in its own literary system” (Gentzler 1998: 167) with that of the translation in the target literary system.

Sometimes, studies even cover all four foci, and may thus be classified as ‘umbrella’ studies, which relate the four subjects to one particular aspect or perspective. Register[10] translation studies, for instance, focus on a particular type of register: religious translation (incl. a.o. Bible, Torah, and Qur’ān translation), the translation of political texts and of texts within LSP (Language for Specific Purposes), which covers business, advertising, tourism, academic, legal and technical texts. Literary translation studies also deals with all aspects of translation: Shakespeare translation is a profoundly developed topic, but scholars investigate all genres (prose, poetry and drama [theatre and opera]) both for adults and children, relying on (comparative) literature studies.

Translation criticism,[11] too, belongs to the umbrella studies: not only may its prescriptive approach be related to the translation-initiating circumstances, or to the function of the translation in the target audience, it is also related to how the translation should be processed or which texts are (in)appropriate for translation.

The study of auto-translation is another umbrella study. Focussing on self-translations, it comments on those translation situations in which the two most central actors, i.e., the source text writer and the translator, are represented by the same person or institution.

Similarly, interpreting studies should be classified among the umbrella studies: they deal with those specific translation situations where either source text and / or target text is spoken or where the translation appears immediately: conference interpreting, community interpreting, court interpreting, chuchotage, liaison interpreting, sight translation, interpreting for the blind, multimedia translation (incl. voice to written text translations [subtitling, surtitling incl. technological aids] and revoicing [incl. narrator, free commentary, voiceover and lip-sync dubbing], etc.). A special instance is that of sign language interpreting studies which focuses on those interpreting performances in which the discourse consists of (manual) gestures. In all interpreting situations, studies may be both discourse-, process-, cause- and result-oriented.

More traditional perspectives for translation study are space and time, embracing ‘history of translation’ studies or investigations of ‘translation in’ a particular geographic area (cf. all translation traditions determined by place / language in Baker 1998: 295ff). These studies may in principle cover the same wide collection of subjects that translation studies as a whole does. Or a study may even be written from both a temporal and a spatial perspective (‘(post-)colonial translation’). Another perspective is that of gender, where one investigates the gender of authors translated or of translators (e.g., Simon 1996 and von Flotow 1997). Finally, scholars have also investigated the ideological, socio-political or pragmatic aspects of translation in general.

7. Towards a Translation Studies Ontology

I have presented a thesaurus of translation studies (translation studies) which is seen as part of intercultural communication studies, and presumes its own meta-level, i.e., its own bibliography and the study of itself, incl. its research methodology[12] and its research training.

The map further contains categorizations of translation studies that are research purpose-based, research method-based and research subject-based. Figure 8 presents a brief survey of the types of translation studies proposed:

Figure 8

Translation studies survey

Using these classes, a universal thesaurus can now be built. In the appendix, the reader will find a translation studies thesaurus in which all the areas mentioned above are entered into their respective places. The thesaurus does not only incorporate all the various narrow terms of translation studies, but also a few related terms: in particular, some concepts that often appear in those fields, e.g., literal translation, directionality in translation studies, codes of practice, etc. are also included. As such, the thesaurus has the initial traits of an ontology[13] under development.

The thesaurus is presented as a proposal, an invitation for discussion. Since it is a survey of a research field from a particular moment in time, it does not claim to be exhaustive, neither will it ever be final. As it is just the outset of a type of scholarly work surveying the ideas and models of every scholar involved in the field of translation studies, it is in need of refinement and completion through the cooperation of many.

8. Advantages

Like any other thesaurus, this one offers a clear, consistent and coherent system for the analysis of concepts and fields in translation studies. Not only will translation studies scholars benefit from this visually consistent presentation: its inherently didactic qualities will also promote translation studies among students.

Although the thesaurus is set up in English, its conceptually open structure allows inclusion of concepts from any culture. While translating the thesaurus into different languages will show up conceptual differences between languages, this does not mean that the thesaurus is culturally bound: on the contrary, all cultural differences are made visible and transparent, and in this way, it will contribute to knowledge sharing across cultures.

Apart from facilitating systematic indexing for bibliographic entries into a translation studies bibliography (whether the one published by Benjamins or the one by St. Jerome’s), the thesaurus also has practical advantages: its map structure makes it possible to integrate all individual research activities of an institution into one system. The so-called research lines of a school can easily be made visible on a poster: the subject-based typology has proved suitable as a template that allows the Ghent School of Translation Studies to present its own research areas visually (Figure 9). Using the map as a template in this way will enable comparison of research activities in different translation schools worldwide. In the end, it will promote understanding, cooperation, and innovative research.

Figure 9

Ghent School of Translation Studies Map (October 2003)

Is the exercise worthwhile? Any academic discipline broadens and deepens human understanding. In addition, translation studies is unique in that its object is just one human act, an act which crosses borders between languages and cultures, extremely complex as it may be and however different the forms it may take. What is special about this human act, about translation, is that it shares with academic disciplines the characteristic of broadening and deepening human understanding.

Parties annexes

Annexe

Appendix

-

LT = Lead Term

-

BT = Broad Term

-

NT = Narrow Term

-

RT = Related Term

-

UF = used for (a synonym with a lower frequency)

translation studies

-

UF translatology[14]

-

BT: intercultural communication studies

-

BT: multi-lingual communication studies

-

•NT: translation studies bibliography

-

•NT: studies of translation studies research methodology

-

NT: studies of the metaphor of translation

-

RT: gender metaphorics

-

-

-

•NT: studies of translation studies research training

-

•Types by purpose

-

NT: Translation theory

-

UF: ‘pure translation studies’

-

UF: translatology

-

UF: models of translation

-

NT: descriptive translation studies

-

NT: explanatory translation studies

-

NT: predictive translation studies

-

-

NT: Normative studies

-

UF: ‘Applied translation studies’

-

NT: translation teaching models

-

NT: translation ethics

-

NT: cultural translation

-

-

-

•Types by method

-

Types by general research methods

-

NT: inductive translation studies

-

NT: corpus(-based) translation studies

-

NT: qualitative approaches

-

NT: quantitative approaches

-

NT: hermeneutic approaches

-

NT: deductive translation studies

-

NT: experimental translation studies

-

RT: think-aloud protocol studies

-

UF: TAP studies

-

-

-

NT: speculative approaches

-

-

Types by field-related research methods

-

NT: linguistic approaches

-

NT: neurolinguistic approaches

-

NT: psycholinguistic / Cognitive approaches

-

NT: behavioural translation studies

-

NT: communicative / Functional approaches

-

NT: semiotic approaches

-

NT: sociological approaches

-

-

-

•Types by subject

-

NT: single-focus translation studies

-

NT: process-oriented translation studies (incl. cognitive processes)

-

NT: studies of translation competence

-

NT: translation commentaries focussing on the process

-

NT: studies of decision making in translation

-

NT: studies of translation strategies

-

RT: adaptation

-

RT: domestication

-

RT: equivalence

-

RT: explicitation

-

RT: foreignization

-

RT: free translation

-

RT: imitation

-

RT: literal translation

-

UF: word-for-word translation

-

UF: metaphrase

-

-

RT: paraphrase

-

RT: sense-for-sense translation

-

-

NT: studies of linguistic translation techniques

-

NT: compensation

-

RT: shifts of translation

-

-

NT: studies of translation and technology

-

NT: machine translation studies

-

NT: machine(-aided) translation studies

-

NT: studies of evaluating software

-

NT: software localization studies

-

NT: studies of effects of technology

-

NT: website translation studies

-

-

RT: directionality in translation

-

RT: translatability

-

RT: unit of translation

-

RT: game theory

-

RT: pure language

-

-

NT: studies of translation teaching

-

UF: studies of translation training

-

UF: studies of translation didactics

-

RT: language teaching studies

-

RT: curriculum design

-

RT: curriculum implementation

-

RT: translation assessment

-

UF: translation evaluation

-

-

RT: translator-training institutions

-

RT: place of technology in translator training

-

-

NT: translation profession studies

-

NT: workplace studies

-

RT: professional development

-

RT: codes of practice

-

RT: translators’ organizations

-

NT: AIIC

-

NT: FIT

-

-

RT: translation quality

-

UF: translation quality assessment

-

-

-

-

NT: discourse-oriented translation studies

-

NT: comparative discourse-oriented translation studies

-

NT: source-oriented translation quality assessment studies

-

RT: multilingualism in translation

-

-

NT: target-oriented translation quality assessment studies

-

RT: comparable texts

-

RT: translation universals

-

-

RT: contrastive linguistics

-

RT: contrastive pragmalinguistics

-

RT: contrastive pragmatics

-

RT: contrastive discourse analysis

-

RT: comparative linguistics

-

RT: contrastive area studies

-

RT: analytical philosophy

-

-

NT: non-comparative discourse-oriented translation studies

-

RT: anthologies of translation

-

RT: script in translation

-

RT: applied linguistics

-

RT: textology

-

RT: linguistics

-

NT: Semantics

-

NT: syntax

-

NT: phonology

-

RT: text linguistics

-

UF: textology

-

-

RT: sociolinguistics

-

RT: critical linguistics

-

-

RT: stylistics

-

RT: discourse studies

-

RT: dialogue language

-

RT: critical discourse analysis

-

RT: technical writing

-

-

RT: translation of humour

-

RT: translation of wordplay

-

RT: translation of metaphor

-

RT: lexicography

-

RT: lexicology

-

RT: terminology

-

RT: term banks

-

RT: glossaries

-

-

RT: terminography

-

RT: terminotics

-

RT: thesaurus building

-

RT: ontology building

-

RT: semiotics

-

RT: automatic content retrieval

-

-

-

NT: Cause-oriented translation studies

-

RT: publishing strategies

-

RT: translation politics

-

RT: ethnocentric violence of translation

-

RT: the cultural turn in translation studies

-

-

NT: Result-oriented translation studies

-

NT: effect-oriented translation quality assessment studies

-

RT: action theory

-

RT: skopos theory

-

RT: theory of translatorial action

-

RT: polysystem theory

-

RT: the translator’s invisibility

-

RT: translation and cultural identity

-

RT: translation and ethics

-

-

-

-

NT: Multi-focus translation studies

-

NT: Umbrella translation studies

-

NT: Interpreting studies

-

RT: community interpreting

-

RT: court interpreting

-

RT: simultaneous interpreting

-

RT: conference interpreting

-

RT: chuchotage

-

RT: liaison interpreting

-

RT: sign language interpreting

-

UF: signed language interpreting

-

-

RT: sight translation

-

RT: interpreting for the blind

-

RT: audiovisual translation

-

UF: media translation

-

UF: multi-media translation

-

NT: revoicing

-

NT: dubbing

-

UF: lip-sync dubbing

-

-

NT: voice-over

-

NT: narration

-

RT: narrator

-

-

NT: free commentary

-

-

NT: subtitling

-

NT: surtitling

-

-

-

NT: Register translation studies

-

RT: religious translation

-

NT: Bible translation

-

NT: Koran translation

-

NT: Torah translation

-

-

RT: translation of political texts

-

RT: translation and politics

-

-

RT: LSP translation

-

UF: specialized translation

-

NT: academic translation

-

UF: scientific translation

-

-

NT: translation of tourism texts

-

NT: translation of business communication

-

UF: economic translation

-

NT: translation of advertising

-

-

RT: business communication studies

-

NT: legal translation

-

NT: court interpreting

-

-

NT: technical translation

-

-

-

RT: literary translation

-

UF: translation and literature

-

NT: genre translation

-

NT: drama translation

-

NT: theatre translation

-

NT: opera translation

-

-

NT: poetry translation

-

NT: prose translation

-

UF: fiction translation

-

-

-

NT: Shakespeare translation

-

RT: children’s literature and translation

-

RT: literary studies

-

RT: comparative literature studies

-

-

NT: translation ciriticism

-

RT: auto-translation

-

RT: translation and gender

-

RT: feminist translation

-

-

RT: history of translation

-

RT: intertemporal translation

-

RT: ideology and translation

-

RT: socio-political aspects of translation

-

RT: pragmatics of translation

-

-

Examples of multi-focus subject studies

-

Discourse and process

-

RT: hermeneutic motion

-

RT: direction of translation

-

RT: translation commentaries relating the target text to the process

-

-

Discourse and result

-

RT: translation reviewing and criticism

-

RT: quality assessment

-

UF: translation evaluation

-

-

-

Cause and result

-

RT: translation ethics

-

RT: personal vs. professional ethics

-

-

RT: norms

-

RT: image of the Other

-

RT: untranslatability

-

RT: cultural and intercultural studies

-

RT: postcolonialism

-

RT: postmodern theories

-

RT: translation and cultural identity

-

-

-

Cause, discourse and result

-

RT: poetics of translation

-

-

Process, discourse and result

-

RT: localization

-

-

-

Notes

-

[1]

The present text is a revised version of the paper presented at Doubts and Directions, 4th Congress of the European Society for Translation Studies, Lisbon 2004. I would like to thank all colleagues for their comments, in particular F. Pöchhacker and R. Setton. I am also indebted to W. Vandeweghe for reading an earlier version.

-

[2]

The term ‘state of affairs’ is used in its broad philosophical sense to include all types of situations: actions, activities, events, processes and states (Wetzel 2003).

-

[3]

Theoretical studies are subdivided into ‘General’ and ‘Partial,’ and the latter are further subdivided into 6 subtypes.

-

[4]

To illustrate this type, an example of a study that is both descriptive and normative at the same time is Arnaud Laygues’s ‘Death of a Ghost: A Case Study of Ethics in Cross-Generation Relations between Translators’ (St. Jerome Publishing’s 2001), in which an ethical problem – a young translator having been exploited by one of her seniors – is explained by means of Marcel’s concept of fidelity and Bourdieu’s habitus (descriptive part) and in which solutions are suggested such as offering young translators more practical information during their initial training and providing better support from professional associations (normative part).

-

[5]

The multi-focus studies are different from Btranslation studies’ ‘multi-category works’ (e.g., 2003), which are not restricted to different foci as research objects.

-

[6]

Note the interrelationship between some strategies and the purpose or result aimed at with the translation (see 5.4).

-

[7]

Other terms are: word-for-word translation and metaphrase (coined by Dryden 1680).

-

[8]

The hermeneutic motion (George Steiner 1975) sees translation as a hermeneutic act going through four stages: surrender to the source text, aggressive interpretation of it, assimilative incorporation and final restitution of its properties. The translator trusts “there is “something there” in the source text, something to be understood, something worth translating” (Chesterman 2000a: 180).

-

[9]

Toury (1977) sees the establishment of norms as the very epitome of a target-oriented approach: they determine the suitability of the role played by the translated text in a given cultural environment, so the translator must know them.

-

[10]

Williams and Chesterman refer to these studies as ‘genre translation’ (2002: 9ff).

-

[11]

The prescriptive approach in translation criticism can be easily justified in terms of describing a particular translation as the most relevant one or not relevant enough for a particular audience, in a particular place and at a particular time.

-

[12]

The former contains, amongst others, studies that focus on the metaphor of translation, such as gender metaphorics (Baker 1998a).

-

[13]

The term ‘ontology’ is used in the following sense: “a specification of a domain, of all that ‘exists’ in a domain, including terms, concepts, entities, axioms, theorems, laws, rules, and the actions than [sic] can be performed on everything within the domain as well as how to reason about the domain” (Krupansky 2004).

-

[14]

Sometimes, translatology is used in a narrower sense.

References

- Aitchison, J., Gilchrist, A. and D. Bawden (2000): Thesaurus Construction and Use: A Practical Manual, London, Aslib IMI.

- Baker, M. (ed.) (1998a): Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, London, Routledge.

- Baker, M. (1998b): “Translation studies,” in Baker, M. (ed.) Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, London, Routledge, pp. 277-280.

- Bassnett, Susan and A. Lefevere (eds.) (1990): Translation, History and Culture, London and New York, Pinter.

- (1998-): Bibliography of Translation Studies, Manchester, St. Jerome.

- Bush, P. (1998): “Pure language,” in Baker, M. (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, London, Routledge, pp. 194-196.

- Catford, J.C. (1965): A Linguistic Theory of Translation: An Essay in Applied Linguistics, London, Oxford University Press.

- Chesterman, A. (2000a): Memes of Translation. The Spread of Ideas in Translation Theory, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

- Chesterman, A. (2000b): “A Causal Model for Translation Studies,” in Olohan, M. (ed.), Intercultural Faultlines. Research Models in Translation Studies I. Textual and Cognitive Aspects, Manchester, St. Jerome, pp. 15-27.

- Delisle, J., Lee-Jahnke, H. and M. C. Cormier (1999): Terminologie de la traduction. Translation terminology. Terminología de la traducción. Terminologie der Übersetzung, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

- Delisle, J., Lee-Jahnke, H. and M. C. Cormier (2003): Terminologie de la traduction. Translation terminology. Terminología de la traducción. Terminologie der Übersetzung, translated and adapted by Bloemen, H. and W. Segers, Terminologie van de vertaling, Nijmegen, Vantilt.

- Essman, H. (1992): Übersetzungsanthologien: Eine Typologie und eine Untersuchung am Beispiel der amerikanischen Versdichtung in deutschsprachigen Anthologien, 1920-1960. (Neue Studien zur Anglistik und Amerikanistik 57), Frankfurt, Peter Lang.

- European Society for Translation Studies (2003): European Society for Translation Studies Directory 2003, Birmingham, Les, Aston University.

- Gentzler, E. (1998): “Poetics of translation,” in Baker, M. (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, London, Routledge, pp. 167- 170.

- Gutt, E.-A. (20002): Translation and Relevance. Cognition and Context, Manchester, St. Jerome.

- Hatim, B. (1998): “Pragmatics in translation,” in Baker, M. (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, London, Routledge, pp. 179-183.

- Hermans, T. (1998): “Models of translation,” in Baker, M. (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, London, Routledge, pp. 154-157.

- Holmes, J. (1972): The Name and Nature of Translation Studies, unpublished manuscript, Amsterdam, Translation Studies section, Department of General Studies, reprinted in Toury, G. (ed.) (1987): Translation Across Cultures, New Delhi, Bahri Publications.

- Holmes, J. (1988): Translated! Amsterdam, Rodopi.

- Jakobson, R. (1959): “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation,” in Brower, R. A. (ed.), On Translation, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, pp. 232-239.

- Krupansky, J. (2004): “Definition: ontology,” <http://agtivity.com/ontology.htm>, [07.11.2004].

- Lederer, M. (1980): La traduction simultanée. Fondements théoriques, Lille, Université de Lille III.

- Lederer, M. (1981): La traduction simultanée. Expérience et théorie, Paris, Minard.

- Levý, J. (1967): “Translation as a Decision Making Process,” in To Honor Roman Jakobson, vol. 2. The Hague, Mouton, pp. 1171-1182.

- Olohan, M. (1998): The Role of Theory in Enhancing the Explanatory and Predictive Aspects of Translation Process Research, Ph.D. thesis, UMIST.

- Olohan, M. (2004): Introducing Corpora in Translation Studies, London and New York, Routledge.

- Pym, A. (ed.). (2001): “The Return to Ethics,” The Translator 7-2, St. Jerome Publishing, <http://www.stjerome.co.uk/translator/vol7.2.htm#laygues>, [14.09.04].

- Pym, A. (2002): “Redefining translation competence in an electronic age. In defence of a minimalist approach,” <http://www.fut.es/~apym/on-line/competence.pdf>, [26.10.2003].

- Schäffner, C. and B. Adab (eds.) (2000): Developing Translation Competence. Benjamins Translation Library 38, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

- Simon, S. (1996): Gender in Translation: Cultural Identity and the Politics of Transmission, Translation Studies, London, Routledge.

- Steiner, G. (1975, 19922, 19983): After Babel, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Toury, G. (1977): Translational Norms and Literary Translation into Hebrew, 1930-1945. Tel Aviv, The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics, Tel Aviv University.

- Toury, G. (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond, Benjamins Translation Library 4, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

- Uwajeh, M. K. C. (2002): “The Task of the Translator Revisited in Performative Translatology,” Babel 47-3, pp. 228-247.

- Venuti, L. (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility, London and New York, Routledge.

- Venuti, L. (ed.) (2000, 20042): The Translation Studies Reader, London and New York, Routledge.

- von Flotow, L. (1997): Translation and Gender. Translating in the “Era of feminism,” Manchester, St. Jerome Publishing.

- Wetzel, T. (2003): “States of Affairs,” in Zalta, E. N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2003 Edition), <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2003/entries/states-of-affairs/>, [07.11.2004].

- Williams, J. and A. Chesterman (2002): The Map. A Beginner’s Guide to Doing Research in Translation Studies, Manchester, St. Jerome Publishing.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Translation as a state of affairs

Figure 2

Translation as a state of affairs in a causal sequence

Figure 3

Holmes’s map

Figure 4

Criteria in Holmes’s map

Figure 5

Categorization according to purpose

Figure 6

Categorization according to method

Figure 7

Categorization according to subject

Figure 8

Translation studies survey

Figure 9

Ghent School of Translation Studies Map (October 2003)