Résumés

Abstract

This article presents an account of the meaning relationship between visual and verbal information in film and the differences between the conventions of making verbal reference to visual information in English films and their German-language versions. The analysis of a diachronic corpus of popular motion pictures and their German-dubbed versions indicates that the film translations ‘handle’ the co-occurring visual information differently than their English source texts. The translations tend to use alternative, non-equivalent, linguistics structures to refer to visual information and insert additional pronominal references and deictic devices, which overtly connect linguistic items to pictorial elements. As a result, the ongoing spoken discourse is explicitly linked with the physical surroundings of the communicative encounter. In contrast, in the English language versions, the relationship between the verbal utterance and the accompanying visual information more often remains lexically implicit. The shifts in translation affect the ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings expressed in the film texts which, in turn, may result in a variation in the films’ narrative construction and the realization of extralinguistic concepts, such as, for example, gender relations.

Keywords/Mots-Clés:

- film texts,

- film translation,

- dubbing,

- multimodality,

- visual-verbal cohesion

Résumé

Cet article présente une étude des relations sémantiques entre les informations visuelles et verbales dans le cinéma et montre les différences entre les conventions de référence aux informations visuelles par les moyens verbaux dans les films en anglais et dans leur version en allemand. L’analyse d’un corpus diachronique de films populaires en anglais et de leur version doublée en allemand montre qu’on traite de manière différente la cooccurrence d’une information visuelle avec une information verbale dans les originaux et leur traduction. Dans la traduction allemande, on tend à introduire des structures linguistiques différentes pour renvoyer à une information visuelle. On insère des références pronominales et d’autres termes déictiques supplémentaires pour lier de manière ostensible un élément linguistique à un élément visuel. Par conséquent, dans la version allemande, le discours verbal est directement lié à son environnement, pendant que, dans les originaux anglais, la relation entre le discours et la scène se manifeste souvent de manière plus implicite sur le plan lexical. Ces différences résultant de la traduction influent sur la signification exprimée sur le plan du texte. Il se peut que – à côté d’autres phénomènes au-delà du texte, comme par exemple les relations de genre – cette variation de la construction narrative du cinéma soit le résultat de la traduction.

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

In his review of research models in audiovisual translation, Chaume (2003) points out two future avenues of investigation in film translation. The focus of future research should be placed on the special kind of textuality of film translations: Firstly, the prefabricated orality (“constructed speech”) in film translations needs to be investigated with respect to the approximation of authentic spoken language and communicative verisimilitude. Secondly, the special textual constitution of a film text needs to be described. This would include investigations into the types of verbal cohesion, the use of visual cohesion ties, such as fade-outs and scene changes, and – crucially – the patterns of interaction and cohesion between visual and verbal information. In this article, I will be concerned with the latter – i.e., the interaction of visual and verbal information in establishing meaning in a film text, its realization in film translation via dubbing, and language-specific conventions of relating verbal to visual information. This calls for an integration of theories and methods from linguistics, visual analysis and cinematic narrative – disciplines which are often considered to be outside the scope of interest of translation studies.

The article is structured as follows. In Section 2, the concept of multimodality and the conception of films as multimodal texts will be introduced. In Section 3, I will first summarize the conceptualization of the relationship between verbal and visual information in translation studies, and, secondly, briefly review the approaches to language use and the interrelation between visual and verbal information in film studies and the field of visual communication. In Section 4, a linguistic model of the relationship between visual and verbal information in film texts will be proposed. Section 5 presents the results of the diachronic investigation of the combination of visual and verbal information in a corpus of English film texts and their German-language versions. Section 6 concludes the article with a brief discussion of these findings in the light of English and German language-specific conventions of making verbal reference to visual information and some implications of an integrative view of the role of visual and verbal information in a film’s meaning construction for film translation.

2. Multimodality

Film can be considered from the perspectives of medium, sign system, and text (cf. Borstnar et al. 2002). Film as a medium can be described as a processing system for information and signs. It is characterized by special conditions of production, exhibition, distribution, and reception. Film can also be seen as a sign system. From this perspective, film is a coherent whole composed of interdependent elements. The relationships between them are governed by specific formal and functional principles concerning, e.g., narrative construction (Bordwell and Thompson 1997). The view of film as text refers to a particular cohesive and coherent formation of signs chosen from the overall film system, which are related to each other by particular actualizations of the formal and functional principles, and which are produced and exhibited by and received through the film medium. What distinguishes the filmic sign system from other sign systems, such as language, visual communication, body language, kinesics, or proxemics, is that it utilizes these other sign systems in the formation of a film text. In a sense, film universally exploits all conceivable extrafilmic sign systems. The meaning of a single film text arises out of the combination of meaningful elements from the film system itself in combination with other elements, which are already endowed with meaning by virtue of their membership in other semiotic systems. Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) call the combination of meanings from different semiotic systems “multimodality.” Multimodal texts are “texts whose meanings are realized through more than one semiotic code” (Kress and van Leeuwen 1996: 183).

A film, thus, is a multimodal text. It consists of different layers of meaning, which are communicated through the photographic image and the sound of the film. The central decision for the conceptualization of the meaning making processes in films and their analysis is whether to take a separate or an integrated approach to the semiotic modes involved. A separate approach presupposes that the meaning of the whole is the sum of the meaning of its different semiotic parts; conversely, the integrated approach starts from the assumption that the parts interact and affect each other in the formation of the whole. In the present context, film texts are understood as integrated texts in the latter sense. I distinguish two main types of semiotic codes along the channels of physical perception: the verbal and the visual. Somewhat simplified for the present purposes, the sound-image correlation in a film text encompasses verbal reference to visual objects. This correlation is understood to contribute to and to shape the patterns of establishing meaning in a film text. In the following section, the understanding of the interaction between visual and verbal information, i.e., multimodality of film texts, in translation studies, film studies, and visual communication will be summarized.

3. Language use in visual media as a research object in translation studies, film studies and visual communication

Translations studies have not yet systematically addressed the role of the interplay between visual and verbal information in establishing the meaning of a film text, and how it may influence both the process of film translation and the finished product. Early accounts of translation theory and practice view the co-occurrence of visual and verbal information in film exclusively in terms of (lip) synchrony. Film translation is seen as a special kind of translation, which poses a medium-specific problem for the translator: The mapping of translated speech onto the visual appearance of the onscreen speaker. Mounin (1967) and Nida (1969), for example, posit three types of visual-verbal synchrony (or “isochrony” in Mounin’s terms) in film translation. They claim that linguistic choice in the translation of a film text is constrained by the primacy of synchrony between the uttered translated text and visible lip movements, between the text and the facial expression of the onscreen speaker, and between the text and the physical activity of the speaking and other participating characters. In this view, visual and verbal information only interact in a meaningful way under particular circumstances, and it is only in the above-mentioned cases that the linguistic choice and the visual information are seen as making a combined contribution to the overall meaning of the film text. Visual and verbal information are not considered as constantly contextualizing each other.

Although films have been featuring spoken language since the late 1920s, speech and dialogue are conspicuously absent from theoretical writings on film and in analytical approaches to film (e.g., Bordwell 1985, 1989; Bordwell and Thompson 1997; Branigan 1984). In film studies, the use of language in film – called “dialogue” or “speech” – is generally considered as one part of film sound. Next to speech, film sound also consists of music and sound effects. Dialogue in particular is understood as the “transmitter of story information” (Bordwell and Thompson 1997: 321) but not necessarily as ranking highest in importance among the overall uses and functions of sound in film. Dialogue, music, and sound effects serve to point out visual information as salient and to distract the viewers from the “technicalities” of the film. Sound is thus primarily a means of addressee orientation: it functions to direct the viewers’ reception of the film. However, this does not necessarily imply that speech is understood as being in a meaningful referential relation to visual information. Rather, sound is primarily understood as evoking the viewer’s “aural” attention to accompany the visual attention triggered by visual stimuli.

Within the field of visual communication it is only the social semiotic approach that understands the verbal and the visual as one indivisible unit of analysis. The social semiotic approach to visual analysis developed out of Systemic Functional Linguistics (Halliday 1977, 1994). It was first formulated in Kress and van Leeuwen (1990, 1992) and was proposed as a “grammar of visual design” in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996). Fundamentally, Kress and van Leeuwen see grammatical forms as resources for encoding interpretations of experience and forms of (social) interaction in language, and they find that the major (spatial) compositional structures, which have become established as conventions of expression in the course of the history of visual semiotics, serve the same goals. In other words, the arrangement of elements in an image is seen as just as systematic, principled and rule based as the ordering of linguistic elements in a written sentence or spoken utterance. The internal organization of an image, accordingly, functions to communicate a certain interpretation of the experience of reality and a certain kind of interaction between the elements in the image and between the viewer and (the elements in) the image.

This view of a similarity between language and image is not an accidental match. In fact, this conception of a “grammar of visual representation” builds on an analogy between the three communicative functions (“metafunctions”) which Halliday (1978) posits for verbal communication and the communicative purposes Kress and van Leeuwen posit for visual communication.[1] Roughly glossed, they serve to express representational, interactional, and information-organizational meanings in texts. While in language the metafunctions are expressed by specific lexical and grammatical means, they are realized by specific sets of representational resources in visual communication. It is assumed that, since both language and visual communication express meanings belonging to and structured by the culture of their origin, there is a certain degree of convergence between the two semiotic systems. This does not mean that visual structures are identical or similar to linguistic structures. But the assumption of an identical functional diversification across communicative systems allows the correlation of the meanings expressed by linguistic structures and the meanings realized by visual structures with a view to the overarching communicative functions they serve (see Baumgarten 2005). Surprisingly, however, analyses of multimodal texts within the systemic functional paradigm have usually focused on the visual data and have not considered the accompanying verbal information and the interaction between them in comparable depth.

To conclude, approaches to visual analysis and film studies do acknowledge the meaning potential of verbal information in visual communication, albeit to distinctly different degrees. Neither visual analysis nor film studies offer a model of the interaction between visual and verbal elements in the process of meaning construction in film or an analytical apparatus for the integrated analysis of visual communication and its linguistic component. Translation studies, on the other hand, do not seem to have addressed the multimodality of film texts beyond the question of the different types of synchrony between the visually present participant(s) and the spoken discourse. On the whole, the question of how, i.e., by what kind of linguistic means, meaning is expressed in multimodal texts and how it interacts with the visual information appears to be rarely asked and even less often addressed. In the following section, I will propose a simple model of the interaction between visual and verbal information in film texts by drawing on the linguistic concepts of cohesion and exophoric reference.

4. Visual-verbal cohesion

This section is divided into two parts: The first part gives a general layout of the idea of verbal-visual cohesion. In the second part, a model of cohesion across semiotic modes (“visual-verbal cohesion”) will be introduced. The model served as the guiding concept in the analysis of the combination of visual and verbal information in the corpus of film texts and film translations. The results of the diachronic corpus analysis will be presented in Section 5.

4.1. The combination of visual and verbal information in film

4.1.1. Integration

A film text, as it is understood in the present context, consists of two constituents: a layer of visual information and a layer of verbal information. Both the visual and the verbal layers are of equal importance because it is only their combination which results in the fabrication of a more or less convincing illusion of reality onscreen for the extramedial audience. That is to say, the visual information does not merely serve as a backdrop in front of which the onscreen characters interact. Rather, their communicative interaction is firmly situated in the depicted extralinguistic reality onscreen. It resembles very closely (in fact, mimics) the nature of communicative interaction in naturally occurring communicative situations, which is, among other things, characterized by the interaction of the participants with the physical surroundings of the communicative encounter.

In film, linguistic reference to the extralinguistic situation surrounding the participants in the communicative encounter serves at least two broad functions: first, it functions to support the construction of a convincing imitation of real-life communicative encounters. The participants make linguistic reference to the extralinguistic reality in order to make an object in the extralinguistic context the subject matter of the discourse. The second function of linguistic reference to the extralinguistic situation is to single out elements of the physical surroundings for the audience’s attention.[2]

This functional combination of verbal and visual information (i.e., the multimodality of meaning construction) is the defining characteristic of film texts. Visual and verbal meanings can be understood as being situated on two parallel levels of information, which are integrated in specific ways to form one text. This “oneness” is no coincidence, but the result of a carefully manufactured process of integration: in theory, the verbal and visual meanings in film could be seen as autonomous – each kind, as it were, telling their own part of the story in the service of a superordinate quaestio, which defines the overall story of the film. As much as this radically separatist view must appear unconvincing, it nevertheless helps to clarify that visual and verbal information do not simply co-exist in a film text but that they are internally related to each other in specific ways, which only fuse them together as one. This integration of visual and verbal meaning is realized by linguistic means.

The relation between visual and verbal information in film, then, can be described in the following manner: the visual and the verbal are two parallel strands of information unfolding in time. Occasionally, initiated by linguistic means, the two are explicitly connected. Figure 1 and example (1) below illustrate this connection. The solid black vertical lines represent linguistic items and structures which explicitly refer to visual information. Visual information thus referred to is represented as a downward indenture in the dotted gray line. In other words, whenever a character refers to an object present in the extralinguistic situational context of the communicative encounter, he/she creates an explicit link between the ongoing talk and the physical environment, thereby pulling together for a moment the two layers of visual and verbal information and linking visual and verbal meanings.

This kind of relationship between visual and verbal information in film can be accounted for as “visual-verbal cohesion,” i.e., one linguistic/visual element is necessary for the interpretation of another from the other mode.[3]

Figure 1

The integration of visual and verbal information in a film text

Visual-verbal cohesion plays a central role in the communication between the film and the extramedial audience. Whatever the onscreen participants make reference to is simultaneously pointed out as the focus of attention for the audience. As will be shown in Sections 5 and 6 below, English and German appear to have different preferences for making reference to visual information and to integrate verbal and visual meanings in film texts. To be able to account for language specific preferences, a fine-grained modeling of the interaction between verbal and visual information is necessary. The present article, however, cannot venture very far in this direction. A model which is sufficient for the present purposes is presented in the following section.

4.1.2. A model of visual-verbal cohesion

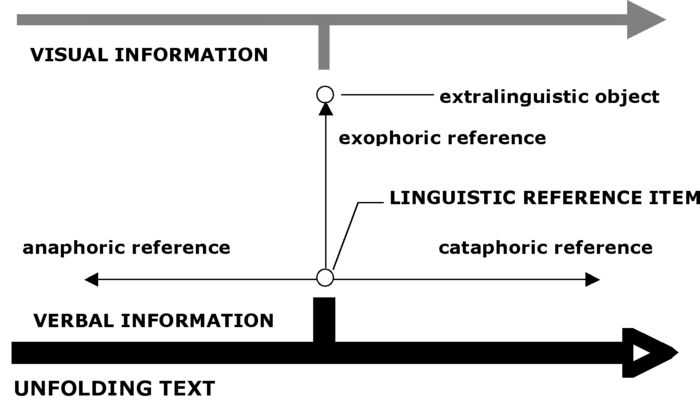

I propose a simple three-dimensional model[4] of textual cohesion in film texts (Figure 2): anaphoric and cataphoric reference integrate sequentially related verbal parts of the text. Exophoric reference integrates spatially related and temporally coinciding verbal and visual information.

In the theoretical and analytical framing of visual-verbal cohesion, another factor has to be taken into account. Visual-verbal cohesion is not dependent on the presence of an explicit exophoric reference item. The mere co-presence of visual information and linguistic structures has an “adding” effect – or what Lang has called in another context “Parallelisierungseffekt” (Lang 1977: 47) – on their meanings. That is, the visual and the verbal information are always interpreted as belonging together in a certain, if implicit, way. The visual information is interpreted as contributing to the meaning of the utterances and vice versa because viewers will always involuntarily try to establish a meaningful relationship between the two layers of information they are presented with. This is not to say that all co-occurrences of visual and verbal information are cohesive, but rather that the link between the verbal and the visual information need not be linguistically explicit and still can be cohesive.

Figure 2

A model of visual-verbal cohesion in film texts

It follows that the repertoire of linguistic resources for signaling that the information required for interpreting verbal meaning is to be recovered from the co-occurring visual information is broader than that of verbal cohesion. Beyond structural phenomena such as ellipsis, the classes of pronouns and determiners, locative and time adverbials, and proper names, the resources of visual-verbal cohesion include all linguistic expressions which realize a semantic connection with the visual information, and which single out for the hearer’s attention both the linguistic expression and the visual information. In example (2) below, the utterance I ONLY PAY THEM LIP SERVICE does not refer to the activity the characters are currently engaged in. The verbal and the visual information are both fully explicit and carry different meanings. Still, by virtue of their co-presence, the verbal and the visual meanings are semantically connected and add up – in this instance to a pun in the service of the dramatic effect of irony.

So while exophoric items proper – such as pronouns and demonstratives (cf. Martin 1992) – embody an instruction to the hearer to retrieve the information necessary for interpreting the linguistic structure from elsewhere, the linguistic means for expressing visual-verbal cohesion additionally include those which merely connect fully explicit lexical meaning to fully explicit visual meaning.

In the next section, the results of the diachronic investigation of visual-verbal cohesion in the English film texts and their German translations, following the concept of cohesive exophoric reference just described, are presented.

5. Results of the corpus analysis

The corpus of English film texts and their German-language versions was compiled from the films of the British-American motion picture series 007 – James Bond. The corpus consists of 219 transcripts from 19 films, comprising – with one exception – all productions from the 1960s through to the 1990s.

The transcriptions were made from audio recordings of the original English film soundtracks and their corresponding official German-dubbed versions. The corpus comprises approximately 16 hours of transcribed spoken discourse from a principled selection of film scenes. These scenes feature the main character – British secret agent “James Bond” – in conversational encounters with stock characters (his superior “M,” head of the British Secret Service, M’s secretary “Miss Moneypenny,” the armorer “Q”), realizations of recurring character types (the “good girl(s),” the “bad girl,” the local liaison officer, the prime criminal), and a few other characters which fall into neither of these categories. The objective behind this selection was to ensure, as far as possible, the diachronic comparability of the discourses.

The database for the diachronic contrastive analysis of visual-verbal cohesion consists of two data sets:[5]

Table 1

Database for the diachronic contrastive analyses of visual-verbal cohesion

The linguistic phenomena referring to extralinguistic objects tracked in the transcripts are the following: personal pronouns,[6] demonstrative and possessive pronouns, demonstrative and possessive determiners, definite and indefinite articles, situational reference through so-called equative clauses (e.g., “this is,” “das ist”) – or, German “Objektdeixis” (Zifonun et al. 1997: 323/324) – locative and time adverbials (including secondary deixis, expressing spatial relations (e.g., “over there”), and prepositional phrases), proper names, lexical expressions (including expressions initiated by mental and material processes (e.g., “as you see”)).[7]

The development of the use of linguistic elements realizing visual-verbal cohesion is displayed in Table 2 below:

Table 2

Occurrences of linguistic phenomena expressing visual-verbal cohesion: normalized frequencies (1000)[8]

Even though the differences between the frequencies for the English and German texts are not statistically significant, the figures nevertheless represent a tendency and can serve to describe the relation between English film texts and their German translations and its development across the decades. The values in Table 2 suggest that the use of linguistic phenomena which realize visual-verbal cohesion in the English and German texts undergo the same development of decline. At the same time, they seem to be getting closer in their frequency of use. Between the 1960s and the 1990s the values for the English texts fall by 20.8% and the values for the German translations fall by 29.7%. Compared to their English source texts the German translations of the 1960s show about 35% more occurrences of linguistic phenomena realizing visual-verbal cohesion. In the 1990s, this ratio has dropped to a value of approximately 20%.

The linguistic realization of visual-verbal cohesion can also be related to the mean length of the discourses (Table 3):

Table 3

Occurrences of linguistic phenomena realizing visual-verbal cohesion in relation to the mean length of transcripts

In an English discourse of average length there are about six occurrences of linguistic elements which form a link with visual information. Over time, their number decreases. From this perspective as well, the German translations in both time frames are characterized by higher figures. Like the English source texts, the translations show a decreasing development.

The higher figures for the German translations indicate that more linguistic material, i.e., more single, individually cohesive elements, is used to connect the extralinguistic context of the communicative encounter to the subject matter of the discourse. Closer analysis revealed that the higher values for the translations are the result of giving two or even three or four times the number of cohesive elements than the source text. In example (3), the male character on the left violently rips the film out of the woman‘s photo camera. He ends this action with a remark addressed to the man on the right.

In the English source text, the logical relation between the verbal and the visual information is implicit. In contrast, the translation features two explicit deictic elements: SO and JETZT (“now”). SO is a so-called “Aspektdeixis” (Ehlich 1987 and cf. Zifonun et al. 1997) which points to a particular characteristic of an object or event – in this example, finishing the action of removing the film from the camera. The time adverb JETZT focuses the endpoint of the action and explicitly introduces the ensuing utterance as its immediate consequence. The English utterance does not feature explicit deictic elements pointing to specific parts of the depicted action. A referentially implicit connection between the verbal and the visual information is used, which results in a vague relation between the visual and the verbal meanings.

The diachronic contrastive analysis suggests that this multiplying of reference items and the greater referential explicitness in the German translations does not change over time, even though the total number of verbal reference to visual information decreases. In the remainder of this section, what appear to be the general trends of the linguistic expression of reference to visual information between the English source texts and their German translation are presented.

In approximately half of the instances of linguistic reference to the visual context in the English source texts, a lexically and grammatically comparable structure is used in the German translations. For the other half of the instances of linguistic reference to the visual context, three major strategies of lexicalization are discernible: 1. Additional deictic elements are introduced into the discourse. They tighten the cohesive relation between the verbal and the visual information. 2. Markers of interpersonal involvement – such as interjections, exclamations, modal particles, and modal words – are added. They express the speaker’s attitude towards the visual information referred to. 3. Entirely different linguistic forms for expressing reference to visual information are used. I will illustrate these three strategies in turn.

Additional linguistic elements referring to visual information

The translational utterances often feature additional temporal and locative adverbs which provide an additional focus on the here and now of the communicative situation. In (4), the additional locative deictic expression HIER (“here”) explicates the direction in which speaker and hearer (and the extramedial viewer) turn their attention. The use of HIER also coincides with the pointing gesture by the speaker, which doubles the reference to the visual information.

4. Male character [right]: Oh. I’d like that negative enlarged. Right?

Male character [right]: Achja, ich ähm hätte gern dieses Negativ hier vergrößert.

1967 Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

1967 Danjaq, LLC and United Artists CorporationNext to the addition of single deictic elements, more complex structures such as equative clauses (e.g., “das ist,” “dies ist,” “hier ist”) are frequently inserted in the translations. In equative clauses the deictic element (e.g., “das,” “dies,” “hier”) serves to focus the visual information, while the ensuing predication with a form of SEIN (“be”) serves to specify an attribute of the object denoted by the deictic element. Equative clauses realize what is called “ostensive definition” by Ehlich (1994a). More than being a means of focusing visual information, he sees the deictic element as orienting the hearer (in film, both the diegetic and extradiegetic) towards the object denoted by the following noun. See example (5) below:

5. Male character [left]: It’s the insurance damage waiver for your beautiful new car.

Male character [left]: Das hier ist eine spezielle Zusatzversicherung für Ihren wunderschönen neuen Wagen.

1997, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

1997, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists CorporationVague locative references are often rendered more explicit in the German translations through the addition of secondary deictic elements, which express precise spatial relations. DA VORNE, for example, is a combination of a locative adverb DA (“there”) and a secondary deictic element VORNE (“ahead”) which expresses the direction of the orientation towards DA. DA VORNE provides a comparatively more precise locative description of the object the speaker has in view than the English source text structure THAT’S IT.

Another type of addition is the use of articles in order to render nominal reference to visual information more precise, where the source texts use bare nouns. The articles provide a closer specification of the objects referred to, explicitly marking them as “unknown” information (knowledge specific to the speaker) or “known” information (knowledge presupposed to be shared by the speaker and the hearer).

The use of conjunctions in addition to lexical expressions, finally, serves both verbal and verbal-visual cohesion. Often accompanied by gestures or other body movements, part of the semantic meaning of the connective is, as it were, explicitly connected with the physical interaction between the participants. Next to the creation of cohesion between utterances by expressing additional or explicating implicated logical relations, the function of the connectives in these contexts can be seen as facilitating the especially smooth linkage of verbal and visual information. See, for example, the use of utterance-initial ABER (“but”) in (6) and note the movements of the speaker‘s hands.

6

A. Woman: I’ve never been to Severnaya.

Woman: Ich war nie in Severnaja.

A1. Male character: Your watch has.

Male character: Aber Ihre Uhr schon.

Additional markers of interpersonal involvement

Very frequently interjections, discourse markers, modality markers, and to a slightly lesser extent exclamations are added to the translations. They increase the informational density (i.e., the amount of non-redundant linguistic material) of the translation texts because they add meanings, which are not encoded in the source texts. Interjections and discourse markers are used to immediately affect the hearer and his/her course of actions, without using propositional structures. They also express the speaker’s emotional attitude towards the subject matter of the discourse and the communicative task he/she is involved in (cf. Ehlich 1986). When they are used to refer to visual information, they serve to orient the hearer’s attention towards a particular object in the physical environment of the communicative encounter. Exclamations, which, in contrast to interjections, have clearly delineated semantic meaning, likewise express the speaker’s emotions, and they also direct the hearer’s attention towards particular visual referents. Interjections and exclamations usually function as initiators for a subsequent utterance. The ensuing utterance will be interpreted on the basis of the meaning expressed by the initial interjection or exclamation (Biber et al. 1999). In example (7), the interjection HMM MMH simultaneously singles out the gun as the joint focus of the speaker and hearer and expresses the speaker’s appreciation (Zifonun et al. 1997) of the gun.

7. Male character [right]: That gun. . Looks more fitting for a woman.

Male character [right]: Hmm mmh, ein schönes Gewehr. Passt eigentlich mehr zu einer Frau.

1965, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

1965, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists CorporationAlternative structures

In at least one-third of all cases of the linguistic expression of visual-verbal cohesion, the German translations use alternative linguistic structures to refer to visual information. For example, indefinite articles in the English source texts are often replaced by definite ones in the German translations. Definite articles mark the information they refer to as “known.” With respect to visual information, the definite article consequently points to precisely one of the visible objects, singling it out as the focus of attention. This results in a stronger cohesion between the verbally expressed meaning and the visual information. This increase in denotational explicitness is also achieved by the substitution of nouns for pronominal reference. The lexical expressions make a greater amount of semantic meaning explicit than the pro-forms do. Compare the use of the pro-form ONE to KUGEL (“bullet”) in the German translation in (8). While the interpretation of ONE solely relies on the hearer’s making the connection between the pro-form ONE, the gun, and the implicated concept of firing bullets, to which the pro-form refers, the German translation makes this link between the gun and the bullet (‘Kugel’) explicit.

8. Male character [left]: The first one won’t kill you.

Male character [left]: Die erste Kugel wird Sie nicht töten.

1963, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

1963, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists CorporationThe communicative effect of these changes influences the textual as well as the interpersonal meanings expressed in the text. Textually, the translations display a greater redundancy between the verbally and the visually given meanings. On the interpersonal level, the utterances are more „direct“ (House 1996), i.e., communicatively straightforward and unequivocal, than those of the English source texts. For example in (9), in which the male character zips up the woman‘s dress, the English utterance NO WONDER YOU CAN GET DRESSED SO QUICKLY, accompanied by his distinct glance down her back, implicates that the woman is naked under her dress. In the translation, this implication is made explicit and directly addressed to the woman in the question TRÄGST DU ZUR KETTE NIE MEHR ALS EIN KLEID? (“do you always only wear a necklace and a dress?”). Both, visual-verbal redundancy and the interpersonal orientation of the speaker are increased in the translation.

The effects of the differing ways of expressing visual-verbal cohesion in English and German on the German translations can be summarized in the following way. Overall, compared to their English source texts, the German translations display enhanced visual-verbal cohesion. Verbal reference to visual information is spatio-temporally more precise. The translations not only characterize the location of the visual referent more closely but also provide, in some cases, a more detailed description of their (external) features. As a consequence of the increased amount of linguistic material used to focus the visual referent, the referential explicitness and also the visual-verbal redundancy of the translations are increased. The instances where the verbal and the visual interlock are also used to add the linguistic expression of the speaker’s interpersonal involvement and to express additional or explicate implicated logical relations between verbal and visual information. In comparison to their English source texts, these additions result in a greater informational density in the translations. To summarize, compared to their English source texts, the German translations are characterized by greater referential and denotative explicitness, as well as by emphasized logical relations, and the linguistic expression of the speaker’s (affective) attitudes towards the visual information he/she perceives.

9. JB: Mmh. . . No wonder you can get dressed so quickly.

JB: Mh. . . Trägst Du zur Kette nie mehr als nur ein Kleid?

1965, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

1965, Danjaq, LLC and United Artists CorporationThe corpus data suggest that this picture did not change significantly over the course of the twenty-eight years (1967–1995) which represent the time gap between the two time frames investigated. The corpus counts indicate a reduced use of linguistic reference to visual information for both English and German, but the ways in which reference is expressed appear to stay the same.

Of course, the results are genre-specific. There is certainly the possibility that the analysis of other types of films would render a different picture. Not the least depending on the genre, the amount of spoken discourse in film may vary from sparse and confined to selected scenes in action genres to genres in which the discourse has precedence over visual information such as, for instance, in domestic drama.

To conclude, the greater cohesion in the German translations between visual and verbal information can take the form of increased redundancy between visual and verbal meanings, i.e., the same information is given through visual and linguistic means, and of increased informational density, i.e., more linguistic material with individual meanings is used to refer to the visual information. In each case, the textual space is more tightly packed with information in the German translations than in the English source texts.

Between the 1960s and the 1990s the overall length of the translations decreased. In the 1990s they are, on average, only about 2% longer than their source texts (falling from about 4%). Nevertheless, the analysis shows that the translations always find the space to include one or more additional linguistic items, which strengthen cohesion, increase explicitness, or heighten the expression of the speaker’s interpersonal involvement. In the next section, I will suggest that these effects may belong to the major communicative goals of the German translations.

6. Discussion

For present purposes, only those parts of the film discourses were analyzed in which verbal and visual information interact directly. The findings, however, are corroborated by the results of the analyses of the full discourses. The translation relation between the English source texts and their German translations is characterized by a general pattern, which can be summarized as follows: First, without any apparent regularity in terms of the lexical and grammatical structure of the source text utterance and its communicative function, the linguistic realization of the speakers’ attitudes varies in the translations. The expression of speaker attitudes is often enhanced by additional modal elements or even inserted into previously non-modalized utterances. Second, in comparison to the English source texts, the translations are rendered more explicitly cohesive. The sequencing of information is more closely connected to cause and effect relations and chronological progression. Third, vague, indefinite, and ambiguous grammatical and lexical units are substituted by referentially explicit and denotatively precise structures. The changes result in an increased informational density in the German translations. In other words, the German translations provide “more” information. This information is always an “autonomous” addition to the utterance, that is, it is neither partly nor wholly identical with information already provided by other linguistic items. Thus, the additional linguistic items in the translations enrich the informational content of the utterances. The increased informational density is manifest in a closely knit web of logical connections between propositions and in a heightened degree of affective expressiveness. Hence, a translated film text presents more information through more linguistic elements but in the context of the same amount of visual information.

On the whole, the evidence suggests that the German translations “want” to be strongly cohesive, explicit, and interpersonally expressive. The parts of the discourses which are constituted by the combination of verbal and visual information display the same characteristics as those parts of the discourses which are not tied to co-occurring visual information. This is a surprising finding because, when there is co-occurring visual information which must be referred to for the reason of its being referred to in the source text, the time span within which the reference and the additional linguistic items have to be accommodated is obviously limited. Therefore, when the translations follow the same communicative conventions even in textual contexts in which textual space is limited by external constraints, one might assume that these conventions are comparatively central to the communicative preferences and textual norms of the language.[9]

This finding partly contradicts the established pattern of communicative conventions in a variety of spoken and written genres (e.g., House 1996). Compared to comparable English texts and spoken discourse, German texts and discourses are usually characterized by a greater degree referential explicitness and denotative precision and a pronounced content-orientation. Conversely, the overt expression of the speaker’s affective attitude and emotional involvement in the communicative interaction is generally assumed to be less pronounced. The analysis of the film translations supports the assumption of a preference for referential explicitness and denotative precision in German, but the assumption of a lesser degree of interpersonal involvement cannot be confirmed.

The explicitation of logical relations between visual and verbal information establishes unambiguous meaning relations, which encode a more fixed narrative frame. Consequently, the viewer’s interpretational possibilities are constrained. There is less need for the viewer’s active co-constructing of the story by individually explicating implicated, vague, and ambiguous meanings. The narrative of the translated film can also be affected by the additional expression of the speaker’s attitude towards co-occurring visual elements in the translational discourses. In the present corpus, the supplementary interpersonal meanings usually result in the foregrounding of an incessant, one-dimensional, highly sexualized type of affective involvement in the communicative interactions, which is not present to an equivalent degree in the source texts (see Baumgarten 2005).

To conclude, regarding language use in film and its translation, it is important to be aware of the fact that the visual and the verbal sign systems interact. Choosing linguistic and visual elements, crucially, also means choosing which verbal element to combine with which visual element. There is no inherent, compulsory relation between verbal and visual information. The combination of visual and verbal elements is a matter of choice. Consequently, the functions that combinations of visual and verbal information serve, and the meanings that arise from them, have to be considered as intentional and indicative of particular communicative conventions and a particular communicative aim.

In the process of film translation, the component parts of the film text are separated, the linguistic one is exchanged, and a new combination of verbal and visual information is established. Since the new verbal information is – like the source text’s discourse – a product of linguistic choice, according to the requirements of the communicative situation – both onscreen and between the film and the audience – as perceived by the target language text producers, it is possible that the overall function of the film text is varied, in the sense that different situational and cultural meanings are encoded.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

See Baumgarten (2005: Chapter 5) for a detailed description.

-

[2]

See Baumgarten (2005) for a detailed account of the two communicative levels involved in communication in films and their role for film translation.

-

[3]

For a full discussion of “visual-verbal” cohesion in relation to Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) concept of cohesion and Ehlich’s concept of “deictic spaces” see Baumgarten (2005).

-

[4]

See Baumgarten (2005) for the development and theoretical foundations of the model.

-

[5]

Films from the 1960s: Dr No (1962), German version: James Bond – 007 jagt Dr. No; From Russia with Love (1963), German version: Liebesgrüße aus Moskau; Goldfinger (1964) German version: Goldfinger; Thunderball (1965), German version: Feuerball; You Only Live Twice (1967), German version: Man lebt nur zweimal; On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), German version: Im Geheimdienst Ihrer Majestät. Films from the 1990s: Goldeneye (1995), German version: GoldenEye; Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), German version: Der Morgen stirbt nie; The World is Not Enough (1999), German version: Die Welt ist nicht genug.

-

[6]

Speaker-hearer deictic elements (‘I,’ ‘you,’ ‘we,’ ‘ich,’ ‘Du,’ ‘Sie,’ ‘Ihnen,’ ‘wir’) are excluded. They denote the participants in the communicative encounter in their speech roles; as such they do refer to visual information – the speaker and the hearer – but not primarily to the physical environment of the communicative situation.

-

[7]

In what follows, the linguistic means which express visual-verbal cohesion are considered together – as one group, or cluster, of features. The corpus is too small to yield sizeable results for the use of each individual linguistic item.

-

[8]

Since the datasets are not exactly of equal size, the raw frequencies had to be normalized in order to make them comparable. The norming formula is the following: (number of occurrences ÷ tokens) x 1000. The normalized frequencies have been subjected to a statistical test in order to see whether the distributions found and their development over time are significant or not. The statistical test applied is the chi square test, which is suitable for frequency data and small sample sizes. The observed differences between the frequency of use of linguistic items referring to visual information in English film texts and their German translations and the diachronic development are not statistically significant.

-

[9]

These results might also be interpreted in the light of (translational) explicitation. See Baumgarten, Meyer and Özçetin (forthcoming) for a discussion of translational explicitation and language-specific, conventionalized levels of explicitness in linguistic encoding.

References

- Baumgarten, N. (2005): The Secret Agent: Film dubbing and the influence of the English language on German communicative preferences. Towards a Model for the Analysis of Language Use in Visual Media, dissertation, Universität Hamburg, http://www.sub.uni-hamburg.de/opus/volltexte/2005/2527/.

- Baumgarten, N., Meyer, B. and D. Özçetin (forthcoming): Explicitness in Translation and Interpreting: A critical review and some empirical evidence (of an elusive concept).

- Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. and E. Finegan (1999): Grammar of Spoken and Written English, London, Longman.

- Bordwell, D. (1985): Narration in the Fiction Film, London/New York, Routledge.

- Bordwell, D. (1989): Making Meaning. Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema, Cambridge/London, Harvard University Press.

- Bordwell, D. and K. Thompson (1997)5: Film Art. An Introduction, New York/London, McGraw-Hill.

- Borstnar, N., Pabst, E. and H.-J. Wulff (2002): Einführung in die Film- und Fernsehwissenschaft, Konstanz, UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Branigan, E. (1984): Point of View in the Cinema. A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film, Berlin/New York, Amsterdam, Mouton Publishers.

- Böttger, C. and K. Bührig (2004): “Snakes, Success and other Ethical Standards: A translation analysis of a corporate image,” in Gouveia, C. A. M. and E. Ribeiro Pedro (eds.), Discourse, Communication and the Enterprise, Lissabon, Ulices, University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies, pp. 233-243.

- Bührig, K. and J. House (2004): “Connectivity in translation: transitions from orality to literacy,” in House, J. and J. Rehbein (eds.), Multilingual Communication, Amsterdam, Benjamins, pp. 87-114.

- Chaume Varela, F. (2003): “Models of Research in Audiovisual Translation,” Babel 48-1, pp. 1-13.

- Dries, J. (1995): Dubbing and Subtitling. Guidelines for Production and Distribution, European Institute for the Media.

- Ehlich, K. (1982): “Deiktische und phorische Prozeduren beim literarischen Erzählen,” in Lämmert, E. (Hrsg.), Erzählforschung: Ein Symposium, Stuttgart, Metzler, pp. 98-111.

- Ehlich, K. (1987): “So – Überlegungen zum Verhältnis sprachlicher Formen und sprachlichen Handelns, allgemein und am einem widerspenstigen Beispiel,” in Rosengren, I. (Hg.) Sprache und Pragmatik: Lunder Symposium, Stockholm, Alnqvist and Wiksell International, pp. 279-299.

- Ehlich, K. (1996): “Funktional-pragmatische Kommunikationsanalyse: Ziele und Verfahren,” in Hoffmann, L. (Hg.), Sprachwissenschaft. Ein Reader, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, pp. 183-201.

- Ehlich, K. (2004): “Pragmatik und Grammatik: Grammatik als Pragmatik,” lecture given at the Research Center on Multilingualism, University of Hamburg, 29.09.2004.

- Ehlich, K.and J. Rehbein (1986): Muster und Institutionen. Untersuchungen zur schulischen Kommunikation, Tübingen, Gunter Narr.

- Halliday, M.A.K. and R. Hasan (1976): Cohesion in English, London/New York, Longman.

- Halliday, M.A.K. (1978): Language as Social Semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning, London, Arnold.

- Halliday, M.A.K. (1994/1985): An Introduction to Functional Grammar, London, Arnold.

- House, J. (1996): “Contrastive Discourse Analysis and Misunderstanding: The Case of German and English,” in Hellinger, M. and U. Ammon (eds.), Contrastive Sociolinguistics, Berlin, Mouton, pp. 345-361.

- Kozloff, S. (2000): Overhearing Film Dialogue, Berkeley/London, University of California Press.

- Kress, G. and T. van Leeuwen (1990): Reading Images, Geelong, Deakin University Press.

- Kress, G. and T. van Leeuwen (1992): “Structures of visual representation,” Journal of Literary Semantics 11-2, pp. 91-117.

- Kress, G. and T. van Leeuwen (1996): Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, London/New York, Routledge.

- Lang, E. (1977): Semantik der koordinativen Verknüpfung, Berlin, Akademie Verlag.

- Martin, J.R. (1992): English Text: System and Structure, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

- Mounin, G. (1967): Die Übersetzung: Geschichte, Theorie, Anwendung, München, Nymphenburger.

- Nida, E. A. (1969): The Theory and Practice of Translation, Leiden, Brill.

- van Leeuwen, T. and C. Jewitt (eds.) (2001): Handbook of Visual Analysis, London, Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications.

- Zifonun, G., Hoffmann, L. and B. Strecker (1997): Grammatik der deutschen Sprache, Berlin/New York, Walter de Gruyter.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

The integration of visual and verbal information in a film text

Figure 2

A model of visual-verbal cohesion in film texts

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Database for the diachronic contrastive analyses of visual-verbal cohesion

Table 2

Occurrences of linguistic phenomena expressing visual-verbal cohesion: normalized frequencies (1000)[8]

Table 3

Occurrences of linguistic phenomena realizing visual-verbal cohesion in relation to the mean length of transcripts