Résumés

Abstract

This paper consists of an analysis of the expressive secondary interjections found in the film Four Weddings and a Funeral and their equivalents in the Spanish and Catalan dubbed versions. The contrastive analysis of the interjections in the original English version compared with the Spanish and the Catalan dubbed versions shows that the strategies followed by the translators are different: literal translation is far more frequent in Spanish than in Catalan. Literal translation often implies an error that is pragmatic in nature since it derives from the misunderstanding of the pragmatic meaning that the interjection conveys.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- interjections,

- audiovisual translation,

- translation strategies,

- pragmatic errors,

- dubbing

Résumé

Dans cet article nous étudions les interjections secondaires expressives qui sont utilisées dans le film Four Weddings and a Funeral et leurs équivalents dans les versions espagnole et catalane. L’analyse contrastive des interjections dans la version originale anglaise et dans les versions doublées catalane et espagnole montre que les traducteurs ont employé des stratégies différentes : la traduction littérale est beaucoup plus fréquente dans la version espagnole que dans la version catalane. La traduction littérale comporte souvent une erreur pragmatique, et c’est là une conséquence d’une interprétation incorrecte du signifié pragmatique que l’interjection transmet.

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Interjections have been generally defined as a peculiar word class, peripheral to language and similar to nonlinguistic items such as gestures and vocal paralinguistic devices (see Ameka 1992; Cuenca 2000, 2002a; Goffman 1981). In addition to the theoretical and descriptive challenges that interjections imply, they can be associated with important problems for translation, since many languages share identical or similar forms or word-formation processes, but the conditions of use of the interjections are not the same.

In this paper I present an analysis of the expressive secondary interjections found in the film Four Weddings and a Funeral and their equivalents in the Spanish and Catalan dubbed versions[1]. The contrastive analysis of the expressive secondary interjections in the original version in English compared with the Spanish and the Catalan dubbed versions shows that the strategies followed by the translators are different: non-identification and literal translation is far more frequent in the Spanish version than in the Catalan version[2]. This implies a less natural outcome in Spanish, which can be related to the translator’s failure in recognizing the grammaticalized nature of this type of interjections.

Interjections are idiomatic units or routines syntactically equivalent to a sentence:

Interjections are idiomatic because “they are frozen patterns of language which allow little or no variation in form and […] often carry meanings which cannot be deduced from their individual components” (Baker 1992: 63).

Interjections are routines since they can be defined as “highly conventionalized prepatterned expressions whose occurrence is tied to more or less standardized communication situations” (Coulmas 1981: 2-3).

Interjections are a peculiar part of speech whose form corresponds to a word (i.e., hey, right, absolutely…) or a phrase (i.e., good Lord, for God’s sake, good point…), but syntactically they behave like sentences[3]: “They correspond to communicative units (utterances) which can be syntactically autonomous, and intonationally and semantically complete” (Cuenca 2000: 332).

Translating interjections is not a matter of word translation. It implies translating discourse meanings which are language-specific and culturally bound. The translator must interpret its semantic and pragmatic meaning and its context of use, and then look for a form (interjection or not) which can convey that meaning and produce an identical or similar effect on the audience of the dubbed version[4].

2. Secondary vs. primary interjections

Interjections are generally classified in two groups: primary and secondary. Primary interjections are simple vocal units, sometimes very close to nonverbal devices. In this case, the main problem for translation is the existence of identical or similar forms cross-linguistically whose conditions of use and frequency may not coincide.

The example in (1) shows the English interjection oh translated into Spanish as oh and as ai in Catalan. The written form oh exists, with different pronunciations, in the three languages, and it exhibits similar expressive meanings. However, its frequency and context of use are different in the three languages and, as a consequence, the literal translation of the form can result in a pragmatic error.

Secondary interjections are words or phrases which have undergone a semantic change by pragmaticization of meaning and syntactic reanalysis, in other words, they are grammaticalized elements[5].

Fiona’s exclamation heaven preserve us is not a reference to any religious concept, but an expression of surprise and fear that Gareth will follow Matt’s piece of advice.

It must be noticed that secondary interjections can combine with a primary interjection (3) or with an affirmation or a negation (4).

Since combinations exhibit a specific behavior in translation, they will be considered separately for the analysis.

3. Translating secondary interjections

Interjections are highly language-specific and, as a consequence, literal translation often leads to pragmatic errors. Many languages share identical or similar forms or word-formation processes, but the conditions of use of the interjections are not the same, as shown in example (1). As Baker (1992: 65) points out, there are two major problems for translating any idiomatic unit, namely, identifying a sequence as idiomatic and finding its equivalent[6]. Therefore, the basic problem that idiomatic and fixed expressions pose in translation has to do with two main areas: the ability to recognize and interpret an idiom correctly; and the difficulties involved in rendering the various aspects of meaning that an idiom or a fixed expression conveys into the target language[7].

Misinterpretation is likely to occur in two cases (Baker 1992: 65-ff):

when an idiomatic unit offers a reasonable literal interpretation.

when an idiom in the source language has a close counterpart in the target language, but has a totally or partially different meaning, context or frequency of use.

Most secondary interjections exhibit these two problems. Secondary interjections, as grammaticalized items that have undergone a process of semantic change, imply two meanings: an interjectional idiomatic interpretation – associated with a non-compositional semantic structure– and a phrasal non-idiomatic interpretation – associated with a literal, compositional semantic structure–. Their polysemy favors misinterpretation and, thus, errors in translation. Example (5) illustrates this double nature.

When Fiona says the noun phrase Good Lord, she is not addressing to God nor insisting in his goodness; she is just expressing an emotion. The previous example shows a particular use of this secondary interjection since irony activates both meanings, the literal and the idiomatic. The idiomatic meaning conveys surprise, while the literal shows up from the fact that Fiona’s addressee is training to be a priest. The Spanish and Catalan counterparts (respectively, Santo cielo ‘Holy Heaven’ and Verge santa ‘Holy Virgin’) keep the connotation and maintain the polysemy of the original. In the three cases, a noun phrase is used as a sentence (i.e., an autonomous utterance) and has gone through a process of pragmatization of meaning, from a designative meaning corresponding to three different religious concepts to a common subjective pragmatic meaning (surprise).

According to Corpas (2000, 2001), the equivalence between idiomatic units can be full, partial or nonexistent. Full and nonexistent equivalence are rather infrequent[8]. The most frequent case is that of partial equivalence, which can be associated with differences in the morphosyntactic, the semantic or the pragmatic level (Corpas 2000: § 3). To keep the equivalence, secondary interjections must be translated focusing on the interjective meaning and not on the literal meaning.

In (6), the interjection Christ! has been translated into a combination of a primary and a secondary interjection in Spanish (¡Oh, cielos!, literally: ‘Oh, heavens!’) and into a secondary interjection in Catalan (Ostres, literally: ‘Oisters’, which is a euphemistic form substituting òstia, a blaspheme referring to the consecrated wafer). These solutions do not correspond literally to the meaning of the English interjection. Still, the expressive meaning is equivalent: they express surprise and disappointment about the fact that Charles has not slept with many women as compared to Carrie’s curriculum.

4. Translating expressive interjections

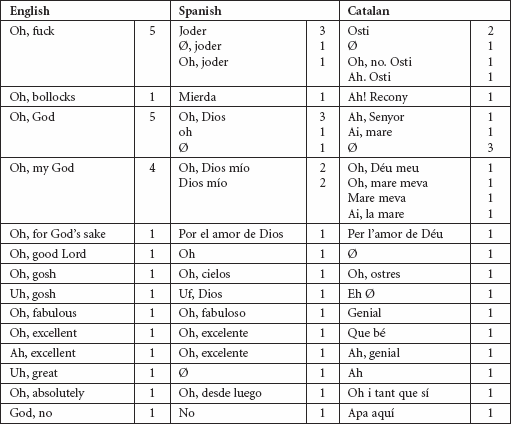

Expressive interjections refer to the speaker’s feelings, such as joy, surprise, admiration, anger, sadness and so on. The translation equivalents of the English secondary expressive interjections (66 cases) into Spanish and Catalan are shown in table 1[9].

Table 1

English expressive secondary interjections and their translations into Spanish and Catalan

Table 2 shows the correspondences between the English combinations including secondary interjections (25 cases) and the Spanish and Catalan translated forms.[10]

Table 2

English expressive secondary interjections combined and their translations into Spanish and Catalan

A quick glance at the tables highlights that the Spanish translation is more tied to the original than the Catalan translation, which is more dynamic and natural. The translation of fuck, the most frequent expressive interjection in the film, illustrates this fact. Fuck and its variants are almost systematically translated into joder (lit: ‘fuck’) in Spanish. The Catalan version, osti (a reduced variant of òstia lit: ‘consecrated wafer’), sounds more natural in most of the contexts, though the force of the interjection would have been kept better using the disphemistic form òstia, which also exists in Spanish (hostia) and could have been a good alternative.

The frequency of joder as the translation of fuck in the Spanish version is quite unnatural, at least for standard Spanish.[12] Though joder is quite a frequent interjection, its use does not fully coincide with English fuck. Some interjections can be similar in English and the two Romance languages under study, but the latter have a wider variety of forms to express negative feelings, which can be dramatically reduced by translation (see Castro 1997 and Valero 2001: 636; and also Adam 1998 for French).[13]

Referring to cultural differences between English and Spanish that must guide the process of translation, Rabassa (1991: 43) indicates that blasphemes and insults include references to religion in Spanish, while there is a tendency to mention sexual or eschatological elements in English. However, my corpus does not fully confirm this observation: there is a tendency to maintain the semantic nature of the source. The Spanish dubbed version of the film exhibits less forms in both groups of interjections and religious expressions are more likely to turn into eschatological ones than the other way round. As for Catalan, the religious or eschatological-sexual character is maintained, except for fuck translated into the religious euphemistic form osti, and some religious forms which turn into eschatological expressions.[14]

5. Translation strategies

Baker (1992: § 3.2.4) distinguishes four different mechanisms for translating idioms:

Using an idiom of similar meaning and form.

Using an idiom of similar meaning but dissimilar form.

Translation by paraphrase.

Translation by omission.

Adapting Baker’s proposal, I have differentiated six strategies for translating interjections, either primary or secondary (see Cuenca 2002b): literal translation (strategy a); translation by using an interjection with dissimilar form but the same meaning (strategy b); translation by using a non-interjective structure with similar meaning (strategy c); translation by using an interjection with a different meaning (strategy d); omission (strategy e); addition of elements (strategy f). These strategies are exemplified with secondary interjections as follows:

Strategy a: literal translation.

Strategy b: translation by using an interjection with dissimilar form but the same meaning.

Strategy c: translation by using a non-interjective structure with similar meaning.

Strategy d: translation by using an interjection with a different meaning.

Strategy e: omission.

Strategy f: addition of elements, generally a primary interjection.

The use of the six strategies by the Spanish and the Catalan translators is summarized in table 3.[15]

Table 3

Strategies used to translate secondary interjections

Five general conclusions can be deduced from table 3:

Literal translation (strategy a) is more frequently used in Spanish (42.8%) than in Catalan (13.1%), where it is even less frequent than omission (strategy e, 15.4%).

Conversely, non-literal translation (strategy b) is the most frequent strategy in Catalan since it involves almost 60% of the cases.

The rest of the strategies c, d, e and f (the use of a non-interjective structure, or another type of interjection, omission and addition of elements) are scarcely used as compared with strategy a and b, which together involve more than 70% of the cases in both languages.

Omission (strategy e) is very frequent with combinations, whereas strategies c, d and f do not apply to combinations (except for one case of strategy f plus a in Catalan).

Strategy e tends to occur with literal and non-literal translation in combinations.

6. Comparing the strategies of translation

If we consider the interjections in English and their translations (see tables 1 and 2), it is obvious that there is no one-to-one correspondence between the English interjections and the Spanish and Catalan forms. However, the analysis of the two dubbed versions of Four Weddings and a Funeral highlights striking differences in the strategies followed by the Spanish and the Catalan translators.

Although Spanish and Catalan are two similar Romance languages, it is not often the case that the translated interjections coincide. Different solutions and strategies are adopted in many cases. The range of possible equivalents to a single English interjection is directly associated with different translation strategies. Let us compare the strategies followed by the Spanish translator with the strategies followed by the Catalan translator in the same cases (table 4).

Table 4

Strategies used to translate English secondary interjections: Spanish compared with Catalan

The average percentage of coincidence in the strategies is 48.5% in the case of Spanish as compared with Catalan (44 cases out of 91). The level of coincidence is relatively low in the case of literal translation (strategy a, 23.1%), which corresponds in Catalan to non-literal translation (strategy b) in more than half of the cases (22 cases out of 39). Omission (strategy e) corresponds to non-literal translation (strategy b) or combinations of omission and strategy b in almost 50% of the cases (6 out of 13). Addition in Spanish (strategy f) corresponds to strategy b in Catalan.

The highest level of coincidence is that of strategy b (88%), which means that when the Spanish translator chooses non-literal translation it is often also the case in Catalan, but the reverse is not true. These results point to the fact that non-literal translation (strategy b) is far more frequent in Catalan than in Spanish and covers a range of other strategies used in the latter.

In the case of Catalan as compared with Spanish the average percentage of coincidence in the strategies is 50.5%, as shown in detail in table 5:

Table 5

Strategies used to translate English secondary interjections: Catalan compared with Spanish

The degree of coincidence is high for literal translation (strategy a, 83.3%) and also when using a non-interjective element with a similar meaning (strategy c, 75%). The correspondence is lower in the case of non-literal translation (strategy b, 41.5%), which corresponds to strategy a in Spanish almost in the same proportion (21 vs. 22 cases), and also in the case of omission (strategy e, 50%), though it must be pointed out that many of these examples are combinations of omission and literal translation.

In sum, the predominance of non-literal translation in Catalan is not parallel in Spanish, where literal translation is extensively used.

7. Pragmatic errors and dubbing

Literal translation can result in interference and eventually borrowing not only at the lexical level, which is easily identifiable, but at the pragmatic level, which is more implicit and difficult to avoid (see Chaume 2004; Gómez Capuz 1997, 1998, 2001). Gómez Capuz comments on the risk of pragmatic borrowing in dubbing, as dubbing is generally based on ordinary conversation and literal translation is frequent in this context:

Así pues, una de las variedades de la traducción más proclives a la presencia de préstamos pragmáticos es el doblaje de películas y seriales extranjeros, ya que operan sobre una variedad lingüística que imita la conversación cotidiana, caldo de cultivo de la interferencia pragmática en situaciones de bilingüismo.

Gómez Capuz 1998: 138

From this point of view, errors related to the translation of interjections are more pragmatic than linguistic (i.e., purely grammatical or lexical).[16] As Nord indicates, the main problem to solve pragmatic translation problems is identification, because pragmatic errors “cannot be detected by looking at the target text only (for instance, by a native-speaker reviser) unless they really produce incoherence in the text” (1997: 76). Consequently, this kind of error is among the most important in translation, “since receivers tend not to realize they are getting wrong information” (1997: 76).

Although some authors defend that interference is relatively low in translations into Spanish, the effect of this cultural and linguistic interference is increasing quantitatively and qualitatively, especially in the translation of soap operas and sitcoms.

[…] la interferencia pragmática y cultural en los doblajes peninsulares actuales de películas y seriales norteamericana no es muy acusada. Sin embargo, resulta algo más preocupante la reiteración de ciertos anglicismos pragmáticos: así, el empleo de ¿sí? (< yes?) como rutina discursiva al contestar una llamada (telefónica o de otro tipo), las fórmulas de cierre discursivo eso es todo (< that is all) y ¡olvídalo! (forget it!), la fórmula de tratamiento damas y caballeros (< ladies and gentlemen) y la fórmula de cortesía déjeme adivinarlo (< let me guess) parece haber calado hondo[…]. Y con ellos, la conversación cotidiana del español va perdiendo poco a poco su carácter genuino para convertirse en un pálido reflejo de los hábitos lingüísticos y los valores culturales del inglés norteamericano coloquial.

Gómez Capuz 2001: 813

In the same line of reasoning, Castro (1997) comments on the importance of non-literal translation in dubbing for TV:

Por rematar esta breve nota sobre la traducción de material para televisión, es conveniente decir que en esta modalidad el traductor es más tradittore que nunca. Su adaptación del texto para el espectador español debe ser tal que en ocasiones tendrá que cometer «alta traición» contra el producto original. Si no lo hacemos, corremos el riesgo de acabar expresándonos en español con estructuras estadounidenses, ya que gran parte de nuestra cultura es visual, televisiva y cinematográfica.

The use of sí [‘yes’] to express joy and of guau to express admiration in Spanish and Catalan, is becoming more and more frequent not only in translated texts but even in original ones, especially in Spanish advertising[17]. In my opinion, this tendency proves the real influence of literal translation of interjections on the target language.

In addition to the constraints imposed by dubbing as a complex modality of translation, there are other factors affecting pragmatic errors, such as the urgency of translations for the media –Castro (1997) states that is not infrequent that a translator has just one day to translate a whole film–, the lack of revision or the intervention of the adapter and the dubbing director, who can introduce new errors to the text.

Many of these pragmatic errors are related to the translation of interjections[18]. The fifth basic principle proposed by Nord (1997: 79) for translator training highlights the importance of considering errors which are not visible: “to use a verb in a wrong tense is less risky than to use it in the right tense at the wrong time.” Since interjections exhibit no tense or other morphological marks, and specifically secondary interjections are polysemous, the risk of mistranslation is even higher.

8. Concluding remarks

Secondary interjections imply specific difficulties in translation. The conflict between the source construction and the grammaticalized form (i.e., the interjection as such) sometimes leads to a non-identification of the interjection or to a mistranslation. The interjection can be interpreted as the word or the phrase it derives from, and it is then translated as if it were not an interjection but a lexical word or phrase.

The analysis of the expressive secondary interjections of Four Weddings and a Funeral shows differences in the strategies followed by the Spanish and the Catalan translators. Interjections have been predominantly translated literally in Spanish in contrast with Catalan, a version in which dynamic translation (strategy b) predominates. Assuming that interjections are idiomatic units, dynamic (non-literal) translation is expected to be the best option in a high proportion of cases. This hypothesis is consistent with other translation studies. Matamala (2004) identifies a number of expressive interjections in English sitcoms ((holy) crap, (bloody) hell, damn/darn, (oh) God, my/dear/good God, Gee) which are never translated literally in the Catalan corpus. Similarly, Valero (2001), after having analyzed the translation of interjections in a narrative corpus, concludes that literal translation is neither the most frequent nor adequate strategy.

As for secondary interjections, literal translation focuses on the source meaning of the grammaticalized construction and ignores the pragmaticization of meaning and the specificities of frequency and use associated with each form. As a consequence, the predominance of literal translation suggests the existence of a certain degree of pragmatic interference and error in translation. In other words, literal translation of expressive second interjections often results in the use of an interjection with a different connotation, context of use or frequency, or even in the use of a form that is not a proper interjection in the target language. On the contrary, translation by using an interjection with dissimilar form and literal translation but the same or similar meaning (strategy b) seems to be the best option for translating a secondary interjection in most cases.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Frederic Chaume, Anna Matamala and Maria Josep Marín for their help in the revision of this paper.

Notes

-

[1]

Cuenca (2002b) includes a preliminary analysis of the primary and secondary expressive interjections in the first part of the film (the first wedding). Cuenca (2004) deals with the translation of secondary expressive interjections from grammaticalization theory.

-

[2]

Dubbing is a complex process implying not only the translator, but also the adapter and the dubbing director, among others. Since I do not have any evidence to attribute the choices in translation to one agent or the other, I will generally talk of the translator as the responsible person for the final translation of the interjections, though it might be the case that the translated form proposed by him or her was not the final one.

-

[3]

Wilkins (1992) considers interjections as a unified class, despite their heterogeneous form.

Using a formal definition of interjection […], it is possible to identify cross-linguistically a form class of items which are simple lexemes that are conventionally used as utterances. […] it is clear that this is a unified category both morphologically and syntactically, given that interjections host no inflectional or derivational morphemes, and given that they do not enter into construction with any other lexemes. Furthermore, it has been shown that the class of items thus identified shares important semantic and pragmatic features. They are all context-bound items which require referential arguments to be provided by the immediate discourse context.

Wilkins, 1992: 153It is worth noticing that, from a morphosyntactic point of view, the secondary interjections found in the film result from grammaticalizing nouns and noun phrases, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, clauses and exceptionally other constituents (see Cuenca, 2004).

-

[4]

For other studies on the audiovisual translation of interjections and other discourse markers into Catalan, see González & Sol (2004), focused on the Catalan translations of well in Pulp Fiction, and Matamala (2004), a corpus based contrastive study of three subcorpus of sitcoms: Catalan original, English original and the dubbed Catalan versions of the English sitcoms. For Spanish, see Chaume (2004), who analyzes the translation of some discourse markers in three Spanish versions of Pulp Fiction, written, dubbed and subtitled.

-

[5]

See Hopper and Traugott (1993) and the synthesis included in Cuenca and Hilferty (1999).

-

[6]

Similarly, Corpas (2001) considers that the translation of idiomatic units implies three interrelated phases, namely identification of the idiomatic unit, interpretation and translation (at lexical level and at text level). Failure in identification or interpretation imply failure in translation. The three-phase process is also implicit in Baker’s proposal. In fact, interpretation cannot be dissociated from identification and translation. Thus, the possible sources of error are, in fact, two.

-

[7]

Identification is facilitated when the unit has an anomalous structure (for instance, lack of agreement) or its meaning is clearly non-compositional.

Generally speaking, the more difficult an expression is to understand and the less sense it makes in a given context, the more likely a translator will recognize it as an idiom. Because they do not make sense if interpreted literally, the highlighted expressions in the following text are easy to recognize as idioms […].

Baker 1992: 65 -

[8]

Corpas (2001: 782) defines full equivalence as denotative and connotative semantic identity, along with correspondence in distribution, frequency of use and pragmatic restrictions.

A un extremo de la escala se encuentra la equivalencia plena. Ésta se produce cuando a una UF [unidad fraseológica] de la LO le corresponde otra UF de la LM, la cual presenta el mismo significado denotativo y connotativo, la misma base metafórica, la misma distribución y frecuencia de uso, las mismas implicaturas convencionales, la misma carga pragmática y similares restricciones diastráticas, diafásicas y diatópicas.

-

[9]

Two interjections which are prototypically related to a phatic meaning have been included, namely absolutely and right. The uses selected have an expressive component.

-

[10]

Matamala and Lorente (in press) present an interesting study of combinations in Catalan sitcoms.

-

[11]

The corpus also shows that in some cases fuck has been translated into Sp. mierda Cat. merda (lit: ‘shit’).

-

[12]

Rojo and Valenzuela (2000) analyze different ways to translate fucking into Spanish. See also Adam (1998), who focuses on the French translations of fuck and fucking.

-

[13]

From a semantic point of view, expressive interjections can be classified into three groups: (i) sexual and eschatological words, (ii) blasphemes and religious expressions, (iii) qualities. For a semantic analysis of the interjections, see Cuenca (2004).

-

[14]

Matamala’s (2004: sections 7.1 and 10.3) analysis, based in sitcoms in English, Catalan and the Catalan dubbed version of the English sitcoms, also provides interesting information. She identifies more expressive interjections related to religion in English than in Catalan, where sexual and eschatological expressions are more frequent and varied; in the dubbed version eschatological expressions generally translate into eschatological forms, while religious ones translate either in religious or eschatological.

-

[15]

The table includes the general strategy and also combinations of two strategies (figures between parentheses). The figure corresponding to combinations has been already added to the final number.

-

[16]

Nord (1997: 76) proposes a functional classification of translation errors, which includes four categories: pragmatic, cultural, linguistic and text-specific. She defines pragmatic translation errors as those “caused by inadequate solutions to pragmatic translation problems such as a lack of receiver orientation,” and linguistic errors as those “due to deficiencies in the translator’s source or target-language competence” (1997: 77).

-

[17]

Guau is a graphic adaptation of English wow, and corresponds to the Spanish onomatopoeic word used for the bark of a dog.

-

[18]

Similar problems can be identified in second language performance, as the interesting corpus analysis by Romero Trillo (2002) shows. Romero compares the use of discourse markers in adult and children native and non-native speakers of English and observes remarkable differences in adult proficient L2 speakers who fail to use some markers. The author describes the process as “pragmatic fossilization,” that is, “the phenomenon by which a non-native speaker systematically uses certain forms inappropriately at the pragmatic level of communication” (2002: 770).

References

- Adam, J. (1998): “The four-letter word, ou comment traduire les mots fuck et fucking dans un texte littéraire?,” Meta 43-2, pp. 236-241.

- Ameka, F. (1992): “Interjections: The universal yet neglected part of speech,” Journal of Pragmatics 18-2/3, pp. 101-118.

- Baker, M. (1992): In Other Words. A Coursebook on Translation, London and New York, Routledge.

- Castro, X. (1997): “Sobre la traducción de guiones para la televisión en España,” <http://www.xcastro.com/peliculas.html>.

- Chaume, F. (2004): “Discourse markers in audiovisual translating,” Meta 49-4, pp. 843-855.

- Corpas, G. (2000): “Fraseología y traducción,” V. Salvador and A. Piquer (Eds.), El discurs prefabricat. Estudis de fraseologia teòrica i aplicada, Castelló, Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, pp. 107-138.

- Corpas Pastor, G. (2001): “La traducción de unidades fraseológicas: técnicas y estrategias,” I. de la Cruz (Ed.), La lingüística aplicada a finales del siglo XX. Ensayos y propuestas, Alcalá, Universidad de Alcalá, vol. 2, pp. 779-787.

- Coulmas, F. (1981): “Introduction: Conversational Routine,” F. Coulmas (Ed.), Conversational Routine. Explorations in Standardized Communication Situations and Prepatterned Speech, The Hague, Mouton, pp. 1-17.

- Cuenca, M. J. (2000): “Defining the indefinable? Interjections,” Syntaxis 3, pp. 29-44.

- Cuenca, M. J. (2002a): “Els connectors i les interjeccions,” J. Solà et al. (Coords.), Gramàtica del Català Contemporani, Barcelona, Empúries, vol. Sintaxi, chap. 31, pp. 3173-3237.

- Cuenca, M. J. (2002b): “Translating interjections for dubbing,” Studies in Contrastive Linguistics. Proceedings of the 2nd International Contrastive Linguistics Conference. (Santiago de Compostela, October, 2001), Santiago de Compostela, Servicio de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, pp. 299-310.

- Cuenca, M. J. (2004): “Translating interjections: an approach from grammaticalization theory,” Augusto Soares da Silva, Amadeu Torres, Miguel Gonçalves (Eds.) Linguagem, Cultura e Cognição: Estudos de Linguística Cognitiva, vol. 2, Coimbra, Almedina, pp. 325-345.

- Cuenca, M. J. and J. Hilferty (1999): “Grammaticalización,” Introducción a la lingüística cognitiva, Barcelona, Ariel, chapter 6.

- Goffman, E. (1981): Forms of talk, Oxford, Blackwell.

- Gómez Capuz, J. (1997): “Towards a typological classification of linguistic borrowing (illustrated with Anglicisms in Romance Languages),” Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 10, pp. 81-94.

- Gómez Capuz, J. (1998): “Pragmática intercultural y modelos extranjeros: la interferencia pragmática en los doblajes al español de películas y seriales norteamericanos,” A. Sánchez Macarro et al. (Eds.), Monographic Volume on Intercultural Pragmatics. Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis Lingüístics 4, pp. 135-151.

- Gómez Capuz, J. (2001): “Usos discursivos anglicados en los doblajes al español de películas norteamericanas: hacia una perspectiva pragmática,” I. de la Cruz (Eds.), La lingüística aplicada a finales del siglo XX. Ensayos y propuestas, Alcalá, Universidad de Alcalá, vol. 2, pp. 809-814.

- Hopper, P. and E. C. Traugott (1993): Grammaticalization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Matamala, A. (2004): Les interjeccions en un corpus audiovisual. Descripció i representació lexicogràfica, Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

- Matamala, A. and M. Lorente (2005): “Combinatòria d’interjeccions i llengua oral,” Actes del XIIIè Col·loqui Internacional de Llengua i Literatura Catalanes (Girona, 2003), Barcelona, Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, vol. 2.

- Nord, C. (1997): Translating as a Purposeful Activity. Functional Approaches Explained, Manchester, St. Jerome.

- Rabassa, G. (1991): “Words cannot express… The translation of cultures,” W. Luis and J. Rodríguez (Eds.), Translating Latin America: Culture as Text, New York, Binghamton.

- Rojo López, A. y J. Valenzuela (2000): “Sobre la traducción de las palabras tabú,” Revista de Investigación Lingüística, 1-3, pp. 207-220.

- Romero Trillo, J. (2002): “The pragmatic fossilization of discourse markers in non-native speakers of English,” Journal of Pragmatics 34, pp. 769-784.

- Valero Garcés, C. (2001): “Las fórmulas rutinarias en la comunicación intercultural: la expresión de emociones en inglés y en español y su traducción,” I. de la Cruz (Eds.), La lingüística aplicada a finales del siglo XX. Ensayos y propuestas, Alcalá, Universidad de Alcalá, vol. 2, pp. 635-639.

- Wilkins, D. P. (1992): “Interjections as deictics,” Journal of Pragmatics 18-2/3, pp. 119-158.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

English expressive secondary interjections and their translations into Spanish and Catalan

Table 2

English expressive secondary interjections combined and their translations into Spanish and Catalan

Table 3

Strategies used to translate secondary interjections

Table 4

Strategies used to translate English secondary interjections: Spanish compared with Catalan

Table 5

Strategies used to translate English secondary interjections: Catalan compared with Spanish

10.7202/009785ar

10.7202/009785ar