Résumés

Abstract

“Mills & Boon” has become shorthand for “trashy” entertainment, yet little is known about how the books are treated materially in their circulation. This article reports on a project that followed the material lives and afterlives of 50 Australian-authored novels published by Harlequin Mills & Boon between 1996 and 2016. We analyze visual and textual data about these books collected via social media to explore uses and values attached to category romance. First, we show that the books’ ongoing circulation is due both to their publishers’ practices, and to the behaviours of genre insiders. Second, we note that most participants demonstrated “genre competence” and genre-based sociality, confirming the highly networked nature of the romance “genre world.” Third, we find that category romance is routinely shelved apart from other books, explicitly marking them as distinctive. Finally, we argue that “shelfies” of romance collections undercut notions of trash by reframing them as treasure.

Keywords:

- Popular romance fiction,

- shelfies,

- Harlequin,

- Mills & Boon,

- social media

Résumé

La maison « Mills & Boon » est synonyme de plaisir coupable, mais on en sait fort peu sur ce qui caractérise le traitement de ses livres sur le plan matériel. Le présent article décrit un projet qui a retracé « la vie » (dans leur incarnation matérielle et au-delà) de cinquante romans d’autrices australiennes publiés par Harlequin Mills & Boon de 1996 à 2016. L’analyse de données visuelles et textuelles recueillies sur les réseaux sociaux nous permet d’explorer les usages et les valeurs associés au genre du roman d’amour. Nous montrons que la circulation des livres est attribuable à la fois aux pratiques de l’éditeur et au comportement des adeptes du genre. L’univers du roman d’amour s’appuie sur des réseaux raffinés, la plupart des intervenants se caractérisant par leur « compétence de genre » et par la socialité qui y est associée. Par ailleurs, nous notons que les romans d’amour se retrouvent rarement sur les mêmes rayons que les autres romans, ce qui en soi les rend distincts. Enfin, nous soutenons que les photos de collections de romans d’amour diffusées sur les réseaux sociaux incitent à recadrer la perception : les plaisirs coupables prennent dorénavant valeur de trésors.

Mots-clés :

- Romans d’amour,

- “shelfies”,

- Harlequin,

- Mills & Boon,

- réseaux sociaux

Corps de l’article

In Episode Two of The Bachelorette Australia in 2016, host Osher Günsberg outlined the first group date—a photo shoot for four new Mills & Boon books by Australian authors—saying, “Harlequin Books publishes the biggest name in romance novels worldwide, Mills & Boon.” Günsberg’s introduction highlights the virtually synonymous relationship between Mills & Boon and popular romance across the UK and the Commonwealth.[1] As Bachelorette Georgia Love said, “Mills & Boon means romance.” The partnership of Mills & Boon and The Bachelorette (the longest-lived romance reality television franchise in the world), the construction of this group date, and the subsequent production and marketing of the Bachelorette novels traded on the recognizability of the Mills & Boon brand in Australia.[2] Additionally, this episode underlined questions for us about the commercial and material distinctiveness of category romance.[3]

For example, Günsberg described the Bachelorette books as “a new series of romance novels Mills & Boon are doing set in the Australian outback.” The books are, however, not “new releases” in the usual sense, but collections of previously published novels, retitled and rebranded. Mills & Boon books are conventionally viewed as slim mass-market volumes produced at breakneck speed: they sit on retail shelves for the month of their release; unsold copies are destroyed; and purchased copies, once read, are disposable. The evolution of digital publishing in the twenty-first century complicates ideas of disposability, as backlist titles stay “in print” as ebooks. However, the paperback covers and the associated promise to viewers of physical volumes were at the centre of this cross-media collaboration, sparking questions about the status of print Mills & Boon in contemporary popular culture.

Mills & Boon is shorthand for “trashy” entertainment—to be consumed and disposed of, not to be retained. However, the repackaging and recirculation of backlist titles as “new” Bachelorette tie-in editions highlighted and reinforced to us that the production and distribution of Mills & Boon is more commercially and socially nuanced than the shorthand suggests. We therefore set out to investigate where and how print Mills & Boon books circulate in contemporary culture. Our initial interest was in the recycling and repackaging of previously published stories, a major but understudied feature of Harlequin’s business model. This soon evolved into a bigger question about the location and circulation of print category romance: as new books telling new stories, new books telling old stories, used books; items bought, sold, borrowed, discarded, or kept.

This article reports on the “Summer of Romance,” a project that followed the material lives and afterlives of Australian-authored category romance novels published in Harlequin and/or Mills & Boon lines between 1996 and 2016. With a view to asking new questions about category romance, it takes a different approach to those that have dominated research on popular romance fiction since Radway’s 1984 book Reading the Romance. Studies of the genre frequently focus on the twinned objects of the romance novel and its (mostly female) reader. This article examines the circulation of books as material objects rather than focusing on the analysis of texts and/or readers.

Methods and Background

Using the National Library of Australia’s (NLA) catalogue, we selected 50 category romance novels by Australian authors first published by Harlequin and/or Mills & Boon between 1996 and 2016 (10 each from 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011, and 2016). We collected visual and textual data about the existence and locations of physical copies of these books over three months (December 2016-February 2017) across three social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter). We obtained approval from the Tasmania Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee to solicit data from social media users to investigate “how and where print editions of [Harlequin Mills & Boon] novels by Australian authors circulate after their publication” (Participant Information Sheet). We set up research team accounts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter,[4] and used these and our personal social media accounts to recruit participants to share “shelfies” of the 50 books on our Facebook page and/or by using the hashtag #loveyourshelfie on Instagram and Twitter. For the purposes of this research—which uses, rather than studies, social media—we defined “shelfie,” clearly a derivation of “selfie,” loosely: a photograph of one or more novels “on location.” Using a “scavenger hunt” ethos, we solicited shelfies of the books from social media users to discover their locations and mobilities over one Australian summer.

We used the network analysis tool Netlytic to collect and analyze some aspects of our data. Netlytic builds datasets by collecting text and participant information from social media. Through Netlytic, we used hashtags to retrieve tweets and Instagram posts, and retrieved all posts from the project’s public Facebook page. Data not obtainable using Netlytic was collected manually.

Category romance in Australia

Category romance is virtually synonymous with Harlequin and Mills & Boon, depending on national context. It is distinguished from other types of romance novels largely by format. A category romance is published in a named and sub-branded series called a “line.” Some lines are distinctive to national territories, and others are named differently between territories despite containing the same content. Each line has publisher guidelines, which dictate length, character types, plot elements, historical and geographical setting, level of sexual content, and tone. Each line’s branding is scaffolded by the overarching publisher brand, ensuring the books are immediately recognizable and categorizable. The packaging and presentation of multi-territory lines vary from territory to territory. Unlike other types of books, category romance novels are not sold in chain or independent bookstores in Australia: rather, at the time of writing, new print editions are available from discount department stores (e.g., Kmart, Big W, Target), online retailers (e.g., Amazon Australia, Booktopia), and the Mills & Boon website, including through subscription packages. New print editions of category romance novels kiss retail shelves fleetingly, rather than linger on them. Like magazines, they are released monthly and they only remain on retail shelves until they are superseded by the next month’s catalogue; they do, nevertheless, have ISBNs rather than ISSNs. Category romance is as distinctive in the wider fiction industry for its distribution system as it is for its central narrative elements (a spotlight on the travails of a heterosexual couple, the guarantee of a happily-ever-after ending).

Publisher and line branding dominates the covers of standard category romance novels, which are printed as mass-market paperbacks. From the logo and tagline for each line to trope hooks appended to back-cover blurbs (e.g., “A little office romance…”),[5] Mills & Boon books are densely coded invitations to buyers. In Australia, these codes are inflected by national context, which is evident in the focus on Australian authors and settings for the Bachelorette books.

Category romance publishing in Australia is “globally connected,” but it is also “nationally distinctive.”[6] In a peripheral publishing market such as Australia, Mills & Boon encapsulates the persistence of national market identities in the production and distribution of a genre that aspires to embrace the globe.

Carter identifies Harlequin as the most prolific publisher of Australian-authored fiction from 2000 to 2013.[7] Studies of popular romance frequently include evidence of the genre’s volume and mass production in order to justify taking the genre seriously.[8] The inverse of scholarly claims for the genre’s mass scale is the common argument that romance suffers from its relative invisibility in mainstream literary culture and concomitant neglect by the academy.[9] Romance is both everywhere and not to be seen.

Curthoys and Docker describe Mills & Boon as a “roaming, punitive signifier” for “sub-literature, para-literature, trash, schlock.”[10] While the perception of Mills & Boon and the wider romance genre as “trash” has been refuted at length by scholars seeking to speak up for the genre’s literary merit,[11] the publishing practices outlined above do not necessarily contradict such a point of view. Conversely, Harlequin and Mills & Boon appear to celebrate the ephemerality of their books and exploit the infinite reproducibility of the romance narratives that are cornerstones of their business. Their practices suggest that category romance is not subject to the same logics of canonicity or archivability as other types of novels. This is reflected in the material form of the books. A paperback Mills & Boon—say, Anne Mather’s August 2017 novel, An Heir in the Marriage Bed—is not just a smaller and slimmer object than a literary novel released in the same month such as Sally Rooney’s Man Booker long-listed Normal People (while length can vary line to line, category romance novels are typically approximately 55,000 words long). It is also saturated with the publisher’s promise that this book will deliver an equivalent experience to others in the line. The promise of a literary novel like Rooney’s is exceptionality, which is communicated through paratextual markers such as author endorsements, prize nominations, and distinctively sparse cover design; whereas the promise of a Mills & Boon novel like Mather’s, with its template cover and prioritization of publisher and line over author and title, is typicality.

Mills & Boon catalogues are complicated by “repackaging” programs. Regularly, backlist titles are re-released with new covers as single title volumes and/or reprinted in new anthologies. The latter contain between two and six titles. For example, Mills & Boon UK published six anthologies in their “One Night of Consequences” collection between October 2017 and March 2018, each containing three previously published stories whose connection is indicated with a subtitle; the first book released in this collection, One Night: Exotic Fantasies, contains stories first published in 2009, 2012, and 2015.

The Bachelorette books likewise signal the constant strategic experimentation of Mills & Boon as they seek to access new markets. Each book collects three titles by a mid- or late-career Australian romance author: Emma Darcy, Michelle Douglas, Barbara Hannay, and Marion Lennox. Although these authors are highly regarded in the Australian romance “genre world,”[12] their names were not mentioned in the episode. Likewise, the selected titles were not framed as “classics” of category romance; instead, they were retitled with the names of each book’s hero and heroine, with the original titles buried in the copyright page. The publisher’s apparent disinterest in linking category romance to the logic and values of literary quality was signalled in the episode by Cristina Lee, then Operations and Commercial Director for Harlequin Australia. Like Günsberg, she stressed the volume and reach of Harlequin’s output but did not offer details about the authors or titles selected: she simply said, “we sell two books every one second worldwide.”

We selected one story included in a Bachelorette book in our list of 50 titles: Hannay’s Claiming the Cattleman’s Heart. A brief publication history focused on the print North American and Australian editions of this novel is indicative of the patterns of reuse and rebranding that characterize category romance publishing. It shows also how the distribution system flexes to a complex and rapidly changing “glocal” romance market. Claiming the Cattleman’s Heart was first published in North America in December 2006 in Harlequin’s “Romance” line. It appeared in the same month in Australia’s Mills & Boon “Sweet” line, as the cover story in a “2 stories in one” volume that also included a “bonus Christmas novel,” Meet Me Under the Mistletoe, by American author Julianna Morris. Hannay is identified as an “Australian author” on the cover of this edition, a standard element on locally written Mills & Boon books. It was republished by Mills & Boon in Australia in May 2015 in the Hannay anthology Inheritance, along with two other previously published titles: A Wedding at Windaroo, first published in 2003, and Her Cattleman Boss, a 2009 title that also appears in the Bachelorette book. In 2016, Claiming the Cattleman’s Heart was retitled “Daniel and Lily” for the Bachelorette collection Home on the Station. That two of the stories in this volume had been packaged together by Mills & Boon in the previous year indicates that category romance is governed by a logic of impermanence and adaptability: novels are routinely and sometimes rapidly re-released in multiple iterations and combinations. A deeply anti-literary publishing attitude determines how the books are produced and sold, and guides expectations about where and how they might be found. Anyone seeking a specific Mills & Boon title in print cannot go to a bookstore or even necessarily to a library and request it in the same way that they would for most books.[13] Instead, they must pursue other avenues. This article explores some of those avenues: how difficult is it to find Mills & Boon print editions once they leave retail shelves?

We sought to include a wide variety of books in our corpus of 50 titles, encompassing, for example, authors with profiles varying from debut to late career, books released in multiple editions, and authors and titles with which we were familiar and others that we knew little to nothing about. We also aimed to include novels from a variety of lines. Our decision to restrict this study to the output of one nation’s romance writers made this last criterion a challenge because Australians write more for some lines than for others; there were, for example, many Australian-authored “Romance” and “Medical” titles published in the relevant years, but relatively few in the “Historical” line, and we were unable to include any from the “Love Inspired” or “Suspense” lines.[14] Our list includes titles by 33 authors. There are five books by Lennox; four each by Darcy and Hannay; three each by Miranda Lee and Carol Marinelli; two each by Amy Andrews, Joan Kilby, and Margaret Way; and one book each by a remaining 25 authors. In broad terms, this corpus reflects the collective author profile of Harlequin’s Australian stable, which, in any given year, includes highly prolific long-signed authors, mid-career authors with steadily growing backlists, and emerging and debut authors. In terms of our method of book selection, we found more authors and titles to choose from in more recent years, because the number of Australians writing category romance has increased markedly across the period under examination, as has the volume of Australian-authored titles. The number of Australian-authored category romances published by Mills & Boon has more than tripled since 1996, and the number of Australian authors published by them has more than doubled.[15] This pattern is consistent with the overall growth in genre fiction by Australian authors: Driscoll et al. have found that “total output” of novels by Australians across the genres of crime, fantasy, and romance “has increased almost fivefold since 2000” and that the greatest increase is in romance.[16]

The sheer volume of category romance published by Harlequin and Mills & Boon (even with a restricted focus on Australian-authored titles) and the continuous adaptation of their marketing strategy and distribution system makes it difficult to study these books. As Thompson explains, “[w]riting about a present-day industry is always going to be like shooting at a moving target: no sooner have you finished the text than your subject matter has changed—things happen, events move on, and the industry you had captured at a particular point in time now looks slightly different.”[17] In this project, we sought to map the circulation of Mills & Boon novels in a specifically local book culture; however, our methodology as outlined in the next section would be replicable in or across other territories. What Thompson calls “[i]mmediate obsolescence” is a particular challenge in studies of category romance,[18] but this heightened need to be conscious of the dynamism and volatility of the publishing industry should not be a deterrent to research: instead, these books offer excellent opportunities to study genre as it happens.

#loveyourshelfie: using social media to collect data about books

We asked participants to seek out our selected books, photograph them in situ, and then share their image(s) to social media with a description of where they found them. The instructions provided on the Participation Information Sheet and circulated via social media were as follows:

-

You are invited to do one or both of the following, as many times as you wish during the data collection period (1 December 2016–1 March 2017):

Find and photograph one or more of 50 selected books published by Harlequin Mills & Boon between 1996 and 2016, and share your photograph(s) on Instagram and/or Twitter with the hashtag #loveyourshelfie, or by posting it to the Summer of Romance Facebook page.

Share a written response to the question “Where did you find this book?” on Facebook, Instagram, and/or Twitter.

We did not ask participants to style or arrange the books or to manipulate the aesthetic or compositional properties of photographs; participants could therefore decide to contribute photographs of the books exactly as they found them or to arrange the books or edit the images to represent their relationship or attitudes to them.

Maguire considers images of books on #bookstagram, an Instagram ad-hoc community that involves users posting images of books they have read, typically with commentary. For Maguire, shelfies offer more than “pretty pictures of books”: “they present a curated collection of works that the bookstagrammer thinks is valuable.”[19] For Maguire (who is an active bookstagrammer), the effort users put into visually representing the themes or narratives of the books they photograph, as well as their written commentary, “adds value to [their] reading experiences.”[20] We were therefore conscious, in our design of this project, that participants who already shared or engaged with shelfies online—especially if they were also Mills & Boon consumers—were likely to curate their images in deliberate ways. We kept the instructions to participants simple in order to allow for curatorial and/or community-building behaviour without necessarily soliciting or directing it.

Writing about book communities on YouTube, Perkins shows how online communication facilitates book-based fandom: treating reading, typically regarded as a solitary pastime, as a deeply social and networked activity. Importantly, Perkins argues that in the context of “BookTube,” books act as “boundary objects that unite the community and help it to continue and flourish.”[21] We anticipated that the 50 books had the capacity to play a similar role in our project, particularly if participants tagged authors (or were authors themselves) or an official Mills & Boon account (e.g., @MillsandBoonAUS) in their posts, or used hashtags such as #millsandboon or #romance to promote their participation to other readers and industry players.

In Maguire’s and Perkins’s accounts of bookish behaviour on social media, images of individual books implicitly or explicitly tie the object to the act of reading. The popularity of the hashtag #amreading on Twitter and Instagram suggests that the “ethos of bookishness”[22] that pervades the digital literary sphere fosters and exploits the idea that a networked sensibility enhances the act of reading. However, in the simplest terms, our interest when planning our methodology was in books as objects and their locations. Participants were not asked to read the selected books, or to purchase, borrow, or collect them. Instead, our project design treats the presence of a book in a specific location as a material trace of its production and consumption that might be recorded by an individual, but does not necessarily seek to capture that individual’s tie to the book(s).

As there are very few published studies that consider (book) shelfies, we drew on research on “selfies” to design the methods of this project. We solicited shelfies to collect and analyze new visual evidence of contemporary cultural practices with, and attitudes about, Mills & Boon. As Vivienne and Gómez Cruz and Thornham show, selfies can function as more than exercises in self-representation or identity affirmation.[23] In our thinking about shelfies, we adapt Gómez Cruz and Thornham’s assertion that selfies should be understood as part of a broader set of sociocultural relations.[24] We sought to activate specific aspects of these relations in order to collect data about the circulation of category romance in contemporary culture, rather than to study the meaning or significance of the taking and sharing of shelfies as such. While we understood that the shelfies that came to form our dataset might function as self-representations for participants, reflect how they use social media, and/or mediate individual and social relationships with books, these issues are not the focus of this article. Instead, it foregrounds what we learned from the documentary function of shelfies: what they include, what they do not include, how they are framed, and where they were taken.

We made one major change to our communication protocol early in the data collection period by adding the hashtag #no50books to allow participants to document their searches even if they could not find any titles. #no50books was mostly used by participants to record where they found Mills & Boon books outside our corpus. It therefore provided valuable information about where participants rightly assumed they would find category romance. The necessary addition of the #no50books option reveals a flaw in our original project design. Initially, because the specific 50 titles were difficult to find, some participants seemed to be deterred from continuing engagement. #no50books mitigated this exclusion issue, as it allowed participants to report on scavenger hunts even if they could not find the titles, thus providing the research team with useful data.

Highfield and Leaver explain that visual methods of communication on social media have not been as widely studied as text-based methods.[25] Arguably, this is in part because tools for automated data collection privilege textual communication. For instance, we used Netlytic to gather our data, but the automated data collection and resulting network analysis did not account easily for images, which we therefore archived manually. Hashtags and comments were key to our data collection using both automatic and “by hand” methods and enabled our subsequent analysis.

Our loose definition of shelfie, together with the project’s communication guidelines, facilitated uniform participation across the three platforms despite their rhetorical specificities (e.g., Instagram is primarily visual, whereas Facebook allows for longer form text-and-image-based communication). On Twitter and Instagram, the project-specific hashtags were crucial for us to track participation and collect the photographs. They also enabled interaction among users, and user-to-user communication seemed to increase the number of participants. We used a blog (https://summerofromanceutas.com/)—linked on social media—to disseminate the Participant Information Sheet and to provide downloadable checklists of the 50 books.

Results

Over the three-month period of data collection, 45 unique participants contributed a total of 192 shelfies. The number of titles from the corpus captured in a single photograph ranges from 1 to 23. 46 of the 50 books appear in at least one shelfie. The most photographed book is in 14 shelfies, followed by 3 titles in 10 shelfies each, 5 titles in 9, and 5 titles in 8. 8 of the 14 titles that appear in 8 or more shelfies were first published in 2011. In broad terms, 6 “types” of people contributed shelfies: authors of the 50 books, other romance authors, librarians, organizational accounts (e.g., book blogs), members of the project team, and other general social media users. The photographs were mostly taken in Australia in 4 “types” of location: private collections, retail outlets where new books are sold, retail outlets where secondhand books are sold, and public libraries.

The 50 Books

The titles published most recently appear in the most shelfies, with 57 per cent including titles from 2011 or 2016 (Fig. 1). Books first published in 2011 appear most often (35%) and the least represented year is 2001 (12%).

Figure 1

The 14 titles that appear in 8 or more shelfies are all by authors of multiple novels (Fig. 2). The authors of these titles have published between 13 (Cleary) and 147 (Lennox) works, 10 of the 12 have published over 40 works each, and 3 over 100.[26]

Figure 2

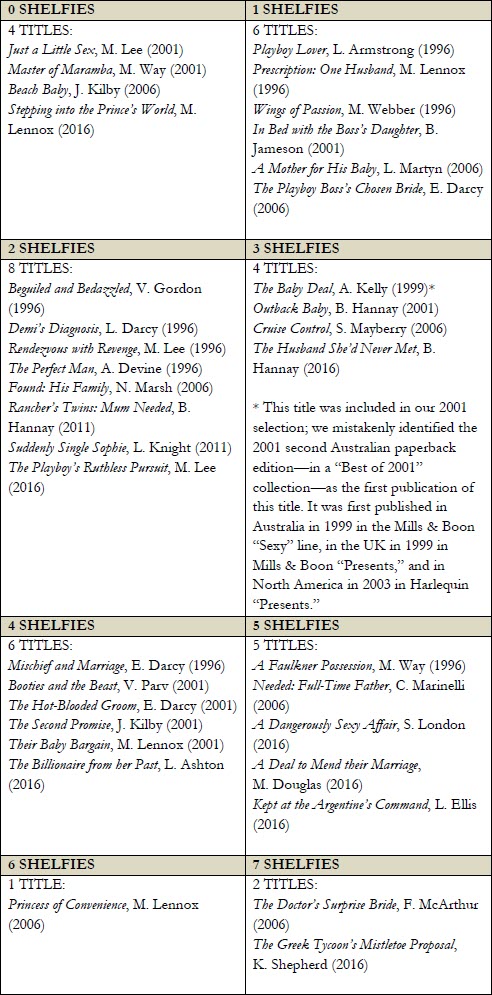

Only four titles do not appear in a single shelfie (Table 1). These titles do not appear to have markedly different publication histories to the frequently found titles. For example, at the time of writing, Kilby, the author of Beach Baby, is listed as the author of 17 works on AustLit. Beach Baby was first released in Australia in August 2006 in the “Super Romance” line, with an “Australian Author” strapline. According to the book’s record in the NLA catalogue, the cover identifies the first (and only) Australian paperback edition of this book as an “Anniversary Special: Super Romance’s 500th book.” It was published in the UK in August 2006 and North America in August 2007, also in “Super Romance,” but with nationally specific covers. Lennox’s Stepping into the Prince’s World was similarly widely distributed. It appeared in an August 2016 Mills & Boon “Cherish” 2-in-1 in the UK, a “Forever Romance” 2-in-1 in Australia, and as a standalone September 2016 Harlequin “Romance” in North America. The similar distribution histories of these books are representative of the corpus, provoking the question of why some titles were found regularly and some not at all.

Table 1

Titles in 0 - 7 shelfies

Most of the shelfies of the 50 titles are of English-language paperback Mills & Boon editions, and most of these are Australian editions. Exceptions to this pattern include photographs of North American editions contributed by a participant in the US; photographs showing multiple editions of titles contributed by their authors; images of foreign-language editions; and shelfies of hardback library copies. Amanda Gardner, a romance fan based in Florida, shared 11 shelfies on Facebook, including 12 titles. These included images of her author- and line-based collections and photographs taken earlier in the year at her local Walmart to record the US release of titles by favourite authors (Fig. 3). Other non-Australian editions were pictured in shelfies of “author copies.” For example, Melanie Milburne tweeted a photograph of her “last copies. US. UK. Hardback and Aussie” of The Most Scandalous Ravensdale. While the majority of the 50 books have been translated into multiple languages, we received very few shelfies of foreign-language editions. Andrews, the author of Mission: Mountain Rescue, photographed her copy of the Afrikaans edition and McAlister found Portuguese editions of Darcy’s The Playboy Boss’s Chosen Bride and Annie West’s Prince of Scandal (Fig. 3) in a library. Hardback copies, including large print editions, feature almost exclusively in shelfies taken at libraries. These special library editions are not available for public retail circulation, though author and ex-library copies do appear in the dataset in private collections.

Figure 3

Prince of Scandal: Harlequin “Presents” 2011 North American edition in a personal collection (L) and Harlequin “Jessica” 2014 edition at Marrickville Library, New South Wales (R).

The majority of books captured in shelfies were in post-retail circulation through libraries, charity shops, and secondhand bookstores, or held in a more-or-less permanent collection by an individual participant. These “used” books range from books that appear in excellent condition, to books showing minimal signs of wear such as mild cover distortion, to torn, stained, or creased books that appear to have passed through many hands. For example, compare the like-new copy of Sarah Mayberry’s Cruise Control in a to-be-reread basket next to a participant’s bed to the ex-library copies of Way’s A Faulkner Possession and Darcy’s The Hot-Blooded Groom in a “Salvos” store in Sydney (Fig. 4).[27]

Figure 4

Ex-library copies of A Faulkner Possession and The Hot-Blooded Groom on the category romance shelf at a Sydney charity store (L) and Cruise Control, in a basket of books to be “reread” (R).

Unsurprisingly, Hannay’s Claiming the Cattleman’s Heart was the most frequent title to appear in shelfies of new (unsold) books, due to its inclusion in a Bachelorette volume. It is also one of the few titles participants reported finding in reprint anthology editions. Most of the photographs show standalone or duo editions that have story titles on the cover and spine. Exceptions include two photographs of 2016 collections taken in Tasmania, Australia: Helen Bianchin’s Mistress Arrangements (including Desert Mistress) at a department store, and Volumes 1 and 2 of Marinelli’s The Kolovskys of Russia on the Mills & Boon shelves at a secondhand bookstore (Volume 2 includes The Devil Wears Kolovsky).

The results outlined above are as much about the shelfie photographers as they are the books themselves. Which books were found was highly dependent on the people who found them, making the project participants as interesting a subject for analysis as the titles.

Project Participants

Most participants who contributed shelfies communicated an existing personal or professional interest in romance novels, especially category romance. They included writers, readers, and collectors, librarians, and other book-related professionals—all roles that overlap. Shelfies were contributed by 8 of the authors who wrote at least one of the 50 novels; 5 organizational users (e.g., libraries, blogs); the 4 team members; 29 other participants; and one “superparticipant”[28] who contributed 113 individual posts. The participants were overwhelmingly from Australia.

The most active participant on Twitter and Facebook was the research team account. This “campaign effect” was amplified on Twitter results by the active engagement of the University of Tasmania (@UTAS_) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5

When we leave aside researcher participation, the most active participants were people who share and promote their roles as romance authors, readers, and/or cultural intermediaries on social media. The top ten posters on Facebook (Fig. 5) include four authors included in the corpus (Douglas, Anne Gracie, Stefanie London, and West), the category romance writer Rachel Bailey, and four avid readers connected to one or more of these authors via Facebook. There is similar evidence of strong genre affiliations for many participants. For example, participants on Instagram included Kate Cuthbert, Managing Editor of Escape Publishing, an Australian Harlequin digital-first romance imprint; romance fiction editor and author assistant Nas Dean, and romance author Melanie Scott.

What is most striking about Figure 5 is that 30.4 per cent of posts on Twitter came from one person, Fiona Marsden, at the time an aspiring author yet to be published by Mills & Boon. Marsden is a dedicated category romance reader and collector. She committed early to the scavenger hunt ethos of the project. She stated her aim to find all 50 books, participated across all three platforms, stayed active throughout the summer by replying to others’ posts, and purchased books from online retailers that she was unable to locate through physical searches (Fig. 6). On January 8, 2017, she tweeted a visual update of her progress with a photograph of 31 books, including 23 of the titles, 7 appearing twice. Marsden’s investment in the project extended to anticipating results. She noted titles that appeared most often, tweeting about the “ubiquitous #PrinceOfScandal,” and used hashtags and other text to suggest how the results might be coded, such as date hashtags, #reprint, and “owned” and “Personal copy.”

Figure 6

Marsden’s committed participation was unusual, but even sporadic participants were strongly linked to the romance genre. For example, New Zealand author Nalini Singh participated once, commenting “I have this too!” in response to a shelfie of Tallie’s Knight. Similarly, Australian author Erica Hayes posted a shelfie of A Faulkner Possession: “One for the #loveyourshelfie crowd—a 1996 catch!”

Figure 7

Our social media research tapped into established online genre networks in Australia. We used Netlytic data visualization tools to examine the frequency of participant activity and to picture direct communication between participants who used #loveyourshelfie on Twitter. Most of the participation on this platform was interactive (Fig. 7), with participants engaging directly with each other and with the project account. The genre-based connections and friendships of participants were signalled when they tagged or mentioned each other. For example, Australian romance writer Fiona Lowe tweeted a shelfie of The Greek Tycoon’s Mistletoe Proposal: “This was a gift from @KandyShepherd when I saw her in Sydney in November :-).”

A high level of interactivity suggesting existing connections between participants was not limited to Twitter. For example, on Facebook, Douglas posted seven shelfies, including images of her own novel, A Deal to Mend their Marriage. She tagged the other authors in her posts and their responses indicate existing relationships. For example, she posted a shelfie of a signed copy of Prince of Scandal—“Annie West is a perennial favourite. And I’m utterly delighted to have a hard cover edition”—to which West replied, “Aw, how lovely, Michelle. So glad to think you like this one.”

The collated data from across the three social media platforms confirms that our results may be skewed by the appeal of the methodology to genre insiders. For the most part, the “Summer of Romance” call for participants did not attract people with little to no existing interest or expertise in category romance. 38 per cent of participants who shared shelfies are traditionally published romance authors (Fig. 8); this percentage climbs when we add broader participation. For example, Leah Ashton retweeted a shelfie of The Billionaire from her Past: “Hooray! Was worried my book would never be found in the @ShelfieSummer project :-).” Similarly, West, the author of the most frequently found book in the project (Prince of Scandal), did not share a shelfie, but was a regular participant in other ways, such as liking and commenting on Facebook posts.

Figure 8

Numerous participants signalled their familiarity with the publisher, lines, authors, and/or individual titles through their responses to shelfies and through #no50books posts. The majority demonstrated expertise on category romance, especially through references to their experience as writers, readers, and/or collectors. For example, Australian romance writer Joanne Dannon commented on Instagram, “I used to keep all my books on my book shelves but I ran out of space. All my Mills and Boon books are now safely stored in my writing desk 😃.” On Facebook, Bailey gestured to her extensive collection, “I found another one! Anne Gracie’s Tallie’s Knight. I didn’t see it at first because it’s on my historical bookshelf, not the category bookshelf.” Bronwyn Jameson, the author of one of the selected books, posted on Facebook, “Sorting through my older category books today, I found this gem: Alison Kelly’s The Baby Deal.” Vassiliki Veros, a librarian currently completing her PhD on romance, posted a multi-book shelfie on Instagram:

I decided to start my #loveyourshelfie search by looking for titles amongst the books I own. Of the 50 titles I only had 2 books: Kelly Hunter’s With this fling and Amy Andrews’s Rescued by the dreamy doc (which is also an ex-library copy). Of the 33 authors listed I had 16 of their books on my shelf however I did not have most of the titles.

Overall, participants demonstrated high “genre competence” and genre-based social connections[29] Further, their contributions highlighted a key question for analysis as we received many shelfies from large personal collections: can this data provide an avenue to reconsider the vexed question of “value” in relation to Mills & Boon?

Book Locations

Our results show that people who organize and display category romance—such as distributors who stock shelves in discount department stores, volunteers in charity shops, librarians, authors, and readers—routinely shelve or stack them together and apart from other types of books. The common treatment of the Mills & Boon book as a distinct type of object (widespread, but radically unlike other books) is evident in the shelfies. Wherever they were taken, despite our call for images of specific titles, most of the photographs show one or more of the books grouped together with other category romance books and frequently show these allocated their own space adjacent to, but apart from, other types of books (Fig. 9).

Figure 9

Do Not Disturb and The Socialite’s Secret in romance trolleys at The Cog, a bookstore/cafe in Traralgon, Victoria (L), and Desert Mistress, Suddenly Single Sophie, The Costarella Conquest, and A Mother for His Baby in the category romance area at Wollondilly Library, Picton, New South Wales (R).

The locations in which the books were found fall into four categories: private collections, retail outlets where new books are sold, retail outlets where secondhand books are sold (“other retail”), and public libraries (Fig. 10).

Figure 10

The most common location is private collections. Images that we classified as “private collection” range from carefully composed photographs depicting a book that has been moved from its usual home to less artful photographs showing extensive category romance collections (Fig. 11). As mentioned above, several authors contributed photographs of books from their own collection that they had written and/or by other authors. We classified the locations of such shelfies as “private collection,” but there is an argument for classifying them as “professional collection” because of the depiction of work product and artefacts of professional relationships. For example, Valerie Parv shared a photograph of the North American Silhouette “Romance” edition of her Booties and the Beast on a shelf with 37 of her other books. Bailey, an author for the Harlequin and Mills & Boon “Desire” line, photographed the first Australian edition of the same title, a 2-in-1 edition in the “Sweet” line (2001). Bailey is a past recipient of the Valerie Parv Award, a mentorship scheme coordinated by Romance Writers of Australia. We retained the “private collection” classification because mapping such professional networks thoroughly is outside our scope; however, the capacity of our method to reveal these networks informs the analysis below.

Figure 11

Shelfies from private collections shared on Facebook (L) and Twitter (R).

The second most common location in which shelfies were taken is “other retail.” “Other retail” includes tip shops[30] secondhand bookstores, and charity shops—essentially, anywhere secondhand books can be bought.

While many of the books in collections appear to have had only one owner since their initial sale or, in the case of author copies, their publication, shelfies from libraries and “other retail” locations appear to show highly mobile, much-used cultural objects. Individual books show signs of wear and tear, such as split or creased spines, cover damage, dog-eared pages, stains, and multiple price stickers. Further, the organization practices for category romance captured in the images suggest products in constant circulation; if Mills & Boon novels are not identified by a book collector as “keepers,” they travel quickly and in bulk. Several of the photographs taken in retail outlets of new and secondhand books include pricing information that signals material value as much as it targets brand-loyal purchasers. For example, one shelfie from a charity shop pictures a copy of Tallie’s Knight in a basket labelled “Mills & Boon 50 cents each unless priced.”

Figure 12

Romance shelves at Kmart, Rosny, Tasmania (Top) and a librarian in the Mills & Boon section at Williamstown library with Rescued by the Dreamy Doc and The Costarella Conquest.

Many of the shelfies, especially those tagged #no50books, show books displayed en masse, immediately identifiable even in distant or blurry shots by their uniform size and colour-coded spines (Fig. 12). They are frequently tightly shelved or stacked using the full height and depth of tall bookshelves. Shelfies showing less than five books are close-ups of bookshelves or show books removed from storage. Our results confirm that category romance is a ubiquitous but unique genre product defined by tensions between mass production and distinctiveness, commerce and collectability.

Analysis and Conclusions

In her study of Australian romance, Flesch emphasizes the genre’s commercial and cultural invisibility. She writes:

Most mass market romance goes out of print within six months of publication. Some appear almost immediately in flea markets and book exchanges; some remain in public library collections for a year or two before being culled; many more disappear without a trace into private collections[31]

Our results prove that Mills & Boon books are not as ephemeral and untraceable as Flesch attests. While novels from earlier years were undoubtedly more difficult to find, they remain in transit and are readily locatable for significantly longer than the short period she suggests. This is due both to the publishing practices of Harlequin Mills & Boon, which reframes and republishes texts in new forms as a matter of course, and to the behaviours, consumption, and collection practices of their writers and readers. Our findings reveal the significance of sociality to the material lives and afterlives of romance novels.

If, as Thill argues, waste is “every object plus time,[32] a list of 50 books published across 20 years of monthly catalogues is a lot of potential waste. Thill explores how value attributed to objects, primarily through their use, re-use, and display, can shift attitudes of what is considered waste and what is not. The sheer number of Mills & Boon paperbacks ensures that some of the books end up as waste, but we did not receive a single photograph of a book treated as such. Our images were of books in circulation—whether waiting to be sold, resold, or borrowed—or already curated into collections. These books, so often considered “trashy,” are readily repurposed and reframed as treasure.

Participants communicated the high value of the books through the aesthetic arrangement of their collections—organized to show pleasure in their uniform design, in terms of colour and size—and through comments on photographs, such as, “Don’t they look so pretty all lined up together?” The consistent branding of Mills & Boon books through their format and paratext, used by the publisher to market the books at the initial point of sale, here becomes a key pleasure in curating and displaying one’s collection and a mechanism to tag other genre insiders (e.g., Figs. 4, 8, and 12).

Several participants used the project to showcase their own works and/or collections, and to connect to other authors and/or readers. This project confirmed the highly networked nature of the romance genre world. For most participants, the high value of category romance is a given, even though these books are regularly considered “trashy.” In this context, Mills & Boon books are “boundary objects,” activating and sustaining social connections.

This article does not provide a comprehensive geography of the locations and mobilities of category romance. However, it does provide insight into the value placed on Mills & Boon books by romance genre world insiders, and about how and where to find them. These books are both inside and outside conventional book culture. They exist in and move through locations that are adjacent to other bookish sites. There is clear evidence for this in our lack of shelfies from chain or independent bookstores, but even in the retail outlets where they are sold, new and secondhand, these books are set apart. For example, shelfies show them on branded shelves in book sections of discount department stores, and in discount bins in charity shops, rather than shelved among other books. One way to read these patterns is as evidence of their low quality, cheapness, and sameness. However, #loveyourshelfie shows that when the same shelving logics are applied in personal collections, they celebrate the books and register their aesthetic appeal, rather than index their infinite replaceability. Shelfies of Mills & Boon collections also undercut ideas of the book as innately disposable: here, what is often considered trash becomes treasure.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Lisa Fletcher is Associate Professor of English at the University of Tasmania. Her research on popular fiction includes Historical Romance Fiction: Heterosexuality and Performativity (Ashgate, 2008), Island Genres, Genre Islands: Representation and Conceptualisation in Popular Fiction (Rowman & Littlefield International, 2017; co-authored with Ralph Crane), and Popular Fiction and Spatiality: Reading Genre Settings (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). She is currently co-writing a book about bestsellers and the geography of the book market with Elizabeth Leane.

Jodi McAlister is a Lecturer in Writing and Literature at Deakin University in Melbourne. Her primary research interests are representations of romantic love in popular culture and the operations of the popular fiction industry. She has published widely in a range of journals, including Continuum and TEXT, and in numerous scholarly edited collections. She is currently working on her first monograph. She is also an author, and her young adult novels Valentine (2017), Ironheart (2018), and Misrule (2019) are published by Penguin Teen Australia.

Kathleen Williams is the Head of Media in the School of Creative Arts and Media at the University of Tasmania. Her research is centred around the social uses and understandings of media technologies. Her work on nostalgia, materiality and memory has been published in various anthologies and Alphaville, Fusion, and Transformative Works and Cultures.

Kurt Temple is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Tasmania. His research is primarily in digital scholarly editing and he is currently editing The Iron Age, Parts I & II for Digital Renaissance Editions (DRE). He works on popular authorship, particularly of the Early Modern period, and he has spent some time researching interwar popular authors.

Notes

-

[1]

Mills & Boon is an imprint of Harlequin Enterprises, a subsidiary of HarperCollins.

-

[2]

Juliet Flesch, From Australia with Love: A History of Modern Australian Popular Romance Novels (Fremantle: Curtin University Books, 2004); Jodi McAlister, “Bachelor Nation: The Construction of Romantic Love and Audience Investment in The Bachelor/ette in Australia and the United States,” Participations 15, no. 2 (2018): 343–64; Kelly McWilliam, “Romance in Foreign Accents: Harlequin-Mills & Boon in Australia,” Continuum 23, no. 2 (2009): 137–45.

-

[3]

The authors would like to thank Eliza Murphy for her research assistance on this project.

-

[4]

Ethics Ref No: H0016088. The participant information sheet is available on the project website: https://summerofromanceutas.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/hmbinfosheet3.pdf.

-

[5]

Bronwyn Jameson, In Bed with the Boss’s Daughter (in duo edition with Ashley Summers, Beauty in His Bedroom) (Chatswood: Harlequin Mills & Boon, 2001).

-

[6]

Beth Driscoll, Lisa Fletcher, and Kim Wilkins, “Women, Akubras and Ereaders: Romance Fiction and Australian Publishing,” in The Return of Print? Contemporary Australian Publishing, ed. Aaron Mannion and Emmett Stinson (Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2016), 67.

-

[7]

David Carter, “General Fiction, Genre Fiction and Literary Fiction Publishing, 2000-13,” in The Return of Print?, ed. Mannion and Stinson, 13; see also Driscoll, Fletcher, and Wilkins, “Women, Akubras and Ereaders.”

-

[8]

See Jay Dixon, The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon, 1909-1990s (London: Routledge, 1999); Diane Elam, Romancing the Postmodern (London: Routledge, 1992), 1; Paul Grescoe, The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance (Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 1996); Joseph McAleer, Passion’s Fortune: The Story of Mills & Boon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); Tania Modleski, Loving with a Vengeance: Mass-Produced Fantasies for Women (Hamden: Archon, 1982), 1; Janice Radway, Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature (London: Verso, 1994), 20; Pamela Regis, A Natural History of the Romance Novel (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), xi, 155–68; Catherine M. Roach, Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016); Eric Murphy Selinger and William A. Gleason, “Introduction: Love as the Practice of Freedom?”, in Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love as the Practice of Freedom?, ed. William A. Gleason and Eric Murphy Selinger (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), 1–21; Olivia Tapper, “Romance and Innovation in Twenty-First-Century Publishing,” Publishing Research Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2014): 249; Carol Thurston, The Romance Revolution: Erotic Novels for Women and a Quest for a New Sexual Identity (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 3.

-

[9]

See for example Driscoll, Fletcher, and Wilkins, “Women, Akubras and Ereaders”; Modleski, Loving with a Vengeance, 1; Regis, A Natural History, xi; Tapper, “Romance and Innovation,” 250.

-

[10]

Ann Curthoys and John Docker, “Popular Romance in the Postmodern Age and an Unknown Australian Author,” Continuum 4, no. 1 (1990): 23.

-

[11]

See for example Dixon, The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon; Regis, A Natural History; Laura Vivanco, For Love and Money: The Literary Art of the Harlequin Mills & Boon Romance (Penrith UK: Humanities-Ebooks, 2011).

-

[12]

Lisa Fletcher, Beth Driscoll, and Kim Wilkins, “Genre Worlds and Popular Fiction: The Case of Twenty-First-Century Australian Romance,” The Journal of Popular Culture 51, no. 4 (2018): 997–1015.

-

[13]

Vassiliki Veros, “A Matter of Meta: Category Romance Fiction and the Interplay of Paratext and Library Metadata,” Journal of Popular Romance Studies 5, no. 1 (2015): http://jprstudies.org/2015/08/a-matter-of-meta-category-romance-fiction-and-the-interplay-of-paratext-and-library-metadataby-vassiliki-veros/.

-

[14]

It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed account of the complicated transnational history of Harlequin and Mills & Boon lines, even for 1996–2016. Our corpus includes novels in lines that were in production throughout the period, lines that were launched and closed, and others that were split or merged.

-

[15]

These estimates were calculated by conducting Advanced Searches on AustLit for the relevant years for every title classified as a “novel” and published by “Harlequin,” “Harlequin Mills & Boon,” or “Mills & Boon.” We manually removed titles not published in category lines.

-

[16]

Beth Driscoll, Lisa Fletcher, Kim Wilkins, and David Carter, “The Publishing Ecosystems of Contemporary Australian Genre Fiction,” Creative Industries Journal 11, no. 2 (2018): 206.

-

[17]

John B. Thompson, Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century, 2nd edn (Cambridge: Polity, 2012), vi.

-

[18]

Ibid.

-

[19]

Emma Maguire, “My Inner Fangirl,” Kill Your Darlings 26 (2016): 79.

-

[20]

Ibid.

-

[21]

Kathryn Perkins, “The Boundaries of BookTube,” The Serials Librarian 73, no. 3-4 (2017): 352.

-

[22]

Ted Striphas, The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture from Consumerism to Control (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 101.

-

[23]

Son Vivienne, “‘I will not hate myself because you cannot accept me’: Problematizing Empowerment and Gender-Diverse Selfies,” Popular Communication 15, no. 2 (2017): 126–40; Edgar Gómez Cruz and Helen Thornham, “Selfies Beyond Self-Representation: The (Theoretical) F(r)ictions of a Practice,” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 7, no. 1 (2015): 1–10.

-

[24]

Gómez Cruz and Thornham, “Selfies Beyond Self-Representation,” 3.

-

[25]

Tim Highfield and Tama Leaver, “Instagrammatics and Digital Methods: Studying Visual Social Media, from Selfies and GIFs to Memes and Emoji,” Communication Research and Practice 2, no. 1 (2016): 47–62.

-

[26]

Information obtained from AustLit, August 31, 2018.

-

[27]

Australian slang for a chain of charity shops run by The Salvation Army.

-

[28]

Todd Graham and Scott Wright, “Discursive Equality and Everyday Talk Online: The Impact of ‘Superparticipants,’” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19, no. 3 (2013): 625–42.

-

[29]

Fletcher, Driscoll, and Wilkins, “Genre Worlds and Popular Fiction,” 997–98.

-

[30]

“Tip” is the Australian term for garbage dump. A secondhand store attached to a waste management centre is known as a “tip shop.”

-

[31]

Flesch, From Australia with Love, 43–44.

-

[32]

Brian Thill, Waste (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 8.

Bibliography

- Carter, David. “General Fiction, Genre Fiction and Literary Fiction Publishing, 2000-13.” In The Return of Print? Contemporary Australian Publishing, edited by Aaron Mannion and Emmett Stinson, 1–26. Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2016.

- Curthoys, Ann, and John Docker. “Popular Romance in the Postmodern Age and an Unknown Australian Author.” Continuum 4, no. 1 (1990): 22–36.

- Dixon, Jay. The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon, 1909-1990s. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Driscoll, Beth, Lisa Fletcher, and Kim Wilkins. “Women, Akubras and Ereaders: Romance Fiction and Australian Publishing.” In The Return of Print? Contemporary Australian Publishing, edited by Aaron Mannion and Emmett Stinson, 67–87. Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2016.

- Driscoll, Beth, Lisa Fletcher, Kim Wilkins, and David Carter. “The Publishing Ecosystems of Contemporary Australian Genre Fiction.” Creative Industries Journal 11, no. 2 (2018): 203–221.

- Elam, Diane. Romancing the Postmodern. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Flesch, Juliet. From Australia with Love: A History of Modern Australian Popular Romance Novels. Fremantle: Curtin University Books, 2004.

- Fletcher, Lisa, Beth Driscoll, and Kim Wilkins. “Genre Worlds and Popular Fiction: The Case of Twenty-First-Century Australian Romance.” The Journal of Popular Culture 51, no. 4 (2018): 997–1015.

- Gómez Cruz, Edgar, and Helen Thornham. “Selfies Beyond Self-Representation: The (Theoretical) F(r)ictions of a Practice.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 7, no. 1 (2015): 1–10.

- Graham, Todd, and Scott Wright. “Discursive Equality and Everyday Talk Online: The Impact of ‘Superparticipants.’” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19, no. 3 (2013): 625–42.

- Grescoe, Paul. The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance. Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 1996.

- Highfield, Tim, and Tama Leaver. “Instagrammatics and Digital Methods: Studying Visual Social Media, from Selfies and GIFs to Memes and Emoji.” Communication Research and Practice 2, no. 1 (2016): 47–62.

- Jameson, Bronwyn. In Bed with the Boss’s Daughter (duo edition with Ashley Summers, Beauty in His Bedroom). Chatswood: Harlequin Mills & Boon, 2001.

- McAleer, Joseph. Passion’s Fortune: The Story of Mills & Boon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- McAlister, Jodi. “Bachelor Nation: The Construction of Romantic Love and Audience Investment in The Bachelor/ette in Australia and the United States.” Participations, 15, no. 2 (2018): 343–64.

- McWilliam, Kelly. “Romance in Foreign Accents: Harlequin-Mills & Boon in Australia.” Continuum 23, no. 2 (2009): 137–45.

- Maguire, Emma. “My Inner Fangirl.” Kill Your Darlings 26 (2016): 72–82.

- Modleski, Tania. Loving with a Vengeance: Mass-Produced Fantasies for Women. Hamden: Archon, 1982.

- Perkins, Kathryn. “The Boundaries of BookTube.” The Serials Librarian 73, no. 3-4 (2017): 352–56.

- Radway, Janice. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. London: Verso, 1994.

- Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

- Roach, Catherine M. Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016.

- Selinger, Eric Murphy, and William A. Gleason. “Introduction: Love as the Practice of Freedom?” In Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love as the Practice of Freedom?, edited by William A. Gleason and Eric Murphy Selinger, 1–21. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

- Striphas, Ted. The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture from Consumerism to Control. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

- Tapper, Olivia. “Romance and Innovation in Twenty-First-Century Publishing.” Publishing Research Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2014): 249–59.

- Thill, Brian. Waste. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

- Thompson, John B. Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Polity, 2012.

- Thurston, Carol. The Romance Revolution: Erotic Novels for Women and a Quest for a New Sexual Identity. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

- Veros, Vassiliki. “A Matter of Meta: Category Romance Fiction and the Interplay of Paratext and Library Metadata.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies 5, no. 1 (2015): http://jprstudies.org/2015/08/a-matter-of-meta-category-romance-fiction-and-the-interplay-of-paratext-and-library-metadataby-vassiliki-veros/.

- Vivanco, Laura. For Love and Money: The Literary Art of the Harlequin Mills & Boon Romance. Penrith UK: Humanities-Ebooks, 2011.

- Vivienne, Son. “‘I will not hate myself because you cannot accept me’: Problematizing Empowerment and Gender-Diverse Selfies.” Popular Communication 15, no. 2 (2017): 126–40.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Prince of Scandal: Harlequin “Presents” 2011 North American edition in a personal collection (L) and Harlequin “Jessica” 2014 edition at Marrickville Library, New South Wales (R).

Ex-library copies of A Faulkner Possession and The Hot-Blooded Groom on the category romance shelf at a Sydney charity store (L) and Cruise Control, in a basket of books to be “reread” (R).

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Do Not Disturb and The Socialite’s Secret in romance trolleys at The Cog, a bookstore/cafe in Traralgon, Victoria (L), and Desert Mistress, Suddenly Single Sophie, The Costarella Conquest, and A Mother for His Baby in the category romance area at Wollondilly Library, Picton, New South Wales (R).

Figure 10

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Titles in 0 - 7 shelfies