Résumés

Abstract

The book festival provides an intriguing instance of the overlapping cultural, social and economic dimensions of contemporary literary culture. This article proposes the application of a new conceptual framework, that of game-inspired thinking, to the study of book festivals. Game-inspired thinking uses games as metaphors that concentrate and exaggerate aspects of cultural phenomena in order to produce new knowledge about their operations. It is also an arts-informed methodology that offers a mid-level perspective between empirical case studies and abstract models. As a method, our Bookfestivalopoly and other games focus attention on the material, social and ideological dimensions of book festivals. In particular, they confirm the presence of neoliberal pressures and neocolonial inequalities in the “world republic of letters.” Our research thus makes a contribution to knowledge about the role of festivals within contemporary literary culture, and provides a model for researchers of cultural phenomena who may want to adopt game-inspired, arts-informed thinking as an alternative to traditional disciplinary methods.

Résumé

Le festival du livre constitue un exemple intéressant quant à la manière dont les dimensions culturelle, sociale et économique se chevauchent dans la culture littéraire contemporaine. Le présent article propose l’application d’un nouveau cadre conceptuel à l’étude des festivals du livre, celui de la réflexion inspirée par le jeu. Dans cette dernière, les jeux agissent comme des métaphores qui concentrent et exagèrent certains aspects de phénomènes culturels afin de produire un savoir inédit sur leurs mécanismes. Il s’agit aussi d’une méthodologie nourrie par les arts et qui offre une perspective à mi-chemin entre études de cas empiriques et modèles abstraits. Ainsi, notre « Bookfestivalopoly » (littéralement : Festivaldulivropoly) et les autres jeux dont nous nous inspirons ramènent l’attention sur les dimensions matérielle, sociale et idéologique des festivals du livre. Plus particulièrement, ils confirment la présence de pressions néolibérales et d’iniquités néocoloniales à l'oeuvre dans « la république mondiale des lettres ». Nous souhaitons, par nos travaux, contribuer à la connaissance du rôle des festivals au sein de la culture littéraire contemporaine et soumettre un nouveau modèle aux chercheurs qui s'intéressent aux phénomènes culturels et aimeraient adopter une approche inspirée par le jeu et les arts plutôt que les approches disciplinaires habituelles.

Corps de l’article

The rise of the book festival in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries has provided scholars with a rich opportunity to study the overlapping cultural, social and economic dimensions of contemporary literary culture. As events that bring together authors and readers, book festivals have origins that stretch backwards to live literary events held in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[2] The rise of the book festival itself can be traced to the immediate post-war period in the UK, and the establishment of the Cheltenham Literature Festival in 1949. The same year, the Edinburgh Festival (of Music and Drama) was inaugurated, and an International Writers’ Conference joined the cultural billing in 1962, with a regularly held festival from 1983 onwards.[3] In Australia, the Adelaide Writers’ Week was inaugurated in 1960; in Canada, the Toronto International Festival of Authors began in 1980.[4] Since then, festivals have proliferated to become highly visible features of contemporary book culture, with media discourse frequently presenting them as a location for considered public discussion and political debate, a liberal arena where bookishness reigns. As a British newspaper blithely notes of the Hay Festival, “it doesn’t really matter where it takes place; Hay is about conversation, ideas, thoughts large and small.”[5] For authors, opportunities for increased sales and prestige can be offset by anxiety about public exposure. Their accounts of festivals range in tone from rueful, to acerbic, to entertaining.[6]

As scholarly research objects, literary festivals are complex events that lend themselves to interdisciplinary approaches and experimental methodologies. Research on literary festivals has often adopted a cultural sociology approach influenced by Pierre Bourdieu’s model of the field of literary production.[7] Such research conceptualises the book festival as a site that, in Millicent Weber’s words, “signifies and actively reproduces the tensions and debates in the literary field more broadly.”[8] These tensions include the interplay of cultural and economic capital, especially through an intensification of the meet-the-author culture that characterises contemporary book marketing.[9]

Bourdieu’s model has been extended by researchers looking to account for the complexity of book festivals. Beth Driscoll has argued that festivals belong to the middlebrow, a cultural formation under-theorised by Bourdieu, due to their combination of art and commerce, mediated events, and predominantly middle-class female audiences.[10] Festivals also increase the porosity of the borders of the literary field by facilitating interaction between the book trade and adjacent media fields, while their digital manifestations increasingly complicate a Bourdieusian model of the literary field.[11]

The international circuit of book festivals demands an extension of Bourdieu’s model to account for an uneven global distribution of prestige and access to resources, which recalls Pascale Casanova’s account of the “world republic of letters.”[12] There is a dramatic difference between festivals at the centre and the peripheries of global literary culture, and the study of book festivals can be positioned within a broad line of thinking about international power relations and the ongoing legacy of colonialism.[13] Sarah Brouillette’s critique of the “African literary hustle,” for example, includes book festivals as part of what she terms the “NGOization” of African literature, which, she argues, does nothing to support infrastructural development and readerships in Africa, but rather is built by a “transnational coterie” of actors (including event organisers) who aim their production at British and American markets.[14] Neocolonial routes to literary recognition for writers from the developing worlds via metropolitan centres include book festivals, adding them to a set of consecrating—and, as Huggan argues, exoticising—activities such as literary prizes.[15]

Broadly sociological accounts make up the bulk of current research into book festivals. A second, often complementary, conceptual framework has come from cultural industries research. Festivals are features of several cultural spheres, and book festivals are linked to, and can be interpreted as part of, a broader creative economy.[16] Scholarship of the festivalisation of culture has emphasised aspects of branding and place marketing, focusing on the production of economic value and the development of place-based cultural tourism.[17]Negotiating Value in the Creative Industries: Fairs, Festivals and Competitive Events, for example, includes work that draws on organizational theory and Appadurai’s “tournaments of value” to conceptualise the multifaceted role of cultural festivals, and Festivals and the Cultural Public Sphere takes a range of social-scientific approaches to examine the role of cultural festivals in the formation of social and political collective identities.[18]

Cultural industries frameworks also provide one of the main lines of critique of book festivals. The co-option of creative activity to the economy, from Richard Florida onwards, has been critiqued as a neoliberal turn, in which “true creativity is indivisible from marketability.”[19] This is particularly evident in the creative economy imperative to quantify culture. In the realm of festivals, this narrative reached its apex in Edinburgh’s Thundering Hooves report, subtitled “Maintaining the Global Competitive Edge of Edinburgh’s Festivals.”[20] The report, which notes the contribution that summer festivals, including the book festival, make to the economy (£184 million revenue and 2.5 million visitors in 2004), focuses on how the city’s festivals can retain their competitive edge, commenting that “as in many areas of global competition, second or third place—‘silver’ or ‘bronze’ rather than ‘gold’—represents a position that is considerably inferior to that of pre-eminence.”[21] The language of competition underpins much contemporary cultural policy towards festivals and operates alongside the quantification of cultural value. This is a dynamic noted in sociological research, too; the quantification of culture is an implicit feature of the Bourdieusian model, in which even symbolic capital is distributed across a field and accrued by agents. In creative economy frameworks, this quantification is explicit and intensified.

These two conceptual frameworks—cultural sociology and creative economy studies—have emerged as the dominant ways of approaching book festivals. Within and alongside these frameworks, researchers of book festivals employ multiple methods. Primary qualitative and quantitative research on audiences and organisers has included surveys, interviews, participant observation, analysis of blogs, and social media scraping.[22] Ethnography and autoethnography, including “thick” descriptions of events incorporating techniques of creative writing, explore the texture and nuance of live literature.[23] Archival research has underpinned longer-lived events.[24] One academic/practitioner partnership has prototyped a qualitative digital evaluation tool for measuring cultural events and their impact on audiences.[25]

Despite the interdisciplinary and mixed research methods approach to book festivals, there is a heavy reliance upon case studies as the unit of analysis, and a consequent need to consider how different methods can fit together to produce a model of how they operate. In this article, we propose a new approach: game-inspired thinking. Game-inspired thinking opens up a space between individual case studies and abstract theories to offer a mid-level perspective. Our research thus contributes to recent debates in the humanities about scale and methods: terms such as close, surface and distant reading, cultural analytics and mid-level concepts indicate some of the ways in which scholars have taken up the epistemological challenge of advancing knowledge of cultural texts and phenomena.[26] Game-inspired thinking offers an alternative route through this terrain, one that is deliberately playful and creative, an arts-informed complement to methodological empiricism.

Games as Method for Book Culture Research

“I’ve been meaning to go to the Ullapool Book Festival, which everyone raves about way up north.”[27]

Our route to game-inspired thinking began with a road trip to the 2016 Ullapool Book Festival, a small but highly-regarded event held on the edge of Scotland’s dramatic north-west coast. As tourists and researchers of book culture, we were intrigued by the social and cultural dynamics of this festival—its air of conviviality, connection with the local community, and extended networks including Atlantic Canadian writers. The format of the event was similar to that of many other book festivals, but we also recognised this festival’s irreducible specificity. We were challenged to reflect on how this could be accounted for through existing methodologies. Is it possible to research a book festival without treating it as yet another case study, fodder for an ideological critique, or a gossipy, impressionistic travelogue?

Figure 1

In a spirit of experimentation, we began by drawing a rough map of the festival location. Its board game-like appearance led us to consider the idea of different players and roles within literary festivals, such as organisers, authors, event chairs, local and visiting readers, and bookshop owners. We thought about the aims of each player, and the risks they might encounter. A different approach to the analysis of a book festival began to emerge.

“Game-inspired approaches,” a term proposed by Nina Belojevic et al. to cover a broader array of work than games or gamification studies, is appropriate for our research, which does not set out to address existing games theory.[28] Rather, our work is informed by our training in literary and publishing studies, and situated in the tradition of book history and its consideration of the industrial, economic and cultural processes affecting the production, circulation and reception of books. Game-inspired thinking appeals to us because it offers a creative extension of our research, one that makes use of the specifically literary concept of metaphor.

One of the key features of metaphor is that it enables lateral thinking. As Rita Felski puts it,

The fortunes of metaphor have soared in recent years; no longer just a decorative device or a baroque frill, it is acknowledged as an indispensable tool of thought. Metaphor, after all, is a matter of thinking of something in terms of something else—the basis for any kind of comparative or analogical thinking. Binding together the disparate and disconnected, it opens up fresh ways of thinking and seeing.[29]

The metaphor of the game is already present as a “tool of thought” in theories of book culture. For Bourdieu, the field of cultural production is (among other things) a playing field in which agents compete for different forms of capital. Each agent in the field has a habitus that constitutes their “feel for the game”, and uses strategies “associated with the positions which they occupy in the structure of a very specific game.”[30] The field as a whole is governed by established ideas including the illusio “that the game . . . is worth being played, being taken seriously.”[31] Following in the Bourdieusian tradition, James English analyses literary prizes using the metaphor of games and refers to “the strategic uses of celebrity in the contemporary literary ‘game’,” while Weber concludes her monograph on festivals with a chapter titled “The Rules of the Game.”[32] Casanova refers to “contestants in the game of letters,” some with more prestige than others.[33]

In these scholarly accounts, the metaphor of the game is an analytical tool to explain behaviour. But there is another way to use metaphors, and indeed to use games. The analogies that metaphors make are often most powerful when they are surprising—when they make an unexpected leap to a tangential association. In this, metaphors are creative, and are embedded in many artistic practices. Our use of games as metaphorical models of festival behaviour draws on this potentiality, and can be considered as an instance of arts-informed research. Arts-informed research is an alternative to traditional academic frameworks because it uses creative processes to augment analytical work.[34] Ardra L. Cole and J. Gary Knowles set out its key features, which begin with a commitment to an art form—taken broadly in our case to include games. The inherent sociability of games enables us to meet another element of arts-informed research, the reflexive presence of the researcher in the research. Meanwhile, the playfulness of games supports a third feature, an expansiveness to the possibilities of the human imagination.[35]

Arts-informed research practitioners also need to justify why their chosen art form achieves the research purpose.[36] We selected games specifically for their manifold metaphorical potential. Games draw much of their illuminative power from their simplified and therefore exaggerated abstract forms. In this, they operate somewhat like a diagram, a more familiar tool for academics. Book historians, for example, have long been influenced by Robert Darnton’s “communications circuit,” a diagram that traces the path taken by a book from publisher to printer to bookseller to reader.[37] This diagram transforms the messy simultaneity of book-related processes into an orderly sequence reminiscent of a board game. Unlike a game, however, a diagram cannot be played, although it can be adapted and playfully reconfigured, as Ray Murray and Squires and @RobotDarnton have done for Darnton’s model.[38]

Figure 2

All research can be responded to through traditional modes of scholarly communication, but games proactively invite such interaction. Games are inclusive, building on participants’ knowledge through shared experiences and iterative testing. We focus on traditional card and board games, rather than digital or video formats, in order to activate attitudes people hold towards them. In Felski’s phrase, “metaphors are orientation devices that yoke abstract ideas to more tangible or graspable phenomena, intertwining the less familiar with the already known.”[39] Physical games can be handled, played with, responded to, and compared to other familiar games. Such material actions put pressure on and extend metaphorical language as a tool for researching book festivals. We thus take the game as a metaphor that can concentrate and exaggerate aspects of book festivals in order to produce new knowledge about their operation.

Figure 3

Furthermore, the material objects we create and the physical actions of drawing on flip-chart paper, cutting out and colouring in, placing tokens on a board, and rolling dice, can inspire a meditative, reflective state—a kind of “slow academia” that counters the imperative for “high productivity in compressed time frames” encountered in contemporary universities. [40] They can thereby lead to new perspectives on research questions. As material metaphors, we want to invite players to see them as works in progress to which they can contribute. Rather than creating a slick aesthetic that presents the games as potential commercial products, we emphasise their status as tools for research. Our aesthetic is deliberately amateurish, in order to inculcate a more playful engagement than the professionalism of both academic and book culture.[41]

The choice of card and board games is also meant, for ourselves and our respondents, to lower inhibitions and tap into a wellspring of creativity. The sociality of game design and play draws a wider than usual range of participants and collaborators into new forms of interaction. We recognise with Felski that metaphors can “prime us to adopt certain attitudes,” and in the case of games, playful competitiveness (and its nostalgic reminders of childhood rivalries and interactions) becomes part of the research.[42] We wanted to reframe the social patterns of academia through ludic explorations that can disarm participants, and potentially reframe, and even subvert, approaches to book culture studies. Our game-inspired thinking, then, is arts-informed research that harnesses the creative power of metaphor and the iterative, social qualities of games in order to generate new knowledge about book festivals.

Figure 4

We designed three card and board games, with each foregrounding a specific perspective on contemporary book festivals: that of the reader, the festival organiser, and the writer. The first experiment follows the journey of a reader mapped onto the geographical structure of a festival in a simple Snakes and Ladders-style race game, illustrated in Figure 4. A series of gains and pitfalls are encountered as the reader moves from box office, to author sessions, to the book-signing queue, and on to the closing party. As we created these, we discussed what makes a good or bad festival for readers, drawing on autoethnographic experiences, our earlier primary research, and accounts from scholarly literature, newspapers, blogs, and social media. Gains include being followed by the festival on Twitter, being given a ticket to a sold-out event, and being invited to join an author for a glass of wine. Pitfalls include arriving late and not being admitted, hearing your phone ring during a poetry performance, and overhearing a favourite author complain about audiences.

As we created the game, we saw that we were making the gains and pitfalls extreme. Games exaggerate, we discovered, for the sake of jeopardy and, indeed, satire. This was enjoyable, but not entirely true to life: a reader goes to a festival for a day out, to meet friends, to hear from authors, but ends up in a race for the finish line? Perhaps not. We also found that it was hard to capture the “literary” experience of being at a book festival—the content of festival events, the textual rather than the contextual. Our first attempt, then, was an intriguing and illuminating failure as a game and as a metaphorical model of book festivals.

Book Festival Trumps

Our second game, an adaptation of Top Trumps, is focalised through the perspective of festival organisers. Top Trumps is a simple card game in which players compete each round to have the highest score in a nominated category. The scores may be derived from existing quantitative measures (for example, height and weight in a cat-themed version), or may be a more qualitative attribute which is given a numerical score (for example, intelligence). The emphasis on quantification and ranking in Top Trumps makes this game an intriguing metaphor for the cultural industries frameworks in which festival organisers operate.

In our adaptation, each card is an individual festival, scored in each of six categories: Attendance; Prestige; Location; Programming; Twitter Followers and a USP (or Unique Selling Point).

Figure 5

The process of quantifying these complex cultural phenomena for the cards felt counter-intuitive, and yet also familiar from our scholarly and cultural engagements. Two categories were already quantitative. A snapshot of each festival’s Twitter followers was taken on one day, as an indicator of a festival’s digital engagement. Attendance figures were sourced from annual reports, media articles, and directly from the organisers. The category should have been straightforward, but we encountered issues with finding and verifying figures. This lack of transparency and clarity may be related not only to various ways audiences can be counted, but also to the role of attendance figures in measuring a festival’s failure or success.

The remaining categories were scored out of 10 based on our existing knowledge of the festivals and examination of their websites, programs, media articles and blogs. Prestige was initially a difficult category to score. Although crucial to festivals, it is intriguingly unsettled, both vague and relative. After discussion, we decided to score Prestige by looking at how many high profile authors were featured on each program, as this is often how festivals make their claims for status. It then became disconcertingly easy to rank the Prestige of festivals: an Anglophone Nobel Prize winner easily outscores a local mid-list writer.

Programming became a category that balanced the star power of Prestige. Literary celebrities can feel like “the usual suspects,” and we are sensitive to (and even bored by) repetition in the festival circuit. The programming score was based on the creativity of a festival’s recent programs, which might mean unexpected mixes of authors (including culturally and linguistically diverse), innovative formats, unconventional venues, and attempts to reach out to communities beyond the archetypical middle-class audience member. We scored highly for the newness and surprises that we enjoy about festivals, whether it is slam poetry outside a taco truck in Texas or an unusual panel combination of Welsh and French TV screenwriters in Birmingham.

The two final categories aimed to capture the specific charms of each festival. Location was scored on the allure of the city or town in which the festival was based, thereby referencing cultural placemaking and tourism. Finally, we created a USP for each festival to account for one or two of their unique features. The USP had both a score and a descriptive phrase: for example, crime festival Bloody Scotland’s USP is its “writers’ football match.” The USP was an enjoyable category to research because it allowed us to consider our personal interests in varied cultural experiences; this also, however, meant the scores felt very subjective.

Figure 6

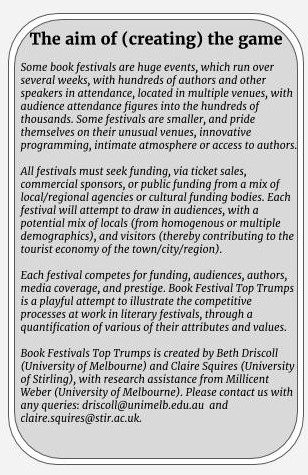

After compiling the scores into a spreadsheet, we created a set of cards which included an instruction card that explained the aim of (creating) the game (Figure 6). We played the game with a number of groups, including authors, academics (from the disciplines of book history, publishing studies, cultural and media studies), publishers, and publishing students.

Playing the game was generally enjoyable, with players taking particular delight in the card objects. However, in terms of generating discussion, rounds of Book Festival Trumps were often pure, decontextualized quantitative play, in which players focused on the numbers without paying attention to other textual and pictorial detail on the cards. Discussion, prized by us as humanities researchers, was often absent, particularly when the nominated category was Attendance or Twitter followers. In other cases, discussion was heated. For example, students at the University of Stirling noted that Glasgow had been given a higher location score than Edinburgh—an indicator of Claire’s prejudices—and then added their own voices to the debate over the rivalrous Scottish cities.

The insights gleaned through design and play of Book Festival Trumps are further discussed below, but we became aware that this particular metaphorical model for understanding book festivals has limitations. The rigid, compressed format of the card means that many dimensions of book festivals were excluded, and the set became polarised into strong and weak cards, creating an extremely uneven playing field that does not accord with our understanding of festivals. So we turned to a more complex game model, with expanded metaphoric potential.

Bookfestivalopoly

Our third game is an adaptation of Monopoly, a game that already functions somewhat metaphorically as an engagement with and critique of capitalism.[43] The board depicts a series of properties with rising price values. Players navigate the board using dice, buying and developing properties, paying fees when they land on other players’ properties, and taking Chance and Community Chest cards, which advance or slow their interests. The aim of the game is for players to bankrupt each other.

Monopoly is a complicated game with several distinct stages that takes a long time to play. It is also familiar; many people remember playing Monopoly with family and friends, often with “house rules.” People are accustomed to seeing Monopoly’s key game features reworked to make new connections in its numerous official (regional, transmedia, fast-food, etc.) adaptions, a process that we extended in our research as we adapted the game.

It was an intriguing challenge to adapt Monopoly to account for cultural as well as economic transactions, and Bookfestivalopoly is our most intricate metaphorical work. Our adaptation models a year in the promotional life of a book, with players taking the role of authors who aim to earn a living wage. We wanted to explore how festivals publicise books and provide authors with income through performance fees, and how festivals contribute to broader symbolic economies. Taking a subset of cards from Book Festival Trumps, we allocated festivals to the board, recognising the uneven distribution of prestige by spiralling up to the largest UK festivals as the epicentre of power and legitimacy. Our equivalents of the highest value properties are the Hay Festival and the Edinburgh International Book Festival. The lower value cards are festivals in what Casanova would consider peripheral national literary cultures and festivals, which also target niche genres, such as Iceland Noir and Versoteque Festival of Poetry and Wine (Slovenia).

Figure 7

The Bookfestivalopoly board, demonstrating an unpolished aesthetic, and the 3D-printed writers’ tokens.

The equivalent of jail was “being ignored” (a calamity for writers trying to promote a book). The utilities became newspapers and social media. The equivalent of houses and hotels was being a regular speaker, then keynote at a festival (denoted by books and bookcases). Train stations were recast as “stations on the way to riches,” major events in a writer’s career such as winning the Man Booker Prize or becoming a Creative Writing Professor. “Go” became annual royalty payments. “Free Parking” was recast as the Green Room, a square that prompted strong responses during game play. One player (a writer) said that she avoided green rooms because of their elitism, while another reflected on the increasing separation between readers and writers over the years. A third player, provoked by our Green Room square with its promise of canapés and bookish chat, interrogated the value of festivals: how much do they really contribute to book sales and an author’s visibility, and how much are they to do with the book world liking to gather, gossip and drink wine?

Figure 8

Other game features also generated discussion. The “Chance” and renamed “Communal Cultural Wealth” cards presented scenarios based on our knowledge of the good and bad events that can happen to authors at festivals, including those derived from authorial accounts. These cards—particularly “An audience member asks a question that turns out to be a 25 minute comment. Go back three spaces”—triggered recognition of experiences at events. One player, who received a card about an overbearing male chairperson, thought there should be more gendered disadvantage structured into the game.

Figure 9

We made adjustments to the rules to tease out the economic reality of festivals. In Bookfestivalopoly, no player pays money to any other—everyone gets paid by the bank, redesignated as “the market.” This competitive structure more accurately reflects the dynamic of festivals. Although aspects of book culture may be a zero-sum game (some writers do not secure a publisher, or do not get invited to festivals at all), more often competition in book festivals is experienced as a graduated system of inequality: an A list and a B (C, D...) list. Players then reflected on the economic effects of this system: prestigious events with derisory pay, and the gap between payments offered to emerging and celebrity writers. Players often laughed on receipt of a miniscule amount (e.g. $6) for a festival performance fee.

Inspired by Bourdieu, we also altered the game dynamics by introducing a second currency of cultural capital. Each player has a “Critical Acclaim Loyalty Card” and earns one point at each festival they visit. “Stations on the way to riches” are paid for with these points, so that a player cannot win the Man Booker Prize, for example, without sufficient accrued critical acclaim. These stations also provide royalty boosts for authors. Critical Acclaim points therefore have exchangeable value, but like a store loyalty card, their direct financial equivalence is negligible. The loyalty cards generated much discussion. It was a poignant experience to land on the Man Booker Prize square and not have enough critical acclaim points to redeem it. The metaphor here was strong: to feel eligible for a prize but to not yet have acquired the cultural credibility to claim it.

Rebellious game play introduced fluid, non-rigid approaches to challenge conversions between economic and cultural capital. For example, during one game played between the two of us, there was considerable storytelling about the kind of writerly careers evoked by different game events; while Beth’s writer had initial success amassing critical acclaim and literary prizes, her career stalled and she was left behind by the commercial success of Claire’s writer. We invented impromptu house rules that ameliorated this inequality. Claire’s writer donated some of her cash to “endow” Beth’s writer with a Chair as Creative Writing Professor. This is one example of how game play, despite or because of its constraints, allows players the freedom to imagine different rules and modes of behaviour, including novel ways of combining the economic and cultural dimensions of a literary life.

Games, Book Festivals and Materiality

These three games—Bookfestivalopoly, Book Festival Trumps and the race game—form the core of our arts-informed investigation into contemporary literary festivals. Each stage of the iterative process of designing and testing these games offered opportunities to think creatively about games as metaphors for book festivals. In the following analysis, we aggregate the feedback from our testers as well as our own observations on the design process. Our key findings fall into three categories: reflections on the games’ materiality and their intersections with digital technology; insights into the social dynamics of the research process; and an interrogation (and partial confirmation) of key arguments about the neoliberal and neocolonial aspects of book festivals.

The tactile materiality of our games enabled thinking through action, drawing on slow scholarship as well as arts-informed approaches. Players interact physically with cards and tokens as they gather face-to-face, creating opportunities for reflection and discussion. This reflective, open method is highly appropriate for investigation of an emergent, dynamic and complex cultural phenomenon such as book festivals, and the deliberate materiality of our games prompted several learning moments.

Material objects are charming. The Book Festival Trumps cards are miniature expressions of festivals, able to be held in the hand or tucked into a pocket. The Bookfestivalopoly writing-related tokens, which include a 3-D printed miniature quill, laptop, and bookcases, caused particular delight. The pleasure of holding these objects can also inspire an acquisitive impulse. Book Festival Trump cards are instantly collectible, making manifest the way in which book festival experiences can also be accumulated. Similarly, the tangibility of the Bookfestivalopoly property cards fosters a desire to “acquire” festivals, to gather together mismatched festivals, or trade with others to build themed sets. These material game elements thus provoked discussion about some players’ motivations for attending festivals, such as the serendipity of adding festival visits on to other travel plans, or the aspiration to visit a particular set of festivals.

In addition to their own materiality, our games reference and evoke the physical space of book festivals. Our early map of Ullapool Book Festival and the race game taught us some lessons in terms of how we might try to understand the experience of a reader traversing festival spaces, linking to our abiding autoethnographic interest in attending festivals in different locations. The process of scoring locations for Book Festival Trumps made us discuss the impact of the geographical setting of a festival on its appeal. This led into a broader discussion, extended by Bookfestivalopoly, about the way physical location interacts with reputation and economic structures, discussed further below.

Materiality and physicality are, deliberately, key components of our arts-informed research. Yet even though our games are traditional card and board games, our work is firmly embedded in the digital era. As transnational research partners, we are reliant on digital communication technologies, from Skype and Facebook messenger to Google Docs and emails. To create the games, work done on one continent was digitally transmitted and materially reconstructed on another. Game playing sessions were also often discussed on social media, where we encouraged the use of the #bookishgames hashtag. This combination of physical and virtually-mediated experiences mirrors book festivals themselves. Festivals increasingly engage in online spaces alongside their live events; this can create enriching experiences for readers and writers, but can also sometimes produce unease.[44] Code-switching is required to move between physical and digital modes, and some organisers, writers and readers are more comfortable with print than digital. Our research project, both in terms of its object and its methods, explores technological comfort and discomfort, sensations of unease at the transmission of material objects into the digital realm, and the joy of digital connections. In this, our game-inspired thinking points to the enduring materiality of print culture, its enmeshment with the digital, and the possibilities these formats provide.

The Sociality of Games

One of the levels on which games work as metaphors for book festivals is that both are social. Comparing these different forms of sociality within the frame of academic research—itself a professionalised mode of sociality—provides valuable insights into how interpersonal dynamics can shape understanding of cultural events.

As noted earlier, the sociality of games shifts the role of the academic by opening book culture studies up to collaborative and interactive processes. At several stages throughout prototyping, we asked people to test our games. The premise was that inviting fellow researchers, students and practitioners to engage playfully with ideas about festivals would reframe their, and our, approaches to book cultures. This turned out to be the case as players actively entered into discussion about book festivals as they played. As noted above, the design and play experience of our adaptation provoked reminiscences, so that the game operated as an elicitation technique for generating new knowledge. Sometimes this produced recognition and shared laughter; sometimes tensions arose (as in the example above of a player whose reaction to the Green Room was an interrogation of the value of festivals). This articulation of dissent is an important part of our process, invited by our design decisions. For example, we allowed our personal investments in location to be visible in the form and scoring of the games in order to provoke discussion. Disagreements were highly valuable in exposing some of the frictions that underlie a prevalent mode in contemporary book cultures, where mannerly behaviour and agreeable sociability are exhibited, and competition and inequality are elided. Our research suggests that disputation about game design, along with the other humorous, cheeky, interrogative and ruminative conversations that occur in a playfully competitive environment, is an illuminating discursive mode for understanding book festivals.

Another form of disagreement arose from the intersection of games-sociality and academic-sociality. Some academic players did not see the point of the games, or to be more precise did not see them as research; others were delighted by the games but saw them as unusual within universities. Because game-inspired thinking is a tangential, associative, indirect form of knowledge creation, it resists and runs counter to the output-driven, economically-oriented model of academia in operation in our two countries. The unusualness of our research, the way it veers away from conventional scholarly modes and formats, is part of its point. Our collaborative, playful method is critical because it actively counters reductive thinking—not only about festivals, but also about what research can be.

The sociality of game-inspired thinking refracts the already social aspects of established research processes. The iterative nature of game design means that the conversations it prompts are ongoing and collaborative, a less formal version of the feedback mechanisms in larger academic structures of knowledge, such as conference presentations and peer review.[45] Game-inspired thinking also exposes some of the power relations that endure. For example, despite our aim for a de-centred role for ourselves as researchers, many testers expected us to know the rules and interpret the game for them. We are also aware of the particular audiences we played with, and their relationship to our arguments about distributed knowledge: many of our testers were “in the know” about festivals as writers or academics, while others, including our students, knew less. Who plays the game matters, in terms of the discussion. One player, for example, suggested inviting festival directors to play the game in order to help them strategically think through the values they wished to focus on in their festival, and how rival festivals pitch themselves. Doing this would be a way to generate a new set of insights, and may be an avenue for future impact-related research.

All of these conversations, and the inclusion of them in our research design, point to the possibilities for critical reflection and engaged participation offered by games as a method for book culture studies and practice. Each player contributes to the findings in game-inspired research. At the same time, we recognise that not everyone may feel equally able to contribute to play-based discussions, and acknowledge that our own positions as academic staff in the developed world, with more secure employment than some of our early career colleagues, mean that for us playfulness is less risky, if still inhabitual.[46]

The Neoliberal, Neocolonial Book Festival?

Two of the strongest critiques of book festivals are, first, that they are neoliberal, money-making operations that participate in the instrumentalisation of culture, and second, that they perpetuate neocolonial power structures that work to the disadvantage of non-Anglophone, peripheral literary cultures. Our arts-informed research to some extent supports these claims. Our games make evident in a striking way the neoliberal economic frameworks in which festivals (and academics) participate. Games may be playful, but their representational design and structured, competitive play can effectively depict instrumental processes.[47]

Book Festival Trumps is an exercise in experiencing the pressure to quantify culture. Numbers are proxies for other kinds of value. Twitter followers, for example, stand in for digital engagement, and the close fit here reinforces the amenability of social media to algorithmic, quantified understandings of connection. Numerical scores also transmit criticisms of individual festivals. Our decisive opinions on the Programming category, for example, highlight our own habituation to ranking cultural phenomena via their degree of established practice and innovation. Once chosen, these numbers have force. During game play, we were struck by the rounds of Book Festival Trumps that generated no discussion beyond announcement of numbers. This discursive absence demonstrates the power and authority of quantitative measurement. The tendency to accept numbers on their own terms is a phenomenon with which festival organisers must contend as they try to gain funding and support.

In general, for Book Festival Trumps, the playfulness of the game belies a very competitive process. Put simply, the game asks a seemingly perverse question: “what does it mean to win,” as a book festival? Do literary festivals ever really come head-to-head? But as our instructional “Aim of (creating) the game” (see Figure 6) card explains, they do. Festivals compete, on uneven ground, for funding, audiences, authors, media coverage, and prestige. Book Festival Trumps makes overt a hierarchy of festivals and forced a quantification of cultural value, a process that is often disconcertingly easy.

And yet numbers are also always problematic. The difficulty that we encountered in accounting for Attendance—the slipperiness of this apparently straightforward metric—is one example. In other Book Festival Trumps categories, players showed a striking resistance to quantification, querying how we arrived at the Prestige, Programming and Location scores, and articulating their own affiliations and prejudices. Such debates are manifestations of the enduring difficulty of measuring cultural value, particularly when it interacts with subjective, experiential understandings.

Bookfestivalopoly made explicit the interplay of critical acclaim and financial gain in trying to promote a book through book festivals, and the high risks at stake in so doing. This game, though, is also powerful as a metaphor of the geopolitical power relations at work in book festivals. Bookfestivalopoly makes it impossible to ignore the different levels of status and wealth generated by festivals. The hierarchical placement of festivals on the board deliberately replicates structures of prestige in the literary world; the geographical arrangement of the festivals produced one instantiation of Casanova’s world republic of letters. Our intentional referencing of these power dynamics potentially reinforces them, and was quickly questioned by players who perceived ethnocentrism in the arrangement of festivals. Yet while players challenged the placement of Scottish and Australian festivals, no one disputed the position of the United Kingdom festivals at the top of the hierarchy, and no one leapt to the defence of niche festivals from peripheral literary nations.

Physicality constrains real life festivals, and our games lay bare the Anglophone and metropolitan dominance of world literary markets, as well as vestiges of neocolonial power. The inequality that structures the global literary field is also highlighted through Book Festival Trumps, where the head-to-head competition between festivals repeatedly demonstrates the might of the biggest festivals on almost every conceivable metric. Even the textual elements of these cards tend towards accounts that perpetuate a colonial structure. For example, the abbreviated format of the USP strapline, as well as indicating the way that festivals are used in branding and marketing, led to us feeling uncomfortable about its potential to exoticise festivals (as in “ideas and iguanas” at Ubud Writers Festival).

Both games put a spotlight on the antagonistic aspects of literary festivals. The world of writing, books and publishing is competitive. Festivals may be presented as venues for generally polite democratic debate and cultural exchange, but their economy also introduces hierarchy: of festivals, locations and authors. Our game-inspired research has produced some models of what winning looks like for book festival organisers and writers: more money, more Twitter followers, and more connections with starry guests. These insights contribute to the larger scholarly debate about the neoliberal incorporation of culture into the economy, and the global economic inequities that undergird cultural events.

Conclusions: Game-inspired Thinking, Research and Book Festivals

The implications of this article for future research are twofold. First, game-inspired thinking has the potential to significantly enrich academic research by providing a mid-level perspective that offers something more than either case studies or abstract models. Second, game-inspired thinking specifically contributes to research on the complex emergent cultural phenomenon of the literary festival by highlighting its entanglement with neoliberal economic frameworks, its position in a globally unequal cultural field, and the subtle and varied pleasures it provides for audiences.

Designing games as metaphorical models of cultural phenomena enables researchers to think in terms of abstraction, and to move beyond the limits of the sociological impetus of data collection. Game design is an effective tool for structured, conceptual thinking, and for juxtaposing theoretical lines. Its value as a research method stems from the way that games represent phenomena in simplified graphic forms. This representational process helps articulate and intensify the aims, strategies and ritualised interactions of actors, and the conflict and resolution of various types of value across geographical locations and across time. As an arts-informed methodology, game-inspired thinking offers a scale and perspective on cultural phenomena that is an alternative to other social sciences and humanities methods—a mid-level approach that is neither close nor distant, and which is simultaneously structured and creative. Board and card games extend the value of this approach through their materiality and sociability, which invite players to interact with the game and with others, including those who might not normally participate in academic research.

For all these advantages, we recognise that there are limitations and risks to game-inspired thinking as a research methodology. Game-inspired thinking is not appropriate for every researcher, not least because it requires significant prior knowledge of the phenomena being adapted. In our case, the use of games builds upon a knowledge base developed through years of research into literary festivals, and offers an effective way to extend this. It also, as we noted earlier, relies to some extent on a position of privilege. Playfulness is risky. There is a chance that games can trivialise the real economic and reputational pressures on arts administrators and writers, and experiences of exclusion for writers and readers in particular demographic or geopolitical situations. We are mindful of the risk of our research becoming a “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” an instrumentalist tool rather than a freeing research process. Here, a distinction between “gamification” and “games” is crucial. As Jeff Watson argues, whereas gamification is “about the expected, the known, the badgeable, and the quantifiable . . . not about breaking free, but rather about becoming more regimented,” a “true game is a set of rules and procedures that generates problems and situations that demand inventive solutions. A game is about play and disruption and creativity and ambiguity and surprise. A game is about the unexpected.”[48]

Game-inspired thinking should subvert rather than reinforce power dynamics, as a method with inherent possibilities for critique. Players may, if they choose, relabel, redesign and recalibrate our games, adding in more festivals from other parts of the world, or, in Bookfestivalopoly, changing their hierarchical arrangement on the board. They could also, as one Bookfestivalopoly player suggested, change the rules to acknowledge the pre-existing advantage of different kinds of writers (taking into account gender, class, and race, for example). The next generation of these games, then, may see players—even or especially those with less research experience or job security—depicting radically alternative ways of interpreting book festivals and literary culture.

Like other forms of modelling, games also face the possibility of becoming overly simplified and divorced from reality. Reflecting on the uptake of his communications circuit, Darnton writes that “diagrams are merely meant to sharpen perceptions of complex relationships. There may be a limit to the usefulness of a debate about how to place boxes in different positions, provide them with appropriate labels, and connect them with arrows pointed in one direction or another.”[49] Yet this risk can be borne in mind while also recognising that the creation of diagrams, schemas and models is an important stage in developing scholarly understanding of cultural phenomena, particularly emerging ones such as festivals. As our results show, game-inspired thinking is a powerful and productive tool for this work.

For scholars of contemporary book culture, festivals have proven to be complex research objects. The existing panoply of disciplinary and interdisciplinary methodologies has not been able to fully capture the nuances, subtle effects and idiosyncrasies of literary festivals. Our game-inspired thinking has made progress towards this goal, through a collaborative process of experimenting with representations of book festivals. The research presented in this article activates the potential of scholarship that uses the game as a metaphor for literary culture by actually making playable games about festivals. This process has yielded previously hard-to-access information about festivals, including suggestive new data about the ease with which festivals can be subsumed within neoliberal frameworks of measuring, scoring and winning at culture, and the extent to which festivals produce unequal opportunities for writers and regional literary cultures.

These are challenging realisations for some humanities researchers. The process of playing our games creates experiences of discomfort, unease and even anger, not least because the competitiveness of the games can also shine a light on the competitive environment for academic research. Like the cultural sector, academia is increasingly governed by measuring, categorising, scoring, winning and losing.[50] At the same time, our games offer enjoyment and a sense of fun, highlighting the pleasures that book festivals provide. A playful approach to book festivals recognises the economic and geopolitical base of book festivals, but also hints towards aspects that are harder to capture: diverse behaviours, chance, and unintentionality in book festivals. In contrast to, say, demographic data-collecting,[51] the discursive and creative modes of our games reveal some of the subtle dynamics of festivals. It was, in fact, our early, seemingly failed sketches and the race game that hinted towards the capacity of games to resist stereotypes and gesture towards the experiential dimensions of book culture. Our games showed that highly simplified accounts and a focus on winning cannot account for festival attendees’ motivations and behaviour. Instead, varied personal and shared experiences need to be recognised, including our own.[52] Sociologically-oriented research continues to pursue a fuller understanding of audience experiences at book festivals, including through participant observation and ethnography within physical and digital spaces; our game-inspired research offers a mid-level perspective that enriches this quest.

Importantly, our research insights move beyond the sort of findings produced by case studies of individual festivals. As rich as individual case studies can be, they have limitations. Pragmatic constraints such as a researcher’s social networks, as well as the scholarly capital that comes from researching the largest, most visible events, mean that some festivals receive disproportionate attention. Metropolitan models tend to be reinforced. Moreover, a scholarly field dominated by individual case studies can lack systematic organisation. In contrast, our games consider multiple festivals and bring them into relation with each other via simplified forms. It was precisely this mapping of a network that yielded insights about the neocolonial relations between some festivals, the charismatic appeal of small festivals, and the dominance of the big festivals. These findings add nuance and specificity to Casanova’s account of the structural inequalities of global literary space. In its abstract but simultaneously personally-inflected, messy state, game-inspired thinking sits between, or perhaps alongside, individual case studies of book festivals and general structural models of literary culture.

Metaphors—particularly playable, material metaphors—open up new possibilities and prime us to see different things and approach them in novel ways. In contrast to diagrams that lie inert on the page, games can be readily tinkered with and their rules challenged or broken in a playful environment. For us as researchers of contemporary book culture, creating and playing these sociable board and card games has been a way to knock ourselves a little bit sideways, to think laterally. As this methodological experiment has shown, game-inspired thinking is a meaningful way to move forward, to shift thinking, and to open up new angles on a complex research object.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Dr Beth Driscoll is Senior Lecturer in Publishing and Communications and Program Coordinator for the Master of Arts and Cultural Management at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century (2014) and a Chief Investigator on the Australian Research Council Discovery Project, “New Tastemakers and Australia’s Post-Digital Literary Culture.”

Professor Claire Squires is the Director of the Stirling Centre for International Publishing and Communication at the University of Stirling, Scotland. Her publications include Marketing Literature: The Making of Contemporary Writing in Britain (2007) and, with Padmini Ray Murray, “The Digital Publishing Communications Circuit” (2013). She is a judge for the Saltire Society Literary Awards and Publisher of the Year Award.

Notes

-

[1]

We thank the following for their contributions to the development of this article: Millicent Weber for research assistance; students at the Universities of Melbourne and Stirling, colleagues, family and friends, for playing the games; conference delegates at the SHARP and CAMEo 2017 conferences in Victoria, Canada and Leicester, UK, for playing the games and feedback on conference papers; and Rik Bowen-Wheatley for the Bookfestivalopoly tokens.

-

[2]

Beth Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2014); David Finkelstein and Claire Squires, “Book Events, Book Environments,” in Cambridge History of the Book in Britain Volume 7: The Twentieth Century and Beyond, ed. Andrew Nash, Claire Squires, and Ian Willison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

-

[3]

Angela Bartie and Angela Bell, The International Writers' Conference Revisited: Edinburgh, 1962 (Glasgow: Cargo Publishing, 2012); Angela Bartie, The Edinburgh Festivals: Culture and Society in Post-War Britain (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013).

-

[4]

Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow.

-

[5]

Dan Glaister, “Thirty Years On, Hay Festival Is Still Thinking, Talking and Laughing,” The Guardian, May 28, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/may/28/thirty-years-on-hay-festival-still-thinking-talking-laughing.

-

[6]

Robin Robertson, Mortification (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004); A. L. Kennedy, On Writing (London: Jonathan Cape, 2013); Howard Jacobsen, “The Fearsome Nature of Literary Festivals, A Point of View—BBC Radio 4,” BBC, accessed September 4, 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08q7l8l.

-

[7]

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993) and The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996).

-

[8]

Millicent Weber, “Conceptualizing Audience Experience at the Literary Festival,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 29, no. 1 (February 2015): 84, .

-

[9]

Gisele Sapiro, “The Metamorphosis of Modes of Consecration in the Literary Field: Academies, Literary Prizes, Festivals,” Poetics (2016): 5, ; Claire Squires, Marketing Literature: The Making of Contemporary (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), p. 37.

-

[10]

Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow.

-

[11]

Beth Driscoll, “Sentiment Analysis and the Literary Festival Audience,” Continuum 29, no. 6 (November 2, 2015): 861–73, ; Simone Murray, The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation (New York: Routledge, 2012); Simone Murray and Millicent Weber, “‘Live and Local’?,” Convergence 23, no. 1 (2017): 61–78, .

-

[12]

Pascale Casanova, The World Republic of Letters (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004).

-

[13]

Cori Stewart, “The Rise and Rise of Writers’ Festivals,” in A Companion to Creative Writing, ed. Graeme Harper (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013), 263–77, .

-

[14]

Sarah Brouillette, “On the African Literary Hustle,” Blindfield Journal, August 14, 2017, https://blindfieldjournal.com/2017/08/14/on-the-african-literary-hustle/.

-

[15]

Graham Huggan, The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins (New York: Routledge, 2001).

-

[16]

Murray, The Adaptation Industry.

-

[17]

Beth Driscoll, “Local Places and Cultural Distinction: The Booktown Model,” European Journal of Cultural Studies, July 21, 2016, .

-

[18]

Brian Moeran and Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen, eds., Negotiating Values in the Creative Industries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Liana Giorgi, Monica Sassatelli, and Gerard Delanty, eds., Festivals and the Cultural Public Sphere (London; New York: Routledge, 2013).

-

[19]

Richard L. Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2002); Sarah Brouillette, Literature and the Creative Economy (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2014), 6.

-

[20]

AEA Consulting, “Thundering Hooves: Maintaining the Global Competitive Edge of Edinburgh’s Festivals,” 2006, https://aeaconsulting.com/insights/thundering_hooves_maintaining_the_global_competitive_edge_of_edinburghs_festivals.

-

[21]

AEA Consulting, “Thundering Hooves,” 4.

-

[22]

Beth Driscoll, “Sentiment Analysis and the Literary Festival Audience”; Katya Johanson and Robin Freeman, “The Reader as Audience : The Appeal of the Writers’ Festival to the Contemporary Audience,” Continuum 26, no. 2 (1 April 2012): 303–14, ; Wenche Ommundsen, “Literary Festivals and Cultural Consumption,” Australian Literary Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): 19; Gisele Sapiro, “The Metamorphosis of Modes of Consecration in the Literary Field: Academies, Literary Prizes, Festivals”; Millicent Weber, “Conceptualizing Audience Experience at the Literary Festival.”

-

[23]

Ellen Wiles’ ongoing PhD at the University of Stirling, “Live Literature: An Ethnography of Contemporary Fiction in Performance, From Festivals to Salons and Experimental Happenings,” gives more detail of this method.

-

[24]

Josée Vincent, “Les salons du livre à Montréal, ou quand ‘livre’ rime avec...”, in Autour De Le Lecture: Médiations et Communautés Littéraires, ed. Josée Vincent and Nathalie Watteyne (Montreal: Editions Nota Bene, 2002), 207–28.

-

[25]

Tested at the Cheltenham Festivals (including the Literature Festival), Qualia attempted to provide a “more emotive/qualitative” way of capturing audience responses to live cultural events, through a range of methods including sentiment analysis and a “smile installation.” Qualia was, admitted one of its developers, inhibited by the fact that Cheltenham Literature Festival’s “core audience tend not to be smartphone users.” K. Danielson et al., “Digital R&D Fund for the Arts 2012-15 | Arts Council England,” Cheltenham Festivals: Real-Time Event Feedback, 2015, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20161104073949uo_/http://native.artsdigitalrnd.org.uk/features/the-future-of-evaluation/

-

[26]

See, for example, Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus, “Surface Reading: An Introduction,” Representations 108, no. 1 (1 November 2009): 1–21, ; James F. English and Ted Underwood, “Shifting Scales Between Literature and Social Science,” Modern Language Quarterly 77, no. 3 (1 September 2016): 277–95, ; John Frow, “On Midlevel Concepts,” New Literary History 41, no. 2 (31 October 2010): 237–52, ; Heather Love, “Close but Not Deep: Literary Ethics and the Descriptive Turn,” New Literary History 41, no. 2 (31 October 2010): 371–91, ; Andrew Piper, “There Will Be Numbers,” Journal of Cultural Analytics, 23 May 2016, .

-

[27]

Email from Claire Squires to Beth Driscoll, 10 November 2015.

-

[28]

Nina Belojevic et al., “A Select Annotated Bibliography: Concerning Game-Design Models for Digital Social Knowledge Creation,” Mémoires Du Livre / Studies in Book Culture 5, no. 2 (2014), , para. 3.

-

[29]

Rita Felski, The Limits of Critique (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 52.

-

[30]

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, 190.

-

[31]

Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, 333.

-

[32]

James F. English and John Frow, “Literary Authorship and Celebrity Culture,” in A Concise Companion to Contemporary British Fiction, ed. James E. English (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006), 39–57; James F. English, “Winning the Culture Game: Prizes, Awards, and the Rules of Art,” New Literary History 33, no. 1 (1 February 2002): 109–35, ; James F. English, The Economy of Prestige (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005); Millicent Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

-

[33]

Casanova, The World Republic of Letters, 10.

-

[34]

Ardra L. Cole and J. Gary Knowles, “Arts-Informed Research,” in Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues (Thousand Oaks Sage Publications, 2008), 55–70.

-

[35]

Cole and Knowles, “Arts-Informed Research,” 61.

-

[36]

Cole and Knowles, “Arts-Informed Research,” 61.

-

[37]

Robert Darnton, “What Is the History of Books?”, Daedalus 111, no. 3 (1982): 65–83.

-

[38]

Padmini Ray Murray and Claire Squires, “The Digital Communications Circuit,” Book 2.0 3, no. 1 (2013): 3–24.

-

[39]

Felski, The Limits of Critique, 52.

-

[40]

Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber, The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016); Alison Mountz et al., “For Slow Scholarship: A Feminist Politics of Resistance through Collective Action in the Neoliberal University,” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14, no. 4 (18 August 2015): 1235–59.

-

[41]

The one exception to our rough aesthetic was the Bookfestivalopoly game tokens, which were skilfully designed and 3-D printed by Beth’s friend, Rik Bowen-Wheatley, in a generous act of support for this research.

-

[42]

Felski, The Limits of Critique, 53.

-

[43]

Monopoly was originally designed in 1904 as “The Landlord’s Game” by the inventor Lizzie Magie in order to teach the anti-monopolistic theories of Henry George; she sold the patent for $500 in 1935, and it was subsequently developed by Parker Brothers as Monopoly. See Mary Pilon, “The Secret History of Monopoly: The Capitalist Board Game’s Leftwing Origins,” The Guardian, 11 April 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/apr/11/secret-history-monopoly-capitalist-game-leftwing-origins.

-

[44]

Simone Murray and Millicent Weber, “‘Live and Local’?”.

-

[45]

For more on informal peer review, see the forthcoming article by Dorothy Butchard, Simon Rowberry, and Claire Squires, “DIY Peer Review and Monograph Publishing in the Arts and Humanities,” Convergence 24, no.4 Special Issue on the Academic Book of the Future (submitted).

-

[46]

As part of our reflective practice, we have written song lyrics that articulate dubious or resentful reactions to our research, including some where we imagine the point of view of early career colleagues. Our song lyrics are adaptations of Depreston by Courtney Barnett, prized by us for its flat emotional tone.

-

[47]

See John C. Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten, A General Theory of Equilibrium Selection in Games (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1988).

-

[48]

Jeff Watson, “Gamification: Don’t Say It, Don’t Do It, Just Stop,” Media Commons, 21 September, 2013, http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/question/how-does-gamification-affect-learning/response/gamification-dont-say-it-dont-do-it-just-stop.

-

[49]

Robert Darnton, “‘What Is the History of Books?’ Revisited,” Modern Intellectual History 4, no. 3 (2007), 505.

-

[50]

While undertaking this research, one of us was applying for promotion, a lengthy process which required the creation of extensive supporting written material. Given the increasing role of metrics in assessing academic value, we wondered whether Academia Trump cards would be a brutal but at least swift way of preparing and deciding on such applications.

-

[51]

We note that demographic data-collecting can be part of game-inspired thinking, as in the experimental ClueButedo feedback form we ran for the Bute Noir festival in August 2017 (www.twitter.com/cluebutedo).

-

[52]

As a tentative next step in exploring this diversity, we have begun making a series of paper dolls and accompanying narratives that represent different audience members at a range of festivals. For more information on this and other projects, see www.ullapoolism.wordpress.com.

Bibliography

- AEA Consulting. “Thundering Hooves: Maintaining the Global Competitive Edge of Edinburgh’s Festivals.” 2006. https://aeaconsulting.com/insights/thundering_hooves_maintaining_the_global_competitive_edge_of_edinburghs_festivals.

- Bartie, Angela. The Edinburgh Festivals: Culture and Society in Post-War Britain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

- Bartie, Angela, and Eleanor Bell. The International Writers’ Conference Revisited: Edinburgh, 1962. Glasgow: Cargo Publishing, 2012.

- Belojevic, Nina, Alyssa Arbuckle, Matthew Hiebert, Ray Siemens, Shaun Wong, Alex Christie, Jon Saklofske, Jentery Sayers, and Derek Siemens. “A Select Annotated Bibliography: Concerning Game-Design Models for Digital Social Knowledge Creation.” Mémoires Du Livre / Studies in Book Culture 5, no. 2 (2014). .

- Berg, Maggie, and Barbara Seeber. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

- Best, Stephen, and Sharon Marcus. “Surface Reading: An Introduction.” Representations 108, no. 1 (1 November 2009): 1–21. .

- Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Brouillette, Sarah. Literature and the Creative Economy. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2014.

- Brouillette, Sarah. “On the African Literary Hustle.” Blindfield Journal, 14 August 2017. https://blindfieldjournal.com/2017/08/14/on-the-african-literary-hustle/.

- Butchard, Dorothy, Simon Rowberry, and Claire Squires. “DIY Peer Review and Monograph Publishing in the Arts and Humanities.” Convergence 24, no. 4 Special Issue on the Academic Book of the Future (submitted).

- Casanova, Pascale. The World Republic of Letters. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Cole, Ardra L., and J. Gary Knowles. “Arts-Informed Research.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, 55–70. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2008.

- Danielson, K., J. Jenkins, M. Phillips, and E. Jensen. “Digital R&D Fund for the Arts 2012-15 | Arts Council England.” Cheltenham Festivals: Real-Time Event Feedback, 2015. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20161104073949uo_/http://native.artsdigitalrnd.org.uk/features/the-future-of-evaluation/.

- Darnton, Robert. “What Is the History of Books?” Daedalus 111, no. 3 (1982): 65–83.

- Darnton, Robert. “‘What Is the History of Books?’ Revisited.” Modern Intellectual History 4, no. 3 (2007): 495–508.

- Driscoll, Beth. “Local Places and Cultural Distinction: The Booktown Model.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, 21 July 2016, 1367549416656856. .

- Driscoll, Beth. “Sentiment Analysis and the Literary Festival Audience.” Continuum 29, no. 6 (2 November 2015): 861–73. .

- Driscoll, Beth. The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- English, James F. The Economy of Prestige. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005.

- English, James F. “Winning the Culture Game: Prizes, Awards, and the Rules of Art.” New Literary History 33, no. 1 (1 February 2002): 109–35. .

- English, James F., and John Frow. “Literary Authorship and Celebrity Culture.” In A Concise Companion to Contemporary British Fiction, edited by James E. English, 39–57. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006.

- English, James F., and Ted Underwood. “Shifting Scales Between Literature and Social Science.” Modern Language Quarterly 77, no. 3 (1 September 2016): 277–95. .

- Felski, Rita. The Limits of Critique. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Finkelstein, David, and Claire Squires. “Book Events, Book Environments.” In Cambridge History of the Book in Britain Volume 7: The Twentieth Century and Beyond, edited by Andrew Nash, Claire Squires, and Ian Willison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (forthcoming).

- Florida, Richard L. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

- Frow, John. “On Midlevel Concepts.” New Literary History 41, no. 2 (31 October 2010): 237–52. .

- Giorgi, Liana, Monica Sassatelli, and Gerard Delanty, eds. Festivals and the Cultural Public Sphere. London; New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Glaister, Dan. “Thirty Years On, Hay Festival Is Still Thinking, Talking and Laughing.” The Guardian, 28 May 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/may/28/thirty-years-on-hay-festival-still-thinking-talking-laughing.

- Harsanyi, John C., and Reinhard Selten. A General Theory of Equilibrium Selection in Games. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1988.

- Huggan, Graham. The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Jacobsen, Howard. “The Fearsome Nature of Literary Festivals, A Point of View—BBC Radio 4”. BBC. Accessed 4 September 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08q7l8l.

- Johanson, Katya, and Robin Freeman. “The Reader as Audience: The Appeal of the Writers’ Festival to the Contemporary Audience.” Continuum 26, no. 2 (1 April 2012): 303–14. .

- Kennedy, A. L. On Writing. London: Jonathan Cape, 2013.

- Love, Heather. “Close but Not Deep: Literary Ethics and the Descriptive Turn.” New Literary History 41, no. 2 (31 October 2010): 371–91. .

- Moeran, Brian, and Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen, eds. Negotiating Values in the Creative Industries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Mountz, Alison, Anne Bonds, Becky Mansfield, Jenna Loyd, Jennifer Hyndman, Margaret Walton-Roberts, Ranu Basu, et al. “For Slow Scholarship: A Feminist Politics of Resistance through Collective Action in the Neoliberal University.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14, no. 4 (18 August 2015): 1235–59.

- Murray, Simone. The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Murray, Simone, and Millicent Weber. “‘Live and Local’?” Convergence 23, no. 1 (2017): 61–78. .

- Ommundsen, Wenche. “Literary Festivals and Cultural Consumption.” Australian Literary Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): 19.

- Pilon, Mary. “The Secret History of Monopoly: The Capitalist Board Game’s Leftwing Origins.” The Guardian, 11 April 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/apr/11/secret-history-monopoly-capitalist-game-leftwing-origins.

- Piper, Andrew. “There Will Be Numbers.” Journal of Cultural Analytics, 23 May 2016. .

- Ray Murray, Padmini, and Claire Squires. “The Digital Communications Circuit.” Book 2.0 3, no. 1 (2013): 3–24. doi:doi.org/10.1386/btwo.3.1.3_1

- Robertson, Robin. Mortification. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004.

- Sapiro, Gisele. “The Metamorphosis of Modes of Consecration in the Literary Field: Academies, Literary Prizes, Festivals.” Poetics (2016): 5. .

- Squires, Claire. Marketing Literature: The Making of Contemporary Writing in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Stewart, Cori. “The Rise and Rise of Writers’ Festivals.” In A Companion to Creative Writing, edited by Graeme Harper, 263–77. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Vincent, Josée. “Les salons du livre à Montréal, ou quand ‘livre’ rime avec...” In Autour De Le Lecture: Médiations et Communautés Littéraires, edited by Josée Vincent and Nathalie Watteyne, 207–28. Montreal: Editions Nota Bene, 2002.

- Watson, Jeff. “Gamification: Don’t Say It, Don’t Do It, Just Stop.” Media Commons, September 21, 2013. http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/question/how-does-gamification-affect-learning/response/gamification-dont-say-it-dont-do-it-just-sto.

- Weber, Millicent. “Conceptualizing Audience Experience at the Literary Festival.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 29, no. 1 (February 2015): 84–96. .

- Weber, Millicent. Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

10.7202/1024783ar

10.7202/1024783ar