Résumés

Abstract

The British Columbia Chinese community struggled against political and economic racism and discrimination in the first half of the twentieth century. This study focuses on four festive civic celebrations in the period 1896-1936 when Vancouver’s Chinese Canadians employed traditional Chinese culture to assert their place as a legitimate component of the city’s social fabric. They joined official Vancouver in greeting China’s most respected statesman in 1896; participated in civic celebrations for visiting members of Britain’s royal family in 1901 and 1912; and organized one of the most successful aspects of Vancouver’s 1936 fiftieth anniversary celebrations, a four-week “Chinese Carnival.” Voices in the “white” community during the same period steadily but slowly articulated increased levels of acceptance of the Chinese presence. Changes in the popular journalistic portrayal of Chinese people reveal a gradual lessening of racist tropes and stereotypes. Finally, an English-language pamphlet produced in the Chinese community for the carnival provides a glimpse of how Canadian-born Chinese Canadians themselves were forging an increasingly North American identity, undermining arguments about their “inability” to adapt to Canadian cultural values.

Résumé

La communauté chinoise de la Colombie-Britannique a lutté contre le racisme et la discrimination politique et économique dans la première moitié du XXe siècle. Cette étude se concentre sur quatre célébrations civiques qui ont eu lieu entre 1896 et 1936, lorsque les Canadiens d’origine chinoise de Vancouver ont utilisé la culture chinoise traditionnelle pour affirmer leur place en tant que composante légitime du tissu social de la ville. Ils se sont joints au Vancouver officiel pour saluer l’homme d’État le plus respecté de la Chine en 1896, ont participé aux célébrations civiques pour les membres de la famille royale britannique en visite en 1901 et 1912, et ont organisé l’un des aspects les plus réussis des célébrations du cinquantième anniversaire de Vancouver en 1936, un « carnaval chinois » de quatre semaines. Durant cette même période, certains membres de la communauté « blanche » ont progressivement mais lentement exprimé leur approbation croissante envers la présence chinoise. Les changements dans la représentation journalistique populaire des Chinois révèlent une diminution progressive des tropes et des stéréotypes racistes. Enfin, une brochure en anglais produite par la communauté chinoise pour le carnaval donne un aperçu de la façon dont les Canadiens d’origine chinoise se forgeaient eux-mêmes une identité de plus en plus nordaméricaine, allant ainsi à l’encontre des arguments concernant leur « incapacité » à s’adapter aux valeurs culturelles canadiennes.

Corps de l’article

From 1 July to 7 September 1936, as Vancouver began slowly emerging from the Great Depression, it celebrated its fiftieth anniversary with a grand military review, street parades, and neighbourhood celebrations. Less than a month after the celebrations had begun, Mayor G.G. McGeer happily asserted – and the local press agreed – that the jubilee celebrations had given the city’s business community a much-needed “$20 million boost,” its best financial year in a decade.[1] Governor-General Lord Tweedsmuir, and the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Percy Vincent, imparted imperial benediction, the latter bearing a new civic mace.[2] Hollywood royalty such as Bette Davis and Shirley Temple added a more popular lustre. Local ethnic communities participated enthusiastically. Scandinavian “Norsemen” paddled a “Viking” ship to Stanley Park for a peaceful encounter with Native people. In addition to the Japanese community’s parade of 300 costumed young women, there were fireworks, and 10,000 free jubilee lanterns.[3] The Squamish nation named Mayor McGeer honourary chief, “Sun Risen From the East.”[4] They planned to make Shirley Temple an “Indian princess,” but the pint-sized American child star’s visit to the city was too brief to allow it.[5]

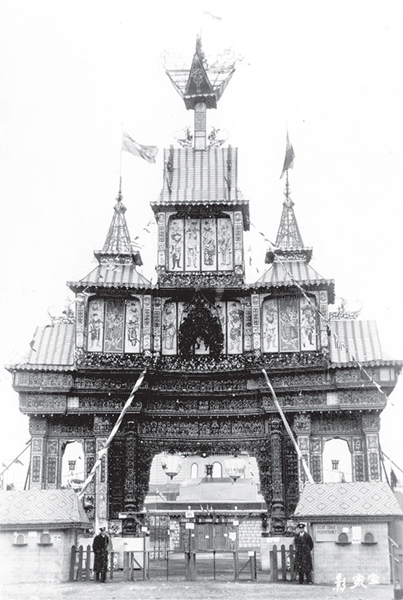

Chinatown’s business community raised $40,000 to produce a “Giant Chinese Carnival” on the southeast corner of Pender and Carrall Streets, today the site of the Chinese Cultural Centre and Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Garden. Attracting the equivalent of one quarter of the city’s population, over 65,000 locals and visitors, the carnival was so successful that ran for five weeks instead of the original three, from 18 July to 25 August.[6] The three Vancouver daily newspapers extensively covered it as the highlight of the jubilee celebrations, featuring photographs on their front pages of the elaborate 85-foot-high (26-metre) bamboo arch at the village entrance. Insured for $100,000, it had been built in Hong Kong for the Silver Jubilee of King George V in 1935, and then shipped to Vancouver along with nearly eight tons of fireworks for nightly pyrotechnic displays.[7] The village had a seven-storey pagoda with works of traditional Chinese artisans, a “farmer’s house,” and a “Mandarin Palace” with priceless Chinese artifacts.[8] A “Show House” staged Chinese dramas, fashion shows, and acrobatic performances. Visitors could anticipate “spectacular parades” three times a week, cultural lectures by visiting Chinese scholars, and even a Chinese “carnival queen,” who posed with Shirley Temple during one of her two visits to the village.[9] In this context, the term “carnival” signified a modern, commercially oriented tourist attraction shorn of its popular traditional European roots.[10]

The iconic 1936 arch was the fourth that Vancouver’s Chinese community erected for a civic festivity and was by far the most elaborate. But all four were visible illustrations of increasingly self-assured statements of belonging from the Chinese community, which employed these traditional arches to assert the value of its identity to the rest of the city. Their first arch in 1896 welcomed the leading Chinese statesman of the day. In 1901 and 1912, along with the rest of Vancouver, the Chinese community erected arches for visits by British royalty. During the period 1887–1939, ceremonial arches flourished briefly as Vancouverites marked nine civic milestones, beginning with the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1887 and ending with the visit of King George VI in 1939.[11] There had been earlier precedents in Victoria and Nanaimo where the Chinese communities had erected arches for Governor-General Lord Dufferin’s visit in 1876, and another in Victoria in 1882 for Governor-General the Marquis of Lorne and Princess Louise.[12] These arches identified the distinctiveness of the Chinese residents in Victoria and proclaimed their loyalty to the British Crown, but also noted “their inferior legal status compared to Canadians of European origin.”[13] In China such permanent arches (bailou/pai-lou) were prominent features of cities for many centuries, not to mention their de rigueur presence in Chinatowns everywhere today.[14] Likewise in early modern Europe, temporary arches alone or in series were erected on special ceremonial occasions as ritual displays to celebrate a ruler or viceroy’s first entry into a city.[15] Such spectacles, including Vancouver’s arches, were not merely collections of images, but “a social relation between people that is mediated by images.”[16]

Chinese participation in Vancouver’s four public celebrations was a mixture of ambiguity and contradiction. On the surface it seemed to validate a racist social discourse that marginalized the Chinese residents; on the other hand, their very presence implicitly subverted this discourse[17] Vancouver’s bailou, then, were not just apt cultural symbols designed to mark the presence of the Chinese community in stereotypically exotic ways for the Anglo community; they were also small brave gestures contesting the pervasive anti-Asian racism of the period. For years, British Columbians perceived Chinese people as foreign, dangerous, and unhealthy, depicted primarily for gambling, opium dens, and filthy living conditions, a social construct that had nothing to do with traditional Chinese culture and everything to do with “racial oppression and societal alienation.”[18] At the same time, the implicit acceptance of Chinese participation in the festivities studied here also indicates that Vancouver’s anti-Asian politics and culture were more complicated than we might expect. As Edgar Wickberg notes, by the 1930s changing white perspectives resulted in a new mood and “some indications that Chinese and whites in that city were beginning to move toward accommodation with each other.”[19] Accommodation usually meant brokerage politics operating beyond public scrutiny between the leading citizens of Vancouver and their influential Chinatown counterparts.[20] The significance of Chinese participation in the four celebrations held in Vancouver was that it involved mixed crowds of Chinese and “white” spectators together in public. Their arches were the visual means by which Chinese people “asserted metaphorically their claim to be accepted as respectable ‘citizens’ of Vancouver.”[21] In the summer of 1936, only a few voices (publicly at least) challenged that assumption.

By the 1920s and 1930s, there were more signs of support for Asians. A small example was the mayor of Vancouver opening a playground in Chinatown in 1928 on an empty lot at the corner of Pender and Carrall streets, future site of the 1936 carnival village. The Chinese Benevolent Association collected the $4000-5000 needed for the equipment from Chinese residents as well as from “[A] number of Canadians.”[22] Another was the Canadian Political Science Association’s endorsement in 1930 of Professor Henry F. Angus’ call to end racial discrimination against Canada’s permanent Asian residents, which the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Advertising and Sales Bureau of the Vancouver Board of Trade also supported. In 1931 the Canadian Legion and the United Church of Canada in British Columbia advocated for the enfranchisement of all Canadian-born Asians, as did the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation.[23]

Patricia Roy places the more favourable view of Chinese Canadians within the context of “[a]n interlude of apparent toleration, 1930-38,” the marginalization of “a small vocal group repeating atavistic arguments” against Asians, and the more influential voices of newspaper editors and others advocating toleration for Asians already here.[24] But the toleration was shallow, reflecting apathy in the white population rather than acceptance. Early and hesitant steps to inclusiveness from the small number of Anglo allies studied here meant that Chinese Canadians had a long wait before being fully recognised as citizens. Some would argue that they still face racism.[25] High regard, however sincere, did not translate into enough support to change discriminatory civic policies until well after 1936. For decades Chinese people were barred from many aspects of public life, the professions, and even public spaces such the Crystal Pool, the only civic pool in Vancouver, open to them just one day a week until the policy was reversed in 1945.[26]

Chinese participation in Vancouver’s civic ceremonies of 1896, 1901, and 1912 has so far gone unexamined. Historians who mention the 1936 carnival present it as an inconsequential respite from the anti-Oriental racism of the period, an early step in romanticizing Chinatown for the local tourist industry. Earlier “unflattering stereotypes about the inscrutable heathens and their disease-ridden homes” gave way to “[A]ge-old fantasies about China’s ancient and venerated civilization.”[27] By examining the Vancouver press coverage of the Chinatown Carnival in 1936, and the three bailou the Chinese erected before that, we can discern the gradual evolution of a more inclusive Anglo-Vancouverite view of the local Chinese. Newspapers as informal gatekeepers of popular knowledge were the primary means by which Vancouverites got their information during this period. The mixture of (mis)information and the opinions of newspaper writers framed the parameters of people’s negative perceptions of Asian immigrants for decades.[28] As Roger Chartier has argued, representation is never neutral; one’s subjectivity determines how one chooses to (mis)represent what one sees. In the case of Chinatown, negative or even positive representations of the place by outsiders and insiders alike were not culturally or socially unbiased, although they were not static either.[29]

As we shall see, the local press that shaped Vancouver’s public discourse about Asian immigration gradually changed in the period 1896-1936 from vociferous opposition to implicit acceptance of Chinese people as Vancouverites. Over the four decades newspapers gradually reframed negative portrayals into more positive, though not necessarily more accurate, ones. Accounts by Anglo-Vancouver journalists on the four daily newspapers in the city during the period 1896–1936 — the Daily World (published 1888–1924), the News Herald (published 1933–1957), the Daily Province (since 1898), and the Sun (since 1912) — largely represented Chinatown as the local version of the mysterious “Orient.” Comparing these outsider views with how Chinese people perceived themselves in The Chinese Times (published in Chinese from 1914–1992), is equally necessary but beyond the scope of this paper.[30] Instead, the English-language pamphlet Vancouver Chinatown — Specially Prepared for the Vancouver Golden Jubilee 1886–1936, by Quene Yip, who was born in Chinatown and participated in organizing the carnival of 1936, is a useful foil to the accounts of non-Chinese commentators. Used with care, his detailed descriptions of many aspects of life in Chinatown provide a rare and important contemporary Chinese-Canadian perspective.[31]

The carnival’s role in the Anglo-Vancouverite commodification of Chinatown by playing to these stereotypes is particularly evident in press coverage of the 2500 Chinese art treasures that former McGill professor Dr. Kiang Kang-hu (Jiang Kanghu) brought from China just four days before the village opened.[32] Three hundred cases weighing 130 tons (not all of which could be exhibited on the cramped site) were the highlight of the village. The Sun approvingly termed the carnival the “million-dollar festival” thanks to the estimated value of these “treasures from the finest collections of China.”[33] The trove included “rare bronze Buddhas from Tibet, delicately carved ivory ornaments, and 2000 other articles from the Imperial Palace at Peiping.”[34] Journalistic comments that the art treasures displaying a few thousand years of Chinese culture were “spellbinding in their beauty” indicate honest admiration rather than mere Orientalism.[35] They suggest that, although most Vancouverites and tourists would hardly have understood everything they were seeing, it is possible they recognized that the culture which had produced them was worthy of respect. Whether veneration of China’s ancient civilization implied respect for their modern Chinese fellow citizens is another matter.

The affirmative effects of the “million-dollar” exhibit of cultural artifacts in 1936 upon Canadian-born Chinese, and poor immigrants from Guangdong province, are also unknown but must have been powerfully affirming. Few ordinary people in China itself would have beheld such a concentrated display of their culture; Vancouver’s locally-born, likely never. Seeing the depth, range, antiquity, and quality of their culture would have been, one imagines, a bracing if temporary antidote to some of the put-downs that Chinese people were subjected to. The affirmative power of their cultural materials and practices helped the Chinese immigrants to survive in a hostile environment and to mitigate the loneliness new immigrants expressed in poems scrawled on the Victoria immigration shed’s walls.[36] In addition, traditional religious rites and cultural practices were available to them year-round, enabling them to defend their ethnic solidarity.[37] Chinese theatre and opera, as well as gambling and the annual Chinese New Year celebrations, helped relieve “the cheerless circumstances for some.”[38] Others established newspaper and book-writing clubs, held poetry contests, and presented Cantonese operas and modern plays that often attracted large audiences.[39]

The Visit of Li Hongzhang (Li Hung Chang), 1896

Another form of affirmation came just a decade after the founding of Vancouver when Li Hongzhang, China’s pre-eminent statesman, passed through the city on 14 September 1896 on his way home from an eight-month diplomatic tour of the major European and North American capitals. This tour sought to advance China’s modernization, a pragmatic approach for mitigating some of China’s glaring weaknesses in its encounters with the West.[40] He attended Tsar Nicholas II’s coronation in Moscow, visited retired Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, stopped in Paris, and was welcomed in England by the Prime Minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil (Lord Salisbury) and leading figures of society. Queen Victoria personally invested Li as a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order. After visiting New York and Washington, he attended Toronto’s Canadian National Exposition where an estimated 100,000 people strained to catch a glimpse of him.[41] Li met high-ranking Canadian officials, notably Sir Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, future Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia. After a day in Toronto he boarded the Canadian Pacific Railway to Vancouver and returned home on the CPR’s “Empress of China.”

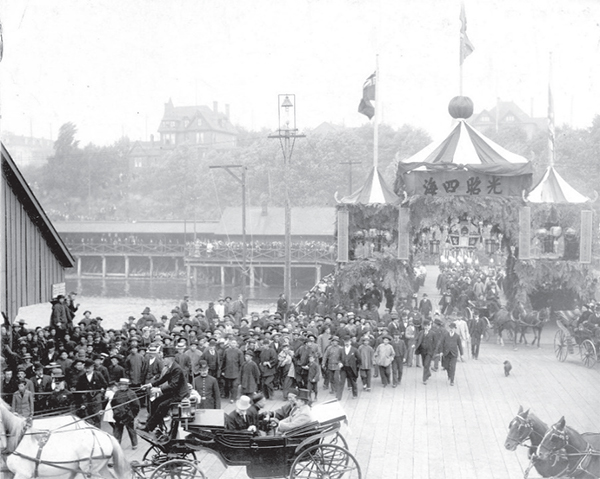

For Li’s visit, the Vancouver Chinese Merchants’ Exchange commissioned City Engineer Colonel Thomas H. Tracy to design a tall, three-gated arch of tree boughs, Chinese lanterns, the Union Jack, the Chinese dragon flag, and the Canadian ensign at the CPR pier.[42] The sign board on the central arch facing the city had two Chinese characters honouring a highly respected official. The one facing the pier suggested that Li’s light illumined the four seas, i.e., the world. Accompanying Li and his interpreter in his carriage were Mayor H. Collins and CPR General Superintendent H.H. Abbott. A week before Li arrived, Vancouver’s Daily World published effusive accounts of his long career as “a liberal statesman” who promised to modernize China.[43] Over 6000 people of all nationalities including Chinese from Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco welcomed him.[44] Chinese people “fell on one knee and raised clasped hands to him as he passed, smilingly by.”[45] The elite of Vancouver, showing no reluctance to be seen with this particular “Chinaman,” lavished him with the same deference they would accord British royalty six years later. The Board of Trade and the City presented Li with addresses, visiting naval vessels saluted him, and the consuls of Spain, France, Japan, Ecuador, and the United States paid their respects. On the “Empress of China,” Li met with Chinese merchants from Victoria, Seattle, and Portland, as well as Vancouver’s representatives Yip Sang and Yip Yuen.[46] Congratulating them on the “good service” the Chinese had done, Li advised them to learn English and to refrain from smoking opium or gambling.[47] One could almost believe the Sacramento Daily Union’s comment, “For the day the whole social order was subverted, and Chinamen everywhere took precedence over their white brothers in the good-natured throng.”[48]

Li Hongzhang arriving at the CPR pier, Vancouver, 14 September 1896. Note the crowded galleries on shore.

Even if that harmonious picture was true only for one day, the effects on the Chinese people in the vast crowd and the obsequious reception that Li received from Canadian politicians and dignitaries must have been pleasantly disorienting, though somewhat puzzling. Li’s welcome contrasted sharply with the hostile treatment members of the Chinese community were used to, relegated as they were (in fact if not in name) to a ghetto on the swampy edge of False Creek..[49] Anticipating Li’s visit, the Daily World argued that if he “observes our spacious residences, our handsome business blocks and clean streets” and then “visits Chinatown and compares the squalor and filth with the delights he has before seen His Excellency will obtain a dim idea of what we suffer from.”[50]

But even for such an important guest as Li Hongzhang, it did not take long for the noxious fumes of racism to emanate again from the local press, the politicians, and some Protestant pulpits. Despite the elaborate courtesies enveloping Li’s welcome, he had no success in changing Canada’s fifty-dollar head tax on Chinese immigrants. Coincidentally, perhaps, while Li’s train was heading west, the Daily World approvingly printed in full Vancouver-Burrard MP and Presbyterian minister George R. Maxwell’s speech in Parliament advocating for an increase in the tax to $500, claiming Chinese immigrants were “taking away the living of the white people.”[51] It was unwise to welcome “semi-barbarians” who lived on almost nothing, were addicted to opium, were inveterate gamblers, and were grossly immoral. Instead, concluded Maxwell, “We want to fill that land with honest men and bonnie lasses […] with people who have respect for our laws, who will become citizens of the country in which they live.”[52] British Columbia politician W.W.B. McInnes, the eminence grise behind the Asiatic Exclusion League that was responsible for a mob attacking Vancouver’s Chinese and Japanese quarters on 7-8 September 1907, argued in the House of Commons a few weeks later that Chinese people were the “vile product of congested Asian life” and “the refuse of humanity.” Their low wages resulted in “the white laborer driven from his work,” “white farmers forced off their farms,” and “white families reduced to the verge of starvation.”[53]

Conceding as much, Li argued that “competition, and competition alone, will keep the market in good health, whether the market is of commerce or of labor.” [54] The more Chinese immigrants the better, he argued, as did CPR President William Van Horne. Vancouver alderman James Fox even argued in 1890 that two million Chinese immigrants might be necessary to open up British Columbia’s natural resources.[55] Li seems to have been aware of another Anglo-Scottish prejudice when he added: “By excluding the Chinese and taking the Irish you get inferior labor and pay superior prices for it. A Chinaman lives a more simple (sic) life than an Irishman […] Is it fair to exclude my countrymen?”[56] But regardless of fairness, it was not just politicians attacking Chinese immigration. On 16 September 1896, just after Li’s ship had left Canadian waters, the Dominion Trades and Labour Congress unanimously resolved that the Chinese head tax needed to be increased to $500.[57]

The Visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, 1901

Five years after the visit of Li to Vancouver, the city welcomed HRH Prince George, heir to the British throne, and Princess Mary, his wife, from 30 September to 3 October 1901. The couple arrived from Eastern Canada on the CPR for a brief visit during the final leg of their 50,000-mile tour of the Empire. Graced by the presence of their future sovereign, the city’s wealthy business and professional class, “Vancouver’s 400,” could observe even more punctiliously the petty distinctions and arcane rituals of social imitation perfected in Britain’s aristocratic circles.[58] Citizens decorated houses and buildings while a civic decorating committee prepared 3,500 flags and 3,500 yards of bunting for the royal parade route. The Chinese community erected a traditional arch at Hastings and Carrall Streets with a central gate for street traffic and smaller side gates for pedestrians. The structure’s lower half of evergreen boughs supported three Chinese-style towers of coloured fabric and roofs with upturned eaves illuminated at night with electric lights.[59] The centre of the arch had “Welcome” written in large letters and a balcony with Chinese lanterns where one hundred Chinese children greeted the Prince and his entourage, “a sight which no other part of Canada could offer him.”[60]

Canada’s official report by Under-Secretary of State Joseph Pope, as well as the British account of the tour, both agreed with how handsome, striking, and original the Chinese and Japanese arches were.[61] Included among Vancouver’s civic, mercantile, and Squamish First Nation addresses delivered at the courthouse was the combined welcome of the Chinese Empire Reform Association and the Chinese Merchants of Vancouver, who, “as citizens of Oriental origin tender to you and through you to our lord the King, hearty expressions of loyalty and devotion.” They concluded with the assertion that “among all his subjects in the many lands and climes which form his great empire his subjects in British Columbia of Chinese origin are second to none in their loyalty and devotion.”[62] Local press accounts did not mention this address. Instead, on the day the Duke and Duchess arrived, the Daily World warned of the dangers of cheap Chinese labour and alluded to the white community’s presumed consensus of “the Chinese as belonging to a stagnant civilization.”[63]

The Visit of the Duke of Connaught, 1912

In September 1912, Vancouver feted HRH Prince Arthur the Duke of Connaught, Governor-General of Canada, and uncle to George V. Eleven arches welcomed his four-day visit and 10,000 people turned out on 18 September as the Duke’s procession passed along Hastings, Main, Pender, Granville, and Georgia Streets to the new courthouse on Georgia Street.[64] The cavalcade passed beneath two Chinese arches, one on Hastings Street and the other on Pender at Carrall Streets in Chinatown. Supported on tall poles wrapped in coloured bunting and held in position by guy wires, the Hastings arch had a single opening spanning the street. The upper part had two undulating dragons converging at a central peak adorned with small flags. The word “Welcome” appeared above the street, with a dragon on each side, the dragons and the greeting all traced in electric lights.

The more elaborate Chinatown arch had two small pedestrian gates and a larger one spanning the street. Evergreen boughs covered the side towers, the tops of which were faced with Union Jacks. Hanging from the central arch were eighteen Chinese lanterns above which was a large hand-painted “Welcome” sign topped with a small portrait of the Duke in military uniform. Above that were large Chinese characters for “Welcome”: 歡迎 (Huānyíng) centred in a fan-shaped arrangement of fabrics probably representing the five colours of the first flag of the new Republic of China. The picture of Pender Street shows Chinatown’s principal thoroughfare behind the arch, bordered by two- and three-storey brick buildings leading to Main Street. Passage of the Duke’s party through this area, a first for Chinatown, represented a reassessment of its suitability as place of interest for a royal visitor. However, near the end of the Duke’s visit, the Daily World weighed in with opposition to Asian immigration. Canada could only “rise to the pinnacle of greatness” as a white man’s land, the newspaper claimed. “Asiatics are of clever, persevering races but they must forever be opposed to us in the ideals so essential to our perfect national life.” Hence, “they must never be permitted the privileges of citizenship.”[65]

Twenty-four years passed between the Duke’s visit and the 1936 celebrations, and a much more positive tone about Vancouver’s Chinese community in the public discourse slowly emerged in the interim. It may have been partly due to the small and static size of the local Chinese population thanks to the Exclusion Act of 1923, which severely curtailed most immigration from China and thus considerably reduced a main source of racist tension.[66] Compared to previous denigrations of Chinatown – in 1925, a local publication even told visitors that it was “not a show area” –the city’s Official Pictorial Souvenir Program for its 1936 Golden Jubilee was gushingly effusive. [67] It took pains to highlight the “glamour that is found in the Orient” in the Japanese and Chinese parts of town. “Scores of Chinese stores, a riot of colour and pungent with the odours of ancient China offer a paradise for the curio hunter, the jade lover and the collector.”[68] Chinatown was a “little city-within-a-city where Vancouver’s Chinese population conducts its affairs in its own leisurely fashion.” There, “Yellow gods rule, and the Occident fades into the background.”[69] Chinatown was still exotic, though it was not necessarily any less coloured by an Orientalising subjectivity. It was reassuringly peaceful rather than dangerous, a picturesque economic asset to the city with the potential to attract tourists. Partly thanks to the success of the carnival, Chinatown had “a rare fascination for Eastern visitors […] worth exploiting as a tourist attraction year in and year out.”[70] Playing up the same theme, Yip’s pamphlet promised a village that would be decorated with “lanterns and hundreds of Oriental splendours […] directly imported from the ‘Celestial Empire.’”[71] This was the Chinatown that other Vancouverites and visitors flocked to in 1936.

The Chinatown that its residents experienced as part-ghetto/part-refuge was, however, not primarily a place that catered to tourists. According to Yip, but at variance with his tropes about the Celestial Empire or mysterious opium dens and “secret winding corridors,” Chinatown was hardly different from any other small Canadian community: peaceful, self-contained, and law-abiding. As the 1912 photograph shows, its architecture wasn’t even “Oriental.” No trace of past violence or exotic behaviour remained because the community had embraced the British system of law and the nationalism of Dr. Sun Yat-sen as a replacement for “clannism.”[72] The “tong” (clan association) feuds of the past were a distant memory, perhaps a disappointment to tourists and locals alike who might have relished at least a tiny frisson of apprehension by imagining that on the very streets they were visiting there still lurked such things. Yip may have been making a conscious attempt to correct the long, ignoble myth about the impossibility of assimilating Chinese people into Canadian life. But he was well positioned to do so. He has been termed a “Canadian-born Chinese interpreter, insurance agent, and all-around fixer,” but he was more than that.[73] The sixteenth son of Yip Sang, one of Chinatown’s richest and most powerful merchants, he attended the University of British Columbia in 1925–26 and Queen’s University in 1927–1929, and he supported or played on the Chinese Students’ Soccer Team during the period 1920–1940. The Vancouver Chinese Students’ Athletic Club soccer team, the only Chinese team in Canada and the first outside China, won local championships against white teams in 1926, 1933, and 1936. When the Chinese team unexpectedly won the Provincial Soccer Championship on 29 May 1933, thousands of fans celebrated with a parade and victory party on Pender Street followed by a holiday the next day in Chinatown with free tea and dim sum for everyone. As a star player, Yip carried the trophy. The parallels with the famous Vancouver Asahis Baseball Team in raising the self-esteem of Japanese Canadians are evident.[74]

Yip went to some pains to reassure his readers that the lives of Chinatown’s inhabitants were very much the same as those of Vancouver’s other citizens. He described the generational differences around leisure activities such as sport to which older men paid no attention but young people did.[75] While elder men socialized in tea houses — Yip equated their social function with the role taverns played to their white counterparts — young native-born Chinese socialized with friends or went to one of two recently-opened cabarets in Chinatown. Traditional arranged marriages were also being abandoned in favour of Western-style courtship and marriage.[76] However, Yip did not mention the restricted opportunities for the majority of Canadian-born young Chinese who did not have the same advantages as the relatively small number of people like himself from well-off families.[77] As Denise Chong found, life was much harder for poorer women like her grandmother, a secondary wife who came to Canada to provide companionship for her grandfather who planned to return to China where his first wife and children lived.[78] Life was also difficult for most men thanks partly to the gender imbalance. Chinatown was a community made up largely of bachelors. In 1881 the ratio of men to women was 70:1; in 1921 it was 25:1; and in 1941, it was 10:1.[79]

Of necessity, because Chinese people were made unwelcome in the rest of the city, though that was less true by the 1920s, Chinatown’s small area on the “wrong side of the [CPR] tracks” had dozens of businesses of various sizes and values catering to the full range of its people’s needs, and only available to them there.[80] The large and influential entrepreneurial sector had grown from 71 businesses in 1901 to 236 in 1911. The four top firms in 1908 averaged from $150,000 to $180,000 annually, or six times the average income of two-thirds of Chinatown’s other business. They also owned real estate in Chinatown worth $2 million, and had other holdings worth $1 million elsewhere in the city.[81] Enterprises such as laundries, located outside Chinatown by municipal regulations, were an important occupation for male immigrant workers, although this was unusual work for men in China.[82] Compared to their white counterparts, the effects of the Depression on Asian workers were more severe due to the added factor of racism.[83] Since Chinese and Japanese workers were ineligible for civic relief, many were forced to turn to charities such as the notorious soup kitchen at 143 Pender Street run by the Anglican Church. Several letters to the City from the Provincial Workers Council on Unemployment argued that the meagre fare the soup kitchen dispensed caused the deaths of over 175 Chinese Workers. Even a 520-signature petition from Chinese workers who used the soup kitchen did not change the City’s apparent indifference.[84]

Education in Chinatown differed from the white community. Around age four, Chinese children went to kindergartens in the various Chinese churches to learn hymns and study English.[85] At age six, they attended one of Chinatown’s six Chinese public or private schools to learn composition, Chinese literature, “history, geography, letter-writing, penmanship, public speaking, ethics and at times Confucianism.”[86] A correspondence school taught classical poetry, letter writing, and the Chinese classics.[87] Some better-off children learned the violin or the piano or joined the Wolf Cubs. Since there was no Chinese high school or college, children attended local English high school; some, like Yip, went to university in Canada or the United States. At the University of British Columbia there were 22 Chinese students, mostly locally born. Many university graduates looked to find employment in China.[88]

Yip says that the majority of people in Chinatown continued to follow Chinese traditions and customs.[89] Older people studied Confucianism or Buddhism, and younger people learned ethics in school rather than Christianity. Jiwu Wang argues that people’s devotion to Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism centred more on religious rituals of a transactional nature rather than doctrine. To the chagrin of the Christian missionaries and their message of a personal connection with Christ, most Chinese seemed to think that “intensive personalized prayers were as incongruous as they were unnecessary.”[90] Another impediment to Christian proselyting was Confucianism’s view that human nature is basically good; people transgress because they had strayed from their original nature, the exact opposite of a common Christian belief in original sin.

One significant aspect of Chinatown’s daily reality, however, seems to have escaped everyone’s notice. It was one of the more polluted areas of Vancouver. Looming just one block south of the carnival village were the two coal gas storage towers (total capacity 203,400 cubic feet) and coal-fired ovens of the Vancouver Gas works, for decades Vancouver’s source of fuel and lighting. There were retort houses, purifier tanks, and a water gas plant. Coal as a fuel releases gases and particles linked with chronic bronchitis, aggravated asthma, heart attacks, and premature death.[91] Equally seriously, coal gas was produced in an oxygen-starved environment, producing carcinogenic coal tars and heavy metals, and pollution of groundwater.[92] South of the gasworks and on the other side of the first Georgia Viaduct stood the B.C. Electric Railway Company’s coal-fired powerhouse and briquette making facility.[93] Nearby were the Canadian Pacific railyards. Almost all the Chinese-origin population of Vancouver, numbering just over 13,000 in 1931, lived in Chinatown. For those who fell ill from the effects of pollution, overcrowded or unsanitary living quarters, or infectious diseases, there was only one doctor, who served at St. Joseph’s Oriental Hospital at the eastern edge of Chinatown on Campbell Avenue.[94] Needless to say, this was not the Chinatown that other Vancouverites or tourists “saw” in 1936.

Vancouver Chinatown circa 1936.

The Carnival of 1936

Despite the tourist appeal of Chinatown, it was only on 13 February 1936 that the Golden Jubilee Committee thought to encourage participation from the Chinese and Japanese communities. But thanks to years of lurid press accounts of gambling dens in Chinatown, the committee stipulated that “no games of chance should be allowed.”[95] The Chinese community quickly promised a carnival village “worthy of considerable tourist attention.” Nearly four months of intensive organization followed. Barely a month after the Chinese community’s initial response, the Jubilee Committee praised the “wonderful attractiveness” of their proposal.[96] On 2 May the Committee’s Managing Director, John K. Matheson, told the Mayor that it would be “on a very high plane.”[97] Publicity brochures had to be amended to include “July 18 to Aug. 8 — Great Chinese Festival.”[98] Leading members of the public, city council, and press at the village preview two days before its official opening unanimously agreed: the “carnival exhibition [is] one of the finest things that ever came to Vancouver.”[99]

Chinatown and Carnival Village, Vancouver, 1936.

Under warm sunny skies on 18 July, Mayor G.G. McGeer formally opened the carnival village with a favourite theme, “the destiny of young and growing Vancouver as Canada’s entry to commerce with the vast millions of the Orient.”[100] Dr. Kiang Kang-hu (Jiang Kanghu), who had brought the Chinese art treasures to Vancouver a mere four days earlier, said he bore greetings from the “very old city of Peking in the very old nation of China” to “the very young city of Vancouver in the very young nation of Canada.”[101] Seto More, President of the Chinese Benevolent Association and Chair of the Chinese carnival board, and Chunhow H. Pao, Chinese Consul General, also spoke. The Mayor revealed that he maintained “very amiable feelings toward the Chinese as a whole,” as a Chinese farm hand had rescued him from an angry bull when he was a small boy.[102] On opening day, the Sun’s front page featured a cartoon by Les Callan showing the stereotypical figures “Old China” and “Young Canada” shaking hands over the Chinese village under the caption “A Noble Contribution […] Made possible by Vancouver’s Public Spirited Chinese Citizens.” Sun reporter Pat Terry suggested that “the Occidental section of this city” could learn from their public spirit.[103]

The crowd at the inaugural parade for the carnival village was “the largest since the Dominion Day parade” and was the “prelude to the thrilling, million-dollar Chinese festival, high spot of the Golden Jubilee.” After leaving Chinatown it followed the same route through downtown as the British royal visits of 1901 and 1912, an unusual honour for the Chinese community. There was a float for the Chinese carnival queen, Grace Kwan, and another bearing a Chinese worker with a pick and shovel seated on a section of railway track, a reference to the construction of the CPR.[104] So many people came to see the village, and so great was the traffic that special constables were needed, but everyone left “satisfied that they had seen one of the most wonderful exhibitions ever staged in Vancouver.” The Sun estimated that 35–40,000 people came to see the village in the first three weeks alone.[105]

Superlatives regularly accompanied the exhibition of art treasures sent by the Nanjing government and private collectors to Vancouver. Kiang himself “remarked wistfully in his speech that he would like to see a permanent institution in Vancouver … for their study and appreciation.”[106] The Vancouver Sun agreed that the city’s youth should be exposed to these artifacts and a building should be erected next to the Art Gallery to house them.[107] With the political situation in China deteriorating because of increased Japanese military aggression, maybe that had been Kiang’s hope all along. But no private philanthropists came forward and the City Solicitor pointed out that the civic charter did not permit Vancouver to cover the cost of insurance for the collection.[108] In late August, Kiang regretfully informed Mayor McGeer that he would return to China and restore the artifacts to their owners.[109] Just one month earlier, Japan had begun its nine-year invasion and occupation of China, a period of chaos that continued for four more years with the civil war that followed. The fate of the artifacts, not to mention their owners, is unknown.

The bamboo arch was the last traditional arch erected in Chinatown until the construction of the China Gate for the Chinese pavilion at Vancouver’s Expo 86. When King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited Vancouver during their tour of Canada on 29 May 1939, their 80-kilometre drive from City Hall to Hastings Park and the North Shore bypassed Chinatown via the Georgia Viaduct. There was no Chinese arch for them this time, only some pictures of the royal couple in shop windows. The custom of erecting arches for public celebrations had by then petered out in Vancouver, too. An arch composed of totem poles, located on Marine Drive in North Vancouver near the Capilano Reserve, which said “Welcome to Our King and Queen” from the “B.C. Indians,” appears to have been an exception.[110]

Chinese, Canadians, or Chinese Canadians?

The success of the carnival village indicates a greater acceptance of the presence of Chinese Vancouverites by 1936, but also ambiguity about what that really meant in the Chinese community and in the rest of the city. One of the carnival’s stated purposes was to enlighten tourists (presumably Vancouverites, too) about Chinese life there. Ironically, however, the “Oriental splendours” highlighting the “exotic” features of Chinese culture may have caused confusion in the minds of visitors and locals alike. Anglo Vancouverites already seemed unsure whether the inhabitants of Chinatown were members of a foreign enclave or an integral part of the local landscape, as there were as many references to “our Chinese colony” in the local press over the years as there were to “our Chinese citizens,” although the proprietorial “our” implied an implicit recognition that they somehow also belonged in Canada. On the other hand, the presence of the Chinese consul beside the mayor at the opening of the carnival village suggests the ambiguous sense of citizenship for Chinese people. Chinese consulates in Vancouver and Ottawa saw themselves as looking after the interests of Chinese in western Canada. It appears that many local Chinese agreed that they and the Chinese state shared some common political concerns. Vancouver’s office of the Chinese Nationalist League (Guomindang) had about 800 members locally and approximately 8,000 members across Canada.[111] Early in September 1936, the Sun informed its readers that two representatives from Canada to the Chinese Parliament in Nanjing would be chosen from among a list of names submitted by various Chinese organizations across Canada.[112]

Political ties to the homeland may have been a partial reflection of differences between the political commitments of the older generation to China and the local identity of the second and third generations of the Canadian born. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, this was an evolution that the local press amply documented in the Anglo community itself, more often referring to Anglo British Columbians by the 1930s as Canadians instead of Britons. As early as 1914, some locally-born Chinese men in Victoria began calling themselves Chinese Canadians. Unlike many second-generation immigrants to Canada from Britain, but more like French Canadians, they affirmed simultaneously that their ethnic identity could be combined with their Canadianness; being Canadian could accommodate being Chinese.[113] Among ordinary second- and third-generation Chinese Canadians that Wayson Choy depicted in his novel The Jade Peony, the three young siblings who had never been to China barely felt the tug of the motherland compared to their parents and grandmother.[114] The intergenerational cultural changes in Vancouver were similar to China’s own move away from traditional norms thanks partly to the influence of the May Fourth Movement of 1919, and no doubt partly also to the availability of so much contemporary material from China available in the six bookstores in Chinatown.[115] Vancouver’s press provided local readers with more positive images of China after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in contrast to its generally negative portrayal of China before 1911. Two years after Li Hongzhang’s 1896 visit, China’s “Hundred Days” reform movement of 1898 was quashed. Its leading spirit, Kang Yuwei, advocating for a constitutional monarchy, found refuge in Victoria and established the headquarters of his Chinese Empire Reform Association.[116] In 1903, his principal associate, Liang Qichao, inaugurated the CERA building in Vancouver, precipitating a period of intense political engagement in Chinatown between it and Sun Yat-sen’s republican alternative.[117] During the Revolution of 1911, the Daily World provided extensive coverage of the revolt against the Qing Dynasty in October, even noting that there were two meetings in Chinatown to discuss the unfolding events in China.[118] Sadly, in the same issue, a caricature of local Chinese revolutionary volunteers satirically depicted six unimpressive men respectively brandishing various kitchen utensils and an opium pipe. However, when a republic was declared by imperial proclamation the following February, the Daily World’s front page sympathetically portrayed a flag-bearing revolutionary soldier in rays of sunshine as “The Dawn of a New Era.”[119]

The troubled early years of the republic seemed to validate the negative views of China in the local press. The country was being depicted as so corrupt, badly administered, and militarily incompetent that Asians were not capable of forming a stable polity.[120] By the late 1930s, even while internal strife and Japanese invasions plagued the new republic, China seemed to be adopting Western models of modernization as it moved from its “stagnant” past into a future where democracy and possibly Christianity would play prominent roles. A few days after the opening of the 1936 carnival village, the Vancouver News Herald interviewed Mrs. Kiang Kang hu, “the personification of the utmost in feminine emancipation in any country” and wife of Dr. Kiang Kang-hu. She asserted that women were fighting for their “social and political freedom,” and were making progress in Shanghai and Hong Kong, even in the business world.[121] However, because of immigration barriers, she deplored the lack of opportunities for Chinese-born female students in Canada. Likewise, on 6 August 1936, Dr. T.Z. Koo told 400 members of the Student Christian Movement that “the whole mental outlook of China has changed since the revolution of 1911,” a message he repeated at the carnival village two days later.[122]

Chinese Vancouverites may even have ruefully concluded that there was more progress in the old country than in Canada. Some members of the carnival organizing committee, such as Seto More, President of the Chinese Benevolent Association, actively pushed back against the discrimination faced by the Chinese community during the Victoria School strike and the Anti-Segregation Movement of 1922.[123] Again, as the carnival village was still attracting record crowds, the Native Sons of Canada raised a familiar cry at their annual convention in Vancouver. They were “utterly opposed to further influx of Orientals into this country.”[124] More concrete forms of discrimination against those already in Canada continued. Early that September, nearly 2000 Chinese traders signed a petition protesting “vegetable dealers being interfered with by government inspectors,” even though the traders argued they were peaceable citizens.[125] Still, even as most public denunciations of Chinese Canadians by the mid-1930s had diminished considerably, by 1937 they were replaced with sympathy for China coupled with more discrimination/recrimination against Japanese Canadians.[126]

Even from the early days of Vancouver’s history, however, Chinese Canadians had found allies among some influential Anglo Canadians to develop “multicultural, transnational spaces of politics and law.”[127] In 1896, Li Hongzhang asked Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, who had argued that there was enough land in Western Canada for all, “Do not abandon us.” In the House of Commons, Joly said he wanted “to dispel that dark cloud which is hanging over the reputation of the countrymen of the Viceroy who was welcomed so heartily to this country.”[128] As Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia in 1900, however, Joly modified his public position.[129] Fortunately, a few other voices supported Joly’s original views. C.A. Colman argued that based on his extensive contact with Chinese people in California, South China, and British Columbia, “as far as I can judge, the Chinese are addicted to opium in about the same proportion as white men are addicted to the use of intoxicating liquors.”[130] On 9 February 1911, at the meeting of the synod of the Anglican diocese of New Westminster, Rev. G. Fiennes-Clinton, vicar of St. James Vancouver, was greeted with “hearty applause” when he argued that “as Christian people, we should welcome, within reasonable limitations, the presence of Orientals […] To despise and look down upon them is utterly unchristian.”[131] However, he also warned his listeners that negative Christian attitudes towards Asians in Canada could impede missionary efforts to save the Asian population abroad from “heathenism,” not the first clergyman to leaven altruism with a dose of pragmatism.[132]

The 1936 carnival is another example of support for Chinese business ventures from Anglo Vancouverite business circles, a phenomenon that went back at least three decades.[133] Of the 96 names of “contributors and merchants” who made the publication of the carnival pamphlet possible, through donations or advertising, over half (50) had mostly Euro-Canadian surnames, not Chinese. These included a member of the BC Legislative Assembly, a King’s Counsel, a downtown trucking company, two insurance and investment firms, a plumber, a wholesale company, an automobile repair company, two printing companies, a sporting goods store, a stationer, and a boot and shoe manufacturer.[134]

Conclusion

Was the 1936 carnival a success for the people who staged it? In financial terms, seemingly not. The organizers pleaded successfully with the City near the end of the original three-week celebration for a two-week extension in order to avoid a deficit of $25,000.[135] But what about in social, political, and psychological terms? Any positive impressions that the carnival or the Chinese community’s efforts might have made on Vancouver’s Anglo spectators in 1896, 1901, and 1912 may have been evanescent bubbles, at least in the short term. By the 1930s, individuals and organizations expressed more esteem for Chinese Canadians. Vancouver’s Chinese people were much less alone and facing a much less implacable wall of Anglo Vancouverite hostility.[136] If the press, the politicians, and the pulpit were arrayed against them, they still had allies within these pillars of discrimination whose efforts helped slowly to change public attitudes.

What did it mean for the first three generations of Chinese people to overcome the message that they did not belong in a Vancouver dominated by the values of a white Anglophone population in the early twentieth century? One element of belonging was constituted by how Chinese Vancouverites worked to resist internalizing the messages of inferiority directed at them. The other important component was that white Vancouverites began discarding the discourse of their own superiority. Ephemeral as the Chinese arches at four brief public festivals in Vancouver were, they transmitted positive and culturally reinforcing public messages of agency and identity — psychological and iconic counterparts to the ways that Chinese farmers and merchants resisted anti-Asian policies against them.[137] Far from being helpless victims, the members of the Chinese community here, as elsewhere, were “alive, active and responsive.”[138] They stood up for themselves and asserted that Chinese Vancouverites belonged in Vancouver. As many persecuted minorities have found, allies help to reinforce agency. By 1936, increasingly positive representations of the Chinese Canadians from their friends in the white community advocated the same message of inclusiveness. That combination amounted to a cultural shift for both communities, a small but important nudge towards the full meaning of belonging.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge a great debt of thanks to the very helpful comments of the JCHA’s anonymous reviewers.

Biographical note

FRANK ABBOTT taught Canadian, Chinese, and European history at Kwantlen Polytechnic University from 1988 to 2015. In retirement he continues to pursue independent research.

Notes

-

[1]

“Jubilee Has Brought Big Business Gain,” Daily Province, July 27, 1936; “Tourist Flood Near Record,” Daily Province, August 6, 1936; and “How Jubilee Aids Vancouver,” Vancouver Sun, August 1, 1936.

-

[2]

“Mace for Vancouver,” Vancouver Sun, August 19, 1936.

-

[3]

“Japanese Jubilee Show,” News-Herald, August 7, 1936.

-

[4]

“’Sun Risen From East’ Mayor’s Indian Name,” Daily Province, August 6, 1936.

-

[5]

“No Time to Make Shirley Temple Indian Princess,” News-Herald, August 10, 1936.

-

[6]

“65,000 People Have Seen the Chinese Carnival to date,” Advertisement, Vancouver Sun, August 25, 1936. Vancouver’s population ranged between 247,000 in 1931to 275,000 in 1941. Government of British Columbia, “British Columbia Municipal Census Populations 1921–2011.”

-

[7]

“Chinese Show Gives Jubilee Bright Color,” News-Herald, July 13, 1936; “Chinese Royal Arch Nears Completion,” Vancouver Sun, July 11, 1936.

-

[8]

Quene Yip, Vancouver Chinatown: Specially Prepared for the Vancouver Golden Jubilee 1886–1936 (Vancouver: Pacific Printers, 1936), 40–1.

-

[9]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 40–1.

-

[10]

Frank Abbott, “Cold Cash and Ice Palaces: The Quebec Winter Carnival of 1894,” Canadian Historical Review 69, no. 2 (June 1988): 167–202.

-

[11]

“Wild About Arches,” photographs from the City of Vancouver Archives. https://vanasitwas.wordpress.com/2014/08/18/wild-about-arches/, <viewed 30 January 2019>. The other arches: Dominion Day, 1888; visit of the Earl of Aberdeen,1898; return of soldiers from the Boer War, 1900; visit of Edward, Prince of Wales, 1919, and the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation, 1927.

-

[12]

Royal British Columbia Museum, Archives: Item E–01926, “Second Chinese Arch On Cormorant Street Erected For Visit Of The Earl Of Dufferin, Governor-General Of Canada;” item A–02846, “Chinese arch on Store Street, Victoria; erected for the visit of the Governor General, the Marquess of Lorne;” item A–04439, “Nanaimo; Chinese Arch,” <viewed 12 April 2019>.

-

[13]

“Arches – Gateways to Past and Present Chinatown,” Victoria’s Chinatown, http://chinatown.library.uvic.ca, <viewed 13 April 2019>.

-

[14]

Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China, Volume 4, Part II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 142; Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, Living Architecture: Chinese (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1971), 59, 83.

-

[15]

W. Kuyper, The Triumphant Entry of Renaissance Architecture into the Netherlands. The Joyeuse Entrée of Philip of Spain into Antwerp in 1549. Renaissance and Mannerist architecture in the Low Countries from 1530 to 1630 (Alphen aan de Rijn: Canaletto, 1994).

-

[16]

Guy Debord, The Society of Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014), 2.

-

[17]

E.A. Heaman, The Inglorious Arts of Peace (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 284, 312-3.

-

[18]

Peter S. Li, The Chinese in Canada, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), xii. See also Patricia Roy, The Oriental Question: Consolidating a White Man’s Province 1914–1941 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003), 44–53.

-

[19]

Edgar Wickberg, From China to Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982), 180.

-

[20]

Lisa Rose Mar, Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada’s Exclusion Era, 1885–1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010).

-

[21]

Robert A.J. McDonald, Making Vancouver: Class, Status, and Social Boundaries, 1863–1913 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1996), 61.

-

[22]

“Chinese Play Park to Open,” Vancouver Sun, March 23, 1928.

-

[23]

Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 152–5.

-

[24]

Roy, Oriental Question, 125–30.

-

[25]

Li, The Chinese in Canada, 142–3; Xiau Xu, “Data shows an increase in anti-Asian hate incidents in Canada since onset of pandemic,” Globe and Mail, September 13, 2020. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/british-columbia/article-data-shows-an-increase-in-anti-asian-hate-incidents-in-canada-since/

-

[26]

City of Vancouver, “Administrative Report: Historical Discrimination Against Chinese people in Vancouver,” 20 October 2017. Vancouver Public Library.

-

[27]

Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 155–58. For changing European attitudes to China over four centuries, see David Mungello, The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800 (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999).

-

[28]

Peter Ward, White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy Towards Orientals in British Columbia, 3rd Ed. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002). For similar attitudes in the United States, see Robert G. Lee, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999).

-

[29]

Roger Chartier, Cultural History: Between Practices and Representations, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988), 6.

-

[30]

For a later period, see Wing Chung Ng, The Chinese in Vancouver 1945–80: The Pursuit of Identity and Power (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1999).

-

[31]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown; Kay J. Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875–1980 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991), 156–7; Wickberg, From China to Canada, 179–80; Patricia Roy, The Oriental Question: Consolidating a White Man’s Province 1914–1941 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003), 125–30.

-

[32]

For Kiang at McGill, see Mary Zhang, “Principal Sir Arthur Currie and the Department of Chinese Studies at McGill,” https://fontanus.mcgill.ca/article/view File/253/288, <viewed 28 March 2019>. See also Wickberg, From China to Canada, 180.

-

[33]

“Chinese Parade – Million Dollar Festival Opens,” Vancouver Sun, July 18, 1936.

-

[34]

“Million-Dollar Chinese Exhibit and Hawaiian Troupe Here for Jubilee,” Daily Province, July 14, 1936.

-

[35]

“Beauty of the Orient Expressed in Many Ways at Chinese Carnival,” Vancouver Sun, July 23, 1936.

-

[36]

Laifong Leung, “Literary Interactions between China and Canada: Literary Activities in the Chinese Community from the Late Qing Dynasty to the Present,” Journal of American-East Asian Relation 20 (2013): 141. See also Him Mark Lai, et al., Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910–1940 (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2014); https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/assets/LRN_TheWritingOnTheWall_TeachersGuide-final.pdf, < viewed 18 July 2019>.

-

[37]

Paul Yee, Saltwater City: An Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2006), 9.

-

[38]

Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 79.

-

[39]

Leung, “Literary Interactions,” 140.

-

[40]

Samuel C. Chu and Kwang-Ching Liu, Li Hung-chang and China’s Early Modernization (Armak, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1994).

-

[41]

Keith Walden, Becoming Modern in Toronto: The Industrial Exhibition and the Shaping of a Late Victorian Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 151; Esson M. Gale, “President James Burrill Angel’s Diary: As United States Treaty Commissioner and Minister to China, 1880–1881,” Quarterly Review of the Michigan Alumnus (1943): 204.

-

[42]

City of Vancouver Archives (CVA), 960-1-598-A-1. Undated Chinese letter with English translation. “Vancouver Received the Ambassador of the Emperor of China in a Fitting Manner,” Daily World, September 14, 1896.

-

[43]

“The Chinese Viceroy,” Daily World, September 5, 1896; “Li Hung Chang,” Daily World, September 8, 1896.

-

[44]

Wickberg, From China to Canada, 73.

-

[45]

“Embassador (sic) Li Hung Chang,” Sacramento Daily Union, September 14, 1896.

-

[46]

McDonald, Making Vancouver, 1863–1913, 215.

-

[47]

“A Great Statesman,” Daily World, 14 September 14, 1896.

-

[48]

“Embassador Li Hung Chang.”

-

[49]

Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 29; Li, The Chinese in Canada, xii. Whether Victoria’s Chinatown was really a hermetically sealed ghetto, see Patrick Dunae et al., “Making the Inscrutable, Scrutable: Race and Space in Victoria’s Chinatown, 1891,” BC Studies 169 (Spring 2011): 51–80. See also Wickberg, From China to Canada.

-

[50]

“Welcome to Vancouver,” Daily World, September 12, 1896.

-

[51]

“At the Capital – Joly Replies to Maxwell on the Chinese Question,” Daily World, September 10, 1896; McDonald, Making Vancouver, 1863–1913, 206; Robert J. McDonald and Jeremy Mouat, “Maxwell, George Ritchie,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. XIII (1901-1910), <viewed 21 May 2019>. For reaction to Maxwell’s speech see Patricia Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigration, 1858–1914 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989), 97.

-

[52]

“Maxwell Speaks,” Daily World, September 18, 1896; Roy, A White Man’s Province, 97–99.

-

[53]

“McInnes Speaks,” Daily World, October 3, 1896; Roy, A White Man’s Province, 201, passim.

-

[54]

“Li Hung Chang Talks,” Daily World, September 4, 1896.

-

[55]

McDonald, Making Vancouver, 99.

-

[56]

“Li Hung Chang Talks.”

-

[57]

“Farewell to Canada,” Daily World, September 16, 1896.

-

[58]

McDonald, Making Vancouver, 153–174.

-

[59]

“Miles of Decoration,” Daily World, September 23, 1901; “The Duke’s Thanks,” Daily World, October 1, 1901.

-

[60]

“Welcome of Vancouver – How This Loyal City Has Arranged To Receive Royalty,” Daily World, September 28, 1901.

-

[61]

Joseph Pope, The Tour of their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York Through the Dominion of Canada in the Year 1901 (Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1903), 89; Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace, The Web of Empire: A Diary of the Imperial Tour of their Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in 1901 (London: MacMillan, 1902), 397. The British account also acknowledged that the Chinese communities in Melbourne and Perth, Australia, and in Dunedin, New Zealand had also erected welcoming arches for the royal tour. 120, 321–2; See also Harry Price, The Royal Tour 1910: Being a Lower Deck Account of Their Royal Highnesses, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York’s Voyage Around the British Empire (Exeter: Webb & Bower, 1980).

-

[62]

Pope, Tour of their Royal Highnesses, 1901, 240.

-

[63]

“The Chinese Way,” Daily World, September 30, 1901.

-

[64]

“City in Festive Attire for Royalty’s Visit,” Daily World, September 16, 1912; “Cheering Thousands Greet Honored Guests,” Daily World, September 18, 1912.

-

[65]

“For the Sake of National Unity, Be Canadian!” Daily World, September 17, 1912.

-

[66]

Roy, Oriental Question, 56–7; 76–7.

-

[67]

John Atkin, Strathcona: Vancouver’s First Neighbourhood (Vancouver and Toronto: Whitecap Books, 1994), 52.

-

[68]

Vancouver Golden Jubilee Official Pictorial Souvenir Program, n.d., n.p. CVA AM1519, 1936–65.

-

[69]

“Golden Jubilee Supplement,” Daily Province, May 21, 1936, 43.

-

[70]

Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 156–8.

-

[71]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 7.

-

[72]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 33.

-

[73]

Mar, Brokering Belonging, 58.

-

[74]

“Chinese Students Tackle Varsity at Jones Park Tonight,” The Sun, May 29, 1933. See also Fred Hume, “Quene Yip: UBC’s First Chinese-Canadian Sports Star,” The Point, Varsity Volume (February 2008); https://www.bcsportshalloffame.com/inductees/inductees/bio?id=60&type=team, <viewed 16 January 2019>. Ron Hotchkiss, Diamond Gods of the Morning Sun, The Vancouver Asahis Baseball Story (Victoria, BC: Friesen Press, 2013); Pat Adachi, Asahis, A Legend in Baseball: A Legacy from the Japanese Canadian Baseball Team to Its Heirs (Etobicoke, ON: Asahi Baseball Organization, 1992).

-

[75]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 23.

-

[76]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 15–17.

-

[77]

Timothy J. Stanley, “By the Side of Other Canadians: The Locally Born and the Invention of Chinese Canadians,” BC Studies 156/157 (Winter 2007): 109–39; Roy, Oriental Question, 101.

-

[78]

Denise Chong, The Concubine’s Children: Portrait of a Family Divided (Toronto: Penguin, 1995).

-

[79]

David Chuenyan Lai, Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1988), 60.

-

[80]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 25; Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown,147–151. For a recently rediscovered Chinatown photographer, see Catherine Clement, Through a Wide Lens: The Hidden Photographs of Yucho Chow (Vancouver: Chinese Canadian Historical Association of British Columbia, 2020).

-

[81]

Paul Yee, “Business Devices from Two Worlds: The Chinese in Early Vancouver,” BC Studies 62 (Summer 1984): 47.

-

[82]

For Chinese laundries see Paul Yee, “Chinese Businesses in Vancouver 1886–1914,” (MA Thesis, University of British Columbia, 1983), 33–37. See also John Jung, Chinese Laundries: Tickets to Survival on Gold Mountain (N.P.: Yin & Yang Press, 2007).

-

[83]

Wickberg, From China to Canada, 184–185.

-

[84]

CVA Series 20-16-D-5 folder 03; Roy, Oriental Question, 150–54; Wickberg, From China to Canada, 182–3.

-

[85]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 37.

-

[86]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 19; Timothy J. Stanley, “Schooling, White Supremacy, and the Formation of a Chinese Merchant Public in British Columbia,” BC Studies 107 (1995): 20–27; Wickberg, From China to Canada, 171–172.

-

[87]

Leung, “Literary Interactions,” 143.

-

[88]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 19.

-

[89]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 20. For the importance of churches see Wickberg, From China to Canada, 172.

-

[90]

Jiwu Wang, “His Dominion” and the “Yellow Peril” (Waterloo, ON: The Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion and Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2006), 31.

-

[91]

Union of Concerned Scientists, https://www.ucsusa.org/clean-energy/coal-and-other-fossil-fuels/coal-air-pollution, <viewed 24 May 2019>.

-

[92]

“Case Study: Bawtry Gas Works,” https://www.environmentlaw.org.uk/rte.asp?id=228, < viewed 24 May 2019>.

-

[93]

“Fire Insurance Plans of the City of Vancouver, British Columbia,” vol. 7. CVA.

-

[94]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 23–25; Wickberg, From China to Canada, 121–22, 172–73; Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 79–80, 84–5, 104, 143, 147.

-

[95]

CVA 177-3-513-B-8. Vancouver Golden Jubilee Committee, “Correspondence.”

-

[96]

CVA 177-8-513-B-8. Vancouver Golden Jubilee Committee, “Correspondence, March 1936.”

-

[97]

CVA 177-8-513-B-8. Vancouver Golden Jubilee Committee, “Correspondence, May 1936.”

-

[98]

CVA: AM 1519, “Pamphlets, 1936–62.”

-

[99]

“Chinese Parade - Million Dollar Festival Opens,” Vancouver Sun, July 18, 1936.

-

[100]

“Chinese Parade.”

-

[101]

“Old China’s Welcome to Young Vancouver,” Vancouver Sun, July 20,1936.

-

[102]

“Mayor M’Geer Officiates at Show Opening,” News-Herald, July 20, 1936.

-

[103]

Pat Terry, “$1,000,00 Art From China,” Vancouver Sun, July 14, 1936.

-

[104]

“Gay Parade Marks Chinese Village Opening,” Daily Province, July 18, 1936.

-

[105]

“Chinese Show Again Magnet to Big Crowd,” News-Herald, July 21, 1936; “Chinese Carnival to Continue,” Vancouver Sun, August 8, 1936.

-

[106]

James Dyer, “Old China’s Welcome to Young Vancouver,” Vancouver Sun, July 20, 1936.

-

[107]

“The Chinese Art Exhibit,” Vancouver Sun, July 29, 1936.

-

[108]

“Chinese Show – Efforts to Keep Collection to Fail,” News-Herald, 1 September 1, 1936.

-

[109]

Kiang Kanghu to Mayor G.G. McGeer, 24 August 1936. CVA AM 177 513-C-2 fld. 7.

-

[110]

CVA. AM5454-: Arch P54, 29 May 1939.

-

[111]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 27–29. On the GMD, see Wickberg, From China to Canada, 162–63, and Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown, 150-51.

-

[112]

Pat Terry, “Canada’s Chinese Election,” Vancouver Sun, September 2, 1936.

-

[113]

Stanley, “By the Side of Other Canadians,” 109.

-

[114]

Wayson Choy, The Jade Peony (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 1995).

-

[115]

Leung, “Literary Interactions,” 145. On May 4, see Immanuel C.Y. Hsü, The Rise of Modern China, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 493–513; Vera Schwarcz, The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Lin Yu-sheng, The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Anti-Traditionalism in the May Fourth Era (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1979); Mark Alvin and G. William Skinner, eds., The Chinese City Between Two Worlds (Stanford: University of California Press, 1974); Chow Tse-tsung, The May Fourth Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964).

-

[116]

Hsü, Rise of Modern China, 361–86; Jane Leung Larson, “An Association to Save China, the Baohuang Hui: A Documentary Account,” China Heritage Quarterly 27 (September 2011); Wickberg, From China to Canada, 74-76

-

[117]

City of Vancouver and the Chinese Canadian Historical Society, Historic Study of the Society Buildings in Chinatown (July 2005), 16.

-

[118]

“Revolutionaries Here From China,” Daily World, October 16, 1911.

-

[119]

Daily World, 13 February 13, 1912.

-

[120]

Patricia E. Roy, “Images and Immigration: China and Canada,” Journal of American-East Asian Relations 20 (2013): 118–123.

-

[121]

“Chinese Women Making Great Strides Toward Freedom,” News Herald, July 21, 1936.

-

[122]

“New China – Whole Mental Outlook Changed,” Vancouver Sun, August 8, 1936.

-

[123]

Lisa Rose Mar, Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada’s Exclusion Era 1885–1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 46, 80–84, 91, 94; Stanley, “Schooling, White Supremacy, and the Formation of a Chinese Merchant Public in British Columbia,” 3–29; “Bringing Anti-Racism into Historical Explanation: The Victoria Chinese Students’ Strike of 1922–3 Revisited,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 13 (2002): 141–65. See also Roy, Oriental Question, 37–8.

-

[124]

“‘Prohibit Orientals’ – Native Sons,” Vancouver Sun, August 13, 1936.

-

[125]

“Chinese Protest – Complain of Interference by Inspectors,” News Herald, September 10, 1936.

-

[126]

Roy, “Images and Immigration,” 128.

-

[127]

Mar, Brokering Belonging, 14. See also Mar, “Beyond Being Others: Chinese Canadians as National History,” BC Studies 156/157 (Winter 2007): 13–34.

-

[128]

“Joly Replies to Maxwell.”

-

[129]

J.I. Little, Patrician Liberal: The Public and Private Life of Sir Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière 1829–1908 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 209–10, 229–30.

-

[130]

C.A. Colman, “Maxwell and the Chinese,” Daily World, 2 October 2, 1896.

-

[131]

“Favor of Chinese Coming in Here,” Daily World, February 9, 1911.

-

[132]

“Would Welcome Orientals Here,” Daily World, February 10, 1911. See also Wang, “His Dominion” and the “Yellow Peril,” 87–120.

-

[133]

Paul Yee, “Business Devices from Two Worlds: The Chinese in Early Vancouver,” BC Studies 62 (1984): 60–63.

-

[134]

Yip, Vancouver Chinatown, 44–5.

-

[135]

“Chinese Carnival Faces Heavy Loss,” Daily Province, August 7, 1936; “Chinese Carnival to Continue,” Vancouver Sun, August 8, 1936.

-

[136]

Roy, Oriental Question, 237.

-

[137]

Roy, Oriental Question; McDonald, Making Vancouver; Mar, Brokering Belonging.

-

[138]

Charles P. Sedgwick, “The Politics of Survival: A Social History of the Chinese in New Zealand,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Canterbury, New Zealand, 1982), 26.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

FRANK ABBOTT a enseigné l’histoire du Canada, de la Chine et de l’Europe à la Kwantlen Polytechnic University de 1988 à 2015. Maintenant à la retraite, il continue à mener des recherches indépendantes.