Résumés

Abstract

The educational histories of mid-nineteenth century British-Métis students illuminate the transnational travels of British-Métis students and their roles in reifying and challenging British-imperial norms about race, class, and gender in the British Empire. In this paper, photographic and object-based artifacts are interwoven with family correspondence and other archival documents to explore the complexity of British-Métis children’s life stories and the extensive connections between elite British-Métis fur-trade families to kith and kin in North America and Britain. Studio portraits of British-Métis children and their gravesites represent both the best and the worst outcomes of elite educations for British-Métis children and youth. The studio portraits represent the norms of British middle-class respectability that elite British-Métis students learned at colonial and metropolitan schools as part of the imperial project. Gravestones and burial sites, on the other hand, reflect the possibilities and realities of death and trauma that were intertwined with fur-trade children’s boarding school education. By traveling to and living in Britain, British-Metis children challenged metropolitan understandings of the place and role of Indigenous peoples in the Empire and left their marks in Britain in their lives and their deaths.

Résumé

L’histoire de l’éducation des écoliers métis-britanniques du XIXe siècle éclaire les voyages transnationaux de ces enfants et leur rôle dans la réification et la contestation des normes impériales britanniques portant sur la race, la classe et le genre. Dans cet article, des artefacts, photographies et objets, s’associent à la correspondance familiale et à d’autres documents pour explorer la complexité des histoires de vie des enfants métis-britanniques et les liens étroits qu’entretenaient les familles de traiteurs de fourrures métis-britanniques avec leurs proches et leur parenté en Amérique du Nord et en Grande-Bretagne. Les photographies prises en studio des enfants métis-britanniques et leurs sépultures représentent le meilleur et le pire de l’éducation de l’élite des enfants et des jeunes métis-britanniques. La photographie de studio représente une norme de respectabilité de la classe moyenne britannique que les écoliers métis-britanniques assimilaient dans les écoles coloniales et métropolitaines en tant que partie intégrante du projet impérial. Les pierres tombales et les sites funéraires, de l’autre côté, traduisent les possibilités et les réalités de la mort et du traumatisme qui étaient indissociables de l’éducation des enfants dans les pensionnats de la traite des fourrures. Lorsqu’ils se rendaient en Grande-Bretagne pour y vivre, les enfants métis-britannique mettaient au défi les conceptions de la place et du rôle des peuples autochtones dans l’Empire et, par leur vie et leur mort, imprimaient leur marque en Grande-Bretagne.

Corps de l’article

In January 1865, Mary Sinclair Christie wrote from her home at Fort Edmonton to the schoolmistress in charge of her daughters’ education at the Red River Settlement. Mary’s older daughters, Annie and Lydia, were students at the Oakfield Establishment for Young Ladies, a boarding school run by headmistress Matilda Davis.[1] In her letter, Mrs. Christie informed Miss Davis that she had made arrangements for her sister-in-law in Edinburgh to ship supplies for Annie and Lydia directly to Red River.[2] She also noted that it was time for her youngest daughter, Mary Ann, to join her older sisters and her cousin Ann Mary Christie at the Miss Davis School.[3] Mrs. Christie advised Miss Davis that “we intend sending Mary to your Academy next summer,” and closed the letter by remarking on a scarlet fever epidemic in the area.[4] Sadly, six-year-old Mary Ann succumbed to the scarlet fever epidemic less than two weeks later, and never joined her sisters at the Miss Davis school at Red River, nor on their journeys to colonial Québec, Ontario, or to Britain.[5] The other Christie children, however, are examples of Métis students whose life histories and educational travels spanned the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) territories, the Canadian colonies, and Britain.[6] These Métis students’ mobility within the British Empire challenged imperial understandings of the place and role of Indigenous peoples in the Empire, and both drew on and replicated the extensive trans-Atlantic kin ties that connected white and Métis families on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Parents sent their children to school to learn reading, writing, Christianity, and the social norms of British middle-class respectability that they were expected to enact in their roles as colonial elite. Children were taught in their homes, in parish schools, and sent away to boarding schools in Oregon, Red River, the Canadian colonies, and Britain.

I explore these students’ education within an analytical framework that incorporates British-Métis histories on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean to explore the transnational movements, kin ties, and multicultural identities common to these childhoods.[7] This approach highlights the social class, kinship, and hybrid cultural identities that tied these families together as a mid-nineteenth-century fur-trade elite. Moreover, putting British-Métis children at the centre of the study challenges a historical literature that has tended to focus on Indigenous mothers and European fur-trade fathers, and expands our understanding of pre-residential-school era education.

In this paper I consider the challenges of locating these students’ histories in textual archival sources. I also demonstrate how photographs, burial sites, and gravestones can illuminate aspects of these fur-trade children’s and youths’ transnational and educational histories that are often obscured in the fur trade records, correspondence, and genealogical sources that are generally the core sources for Métis historiography.[8]

British-Métis Families, Education, and Privilege

Families like the Christies generally self-identified as “natives of the country,” “HBC people,” or “English halfbreeds.”[9] These were local terms that acknowledged hybrid European and Indigenous cultural heritages. I tenuously use the term British-Métis in this study to describe a specific group of mid-nineteenth century Métis families, but I do so with the understanding that naming and identity are complex.[10] There is no one, agreed-upon term to describe this group of elite Indigenous fur-trade families, either then or now.[11] The British-Métis families considered in the paper, like the Christies, included Cree and Anishinabeg grandmothers and great-grandmothers as well as Scottish, English, and Orcadian fathers and grandfathers. They had close ties to the Hudson’s Bay Company, were nominally and often devoutly Anglican or Presbyterian, and enjoyed elite socio-economic status conferred by their fathers’ and grandfathers’ positions as HBC officers. These fur-trade families were connected by social status and kin ties that stretched from Victoria to the British Isles, they sometimes travelled to Britain, and often identified as British subjects. Their multicultural identities informed how they understood their place in the colonial HBC territories and in Britain. Most importantly, perhaps, they understood themselves simultaneously as “natives of the country” and as British subjects.

The “British” in “British-Métis” recognizes these families’ British roots, socio-economic privilege, Protestant religions, and their claims as British subjects. “Métis” acknowledges their First Nations and Métis ancestries and their connection to the Métis Nation.[12] British-Métis families claimed their elite status through both their Indigenous and British ancestries.[13] British-Métis men, women, and children had specific understandings of their identities and roles in the British Empire that did not align with those of their French-Métis cousins.[14] These understandings and their histories have been marginalized in recent scholarship on mid-nineteenth-century Métis history that tends to centre buffalo hunting brigades, cross-border Métis communities, Catholicism, labourers, and Métis nationalism.[15] These families’ integration into the colonial elite as British-Métis people reflects a specific moment in the histories of the Métis, the fur trade, colonial Canada, and the British Empire. This historical moment began with the HBC monopoly in 1821, initiating a period during which British-Métis families leveraged their numbers, socio-economic privilege, fur-trade kin networks, and British heritage to establish themselves as members of the colonial elite. This moment ended with the dispossession of the Métis in Manitoba from the 1870s and the influx of settlers to western Canada beginning in the 1890s.[16]

These British-Métis families interwove their multicultural identities into daily lives where Indigenous languages, skills, and traditional knowledge existed alongside British-style schooling, societal norms, and Christianity. Matilda Davis was a sought-after educator in part because her own transnational life history as a British-Métis fur-trade student and her governess training in London made her a uniquely-qualified girls’ teacher in the HBC territories.[17] Her school was also popular because, in acknowledgment of her and her students’ Indigenous heritage and the realities of childhoods often spent at remote fur-trade posts, Davis taught a standard British-style curriculum alongside Métis and First Nations beadwork and sewing. Students in the dormitories spoke multiple languages, and the girls both sewed and wore moccasins and hide mitts. The multicultural and elite education offered at the Miss Davis school incorporated British norms and values while adapting a British curriculum to meet the practical needs of life in the HBC territories.[18] Although the Davis school was somewhat unusual in offering such an overtly blended education, her approach to educating primarily British-Métis students illustrates the ways that her British-Métis children and youth students integrated their Métis, First Nations, and British heritages into their daily lives.

British-style education, however, was central to the cohesiveness and success of British-Métis fur-trade families, and the privilege afforded to these families allowed them to invest significantly in education for their children. In particular, they had the means to pay to send their children away from their remote homes at fur trade posts to access a better-quality British-style education at schools in larger centres. The decisions that parents made about education were influenced by gender, with sons’ educations often being prioritized over daughters’; by children’s personality or perceived intelligence; or by birth order in relation to a father’s advancement in his career. By and large, however, families like the Christies prioritized educating their children and made significant financial investments in their studies. A good education would, in theory, result in good jobs for their sons and good marriages for their daughters.[19]

Although Mary Ann Christie died before she left for boarding school, all her siblings and her Christie cousins were sent away from their homes at HBC fur trade posts to attend school. Christie sons attended The Nest Academy in Scotland, a boarding school for boys, and then sometimes went on to college.[20] Christie daughters attended the Miss Davis School. Annie and Lydia Christie left the Miss Davis school to attend finishing school in Québec, and Lydia and her cousin, Emma, both travelled to Britain as young women.[21]

The Christie family’s focus on education and on transnational travels to access quality education was common amongst upper- and middle-class families in colonies throughout the British Empire; parents of white and mixed-ancestry children sent their offspring away from home to access the best education possible.[22] Imperial children were taught similar lessons about British class, gender, and religious norms in British-style schools in both the colonies and in Britain itself. Across the British Empire, education was used to transmit British social norms and standards of behaviour to boys and girls.[23] These lessons in both academics and middle-class respectability were meant to equip colonial children like the Christie cousins for success in colonial and metropolitan settings. [24] These educations, however, also allowed British-Métis families to reproduce and reify their class privilege in the HBC territories through their children’s subsequent employment in and marriage to the colonial elite.

Accessing evidence of these students’ educational histories in North American and British archives is a challenge. British-Métis students’ histories are disadvantaged in the colonial archive by both their Indigenous heritage and their age.[25] Their elite social status, however, allowed their parents to fund their educations which, in turn, produced family correspondence to and from students who were away at school, report cards, bills, records of travel, photographs, and other documents. Still, the archival record of the students’ life histories is at best fragmentary. Exploring visual records and objects as historical sources provides, as Kristine Alexander notes of photos of Girl Guides, “compelling evidence of the limits of language” in the study of children and colonialism.[26] Here, I explore studio portraits, burial sites, and gravestones as sources for British-Métis students’ life histories, and interweave these sources with archival family correspondence and census records to better understand British-Métis students’ transnational educational travels to Britain, their experiences in the metropole, and the trans-Atlantic kin networks that were integral to their education.

Studio portraits, gravestones, and burial sites represent both the best and the worst outcomes of elite education for these children and youths. The studio portraits depict the norms of British middle-class respectability that elite British-Métis students were expected to learn at colonial and metropolitan schools as part of the imperial project.[27] They are also visual representations of the ways that elite British-Métis families engaged their class privilege to reproduce and reify their power in fur-trade country and beyond. Gravestones and burial sites, on the other hand, point to the death and trauma often intertwined with fur-trade children’s boarding school education. These sources expand our understanding of British-Métis students’ transnational lives and the extensive trans-Atlantic kin networks that they accessed for support and care.[28] The two case studies presented here feature a studio portrait of Lydia Christie taken in Portobello, Scotland, and the gravestone and burial site of Roderick McKenzie Jr. in Ullapool, Scotland. Interweaving visual and object sources with textual records drawn from archives in North America and Britain illustrates the inter-relatedness of transnationalism, education, privilege, and kin networks in Lydia’s and Roderick’s experiences as Métis and colonial youth in the metropole.

Transnationalism, Indigenity, and the British Empire

Historians have long recognized the centrality of mobility to Métis histories and identity. Most often, mobility has been a theoretical framework deployed by scholars to explore issues of Métis lands, social structure, borderlands communities, and nationhood in western North America.[29] British-Métis children and youth experienced mobility differently. For most, their fathers’ careers and therefore their home lives were marked by impermanence. HBC officers moved from post to post during their careers, and their families generally followed. Year-long furloughs from their jobs also meant that fathers travelled abroad, either with or without their families. Children’s travels as students, then, were only one part of the mobility that characterized the careers and life paths of British-Métis families, but they were also part of a tradition of Métis mobility in a larger sense. Moreover, this mobility enfolded them into the imperial project in ways that were specific to children of the Empire.

The Christie cousins are only some of the British-Métis students who were incorporated into an empire-wide project of education aimed at “civilizing” mixed-ancestry children. British-Métis children and youth lived their lives at the intersections of colonial specificities of the fur trade, an emerging settler colonial society in the Hudson’s Bay Company territories after 1821, and larger British imperial anxieties about race, gender, power, and “mixedness.” These anxieties often found expression in optimism for and concerns about children of the British Empire. Simon Slight and Shirleene Robinson argue that both white and Indigenous children were “central to the imperial project, burdened with its hopes and anxieties.”[30] Mixed-descent imperial children in particular were the embodiment of the “dual interests” of colonial and imperial race politics as they aligned in “governing native races and improving the white race.”[31] Imperial children’s bodies and minds were places to exercise imperial anxieties about gender, race, class, and sexuality.[32] Parents, administrators, educators, missionaries, and entrepreneurs all had their own visions for the roles that children should occupy in the Empire, leaving imperial children with limited agency over how their lives, bodies, and minds were intertwined with the imperial project. As mixed-ancestry children of the British Empire, British-Métis students were part of this interplay of colonialism and resistance that shaped colonial and metropolitan understandings of race, place, gender, and class.

They were also entwined in the interchange of people and ideas between Britain and its colonies. The mobility of people between Britain and the colonies was central to the “mutually constitutive Empire”; these movements and knowledge circuits transcended national boundaries and national histories.[33] People, ideas, and material culture circulated through the Empire (and beyond), and in doing so reformed imperial and colonial knowledges. Explorations of the points at which intimacy and mobility intersected, however, have reinforced the assumption that “in the context of empire, the local is that which does not move and the native is the stationary object on whom intimacy is bestowed, visited and forced.”[34] Both nineteenth-century contemporaries and later historians assumed that separation between the metropole and colonies, and between Indigenous peoples and Britons, was inherent to the British Empire.[35]

British-Métis students, however, were not static, stationary, or separate from the history of the British metropole. Their educational histories demonstrate that Indigenous people were not solely local or stationary in the nineteenth-century British Empire. Jane Lydon and Jane Carey argue that Indigenous mobility and transnational networks were “shaped [and] constituted through engagement with Indigenous peoples’ actions, ambitions and orientations.” Considering British-Métis children and youth as transnational actors shows that Indigenous people could be “part of, or exploit, transnational or imperial networks.” [36]

These Indigenous metropolitan histories have been written out of the historical record and the collective memory of the British Empire. In his study of Indigenous presence in London, Coll Thrush argues that “Indigenous people who remain in or move to urban places are all too often portrayed, if at all, as somehow out of place, and that out-of-place-ness is all too easily trans-formed into absence. The result is a blindness read back onto the past from the present, an inherited silence where history should be.”[37] Thrush demonstrates that Indigenous peoples have a long and sustained history in London, where both their physical presence and their daily interactions with Londoners challenged the supposed separation between colony and metropole.

The British-Métis students named here are only a handful of the British-Métis children who, for more than a century, migrated from fur-trade country to metropolitan areas in the Canadian colonies and Britain to go to school. Their histories have been marginalized from both British and Canadian histories because they do not conform either to the narratives of the nation state or to understandings of Indigenous peoples as fixed and stationary in the British Empire.[38] A transnational approach to these children’s histories transcends the exclusionary focus on the nation-state and highlights the interconnectedness of the children’s kin ties to both the HBC territories and Britain. Karen Dubinsky, Adele Perry, and Henry Wu characterize transnational approaches to Canadian history as those that centre “the connectiveness of sites and how people imagined their ties to multiple locations.” Elite British-Métis students’ multi-sited life histories, trans-Atlantic travels, and kin ties exemplify such “forms of belonging beyond a simple inclusion or exclusion within a single national imaginary.” [39]

Like the men and women in Thrush’s study, British-Métis students were enmeshed in British society through their physical presence in England, mainland Scotland, and the Orkneys where they lived with and attended school alongside metropolitan Britons. Their physical presence directly challenged imperial notions of separation between metropole and colony. Some children returned to the HBC territories, but others relocated permanently and lived out their adult lives in Britain as teachers, governesses, industrialists, wives, and daughters. Studio portraits, gravestones, and burial sites provide insight into these students’ transnational travels, the gender and social norms that they learned as part of their British-style education, and the trans-Atlantic kin networks that undergirded the students’ education and facilitated their claims to space and place in Britain.

Photographs

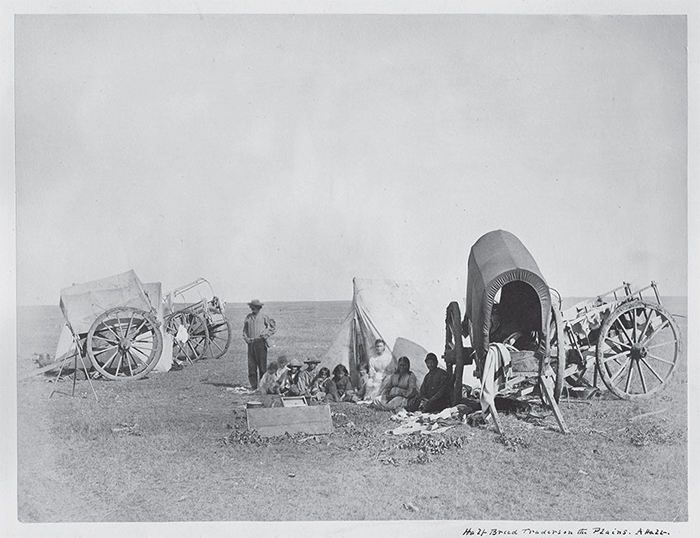

Historians use historical photographs in our work regularly, but most often these images are used uncritically to provide visual aids in the classroom, in publications, or in slide presentations. Photographs, however, can and should be read critically as historical sources. As both objects and historical texts, they provide perspectives that are often inaccessible in the written record. In the context of colonial North America, they also tend to privilege white artists and their perspectives over Indigenous-produced visual records. The images of mid-nineteenth-century Indigenous peoples that Canadians are most familiar with, for example, are paintings and photographs that were created by white male artists who visited the HBC territories in the 1820s through the 1850s.[40] According to artist and historian Sherry Farrell Racette, the Indigenous peoples in these images were “often coerced and uncomfortable subjects.”[41] The artists’ paintings and photographs share common themes about the wildness of the West and of its Indigenous inhabitants. Depictions of the Métis favour the buffalo hunt, Red River carts and freighting, and family groups (Figure 1). These images often reproduce stereotypes about Indigenous peoples and celebrate narratives of progress and nation-building.

Figure 1

Archival photographs, however, are increasingly coming under scrutiny as representations of Indigenous histories, as expressions of the settler-colonial project, and as sources that interrogate older narratives of Indigenous pasts and unsettle histories told from a Western perspective.[42] Reading photos as objects and exploring the materiality represented in the images can yield insightful results.[43] Thus far, analyses of photographs of Indigenous children in Canada by scholars like Farrell Racette and Carol Anderson have focused on residential school photography or on the photographers behind the camera.[44]

The images of mid-nineteenth century Métis peoples that are most prevalent in the archive and in family collections are posed family photos and formal studio portraits. Studio portrait photographs of British-Métis children and youth provide a different perspective on Métis history than those featuring hunting brigades on the Plains. Formal portraits of British-Métis children and youth are both objects that speak to British-Métis students’ transnational travels, and visual representations of British-Métis families’ understandings of the intersections of class, race, and gender that informed their place in colonial Canada and the British Empire.

Working with these photos is complicated. Individuals in the photos are often unnamed or not identified as Métis. Photos of women who are named only by their husbands’ names (e.g., Mrs. John Smith) pose an even greater challenge to analysis. Extensive knowledge of fur-trade and Métis genealogies and family histories is necessary to sort out the names, family and social connections, and provenance of the photos. However, unlike the Métis generally depicted in images created by visitors to the region, the Métis men, women, and children who had their “likenesses” taken were active collaborators in the images’ production. Photography scholars have explored the evolution of photographic conventions like poses, backgrounds, and props as well as the purpose and popularity of photography in the nineteenth century.[45] Commercial photographers, who catered to the general public and whose resources for elaborate studios were limited, composed studio portraits within a set of commonly-employed guidelines for portrait composition. Within these parameters, however, the subjects had considerable latitude in choosing how to represent themselves.[46]

The British-Métis children in studio portraits, or at least the adults who accompanied them to the photo studio, made choices about representation within these standard guidelines. Students or their caregivers chose their clothing and hairstyles in line with contemporary norms of class and gender, and worked with the photographer in selecting poses, groupings, and props. British-Métis students or their caretakers were thereby active participants in crafting the image they presented in the portraits. The extent to which the portraits reflected the will of students themselves likely depended on their age, their personality, and their escort. Without corresponding personal writings that describe the photo sessions, it is not possible to know the extent to which the students themselves influenced how they are represented in the photos. Therefore, the studio portraits cannot be reliably understood to reflect the students’ own perspectives. Given that parents and caretakers arranged for and paid for the students’ studio portraits, however, the photos can be analysed as reflections of British-Métis understandings of race, class, and gender in the British Empire.

Overall, British-Métis families chose to represent themselves in the portraits in line with British norms of middle-class respectability. Their dress, poses, props, and hairstyles are all standardly Victorian. Matt Dyce and James Opp argue that viewers of nineteenth-century photographs brought their “so-called social and cultural codes of the nineteenth century to bear on and explain” what they saw in photographic images.[47] In the case of photos of British-Métis students, studio portraits were primarily circulated to friends and family in Britain, the Canadian colonies, the HBC territories, and farther abroad.

The studio portraits of British-Métis children and youth demonstrate that the conventions that Dyce and Opp refer to were enacted in how people chose to compose their own images as well.[48] None of the British-Métis children in the dozens of studio portraits I have consulted thus far, for example, wear moccasins. Moccasins were the most common footwear for all residents in the HBC territories and were likely part of the students’ everyday wardrobe at home and at colonial schools. They also do not wear Métis sashes, or hide vests or coats. Their clothes are not decorated with the beadwork and embroidery that decorated many of the items sewn by British-Métis women, despite the expertise and artistry that are evident in sewing produced by Métis women like Mary Sinclair Christie and her daughters.[49]

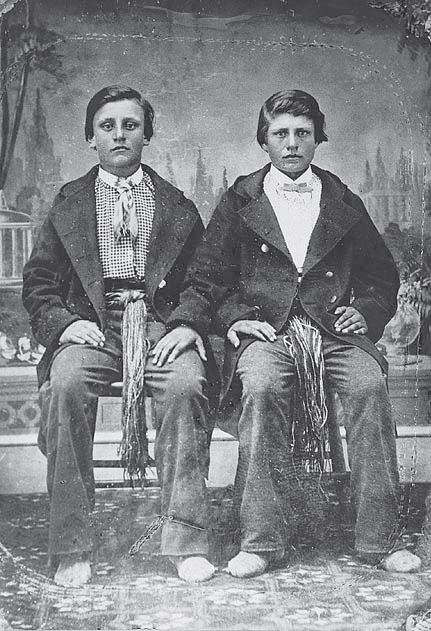

By contrast, and as a way to demonstrate how different Métis people made other choices, in an 1871 studio portrait of Joseph and Charles Riel, Louis Riel’s younger brothers, the boys wear moccasins and sport Métis sashes around their waists (Figure 2). The Riel family were leaders among the Red River Métis, were well-educated, and economically secure. However, unlike British-Métis families who eschewed visual representations of indigeneity in their studio portraits, the Riel family chose to put their Métis heritage on display in the brothers’ portrait. It is unclear what the moccasins and sashes in the photo are meant to represent. Their inclusion could speak to their Métis heritage, or to a moment of resistance and assertion of identity in the wake of the 1869−1870 Red River Resistance.

Figure 2

Joseph and Charles Riel, Winnipeg, 1871

British-Métis families’ decisions to exclude moccasins and beadwork from their studio photos should not necessarily be construed as an attempt to hide their Indigenous ancestries. This would, in fact, have been virtually impossible. The family and friends on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean who received the photos were already privy to students’ Cree, Anishinabeg, and Métis ancestries. Instead, these studio portraits are visual representations of one of the strategies that British-Métis fur-trade families enacted to access class-based status in colonial Rupert’s Land and in the larger British Empire. They purposefully presented themselves in ways that aligned with Victorian norms of class, gender, and respectability to reify their own power and status in a colonial society and abroad. Moreover, the images that the British-Métis children project in the photos align with the goals that parents had for educating their children in British-style schools. The students in the portraits embody British middle-classness. Circulating the photos through fur-trade country and beyond extended the privilege and contributed to reproducing and reifying these families’ elite status.

As objects, studio photos of British-Métis children and youth document mobility that the written record sometimes obscures.[50] The images in the photos, whether taken at Red River, Montréal, or London, are remarkably similar. In their homogeneity, they depict the permeation of mid-nineteenth century middle-classness throughout these sites of empire; it is difficult to determine where the photos were taken based solely on the imagery. Most of the photos, however, bear a maker’s mark that provides the name and place of the photographer’s studio. These maker’s marks are sometimes the only surviving evidence of a student’s transnational travels.

Figure 3

A photograph of a teenage Emma Christie serves as an example (Figure 3). Emma was a cousin of Mary Ann Christie, younger sister of Ann Mary Christie, and a student at the Miss Davis School. In the photo, Emma is standing with her hands resting on the back of a settee. She is dressed in a dark gown, and her long hair is pulled back from her face with a ribbon. She gazes off into the distance. Her dress, hair style, pose, and facial expression all represent the lady-like demeanor that Matilda Davis was known for inculcating in her students.[51] There is no mention in the family correspondence or in her father’s HBC records that Emma or her parents ever travelled to London. And yet, here is this picture, a formal portrait of Emma, with a maker’s mark that reads “A. Mayman, 170 Fleet Street,” referring to London photographer Alfred Mayman. What the picture reveals, and what is not recorded elsewhere in the family or HBC records, is that sometime between 1876 and 1878 Emma Christie crossed the Atlantic to Britain.[52]

In the context of the Christie family’s transnational life histories, Emma’s presence in London is not remarkable. Emma’s brothers attended The Nest Academy, which was in visiting distance to their Scottish grandfather Alexander Christie Senior’s homes in Edinburgh and then Nairn. Her mother’s brother, British-Métis educator, lawyer, and activist Alexander Kennedy Isbister, her Isbister grandmother, and unmarried aunt all lived in London.[53] Most likely, Emma travelled to London with her father after his retirement from the HBC in 1872 or 1873.[54] During their trip, Emma and her father would have stayed with the Isbisters in London, which is likely when this portrait was taken. This photo re-shapes my understanding of Emma Christie’s life history by revealing that she was part of the circuit of British-Métis youth who moved between Rupert’s Land and Britain.

Studio portraits of British-Métis students also functioned as objects of affect.[55] Tracing their routes as objects of affect further illuminate British-Métis trans-Atlantic kin networks. When students were away at school for sometimes years at a time, portraits reinforced affective ties between students and their families at home. Portraits of British-Métis students were part of the circuit of family news, sentiment, and daily life as it was conducted through fur-trade family correspondence. Matilda Davis arranged to have studio portraits taken of her students at least twice, and then sent the photos to her students’ parents.[56] In 1865, Emma Christie’s mother, Caroline Isbister Christie, thanked Miss Davis for sending along photos of Caroline’s eldest daughter, Ann Mary, and nieces Annie and Lydia. Christie commented of the girls that “they all look quite mature in their likenesses if not much flattered.”[57] Similarly, Albert Hodgson wrote to his uncle George Davis from The Nest Academy in 1867 and told his uncle that he and his cousin, Johnnie, were going to Edinburgh to get new clothes and have their “likenesses” taken.[58] Johnnie’s photo was apparently not to the boys’ satisfaction, as Albert wrote to his Aunt Matilda the next year that “we did not like his photograph ourselves because it was not like him.”[59] Photos of students away at school represented physical evidence of remembering. The act of posing for a photo and sending it via post required time and effort that signalled affective bonds.

Students’ photographs were posted to both immediate and extended family members, thereby creating a circuit of sentiment as photos were mailed sequentially from one family member to another. Ann Mary Christie, after having left the Davis school to reside with her father at Portage La Loche, wrote to her brother Duncan and sister Emma at the Davis school in 1870. In her letter to her siblings, she enclosed a photo of their brother Willie, who was at school at The Nest Academy. The photo had been taken in Edinburgh and sent first to Ann Mary, who then forwarded it on to her siblings at Red River. Of Willie she noted that “he has grown a big boy since you saw him last, and he is getting on so well with his studies.”[60] In these ways, the physical photos were part of transnational circuits of family sentiment that connected British-Métis children to extensive networks of kith and kin at various metropolitan and colonial sites.

Photograph Case Study: Lydia Christie in Scotland

Integrating analyses of studio portraits as both object and image with textual archival records provides more nuanced understandings of British-Métis students’ educational experiences and transnational life histories. In 1873, twenty-year-old Lydia Christie sang in a concert in Scotland. Lydia’s account of the concert and a photo of her that was taken during her trip offer a unique opportunity to contextualize the carefully-composed depictions of genteel middle-classness that characterize portraits of British-Métis children and youth (Figure 4). In both her photos and in her assessment of her time in Scotland as written in a letter to Matilda Davis, Lydia Christie provides insight into how her self-identity as a British middle-class woman was translated in a metropolitan setting. Although Lydia was a young woman by the time her portrait was taken in 1873, the photo and letter speak to the goals that fur-trade parents aimed to achieve by educating their British-Métis sons and daughters in respectability.[61]

Figure 4

In the photo, Lydia wears her hair in an intricate updo that signals her transition from girlhood to womanhood. She is dressed in a high-necked Victorian gown. Earrings decorate her ears and she wears a ring on her finger.[62] Her back is straight and her chin level as she gazes out the edge of the frame. Her hands are neatly folded on top of a book in her lap, a common prop in studio photographs meant to signal education and sophistication. Lydia is a vision of a Victorian woman. Her photo reflects the norms of British middle-class respectability that she was taught in school, in her church, and through colonial social norms. These practices of respectability were key to her status as a member of the fur-trade in Rupert’s Land.[63]

The photograph itself is undated, but, like the photo of Emma Christie, it bears a maker’s mark. This one shows the photo was taken in Portobello, Scotland. The letter that Lydia wrote to Matilda Davis on the same trip is also undated, but her references to events taking place in London date the letter as having been written in 1873. The letter provides context for the image of respectability that is represented in the portrait and outlines metropolitan challenges to Lydia’s claim on her status as a lady. In her letter, Lydia detailed her performance in a musical recital in Edinburgh. “I felt very nervous at first,” Lydia confessed, “but it soon passed away. My dress was all white with lavender sash and trimmings and I wore flowers of the same colour in my hair. Papa and Mama where [sic] there in full dress.”[64] In participating in the concert, Lydia Christie was literally performing the British middle-class identity she had learned at the Matilda Davis school.

The care and attention that Lydia Christie devoted to her choice of attire and appearance may reflect insecurity on Lydia’s part about her public performance in general, or as a colonial woman in a metropolitan setting in particular. Or she may have been excited to debut a new dress. In either case, Lydia’s attention to image in her performance and in her letter to Miss Davis align with the depictions of social class and respectability that are central to her studio portrait. The extent to which the Scots accepted Christie’s identification as a middle-class woman, however, is unclear. Lydia wrote to Davis that, “I do not like Scotland as well as I did Canada. In fact perhaps I should not say so as I have been here so short a time but the Canadian people are all much nicer…I think as a rule the Scotch people are very rude they will beat any people in the world for staring.”[65] Lydia’s assessment that the Scottish were “rude” could have been an observation of cultural differences between Canadians and Scots, although Lydia certainly came into contact with enough Scottish HBC employees in fur-trade country to be familiar with Scottish traits. Another possibility is that something about Lydia’s appearance, speech, or demeanor marked her as different and drew unwanted attention from metropolitan Scots. Her upbringing as a trans-imperial British-Métis lady was not enough to allow her to blend seamlessly into Scottish society. Her later marriage to HBC Chief Factor Donald McTavish, however, secured her union with a member of the emerging settler-colonial elite in western Canada and positioned her, like her mother before her, as the “lady” of the Fort.[66]

Taken together, Lydia’s photo and her letter provide a case study of how British-Métis fur-trade students translated the messages about social class, gender norms, and respectability that were part of their schooling experience. Studio portraits like Lydia’s also provide evidence of British-Métis students’ transnational travels and are physical representations of sentiment that helped to maintain affective family relationships. When read as texts, the photos provide insight into how these families chose to represent their identities in British colonial and metropolitan contexts. They also provide a visual depiction of the gender- and class-based British middle-class “respectability” that a British-style education was supposed teach British-Métis children and youth. As objects, the photos speak to both the students’ transnational life histories and the work that families did to maintain affective bonds during long separations.

Gravestones and Burial Sites

Depictions of British-Métis middle-classness as shown in students’ studio portraits reflect parents’ best-case scenario for sending their children away to school. Gravestones and burials in Britain represent another aspect of the educational experience. Like photos, Métis burial sites in Britain demonstrate that mobility and migration were common aspects of British-Métis educational experiences.[67] British-Métis gravestones and burial sites are both objects and physical spaces that represent Indigenous lives in the metropole and highlight the extensive trans-Atlantic kin ties that facilitated British-Métis students’ travels to and education in England, mainland Scotland, and the Orkneys. They signal the persistent and sometimes multi-generational travels of Métis fur-trade students to Britain. Gravestones and burial sites also, however, represent the worst possible outcome of a British-style education for the children and their families: disease and death far away from home.

The Davis family burial site in London provides one such example of place and multi-generational educational mobility. When Matilda Davis’ nephew, Albert Hodgson, visited his London kin during his holidays from his Walthamstow school in 1863, his English cousin Matilda Poole took Albert to visit the grave of Matilda Davis’ sister and Albert’s aunt, Elizabeth Davis.[68] Elizabeth, who had lived most of her childhood and all of her adulthood in England, died of a long-term illness at her English aunt’s London home in 1853.[69] Poole wrote to Matilda Davis of the visit: “I took Abbie through the cimetary [sic] and shewed [sic] him his dear Aunt Elizabeth’s grave & made him read what was engraved on the stone, Aunt Rossers also Miss Banns I shewed him, the latter is situated immediately at the head of our dear Elizabeth’s. It made me very sad to behold the resting place of those whom we once loved so dearly, but our loss is their gain.”[70] Elizabeth’s grave, alongside that of Albert’s great-aunt and cousin and near to his English relatives’ home, was a physical representation of the transnational kin ties that linked the London Davis family to their Métis relatives in England and Rupert’s Land. Moreover, Albert’s presence at the grave marked a second generation of educational travels for British-Métis Davis children to London. Unfortunately, Albert does not address the visit in his surviving letters from England, so we cannot know what it meant for him to stand in a place that so clearly demonstrated his family’s connection to London through the burial of their dead and his dead.

Death also marked British-Métis children’s educational histories in other ways. The prospect of a child falling ill while far from home loomed over fur-trade students’ schooling. For some fur-trade families, the “tragedy of children sent to distant schools, pining away and dying” became their reality when a child died at school.[71] In the absence of parents, however, fur-trade family networks were engaged to support ill and dying students. The Ballenden children provide an example of how kin networks were enacted to care for British-Métis children in Britain. Like many fur-trade families, John Ballenden and his British-Métis wife Sarah McLeod Ballenden turned to their kin in Scotland to care for children who were sent away to school.[72] Daughters Annie and Eliza and sons John Jr., Duncan, and Alexander were put under the guardianship of their widowed aunt, Elizabeth (Eliza) Ballenden Bannatyne, in order to attend school in Scotland.[73] The Ballenden children’s lives were unfortunately marred by death and discord.[74] Their parent’s marriage was rocked by the Foss-Pelly affair at Red River in 1849−1850, in which their mother was accused of adultery. The resulting scandal split Red River along class and racial lines, threatened John Ballenden’s career, and likely contributed to both Sarah’s and John’s subsequent ill health. The family relocated to Scotland in 1853, and Sarah and John died soon thereafter.[75]

In addition to their parents’ personal turmoil and early deaths, three of the Ballenden children also died abroad. In 1850, five-year-old Duncan Ballenden travelled with his father to Scotland to join his brothers and sisters in Edinburgh.[76] Soon after his father’s departure for North America the next year, six-year-old Duncan sickened and died at his aunt’s home. John Jr. died in New Zealand from wounds received in the Maori Wars, and brother Alexander drowned in the Tweed River as a teenager while trying to rescue a friend in distress.[77] Throughout these challenges, the Ballenden siblings’ Aunt Eliza remained a constant. She cared for the children before their parents’ deaths, nursed Duncan in his dying days, and became the legal guardian of the children after John Ballenden’s death in 1856. In 1861, a married Annie Ballenden McMurray, her infant son William McMurray Jr., and siblings Alexander, Frances, and William Ballenden all lived with their aunt.[78]

Figure 5

Ballenden Family Memorial Stone, Edinburgh[79]

The Ballenden family gravestone in New Calton Burial Ground in Edinburgh was erected by John Ballenden in 1853 (Figure 5). The stone’s text bears witness to the family’s trans-Atlantic life histories and the death and trauma that marked their journeys.[80] The gravestone also speaks to silences and erasures in the archival record of these transnational kin networks. The stone memorializes the deaths of John Ballenden’s father, mother, brothers, sister, niece, wife, and children. The stone is silent, however, about his father’s extensive Métis family in Rupert’s Land, where the elder Ballenden’s two children with Jane Favel, William and Harriet Ballenden, both lived to adulthood, married, and had large families of their own. None of the siblings returned to North America permanently despite their extensive kin ties to the fur trade on both their father’s and mother’s sides of the family.[81] Perhaps the inscription on the gravestone recording Ballenden’s own death and noting that he erected the stone “in memory of so many broken ties of kindred and affection” provides insight as to why the surviving siblings chose to stay in Scotland. At the very least, the stone and inscription signal both the complexity and the silences in negotiating transnational fur-trade family relationships.

Gravestone Case Study: Roderick McKenzie in Scotland

The life and death of Roderick McKenzie Jr. offers a second example of how integrating archival documents and objects provides a better understanding of British-Métis students’ life histories. Like the histories of the other British-Métis children and youth examined here, Roderick’s educational history challenges assumptions about Indigenous children’s place in the British Empire and underscores the trans-Atlantic kin ties that bridged the supposed divide between the colonies and the metropole. His gravestone, like that of the Ballendens, demonstrates how indigeneity was written out of the metropolitan historical record while his burial place stands as evidence to the trans-Atlantic kin networks that enfolded him in both life and in death.

In 1865, Roderick McKenzie Jr. and his brother Kenneth left their home at Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River to travel to Scotland. The boys’ father, HBC Chief Trader Roderick McKenzie, their mother Jane, and two younger siblings accompanied Roderick Jr. and Kenneth as far as Sutton in Canada West. The family stayed at Ainslea Hill, the home of retired Chief Factor James Anderson and his wife, Margaret McKenzie Anderson. Roderick and Kenneth’s mother, Jane McKenzie McKenzie, and the two younger children stayed at Ainslea Hill with Jane’s sister, Margaret.[82] The two older boys travelled on to Scotland with their father.[83]

On reaching Scotland, the McKenzies stayed in Ullapool, where Kenneth and Roderick were put in the care of their Scottish aunt, Catherine McKenzie Maclean.[84] Mrs. Maclean escorted the boys to The Nest Academy several weeks later for the beginning of the school year.[85] She wrote regularly to the boys when they were at school, and the brothers went to Ullapool to visit their Scottish relatives during their holidays.[86] Roderick became quite close with his Scottish cousins.[87]As in the Ballenden family, Roderick McKenzie Jr.’s Scottish family was tasked with overseeing the well-being of the two brothers. This responsibility continued when fifteen-year-old Roderick suddenly fell ill while at school and died. A series of letters from his caretakers at the school, and from Roderick himself, document his decline and unexpected death. When Roderick wrote to his mother in February 1870, he reported that he had not been outside for the past three days because he had a cold and the doctor was making him stay inside.[88] Roderick’s “cold” developed into a much more serious illness. One month later, Marion Millar, the woman in charge of domestic affairs at The Nest Academy, informed Roderick’s parents that Roderick’s health was deteriorating rapidly. Millar had already alerted Roderick’s Scottish kin at Ullapool about his condition, and she noted that “all the family there seem much grieved to hear of his illness.”[89]

In her next letter, dated only eleven days later, Millar wrote to the McKenzies that Aunt Catherine had arrived from Ullapool and served as Roderick’s constant nurse. Unfortunately, Roderick was “fast sinking,” coughing blood and growing weaker.[90] It is clear in the letter that Roderick’s caretakers believed that his death was imminent. Just a week later, Roderick McKenzie Jr. passed away. Although Roderick’s death was undoubtedly a terrible blow to his parents, the comfort he received from his aunt and teachers in his dying days may have provided some solace to his family. At home in Rupert’s Land, Roderick Jr’s death was mourned by his parents, siblings, and extended kin. His letters home to his parents were cherished and saved in the family archive, unlike those from his sister who was at school in Montréal or his brother Kenneth at The Nest.

Roderick’s parents requested that his remains be sent to his relatives in Ullapool and buried alongside his kin in the parish cemetery.[91] Roderick Sr. and Jane wrote the text for their son’s gravestone and sent it to Ullapool. A copy that they kept reads:

Here lie

The remains of

Roderick John

The beloved and

Affectionate Son of

Roderick & Jane McKenzie

Who departed this life

On the 21st March

1870

Aged 15 Years

Even so Father for so it

Seemed good in thy

Sight[92]

The inscription that Roderick’s parents dictated differs slightly from the text on his gravestone in the Old Mill Cemetery in Ullapool:

Here lies the remains of

Roderick John

The beloved and affectionate son

Of Roderick and Jane McKenzie

Who fell asleep in Jesus

The 20th March 1870

Aged 15 years

“Even so Father it seemed good”[93]

It is unclear why the two inscriptions are different. What is notable, however, is that Roderick’s birthplace and mother’s maiden name are excluded from the gravestone and from the original inscription that was dictated by his parents. Roderick’s time in Scotland is not captured in the Scottish census, and the only surviving records that I have located from The Nest Academy are held by the Archives of Manitoba. Roderick’s headstone, and perhaps a death record, are therefore the only evidence that inscribes his time in Scotland in the metropolitan historical record. Neither of these sources includes his birthplace or acknowledges his Métis heritage, thereby erasing his indigeneity, colonial roots, and transnational life story from Britain’s history.

The deaths of British-Métis students were the realization for some parents of the ultimate cost of seeking a British-style boarding school education for their children. At the same time, however, illness and impending death engaged extended fur-trade family networks in support of dying students. Although the British-Métis headstones examined here obscure the children’s and families’ Indigenous roots, the trans-Atlantic kin networks that united Indigenous and non-Indigenous kin inscribed these students’ histories on Britain in other ways. The location of Roderick’s grave in his Scottish family’s parish cemetery, for example, is evidence of the transnational kin ties that supported him in both life and death even if his birth place is excluded from the text on the stone. Moreover, Roderick’s burial site, like that of Elizabeth Davis and the Ballenden children, is a Métis claim on physical space in Britain. The obliteration of the students’ Indigeneity from metropolitan memory does not erase their travels to and presence in Britain as Métis people. Although evidence of the students’ Indigeneity may be obscured in the written record recorded on the gravestones, the burial sites themselves challenge this erasure and stand as evidence of the transnational travels of elite British-Métis children and youth, their lasting impact on the metropole though the kin ties that they created and reified, and the physical spaces that memorialize the students’ short lives.

Conclusion

British-Métis fur-trade families occupied both a privileged and a tenuous place in the hierarchy of race, gender, and class that shaped metropolitan understandings of Indigenous colonial peoples and colonial societies in places like the HBC territories. The intersection of the students’ Indigenous and British family ancestries, their Protestant religion, the socio-economic privilege afforded to them through their integration into the HBC officer class, and their adoption of British middle-class social and gender norms afforded them positions of power and privilege in the HBC territories. Their elite status represents a specific moment in mid-nineteenth-century colonial Canada whereby the convergence of the HBC monopoly, Métis power in the fur trade, and British imperial perspectives on class and race created space for British-Métis families to hold significant economic and social status in the HBC territories. Through their kin ties to Britain, this elite status was not just specific to colonial Canada but translated to British middle-classness in the metropole as well.

Examining British-Métis students’ educational travels highlights the extent to which these British-Métis children and families were mobile in the British Empire. This mobility and their consistent and sustained presence in Britain through the nineteenth century directly challenged imperial understandings of the place and role of Indigenous peoples in the British Empire. Moreover, in a historiography that has tended to focus on First Nations and Métis mothers and white European fathers, centering British-Métis children lends another perspective to understanding fur-trade, Métis, and Canadian histories. Studio portraits of British-Métis children and youth, their gravestones, and their burial sites provide more nuanced perspectives on these students’ time spent in Britain, their place in extensive trans-Atlantic kin networks, and on the complexities of living their lives as both Métis and elite persons in the British Empire.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the anonymous reviewers, the JCHA editors, Adele Perry, Cheryl Troupe, Kristine Alexander, Krystl Raven, and Elaine Millions for their feedback on this paper. I use double-naming (maiden last name and married last name) for women in this study. Double-naming better illuminates the extensive maternal First Nations and Métis kin networks that underwrote and were essential to the fur trade and to British-Métis children’s education. Adele Perry, Colonial Relations: The Douglas-Connolly Family and the Nineteenth-Century Imperial World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 7.

Biographical note

ERIN MILLIONS is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Winnipeg. Her current research responds to community requests to locate missing Indigenous tuberculosis patients in Manitoba. The project assesses the administration of death and burial of Indigenous child tuberculosis patients at two tuberculosis sanatoriums in the province.

Notes

-

[1]

Matilda Davis established and ran the Oakfield Establishment for Young Ladies (known colloquially as the Miss Davis School) at St. Andrew’s parish in the Red River Settlement in 1856 until her death in 1873. Davis was the daughter of English Hudson’s Bay Company officer John Davis and his Métis wife (Anne) Nancy Hodgson. Matilda lived in England from 1822, when her father took her and her sister to London to live with his English siblings, until her sister Elizabeth’s death around 1853. She returned to Red River in 1854 and opened her school around 1856. Archives of Manitoba (AM), P4724 fo.2, Matilda Davis School Collection, William G. Smith to Matilda Davis, 18 June 1854.

-

[2]

Mary Sinclair Christie was married to William J. Christie, the Chief Factor at Fort Edmonton. Mary was the daughter of William “Creedo” Sinclair II (Scots-Cree) and his wife Mary Wadden McKay (Métis). The sister-in-law referred to in the letter is Mary Christie Patterson, who was William J. Christie’s younger sister. She moved to Scotland with her parents when they retired there in the 1850s, married, and remained in Britain until her death. 1861 Scottish Census, Roll CSSCT1861_129, Line: 11, Edinburgh St Cuthberts; ED: 68; Page: 14, Mary Patterson,; digital image, Ancestry.com, <accessed 5 November 2014>, http://ancestry.com.

-

[3]

Ann Mary Christie was the daughter of Alexander Christie Jr and Caroline Isbister. Alexander Christie Jr, William J. Christie, Mary Christie Patterson, and Margaret Christie Black were the children of Governor Alexander Christie of Scotland and Ann Thomas, the daughter of John Thomas and his Cree wife Margaret. The couple entered a relationship à la façon du pays around 1815 and were married by Christian rites at Red River in 1835. University of Manitoba Archives and Special Collections (UMASC), Jennifer Brown Fonds, Box 2 File 17, MSS 336 A. 11, Alexander Christie File.

-

[4]

AM, Matilda Davis Family Collection, P4724 fo.3, Mary Sinclair Christie to Matilda Davis, 3 January 1865.

-

[5]

Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (HBCA), B.60/a/35, Fort Edmonton Post Journal, 14 January 1865.

-

[6]

I use the term “HBC territories” to denote the regions west of the Great Lakes that were under the control of the Hudson’s Bay Company after 1821. This includes modern-day north-western Ontario, the prairie provinces, most of British Columbia and the northern regions of Canada, and parts of Oregon.

-

[7]

For studies that incorporate an imperial perspective on Métis and fur-trade history, see Krista Barclay, “‘From Rupert’s Land to Canada West: Hudson’s Bay Company Families and Representations of Indigeneity in Small-Town Ontario,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 26, no.1 (2015): 67−97; Patricia McCormack, “Lost Women: Native Wives in Orkney and Lewis,” in Recollecting: Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands, ed. Sarah Carter and Patricia McCormack (Athabasca: Athabasca University Press, 2011), 61−88; Perry, Colonial Relations.

-

[8]

The focus here is on British-Métis children and youth as students. The age range of the students in the larger study included children as young as three through to university students. I use the terms ‘children and youth’ here to denote students who were unmarried, financially dependent on their parents, and unemployed. Most of the students, however, finished their studies as teens and went on to work or marriage.

-

[9]

For further discussions of “English Métis” identity and terminology see, Jennifer Brown and Theresa Schenck, “Métis, Mestizo and Mixed-Blood,” in A Companion to American Indian History, ed. Philip Deloria and Neil Salisbury (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2002), 321−38; John E. Foster, “The Country-Born in the Red River Settlement, 1818−1870 (PhD diss., Queen’s University, 1974); John E. Foster, “The Origins of the Mixed-Bloods in the Canadian North West,” in Essays on Western History: In Honour of Lewis Gwynne Thomas, ed. L.H. Thomas (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1976), 69−80; Frits Pannekoek, A Snug Little Flock: The Social Origins of the Riel Resistance 1869−70 (Winnipeg: Watson and Dwyer, 1991); Sylvia Van Kirk, “‘What if Mama is an Indian’: The Cultural Ambivalence of the Alexander Ross family,” in The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Métis, ed. Jennifer Brown and Jacqueline Peterson (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1985), 205−217; Sylvia Van Kirk, “Colonized Lives: The Native Wives and Daughters of Five Founding Families of Victoria,” in In the Days of Our Grandmothers: A Reader in Aboriginal Women’s History in Canada, ed. Mary-Ellen Kelm and Lorna Townsend (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006), 170−99.

-

[10]

Thank you to Sherry Farrell Racette, Cheryl Troupe, Jesse Thistle, Adele Perry, Krista Barclay, and Krystl Raven for their feedback on terminology. Although these conversations were enlightening, in the end there was no consensus on what to call this specific group of elite Indigenous fur-trade families.

-

[11]

Chris Andersen’s critique of “mixedness” as leading to definitions of Métisness rooted in biology instead of in “historical, peoplehood-based relationships” is relevant here. Métis families’ self-identities were not defined solely by biology, but instead by shared history, kin ties, religion, and understandings of land and place. Chris Andersen, Métis: Race, Recognition and Indigenous Peoplehood (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), 10−11.

-

[12]

The relationship between the descendants of these elite fur-trade families and the Métis Nation today is unclear. The children qualified for scrip under the 1870 Manitoba Act and subsequent scrip commissions, and most of the children in this study claimed scrip or had it claimed in their name. They were part of the Métis Nation as it is defined today by the Manitoba Métis Federation and the Métis National Council. Some of their descendants today identify as members of the Métis Nation, and some do not.

-

[13]

Heather Devine explores class and socio-economics distinctions of Métis families who live an “affluent existence” in her book People who own themselves: Aboriginal Ethnogenesis in a Canadian family, 1660−1900 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2004), 87.

-

[14]

Although the lives of British-descended Protestant and French-descended Roman Catholic Métis fur-trade families were intertwined in many ways, including through marriage and kin ties, the families in this study acknowledged clear and specific socio-economic and religious differences between themselves and the francophone Roman Catholic families ‘on the other side of the river’ at Red River or ‘in the valley’ in the Columbia District. For more on this, see Métis women’s recollections of early Red River in W.J. Healy, Women of Red River: Being a book written from the recollections of women surviving from the Red River era (Winnipeg: Canadian Women’s Club, 1923; republished Peguis Publishers Ltd., 1987).

-

[15]

For example, Michel Hogue, Métis and the Medicine Line: Creating a Border and Dividing a People (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2015); Émilie Pigeon, “Au Nom du Bon Dieu et du Buffalo: Metis Lived Catholicism on the Northern Plains,” (PhD diss., York University, 2017); Nicole St. Onge, Saint-Laurent, Manitoba: Evolving Métis Identities, 1850−1914 (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2004); Jesse Thistle, “The Puzzle of the Morrissette-Arcand Clan: A History Of Metis Historic and Intergenerational Trauma” (MA Thesis, University of Waterloo, 2016).

-

[16]

More research is needed to understand the histories of the Métis between and the 1870s and the 1940s. Many British-Métis male students went on to become doctors, lawyers, bankers, judges, Indian agents, and Department of Indian Affairs farm instructors. Female students married senators and other leaders of the emerging settler-colonial society in western Canada; some established careers in their own right. Edith Rogers, the first woman Member of the Legislative Assembly in Manitoba, was Lydia Christie McTavish’s daughter. It is possible that, with the decline of the fur trade and the rise of the settler-colonial state after the late 1870s, employment in the burgeoning civil service and other state-related positions became a substitute for these families’ connections to the declining HBC officer class. For more on the Métis into the twentieth century, see Devine, People Who Own Themselves; Evelyn Peters, Matthew Stock, Adrien Werner, Rooster Town: The History of an Urban Métis Community, 1901–1961 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2018); St. Onge, Saint-Laurent.

-

[17]

Both Elizabeth and Matilda Davis attended the Adult Orphan Institution in London as teenagers, which was a school that trained the female orphans of British military men to work as governesses. They both went on to work as governesses in England and Scotland. AM, Matilda Davis Family Papers, P2342 fo.1, H. Danford to Miss Davis, [1840]; Currie Family Papers (private collection of Judy Kessler), Unknown author to Matilda Davis, 11 August [nd]; Margaret E. Bryant, The London Experience of Secondary Education (London: The Athalone Press, 2002), 348−9.

-

[18]

For more on the education offered at the Miss Davis School, see Sherry Farrell Racette, “Sewing Ourselves Together: Clothing, Decorative arts and the Expression of Metis and Half Breed identity” (PhD diss., University of Manitoba, 2004); Erin Millions, “‘By education and conduct’: Educating Trans-imperial Indigenous Fur-Trade Children in the Hudson’s Bay Company Territories and the British Empire, 1820s to 1870s” (PhD diss, University of Manitoba, 2017), chapter 4, http://hdl.handle.net/1993/32785.

-

[19]

For more on the relationship between education, employment, and marriage for fur-trade children, see Denise Fuchs, “Native Sons of Rupert’s Land 1760 to the 1860s” (Ph.D. diss, University of Manitoba, 2000); Millions, “By Education and Conduct,” (2017); Juliet Pollard, “The Making of the Métis in the Pacific Northwest, Fur Trade Children: Race, Class and Gender” (Ph.D. diss, University of British Columbia, 1990).

-

[20]

The Nest Academy in Jedburgh, Scotland was a privately-run boarding school for boys. The school operated for about a century in the shadow of the ruins of the Jedburgh Abbey before it closed in the early twentieth century. It is unclear how the school came to be popular amongst fur-trade families, but it may have been recommended by Alexander Kennedy Isbister, a London-based Métis lawyer, educator, and activist with kin ties to the Christie family. The following British-Métis sons attended The Nest Academy between 1861 and 1871: Christie cousins Alexander III, James Thomas, Robert William, Duncan, William Joseph, John Dugald, James Grant, and Charles Thomas; Albert Hodgson and Johnnie Davis; John Cowan; Harry McAdoo Grahame; Henry and James Stewart; James and Harry Helmcken.

-

[21]

In 1868, William J. Christie was granted furlough and he and his wife travelled to Britain. William accompanied his daughters to Montréal, where they stayed with “Mrs. Simpson” at Lachine. It is unclear whether this was a schoolmistress, or, given the fur-trade name “Simpson” and their stay at the former North American headquarters of the HBC at Lachine, if it was a relative of former HBC Governor George Simpson (d. 1860). The correspondence indicates that the girls were meant to attend school during their parents’ year abroad, but there are no records that confirm their attendance. Margaret (Annie) Christie married her father’s steward, Malcolm Groat, at Fort Edmonton in 1870. AM, Matilda Davis School Collection, 10 September 1868, P4724 fo. 4, William J. Christie to Matilda Davis, 10 September 1868.

-

[22]

Elizabeth Buettner, Empire Families: Briton and Late Imperial India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Ellen Filor, “‘He is hardened to the climate & a little bleached by it’s [sic] influence’: Imperial Childhoods in Scotland and Madras, c. 1800−1830,” in Children, Childhood and Youth in the British World, ed. S. Robinson and S. Sleight (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016): 77−91.

-

[23]

Suresh Chandra Ghosh, “‘English in taste, in opinions, in words and intellect’: Indoctrinating the Indian through textbook, curriculum and education,” in The Imperial Curriculum: Racial Images and Education in the British Colonial Experience, ed. J.A. Mangan (London: Routledge, 1993), 175−241; Satadru Sen, “The Politics of Deracination: Empire, Education and Elite Children in Colonial India,” Studies in History 19, no. 1 (2003): 19−39.

-

[24]

I draw my understanding of the mid-nineteenth century British middle-class from Lenore Davidoff and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850 (London: Routledge, 2002); Catherine Hall, ed., White, Male and Middle-Class: Explorations in Feminism and History (New York: Routledge, 1992); John Tosh, A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999).

-

[25]

Kristine Alexander, “Can the Girl Guide Speak? The Perils and Pleasures of Looking for Children’s Voices in Archival Research,” Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures 4, no.1 (2012): 132−45; Durba Ghosh, “Decoding the Nameless: Gender, subjectivity, and historical methodologies in reading the archives of colonial India,” in A New Imperial History: Culture, Identity and Modernity in Britain and the Empire, 1660–1840, ed. Kathleen Wilson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 297−316; Mary Jo Maynes, “Age as a Category of Historical Analysis: History, Agency, and Narratives of Childhood,” Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 1, no.1 (2008): 114−24; Jean M. O’Brien, “Historical Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies: Touching on the past, looking to the future,” in Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, ed. Chris Andersen and Jean M. O’Brien (New York: Routledge, 2016), 15−22.

-

[26]

Kristine Alexander, “Picturing Girlhood and Empire: The Girl Guide Movement and Photography,” in Colonial Girlhood in Literature, Culture and History, 1840−1950, ed. K. Mizouri and M. Smith (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014): 199. For examples of genealogy-centred Métis histories, see in Devine, People who own themselves; Brenda Macdougall, One of the Family: Métis Culture in Nineteenth Century Northwestern Saskatchewan (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010); Cheryl Troupe, “Mapping Métis Stories: Land Use, Gender and Kinship in the Qu’Appelle Valley, 1850−1950,” (PhD diss, University of Saskatchewan, 2019), https://harvest.usask.ca/handle/10388/12122.

-

[27]

Patricia Pok-kwan Chiu, “‘A Position of Usefulness’: Gendering History of Girls’ Education in Colonial Hong Kong,” in Girlhood: A Global History, ed. Jennifer Helgren and Colleen Vasconcellos (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 789−805; Aviston Downes, “From Boys to Men, Colonial Education, Cricket and Masculinity in the Caribbean, 1870−c1920,” International Journal of the History of Sport 22, no.1 (Jan. 2005): 14−17; Greg Ryan, “Cricket and Moral Curriculum of the New Zealand Elite Secondary Schools c1860−1920,” The Sports Historian 19, no.2 (1999): 61−79; Nancy Stockdale, “Palestinian Girls and British Missionary Enterprise, 1847−1948,” in Girlhood: A Global History, ed. Jennifer Helgren and Colleen Vasconcellos (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 217−33.

-

[28]

I differentiate between gravestones as grave markers that usually bear text, and burial sites as spaces where remains are interred. Given the deterioration of gravestones and other forms of grave markers, sometimes there are records of and locations for burials where gravestones no longer exist.

-

[29]

Nicole St. Onge, Carolyn Podruchny and Brenda Macdougall, “Introduction: Cultural Mobility and the Contours of Difference,” in Contours of a People: Métis Family, Mobility and History, ed. Nicole St. Onge, Carolyn Podruchny and Brenda Macdougall (Norman, OK: Oklahoma University Press, 2012). The collection as a whole explores issues of mobility in Métis history.

-

[30]

Simon Sleight and Shirleene Robinson, “Introduction: The World in Miniature,” in Children, Childhood and Youth in the British World, ed. Sleight and Robinson (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 2.

-

[31]

Fiona Paisley, “Childhood and Race: Growing Up in the Empire,” in Gender and Empire: The Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series, ed. Philippa Levine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 23.

-

[32]

Laura Ishiguro, “Discourses of Childhood and Settler Futurity in Colonial British Columbia,” BC Studies no. 190 (Summer 2016): 15−37; Daniel Livesay, “Extended Families: Mixed-Race Children and Scottish Experience, 1770−1820,” International Journal of Scottish Literature 4 (Spring/Summer 2008): 1−17.

-

[33]

Catherine Hall, Civilizing Subjects: Colony and Metropole in the English Imagination, 1830−1867 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2002), 8.

-

[34]

Antoinette Burton and Tony Ballantyne, “Introduction: The Politics of Intimacy in an Age of Empire,” in Moving Subjects: Gender, Mobility and Intimacy in an Age of Global Empire, ed. Burton and Ballantyne (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 5−6.

-

[35]

John Gasciogne, “The Expanding Historiography of British Imperialism,” The Historical Journal 49, no.2 (June 2006): 577−8.

-

[36]

Jane Carey and Jane Lydon, “Introduction: Indigenous Networks Historical Trajectories and Contemporary Connections,” in Indigenous Networks: Mobility, Connections and Exchange, ed. Jane Carey and Jane Lydon (Florence: Taylor and Francis, 2014), 2.

-

[37]

Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire (New Haven, NJ: Yale University Press, 2016), 14.

-

[38]

Jennifer Brown and Sylvia Van Kirk both made note of these trans-Atlantic travels in their early works on fur-trade women and families. Recently, Jennifer Brown has revisited her work on these children in an updated version of her article “Fur Trade Children in Montréal: The St. Gabriel Street Church Baptisms, 1796–1825,” in Jennifer Brown, An Ethnohistorian in Rupert’s Land: Unfinished Conversations (Athabasca: Athabasca University Press, 2017), 145−55. More recently, see Cecilia Morgan, Travellers Through Empire: Indigenous Voyages from Early Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017).

-

[39]

Karen Dubinsky, Adele Perry, and Henry Yu, “Canadian History, Transnational History,” in Within and Without the Nation: Canadian History as Transnational History, ed. Dubinksy, Perry and Yu (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 9.

-

[40]

For example, see the works of Paul Kane (LAC), Peter Rindisbacher (LAC), and Henry Youle Hind (AM).

-

[41]

Sherry Farrell Racette, “Returning Fire, Pointing the Canon: Aboriginal Photography as Resistance,” in The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada, ed. Carol Payne and Andrea Kunard (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011), 72. Farrell Racette’s article goes on to explore both historical and contemporary Indigenous photographers.

-

[42]

Carol Williams, Framing the West: Race, Gender, and the Photographic ‘Frontier’ in the Pacific Northwest (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 27.

-

[43]

Marianne Hirsh, Family Frames: Photograph, Narrative, and Postmemory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997; reissued 2012).

-

[44]

Sherry Farrell Racette, “Haunted: First Nations Children in Residential School Photography,” in Depicting Canada’s Children, ed. Loren Lerner (Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2003), 49−83; Carol Williams, “Residential School Photographs: The Visual Rhetoric of Indigenous Removal and Containment,” in Photography and Migration, ed. Tanya Sheehan (New York: Routledge, 2018). On photos and images of Canadian children, see Anne Higonnet, Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998); Loren Lerner, Depicting Canada’s Children.

-

[45]

Julie F. Codell, “Victorian Portraits: Re-Tailoring Identities,” Nineteenth-Century Contexts: An Interdisciplinary Journal 35, no.5 (2012): 494.

-

[46]

Lara Perry, “The Carte de Visite in the 1860s and the Serial Dynamic of Photographic Likeness,” Art History 25, no.4 (September 2012): 733.

-

[47]

James Opp and Matt Dyce, “Visualizing Space, Race, and History in the North: Photographic Narratives of the Athabasca-Mackenzie River Basin,” in The West and Beyond, ed. Alvin Finkel, Sarah Carter, and Peter Fortna (Athabasca University Press, 2010), 67.

-

[48]

Tanya Sheehan, “Looking Pleasant: Feeling White: The Social Politics of the Photographic Smile,” in Feeling Photography, ed. Elspeth Brown and Thy Phu (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 129; Gil Pasternak, “Intimate Conflicts: Foregrounding the Radical Politics of Family Photographs” in Photography, History, Difference, ed. Tanya Sheehan (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2014), 218.

-

[49]