Résumés

Abstract

When the Halifax Asylum for the Blind opened its doors to students in 1872, its funding came from charitable donations, with only limited financial support from the provincial government. However, sighted children in Nova Scotia had been entitled to tax-based funding for their education since the 1864 Free Schools Act. To ensure sufficient funding for his students, Charles Frederick Fraser, the blind Superintendent of the Asylum, began an appeal to bring in additional donations. Fraser then used the same appeal to persuade the Nova Scotian government to provide tax-based funding in a similar manner to that available for educating sighted students, arguing that his students were citizens just as much as their sighted counterparts. Fraser contended that funding the education of blind children was a sound fiscal move on the part of the provincial and municipal governments as it would eliminate the far greater expense of caring for unemployable, despondent blind adults. This paper explores the importance of Fraser’s campaign in the fight for rights for blind people in the Maritime provinces.

Résumé

Lorsque le Halifax Asylum for the Blind ouvre ses portes en 1872, il est financé essentiellement par des dons de charité, ainsi qu’une petite subvention du gouvernement provincial. Parallèlement, depuis l’adoption du Free Schools Act de 1864, les enfants malvoyants néo-écossais avaient droit à une éducation financée par le gouvernement. Afin de s’assurer d’un financement suffisant pour ses propres élèves, Charles Frederick Fraser, le surintendant aveugle du Halifax Asylum, débute une campagne de levée de fonds. Il se sert ensuite du même appel pour persuader le gouvernement provincial d’octroyer une subvention plus importante à son institution, subvention similaire à celle offerte aux élèves malvoyants, soutenant que ses élèves aveugles étaient citoyens au même titre que les malvoyants. Fraser soutient alors que l’éducation des enfants aveugles était une bonne mesure fiscale pour le gouvernement provincial et l’administration municipale puisqu’elle leur éviterait d’avoir à prendre en charges nombre d’adultes aveugles dépendants et inaptes au travail. Cet article explore l’importance de la campagne de Fraser dans le cadre de sa lutte pour le droit des gens aveugles dans les provinces maritimes.

Corps de l’article

At the celebration of his 50 years of service at the Halifax Asylum for the Blind, Sir Charles Frederick Fraser was praised by the Morning Chronicle as being the reason that Halifax, in 1923, enjoyed an international reputation as being at the “very forefront of education for the blind.”[2] The Morning Herald described him as a “crusader and pioneer who had pointed the way and brought happiness to hundreds of handicapped men and women.”[3] The Board of Managers of the asylum expressed their pleasure at his “far reaching influence …. Under [his] sympathetic guidance and inspired by [his] example [the pupils] have gained the confidence and courage which has enabled them to become useful and independent members of society.”[4] Both the newspapers and the Board of Managers made mention of Fraser’s campaign for free education for blind children across Nova Scotia through tax-based funding, similar in style to the funding available to educate sighted children; his development of a free circulating library for blind people across the Maritime Provinces; and his campaign to give all blind children and blinded adults access to the tools and education necessary to become self-supporting. Fraser, as superintendent of the asylum, was specifically credited for its success while the Board of Managers was cast in a supporting role, with only the chairman of the board mentioned by name.

Fraser’s Asylum for the Blind[5] was just one of many institutions built in Halifax during the nineteenth century as part of the city’s progressive era. In the decades before Confederation, the charitable public and the provincial government contributed funds to build a variety of institutions with both educational and moral reform-based goals, including industrial schools for delinquent boys and a variety of missions to aid the deserving poor.[6] The asylum was also not unique in being a school aimed at educating children with sensory-disabilities, having been built 15 years after the foundation of the Halifax Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. As citizens of a bustling port city with strong ties to both the United Kingdom and the United States, Haligonians were aware of the ways in which problems presented by children with disabilities were addressed in those countries, and the politically connected merchant class and growing middle class both supported institutions and education to solve social ills.[7]

One factor that makes the asylum’s history unique, both in Halifax and across North America, is the lifetime involvement of Sir Charles Frederick Fraser. Like many leaders of institutions in Halifax in the nineteenth century, Fraser came from a wealthy, politically connected family. His father, Benjamin DeWolf Fraser, was a well-respected doctor in Windsor, Nova Scotia; his mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of Joseph Allison, a successful merchant and member of the Nova Scotia Council of Twelve. His family home is described in one biography as being “noted for its hospitality,” while another highlights the family’s social class and political connections by describing a visit from the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) and the Marquis of Lorne.[8] With this background, Fraser was well able to negotiate on behalf of his students with the political and religious leaders of Halifax and across the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland.

In addition, Fraser, like his students, was blind. This distinguishes his tenure at the asylum not only from that of J. Scott Hutton, the hearing principal of the Halifax Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, but also from superintendents of other blind asylums, such as Samuel Gridley Howe in Massachusetts and John Barrett McGann in Ontario. As a blind adult, Fraser was aware not only of the capabilities of other blind men, but also of the struggles they would face in gaining employment and respect. As the child of two wealthy Nova Scotians, he could speak effectively to the politicians and wealthy donors who would financially support the asylum. As a successful educator, he could stand as an example of what educated blind adults could achieve. As the superintendent of the Asylum for the Blind, he successfully campaigned for government-funded, free education for blind children, arguing that their rights to education were the same of those of sighted ones. Fraser, like many of the blind teachers he hired, was also able to stand as a role-model to his students, demonstrating for them and their families that targeted blind education could lead to a successful adult career.

This article examines the process through which Fraser changed the common perception of the Halifax Asylum for the Blind from a charitable institution into an educational one. The asylum was initially built to relieve the Nova Scotian public from the financial and emotional burden of supporting non-working, dependent blind adults through charitable donations by teaching blind children vocational skills. Fraser’s initial fund-raising campaigns followed this model, emphasizing the benefits to the community when asking for charitable contributions. However, shortages in the budget made it apparent that variable charitable donations could not support the asylum’s needs. As a result, Fraser altered the campaign: instead of variable charitable donations to support a dependent class, he highlighted the right of blind children to an education based on their status as citizens of Nova Scotia. This successful campaign not only secured regular, tax-based funding for the asylum, but also influenced the public perception of blind children and adults.

The nineteenth century saw a number of changes in notions of disability and dependency. Discussions of the welfare state, including Nancy Fraser and Linda Gordon’s “‘Dependency’ Demystified” and the work of Mariana Valverde, Paula Maurutto, and Shirley Tillotson, have described both the processes and mechanisms used in the creation of dependent and independent individuals and classes of people.[9] Applying this analysis to projects such as the asylum demonstrates how these mechanisms affected the asylum, and the resulting change over time in how the students were discussed by the government, by the Board of the Asylum, and by potential charitable contributors. This article draws upon Valverde, Maurutto, and Tillotson’s examination of the mixed social economy in the late nineteenth century. Using Ontario’s government funding for institutions such as asylums, orphanages, and residential schools for children with disabilities as an example, Valverde shows how various types of funding grants, from variable grants that were to be voted on yearly to per diem funding with rewards for collecting donations from non-government sources, reflect beliefs about an institution’s role in Ontarian society, both pre- and post-Confederation.[10] Following Valverde’s example, this article examines the changes in funding of the asylum in order to highlight changes in its perception, initially as a charity and finally as an education institution, funded mostly by provincial governments. Valverde’s distinction between charity and philanthropy is used throughout to highlight the differences in fund-raising approaches that Fraser undertook:

Charity, the traditional means of relieving poverty, was largely individual and impulsive, and its purpose was to relieve the immediate need of the recipient while earning virtue points for the giver. Organized charity or philanthropy sought to eliminate both the impulsive and individual elements of giving.[11]

Evidence for the association between changes in funding and in public perceptions comes from the press and from municipal and provincial government officials.

Paula Maurutto further develops the history of the mixed social economy by describing the mechanisms by which the Ontario provincial government regulated those charities that were ostensibly not under government control. Maurutto focuses on “administration techniques” — yearly reports, regular inspections, and usage statistics — and how these can “shed much light on shifts in policy and programming.”[12] This article uses the administrative records of the asylum to trace changes in fund-raising techniques which, in turn, reflected and influenced changes in government perceptions of the work that Fraser and the Board of Managers performed. The Annual Reports’ lists of students, their ages, and their home towns illustrated both the board’s desire to present the asylum as an institution that transcended geographic boundaries and demonstrated to municipalities and the provincial governments why their funding dollars were necessary. As Fraser made clear through his campaigns, the asylum was not only providing services to children of Halifax, but also to children of Cape Breton, Pictou County, Lunenburg and elsewhere in Nova Scotia (as well as New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island). The Annual Reports also detailed not only the funding the asylum received, but also how that funding was spent, which in turn was part of the argument that was used to gain additional donations and government financial support, an interconnected system that is also discussed in Tillotson’s work on charitable fund-raising and the welfare state in twentieth century Canada.[13]

During the foundation and early years of the asylum, the Board of Managers and, after 1875, Superintendent Fraser worked in tandem to develop the image of the asylum as a public good, one that would be the best application of donations for the long-term betterment of society, not only in Halifax but across the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland. However, there was a sharp decrease in funding from the Nova Scotia government just as the asylum was gaining more students in the late 1870s, from a high of $1,250 per annum to only $800.[14] As a result, the Board of Managers and Fraser redoubled their efforts, determined to demonstrate that investing in the education of blind students was also a “public good” that should be paid for through taxation, as was already true for non-disabled students in Nova Scotia, in addition to donations from the general public to support specific goals. This campaign succeeded in 1882, with the provincial governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick agreeing to pay all expenses (save travel and clothing) for students from their provinces attending the asylum, in turn gathering half of the required grants from the students’ home municipalities. This lengthy campaign also increased charitable giving to the asylum, as well as increased the number of students that attended and the distance from which they came.

By the end of the campaign for free education for the blind, the asylum was receiving students from all across Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Fraser and the Board of Managers used nearly identical arguments on both the charitable public and the governments of the Maritime Provinces to gain funding to great success in Nova Scotia. The core of these arguments was that providing impulsive charitable support was not as effective in meeting the long-term needs of blind children and adults as regular philanthropic support would be; individual and impulsive charitable support was too variable to provide a solid platform for the asylum’s mission. Ongoing, philanthropic tax-based support would be organized, consistent, and aimed at ensuring proper education and technical training for recipients.[15] By providing guaranteed funding for the asylum and supporting the aims of Fraser and the Board of Managers, neither the governments nor the general public would be subjected to continual sentimental charitable appeals on behalf of blind adults. In addition, the arguments used by Fraser and his supporters in Nova Scotia also described the “rights of all Nova Scotians,” including blind children, to free education, emphasizing not their difference but their similarity to children across the rest of the province.

The Annual Reports, as regularly produced public documents, present the public face of the asylum and show the change in arguments presented over time regarding funding. In addition, examining the language used in these reports can give insight into how the Board of Managers and Fraser asserted both the needs and rights of blind people. The Annual Reports included financial information about the asylum, listing donations from individuals and churches as well as the direct financial outlay of the governments. Examining these reported financial records not only shows why the Board of Managers and Fraser may have found it financially necessary to argue for the right of blind children to a publicly funded education, they also show how this funding led to an increase in enrollment and gave the asylum the financial stability it needed to extend its services beyond basic education within its walls. They also serve as an accountability report, in that they highlight the successes of graduates in addition to the successes of services, such as the Circulating Library for the Blind and the Home Teaching Society.

These Annual Reports are supplemented by the Minute Books, private reports intended to be read only by a select few. The minutes give a clear idea of how little of the board’s attention was given over to the day-to-day running of the asylum, such as determining appropriate classwork. Instead, the board, whose members were rarely identified by name in the minutes, was involved mainly in the logistics of funding and raising awareness of the asylum’s work for blind children, and later blind adults, across the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland. Reading the minutes in conjunction with the public Annual Reports makes it possible to trace how these campaigns went from concept, to delivery, to outcome. The minutes also demonstrate the immediate results of these campaigns: they include the record of funds raised during tours, as well as describing the outcomes of meetings with government officials.

While these sources are useful for discussing funding, the asylum’s programs within and outside its walls, and the perceptions of the press and government about both, they do not give any direct insight into the opinions of two important groups: the students who attended the asylum and their parents. Inferences can be drawn from how the Annual Reports discuss parents and the need for teachers, clergy, and neighbours to advise the asylum of any potential students that parents may have been unwilling or unable to send to Halifax; however, no letters from parents appear to have survived, and the minutes do not record any contact from parents. Likewise, students are talked about, either as success stories in the Annual Reports or as employees of the asylum after graduation, but rarely talked to, except when addressed en masse by religious leaders or politicians during public meetings where they are reminded to be grateful for their opportunities. Thus, while this article is presented as part of disability history, it is not a history of the experiences of the majority of blind people in the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland, but a history of how élites, primarily those within Halifax, perceived the place of education for blind children: first as a charitable impulse, then as a right offered to them as citizens.

The early Annual Reports emphasized the distinctive forms of training that the asylum offered to the blind children in its care, a strategy that marks this as a charitable-style appeal. The president of the Board of Managers, James F. Avery, used his Manager’s Reports to advise current supporters and potential new donors of the technical training provided to students. These demonstrated that the asylum was meant as more than a warehouse for blind children. Rather, it was meant to be an educational facility that prepared students for work — either domestic or technical — after leaving. In the second of these reports, Avery noted that the girls were continuing to learn bead and wool work, while the boys were learning how to seat cane chairs. As well, the report advised readers that the asylum had hired a vocal and instrumental music teacher, as educated blind people often became organists in churches. Avery also highlighted the potential for the students to become music teachers themselves. Over the next three years, corn broom making and pianoforte tuning were added to the industrial training for boys, while learning how to use a sewing machine was added to the domestic training for girls. The Annual Reports advised when additional tools for this training were purchased, such as when the pipe organ and piano were purchased in 1873. Avery also used the reports to encourage the people of Halifax to take advantage of the students’ training; for example, the price of getting a cane chair repaired was set at 50 to 60 cents, which was lower than the cost of having the same work professionally done.[16]

After the Board of Managers hired Fraser as superintendent, he advised the board that they needed to broaden their efforts to reach out to potential new donors. In 1872, the board had agreed the best course of action in gaining government grants was to send copies of the Annual Report to the provincial secretary when making the request. Fraser’s proposal in March 1874 of holding an exhibit at the Legislature — likely inspired by Samuel Gridley Howe’s similar demonstration to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1832 — was quickly accepted and arranged for the end of the month.[17] That same year, Fraser led the first of many concert tours around Nova Scotia, visiting 27 cities and towns. Accompanied by teacher Catherine Ross, steward W.J. Dilworth, and six students, he used the opportunity not only to raise awareness of the asylum and its goals, but also to gain additional charitable donations from the public. Fraser reported revenue of $413, enough to pay every member of the concert tour (including the students), as well as put $200 toward the purchase of a new organ for the asylum. The success of this tour was replicated many times, with Fraser reporting to both the Board of Managers and the readers of the Annual Reports the number of towns visited and the amount of money collected in each.

In 1879, Fraser reported having visited every county in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, as well as most of Newfoundland, giving concerts in 75 towns and cities. This method of raising public awareness, both of the existence of educational institutions for disabled students and the methods used in teaching there, was common. The Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Halifax also used public demonstrations for fund-raising and awareness-building, as did many residential schools for blind and deaf children in the United States. These tours gave proof of the successes discussed in the Annual Reports, allowing people to see for themselves what the institutions were accomplishing.[18] A typical demonstration, again inspired by Howe, would have students perform a variety of vocal and instrumental pieces, answer “the most complicated questions in mental arithmetic,” and read aloud from raised-print books, all demonstrating the efficiency and usefulness of the education offered at the asylum, as well as allowing the general public to compare it to the education offered to sighted student.[19] In tour years, the asylum consistently had marked increases in charitable donations from private individuals (the Annual Report for 1879 reported $1,161.27 in donations that year, up from $698.44 the previous one), as well as an increase in students the following year.[20]

In discussing Howe’s presentations, Mary Klages makes clear the sentimental intention of these tours. While Howe, like Fraser, wished to have his students perceived as equal to their sighted counterparts, these demonstrations were meant to create an emotional bond, based on pity, between “the blind student and the sighted public.”[21] This “more immediate and more powerful stimulus to the audience’s feelings” was carefully calculated, placing the children — rarely named in reports on these tours — as objects of pity.[22] These tours, while successful in generating charitable donations, thus undermined the project of presenting blind children as equal to their sighted counterparts.

Fraser’s first tour had also made him aware that there were many potential students who were not being sent to the asylum. In 1875, he requested that the board seek out more information about the status of blind people throughout the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland.[23] During his next tour he sought out potential students and directly evaluated their eligibility for enrolment. That year’s Annual Report included Avery’s admonishment that parents were not doing enough to ensure their children were receiving a proper education: while there was room for 50 students that year, only 18 were in attendance. Fraser’s Superintendent’s Report was more direct: he pointed out that there were 15 students in Nova Scotia and 35 students across New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland who should have been attending the asylum but were not.[24]

Having identified the potential for recruiting more students, the Board of Managers and Fraser began a multi-pronged plan to increase awareness of the asylum as an educational institution. This included presenting a variety of arguments in the Annual Reports, increasing the tours throughout the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland, and direct lobbying of the provincial and dominion governments. Fraser also began to encourage the public, especially clergy, doctors, and teachers, to report the existence of suitable students who had not been sent to the asylum yet, despite being of age. These campaigns were successful, although not immediately.

Fraser and the board believed that part of the reluctance of parents to send their children to the asylum was fear that it was not an educational facility, but a hospital or even a sanatorium. In 1876, Fraser wrote in the Annual Report that calling it an “asylum fails to set forth the educational character of the Institution,” while the Manager’s Report (that year written by Vice President of the Board, John S. MacLean) reminded readers that the asylum was really a school.[25] However, changing the name was not simply a matter of their will alone. An act of the Nova Scotia government was necessary, as the asylum’s funding came from the Act to Incorporate the Halifax Asylum for the Blind. Changing the name was finally successful in 1879, with the passing of the Act to Incorporate the Halifax Institution for the Blind; that same year, both Fraser’s and MacLean’s report made certain to remind readers that the asylum was open to students throughout the region.

After the asylum’s formal name change, the next step in attracting new students was to show that the technical training students received had enabled both male and female graduates to gain employment, the latter necessary as marriage rates for blind women were very low.[26] MacLean described the asylum as “gradually taking [its place] in usefulness amongst the benevolent Institutions of the country,” while Fraser reported that many graduates of the asylum were fully supporting themselves as pianoforte and cabinet organ teachers, as well as pianoforte tuners; he also reported that the students were beginning to receive awards for their work, such as a Certificate of Merit awarded for a rattan mat sent to an exhibition in Truro, Nova Scotia.[27] Attending the asylum, Fraser wrote, “enable[d] graduates to get jobs, while at the same time reliev[ed] the country from the support of a non-working class.”[28] Two years later, Fraser reported that four of the students had received their tuning certificates and were now regularly working as pianoforte tuners.[29] According to Fraser, graduate R.M. McLean was the first of many students reported as teaching large music classes across the province, while Ainsley Shaw was a successful entrepreneur, running a small general store in Musquodoboit, Nova Scotia. Some other graduates engaged in activities such as managing a grist mill or manufacturing venetian blinds.[30]

Furthermore, Fraser and the board repeatedly chose to hire male graduates of the asylum as educators, demonstrating to the public the employability of their graduates, as well as ensuring that blind students would know that blind adults could have successful careers. The first of these was David Baird, who attended until 1878 and was hired as a Trades Instructor in 1879. Daniel M. Reid, who attended until 1875, was hired as a piano and piano tuning teacher in 1885, after six years working in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.[31] Arthur Chisholm left the asylum in 1878 to pursue further education at the Berlin Conservatory of Music; he returned to teach in 1886.

In addition to the campaign to increase the public’s awareness of the asylum and its usefulness as a public good, the Annual Reports also began the process of enlisting the public in finding and alerting the asylum to potential students who were not sent to Halifax to take advantage of the opportunities there. MacLean’s 1875 Manager’s Report called on “members of the Legislatures, clergymen, medical men and merchants to help us in our good work, and whenever they find a blind child to use every exertion to have him or her forwarded to us.”[32] MacLean further admonished parents for letting their children grow up ignorant out of misguided kindness and a desire to keep them close at home. As far as MacLean was concerned, the best way to ensure blind children could grow into self-sufficient adults was to send them to Halifax, regardless of their parents’ fears.[33]

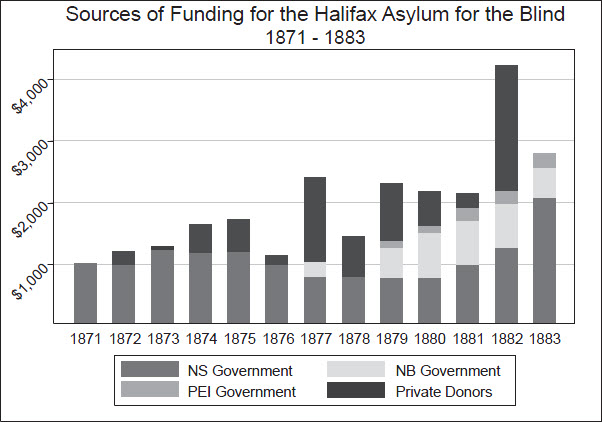

These efforts, spearheaded by Fraser, were very successful, both in terms of increasing numbers of students and in increasing the amount of charitable donations the asylum received from the general public. Between 1872 and 1882, enrolment more than doubled, with students coming from all three of the Maritime Provinces (see Figure 1). Donations and grants to the Asylum more than trebled over the same period of time (see Figure 2). In addition, sources of donations and grants broadened. While funding in 1872 came almost entirely from a grant of $1,000 from the Nova Scotian government, with smaller amounts from church collections and charitable donations from other sources, in 1882 funding sources included these in addition to grants from the governments of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick, and numerous legacies from private individuals. In the ten years between, the asylum also held successful targeted campaigns to raise funds for an organ (1874), a gymnasium (1877–1878), renovations on the workshops (1878), a piano (1879), and the Circulating Library for the Blind (1880), as well as raising funds in three concert tours.

Despite these successes, however, the asylum continued to struggle for enough funding to cover the full cost of educating the students.[34] Even though the asylum was attracting more students, there was not always a comparable increase in the funds available, as is apparent when comparing Figure 1 and Figure 2. In 1877, the Nova Scotia government reduced their regular grant from $1,000 per annum to $800; in that same year Fraser wrote that in Ontario and in several other countries, blind and deaf students were included in free education acts.[35] The impact of this cut in funding would likely have been greatest in 1878: while the asylum had more students that year than ever before, it had over $1,000 less in charitable donations and grants from 1877. By 1879, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island had begun to provide regular grants; however, Fraser reported that the grant from Prince Edward Island only covered one-third of the cost of educating the students from there.[36] While the board and Fraser regularly targeted Newfoundland for both recruitment drives and fund-raising drives, neither had been very successful: donations did come in from charitable Newfoundlanders, but no students arrived for education at the asylum.

In response to the lack of dependable government grants and the difficulties in raising sufficient charitable funds from individuals, Fraser and the board refocused their efforts, this time on campaigning for free education to be extended to blind students. They used many of the same arguments that had been successful in encouraging private individuals to donate to the charitable cause of the asylum, but included further arguments to present the asylum as a philanthropic cause worthy of the same guarantees in funding granted to education for non-disabled students. In December 1879, just before the board and Fraser expected the Free Education for the Blind Act to be presented to the Nova Scotia Legislature, Avery wrote that both the Asylum for the Blind and the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb should be “moved from the list of charitable Institutions to that of the Public Educational Schools of the province,” while Fraser published a collection of essays on the importance of education for blind students.[37] The collection included an essay from Samuel Gridley Howe on the impact of education on Laura Bridgman and Oliver Caswell, both of whom were deaf-blind; an essay on the attainments of educated blind people by the director of the New York Institute for the Blind, Stephen Babcock; an article about the impact of musical education for blind students reprinted from the London Mirror; details on employment opportunities for blind adults trained in pianoforte tuning; and two articles by Fraser himself about the positive impact education had on blind pupils, one comparing educated and non-educated blind people, the other discussing the importance of physical education in keeping blind children and adults independent. This book furthered the message that educating blind children had long-term benefits, both to students and society. According to Fraser, uneducated blind men and women were mean, depressed, and poor; educated ones could support themselves and contribute to society.[38] The asylum, went the separate arguments presented by Avery and Fraser, was no more a charity than was any other educational institution in Nova Scotia.

The government of Nova Scotia had already begun to receive arguments that the asylum was an educational institution rather than a charitable one. The 1878 Report from the Committee of Humane Institutions, presented to the Legislative Council of Nova Scotia on 26 March 1878, argued that the asylum was “purely of an educational character, having for its object the imparting to the blind such instruction as that given in common schools of the province …. The Committee are of the opinion that the Institution has a just and urgent claim upon the funds of the Province.”[39] Yearly, the Committee on Humane Institutions praised the asylum as an institution, including describing the asylum and its managers as “giv[ing] satisfaction to the general public” and “enabling [the pupils] to obtain a comfortable living and become useful members of society.”[40]

In 1880, Fraser wrote that the government had listened to their requests and planned on discussing an act to give free education to blind students in 1881. To support this, he detailed two arguments in the Annual Report that year. First, he discussed the impact of charity on both the public perception of blind people and on blind people’s perception of themselves, saying that charity denied blind people “the exercise of that self-reliance in the blind so essential the development of true manhood.” Second, he pointed out that the wealth in Canada was too diffuse for “comparatively few benevolent men” to support blind people financially. As a result, he argued, it was in the best interests of the blind to remove the dependence on charity and instead have government support for the education of blind students assessed in the same way that the costs were assessed for educating sighted students.[41]

The Proceedings of the Nova Scotia Legislature for both 1880 and 1881 do not indicate that any discussion or debate regarding free education for blind students took place in the lower chamber. There are references to a petition from the asylum in the 1879 proceedings, although the text of the petition is not included. The petition itself is discussed by both representatives from Inverness County, Doctor Duncan J. Campbell (Liberal) and Alexander Campbell (Conservative). Dr. Campbell summarized the petition as “the petitioners … desired that the government or some hon [sic] member of the government or legislature would introduce a bill to compel every county in the province … to tax the county for the maintenance of such pupils,” who had been sent to the asylum. Like Fraser, Alexander Campbell found it “strange that the house should have forgotten these poor sufferers, while … incurring so much expense in the education of those who had all their faculties.”[42] Doctor Campbell referred to the matter being put before the Committee on Humane Institutions; however, there was no follow-up in the Legislature.

Fraser and McLean both reported in the next Annual Report that the bill had not been presented to the Legislature. According to Fraser, the primary obstacle had been the municipalities of Nova Scotia:

From personal knowledge the favourable view taken of it by a majority of the representatives and feeling certain that a wise and judicious Act to provide free education for the Blind would be cordially supported by every humane and right-thinking man in the Province, we felt certain that the Government would bring forward some measure that would secure to the Blind equal educational advantages to those enjoyed by their more fortunate brothers and sisters. That they did not do so is attributable to the fact that some of the Municipal counties objected to the introduction of any Bill for this purpose which would necessitate an increase being made to the Municipal taxes. This we consider was a reasonable objection on the part of the Municipalities, but we cannot but think that if the Councilors had thoroughly understood the question and considered it in all its phases, they would have recognized the principle of equal rights which it involved, would have waived their objection, and would have mainly supported the Government measure. As it was the Government did not deem it expedient to bring forward the Bill. In view of this fact, I resolved to publically advocate the claims of this class in every part of the Province, and endeavour if possible to obtain the sense of the people upon this question, with this end in view.[43]

Fraser approached the Board of Managers about his proposed speaking tour on 6 June 1881. He suggested the first speech be given in Halifax at the Academy of Music. The board readily agreed to the proposal, forming a special committee to plan the first event. The committee was to arrange any necessary details for the speech and subsequent formal resolution regarding educational funding in Halifax.[44]

MacLean, Fraser, and another member of the board, W.H. Neal, arranged for the public meeting to be held on 16 June 1881. Fraser arranged printing and distribution of 1,000 invitations to the event, while MacLean arranged for A.G. Archibald, the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia; Stephen Tobin, the mayor of Halifax (and former member of the asylum’s board); and John Y. Payzant, the warden of Dartmouth, not only to appear as part of the proceedings but also to present and second the resolution they wished passed. Invitations also went out to the military command at the Halifax Garrison, members of both the provincial and dominion legislatures, and clergy to appear on stage in support of the resolution, alongside the Board of Managers.[45]

The meeting also garnered attention in the press. The Morning Herald discussed the upcoming meeting multiple times in the week and a half before it was to be held, describing it in one column as “a presentation of the claims of the blind to the same privilege of free education, which is now the birth right of every Nova Scotian, but which has not yet been extended to those deprived of sight … the lecture will be of very great interest.”[46] Both the Morning Herald and the Morning Chronicle announced the meeting, albeit emphasizing different aspects: while the Herald announced on 9 June 1881, that a “public meeting for the purpose of considering the education of the blind” was to be held, the Chronicle described it on 14 June 1881, as a lecture from Fraser “in which he will discourse on the cause and effect of blindness, eminent blind men, etc.”[47] The newspapers carried identical announcements indicating that, “in consequence of an important gathering … in the interests of the Institution for the Blind,” a planned temperance lecture was postponed to the day after Fraser’s presentation, indicating how important Fraser’s presentation was expected to be.[48] The weekly Presbyterian Witness and Evangelical Advocate also “heartily endorse[d] any movement that would promote the welfare of those deprived of sight.”[49]

While previously Fraser’s arguments in favour of education for blind children had focused on the benefit to the community that educating these students provided, his speech at the public meeting took a different direction: Fraser argued that blind children had the same right to education “as their more fortunate fellows who were not deprived of sight.”[50] While some of the speech dealt with the successes of educated blind men and women in the United States and England, the importance of early intervention in ensuring blind children gained independence and self-sufficiency, and the high standards of education offered by the asylum, Fraser’s primary argument was that the time for effective charitable fundraising had passed: “[T]he funds are limited, the limit has been reached, and the question now is: How can the education of the blind be provided for?”[51] Fraser asked those present to endorse the Board’s plea to the government of Nova Scotia, making it clear that he would be conducting similar public meetings in as many Nova Scotian counties as possible; without the political support of the counties and a commitment to paying part of the cost directly, the act to properly fund the asylum would not be passed.[52]

Halifax newspapers wrote positively of the event, expressing support and enthusiasm for the idea of free education for the blind. The Morning Herald report underscored Fraser’s appeal to universal rights and his rejection of the charity mode of funding for blind education:

Mr. Fraser, in closing, said that sympathy might be aroused by his making an appeal on the ground of humanity; that, he did not intend to do but would make the call on the ground of justice and right. It was not too much to ask for the blind the same opportunities given to others. He asked not for alms, but help; not for charity but for that which is the birthright of every Nova Scotian.[53]

The Morning Chronicle echoed the support, with its report on the meeting being front page news the Saturday following the event. Describing the “benefits of special education” for successful blind adults, the Chronicle argued that, without this benefit, society would be left with “the burden of their support.” It described the potential act as an extension of the Free School Act of Nova Scotia, arguing that direct taxation for education was already a reality and this was a logical extension:

The principle of giving free education to the young of our land had been years ago established in this Province. The common schools did not afford such facilities as to give education to the blind hence a class of the community were deprived of that which the law said all were entitled to …. As it was impossible to educate each blind person in his or her own district, it was only fair to ask the rate payers to contribute a small percentage of the cost per head of educating the blind at a central institution …. He didn’t ask for charity for the blind, but for justice.[54]

Fraser delivered a version of his speech in 44 other communities throughout Nova Scotia during June and July. The Herald reproduced his itinerary and made follow-up reports on some of his meetings, describing them as “enthusiastic,” with resolutions being “heartily endorsed” and collections being taken up.[55] Both secular papers also reported on the graduation exercises of the asylum held at the end of June, and each took the opportunity to remind readers of the importance of the movement for free education for the blind. “Ex-Mayor Dunbar … endorsed the movement now being made by the Principal to secure to the blind a free education, and felt confident that the movement would be successful” appeared in the Morning Herald. “The gathering was addressed by Rev. Messrs Simpson and Smith, Hon. Samuel Creelman [a member of the Committee on Humane Institutions], and ex-Mayor Dunbar, all of whom expressed their hearty endorsation [sic] of the movement now on foot to give the blind a free education, as is given to other children,” reported the Chronicle.[56] The Witness went further still, praising Fraser’s work as “truly Christ-like.”[57]

In March of 1882, the provincial secretary of Nova Scotia, Simon H. Holmes, formally introduced the Act in Relation to the Education of the Blind, describing it as “the result of a consultation that had been held between the Managers of the Institution for the Blind and the Government.” The act granted $120 per Nova Scotian pupil who attended the asylum, with $60 coming from the province and the other $60 from the county that the student could claim residence in. The act passed unanimously through both houses with no debate recorded.[58] “[O]ur pupils have now attained a legal status in the community, they are no longer waifs to be looked after by the charitably disposed, but are … entitled to participate in the educational advantages of the country,” MacLean wrote in the following Annual Report, a sentiment echoed by Fraser.[59] New Brunswick, Fraser advised, also continued to provide an equal grant to the asylum, although this was not enshrined in law as it was in Nova Scotia.

The asylum’s successful petition in Nova Scotia did not lead to successes in the other provinces. In the same Annual Report that Fraser wrote about the Nova Scotia act and support from New Brunswick, he complained bitterly that the Prince Edward Island government continued to underfund their students, sending only $200 when $240 was needed. He called upon “the philanthropists of Charlottetown” to lobby the government there to “afford [the blind] some chance of raising themselves from helpless dependence.” For Newfoundland, however, the situation was more complicated. Despite several students applying and being accepted at the asylum, no student had actually entered. Fraser blamed this on both the distance from Newfoundland to Nova Scotia (a journey of more than 1,000 kilometres) and his inability to meet in person with the parents of potential students. In both cases, Fraser expected no less than the grant given by Nova Scotia, for the same reasons: education of the blind was as much a right as education for the sighted.

By using a rights-based argument for education funding, Fraser was in turn asserting that blind children were exactly like sighted children, just lacking in the ability to see. This was further reinforced through the public demonstrations of what the children were learning at the asylum, which was very similar to the curriculum for sighted children.[60] By turning away from the charitable model, Fraser also presented graduates of the asylum as competent, educated adults, rather than as life-long dependents. Blind men and women, like sighted ones, were citizens of Nova Scotia, and thus should have access to the education rights that sighted people enjoyed.

By exploring both the charitable and philanthropic eras of funding for the Halifax Asylum for the Blind, we can gain a clearer idea of the public perception of children and adults with disabilities in the nineteenth century. When the asylum needed to compete with a variety of charitable causes for donations from private individuals, churches, and the provincial government, the board struggled to find sufficient funding. Fraser, aware of the successful fund-raising techniques employed by educational institutions for blind children in the United States, turned to a philanthropic campaign based on those techniques and designed to develop the image of the asylum as a public good that would lead to the long-term betterment of society.

This article has traced how Fraser’s campaign altered the public’s perception of the asylum, drawing on Valverde’s distinction between charity and philanthropy to demonstrate the success of the campaign. Before, the asylum was a charity, supported by impulsive donations from a supportive, if pitying, public. Fraser and the board appealed for this charity presenting it as an investment that would eliminate future charitable support of a non-working class. While this technique was initially successful in increasing both available funds and the number of students, the results were too variable to provide a solid financial platform for the asylum. As a result, Fraser altered his campaign: blind children, like sighted children, had a right to education. Through this argument, he was able to change the perception of the asylum into an education institution, one that should be funded through regular, philanthropic funds raised through taxation.

After this successful campaign, Sir Charles Frederick Fraser continued to advocate for blind people in the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland, broadening his appeal beyond education rights for children to include the educational and employment needs of blind adults. Initially, Fraser was successful; he began a circulating library of raised-print books for blind adults and founded a home teaching society that taught those blinded in adulthood how to read raised print. However, the growth of the industrial economy in the Maritime Provinces led to long-term employment difficulties for blind adults. As a result, a number of successfully-employed blind adults formed the Maritime Association for the Blind, with the aim of finding appropriate employment opportunities for working-class blind men. Increasingly aware of the financial difficulties faced by both blind adults and the asylum itself, Fraser joined with the Association in calling for the foundation of sheltered workshops that would guarantee employment for blind men. When this campaign was successful, Fraser returned his attentions to the education of blind children, allowing the Canadian National Institute for the Blind to become the primary face of blind advocacy in the Maritime Provinces and across Canada.

Figure 1

Enrollment at Halifax Asylum for the Blind 1871-1885

Figure 2

Source of Funding for the Halifax Asylum for the Blind 1871-1883

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Joanna L. Pearce is a PhD student at York University in Toronto.

Notes

-

[1]

I would like to thank Drs Shirley Tillotson, Janet Guildford, and Jerry Bannister, as well as the journal’s anonymous reviewers, for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. I would also like to thank the audience members at Congress 2012 for their helpful and supportive comments.

-

[2]

“Honoured on his Golden Jubilee,” Morning Chronicle (20 June 1923), 1–2.

-

[3]

“Fifty years of great service recognized at Golden Jubilee Night,” Morning Herald (20 June 1923), 1, 3.

-

[4]

“Address Presented to Sir Frederick Fraser on his Fiftieth Anniversary as Superintendent of the Halifax School for the Blind,” The Fifty-third Report of the Board of Managers of the Halifax School for the Blind (hereafter Annual Report (School)), (Halifax: The School, 1923), 3.

-

[5]

For consistency purposes, the term “asylum” will be used for the Halifax Asylum for the Blind throughout this work, except within quotations.

-

[6]

Judith Fingard, The Dark Side of Life in Victorian Halifax (Porters Lake, N.S.: Pottersfield Press, 1989), 13.

-

[7]

Janet Guildford, “Public School Reform and the Halifax Middle Class, 1850–1870” (Ph.D. diss., Dalhousie University, 1990), 1–322.

-

[8]

Mary A.E.A. McNeil, The Blind Knight of Nova Scotia: Sir Frederick Fraser,1850–1925 (Washington, D.C.: The University Press, 1939); David Allison, History of Nova Scotia: Biographic Sketches of Representative Citizens and Genealogical Records of the Old Families, Vol. III (Halifax: A.W. Bowen & Co, 1916), 470.

-

[9]

Nancy Fraser and Linda Gordon, “‘Dependency’ Demystified: Inscriptions of Power in a Keyword of the Welfare State,” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 1, no. 1 (January 1994): 4–31; Mariana Valverde, “The Mixed Social Economy as a Canadian Tradition,” Studies in Political Economy 47 (Summer, 1995): 33–60; Paula Maurutto, Governing Charities: Church and State in Toronto’s Catholic Archdiocese, 1850–1950 (Montréal-Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003); Shirley Tillotson, Contributing Citizens: Modern Charitable Fundraising and the Making of the Welfare State (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008).

-

[10]

Valverde.

-

[11]

Mariana Valverde, The Age of Light, Soap, and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885–1925 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991), 19.

-

[12]

Maurutto, 8.

-

[13]

Tillotson.

-

[14]

See Figure 2. 1877 was the first year that the Nova Scotia government provided only $800 in funding. That same year, New Brunswick provided its first funding grant of $240, but the following year did not provide any money at all. Regular grants from New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island began in 1879.

-

[15]

Valverde, The Age of Light, 19.

-

[16]

The Second Report of the Board of Managers of the Halifax Asylum for the Blind (hereafter Annual Report (Asylum)), (Halifax: The Asylum, 1872), 6; Third Annual Report (Asylum), 1873, 7, 8; Fourth Annual Report (Asylum), 1874, 6; Fifth Annual Report (Asylum), 1875, 8.

-

[17]

Nova Scotia Archives (hereafter NSA), Halifax School for the Blind fonds, RG 14, Series ‘S’, vol. 161, Board of Managers Minute Books (hereafter Minutes), 5 February 1872. Minutes, 2 March 1874. Mary Klages, Woeful Afflictions: Disability and Sentimentality in Victorian America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 112. Howe’s demonstration led to an annual grant of $6,000 for the Perkins Institute for the Blind.

-

[18]

Klages, 112.

-

[19]

“The Blind Asylum: Exhibition at Argyle Hall,” Morning Chronicle (1 April 1874), 3; “Institution for the Blind: Closing Exercises on Tuesday,” Morning Herald (23 June 1881), 1. Klages, 112.

-

[20]

The Ninth Report of the Board of Managers of the Halifax Institution for the Blind (hereafter Annual Report (Institution)), (Halifax: Nova Scotia Printing, 1880), 7.

-

[21]

Klages, 111.

-

[22]

Ibid., 114.

-

[23]

Minutes, 3 March 1875.

-

[24]

Fifth Annual Report (Asylum), 1875, 7, 12–13. Fraser does not seem to have made a report to the Board of Managers that included the names or locations of these potential students.

-

[25]

Sixth Annual Report (Asylum), 1877, 15. Stigma around the term “asylum” as a descriptor was a factor in name changes of other institutions in Canada. In 1908, C.K. Clarke, the director of the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, described the term asylum as “‘repulsive’ to family and friends” due to the “public prejudice” against the term. See Geoffrey Reaume, Remembrance of Patients Past: Patient Life at the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1870–1940 (Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press Canada, 2000), 183.

-

[26]

In 1901, Fraser revealed that only four percent of female graduates were married, compared to 20 percent of men. Thirtieth Annual Report (School), 1901, 15.

-

[27]

Sixth Annual Report (Asylum), 7, 10, 11.

-

[28]

Seventh Annual Report (Asylum), 1878, 13.

-

[29]

Eighth Annual Report (Institution), 1879, 15.

-

[30]

Thirteenth Annual Report (Institution), 1883, 11; Sixteenth Annual Report (Institution), 1886, 8, 9.

-

[31]

Fifteenth Annual Report (Institution), 12.

-

[32]

Fifth Annual Report (Asylum), 1875, 8.

-

[33]

Eight Annual Report (Institution), 1879,10–11.

-

[34]

MacLean wrote in 1880 that the cost per pupil was $150. Funding from all sources that year totaled only $110 per registered pupil. Tenth Annual Report (Institution), 7, 16.

-

[35]

Seventh Annual Report (Institution), 13.

-

[36]

Ninth Annual Report (Institution), 14.

-

[37]

Tenth Annual Report (Institution), 6; C.F. Fraser, Fighting in the Dark (Halifax, N.S.: The Asylum, 1879).

-

[38]

Fraser.

-

[39]

Journals and Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Province of Nova Scotia (hereafter Legislative Council), Session 1879 (Halifax, N.S.: Robert T Murray, Queen’s Printer, 1879), Appendix 22, 3–4.

-

[40]

Ibid., Session 1883, Appendix 19, 6; Ibid., Session 1884, Appendix 17, 2.

-

[41]

Tenth Annual Report (Institution), 12.

-

[42]

Nova Scotia, House of Assembly Debates and Proceedings, 27 March, 1879, 83 (Doctor Duncan J. Campbell, MLA, and Alexander Campbell, MLA).

-

[43]

Eleventh Annual Report (Institution), 1882, 15.

-

[44]

NSA, Halifax School for the Blind fonds, RG 14, Series ‘S’, vol. 162, Minutes, 6 June 1881.

-

[45]

Ibid., 9 June 1881.

-

[46]

“Fighting in the Dark,” Morning Herald (6 June 1881), 3.

-

[47]

“Education of the Blind” Morning Herald (9 June 1881), 3; “Public Meeting in Aid of the Blind,” Morning Chronicle (14 June 1881), 4.

-

[48]

“Lecture Postponed,” Morning Herald (15 June 1881), 3; “Lecture Postponed,” Morning Chronicle (15 June 1881), 1.

-

[49]

“Lecture on the Blind,” The Presbyterian Witness and Evangelical Advocate (hereafter Witness) (11 June 1881), 1. While it is possible that the weekly Catholic newspaper published at this time, The Casket, also commented on the Halifax lecture or any of the following lectures around the province, little of the paper for the summer of 1881 is available. What exists does not mention the Asylum for the Blind in any capacity.

-

[50]

“The Education of the Blind: Public Meeting in Academy of Music,” Morning Herald (17 June 1881), 3.

-

[51]

Ibid.

-

[52]

Ibid.

-

[53]

Ibid.

-

[54]

“The Education of the Blind,” Morning Chronicle (18 June 1881), 1.

-

[55]

“Education of the Blind,” Morning Herald (24 June 1881), 1; “Free Education for the Blind,” Morning Herald (29 June 1881), 1; “Education of the Blind,” Morning Herald (25 June 1881), 3.

-

[56]

“The Institution for the Blind,” Morning Chronicle (23 June 1881), 1.

-

[57]

“The Blind,” Witness (16 July 1881), 229.

-

[58]

Nova Scotia. House of Assembly. Bill 62, An act in relation to the education of the blind, 27th Assembly, 1882 (assented to 10 March 1882).

-

[59]

Twelfth Annual Report (Institution), 1883, 6.

-

[60]

Again, Fraser was following in Howe’s footsteps. See Klages, 112.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Joanna L. Pearce est candidate au doctorat à York University.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Enrollment at Halifax Asylum for the Blind 1871-1885

Figure 2

Source of Funding for the Halifax Asylum for the Blind 1871-1883