Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the debates over the regulation of pistols in Canada from confederation to the passage of nation’s first Criminal Code in 1892. It demonstrates that gun regulation has long been an important and contentious issue in Canada. Cheap revolvers were deemed a growing danger by the 1870s. A perception emerged that new forms of pistols increased the number of shooting accidents, encouraged suicide, and led to murder. A special worry was that young, working-class men were adopting pistols to demonstrate their manliness. Legislators responded to these concerns, but with trepidation. Parliament limited citizens’ right to carry revolvers, required retailers to keep records of gun transactions, and banned the sale of pistols to people under 16 years of age. Parliamentarians did not put in place stricter gun laws for several reasons. Politicians doubted the ability of law enforcement officials to effectively implement firearm laws. Some believed that gun laws would, in effect, only disarm the law abiding. In addition, a number of leading Canadian politicians, most importantly John A. Macdonald, suggested that gun ownership was a right of British subjects grounded in the English Bill of Rights, albeit a right limited to men of property.

Résumé

Le présent article porte sur les débats entourant la réglementation des pistolets au Canada depuis la confédération jusqu’à la promulgation du premier Code criminel en 1892. Il démontre que la réglementation des armes à feu est un point litigieux et important au Canada depuis longtemps. À partir des années 1870, en effet, les révolvers bon marché sont considérés comme étant un danger croissant. L’idée se profile que les nouvelles sortes de pistolets augmentent le risque de fusillades, incitent au suicide et favorisent le meurtre. On s’inquiète particulièrement de l’adoption du pistolet par les jeunes hommes de la classe ouvrière pour afficher leur masculinité. Le législateur réagit à ces préoccupations, mais avec appréhension. Le parlement intervient pour limiter le droit des citoyens de porter des armes de poing, pour exiger que les commerçants tiennent des relevés de transactions et pour interdire la vente de pistolets aux moins de seize ans. Or, les parlementaires n’imposent pas de lois plus strictes pour plusieurs raisons, entre autres parce qu’ils doutent de la capacité des agents de la paix de les appliquer efficacement. Certains sont d’avis qu’une telle législation n’aurait pour effet que de désarmer les citoyens respectueux des lois. Par ailleurs, plusieurs dirigeants politiques canadiens de premier plan, dont John A. Macdonald, pensent que tout sujet britannique a le droit de posséder une arme en vertu du Bill of Rights anglais, même si ce droit est limité aux propriétaires fonciers.

Corps de l’article

Firearm regulation has been among the most heated political issues in Canada since the École Polytechnique Massacre of December 1989. The introduction of new gun laws by Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, especially the long-gun registry, sparked a furious response. Unbeknownst to most Canadians, however, gun regulation has long been an important and contentious issue in Canada. This paper examines the debates from Confederation to the passage of Canada’s first Criminal Code in 1892 concerning whether and, if so, how, the state should regulate pistols.[1] The spirited discussion about gun culture and firearm regulation offers insights into the perceived limits of state power, the definition of manliness, and the role of British constitutional thought in shaping Canadian public policy.

Cheap revolvers were deemed a growing danger by the 1870s. A perception emerged that new forms of pistols increased the number of shooting accidents, encouraged suicide, and led to murder. A special worry was that young, working-class men were adopting pistols to demonstrate their manliness. Legislators responded to these concerns, but with trepidation. Legislators largely banned the carrying of revolvers, and required retailers to keep records and to sell pistols to people only over 15 years of age. Parliament did not put in place stricter gun laws for several reasons. Politicians doubted the ability of law enforcement officials to effectively implement firearm laws. Some believed that gun laws would, in effect, only disarm the law abiding. In addition, a number of leading Canadian politicians, most importantly John A. Macdonald, suggested that gun ownership was a right of British subjects grounded in the English Bill of Rights, albeit a right limited to men of property. These concerns prevented Ottawa from more aggressively responding to what became termed the “pistol problem.”

In examining debates over the regulation of firearms in the late nineteenth century, this paper considers a largely unexplored topic that demands greater attention. In his study of Canadian gun control legislation from 1892 to 1939, Gerald Pélletier notes that fears of labour radicals and immigrants led to new firearm laws, but he does not explore the development of pre-Criminal Code gun regulation.[2] Philip Stenning’s very brief survey of gun regulation in The Beaver only touches on the 1867 to 1892 gun control regime.[3] In his 2004 Ph.D. political science dissertation, Samuel A. Bottomley surveys Canadian gun laws, although he limits his research largely to legislative materials with the result that several interpretative errors mar his work.[4] Susan Binnie’s fine studies of state responses to social disorder show, as this paper does, that gun regulation often stemmed from concerns with collective violence.[5] However, this paper will amend her suggestion that gun regulation “did not reflect any popular or widely recognized demand for weapons control.”[6] As will be shown, many Canadians in the last quarter of the nineteenth century saw revolvers as an emerging public menace that required greater regulation.

This paper is divided into three parts. Part one examines the technological, industrial, and marketing innovations that made revolvers cheap, accessible, and in demand. Part two briefly surveys the range of perceived social issues caused by the dissemination of revolvers. The political response to the pistol problem is considered in part three.

The Modern Revolver

Technological changes revolutionized pistols in the nineteenth century. By the early nineteenth century, smooth-bore, muzzle-loaded pistols had been in use for several centuries. Most of these were single-shot weapons, although double-barreled pistols were produced, as were so-called “pepperbox” multi-shot pistols. Pepperbox weapons had several barrels that each held a bullet. All smooth-bore pistols had several weaknesses. They were extremely inaccurate even when fired by the best marksmen. A skilled soldier could shoot them accurately only from ten yards. It was also possible for the balls to slip out prior to discharge.[7] Pepperbox pistols had additional weaknesses. They were heavy because of their multiple barrels and were even more inaccurate than single-shot pistols.[8]

Pistol design changed rapidly in the nineteenth century. The most important innovation was the creation of multi-shot revolvers. In Britain, Elisha Collier patented a flintlock revolver in 1818. Samuel Colt patented an even more important innovation in 1835, the first successful “percussion revolver.” This weapon had a revolving cylinder with several chambers. Into each chamber, the shooter loaded gun powder and a ball (or a paper cartridge). In the rear of each chamber, the shooter loaded percussion caps that, when struck, ignited the powder in the chamber. Colt also developed a mechanism that rotated the cylinder when the shooter cocked the gun with the hammer. Despite Colt’s innovations, his revolvers were heavy and expensive, and thus found few buyers. Colt’s company went bankrupt in 1842, although he later reopened his business, which subsequently became the leading handgun maker in America. His manufacturing techniques helped usher in the American system of mass production, which, in time, allowed for the production of large numbers of cheap revolvers.[9]

The design of revolvers continued to improve through the 1850s. Colt remained a major player, although his patent expired in 1857, with the result that other American manufacturers also began producing revolvers, including Remington, Starr, Whitney, and Smith & Wesson. Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson made an important innovation when they began producing the first revolver that fired metal cartridges that did not require percussion caps. Smith & Wesson revolvers could thus be quickly loaded by inserting cartridges into the rear of each chamber of the revolver. Other makers adopted this innovation. For example, Colt began producing “Peacemaker” revolvers with self-contained metallic cartridges in 1872. Gun manufacturers soon introduced two additional innovations in the design of revolvers. First, they developed “double action” revolvers that could be fired just by pulling the trigger, rather than by cocking the weapon and then pulling the trigger. The second innovation was a means of allowing revolvers to be quickly loaded and unloaded. Smith & Wesson developed revolvers with hinged frames in the 1870s. This allowed for the barrel and cylinder to be tipped forward.[10]

Early revolvers were too expensive for mass consumption. Colt initially marketed beautifully-crafted firearms as status symbols, not as weapons for average people. A few gun sellers began advertising revolvers in British North America in the late 1850s and 1860s, although cost made these guns too expensive for most citizens.[11] English firms, for example, took out advertisements in Toronto papers marketing their pricey revolvers. Deane & Son of London offered a new revolver for £7 10s in 1859.[12] In 1863, a six-chamber revolver could be had in Québec for the smaller, but still substantial, sum of £4 4s.[13] An Ottawa retailer offered a variety of revolvers for sale in 1866, the least expensive of which sold for $7.[14]

The price of revolvers declined substantially during the 1870s and 1880s. In part, lower prices resulted from the increased manufacturing capacity created during the American Civil War. The Civil War led to a rapid increase in the number of revolvers manufactured. Colt, for example, produced 130,000 .44-calibre revolvers and 260,000 other pistols during the war, while Remington sold 133,000 revolvers to the Union Army. The end of the Civil War left gun companies with excess production capacity. They responded by producing new inexpensive guns that could be mass marketed to civilians in domestic and foreign markets. As a result, by the 1890s, cheap weapons “offered firepower for the price of a man’s shirt.”[15] Revolvers also became less expensive in Canada. Retailers advertised revolvers in Winnipeg for as little as $1.50 in 1883 and for the same price in 1900.[16] In 1882, Toronto gun seller Charles Stark claimed to carry 50 different styles and makes of revolvers, some of which sold for as little as $1.[17] Among the cheapest weapons sold were poorly-made cast-iron guns, such as the “British bull-dog” revolver.[18]

The number of revolvers in Canada in the nineteenth century is impossible to determine. The challenge of quantifying gun ownership has also bedeviled historians in Britain and the United States. One of the leading historians on gun regulation in England admits that “we have no way of knowing how many Englishmen actually owned firearms.”[19] However, the absence of Canadian revolver manufacturers means that change in the value of imported guns provides some sense of the growing availability of firearms in Canada. For several reasons, however, some care must be taken in considering the statistics. First, government records valued all of the guns that entered Canada, not just of pistols. Second, the official figures undoubtedly underestimated the value of weapons entering the country since many were likely carried illegally across the American border. Nevertheless, the available figures show substantial growth in the level of gun imports. The total value of firearms imported into Canada for domestic consumption rose from $14,902 in 1869 to $102,583 in 1874. The value of imported guns then declined to $52,212 by 1879, before more than tripling to $188,326 by 1883.[20]

Retailers and manufacturers used several techniques to market pistols. American revolver manufacturers that sold their products in Canada sometimes played on the fear of crime, suggesting that revolvers were needed in a modern, heavily-armed society. Remington took this approach in an Ontario advertisement in 1866: “In these days of Housebreaking and Robbery, every House, Store, Bank and Office should have one of Remington’s Revolvers.”[21] Canadian retailers copied this approach. For example, the R.A. McCready Company of Toronto claimed that a revolver in the house “gives a sense of security.”[22] Gun sellers also emphasized the beauty of their guns in an effort to attach status to particular models. For example, a catalogue produced by Toronto gunsmith and gun seller William G. Rawbone stressed the beauty of a new revolver it nicknamed the “Toronto Belle.” Rawbone said that the “entire pistol is polished and nickeled in first-class style, and for smooth, easy working cannot be surpassed.” Rawbone claimed to be the only seller of the gun in Canada, and offered it for the bargain price of $2.75.[23] Retailers also enticed buyers by displaying revolvers prominently in store windows.[24]

The Revolver Problem

While it is difficult to estimate the number of pistols in Canada in the late nineteenth century, import statistics, retail advertisements, and social commentary all suggest that cheap pistols became widely available in Canada by the 1870s. The appearance of such weapons and the lack of government regulation led to a perceived increase in the use of revolvers in shooting accidents, crimes, and suicides.

Canadians blamed revolvers for causing a perceived spike in gun accidents, especially since many of the people who purchased these weapons had not previously owned guns. There had always been gun accidents in British North America. Muskets, for example, occasionally fired prematurely or simply exploded.[25] The growing popularity of rifle shooting in the 1860s also caused men to occasionally shoot each other or themselves by accident.[26] The increased ownership of revolvers, however, especially among young urban men, sparked strong concerns about the possible growth in the number of accidents. These accidents happened in an instant; a moment of bad judgment or bad luck often led to disaster.

Occasionally, accidents occurred when women handled revolvers. In Saint John, New Brunswick, for example, a 13-year-old girl was shot after a woman picked up a revolver and in a jocular fashion said, “Leona, I’ll shot you.” The gun went off, the bullet entered the girl’s breast, penetrated her lung, and lodged behind her shoulder blade.[27] Another incident occurred in Brockville, Ontario, in 1882, when Ida Quigg, aged 22, accidentally shot herself with a loaded Smith & Wesson revolver that had been left on a dresser. She apparently caught the revolver while dusting, causing it to discharge into her stomach.[28] More frequent were accidents involving young men who carelessly handled (or handed around) weapons when amongst friends. A few examples can illustrate this common problem. In 1881 19-year-old year old George Merritt shot and killed himself while cleaning his revolver. Merritt had “displayed an intense fondness for firearms,” and had several revolvers in his possession which he had frequently shown to other boys.[29] In Saint John in 1887, John Langan, aged 21, was accidentally shot in the eye and killed when he let his friend look at his revolver.[30] One of the “most unhappy fatalities that has occurred in Toronto for some time” took place in 1891 when a 16-year-old employee was sent to fetch a revolver. On his way back with the gun, a passing workman asked to examine it. It went off, the bullet entering the workman’s brain.[31]

Children were especially prone to shooting themselves, or others, with revolvers. In the nineteenth century, there was no legislation requiring revolvers to be stored safely or unloaded when not in use. Nor were there any age restrictions prior to 1892 regarding who could acquire a pistol. Not surprisingly, children got their hands on guns, and, beginning in the late 1870s, newspapers were filled with stories of tragic gun accidents. For example, in Toronto in 1879, a 13- year-old had a revolver it in his room, which he shared with his nine-year-old brother. The younger child was looking at the gun when it discharged. The bullet entered his face just below one of his eyes, and lodged in his jaw.[32] When George Lyons, aged 15, tried to teach Arthur Mead, aged five, how to shoot a revolver, “Mead transferred one of the cartridges from the revolver to Lyon’s left shoulder.”[33] Such incidents appeared regularly in the press across the country.

Revolvers were a perfect tool to commit crimes because they offered a substantial amount of firepower in a small, concealable package. They were easily hidden in pockets, especially since some tailors supplied men’s trousers with a “pistol pocket.” Senator Robert Read from Ontario complained in 1877 that there was “scarcely a pair of trowsers [sic] made at the present day which was not provided with a pistol pocket in which to conceal firearms.”[34] By 1883, the Toronto World condemned the “great evil of carrying concealed firearms.”[35] The ability to fire a revolver several times in quick succession also made it an especially useful tool for criminals. Shooters could fire multiple rounds to injure or kill several victims, or to ensure a target was dead. So, for example, when a young man in Hamilton sought revenge against the seducer of his sister, he fired four shots from a revolver, severing a leg artery in the alleged Casanova, killing him.[36] Senator Richard William Scott identified the importance of changing firearm technology in 1889. He suggested that the number of murders had gone up in Canada “from four to sixfold, simply from the facility which the revolver affords for taking life.”[37] Newspaper accounts of burglaries and robberies also made frequent reference to criminals carrying revolvers, either to commit the crime or to defend themselves if discovered or pursued.[38]

The revolver was also a perfect tool for suicides and murder-suicides. A revolver was an appealing instrument for ending one’s life for a number of reasons. It was cheap and thus accessible to almost anyone considering suicide. Such weapons could also be purchased by an individual contemplating suicide and then easily hidden until he or she made a final decision. As well, revolvers were simple to use. Any depressed individual could easily load and fire a revolver into their mouth, temple, or chest. Incidents from across Canada illustrate that revolvers became a means for people of all walks of life to commit suicide.[39]

Residents of British North America initially expressed little concern over the introduction of modern pistols even when, in the late 1850s, reports began to appear of criminals using revolvers.[40] Even the prosecution of Patrick James Whelan for using a pistol to murder MP Thomas D’Arcy McGee in 1868 did not lead to expressions of concern over the dangers of the growing availability of revolvers.[41] By the 1870s, however, Canadians began to believe that revolvers represented a growing danger. Many criticized a perceived increase in gun accidents. In describing an accidental shooting with a revolver in Brampton, Ontario, the Globe called it one of those “sad events which results from the careless handling of firearms, and from which the public are being constantly warned.”[42] Another writer emphasized the danger of mixing boys and firearms. “Numerous are the reports of accidents, serious or fatal, resulting from the discharge of firearms,” the writer suggested before offering a “tragedy in two parts”:

I.

Boy,

Gun;

Joy,

Fun.II.

Gun,

Bust;

Boy,

Dust.[43]

A special concern was that revolvers were becoming an integral part of male, especially male youth culture. Commentators suggested that many young men carried cheap, easily hidden, and deadly revolvers as a means of demonstrating their manliness. For example, Liberal Senator Billa Flint claimed in 1877 that the “youth of our land are fast training themselves in the use of firearms, and particularly pocket pistols.” “Mere boys,” he continued, “who could save a little money, used it for the purpose of obtaining pistols.”[44] Lawyer and Conservative Senator Alexander Campbell of Ontario also suggested that young men were increasingly carrying firearms. In the late 1850s, he had “hardly ever heard of young fellows carrying concealed weapons,” but by 1877 it had become “quite common.” He blamed this trend on the idea that carrying a weapon “shows in some way their manliness.”[45] Liberal Senator David Reesor, also of Ontario, suggested that a certain class of young men in Canada was “generally more anxious to possess their first revolver than their first watch”;[46] while Senator James Dever, a Liberal from New Brunswick, claimed that a pistol was becoming “a necessary part of a young man’s outfit.”[47] Young men in Canada’s eastern cities often came under attack for carrying revolvers, although the problem was not strictly an eastern Canadian phenomenon. There were, for example, complaints in Winnipeg. In 1874, the city’s mayor criticized of the growing tendency of men to fire off pistols in city streets, and the Winnipeg Daily Free Press suggested in 1876 that “pistol shooting by boys is becoming common.”[48] By the late 1880s, the revolver was a key piece of equipment for the cowboys of Calgary, where several men were prosecuted for firing revolvers in the city’s streets.[49] The tendency of young men to arm themselves with revolvers, especially in urban areas, also happened in Britain and the United States in the last third of the nineteenth century. For example, Lloyd’s declared in 1868 that “[v]agabond boys have learned to carry revolvers as toys.”[50] By the 1870s, many young men also carried concealed weapons in the United States, where the phrase, “God created men; Colonel Colt made them equal,” became a widely heard refrain.[51]

Critics tried to mock the bravado young men exhibited when carrying a firearm. One writer suggested that the impregnability men felt when handling a gun encouraged shooting accidents. “What cowards women are when there is a gun or a pistol in their vicinity. They will ‘O dear!’ and ‘O, don’t!’ and ‘O, for mercy’s sake!’ and will tremble like a poplar leaf, even though the gun or pistol be without lock, stock, and barrel.” “But a man, how different!,” continued the writer, for he “will take up the weapon with a charming nonchalance, cock it, peer into the muzzle, and give a first-class job for either the doctor or undertaker.”[52] Opponents of the practice of carrying weapons also tried to undermine the association of guns with manliness. For example, in his charge to a Toronto General Sessions grand jury in 1877, Judge Kenneth Mackenzie tried to counter the idea that carrying a firearm was a manly practice. “Nothing can be more at variance with true manliness and manhood,” suggested Mackenzie, “than indulging in those cowardly practices of secreting offensive weapons and firearms on their person for purposes of mischief.”[53] One writer attempted to mock young men who used guns to punish young women who rejected their romantic overtures, suggesting that those who turned to violence were in fact cowards. In 1886, the Globe reprinted an article entitled “The Girl-Shooter” from the Albany Journal to this effect. The writer suggested the “modern style of juvenile fool” falls in love “or thinks he does.” The object of his love was

a sensible young lady. We know by the evidence, for she refuses to have anything to do with the callow youth. He feels aggrieved and robs his mother’s bureau drawer to get money to buy a pistol. He has read of some other fool who did the same, and so he takes the pistol and goes down to the house of the inamorata and asks her in a Hudson-avenue-tent-show voice if she will marry him. She remarks in a sensible manner that she is sorry, but Providence endowed her with taste and common sense to the extent which precludes her doing any such thing. Then the youth draws his pistol, shuts his eyes, and commences shooting. Usually he fills the maiden’s garments full of bullets and then attempts to blow out his own brains. Obviously he fails, as there are no brains to blow out. The bullet enters his head, rattles around for a time, and when they tip him over the bullet rolls out of his ear.[54]

Men who used revolvers to shoot the objects of their affection were thus portrayed as irrational boys incapable of controlling their emotions.

Special concern was expressed over the potentially deadly mixture of male bravado, guns, and alcohol. Time and time again, reports of gun violence involved drink, and critics of revolvers suggested that men, especially young men, emboldened by alcohol, were too quick to take offence, draw revolvers, and open fire. An incident in 1881 involving a drunken man wounding another led the Globe to suggest that the carrying of pistols was too common, and that it could be “taken for granted that no man ever draws a knife or a pistol on another unless” he was “in a passion or a state of intoxication.” Drunken men who carried revolvers were more likely to “commit crimes which are sure to cost them their liberty, if not their own lives.”[55] In 1883, the Globe again called attention to the danger of mixing guns and alcohol. “The ‘rough’ takes his glass, and while standing on the street corner gets into a squabble with a stranger returning from his work.” Then his “passion masters him before he is aware of it, and he shocks the community by laying dead at his feet the youth on whom helpless relatives are dependent for support.”[56] A few years later, reports that police officers had got drunk and fired off revolvers led the McLeod Gazette of Alberta to suggest that “this blazing away with a pistol whenever a man gets drunk, whether it be in the hands of a policeman or a citizen, is getting monotonous, and must be put down with a high hand.”[57] Middle-class demands for temperance in the nineteenth century represented an effort to create a “hegemonic way of viewing the world” that emphasized industriousness and respectable lifestyles.[58] When alcohol was mixed with guns, commentators realized that young men’s futures could be endangered, either by firing or receiving a fatal shot.

Canadians concerned about the use of revolvers also began to warn that Canada had to ensure that guns were treated differently in Canada than in the United States. Canadians believed Americans citizens were too prone to purchase and use revolvers. A few commentators suggested that Canada needed to better control pistols than the United States. A press account from 1866 indicated that differences had begun to emerge in attitudes to gun ownership and use in Canada and the United States. In an article entitled, “A Belligerent People,” the Halifax Citizen suggested that “Our American cousins are rapidly becoming a people of firearms,” and that revolvers “abound everywhere.”[59] Canadian newspapers frequently carried stories suggesting that Americans were prone to commit mass murder using revolvers, to participate in bizarre gun fights, and to allow children to use pistols with disastrous results.[60] These stories reinforced Canadians’ perception that they were a comparatively law-abiding and peaceful people, but also served to warn of the dangers of greater gun ownership and use. By the end of the 1870s, the view that Americans had become too fond of revolvers permeated political debates and the press in Canada. For example, in 1877 Senator Robert Barry Dickey of Nova Scotia claimed that young men in Canada had begun to carry and use pistols too freely, “a practice unfortunately too prevalent in the adjoining republic.”[61] Fear of allowing Canada to adopt a gun culture similar to the United States helped motivate Canadian legislators to adopt new control measures.

Canadian Pistol Laws, 1867–1892

The growing concern with revolvers led to calls for government regulation. Prime Minister Macdonald’s Conservatives, however, generally resisted efforts to regulate pistols, and the most important pieces of late-nineteenth-century legislation were only passed during the Liberal government of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie (1874–1878), and after Macdonald’s death in 1891. These measures were designed to prevent the carrying of concealed weapons, to prevent children from shooting themselves or others, and to ensure that records were kept of revolver sales. In general, these measures aimed to limit gun ownership by young men, especially urban, working-class men.

Prior to the late 1870s, the gun legislation of the federal government was extremely limited in its scope and application. Various cities banned the firing of guns within city limits to avoid accidents, discourage crime, or prevent the nuisance of noisy gunfire. But, municipal governments did not limit the possession of firearms.[62] The federal government typically placed limitations on gun possession and use only in places and at times that were deemed dangerous to the established order. For example, in 1869 Ottawa passed legislation that aimed to deal with labour violence at large public works projects. Modelled after similar legislation passed in the Province of Canada in 1845, the act could be proclaimed in effect in any place in Canada where a canal, railroad, or other public work was under construction.[63] Once the act was proclaimed, officials could prohibit the sale of liquor and dictate that no persons employed on the public work possess any firearm, air-gun, or a number of other kinds of weapons. Persons found carrying a banned weapon could be fined $2 to $4 for each weapon in their possession. Those who intentionally concealed arms potentially faced larger fines, ranging from $40 to $100.[64] The act proved a weak tool, however. In 1870, Ottawa amended the legislation so that it could be employed either to prohibit the sale of alcohol or weapons. While the government employed the ban on alcohol several times, the regulation against firearms was never proclaimed, perhaps because the legislation banned all employees from carrying weapons.[65] This meant disarming men working in rural areas against wild animals, and, perhaps more importantly, meant disarming management as well as labour.

An 1869 law that prevented individuals from carrying “offensive weapons” also illustrated the limitations of Canada’s early gun laws. This act stipulated a fine of between $10 and $40 for anyone who carried “about his person any Bowie-knife, Dagger or Dirk, or any weapons called or known as Iron Knuckles, Skull-crackers or Slung Shot, or other offensive weapons of a like character.”[66] To modern eyes, the provision against carrying “other offensive weapons” offered a useful tool to prevent the carrying of revolvers. However, the provision did not, in fact, include firearms, at least according to Prime Minister (and Minister of Justice) Macdonald, whose government passed the measure.[67] In the debate over the act in the House of Commons, Liberal Alexander Mackenzie suggested that pistols should be included explicitly in the list of weapons that could not be carried. According to Mackenzie, for every “one injury inflicted by knives, 20 or 30 had resulted from pistols.”[68] Macdonald rejected this proposal. Macdonald consistently opposed new gun laws during his time as prime minister, and in the debate over the 1869 legislation he offered one of his favourite arguments: the necessity of citizens to arm themselves because of the threat of American criminals crossing into Canada. No restriction should be placed on carrying firearms, said Macdonald, because Canada was neighboured by the United States, from which occasionally flowed “lawless characters in the habit of carrying weapons.” If it was “known that our people were prohibited by law from defending themselves, these parties might be encouraged to greater depredations,” suggested Macdonald.[69] Macdonald added other arguments against gun regulation in subsequent debates.

The perception that revolvers posed a growing danger subsequently led to more calls for the regulation of such weapons. The first call for more legislation appeared in the Globe in 1871, when the newspaper called pistols “an unmitigated evil” and said that every boy had “pistol fever.” For every pistol used as a means of defence, ten thousand were “made the instruments of death in the hands of careless or silly people.” The Globe thus claimed it would be better to outlaw revolvers, or, at the least, to appoint a board of examination that would examine and report upon the “amount of sense necessary to make a person a safe custodian of a loaded pistol.”[70] In Toronto in 1877, a magistrate said he was sorry that the law against carrying unlawful weapons did not extend to revolvers, for no one who carried a revolver had any use for it.[71] Prominent Conservative lawyer, politician, and judge Robert Harrison also became a strong advocate of regulating revolvers, at least the possession of pistols by the less respectable classes. Harrison himself had experience with such weapons, having armed himself with a revolver during the Fenian raids of 1866.[72] Harrison nevertheless suggested in 1872 that pistols were “too common in our country” and that revolvers were “much too indiscriminately used.”[73] He continued to voice this view after his elevation to the position of Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Queen’s Bench in 1875, telling a jury in 1876 that “it did not seem necessary that any citizen should” carry a revolver.[74] Harrison’s interest in controlling revolvers led him to introduce a bill in the House of Commons in 1872 that would have added pistols to the list of offensive weapons that the 1869 legislation had banned people from carrying.[75] Although Harrison was a Conservative and a good friend of Prime Minister Macdonald, his bill did not have the government’s support.

Despite powerful advocates of new laws, Ottawa was slow to pass more aggressive measures. Why? As already shown, Macdonald, and others, feared disarming Canadians in border areas within reach of American criminals. Another key rationale for opposition was the belief that new gun laws would infringe the constitutional right of British subjects to bear arms. The historic right to bear arms has been debated ad nauseam in the United States. Much of the American literature focuses on the history of the second amendment of the 1789 Bill of Rights, which provides that “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”[76] The debate in the United States over the right to bear arms has resulted in scholarly attention to the historic antecedents of the American provision, especially the right to bear arms found in the English Bill of Rights of 1689. Article VII of the Bill of Rights provides: “That the Subjects which are Protestants may have Armes for their defence suitable to their Condition and as allowed by Law.”[77] William Blackstone repeated, and disseminated, the right. He called Article VII an “auxiliary right”: “The fifth and last auxiliary right of the subject … is that of having arms for their defence, suitable to their condition and degree, and such as are allowed by law.”[78] Like the American second amendment, there has been debate about the meaning of Article VII. A minority of scholars, most prominently Joyce Lee Malcolm, has argued that this provision guaranteed a broad right to the mass of Englishmen to bear arms.[79] The majority position is that the guarantee was limited in several important ways. Lois Schwoerer has recently offered this view. She notes that only Protestants had a right to arms, which reflected the strong hostility to Catholics in English society. As well, the provision had a class limitation for men could only be armed “suitable to their Condition.” This, says Schwoerer, “reflected the social and economic prejudices of upper-class English society.”[80] After all, the upper classes did not want all Protestants to be armed. The possession of arms was to be associated with property ownership — men without property had little or no right to bear arms. Lastly, Schwoerer notes that the right to own guns was limited by the prior, present, and future laws, for the right was defined as “as allowed by Law.”[81]

Debates over gun regulation in Canada in the nineteenth century demonstrated that some Canadians held dear the right to bear arms, at least the right of men of property to bear arms as described by Schwoerer. The Glorious Revolution and the English Bill of Rights held a privileged place in the conception of British justice espoused by many nineteenth-century Canadian lawyers. As well, Blackstone was central in the education of nineteenth-century lawyers.[82] It is thus not surprising that parliamentary opponents of Harrison’s 1872 amendment criticized the measure using the language of the English Bill of Rights to emphasize the right of men of property to be armed. Liberal lawyer Edward Blake opposed Harrison’s measure on the ground that it “struck him that very dangerous consequences to the liberty of the subject might ensue from the proposal.”[83] Prime Minister Macdonald politely discussed his friend’s idea but ultimately rejected it. He ended his remarks on the bill by remembering “the principle laid down in Blackstone of the right of parties to carry weapons in self-defence.”[84] This belief in the English constitutional right to carry guns for self-defense is particularly important to understanding Macdonald’s reluctance to regulate gun ownership during his long tenure as prime minister.

The first substantial efforts to regulate revolvers had to wait until Macdonald’s Conservatives lost power to Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberals in the 1874 election. Concerns with the use of revolvers in episodes of collective violence contributed to the decision to pass legislation. Riots in Canada had decreased in frequency and intensity during the 1860s, but through the 1870s the number of violent riots increased in Canada. Militiamen were employed to suppress workers during the Grand Trunk Railway Strike of 1876–1877, and the Lachine Canal strikes of 1875 and 1877.[85] Many riots stemmed from sectarian tensions, and the stress caused by the economic downturn of the 1870s. For example, the battle over French-language schools in New Brunswick led to the Caraquet Riot of 1875, in which several participants fired revolvers.[86] Members of the Orange Order often came into conflict with French and Irish Catholics. Several riots sparked by public religious displays resulted in participants drawing and firing pistols. For example, Catholic processions in Toronto led to the so-called Jubilee riots of 1875 in which revolvers were fired. Revolvers also appeared in Montréal in 1875 when a Catholic mob stopped the internment of Joseph Guibord in a Catholic cemetery.[87] Such incidents, unsurprisingly, caused widespread alarm.

Mackenzie’s government passed two important pieces of gun regulation in 1877 and 1878. The initial push for a new gun law came from the senate, where Senator Robert Read introduced a measure to limit the use of revolvers in 1877. Like Harrison in 1872, Read proposed adding pistols to the 1869 legislation that prevented Canadians from carrying offensive weapons. A Conservative from Ontario appointed to the senate by Macdonald, Read had been a distiller, farmer, and tanner. He proposed legislation because of “the custom prevalent among the young men of the country of carrying concealed on their persons, pocket pistols, or revolvers.”[88] Read also told the senate of his concern that Canada needed new legislation to avoid the problems with guns that had emerged in the United States, where, he noted, 312 people had been killed by pistols in the previous year.[89]

Opponents of the measure in the senate offered a typical assortment of arguments, many of which sound familiar to modern ears. Richard William Scott, a Liberal, raised what would become a common concern with government gun regulation in the future: the problem of enforcement. In his view, the “main difficulty” of the bill was the “carrying of the law into execution.” Historians have correctly noted that that the mid to late nineteenth century was a period of substantial growth in state power.[90] However, Scott’s comments, and those of others, remind that many politicians remained acutely aware of Ottawa’s limited ability to enforce some criminal laws. Scott also expressed concern about passing a law that might affect law-abiding citizens more than criminals. He believed that burglars would still carry pistols, and thus the bill “would simply prevent honest people from carrying such weapons for self-defence.”[91] A concern with violating the rights of citizens again appeared. Senator George William Howlan of Prince Edward Island believed that the measure needed careful consideration because it would deprive citizens “of their rights as British subjects,” another reference to the English Bill of Rights.[92]

The senate bill was ultimately dropped when Liberal Edward Blake introduced legislation in the House of Commons that targeted the use of pistols. Blake was imbued by nineteenth-century liberal principles, and in 1872 he had opposed Harrison’s bill as an infringement of individual liberty.[93] The perceived crisis of murders, accidents, and suicides using revolvers, however, led him to change his mind. He told the House of Commons that “there could be no doubt that the practice of carrying fire-arms was becoming too common.” Like others, he emphasized the dangers of armed working-class youth, suggesting that revolvers were typically carried by “the rowdy and reckless characters, and boys and young men.” Blake’s comments suggested the extent to which Canadians had become concerned with the mixture of guns and male youth culture. For reckless youth, the “revolver was almost part of their ordinary equipage.” Blake did not advocate banning revolvers, however. Instead, he crafted a law that reserved the use of revolvers to respectable individuals. Blake was apprehensive that if parliament passed a law prohibiting every person from carrying revolvers then “reckless characters, who intended violence, would not care about the law, and would carry small concealed weapons; while the sober, law-abiding citizen would be unprotected.”[94] John A. Maconald, now the leader of the opposition Conservatives, continued to oppose gun legislation, although even he agreed with a proposed provision against pointing unloaded guns at people, for he thought it was “grievous to read in the newspapers of persons carelessly, mischievously, and wantonly pointing firearms without knowing whether they were loaded or not, and destroying valuable lives.”[95]

The act passed by the Liberals in 1877, An Act to make provision against the improper use of Firearms, represented the first substantial effort by the dominion to regulate revolvers. It largely banned the practice of carrying pistols.[96] A person carrying a pistol or airgun without reasonable cause of fear of assault or injury to himself, his family, or his property could be required to find sureties for keeping the peace for a term of up to six months. If in default of finding such sureties, the person could be imprisoned for a term of up to 30 days. The act also provided that anyone arrested either on a warrant or while committing an offence who was in possession of a pistol or airgun was liable to a fine of between $20 and $50, or to imprisonment for up to three months.[97] Another provision dictated that a person who carried a pistol or airgun with the intent to do injury to another person was liable to a fine of $50 to $200, or prison term of up to six months. Intent could be inferred from the fact that the pistol or airgun was on the person. These provisions clearly aimed at the criminal use of revolvers. The act also attempted to prevent accidents by dictating a fine of between $20 and $50 (or up to 30 days in jail) for anyone who pointed any firearm or airgun, whether loaded or unloaded, without a lawful excuse. Parliament made sure to note that sailors, soldiers, volunteers, and police were not affected by the act when they carried loaded pistols while working.

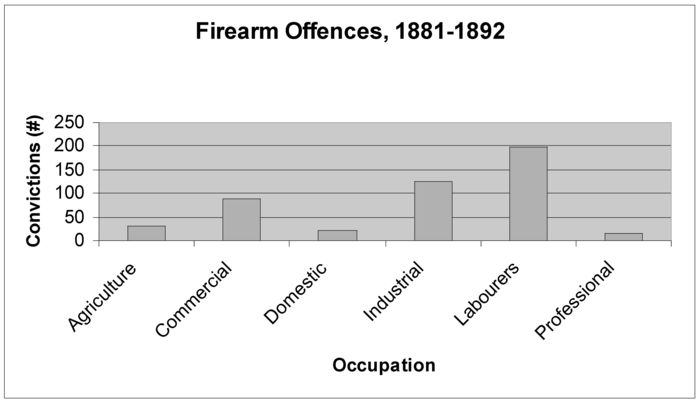

Dominion statistics provide a window into the extent to which the law against carrying unlawful weapons was used, where it was employed, and who was targeted.[98] Between 1881 and 1892, there were 1,466 convictions for weapons offences. This substantial figure suggests that the statements by journalists, politicians, and legal professionals about a growing number of young men carrying weapons may have been grounded in some truth. Geographically, Ontario saw by the far the most convictions. Just over 65 percent of all convictions occurred in Ontario, followed by Québec (20.8 percent), Manitoba (5.46 percent), British Columbia (2.80 percent), New Brunswick (2.73 percent), Nova Scotia (1.98 percent), the territories (0.75 percent), and Prince Edward Island (0.34 percent). The majority of convictions in Ontario demonstrate that either the carrying of weapons was a greater problem in that province, or there was more public concern and thus a greater emphasis on charging those found with weapons. Regardless of which explanation is correct, the high proportion of convictions from Ontario helps explain the frequent calls for legislative action from that province.

The national crime statistics provided detailed information on many of those convicted in the 1881 to 1892 period. These statistics are incomplete, however, because beginning in 1884 detailed information was only tabulated for those convicted of indictable firearms offences. Nevertheless, information can be gleaned for a substantial segment of those convicted. The vast majority resided in urban areas.[99] Of the 498 persons whose residences were listed, 78.5 percent were from urban areas during the 1881 to 1892 period. The law was also frequently enforced against working-class men. The dominion reported the employment of 478 of those convicted for the indictable offence of carrying unlawful weapons. Seventy-two percent were industrial workers, labourers, or domestics. (see Graph 1)

Graph 1

Employment of those convicted of carrying unlawful weapons, 1881-92[100]

The 1877 legislation did not solve the pistol problem in Canada because the act had several weaknesses. The penalties for those found carrying a revolver were too light. As well, the 1877 legislation did not allow suspicious persons to be searched for weapons.[101] These weaknesses were especially glaring at times of collective violence. Legislators dealt with social upheaval with new measures to secure firearms. Ontario responded to the resistance of workers with a new version of an expired 1845 Province of Canada law that allowed for the prohibition of weapons on public works.[102]

Riots in Montréal in 1877, and concerns about more Montréal unrest in 1878, led Prime Minister Mackenzie to place new restrictions on firearms in 1878. The conflict in 1877 began when the Orange Order of Montréal intended to march on 12 July 1877, to commemorate the 1690 Battle of the Boyne. High tensions led the Orange Order to cancel the procession, but 12 July did not pass peacefully. On 11 July, a 16-year old militiaman killed a Catholic labourer with a bayonet. The next day, Catholics attacked Protestants as they left church. Brawls broke out throughout the city, revolvers were brandished, and one young Orangeman, Thomas Hackett, was shot and killed during a melee. Over the next few days, a number of rioters fired revolvers in different parts of the city.[103]

Officials employed the 1877 act against carrying and using revolvers to try to quell the violence in Montréal. For example, the city recorder prosecuted John Sheehan, who was later charged for the murder of Hackett, for pointing a revolver at William Charles Patton. Later in July, the recorder convicted two other men of carrying revolvers. Despite occasional prosecutions, the weaknesses of the legislation were apparent. For example, the day of Hackett’s funeral was marked by more sectarian violence, with several men pulling revolvers and opening fire.[104] The Montréal Daily Witness called the 1877 legislation a “dead letter.”[105] In 1878, many began expressing concerns that violence would repeat itself because of the 1877 legislation’s limitations. Fears were realized in April 1878 when roughly 100 men gathered near Wellington Bridge in Montréal, and one Catholic, John Colligan, was killed and others were injured in gunfights.[106]

The violence in Montréal led to calls for stronger measures to stop gun play. “Prudence” wrote to the Montreal Gazette to complain about the “murderous attacks with pistols” which “for some time back have been of such frequent occurrence in the streets of Montréal and elsewhere in Canada.” Prudence’s solution was to stop the flow of revolvers into Canada.[107] Members of the Catholic clergy of Montréal asked for better gun laws, noting that so long as “bands of people, especially young men, can parade the streets by day and by night, having deadly weapons concealed on their persons and hatred in their hearts, there can be no security for the peace of the city, nor even for human life.”[108]

In response to this urban violence, Edward Blake drafted a bill that combined provisions of the 1869 legislation against guns in areas of public works with an imperial statute designed to prevent the possession of arms in Ireland.[109] The new act allowed cabinet to proclaim the statute operative in a district or districts as needed. Once proclaimed, the only people who could freely carry weapons were justices of the peace, members of the military while on duty, police officers, or a person licensed under the act. People were allowed, however, to keep guns in their own home, shop, warehouse, or counting-house, thus reflecting the common view that men of means could keep and use arms to protect their property. Anyone who violated the ban was subject to a prison term of up to 12 months. Unlike the legislation against carrying pistols passed in 1877, the new legislation allowed for the search of persons suspected of carrying weapons. Justices of the peace could also issue search warrants for homes or businesses if it was believed that guns were kept for the purpose of being carried in a proclaimed district.[110]

The parliamentary debates over the 1878 act again reflected a number of common attitudes, including the perception that revolvers were becoming a social problem, the perceived inability of the state to enforce strict gun controls, and continued doubts about whether the state had a right to disarm citizens. Blake argued for the legislation because of the increase in violent crimes. Montréal played a large role in Blake’s thinking. He noted that for nearly a year “the city had been the scene of frequent violent attacks in the streets by different parties, in which firearms had been used with the utmost recklessness.”[111] In his view, the existing laws against carrying weapons did not have sufficient penalties. Also, the 1877 legislation did not allow police to search people for concealed weapons, and thus the “lawless character might without apprehension carry his revolver,” for he could “fairly presume that the law-abiding citizen, knowing it was a crime to carry a weapon, would not carry one, so that immunity and license to the lawless individual might result.”[112] Practical and ideological concerns once again shaped the legislation. Blake, for instance, was aware that enforcing more stringent regulations on firearms would prove difficult. He also warned that it was important not to interfere too strongly in the rights of subjects. He thus decided against including provisions in the bill that would have banned weapons in homes because such a measure “involved the exercise of the arbitrary right of searching, which was very liable to be abused,” and would have “infringed to a certain extent upon the well-worn opinion that a man’s house is his castle.”[113] Blake would later state that the act was needed even though “under ordinary circumstances,” it “would deserve the term odious legislation.”[114] This again reflected Blake’s belief that men of property possessed a right to possess arms in normal circumstances.

Prime Minister Mackenzie threw his support behind the measure, though he and others also expressed reservations about disarming citizens in proclaimed districts and the ability of authorities to implement the act successfully. He acknowledged the challenges of enforcement, saying that the act “would require a strong force” and “would be very imperfectly executed.”[115] Mackenzie, however, believed that the bill was needed because many poor working men were prone to reaching for a gun to settle disputes. The Speaker of the House of Commons, Timothy Warren Anglin of New Brunswick, also worried that allowing people to keep guns in their homes would make the new law ineffectual. His solution would have been a stronger bill that would have disarmed the whole population, except for “persons of known respectability” who could receive licenses to have arms in their homes.[116] Québec MP and lawyer Hector-Louis Langevin, like Blake, said that the act, when proclaimed, would “interfere with our rights and privileges.”[117] The reluctance to pass an onerous piece of legislation meant that the act had to be temporary. It was to be in effect until the end of the next session of parliament.[118] The act was renewed several times, however, and remained on the statute book until 1884.[119] The act was proclaimed in Montréal and the County of Hochelaga for six years, in Québec City in 1879, and in Winnipeg in 1882.[120]

The legislation of 1877 and 1878 did not end calls for more regulation. A Winnipeg grand jury pleaded in late 1878 that authorities had to “carry out with the utmost severity the law with respect to the carrying of firearms,” for Winnipeg’s citizens had a “floating population continually surrounding us,” and thus “some action should be taken to limit this dangerous habit.”[121] In 1883, Kingston, Ontario, passed a by-law banning the discharge of firearms in the city because the “practice of firing off pistols, revolvers and other firearms in the City” was “becoming too prevalent for the safety of the inhabitants.”[122] As of 1880, Canadian law still allowed any person to buy a revolver, did not regulate who could sell them, and did not require retailers to keep records of gun sales. As a result, gun violence continued in Canada. The calls for strengthening gun laws came from various sources. A hardware merchant from Guelph suggested in 1882 that “the law as to carrying revolvers seems to be defective.” He recommended that purchasers be required to get permission from two magistrates, for, although he himself profited from gun sales, “the sale now is going on at an alarming and to a dangerous extent.”[123] The Toronto Globe pressed hard for more aggressive laws. The Globe’s view became entrenched when the newspapers’ iconic founder, George Brown, was shot in 1880. The shooter, George Bennett, was a former Globe employee who had been fired for intemperance. Bennett entered Brown’s office to request a certificate stating that he had worked at the Globe. An argument ensued and Bennett pulled a revolver and fired. A bullet struck Brown in the leg. At first the injury was considered slight, and Brown went home. The wound, however, became infected, and Brown developed a fever, became delirious, and died at the age of 61.[124]

Brown’s death led the Globe to launch a fierce attack on revolvers. It declared that the revolver “ready to the hand of an angry man, has made many a murderer where if no weapons had been near no conflict whatever would have taken place.” Men had been “shot in quarrels which, a few hours afterward, appeared contemptible in the eyes of the conscience-stricken criminals.”[125] It kept up its criticism into the late 1880s.[126] The Globe was not alone in recognizing the continued problem. The McLeod Gazette, for example, declared in 1888 that accidents meant that “police authorities wish it understood that they are determined to put a stop to the reckless handling of fire-arms”;[127] and The Canada Presbyterian asked in 1892: “Why is this law against carrying revolvers not enforced in Ontario?”[128]

Shooting of George Brown, Canadian Illustrated News[129]

Senators tried to tackle the issue in the late 1880s. The leading advocate of this legislation continued to be Senator Robert Read. He introduced a bill in 1889 because “the practice of carrying dangerous weapons is on the increase,” such that one could “scarcely take up a paper” in which there were not “reports of loss of life from the use of the ‘ready revolver’.” Like others, he noted the propensity for men and boys to carry revolver: “I notice that even boys carry them; and young men carry them to their daily labor.” His measure, though, was not radical. He proposed that persons who carried offensive weapons would be fined, rather than be forced to give a surety. Read hoped that this would change peoples’ perception of the propriety of carrying weapons.[130] Several other senators also argued for the necessity of new legislation.[131] A bill passed in the senate but died in the House of Commons. The senate passed a similar measure in 1890, but the commons again refused to pass it, and Read was left to lament that his bills were “slaughtered with the innocents in the Commons.”[132]

The failure of Read’s bills once again stemmed largely from the opposition of John A. Macdonald, who had become prime minister for the second time in October 1878. New gun laws had to wait until Macdonald’s death in June 1891.[133] In 1892, Attorney General John S.D. Thompson shepherded the first Criminal Code through parliament. The Code included important new rules concerning the use of guns, especially pistols. There was little debate in parliament about the new provisions, probably because the sense of urgency about the problem of revolvers had continued to grow. Thompson said that Criminal Code sections dealing with guns established severe penalties because it was “the only way to prevent the carrying of weapons for offensive purposes.”[134] The Code retained the law making it an indictable offence to carry an offensive weapon for a purpose dangerous to the public peace, for which it dictated a punishment of up to five years, as well as the ban against pointing a firearm at another person.[135] It also included a provision that made it a summary offence to possess any firearm or airgun if disguised.[136] It incorporated four other important new provisions. First, it raised the penalties for the offence of carrying a pistol or airgun without justification (although Canadians could still keep such a weapon in their home or business) to a fine of between $5 and $25 and up to one month in jail. Second, the Code also created a new system for identifying who could carry a revolver. Canadians at least 16 years old could obtain a “certificate of exemption” valid for 12 months if they could convince a justice of the peace of the applicant’s discretion and a good character. Justices had to record such certificates and make a return of any such certificates issued.[137] Certificates of exemption to carry revolvers outside of one’s home or business marked a substantial increase in the state’s supervision of the use of revolvers, but also reflected the continued belief that respectable men of good character could arm themselves.

The third major innovation in the Criminal Code was a prohibition on the selling or gifting of pistols or airguns to anyone under the age of 16.[138] This was the first time that Canada placed an age restriction on who could purchase guns (note, though, it did not ban the ownership of guns by boys under 16).[139] The legislation was clearly aimed at preventing the use of pistols by reckless boys and young men. The fourth innovation was a requirement that any person selling a pistol or airgun had to keep a record, including the date of the sale, the name of the purchaser, and the maker’s name or other mark by which the gun could be identified.[140] This was the first time gun sellers had been forced to keep track of gun sales.

In passing these measures, Canada took a more proactive approach to gun regulation than Britain at the time. Britain also considered increased gun regulation because of the perceived problem of revolvers. In 1870, the Gun Licenses Act imposed a fee on anyone who carried or used weapons outside of their dwelling house. The measure, however, was designed to increase government revenue more than place a serious restriction on the carrying or use of arms. Liberal governments introduced several bills in 1890s designed to stop gun violence. For example, Prime Minister William Gladstone’s government introduced a bill in 1893 that would have restricted the ownership of pistols less than 15 inches long, have required pistol owners to be over 18 years old, and have identified legitimate retailers as those possessing a license. The bill did not pass, nor did another introduced in 1895 that would have required identification marks be added to pistols, increased the license fee for selling pistols to dissuade retailers from carrying cheap revolvers, and required pistol owners to get a license to be renewed annually. Not until the early twentieth century did Britain create important limitations on the ability of its citizens to keep arms.[141]

Conclusion

It is extremely difficult to determine the actual extent of the pistol problem in late nineteenth-century Canada. With limited statistical evidence available regarding the number of handguns in the country, historians are unfortunately left to rely on the comments of politicians, journalists, and legal professionals, prosecution statistics, and evidence of gun imports. All are imperfect sources. Together, however, they suggest that Canadians in the 1870s and 1880s, especially those living in major urban centres, had to deal with for the first time the introduction of substantial numbers of cheap, mass-produced, and concealable pistols.

The legislation passed in the late 1870s and in 1892 represented the beginning of permanent government regulation of handguns in Canada. While the early legislation may seem modest today, it was important because it began to differentiate the gun cultures and firearm laws of Canada and the United States. While the United States has approximately ten times the population of Canada, it has over 60 times as many handguns.[142] The early legislative initiatives discussed here became the cornerstone of later legislation that, over time, may have resulted in substantially lower levels of pistol ownership in Canada and also, perhaps, different attitudes to handguns in the two nations.

The guns laws enacted in the late nineteenth century, however, should also give pause to progressive Canadians who sometimes make gun regulation a pillar of Canadian nationalism. For many progressive Canadians, gun regulation has become a means of distinguishing Canada from the United States. But, as has been shown here, gun control measures were often shaped by less than noble impulses. Pistol laws were designed to discourage young men, especially young working-class men, from carrying revolvers. Canadian politicians suggested that such men posed a serious threat to Canadian order, especially during periods of ethnic, religious, and class conflict. In times of tumult, the carrying of arms by working men had to be stopped. Calls for stronger gun laws were rejected because such measures struck many parliamentarians as impractical, unconstitutional, or both. A common belief was that men of property had a right to be armed. Legislation always provided provisions to allow this, such as the exemptions permitting guns to be kept in homes or in places of business, which it was thought, ensured that respectable citizens could defend their lives and property against the reckless. The concern that the state lacked the ability to enforce its will on Canadians also led to the decision not to pass more stringent gun laws. Revolvers were easily hidden on the person and no legislator felt it possible (even if desirable) to ban the revolver. The debates over gun laws thus demonstrate awareness by late-nineteenth-century politicians of the limits of state power.

Parties annexes

Remerciements

The research for this article has been made possible with funding provided by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council, the Canada-US Fulbright Commission, and Saint Mary’s University.

Biographical Note / Note biographique

Blake Brown is an Assistant Professor of History at Saint Mary’s University, and the author of A Trying Question: The Jury in Nineteenth-Century Canada (University of Toronto Press and the Osgoode Society, 2009). His current book project is a history of gun culture and firearm regulation in Canada.

Blake Brown est professeur adjoint d’histoire à l’Université Saint Mary’s et l’auteur de A Trying Question: The Jury in Nineteenth-Century Canada (Presses de l’Université de Toronto et Osgoode Society, 2009). Il travaille actuellement à un nouveau livre sur l’histoire de la culture des armes à feu et de la réglementation des armes à feu au Canada.

Notes

-

[1]

The terms commonly used to describe handguns changed over time. A “revolver” was a weapon with a rotating cylinder that could carry several rounds of ammunition. A “pistol” was an older term sometimes used only to describe muzzle-loaded weapons. At times, Canadians used “pistols” to refer to all types of handguns. Unless otherwise indicated, this paper employs the term pistol in the broader sense.

-

[2]

Gérald Pelletier, “Le Code criminal canadien, 1892–1939: Le contrôl des armes à feu,” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés 6, no. 2 (2002): 51–79.

-

[3]

Philip C. Stenning, “Guns and the Law,” The Beaver 80, no. 6 (2000–2001): 6.

-

[4]

Samuel A. Bottomley, “Parliament, Politics and Policy: Gun Control in Canada, 1867–2003,” (Ph.D. diss., Carleton University, 2004). Bottomley’s work is unpublished except for an article on modern debates over gun control. Samuel A. Bottomley, “Locked and Loaded: Gun Control Policy in Canada,” in The Real Worlds of Canadian Politics: Cases on Process and Policy, eds. Robert M. Campbell, Leslie A. Pal, and Michael Howlett, 4th ed. (Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 2004), 19–79.

-

[5]

Susan Binnie, “Maintaining Order on the Pacific Railway: The Peace Preservation Act, 1869–85,” in Canadian State Trials, Volume III: Political Trials and Security Measures, 1840–1914, eds. Barry Wright and Susan Binnie (Toronto: University of Toronto Press and the Osgoode Society, 2009), 204–56; Susan Binnie, “The Blake Act of 1878: A Legislative Solution to Urban Violence in Post-Confederation Canada,” in Law, Society, and the State: Essays in Modern Legal History, eds. Louis A. Knafla and Susan Binnie (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), 233.

-

[6]

Binnie, “The Blake Act of 1878,” 233.

-

[7]

An incident in 1846 in Richmond Hill, Upper Canada, illustrated this weakness. An attempted suicide with a pistol was botched because the bullets meant to pierce the shooter’s brain slipped out of the gun. “Attempted suicide at Richmond Hill,” Globe (26 December 1846), 3.

-

[8]

W.Y. Carman, A History of Firearms from the Earliest Times to 1914 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1955), 131–43. On the weaknesses of early firearms, see Kenneth Chase, Firearms: A Global History to 1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 23–6.

-

[9]

David A. Hounshell, From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 46–50; R.L. Wilson, Colt, An American Legend: The Official History of Colt Firearms from 1836 to the Present (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985); Ellsworth S. Grant, The Colt Legacy: The Colt Armory in Hartford, 1855–1980 (Providence, RI: Mowbray, 1982).

-

[10]

Carman, A History of Firearms, 145–6.

-

[11]

For example, see “J. Grainger, Gun and Pistol Maker,” Globe (5 November 1857), 3; “Revolvers,” Halifax British Colonist (16 October 1858).

-

[12]

Globe (31 January 1859), 4.

-

[13]

“To Sportsmen,” Quebec Mercury (10 June 1863), 1.

-

[14]

Ottawa Times (4 August 1866), 3. In 1855, participants in a Hamilton post office robbery had bought three pistols for the substantial sums of $9.00, $10.00, and $35.00. “Police Intelligence,” Globe (27 January 1855), 3. Leading Upper Canada lawyer Robert Harrison reported buying a revolver for $10.00 in 1866 in Toronto. Peter Oliver, The Conventional Man: The Diaries of Ontario Chief Justice Robert A. Harrison, 1856–1878 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press and the Osgoode Society, 2003), 275.

-

[15]

Lee Kennett and James La Verne Anderson, The Gun in America: The Origins of a National Dilemma (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975), 156.

-

[16]

Winnipeg Daily Sun (16 April 1883), 6; [Winnipeg] Morning Telegram (26 July 1900), 2.

-

[17]

Globe (26 August 1882), 5. Also see “Stark’s Guns,” Globe (27 October 1894), 18; “McCready’s Clearing Out Sale,” Globe (18 June 1896), 10. Reports of the low price of weapons also frequently appeared in murder trial reports. For instance, a murderer in Shelburne, Ontario, in 1882 reportedly bought his revolver for $2.50. “Shelburne Murder,” Globe (25 January 1882), 3.

-

[18]

Patrick Brode, Death in the Queen City: Clara Ford on Trial, 1895 (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2005), 113.

-

[19]

Joyce Lee Malcolm, Guns and Violence: The English Experience (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 132. The challenge of quantifying gun ownership played a large role in the debates spurred by Michael A. Bellesiles’ award-winning book, Arming America, which was subsequently discredited for its factual errors. Michael A. Bellesiles, Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000). For discussions regarding how historians should estimate firearm ownership, see Randolph Roth, “Counting Guns: What Social Science Historians Know and Could Learn About Gun Ownership, Gun Culture, and Gun Violence in the United States,” Social Science History 26, no. 4 (2002): 699–708. Douglas McCalla has employed county store records to gauge gun ownership in pre-Confederation Upper Canada. Douglas McCalla, “Upper Canadians and Their Guns: An Exploration via Country Store Accounts,” Ontario History 47, no. 2 (2005): 121–37.

-

[20]

“Tables of the Trade and Navigation of the Dominion of Canada,” Sessional Papers, 1870–1883. Dominion statistics only once provided an estimate of the number of guns imported. In 1877, Ottawa reported Canada imported 11,897 guns valued at $79,827.

-

[21]

“E. Remington & Sons,” Grand River Sachem (15 August 1866), 3.

-

[22]

Globe (4 November 1895), 6.

-

[23]

S. James Gooding, The Canadian Gunsmiths, 1608–1900 (West Hill, Ont.: Museum Restoration Service, 1962), 154.

-

[24]

Debates, Senate, 1 March 1877, 120.

-

[25]

For examples, see “Serious Accident,” Halifax British Colonist (22 September 1849), 2; “Melancholy Accident,” British Colonist (25 October 1849), 2; “Frightful Accident,” Halifax Citizen (21 September 1865), 2; Halifax Citizen (28 November 1865), 2; “Fatal Accident,” Halifax Citizen (3 July 1869), 2; “Fatal Accident,” Halifax Citizen (5 October 1869), 2.

-

[26]

On the growth of rifle shooting in Canada, see K.B. Wamsley, “Cultural Signification and National Ideologies: Rifle-Shooting in Late Nineteenth-Century Canada,” Social History 20, no. 1 (1995): 63–72.

-

[27]

“Reckless Use of Firearms,” Globe (28 August 1888), 8.

-

[28]

“A Fatal Shot,” Globe (20 January 1882), 3.

-

[29]

“Shot Through the Heart,” Globe (8 April 1881), 6.

-

[30]

Globe (8 February 1887), 6.

-

[31]

“The Gun was Loaded,” Globe (16 July 1891), 10.

-

[32]

Globe (5 April 1879), 8.

-

[33]

“Accidentally Shot,” Globe (2 April, 1887), 16.

-

[34]

Debates, Senate, 1 March 1877, 117. For this practice in the United States, see Kennett and Anderson, The Gun in America, 156–7. The various ways in which revolvers were concealed is discussed in “The Pistol Pocket,” Woodstock Sentinel-Review (18 July 1889), 3.

-

[35]

“Revolvers and Whisky,” Toronto World (20 February 1883), 1.

-

[36]

“Seduction and Murder,” Globe (25 July 1868), 1. Also see Globe (8 October 1875), 2; “A Family Slaughtered,” Globe (18 November 1886), 1.

-

[37]

Senate, Debates, 2 April 1889, 377.

-

[38]

For example, after three men used a revolver to commit a highway robbery in 1885, the Globe suggested that such robberies were “becoming so common these days that it is hardly safe for a citizen to venture out on a dark street after nightfall.” “State of the Streets,” Globe (3 November 1885), 2. Also common were reports of burglars drawing weapons when discovered. For example, in 1886, when Thomas Adams of Toronto heard a noise in the middle of the night, he picked up a stick and headed downstairs. Halfway down he saw a burglar, who responded by opening fire with a revolver. A bullet grazed Adams’ head, and the burglar escaped. “Very Nearly a Murder,” Globe (2 November 1886), 8. Also see Manitoba Daily Free Press (16 July 1879), 1; “A Plucky Fight with Burglars,” Globe (6 May 1887), 1; “Two Shots Fired,” Globe (1 December 1887), 8; Globe (28 December 1887), 3; “Douglas Also Confesses,” Globe (1 January 1892), 1–2; “Brandon Burglary,” Manitoba Morning Free Press (18 September 1894), 1.

-

[39]

“From Pictou,” Halifax Citizen (1 February 1870), 2; “Melancholy Suicide,” Halifax Citizen (8 August 1870), 3; “Determined Suicide,” Globe (10 January 1882), 8; “Canada,” Globe (17 June 1882), 3; “Belleville,” Globe (17 April 1883), 2; “Manitoba,” Globe (30 August 1882), 3; “Suicide at Golden,” Manitoba Daily Free Press (11 July 1887), 4; “Attempted Suicide,” Globe (31 January 1888), 1; Globe (20 January 1888), 1; “A Deliberate Suicide,” Globe (25 February 1888), 16; “Tired of Life,” Globe (12 May 1888), 16; “Suicide,” Globe (11 August 1888), 1; “The Suicide of Harris,” Manitoba Daily Free Press (7 November 1891), 1; “A High Park Horror,” Globe (25 January 1892), 8; “Shooting Fatality,” Globe (4 January 1893), 4. Risa Barkin and Ian Gentles suggest a perhaps not coincidental rise in suicides in Toronto after 1868. Risa Barkin and Ian Gentles, “Death in Victorian Toronto, 1850–1899,” Urban History Review 19, no.1 (1990): 15–6.

-

[40]

For examples of early incidents of criminals using revolvers, see “Burglar Caught,” Globe (3 October 1857), 2; Globe (13 October 1857), 2; “Toronto Spring Assizes,” Globe (17 April 1858), 3.

-

[41]

For a recent discussion of the McGee murder, see David A. Wilson, “The D’Arcy McGee Affair and the Suspension of Habeas Corpus,” in Canadian State Trials, Volume III, eds. Wright and Binnie, 85–120.

-

[42]

“Terrible Results of Carelessness with Firearms,” Globe (7 August 1882), 3.

-

[43]

“Humorous,” Globe (27 November 1880), 11.

-

[44]

Debates, Senate, 1 March 1877, 120. Flint said that he sometimes carried a revolver, but he did it openly, often leaving it on the seat of his carriage.

-

[45]

Ibid.

-

[46]

Ibid., 121.

-

[47]

Ibid., 120. Also see the comments by William Miller of Nova Scotia. Ibid., 121.

-

[48]

Winnipeg Daily Free Press (18 April 1876), 3. Also see “City Police Court,” [Winnipeg] Daily Free Press (21 July 1874), 2.

-

[49]

Report of the Commissioner of the North-West Mounted Police Force, 1885 (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1886), 119; Report of the Commissioner of the North-West Mounted Police Force, 1886 (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1887), 130; “A Future Metropolis,” Globe (16 June 1888), 6.

-

[50]

Lloyd’s (10 May 1868), 6, quoted in Cops and Bobbies: Police Authority in New York and London, 1830–1870, Wilbur R. Miller (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), 115.

-

[51]

Kennett and Anderson, The Gun in America, 120.

-

[52]

Globe (25 March 1885), 3.

-

[53]

“The Criminal Law,” Manitoba Daily Free Press (17 May 1877), 2.

-

[54]

“The Girl-Shooter,” Globe (17 July 1886), 13.

-

[55]

“The Knife and the Pistol,” Globe (26 September 1881), 4.

-

[56]

“The York-Street Murder,” Globe (9 August 1883), 4.

-

[57]

“A Bit Drunk,” McLeod Gazette (16 February 1886). For other examples of incidents involving guns and alcohol, see “Disturbance at Waverley,” Halifax Citizen (25 October 1864); “Latest from Halifax,” Globe (27 December 1871), 1; Manitoba Daily Free Press (27 September 1880), 1; Globe (29 September 1881), 2; “Killed in his Tracks,” Manitoba Daily Free Press (26 October 1882), 8; “Revolvers and Whisky,” Toronto World (20 February 1883), 1; “Penalty for Carrying Firearms,” Globe (24 February 1883), 14; “Murder at Brampton,” Globe (23 April 1892), 13; “A Sensation in London,” Globe (14 October 1892), 1.

-

[58]

Craig Heron, Booze: A Distilled History (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2003), 60.

-

[59]

“A Belligerent People,” Halifax Citizen (4 August 1866), 1.

-

[60]

For examples, see “A Utah Horror,” [Winnipeg] Daily Free Press (21 April 1875), 2; [Winnipeg] Daily Free Press (26 November 1875), 2; “A Deadly Point of Pronunciation,” Manitoba Daily Free Press (2 May 1879), 2; “Laying Down Their Arms,” Manitoba Free Press (16 August 1879), 3.

-

[61]

Debates, Senate, 1 March 1877, 120. Also see “Notes and Comments,” Globe (19 August 1878), 2.

-

[62]