Résumés

Abstract

In this essay we examine media coverage in 2020 and 2021 of the COVID-19-related practice of “working from bed.” Although presented as a new phenomenon, working from bed has a long history. We suggest that the late modern bourgeois understanding of the bedroom as a private space has long been manipulated by artists, writers, and other celebrities, both through staged photos and more self-conscious representation. These representations play on the paradox of a public figure making their intimate self visible and invite an audience without losing control of the scene. By contrast, media representation of (and advice about) working from bed for white-collar professionals is fraught with anxiety about how to create an image of a desexualized, generic worker whose bed, bedroom, and self-in-bed are newly available to clients, co-workers, and bosses. Presenting distinctive challenges for women workers, the advice we surveyed focuses on aesthetics and comportment, using “professionalism” as a code for discipline and trivializing the consequences of home surveillance.

Résumé

Dans cet essai, nous examinons la couverture médiatique qui a eu lieu en 2020 et 2021 concernant la pratique du « travail au lit » liée aux directives de la COVID-19. Bien que présenté comme un phénomène nouveau, le travail au lit a une longue histoire. Nous suggérons que la conception bourgeoise tardive de la chambre à coucher en tant qu’espace privé a longtemps été manipulée par des artistes, des écrivains et d’autres célébrités, à la fois par des photos mises en scène et par une représentation plus consciente d’elle-même. Ces représentations jouent sur le paradoxe d’une intimité mise à nue par une personnalité publique contrôlant l’image de cette intimité représentée. En revanche, la représentation médiatique du travail au lit (et les conseils à ce sujet) pour les professionnels en col blanc sont empreints d’anxiété quant à la manière de créer l’image d’un travailleur générique et désexualisé dont le lit, la chambre à coucher et le soi au lit sont nouvellement disponibles pour les clients, les collègues et les patrons. Les conseils que nous avons recueillis se concentrent sur l’esthétique et le comportement, utilisant le « professionnalisme » comme un code de discipline et banalisant les conséquences de la surveillance à domicile, ce qui représente un défi particulier pour les travailleuses.

Corps de l’article

In 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, about 41 percent of employees in the UK, 37 percent in the US, and 28 percent in Canada abruptly shifted from working primarily at a site outside their place of residence—such as a government office, a university or school, a financial institution, or a tech company—to teleworking or working from home (WFH). This “pivot” was possible, of course, because of existing digital technologies that enable workers to message, exchange and edit documents and images, and, most of all, hold meetings through a screen. Unsurprisingly, the people who pivoted were more highly-educated, white-collar employees, most of them working in financial services and insurance, education, or professional/technical services.[1] The video teleconference became, overnight, a daily part of many more people’s work routines and was conducted from domestic spaces that might previously have been understood as “private” or “personal”—places where work would not normally occur, or that coworkers would never see. Advice columns sprang up on how to curate one’s Zoom background for maximum professional impact, when it’s okay to switch off your camera (or insist that someone else put theirs on), what to wear (above the waist), or how to choreograph one’s family members, pets, or other unpredictable cohabitants who might suddenly appear or be overheard. One of the most contentious aspects of this debate, laden with class distinctions, focuses on the bedroom—for a certain constituency, the most plausibly “private” room in the home from which work could reasonably be conducted. Those in larger homes already had (or could assign) a separate study or office room with a secure door to provide a quiet and private workspace, while those who lived in more crowded or smaller homes without any clearly demarcated “room of their own” (including a bedroom) might just have to work from the kitchen table or the couch. For a significant number of middle-class employees, however, the bedroom is the less-than-ideal but, nonetheless, most apt space to set up a work-from-home office.

For most of the history of beds and sleep spaces, and in many places still, both have been shared and far from private, yet in the twenty-first century in the global north, the bourgeois bedroom occupies a distinctive position—in mainstream domestic architecture and in the cultural imagination.[2] Within these limited material contexts and social norms, the bedroom is often considered a sanctum—the place to which children and youth retreat (or are sent to reflect);[3] where adults go to find peace and quiet, to rage, perhaps to cry; where we dress ourselves, or put on makeup, or do our hair, or otherwise create an aesthetic presentation for the outside world; in which we have sex; or where we sleep. And within the bedroom, typically the most space-consuming, visible, and well-used object is the bed itself. If you are going to work from your bedroom, chances are you are sitting or lying on your bed to do so. The transition to WFH thus forced some workers for the first time to expose their bedrooms—and their beds—to people outside their home, and sometimes large numbers of people, including strangers. What does it signify to conduct business from bed and to allow others to witness it?

Although in popular media during the earlier parts of the COVID-19 pandemic this was often presented as a new question, the role of the bed in personal and professional life is not a novel topic. Kings and queens (and occasionally politicians—famously, Winston Churchill) held court from bed, celebrities have staged their beds as sites of work or performance, while some sex workers have long worked from bed (whether digitally or IRL), as have sick or disabled people.[4] There is longstanding historical and political analysis of the bed as a public place and even as a place of work, which has only fairly recently been overshadowed by architectural practice and accompanying norms of gender, sexuality, class, and ethnicity that render it private. Imbricated with any modern narrative about the bed and bedroom is a liberal tradition in political theory of valuing privacy and equating the private sphere with the domestic, while imagining work as a humanity-enhancing activity that happens only in the public sphere. This in turn has been complicated by feminist critiques that point out how treating domestic space as a place of retreat, safety, and personal development for patriarchs is contrasted with (and in some ways depends upon) the home as a site of tedious and exhausting labour and a zone of violence for women—whether those women are unpaid wives or low-paid maids and nannies. The mappings between private and domestic space (and between public and working space) might seem increasingly like a historical curiosity, due to the widespread infringements on privacy that happen via digital surveillance, which knows no spatial boundaries, and the longstanding encroachment of work into home that digital technologies have encouraged. Nonetheless, the intrusions of working from bed (WFB) into working worlds increasingly populated by women and characterized by post-feminist ambivalence about sexuality and sexual exploitation in the workplace add new anxieties to existing trends. Further, neoliberal professional work is more and more characterized by “flexible” hours that bleed into non-work life and by the disciplining of proper attitude, affect, and comportment. Increased WFH has forced new constituencies to see domestic space as continuous with workspace and to experience their bedroom and bed as visible to strangers and as a site of surveillance.

This essay examines, first, the mediated performance of working from bed on the part of famous people, as captured in text, photograph, and video. Although these performances come with different degrees of artistic intention and creative artifice, they all solicit a relationship between viewer and celebrity. The privacy associated with the bedroom confounds the anonymity of the public figure with images that purport to invite a glimpse of the authentic person in their intimate life. The artist working from bed seems more available to their audience, more human. Given the associations of the bed with sex, these images also invite a voyeur’s gaze, tacitly or explicitly. Sometimes the connection is cosier, evoking in the twenty-first century a nostalgia for longhand writing and scribbling under the covers or reading aloud. At yet other times, the connection between the bed and sleep is key: the liminal states between waking and sleeping, as well as dreaming itself, are often represented as fertile for original creation; so the philosopher, painter, or poet who works from bed is also tacitly representing their mystical sources of inspiration. Whatever the specific connotation, these staged representations always solicit a play between public and private—the celebrity figure and the person behind the image—that recirculates representations of an individual who was already in the public eye.

By contrast, the enforced visual invasion of the home by the telemeeting does not aim to make white-collar workers more embodied, intimately available, or creatively impressive. If anything, the converse: coverage of the challenges of WFH during the COVID pandemic emphasizes the need to undo the connotations of the bed and the bedroom. It promotes the micro-management of a contemporary, attenuated “professionalism” attaching to WFB that is, we argue, an attempt to corral and legitimate class status for white-collar online workers.[5] A search for the phrase “working from bed” over the last five years in the media databases Factiva and ProQuest reveals, unsurprisingly, a huge spike in publications occurring in 2020 and 2021. In Factiva, 171 discrete publications (a total of 259 but including 88 similar duplicates) were published between March 15, 2020 and December 31, 2021. A thematic analysis of that dataset reveals that 25 are articles that mention WFB only very incidentally. Of the remainder, eight are primarily about sleep habits; nine are about celebrities where work and bed are mentioned; 26 are about health issues during the pandemic associated with WFB specifically or working from home in general (such as back problems or poor posture); and 32 are primarily consumer advice articles, focused solely on recommending laptops and laptop accessories or mattresses, pillows, and so on. The remaining 71 formed our core dataset, as they include discussion of WFB in the context of lifestyle and work-related challenges. Analyzing the top ten sources (which contained 126 of the 171 discrete hits), 84 (49 percent) appeared in British “broadsheet” news sources The Times, The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Financial Times, and The Independent, with nine appearing in the US in The New York Times and six in Dow Jones Newswires. Of the remainder, 19 appeared in UK tabloids The Daily Mail and The Daily Mirror, while 12 appeared in USA Today. (A similar search of Canadian Newstream reveals no hits that are not reprints of stories already running in US outlets.)[6] This distribution indicates that WFB was primarily a topic in media outlets with white-collar and middle-class readerships, and indeed the pieces that include substantive discussion of work image and professionalism—the primary themes of this project—appear almost solely in those outlets. The remainder of the sources discussed in this essay were identified by online searches for “working from bed,” which added a few radio and magazine items, as well as online-only sources not included in media databases, like Buzzfeed, Vice, and Salon.

The media texts we dwell on in this essay—features in The Guardian, The New York Times, The New Yorker, the BBC, and the CBC, for example—are jocular and chiding about image management, only rarely showing political sympathy with those whose WFB experience is constrained by poverty, sex work, illness, or disability,[7] and reinforcing (albeit often ruefully) norms of proper gendered comportment for online work.[8] They are more pretentious but hardly more critical than the tabloid outrage, listicles, and online exposés that proliferate around viral Zoom gaffes. WFB, in these contexts, must be represented as desexualized, appropriately separate from family relationships, and a visible extension of one’s properly dressed and mannered appearance in the office, at the same time as the impossibility of maintaining this façade is papered over with lifestyle discourse.

Celebrity, media, and lying down

Truman Capote famously described himself as a “horizontal author,” and lots of other famous writers and artists are known for working from bed.[9] For some, it is a place of retreat—a languorous location, free from the bureaucratic distractions of the desk. Capote eschewed the typewriter and wrote in longhand, saying in a 1957 interview in Paris Review, “I can’t think unless I’m lying down, either in bed or stretched on a couch and with a cigarette and coffee handy.”[10] Slavoj Žižek once recorded reflections on philosophy from his surprisingly tidy and frumpy bedroom, speaking from under his duvet, shirtless. Although viewers speculated on the significance of his exposed chest and reclined posture, Žižek himself claims not to have had an agenda, telling Salon acerbically that: the director “was [annoying] me all day... I was tired as a dog. She wanted to ask a few more questions. I said: ‘Listen, I will go to bed and you can shoot me for five more minutes.’ That’s the origin of it. Now, people look at it and say, ‘Oh what is the message that he’s half naked?’ There’s no message. The message is that I was fucking tired.”[11]

Tired, or sick: for other artists, working from bed is a way of doing great work while accommodating chronic illness. Marcel Proust spent the last three years of his life in his big brass bed dying of lung disease, rather like George Orwell, who finished 1984 while terminally ill with TB; W. G. Sebald wrote lying face down across his bed with his forehead on a chair due to back problems; and, after the awful bus accident in which Frida Kahlo was severely disabled, she spent long periods in a body brace, lying on her back and painting on a propped-up easel (see Fig. 1).[12] These twentieth-century bed workers are special individuals, fortunate (however they have managed it) to be working alone on their personal creations from a space that is often understood (in the modern bourgeois west) as deeply private and reflective of the individual’s innermost desires, thoughts, and identity. The concept of genius (so often coded as elite and masculine) trades on uniqueness—of talent and of personality—and the eccentrically personal space of the bed can connote that uniqueness. British artist Tracey Emin’s 1998 intermedial installation artwork My Bed, for example, showcased her actual “gloriously messed-up bed,” which was “surrounded by detritus such as condoms, blood-stained underwear, contraceptive pills and empty vodka bottles, [and] was the product of having spent four days in bed with depression” (see Fig. 2).[13] My Bed is a self-portrait—of vulnerability, chaos, pain, and intimacy—with no subject. It was both lauded and criticized as part of a tradition of eliding art and life and evoking the “mythology of expressive genius,” while at the same time it was read as a self-absorbed, even narcissistic artwork “trading on stereotypes of dysfunctional femininity.”[14] The personality of the bedroom is a historical and cultural quirk and certainly not true for many people who, for whatever reason, share this space, or don’t have their own bedroom at all.[15] Nonetheless, being a celebrated creator lends a kind of logic to working from bed—it is the place that is read as most about the unadulterated “you.” Representing oneself working from bed (rather than just doing it) thus makes an artist feel more available and proximate, inviting either voyeurism or cosiness. Children’s authors Michael Morpurgo and Cressida Cowell both nostalgically evoke their own childhoods—reminding us of their child readers but speaking to the experiences of those readers’ parents—when they describe writing by hand in exercise books as well as the comfort and intimacy of lying in bed to do it.[16] The bed is also a place of liminality—between sleep and waking, or day and night—where creativity might flourish because the line between rational, conscious thought and the unconscious world, including the world of dreams, is blurred. As writer Robert McCrum says: “If you write in bed in the early morning (as I do occasionally) you occupy an intriguing part of consciousness, somewhere between dreaming and wakefulness. Part of you is still in the shadowy cave of dream world; part of you is adjusting to the sharp brightness of reality. The mixture is fruitful and often suggestive.”[17] Someone who writes or paints in bed can claim to be accessing these intermediate states, making themselves more creatively alluring. Capote, Kahlo, Žižek (as well as Matisse, Dalí, and Robert Louis Stevenson—the list is long) were all able to use staged photographs to present these implications about their creative processes and intimate lives to public view and use this form of media to make a statement—tacit or explicit—about their identities as intellectuals and artists and about the relationship they offered their audiences.

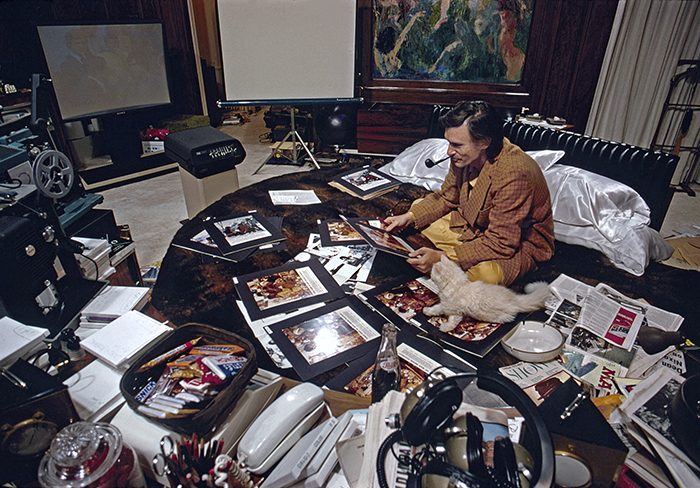

Beyond a particular photograph, artwork, or reference to WFB, some famous people have made a more systematic feature of their time in bed. Playboy CEO Hugh Hefner notoriously spent long periods there as part of a business project that was simultaneously aesthetic, sexual, technological, and commercial.[18] As Elizabeth Fraterrigo suggests in her history of Playboy, Hefner’s concept for the magazine as well as for his personal life was to reconstruct urban (domestic) space against the norms of post-war suburban family living. He masculinized the bedroom, not only through generic Playboy representations of the bachelor pad that rejected the ruffled bed linens and “his and hers” ensuite sinks of the grander suburbs but also by customizing it to his reclusive media mogul status. Hefner’s own, actual bedroom was a pre-internet telecommunication centre from which he coordinated his projects: taking calls, watching TV, receiving meals, and intermittently breaking from work (see Fig. 3). The reality is unclear, but Hefner’s work/play bed is also represented as incorporating multiple sexual interludes with the Playboy Bunnies who, in later years, lived with him in his mansion. Sex was very much a part of this working bed; the sex was, in part, the work (at least for the Bunnies). Hefner’s bed is thus typically hailed as digitally pioneering and culturally fascinating for its cult of celebrity and confounding of the public entrepreneur and the private man. Indeed, he is often compared to Louis XIV, who in the early 1700s held court in his Versailles bed chamber. The latter invited spectators to his daily ceremonies of getting up from and going to bed, using public ritual as part of a project of authority and symbolic power to obscure and then aggrandize the private man in his more embodied moments, when he might be seen as most human.[19] In his very different mid-century moment, Hefner used an intermedial spectacle to promote the values and lifestyle of his media empire.

The most elaborate attempt to turn the bed into a site of media representation was John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s famous “Bed-In for Peace”—a very public week in 1969, following their private wedding, that they spent on a piece of performance art in lieu of a honeymoon. In the Amsterdam Hilton International (and later in the Queen Elizabeth hotel in Montréal), they “held court” every day from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. from a huge bed, inviting reporters in to talk to them about international politics. They taped hand-lettered signs and drawings onto the walls and window (most famously, “Bed Peace” and “Hair Peace”) and surrounded themselves with flowers, mostly white; they also had white bed linens and wore flowing (and demure) white bedclothes. As Lennon said, “there were we like two angels in bed.”[20] Many visitors, including journalists and technicians with the cumbersome sound and video equipment of the time, crowded into the room and onto the bed itself (see Fig. 4).[21] The event initially attracted prurient interest because journalists believed (and probably Lennon and Ono floated the rumour) that they would be having sex in public. “Love-In Bores Photogs” was the headline in the Chicago Daily Defender: “The avant-garde newlyweds invited the press and friends to visit them Tuesday in their Hilton Hotel suite to see ‘something worth watching.’ Reports were the Beatle and his bride would engage in an uninhibited lovemaking.”[22] When the press showed up, however, Lennon “told the visitors he and Yoko would ‘just sit around in bed for seven days as a protest against all the suffering and violence in the world.’ He said it was preferable to ‘marching and smashing up building [sic]’.”[23] At one point in an interview, Lennon references Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance, and the phrase “Bed-In” of course invokes “sit-in”—another form of passive but disruptive political action. Nonetheless, both expressed their desire to “conceive a baby” during the week, albeit that it would happen in the private hours.

Beatriz Colomina argues that Lennon and Ono intended to blur the line between public and personal, turning the tables on the relentless invasion of privacy by the press to which they had been subjected as celebrities: “The Bed-In was... an artwork, a 24 / 7 piece by two hyper-dedicated art workers, challenging assumptions between what is inside and what is outside, what is everyday and what is performance.”[24] With its all-glass modernist design and panoramic views of Amsterdam (a city with a famous red-light district), the hotel room, she says, was both a voyeuristic and an exhibitionist space. A newly-married, young heterosexual couple in bed on their honeymoon of course evokes reproductive sex. By both affirming this connotation with their coy remarks about hoping to conceive and repudiating it with the intensely public and businesslike daytime exposure, however, Lennon and Ono played with the sexiness of the marital bed. Their pajamas and long nightshirt seem staid—more Wee Willie Winkie meets Sears catalogue than honeymoon lingerie—yet they snuggle up to each other under the covers as they speak to the cameras about politics. The same bed, for them, became a public workplace and a private place for sex, where they both conveyed their artistic and political messages and tried to make a baby. Colomina suggests they were “presenting themselves as sex workers,”[25] of a sort, with the bed as “both a protest site and factory for baby production: a fucktory.”[26]

The “lockdowns” of the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic prohibited concerts and plays and closed galleries but offered new opportunities for public figures to broadcast from more intimate stages. With strict rules against public gatherings, musicians reverted to acoustic concerts from home studios, and actors offered fireside readings.[27] Performing from bed was a part of these events: for example, singer-songwriter Dolly Parton (long-time supporter of the Imagination Library, which distributes free books for children) created a video series of her reading stories from her own bed, dressed in snug pajamas.[28] While more artistically constrained than the Bed-In, these performances also exploit narratives of authenticity through domesticity, the everyday, and the spectacular. In all these examples—celebrities writing about or soliciting photographs of themselves working from bed or inviting and making textual, photographic, and video documentary of being in bed as art—the performer cultivates a presentation of their intimate self to public view that creates the illusion of access to that individual’s private life, at the same time as it is, of course, a mediated spectacle also constitutive of a public image.

The rise of the pandemic bed middle-class

In stark contrast to these artistic mis-en-scènes, the 2022 movie Kimi[29] opens with a tableau that has quickly become a pandemic WFH trope: Bradley Hasling, a dough-faced white man in a suit and tie, speaks earnestly to a laptop about corporate performance. He is trying to sell his company. We see him as if from behind his screen, and behind him are wood-panelled bookshelves filled with a globe, three world clocks, and big volumes on tech issues. The camera cuts away to show the manager in a glass office he is speaking to, but also to reveal that he is in a concrete basement, and just out of shot are stacked chairs, metal shelving filled with junk, and a stepladder. The meeting ends, and as he stands, the shot reveals that he is wearing pajama bottoms. We all know now that WFH is about creating appearances.

In the 9–5 world, working from bed is commonly represented not as careful cultivation of a celebrity persona but as a persistent, grinding challenge to manage one’s own workaday self-presentation in a context where work and home involuntarily overlap. The white-collar worker is not a famous individual but an instantiation of a class of person, with a role that may lean on their specific skills or personality but that ultimately is interchangeable with other similar workers. Eccentric behaviour or creative performance is the opposite of the regularized, normatively appropriate “professional.” A profession, classically, is what Max Weber famously named a calling [Beruf]—an occupation requiring significant specialized training (usually in a university) that contributes to the social good, that its members undertake because of a commitment to certain other-oriented values, and that allows a high degree of autonomy, especially in judgments relating to how best to do the job.[30] “Being professional” for many workers today, however, is very far from creating social value, let alone having autonomy.[31] The soft literature in business worlds about “professionalism” mainly stresses the importance of qualities unrelated to the ideal of a calling (like dressing smartly or being punctual), as well as qualities that indicate docility more than autonomy (like putting in unpaid overtime or accepting without complaint tasks that fall outside your job description). In fact, as a now-longstanding sociological literature observes, the original connotations of “professionalism” have dwindled, as have the conditions of work that defined it,[32] and the concept has expanded far outside its original meaning to encompass modes of self-disciplining subjectivity in occupational domains beyond the traditional professions of doctor, teacher, lawyer, professor etc.[33] Workers across sectors are increasingly expected to absorb revenue uncertainties, unfair employment practices, or discriminatory treatment under the guise of “being professional,” which now rarely signals any particular training, expertise, duty of care, or job autonomy. For ethnic minority employees, professionalism can necessitate code-switching and performing the norms of workplace whiteness,[34] and for women it often implicates the double bind of meeting expectations for care-based emotional labour while simultaneously maintaining apparent detachment.[35] In fact, while the affective work of being sympathetic, friendly, polite, or apologetic is often required of a range of workers in the name of professionalism, this interpellation simultaneously demands a superficial emotional neutrality that shouldn’t include displays of grief, resentment, anger, or frustration.

As Valérie Fournier has argued, the “disciplinary logic” of professionalism both regulates actual professions and serves “to regulate the increased margin of indeterminacy created by the introduction of flexibility and emotionalisation of work” via technologies of the self.[36] WFH is sometimes touted as further increasing worker flexibility, in the sense that hours worked are more discretionary and can be more readily combined with non-work responsibilities if the employee is not constrained by commuting to an office for a fixed workday. As Fournier’s analysis implies, this in turn generates uncertainties about how workers are doing their jobs—whether they are being “productive” or presenting an appropriate face to clients now often invisible to supervisors, for example. We suggest that WFH thus triggers rhetorical responses oriented to affective and aesthetic forms of professionalism as a way of encouraging self-management in spaces associated with intimacy, emotional freedom, rest, domestic relationships, and sexuality. Because any residual distinction between private and public selves is confounded by the spatial politics of working from home, we are urged, by forms of media that ostensibly represent middle-class interests, to go to extra effort to keep it in place through our personal style.

For those forced by cohabitants, lack of space, or the demands of comfort to run their WFH enterprise from a bedroom, how to maintain the illusion that this bedroom is an office?[37] As the fictional Bradley Hasling models, one must have the means to keep the part of the room that forms a background neutral: clear away evidence of hoarding, or even just messiness, place a shelf behind the speaker with curated objects on it (erudite and relevant books, evidence of personal accomplishments), remove personal items (leaving perhaps just one framed photo of a normative family). Most of all, because bedrooms and beds are strongly associated with sex, a lot of the advice involves making sure that there are no connotations of sexuality in one’s Zoom space. At its most pointed, this means dissociating oneself from the stigma of sex work. Note that “camming”—livestreaming oneself performing sexual acts—is typically undertaken from one’s own bed in one’s own bedroom and involves a risky and challenging negotiation of private space and public labour. Digital sex work-from-bed also increased enormously in 2020 and 2021 as those laid off from the hospitality and retail sectors (predominantly younger women) turned to “amateur” sex work as a novel (and forced) measure to make ends meet.[38] Sociologist Angela Jones suggests that what she calls “embodied authenticity”—a form of voyeuristic pleasure shaped by the perception that clients are gaining a window into the everyday life of the sex worker—is a key part of successful camming.[39] Sometimes a bedroom that looks real can make the sex seem equally real, especially when contrasted with the contrived or slick sets of porn videos. As Kavita Nayar argues, in digital sex work performers “strategically deploy their amateur status to claim forms of capital unavailable to industry workers, who may be less accustomed to performing an authentic sexual self for, and intimately connect with, audiences in contexts that blur public and private space and time.” Nonetheless, discourses of “professionalism” are not absent from camming: “pro-am” performers may also “demand compensation for services and question the lack of regulation, social decorum, and enfranchisement they see in spaces of devalued sex work.”[40] Cam models directly confront the contradiction between social and sexual availability in one’s private space and the formal rules of proper workplace behaviour—including in their frequent breach by clients.

For white-collar workers, however, part of being a generic worker is also being an asexual worker, the aesthetics of whose home mimic the drab neutrality of office decor. Media coverage is full of injunctions to make sure there are no visible sex toys, condoms, or packets of birth control, no erotic art on the walls, and no porn sites open on screen-shared tabs. Consider, for example, Londoner Nicki Faulkner, 32, who works in HR and whom the Daily Mail (a sensationalist UK tabloid) represented with mock outrage as being “mortified” to have left a pink bottle of lube on the shelf behind her as she took a Zoom call with her boss.[41] Another injunction suggests workers keep the bed itself looking as much like a sofa as possible:[42] straighten the bed linens and line up the pillows, and avoid at all costs the rumpled duvet or stained sheets being visible. Favour plain neutrals,[43] rather than the vivid stripes or florals that might connote aesthetic personality, or the shiny red satin favoured by cam models. Sit on your bed, rather than lying in it.[44]

There is a gender politics to how sexual gaffes in virtual space are received and tolerated: Jeffrey Toobin was famously let go from The New Yorker magazine (but quickly rehabilitated to work at CNN) after video showed him masturbating during a business teleconference; and William Amos, the Canadian MP who appeared on Zoom during Parliamentary questions standing stark naked at his desk, initially got away with just an apology. When powerful men present their embodied or sexual selves on camera, there is often a question about whether they meant it: is it plausible that a seasoned journalist doesn’t know to turn off his camera before stroking his penis? While the MP claimed he was changing after a jog, he rather obviously held his phone in front of his crotch and, even when reprimanded by his party whip, was also complimented on being “en grande forme physique” (“in great shape”).[45] When the camera stays on, we are also more likely to see the seedy side of co-workers’ relationships. A colleague told one of us about a professor whose wife entered the room as he was wrapping up a synchronous class. Introducing her to his students, he suggested coyly that she might like to sit on his lap; she rejected the idea with overt disdain (much to the discomfort but also relief of the students). One of many gossipy and repetitive listicles of people caught doing inappropriate things on camera features men who are having sex with women across power lines—in this case, a lawyer having sex with a client, and a government official with a secretary.[46] Multi-member teleconferencing has the potential to reveal things to us about sex and power that might otherwise be hidden “behind closed doors.” In all these examples, powerful men who sexualize the telemeeting (whether entirely by accident or accidentally-on-purpose) get to be seen as a bit naughty, grandstanding, or even attractive. The feminist response that they are also behaving unethically and using bodily/sexual display to signal power is also legible to many (including, presumably, the management at The New Yorker) but always risks being seen as prudish or repressive—an excess of “cancel culture” in the face of “boys being boys.”

Nonetheless, being fully clothed (at least from the waist up) while WFH is recommended.[47] This rather obvious advice seems weightier for workers who were already trying to avoid being sexualized in the workplace, for whom the forced intimacy of Zooming from bed feels risky and already uncomfortably close to camming. If powerful men dabble in the frisson of online sexiness, women are sternly urged to avoid lowcut tops that are too revealing if they reach over to adjust the ring light. The Alabama school board employee caught on camera in January 2022 either being shaken awake or penetrated from behind by a man who sometimes appeared in the shot (opinions varied) risked being seen as both seriously out of bounds and an object of mockery or even disgust—a reaction compounded by the fact that she is African American and vulnerable to being stereotyped both as hyper-sexual and as less professionally competent. Women caught naked on Zoom by accident are often mothers, changing in the background of their kids’ online school, or (inept, older) women who are represented as lacking technological savvy when they pull off their sweater without first turning off the camera.[48]

Contrast the demand to avoid under-clothed, and hence sexualized, appearances with positive advice that seems determined to make occupying the bed seem like a lifestyle choice that involves intermittent napping rather than a complex intrusion into personal space. For example, in an article in The Guardian headlined “Working from Bed? Here’s How You Can Still Look Professional,” Morwenna Ferrier suggests, bizarrely, going online to buy first-class airline pajamas-in-a-bag (a little bit PJ, a little bit business-like) and embracing the all-day dressing gown. As she points out, daytime in a robe is associated with the louche, campy aesthetic of Noël Coward (famous for his glamorous silk sleepwear), for whom it tacitly signalled sexual openness in the face of homophobia[49]—more transgressive, perhaps, but not that different from Hefner’s advertised sexual laissez-faire. This column seems more interested in fashion than work, and its advice jibes with trends, pre-pandemic and redoubled since, for athleisure and crossover sleepwear. Sweatpants for hanging out in (rather than exercising) or robes that double as wrap dresses have been staples of casual dressing for some time, but WFB has provided further commercial reason to blur the distinction between clothes to work in and those to sleep in. In 2020 there was a flurry of media interest in “The Nap Dress”—a simple, feminine, shirred cotton dress produced by a company that had initially manufactured luxury bedding. In her New Yorker analysis of the Nap Dress, which she calls “the look of gussied-up oblivion,” Rachel Syme suggests that “an outfit specifically designated for daytime dozing might be just the thing. One could theoretically wear a Nap Dress to bed, but it is decidedly not a nightgown.”[50] Although the article is about entrepreneur Nell Diamond, the hard-nosed businesswoman who trademarked the term “Nap Dress” in January 2020, there is no discussion of wearing the Nap Dress to segue between sleeping and WFH. Further, while several Black models are featured wearing it (including in the image reproduced for Syme’s New Yorker story), it seems like a distinctively bourgeois white woman’s garment—for its aesthetic associations with pre-Raphaelite ivory-skinned beauties or consumption-ridden Victorian invalids, and also for the implication that it is worn to enable privileged, languid drifting from bed to novel-reading to cocktail hour. This is not a dress for work. In short, discussions of what women should wear during the pandemic have often been more suited to the low-stakes world of the fashion-forward lady who lounges than to the harried teacher, mortgage advisor, or office manager. Men, as ever, have fewer difficult choices to make because the palette of neutrality is broader. The same party whip who admired William Amos’ naked physique reminded representatives that a jacket and tie are required for for online parliamentary meetings, but stressed that they were also obliged to wear “le chemisier, le caleçon ou le pantalon” (“a shirt, underwear, or pants”).[51]

The next challenge for WFB is other people. When kids interrupt their father, it reminds others about his grownup status as a family man as well as his human side. Recall academic Robert Kelly, who went viral in 2017 when his earnest commentary on Korean politics to the BBC from a bedroom Skype call was interrupted by his two young children, who were quickly pulled from the room by their mother. Commentary at the time circulated around the failure of “the nanny” (Kelly’s wife is Korean) to manage the children while their father was doing important work, while Kelly himself became a transient celebrity, resigned to his status as “BBC Dad.” When children interrupt their mother at work, we are warned, it is annoying and evidence that she is harried and juggling too many things.[52] Again, this dynamic is not without its feminist contrasts: in some workplaces, the introduction of kids or pets to meetings can be a brief moment for connection and shared affection (even if some people are just tolerating it) and reflects the sentiment that if work intrudes into one’s home, one’s home is justified in intruding sometimes into work. The risk then becomes that, rather as the clients of cam models like to see a little bit of normal life, so the cute cat or baby appearance offers a moment of authenticity designed to temper the alienation of WFH without challenging its injustices.

There is a way to deal with a lot of these tensions—just mute yourself and switch off your camera. We heard numerous complaints from professors, however, about speaking to a grid of muted dark squares during online teaching, as students lurk at the edges of a synchronous class. To be a black square with just a name on it is a way of staying in control of how you experience the meeting: there is less risk of intrusion or embarrassment of the kinds we have been describing but also less chance that the instructor will ask you a question or attempt to engage you in conversation. For students (K–12 or postsecondary) who are required to attend online, this is also a way of appearing to be present when you may have left the class, attentionally (to game on another tab) or literally (wandered off for a snack). Zoe Williams recognizes that, “ideally, you want to turn your video off as soon as you can, claiming poor wifi or a desire to subvert office hierarchies. (This is a thing now, apparently: only senior staff turn their video on. …) Still, you will probably have to have it on at the start, just to prove you have arrived.”[53] It is true that the more senior people in meetings keep their cameras on, and Heyes, a professor, has noticed that in large faculty meetings some colleagues remain visible throughout as a way of moving their live head up to the top of the feed. As Haugen, an undergraduate student, put it, keeping your camera on is like sitting in the front row of class—you may not be able to dodge engagement with what’s going on, but the plus side is that you’ll be noticed, registered as a keener. Bosses can try insisting that their employees keep the camera on throughout, but this breeds resentment about intrusion into one’s private space and an alternative Bartlebyian resistance in the form of glazed eyes and stubborn silences.

These negotiations are part of our lexicon now. When Kim Kardashian arrived at the 2021 Met Gala wearing a light-absorbing matte black, body-covering outfit that included a tightly fitted opaque balaclava, she was modelling the present absence of the black Zoom square by showing up to the event but somehow hiding from it.[54] Instead of being digitally present but visually absent, she managed to be physically present while visually absent—an extraordinary extension of the demand for privacy that switching off one’s camera demands and surely a statement about her own overweening celebrity, with its juggling of constant media provocation with the familiar celebrity double standard that she also deserves a life apart from scrutiny. Her sister Kendall wore a body-revealing nude dress—perhaps deliberately, precisely the converse outfit—that rendered her fully physically present in media coverage. When they were photographed together (see Fig. 5), they represented an intense opposition of complete exposure and complete concealment—one pure presence, the other pure absence. Emin’s My Bed could be read as the 1990s precursor to Kardashian’s disappearing outfit—another representation of self without the person—and indeed both women have been accused of being “famous for being famous,” implying that they lack real talent and exist only in superficial celebrity. To remove oneself from a self-representation could be understood as a way of satirizing that insult and making a paradoxical statement about the value of anonymity, without abandoning one’s personality.

* * *

The conversation between journalist Piya Chattopadhyay and architectural historian Beatriz Colomina on CBC Radio about working from bed has a little more political savvy than the broadsheets’ “lifestyle” approach.[55] Colomina refers to growing exploitation in the gig economy and the relative privilege that comes with doing white-collar work from bed. For the post-COVID middle-class, this will nonetheless continue the longstanding erosion of the line between public and private, work and personal life. This is both a spatial and a temporal shift: our homes are increasingly places of work, surveilled by co-workers and bosses, and our time is increasingly porous, with our work tools (digital devices) sitting in our homes 24/7 and making us continuously available for work. Colomina pointedly says to Chattopadhyay that for many of us the last thing we touch before lying down to sleep and the first thing we touch on waking is not our partner but our phone. The activities we used to reserve for bed—what in sleep hygiene are referred to as the three S-s (sleep, sex, sickness)—might become more like work: schedule your sex; make your sleep productive. Although the media directed to the new bed middle-class focuses on ergonomic pillows and back health,[56] keeping the kids out of the bedroom, neutral decor, and nap dresses, this superficiality covers over an increasingly invasive employment world in which getting ahead at work could easily come to have a lot to do with how quiet, spacious, and well-equipped your own home is. It will also require a “professional” self-presentation still structured by disciplinary demands that we conform and comply at work, but one we must assume in our very homes, and even in our beds. Those who face intimate partner violence or overcrowded housing are already excluded from the positive aspects of having personal space. The intrusion of work marks another level of incorporation of time and space by the demands of capital.[57] The media coverage we have cited here is jokey and aspirational, looking upward to bed celebrity and voyeuristically noting the travails of the bed proletariat; or earnest and problem-solving, suggesting that a new computer mount is what you most need.[58] It often treats WFB for ordinary white-collar workers as if it were like the staged performances of famous writers or artists and, hence, as if it is susceptible to similar manipulation. The amount of power and control that bed workers can exert over their mediated image is, however, very different, as is its purpose. Being forced to be “professional” in their bed, even though only intermittently, might cost them the profound messiness of an identity that used to explode in their own space; in this context, it is not just the quality of the space that is lost but, in a sense, their sense of self. This is paradoxically the opposite effect of WFB for the celebrity who deploys bed images as a vehicle for their authenticity or creative distinction.

Colomina says that in bed we disclose our secrets. It is a place of closeness, pillow talk. We don’t mean to idealize privacy—as a structuring concept, an ideal, or a reality—but even apart from WFB, work has become tentacular, colonizing more and more of our lives. Although the “end” of the COVID pandemic has initiated a popular discourse about compelling reluctant white-collar workers back into the office, it seems likely that WFH or hybrid working will remain more common than in 2019 and will continue to present the same challenges. Combine the ongoing reality of WFH with growing cultural resistance to employer prerogative and more competitive employment markets for highly educated workers, however, and we hope that the disciplinary discourse about professionalism in the home workspace will be nuanced by more critical perspectives on what is expected of those who join workspaces from their intimate worlds.

Figure 1

Juan Guzman, Frida Kahlo painting from bed at Hospital Inglés, black and white photography, Mexico City, 1951.

Figure 2

My Bed, 1998 © Tracey Emin / DACS London / CARCC Ottawa 2023. Image courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd 2023.

Figure 3

John G. Zimmerman, Hugh Hefner’s early digital working bed, colour photography, Chicago, 1973.

Figure 4

Getty Images, John Lennon and Yoko Ono at their “Bed-In,” black and white photography, Amsterdam Hilton, 1969.

Figure 5

Jamie McCarthy, Kendall Jenner and Kim Kardashian West attend the 2021 Met Gala in New York, Getty Images for The Met Museum, Vogue, Met Gala, 2021.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Cressida J. Heyes is Henry Marshall Tory Chair and Professor of Political Science and Philosophy at the University of Alberta. They are the author of three monographs: Anaesthetics of Existence: Essays on Experience at the Edge (Duke University Press, 2020); Self-Transformations: Foucault, Ethics, and Normalized Bodies (Oxford University Press, 2007); and Line Drawings: Defining Women through Feminist Practice (Cornell University Press, 2000), and are currently working on a fourth, a feminist philosophy of sleep tentatively called Sleep is the New Sex. Their article, “Reading Advice to Parents About Children’s Sleep: The Political Psychology of a Self-Help Genre” is newly published in Critical Inquiry. Find out more at http://cressidaheyes.com.

Hannah Haugen holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Gender Studies from the University of Alberta and currently works in youth restorative justice. She began a JD/JID program at the University of Victoria in 2023.

Notes

-

[1]

Office for National Statistics, “Coronavirus and Homeworking in the UK: April 2020,” Census 2021, 8 July 2021, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020 (accessed 29 May 2023); Joey Marshall, Charlynn Burd, and Michael Burrows, “Those Who Switched to Telework Have Higher Income, Education and Better Health,” United States Census Bureau, 31 March 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/working-from-home-during-the-pandemic.html (accessed 29 May 2023); Zechuan Deng, René Morissette, and Derek Messacar, “Running the Economy Remotely: Potential for Working from Home During and After COVID-19,” Statistics Canada, 28 May 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00026-eng.htm (accessed 29 May 2023).

-

[2]

Brian Fagan and Nadia Durrani, What We Did in Bed: A Horizontal History, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2019, p. 160–179; Hilary Hinds, A Cultural History of Twin Beds, London, Routledge, 2019.

-

[3]

Ben-Ari Eyal, “It’s Bedtime’ in the World’s Urban Middle Classes: Children, Families, and Sleep,” Lodewijk Brunt and Brigitte Steger (ed.), Worlds of Sleep, Berlin, Frank and Timme, 2008, p. 178–183; Why Do Kids Have Their Own Bedrooms?, Andrew Kornhabe, 2018, YouTube, PBS Origins, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rp5OnpfyNVA&t=5s (accessed 29 May 2023); Matthew Wolf-Meyer, “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep: Children’s Sleep and the Rise of the Solitary Sleeper,” The Slumbering Masses: Sleep, Medicine, and Modern American Life, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2012, p. 129–143; and Benjamin Reiss, “Wild Things,” Wild Nights: How Taming Sleep Created Our Restless World, New York, Basic Books, 2017, p. 141–170.

-

[4]

Fagan and Durrani, 2019, p. 143–159; Beatriz Colomina, “The Century of the Bed,” curated by vienna, The Century of the Bed, Verlag für Moderne Kunst, Vienna, 2014; “The 24 / 7 Bed,” Work, Body, Leisure, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Rotterdam, 2018, https://work-body-leisure.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/247-bed (accessed 29 May 2023), “The 24/7 Bed: Privacy and Publicity in the Age of Social Media,” Anna Haas, Maximilian Haas, Hanna Magauer, and Dennis Pohl (ed.), How to Relate: Wissen, Künste, Praktiken/Knowledge, Arts, Practices, Bielefeld, Transcript Verlag, 2021; Johanna Hedva, “Sick Woman Theory,” Topical Cream, 12 March 2018; https://topicalcream.org/features/sick-woman-theory/ (accessed 29 May 2023).

-

[5]

For a thematic analysis of journalistic coverage that draws similar conclusions but also focuses on cross-class analysis of labour inequalities and COVID risk burdens, see Brian Creech and Jessica Maddox, “Of Essential Workers and Working from Home: Journalistic Discourses and the Precarities of a Pandemic Economy,” Journalism, vol. 23, no. 12, 27 January 2022.

-

[6]

We don’t analyse the fact that UK publications dominate this dataset, except to point out the higher proportion of people in the UK WFH in 2020 in comparison to the US and Canada. See endnote no. 1.

-

[7]

See the widely reprinted article by Taylor Lorenz, “Working from Bed is Actually Great,” New York Times, 31 December 2020 for an interesting example that deviates briefly into this terrain.

-

[8]

Daniel Lark, “How Not to Be Seen: Notes on the Gendered Intimacy of Livestreaming the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Television & New Media, vol.23, no. 5, 5 March 2022, p. 462–474.

-

[9]

Sam Wollaston, “Duvet or Don’t They: Why Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen Loves Working from Bed and Glenda Jackson Doesn’t,” The Guardian, 20 January 2021.

-

[10]

Pati Hill with Truman Capote, “The Art of Fiction XVII: Truman Capote,” The Paris Review, no. 17, Spring–Summer 1957, p. 46.

-

[11]

Katie Englehart, “Slavoj Zizek: I Am Not the World’s Hippest Philosopher,” Salon, 29 December 2012, https://www.salon.com/2012/12/29/slavoj_zizek_i_am_not_the_worlds_hippest_philosopher/ (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[12]

Marcus Coates, “Vertical and Horizontal Writing,” Mindful Content, 4 March 2021, https://www.mc-mindful-content.com/post/mindful-content-vertical-horizontal-writing (accessed 9 June 2023); Kitty Burns Florey, “7 Famous Authors Who Wrote Lying Down,” HuffPost.com, 7 January 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/famous-author-who-wrote-l_b_4555808 (accessed 9 June 2023).

-

[13]

Stephen Moss, “Ten Beds That Changed the World: From King Tut to Tracey Emin,” The Guardian, 22 January 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/22/ten-beds-that-changed-the-world-from-king-tut-to-tracey-emin (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[14]

Deborah Cherry, “Twenty Years in the Making: Tracey Emin’s My Bed, 1998–2018,” Alexandra Kokoli and Deborah Cherry (ed.), Tracey Emin: Art into Life, London, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020, p. 50.

-

[15]

Fagan and Durrani, 2019, p. 160-179. In the recognizable but parochial cultural imagination we are summarizing here, sharing a bedroom with a spouse is treated as more ontologically unifying than any other kind of bedroom sharing, although of course privacy intrusions, disrupted sleep, or intimate violence are commonplace among bedroom-sharing couples. The advent of the marital couple’s “master” bedroom as a household norm, changing mores about twin and double beds, and what this has assumed about heterosexuality, domestic space, and the couple relationship is treated at length elsewhere (see Hinds, 2019, esp. p. 127-235). See also Wolf-Meyer, 2012, p. 99–128 for discussion of bed-sharing couples negotiating sleep disorders, and Cressida J. Heyes, “Advice to Parents on Children’s Sleep: The Political Psychology of a Self-Help Genre,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 49, no. 2, 2023, p. 145–164, for discussion of the politics of parents bed-sharing with children—another perennial controversy that regulatory ideals about the bed as a locus of privacy and individuality both take up and obscure.

-

[16]

iTeam, “Michael Morpurgo: "I Always Write in Bed—Lying Down, By Hand, In an Exercise Book’,” iNews, 8 January 2021, https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/michael-morpurgo-war-horse-ted-hughes-robert-louis-stephenson-822125 (accessed 30 May 2023); Alex Johnson, “A Tour of Cressida Cowell’s Writing Shed,” Shedworking 3 May 2020, https://www.shedworking.co.uk/2020/05/a-tour-of-cressida-cowells-writing-shed.html (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[17]

Robert McCrum, “The Advantages of Writing in Bed,” The Guardian, 28 April 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2011/apr/28/writing-in-bed-robert-mccrum (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[18]

Colomina, 2021, p. 195–196; Paul B. Preciado, “Learning from the Virus,” Artforum, May / June 2020, https://www.artforum.com/print/202005/paul-b-preciado-82823 (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[19]

Fagan and Durrani, 2019, p. 152–156; Moss, 2021; Chateau de Versailles, “The King’s Chamber,” The King's Apartment. Around the Marble Courtyard, 2022, https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/estate/kings-apartments#the-kings-chamber (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[20]

John Lennon, quoted in The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology, San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 2000, p. 333.

-

[21]

Bed Peace starring John Lennon & Yoko Ono (1969), John Lennon and Yoko Ono, June 22 2012, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mRjjiOV003Q (accessed 30 May 2023), 1:10.

-

[22]

“Love-In Bores Photogs,” Chicago Daily Defender, 27 March 1969.

-

[23]

Ibid.

-

[24]

Colomina, 2021, p. 190.

-

[25]

Ibid., p. 189.

-

[26]

Ibid., p. 188.

-

[27]

Spring Duvall, “Quiet Celebrity in the Time of Pandemic: Stripping Away Artifice in Performances of Self, Cultures of Citizenship, and Community Care,” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 36, no. 2, 229–243, 2022.

-

[28]

“Good Night With Dolly Parton,” Episode 1, Dolly Parton reads “The Little Engine That Could”, Dolly Parton, April 2 2020, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tT9fv_ELbnE&list=PLzSkd2YQ-Hql7hXwee25MhzEIavU0U2Jm&index=10 (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[29]

Kimi (Steven Soderbergh, 2022).

-

[30]

Howard S. Becker, “The Nature of a Profession,” Sociological Work: Method and Substance, Chicago, Aldine, 1970, p. 87–103.

-

[31]

Julia Evetts, “Professionalism: Value and Ideology,” Current Sociology Review, vol. 61, no. 5–6, 2013, p. 778–796.

-

[32]

Jane Broadbent, Michael Dietrich, and Jennifer Roberts (eds.), The End of the Professions? The Restructuring of Professional Work, Abingdon, Routledge, 1997.

-

[33]

Valérie Fournier, “The Appeal to ‘Professionalism’ as a Disciplinary Mechanism,” The Sociological Review, 1999, p. 280–307.

-

[34]

Marcus W. Ferguson and Debbie S. Dougherty, “The Paradox of the Black Professional: Whitewashing Blackness through Professionalism,” Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 1, 2022, p. 3–29.

-

[35]

Amy Wharton, “The Sociology of Emotional Labor,” Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 35, 2009, p. 147–65.

-

[36]

Fournier, 1999, p. 293.

-

[37]

For an ethnographic analysis of how families in Sydney transformed their spatial experience of home and work via digital technology during 2020, see Ash Watson, Deborah Lupton, and Mike Michael, “The COVID Digital Home Assemblage: Transforming the Home into a Work Space During the Crisis,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 27, no. 5, p. 1207–1221, 26 July 2021.

-

[38]

Quispé Lopez, “People are Turning to OnlyFans to Earn Money After Losing Their Jobs During the Pandemic,” Insider, 17 June 2020, https://www.insider.com/people-are-creating-onlyfans-accounts-after-losing-jobs-during-pandemic-2020-6 (accessed 12 June 2023); Angela Jones, “Sex Work, Part of the Online Gig Economy, Is a Lifeline for Marginalized Workers,” The Conversation, 13 May 2021, https://theconversation.com/sex-work-part-of-the-online-gig-economy-is-a-lifeline-for-marginalized-workers-160238 (accessed 12 June 2023).

-

[39]

Angela Jones, Camming: Power, Money, and Pleasure in the Sex Work Industry, New York, New York University Press, 2020, p. 46.

-

[40]

Kavita Nayar, “Working it: The Professionalization of Amateurism in Digital Adult Entertainment,” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 17, no. 3, 2017, p. 485–486.

-

[41]

Clare Toureille, “Don’t Zoom In! Woman, 32, Is Left Mortified after Realising She’d Left a Bottle of Lubricant in Full View During a 45-minute Call with her Boss She Took from Bed,” Daily Mail, 29 November 2021, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-10253657/Girlfriend-mortified-leaving-bottle-lubricant-view-manager-Zoom-call.html (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[42]

Kirstie Alsopp, quoted by Wollaston, 2021.

-

[43]

Emine Saner, “Why You Shouldn’t Work from Bed, and a Guide to Doing It Anyway,” The Guardian, 20 January 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/20/why-you-shouldnt-work-from-bed-and-a-guide-to-doing-it-anyway (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[44]

Zoe Williams, “‘Never Conduct Any Business Naked’: How to Work from Bed Without Getting Sacked,” The Guardian, 21 January 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/21/never-conduct-any-business-naked-how-to-work-from-bed-without-getting-sacked (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[45]

Jean-François Racine, “Un Député Surpris Flambant Nu En Période de Questions,” Le Journal de Québec, 14 April 2021, https://www.journaldequebec.com/2021/04/14/un-depute-surpris-flambant-nu-en-periode-de-questions (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[46]

Sumedha Tripathi, “8 Instances Where People Got Caught Naked on Camera During Zoom Calls,” Scoop Whoop, 16 April 2021, https://www.scoopwhoop.com/humor/8-instances-where-people-got-caught-naked-on-camera-during-zoom-calls/ (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[47]

Williams, 2021; Adam Tschorn, “Enough with the WFH Sweatpants. Dress Like the Adult You’re Getting Paid to Be,” Los Angeles Times, 17 April 2020, https://www.latimes.com/lifestyle/story/2020-04-17/working-from-home-regular-work-wardrobe-dress-up (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[48]

Tripathi, 2021.

-

[49]

Morwenna Ferrier, “Working from Bed? Here’s How You Can Still Look Professional,” The Guardian, 20 January 2021.

-

[50]

Rachel Syme, “The Allure of the Nap Dress: The Look of Gussied-Up Oblivion,” The New Yorker, 21 July 2020.

-

[51]

Claude DeBellefeuille, quoted in Racine, 2021.

-

[52]

Williams, 2021. For feminist analysis of (and pushback against) this demand to erase evidence of home and family from women’s digital work life, see the discussion in Lark, 2021, p. 463–464.

-

[53]

Ibid.

-

[54]

I owe this example and this interpretive point to Catherine Clune-Taylor, in personal communication also with Meredith Jones.

-

[55]

Piya Chattopadhyay and Beatriz Colomina, “How the Pandemic Is Making Work and Sleep Strange Bedfellows,” The Sunday Magazine, 20 September 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/radio/sunday/the-sunday-magazine-for-september-20-2020-1.5726357 (accessed 12 June 2023).

-

[56]

Bryan Lufkin, “What Happens When You Work from Bed for a Year,” BBC, 17 February 2021, https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210217-is-it-bad-to-you-work-from-your-bed-for-a-year (accessed 30 May 2023).

-

[57]

Jilly Boyce Kay, “Stay the Fuck at Home!”: Feminism, Family and the Private Home in a Time of Coronavirus,” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 20, no. 6, 18 May 2020, p. 883–888.

-

[58]

Lorenz, 2020.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Juan Guzman, Frida Kahlo painting from bed at Hospital Inglés, black and white photography, Mexico City, 1951.

Figure 2

Figure 3

John G. Zimmerman, Hugh Hefner’s early digital working bed, colour photography, Chicago, 1973.

Figure 4

Figure 5