Résumés

Abstract

Human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation is undoubtedly occurring in Northeastern Ontario. However, there is a lack of information, resources, coordination, and collaboration on the issue in comparison to Southern Ontario. Furthermore, urban-based programming from “down south” does not necessarily fit the unique circumstances of Northeastern Ontario: specifically, the isolation and underservicing of rural and remote communities, the presence of francophone communities, and diverse Indigenous communities. The Northeastern Ontario Research Alliance on Human Trafficking is a community-university research partnership that takes a critical anti-human-trafficking approach. We combine Indigenous and feminist methodologies with participatory action research. In this paper, we first present findings from our eight participatory action research workshops with persons with lived experience and service providers in the region, where participants identified the needs of trafficked women and gaps and barriers to service provision. Second, in response to participants’ calls for collaboration, we have developed a Service Mapping Toolkit that is grounded in Indigenous cultural practices and teachings, where applicable, and in the agency and self-determination of persons experiencing violence, exploitation, or abuse in the sex trade. We conclude by recommending seven principles for building collaborative networks aimed at addressing violence in the sex trade. The Service Mapping Toolkit and collaborative principles may assist other rural or northern communities across the county.

Keywords:

- Critical anti-human trafficking,

- participatory action research,

- service mapping,

- Indigenous methodologies,

- feminist intersectionality,

- social work

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation is undoubtedly occurring in Northeastern Ontario. However, we are behind Southern Ontario in terms of research, information, coordination, and collaboration. While there is substantial literature on the incidence of cross-border and domestic trafficking in Canada (Boyer & Kampouris, 2014; Canadian Women’s Federation, 2014; Norfolk & Hallgrimsdottir, 2019; Oxman-Martinez et al., 2005; Perry, 2018; Sethi, 2007; Sikka, 2009; Sweet, 2015), there is an absence of research on the specific circumstances of Northeastern Ontario, namely, the isolation and underservicing of rural and remote communities, the presence of francophone communities, and diverse Indigenous communities. In particular, little has been written on specific tools and practical ways to support those currently being trafficked and human trafficking survivors (exceptions include Dandurand, 2017; Kaye et al., 2014) to overcome the gaps in and barriers to service provision identified by this study.

In August 2013, in response to this dearth, we formed the Northeastern Ontario Research Alliance on Human Trafficking (NORAHT), a research partnership between the Amelia Rising Sexual Assault Centre of Nipissing, the Union of Ontario Indians: Anishinabek Nation, the AIDS Committee of North Bay and Area, and Nipissing University.[1] Over the past seven years, NORAHT has embarked on a research journey as a collaborative group from diverse professional backgrounds and practice approaches. We focus on the trafficking of women,[2] as violence against women is a central component of the work of our community-based research partners. However, we acknowledge here that Two Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer persons (2SLGBTQ+) are also vulnerable to human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation. We place a special focus on the trafficking of Indigenous women because nationally they are over-represented in human trafficking cases (Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2013), and furthermore, 78% of Ontario First Nations peoples are located in Northern Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, 2018). Using participatory action research (PAR) grounded in feminist and Indigenous methodologies, we have sought to identify the needs, gaps, and barriers for persons who have been trafficked in our region as a means to develop service provider toolkits and recommend social policies.

In the spring and fall of 2017, we held eight full-day PAR workshops with service providers and persons with lived experience in sex work and human trafficking. During the PAR workshops, our participants identified the needs of trafficked persons, the gaps and barriers to funding and resources in our region, and a need for collaboration and education amongst service providers about the need for culturally appropriate wrap-around support. In this paper, after first providing readers with the background and context of our study, we outline our methodology and findings from the PAR workshops, which have not only provided us an understanding of the existing gaps and barriers but also informed our feminist and decolonial outlook on the issue of human trafficking. In response to our participants’ calls for collaboration, we then present our design of a service mapping toolkit to assist communities in developing responses to human trafficking that are grounded in trauma- and violence-informed and harm reduction approaches cognizant of Indigenous cultures, where applicable, and in the agency and self-determination of persons experiencing violence, exploitation, or abuse in the sex trade. We conclude the paper by proposing seven main principles for developing collaborative networks for the provision of wrap-around, comprehensive supports, based on the approaches, knowledges, and programs identified in the service map. We are grateful to those with lived experience who have shared their stories to aid in the development of collaborative responses to human trafficking in Northeastern Ontario. This grassroots effort to respond to human trafficking at the local level will hopefully assist other rural and northern communities across the country.

Background and Context: Critical Anti-Trafficking, Agency, and Empowerment

The Criminal Code of Canada defines domestic human trafficking as the “recruiting, transporting, transferring, receiving, holding, concealing or harbouring of a person” (279.01) or “exercising control, direction or influence over the movements of a person, for the purpose of exploiting them or facilitating their exploitation” (279.01). As various scholars have noted, the ambiguity of “sexual exploitation” means that how one defines human trafficking is widely contested and complex (Boyer & Kampouris, 2014; Doezema, 2002; Roots, 2013). We take a critical anti-trafficking approach (Shalit & van der Meulen, 2015) and explicitly understand human trafficking to be distinct from sex work.[3] Whereas human trafficking involves elements of coercion, force, duplicity, and loss of control, sex work is a chosen form of labour.[4] Moreover, we do not conceive of coercion and consent as a rigid dichotomy. Rather, as one of our participants put it, there is a spectrum from sex work to human trafficking, and women’s experiences are “fluid” along this spectrum. Rather than viewing trafficked persons as abject victims who have no agency, we argue that people experience “situational coercion” and make “reluctant choices” that are “often rational” in the face of considerable constraints (Hoyle et al., 2011, p. 322). Further, as one trafficking survivor relates, “even within the most coercive and violent situations there is a sufficient degree of agency and autonomy to ensure survival and self-preservation” (Cojocaru, 2016, p. 8).

In taking a critical anti-trafficking approach that emphasizes agency and resilience, we also challenge “rescue narratives,” which predominate anti-trafficking campaigns and media representations (Baker, 2014; Cojocaru, 2016; Kempadoo, 2015). Framing Indigenous women as helpless victims perpetuates stereotypes of them as “lacking in agency, choice, or voice,” wrote Kwakwaka’wakw scholar Sarah Hunt (2010, p. 27). This invites colonial interventions, such as the increased policing and surveillance of Indigenous communities and sex workers, while depoliticizing systemic disenfranchisement (Hunt, 2010; Maynard, 2015). Indigenous peoples, both historically and currently, have too often experienced harm in the name of social policy and service provision. Indigenous genocide through the residential school system and its ongoing legacies, including intergenerational cycles of abuse and disproportionate rates of child welfare removal, incarceration, and poverty, is one glaring example of “civilized saving.” Combined with the “race, identity and gender-based genocide” of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQ+ people (National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls [NIMMIWG], 2019, p. 5), these legacies generate multiple vulnerabilities to violence against Indigenous women and girls in the sex trade, including human trafficking. There is over-surveillance and under-protection in service provision, notably policing and child welfare. Further, as our participants noted in discussions, emergency rooms are often the first or only point of contact that trafficked persons might have to seek support. Yet, sometimes there is overt racism and stigmatization of commercial sex in the delivery—or denial—of health care services.

NORAHT challenges the stigmatization of sex work and believes that current prostitution laws in Canada, which criminalize the purchase of sex, jeopardize the safety of sex workers and drive traffickers further underground (Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform, 2017). That said, we recommend that agencies and communities focus on supporting those who have experienced harms and violence and who ask for help. To paraphrase Dr. Robyn Bourgeois (Cree scholar/activist), who testified at the NIMMIWG (2019), despite different positions, at the end of the day, we all recognize that women are experiencing violence in the sex industry and “we want our girls and our women to be safe no matter what” (Vol. 1, p. 657). Furthermore, we cannot assume to know better than trafficked persons what their unique needs are at any given time. In particular, trafficked women may not desire strategies to “exit” from the sex trade per se, but only from their abusive situation.

In order to develop effective and appropriate strategies, the paid involvement of persons with lived experience in the collaborative network is crucial, i.e., survivor-champions,[5] sex workers, or family members. The idea of nothing about us without us[6] is key to developing policy frameworks and frontline supports, including peer outreach and support, that meet the needs of individuals in a manner that respects their autonomy, self-determination, and empowerment, and is without judgment. Every person’s subjective experience of violence and exploitation is complex, and we need to consider the person in the context in which they have been living. As we develop later in the Service Mapping Toolkit, this necessitates decolonial trauma and violence-informed supports,[7] that are culturally relevant and sensitive to harm reduction approaches. Together, these approaches understand trauma not as an isolated event, but as embedded in colonial violence and other forms of marginalization.

Moreover, as Bonnie Burstow explained:

Trauma is not a disorder but a reaction to a kind of wound. It is a reaction to profoundly injurious events and situations in the real world and, indeed, to a world in which people are routinely wounded.

2003, p. 1302

Trauma and violence-informed strategies, therefore, require an intersectional analysis that is attentive to the context in which trauma and violence occur. At the same time, trauma and violence-informed approaches recognize that experiencing such harms can influence how a person understands their sense of self as well as their experiences within the broader context of social structures. Indigenous healing paradigms help revive culture, while Indigenous harm reduction is a process of integrating cultural knowledge and values into strategies and services to tackle the effects of colonialism (First Nations Health Authority, n.d., p. 1). For reasons of space, we note here but will not elaborate that some of our participants asked what supports are available for perpetrators in their healing. Some suggested having former perpetrators help with education and prevention. Thus, community outreach and programming may also be important strategies, including having men’s participation in healing and building community resilience based on traditional values and knowledges.

In sum, a critical anti-trafficking approach responds to violence in the sex trade through an emphasis on agency, self-determination, resilience, resistance, and the empowerment of trafficked persons and their communities. Combining participatory action research (PAR) with Indigenous and feminist methodologies enables us to emphasize these affirmative values.

Methodology

We draw on Indigenous, feminist, and participatory action research methodologies in the spirit of Two-Eyed Seeing, which is Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall’s term for “weaving together” (Bartlett et al., 2012, p. 335) Indigenous and mainstream knowledges in a manner that draws on the strengths of each “to the benefit of all” (Bartlett et al., 2012, p. 335; Peltier, 2018). We do so in order to advance “self-determined solutions” centred in our relationships with each other (NIMMIWG, 2019, p. 11). In Anishinaabe ontology, Cindy Peltier (2018) wrote , “relationships tie us to everything and everyone in both physical and spiritual realms” (p. 3). Indigenous ways of knowing and being are holistic: physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. Thus, an Indigenous research approach “flows from an Indigenous belief system that has at its core a relational understanding and accountability to the world,” including the non-human world (Kovach, 2010, p. 3). Research with, by, and for Indigenous peoples runs much deeper than “consultation” and is instead based on the Four R’s of Indigenous research, respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility, which are necessary for building good relationships and socially just practices (Kirkness & Barnhardt, 2001; Kovach, 2009).

These principles can inform PAR approaches, which, like Indigenous methodologies, emphasize collaboration and co-inquiry, drawing on multiple ways of knowing, and the involvement and empowerment of those most affected (Reason & Bradbury, 2008). PAR is oriented toward problem-solving, with iterative cycles of diagnosis (identifying the problem), planning (developing a research strategy to address the issue), action (implementing the research strategy, working for social change) and reflection (analysis, evaluation, and sharing; MacDonald, 2012).

The Indigenous principle of relevance starts in the diagnosis stage of research, where participants identify the problem, and the dynamic nature of PAR allows for continued flexibility to interests. Respect speaks to the development of relationships of trust and accountability with Indigenous participants, demonstrating respect for protocols, and the ethical sharing of stories. Responsibility speaks to the importance of making meaning together, of listening carefully, and of engaging in critical self-reflection with respect to power dynamics between researcher and participant, and not sharing cultural knowledge without permission. Reciprocity runs throughout the PAR cycle, with the sharing of results, feedback, and approval from participants, and deriving mutual benefits from the research (Peltier, 2018; Stanton, 2014).

The aim of PAR is to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in everyday life, and the use of visuals is one of the principles of Two-Eyed Seeing to make things accessible for oral peoples (Bartlett et al., 2012). Like Indigenous methodologies, PAR recognizes that the poor, the exploited, and the marginalized are experts in their own lives and helps them develop their own resources for resistance, activism, and self-reliance (MacDonald, 2012,). Additionally, feminist PAR approaches bring intersectionality and explicit critiques of power into the framework in order to elucidate and interrogate injustice and inequality (Evans et al., 2009; Reid et al., 2006). Feminist intersectionality looks at the ways in which gender, race, class, sexuality, ability, colonialism (and so forth), are “intertwined and mutually constitutive” in the “social and material realities” of people’s lives (Davis, 2008, p. 71).

We are mindful that feminism is “fraught” for some Indigenous women, even those actively organizing on women’s issues (Gehl 2017; Lew, 2017, fn. 4; Sunseri, 2011). Approaching feminism through an Indigenous lens necessitates an emphasis on the self-determination of Indigenous women and their communities, and the return of Indigenous life and land (Konsmo & Pacheco, 2016; Kuokkanen, 2012; Tuck & Yang, 2012). Furthermore, as Métis activist and academic Natalie Clark (2016) noted, Sioux activist Zitkala-Sa and other Indigenous feminists at the turn of the twentieth century were writing of the way “that violence has always been gendered, aged, and linked to access to land”(p. 49). Thus, she argued, “Indigenous ontology is inherently intersectional and complex in its challenging of the notions of time, age, space, and relationship” (Clark, 2016, p. 49). In the Service Mapping Toolkit, we particularly rely on feminist and Indigenous intersectionality to explain human trafficking as the product of the relationship between structures of violence and personal circumstances.

PAR Workshops and Findings

In the spring and fall of 2017, we held eight full-day PAR workshops in two large cities with over 100,000 in population (Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie), one medium city with a population of approximately 50,000 (North Bay), and five smaller communities with populations ranging from 200 to 8,000 (Little Current, Kirkland Lake, Cochrane, Parry Sound, and Dokis First Nation). Donna, the Elder on our team, felt quite strongly that this was not the time to go directly into First Nations communities to conduct research because of the potentially traumatizing nature of the topic. Thus, we decided to focus on service providers and persons with lived experience who, in keeping with principles of self-determination, felt they were at a sufficient stage in their healing to attend. Our team also decided to exclude child protection agencies and all police services in order to ensure a safer space,[8] and to honour that the Anishinabek Nation maintains its inherent right over the welfare and jurisdiction of its children.[9] We followed Indigenous protocols at the workshops, with Donna or a local Elder opening the day with a prayer and a smudge, having a prayer and spirit plate at lunch time, and closing the day with a sharing circle for reflection and debriefing (Wilson, 2008). We also had Elder and counselling support on hand, and shared Amelia Rising’s crisis support phone number in case support was needed afterward.

In total, we had 165 participants, with approximately 60 participants identifying as Indigenous and/or attending on behalf of Indigenous agencies. The types of agencies represented (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) included mental health and addictions support services, intimate partner violence support services, shelters and transitional housing services, correctional services, AIDS service organizations, Ministry of Community and Social Services, Victim Services, and health-care providers. Five participants had lived experience in human trafficking and/or the sex trade, either directly or as family members. The following discussion of findings is informed by our participant-observation notes, flip chart notes put together by participants in group discussions, and dot-mocracy results, where participants were given three sticky dots to place beside their preferred recommendations listed on the flip charts.[10]

Trafficked persons have a complex set of needs “due to the compounded nature of systemic and interpersonal violence that they experience” (Nagy et al., 2018a, p. 20). Some short-term needs, especially for people in crisis, included: sleep, safer shelter, food, hygiene, clothing, cigarettes, emergency medical care, detox or addiction management, and safety planning (Nagy et al., 2018a, p. 22). Our participants also identified longer-term needs that included: security from traffickers, transitional housing, affordable housing, mental health and addictions support, life skills and employment, health cards, tattoo removal, dental work, the return of children in care, and peer support. Participants emphasized the importance of having a trauma and violence-informed approach, where we seek to avoid retraumatizing people while supporting their pathways to healing. Having culturally relevant supports for francophone and Indigenous women is also crucial.

The experience of being trafficked is mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional; thus, holistic support is necessary. Indigenous participants mentioned the importance of Grandmothers, Aunties, Uncles, and Elders in the community; of knowing the Grandfather teachings; of breaking the cycle of intergenerational trauma; of nurturing the wellness of individual, family, and community, including connections to the natural cycle; and the idea that everyone has a role in community. Somewhat similarly, for non-Indigenous women, psychosocial care models that emphasize reintegration into the community “can be incredibly helpful for trafficked individuals due to the high degree of social isolation they experience” (Dyck, n.d., p. 33).

There are significant resource gaps in Northeastern Ontario, and this was the foremost theme of discussion at all workshops. Funding is a chronic challenge. We also heard multiple discussions about the lack of human trafficking data specific to our region that might help secure funding. Yet, some participants also worried that lower statistics could be used against Northeastern Ontario funding applications. In any case, gathering statistics is difficult given the nature of human trafficking. Despite recognition of the importance of collaboration, people also noted the tension that arises when we are all competing for the same pot of funding. Funding specific to human trafficking in the region during our 2017 workshops was mainly short-term funding through the provincial Victim Quick Response Program of Victim Services, and awareness campaigns through Crime Stoppers and Victim Services. However, as various people noted at different workshops, awareness campaigns without access to appropriate resources may be problematic, if not dangerous.

With regard to specific resources needed in Northeastern Ontario, there is a lack of transitional housing and a shortage of long-term safe and affordable housing. Participants further noted that homeless and domestic violence shelters have long waitlists and may be unsuitable for trafficked persons due to requirements for sobriety and/or verification of identity (traffickers may take identification cards). Moreover, participants indicated that shelters may serve as recruitment sites for trafficking because these insecure sites are known to traffickers, who can access and manipulate the vulnerabilities of residents. Research participants noted that northern-specific barriers to service provision include “huge geographical circumferences,” “remoteness and accessibility,” and the inadequacy of sending someone “down south” for services away from family and community supports. Thus, we heard multiple calls for the development of safer spaces and/or a dedicated safe house in the region for survivors of human trafficking. Other barriers to accessing services include institutionalized racism, the lack of culturally appropriate services, fear of arrest, and, in the case of some towns, the location of Victim Services in the police station. Smaller towns also face challenges such as the common knowledge of the shelter’s location. Finally, a major barrier in all communities is the shame and stigma associated with rape and with the sex trade more generally.

Participants spoke about the need for greater communication between agencies and service mapping.[11] As one participant pointed out, “We’re all working in silos here.” Another asked, “Why would someone want to disclose [that they’ve been trafficked]? We don’t have much to offer.” Another simply noted, “I don’t have enough resources to help her.” Some service providers said that they did not know where to refer people, and that trafficked persons themselves do not necessarily know where to go for help, particularly if they are not accessing services in the first place. Almost none of our participants had human trafficking specifically in their mandates and most were doing human trafficking “off the side of their desks.” This often meant that agencies are addressing human trafficking through existing programs such as “Healthy Relationships” programs and various forms of outreach. It is important to acknowledge that these approaches can be helpful where service providers are well-informed to do the best they can to support people who are being or have been trafficked.

For the most part, however, our conversations with service providers demonstrate the gross lack of resources and funding dedicated to human trafficking in this region. Stretching already thin resources puts a greater burden on service providers to perform double the work-load which, in turn, could have adverse effects on service providers’ own well-being and their capacity to provide services. Having a dedicated organization and safe house in the region for trafficked persons may be an ideal approach because of the complex nature of personal situations and the length of recovery from violence and trauma (Nagy et al., 2018a). However, financial realities such as lack of sustainable government funding mean this may not be possible, at least not in the short-term. That said, the presence of a dedicated organization or safe house does not preclude the need for collaboration and service mapping because the complex needs of survivors necessitate comprehensive supports that no single service can deliver.

Collaboration and the Service Mapping Toolkit

This final section presents the Service Mapping Toolkit designed to assist with developing multi-disciplinary collaboration and wrap-around support. The five graphics in this section are intended to be a handout for affected persons, agencies, and communities. Service mapping exercises will need to be repeated as organizations and personnel change. Thus, the service map should be understood as a living document, and the suggestions we provide are not exhaustive and can be adjusted for specific communities.

Page one of the Service Mapping Toolkit (Figure 1) uses an intersectional approach to illustrate the complex connections between structures of violence and personal experiences and circumstances. As the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) wrote, “Violence experienced by women who are sex workers, sexually exploited, and/or trafficked is not separate from colonial violence, but a central part of it” (Roudometkina & Wakeford, 2019, p. 4; Collin-Vezina et al., 2009; Macdonald & Wilson, 2013; NWAC, 2014). While we cannot elaborate on all details in the graphic, the deeply gendered nature of colonial dispossession is foundational to understanding sexualized violence against Indigenous women and girls. Indigenous women have historically been positioned as less than human, sexually available, and therefore, inherently violable (Boyer & Kampouris, 2014; Kaye, 2017; Smith, 2005). Socioeconomic marginalization resulting from the imposition of heteropatriarchal governance structures, the “marrying out” clause, and the lack of housing and other basic survival needs render Indigenous women all the more vulnerable to sexual violence and exploitation.

Particularly in northern and remote communities, “the lack of infrastructure and services … feeds the sex industry and further exploitation,” or drives women south where they are more vulnerable to being trafficked (NIMMIWG, 2019, p. 661). Land dispossession is therefore a key structural factor, including as it relates to a reliance on hitchhiking (NWAC, 2014). There is also documentation of an increase in human trafficking and other forms of violence at resource extraction sites (Konsmo & Pachecho, 2016). Finally, we note the intergenerational effects of residential schools, most especially cycles of abuse and neglect, mental health and addictions, and the normalization of violence, all of which factor into vulnerability. Given the variability of intersections between colonial structures and personal experiences and circumstances, Page one (Figure 1) of the service map allows us to see the ways in which the experience of trafficking and/or abuse is unique to each person, family, and community, and therefore requires individually tailored supports.

Figure 1

Personal & Structural Dimensions of Human Trafficking

Note. Illustration of the complex connections between the structures of violence and personal experiences and circumstances

Page two (Figure 2) of the Service Mapping Toolkit speaks to the effects of human trafficking and core values, behaviours, and structures needed to respond to the issue. Modeled after the medicine wheel, it points to the physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and social harms of trafficking. These pertain not only to the trafficked individual, but also to their family, community, nation, and society. These larger groups may be both implicated in trafficking and/or harmed by it. Thus, the core values required in responding to human trafficking apply not only to service providers but also to these larger groups. For example, elevating the positive value of self-determination over the negative value of control and dispossession speaks to the loss of control experienced at the hands of a trafficker, as well as the dispossession of Indigenous bodies, communities, and land (Konsmo & Pacheco, 2016). For service providers more specifically, valuing self-determination means ensuring that support services do not mimic or reiterate the controlling behaviours of traffickers or presume to know what is best for clients. Similarly, prizing resistance and resilience above passive or pathological victimhood is important in the production of awareness campaigns, media representations, and in recognizing that trafficked women negotiate survival on a daily basis. This is in contrast to misconceptions about women’s perceived lack of agency that justifies coercive interventions and infantilizing approaches (Cojocaru, 2016). As the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform (2017) wrote:

It is of utmost importance that women experiencing violence or exploitation are able to come forward and report when and if they choose, but this decision should be made by the individual, not determined by an intervention from an outside source.

p. 6

Figure 2

Effects of Human Trafficking: Core Values for Responding

For service providers, acceptance and non-judgment are crucial to building trust with clients. Furthermore, our research shows that stigmatization is a key barrier to families and individuals seeking help. Moralizing approaches are ineffective. Moreover, reducing the stigmatization of sex work enhances the security of everyone in the sex trade and helps reduce the underground conditions that facilitate violence and trafficking. De-stigmatization may also facilitate acceptance by communities and families, and we argue that the rebuilding of healthy relationships is integral. The term families, here, embraces a wider circle of belonging beyond immediate family, and might also mean chosen family, that is, persons who are not biologically related. The final two sets of core values emphasize the equality and dignity of people, as well as responsibilities and accountability at the level of community, Nation, and society (Konsmo & Pacheco, 2016). The marginalization and social exclusion that come with poverty, racism, sexism, and other forms of systemic oppression requires not only attitudinal changes at the interpersonal level (such as from apathy, indifference, or bias) but also structural changes in terms of law, policies, and the distribution of resources.

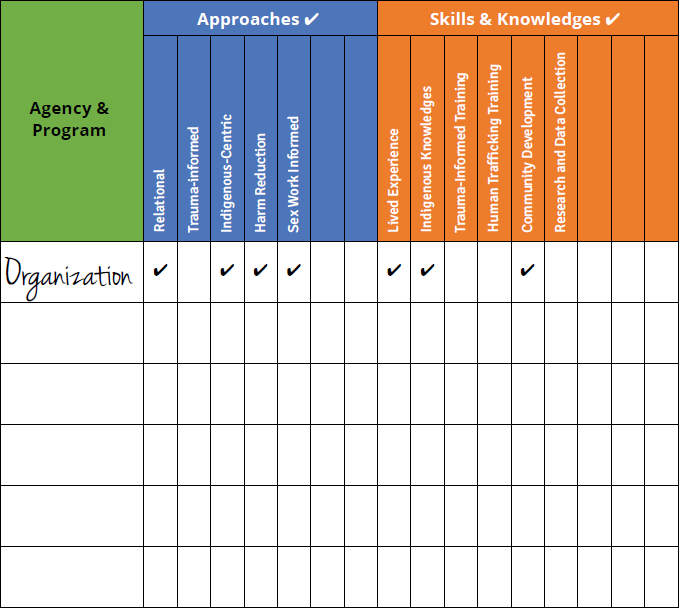

Page three (Figure 3) of the toolkit is the start of the service mapping process itself and is applicable within organizations, across communities, and regionally. Page three is intended to help service providers assess the strengths and limitations of their policies and practices in order to map out existing support systems. It is designed for each organization or agency to conduct a reflective self-assessment in terms of their approaches, knowledges, and programs, including in ways that are not specifically categorized as anti-human-trafficking strategies. We argue that it is vitally important for service providers to continually assess their strategies and policies as well as to evaluate their personal biases and privileges. We want to emphasize that these three categories, approaches, knowledges, and programs, must be integrated together. It is insufficient to simply check off specific programs which may in fact be inappropriate for women seeking support if programs do not embody specific approaches or incorporate appropriate knowledges.

In terms of approaches, we argue for relational approaches that are tailored to the specific needs of trafficked persons, their families, and community. By relational, we mean service provider approaches that honour self-determination and agency, are based in respect and non-judgement, and encourage service providers to act as allies in achieving change, rather than imposing “expert” solutions (Folgheraiter & Luisa, 2017). Building this kind of relationship with trafficked persons is necessary if support strategies are to have any meaningful impact. We highlight here the need for trauma and violence-informed practices that prioritize the safety and needs of those who are accessing support and aim to avoid causing further harm to persons. As previously mentioned, trauma and violence-informed strategies require an intersectional analysis of the complexities of trauma and violence in order to understand how people are affected by harmful experiences. This is important in terms of addressing human trafficking because practices that are not trauma and violence-informed can unintentionally retraumatize persons who are accessing support.

Figure 3

Organizational profile

As discussed previously in relation to self-determination, any act that attempts to control persons or deny their right to make choices for themselves may be perceived as being similar to traffickers’ methods of control. Thus, for example, policies that require people to consistently attend certain types of programming in order to qualify for other supports may, in fact, be counterintuitive to trauma and violence-informed practices. Honouring self-determination further requires a sex work informed approach to human trafficking. The violence and harm experienced by sex workers in the name of anti-trafficking is well documented: surveillance, harassment, intimidation, criminalization, deportation, and the denial of sex workers’ agency and self-determination (Kempadoo & McFadyen, 2017). Sex workers should not be the collateral damage (The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women, 2007) of anti-trafficking. Furthermore, we believe that sex workers can and should be at the forefront of detecting and responding to human trafficking. Thus, they must be consulted in a meaningful manner in the design of anti-human trafficking measures.

Harm reduction strategies are central to trauma and violence-informed practices. Both approaches move beyond framing trauma as the result of isolated events to understanding that trauma impacts the person as a whole, while simultaneously recognizing that people are more than their trauma. As one member of NORAHT described, harm reduction means meeting people where they are in their journey at that particular moment. Thus, it is important to acknowledge that healing is not a linear process and that people may require different supports at various moments throughout their healing. Harm reduction strategies will vary across sectors and there is no singular definition of what constitutes harm reduction. Some common principles include: respecting human rights and dignity; a commitment to social justice and social transformation; reducing stigma; and minimizing negative health impacts (Harm Reduction International, 2019)

We also argue for decolonizing trauma-informed approaches because healing strategies rooted in Eurocentric paradigms may be insufficient to meet the needs of trafficked persons. This is particularly important in our region given that Indigenous women are likely to be disproportionately trafficked, and our findings indicate a need for Indigenous-centric approaches. Decolonizing trauma scholarship is critical of the ways in which practices rooted in Eurocentric paradigms pathologize individuals by focusing on what is “wrong” with the person and the ways in which personal experience is addressed in isolation (Baskin, 2016; Duran, 2005; Linklater, 2014). In contrast, decolonizing trauma approaches focus on the harms experienced and create space for culturally relevant healing practices that may differ from Eurocentric, biomedical, and psychological paradigms. Following Renee Linklater (2014; Rainy River First Nation), we argue that understanding the concept of resiliency is integral to decolonizing trauma practices. She wrote, “Resiliency focuses on the strengths of Indigenous peoples and their cultures, providing a needed alternative to the focus on pathology, dysfunction and victimization” (Linklater, 2014, p. 25). Decolonizing trauma practices have much in common with Indigenous healing paradigms, such as an emphasis that individual healing is “grounded in social healing” (Ross, 2014, p. 37), and an emphasis on holistic healing. Moreover, decolonizing approaches not only recognize the harms of settler colonialism but systematically work toward repair and redressing such harms. For example, this could mean working toward the implementation of the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015) and the National Inquiry on MMIWG2S (2019).

Figure 4

Integrating Approaches, Skills/Knowledges, and Programs in Your Community or Area

The obvious overlaps in the above approaches identified here include a rejection of Eurocentric knowledges centred on individualism. Instead, a positioning of individuals in their relationships to families and communities allows for envisioning their physical, mental, psychological, spiritual, and social well-being, not in isolation but in an enabling structural environment where coalitions of service providers are well-resourced and equipped with the present toolkit. This toolkit not only touches upon relevant knowledges and necessary programs, but also highlights especially the importance of experiential and Indigenous knowledges, and the importance of having culturally sensitive trauma and violence-informed training. Programming priorities include having a dedicated case worker, Indigenous healing and wellness, mental health and addictions, peer outreach and support, and safe shelter and affordable housing. Our francophone participants also highlighted having French programming and services as culturally important, and that it is difficult for francophone clients to translate traumatic emotions into English. We further note the importance of supports for “aging out” youth and helping trafficked women get their children back.

Figure 5

Human Trafficking Collaborative Service Map

Note. A chart to help determine what approaches, skills, and knowledges are present in your community organizations and programs

Pages four (Figure 4) and five (Figure 5) of the Service Mapping Toolkit are designed for community or area-wide collaboration to see what strengths and gaps collectively exist. One of the things we observed at our workshops was that some participants simply did not know what other agencies provide or the kinds of resources that are available. If mainstream agencies are organizing the collaborative network, it is especially important to reach out to local First Nations, Friendship Centres, other Indigenous groups, and especially Elders, for inclusivity and perspective. Personal invitations to join a meeting—phone calls or community presentations, rather than random emails—are key to starting relationships if none exist.

Flexible support, available 24 hours/7 days a week, is key for meeting people where they are, rather than trying to fit them into mandates defined by contractual obligations with funders (Nagy et al., 2018a). Having a dedicated case worker and/or liaison person for the collaborative network is very important because it saves women from repeatedly telling their story (which can re-traumatize) and it ensures the smooth coordination of services. Case management is crucial, where a walk with me approach means we do not simply facilitate making appointments but also accompany clients for added security and support. We also cannot overemphasize the importance of listening to and meaningfully involving people with lived experience, as well as compensating them for their time, expertise, and support in the circle of care. Trafficking survivor and research participant Leona Skye suggested that member organizations pay into a collective pot as a promise to help employ a peer survivor. This would create job positions and also ensure that member organizations will use the services of the peer survivor because it is part of their budgets. Finally, responding to human trafficking requires a long-term commitment and core, long-term funding. Participants reported that it may take multiple attempts and several years to exit an abusive situation and that the recovery process may be long and complex. As one key informant indicated, “If you can’t commit the time, then don’t get engaged at the outset” (Nagy et al., 2018a, p. 21).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have identified gaps and barriers to service provision and the particular circumstances of responding to human trafficking in Northeastern Ontario. Comprehensive, wrap-around support is necessary to address short-term and long-term needs of people being trafficked, trafficking survivors, their families, and communities. We recommend the development of safe houses dedicated to women experiencing human trafficking in Northeastern Ontario. We further highlight the pronounced need in our region for transitional housing and long-term safe and affordable housing, both of which were identified by our participants as one of the key gaps in responding to human trafficking and other forms of abuse in the sex trade. We recommend, also, that provincial and federal funding opportunities be accessible to grassroots organizations that are doing outreach, because they are often most directly connected to persons in the sex trade and, thus, most likely to be in a position to provide support. While the communities in our region are working toward dedicated safe houses, it is recommended that safe spaces be created within existing organizations and that staff be trained to understand the unique needs of persons seeking anti-violence supports using the approaches and knowledges we have identified. Collaboration among grassroots organizations, service providers, and experiential persons is key to addressing human trafficking and violence in the sex trade, including in the sharing and coordination of information, knowledges, and resources.

To that point, we summarize below seven main principles for building collaborative networks or coalitions aimed at comprehensively responding to human trafficking and violence in the sex trade:

Focus on supporting those who have experienced harms and violence and ask for help. Don’t assume to know better than trafficked persons what their unique needs are at any given tim.

Involve persons with lived experiences in the paid circle of care. This includes in the design, management, and evaluation of programs, as well as community outreach and peer support.

Employ non-judgmental, trauma and violence-informed approaches, and harm reduction.

Provide culturally relevant supports that draw on appropriate knowledges.

Maintain open communication and common referral protocols, and the tracking of data within the collaborative network.

Commit to providing 24/7, flexible, and individually tailored support for several years for each trafficked person.

Provide support that is relational and holistic. Building healthy relationships within families, communities, and between service providers and trafficked persons is key to support and healing.

At the core of these principles is the importance of supporting trafficked persons in ways that uphold self-determination and human dignity. Importantly, we emphasize that trafficked persons must be able to choose their own pathways to healing, with service providers delivering support and tools. Local and regional collaboration based on these principles serves to redress some of the gaps and barriers, to streamline and coordinate responses, and to develop and provide more comprehensive supports that empower and respect the self-determination of trafficked persons, their families, and communities.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Our work is supported by a Partnership Development Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We thank our undergraduate research assistants, Megan Stevens, Jylelle Carpenter-Boesch, and Sydnee Wiggins, and social work placement students at Amelia Rising, Nadine Holst and Melissa Hancocks, who have contributed to this project over the years. We also thank Dr. Serena Kataoka for her invaluable contributions in the early stages of our formation as well as during our first workshop. Kinanâskomitin to Eva Dabutch of Missanabie Cree First Nation and chi miigwetch to survivor-champion Leona Skye for their suggestions. Finally, we thank our anonymous reviewers for their extensive and constructive suggestions.

-

[2]

We decided early on that child sexual exploitation was beyond our scope and focused on women 18 years of age and older. However, research participants repeatedly noted that girls in care aged 16–18 are especially vulnerable to trafficking as they “age out” of the system. Participants with lived experience further emphasized the need to respect the agency and self-determination of youth in the sex trade.

-

[3]

We disagree with radical feminist arguments that prostitution and human trafficking are simply forms of sexualized male domination (Barry, 1981; O’Connor & Healy, 2006). We reject this essentialist argument because it treats women as inherent victims and men as inherent perpetrators. It provides little explanation for the trafficking of men, boys, and transgender persons. In seeking to abolish prostitution, it denies the agency and safety of sex workers. Finally, it neglects the intersectional factors, such as colonialism and poverty, that contribute to human trafficking.

-

[4]

We use “sex work” in reference to an explicit position that identifies an occupation whose workers are entitled to make a living and human rights. However, not everyone in the sex trade will identify as “workers.” Thus, we use “sex trade” to refer to commercial and survival sex that may be forced, voluntary, or anywhere in between (Young Women’s Empowerment Project, 2009).

-

[5]

See Leona Skye, Tammi Givans, and Wendy Sturgeon, “Let’s Talk...About Surviving Today”, Niagara Chapter Native Women, Inc., Final Report, Phase 1, March/April 2018. Skye further adds that peer survivor support could include not only survivors of human trafficking but also survivors of childhood sexual trauma, domestic violence, and so forth.

-

[6]

This phrase comes from the disability rights movement.

-

[7]

Following the Public Health Agency of Canada (2018), we use the term “trauma and violence-informed” approaches to acknowledge that trauma and violence are connected. However, we condense to “trauma-informed” on the toolkit graphics for reasons of space.

-

[8]

Our group has had some debate over whether to use “safe” or “safer”, since it is not possible to create fully safe spaces.

-

[9]

However, in the three follow-up conferences we held in 2018, we invited police services because many participants said they should be at the table. We recognize that police services and child protection agencies will be part of any local collaborations on human trafficking, but that a law enforcement approach alone is inadequate and potentially harmful.

-

[10]

For a full discussion of findings and analysis across the region and within each location, see our full report (Nagy et al., 2018b). The call for collaboration was the second priority after a call for education for the general public, the hospitality industry, parents, school children, and training for service providers.

-

[11]

Participants in our northernmost locations said service mapping is not a useful exercise due to the extremely limited number of services available in their communities.

Bibliography

- Baker, C. N. (2014). An intersectional analysis of sex trafficking films. Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, 12(1), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.2979/meridians.12.1.208

- Barry, K. (1981). Female sexual slavery: Understanding the international dimensions of women’s oppression. Human Rights Quarterly, 3(2), 44–52.

- Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

- Baskin, C. (2016). Strong helpers’ teachings: The value of Indigenous knowledges in the helping professions. Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

- Boyer, Y., & Kampouris, P. (2014). Trafficking of Aboriginal women and girls. Public Safety, Canada. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/sp-ps/PS18-8-2014-eng.pdf

- Burstow, B. (2003). Toward a radical understanding of trauma and trauma work. Violence Against Women, 9(11), 1293–1317. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077801203255555

- Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform. (2017). Safety, equality and dignity: Recommendations for sex work law reform in Canada. Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform. http://sexworklawreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/CASWLR-Final-Report-1.6MB.pdf

- Canadian Women’s Federation. (2014). “No more” ending sex-trafficking in Canada.Report of the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada. Canadian Women’s Foundation.

- Clark, N. (2016). Red intersectionality and violence-informed witnessing praxis with Indigenous girls. Girlhood Studies, 9(2), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2016.090205

- Cojocaru, C. (2016). My experience is mine to tell: Challenging the abolitionist victimhood framework. Anti-Trafficking Review, 7, 12–38. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121772

- Collin-Vezina, D., Dion, J., & Trocme, N. (2009). Sexual abuse in Aboriginal communities: A broad review of conflicting evidence. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal & Indigenous Community Health, 7(10), 27–47.

- Criminal Code of Canada. RSC, C-36.

- Dandurand, Y. (2017). Human trafficking and police governance. Police Practice and Research, 18(3), 322–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2017.1291599

- Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1464700108086364

- Doezema, J. (2002). Who gets to choose? Coercion, consent, and the UN Trafficking Protocol. Gender and Development, 10(1), 20–27.

- Duran, E. (2006). Healing the soul wound: Counseling with American Indians and other Native people. Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

- Dyck, J. (n.d.). Addressing the trafficking of children & youth for sexual exploitation in BC: A toolkit for service providers. Children of the Street Society http://www.childrenofthestreet.com/serviceproviders

- Evans, M., Hole, R., Berg, L., Hutchinson, P., & Sookraj, D. (2009). Common insights, differing methodologies: Toward a fusion of Indigenous methodologies, participatory action research, and white studies in an urban Aboriginal research agenda. Qualitative Inquiry, 15(5), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800409333392

- First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.) Fact sheet: Indigenous harm reduction principles and practices. First Nations Health Authority. https://www.fnha.ca/WellnessSite/WellnessDocuments/FNHA-Indigenous-Harm-Reduction-Principles-and-Practices-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- Folgheraiter, F., & Luisa, R. M. (2017). The principles and key ideas of relational social work. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 12–18.

- Gehl, L. (2017). Claiming Anishinaabe. University of Regina Press.

- Harm Reduction International. (2019). What is harm reduction? Harm Reduction International. https://www.hri.global/what-is-harm-reduction

- Hunt, S. (2010). Colonial roots, contemporary risk factors: A cautionary exploration of the domestic trafficking of Aboriginal women and girls in British Columbia, Canada. Alliance News, 33, 27–31.

- Kaye, J. (2017). Responding to human trafficking: Dispossession, colonial violence, and resistance among Indigenous and racialized women. University of Toronto Press.

- Kaye, J., Winterdyk, J., & Quarterman, L. (2014). Beyond criminal justice: A case study of responding to human trafficking in Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 56(1), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2012.E33

- Kempadoo, K. (2015). The modern-day white (wo)man’s burden: Trends in anti-trafficking and anti-slavery campaigns. Journal of Human Trafficking, 1(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2015.1006120

- Kempadoo, K., & McFadyen, N. (2017). Challenging trafficking in Canada: Policy brief. Centre for Feminist Research, York University. https://cfr.info.yorku.ca/files/2017/06/Challenging-Trafficking-in-Canada-Policy-Brief-2017.pdf?x97982

- Kirkness, V. J., & Barnhardt, R. (2001). First Nations and higher education: The four R’s–respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. In R. Hayhoe, & J. Pan (Eds.), Knowledge across cultures: A contribution to dialogue among civilizations. Comparative Education Research Centre.

- Konsmo, E. M., & Pacheco, A. M. K. (2016). Violence on the land, violence on our bodies: Building an Indigenous response to environmental violence. Women’s Earth Alliance, & Native Youth Sexual Health Network. http://landbodydefense.org/uploads/files/VLVBReportToolkit2016.pdf

- Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

- Kovach, M. (2010). Conversational Method in Indigenous Research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 40–48.

- Kuokkanen, R. (2012). Self-determination and Indigenous women’s rights at the intersection of international human rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 34(1), 225–250. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2012.0000

- Lew, J. (2017). A politics of meeting: Reading intersectional Indigenous feminist praxis in Lee Maracle’s Sojourners and Sundogs. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 38(1), 225–259. https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.38.1.0225

- Linklater, R. (2014). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Fernwood Publishing.

- MacDonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13(2), 34–50.

- Macdonald, D., & Wilson, D. (2013). Poverty of prosperity: Indigenous children in Canada. Center for Policy Alternatives. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/poverty-or-prosperity

- Maynard, R. (2015). Fighting wrongs with wrongs? How Canadian anti-trafficking crusades have failed sex workers, migrants, and Indigenous communities. Atlantis, 37(2), 17.

- Nagy, R., Snooks, G., Jodouin, K., Quenneville, B., Stevens, M., Chen, L., Debassige, D., & Timms, R. (2018a). Community service providers and human trafficking: Best practices and recommendations for Northeastern Ontario. Northeastern Ontario Research Alliance on Human Trafficking [NORAHT]. https://noraht.nipissingu.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/70/2018/06/Best-Practices-NORAHT-Report-June-2018.pdf

- Nagy, R., Snooks, Carpenter-Boesch, J., Jodouin, K., Quenneville, B., Debassige, D., Timms, R. & Chen, L. (2018b). Human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation in Northeastern Ontario: Service provider and survivor needs and perspectives. NORAHT. https://noraht.nipissingu.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/70/2019/10/NORAHT_-Human-Trafficking-for-the-Purpose-of-Sexual-Exploitation-in-Northeastern-Ontario-Report.pdf

- National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls [NIMMIWG]. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. NIMMIWG. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/

- Native Women’s Association of Canada [NWAC]. (2014). Sexual exploitation and trafficking of Aboriginal women and girls: Literature review and key informant interview. NWAC, & Canadian Women’s Foundation Task Force on Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada. https://www.nwac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2014_NWAC_Human_Trafficking_and_Sexual_Exploitation_Report.pdf

- Norfolk, A., & Hallgrimsdottir, H. (2019). Sex trafficking at the border: An exploration of anti-trafficking efforts in the Pacific Northwest. Social Sciences, 8(155), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8050155

- O’Connor, M., & Healy, G. (2006). The links between prostitution and sex trafficking: A briefing handbook. Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, & European Women’s Lobby. https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/publications/links-between-prostitution-and-sex-trafficking-briefing-handbook_en

- Ontario Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation. (2018). Indigenous people in Ontario. https://www.ontario.ca/document/spirit-reconciliation-ministry-indigenous-relations-and-reconciliation-first-10-years/indigenous-peoples-ontario.

- Oxman-Martinez, J., Hanley, J., & Gomez, F. (2005). Canadian policy on human trafficking: A four-year analysis. International Migration, 43(4), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00331.x

- Perry, M. (2018). The tip of the iceberg: Human trafficking, borders and the Canada-U.S. North. Canada-United States Law Journal, 42, 204–226.

- Peltier, C. (2018). An application of Two-Eyed Seeing: Indigenous research methods with participatory action research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1609406918812346

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2018). Trauma and violence-informed approaches to policy and practice. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/trauma-violence-informed-approaches-policy-practice.html.

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police. (2013). Domestic human trafficking for sexual exploitation in Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2008). Introduction. In P. Reason, & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of action research (2nd edition; pp. 1–11). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Reid, C., Tom, A., & Frisby, W. (2006). Finding the ‘action’ in feminist participatory action research. Action Research, 4(3), 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1476750306066804

- Roots, K. (2013). Trafficking or pimping? An analysis of Canada’s human trafficking legislation and its implications. Canadian Journal of Law and Society/Revue Canadienne Droit et Société, 28(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/cls.2012.4

- Roudometkina, A., & Wakeford, K. (2018). Trafficking of Indigenous women and girls in Canada: Submission to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. NWAC. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/JUST/Brief/BR10002955/br-external/NativeWomensAssociationOfCanada-e.pdf.

- Ross, R. (2014). Indigenous healing: Exploring traditional paths. Penguin Group.

- Sethi, A. (2007). Domestic sex trafficking of Aboriginal girls in Canada: Issues and implications. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(3), 57–71.

- de Shalit, A., & Van der Meulen, E. (2015). Critical perspectives on Canadian anti-trafficking discourse and policy. Atlantis, 37(2), 6.

- Sikka, A. (2009). Trafficking of Aboriginal women and girls in Canada. Institute on Governance. https://iog.ca/docs/May-2009_trafficking_of_aboriginal_women-1.pdf

- Smith, A. (2005). Conquest: Sexual violence and American Indian genocide. South End Press.

- Stanton, C. (2014). Crossing methodological borders: Decolonizing community-based participatory research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(5), 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077800413505541

- Sunseri, L. (2011). Being again of one mind: Oneida women and the struggle for decolonization. UBC Press.

- Sweet, V. (2015). Rising waters, rising threats: The human trafficking of Indigenous women in the circumpolar region of the United States and Canada. The Yearbook of Polar Law, 6, 162–188.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Vols. 1–6). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://nctr.ca/reports.php

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

- Young Women’s Empowerment Project. (2009). Girls do what they have to do to survive: Illuminating methods used by girls in the sex trade and street economy to fight back and heal. Young Women’s Empowerment Project. https://ywepchicago.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/girls-do-what-they-have-to-do-to-survive-a-study-of-resilience-and-resistance.pdf

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Personal & Structural Dimensions of Human Trafficking

Figure 2

Effects of Human Trafficking: Core Values for Responding

Figure 3

Organizational profile

Figure 4

Integrating Approaches, Skills/Knowledges, and Programs in Your Community or Area

Figure 5

Human Trafficking Collaborative Service Map

10.7202/1069397ar

10.7202/1069397ar