Résumés

Abstract

This paper addresses the issue of difference in the depth of visual memory among the Chukotka (Siberian) and St. Lawrence Island Yupik people based on several projects in heritage documentation between 1999 and 2019. Using historical photographs from museum collections and assessing how well (and how fully) Yupik Elders are able to recognize individuals and local details in various sets of historical photos roughly between 1895 and 1970, we may tentatively estimate the depth of “visual memory” and the ways it is changing. It generally fluctuates between 50 and 80–90 years due to various factors, and to the availability and memory of outstanding experts. Based on sets of historical photographs from the late 1800s, 1901, 1912, 1929, 1939, and 1967, the depth of visual memory was found to be significantly longer on St. Lawrence Island than in Chukotka Yupik communities.

Keywords:

- Chukotka/Siberian, St. Lawrence Island Yupik,

- historical photographs,

- visual memory depth,

- community heritage

Résumé

L’article aborde la question de la différence de profondeur de la mémoire visuelle chez les Yupik de Tchoukotka (Sibérie) et de l’île Saint-Laurent à partir de plusieurs projets de documentation du patrimoine entre 1999 et 2019. En utilisant des photographies historiques issues de collections muséales et en évaluant dans quelle mesure les aînés yupik peuvent reconnaître des individus et des détails locaux dans divers ensembles de photos historiques datant approximativement de 1895 à 1970, nous pouvons provisoirement estimer la profondeur de la « mémoire visuelle » et la façon dont elle évolue. Elle fluctue généralement entre 50 et 80-90 ans, en raison de divers facteurs abordés dans l’article, mais aussi de la disponibilité et de la mémoire d’experts exceptionnels. En se basant sur les séries de photographies historiques de la fin des années 1800, 1901, 1912, 1929, 1939 et 1967, nous avons constaté que la profondeur de la mémoire visuelle était beaucoup plus longue sur l’île du Saint-Laurent que dans les communautés yupik de Tchoukotka.

Mots-clés:

- Yupik de Tchoukotka/Sibérie et de l’île Saint-Laurent,

- photographies historiques,

- profondeur de la mémoire visuelle,

- patrimoine communautaire

Аннотация

Данная статья посвящена разнице в глубине визуальной памяти у эскимосов-юпик Чукотки (азиатских эскимосов) и острова Святого Лаврентия. Статья основана на нескольких проектах по документированию культурного наследия, выполненных в период с 1999 по 2019 гг. Используя исторические фотографии из музейных коллекций и оценивая насколько хорошо (и насколько полно) эскимосские старейшины способны идентифицировать людей и местные детали по сериям исторических фотографий, снятых примерно между 1895 и 1970 годами, мы можем предварительно оценить глубину «визуальной памяти» и ее динамику. Эта глубина обычно колеблется между 50 и 80–90 годами. Глубина визуальной памяти зависит от различных факторов, а также сохранения отдельных выдающихся экспертов среди старейшин и их более глубокой памяти. На основании демонстрации серий исторических фотографий конца XIX века, 1901, 1912, 1929, 1939 и 1967 годов можно прийти к выводу, что глубина визуальной памяти на острове Святого Лаврентия значительно длиннее, чем у эскимосов Чукотки.

Ключевые слова:

- Эскимосы-юпик Чукотки, эскимосы острова Святого Лаврентия,

- исторические фотографии,

- глубина визуальной памяти,

- локальное наследие

Corps de l’article

Dedicated to Willis Walunga (Kepelgu), 1925–2017,

Yupik historian, partner, and friend, with whom we shared a passion for Yupik genealogies, old names, and historical photographs

This paper describes a particular story within the general trend to open photographic and, broadly, museum/archival collections to Indigenous communities, which is now common across the Arctic (Buijs and Jakobsen 2011; Crowell 2020; Engelstad Driscoll 2018; Griebel, Keith, and Gross 2021; Hennessy et al. 2013; Keith et al. 2019; Kendall, Mathé, and Miller 1997; King and Lidchi 1998; Loring 1997; Smith 2008) and elsewhere (Bell, Christen, and Turin 2013; Christen 2011, 2019; Herle, Philp, and Dudding 2015; Lydon 2010, 2016; Peers and Brown 2003). It uses the experience of several projects in visual heritage documentation from the 1990s to 2019 conducted jointly with Yupik (formerly “Siberian Eskimo”) partners in Chukotka and on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. These two Yupik communities are culturally very close (Hughes 1984; Krupnik and Chlenov 2013) and have a shared history. Yet as their sociopolitical paths diverged in the twentieth century, so did the status of Yupik cultural and language preservation and—as this paper argues—also the depth of historical visual memory.

My research partnerships, first with the Chukotka Yupik (from the 1970s to mid-1990s, jointly with Michael Chlenov) and, later, on St. Lawrence Island (since the late 1990s onward) always included various forms of oral and written documentation: Elders’ interviews, genealogies, archival documents, historical maps, but few historical photos prior to the late 1990s, even if it generated a large body of contemporary photography from the 1970s and 1980s, including photographs taken by my colleagues Nikolai Vakhtin and Liudmila Bogoslovskaia and her partners[1] (see Acknowledgments). Among some 115 historical photographs and drawings used as illustrations in the summary of that study (Krupnik and Chlenov 2013), most of the images were added after 1995, when our fieldwork among the Chukotka Yupik was already completed.

The second, post-1995 work with the St. Lawrence Island Yupik and, by extension, with their kins in Chukotka, introduced me to a vast body of historical photography from the region. Conducted out of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), it unveiled the power and the value of historical photographs for research and for Yupik themselves. Indeed, the string of heritage documentation efforts since the 1990s helped uncover over 1,000 historical photos of Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island Yupik stored in museum collections in North America, Europe, and Russia.[2] This number keeps growing and the total volume of historical (pre-1970) Yupik photography should be substantially higher. The following descriptions illuminate what we learned together with Yupik collaborators—in steps, intuitively, and often by trial and error.

Setting the Bar—Akuzilleput Igaqullghet: Moore 1912

My first entrée in Yupik historical photography occurred during the three-year effort called the Beringian (Siberian–St. Lawrence Island) Yupik Heritage Project (1999–2001), motivated by the desire to open the richness of heritage resources, both published and archival, to local communities. Our team included more than 20 Elders from St. Lawrence Island, who acted as consultants, narrators, and knowledge experts.[3] The Project produced two volumes of Yupik narratives and historical documents: Akuzilleput Igaqullghet. Our Words Put to Paper (2002) and Let Our Elders Speak. Oral Stories of the Siberian Yupik Eskimo, 1975-1987 (Pust’ Govoriat 2000, in Russian), in addition to a range of retrieved archival materials, such as community lists, early censuses, genealogies, and village plans.

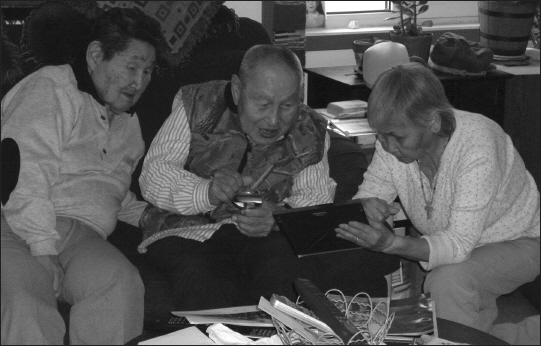

Lars Krutak, one of the team members, introduced to the project copies of historical photographs from St. Lawrence Island housed in the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) at the Smithsonian. These pictures were taken by Riley Moore (1887–?), Henry B. Collins (1899–1987), Otto Geist (1888–1963), and other visitors to the island in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Prints and photocopies of these images were brought to the island in 1999–2002 or mailed to Willis Walunga, our prime partner and esteemed Yupik heritage expert in Gambell, who led a local effort in photographic and oral history documentation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1

Willis Walunga (left), Conrad Oozeva, and Nancy Walunga in Gambell looking over old photographs

The growing stock of images from the NAA collections, but mainly the Elders’ irresistible quest for more historical pictures, made the value of early visual materials abundantly clear. Few island families had any photographs in their possession dating back to the 1940s, even 1950s, although some local youth, such as Clarence Irgoo (1914–2011) and Elvin Oovi (1922–1943), started taking pictures locally with their personal cameras in the late 1920s and 1930s.[4] Many people never saw images of their grandparents or parents as young adults, even children, thus historical photos served as an emotional “magnet” and a link to their past. They generated a much stronger emotional response than did texts or other old documents: people openly spoke of how they cried or felt deeply moved when viewing pictures of their family members from the past.

Among the most precious components of St. Lawrence Yupik historical photography at NAA was the set of 70+ large-size portraits and pictures of village scenes taken by Riley D. Moore in 1912. A young medical doctor, Moore spent four months on the island in the summer-fall of 1912, taking people’s facial and body measurements and photos for anthropometric records. He also gathered general ethnographic data on the island’s history, people’s health, and social life (Moore 1923), in addition to some 500 ethnographic objects obtained for museum collections.

Most of Moore’s portrait photographs followed the standard photographic procedure of the time and were rather simple, with a person poised in a wooden chair or standing upright in front of the camera.[5] He also took more personal and spontaneous scenes of village life. A few were used as illustrations in his article on St. Lawrence Island ethnography (Moore 1923), while stiff portrait photos were deposited at the Smithsonian. They remained at NAA,[6] were rarely viewed, and went unpublished for almost 90 years. In 1999–2000, prints of some 70 of Moore’s photos, including 51 portraits, were mailed to Gambell, Nome, and Savoonga, where Walunga, Vera Metcalf, and Angela Larson engaged local Elders in an emotional process of facial identification.

Thirty-six people were successfully recognized through this process; the names of other individuals, however, could not be established. Some people featured in Moore’s pictures evidently had passed away shortly after his visit in 1912; hence the Elders born after that date could have little or no visual knowledge of them, nor was there any matching photography from the same years to guide us. Fortunately, the names of several individuals captured in Moore’s photos were retrieved by checking the numbers on the negatives and photos against Moore’s “bodily measurement” forms, so that eventually we identified 48 people in Moore’s photo set. This enabled many families to “extend” the visual memory of their deceased relatives almost 90 years into the past. Yet a significant number of faces on Moore’s pictures remained unknown, and despite the best efforts of the Yupik experts, this memory was presumed lost.

Vera Metcalf, one of the team members, summarized the value of this experience in an emotional foreword (Piinlilleq) to the Akuzilleput Igaqullghet volume, as follows:

These museum collections and research papers are interesting to others, but they are of vital importance to us. The photographs, forefathers’ stories, and historical documents are not enigmatic artifacts or speculation about our past. They are of real individuals, about living in a much different time; and inevitably, we realize that they are not unlike us. …[S]ome portraits show confused and scared faces; but the conversations reveal a firmness of thought. The stories remind us of our responsibility to do what’s best for each other, and most photographs show calm dignity or even defiant confidence. …That is why this collection is a cultural treasure.

Metcalf 2002a, 11; see also Metcalf 2002b

Prints of Moore’s 1912 photographs now adorn the walls of Yupik homes in Gambell and Savoonga, as each family received copies out of some 500 printed books shipped to the island in 2002 and also distributed by two village councils in Nome, Anchorage, and elsewhere. Unfortunately, we could not then replicate this experience for the Chukotka Yupik, as we had no access to any pre-1950 historical photography at that time. That situation was soon to change.

A Perfect “Memory Match”: Waugh Collection 1929–1937

After Akuzilleput Igaqullghet, the same group of Yupik Elders on St. Lawrence Island was engaged in another visual heritage project. In 2001, the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) acquired a collection of 6,000+ historical photographs, negatives, lantern slides, and early film footage created by dental surgeon Dr. Leuman M. Waugh (1877–1972) on his many trips to Alaska and the Canadian North (Krupnik et al. 2011,17–18). For two summers, in 1929 and 1930, Waugh served as a Dental Officer at the rank of Colonel in the US Public Health Service and took part in two tours of duty to Alaska aboard the US Coast Guard Cutter Northland. On these tours, the ship visited 32 Indigenous Alaskan communities in the Bering Sea and along the Arctic coast, including St. Lawrence Island and stopovers in Chukotka.

Altogether, some 130+ photographs and slides from Waugh’s Alaskan collection of more than 1000 images originated from his visits to St. Lawrence Island.[7] These include over 50 personal images (“portraits”); 36 group photographs taken in the village streets and aboard the Northland; and 15 ethnographic scenes featuring Indigenous clothing, patterns of facial and hand tattoos, types of local dwellings, etc. The collection was a jewel of historical photography and a precious heritage resource. Several prints also had people’s names handwritten on the back side by an unknown local person. The names could be easily read and converted into the modern Yupik orthography used on St. Lawrence Island.

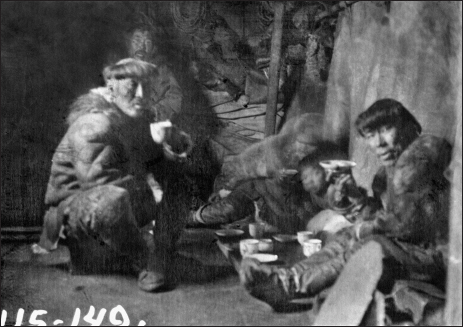

Recognizing its value, I sent paper prints of a handful of Waugh’s images to Willis Walunga and asked whether Elders in Gambell would be interested in working on a new set. The response was swift: “Please send some more pictures!” Shortly after, a shipment of several dozen large-size copies (paper prints) of unlabeled photographs and negatives from the Waugh collection was mailed to Walunga, who promptly engaged his local peers in a team effort to identify faces. Two months later, the paper prints arrived back, with personal names of most—though, not all—people inscribed in the pictures’ margins, back side, or right on the prints (Fig. 2). Several more images were later identified in Nome, Savoonga, and Anchorage by Yupik Elders, thus our team eventually expanded to more than 20 people.

Figure 2

Gambell schoolboys, with their names and comments inscribed by Elders on paper prints

That input by Yupik Elders introduced an entirely new dimension and a second life to Waugh’s photographs. “Faces” matched with names therefore acquired personal context: loving families, living descendants, associated stories. Backed by Elders’ memories, family genealogies, and early documentary records, the photos provided critical information on personalities, people’s lifestyle, and local scenes depicted by a caring, though uninformed, medical doctor.

Much like in the earlier work with Otto Geist’s photography from the island, roughly from the same years, 1927–1933 (Walsh and Diamondstone 1985), all the people featured in Waugh’s pictures were eventually identified by Elders, including those featured in the 70-year-old photos as youth or small children. As more copies of Waugh’s photos reached the island and more related stories were shared and recorded, it became obvious that today’s memories and old pictures constitute a single body of community heritage that needed to be preserved as one piece. With this, we shifted to a new format of the future catalog to be made of photographs accompanied by several stories told by contemporary storytellers about people and scenes featured in the photos. In 2003, the late Vera Oovi Kaneshiro (1934–2013), Yupik educator and language specialist (originally from Gambell), joined the team as catalog co-editor. She personally produced many short stories to Waugh’s photographs and encouraged other Yupik Elders and heritage experts to write their own narratives for the catalog. Dozens of these stories were systematically collected by local partners in writing, taped interviews, e-mails, and even personal conversations.[8]

Eventually, the catalog expanded to 192 pages and 130 named photographs, increasing its heritage value manyfold. Comments from Yupik Elders kept coming until the catalog was finally published in 2011 in 1100 copies (Krupnik and Oovi Kaneshiro 2011), of which 350 copies were sent to Savoonga, 300 to Gambell, and 100+ to Nome to be shared with the descendants of those featured in Waugh’s photographs. An innumerable number of individual photo prints were also produced for St. Lawrence Island families.

Waugh’s images from the later years also made their way to the Bethel-Kuskokwim area in Western Alaska, an area he had explored on several trips in 1935–1937. When scores of his hand-colored lantern slides from that area were shown to a group of Yup’ik Elders during their 2002 visit to the Smithsonian, the Elders immediately identified many places and faces in Waugh’s slides from about 70 years prior. Page-size color photocopies of Waugh’s 300 slides from the area (now at NMAI) were promptly shared with the local Bethel newspaper The Tundra Drums that started re-printing slides on its pages (Fienup-Riordan 2005, viii). Eventually, copies of Waugh’s pictures ended up in people’s homes, as well as in public offices, wall calendars, museum exhibits, and heritage publications (Fienup-Riordan 2008). Dr. Waugh, a composed middle-aged dentist would perhaps have never dreamed that his images would provide such a perfect memory “bridge” between those he befriended in the 1920s and 1930s and their descendants seventy years later.

“A Bridge Too Far”: Harriman 1899 and Bogoras 1901

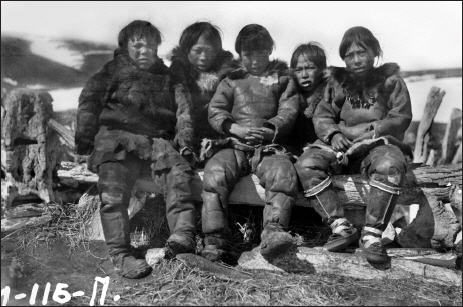

The euphoria generated by Akuzilleput Igaqullghet and the Waugh collection soon faced a reality check. The feeling of a certain time “depth” at which individuals could be identified in old photographs was obvious during the Akuzilleput Igaqullghet project, as several early photos from the NAA collections received no response. Some faces had no names—like those in a picture of Yupik children in Gambell taken in 1889, which we used for the volume cover (Fig. 3). It generated some cautious guesses but no definitive claims about the children’s names. Other similar pictures were met with some interest but were eventually shrugged off (“It’s too early”).

Figure 3

Yupik kids from Gambell

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution NAA INV 01412500 (PL 24). Some Elders assume that the second boy from the right is Sipela (David Sippelu, born ca. 1880) and the first boy from the right is Aghtuqaayak (Richard Oktokiyuk, born ca. 1878).

We soon faced this challenge while examining a small set of 17 images taken in the summer of 1899 during the Harriman Expedition at the Siberian Yupik village in Plover Bay, Chukotka; a portion of a larger collection of copies of the original expedition prints and colored lantern slides held at NMAI.[9] Although these photos are widely known from numerous reproductions (e.g., Goetzmann and Sloan 1982; Grinnell 1995; Hughes 1984), no personal names were attached to the pictures or in short captions written on the slides. In 2003, we spent hours with Walunga in Gambell pouring over copies of Harriman’s photos and trying to combine what we knew of Plover Bay and its people (Fig. 4). Willis never set foot in Plover Bay, but his father Walanga was born and raised there, and Willis had a remarkable memory of the Siberian Yupik who once lived in the area (see Krupnik and Chlenov 2013, 76–80, 328–330). Nonetheless, results were upsetting, as no faces could be identified on the 1899 pictures, even if Willis was able to provide insightful remarks on people’s appearance, as seen from his comment on one photo (Fig. 5):

[These are] six people in a medium-size skin boat, anyapik, made of walrus hides. This is a smaller boat that we use here for our regular hunting, probably of two split walrus hides. They are visiting, not hunting, because they have two women with them; it’s not a hunting crew. They are dressed in an everyday clothing; the first man has a reindeer skin parka; this is winter parka. The second man is wearing a qiipeghaq (Yupik, cloth overcoat) over his fur parka. Otherwise, they look like us.”

NMAI L 1081/P 11066/– “Eskimos in boat. Plover Bay, Siberia, 1899.” Color slide with hand-written caption; reproduced in Grinnell 1995, 170a; Goertzmann and Sloan 1982, 138

Figure 4

Working with Willis Walunga on old photographs in Gambell

Figure 5

Yupik men and women approach the George W. Elder ship of the Harriman Expedition in Plover Bay in July 1899

In 2005, we approached a much larger collection of photographs from Chukotka taken by Waldemar Bogoras during the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (JPNE) in Northeast Siberia in 1900–1901[10] (see Kendall, Mathé, and Miller 1997; Willey 2001). A smaller portion, about 120 photographs (out of his 1000+ total), originated from his trip through the land of the Siberian Yupik, in the southeastern Chukchi Peninsula, including his brief visit to Gambell, on St. Lawrence Island. For most of the photos, the photographer was probably Bogoras’ field assistant, Alexander Axelrod, a fact that Bogoras never acknowledged. In 2005, digitized copies of over 100 of Bogoras’ photos at AMNH and his accompanying captions from museum records were translated into Russian and sent to Chukotka. There, several local partners worked on identifying people and landscapes and wrote expanded comments on a handful of pictures (Krupnik and Mathé 2005, 2009). Sets of Bogoras’ images from Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island were also mailed to Yupik Elders in Gambell and Nome, and in 2007, copies of several dozen photos taken in the Chukotka Yupik community of Ungaziq were shared with the local high school in the town of New Chaplino, where most of their descendants reside today. The photographs were eventually put on display in a local heritage exhibition at the school museum. Writing comments on Bogoras’ photos from 1901 thus became an effort in “knowledge sharing” on both sides of Bering Strait.

The results were disheartening, as no one from either Chukotka or St. Lawrence Island could identify people in the century-old photographs. Nor were efforts aimed at pictures from the Reindeer Chukchi camps on Bogoras’ route to Ungaziq more successful, even if they generated valuable details about people’s clothing, camp activities, and land setting (Vukvukai et al. 2006). Shortly after, a handful of Bogoras’ photographs were published in a Russian heritage collection, Along the Path of Bogoras (Bogoslovskaia, Krivoshchekov, and Krupnik 2008). Again, no individual names were matched to faces from the past. The visual memory link to 1901 was obviously a “bridge too far.”

Another Yupik World? Forshtein 1927–1929

In 2003, while working on Harriman’s and Bogoras’ photos, I gained access to a set of 140 photographs from Chukotka from a slightly later era. They were taken between 1927 and 1929 by Russian anthropologist and schoolteacher Aleksandr S. Forshtein (1904–1968), who spent two years as a school principal in the village of Ungaziq (Chaplino). During these years, he visited several other Yupik communities, including Naukan (Nuvuqaq), Imtuk (Imtuk), Sireniki (Sighineq), and Siklyuk (Siqlluk). Forshtein’s photographs are housed at the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (MAE) in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The MAE collection inventory, evidently prepared by Forshtein himself, included short captions for each negative: the name of the village where a photo was taken; a description of the activities, usually of a few words; and the name(s) of the person(s) in the portrait-style photos. No dates are given for individual photos, aside from a reference to the entire collection, From the Expedition of 1927-1929; Asiatic Eskimos of the Chukchi Peninsula (Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006, 97).

Forshtein’s life story became fully known to us in the 2000s (Krauss 2006; Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006; Reshetov 2002). A promising scholar and a student of Bogoras, he was arrested in 1937 during Stalin’s “great terror” era and was sentenced under fabricated charges to ten years of forced labor in GULAG prison camps. Fortunately, Forshtein survived, but he neither returned to Leningrad nor resumed his work on Yupik ethnology and language (Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006, 93). His Yupik school textbooks and folklore collections were reportedly destroyed in the 1930s and never reprinted (Krauss 2006); miraculously, Forshtein’s negatives backed by medium-size contact prints survived his arrest and years of internment. They remained in the MAE Siberian collections but were hardly used for research and were never published under his name. The Forshtein collection was retrieved in 2003, with the images (negatives and prints) scanned and enhanced (edited), organized by communities, and eventually put on a commercially made CD. Copies were mailed to the ASC in Washington and to the Beringian Heritage Museum in Provideniya for further work with Yupik experts.

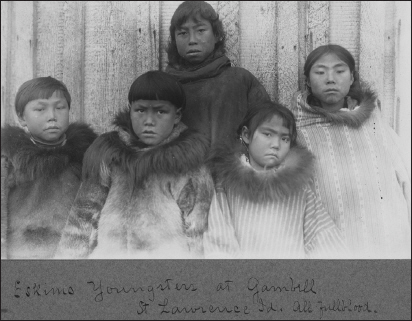

The protocol to gain insight about the people and landscapes featured in Forshtein’s photos was the same as that used for Waugh’s pictures from St. Lawrence Island from almost the same years. Yet the results were markedly different. Elders on the island identified practically everyone in Waugh’s photos from 1929–1930, while in Chukotka, no one among the unnamed individuals on Forshtein’s images was recognized by local Elders. Cultural landscapes of the past were partially remembered (Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006, 99–100), but people’s faces generated no associated names and thus remained silent (Fig. 6). In two similar group photos of Yupik schoolboys taken in Gambell and Sireniki in the same year (1929), all nine boys from Gambell were identified and connected to their families (Krupnik and Oovi Kaneshiro 2011, 138–139; Fig. 2), but no names were recalled for any of the five boys from Sireniki (Fig. 7), who to this day remain unknown, leaving no descendants to share family stories.

Figure 6

Drinking tea inside a Yupik house in Avan

Figure 7

Yupik schoolboys in Sighenek (Sireniki)

The only exception was the strength of historical visual memory related to the former community of Naukan (Nuvuqaq) on Cape Dezhnev. Forshtein visited it for a few days in the summer of 1929 and took 23 pictures, including eight portraits and family group photos. Each portrait photo has personal names recorded by Forshtein himself, while the family pictures list the names of adult men only. Naukan Yupik Elder Elizaveta Dobrieva, born in 1942, could easily identify each person (!) in Forshtein’s Naukan photos, including small children. She thus provided extensive comments on the family and scenic images from 75 years ago. For one of the named photos (“Tlingeun, the schoolgirl”), Dobrieva wrote the following caption:

Llingegun was a daughter of Anaya and Qutgegun. After she graduated from the village seven-grade school, she and another girl, Singegun, daughter of Iyayen, went to study at the medical school in Khabarovsk. They both got sick and passed away; they were buried there.

August 2004; Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006, 103

This is probably the only visual record of a young Yupik woman, who passed away before Dobrieva was even born. To her and other members of her community, Forshtein’s pictures are of immense emotional power, as they have no personal photos from these years and no access to early photography from Naukan preserved in museum collections in Russia and elsewhere.[11]

Forshtein’s photographs thus offer rare cues to assess visual memory loss among Yupik people in Russia. Many villages featured in his photos––Ungaziq, Naukan, Imaqliq, Siqluk, Avan––were closed by the Soviet authorities in the 1940s and 1950s, and their residents were removed from their homeland, often with no chance to see the old sites (Krupnik and Chlenov 2007). This inflicted irreparable damage to people’s memory of home landscapes, placenames, hunting, and ritual space. Forshtein’s photos from 1927–1929 provide precious visual links to these former sites and rituals that were still fondly remembered in the 1970s and 1980s.[12] Although Dobrieva and a few other experts retain exceptional visual and genealogical memory, other Yupik Elders of today express frustration about their inability to identify faces in old photographs. They complain that “hardly anybody is around who still remembers the olden days.” As the generations that once lived, hunted, married, and played in the old community sites gradually passed away, their children and grandchildren, today’s Elders, have preserved only bits of memories associated with their ancestors’ faces and landscapes.

How Memory Changes: Bailey 1921, Hrdlička 1926, and Giddings 1939

Partnering with Yupik Elders on historical photos from museum collections not only provides insights into the depth of people’s visual memory but also how this memory changes, or rather transitions over time. As Elders who had worked on Moore’s and Waugh’s photographs in 1999–2003 aged (and many passed on), the visual memory evidently moved as well.

In 2010, I brought to Gambell a small set of photographs (taken in June 1921 by biologist Alfred M. Bailey), now at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Bailey, an avid photographer, took several hundred photos on his year-long trip to Alaska that included a short stopover on St. Lawrence Island and in Provideniya Bay and Uelen in Chukotka.[13] Seventeen pictures from St. Lawrence Island from both Gambell and Savoonga were mostly portrait and group photos, with no attached personal names. These, I assumed, would be easy to identify; however, the same Elders who were passionate when working on Moore’s and Waugh’s pictures a decade prior were surprisingly mute on Bailey’s photos. It was the first indication that the “memory edge” was moving and that we were losing certain experts who until then had been instrumental in keeping collective visual memory.

Two years later, in 2012, I engaged Elders in Gambell in identifying people in two photographs taken by anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička on his visit to St. Lawrence Island in 1926.[14] They also had no names in short handwritten captions (Fig. 8). Of nine people featured in two photos, none were identified, including five school kids—three boys and two girls aged from about 8 to 12 years. They all had very distinctive faces that could have been familiar to today’s Elders born 6–10 years later. Unfortunately, we ended up empty-handed, with further evidence that the memory “edge” had moved since 1999–2000.

Figure 8

Yupik kids in Gambell

Soon after, it became obvious that people’s visual memory on the island was not fading, just “retreating.” In 2016, at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology at Brown University in Providence, RI, I saw a group of framed black-and-white portrait photos exhibited in the museum’s gallery. Some faces looked stunningly familiar, such as that of a woman with elaborate Yupik-style facial tattoos (Fig. 9), whom I recognized as Yaghunga from Gambell (Yaghunga, circa 1880–1968), also featured in one of Waugh’s pictures from 1929.[15] The photo was part of a massive photographic collection created by the museum’s first director, archaeologist J. Louis Giddings (1909–1964). According to museum records, Giddings took close to 50 photos on St. Lawrence Island, where he worked in the summer of 1939 on an excavation near Gambell. Giddings’ Gambell set, including 32 large-size portraits taken a decade after Waugh’s photography, offered an excellent test to how the memory depth had changed in 14 years.

Figure 9

“Woman from Gambell” (Yaghunga, Nellie Yaronga, ca. 1880–1968)

Most portrait pictures taken in 1939 were staged documentation photos, with paired face and side images, exactly like in Moore’s photography of 1912. All but one person in Giddings’ photos of 1939 have been identified, just like in Waugh’s 1929 set a full decade prior. This time, the few remaining experts from the earlier cohort were joined by Elders born in the 1930s and 1940s.[16] They were as capable in recognizing faces in Giddings’ photos as had been their peers, who worked with Waugh images in 2002. This modest effort confirmed that the same 75-year memory span that was intuitively set a decade prior was holding, just moving.

Discussion

As of this writing, over 1,000 historical photographs featuring Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island Yupik have been identified in museum collections and examined by Indigenous experts in the course of various heritage documentation efforts. It is still the tip of the iceberg, as the total body of early photography from the area is certainly larger.[17] Many more images are housed in museum collections in the US, Russia, and elsewhere, and hundreds of post-1950 photographs, now 70+ years old, remain as family holdings waiting to be shared via websites, social media, and publications (see Dombrovskaia 2013; Leonova 2014; Panáková 2018). Therefore, such work is most certain to continue.

Early photographs and film footage constitute the most direct emotional connection to people’s heritage and to community and family history (see Adams 2000; Arke 2010; Buijs and Jakobsen 2011; Lydon 2010, 2016; Pitseolak and Eber 1993; Wise 2000). Unlike historical documents, early censuses, even family lore, old images enable us to identify with deceased family members in a powerful and highly personal way, generating what has been called “memory prompts and sites of social engagement” (Payne 2011, 97; Griebel, Keith, and Gross 2021, 63). They instill a deep emotional connection, particularly through the general Inuit-Yupik belief that people “return” with their namesakes, the children who bear their names (Kingston 2003).

Nevertheless, the continuity of visual memory is prone to threats common to other components of cultural heritage that rely on person-to-person transmission. Elders grow old and pass away, taking with them precious personal memories of names and faces from the past. Communities move and cultures change, often making identification of past locations and human actions difficult for younger generations. Individual memory fades with age, thus one’s ability to recognize faces in old photos may decline. The memory time horizon does not shrink but rather moves forward, often unequally, even among the nearby communities, as illuminated by memories of Forshtein’s 1929 photographs in Sireniki and Naukan, respectively.

Certain empirically established rules of thumb may be construed from the experience in visual identification described in this paper. Having more Elders—specifically, those experienced in working with historical photographs—creates a larger pool of experts to share visual memory, just like more speakers offer stronger support to a threatened Indigenous language. Established venues to work with old photographs via family and social gatherings, seniors’ groups, heritage activities, and illustrated publications ensure that people keep recalling faces of their community members from the past by talking about their specific physical features, clothing style, jokes, and personal stories. In Alaska and particularly in Canada, Indigenous experts are far more accustomed to working in teams in community-wide efforts, whereas in Chukotka, the preferred practice is that of Elder/s working with an individual visiting researcher (e.g., Panáková 2018). Naturally, collaborative teams have better opportunities to store and share memories and groom younger peers into the “Elders cohort.” Even when a loss of certain outstanding experts is a clear threat to common memory, there may be others who have learned via team or peer interactions—as is illustrated in the latest work with Giddings’ photos from 1939. It ensures stronger (wider?) continuity than when the memory resides with only a few individually gifted Elders, such as Elizaveta Dobrieva and the late Liudmila Ainana (1934–2021) in Chukotka (Oparin 2020).

From this perspective, the closest analog to visual historical memory is perhaps the community’s genealogical memory that also has its recognized specialists who command great authority among their peers. It is common among Chukotka Yupik to remember their kins’ names and relations for three, often four generations, that is, for about 100 years (see Krupnik and Chlenov 2013). An even deeper genealogical memory is preserved among the St. Lawrence Island Yupik, as revealed in their compiled genealogies (Walunga and Gambell Elders 1991) and in Elders’ comments on old censuses and village lists from 100–120 years ago (see Akuzilleput Igaqullghet 2002). That said, it is harder to identify faces one has never seen than it is to recall names of people one has never met. Therefore, the community’s visual memory obviously has a shorter span, estimated at approximately 75–80 years among the St. Lawrence Island Yupik. It hardly reaches beyond 80–90 years, even among exceptional experts, and it produces rapidly diminishing “returns” for pictures older than 90–100 years, such as in Moore’s photographs from 1912 or Bonnet’s images from 1889 examined in 1999–2000. Some limited evidence from other Indigenous groups in Alaska and elsewhere supports this estimated time depth.[18]

This span is markedly shorter in Chukotka, as revealed by comparing the number of faces identified in Forshtein’s and Waugh’s photography from the same years. This may be explained by the smaller number of Elders born before 1950 in Chukotka Yupik communities; the lack of established venues for collective work on historical photographs (as mentioned above); or, more importantly, the much greater level of social disruption and community dislocation experienced by the Chukotka Yupik during the Soviet era, particularly in the 1940–1970s, compared to their island kinsmen (see Krupnik and Chlenov 2007).

Conclusion

As anthropology and Indigenous heritage work advanced into the new digital era, our reliance on museum collection records, such as researchers’ fieldnotes, old documents, and photographs, quickly shifted to new, all-digital domains. Copying, sharing, and disseminating historical images is now an easy operation accessible with one’s smartphone or personal computer. This “easy-to-connect—easy-to-share” advantage of visual records makes them the most promising venue for cultural revitalization and community empowerment (Bell 2003; Bell, Christen, and Turin 2013; Christen 2011; Hennessy et al. 2013; Keith et al. 2019; Lydon 2016; Smith 2008; Tagalik 2019).

In the last 20 years of working with Yupik Elders on historical photographs from their home areas, we have been literally overtaken by the speed of technological change. From printed books, binders of photocopies, CDs, and museum visits, the field has transitioned to new domains where digitized collections can be searched on the web and re-assembled on one’s computer. Old images now easily travel worldwide, copied onto tiny flash-drives, disseminated via social media on smart phones, or accessed online. These changes have been revolutionary.

In many ways, the power of historical photographs is that they “allow people to articulate histories in ways that would not have emerged in that particular figuration if photograph had not existed” (Edwards 2003, 88). Yet photographs are multi-layered resources, so that each layer of information they transmit—faces, activities, social settings, clothing, material objects—has a lifespan of its own. Elders can often identify faces and events they had seen as children and can eagerly describe details about clothing, personal decorations, and housing and boat styles (e.g., Walunga’s comment on an 1899 Harriman photo; see Bell 2003). However, without captions or other accompanying narratives, facial identification has its depth limit, which is usually 60–80 years. This “window of remembering” keeps moving as time and cohorts flow and Elders pass away. It is therefore important that old images be disseminated with (or within) the associated narratives to preserve their original context (see Condon, Ogina, and the Holman Elders 1996; Griebel, Keith, and Gross 2021; Norbert 2017; Pitseolak and Eber 1993; Senangetuk and Tiulana 1987).

It is highly rewarding that historical photographs continue to engage an enthusiastic and appreciative audience in northern communities, or rather many audiences. Whereas Elders may be looking for familiar faces and sites from their early years, many of today’s viewers of digital photo collections are younger computer-literate educators and cultural workers who value historical images as emotional identity and heritage symbols within the general process of cultural revitalization and a new (re)construction of historical memory (Arke 2010; Laugrand 2002; Graburn 1998; Payne 2011; Wise 2000; see also Aymard 2004).

Here, the parallels between genealogical and visual historical memory are quite revealing. Both are types of collective or social memory that reside in individuals but are shared primarily via social settings (Connerton 1989). Even the best genealogical memory requires periodic refreshing, that is, re-telling and sharing. So does the memory of “faces from the past.” It explains why Elders are so fond of looking over old photos and why they work so eagerly in visual heritage documentation. It also reinforces the value of the physical (material) side of heritage preservation, that is of prints, books and catalogs, and wall photos that could be collectively revisited time and again, much like sharing stories strengthens genealogical memory.

Ultimately, the placement of old photographs taken by Bogoras, Forshtein, Moore, and Waugh in local school museums, in village offices, and in people’s homes enables historical images with a distinctive time and cultural frame to begin a second life and be woven into a larger historical narrative by contemporary users in Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island. Yet it is the Elders’ unwavering love and interest in seeing “faces we remember” that remain the prime forces in passing cultural memory to the next generations in an era of modernization and culture change.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

This work would have never been possible without the collaboration of many people. On the research side, I am grateful to my partners in studies of the Chukotka Yupik, Michael Chlenov, and the late Liudmila Bogoslovskaia, and to Levon Abrahamian, Yuri Rodnyi, and Sergei Bogoslovskii, our “men behind the camera” on our field trips. On the museum side, the support of many colleagues—Elena Mikhailova at MAE, Barbara Mathé at AMNH, Stephen Loring and Gina Rappaport at NMNH, Lars Krutak, Donna Rose, and the late Lou Stancari at NMAI, Kevin Smith at the Haffenreffer Museum, and Sabine Bolliger Schreyer at the Bernisches Historisches Museum—helped uncover the richness of museum photo collections. It was the knowledge of Indigenous experts in Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island that preserved faces and names from the past. My deepest appreciation goes to the late Willis and Nancy Walunga, Conrad Ozeeva, Estelle Oozevaseuk, Beda Slwooko, Ora Gologergen, Chester Noongwook, Anna Gologergen, Grace Slwooko, and Vera Oovi Kaneshiro, as well as to Vera Metcalf in Alaska, and Liudmila Ainana, Elizaveta Dobrieva, Valentina Leonova, Valentina Itevtegina Veket, Nadezhda Vukvukai, and many others in Chukotka. My colleagues—Sergei Kan, Ann Fienup-Riordan, and Kenneth Pratt—provided helpful comments based on their work with Elders’ memories and historical photography. Finally, I am grateful to Virginie Vaté and Dmitri Oparin, who encouraged this paper, and to two reviewers, who made helpful comments on the text.

Notes

-

[1]

Many of these photographs of Yupik people taken in the 1970s and 1980s were published in Bogoslovskaia, Krivoshchekov, and Krupnik 2008; Krupnik 2001; Krupnik and Chlenov 2013).

-

[2]

The first and still the largest documented sample of 250+ Yupik historical photographs taken by archaeologist Otto Geist on the island from 1927 to 1933 (now at the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, Alaska and the Polar Regions Collections and Archives at the University of Alaska Fairbanks) was studied jointly with Yupik Elders in the early 1980s (Walsh and Diamondstone 1985). More than 60 photos were later used as illustrations to the three-volume bilingual series (Apassingok et al. 1985-89) that predated our work by almost two decades.

-

[3]

Our core team included Willis Walunga (1925–2017) from Gambell; Vera Metcalf, then at the Bering Straits Foundation in Nome and originally from Savoonga; Liudmila Ainana (1934–2021), Russian Yupik educator from Provideniya, Chukotka; Lars Krutak, then at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), and Chris Koonooka, Yupik language teacher from Gambell.

-

[4]

The first known Indigenous photographer from the region was Charles Menadelook of Wales (1892–1933). Trained as a schoolteacher, he started taking pictures around 1910 in local communities, where he lived during his many teaching assignments (Norbert 2017).

-

[5]

Taking stiff front and side photos was the standard practice of anthropologists from the 1890s onward; the individuals were also measured for their facial and body features using specific measurement forms. This resulted in a huge body of photography of Indigenous people, usually with good provenience (individual’s names, age, place of residence, tribal affiliation) but little ethnographic details, and often clear signs of people’s unease in front of the camera.

-

[6]

Riley D. Moore’s photographs fall under the Division of Physical Anthropology Collection (DPAC) at the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (NAA-SI). All the images are also included in the Aleš Hrdlička Papers, also at NAA, and some can be found in the Manuscript Collection 4696 Selected Prints of Riley D. Moore.

-

[7]

Waugh’s original images (prints and negatives) from St. Lawrence Island were organized in three envelopes according to three main locations he visited: Gambell, Savoonga (‘Sevoonga’ in his spelling), and Punuk Islands. His original attribution turned to be misleading, as several images he labeled as “Gambell” were in fact of family groups and scenes from Savoonga, and some pictures marked as “Gambell” or “Sevoonga” were of people from other places in Alaska.

-

[8]

The most active writers for the Waugh catalog in 2002–2010, besides Vera Oovi and Willis Walunga, were Elders Ralph Apatiki (Anaggun, born 1925), Estelle Oozevaseuk (Penaapaq, born 1921), Beda Slwooko (Avalak, born 1918), Nancy Walunga (Aghnaghaghniiq, born 1929), Ora Gologergen (Ayuki, born 1917), Anna Gologergen (Angingigalnguq, born 1921), Grace Kulukhon Slwooko (Akulmii, born 1921), and others. Many (most) are now deceased.

-

[9]

On Harriman’s photographs at NMAI, see https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/sova-nmai-ac-053.

-

[10]

See https://www.amnh.org/research/research-library/search/research-guides/jesup (accessed April 10, 2021). Prints and negatives taken during the Jesup North Pacific Expedition are part of the Special Collections’ section of the AMNH Research Library in New York.

-

[11]

See a photo of Yupik children in Naukan in the 1920s (?) (in the C. W. Scarborough Collection, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Archives and Manuscripts, Alaska and Polar Region Department, 88-130-34N), that was printed on the cover of the Naukan Yupik Dictionary (Dobrieva et al. 2004). Of the two dozen children featured in the photo, not even one was positively identified by Dobrieva or other Naukan Elders.

-

[12]

One of these old hunting rituals, ateghaq (Attyraq), marking the beginning of the spring hunting season, was depicted in a series of 16 photographs taken by Forshtein in Ungaziq in the spring of 1928 or 1929 (“Attyrak Festival”—MAE И-115-118/135; see Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006, 103–105). The event featured in these photographs had been matched in Elders’ stories recorded in the 1970s and 1980s (Pust’ Govoriat 2000, 267–268).

-

[13]

On Bailey’s trip to Alaska, his three-month sojourn in Wales in the spring-summer of 1922, and the contemporary use of his photographs, see Krupnik 2012, 75–77, with several photos on pp. 74–96).

-

[14]

See Hrdlicka’s Gambell photos at NAA at https://sova.si.edu/details/NAA.1974-31?s=0&n=10&t=C&q=*%3A*&i=0#ref4337.

-

[15]

The picture of Yaghunga and other portraits were displayed in a temporary photographic exhibit, Northern Visions: The Arctic Photography of J. Louis Giddings. See https://hma.brown.edu/exhibits/past-exhibits/northern-visions including the photos from St. Lawrence Island on the right wall (accessed January 6, 2022).

-

[16]

Clement Ungott (Awaliq), b. 1937 and his wife Irma Ungott (Enlegtaq), b. 1945; Anders Apassingok (Iyaaka), b. 1932; Job Koonooka (Naywaaghmii), b. 1946 and June Koonooka (Taviluk), b. 1950 in Gambell; and Chester Noongwook (Tapghaghmii), b. 1933 in Savoonga.

-

[17]

The most recent addition to the St. Lawrence Island Yupik historical photography is a set of 41 pictures taken by Hans-Georg Bandi and his team in Gambell in 1967–1973. They were kindly shared in January 2019 by Sabine Bolliger Schreyer, archaeology curator at the Bern Historical Museum, from Bandi’s monumental collection of some 1,400 slides, a visual record of his archaeological excavations on St. Lawrence Island.

-

[18]

The same (or similar) “solid” memory depth of 70–80 years in identifying faces on old photographs or film footage has been confirmed by researchers working in visual repatriation with other Northern communities: Western Alaska Yup’ik (Ann Fienup-Riordan, personal communication, 01/07/2022); Alaskan Tlingit (Sergei Kan, personal communication, 01/09/2022); Nunivak Island C’upig (Kenneth Pratt, personal communication, 01/06/2022); and elsewhere (Tühoe Maˉori of New Zealand, Binney and Chaplin 2003; Purari Delta people, Papua New Guinea, Bell 2003; and Kainai Nation/Blood Tribe of southern Alberta, Brown and Piers 2006). Some truly outstanding experts often have longer memory (or visual knowledge) up to 90 years or more (Sergei Kan, 01/09/2022). In 2020, Nunivak Island Elders were able to recognize eachperson in a group photo of Nunivak Islanders with Knud Rasmussen in Nome taken in 1924, a time depth of 96 years (Kenneth Pratt, 01/06/2022).

References

- Adams, Amy, 2000 “Arctic and Inuit Photography.” Inuit Art Quarterly 15 (3): 4–19.

- Akuzilleput Igaqullghet, 2002 Akuzilleput Igaqullghet: Our Words Put to Paper. Sourcebook in St. Lawrence Island Heritage and History, edited by I. Krupnik, W. Walunga (Kepelgu), and V. Metcalf (Qaakaghlleq). Compiled by I. Krupnik and L. Krutak. Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology 3. Washington DC: Arctic Studies Center.

- Apassingok, Andres, Willis Walunga, Raymond Oozevaseuk, and Edward Tennant, 1987–89 Sivuqam Nangaghnegha. Siivanllemta Ungipaqellghat / Lore of St. Lawrence Island. Echoes of our Eskimo Elders. Vol. 2. Savoonga and Vol. 3. Southwest Cape. Unalakleet: Bering Strait School District.

- Arke, Pia, 2010 Stories from Scorebysund. Photographs, Colonisation and Mapping [originally published in 2003 as Scoresbysundhistorier]. Copenhagen: Kuratorisk Aktion.

- Aymard, Maurice, 2004 “History and Memory: Construction, Deconstruction and Reconstruction.” Diogenes 51 (1): 7–16.

- Bell, Joshua A., 2003 “Looking to See. Reflections on Visual Repatriation in the Purari Delta, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea.” In Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader, edited by L. Peers and A. K. Brown, 111–124. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bell, Joshua A., Kimberly Christen, and Mark Turin, 2013 “Introduction: After the Return.” Museum Anthropology Review 7 (1-2): 1–21.

- Binney, Judith, and Gillian Chaplin, 2003 “Taking the Photographs Home. The Recovery of a Maˉori History.” In Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader, edited by L. Peers and A. K. Brown, 100–110. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bogoslovskaia, Liudmila S., Vladimir S. Krivoshchekov, and Igor Krupnik, eds., 2008 Tropoiu Bogoraza. Nauchnye i literaturnye materialy [Along the path of Bogoras. Scholarly and literary materials]. Moscow: Russian Heritage Institute-GEOS.

- Brown, Alison K., and Laura Peers, with Members of the Kainai Nation, 2006 “Pictures Bring Us Messages”/ Sinaakssiiksi Aohtsimaahpihkookiyaawa. Photographs and Histories from the Kainai Nation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Buijs, Cunera, and Aviâja Rosing Jakobsen, 2011 “The Nooter Photo Collection and the Roots2Share Project of Museums in Greenland and the Netherlands.” Études Inuit Studies 35 (1-2): 165–86.

- Christen, Kimberly, 2011 “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation.” American Archivist 74 (1): 185–21.

- Christen, Kimberly, 2019 “The Songline is Alive in Mukurtu: Return, Reuse, and Respect.” In Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, edited by L. Barwick, J. Green, and P. Vaarzon-Morel, 153–72. Honolulu and Sydney: University of Hawai’i Press and Sydney University Press.

- Condon, Richard G., Julia Ogina, and the Holman Elders, 1996 The Northern Copper Inuit. A History. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Connerton, Paul, 1989 How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Crowell, Aron L., 2020 “Living Our Cultures, Sharing our Heritage.” Alaska Journal of Anthropology 18 (1): 4–22.

- Dobrieva, Elizaveta A., Evgeniy V. Golovko, Steven A. Jacobson, and Michael E. Krauss, comps., 2004 Naukan Yupik Eskimo Dictionary, edited by S. A. Jacobson. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- Dombrovskaia, Ekaterina Iu., 2013 Istoriia nashei sem’i [Our Family History]. Tula: Vsrok.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, 2003 Introduction to Part 2, “Talking Visual Histories.” In Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader, edited by L. Peers and A. K. Brown, 83–99. London and New York: Routledge.

- Engelstad Driscoll, Bernadette, 2018 “Call Me Angakkuq: Captain George Comer and the Inuit of Qatiktalik.” Études Inuit Studies 42 (1): 61–86.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann, ed., 2005 Yupiit Qanruyutait. Yup’ik Words of Wisdom. Transcriptions and Translations from the Yup’ik by Alice Rearden and Marie Meade. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann, ed., 2008 Yuungnaqpiallerput. The Way We Genuinely Live. Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, in association with Anchorage Museum Association and Calista Elders Council.

- Goertzmann, William, and Kay Sloan, 1982 Looking Far North: The Harriman Expedition to Alaska, 1899. New York: Viking Press.

- Graburn, Nelson, 1998 “Weirs in the River of Time: The Development of Historical Consciousness Among Canadian Inuit.” Museum Anthropology 22 (1): 18–32.

- Griebel, Brendan, Darren Keith, and Pamela Gross, 2021 “Assessing the Significance of the Fifth Thule Expedition for Inuinnait and Inuit Knowledge.” Alaska Journal of Anthropology 19 (1-2): 56–69.

- Grinnell, George Bird, 1995 Alaska 1899: Essays from the Harriman Expedition. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Hennessy, Kate, Natasha Lyons, Stephen Loring, Charles Arnold, Joe Mervin, Albert Elias, and James Pokiak, 2013 “The Inuvialuit Living History Project: Digital Return as the Forging of Relationships Between Institutions, People, and Data.” Museum Anthropology Review 7 (1-2): 44–73.

- Herle, Anita, Jude Philp, and Jocelyne Dudding, 2015 “Reactivating Visual Histories: Haddon’s Photographs from Mabuyag 1888, 1898.” Memoirs of the Queensland Museum—Culture 8 (1): 253–288.

- Hughes, Charles C., 1984 “Asiatic Eskimo: Introduction. Siberian Eskimo. Saint Lawrence Island Eskimo.” In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 5. Arctic, edited by D. Damas, 243–277. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Keith, Darren, Brendan Griebel, Pamela Gross, and Anne Mette Jørgensen, 2019 “Digital Return of Inuit Ethnographic Collections using Nunaliit.” In Further Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography: International Dimensions and Language Mapping, edited by F. Taylor, E. Anonby, and K. Murasugi, 297–316. Amsterdam: Elsevier Press.

- Kendall, Laurel, Barbara Mathé, and Thomas R. Miller, 1997 Drawing Shadows to Stone: The Photography of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, 1897–1902. New York: American Museum of Natural History, and Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- King, Johnathan C. H., and Henrietta Lidchi, eds., 1998 Imaging the Arctic. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Kingston, Deanna Panitaaq, 2003 “Remembering our Namesakes. Audience Reactions to Archival Film of King Island, Alaska.” In Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader, edited by L. Peers and A. K. Brown, 123–135. London and New York: Routledge.

- Krauss, Michael, 2006 “The Eskimo Language Work of Aleksandr Forshtein.” Alaska Journal of Anthropology 4 (1-2): 114–133.

- Krupnik, Igor, 2012 “Alfred Bailey in Wales, Spring 1922.” In Kingikmi Sigum Qanuq Ilitaavut /Wales Inupiaq Sea Ice Dictionary, compiled by W. Weyapuk, Jr. and I. Krupnik, 75–77. Washington, DC: Arctic Studies Center and the Native Village of Wales.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Michael A. Chlenov, 2007 “The End of ‘Eskimo Land’: Yupik Relocations in Chukotka, 1958–1959.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1–2): 59–81.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Michael A. Chlenov, 2013 Yupik Transitions. Change and Survival at Bering Strait, 1900–1960. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Krupnik, Igor, Lars Krutak, Stephen Loring, and Donna Rose, 2011 “Recovered Legacy: Alaskan Photographs of Leuman M. Waugh, 1929–1937.” In Faces We Remember/Neqamikegkaput. Leuman M. Waugh’s Photography from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, 1929–1930, 16–37. Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology 9. Washington DC: Arctic Studies Center and Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Barbara Mathé, 2005 “Jesup Photographs on the Web: A New Project on Waldemar Bogoras’ Historical Photos.” Arctic Studies Center Newsletter 13: 30–32.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Barbara Mathé, 2009 “‘Animated Heritage’: Waldemar Bogoras’ Photographs from the Bering Sea Region (1900–1901) in the ‘Digital Museum’ Era.” Paper presented at the 108th Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Philadelphia, December. https://www.openanthroresearch.org/doi/pdf/10.1002/oarr.10000296.1.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Elena A. Mikhailova, 2006 “Landscapes, Faces, and Memories: Eskimo Photography of Aleksandr Forshtein, 1927–1929.” Alaska Journal of Anthropology 4 (1-2): 92–113.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Vera Oovi Kanechiro, eds., 2011 “Faces We Remember/Neqamikegkaput. Leuman M. Waugh’s Photography from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, 1929–1930.” Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology 9. Washington DC: Arctic Studies Center and Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

- Laugrand, Frédéric, 2002 “Écrire pour prendre la parole. Conscience historique, mémoires d’aînés et régimes d’historicité au Nunavut [Writing to speak. Historical conscience, Elders’ memories, and history regimes in Nunavut].” Études Inuit Studies 26 (2–3): 91–116.

- Leonova, Valentina G., comp., 2014 Naukan i naukantsy. Nyvaqaq enkam nuvuqaghmiit [Naukan and the Naukantsy. Stories of the Naukan Eskimo]. Vladivostok: Dal’press.

- Loring, Stephen, 1997 “Community Anthropology on Nunivak Island.” Arctic Studies Center Newsletter 5: 11–12.

- Lydon, Jane, 2010 “Return: The Photographic Archive and Technologies of Indigenous Memory.” Photography, Archive and Memory 3 (2): 173–187.

- Lydon, Jane, 2016 “Transmuting Australian Aboriginal Photographs.” Word Art 6 (1): 45–60.

- Metcalf, Vera Qaaqghlleq, 2002a “Piinlilleq / Foreword.” In Akuzilleput Igaqullghet. Our Words Put to Paper, edited by I. Krupnik, W. Walunga, and V. Metcalf, 9–10. Compiled by I. Krupnik and L. Krutak. Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology 3. Washington DC: Arctic Studies Center.

- Metcalf, Vera Qaaqghlleq, 2002b “Akuzilleput Igaqullghet: A Participant’s Postscript.” Arctic Studies Center Newsletter 10: 29.

- Moore, Riley D., 1923 “Social Life of the Eskimo of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska.” American Anthropologist 25 (3): 339–375.

- Norbert, Eileen, ed., 2017 Menadelook. An Inupiat Teacher’s Photographs of Alaska Village Life, 1907–1932. Seattle: University of Washington Press and Sealaska Heritage Institute.

- Oparin, Dmitriy A., 2020 “Ainana: istoriia naroda v XX v. cherez sud’bu odnogo cheloveka [Ainana: The history of a nation in the 20th century through a biography].” In Prikladnaia ethnologiia Chukotki. Narodnye znaniia, muzei, kul’turnoe nasledie, edited by O. Kolomiets and I. Krupnik, 405–420. Moscow: PressPass.

- Panakova, Yaroslava, 2018 “Fotografia kak sredstvo prozhivaniia skorbi (Providenskii raion, Chukotka) [Photograph as means to overcome grief (in Provideniya District, Chukotka)].” Kunstkamera 2: 201–208.

- Payne, Carol, 2011 “You Hear It in Their Voice”: Photographs and Cultural Consolidation among Inuit Youths and Elders.” In Oral History and Photography, edited by A. Freund and A. Thomson, 97–114. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Peers, Laura, and Allison K. Brown, eds., 2003 Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader. London and New York: Routledge.

- Pitseolak, Peter, and Dorothy Harley Eber, 1993 People from Our Side. A Life Story with Photographs by Peter Pitseolak and Oral Biography by Dorothy Harley Eber. Montréal and Kingston: McGill University Press (1st ed. 1977).

- Pust’ Govoriat, 2000 Pust’ govoriat nashi stariki. Chukotkam yupigeta ungipamsugit. Rasskazy aziatskikh eskimosov-yupik. Zapisi 1975–1987 gg. [Let our Elders speak / Chukotkam Yupigeta Ungipamsyget. Narratives of the Siberian Yupik Eskimo recorded in 1975–1987]. Recorded by I. Krupnik, edited by I. Krupnik and L. Ainana. Moscow: Russian Heritage Institute (in Russian).

- Reshetov, Aleksandr M., 2002 “Aleksandr Semionovich Forshtein (1904-1968). Stranitsy biografii i repressirovannogo etnografa [Aleksandr Semionovich Forshtein, 1904-1968: Biographical pages on the life of a purged ethnographer].” In II Dikovskie chteniia. Materialy nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii, edited by A. Lebedintsev, M. Gelman, and T. Gogoleva, 275–279. Magadan: Severo-Vostochnyi nauchnyi tsentr.

- Senungetuk, Vivian, and Paul Tiulana, 1987 A Place for Winter: Paul Tiulana’s Story. Anchorage: CIRI Foundation.

- Smith, David A., 2008 “From Nunavut to Micronesia: Feedback and Description, Visual Repatriation and Online Photographs of Indigenous Peoples.” Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 3 (1): 1–22.

- Tagalik, Shirley, 2019 “Reclaiming a Past.” Artic Studies Center Newsletter 26: 17–20.

- Vukvukai, Nadezhda I., Valentina Itevtegina, Igor Krupnik, and Barbara Mathé, 2006 “Faces of Chukotka: Waldemar Bogoras’ Historical Photographs, 1900-1901, as Beringia Heritage Resource.” In Beringiia—Most druzhby/ Beringia—Bridge of Friendship, edited by L. A. Nikolaev, 250–267 (in Russian, 43–60). Tomsk: Tomsk University Press.

- Walsh, Steven, and Judy Diamondstone, comps., 1985 “Notes to the Historical Photographs of Saint Lawrence Island.” Alaska Historical Commission. Studies in History 174: 1-154.

- Walunga, Willis Kepelgu, and Gambell Elders, 1991 “Clans and Lineages of St. Lawrence Island Yupik People.” Copy of unpublished manuscript granted to the author.

- Willey, Paula, 2001 “The Photographic Records of the Jesup Expedition: A Review of the AMNH Photo Collection.” In Gateways. Exploring the Legacy of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, 1897–1902, edited by I. Krupnik and W. W. Fitzhugh, 317–326. Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology 1. Washington DC: Arctic Studies Center.

- Wise, Jonathan, 2000 Photographic Memory: Inuit Representation in the Work of Peter Pitseolak. MA Thesis (Art History), Concordia University, Montreal. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/1237/1/MQ54350.pdf.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Willis Walunga (left), Conrad Oozeva, and Nancy Walunga in Gambell looking over old photographs

Figure 2

Gambell schoolboys, with their names and comments inscribed by Elders on paper prints

Figure 3

Yupik kids from Gambell

Figure 4

Working with Willis Walunga on old photographs in Gambell

Figure 5

Yupik men and women approach the George W. Elder ship of the Harriman Expedition in Plover Bay in July 1899

Figure 6

Drinking tea inside a Yupik house in Avan

Figure 7

Yupik schoolboys in Sighenek (Sireniki)

Figure 8

Yupik kids in Gambell

Figure 9

“Woman from Gambell” (Yaghunga, Nellie Yaronga, ca. 1880–1968)

10.7202/1012840ar

10.7202/1012840ar