Corps de l’article

It has been fifteen years since Études Inuit Studies last published an issue devoted exclusively to the region of Chukotka and its inhabitants.[1] Even if one may view Chukotka as “a marginal area of the Inuit world,”[2] as Yvon Csonka, guest editor of this last issue, suggested, knowledge of this region and its dynamics is still necessary for a better understanding of this world and, more generally, the Arctic and its inhabitants, both indigenous and non-indigenous. Since the last special issue on Chukotka, numerous anthropological, historical, archeological, and linguistic studies of this region have been published. Chukotka never ceases to change, nor does the daily life of its people.

Although the population density of Chukotka is low—there are fewer than 50,000 inhabitants[3] on a territory of 720,000 km², which makes it one and a half-time as large as Yukon—Chukotka displays great population diversity. Indigenous people are in the minority (25 to 30% of the population), but their proportion has been increasing since the end of the Soviet period. During the 1990s, many non-indigenous people left the region,[4] as the special salary granted to northern inhabitants (in Russian, severnye nadbavki[5]) was no longer high enough to compensate for the post-Soviet economic crisis and its dire consequences. Mobility was augmented when settlements that were viewed as unprofitable were simply closed down, as was the case with the town of Iul’tin (Iul’tin district) in 1995, the town of Ureliki (Provideniya district) in 2000, and the town of Shakhtërskii (Anadyr district) in 2008. In short, the turmoil of post-Soviet times has led a number of members of Indigenous communities to leave villages for urban centres, where those leaving the region had left some empty housing and where the “quality of life” was higher—that is, where there were more jobs, better salaries, more consumer goods, better schools, and diverse cultural activities for children. In the 2000s, new migrants came from central Russia (which is called, locally, materik, “the continent”), especially from the Volga region (Kalmykia and Mari El Republic). They took up positions as border guards, doctors, teachers, and school principals. With all of these comings and goings, the population of Chukotka has remained fairly stable over the last decade. Villages have a strong indigenous majority, but they also show great diversity. Ethnic categories used for statistical purposes are problematic; but, even if imprecise, they still give some insight into different communities. According to the 2010[6] census, the indigenous population includes circa 12,800 Chukchi[7], after whom the region is named, circa 1,500 Yupik[8], about 1,400 Even, and 900 Chuvan. According to this same source, the inhabitants who are classified as newcomers (priezzhie) are mainly Russians (about 25,000) and Ukrainians (about 2,900), though there are also a few representatives of other nationalities, including Tatars (451), Azerbaijanis (107), Armenians (105), Uzbeks (79), and Kazakhs (70). Given the subject matter of this journal and the research interests of the contributors to this issue, emphasis falls on the indigenous people of Chukotka.

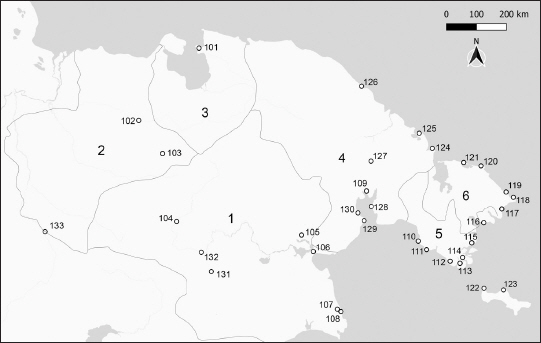

Figure 1

Chukotka (Russia) and St. Lawrence Island (Alaska, USA). Inhabited cities and villages

101 – Pevek; 102 – Bilibino; 103 – Ilirnei; 104 – Lamutskoye; 105 – Kanchalan; 106 – Anadyr; 107 – Alkatvaam; 108 – Beringovskii; 109 – Egvekinot; 110 – Enmelen; 111 – Nunlingran; 112 – Sireniki; 113 – Provideniya; 114 – Novoe Chaplino; 115 – Yanrakynnot; 116 – Lorino; 117 – Lavrentiya; 118 – Uelen; 119 – Inchoun; 120 – Enurmino; 121 – Neshkan; 122 – Gambell (USA); 123 – Savoonga (USA); 124 – Nutepel’men; 125 – Vankarem; 126 – Ryrkaipii; 127 – Amguema; 128 – Konergino; 129 – Uelkal; 130 – Snezhnoe; 131 – Vaegi; 132 – Markovo; 133 – Omolon

Administrative districts: 1 – Anadyrskii; 2 – Bilibinskii; 3 – Chaunskii; 4 – Iultinskii; 5 – Providenskii; 5 – Chukotskii

Indigenous people of Chukotka at a “crossroad of continents”[9]

Located at the extreme northeast of Russia, Chukotka might be seen as a kind of bridge between Asia and America, as it is located in the former but shares characteristics with the latter. The two main subsistence strategies that characterize indigenous activities in the circumpolar world—sea-mammal hunting and reindeer herding[10]—overlap in Chukotka. Sea-mammal hunting predominates in the American Arctic and Greenland, while reindeer herding is largely restricted to Eurasia. Attemps to introduce reindeer herding among the indigenous people of North America have ended, for the most part, in failure (Laugrand 2021). In Chukotka, reindeer herding is restricted largely to the tundra Chukchi, whereas coastal Chukchi and Yupik engage in maritime hunting. These two main uses of natural resources are still very present, forming the contexts within which indigenous languages, ritual practices, and diverse forms of social relationships are preserved. This is one feature of the region that has attracted the attention of researchers.

Furthermore, Chukotka’s indigenous people have historically been in contact with and influenced by both Americans and Russians, trading with both partners. In the nineteenth century, some indigenous people seem to have been more familiar with English than with Russian, and even today there are traces of English loan-words in the Yupik and Chukchi languages. In the twentieth century, the proximity of the American continent has deeply and often dramatically affected the history of the region and its inhabitants, especially during Cold War, when villages deemed to be too close to the American coast were closed and their inhabitants displaced (Chichlo 1981, Krupnik and Chlenov 2007). Relations among Yupik living on both sides of the Bering Strait, who have always been in contact but who were separated for decades for political reasons, invite comparative study. Indeed, the history of interactions between the Yupik of St. Lawrence Island (Alaska) and the Yupik of Chukotka seems to be without precedent. Contributors to this issue provide insight into these matters (Krupnik, Morgounova-Schwalbe, Yamin-Pasternak and Pasternak).

From an economic and political point of view, Chukotka was subject to diametrically opposed extremes of the post-Soviet era: after being among the regions affected most disastrously in the 1990s, it became a model of recovery in the following ten years, after the election of the oligarch Roman Abramovitch as governor in 2000 (He resigned from this position in 2008 to become president of the Chukotka Duma until 2013.) During this period, Chukotka profited from the notoriety of its governor, gaining in visibility, at least to a degree. Since 2008, Chukotka, led by Roman Kopin, has experienced a measure of stability, despite continuing to suffer from inherent challenges, especially regarding transportation and supply. Chukotka remains one of the most expensive, the least accessible, and the least populated of the northern regions. The dreadful experience of the 1990s still haunts local memory.

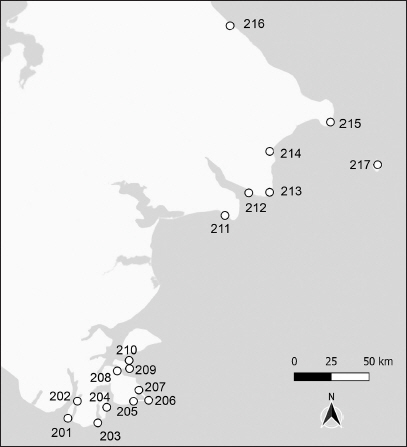

Figure 2

Chukchi Peninsula. Abandoned villages

201 – Avan; 202 – Plover; 203 – Qiwaaq; 204 – Tasiq; 205 – Uqighyaghaq; 206 – Staroe Chaplino (Ungaziq); 207 – Teflleq; 208 – Engaghhpak; 209 – Napaqutaq; 210 – Siqlluk; 211 – Akkani; 212 – Pinakul; 213 – Nuniamo; 214 – Pu’uten; 215 – Naukan; 216 – Chegitun; 217 – Ratmanov Island (Big Diomede, Imaqliq)

Because of its proximity to the United States, Chukotka has long had a special position within Russia. Even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the region retained its official status as a “border security zone” (pogranichnaia zona, in Russian). For this reason, access to the field is difficult for non-Russian researchers, and even Russian citizens need a propusk, a permit, to enter the border zone.[11] Suffering the consequences of these arbitrary and complex restrictions, and no doubt also because of the political nature of her research topic, the anthropologist Patty Gray was forbidden officially from entering the region for five years (see Gray forthcoming).

A region that has played a central role in the anthropology of the Arctic

Chukotka or, more broadly, northeast Siberia occupies an important position in the history of Arctic and Siberian studies. Without providing an exhaustive list of authors who have worked in Chukotka or of all the topics they have addressed, we attempt in this section to evoke some of the main lines of research conducted in this region.

One of the “founding fathers of Siberian studies,” Vladimir Bogoraz (who published in English under the name Waldemar Bogoras), played an essential role in the emergence of a pre-Soviet Russian ethnography (Vakhtin 2006, 51). He conducted research in the Siberian northeast and published numerous studies concerning the Chukchi, Koryak, Itelmen, Even, and Yupik. Vladimir Bogoraz also contributed to the emergence of a “transnational momentum” (Schweitzer 2001) through his participation in the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897-1902), funded by the American banker Morris K. Jesup and led by the American ethnologist Franz Boas. This research resulted in the publication of studies that are still essential references in the field today (e.g., Bogoras 1904-1909; 1910, see also Krupnik and Fitzhugh 2001).

Chukotka retained a central place in Soviet ethnography. Innokentiy Stepanovich Vdovin (a student of Bogoraz) was an itinerant teacher in Chukotka between 1932 and 1934, and he learned the Chukchi language at that time. If his studies reflect the ideological constraints of the Soviet era, they include, nevertheless, important analyzes combining historical and ethnographic perspectives on various topics, such as religious practices (e.g., shamanism and also relations to Christianity, as in Vdovin 1979, 1981) and relations to nature (Vdovin 1976). He also published a monograph on the Chukchi (Vdovin 1965). Another important figure is the Russian ethnologist Varvara Kuznetsova, who stayed in the Amguema tundra between 1948 and 1951. She only published one article, but it stands as an indispensable reference regarding reindeer herding rituals (Kuznetsova 1957; see also Mikhailova 2015). At the end of the 1920s and the dawn of the 1930s, ethnographer and linguist Aleksandr Forshtein went to Chukotka. He was arrested in 1937 and spent ten years in the GULAG. He is best known as the photographer who took unique pictures of Yupik villages (Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006a, Krupnik and Mikhailova 2006b see also Krupnik in this volume), but most of his research has been lost.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, anthropologist Igor Krupnik, anthropologist and linguist Mikhail Chlenov, sociolinguist Nikolai Vakhtin, and biologist Liudmila Bogoslovskaia conducted fieldwork on the Asian Yupik and maritime Chukchi. They were interested primarily in kinship systems (Chlenov 1980), folklore (Chlenov 1981), ritual practices in historical perspective (Krupnik 1979; Krupnik 1980), ethno-ecology (Chlenov 1988; Krupnik 1989), and also in the history of ethnic groups (Krupnik, Chlenov 1979). The foci of their research included, among other things, the cultural inheritance of Yupik and Chukchi in coastal areas and the preservation of cultural memory. Without their publications and without the interviews that they conducted with people born in the early twentieth century, many aspects of Yupik and maritime Chukchi culture would have remained unknown. The publication of the memories of Yupik people living in Novoe Chaplino and Sireniki, which were recorded by Igor Krupnik in the 1970s and 1980s, is of great significance for our understanding of the Yupik world of Chukotka (Krupnik 2000b; see also Krupnik in this issue). Published well after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but drawing on data collected during the Soviet era, the monograph Yupik Transitions: Change and Survival at Bering Strait, 1900-1960 (2013), by Igor Krupnik and Michael (Mikhail) Chlenov, is a comprehensive study revealing the historical dynamics of Yupik society in the first half of the twentieth century. For his part, Nikolai Vakhtin published a fine study of Sireniki language (Vakhtin 2000) and other important works on the sociolinguistics of northern indigenous people (Vakhtin 1992, 2001, 2004). In 2019, he also compiled and analyzed previously unpublished texts in the Yupik language, which had been collected in Chukotka by the linguist Ekaterina Rubtsova in the 1930s-1940s (Rubtsova and Vakhtin 2019, see also Vakhtin below)—another example of the contribution of Soviet research to our knowledge of the region. While coastal populations were the subject of numerous studies, scholars displayed less interest for the Chukchi during this period, especially those living inland. Many aspects of their history and practices remained unknown. Too often, researchers relied on Bogoraz as the ultimate reference, without registering the changes that had occurred since his last publications and without commenting on the contradictions in the works of this great ethnographer (on this matter see Vaté and Eidson 2021). It was not until the early 1990s that new ethnographic data finally began to be produced.

Travelling to Chukotka during the Soviet period was reserved for citizens of the USSR, and even for Soviet researchers it presented all the challenges of “ethnography in a ‘forbidden zone’” (Chichlo 2008). Once the borders were opened in the post-Soviet era, Chukotka became again the object of “transnational” attention. The 1990s were a time of effervescence. Despite complications, organizing a long-term fieldwork became possible once more, and scholars in all fields took advantage of this new opportunity for exploration. The American anthropologist Anna Kerttula was one of the first to arrive in Chukotka. She conducted fieldwork in Sireniki (a coastal village of the Providenskii District) at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. In her monograph entitled Antler on the Sea: The Yup’ik and Chukchi of the Russian Far East (2000), Kerttula writes about a village with both Chukchi and Yupik inhabitants as a complex sociocultural phenomenon in its own right. She worked with many interlocutors who ranged from Russians born outside of the region to indigenous people (Kerttula 2000). This was a first attempt in ethnological research in Chukotka to take a territorial approach to members of diverse groups living in a shared space. Boris Chichlo, a scholar from the CNRS (France), organized two international expeditions in 1991 and 1993[12], thus coordinating the presentation of new information from representatives of different fields and encouraging scholars to work on this region (Chichlo 1993). Kazunobu Ikeya, a researcher from the Osaka National Museum of Ethnology, also travelled to Chukotka and developed comparisons with his earlier fieldwork in East Africa (Ikeya and Fratkin 2005). Virginie Vaté, co-editor of this special issue, and Patty Gray met for the first time in Chukotka’s capital, Anadyr, in 1996. While Gray was conducting fieldwork for her dissertation, Vaté was just about to begin hers, after having gathered data for her master’s thesis while working with the NGO Doctors of the World in 1993 and 1994. Many theses based on anthropological research set in Siberia were defended in the 1990s and 2000s, some of which were set in Chukotka (see Gray et al. 2003, 29-31).

Articles and monographs appeared at an accelerating pace, covering previously neglected topics or exploring familiar ones in greater depth. It became possible to study and to talk about the consequences of the colonial policy of the Soviet power towards the indigenous population, in particular, about the series of forced displacements of the Yupik of Chukotka in the years from 1930s to 1950s (Krupnik and Chlenov 2007; Holzlehner 2011). Fieldwork conducted in the 1990s also highlighted the limits of the autonomy granted to Chukotka’s indigenous people by political authorities. Examples may be found in works by Debra Schindler (1992, 1997), Yvon Csonka (1998), Krupnik and Vakhtin (2002), and Galina Diatchkova (2005), and in Patty Gray’s book The Predicament of Chukotka’s Indigenous Movement: Post-Soviet Activism in the Russian Far North (Gray 2005).

Studies on rituals and religion have been renewed. They demonstrate that some of the practices that were assigned to the past in Soviet studies, no doubt for ideological reasons, are still alive (Golbtseva 2008, 2017, Vaté 2007, 2013, Vatè 2021). This research is not limited to an inventory of continuities, however; it also addresses new forms, resistances, and past and present interactions (Oparin 2020, forthcoming; Vaté 2005a, 2005b; Klokov 2018, 2021; Schweitzer & Golovko 2007). Examples include the new relationship of indigenous people with Christianity, which developed during the 1990s with the arrival of Protestant missionaries of various denominations (Vakhtin 2005, Vaté 2009), and also the evident will on the part of the Russian Orthodox Church to mark the territory by building new Orthodox churches and monuments (Vaté 2019). In recent decades, funerary and commemorative practices have also received a significant degree of attention (Oparin 2012, Nuvano 2006, Panákova 2014).

Several linguists arrived in Chukotka to study the Chukchi language (see Dunn 1999, Zhukova & Kurebito 2004, Weinstein 2010, 2018, and the translation of Omruvie text in the In Memoriam section of this issue). Language analysis has broadened progressively to include sociolinguistic aspects of language use (Leonova 2020; Pupynina 2013; Schwalbe 2015, 2017).

Reindeer herding is a topic that has attracted much interest in the anthropology of Siberia, especially in the decade from 1990 to 2000. The disastrous decline of reindeer herds in the 1990s prompted researcher to devote their attention to this problem, particularly to questions about the ownership of reindeer (Krupnik 2000a, Gray 2000, 2012; Ikeya 2003).

More generally, the subject of indigenous knowledge has come to occupy a central position in research on Chukotka—knowledge of the environment (Krupnik and Vakhtin 1997, Bogoslovskaia and Krupnik 2013) but also of hunting (Bogoslovskaia 2003, Bogoslovskaia, et al. 2007, Mymrin 2016; Jashchenko 2016). Some studies deal with the consequences of climate change and others with the traditional use of natural resources (Bogoslovskaia and Krupnik 2013). The focus on environmental knowledge has had the effect of promoting collaboration with indigenous researchers.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a number of researchers have organized participatory studies involving collaboration with indigenous specialists (see especially Zdor in this issue). The voices of indigenous people —scientists, hunters, elders—are increasingly heard (Bogoslovskaia and Krupnik 2013; Bogoslovskaia et al. 2007; Bogoslovskaia et al. 2008; Leonova 2014). Of particular note is a recent collective monograph on the heritage and history of Chukotka, in which local researchers are widely represented (Kolomiets and Krupnik 2020).

The anthropology of food has also seen significant growth. Under the impetus of the research of Sveta Yamin Pasternak, among others, many new directions are explored regularly (Ainana et al. 2007; Davydova 2019; Dudarev et al. 2019a, 2019b, 2019c, 2019d; Golbtseva 2017; Gray 2021; Kozlov 2007; Kozlov et al. 2007; Yamin-Pasternak 2007; Yamin-Pasternak et al. 2014). This theme is also featured prominently in this issue, which testifies to its dynamism.

The culture and social status of newcomers [priezzhie] in Siberia were rarely subjects of Soviet research. One key publication on this topic is the book Settlers on the Edge: Identity and Modernization on Russia’s Arctic Frontier, by the Canadian researcher Niobe Thompson, which focuses on the non-indigenous population of Chukotka that emerged between 1930 and 1980. This book also gives some insight into the policies of Governor Nazarov in the 1990s, which led to the bankruptcy of the region (Thompson 2008). Nikolai Vakhtin, Peter Schweitzer, and Evgenii Golovko have dedicated a monograph to populations stemming from the old Russian settlements (starozhily) in northeastern Siberia (Vakhtin, Golovko, and Schweitzer 2004).

After the boom of the 1990s and 2000s, research in Chukotka slowed down, to a degree after 2010. In recent years, however, a new generation of scholars has committed itself to the study of the region, exploring new directions. For some time now, Anastasia Yarzutkina has been focusing on the topic of alcohol addiction in Chukotka and on the social life of alcohol in indigenous villages of the region (Yarzutkina 2017; Yarzoutkina and Koulik in this issue). In addition, she has recently published an article showing how reindeer herders in the village of Vaegi have also turned to horticulture and how they have attempted to combine these diametrically opposed economic practices (Yarzutkina 2021).

In 2019, Jaroslava Panáková published an article entitled “Something like Happiness: Home Photography in the Inquiry of Lifestyles,” focusing on visual sensibility in Chukotka, the photographic practices of local people, and the concept of happiness as expressed through visual images (Panáková 2019; see also Istomin, Panáková, and Heady 2014).

In the wake of the ERC project led by Peter Schweitzer (“INFRANORTH —Building Arctic Futures: Transport Infrastructures and Sustainable Northern Communities”), infrastructure has become a topic that has mobilized researchers. Nobody who has travelled in Chukotka can deny that this is a theme of central importance. In 2021, the journal Etnografiia published an article by Elena and Vladimir Davydov about shortages in tundra villages and diverse practices of the “second-hand use of available resources where a creative transformation of a physical object is happening”[13] (Davydov and Davydova 2021 p. 25). In this issue, we include Tobias Holzlehner’s article on the ways in which indigenous people in his Chukotkan field site reuse discarded objects for purposes of construction.

Studies in Chukotka have also taken the form of contributions to visual anthropology (Jääskeläinen 2012, Panáková 2005, 2015, Vakhrushev 2011), which include documentary films (Jääskeläinen 2019, Puya 2014) and even fictional films (on these films and others, see Damiens in this issue).

Research in Chukotka—a new state of the art

In this edition, our intention is to highlight the vivacity and diversity of studies about this region. We have gathered nineteen contributions from various fields, including anthropology, history, sociolinguistics, the history of art, and ethnobotany, written by researchers from several countries and representing institutions around the world. Still, this double edition cannot provide an exhaustive overview of the entire landscape of Chukotkan studies. Some researchers are not represented in this issue because of a lack of time or means on their part or on ours. We hope, however, that the contributions to this issue reflect pertinently the state of the art of research conducted in Chukotka by representatives of various human sciences over the past ten to fifteen years; and we hope that these contributions stimulate the exploration of new paths in the future.

We have organized this issue thematically. We open the collection with an anthropological and historical study by Igor Krupnik, who employs photographs in exploring the depths of historical memory in Chukotka and on St. Lawrence Island (Alaska). Caroline Damiens’s article also engages with visual materials, offering a retrospective of the cinematographic representation of Chukotka in the twentieth century. Then, in the second part, the articles by Tobias Holzlehner and Sofia Gavrilova address in different ways the forced displacement of indigenous populations that occurred from the 1930s to the 1950s. The question of language is the subject of the third part. A sociolinguistic article by Daria Morgounova-Schwalbe focuses on the emotional aspect of Yupik language use and its intergenerational transmission. Mikhail Chlenov examines the origins of a variety of the Aleut language spoken on Medny Island (“Copper Island”) in the Commander Islands. Though Chlenov’s field site lies outside of Chukotka, his research concerns the Eskaleut world and the Asian part of the Bering Sea region. The fourth section offers new perspectives on food and consumption. Elena and Vladimir Davydov analyze the connection between perceptions of the taste of reindeer meat and the different ways of slaughtering reindeer in the tundra and the village of Amguema. Sveta Yamin-Pasternak and Igor Pasternak, who have long been interested in the food traditions of indigenous people on both sides of the Bering Strait, devote their article to the expressive aesthetics of traditional cuisine in Chukotka and Alaska. Anastasiia Yarzoutkina and Nikolaï Koulik address a delicate issue by examining how people relate to both money and alcohol in indigenous villages. Olga Belichenko, Valeria Kolosova, Kevin Jernigan, and Maria Pupynina present meticulous ethnobotanical research on the use of various plants by the Chukchi—a topic that has received more attention in the Inuit world than in this part of the Arctic. In the fifth section, Eduard Zdor and Oksana Kolomiets take up a neglected topic: relations in Chukotka between indigenous people and various non-indigenous actors. Eduard Zdor studies different experiences of cooperation between indigenous experts and scientists. In contrast, Oksana Kolomiets focuses on complex interactions between representatives of indigenous peoples and industrial companies operating in the region. The sixth part combines several contributions that deal with various types of representations. Through analyzing two Yupik folk tales recorded by the linguist Ekaterina Rubtsova in the early 1940s, Nikolai Vakhtin provides insight into local perspectives on the domestication of reindeer. Dmitriy Oparin’s article focuses on the social life of Yupik incantations and, more generally, on the use of the Yupik language in the contemporary religious context. Virginie Vaté returns on the topic of plants, describing how reindeer herders of the tundra of Amguema use them and showing how plants connect people and reindeer. The issue ends with four research notes in a section entitled “Perspectives.” Igor Pasternak combines approaches of the artist and the anthropologist in his reflections on the carving of walrus ivory by Chukchi and Yupik artists. In an autobiographical sketch that we solicited, Vladislav Nuvano retraces his journey and illuminates his perspective as an indigenous researcher. Zoia Weinstein-Tagrina, a culturologist and an artist, provides a study of songs and incantations of the Chukchi. Finally, Dmitriy Oparin presents his most recent multimedia project, “The Memory of a Settlement”, which is devoted to the genealogy, oral history, and photographic archives of Yupik families in Novoe Chaplino (Providenskii District).

These are the paths that we explore in this issue, but there are other possible paths waiting to be explored. Here we will mention some that are not present in this issue or in the published record. In the anthropological literature, for example, the indigenous population of Chukotka is represented almost exclusively by the Yupik and the Chukchi; but there are also Even, Chuvan, and Yukaghir who inhabit the region.

It would be rewarding to study migration in Chukotka, which is dynamic and highly variable. As we asked at the outset of this introduction, who are the Kalmyk and Mari people who may be found in Chukotka today? Why do migrants keep coming to Chukotka? Where do they come from? But mobility does not concern newcomers alone. The isolation and remoteness of Chukotka, along with its inaccessibility, due both to the underdevelopment of its transportation infrastructure and to an excess of political restrictions, make Chukotka seem like a static region. On the contrary, however, people are constantly moving between villages and reindeer herders’ camps, among the different villages, to district capitals, to Chukotka’s capital, Anadyr, or beyond the borders of the region. For a long time, travelling to Alaska was the most common trip abroad because of historical and familial relations across the Bering Straight. But today, destinations lie further abroad, for example, in Turkey, China, or Thailand; and there are many reasons to visit these distant places—e.g., vacations, education, access to healthcare, and so on. Even if the distances that are commonly travelled have increased, this mobility of Chukotkans is not new: during the Soviet period, many had already travelled to Magadan or Leningrad/Saint Petersburg in order to study, and a number of those who did leave Chukotka did not return. What is life like for indigenous students in urban centres? Recently, research has been published on mobility in the Russian Arctic (Vakhtin and Dudek 2020), but Chukotka and its inhabitants do not figure prominently in these studies. This is, therefore, an issue that requires more attention.

Another type of mobility, which seems to be particularly characteristic of Chukotka, consists in international relations with other indigenous people in Canada, Greenland, and Alaska, where Yupik and Inuit also live. The international experience of the Russian Yupik, gained through participation in conferences of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, in international meetings of the peoples of the Arctic, or in tours of folk dance and song ensembles, deserves study in itself. Moreover, the links between the Yupik of Siberia and those of Alaska could still be the subject of new studies, particularly on the recent period, when one can observe marriages between people from the two sides of the Bering Strait, the continuation of cultural exchange, and even the migration of Yupik from Chukotka to Alaska.

In contrast to the situation in North America, there are in Russia few academic publications, works of popular science, or multimedia projects devoted to oral history, to the memories of elders, to the expertise of local people, or to the self-presentation of indigenous youth. The works of Igor Krupnik (2000b) are, of course, a notable exception; but we still feel that greater attention could be paid to oral history and life stories, in the spirit of Nancy Wachovich’s book Sagiyuk (2001). We hope that future researchers will take up these suggestions, though they represent only a few of many possibilities.

We started preparing this issue in 2019. We are finishing it in the spring of 2022. While all our efforts were focused on finalizing this issue, on February 24, 2022, Russia started a war against Ukraine. This situation, the horror of which grips us all, is not without serious effects on both the inhabitants of Chukotka and the prospects for further research in this region. Like the rest of the Northern Far East, Chukotka has welcomed many Ukrainians since the 1930s, and especially after the events in Chernobyl in the late 1980s. A number of Ukrainians still live in Chukotka today. One can only wonder about their situation and the consequences of this conflict for local social relations. The war will surely affect the social climate of Chukotka, leading to the decrease and, perhaps, the full blockage of international relationships, including those with Alaska. It may result in shortages of medicine and other imported products and in the severing of channels of communication (as in the shutdown of Facebook and Instagram on Russian territory). Moreover, we know that Russian soldiers who come from Chukotka, including members of indigenous communities, are stationed in combat zones. We recently learned about the death of a Chukchi man from the village of Vankarem who was serving with the Russian forces in Ukraine. As social anthropologists studying a region in Russia, we cannot ignore this tragedy.[14]

We cannot help but be struck by the irony of our situation: as we finish a volume that brings together contributions from researchers from around the world, with different origins, all in the name of our common interest in this particular region and its inhabitants, we understand that the possibility of continuing this research together, in the field, has been shattered indefinitely.

We write this introduction in April 2022. The issue of the journal should be published in June. We can only hope against all odds that war will be over by then.

We would like this issue to be seen as a call for peace, an expression of our commitment to “thinking together” beyond borders. Losing the spirit of international collaboration and the friendships that have been cultivated over the last thirty years, which are based on the common experience of research in Chukotka, would add one tragedy to another. We hope that this issue will not be the last of its kind and that, in the years to come, we or our younger colleagues can publish a new edition, a new review gathering the great diversity of perspectives of researchers who care about the indigenous people of Chukotka.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Igor Krupnik and Patty Gray for reading and commenting on a preliminary version of this introduction. Any mistakes or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the authors alone.

This issue of Études Inuit Studies has benefitted from the support of many people and institutions. First of all, we would like to thank Igor Krupnik for suggesting that we embark on this adventure and for giving us his unwavering support. We would like to thank the authors who agreed to comply with the multiple constraints involved in the production of such a work. We also express our gratitude to the many reviewers (more than thirty, coming from very diverse countries) for their contributions which helped us to improve the texts. In the process of putting this issue together, we have had to engage with texts in Russian, English, and French, which presented us with a number of linguistic challenges. With the support of the editor of the journal, we have decided to add abstracts in Russian in order to allow people in Chukotka to have some access to the content of the issue. We thank Benjamin McGarr, Fabien Rothey, John Eidson, Patty Gray, Claire Kingston, Elena Lavanant, Marie Velikanov, Léone Grojean and Aurélie Maire for translating and for editing the texts. All our appreciation also goes to Ingrid Gantner, who generously offered her magnificent photographs of miniatures carved on walrus tusks by Valeriy Vykvyragtyrgyrgyn. We thank the artist’s family for allowing these engravings to be featured on our front cover. Valeriy left us while we prepared this issue, and we wish to pay tribute to him, just as we want to pay tribute to other friends who have passed away during these last three years: Liudmila Ainana, Margarita Belichenko, Ivan Omruv'e.

We would not have been able to publish this issue without the journal’s support and particularly the commitment and advice of Aurélie Maire, editor-in-chief of the journal. This edition benefited from the financial support of Etudes Inuit Studies, the Embassy of Canada in Moscow, the Russian Fund for Scientific Research (Rossiiskii nauchnyi fond, RNF), the “Groupe Sociétés Religions Laïcités” research unit (GSRL UMR 8582 CNRS/EPHE PSL), and the Sentinel North Research Chair on Relations with Inuit Societies of Laval University. Thank you all very much.

For their support while preparing this edition, even during our weekends, we thank our relatives and families, particularly John and Matthieu Eidson, Philippe and Christine Klein, Elena Kaminskaya, Elena Marasinova, and Artem Zaitsev.

We finally wish to express all our gratitude to our friends in Chukotka and all of those who welcomed us with a limitless hospitality and generosity. The feeling of debt is enormous. To them, we, humbly, dedicate this edition.

Кытвалынк’ык’oн! Игамсик’аюкамси!

“This publication has been supported by the Embassy of Canada in Moscow. The authors and editorial staff are solely responsible for its content.”

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

The last special issue of Etudes Inuit Studies on the indigenous people of Chukotka was Vol. 31 (1-2), published in 2007 under the supervision of Yvon Csonka. In 1981, two articles in Vol. 5 (2), of this same journal were presented under the heading “Esquimaux asiatiques / Asiatic Eskimo.” This might be viewed as the first special issue devoted to the indigenous people of Chukotka.

-

[2]

Csonka 2007: 24. According to I. Krupnik and M. Chlenov (2013, xxix) “The Russian Yupik […] make up slightly more than 1 per cent of the overall Inuit family.”

- [3]

-

[4]

The population of Chukotka fell from circa 169,000 people in 1989 to around 60 000 in 2000 (Kumo and Litvinenko 2019: 110).

-

[5]

For texts in French we use the transliteration of the Slavists and for texts in English, the Library of Congress transliteration, with minor simplifications. Where appropriate, these transliteration conventions are used with Chukchi and Yupik adaptions. Some authors preferred to use phonetic transliteration, and we have respected their choices and methods. Author’s names and locations have been made to conform to either English or French conventions. When names of Russian authors are known under a certain spelling, we have respected that but still included transliterations in parentheses in the bibliography. This sometimes involves two spellings of a single name, as in the case of Vladimir Bogoraz, who published in English as Waldemar Bogoras. Depending on the quoted reference, we will spell his name with an -s (English publications) or with a -z (Russian publications). This happens with other authors as well.

-

[6]

https://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/Documents/Vol4/pub-04-25.pdf. We refer to official 2010 census figures, because 2020-2021 census data are, as we write this introduction, not available.

-

[7]

In this issue, we use the French word “tchouktche” and the English “Chukchi.” These words are derived from the Russian term (which is probably based on the Chukchi word čavčyv, designating reindeer herders). The self-designation of the Chukchi is Lyg’’oravètl’at (plur.).

-

[8]

We chose to use the word “Yupik” in this issue, as it has become widely accepted within the scholar community. On site, and in Russian, the most common word is èskimos (eskimo) which is not seen locally as pejorative, even if more people dedicated to the indigenous cause and to the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) seem to prefer “Inuit.” However, “Inuit” does not correspond to the self-designation, Yupiget (Krupnik and Chlenov 2013, xxix). Linguists identify three Yupik languages: Central Siberian Yupik (Chaplinskii), Naukan Yupik (Naukanskii), and Sireniki Yupik (Sirenikskii). This last one was officially declared extinct in 1997 (Krupnik et Chlenov 2013: 47).

-

[9 ]

Cf. the volume Crossroads of Continents (1988) by Fitzhugh and Crowell.

-

[10]

In this context, Igor Krupnik uses the terms “Dual Subsistence Model” (Krupnik 1993, 210), describing it as a “subsistence continuum” (Krupnik 1998, 223). However, these two activities do not exhaust the traditional means of subsistence among indigenous people, which also include fishing at sea and in rivers, hunting in the tundra, gathering eggs and wild plants (see Belichenko et al.; Vaté, this volume), etc.

-

[11]

In theory, the legal status of the region as a “border zone” was abrogated in 2018, with the exception of three islands (Big Diomede Island, Wrangel Island, Herald Island). Nevertheless, border guards have continued to control the documents of Russian citizens who are not residents of Chukotka. For foreigners, a special authorization (propusk) is still required for entering the territory. In addition, control of the movements of sea mammal hunters and of coastal citizens has intensified.

-

[12]

The expedition in 1993 ended with a dramatic helicopter accident (see Csonka 2007: 13).

-

[13]

Our translation.

-

[14]

This statement expresses the views of the authors of this introduction only. The authors of the various contributions to this issue had no knowledge of the contents of this introduction before publication and cannot be held responsible for the statements that we make in it.

References

- Ainana L., V. Leont’ev, T. Tein, and L. Bogoslovskaia, 2007 “Traditsionnaia pishcha aziatskikh eskimosov i beregovykh chukchei” [Traditional Diet of Asian Eskimos and Coastal Chukchi]. In: Bogoslovskaia L., Slugin I., Zagrebin I., Krupnik I. (eds), Osnovy morskogo zveroboinogo promysla [Fondements de la chasse marine], Moscow, Anadyr, Institut Naslediia: 390-398.

- Bogoras, Waldemar, 1904–09 The Chukchee. Vol. XI of Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Reprint from Vol. VII of The Jesup North Pacific Expedition, edited by Franz Boas. Leiden, E. J. Brill; New York, G. E. Stechert and Co.

- Bogoras, Waldemar, 1910 Chukchee Mythology. Vol. XII of Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Reprint from Vol. VIII of The Jesup North Pacific Expedition, edited by Franz Boas. Leiden: E. J. Brill; New York: G. E. Stechert and Co.

- Bogoslovskaia, L.S., 2003 Kity Chukotki. Posobie dlia morskikh okhotnikov [Whales of Chukotka. Guide for Marine Hunters], Moscow, Institut Naslediia.

- Bogoslovskaia, L., V. Krivoshëkov, and I. Krupnik (eds), 2008 Tropoiu Bogoraza [On the Way of Bogoraz], Moscow, Institut Naslediia.

- Bogoslovskaia, L., and I. I. Krupnik (eds), 2013 Nashi lʹdy, snega i vetry: narodnye i nauchnye znaniia o ledovykh landshaftakh i klimate Vostochnoi Chukotki [Our Ice, Snow and Winds: Traditional and Scientific Knowledge about the Ice Landscape and Climate of Eastern Chukotka], Moscow, Washington, Institut Naslediia.

- Bogoslovskaia, L., I. Slugin, I. Zagrebin, and I. Krupnik (eds), 2007 Osnovy morskogo zveroboinogo promysla [Basics of Marine Hunting], Moscow, Anadyr, Institut Naslediia.

- Chichlo, B., 1981 Les Nevuqaghmiit, ou la fin d’une ethnie, Études Inuit Studies 5 (2): 29-47.

- Chichlo, Boris (ed.), 1993 Sibérie III: questions sibériennes. Les peuples du Kamtchatka et de la Tchoukotka. Paris, Institut d’études slaves.

- Chichlo, Boris, 2008 “L’ethnographie en ‘zone interdite’”, La revue pour l’histoire du CNRS, 20: 8, http://journals.openedition.org/histoire-cnrs/6192, accessed on May 20 2021.

- Chlenov, Mikhail A., 1980 Perspektivy sotsial’novo i ekonomicheskogo razvitiia eskimosov Chukotki [Perspectives on the Social and Economic Development of Eskimos of Chukotka]. In: Kompleksnoe ekonomicheskoe i sotsial’noe razvitie Magadanskoi oblasti v blizhaishei i dolgosrochnoi perspektive. Tezisy k konferentsii. [Economic and Social Development of Magadan Oblast’ in the Short and Long Term. Abstracts for the Conference], 105-107. Magadan, Magadanskii obkom KPSS.

- Chlenov, Mikhail A., 1981 Kit v folklore i mifologii aziatskikh eskimosov [The Whale in the Folklore and Mythology of the Asian Eskimos]. In: I. S. Gurvich (ed). Traditsionnye kultury Severnoi Sibiri i Severnoi Ameriki. 228–244.Moscou: Nauka.

- Chlenov, Mikhail A., 1988 Ekologicheskie faktory etnicheskoi istorii raiona Beringova proliva [Ecological Factors in the Ethnic History of the Bering Strait Region]. In: V. Tishkov (ed.) Ekologiia amerikanskikh indeitsev i eskimosov. Problemy indeanistiki [Ecology of American Indians and Eskimos. Problems of Indianistics], 64–75.Moscou: Nauka.

- Csonka, Yvon, 1998 La Tchoukotka: Une illustration de la question autochtone en Russie, Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, vol XXVIII (1): 23-41.

- Csonka, Yvon, 2007 Le peuple Yupik et ses voisins en Tchoukotka: huit décennies de changements accélérés, Études Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 7-22.

- Davydov, V.N., and E.A. Davydova, 2021 Proekty razvitiia infrastruktury na Chukotke: ispolʹzovanie resursov zhiteliami natsionalʹnykh sel [Projects of Infrastructure Development in Chukotka: Resource Use by Indigenous Villagers], Etnografiia [Ethnography] 1 (11): 25-49.

- Davydova, E.A., 2019. Kholodilʹnik, solʹ i sakhar: dobycha i tekhnologii obrabotki pishchi na Chukotke [Refrigerator, Salt and Sugar: Food Extraction and Food Processing Technologies in Chukotka] Sibirskie istoricheskie issledovaniia [Siberian Historical Research] 2: 143-161.

- Diatchkova, Galina, 2005 Models of Ethnic Adaptation to the Natural and Social Environment in the Russian North. In E. Kasten (ed.), Rebuilding Identities: Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia, pp. 217-235. Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Dudarev, Alexei, Sveta Yamin-Pasternak, Igor Pasternak, and Valery Chupakhin, 2019(a) Traditional diet and environmental contaminants in coastal Chukotka I: study design and dietary patterns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16:702. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050702.

- Dudarev, Alexei, Sveta Yamin-Pasternak, Igor Pasternak, and Valery Chupakhin, 2019(b) Traditional diet and environmental contaminants in coastal Chukotka II: legacy POP. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16: 695.

- Dudarev, Alexei, Sveta Yamin-Pasternak, Igor Pasternak, and Valery Chupakhin, 2019(c) Traditional diet and environmental contaminants in coastal Chukotka III: metals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16: 699.

- Dudarev, Alexei, Sveta Yamin-Pasternak, Igor Pasternak, and Valery Chupakhin, 2019(d) Traditional diet and environmental contaminants in coastal Chukotka IV: Recommended intake criteria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16: 692

- Dunn, Michael, 1999 A Grammar of Chukchi. PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

- Fitzhugh, William W., and Aron Crowell (eds), 1988 Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska. Washington, D. C., Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Golbtseva, V. V., 2008 The Thanksgiving Ceremony “Mn’in.” In: V. V. Obukhov (ed.), Beringia—A Bridge of Friendship. Materials of the International Scientific and Practical Conference, 42-51. Tomsk, Tomsk State University, Pedagogical University Press.

- Golbtseva, V. V., 2017 Prazdnichnye i zhertvennye bliuda u chukchei i eskimosov [Festive and Sacrificial Meals of the Chukchi and Eskimos] In: Prazdnichnaia i obriadovaia pishcha narodov mira [Festive and Ritual Food of the Peoples of the World], 249–270. Moscow, Nauka.

- Gray, Patty, 2000 Chukotkan Reindeer Husbandry in the Post-socialist Transition. Polar Research 19 (1): 31-37.

- Gray, Patty, 2005 The Predicament of Chukotka’s Indigenous Movement: Post-Soviet Activism in the Russian Far North. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Gray, Patty, 2012 “I should have some deer, but I don’t remember how many”: Confused Ownership of Reindeer in Chukotka, Russia. In: A. Khazanov and G. Schlee (eds.), Who owns the Stock? Collective and Multiple Property Rights in Animals, 27-43. New York and Oxford, Berghahn Books.

- Gray, Patty, 2021 “O vkuse khleba my uzhe zabyli”. Obespechenie chukotskogo sela v postsovetskii period” [“We have already forgotten the taste of the bread”. Provisioning of a Chukchi village in the Post-Soviet period], Sibirskie istoricheskie issledovaniia [Siberian Historical Research], 4: 21-36.

- Gray, Patty, Forthcoming “Exiled from Siberia: Fieldwork conditions in Chukotka in the 1990s”, In: Vaté V. & Habeck O. (eds), Anthropology of Siberia in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Halle Studies in Anthropology of Eurasia.

- Gray, Patty, Nikolai Vakhtin, and Peter Schweitzer, 2003 Who owns Siberian ethnography? A Critical Assessment of a Re-internationalized Field. Sibirica 3 (2): 194-216.

- Holzlehner, Tobias, 2011 Engineering Socialism: A History of Village Relocations in Chukotka, Russia. In: S.D. Brunn (ed.), Engineering Earth: The Impacts of Mega-engineering Projects, 1957–1973. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science + Business Media.

- Ikeya, Kazunobu (ed.), 2003 Chukotka Studies No. 1: Reindeer Pastoralism among the Chukchi. Osaka, Chukotka Studies Committee.

- Ikeya, Kazunobu, and Elliot Fratkin, 2005 Introduction: Pastoralists and their Neighbors—Perspectives from Asia and Africa. In: K. Ikeya and E. Fratkin (eds.), Pastoralists and their Neighbors in Asia and Africa, 1-14. Osaka, National Museum of Ethnology.

- Istomin, Kirill, Jaroslava Panáková, and Patrick Heady, 2014 “Culture, Perception, and Artistic Visualization: A Comparative Study of Children’s Drawings in Three Siberian Cultural Groups”, Cognitive Science 38: 76–100.

- Jääskeläinen, Kira, 2012 Tagikas—Once Were Hunters. Katharsis Fims Oy. (Film).

- Jääskeläinen, Kira, 2019 Northern Travelogues. Illume Oy. (Film).

- JASHCHENKO, O.E., 2016 “Smotri i uchis’”: molodye chukotskie i eskimosskie morskie okhotniki sël Lorino i Sireniki 2010-h gg. [“Watch and Learn:” Young Chukchi and Yupik Marine Hunters from the Villages of Lorino and Sireniki in the 2010s]. In: Krupnik I. (ed.), Litsom k moriu: pamiati L.S. Bogoslovskoi [Facing the Sea. In Memory of Liudmila Bogoslovskaia], 191-213. Moscow, Avgust Borg.

- Kerttula, Anna, 2000 Antler on the sea. The Yup’ik and Chukchi of the Russian Far East, Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

- Klokov, Konstantin, 2018 Substitution and Continuity in Southern Chukotka Traditional Rituals: A Case Study from Meinypilgyno Village, 2016-2017. Arctic Anthropology 55 (2): 117-133.

- Klokov, Konstantin, 2021 Etno-kul’turnyi landshaft chukchei sela Mejnypil’gyno [Ethnocultural Landscape of the Chukchi Village of Mejnypil’gyno]. Sibirskie Istoricheskie Issledovaniia [Siberian Historical Research]. 4: 37-54.

- Kolomiets, O.P., and I.I. Krupnik (eds), 2020 Prikladnaia etnologiia Chukotki: narodnye znaniia, muzei, kulʹturnoe nasledie (K 125-letiiu poezdki N.L. Gondatti na Chukotskii poluostrov v 1895 g.) [Applied Ethnology in Chukotka: Folk Knowledge, Museums, Cultural Heritage (On the Occasion of the 125th Anniversary of the Trip of N.L. Gondatti to the Chukotka Peninsula in 1895)], Moscow, PressPass.

- Kozlov, A. I., 2007 Sovremennyi vzgliad na problem pitaniia morskikh zveroboev Arktiki [A Contemporary Perspective on the Nutritional Problems of Arctic Marine Mammal Hunters]. In: Bogoslovskaia L., Slugin I., Zagrebin I., Krupnik I. (eds), Osnovy morskogo zverobojnogo promysla [Basics of Marine Hunting], Moscow, Anadyr, Institut Naslediia: 369-389.

- Kozlov, A., Nuvano V., VERSHUBSKY, G, 2007 Changes in Soviet and post-Soviet Indigenous Diets in Chukotka, Etudes Inuit Studies 31(1-2): 103-119.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 1979 Zimnie “licjnye” prazdniki u aziatskikh eskimosov [“Personal” Winter Celebrations among the Eskimos of Asia], Etnokul’turnye protsessy v sovremennykh i traditsionnykh obshchestvakh [Ethnocultural Processes in Modern and Traditional Societies] 28-42. Moscow: Institut etnologii akademii nauk SSSR.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 1980 Eskimosy [Eskimos]. In: Gurvich I.S. (ed.), Semeinaia obriadnost’ narodov Sibiri. Opyt sravnitel’novo izucheniia [Family Rituals of Siberian Peoples. Comparative Study], 207-215. Moscow: Nauka.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 1989 Arkticheskaia etnoekologiia [Arctic Ethnoecology]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 1993 Arctic Adaptations. Native Whalers and Reindeer Herders of Northern Eurasia, Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 1998 Understanding Reindeer Pastoralism in Modern Siberia: Ecological Continuity versus State Engineering. In: J. Ginat & A. Khazanov (eds), Changing Nomads in a Changing World, 223-242. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 2000a Reindeer Pastoralism in Modern Siberia: Research and Survival during the Time of Crash. Polar Research 19 (1): 49-56.

- Krupnik, Igor I., 2000b Pust’ govoriat nashi stariki: Rasskazy aziatskikh eskimosov-yupik, zapisi 1975-1987 gg. [Let Our Elders Speak: Stories of Asian Eskimo-Yupik, Recordings from 1975 to 1987]. Moscow: Institut Naslediia.

- Krupnik, Igor I., and Mikhail A. Chlenov, 1979 Dinamika etnolingvisticheskoi situatsii u aziatskikh eskimosov [Dynamics of the Ethnolinguistic Situation among the Asian Eskimos], Sovetskaia etnografiia [Soviet Ethnography]. № 2. pp. 19-29.

- Krupnik, Igor I., and Mikhail A. Chlenov, 2007 The end of “Eskimo land”: Yupik relocation in Chukotka, 1958-1959, Etudes Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 59-81.

- Krupnik, Igor I., and Chlenov, Mikhail, 2013 Yupik Transitions: Change and Survival at Bering Strait, 1900-1960. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Krupnik, I., and W. Fitzhugh (eds), 2001 Gateways. Exploring the Legacy of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, 1897-1902, Washington D.C.: Arctic Studies Centre, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

- Krupnik, I., and E. Mikhailova, 2006a Peizazhi, litsa i istorii: eskimosskie fotografii Aleksandra Forshteina (1927–1929 gg.) [Landscapes, Faces and Stories: Eskimo Photographs by Aleksandr Forshtein (1927-1929)], Antropologicheskii Forum [Anthropological Forum ] 4: 188-219.

- Krupnik, I., and E. Mikhailova, 2006b Landscapes, Faces and Memories: Eskimo Photography of Aleksandr Forshtein, 1927-1929, Alaska Journal of Anthropology 4 (1-2): 92-113.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Nikolai Vakhtin, 1997 Indigenous Knowledge in Modern Culture: Siberian Yupik Ecological Legacy in Transition. Arctic Anthropology 34 (1): 236-252.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Nikolai Vakhtin, 2002 In the “House of Dismay”: Knowledge, Culture, and Post-Soviet Politics in Chukotka, 1995-1996. In: E. Kasten (ed.), People and the Land: Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia, 7-43. Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Kumo, K., and T.V. Litvinenko, 2019 Nestabil’nost’ i stabil’nost’ v dinamike naseleniia Chukotki i eë naselënnykh punktov v postsovetskii period: regional’nye osobennosti, vnutriregional’nye i lokal’nye razlichiia [Instability and Stability in the Population Dynamics of Chukotka and its Settlements in the Post-Soviet Period: Regional, Interregional and Local Specificities of Distinction], Izvestiia RAN. Seriia geograficheskaia [News of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Geographical Series] 6: 107-125.

- Kuznetsova, Varvara G., 1957 Materialy po prazdnikam i obriadam amguemskix olennykh chukchei [Materials on Festivals and Ceremonies of Chukchi Reindeer Herders], Sibirskii etnograficheskii sbornik II, trudy instituta etnografii imeni N.N. Miklukho-Maklaia t.XXXV [Collection of Siberian ethnography II, works of the Institute of Ethnography N.N. Miklukho-Maklai, t XXXV], Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, Moscow-Leningrad, 263-326.

- Laugrand, Frédéric, 2021 “Inuit hunters, Saami herders, and lessons from the Amadjuak experiment (Baffin Island, Canada)”. In: A. Averbouh, N. Goutas and S. Mery (eds), Nomad Lives, from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day, 339-359. Paris: Muséum national d’Histoire Naturelle (Natures en Sociétés).

- Leonova, V.G., 2020 Rodnoi iazyk i deti Chukotki [Mother Tongue and Children of Chukotka]. In: Kolomiets O.P., Krupnik I.I. (eds.) Prikladnaia etnologiia Chukotki: narodnye znaniia, muzei, kulʹturnoe nasledie (K 125-letiiu poezdki N.L. Gondatti na Chukotskii poluostrov v 1895 g.) [Applied Ethnology in Chukotka: Folk Knowledge, Museums, Cultural Heritage (On the Occasion of the 125th Anniversary of N.L. Gondatti’s Trip to the Chukotka Peninsula in 1895)], Moscow: PressPass.

- Leonova, V. (ed), 2014 Naukan in Naukantsy [Naukan and Naukans]/Government of the Autonomous Okrug of Chukotka, Chukotka Inuit Circumpolar Office - Vladivostok, Dalpress.

- Mikhailova, E.A., 2015 Skitaniia Varvary Kuznecovoi. Chukotskaia ekspeditsiia Varvary Grigor’evny Kuznetsovoi [Varvara Kuznetsova’s Journey. Varvara Grigor’evna Kuznetsova’s Expedition in Chukotka]. 1948-1951 gg., Saint Petersburg, MAE RAN.

- Morgunova-Šval’be, D.N., 2020 Iazykovaia adaptatsiia na primere eskimosov-yupik s. Novoe Chaplino, 1998-2018 gg. Vybor iazyka i iazykovoe perekliuchenie [Language Adaptation in the Case of the Yupik Eskimo in the Community of Novoe Chaplino, 1998-2018. Language Choice and Linguistic Switching]. In: Prikladnaia etnologiia Chukotki: narodnye znaniia, muzei, kulʹturnoe nasledie (K 125-letiiu poezdki N.L. Gondatti na Chukotskii poluostrov v 1895 godu) [Applied Ethnology in Chukotka: Folk Knowledge, Museums, Cultural Heritage (On the Occasion of the 125th Anniversary of N.L. Gondatti’s Trip to the Chukotka Peninsula in 1895)], Moscow, PressPass.

- Mymrin, N.I., 2016 Rabota s nabliudateliami, korennymi zhiteliami Chukotki. Nekotorye vpechatleniia i nabliudeniia [Working with Observers and Indigenous Inhabitants of Chukotka. Some Impressions and Observations]. In: Krupnik I. (ed.), Litsom k moriu. Pamiati Liudmily Bogoslovskoi [Facing the Sea. In Memory of Liudmila Bogoslovskaia], 68-86. Moscow: Avgust Borg.

- Nuvano, V. N., 2006 Incineration Ritual among the Vaegi Chukchi. In: K. Ikeya (ed.), Chukotka Studies No. 4: The Chukchi Culture, pp. 23-37. Osaka, Chukotka Studies Committee.

- Oparin, Dmitriy, 2012 ‘The commemoration of the dead in contemporary Asiatic Yupik ritual space’. Études Inuit Studies 36 (2): 187-207.

- Oparin, Dmitriy, 2020 Vospominaniia o chudesakh i kamlaniiakh eskimosskovo shamana: sovremennaia atomizatsiia ritual’noi zhizni i post-sovetskaia nostal’giia [Memories of the Miracles and Ecstatic Séances of the Siberian Yupik Shaman: Contemporary Atomisation of Ritual and Post-Soviet Nostalgia]. Sibirskie istoricheskie issledovaniia[Siberian Historical Research] (2): 229-250.

- Oparin, Dmitriy, Forthcoming Soviet-era Ethnography and Transmission of Ritual Knowledge in Chukotka. In: Vaté V. and Habeck O. (eds), Anthropology of Siberia in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Münster, Halle Studies in Anthropology of Eurasia.

- Panáková, Jaroslava, 2005 The Seagull Flying Against the Wind. Let čajky proti větru (15’); FAMU (Film)

- Panáková, Jaroslava, 2015 Päť životov. Five Lives. Cinq vies, Pamodaj Community, (65’) (Film).

- Panáková, Jaroslava, 2014 The Grave Portraits and the Ancestralization of the Dead (Chukchi and Yupik Eskimo Case). Slovenský Národopis 62 (4): 505-521.

- Panáková, Jaroslava, 2019 Something like happiness: Home Photography in the Inquiry of Lifestyles’. In J. O. Habeck (ed.), Lifestyle in Siberia and the Russian North, 191-256. Cambridge, Open Book Publishers.

- Puya, Vladimir, 2014 Chauchu. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wzDs4S6nPA) (film).

- Pupynina, M.Iu., 2013 Chukotskii iazyk: geografiia, govory i predstavleniia nositelei o chlenenii svoei iazykovoj obshchnosti [The Chukchi Language: Geography, Dialects and Speakers’ Representations of Their Belonging to Their Language Community], Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. Trudy instituta lingvisticheskikh issledovanii [Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. Works of the Institute of linguistic research] 9 (3): 245-260.

- Rubtsova, E. S., and N. B. Vakhtin (ed.), 2019 Teksty na iazykakh eskimosov Chukotki v zapisi E. S. Rubtsovoi [Texts in Yupik languages of Chukotka recorded by E. C. Rubtsova]. Saint-Petersburg, Institut lingvisticheskikh issledovanii RAN: Art-Ekspress.

- Schwalbe, Daria, 2015 Language Ideologies at Work: Economies of Yupik Language Maintenance and Loss. Sibirica 14 (3): 1-27.

- Schwalbe, Daria, 2017 Sustaining Linguistic Continuity in the Beringia: Examining Language Shift and Comparing Ideas of Sustainability in Two Arctic Communities. The Canadian Journal of Anthropology 59 (1): 28-43.

- Schweitzer, Peter, 2001 Siberia and Anthropology: National Traditions and Transnational Moments in the History of Research. Habilitationschrift. Post-Doctoral Thesis. Faculty of the Human and Social Sciences, University of Vienna.

- Schweitzer, P., and E. Golovko, 2007 The “priests” of East Cape: A Religious Movement on the Chukchi Peninsula during the 1920s and 1930s, Etudes Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 39-38.

- Schindler, Debra L., 1992 Russian Hegemony and Indigenous Rights in Chukotka. ÉtudesInuit Studies 16 (1-2): 51-74.

- Schindler, Debra L., 1997 Redefining Tradition and Renegotiating Ethnicity in Native Russia. Arctic anthropology 34 (1): 194-211.

- Thompson, Niobe, 2008 Settlers on the Edge. Identity and Modernization on Russia’s Arctic Frontier. Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press.

- Vakhrushev, A., 2011 Kniga tundry. Povest’ o Vukvukai—malen’kom kamne [The Book of the Tundra. A tale of Vukvukai, the Little Pebble], High Latitudes ltd. Moscou (film). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rg0HGetYTh4&t=118s.

- Vakhtin, Nikolai B., 1992 K tipologii iazykovykh situatsii na Krainem Severe (predvaritel’nye rezul’taty issledovaniia) [For a Typology of Linguistic Situations in the Far North (Preliminary Results of the Study)], Voprosy iazykoznaniia [Questions of Linguistics] 4: 45-59.

- Vakhtin, Nikolai B., 2000 Iazyk sirenikskikh eskimossov: teksty, grammaticheskie i slovarnye materialy [The Language of the Sireniki Eskimos: Texts, Grammar and Vocabulary], LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics 33.

- Vakhtin, Nikolai B., 2001 Iazyki narodov Severa v XX veke. Ocherki iazykovogo sdviga [The Languages of the Northern Peoples in the Twentieth Century. Essays on the Language Shift], Saint-Petersburg, Evropeiskii universitet v Sankt-Peterburge.

- Vakhtin, Nikolai B., 2004 Iazykovoi sdvig i izmenenie iazyka: dogonit li Akhilles cherepakhu? [Language Shift and Change: Will Achilles Catch up with the Tortoise?]. In: Tipologicheskie obosnovaniia v grammatike: K 70-letiiu professora V. S. Khrakovskogo [Typological Foundations of Grammar: On the Occasion of the 70th birthday of Professor V. S. Khrakovskiy], 119-130. Moscow: Znak.

- Vakhtin, Nikolai B., 2005 The Russian Arctic between Missionaries and Soviets: The Return of Religion, Double Belief, or Double Identity?. In: E. Kasten (ed.), Rebuilding Identities: Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia, 27-38. Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Vakhtin, Nikolai B., 2006 Transformations in Siberian Anthropology: An Insider’s Perspective. In: G. L. Ribeiro and A. Escobar (eds.), World Anthropologies: Disciplinary Transformations within Systems of Power, 49-68. Oxford and New York, Berg Publishers.

- Vakhtin, Nikolay, and Stephan Dudeck (eds.), 2020 Deti devianostykh v sovremennoi Rossiiskoi Arktike [Children of the 1990s in the Contemporary Russian Arctic], Saint-Petesbourg, Izd-vo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge.

- Vakhtin, N. B., E. V. Golovko, and P. Schweitzer, 2004 Russkie starozhily Sibiri. Sotsialʹnye i simvolicheskie aspekty samosoznaniia [The Russian Old-Settlers. Social and Symbolic Aspects of Self-Awareness], Moscow, Novoe izdatelʹstvo.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2005a Maintaining Cohesion Through Rituals: Chukchi Herders and Hunters, a People of the Siberian Arctic. In: K. Ikeya and E. Fratkin, Pastoralists and their Neighbours in Asia and Africa, 45-68. Osaka, National Museum of Ethnology, Senri Ethnological Studies.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2005b Kilvêi: The Chukchi Spring Festival in Urban and Rural Contexts. In: E. Kasten (ed.), Rebuilding Identities: Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia, 39-62. Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2007 The Kêly and the Fire: An Attempt at Approaching Chukchi Representations of Spirits. In: Frédéric B. Laugrand and Jarich G. Oosten (eds), La nature des esprits. Humains et non-humains dans les cosmologies autochtones/Nature of Spirits in Aboriginal Cosmologies, 219-239. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2009 Redefining Chukchi Practices in Contexts of Conversion to Pentecostalism. In: M. Pelkmans (ed.), Conversion after Socialism: Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union, 39-57. New York, Berghahn Books.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2013 Building a Home for the Hearth: An Analysis of a Chukchi Reindeer Herding Ritual. In: D. G. Anderson, R. P. Wishart, and V. Vaté (eds.), About the Hearth: Perspectives on the Home, Hearth and Household in the Circumpolar North, 183-199. New Yorkf and Oxford, Berghahn Books.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2019 L’orthodoxie aux confins de la Russie arctique : Le marquage religieux d’un territoire stratégique. SciencesPo Centre de recherches internationales, Avril 2019. https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03471421, accessed on 12 April 2022.

- Vaté, Virginie, 2021 Vozvrašenie k chukotskim dukham [Return to the Spirits of the Chukchi]. Sibirskie istoricheskie issledovaniia [Siberian Historical Research] 4: 55-75.

- Vaté, Virginie, and John Eidson, 2021 The Anthropology of Ontology in Siberia—a Critical Review, Anthropologica 63 (2), https://doi.org/10.18357/anthropologica63220211029

- Vdovin, Innokentii S., 1965 Ocherki istorii i etnografii chukchei [Essays on the History and Ethnography of the Chukchi], AN SSSR. Moscow-Leningrad, Nauka.

- Vdovin, Innokentii S., 1976 Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniiakh chukchei [The nature and the human in the religious representations of the Chukchi]. In: I. S. Vdovin (ed.), Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniiakh narodov Sibiri i Severa [The Nature and the Human in the Religious Representations of the Peoples of Siberia and the North], 217-253. Leningrad, Nauka.

- Vdovin, Innokentii S., 1979 Vliianie khristianstva na religioznye verovaniia chukchei i koriakov [The Influence of Christianity on the Religious Beliefs of the Chukchi and Koryak]. In: I. S. Vdovin (ed.), Khristianstvo i lamaizm u korennogo naseleniia Sibiri (vtoraia polovina XIX v-nachalo XX v) [Christianity and Lamaism among the Indigenous Peoples of Siberia (second half of the 19th-early 20th centuries)], 86-114. AN SSSR, Leningrad, Nauka.

- Vdovin, Innokentii S., 1981 Chukotskie shamany i ikh sotsial’nye funktsii [The Chukchi Shamans and their Social Functions]. In: I.S. Vdovin (ed.), Problemy istorii obshchestvennogo soznaniia aborigenov Sibiri (po materialam vtoroi poloviny XIX-nachala XX v.) [Problems of history of collective conscience of the Indigenous People of Siberia (according to materials of the first half of the 19th century and of the beginning of the 20th century)], AN SSSR, pp. 178-217. Leningrad, Nauka.

- Wachowich, Nancy, 2001 Sagiyuk. Stories from the Lives of Three Inuit Women, Montreal, Kingston and London: Ithaca and Mc Gills Queen’s University Press.

- Weinstein, Charles, 2010 Parlons Tchouktche. Une langue de Sibérie. Paris, L’Harmattan.

- Weinstein, Charles, 2018 Chukchi French English Russian Dictionary. 2nd ed. Anadyr; Saint Petersburg: Lema (3 vol.).

- Yarzutkina, A.A., 2017 Priiuty, reidy, desanty: praktiki sosushchestvovaniia zhitelei s alkogolem v chukotskikh selakh. Strategii minimizatsii problemy [Shelters, Raids, Landings: Practices of Inhabitants’ Cohabitation with Alcohol in the Villages of Chukotka. Strategies of Minimization of the Problem], Istoricheskaia i sotsial’no-obrazovatel’naia mysl’ [Historical and socio-Educational Thinking]. 9 (6/2): 137-143.

- Yarzutkina, A.A., 2021 Ovoshe(olene)vodstvo v chukotskom sele Vaegi [Vegetable Production and Reindeer Husbandry in the Chukchi Village of Vaegi], Sibirskie istoricheskie issledovaniia [Siberian Historical Research] 4: 94-111.

- Zhukova, Alevtina N., and Tokusu Kurebito, 2004 Bazovyi tematicheskii slovar’ koriaksko-chukotskikh iazykov / A Basic Topical Dictionary of the Koryak-Chukchi Languages. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Yamin-Pasternak, Sveta, 2007 An Ethnomycological Approach to Land Use Values in Chukotka, Etudes Iuit Studies, 31 (1-2), 121-141.

- Yamin-Pasternak, Sveta, Andrew Kliskey, Lilian Alessa, Igor Pasternak, and Peter Schweitzer, 2014 The Rotten Renaissance in the Bering Strait: Loving, Loathing, and Washing the Smell of Foods with a (Re)Acquired Taste. Current Anthropology 55 (5): 619-645.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Chukotka (Russia) and St. Lawrence Island (Alaska, USA). Inhabited cities and villages

101 – Pevek; 102 – Bilibino; 103 – Ilirnei; 104 – Lamutskoye; 105 – Kanchalan; 106 – Anadyr; 107 – Alkatvaam; 108 – Beringovskii; 109 – Egvekinot; 110 – Enmelen; 111 – Nunlingran; 112 – Sireniki; 113 – Provideniya; 114 – Novoe Chaplino; 115 – Yanrakynnot; 116 – Lorino; 117 – Lavrentiya; 118 – Uelen; 119 – Inchoun; 120 – Enurmino; 121 – Neshkan; 122 – Gambell (USA); 123 – Savoonga (USA); 124 – Nutepel’men; 125 – Vankarem; 126 – Ryrkaipii; 127 – Amguema; 128 – Konergino; 129 – Uelkal; 130 – Snezhnoe; 131 – Vaegi; 132 – Markovo; 133 – Omolon

Administrative districts: 1 – Anadyrskii; 2 – Bilibinskii; 3 – Chaunskii; 4 – Iultinskii; 5 – Providenskii; 5 – Chukotskii

Figure 2

Chukchi Peninsula. Abandoned villages

201 – Avan; 202 – Plover; 203 – Qiwaaq; 204 – Tasiq; 205 – Uqighyaghaq; 206 – Staroe Chaplino (Ungaziq); 207 – Teflleq; 208 – Engaghhpak; 209 – Napaqutaq; 210 – Siqlluk; 211 – Akkani; 212 – Pinakul; 213 – Nuniamo; 214 – Pu’uten; 215 – Naukan; 216 – Chegitun; 217 – Ratmanov Island (Big Diomede, Imaqliq)

10.7202/019713ar

10.7202/019713ar