Résumés

Abstract

Night Drawing is an action that challenges perceptual habits—an embodied experience at the limits of the visible. Dealing with light at night is an urgent issue for a variety of social and cultural reasons and concerns the wider context of anthropogenic climate change. This paper deals with lighting conditions in the urban night on one hand and forms of cognition through drawing on the other. When it comes to artificial light at night, the foremost concerns include safety, light pollution, and the loss of darkness. However, the fact that darkness is also caused by and understood through artificial light is rarely discussed. Night Drawing aims to renegotiate long-standing assumptions about the benefits of urban nighttime lighting. This approach offers a challenge to the brighter the better idea and re-writes the appearance of nocturnal land/cityscapes. Night Drawing is a critical, innovative approach, a practice as a method to pay further attention to the representational power of the light at night. It aims at a technique of seeing in a new way—a re-examination and a new conception of urban darkness.

Résumé

Le night drawing est une action qui défie les habitudes perceptives, une expérience incarnée aux limites du visible. La gestion de la lumière pendant la nuit est un problème urgent pour diverses raisons sociales et culturelles et touche au contexte plus large du changement climatique anthropique. Cet article traite d’une part des conditions d’éclairage dans la nuit urbaine, et des formes de cognition par le dessin d’autre part. En ce qui concerne la lumière artificielle pendant la nuit, les principales préoccupations sont la sécurité, la pollution lumineuse et la perte d’obscurité. Cependant, le fait que l’obscurité soit également causée et comprise par la lumière artificielle est un phénomène rarement discuté. Le night drawing vise à renégocier des hypothèses de longue date sur les avantages de l’éclairage urbain nocturne. Cette approche se situe en porte-à-faux avec l’idée que la brillance est nécessairement mieux, et réécrit la physionomie des paysages terrestres/urbains nocturnes. Le night drawing est une approche critique et innovante, une pratique en tant que méthode permettant d’accorder plus d’attention au pouvoir de représentation de la lumière pendant la nuit. Il vise une nouvelle technique du voir, de même qu’un réexamen et une nouvelle conception de l’obscurité urbaine.

Corps de l’article

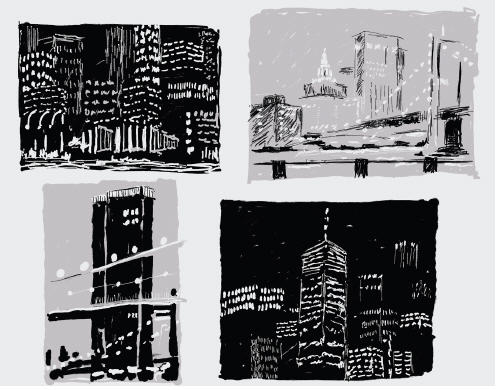

Figure 1

Night Drawing, Pier 35, New York, 2019

Introduction

What impact does light have on the appearance of the nocturnal land/cityscape? How does artificial light shape and affect our recognition of brightness and darkness? And how can we visually apprehend the differences between the light, the dark, the shadows, and the atmosphere it creates? These questions arise in the undertaking of the built environment and its visual representation. The amount of light in the urban night seems unquestionable for many and therefore risks being taken for granted and left unexplored. (Figure 1)

The drawing project that I outline here is a critical, innovative approach, a method I developed to further consider the visible and invisible representational power of nocturnal illumination. While examining the urban night habitat in situ, spatial experiences are recorded with pen and paper. The work offers a participatory platform and interrogative expedition of contemporary night atmospheres. It endorses the poetics of space and seeks visual, aesthetic, and atmospheric reciprocity. Night Drawing challenges perceptual habits—an embodied experience at the limits of the visible. It tests and renegotiates viewing attitudes by drawing on site in the nocturnal urban space. This means questioning the image and appearance of the city at night by looking at its light with a pencil. Drawing outdoors in unfamiliar light environments—rather gloomy, dark surroundings—engenders possibilities for fresh observation, questioning physical awareness with bright and dark light impressions. Night Drawing calls for a new notion of “urban darkness” (Meng forthcoming) by addressing how light causes changes in spatial perception and action.

Night Drawing arose as a practice from my professional work as a graphic designer, art director, and photographer, combined with my interest in visual culture, human attention, passive perception, and my growing awareness of industrial and political changes in the urban environment. John Berger (2020) noted how technological innovation made appearances volatile and disembodied. Urban developments transformed appearances into refractions of light, like mirages: “Consequently no experience is communicated. All that is left to share is the spectacle, the game that nobody plays and everybody can watch.” (Berger 2020: 77–78). Georg Simmel described the urban environment as evoking a “blasé” human attitude when city dwellers protect themselves from too much interference and information (Simmel 2010: 105–106). Comparatively, Gernot Böhme writes that “[t]he noise of the modern world and the occupation of public space by music has led to the habit of not-listening (Weghören)” and asks, “[w]hat does […] listening as such, not listening to something mean?” (Böhme 2000: 17). The notion of unconscious bodily awareness is central in my argument about the perception of light at night, especially in interaction with darkness.

Darkness in the urban night must be viewed and understood critically for a sustainable and social life. Light is shown by darkness as darkness is by light. It can be argued that modern brightness at night endangers blindness and ignorance toward darkness. The over-illuminated cities at night need to be reconsidered: The question of how much light and darkness people need to live seems in the context of capitalist cities to be less a choice than a habit (e.g. Zumthor 2006: 90). The method of drawing demands a rediscovery, a new perception, and an alternative idea of darkness. The visual focus is on the little-explored origins of the darkness created by artificial light and its shadows, while the aim is to actively observe and question our surrounding light-night constructs.

I initiated Night Drawing in 2018 as a practical method for my PhD research project Light at Night: What is the Matter with Darkness (Meng forthcoming). Since then, I have been organizing guided and collaborative drawing events in London and New York. The goal of the project is to encourage people—with or without drawing skills—to experience close observation that opens different perspectives. Drawing at night provokes active vision and connects the eye with a gesture. In other words, Night Drawing is a way of expanding seeing and reacting to one’s nocturnal land/cityscape. It is a way of paying attention: heeding, reflecting, and renegotiating the ordinary or habitual view.

This research explores the challenge of visibly translating something that is nebulous but tangible—namely, atmospheres and shadows created by urban lighting, which are felt but not seen. I describe an interdisciplinary approach to investigating how the urban night is represented through light and discuss possibilities of perception by unpacking what light and dark do, or have the potential to do, at night. This paper argues that spatial representation is also visual thinking that must respond to environmental issues and therefore requires practices of extensible visual engagements. What follows lies at the interface between my ongoing practice of nocturnal drawing, urban environmental thinking (i.e. Burckhardt 2012), a philosophy toward atmospheres (i.e. Böhme 2017), and media ecology theory of effects and affects on human perception (i.e. Guattari 1995; Massumi 1995).

In sum, this paper examines symbolic, cultural, and visual stereotypes of the light image the urban night creates. This is done from a twofold perspective. The first is by reviewing the rooted rationality of light in Western society, in particular, the perception of darkness that emphasizes negative ideas associated with insecurity and, above all, with an enemy to be defeated. The second is by experiencing light atmospheres that enhance contemporary urban environments through representative efforts. Specifically prioritizing the visual representation of lighting space over its experience. Consequently, this article seeks to see darkness in a new light and an advanced conception of “urban darkness.” It is divided into four sections: 1. Representation by Light, 2. Atmospheric Affects, 3. Gesture of Drawing, 4. Marks on Paper.

Figure 2

Night Drawing, Brooklyn Bridge Park, New York, 2021

Representation by Light

For the city is the most public manifestation of our shared life, the most visible representation of human activity. And if someone were to dig us up in two thousand years, once all knowledge of our written language had disappeared, the cityscape would be the only thing by which we might be judged.

Burckhardt 2012: 27

Urban nocturnal space is the site where artificial light most strongly articulates the visible landscape. The interplay between the illuminated and the non-illuminated parts of an environment defines space. Among other things, it is visual storytelling. Urban lighting is of a theatrical nature. In the theatre, the dynamic between light and dark shapes the space of attention and creates settings where actions do and do not take place.[1] We can say the same about the urban night. It is a fabricated light environment where power structures play out to bring things both in and out of sight (i.e., Burckhardt 2012; McQuire 2005; Schivelbusch 1995). Artificial light not only illuminates important urban landmarks, but also hides others, and turns “unattractive” areas into impenetrable darkness (McQuire 2005: 133). (Figure 2)

The artificial light at night is staged. It is frequently used to draw the contours of architecture, represent its forms, and brand the image of the cityscape. “[T]he functionalism of Modernist architecture makes itself felt at the visual level, which is to say, its ‘solutions’ are above all solutions for the eye.” As Lucius Burkhardt notes, we must ask ourselves why activity in social spheres such as politics, sport, and art must face critical public scrutiny, while urban planning can mostly proceed freely. And while the public may hold opinions about the way the urban environment impacts everyday life, there are few avenues for public expressions of this concern (Burckhardt 2012: 27, 64).

It is important to consider the city night representation by light not only in terms of marketing/branding purposes, safety, and technology issues but also in terms of the effective/affective properties of light. The rapid changes of the urban night, the impact on the public space, and the physical experiences it affords us must be included in considerations for the development of urban nighttime illumination. In this respect, my work follows urban thinkers who put public space first for an equal, sustainable living environment such as Jan Gehl (2011), Jane Jacobs (1992), Reinhold Martin (2016), Shannon Mattern (2021), Saskia Sassen (2001), and William H. White (1988).

Light design shapes movements and life in its space, social practices, and interactions. The integration of light at night, be it as infrastructure, technology, or ambiance, requires, as the research project Configuring Light/Staging the Social[2] stresses, an urgent “empirically grounded social understanding” from different disciplines (Anon n.d.). Light influences actions and moods in space, whether indoors or outdoors, and plays a significant role in the perception of its space. Light is material, with weight, volume, and texture. Artificial light forcefully expresses its nocturnal land/cityscape in visible terms. Consequently, urban planning and its politics have a decisive optic impact on the landscape of the city and thus on the aesthetic and atmospheric experience of its space (e.g. Edensor 2017).

As far as the ideological aspects of safety through light are concerned, public lighting also has its complications. Bright light can mark nocturnal spaces as “dangerous” or “problematic,” as in the case of “functional” lighting on housing estates, regardless of whether they are dangerous or not (Slater 2017: 31). A housing estate in Whitecross, London produces such extremely bright, poor quality light that tenants stick black trash bags over their windows so they can sleep (Entwistle and Slater 2019: 13).[3] Subsequently, in a metropolis like London today, darkness within certain wealthy neighborhoods is understood as a luxury that offers a reprieve of calm and peace from the sensory overload of urban life (Slater 2017: 31).

How can Night Drawing help us to better understand the socially mediated and visually contested nature of light in our nocturnal lives? Night Drawing does not promise a solution to the complex complications of nocturnal illumination but rather aims to trigger a shift in perspective and to see darkness in a new light. It establishes an alternative method for the observer: drawing as a method to review the relationships between experience, perception, and representation. “A line, an area of tone, is not really important because it records what you have seen, but because of what it will lead you on to see.” (Berger 1969: 23). To draw at night is to look out for the contrasts, shadows, and spotlights that are manufactured by light. Night Drawing aims to address how our perception of light at night is shaped by visual history and representational practices (e.g. Cubitt 2014), and whether the method of drawing at night affords a different perspective.

Night Drawing corresponds to the practice of “deep listening”, a profound method of attention to sound, established by the composer Pauline Oliveros (2015). Oliveros used the music school as a critical example, where the educational institution is centered on techniques, the ambition to train the ear. She countered that the ear cannot be trained: an environment such as a music school is more likely to cultivate the skill of listening. The difference between hearing and listening is that the ear hears, the brain listens, and the body senses vibration (Oliveros 2015). There is a similar distinction between seeing and looking at the light and darkness in the urban night. Looking at the dark to see new things is analogous to Oliveros’ practice of encouraging new ways of listening to hear different things. Seeing implies passivity, whereas looking, like looking for someone, is more active.[4] The process of drawing at night demands for active, performative perception. It goes against the habit of only seeing things in the light; a habit that over time has led to little or no attention being paid to the image of darkness created by artificial light in the urban night space.

Our frequent failure to notice changes, even when they are fully within view, is telling. Alva Noë writes that visual attention to detail is an awareness that occurs in the liminal space between conscious and unconscious, an area of cognition about which we still know very little. There has been extensive research into this aspect of vision and attention, termed “change blindness” which impacts perceptual experience. One famous example is Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons’s study of The Invisible Gorilla[5]. Their experiment shows that the appearance of a man in a monkey suit dancing through a sports team can go unnoticed when the viewer of the movie clip is asked to count the number of ball passes going around the team. (Noë 2004: 51–53). We do not see that which we are not looking for.

Stuart Hall’s (1997) work examined widely how perception is influenced by cultural and political systems of representing the world to us. Representative practices include, among other things, the exercise of symbolic and visual stereotypes. When a particular presentation is practiced repeatedly, it becomes a powerful trope and seems natural and inevitable (Hall 1997: 259). Urban practices of gleaming light at night, and the cultural associations around the perception of darkness, are good examples of this. Accordingly, and contrary to what some psychologists and neuroscientists argue, the perception of light at night is not simply a matter of a cognitive process or neurological mechanism inherent in an individual (Howes 2005: 322).

The way things appear to us also depends “[…] on the chromatic properties of surrounding and contrasting objects.” (Noë 2004: 125). Mikkel Bille and Tim Flohr Sørensen note “shedding light on objects is about attributing perceptual form to the objects, and hence the social use of light is not as much on the object as it is for the object.” (Bille and Sørensen 2007: 270). The idea of the line, building along lines, “the straight line” as Tim Ingold (2016) calls it, can be associated with the visuality of urban lighting practices. This is clearly visible in the presentation of light in nightscapes such as London and New York. Lighting for the sake of contour, form, and outline—representational and controllable—is a clear echo of a widespread mode of thinking in the Western world that associates the so-called objective and the rational with social and moral consequences. This is where urban space is misconceived by some architects and planners who pursue a “straight” mindset that strives to get directly from one point to another (Ingold 2016: 156–159).

Night Drawing enables us to reorder linear space and change our worldview by encouraging a departure from our entrenched perception of the illuminated night. Ingold (2016) writes that we inherited from the Enlightenment the idea that light travels in straight lines. However, in this “point-to-point” connection belief, there is no life or movement, and we, therefore, need to return to lines that are more askew, even crisscross, and spectral (Ingold 2016: 155, 157). Night Drawing shifts focus from illuminated objects and substances, referencing the unfolding space in between and the changing appearance of darkness. Its practice leads us to observe and rethink how light might travel in anything but a straight line.

Atmospheric Affects

The material world in which things and people exist is one thing, and the symbolic practices and processes through which representation effects, affects, and produces meaning are another. The design of the urban night through light and its visual affect is central to its spatial impression. Its landscape cannot simply be studied as a traditional model of communication which focuses on questions of signifier/signified and representation (i.e., Hipfl 2018: 8). Rather, we are invited to invert our thinking, to ask what makes certain forms of communication possible. Night Drawing concerns forms of representation evoked by artificial light. The event reveals an opportunity for a different experience, to notice unnoticed atmospheric effects and affects, to renegotiate certain obsessions with urban lighting.[6] (Figure 3)

Figure 3

Night Drawing, Pier 35, New York, 2019

By the term atmosphere, I mean a certain aesthetic experience of the light ambiance that unfolds in urban night space. For instance, light originating from built infrastructure shapes its surroundings but also creates shadows and dark spaces in the immediate vicinity. Night Drawing simultaneously tests light representations as taken for granted and serves to examine the sensed aesthetics of light in the urban night space, akin to what Böhme (2017) describes as the atmospheric architecture of “felt space.” Such an atmosphere can constitute the air between buildings, perceptible but not visible per se. We have seen how the urban nightscape and its various atmospheric light experiences can appear theatrical and thus staged. Housing estate lighting methods were just one example. If we leave aside the practical purposes of light at night for a moment, we are left with questions of aesthetics as atmospheric. Accordingly, the aestheticization of the urban night intersects with political, economic, and social models. Here, again the public is exposed to the phenomenon that arises from urban design but not the criteria that led to it.

Atmospheres are not quantifiable, but they are discernable. These atmospheric properties, which arise in the nocturnal landscape, are often overlooked in the practices of night lighting. This is about what is felt spatially: light resonances that are both visible and invisible; views that require seeing through hue and brightness. Böhme stresses how atmospheres are an important, but neglected component of the built environment. He argues that capitalist forces use urban atmospheres to “tint the field of vision,” writing: “[…] we have to ask whether light as lighting may not be even more important, insofar as it allows us to see the world in a particular way and thereby founds our affective participation in the world.” (Böhme 2017: 156, 202).

Understanding the atmospheric nature of the composition of the urban night and its influence on culture, attitudes, and behaviors is the challenge I want to address. To borrow from Felix Guattari, my response is “to take the everyday infinities and powers of affect very seriously, and to develop a creative responsibility for modes of living as they come into being” (cited by Bertelsen and Murphie 2010: 141). Guattari’s (1995) “ethico-aesthetic” approach to everyday life is essential here as it brings the aesthetic atmosphere—affect and sensation—into the question of practice and experience in everyday life.

Urban planning is an attempt to make “utopias visibly real” (Burckhardt 2012: 38). But it is also an “invisible design […] akin to designs, in that they put their stamp on our lives. One product of this invisible design is the night, man-made night: a temporal environment that is opened and closed in accordance with man-made rules.” (Burckhardt 2012: 188). We may understand how a deeply rooted rationality of light in Western society influences the visual representation of darkness in many ways. But since there are representative limits in dealing with its visible matter and its aesthetic properties, the current understanding of darkness must also be viewed using the frameworks of affect and embodiment.

Building on the groundbreaking work of Brian Massumi (1993) and Elspeth Probyn (2000), the humanities have increasingly come to consider affect as something more than only culturally constructed “feelings” and “emotions,” substantially divorced from the materiality of the body (Gibbs 2002: 337). Massumi makes it clear that affect is more than pathos and sentimentalism. He insists that affect is transversal, and it is everywhere, in effect—it is cultural and political as well as corporeal and even a little mystical: “The ability of affect to produce an economic effect more swiftly and surely than economics itself means that affect is itself a real condition, an intrinsic variable of the late-capitalist system, as infrastructural as a factory” (Massumi 1995: 106–107).

The affect of a visual light effect appears differently up close and at a distance. It is indeed transversal, visible, and invisible, and thus an affective component of everyday life. So, “[w]hat about the sensory production of urban territories?” asks Jean-Paul Thibaud (2015: 39). Can a visual vocabulary, and the drawing gesture itself, contribute to the conversation? Perceiving by drawing may be a way to discover new ways of being and review geographic arrangements (Hawkins 2015: 264). Night Drawing offers a source of comprehensibility for unusual findings but also enables a rearrangement of spatial experiences and night views.

Coming back to Oliveros’ (2015) example of how to listen supports my argument that seeing requires looking and therefore practice. Again, representational models are something we learn, train, and absorb (i.e., Hall 1997). Our experience of aesthetics through the perceived world and the body not only concerns the theatre, the museum, thus paintings, music, sculpture, and so on, but also—as Böhme (2017) claims—architecture, and thus the physical, atmospheric space of the built environment. From this point of view, there is a constitutive aesthetic exchange between the built landscape to be understood as an image and the unfolding atmosphere that shapes its afterimage. Our experience of night atmospheres oscillates between space and non-space,[7] image and simulacrum, light and dark, the familiar and the experienced, leading us back to scenography.

Rethinking habits requires new experiences. I understand Night Drawing as a challenge to rewrite fixed ideas (i.e., an image in mind) as it contests how to understand and visually translate something that is not figurative but noticeable, such as the atmospheric affects of light. The effects of lit atmospheres on the environment, and the fact that a new aesthetic of “urban darkness” arises from its practice, are insufficiently addressed. Drawing at night is a practice, not just to observe what lies in front of you, but to imagine how it comes into being. Actively confronting atmospheres of nocturnal light with a gesture, the practice aims to reconsider certain entrenched attitudes and dogmas with urban nocturnal illumination.

Gesture of Drawing

Night Drawing raises the question: what does the light of the urban night tell us? And how do we talk back? The night may be designed and institutionalized, but through Night Drawing we become active participants in space. We reclaim it with gesture and with our bodies. If writing with light is a practice of architecture in the broader sense, can then rewriting its light setting with pen and pencil challenge ideas of urban aestheticization? Drawing in the dark is not simply intended as a challenge that forces you to see and draw your surroundings afresh, but also as a critical approach to rediscover dark atmospheres and light aesthetics that are representations, in relation to embodied experiences. Drawing requires a more conscious bodily experience, starting from a more unfamiliar vantage point, to create a visual translation that transcends representation. Ultimately, Night Drawing is a gesture, an opportunity to create awareness about what it means to be exposed to light at night. (Figure 4)

Figure 4

Night Drawing, Mile End Park, London, 2018

Night Drawing asks participants to enter the luminous spectacle of the urban night—a kind of theatre—as both an actor and a spectator. Michael Taussig (2011: 22) writes that drawing is like having a conversation with the thing drawn. Drawing, Berger (2005: 116) continues, is an activity with a component of corporeality. Drawing has a “kinaesthetic sense” (Taussig 2011: 23).[8] In this sense, Night Drawing is affective, since it is an active gesture to encourage, study and review how the light affects and reacts to us at night. It is a collective process that takes in various realities. The gesture of drawing explores how the connection of body, architecture, and visual representation affects people’s imaginations and visions. Again, it aims at a critical gesture, an embodied way of moving through the urban night space to engage in different ways with and against established conventions of perception. It is an exploration of an alternative way of knowing, connected to feelings, sensations, and impulses.

The collective aspect of Night Drawing is important. Most would not feel very comfortable drawing alone at night. Participants report that the joint activity makes it possible to remain relaxed in the dark; relating to a party gives a secure feeling while drawing in the urban night. While the Night Drawing events are open to the public and announced and shared on social media platforms, it is clear that my research only investigates a small slice of urban night experiences in London and New York. I am aware that, given the complex social ecologies of the large urban centers within which I am working, this project cannot cover the full range of residents across race, gender, age, class, and ability. It is also clear that urban night in affluent parts of London or New York is very different from that in underprivileged areas, which is in turn different from an urban night in a small rural city, a small industrial city in the north of England, or Shenzhen in China, and so on. Nonetheless, the practice of Night Drawing is far-reaching: it has the potential to include other contexts in the future, deepening intersectional and cross-cultural understanding of the issues involved.

Exploring the night (and especially the dark) in more privileged urban centers like London and New York is also not without its problems and understandably can raise questions about First World problems. These cities are considered urban utopias of bright lighting and often serve as romanticized models for the future of urban planning, politics, and design. Investigating urban night spaces in such cities reveals a visual tension between the imaginary and the real. This ambiguity is shaped by the architecture, urban utopias, Hollywood romances, and the influence of a 24/7 environment (e.g. Crary, 2014). Therefore, there is an urgent need to closely study the problems of urban night lighting related to such supercities, since they serve as exempli for other urban environments of different scales and shapes, as well as for our future citylike thinking.

Night Drawing yields alternative representations, in which the urban night is formed in relation to oneself. It is iterative, accumulating knowledge through experience and re-experience. Night Drawing acts as a challenge to passive attention and indifference by forcing an active gesture of looking back. There is a great need to rethink the matter of darkness in the nocturnal city and therefore to react to it in an ethical-aesthetic paradigm that, as Guattari argues, is linked to a collective, to ingenuity and creativity of thought: “[…] promoting a new aesthetic paradigm involves overthrowing current forms of art as much as those of social life!” (Guattari 1995: 134).

What makes drawing a significant gesture is the experience of doing it, the embodied experience of being on the spot in space; that is, the examination of the attention and contemplation it evokes. Adorno saw gestures as opportunities that afford the body a certain awareness and knowledge of itself (Noland and Ness 2008: ix–x).[9] Merleau-Ponty insists that the “body-world relationship” is a “contact surface” rather than a hard boundary. The gestures that structure our environment merge with our bodily experiences. (Merleau-Ponty 2005: 186). The gesture of drawing at night reacts actively to this and opposes the gesture of urban light practice. In this sense, Night Drawing is a gesture of the gesture; we can call it a re-gesture that explores the gesture of those who built the light at night.

The method of drawing is pivotal to the passivity that Simmel (2010: 105–106) describes as “blasé”. The recognition that certain spatial qualities are available but not always visually apparent reflects Merleau-Ponty’s (2005) writings on the Phenomenology of Perception as well as Juhani Pallasmaa’s (2016) interest in the multisensory perception of space by the human body. “Sight may be failing us,” notes Andrew Causey, but through drawing exercises, we can challenge the casual gaze of simply perceiving what we already know (Causey 2017: 2, 12).

Drawing at night is not easy. It is surprisingly hard, in my own experience, and confirmed by feedback from participants. Why? Dimly lit spaces make it difficult to see precise contours, forms, and shadows. The lighting conditions of the urban night environment contradict sights familiar to us during the day. Transcribing the space that we apprehend onto paper requires imagination and re-imagination. At the same time, it requires relinquishing fixed ideas of how something should look. The rather dark nocturnal environment diminishes the participants’ expectation of an accurate representation. The darkness helps to focus on the visible and not on the visual, the drawing itself. At the same time, the night setting is liberating because the difficult light circumstance somehow excuses the outcome. It becomes a personal engagement that cannot be judged precisely because it is not a photograph.

“[P]hotography is a taking, the drawing a making […]” (Taussig 2011: 21). According to Taussig, drawing intervenes with reality in ways photography or writing do not; drawing operates its own reality with an imprint of the senses. (Taussig 2011: 12, 18). The gesture gives voice to what, how, and where we can experience different levels of light, including atmospheres of darkness and their aesthetics in nocturnal space. However, it also expresses how our perception is shaped and biased. The artist Denzil Forrester, who practices the method of drawing in nightclubs, notes that one of the greatest challenges of drawing is to free yourself from what you see, the picture in your head, and attend to what you feel (Henriques 2019).[10]

Kimon Nicolaïdes explains that drawing is “really a matter of learning to see” and includes all the senses. The difficulty is not in the ability to draw but in our lack of understanding. (Nicolaïdes 1975: 2–5). The goal of Night Drawing is an impulse for a gesture to break out of socially programmed habits of commercially ready-made perceptions of the urban night (i.e., postcard vision) and instead encourage a reinterpretation of what can and cannot be seen at night.[11] Drawing creates awareness that something always remains present but out of sight.

Marks on Paper

The emphasis of Night Drawing is on practice, not product, and the drawings are not the primary outputs of my research. As Nicolaïdes (1975) notes, drawing means looking at people and objects to acquire knowledge. I do not view drawing as aestheticization nor do I focus on technique or attempt to copy the world in an artifact. Night Drawing is an act of physical contact between the internal world and the external world through embodied experience and observation in situ. It allows us to better understand spatial dimensions, navigate space as well as demonstrate the complexity of perception. Next, I will use a few examples to reflect on the interplay between the built world and the participants’ marks on paper. I do not aim for a visual analysis of the drawings. Rather, the idea is to link critical reflections and debates about mediated space, visual communication, and social experiences within the framework of some drawings. I aim to further discuss how our eyes are trained, how our visual understandings are formed, and how drawing may or may not result in dis-habituating us from our ordinary perception-conception of the dark. (Figure 5)

Figure 5

Night Drawing, Mile End Park, London, 2018

As discussed, the difficult circumstances of drawing in an unfamiliar light environment can be beneficial precisely because the sensory perception of time and space is enhanced, offering a new outlook. The making of a drawing is key, as it involves discovering things that usually go unnoticed. It is a method to perceive what is and what is not perceptible in space and to see and look at it in different ways. It creates awareness, sharpens vision, and challenges a familiar viewpoint by exposing oneself to a rather unfamiliar setting. At the same time, however, some drawings clearly show how strongly our visual ideas are cultivated and shaped by external influences (i.e., Hall 1997; Oliveros 2015). In that regard, the perception of night space through drawing acts and re-enacts the form and content. It examines what is and what is not possessable and recognizable.

Night Drawing’s query is to escape the viewer’s prioritization of the visual outcome. For a long time, I avoided giving the participants any drawing instructions. Over time, I kept noticing almost desperate questions about how-to, mainly caused by the frustration of some participants with their drawings. Often the problem for some is that the drawing appears too abstract and is perceived as not realistic enough. What can be considered a good or bad drawing is another challenge Night Drawing addresses. Berger is of great help here when he states: “To draw is to look, a drawing of a tree shows not a tree, but a tree being looked at.” (Berger 1976: 82). However, even after years of running the public workshops, it’s a challenge to convince some participants that the idea of Night Drawing is not to present the urban night exactly as it appears (whatever that might mean), and nonetheless, we sketch what we know: drawers often try to reproduce the environment as they experience it in daylight. (Figure 6)

Figure 6

Night Drawing Sketch, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, London, 2018

One technique assisting a shift in focus is to use a white pen on black paper. It is more difficult to draw the dark (what is in the shadow) than to draw the brightness (what is in the light). What struck me from multiple experiences is that viewing habits seem more biased towards brightness. To make the effort of focusing on the darkness and not on the light demands a negation. Many have expressed that the application of a white pencil on a black page is more satisfactory since the inverted result yields a more accurate representation of what they think they see. They claim that the relationship between dark and light appears less wrong and more nocturnal. (Figure 7)

Figure 7

Night Drawing Sketch, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, London, 2018

Another exercise instructs the participants to draw everything that appears in variations of black or white. In other words, the instruction is to transfer only bright or dark spots onto paper. It is a simple task that can help investigate the representation of urban night light by observing its source. Light facilitates orientation, for example, by supporting the perception of proximity and distance or separating the background from the foreground. The latter is one of the first things that happens when observing and translating a nightscape either into black or white. It is a simplification through light and dark, a visual orientation that notates the environment on paper. It purposely takes black or white as a reference point to represent space, focusing on form and contrast. This reduction of visual complexity makes the ambient light impressions less overwhelming and helps to ease the creator’s dissatisfaction. (Figure 8)

Figure 8

Night Drawing Sketches, done by various participants at a Night Drawing event, New York, 2021

Although the exercises attempt to shift the focus from the drawing itself to observation, I still discover some sort of correction occurring in some drawing results. For example, it is not uncommon to add symbolic information to the drawing, such as stars, or drawings that follow the look of a postcard or mimic a poster photograph. This observation is crucial to visual thinking and the design of our living space precisely because it reflects how imagery is somehow formed and copied by what we have seen and taught before. Colomina (2000), as well as Sharpe (2008), write about how images of modern architecture in two-dimensional media (such as magazines or artworks) foreshadow and shape our imagination of the modern built environment. Likewise, our ideological, socio-cultural understanding of the night prefigures and forges our experience and the corresponding handling of darkness in the environment. (Figure 9)

Figure 9

Night Drawing Sketches, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, New York, 2021

However, some sketches also express something else, namely the individual perception of light through effect and affect, and in doing so reveal their experience of the atmosphere. In other words, some drawings become more spherical, more abstract, less figurative, and representative. In this way, spatial representation, experience, and the participants’ visual preconceptions collide. Our vision is ambiguous—as W. J. T. Mitchell reminds us, “[w]hat we see, and the manner in which we come to see it, is not simply part of a natural ability” (Mitchell 2002: 170). In sum, Night Drawing intentionally challenges the gap between what the drawing person thinks they see and what they can translate on paper. This possibility of perception challenges the accuracy of the representation and is in fact an advantage: it reveals the unfamiliar at the limits of perception. Here the matter of darkness, its urban presentation, and our perception of it help us further understand how we have come to see and reveal its shortcomings. (Figure 10)

Figure 10

Night Drawing Sketch, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, London, 2018

Conclusion

I have shown how a visual representation in the form of a drawing can overlap with an image idea and a spatial experience. Seeing through drawing intersects with changing perspectives; social, political, and practical needs; and, ultimately, with changing notions of individual subjectivity. Observing patterns of light at night through drawing is a technique that helps to investigate how areas of light and darkness mutually form. Night Drawing addresses contemporary perceptual challenges and explores how drawing in the night environment operates as a form of translation of our perception. The method offers a laboratory for the investigation of natural forces of darkness in conjunction with artificial light, its creation of “urban darkness,” modes of representation, and views impacting metropolitan night lifestyles. Hence, the approach encourages a rethinking of the brightly lit world that affects space and us. (Figure 11)

Figure 11

Night Drawing event, Pier 35, New York, 2019

To see the light at night anew and to renegotiate understandings of the matter with darkness, it seems necessary to break with entrenched ideas and customs. Thus, it is crucial to understand how light creates atmospheric affects beyond its shine effect. A city’s inhabitants must critically question bright nocturnal displays presenting their cityscape like a postcard. The same applies to city-political ambitions for light and security. Drawing at night can remove some perceptual limitations at the same time as creating new ones. Ultimately, what is important is the question of kinaesthetic epistemology: how do we acquire knowledge via drawing? Drawing requires close looking; it is an active embodied process of seeing and perceiving. This idea is to be extended to future urban night lighting ideas and practices as well as to more general questions regarding spatial aesthetic experiences. Aesthetic experiences—an embodied act as well as a poetic encounter with the matter of light at night—have ethical, ecological, and political implications.

The visual representation of the future urban night is a pressing issue. It is crucial to deal with further questions of lighting planning, new political alternatives, and new intellectual challenges to tackle the nocturnal living space. We need to further unpack the fear, sense of danger, and other prejudices that have made us averse to darkness. In addition, it is important to keep reminding ourselves that illumination is also an issue of climate change and a social matter of equal access and global distribution of resources. In sum, Night Drawing investigates how the light at night speaks to us in the form of visual communication, to call into question beliefs around darkness, and conventions of urban design that lead to its visual representation. Thus, for a new idea of the dark, light must first and foremost be rewritten—and not in a straight line.

I am not suggesting that there should be less activity at night. Rather, we must redefine our lives in and with dark atmospheres to question the habits of overexposure to artificial light. In addition to a simple rediscovery of darkness, a re-vision and re-construction of dark aesthetics and atmospheres are needed. I thus suggest that we both attend to and engage with darkness rather than seeking to eliminate it by illuminating it. This should not prove to be an impossible task.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

See Noam Elcott’s (2016) history on the use of Artificial Darkness in movement and body science, and the use of the dark effect for entertainment used in photography, film, and theatre.

- [2]

-

[3]

See also Nadia Hallgren’s film Omnipresence (2021), which reflects New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s “Omnipresence” initiative and tells the story of floodlights from the resident perspective living in a Bronx housing project.

-

[4]

Modes of habitual perception, distinctions between “seeing” and “looking”, and active/passive cognition are also discussed by Arnheim (1969); Berger (2008); Gibson (2015). It is worth noting a further distinction in ways of seeing: Ariella Azoulay, in The Civil Contract of Photography (2008), distinguishes between looking and watching, arguing that we have a duty to watch rather than to look at images of violent conflict. While her distinction is instructive for my work, her call to watch applies not only to photography but to visual representation in general. Azoulay (2008) asks the viewer to reconstruct the scene from which the photo is taken. This refers to the process of Night Drawing, which observes the nocturnal light environment not as a spectator but as a participant.

- [5]

-

[6]

The history of prejudices about safety at night on the one hand and control on the other is relevant here. See for example Sandy Isenstadt’s (2018) argument about the synonymous artificial light that changed the perception of space, as well as Mike Riggs’s debate of lights and crime, and the philosophical reflections on Western ideas of light and sight by Hans Blumenberg (2020) or Cathryn Vasselau (2002).

-

[7]

See also Marc Augé’s (2008) on “non-space” reflecting on places that we only partially and incoherently perceive.

-

[8]

See also Zeynep Çelik Alexander on “kinaesthetic knowledge” as a subject of research dating back to 1906, although marginalized in the 20th century, it continued to be used “by those seeking to critique the centrality of the mind in Western intellectual life.” (Alexander 2017: 1, 25-26, 100).

-

[9]

See also the extensive records of historical transformations (human and animal) in Gesture and Speech by André Leroi-Gourhan (2018), in particular the changes in human work practices after 1920, and thoughts of rationalism through cognitive and communicative examples between body and work, manual and technical.

-

[10]

In his series Blind Time, Robert Morris addresses this difficulty by giving himself the task of drawing with his eyes closed. Like the Surrealist’s techniques of automatism, the hand is said to liberate conscious thought and visual guidance (van Alphen 2012: 61).

-

[11]

See also the chapter “Recording: And Questions of Accuracy” by Stephen Farthing in Writing on Drawing : Essays on Drawing Practice and Research (Garner 2012: 141–152).

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the Stuart Hall Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation. I also thank Lucy Parakhina, Macushla Robinson, and Michael Hassin for their helpful comments and edits throughout the text. All errors and omissions remain my own of course. Finally, a big thank you goes to all Night Drawing participants!

References

- Alexander, Zeynep Çelik. 2017. Kinaesthetic Knowing: Aesthetics, Epistemology, Modern Design. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Anon. n.d. “What We Do – Configuring Light.” Configuring Light, on line: http://www.configuringlight.org/what-we-do/.

- Arnheim, Rudolf. 1969. Visual Thinking. 35. anniversary print., [5. print.]. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. 1st pbk. ed. New York : Cambridge: Zone Books.

- Berger, John. 1969. “Drawing.” In Permanent Red: Essays in Seeing : 23–30. London: Methuen.

- Berger, John. 1976. “Arts in Society: Drawn to That Moment.” New Society 37(718): 81.

- Berger, John. 2008. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

- Berger, John. 2020. “Steps towards a Small Theory of the Visible.” In Steps towards a small theory of the visible: 76–89. London: Penguin.

- Bertelsen, Lone and Andrew Murphie. 2010. “An Ethics of Everyday Infinities and Powers: Félix Guattari on Affect and the Refrain.” In Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth (eds.), The Affect Theory Reader: 138–157. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bille, Mikkel and Tim Flohr Sørensen. 2007. “An Anthropology of Luminosity: The Agency of Light.” Journal of Material Culture 12(3): 263–284.

- Blumenberg, Hans. 2020. “Light as a Metaphor for Truth: At the Preliminary Stage of Philosophical Concept Formation.” In D. M. Levin (ed.), History, Metaphors, Fables: 129–169. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Böhme, Gernot. 2000. “Acoustic Atmospheres: A Contribution to the Study of Ecological Aesthetics.” Soundscape 1: 14–18.

- Böhme, Gernot. 2017. Atmospheric Architectures: The Aesthetics of Felt Spaces. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Burckhardt, Lucius. 2012. Rethinking Man-Made Environments: Politics, Landscapes & Design. Wien and New York: Springer.

- Causey, Andrew. 2017. Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method. North York, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Colomina, Beatriz. 2000. Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Crary, Jonathan. 2014. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso.

- Cubitt, Sean. 2014. The Practice of Light: A Genealogy of Visual Technologies from Prints to Pixels. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Edensor, Tim. 2017. From Light to Dark: Daylight, Illumination, and Gloom. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Elcott, Noam Milgrom. 2016. Artificial Darkness: An Obscure History of Modern Art and Media. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Entwistle, Joanne and Don Slater. 2019. “Making Space for ‘the Social’: Connecting Sociology and Professional Practices in Urban Lighting Design.” The British Journal of Sociology 70(5): 2020–2041.

- Farthing, Stephen. 2012. “Recording: And Questions of Accuracy.” In Steve Garner (ed.), Writing on drawing: essays on drawing practice and research, 141–152. Bristol: Intellect.

- Garner, Steve (ed.). 2012. Writing on Drawing: Essays on Drawing Practice and Research. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gehl, Jan. 2011. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Gibbs, Anna. 2002. “Disaffected.” Continuum 16(3): 335–341.

- Gibson, James J. 2015. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York and London: Psychology Press.

- Guattari, Félix. 1995. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. Representation : Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: SAGE.

- Hallgren, Nadia. 2021. Omnipresence.

- Hawkins, Harriet. 2015. “Creative Geographic Methods: Knowing, Representing, Intervening. On Composing Place and Page.” Cultural Geographies 22(2): 247–268.

- Henriques, Julian. 2019. Denzil’s Dance.

- Hipfl, Brigitte. 2018. “Affect in Media and Communication Studies: Potentials and Assemblages.” Media and Communication 6(3):5.

- Howes, David. 2005. “Architecture of the Senses.” In Mirko Zardini (ed.), Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism: 322–331. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture = Centre canadien d’architecture.

- Ingold, Tim. 2016. Lines: A Brief History. London and New York: Routledge.

- Isenstadt, Sandy. 2018. Electric Light: An Architectural History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Jacobs, Jane. 1992. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

- Martin, Reinhold. 2016. The Urban Apparatus: Mediapolitics and the City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Massumi, Brian. 1995. “The Autonomy of Affect.” Cultural Critique 31: 83–109.

- Mattern, Shannon. 2021. A City Is Not a Computer: Other Urban Intelligences. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- McQuire, Scott. 2005. “Immaterial Architectures: Urban Space and Electric Light.” Space and Culture 8(2): 126–140.

- Meng, Chantal. Forthcoming. Light at Night: What Is the Matter with Darkness? PhD thesis. Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2005. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 2002. Landscape and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nicolaïdes, Kimon. 1975. The Natural Way to Draw: A Working Plan for Art Study. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Noë, Alva. 2004. Action in Perception. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Noland, Carrie, and Sally Ann Ness (eds.). 2008. Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Oliveros, Pauline. 2015. “The Difference between Hearing and Listening,” December 11.

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2016. “The Sixth Sense: The Meaning of Atmosphere and Mood.” Architectural Design 86(6): 126–133.

- Probyn, Elspeth. 2000. Carnal Appetites: Foodsexidentities. London; New York: Routledge.

- Riggs, Mike. 2014. “Street Lights and Crime: A Seemingly Endless Debate.” CityLab, February 12, on line: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-02-12/street-lights-and-crime-a-seemingly-endless-debate.

- Sassen, Saskia. 2001. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. 1995. Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sharpe, William. 2008. New York Nocturne: The City after Dark in Literature, Painting, and Photography, 1850-1950. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Simmel, Georg. 2010. “The Metropolis and Mental Life.” In Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (eds.), The Blackwell City Reader: 103–110. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Slater, Don. 2017. “How Lighting Affects the Way We Perceive, Use and Live in Our Communities Is at the Heart of the Configuring Light Research Programme.” The Lighting Journal 82(2): 30–33.

- Taussig, Michael T. 2011. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Thibaud, Jean-Paul. 2015. “The Backstage of Urban Ambiances: When Atmospheres Pervade Everyday Experience.” Emotion, Space and Society 15: 39–46.

- Vasseleu, Cathryn. 2002. Textures of Light: Vision and Touch in Irigaray, Levinas, and Merleau-Ponty. London and New York: Routledge.

- van Alphen, Ernst. 2012. “Looking at Drawing: Theoretical Distinctions and Their Usefulness.” In Steve Garner (ed.), Writing on Drawing: Essays on Drawing Practice and Research: 59-70. London and New York: Routledge.

- Whyte, William H. 1988. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Direct Cinema Limited USA.

- Zumthor, Peter. 2006. Thinking Architecture. Basel and Boston: Birkhäuser.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Night Drawing, Pier 35, New York, 2019

Figure 2

Night Drawing, Brooklyn Bridge Park, New York, 2021

Figure 3

Night Drawing, Pier 35, New York, 2019

Figure 4

Night Drawing, Mile End Park, London, 2018

Figure 5

Night Drawing, Mile End Park, London, 2018

Figure 6

Night Drawing Sketch, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, London, 2018

Figure 7

Night Drawing Sketch, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, London, 2018

Figure 8

Night Drawing Sketches, done by various participants at a Night Drawing event, New York, 2021

Figure 9

Night Drawing Sketches, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, New York, 2021

Figure 10

Night Drawing Sketch, done by a participant at a Night Drawing event, London, 2018

Figure 11

Night Drawing event, Pier 35, New York, 2019