Résumés

Abstract

Ethnochoreologists are now more open to the study of folk dance revival groups, though they still lack common terminology or conceptual frameworks. Based upon the motivations and priorities of their participants, dance groups can be identified as “Enjoyers,” “Preservers,” “Presenters,” “Creators,” or perhaps “All-stars.” Several examples show how each of these strategies may impact on the organizational structures, dance forms and other aspects of the groups’ activities. These conceptual categories are presented with the suggestion that they may be useful for researchers, government policymakers, and dance group leaders.

Résumé

Les ethnochorégraphes sont désormais plus ouverts à l’étude des groupes de danseurs qui font renaître les danses folkloriques, même si la terminologie courante ou les cadres conceptuels leur font toujours défaut. Basés sur les motivations et les priorités de leurs participants, les groupes de danseurs peuvent être identifiés comme « ceux qui prennent du plaisir », « ceux qui préservent », « ceux qui donnent à voir », « ceux qui créent » ou encore « les vedettes en tout ». Plusieurs exemples montrent comment chacune de ces stratégies peut influencer les structures organisationnelles, les danses et d’autres aspects des activités de ces groupes. Ces catégories conceptuelles sont présentées avec l’idée qu’elles pourraient être utiles aux chercheurs, aux législateurs ainsi qu’aux représentants de groupes de danseurs.

Corps de l’article

Folk dances have been recreated in non-peasant settings for several centuries.[1] Ethnochoreologists have been describing this phenomenon for a fairly long time (Crum 1961; Hoerburger 1968; Dunin and Zebec 2001: 133-271; and many others), but no broadly shared terminology or set of concepts has taken hold. In this article, I suggest it may be useful to look at folk dance revival communities as “enjoyers,” “preservers,” “presenters,” “creators,” and/or “all-stars.” This article is not primarily an ethnography, although I make use of several decades of experience observing diverse folk dance groups in Canada and abroad.

I propose to use the term “revival” broadly to describe any dancing activity in which the participants actively invoke past performances of the dance (Nahachewsky 2001a: 19-22). I propose the term “vival” dance to describe any dancing in which the participants are focused specifically on the moment of performance, with no significant orientation to the past. Vival and re-vival dance can be imagined as contrasting poles on a broad continuum.

A glance at international ethnochoreological bibliographies (Dunin 1989, 1991, 1995, 1999; Zebec 2003) indicates that scholars in this discipline have tended to focus on vival dance more than on revival. A glance at Canadian dance research also reveals a number of studies of traditional vernacular activity that matches our concept of vival dance (see Séguin 1986; Quigley 1985; Nahachewsky 2001c). However, especially if we look at unpublished works such as theses and dissertations, we see that a large proportion of studies describe revival activities.[2] This emphasis on revival may be because revival activity is more visible and accessible, and many Canadians do not think of themselves as having active folk traditions.

In Canada, with the exception of social dancing, there is little survival folk dancing; it is difficult to determine precisely the amount of survival dancing that remains. However, it is found among relatively isolated (geographically or psychologically) communities such as native peoples and in francophone and Hassidic cultures. Urban-based minority groups such as Indian, Chinese, Italian, Portuguese, Ukrainian, Macedonian, Greek, Polish, German, Armenian, Irish, Latin-American and West Indian may have retained some of the dances unique to their regional origins. But as first — and second — generation immigrants die off, third and subsequent generations tend to assimilate into mainstream society, and with them go the dances which were once an important part of their social, occupational or religious spheres.

Revival dances are more frequent and more visible. They are especially noticeable among groups who have strong feelings for their ethnic roots. One way to preserve, express and perpetuate this sentiment is to perform “national” or “ethnic” dances. Dances may be acquired either when older group members recall dances from the past, or when an outside expert is summoned to teach the dance. The dances are then “set” for the group, which enjoys dancing them on suitable occasions.[3]

Shifrin 2006

One of several challenges to developing a common set of concepts associated with dance revival is the frequent dissonance between emic (insider) perspectives and etic (more cross-cultural analytical) perspectives. In some cases, the insiders may claim strong continuity with past dance forms, while outsiders may see great changes over time. Conversely, in some cases, a particular dancer may feel wholly engaged in the dancing “here and now” at a specific event, though a researcher can observe that her community in general has a clear orientation to the past.

Tamara Livingston (1999) and others have tried to identify cross-cultural characteristics of music and dance revivals. I have argued that it is useful for researchers to differentiate “national,” “recreational/educational,” and “spectacular” dance revivals as etic categories based on the primary motivation of the community members (Nahachewsky 1997; 2001b; 2006). Reflecting the primary motivation for any community, each of these three main orientations has important implications for the values, organizational structure, dance forms and the day-to-day choices made by the community’s leaders.

The goal of this article, however, is to explore a different series of categories developed from these concepts that might differentiate one folk dance revival community from another. These concepts hopefully connect with emic perspectives more intuitively. I hope these concepts will be useful for scholars observing the variety of activities and organizational profiles of folk dance groups. This article also has an “applied” element, as it may allow leaders of folk dance groups to more clearly identify their priorities. They are encouraged to think critically about which of their practices reflect their motivations best.

Four and a Half Strategies for Success

I’d like to suggest four-and-a-half different strategies for folk dance groups and their leaders, to see how they prioritize a variety of different values in practice. I propose a name for each strategy based on the most important motivation in their community: Enjoyers, Preservers, Presenters, Creators and All-stars. Each of these strategies has been employed by folk dance groups in Canada, and other strategies are also possible.

Figure 1

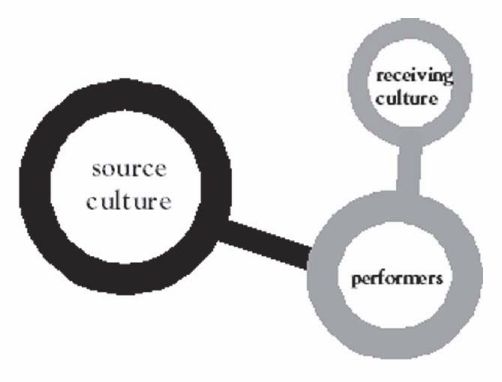

A variation of the following diagram will be presented for each strategy, representing three subgroups that are typically involved in folk dance events: the people in the source culture, the performers themselves, and the people in the receiving culture (spectators).[4] In folk dance revivals and ethnic dance in general, the dance event necessarily involves engagement with cultural boundaries, and these boundaries are typically experienced at the interfaces among these subgroups. In some cases, the identities of the people in each category are the same. In other cases, the source culture, performer’s culture and receiving culture are each quite distinct.

Enjoyers. “it feels good”

Figure 2

To illustrate the “Enjoyers” strategy with a diagram, the performers’ balloon is drawn large and dark because the focus of the performers is centred on themselves and their own experience. Enjoyment is the main priority. They do have a relationship with the source culture, but dances can be fun whether they are authentic or not. Enjoyers may derive their material from one specific source culture or more than one. Likewise, if there is an outside audience at all, spectators are only a secondary concern for the “Enjoyers.” Enjoyer dance groups are primarily recreational in function, and the quality of the physical experience and the social interaction outweighs other considerations when there is a choice to be made.

Preservers. “Keep the Tradition!”

Figure 3

“Preservers” are people whose primary reason for dancing is to honour the source culture. They are interested in delving back, as far as possible, to find the most archaic, most traditional, most authentic information available within the source culture. The earlier culture is beautiful, and has much to offer in healing some of the ills of today’s society. Preservers want to reconstruct that original material and keep it alive. They are conscious of their own activity in the contemporary setting, and of the presence of the receiving culture, but see these elements mostly as a conduit for the preservation of the dance treasure.

The original peasant setting is foremost in their minds. Preservers often dedicate years, perhaps a whole lifetime, delving into the original cultural content to flesh it out and resonate with its subtleties as much as they can. They may hold fast to their commitment to preserve the dance even when it requires great sacrifice. The most dedicated Preservers generally devote themselves to one particular culture for long periods of time, perhaps for their whole career. Many Preservers identify themselves ancestrally with the source culture, though some get involved outside their own heritage. Many are as interested in the spiritual aspects of the source culture as much as in its kinetic aspects.

Presenters. “Communicating Our Identity!”

Figure 4

“Presenters” represent a third strategy for engaging in folk dance. As in the previous strategy, the performers often dance their own ancestry. They are part of it, and want to present this culture to the broader world to give it a higher profile. Dance is a vehicle to popularize that source culture. Some Presenters are also Preservers, though not necessarily so: cultural identity may be symbolized in authentic forms, but also in contemporary style. Contemporary styling may be seen to have the advantage of resonating more deeply with their current audiences. Since many Presenters know the source culture from the inside, and feel quite secure in that culture, they may feel comfortable participating in its growth; improvising and being creative within the bounds of the tradition.

Creators. “I’m Inspired!”

Figure 5

Individuals and groups who are “Creators” are primarily interested in creating expressive dance within the realm of the receiving culture. They see themselves as artists within the receiving culture. As artists, they are somewhat special, perhaps, with a wide palette for inspiration. Some of their inspiration may come from beyond their own contemporary culture, and they may choose to engage in folk dance for some of their work. Such Creators may select their materials from a wide range of source cultures. Whatever larger or smaller bits of such materials they choose to use, they generally mold them to the needs of their own larger project. They adopt and adapt the raw folk material for use in their own, new cultural context.

These four strategies are proposed as models, and many groups fit these patterns well. Hybrids of these strategies are possible, and some groups set their sights on two different strategies and try to fulfill both sets of goals equally. This is a more difficult task, but I have seen some groups operate in this way with success. They may be “preserver-presenters,” “enjoyer-presenters” or perhaps “presenter-creators.” These seem to be the most common combinations. What is less likely, however, is a “preserver-creator,” because the goals of these two strategies are perhaps too opposite each other. In some cases, these different strategies might be employed alternately, either at different dance events, or perhaps for strongly contrasting pieces within one performing event.

All-stars. “I Can Do It All!”

Figure 6

The “All-star” strategy is chosen by performers who want to succeed in all of the above strategies at once. They see themselves as reflecting and expressing the source culture very well, while simultaneously being successful eclectic creative artists, and also performing material that is fully accessible to contemporary mainstream audiences. This Allstar strategy might be seen as the best model for a leader to follow in cases where the individual participants of a given group have very diverse motivations. Using this strategy allows everyone to get at least some satisfaction, no matter what they expect out of the dance experience. Allstars can be seen as “Jacks-of-all-trades.”

The negative side of this strategy corresponds to a proverbial expression attached to this name: “Jack of all trades, master of none.” The difficulty in this strategy is to channel the original cultural material richly through the performers’ interpretive processes and to engage the spectators profoundly without watering the dances down in the process. In order to really reflect the source culture and qualify for the All-star profile, one needs to have knowledge of the source dance cultures on a deep level. In most cases, the physical setting of a given performance venue tends to level out the subtle differences too strongly. I present all the balloons in the illustration above in a lighter shade of gray to reflect my experience that performers who try to do everything at once tend to do it all rather weakly.

Most often, the All-star strategy is used by people who are interested in a light sampling of the experience of folk or ethnic dance. This profile serves as a bit of a smorgasbord, a sampler of many aspects of the activity. In other cases, the All-star strategy is chosen by people with a strong desire to engage seriously in ethnic dance, but without the critical insights or experience to fine tune their strategies more specifically. After all, to take on one of the previous strategies means to consciously let go of one or more potential values in the dance. That person has to admit to her/himself that there are some potential aspects of the activity that s/he is NOT going to focus on.

For those people, I offer the analogy of buying a vehicle. We all know the difference between a sports car, a family minivan and a pickup truck. Sports cars are best if we place a high priority on quick acceleration, driving very fast, and on impressing people with this stylish and high-status symbol. Minivans are not particularly stylish, but much more useful for transporting people and varied cargo. They often have smaller engines for better fuel economy in the city. Pickup trucks generally have stronger motors for pulling heavy, large and dirty loads over rough terrain. North Americans generally appreciate these specialized strategies in vehicle design, and appreciate that each type of vehicle performs quite poorly in the tasks that it is not designed for. We tend to be able to assess our needs accurately when planning to buy a vehicle. Few people would buy a composite vehicle with a small sleek body of a sports car, the small engine of a minivan, and strong suspension of a pickup. It would be a useless, mixed up vehicle that does not work well but still costs a lot.[5]

I think this analogy is quite useful for leaders of folk dance groups, because many people inherit bits and pieces from various traditions as they dance along. Resources are often scarce. Many dance groups, then, are like home-built vehicles made of spare parts. The general impression that “authenticity is good” often leads to conservative instincts in leading a dance group. The result is often strongly blended activities which counterproductively pull our efforts in opposing directions. It may be surprising to see how many dance groups operate as a composite sports-car-minivan-pickup.

Forrest City Morris Dancers

Pauline Greenhill describes at length the interests and motivations of various dancers in one Morris dance group in Ontario (1994). Her description may serve as an illustration to show how the different strategies have practical implications. Some of the dancers in the Forrest City Morris Dancers are interested in upholding the worthy tradition of Morris dance, performing the dances correctly. They and others may be quite interested in the mythic connection between Morris and ancient fertility rites and the spiritual subculture connected with such rites in contemporary society. Some are primarily interested in the social aspect of their participation in Morris, the recreation offered during practices, at Ales (larger Morris gatherings) and other activities with their friends. Others are particularly attracted by the physical aspect of Morris dance, as it offers them a chance to keep fit. Still others are motivated by the sense of local pride, and would place a high priority on Forrest City Morris Dancers showing well in comparison with other groups. Another subgroup is quite interested in the aspect of spectacle. For them, the most satisfying moments are when the side performs with perfect unity and high energy, and when they know they have really pleased an audience. Other motivations are involved as well.

Using the profiles we have identified above, we see that some of the participants want the group to operate as Preservers (uphold tradition), others as Enjoyers (socializing and recreation), others as Presenters (impress their audience). There are only weak tendencies towards the strategy of Creators.

In its day-to-day operations, the Forrest City Morris Dance Club can be seen to be made strong by the diversity of interests of its members, because each contributes his or her own insights and values. Therefore, everyone has a multidimensional experience as they come into contact with their teammates’ diverse actions and interests and comments.

These diverse interests, however, may also be sources of tension and conflict in the group. For example, if the leader is a very strong Preserver, then he will probably tend to steer away from including women as performers. Morris dance was traditionally performed by men. That is sometimes a source of conflict because those participants with a strong focus on the social dimension will argue that women participants should be welcomed given our society’s general tendency towards more equality. Many team leaders have found themselves on the horns of this dilemma, and needed to consider their own priorities, the motivations of the potential dancers and the cultural norms of their particular community. If, however, there are an insufficient number of interested males to fill a side, the Preserver strategy is probably not viable whether the leader wishes it or not.

Similarly, people interested in the spiritual aspect of the fertility rituals may be interested in introducing other aspects of neo-pagan culture into the team’s activities, spreading their commitment of time and energy to these pursuits as well as to the dance. They may be interested in performing mostly during the summer and winter solstice, as well as other astronomically significant times. Dancers interested in physical fitness, however, are much more likely to want to dance regularly all year round. Dancers with a strong motivation for high standards in performance may become frustrated with those more interested in simply having fun.

The Forrest City Morris team does seem to enjoy a degree of success in its activities and does seem to have found a stable balance between the various interests of its members. Other Morris teams in North America and the United Kingdom choose to commit themselves to a different balance of their members’ priorities. Some Morris teams are strong Preservers, placing high priority on reconstructing the earlier forms to the greatest degree possible. Others are more committed to the strategy of Enjoyers, and may develop a more intense focus on the activities after the performance than during the dance itself. Among the Morris dance teams committed to the strategy of Presenters, many focus on unison and energy in the performance as well as local pride. As we see, the question of, “what is good Morris dance?” has many different answers.

Character Curriculum

A second example illustrates how the different strategies may have implications on a more microscopic level. Imagine that a character dance teacher is establishing a new curriculum for her growing dance school. In selecting the exercises for the various levels, and specifically in deciding what to call the various movements, the teacher might well make decisions that relate to the various strategies we have spoken about.

Our teacher wishes to introduce an exercise where the beginner dancers stand in ballet first position, then turn their legs inward, then outward again repeatedly. If they shift their weight from the balls of their feet to the heels in a certain way, they will gradually travel sideways. This step is good for coordination, as well as for isolating and strengthening the muscles that turn the legs in and out at the hip socket.

Figure 7

The teacher may choose to refer to the step as pas tortillé, adopting the ballet term for it in French. Alternately, she may choose to call it garmoshka, the name for this well-known movement in the Russian character dance tradition. On the other hand, she may decide to call it the “accordion” step, which is a translation from the Russian into English.

The various strategies for folk dance may well have an impact on what name the teacher chooses to use. People who are primarily interested in the Enjoyer strategy may choose to teach character dance technique informally. In these cases, the word “accordion” might be most suitable because it is easier for the children to remember, and it communicates the zigzag feeling evocatively. The word “accordion” might also be used by a Creator strategist. On the other hand, accordions are no longer very common in contemporary children’s culture in North America, and the Enjoyer or Creator may chose to make up a name more relevant to the children. “Robot shuffle” might be more expressive for them (and might also remind them to keep the rest of their bodies immobile). In contrast to the Creator’s mindset, a Presenter or Preserver might be less worried by the accordion’s old world connotations. In fact, they may actually be pleased by them, and would therefore reject “robot shuffle” as unnecessarily anti-traditional. Indeed, the non-English terms may be most attractive to the Preserver. If the teacher is presenting the character dance materials firmly within a ballet tradition, and wants to highlight that fact to her students, then “pas tortillé” may be the best choice.

“Garmoshka” is the best choice for the Preserver who wants to emphasize the great developments in Russian character and folk staged dance traditions. “Garmoshka” may also be the term of choice for a person who grew up in Eastern Europe and wants to emphasize this to her students. It may also be attractive to a Presenter who likes the exotic sound of the Russian word, thus subtly reminding the students about the international flavours of dance.

Though the differences between these options may appear subtle, they do have their implications. A teacher with clear priorities may choose terminology to consistently reinforce her particular worldview in her students. By contrast, other teachers may allow a mixed terminology, revealing how tradition tends to be transmitted somewhat uncritically from generation to generation (Pagels 1984).

In both of these examples, there exists some tension between the urge to work as a generalist All-star and the desire to be a specialist, favouring another of the defined strategies. Many other examples could be presented to show how the specific strategies may influence the practices of folk dance revival groups. Even after a group consolidates its motivations and assembles its sports car or its minivan or its pickup to do one thing very well, it needs to keep the vehicle in good repair so it operates to its best potential.

The examples above illustrate how these concepts may be significant for participants in folk dance revival groups in Canada. I believe that the strategies described here have policy implications for granting agencies such as the Canada Council, which seems to have been struggling in recent years about how to be more inclusive in its support of ethnic dance activity. The Council may define its mandate to support Presenters and Creators for example, but not Enjoyers. Though objective criteria for identifying the dominant strategy of each applicant may not be simple to quantify, I believe this approach has more potential than listing specific “genres” (sometimes euphemisms for cultural groups rather than dance genres) that are eligible or ineligible for funding (cf. Canada Council 2006). I believe the strategies described here are also useful for ethnochoreologists who wish to sort out and understand the widely diverse activity that takes place in this country, connecting the particular motivation(s) of each community with its style(s) of activity.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Andriy Nahachewsky

Andriy Nahachewsky is Director of the Kule Centre for Ukrainian and Canadian Folklore at the University of Alberta (www.ukrfolk.ca), Professor, and Huculak Chair of Ukrainian Culture and Ethnography. He has experience as a dancer, choreographer, critic, adjudicator and researcher of Ukrainian dance. His general research interests include ethnic dance, ethnographic methodology, Ukrainian tradition in the twentieth century, material culture, and the Ukrainian Canadian experience. He has recently completed a project “Local Culture and Diversity on the Prairies,” producing an archive of interviews with people who remember Canadian vernacular culture prior to 1939, and is finishing a monograph exploring concepts in national/ethnic/folk/character dance.

Andriy Nahachewsky

Andriy Nahachewsky est directeur du Kule Centre for Ukrainian and Canadian Folklore à l’Université d’Alberta (www.ukrfolk.ca) ; il est également professeur et détient la chaire Huculak sur la culture ukrainienne et l’ethnographie. Andriy Nahachewsky est danseur, chorégraphe, critique, juge et chercheur expérimenté dans le champ de la danse ukrainienne. Ses intérêts de recherche se portent sur la danse ethnique, la méthodologie de l’ethnographie, la tradition ukrainienne au XXe siècle, la culture matérielle et l’expérience ukraino-canadienne. Il a récemment terminé le projet « Local Culture and Diversity on the Prairies » rassemblant des entretiens avec des gens se remémorant la culture canadienne vernaculaire d’avant 1939. Il termine actuellement une monographie où il explore les concepts de danse nationale, ethnique, folklorique ainsi que de caractère.

Notes

-

[1]

I define folk dance specifically as dance based on peasant tradition. Folk dance includes the dance traditions of the peasants themselves as well as revivals. I believe that the strategies below sometimes apply more broadly to many other forms of dance as well.

-

[2]

See Shaw 1988; Lau 1991; Golinowski 1999; Harrison 2000; Clark 2001; Hill 2006.

-

[3]

Shifrin uses the word “survival” in reference to what I would describe as “vival” dance. Her use of the term “revival” seems to be limited to what I would call “national revival” (see below) (Nahachewsky 2006: 165-166). Joann Kealiinohomoku defines folk dance differently than Shifrin, and argues that folk dance is actually very rich in North America (1972: 392-397).

-

[4]

See Murillo 1983: 22.

-

[5]

The object of this article is not to promote one strategy over others, but rather to encourage thinkers and leaders of folk dance to critically observe the orientation of various communities. The “mixed-up vehicle” metaphor is intended as a depiction of an uncritical default assumption that a group can be everything to everyone. This is why I suggest that there are four-and-a-half strategies to success.

References

- Canada Council. 2006. “Eligible dance genres and specializations” Appendix A: 10. In Production project grants in dance: application form and guidelines. http://www.canadacouncil.ca/NR/rdonlyres/489F0261-1656-4186-A8CD-ABCB6344AF34/0/DAG14E 206revshJan2406.pdf.

- Clark, Danica. 2001. “Creating Identity: the Experience of Irish Dancing.” MA thesis, University of Alberta.

- Crum, Richard. 1961. “The Ukrainian Dance in North America.” In Robert B. Klymasz, ed., The Ukrainian Folk Dance: a Symposium: 5-15. Toronto: Ukrainian National Youth Federation.

- Dunin, Elsie Ivancich, compiler. 1989, 1991. Dance research published or publicly presented by members of the Study Group on Ethnochoreology. Los Angeles: International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology, vols 1-2.

- ———. 1995, 2001. Dance research published or publicly presented by members of the Study Group on Ethnochoreology. Zagreb: International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology and the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, vols 3-4.

- Dunin, Elsie Ivancich and Tvrtko Zebec, eds. 2001. Proceedings: 21st Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology: 2000 Korcula. Zagreb: International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology and the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research.

- Golinowski, Jason. 1999. “Gold, Silver, Bronze: Reflections On a Ukrainian Dance Competition.” MA thesis, University of Alberta.

- Greenhill, Pauline. 1994. “Morris: An ‘English Male Dance Tradition’.” In Ethnicity in the mainstream: three studies of English Canadian culture in Ontario: 64-125. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Harrison, Klisala. 2000. “Victoria’s First Peoples Festival: embodying Kwakw_ak_a’wakw History in Presentations of Music and Dance in Public Spaces.” MA thesis, York University.

- Hill, Anne. 2006. “Tibetan Women in Costumed Dance Performance.” MA thesis, University of Alberta.

- Hoerburger, Felix. 1968. “Once Again: On the Concept of ‘Folk Dance’.” Journal of the International Folk Music Council 20: 30-31.

- Kealiinohomoku, Joann. 1972. “Folk dance.” In Richard M. Dorson, ed., Folklore and Folklife: An Introduction: 381-401. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Lau, William. 1991. “The Chinese Dance Experience in Canadian Society: An Investigation of Four Chinese Dance Groups in Toronto.” MFA thesis. York University.

- Livingston, Tamara E. 1999. “Music Revivals: Towards a General Theory.” Ethnomusicology 43(1): 66-85.

- Murillo, Steven. 1983. “Some Philosophical Considerations Regarding the Cross Cultural Stage Adaptation of Folk Dance.” Journal of the Association of Graduate Dance Ethnologists, UCLA 7: 21-24.

- Nahachewsky, Andriy. 1997. “Conceptual Categories of Ethnic Dance: the Canadian Ukrainian Case.” In Selma Odom and Mary Jane Warner, eds., Canadian dance studies 2: 137-150. Toronto: York University.

- ———. 2001a [2000]. “Once Again: On the Concept of ‘Second Existence Folk Dance’.” In Frank Hall and Irene Loutzaki eds., ICTM 20th Ethnochoreology Symposium Proceedings 1998: Traditional Dance and its Historical Sources, Creative Processes: Improvisation and Composition, Müzik kültür folklore dogru: 125-143. Istanbul: Bogazici University Press.

- ———. 2001b. “Strategies for Theatricalizing Folk Dance.” In Elsie Ivancich Dunin and Tvrtko Zebec, eds., Proceedings: 21st Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology: 228-234. Zagreb: International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology and the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research.

- ———. 2001c. Pobutovi tantsi kanads’kykh ukraintsiv [Social dances of Canadian Ukrainians]. Kyiv: Rodovid.

- ———. 2006. “Shifting Orientations in Dance Revivals: from ‘National’ to ‘Spectacular’ in Ukrainian Canadian Dance.” Narodna umjetnost. Croatian journal of ethnology and folklore research, 43(1): 161-178.

- Pagels, Jurgen. 1984. Character Dance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Quigley, Colin. 1985. Close to the Floor: Folk Dance in Newfoundland. St. John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Séguin, Robert Lionel. 1986. La danse traditionnelle au Québec. Sillery: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Shaw, Sylvia. 1988. “Attitudes of Canadians of Ukrainian Descent Toward Ukrainian Dance.” PhD dissertation, University of Alberta.

- Shifrin, Ellen. 2006. “Folk dance” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE& Params=A1SEC820581.

- Zebec, Tvrtko, compiler. 2003. Dance Research Published or Publicly Presented by Members of the Study Group on Ethnochoreology. Zagreb: International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology and the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7