Résumés

Abstract

Extispicy in the Everyday is a project-in-progress which explores the continued fascination with innards in the human imagination, particularly reinterpreting extispicy, the ancient practice of divination using the entrails.

Résumé

Extispicy in the Everyday (L’‘extispicité’ dans la vie de tous les jours, traduction de l’équipe éditoriale) est le nom d’un projet en constante évolution qui examine la fascination éternelle de l’imagination humaine envers les activités qui se déroulent à l’intérieur de notre corps, et qui plus particulièrement réexamine l’‘extispicité’, cette pratique ancienne de divination par l’examen des entrailles [d’une victime immolée].

Corps de l’article

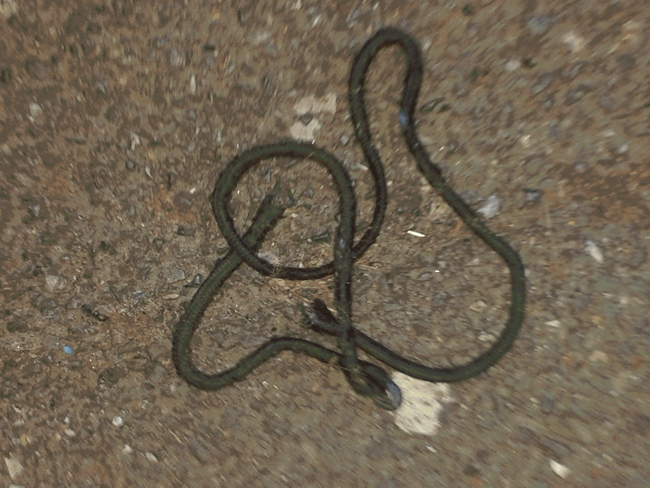

Extispicy in the Everyday is a project-in-progress which explores the fascination with innards in the human imagination through live performance, image collection, artist book, sculpture, food, and writing. In this paper, I will share my re-interpretation of the ancient practice of extispicy, divination using the entrails, through the practice of noticing and photographing forms in daily life that depict materials which resemble the guts.

Extispicy, divination using the entrails, was “the most profusely attested and the most enduring” of ancient divination practices.[1] As well as the liver, which was believed to be a tablet written by the gods at the point of sacrifice, the colon, or ‘palace of the intestines’ was also observed.

At the heart of ancient divination are notions of interconnectivity. The innards metaphorically and physically connect the external environment, actions, events, and sidereal bodies, with the inside of the body, the viscera of animals. Convoluted forms found on clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia are thought to be the results of sacrifice and divination. “When laid out for inspection,” intestines “form a distinctive labyrinthine spiral,” which for the Romans and Etruscans, “was associated with the orbital motions of planets.”[2] Representing the colons of sheep, “it is to be suspected that at least part of the inspiration for the spiraling maze patterns in a variety of different cultures in antiquity must have come from the observation of the intestines of sacrificial animals.”[3] This connection is illustrated by the character, Oshima in Haruki Murakami’s novel, Kafka on the Shore when he enlightens Kafka on the origins of labyrinths:

“It was the ancient Mesopotamians. They pulled out animal intestines…and used the shape to predict the future…So the prototype for labyrinths is, in a word, guts. Which means that the principle for the labyrinth is inside you. And that correlates to the labyrinth outside…. Things that are outside you are a projection of what’s inside you, and what’s inside you is a projection of what’s outside.”[4]

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Through urban environments, rural landscapes, and my everyday encounters, I have been gathering images depicting actual guts, and/or materials which resemble the intestines. Such a way of engaging with the world “awakens attitudes and skills” as historian, John R. Stilgoe writes, ‘made dormant by programmed education, jobs, and the hectic dash from dry cleaners, to grocery store to dentist.’[5] By honing my capacities to notice entrails in the world in a dropped ribbon, discarded cabling, a dead snake, or garden hose, eighteen images of which are illustrated in the images below, I am enacting what Jane Bennet calls “thing-power,”[6] enabling “the curious ability of inanimate things to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle.”[7]

The practice of noticing reminds us of Anna Tsing’s “Arts of Inclusion” relative to fungi, in which she posits that “noticing inspires artists as well as naturalists.”[8] She evokes the practice of composer John Cage, an avid mushroom hunter, who “thought noticing mushrooms and noticing sounds in music were related skills,”[9] which he hoped would inspire audiences to attend to the potential of sound, created or serendipitous.

In noticing and collecting nonhuman animal and non-living materials in the form of guts, I am reinterpreting the practice of extispicy, divination using the entrails, as an invocation, “cultivating, patient, sensory attentiveness to nonhuman forces operating outside and inside the human body.”[10] ‘To divine’ also means ‘to conjure,’[11] which thus signifies ideas of ‘bring[ing] into existence,’[12] and so I ‘call to mind’[13] my insides, conceptually and visually reconnecting the idea of the gastrointestinal tract, though seemingly inside the body, being part of the outside world, problematizing the false dichotomies and boundaries of inside and outside. Feminist philosopher, Shannon Sullivan, reminds us that it is the gut wall that is the “site of a dynamic co-constitution in which what is ‘properly’ body and what is ‘properly’ world are necessarily and productively indeterminate.”[14]

In relation to food studies in particular, we might consider these concerns as ways of attending to what it is to be an eating, digesting body processes — permeable, entangled, and interdependent within and of the world. With this in mind, we might recollect the work of hydrofeminist, and recent President of the Association for Literature, Environment and Culture in Canada, Astrida Neimanis’s proposal “to reject a human separation from Nature ‘out there,’”[15] “If we do live as bodies ‘in common,’” she proposes, “this commonality needs to extend beyond the human, into a more expansive sense of ‘we.’”[16] I would argue that this also includes non-living materials, for example, food and waste, “bodies inorganic as well as organic,”[17] which as Bennett imagines “can inspire a greater sense of the extent to which all bodies are kin in the sense of inextricably enmeshed in a dense network of relations.”[18]

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Amanda Couch is an artist, researcher, and senior lecturer at University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, where she teaches Fine Art and Creative Arts Education. Cutting across media, Amanda’s art practice and research researches and reimagines histories of the body, particularly the digestive system, skin and hair, and ancient artefacts and rituals, through the domains of performance, sculpture, photography, print and the book, food, participation, and writing.

Notes

-

[1]

Ivan Starr, “In Search of Principles of Prognostication in Extispicy,” Hebrew Union College Annual 45 (1974): 17-23, 17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23506846.

-

[2]

Robert Temple, “Superstition and Science: Ancient ways of Predicting the Future,” Odyssey, 1, 3 (1995): 60-64, 62.

-

[3]

Robert Temple, “An Anatomical Verification of The Reading of a Term in Extispicy,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 34, Nos. 1-2 (1982): 19-27, 21.

-

[4]

Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore (London: Vintage, 2005), 379.

-

[5]

John R. Stilgoe, Outside Lies Magic: Regaining History and Awareness in Everyday Places (New York: Walker and Company, 1998), 11.

-

[6]

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 7.

-

[7]

Ibid, 6.

-

[8]

Anna Tsing, “Arts of Inclusion, or, How to Love a Mushroom,” Australian Humanities Review, 50 (2011): 5–22, 10, accessed April, 19 2018, http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p111121/pdf/ch019.pdf

-

[9]

Ibid.

-

[10]

Bennett, Vibrant Matter, xiv.

-

[11]

Online Etymology Dictionary, 2018, “divine,” accessed April 19, 2018, https://www.etymonline.com/word/divine

-

[12]

Dictionary.com, 2018, “conjure,” accessed April 19, 2018, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/conjure--up

-

[13]

Ibid.

-

[14]

Shannon Sullivan, The Physiology of Sexist and Racist Oppression (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 69.

-

[15]

Astrida Neimanis, “Introduction: Figuring Bodies of Water,” in Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, 2012, 7, accessed December 14, 2017, https://www.academia.edu/28107193/Bodies_of_Water_Posthuman_Feminist_Phenomenology_link_to_Open_Access_HTML_

-

[16]

Ibid., 16.

-

[17]

Bennett, Vibrant Matter, 7.

-

[18]

Ibid., 13.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Amanda Couch est artiste, chercheuse, et chargée de cours à la University for the Creative Arts, à Farnham, où elle enseigne les beaux-arts et les arts créatifs. Recoupant bon nombre de médiums, les oeuvres d’art d’Amanda ainsi que ses recherches examinent et réinventent les aventures que vit notre corps, plus particulièrement le système digestif, la peau et les cheveux, ainsi que des objets anciens et des rituels, par le truchement de différentes activités, tels des spectacles, de la sculpture, de la photographie, des gravures et des livres, la préparation de nourriture, la participation à des événements, et l’écriture.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19