Résumés

Abstract

The slogan of Montreal's Marché Jean-Talon is "When country comes to town." An afternoon stroll through the city's largest public food market suggests that the word applies in both senses: country, as in the rural landscape, and country, as in the nations of the world. In surveying the cornucopia of place-based messages that greet potential shoppers, this paper positions the farmers’ market as a site for the consumption of authentic and authenticated foods, and thus a suitable microcosm for the exploration of larger issues related to consumer trends towards provenance purchasing, origin labelling, and the promotion of place as the primary marker of alimentary authenticity in the wider food marketplace.

Résumé

Le Marché Jean-Talon de Montréal est historiquement le point de rencontre entre la ville et la campagne, ou devrait-on dire, la ville et les campagnes. En effet, une visite du plus grand marché publique de Montréal nous offre à la fois un goût de la campagne environnante, mais aussi de toutes les nations du monde. Cette étude fait état de l’abondance des messages à orientation géographique s’offrant aux clients, et situe le marché public comme un site pour la consommation d’aliments authentiques et authentificateurs. Le marché apparaît ainsi comme un microcosme se prêtant à l’exploration de questions plus vastes autour des tendances des consommateurs vis-à-vis de la consommation de produits d’appellation d’origine, de l’étiquetage des produits, et la promotion de l’espace géographique comme premier signe d’authenticité alimentaire au sein du vaste marché alimentaire.

Corps de l’article

Figure 1[1]

Figure 2

Figure 3

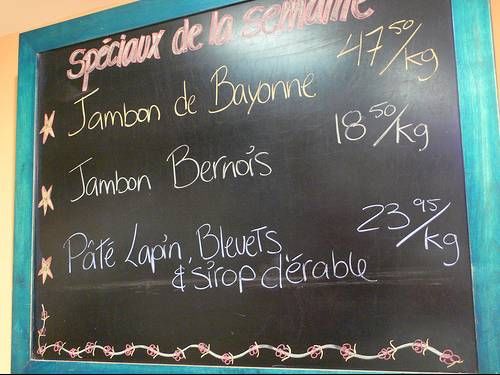

The slogan of Montreal’s Marché Jean-Talon is “When country comes to town.” An afternoon stroll through the city’s largest public food market suggests that the word “country” applies in two senses: country, as in the rural landscape, and country, as in one of the nations of the world. It thus constitutes a suitable microcosm for the exploration of larger issues related to consumer trends towards provenance purchasing and the promotion of place as the primary marker of alimentary authenticity in the wider food marketplace. Using snapshots taken on location of edible goods for sale—those that can be traced to the fields surrounding the city of Montreal as well as those linked to faraway locales—this tour probes the ways in which origin-indicated products communicate to modern citizen-consumers a link to a real or imagined sense of place. In doing so, it positions the market as a site for the consumption of “authentic” foods, with an eye to the practices and processes that support their authentication.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Our tour makes its way past farmers’ stands, ethnic food marts, and chichi shops, surveying the cornucopia of place-based messages that greet potential shoppers. We are looking for various geographic signifiers on labels, signage, and packaging in order to analyze the ways in which origin-identified goods communicate to modern citizen-consumers a link to a real or imagined sense of place. What products do farmers and shopkeepers choose to represent? How do labels and signs found at the site communicate notions of place and taste? In what ways are notions of authenticity conveyed through packaging and posters? What types of design, fonts, imagery, marks, or lack thereof, do they appear to use to legitimate themselves? What do the products, intentionally or not, tell us?

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Hand-lettered words hastily scrawled in black marker on a sheet of cardboard announcing blueberries from Lac St-Jean for two dollars. A plump bottle of Dijon mustard covered in awards and stamps. At first glance, these goods may appear to come from opposite ends of the spectrum, yet a closer reading suggests they may have more in common than initially meets the eye. Food is of course a basic requirement for life, but origin-indicated food products are socially constructed commodities. The market acts at once as a site for localist purchasing, a platform for the support of regional producers, but also as what I would term “locationist” purchasing, a showcase for the consumption of international products on which geographic origin is communicated. Origin thus clearly stands as a motivation in marketing and purchasing decisions. Shoppers have demonstrated a willingness to pay more for foodstuffs legitimated by locationist labeling, and renewed interest exists in the localist experience offered by farmers’ markets as opposed to large-surface grocery stores.[2] I suggest that postmodern citizen-consumers seek authentic shopping experiences and thereby indirectly assign a renewed emphasis on place as the marker of that authenticity. By means of clarifying the loaded term “authentic,” I would update Walter Benjamin’s statement that “[t]he presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity”[3] to “the presence of the place is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity.” That said, simply because foods appear at the market does not mean they are authentic, and the market itself is a contested cultural construction, a site where different conceptions of identity—culinary and cultural and class-based—meet and eat.

In interpreting the language at the site, I refer to Roland Barthes’s theory of the sign as the total of signifier (the material object, specifically food labels) and the signified (its meaning, here, authentic foods). Like advertising, packaging operates on denotative and connotative levels, as part of a mythological system that elevates objects of nutrition to objects that promise a link to certain places and tastes. “The technique of advertising is to correlate feelings, moods or attributes to tangible objects, linking possible unattainable things with those that are attainable, and thus reassuring us that the former are within reach.”[4] In “Rhetoric of the Image,” Barthes’s analysis of an advertisement for Panzani pasta showing a half open mesh bag with tri-colour packages and tins, as well as fresh produce, demonstrates a “return from the market” message. This is not so much Italy itself, but what he names Italianicity, the way a nation and a people and their culinary culture have been reimagined, reinvented, and readied for retail.[5]

Borrowing from Barthes, I have identified five key, and admittedly overlapping, -icities at the market: Montrealicity, Terroiricity, Artisanicity, Regionalicity, and Geographicity.

Montrealicity.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

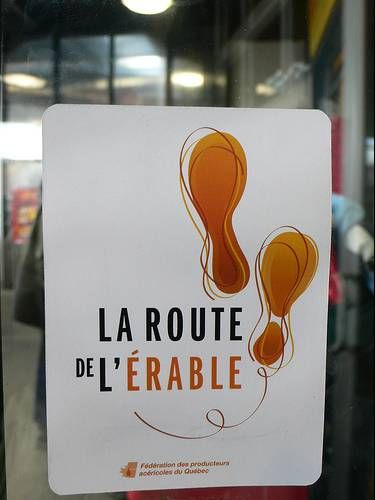

We’ll begin with the place itself as an intersection of the local and the global, rural and urban, multicultural and national. It reflects the multifaceted character of this New World city. We find in store signage and promotional material, both international representation, Italian, French, Middle Eastern, North African, and regional, La Route De l’Erable, the Marché des Saveurs du Québec, “fromages de Quebec et d’ailleurs.” While these signs speak of vastly different locales, these different actors under its roof bring together differing visions of the city’s culinary identity to create a sense of abundance within a harmonious heterotopia.

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Chez Nino, a produce stand on the south side of the market, blends an Italian name “Nino” with the French “Chez,” in true Montreal-style parlance. It is also a remnant of the days when the market was a soccer field, and Italian residents of the area sold their harvest over garden fences to fans attending the games—a ritual around which a permanent market was eventually expanded and established. Signs announcing tire à glace, a seasonal treat of maple syrup on snow, are hastily written, the price only a dollar, emphasizing the ephemerality and the urgency of the market experience.

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

In fact, the growth of the modern farmers’ market movement remains a relatively recent phenomenon. The 20th century was marked by an increasing separation of food consumption from food production, thanks to “the efforts of the food industry to obscure and mystify the link between the farm and the dinner table.”[6] Against a landscape of economic globalization, standardization, and homogenization, the market offers opportunities for face-to-face encounters with food producers, a convivial setting, and at least the appearance of fresher, cheaper, and perhaps more ethical food choices than the typical supermarket allows.

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

A controversial renovation project that took place in 2004 brought to light concerns that the essential character of the market would be lost, the jumble of boxes, the edge-of-chaos, the juxtapositions, that give Marché Jean-Talon its Montrealicity. The fear that it would be smoothed into a more polished locale was reflected in petitions, media coverage, and even a docu-drama series: clearly Montrealers wanted to maintain unity in the market’s disunity. In response, market administrators created new signage but kept the look simple, irreproachable, and anything but slick; its bold letters and daisies seem so guileless that they supersede class and cultural differences.

Artisanicity.

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

The word artisanal pops up frequently at the market, along with images that convey a human hand behind the product, establishing a link with a person and with tradition.

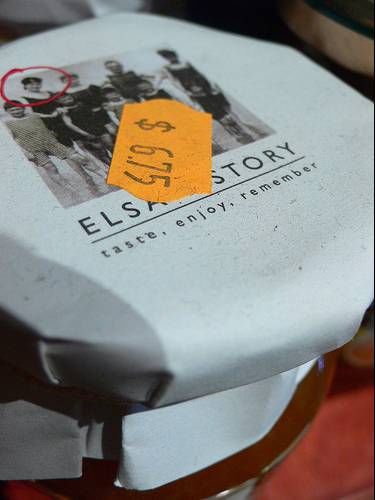

Figure 25

Figure 26

Figure 27

This could be Aunt May’s hot pepper sauce, a “quality product of Barbados,” or Elsa’s Story jams that exhort the shopper to “taste, enjoy, remember.” This package goes so far as to circle a face on the lid, a woman in a black and white photograph from an era past, presumably Elsa herself, with us in spirit and in jam. Remember what, one might ask? An aunt’s preserves? A time when food production was different?

Figure 28

Figure 29

Figure 30

Under the signifier artisanal, I also include what I call folk lettering, as it appears on signs for locally grown produce and small-scale confections often retailed by the farmer or producer themselves. As described by artist Ben Shahn, these efforts by amateurs amount to a sort of folk alphabet:

One can see the violation of every rule, every principle, every law of form or taste that may have required centuries for its formulation. This material is exiled from the domain of true lettering; it is anathema to letterers. It thins letters where they should be thick; it thickens them where they should be thin. It adds serifs where they don’t belong; it leaves them out where they do belong. Its spaces jump and its letters shim. It is cacophonous and utterly unacceptable. Being so, it is irresistibly interesting. I had first used it long ago, somewhat humorously, for color and a sense of place.[7]

Figure 31

Figure 32

Figure 33

At one produce stand, we come across drawings for vegetables in a style Shahn might appreciate. At another stand, a sign for frozen cranberries from Quebec with unnecessary quotation marks around “sold here.” A third sign in bubbly letters offers English cucumbers, “always fresh.” These hand-written, personal signs—and their digitally rendered facsimiles—the human characters on labels, their nostalgic imagery, and the enthusiasm and rural innocence they convey, at once denies their commodification while also connecting us to the “constructed folklore of simple people living authentic premodern experiences outside the complications of market capitalism, mass culture, modernism, and so on.”[8]

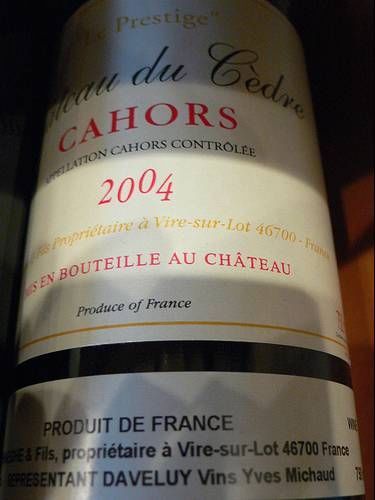

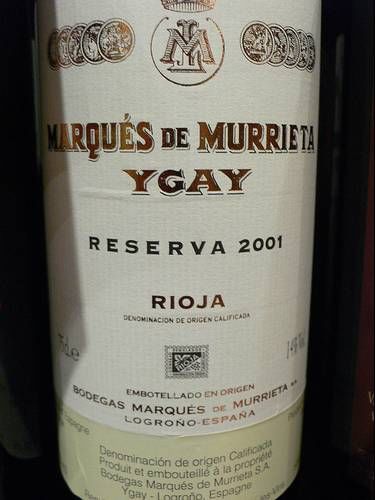

Terroiricity.

Figure 34

Figure 35

Figure 36

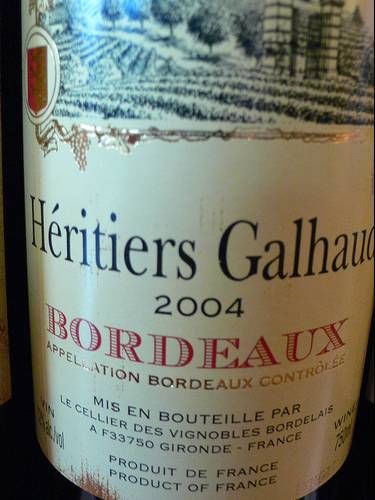

The word terroir appears often at the market, linguistic shorthand that covers a mutually upheld local and global mythology of authenticity. Terroir represents a key if controversial concept underlying how foods come to be authenticated and gain added value in the food market place. Rooted in the French word terre, for land, and loosely explained as the idea that a particular interplay of geography, history, and human factors—some go as far as to call this last factor “soul”[9]—imbues foods with a particular taste that cannot be recreated elsewhere. In popular publications and in food studies literature on both sides of the Atlantic, the symbolic capital, or what I would call natural capital, of certain place-based foods is often referred to this way. In the past, the notion of terroir has been closely associated with European wines.

Figure 37

Figure 38

Figure 39

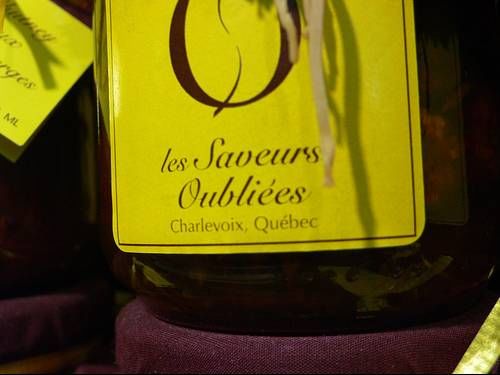

Now producers and consumers use the term to describe artisanal foods from specific places—butter from Normandy, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese from Parma and surrounding regions of Italy, or Criollo chocolate from Venezuela, for example.

Figure 40

Figure 41

Figure 42

Terroir fosters a mythological link between the arena of production to the arena of consumption (though that link may in fact be concrete). It is a place-based signifier that reinforces a popular geographic imagination that perceives difference and distinction within a culture of commodities. The Marché des Saveurs and the Hamel cheese shop, for example, invite us to sample different pieces of place. For growing urban populations, this stands for not only a specific place, but a wider sense of place, “a structure of feeling” based on the idea of a happier past and the “rural innocence” of the pastoral, as Raymond Williams holds in The Country and the City.[10] In many ways, the popularization of the term terroir and its implied values represents a victory of country over city, past over future, classified over common.

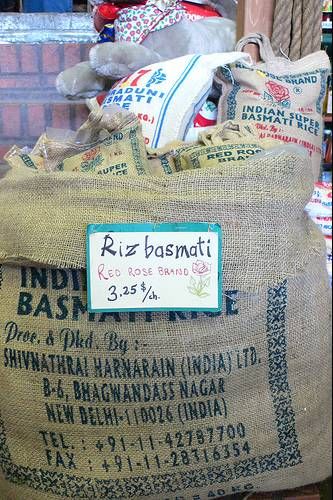

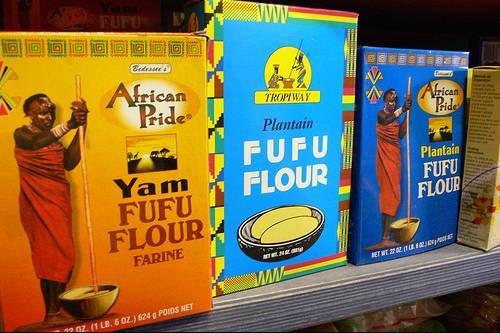

Regionalicity.

Figure 43

Figure 44

Figure 45

Figure 46

On the linguistic level, the commodities at the market communicate numerous national associations, yet more specifically and increasingly more commonly, they promote regional associations. We need only peruse the varieties of rice available. At Marché Jean-Talon we find Callaparra, “The Best Rice for Paella,” at $12 a kilo. Certified Denominacion de Origen, it hails from the Valencian village of Calasparra. Similarly, Matiz Valenciano refers to the region of Spain where this historic variety is grown. Next to it, Basmati rice from India in a burlap bag encapsulates the tradition for sale. Tilda packaging notes that “pure Basmati tastes like no other rice on earth,” and shows us a watery, exotic scene where, we assume, the rice was cultivated. Asian Premium Sweet Rice, despite the Asian characters on the packaging, tells us the grain is grown in California. As this last example suggests, national associations may be disconnected from the origins of the commodity itself, or the culinary values of its country of origin. Referring back to Barthes’s Panzani pasta, spaghetti with tomato sauce, regarded as a typical Italian dish, epitomizes this: pasta originated in China, tomatoes came from South America.

Figure 47

Figure 48

Figure 49

A tightly controlled system of origin labeling regulated on an international scale by the World Trade Organization plays a direct role in the relevance of regionalicity. We may view this as a formal counterpart to terroir as conceptualization of taste—call it institutional lettering as opposed to folk lettering. The shelves at the market are full of these certifications: Appelation d’Origine Controlée (AOC), Italy’s Denominazione di Origin Controllata (DOC), the aforementioned Denominacion de Origen (DO). These regulatory initiatives find their roots in the French AOC, a hierarchical classification system dating to the late 19th century through which wines from specific terrains, or terroirs, are provided with the publicly recognized stamp of approval at the end of the bureaucratic process.[11] Food historian Kathleen Guy notes a marked revolution in consumption that led the French to self-consciously seek ways to express unity, fraternity, and identity, and to develop a “complex relationship with food and drink.” She writes,

By the turn of the century, innate, national taste and “authentic” quality wines were so intertwined, so “rooted” in France, that it was difficult to invoke one without eliciting the other. Although French luxury wines could serve as symbols of social stratification, the wines of France, more generally, and the unique terroir that produced them were encrusted with myths of national genius.[12]

Barthes, too, weighs in on wine as a totem-drink. “Wine is felt by the French nation to be a possession which is its very own, just like its three hundred and sixty types of cheese and its culture. It is a totem-drink, corresponding to the milk of the Dutch cow or the tea ceremonially taken by the British Royal Family.”[13]

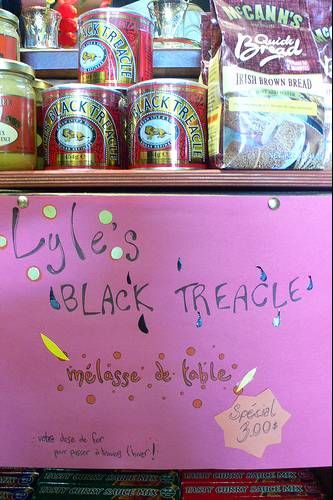

Figure 50

Figure 51

Figure 52

Originally applied to alcohols, Champagne being the most high-profile example, these marks are currently extended to many other edible goods—sherry vinegar, cheese, and tea, for example, through a form of place-making and totemizing that guarantees a certain level of quality and of distinction to the consumer. Similar messages are displayed by labels bearing prizes, where the maintenance of traditional imagery and certification is also certified by a variety of authorities. A package of Duchy Originals Highland biscuits, for instance, lets us know twice, with the royal emblem on the package and stamped on each cookie, that its contents have been approved by Prince Charles himself.

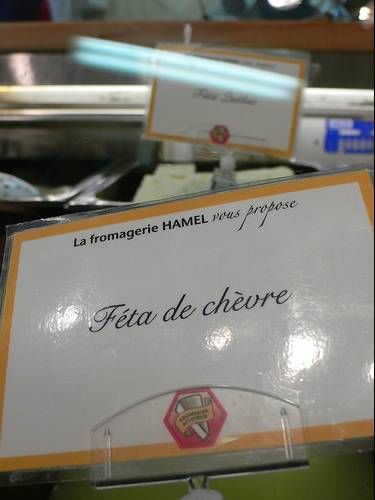

Geographicity.

Figure 53

Figure 54

Figure 55

And finally, a sign that in all likelihood will no longer appear at the market in the future. Since October 2005, one of the meanings of the feta signs on display at the Fromagerie Hamel is that you are not in Europe if you’re seeing them. That’s when the European Court of Justice ruled that the term “feta” is geographic and not generic, a name so closely associated with place that it has been awarded intellectual property rights. Greece won protected designation of origin for its brine-soaked ewe- or goat-milk cheese in recognition of its specific ecology, history, and savoir-faire. Now only feta made in Greece can be marketed in Europe, to the dismay of French, Bulgarian, and Danish manufacturers who have been producing the cheese for some time. The legal battles surrounding the repatriation of feta, arguably the highest-profile food thus far to be granted such extensive market protection, have significant economic, political, and cultural implications. But above all this case underlines the perceived significance of place in the trademarking of taste. Therefore Feta from different countries now appears at Hamel, but soon this may change as Canada and other North American countries claim stakes in this system of place-based trademarks. It is tit for tat: we recognize feta, they recognize Charlevoix lamb.

Figure 56

Figure 57

Figure 58

Such Geographical Indications are the source of much conflict within the WTO, one that has pitted Old World against New. European Communities have advanced a proposition for a global database of products to be associated with a region. Canada, the U.S., and other countries outside of Europe have not yet created state-sponsored certifications for their own traditional, national, or regional foods. The only exception on this continent so far is Quebec’s Charlevoix lamb, which earned its own appellation from the Canadian government last year.

Figure 59

Figure 60

Figure 61

Our visit to the market hints at the more complex stories behind its food items, giving us a nuanced perspective on Marché Jean-Talon while illuminating some of the larger, outside issues at play. On the international stage, rigorous processes administered by world-governing bodies are certifying place-based products. At regional levels, the resurgence of interest in farmers’ markets, demand for niche labels, and the face-to-face encounters of the personalized shopping experience with the producers demonstrate marked tendencies towards provenance purchasing on the part of citizen-consumers. One possible reason that a taste of place has gained financial and symbolic value in the era of global governance is that as borders between countries come down and globalization threatens national and regional identities, the preservation of culinary legacy and the sense of locality encapsulated by labels of origin meet a profound need for reassurance of cultural continuity on the part of citizen-consumers. Certainly, there has been considerable scholarship on food as an expression of culture, though whether that culture is being lost to posterity or transformed into new forms through hybridity remains the source of academic debate. According to anthropologist Richard Wilk:

Both sides in the debate start from the same assumption: that national, regional, or ethnic cultures are fundamentally different from mobile, market-based, mass-mediated, global cultural forms, so they represent different and basically antithetical processes. The two may not annihilate each other right away, but there is no question that they are opposed, one pushing for a world of local distinctions, and the other aiming to wipe those distinctions away and homogenize everything.[14]

Recent preoccupations with provenance and certification may also be reinforced by millennial health and safety scares, selling food by assuring a level of quality not provided by largely untraceable, mass-manufactured edible items. “The marketing of food as local or national appeals to assumptions about the qualities of place-based foodways and, more fundamentally, to people’s affinities for and identification with place itself,” as geographer Susanne Freidberg notes.[15] From hand-lettered posters to internationally mandated certification marks, what do the signs at the Marché Jean-Talon all add up to? Through ties to an authentic place, real or imagined, goods are promoted and perceived as having added value for today’s consumers. Whatever contested visions of culinary cultures the products offer, as a whole they reinforce a greater sense of place that is the myth of the market itself, its natural sort of being-there within an even larger mythology of alimentary authenticity. Authenticated foods, like farmers’ markets, are nothing new—in fact, it could be argued, they are quite the opposite, associated with tradition, history, and sense of place—but they are now commodified and communicated in new ways. Marché Jean-Talon appears on the surface to bridge the gap by at once validating local distinctions while transforming them into market-based, mass-mediated commodities.

Parties annexes

Biographical notice

Montreal-based journalist Sarah Musgrave writes about food and travel for numerous magazines and newspapers, including as Casual Dining Critic of the Montreal Gazette, as well as pursuing academic research on the link between place and taste in the marketing of authentic foods.

Notes

-

[1]

Copyright © Sarah Musgrave is the copyright holder of all images within this article.

-

[2]

Dimitris Skuras and Aleka Vakrou, “Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Origin Labelled Wine: A Greek Case Study,” British Food Journal 104, no. 11 (2002): 898-912; Frank Thiediga and Bertil Sylvander, “Welcome to the Club? An Economical Approach to Geographical Indications in the European Union,” Agrarwirtschaft (2000): 444-451, www.originfood.org/pdf/partners/ bs7nov00.pdf; Elizabeth Barham, “Translating Terroir: The Global Challenge of French AOC Labeling,” Journal of Rural Studies 19 (2003): 127–138.

-

[3]

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, 1969), 120.

-

[4]

Roland Barthes, Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), 31.

-

[5]

Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image,” in Image, Music, Text, ed. and trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 33-37.

-

[6]

Warren Belasco, “Food Matters: Perspectives on an Emerging Field,” in Food Nations: Selling Taste in Consumer Societies, eds. Warren Belasco and Philip Scranton (New York: Routledge, 2002), 12.

-

[7]

John D. Morse, ed., “Love and Joy About Letters,” in Ben Shahn (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972): 143.

-

[8]

Steve Penfold, “Eddie Shack was no Tim Horton: Donuts and the Folklore of Mass Culture in Canada,” in Food Nations, 59.

-

[9]

Kathleen M. Guy, “Rituals of Pleasure in the Land of Treasures: Wine Consumption and the Making of French Identity in the Late Nineteenth Century,” in Food Nations, 36.

-

[10]

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (New York: Oxford University Press US, 1975).

-

[11]

Barham.

-

[12]

Guy, 41.

-

[13]

Barthes, Mythologies, 58.

-

[14]

Richard Wilk, “Food and Nationalism: The Origins of ‘Belizean Food,’” in Food Nations, 69.

-

[15]

Susanne Friedberg, French Beans and Food Scares: Culture and Commerce in an Anxious Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 218.

Liste des figures

Figure 1[1]

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 26

Figure 27

Figure 28

Figure 29

Figure 30

Figure 31

Figure 32

Figure 33

Figure 34

Figure 35

Figure 36

Figure 37

Figure 38

Figure 39

Figure 40

Figure 41

Figure 42

Figure 43

Figure 44

Figure 45

Figure 46

Figure 47

Figure 48

Figure 49

Figure 50

Figure 51

Figure 52

Figure 53

Figure 54

Figure 55

Figure 56

Figure 57

Figure 58

Figure 59

Figure 60

Figure 61