Résumés

Abstract

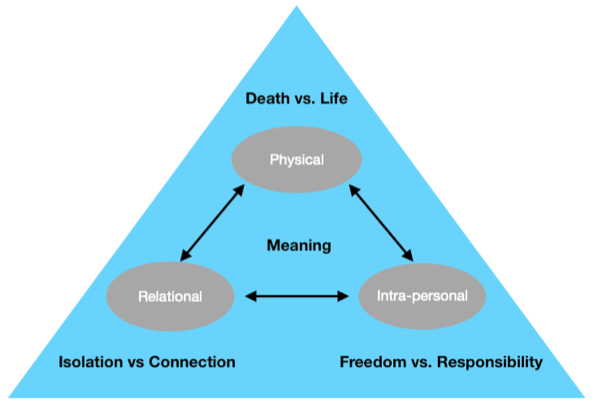

In this paper, an integrated existential framework for trauma theory is presented. The framework is based on the clustering of current trauma theories into physical, relational, and intrapersonal categories, and the relation of these three clusters to Irvine Yalom’s ultimate existential concerns of life/death, connection/isolation, and freedom/responsibility. Recent research has revealed an interplay between the physiological and psychosocial aspects of traumatic experiences, suggesting that a theoretical integration which includes consideration of physiological change, fear conditioning, and relational impacts is required to fully address the impacts of trauma. The fourth existential concern, meaning/meaninglessness, is argued to underlie all of the aspects of trauma, forming a common connection between all theories. This paper undertakes a brief review of current theories in traumatology to illustrate the validity of the three theoretical clusters, explores the current application of existential theory to the conceptualization of trauma, and presents a unifying organizational framework for trauma theory based in existentialism. Critiques of theory integration and existentialism are explored, followed by an analysis of risks for existential theory in the application of this framework. Implications for future research and social work practice based on the existential framework are also presented.

Keywords:

- trauma,

- existential,

- PTSD,

- theoretical,

- integration,

- framework

Résumé

Dans cet article, un cadre existentiel intégré pour la théorie du traumatisme est présenté. Ce cadre est basé sur le regroupement des théories du traumatisme actuelles en catégories physique, relationnelle et intrapersonnelle, et sur la relation de ces trois catégories avec les préoccupations existentielles ultimes d’Irvine Yalom, de vie/mort, de connexion/isolement, et de liberté/responsabilité. Des recherches récentes ont révélé une interaction entre les aspects physiologiques et psychosociaux de l’expérience traumatique, suggérant qu’une intégration théorique incluant la prise en compte du changement physiologique, du conditionnement de la peur, et des impacts relationnels est nécessaire pour traiter pleinement les impacts du traumatisme. La quatrième préoccupation existentielle, la signification/absence de signification, sous-tend tous les aspects du traumatisme, formant un lien commun entre toutes les théories. Ce document passe brièvement en revue les théories actuelles en traumatologie pour illustrer la validité des trois regroupements théoriques, explore l’application actuelle de la théorie existentielle à la conceptualisation du traumatisme et présente un cadre organisationnel unificateur pour la théorie du traumatisme basée sur l’existentialisme. Les critiques de l’intégration des théories et de l’existentialisme sont explorées, suivies d’une analyse des risques pour la théorie existentielle dans l’application de ce cadre. Les implications pour des recherches futures et la pratique du travail social basé sur le cadre existentiel sont également présentées.

Mots-clés :

- trauma,

- existential,

- TSPT,

- intégration,

- cadre théorique

Corps de l’article

Explanatory theories of posttraumatic symptomology are numerous. Social workers may become overwhelmed by the array of cognitive, emotional, physiological, personality, and relational theories of trauma, and combinations thereof, represented in the literature. It seems unlikely that such a complex and varied phenomenon as trauma will be fully explained by a single theory. It is perhaps more practical to utilize a theoretical framework that will allow social workers to organize and make sense of the many aspects of trauma and the variety of trauma theories.

An organizational framework for trauma theory must capture both the depth of the traumatic experience as well as the breadth of the theory base. While many theories focus on specific aspects of the traumatic experience, such as physiological response or cognitive processes, there is something about the traumatic experience that defies technical definition. In the words of Briere and Scott (2015), “[t]rauma can alter the very meaning we give to our lives and can produce feelings and experiences that are not easily categorized in diagnostic manuals” (p. 31). The deep impacts of trauma invite a theoretical framework that captures the complexity of the human experience, including its less tangible aspects such as meaning, spirituality, mortality, and identity. Existential theory, with its philosophical roots and contemplation of the human condition, may provide a basis for such a framework.

Existential theory has some presence within recent trauma literature (Day, 2009; Du Toit, 2017; Floyd et al., 2005; Hoffman et al., 2013; Thompson & Walsh, 2010; Vachon et al., 2016; Weems et al., 2016). These contributions focus on the use of existential theory as a stand-alone approach. This paper will argue that the flexibility of existential theory and the congruency of its theoretical constructs with existing trauma theories make it a logical framework within which to organize a variety of theoretical perspectives of trauma. This framework would allow social workers to capture the existential depth of the traumatic experience as well as the breadth of specific theories that have proved clinically useful in trauma treatment.

Current theoretical perspectives of trauma

A review of current trauma literature reveals that explanatory models of trauma may be categorized into three groups: the physical, the relational, and the intrapersonal models. A number of the more commonly known theories under each model are introduced briefly below, to provide a broad overview of our current understanding of trauma.

Physical theories of trauma

Physical theories of trauma generally derive from the biomedical paradigm, and relate to neurophysiology, endocrinology, genetics, and immune function. For example, meta-analysis of childhood trauma exposure and neuropsychological functioning suggests that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may result from an inability of the right prefrontal cortex to regulate the right amygdala (Malarbi et al., 2017). There are also linkages between posttraumatic symptoms and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) regulation. In people with a PTSD diagnosis, elevated levels of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter implicated in SNS regulation, are correlated with arousal symptoms such as nightmares and startle reflexes (Lipov & Kelzenberg, 2012). The presence of certain gene variants, in combination with trauma exposure, has been linked with higher rates of PTSD. Specifically, certain genes expressed within the hippocampus and amygdala may cause sensitivity to environmental factors (Wang et al., 2018). Epigenetics may also contribute to fear conditioning. It is possible that epigenetic changes in gene expression and cellular function may disrupt the normal formation, storage, and extinction of fear memories, leading to persistent re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal (Kwapis & Wood, 2014). Abnormalities in the structure, function, and connectivity of various brain regions, such as the amygdala and hippocampus, amongst others, have also been found in people with posttraumatic symptoms (Admon et al., 2013). Gupta (2013) notes that PTSD is associated with alterations to the limbic system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and sympatho-adrenal medullary axis, leading to endocrine, immune, and central nervous system dysfunction. He links these physiological disruptions to sleep disorder, hypervigilance, and various somatic symptoms.

The implication of a physiological explanation of PTSD is the focus on physiology in treatment, such as addressing neurochemistry and nervous system regulation to reduce trauma symptoms. This approach to treatment may include the use of psychotropic medications (Kwapis & Wood, 2014; Lipov & Kelzenberg, 2012; MacNamara et al., 2016); focus on neuroplasticity, neurofeedback, and/or sensory stimulation (Herold et al., 2016; Leddick, 2018); exploration of alternative bodywork approaches, such as yoga therapy (Dick et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2014; Nolan, 2016); or recommendation of general physical exercise (Rosenbaum et al., 2015). It is possible that using purely physical interpretations of trauma may neglect the cognitive and emotional self, relational issues, and the greater meaning of the traumatic experience.

Relational theories of trauma

Relational theories of trauma draw on object relations and attachment theory to explain trauma experiences and symptomology, particularly for traumas that are perpetrated by other individuals. Relational theory views trauma as a disruption of interpersonal schemas, leading to maladaptive perception and function in relationships (Johnson & Lubin, 2010). One example is described by Rubinstein (2015), wherein the intolerable aspect of the traumatic experience is transferred to an internal object-world comprising a victim, abuser, and a rescuer. This relational configuration is then thought to be played out in transference-countertransference reactions throughout the individual’s life. Arikan et al. (2016) found that posttraumatic stress was indirectly influenced by attachment anxiety through the mediator of negative self-cognitions. Another study found correlation between secure attachment and low levels of lifetime PTSD symptoms such as intrusive thoughts, arousal, and avoidance, while dismissive and fearful attachments were correlated with poor psychological adjustment (O’Connor & Elklit, 2008).

Relational theories of trauma suggest that a strong therapeutic relationship, establishment of social supports, and internalization of secure working models of relationships are most important to trauma intervention (Bryant, 2016; Rubinstein, 2015; Schottenbauer et al., 2008). This therapeutic orientation may manifest as a focus on validation, supportive counselling, and development of social supports—possibly at the expense of psychoeducation, regulation skills, behavioural interventions, and physiologically based treatments.

Intrapersonal theories of trauma

The intrapersonal theories of trauma focus on emotion regulation, cognition, identity, and self-concept. Some studies, for example, point to traits such as neuroticism and low cognitive ability as predictors of the development of PTSD (Kindt & Engelhard, 2005). Emotional processing theory posits that failure to recover from trauma is linked to an inability to emotionally engage with the trauma memory and to organize, process, and modify negative beliefs about the world and one’s self following the trauma (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Ehlers and Clark (2000) present a cognitive model of PTSD, which explains that posttraumatic symptoms become persistent when the processing of the trauma leads to a sense of ongoing, serious threat; this perception is maintained through a series of maladaptive behavioural and cognitive strategies. Mazloom et al. (2016) found that metacognitive factors and emotional schema factors were associated with PTSD symptoms such as re-experiencing, avoidance, and increased arousal. Both relationships were mediated by difficulties in emotional regulation. This finding suggests that beliefs about thoughts and emotions may influence traumatized persons’ ability to emotionally regulate, leading to PTSD symptoms. Other models suggest that characteristics of the individual that manifest during the trauma may predict symptoms type and severity. For example, in one exploratory study, peritraumatic guilt and fear were related to re-experiencing symptoms, while peritraumatic anger predicted both re-experiencing symptoms and hyperarousal (Dewey et al., 2014).

These intrapersonal interpretations of trauma would lead the social worker to focus on cognitive-behavioural interventions and emotion regulation skills to support trauma survivors. These approaches, focused primarily on deficits of the individual, may neglect issues of personal meaning, relational impacts, and physiological support for dysregulated individuals.

Interrelatedness of categories

Despite the fact that these theories can be clustered into categories, it is clear that different aspects of trauma (i.e., physical, relational, and intrapersonal) are interrelated. For example, attachment style is highly related to self-concept, the concept of the self-in-the-world, and emotional regulation strategies (Benoit et al., 2010); it has also been shown to relate to cortisol levels in the body (Kidd et al., 2013). This understanding is an example of how the relational can influence the intrapersonal and the physical. Similarly, polyvagal theory explains that bidirectional signaling pathways exist between the viscera such as the heart and muscles in the head and neck responsible for facial expression, listening, and vocalization (Porges, 2018). These pathways imply that emotional experiences linked with visceral activation, such as acute anxiety responses, may directly influence facial expression, tone of voice, and listening capacity. Thus, emotional and physiological states associated with trauma impact relational experiences. Exploration of each cluster of theories eventually reveals a link to both of the others. An organizational framework for trauma theories would need to recognize the three general categories of theories and also acknowledge the complex interplay between them.

Existential theory for clinical practice

Existential theory does not provide a specific, technical approach to clinical therapy. Rather, it has arisen from a long tradition of philosophical thought and operates as a contextual framework that poses deep questions about the nature of life and death, isolation, anxiety, and despair (Zafirides et al., 2013). Existential therapy initially arose in contrast to the predominant reductionist, deterministic approach to psychology of the mid-twentieth century, within the context of the rising humanistic movement (Bauman & Waldon, 1998). Existential therapy is rooted in the psychodynamic approach; the existential therapist sees psychopathology as a defense mechanism against anxiety. However, where a traditional psychodynamic approach recognizes instinctual drives as the source of internal conflict and anxiety, the existential approach sees anxiety as deriving from confrontation with the givens of existence. These defenses reduce one’s capacity for self-awareness and ability to live authentically (Yalom, 1980). Existential therapy focuses on the relationship between the therapist and service user, and views the person as a conscious, responsible being who, while motivated to “become” themself, is in dialectic tension with their own impending death and ultimate sense of meaninglessness of life. The task of existential therapy is to support the person in confronting the anxiety-provoking truths of existence while finding meaning and living authentically (Bauman & Waldon, 1998).

Irvine Yalom’s (1980) Existential Psychotherapy is considered by many to be the most important contribution to the field of existential psychotherapy (Zafirides et al., 2013). Yalom’s interpretation of existentialism revolves around four “existential givens,” or “ultimate concerns,” which are often presented as dichotomies: death vs. life, isolation vs. connection, freedom vs. responsibility, and meaninglessness vs. meaning (Berry-Smith, 2012; Zafirides et al., 2013). According to Yalom, the inevitability of death creates terror for humans, who deeply fear a state of non-being; however, an awareness of death also has the capacity to prompt mindful and authentic engagement in life. Death is also related to existential isolation. Confrontation with death prompts the realization that, ultimately, we cannot die with or for another person. Despite deep connection with others, we fundamentally exist, and cease to exist, in isolation. The concepts of freedom and responsibility imply that humans have responsibility for their perceptions and attributions about their experiences, as well as for their conduct in the world. This realization is both freeing and anxiety producing, because it negates the security of an underpinning structure or fate. Finally, these concerns culminate in the issue of meaning versus meaninglessness. If there is no underlying fate or structure to the world—if we are ultimately responsible for our lives, isolated, and doomed to death—what could possibly be the meaning of life? And yet, a human living without meaning tends to be miserable. Thus, exploration of and creation of meaning is one of the main tasks of existential therapy.

While Yalom (1980) positioned death as the primary concern for humans, often producing overwhelming anxiety (Berry-Smith, 2012), Frankl (1959) identified that finding meaning is the key to resolution of psychological concerns and to overcoming life’s difficulties. Yalom somewhat supports this by weaving the other three existential givens into his discussion of meaninglessness, perhaps indicating that they are somewhat confounded by meaninglessness. Yalom points to several ways in which meaning can provide a pathway out of death anxiety and isolation. Thus, while all four existential givens may underlie presenting issues, creation of meaning may be the key to overcoming these issues.

Existential theory has proven to be flexible enough to be integrated with other theories for the treatment of various conditions. For example, it has been used in a cognitive theory of meaning (Bering, 2003), and has been combined with cognitive behaviour (Corrie & Milton, 2000), mindfulness-based (Harris, 2013), solution-focused (Fernando, 2007), and narrative (Day, 2009) therapies. Maunder and Hunter (2004) have also used an integrated theory of attachment and existentialism to inform treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Existentialism has the potential to add depth of meaning to technically based approaches, resulting in a useful blend of meaning and technique that acknowledges both the complexity of the human condition and the utility of specific evidence-based modalities.

Existential theory in traumatology

The theoretical literature on trauma has made links between the theoretical constructs of existentialism and the nature of trauma experiences. Thomson and Walsh (2010) conceptualize trauma as an existential injury that can result in a loss of sense of self and the shattering of frameworks of meaning. They discuss the existential concept of “the abyss”—the existential void that is experienced when we face our own mortality and the finitude of existence. They posit that trauma forces us to look into the abyss, leading to existential death anxiety. Other authors have drawn upon Yalom’s concept of a boundary situation, a situation in which we are confronted with the ultimate concerns, to conceptualize trauma as an existential experience (Bauman & Waldon, 1998; Du Toit, 2017), while some refer to an existential shattering that destroys the survivor’s defenses against meaninglessness, freedom, isolation, and death (Du Toit, 2017; Hoffman et al., 2013).

Empirical literature, although limited, has also linked existentialism with the nature of trauma experiences and with successful trauma intervention. For example, a positive correlation between existential anxiety and lifetime trauma exposure was found in adolescents who had been exposed to natural disasters (Weems et al., 2016). Existential themes are also identified in pathways to trauma healing. Das et al. (2016) found that the process of meaning-making was instrumental in recovery from childhood sexual abuse. Case studies of veterans have also provided tentative support for the use of logotherapy, a branch of existential psychotherapy, to address anxieties around the four existential givens (Southwick et al., 2006). Thus, the humanistic and flexible nature of existential theory, as well as its conceptual and empirical links to trauma experiences, lends it credibility as a framework integrating a variety of trauma theories.

Towards an existential framework for trauma theory

It is possible to make connections between Yalom’s (1980) ultimate concerns of death, isolation, and freedom with the physical, relational, and intrapersonal categories of trauma theories. Yalom describes the dysphoria and series of defenses of a person with traumatizing life experiences as “a failure of the homeostatic regulation of death anxiety” (p. 207). This statement quite succinctly captures the nature of many of the physical theories of trauma. Findings of multiple studies suggest that PTSD involves shifts in nervous and immune processes, causing ongoing dysregulation of these systems (Speer et al., 2018). Polyvagal theory explains the survival responses of fight, flight, or freeze that are triggered in traumatic situations to protect us from death in the short term, but may result in long term nervous system dysregulation, leading to trauma symptomology (Gupta, 2013). Thus, we may conceptualize the physical response to trauma as a somatic response to death anxiety; ensuing dysregulation leads to an ongoing sense of threat, hyper- or hypo-arousal, and changes to neurological structure, which impact mood and emotion regulation. Similarly, Yalom’s (1980) symptom of dysphoria, as an attempt to disengage from death anxiety, may be likened to dissociative symptoms.

The existential concept of isolation may be seen as a container for the relational theories of trauma. Yalom’s (1980) existential isolation refers to the unbridgeable gulf between the self and any other person, and between the self and the world. Yalom describes isolation as typically hidden behind the curtain of “everydayness” (p. 358); it is only traumatic or extreme circumstances that cause us to see behind the curtain and realize our essential aloneness. Healthy recovery from this experience is described as a sharing of aloneness, such that isolation becomes bearable (Yalom, 1980). Examples of unhealthy attempts to assuage aloneness include existing only in the eyes of others, subsuming others, or searching out sexual bonding without true relationship. All of these relationships are based on survival instead of growth (Yalom, 1980). These themes are similar to those found in the category of relational theories of trauma, such as object relations and attachment theories. For example, there is some evidence that traumatic experiences can damage the internal attachment system, leading to attachment insecurity in traumatized persons (Bryant, 2016). Insecure attachment metrics have also been shown to increase with posttraumatic stress levels and decrease with posttraumatic growth (Arikan et al., 2016). The ideal of secure attachment includes both comfort in being alone and self-reliance, and comfort relying on others (Woodhouseet al., 2015). This ideal is reminiscent of Yalom’s (1980) concept of sharing of aloneness. Furthermore, many of the maladaptive defenses against aloneness Yalom describes are similar to expressions of insecure attachment, such as lack of self-other differentiation (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005).

Finally, the existential concept of freedom may be linked to the intrapersonal theories of trauma. Yalom (1980) states that the universe is contingent and that there is no underlying pattern or causality. He describes the experience of the awareness of freedom as “groundlessness” (p. 221). The random-seeming nature of trauma is certainly in line with the contingent nature of Yalom’s world. For example, the groundlessness experienced upon realization of the lack of structure in the world may be related to derealization symptoms. Trauma survivors may experience derealization as a distorted experience of reality, including feelings of unreality and detachment from the world and from others. Yalom counters the reality of freedom with the imperative of responsibility. He states that, given arbitrary and unpredictable circumstances, we have responsibility for our conduct and experience of the world. In the healing of anxieties around freedom, Yalom suggests that therapy focuses on the future, the ability to take responsibility in the future, and the use of leverage-producing insights that increase self-knowledge to catalyze the willing of alternative experiences. These insights are characterized by a sense of agency, and are change-focused, such as “only I can change the world I have created” (p. 340). These suggestions are paralleled in the field of traumatology by emotion regulation, cognitive, and information processing theories of trauma. These theories point to the willful adjustment of emotional, cognitive, and learning experiences through use of mindfulness, cognitive modifications, exposure therapies, and stress and affect management skills to resolve symptoms of trauma (Brewin & Holmes, 2003; Brousse et al., 2011; Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

Central to all of the aspects of existence is meaning. Yalom (1980) describes various levels of meaning ranging from a sense of coherence, to a sense of life’s purpose, to cosmic meaning, such as a divine plan. He sees a human as a “meaning-giving subject” (p. 462), while Frankl (1959) contends that meaning exists to be found, rather than created. These variations in the nature of meaning recognized by existentialism provide flexibility to allow social workers to adjust meaning-based interventions based on a person’s needs and worldviews. As explained above, Frankl (1959) and Yalom (1980) describe meaning as linked to all other existential concerns and identify meaning as a pathway to healing from death anxiety, isolation, and the groundlessness associated with freedom. For example, Yalom posits that life satisfaction mitigates death anxiety, and that through infusing life with meaning, we may begin to gain life satisfaction. Empirical evidence also suggests that meaning making is a critical element in posttraumatic recovery and growth (Das et al., 2016; Schuman, 2016; Southwick et al., 2006).

The conclusion of this integration of Yalom’s existentialism and current trauma theories is a framework, illustrated in Figure 1. This figure illustrates the three categories of trauma theories (i.e., physical, relational, and intrapersonal) as interconnected. The existential givens surround this triad, serving as containers for the theory categories. Meaning is placed at the centre and can be accessed from each of the three groupings as a pathway toward healing.

Figure 1

An integrated existential framework for trauma theory

Issues in theory integration and existential theory

A critique of theory integration in general is that it can become overwhelming for a clinician to attend meaningfully to all aspects encompassed by the framework (Sotskova & Dossett, 2017). This critique is, however, also reflective of the very strength of the integrated framework: all aspects are recognized. A careful, systematic application of the totality of the model over a number of sessions must be used to attend to the expansiveness implied by the model while remaining focused on specific, manageable areas in each session. For a phenomenon such as trauma, with such a breadth of potential impacts, a comprehensive framework may be utilized to avoid the trap of focus on one aspect at the expense of others.

The application of existential theory to any issue is not without its critics. A critique of existentialism is that it is founded largely in Western belief systems, and may, therefore, not be applicable to other cultural backgrounds (Berry-Smith, 2012). For example, the concept of existential isolation may not be compatible with collectivist cultures, or cultures that hold beliefs of fundamental interconnectedness (Berry-Smith, 2012). Death anxiety may not be relevant for cultures that celebrate and honour death; however, exploration of the meaning of death may be relevant. Social workers applying the model will need to assess its relevancy to each person, as with any model, and ensure that cultural sensitivity is employed during its application.

It has been suggested by existential theorists that the application of existential theory to psychotherapy cannot be a casual experience (Willig et al., 2015). Because existential psychotherapy does not simply provide a suite of techniques, the practitioner cannot “know” existential psychotherapy; being an existential psychotherapist is a way of being in the world that includes ongoing dialogue and engagement with theory and philosophy with one’s contemporaries, belief in the equality in the service user–therapist relationship, and a commitment to pluralism (Willig et al., 2015). There are two risks to existential theory that could emerge from this concern: firstly, that by general use, existentialism will become divorced from its rich philosophy; and, secondly, that social workers who use existential theory perfunctorily may not access its full and unique therapeutic value. In the complex world of trauma theory, is it simply too much to ask of social workers to both understand technique-based modalities and develop a solid philosophical foundation in existentialism?

Finally, characteristics of the person and stage of treatment must be accounted for in the application of this or any other framework or theory. In a state of extreme dysregulation or depending on worldview, the abstractness of existential concepts may not be accessible to some people (Johanson, 2010). In such cases or stages, skills in affect and body-based regulation strategies cannot be neglected in favour of philosophy. Thus, a social worker must be prepared to set aside the deeper existential component of the framework to attend to the physical, intrapersonal, and relational concerns that are immediate and accessible.

Implications of an existential framework for trauma theory

Existential theory presents an opportunity for social workers to challenge the modality-based approach to trauma therapy. By recognizing the full range of the human experience, existential theory may remind social workers that there are many avenues through which to access trauma experiences. A guiding framework based on existential theory may create space for a variety of technical modalities, underpinned by a humanistic exploration of deep meaning and experience. It captures the profundity of the traumatic experience while attending to a breadth of symptoms, impacts, and therapeutic approaches. Social workers struggling to “do” eclectic practice may use such a framework to give a sense of coherence to an otherwise overwhelming selection of theories and modalities. As noted by Bauman and Waldon (1998) in their critique of eclecticism, “[w]ithout theory, the practicing counselor moves from the level of a true professional to the level of a technician” (p. 13). Perhaps existential theory has the potential to move eclectic trauma therapy from the level of the technical to the professional.

While the potential of an existential framework for trauma theory is arguable, it is acknowledged that, at this point, it is theoretical. Although some empirical research links existential theoretical constructs to trauma experiences and treatment (Southwick et al., 2006; Weems et al., 2016), some researchers do not find association between death anxiety, meaninglessness, and trauma (Floyd et al., 2005). More empirical evidence is desirable to support this theoretical connection.

Research on the efficacy of an existential framework for trauma may present challenges for researchers and existential practitioners. Lantz (2004) describes the fundamental conflicts between empiricism and existential philosophy. Firstly, and perhaps most critically, existentialism rejects the idea of treatment as the cause of change. In keeping with the existential concept of freedom, change will occur when and where a person sees and accesses their freedom, irrespective of treatment intervention (Yalom, 1980). Thus, measurement of outcomes in empirical studies would be more indicative of a person’s use of freedom than treatment efficacy (Lantz, 2004). Secondly, existentialism is more concerned with individual experience than statistical outcomes. Study designs, such as randomized control trials, are not aligned with the philosophy of existentialism, which tends to value single subject designs, case studies, and field studies (Lantz, 2004). Finally, there is the issue of philosophical integrity. Given the assertion that existential practitioners cannot “know” existentialism, but must rather “be” existentialist (Willig et al., 2015), it may be difficult for empirical research to define what does or does not constitute an existential therapeutic approach. Thus, although existential theory poses opportunities for practice, and for the use of eclectic and integrated practice with trauma survivors, empirical assessment of the approach poses challenges for research.

Conclusion

This paper presents an integrated existential framework for trauma theory that draws on the flexibility of existential theory and the congruency of its theoretical constructs with the body of existing trauma theory. The result is a comprehensive framework that addresses the physical, relational, and intrapersonal aspects of trauma, underpinned by an existential perspective. Existentialism provides an important supplement to more commonly applied trauma theories, as it acknowledges the intangible impacts of trauma on meaning, mortality, and identity. The objective of this framework is to provide structure to the overwhelming number of trauma theories and treatment modalities while allowing flexibility for social workers to fit familiar theories and modalities into an existential practice. The framework poses some challenges to practice and research—particularly, how to remain respectful of existential theory’s rich philosophical history while using it and studying it in a positivist environment. However, if used effectively, the framework may address the depth of the impacts of trauma, and contain the breadth of theories used by social workers to conceptualise and treat trauma, resulting in well-structured, professional eclectic practice.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Kaitlin Wilmshurst is a recent graduate of the Master of Social Work program at Lakehead University. This paper placed first in the English submissions of the 2019 Student Competition.

Bibliography

- Admon, R., Milad, M. R., & Hendler, T. (2013). A causal model of post-traumatic stress disorder: Disentangling predisposed from acquired neural abnormalities. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(7), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.05.005

- Arikan, G., Stopa, L., Carnelley, K. B., & Karl, A. (2016). The associations between adult attachment, posttraumatic symptoms, and posttraumatic growth. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2015.1009833

- Bauman, S., & Waldon, M. (1998). Existential theory and mental health counseling: If it were a snake, it would have bitten! Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 20(1), 13–28.

- Benoit, M., Bouthillier, D., Moss, E., Rousseau, C., & Brunet, A. (2010). Emotion regulation strategies as mediators of the association between level of attachment security and PTSD symptoms following trauma in adulthood. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 23(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800802638279

- Bering, J. M. (2003). Towards a cognitive theory of existential meaning. New Ideas in Psychology, 21(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0732-118X(03)00014-X

- Berry-Smith, S. (2012). Death, freedom, isolation and meaninglessness, and the existential psychotherapy of Irvin D. Yalom (Masters dissertation Auckland University of Technology).

- Brewin, C. R., & Holmes, E. A. (2003). Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(3), 339–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3

- Briere, J., & Scott, C. (2015). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Brousse, G., Arnaud, B., Durand-Roger, J., Geneste, J., Zaplana, F., Bourguet, D., & Blanc, O. (2011). Management of traumatic events: Influence of emotion-centered coping strategies on the occurrence of dissociation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 7, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S17130

- Bryant, R. A. (2016). Social attachments and traumatic stress. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.29065

- Corrie, S., & Milton, M. (2000). The relationship between existential-phenomenological and cognitive-behaviour therapies. European Journal of Psychotherapy, Counselling & Health, 3(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642530050078538

- Das, S., Pramanik, S., Ray, D., & Banerjee, M. (2016). The process of meaning making from trauma generated out of sexual abuse in childhood. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 366–370.

- Day, K. W. (2009). Violence survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: Treatment by integrating existential and narrative therapies. Adultspan Journal, 8(2), 81–91.

- Dewey, D., Schuldberg, D., & Madathil, R. (2014). Do peritraumatic emotions differentially predict PTSD symptom clusters? Initial evidence for emotion specificity. Psychological Reports, 115(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2466/16.02.PR0.115c11z7

- Dick, A. M., Niles, B. L., Street, A. E., DiMartino, D. M., & Mitchell, K. S. (2014). Examining mechanisms of change in a yoga intervention for women: The influence of mindfulness, psychological flexibility, and emotion regulation on PTSD symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(12), 1170–1182. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22104

- Du Toit, K. (2017). Existential contributions to the problematization of trauma: An expression of the bewildering ambiguity of human existence. Existential Analysis, 28(1), 166–175.

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0

- Fernando, D. M. (2007). Existential theory and solution-focused strategies: Integration and application. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 29(3), 226–241.

- Floyd, M., Coulon, C., Yanez, A. P., & Lasota, M. T. (2005). The existential effects of traumatic experiences: A survey of young adults. Death Studies, 29(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180490483463

- Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20

- Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

- Gupta, M. A. (2013). Review of somatic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 25(1), 86–99. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.736367

- Harris, W. (2013). Mindfulness-based existential therapy: Connecting mindfulness and existential therapy. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 8(4), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2013.844655

- Herold, B., Stanley, A., Oltrogge, K., Alberto, T., Shackelford, P., Hunter, E., & Hughes, J. (2016). Post-traumatic stress disorder, sensory integration, and aquatic therapy: A scoping review. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 32(4), 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2016.1166355

- Hoffman, L., Cleare-Hoffman, H. P., & Vallejos, L. (2013). Existential issues in trauma: Implications for assessment and treatment. Paper presented at Developing Resiliency: Compassion Fatigue and Regeneration, 121st Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, HI. https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.1.5166.2881

- Johanson, G. J. (2010). Response to: “Existential theory and our search for spirituality” by Eliason, Samide, Williams and Lepore. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 12(2), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349631003730100

- Johnson, D., & Lubin, H. (2010). Principles and techniques of trauma-centered psychotherapy (1st ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Kidd, T., Hamer, M., & Steptoe, A. (2013). Adult attachment style and cortisol responses across the day in older adults: Attachment and day cortisol in older adults. Psychophysiology, 50(9), 841–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12075

- Kindt, M., & Engelhard, I. M. (2005). Trauma processing and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 36(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.11.007

- Kwapis, J. L., & Wood, M. A. (2014). Epigenetic mechanisms in fear conditioning: Implications for treating post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends in Neurosciences, 37(12), 706–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.005

- Lantz, J. (2004). Research and evaluation issues in existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 34(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-004-2527-5

- Leddick, K. H. (2018). Making good use of combined therapeutic modalities: Discussion of “Somatic Experiencing.” Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 28(5), 610–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481885.2018.1506223

- Lipov, E., & Kelzenberg, B. (2012). Sympathetic system modulation to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A review of clinical evidence and neurobiology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 142, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.011

- MacNamara, A., Rabinak, C. A., Kennedy, A. E., Fitzgerald, D. A., Liberzon, I., Stein, M. B., & Phan, K. L. (2016). Emotion regulatory brain function and SSRI treatment in PTSD: Neural correlates and predictors of change. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(2), 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.190

- Malarbi, S., Abu-Rayya, H. M., Muscara, F., & Stargatt, R. (2017). Neuropsychological functioning of childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 72, 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.11.004

- Maunder, R., & Hunter, J. (2004). An integrated approach to the formulation and psychotherapy of medically unexplained symptoms: Meaning- and attachment-based intervention. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 58(1), 17–33.

- Mazloom, M., Yaghubi, H., & Mohammadkhani, S. (2016). Post-traumatic stress symptom, metacognition, emotional schema and emotion regulation: A structural equation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.053

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Attachment theory and emotions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment-related dynamics of emotional reactions to relational events. Personal Relationships, 12(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00108.x

- Mitchell, K. S., Dick, A. M., DiMartino, D. M., Smith, B. N., Niles, B., Koenen, K. C., & Street, A. (2014). A pilot study of a randomized controlled trial of yoga as an intervention for PTSD symptoms in women: Yoga for PTSD in women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21903

- Nolan, C. R. (2016). Bending without breaking: A narrative review of trauma-sensitive yoga for women with PTSD. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 24, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.05.006

- O’Connor, M., & Elklit, A. (2008). Attachment styles, traumatic events, and PTSD: A cross-sectional investigation of adult attachment and trauma. Attachment & Human Development, 10(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730701868597

- Porges, S.W. (2018). Polyvagal theory: A primer. In S.W. Porges, & D. Dana (Eds.), Clinical applications of the polyvagal theory: The emergence of polyvagal-informed therapies (1st ed., pp. 50–69). W.W. Norton & Company.

- Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Steel, Z., Newby, J., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2015). Physical activity in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017

- Rubinstein, T. (2015). Relational theory: A refuge and compass. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(4), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0523-8

- Schottenbauer, M. A., Glass, C. R., Arnkoff, D. B., & Gray, S. H. (2008). Contributions of psychodynamic approaches to treatment of PTSD and trauma: A review of the empirical treatment and psychopathology literature. Psychiatry – Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 71(1), 13–34.

- Schuman, D. (2016). Veterans’ experiences using complementary and alternative medicine for posttraumatic stress: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Social Work in Public Health, 31(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2015.1087915

- Sotskova, A., & Dossett, K. (2017). Teaching integrative existential psychotherapy: Student and supervisor reflections on using an integrative approach early in clinical training. The Humanistic Psychologist, 45(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000049

- Southwick, S. M., Gilmartin, R., Mcdonough, P., & Morrissey, P. (2006). Logotherapy as an adjunctive treatment for chronic combat-related PTSD: A meaning-based intervention. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 60(2), 161–174.

- Speer, K., Upton, D., Semple, S., & McKune, A. (2018). Systemic low-grade inflammation in post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Inflammation Research, 11, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S155903

- Thompson, N., & Walsh, M. (2010). The existential basis of trauma. Journal of Social Work Practice, 24(4), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650531003638163

- Vachon, M., Bessette, P. C., & Goyette, C. (2016). “Growing from an invisible wound”: A humanistic-existential approach to PTSD. In G. El-Baalbaki, & C. Fortin (Eds.), A multidimensional approach to post-traumatic stress disorder—from theory to practice (pp. 179–203). Intech. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/64290

- Wang, Q., Shelton, R. C., & Dwivedi, Y. (2018). Interaction between early-life stress and FKBP5 gene variants in major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 422–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.066

- Weems, C. F., Russell, J. D., Neill, E. L., Berman, S. L., & Scott, B. G. (2016). Existential anxiety among adolescents exposed to disaster: Linkages among level of exposure, PTSD, and depression symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 466–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22128

- Willig, C., Berguno, G., Cooper, M., Milton, M., du Plock, S., & Spinelli, E. (2015). SEA conference – round table and open forum: “The challenge to theory in existential psychotherapy.” Existential Analysis. Journal of the Society for Existential Analysis, 26, 225–236.

- Woodhouse, S., Ayers, S., & Field, A. P. (2015). The relationship between adult attachment style and post-traumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 35, 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.07.002

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Harper Collins Publishers.

- Zafirides, P., Markman, K. D., Proulx, T., & Lindberg, M. J. (2013). Psychotherapy and the restoration of meaning: Existential philosophy in clinical practice. In K. D. Markman, T. Proulx, & M. J. Lindberg (Eds.), The psychology of meaning (pp. 465–477). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14040-023

Liste des figures

Figure 1

An integrated existential framework for trauma theory