Résumés

Abstract

This article begins by providing a narrative account of the (re)discovery of Union Films, the leading producer of left-wing documentaries in the United States in the immediate post-World War II era. Because of the Red Scare and blacklist, the organization has gone unmentioned in histories of documentary and radical filmmaking. The Orphan Film Movement has provided a cultural formation that has enabled this reclamation to unfold, providing a synergy between scholars, archives and labs. The question is then raised: where does the Union Films Project go from here?

Résumé

La première section de cet article retrace l’histoire de la (re)découverte de Union Films, la principale maison de production de films documentaires de gauche aux États-Unis au lendemain de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale. Le maccarthysme et la liste noire ont contribué à écarter ce collectif de producteurs de l’histoire du cinéma documentaire et engagé. Le mouvement qui s’est constitué autour des « films orphelins » a fourni une assise culturelle qui a permis de corriger cette situation, créant une synergie entre les chercheurs, les archives et les laboratoires. La question qui se pose désormais est la suivante : quelle direction le Union Films Project doit-il prendre ?

Corps de l’article

(Re)discoveries frequently begin obliquely: we are trying to find out about one thing—and then get distracted by something else. Take, for instance, Union Films: a left-wing film collective that made over two dozen non-fiction films between 1946 and 1953. The most important organization producing radical documentaries in the United States during the immediate post-World War II era, Union Films has gone unmentioned in every general history of documentary as well as various accounts of left-wing filmmaking. Even now, it remains essentially invisible. My first encounter with Union Films occurred in 1998 as I was co-curating a centennial retrospective of films featuring Paul Robeson (1898-1976), who narrated and briefly appeared in People’s Congressman, a 1948 campaign film for Vito Marcantonio. I was trying to establish the production credits for this obscure documentary that had mysteriously appeared in the Museum of Modern Art’s film archive. The film itself only indicated that it was a presentation of the American Labor Party and a Union Films production: the latter seemed so generic I gave it little thought. A file for the film in MoMA’s Film Study Center contained a single sheet of paper, which has since been removed. It stated, “Jay Leyda knows who made this film.” But Jay Leyda (1910-1988) had been dead for ten years, and it would be ten more before I found the answer to the question I could have asked my mentor if he had still been alive.[1]

Figure 1

Hoping a presentation of People’s Congressman at the 6th Orphan Film Symposium (New York University, March 26-28, 2008) might give me some leads to a question that had stymied me for a decade, I asked Dan Streible if he would let me screen People’s Congressman at that event. He not only agreed but partnered with the laboratory Cineric, Inc., which committed to making a new print for the MoMA as an in-kind contribution to facilitate the Museum’s cooperation. And yet the event nearly did not happen. As Dan e-mailed me:

I was at the Columbia Film Seminar tonight, where [MoMA’s film archivist] Steven Higgins told me that the print of the People’s Congressman will definitely NOT be ready for Orphans. He asked to cancel the screening and aim for 2010 Orphans. Seriously. . . . Your thoughts?[2]

A tardy response on my part acknowledged the inevitable—no new print meant no screening. With nothing new to contribute on my end, perhaps it was all for the best. But the stars seemed to have something else in mind, as Dan soon informed me:

After our last round of emails, I gave a lot of thought to what to do with the Robeson film and talk long scheduled for Orphans 2008. After not hearing from Higgins for a few days about whether or not what they had would meet Cineric’s offer, I was inclined to say “let’s wait and do it right in 2010.” It would also give us some time in a crowded schedule.

THEN, late last night, I discovered a flurry of stacked up emails that I did not realize I’d been copied on. Apparently the film is already at Cineric or on its way. (Who would’ve guessed that MoMA could act so fast after no action for years, followed by an initial cancellation of the Orphans screening?)

Assuming that all goes OK with the lab and we actually DO have a new print to project at Orphans, I will stick to my promise to screen it. Everyone here at NYU tells me they are dying to see it, esp. to keep your Robeson/Orphans presentations in continuity and as “festival highlights.”[3]

Cineric, Inc. not only made the deadline, it made me a DVD viewing copy. Given Dan’s generosity and the last minute heroics of all parties, I definitely did not want to go before a room full of Orphanistas[4] empty handed; and yet eight days before my presentation I still had nothing new of substance to say. I popped the newly arrived DVD into my computer thinking I would have to rely on my skills in close analysis. There it was again: “A Union Films production.” In desperation I googled “Union Films,” and in one of those Internet miracles a single hit provided me with a breakthrough—a link to Lichtenstein (2005). Soon I was talking to—and meeting—Charlotte and Tony Marzani, the widow and son of Carl Marzani who was the progenitor of Union Films. They were amazingly generous and supportive of my interests. I visited their home and received a tour of their basement, filled with books, some films and various ephemera. As a result I had plenty to talk about at Orphans 6. In turning that presentation into a substantial essay, I used the Internet to track down the family members of other people connected to Union Films. I soon stumbled across one Eric Glandbard who was working at a local television station on the North Fork of Long Island: his e-mail address was e-the-red@mac.com. I sent Eric an e-mail:

Dear Eric,

This is a little bit of a shot in the dark. Are you related to Max Glandbard, who directed theater and worked in movies after World War II? I am writing about his work on a series of documentaries and it is hard to find out much about him. Thought you might know.[5]

Three days later I received a response:

Max was my father. He died in 1987. I’d be happy to help in any way I can.[6]

Max directed most of the Union Films productions, so the acorn had not fallen far from the tree. Eric and I talked on the phone, and I e-mailed him some questions and waited for a response:

I’ve been a bit distracted with work, etc. Hope you’re not working to a deadline.

And your questions remind me how little I know about my father’s life—he wasn’t particularly loquacious, and unfortunately like many children I wasn’t terribly interested in his history until he was dead and it was too late . . .

I’ve started composing a very brief biography for you, which I’ll send soon—and I do have some documents that I’ve never really sorted through that I can access in a few weeks that might fill in some blanks.[7]

The information arrived as promised—in time to provide my essay with a much richer Glandbard biography. I also stumbled across historian J. Fred MacDonald who delved into his private archives and located a number of Union Films titles, providing me with reference copies that helped me to piece together a more complete history of the collective. Chris Horak enabled me to view a digitized version of UCLA Film and Television Archive’s 16mm print of Industry’s Disinherited (1949). A clearer picture of Union Films and its core members was beginning to emerge.

Stepping back from my own process of discovery, it is easy to see that others have had somewhat similar encounters with Union Films. There had been earlier instances of (re)discovery. Gary Crowdus had worked at Cinema Guild (the source for Charlotte Marzani’s phone number) when it had distributed three of the group’s films. He and Lenny Rubenstein had also conducted an interview with Marzani, which appeared in Cineaste (Crowdus and Rubenstein 1976); with Crowdus as its editor in chief, these two efforts were obviously co-coordinated. Moreover, Carl Marzani had published a multi-volume memoir in the mid-1990s, with plenty of information about Union Films. By January 2001 Rick Prelinger had uploaded two important Union Films documentaries onto the Internet Archive, as part of the Prelinger Archives: Deadline for Action (1946) and The Great Swindle (1948).[8] As he explained:

I was aware of Deadline for Action and The Great Swindle from the 1970s on, as they were distributed by American Documentary Films and I had also read the Cineaste interview with Carl Marzani. The prints in our archives came from the reference and preview print collection at Jam Handy Organization, known internally as the “Sales Examples” collection, which collected them as examples of films representing a point of view opposed to that of their corporate clients, especially GE and GM.[9]

Rick subsequently provided entries for three Union films in The Field Guide to Sponsored Films (2006)—and generously contributed frame enlargements for my essay. Other film prints had likewise found their way into various archives, but no one had brought these disparate elements together. They had not exceeded a threshold of value and visibility that would integrate this collective into the existing historiography. To overcome this threshold required a density of primary source materials, a sustained and coherent story, and clear connections to, or meaningful relations with, the standard histories. In short, an adequate portrait of Union Films was needed, not only to secure its proper place in the history of American documentary and to provide an essential framework for viewing its many films but also to reconfigure several disparate (but ultimately related) histories in important ways.

From the very outset, my investigations of Union Films depended on the generosity of both public and private archives. Engagements with these individuals and institutions would continue to be crucial as I sought to expand my understanding of the company’s history and to generate new levels of visibility for its motion picture productions. Moreover, at the risk of revealing a too self-serving secret, finding ways to show its films to others has been one way to show them to myself. Nevertheless, if archives and repositories have played a crucial role in this process, it has sometimes been a complicated one. For instance, the Marzani family insisted that Carl had donated a set of 16mm prints to the Tamiment Library at NYU along with his papers. The Tamiment Library, however, claimed to have no record of such films: they had seemingly vanished. Moreover, while prints of Union films were at the Library of Congress and other archives, it was not clear that they would receive the attention necessary to rescue them from vinegar syndrome.

Figure 2

My publication of an article on Carl Marzani and Union Films in a special issue of The Moving Image edited by Dan Streible in 2009 proved to be an important catalyst for future undertakings. Certainly the process of writing it brought me in closer contact with the Marzani and Glandbard families. My conviction that the Union Films collective was important to the history of American documentary and my queries for information had caused Eric Glandbard to finally look at his father’s papers in the family archive—some twenty years after Max’s death. On July 10, 2009, Eric sent me an e-mail:

Well, I kinda let the ball drop I guess. I was planning to get back to you as soon as I got my hands on the stuff I’d boxed up after my father died—but for one reason or another, that didn’t happen until last week.

And amongst the boxes of mildewed tax records and copies of the dozens of plays and hundreds of song lyrics my father had composed on his commute into and out of the city, there was a box of old film. It was mostly moldy home movies, but lo and behold in the bottom—three 16mm films reels—in pretty good shape, it seems—from Union Films—one called “Our Union,” one called “project 113,” both on large reels, and a smaller reel in a can saying “civil rights” and the title on the film header is “The Investigators.”

I don’t know whether you’re still working on this project, or if these films interest you, but if you’re keen on it, I’d be happy to give them to you.[10]

His e-mail was exciting for several reasons. First, because Marzani had been convicted of concealing his communist past just as Our Union (1947) was being completed, there had been complete silence about the role of Union Films in the making of this documentary on the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America (UE). Glandbard’s copy offered further confirmation that Our Union was made by Union Films.[11] Moreover, that Max kept a copy indicates that he had become a prominent member of that group by the time this documentary, its second production for the UE, was made. Second, I had been able to see a bad reference copy of The Investigators (1948) through the courtesy of Fred MacDonald. It was a remarkable picture that could spark broad interest in the Union Films collective. Coming into possession of these films would make me a stakeholder in the Union Films saga. Even though I planned to turn them over to the Yale Film Study Center, such a donation would give me direct access to these prints and be a boon to the cause. And finally, what was “project 113”? (It turned out to be Industry’s Disinherited.) So a few weeks later I took a ferryboat from New London, Connecticut to Orient Point, New York. Eric met me at the dock, I took him to lunch (or was it the other way around?), and at the end of our meal he handed me the box of film prints—not just any prints but the director’s prints. I took them back to the Yale Film Study Center where we quickly established that at least four of the titles were Union Films productions.[12]

Now comes a slightly awkward moment in this story. I quickly called the Marzanis, but what I thought would be joyous news came in the middle of a family crisis. Charlotte was moving into a much smaller apartment and her basement, which housed boxes of Carl’s many publications, was being emptied into a dumpster. Given that Charlotte is a writer and Tony is a bookseller (and theatre historian), the traumatic nature of this event is easy to imagine. Their trauma almost became mine, for the film prints in her basement were headed into the dumpster as well. If I had called one or two days later, they would have been gone. Fortunately they gave me a few days to drive to New York and take possession of the prints. As a result the Yale Film Study Center also has the Carl Marzani Film Collection, which includes a fine grain master of Deadline for Action—the documentary that eventually sent Marzani to prison for three years—and another copy of The Investigators.

At the 7th Orphan Film Symposium (New York University, April 7-10, 2010), I worked with Dan Streible to show The Investigators. The Yale Film Study Center now had two 16mm copies, one from Glandbard and one from Marzani. Although the Marzani print was warped and otherwise in poor condition, the Glandbard print was in excellent shape. We ended up showing an HD-CAM copy, transferred from Glandbard’s 16mm print, which was done pro bono by the Library of Congress for the Orphans screening.

The screening of The Investigators seemed destined to be a big event, in part because it was capable of bringing together four or more families whose parents or grandparents worked on the film. Tony Marzani had told me that, according to family legend, Herschel Bernardi had appeared in a Union Films production. When I found a photo of Michael Bernardi on the Web, I was excited because he looked just like the lead investigator in the film. I joined Facebook so I could ask Michael if they were by any chance related. Indeed Michael is Herschel’s son—and an actor living in Los Angeles. The script for The Investigators was attributed to “Lewis Allan,” the pen name for Abel Meeropol, who later adopted the sons of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. I am a big fan of Ivy Meeropol’s documentary Heir to an Execution (2004): If she or some other family members were in New York, I thought they might enjoy seeing this rendition of their grandfather’s/father’s efforts. Indeed, if the Full Frame Film Festival had not been going on at Duke University that weekend, Ivy would have attended.[13] Another granddaughter—Rachel Meeropol—was working at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and I thought it was something more than coincidental that The Investigators was presented by a somewhat similar organization, the Civil Rights Congress (CRC). I also wanted to reprint a playscript of The Investigators, which I had located in the McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University, and this put me in touch with the older generation of Meeropols—the sons Michael and Robert.[14] They kindly agreed, and in the process I learned that there were still other variant scripts for The Investigators—one of which was published in The New Masses—a lefty cultural journal.

Figure 3a

Frame enlargement from The Investigators (1948).

Figure 3b

Frame enlargement from The Investigators (1948).

Figure 3c

Frame enlargement from The Investigators (1948).

My program notes for the film[15], reprinted here, explore the evolving versions of the ur text:

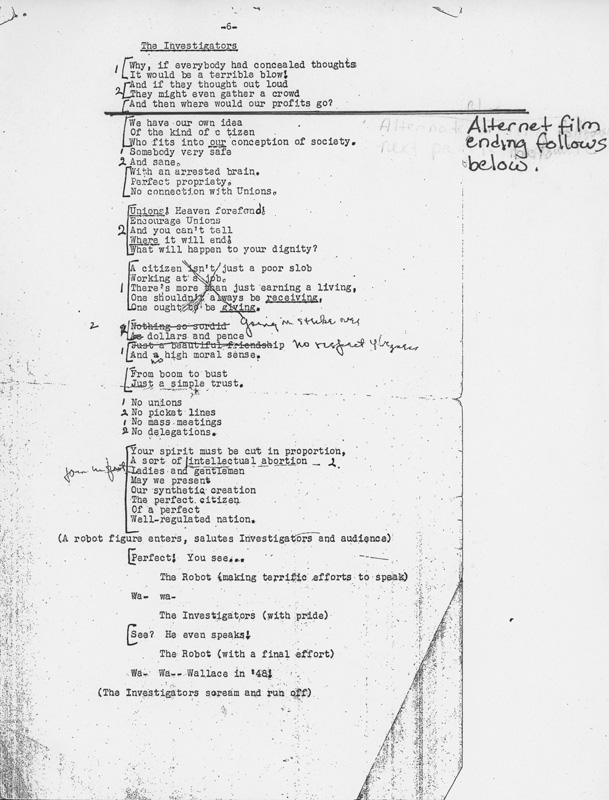

The Investigators

Produced by Carl Marzani; directed by Max Glandbard; script by Abel Meeropol (as Lewis Allan/Lewis Allen); music by Serge Hovey; cinematography by Victor Komow; sound by Richard Patton [Andy Cusick?]; performed by the John Lenthier Group, featuring Herschel Bernardi. A Civil Rights Congress Presentation of a Union Films Production. Released: July 1, 1948. Screening an HD-CAM transfer by the Library of Congress, from a 16mm print in the Max Glandbard Collection, Yale Film Study Center (New Haven, Ct.). 10 mins.

The Investigators brought together a group of remarkable left-wing artists during a final post-World War II, Popular Front burst of cultural activity. Not surprisingly, however, this 10-minute musical farce became an orphaned film. It suffered from the Red Scare just like its creators and their colleagues. The blacklist drove them apart as they struggled with job insecurities, exile, stress-related heart attacks and prison. Producer Carl Marzani never mentioned the picture in his five-volume memoir (Marzani 1992-1995 and 2002). The sons of Abel Meeropol, Michael and Robert, were unaware of either the film or the playscript reproduced in this program. Max Glandbard, who was surprised to have escaped the blacklist and so continued working in film and television, never talked about The Investigators though he kept a 16mm film copy of it in his personal collection—which he passed on to his son Eric. Virtually forgotten, The Investigators was never abandoned. Collectively the Marzani, Glandbard and Meeropol families made the Orphans 7 screening possible and turned this occasion into a kind of reunion.

Union Films was an informal collective: its key members were Marzani, Glandbard, Vic Komow and Charles Patton/Andy Cusick, who made over two dozen documentaries and campaign films between 1946 and 1953. For most of the time, they worked out of the Union Films studio: a brownstone on 111 West 88th Street, which Marzani had bought early in 1948 when he moved back to New York City. With Marzani in charge and the UE providing the necessary funding, Union Films quickly established its reputation with Deadline for Action (released in September 1946), a forty-minute documentary that took forceful aim at American corporations, particularly General Electric. Marzani, however, was made to pay a price and was quickly indicted for concealing his past ties to the Communist Party. Convicted in May 1947, he remained largely free on appeal and stayed busy making films until he was sent to prison in March 1949. When Union Films began to put credits on its films—and The Investigators is the earliest available Union Films production that has such credits—his name never appeared, principally because the explicit association of a “convicted red” would have curtailed distribution and exhibition opportunities as well as financing.

The making of The Investigators raises a series of unanswered questions. How was the Civil Rights Congress involved in The Investigators? Founded in April 1946, the CRC focused much of its efforts on the legal defence of labour radicals, with Marzani’s appeals providing one of its early cases (Horne 1988, pp. 104-5). Perhaps the CRC helped to find funding for the film. Again, what was the nature and extent of Union Films’ collaboration with Abel Meeropol and Serge Hovey? Likewise, how did the John Lenthier Group come into contact with Union Films and what are the names of the actors other than Herschel Bernardi? In fact, although Union Films worked in a range of documentary forms, its staff all had extensive experience in the theatre (including former actress Edith Emerson who was married to Carl and played a key behind-the-scenes role in the group).

As an artist, Abel Meeropol is perhaps best known for the words and music of “Strange Fruit,” which achieved iconic form as sung by Billie Holiday, and the lyrics of “The House I Live In,” sung most memorably by Frank Sinatra and Paul Robeson. Meeropol was, moreover, remarkably productive—and forcefully political. His poetry often appeared in The New Masses, and among his many works in the late 1940s was “The Ballad of the Hollywood Ten” (Allan 1946a and 1946b; Baker 2002). Since he often reworked his lyrics to fit changing circumstances, there are at least four somewhat different versions of The Investigators. An initial version appeared in a July 1946 issue of The New Masses, while a later version was published by the National Education Committee of the Jewish Peoples Fraternal Order (Allan 1946; Baker 2002, fn76). The version reprinted here (Fig. 4) is a typescript for the Chicago Arts Committee for Wallace, dated June 1948. It had been judiciously cut and further reworked for the film. The New Masses version focused on the theme of education, as The Victim demanded “academic freedom” rather than “higher wages” and “no discrimination” (Meeropol’s day job had been as a high school teacher). The Chicago Arts Committee for Wallace playscript and the film both replace The Straw Man with a robot and have electoral politics in mind. (A title that appeared at the end of some prints of this film told audiences to vote for progressive candidates.) The film version is tighter than the Chicago Arts playscript, and I have noted both the excisions as well as a few limited additions in the margins in the pages that follow. The biggest differences between the New Masses version, the Chicago Arts version and the Union Films version are in the endings, which are apparent from the texts themselves: In the New Masses version, “The Investigators” introduce “the perfect teacher”—a man made of straw or “Straw Man”; in the playscript they introduce a robot who proves to have a mind of his own and calls for “Wallace in ’48”; while in the film version, the robot is programmed to agree completely with “The Investigators.”

In my introductory remarks at Orphans 7, I reminded participants that the Marzanis were convinced that Carl had given a set of 16mm film prints to the Tamiment Library at NYU when he deposited his papers in 1994.[16] This declaration eventually bore fruit. Several months later I received the following e-mail from Alice Moscoso:

Sir,

I work as the Moving Image Preservationist at NYU Libraries and have collaborated with Dan Streible on various preservation/access projects over the past three years.

Following your great presentation at Orphans this year, I contacted the Tamiment Library at NYU Libraries and received from the curator, Erika Gottfried (copied on this email as well) five 16mm reels and one video from the Marzani collection.

We inspected the reels in the Preservation department and here is the list of the materials held at Tamiment:

One 16mm print of People’s Congressman—Marcantonio

One 16mm print of A People’s Convention

One 16mm print of The Sentner Story

One 16mm print of The Great Swindle

One 16mm print (and one VHS) of Deadline for Action

Most of the prints have some wear and tears but none are in a bad physical condition.

Erika and I will be happy to facilitate any preservation and access needs relating to these titles. Please let us know if you need any additional information.[17]

Persistence had been rewarded.

Figure 4

Six-page playscript for Abel Meeropol’s The Investigators.

Table A

The Marzanis had loaned me a really bad video copy of A People’s Convention (1948). Even so, it seemed to me a fascinating film. As the 2012 presidential election approached, the 8th Orphan Film Symposium (Museum of the Moving Image, Astoria, April 11-14, 2012) seemed a perfect opportunity to show the campaign film, which provided a documentary record of the 1948 Progressive Party convention that nominated Henry Wallace as its presidential candidate in July 1948. Indeed the US presidential election of 1948 was remarkable from many perspectives, not least of all because the battle of 35mm campaign films in the movie houses had much to do with President Harry Truman’s upset victory over Republican candidate Thomas Dewey (McCullough 1990, pp. 684-85). Third Party candidate Wallace did not have that kind of access and so depended on Carl Marzani, who produced more than a dozen Wallace campaign films, all in 16mm. In this instance, the MediaPreserve (located in Pittsburgh) did the technical work pro bono as an Orphan Film Symposium sponsorship, digitizing two films: The Jungle (1967) and A People’s Convention.[18] Here is my subsequent film note:

A People’s Convention

Produced by Carl Marzani; directed by Max Glandbard; script by Milton Ost and Irving Block; music by Serge Hovey; sung by the American People’s Chorus; narration by Herman Land; soloist: Ernie Lieberman; cinematography by Vic Komow, Jack Gottlieb, Leroy Silvers; sound: Richard Patton [Andy Cusick?]. Released: August 1948. 550 ft. A Presentation of the Progressive Party. A Union Films Production. HD-CAM transfer from a 16mm print in the Carl Marzani Collection, NYU Libraries. Preservation elements courtesy of the Media Preserve. 15 mins.

Carl Marzani and the Union Films collective (Max Glandbard as director, Vic Komow as cameraman and Andy Cusick [perhaps with the nom de guerre of Richard Patton]) made numerous campaign-related films on behalf of Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party, starting with Time to Act (February 1948) and Wallace at York (March 1948). In the wake of its Philadelphia convention in late July 1948, Union Films quickly released four substantial campaign-related documentaries for the Progressive Party: Dollar Patriots, A People’s Convention, Young People’s Convention (aka The Young People Meet) and People’s Congressman (aka The Marcantonio Story).

This fifteen-minute documentary provides an invaluable record of the Progressive Party’s gathering even as it combines “people’s songs” with film in an innovative, almost experimental manner. As with several earlier Union Films productions, there is some effort to render events theatrical. A People’s Convention has a protagonist, Joe, who is attending the convention and is shown in both the introductory and final shot, while making several appearances over the course of the picture. His presence, however, is quickly subsumed by the desire to document the convention, which was all the more urgent given the distortions that were being generated by the news media.

The soundtrack is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of A People’s Convention. It weaves together a song performed by the American People’s Chorus and soloist Ernie Lieberman with narration delivered by Herman Land.[19] Where song ends and narration begins is unclear: this mixture and the piece’s overall style evoke “Ballad for Americans,” which Paul Robeson had made famous. Certainly this soundtrack evokes the spirit of Robeson, who spoke twice and sang at the Progressive Party convention and has a brief on-camera appearance in this documentary as well. The composer Serge Hovey had provided the musical score for another Union Films production, The Investigators, made a few months before.

As many Union Films productions make evident, song played a particularly important role in the Progressive movement. (It is not by chance that both Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger appear in A People’s Convention.) At political rallies, Robeson alternated between singing and political speech—an alternation that is also evident in three other Wallace campaign films.[20] As Robbie Lieberman (1989, p. 132) has noted,

Songs were an integral part of the Wallace campaign. Sound trucks and caravans featured shows and music, and mass singing was part of every function. The Wallace campaign was often compared to a religious revival and singing played a large part in creating such an impression. The Progressive party and the People’s Songs [, Inc.] shared a belief in the power of song.[21]

The short-lived but influential People’s Songs, Inc. (1946-1949), directed by Pete Seeger, backed the Wallace-Taylor ticket. Its members led mass singing at rallies. The Wallace campaign thus used Popular Front song as a weapon for Popular Front politics.[22]

The successive screenings of three Union films at Orphan Film Symposia had led to a broader assessment of Union Films materials in archives. As already noted, two private archives have been particularly important to my work. The MacDonald & Associates film archive had its origins in the early 1970s when Fred MacDonald began gathering films from a variety of sources for his teaching and research in the U.S. history and American popular culture at Northeast Illinois University.[23] Rick Prelinger founded the Prelinger Archives in 1982 to preserve ephemeral films (sponsored documentaries, educational films, amateur and home moves, etc.) and there were 60,000 complete films in its archives by 2001.[24]

Both Rick and Fred ended up transferring their archives to the LOC: Prelinger Archives made a hybrid gift/sale to the LOC that resulted in a series of deposits beginning in 2002, totalling 65,000 cans,[25] while MacDonald sold his collection in 2010 when it “took eleven 53-foot-long trailers to drag all the materials back to Culpeper, Virginia where the Library of Congress has its Preservation Campus.”[26] The LOC was the logical repository because of its commitment to preserving artefacts of American culture rather than “art” and because of its Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation in Culpeper, Virginia with an immense storage capacity, which opened in 2008.[27] These collections greatly enriched the LOC’s previous holdings of Union films.

It has become increasingly important to investigate institutions that chose not to divest themselves of their 16mm film heritage in the era of videotape and DVDs. They have become at the very least de facto archives. Indiana University formalized its archival status in 2011 when it consolidated a number of collections within the Indiana University Libraries Film Archive. According to Rachael Stoeltje, the bulk of its collection consisted of roughly 35,000 educational films which were “part of the distribution and production unit known as the IU Audio Visual Center (from the 1930s-2000s).”[28] Despite such impressive numbers, none of the prints in the IU Audio Visual Center were made by Union Films or sponsored by the UE.[29]

Even though universities often resist taking on film collections, which involves assuming some degree of archival responsibility, this has proved unavoidable. The Marzani collection at the Tamiment is but one example. The United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America (UE) selected Archives of Industrial Society at the University of Pittsburgh as the national repository of its records in 1975. Donations followed with 3,000 boxes of material.[30] In 1984, 1997 and 2004 the University of Pittsburgh Library System received UE film deposits which included 16mm prints (and perhaps some pre-print material) of five important Union Films documentaries made for UE: Deadline for Action (1946), Our Union (1947), The Great Swindle (1948), Industry’s Disinherited (1949) and The Sentner Story (1953). There were also four UE-commissioned travelogues featuring radio personality Arthur Gaeth: Eyewitness in Athens (1949), Rome Divided (1949), Israel is Labor (1949) and Failure in Germany (1949).[31]

Figure 5

Figure 6

A somewhat similar situation has occurred at Yale with its Film Study Center. Officially a study centre established in 1973, it now has over 500 35mm prints and 3,600 16mm prints. It has always had a few archival collections such as a donation from experimental filmmaker Mary Ellen Bute. Increasingly it has taken on archival functions, and the deposit of the Glandbard and Marzani collections is indicative of this. Nor is the Yale Film Study Center an entirely arbitrary repository. Labour history has been one of Yale’s strengths: Amy Heller, president of Milestone Film & Video, wrote a paper on the UE while getting her Master of Arts at Yale (Heller 1985).

The Yale Film Study Center’s continued accumulation of rare film materials has been complemented by the preservation and restoration of a handful of films such as Bute’s Passages from Finnegans Wake (1967) and Glandbard’s copy of Our Union, under the guidance of recently retired manager Ann Horton. Unlike the digital transfers of The Investigators and A People’s Convention, Our Union was preserved along traditional lines: making a 16mm preservation negative and other pre-print material as well as a 16mm print—plus DVDs. As Ann explained,

the NFPF [National Film Preservation Foundation] funded the restoration of Our Union as a donation of services from Colorlab. It was an unusual arrangement for Yale to get their head around as no funds came into Yale, as normally occurs, but Yale ended up with all the benefits—new negative, two new prints, and HD DVD master and screening copies. The print we had to work with was in pretty rough condition but the fine technicians at Colorlab were able to repair the sprocket hole damage and deal with the warpage to create the new master materials.[32]

One important step in transforming the Yale Film Study Center into the Yale Film Study Center & Archive has been the recent hiring of Brian Meacham, who had been working as an archivist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences in Los Angeles.

Showing Union films at successive Orphan Film Symposia has been a way to keep the Union Films Project before the eyes of scholars and archivists while maintaining momentum. The 9th Orphan Film Symposium (EYE Film Institute Netherlands, Amsterdam, March 30-April 2, 2014) focused on the future of obsolescence as a theme, providing the perfect setting for showing Industry’s Disinherited (1949), about the fate of older workers who are forcibly “retired” without sufficient financial protection.

As these activities continue, it has become increasingly urgent to define the Union Films Project. What is it? It would seem to have two parts. The first is the most straightforward: Union Films deserves a monograph—making it one of the (too) many book projects I am eager to complete. As I prepared this article, Eric Glandbard went back into his father’s archive and found various photos, playscripts and other documentation that are relevant to this undertaking.

The Internet also continues to expand in ways that are often useful, revealing unexpected delights. For instance, within the last two years, two animated shorts with musical compositions by Serge Hovey have popped up on the Internet Movie Database (IMDb): Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat (1954) and The Hangman (1964). The latter film was narrated by Hershel Bernardi, which perhaps hints at the ongoing relationships among these artists who suffered from the blacklist. (One small future step is to get Union Films a Wikipedia entry and list its film titles on IMDb.) A large array of other materials will further enrich our understanding and appreciation of Union Films and need to be consulted: everything from newspapers such as The Daily Worker and PM to the rich UE paper collections in the University of Pittsburgh Library System. Moreover, grappling with Union Films requires a broader context—both an account of other leftist filmmaking in this period and its right-wing as well as middle of the road alternatives—all operating during an intense period of political reaction.

The other half of the Union Films Project involves the preservation and dissemination of Union Films motion pictures. Here the debates within the Orphan Film movement are considerable. For The Investigators and A People’s Convention we now have HD-CAM transfers. Do these constitute preservation copies or merely good screening copies? The answer to this question seems unclear. The future of film as a format for preservation is certainly in question. When discussing The Investigators, Dan Streible suggested that film-to-film preservation was basically in the past when it comes to 16mm. As we know, digital processes have been used to repair damage to prints, so these transfers could be part of a first step towards some more far reaching process of restoration. In any case, these instances of high quality digitization have reintroduced Union Films to a larger public and allowed for much wider appreciation, evaluation and judgment. The response that these films generate from scholars in various fields as well as more general audiences will help to determine the future of these films as archival assets—and the possibilities for serious archival preservation and restoration. In this regard the pleasure and excitement expressed by Orphanistas may have enabled many more of these films to become serious candidates for future preservation.

With orphan films such as those produced by Union Films, the relation between preservation and access is highly variable, integrated and finally uncertain. Their vast quantity puts pressure on the process of selection. Moreover, the process of what is to be preserved is refigured by the question of how to preserve them and the role of digitization. Not all films may be preserved equally or in the same way. Caroline Frick (2010, pp. 151-80) may be right that for better or worse, the act of digitizing for access may turn out to be the only act of preservation many films receive. Does HD-CAM constitute preservation? One can only be happy that the acting original (typically a surviving 16mm print) is sitting on a shelf in an appropriate storage facility. Caring archivists and good storage of the 16mm prints are probably the best kind of preservation for the moment.

Figure 7

When it comes to generating access, I am enamoured with the idea of gathering together all available Union Films productions and creating a “definitive” DVD collection. Rick Prelinger, the godfather of the Orphan Film movement, has expressed the strongest reservations to this approach. After all, the Prelinger Archives have achieved unusual visibility through innovative forms of access. Rick began making many of its films available online for downloading at the end of 2000. As he wrote,

I partnered with Internet Archive in 1999 and began working seriously on getting material online in 2000. The online site first went up on December 29, 2000, with about 280 films and grew to 1001 in early 2001. Currently there are 3,800 films online.[33]

Prelinger privileges downloading over streaming because,

Streaming is a means of attempting to maintain control over the exhibition of a film. In most cases I feel this is inappropriate for public domain materials that others might wish to use in instruction, research, or production. If enabling research, scholarship, teaching and public authorship is one’s objective, it is difficult to justify measures of enclosure such as streaming.[34]

And while films from the Prelinger Archives sometimes end up on YouTube, Prelinger Archives does not have its own YouTube channel. Asked why, Rick responded:

Lots of our films have been crossposted to YouTube. That’s fine with me, though I am always happier if they are attributed back to us.

Over the years we’ve been approached three times by YouTube to set up a channel. The problem there is that they want us to assert rights and indemnify them for public domain material, and since a lot of our films have been posted by others we run the risk of being flagged by Content ID and have material taken down when it originally emanates from us. The Internet Archive isn’t as popular an online venue as YT, but the effort-to-reward ratio for YT is slim enough that I just haven’t had time to sort all of this out.

What I plan for the next year or so is to build a kind of meta-site that will function as a master portal to all Prelinger films that have found their way online, with metadata on a static crawlable page and links to instantiations of our material at IA, YT and elsewhere. I’d also like to link to derivative works of special interest, and to webpages or online scholarship that adds context and value to the original films. See, for instance, http://enculturation.gmu.edu/11.

When I estimate the number of downloads and views for our films on IA and YT, I come up with a rough figure that hovers around 70 to 80 million. That’s pretty good for a small online collection whose universe only recently hit 3,800 items. So I think the YT situation is taking care of itself.[35]

Deadline for Action is available on Internet Archive in two sections. As of April 11, 2014, the first and second sections had been downloaded 4,954 and 4,287 times respectively. The Great Swindle, also in two parts, had 6,137 and 2,776 downloads.[36] The lower figures for the second sections would seem to more accurately reflect actual use. That use, of course, is open to analysis. Some downloads might have produced a single viewing but others might have been destined for classroom screenings or other group viewings. To put the quantity of these downloads in perspective is slightly complicated. Another film on the Prelinger site, Automotive Service (1940) has seemingly been downloaded 3,142,136 times. Rick Prelinger has suggested, however, that “the figures for the top 23 download counts are suspect but are substantially accurate from No. 24 (Duck and Cover) down.” That one has had 586,889 downloads. Prelinger also notes “the multiplier between Internet Archive downloads and YouTube views; it varies but for one of our most viral films, the Miles Bros. A Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire, 78,000 hits on Archive.org multiplied to over 4 million on YouTube.”[37]

When it comes to orphan films, the relationships between access, dissemination and preservation can be attenuated. Most of us would be reluctant to argue that the striking discrepancy between the 537,636 downloads of Exercise and Health (1949) and Deadline for Action means the former is approximately 125 times more worthy of preservation or scholarly attention than the latter. Nor does it mean that those downloads constitute preservation as Caroline Frick has sometimes suggested. However, when it comes to the piles of orphan films in private and public collections, it seems impossible to believe that reception and popularity will not be one factor when selecting candidates for high-end preservation. As a Cold War government-sponsored information film, Duck and Cover (1951) is an ideological rival to the kinds of films made earlier by the likes of Union Films. Scholarship can help to bridge the gap between the two. The discrepancy in download numbers does not mean that one should be preserved and not the other. Rather one suspects that the films that never get on the Internet Archive or YouTube are the more likely losers when candidates for preservation are being considered. Even here one must balance the maxim “out of sight, out of mind” with its opposite: “absence makes the heart grow fonder.” The absence of Union films such as The Investigators from YouTube and the Internet Archive has not necessarily been a bad thing.

Rick Prelinger has challenged the last part of the prior sentence, remarking

While I fervently agree that loss and absence is formative in that it encourages research to fill perceived gaps, I think it is essential to make films of this sort available online to all. I strongly think it would be great to make downloadable digitized copies of these films available to all.

Before 2000 there was almost no scholarship focused on what I call ephemeral films. What little there was [was] typically the work of political historians, gender studies researchers, communications researchers and ethnographers. After we made material available for open access the number of papers and books spiked, and though of course many did not focus on works in our collection, we believe that an open online corpus had a dramatic effect in increasing the amount of work in the area. I think it certainly encouraged work in the Orphans space.[38]

While it seems inevitable that most Union Films pictures will end up on the Internet and in downloadable form, the question for me remains how to get from where we are now to that point. Thinking about this problem and being pressured by open access advocates is helpful, even though my own biases still tend toward a coordinated, curated and more cautious approach. This is also to suggest that not all orphan films are the same. The reasons why they became orphan films can be quite different. Besides the politics of preservation and access, we need to keep in mind the politics and history of political struggle. There are reasons why Flaherty’s The Louisiana Story (1948) is not considered to be an ephemeral film, in contrast to Union Films’ The Great Swindle (1948). One of my goals is, in fact, to trouble that distinction. A DVD set of Union Films productions would be one way to do that.

Scholarship of a certain kind (the kind of scholarship I seem to do) is constantly working hand in hand with the archives to preserve, restore and sometimes reconstruct. The status of the film prints with which one is working is always crucial. Scholarship inspires preservation, but also access. Access can inspire preservation as well as more scholarship.[39]

The Union Films Project was not one I intentionally sought out. I was, indeed, lured by the archive—in this case by an obscure film in the Museum of Modern Art’s archival film collection. Trying to situate that film—People’s Congressman—in a larger history sent me to other archives: some such as the UCLA Film & Television Archive were well established while others, such as Fred MacDonald Associates, were more ad hoc. The more research I did and the more archives I encountered, the more concrete and alluring became the Union Films Project. Initially I could tell myself that investigating Union Films was a way to investigate the hidden history of Paul Robeson’s post-World War II film career. It was really still part of my Robeson project. Paul Robeson may appear in many Union films but he does not appear in a single Union film in the Marzani or Glandbard collections at Yale. The joys and frustrations that come from making use of archives is perhaps only exceeded by the satisfactions and occasional disappointments that come from rescuing “lost films” and getting them into archives where they are better protected and used. The archives have always been a constant distraction. Since my publication of three books on early cinema (Musser 1990, 1991 and 1991a), my record of scholarship has been littered with essays that gesture towards unfinished book projects. I have been lured further and further afield: from a passion for film comedy to a fascination with cinema and theatrical culture, from cinema and theatrical culture to Oscar Micheaux, from Micheaux to Paul Robeson, from Robeson to Union Films and even now enticed into the world of campaign films—not just in 1948 but the use of audio-visual material for campaign purposes in the 1890s and in the contemporary moment. The reasons for that are doubtless complex, but the persistently mesmerizing and distracting lure of the archives must take at least some of the blame.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Charles Musser est professeur au Film and Media Studies Department de Yale University, dont il a dirigé le programme d’études théâtrales. Ses recherches actuelles portent notamment sur l’historiographie du cinéma hollywoodien préclassique. Il s’intéresse également à l’histoire et à la théorie du cinéma documentaire et a récemment collaboré au Documentary Film Book (publié en 2013 par le British Film Institute sous la direction de Brian Winston). Il a réalisé, avec Carina Rosanna Tautu, le documentaire Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch (2014).

Notes

-

[1]

Many thanks to Dan Streible, Rick Prelinger and Christa Blümlinger for their comments and feedback. Special thanks to Charlotte Marzani, Tony Marzani, Eric Glandbard, Michael Kerbel, Ann Horton, Nick Forster, Mike Mashon and Threese Serana. Likewise, although Oscar Micheaux made over twenty silent films, the only one to survive in American archives was Body and Soul (1925), starring Paul Robeson. Robeson’s presence was key to ensuring its survival.

-

[2]

Dan Streible, e-mail correspondence, 31 January 2008.

-

[3]

Dan Streible, e-mail correspondence, 12 February 2008. I had shown Robeson’s first documentary, My Song Goes Forth (1937) at Orphans 2.

-

[4]

“Orphanista” is the term used to describe those who are part of the Orphan Film movement and attend the symposia organized by Dan Streible.

-

[5]

Charles Musser, e-mail correspondence, 14 August 2008.

-

[6]

Eric Glandbard, e-mail correspondence, 17 August 2008.

-

[7]

Eric Glandbard, e-mail correspondence, 29 August 2008.

-

[8]

While Deadline for Action was on the Internet Archive, there was (and is) no indication that Union Films produced it. It has been listed as produced and sponsored by the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America.

-

[9]

Rick Prelinger, e-mail correspondence, 12 May 2013.

-

[10]

Eric Glandbard, e-mail correspondence, 10 July 2009.

-

[11]

For instance, Lichtenstein (2005) had avoided discussion of Our Union because its relation to Union Films was unclear.

-

[12]

The fourth title turned out to be The Great Swindle (1948).

-

[13]

Ivy Meeropol, e-mail correspondence, 26 March 2010.

-

[14]

Lewis Allan, The Investigators in “Stage For Action,” Series XCIX, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library.

-

[15]

An uncondensed version of the film note appears on http://www.charlesmusser.com/?page_id=1658.

-

[16]

Guide to the Carl Aldo Marzani Papers TAM.154, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives, http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_154/tam_154.html.

-

[17]

Alice Moscoso, e-mail correspondence, 23 September 2010.

-

[18]

Dan Streible, e-mail correspondence, 31 May 2013.

-

[19]

The cover of Sing Out! (July 1951) uses a picture of Robeson singing with the People’s Artists Quartet, one of whom is Ernie Lieberman. See his daughter’s book (Lieberman 1989, p. 145).

-

[20]

For instances where Robeson combined song and speech at a Wallace rally in which he was the principal political figure, see “Robeson Flays ‘Truman Crowd’ at Local Rally,” Chester Times [Pennsylvania], September 21, 1948; “Robeson Still Possesses Fine Singing Voice, But Propaganda About Reds Flavors His Speech,” Nevada State Journal, October 14, 1948; advertisement, Cleveland Call and Post, February 1, 1948, 7B (the ad was for a Henry Wallace for President event in Cleveland on February 8).

-

[21]

Lieberman’s book provides a history of People’s Songs, Inc. Founders Pete Seeger, Earl Robinson, Woody Guthrie, Josh White, Bess Hawes and others created the organization to disseminate folk music and spur progressive political action. Robeson was a member of its board.

-

[22]

For a brief history of the Popular Front in the United States, see Denning (1996, pp. 22-25). The “cultural front” in the post-war era would seem to be more productive and richer than Denning suggests. Like the writings of William Alexander and Russell Campbell in cinema studies, Denning focuses on the 1930s. My film note for A People’s Convention was written and subsequently condensed for inclusion in the notes for the DVD Orphans 8: Made to Persuade (2012). An uncondensed version of the film note appears on http://www.charlesmusser.com/?page_id=1672.

-

[23]

“J. Fred MacDonald and Associates,” Michael Feinstein’s American Songbook, http://www.michaelfeinsteinsamericansongbook.org/collection.html?c=6.

-

[24]

See also Russell (2013) and Martel (2013).

-

[25]

Rick Prelinger explains: “The collection was appraised at $2.5 million. It was a hybrid gift/sale. We donated 80% of it, and LC bought 20% of it for $500,000, paid over 3 years. Since it was a gift from Prelinger Associates, Inc., and the company didn’t have any profit to shelter, we took no charitable deduction” (e-mail correspondence, 4 June 2013). See also the video This is the Prelinger Archives (2001), http://www.prelinger.com.

-

[26]

Fred MacDonald, e-mail correspondence, 20 May 2013.

-

[27]

“Campus Features,” http://www.loc.gov/avconservation/packard/.

-

[28]

Rachael Kennedy Stoeltje, e-mail correspondence, 23 May 2013.

-

[29]

That a collection of this size did not circulate any Union Films productions is one symptom of the company’s blacklisting.

-

[30]

“Finding Aid,” United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America Records, ULS Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

-

[31]

“UE Film Inventory,” United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America Records, ULS Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

-

[32]

Ann Horton, e-mail correspondence, 21 May 2013.

-

[33]

Rick Prelinger, e-mail correspondence, 12 May 2013. See also Prelinger (2007).

-

[34]

Rick Prelinger, e-mail correspondence, 5 June 2013. By the time of this e-mail, Prelinger Archives had 4,200 films online with more on their way.

-

[35]

Rick Prelinger, e-mail correspondence, 22 May 2013.

-

[36]

In a newer upload (with 845 hits) both sections of The Great Swindle have been combined.

-

[37]

Rick Prelinger, e-mail correspondence, 5 June 2013. Since there were seemingly dozens of posts of A Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire (1906), some of which are excerpts and others remixes, calculations are difficult even though the scale is obviously impressive.

-

[38]

Rick Prelinger, e-mail correspondence, 5 June 2013.

-

[39]

I can offer many personal examples of the dynamic involving scholarship, preservation and access but one of my favourites involves Robeson’s first documentary foray, My Song Goes Forth (1937). It was missing the fourth of five reels when we showed it at Robeson film retrospectives. Only one print was available for viewing—at the British Film Institute. I ordered a second 35mm print for the Yale Film Study Center (rather than a less expensive digital copy). In the process of preparation, the archive discovered that the missing reel had just never been preserved. Thus not only was the preservation work completed but we ended up with a complete print that premiered at the Margaret Mead Film Festival in New York.

Bibliography

- Allan 1946: Lewis Allan, “The Investigators,” The New Masses, 9 July 1946, pp. 11-13.

- Allan 1946a: Lewis Allan, “I Saw a Man,” The New Masses, 20 August 1946, p. 8.

- Allan 1946b: Lewis Allan, “War,” The New Masses, 3 September 1946, p. 15.

- Baker 2002: Nancy Kovaleff Baker, “Abel Meeropol (aka Lewis Allan): Political Commentator and Social Conscience,” American Music, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2002, pp. 25-79.

- Crowdus and Rubenstein 1976: Gary Crowdus and Lenny Rubenstein, “Union Films: An Interview with Carl Marzani,” Cineaste, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1976, p. 33.

- Denning 1996: Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century, New York, Verso, 1996, 556 p.

- Frick 2010: Caroline Frick, Saving Cinema: The Politics of Preservation, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010, 215 p.

- Heller 1985: Amy Heller, “The Perennial Nightmare: Anti-communist Agitation and Conflict Inside and Outside United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) Local 203, Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1944-1950,” 1985. Unpublished paper courtesy of Amy Heller.

- Horak 2006: Jan-Christopher Horak, “Editors Foreword,” The Moving Image, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2006, p. vii.

- Horne 1988: Gerald Horne, Communist Front?: The Civil Rights Congress, 1946-1956, Rutherford, Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1988, 454 p.

- Lichtenstein 2005: Nelson Lichtenstein, “Deadline for Action; Our Union; The Great Swindle,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2005, pp. 140-43.

- Lieberman 1989: Robbie Lieberman, “My Song Is My Weapon”: People’s Songs, American Communism, and the Politics of Culture, 1930-1950, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1989, 201 p.

- Martel 2013: Caroline Martel, “Looking Back at an Electronic Exchange with a Media Archeologist. An Interview with Rick Prelinger by Caroline Martel 12 1⁄2 Years Later,” in André Habib and Michel Marie (eds.), L’avenir de la mémoire. Patrimoine, restauration et réemploi cinématographiques, Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2013, pp. 101-124.

- Marzani 1992-1995: Carl Marzani, The Education of a Reluctant Radical, 4 vols., New York, Topical Books, 1992-1995.

- Marzani 2002: Carl Marzani, The Education of a Reluctant Radical, Vol. 5, Reconstruction, New York, Monthly Review Press, 2002, 292 p.

- McCullough 1992: David McCullough, Truman, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1992, 1117 p.

- Musser 1990: Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907, New York, Scribner’s Sons, 1990, 613 p.

- Musser 1991: Charles Musser, Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1991, 591 p.

- Musser 1991a: Charles Musser, in collaboration with Carol Nelson, High-Class Moving Pictures: Lyman H. Howe and the Forgotten Era of Traveling Exhibition, 1880-1920, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1991, 372 p.

- Musser 2009: Charles Musser, “Carl Marzani & Union Films: Making Left-wing Documentaries During the Cold War, 1946-53,” The Moving Image, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2009, pp. 104-160.

- Nerone 2006: John Nerone, “The Future of Communication History,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 23, No. 3, 2006, pp. 254-262.

- Prelinger 2006: Rick Prelinger, The Field Guide to Sponsored Films, San Francisco, National Film Preservation Foundation, 2006, entries 110, 174 and 204.

- Prelinger 2007: Rick Prelinger, “Archives and Access in the 21st Century,” Cinema Journal, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2007, pp. 114-118.

- Russell 2013: Catherine Russell, “Benjamin, Prelinger and the Moving Image Archive,” in André Habib and Michel Marie (eds.), L’avenir de la mémoire. Patrimoine, restauration et réemploi cinématographiques, Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2013, pp. 101-124.

- Streible 2009: Dan Streible, “The State of Orphan Films,” The Moving Image, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2009, pp. vi-xix.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

Figure 3c

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Liste des tableaux

Table A