Corps de l’article

How are intimate and elusive experiences such as sexuality and emotions documented and archived? This question has been taken up empirically and theoretically by a number of influential queer, feminist, and critical race scholars who have expanded our understanding of what might be considered records of the past.[1] The recent exhibit Theatres of the Intimate, showcasing work by Canadian photographer Evergon, at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ), offers a good example of the powerful way the arts, and in this case photography, contribute to documenting and archiving affective and ephemeral experiences.

Evergon: Theatres of the Intimate is the first retrospective exhibit dedicated to the Montréal-based Canadian photographer Evergon. Commissioned by Bernard Lamarche, head of collection development and curator of contemporary art, the exhibit includes more than 230 works that span 50 years of the artist’s career. As art historian Eduardo Ralickas writes, Evergon is an “accomplished and prolific photographer” whose “oeuvre has contributed to the forging of a post- Stonewall imaginary in Québec.”[2] With this exhibit, the MNBAQ thus contributes to writing queer aesthetics and photography in the Québec artistic canon and expands collective understandings of political art in the province.[3]

As suggested by the exhibit’s title, there is a tension in Evergon’s photographic archiving of intimacy between the documentation of private everyday experiences and their theatrical production and mise en scènes. Inspired by Ralickas, who argues that “Evergon has developed a highly personal queer mythology driven (i.e., produced and sustained simultaneously) by the power of the photographic image,”[4] I focus in this review on the ways in which the exhibit Theatres of the Intimate shows photography as both a powerful artistic medium to capture and document reality as well as a medium to reinvent, create, and transcend it.

One of the main successes of Theatres of the Intimate is its demonstration of photography as an artistic medium of both evidence[5] and other-world-building. On the one hand, the exhibit demonstrates the ways in which photography contributes to political visibility by providing material evidence of communities, practices, and landscapes; on the other hand, it also shows how photography can be used to create archives of imagined and mythical worlds that open up opportunities for self-expression. As such, Theatres of the Intimate constructs an archive of intimacy that is both real and imagined, where photography is used as a documentary archive of queer identity and sexuality as well as a creative archive of imagined intimacies and communities.

The exhibit opens with an invitation to blur the boundary between intimate and public, which pulls the visitor into Evergon’s universe. With its multiple subsequent small rooms, connected by archways with a minimal number of artworks, the physical setting of Theatres of the Intimate effectively brings visitors close to Evergon’s oeuvre. The curators have successfully used the contrast between saturated deep-blue and gallery-white walls to provide the impression, at times, of low ceilings and a feeling of proximity with the work, and at other times, of a spacious room for larger photographic frames.

The first display is unremarkable and does an adequate job of contextualizing the work by didactically introducing key themes of Evergon’s oeuvre: the political character of his work; his fascination with fantastic and mythical worlds; and his technical playfulness with mediums, styles, and genres. It is however the subsequent display, the Ramboy invitation, that truly pulls us into the poignant intimate journey we are about to begin with the artist.

Past a set of glass doors, visitors enter a woodsy cruising ground, invited in by a member of Evergon’s mythical community of Ramboys, described in the exhibit text as “a cast of half-man, half-ram characters whose liberated, masculine promiscuity is revealed in their customs and rituals.” In this large-scale picture, a Ramboy with a penetrating look presents us with a Polaroid of the forest, the calling card for the exhibit (see figure 1). This mise en abyme stands alone, atop a wall saturated in navy blue, a colour visitors will encounter again as it ties together the multiple small rooms of the exhibit.

FIGURE 1

Evergon, Ramboy Offering Polaroid of Self Exposed in Hiding, from the series The Ramboys: A Bookless Novel. Evergon, Théâtres de l’intime 2022, exhibition view.

The rest of the exhibit is organized along two axes that organize Evergon’s work by themes and techniques rather than chronologically. First, the Making of the Image axis takes us through Evergon’s skilful and inventive multidisciplinary work – from holograms to giant polaroids and back in time to the early collages at the beginning of his career in the 1970s – thus revealing the genesis of his multilayered approach to photography. Second, the beautifully named Intimacy Inventory axis demonstrates Evergon’s poignant documentation of love, sex, and desire.

The organization of the exhibit as an unfolding accordion, along two axes, rather than a traditional chronological presentation, is both a strength and limitation. The first axis effectively introduces the artist by dovetailing his gender-bending self-portraits, multiple techniques, and signatures under the theme Making of the Image. This powerfully introduces visitors to Evergon as a uniquely multidisciplinary artist who deconstructs genders and genres – be they social, artistic, or technical. However, the other axis, in the second half of the exhibit, becomes hard to follow. There is little articulation of Evergon’s exploration of death, mourning, and depression as expressions of intimacy and vulnerability – something uniquely captured by the artist’s evocative photographs – and this weakens the Intimacy Inventory thread that connects the rooms halfway through the exhibit. We are, however, pulled back in by a more coherent flow between the rooms dedicated to Evergon’s mythical community in The Ramboys: A Bookless Novel, gay cruising grounds in the series Manscapes, and sex and desire in Active Bodies, which together show the myriad ways Evergon skilfully and evocatively captures sexuality and intimacy between men.

The exhibit shows Evergon’s skilful use of photography’s paradoxical ability to act as both evidentiary record that renders visible marginalized sexualities and identities and artistic document of imagined ways of being, desiring, and living in community. As such, Evergon’s multidisciplinary approach, which blends performance, collage, and photography, documents reality as much as it creates it, thus contributing to queer other-world-building by producing records of dreamed and imagined intimacies. The exhibit displays this paradoxical use of photography as evidentiary and imaginary by showing how Evergon’s art both documents and creates the self, records and fantasizes sexuality, and collects and transcends the everyday.

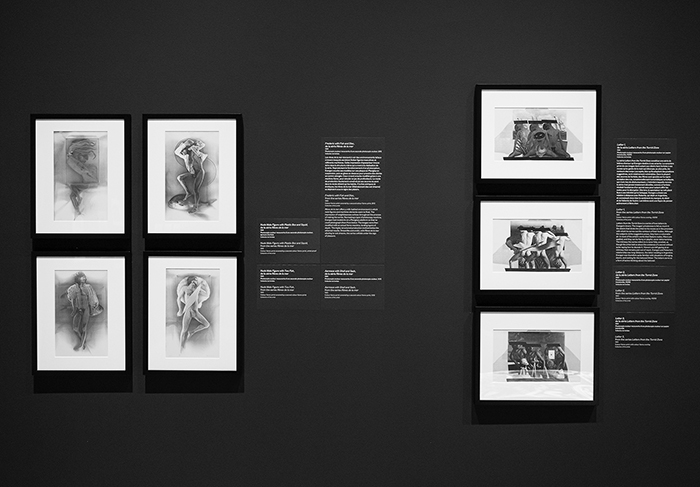

FIGURE 2

Evergon, Crossing the Equator Going South Pacific Rim, no 1, 2009. Digital print from a 4 × 5 colour negative, 127 × 101.6 cm. Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. Gift of the artist (2023.167).

Evergon’s gender-bending self-portraits powerfully show the artist’s use of photography for self-expression, both documenting and creating the self (see figure 2). The self-portraits are usually signed “Evergon,” the first pseudonym of the artist, who chose the name in the 1970s as an “emancipatory deletion of the family name and a refusal of a gendered name.”[6] But the artist also signs some of his pieces under other names derived from Evergon.

The multiple signatures grant Evergon the possibility of breaking with a single style, genre, and gender, “signalling, as the exhibit text highlights, a renewed desire to shake off the familiar.”[7] Under Celluloso Evergonni, the artist “offer[s] theatricality and chiaroscuro”; under Eve R. Gonzales, an elderly woman, the artist embraces a “softer, sensual, and sometimes provocative” style; and finally, under the name Egon Brut, the artist offers black-and-white photographs with a direct, “almost documentary effect.”[8] Evergon is also part of a duo, called Chromogenic Curmudgeons, with “long-time collaborator and sometimes model Jean-Jacques Ringuette, a Québec artist,”[9] who offers a powerful and vulnerable take on aging and the fear of death.

As the exhibit title Theatres of the Intimate suggests, Evergon’s artistic practice documents intimacy by turning an outward gaze onto sexuality in the public sphere as well as an inward gaze onto desire between partners in the private sphere. This twofold approach is enhanced by the artist’s use of photography to both expose and fantasize sexuality between men.

In his series Manscapes, Evergon shows how public spaces and seemingly empty landscapes are synonymous with intimacy. Documenting sites from parks to trucks stops and coastal scenes, Evergon queers the traditional photographic instinct to capture scenery, using it instead to call attention to sexual practices that have been forced into invisibility. By capturing cruising grounds for forbidden and marginalized sexualities – in particular, gay sexuality – Evergon also challenges heteronormative definitions of intimacy as unfolding behind closed doors (see figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Evergon, Road to Vulcan, de la série Manscapes: Truck Stops, Lovers Lanes and Cruising Grounds par Egon Brut, 1995. Selenium-toned gelatin silver print from an instant print negative (Polaroid), 3rd edition, 1/5, 76.2 × 101.6 cm. Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. Gift of the artist (2022.97.02).

Evergon’s photographic exploration of intimacy not only makes visible marginalized sexualities but also creates imaginative expressions of desire. The artist does so by using a collage-inspired approach to photography and borrowing thematically from the natural world. For instance, in the series Rêves de la mer (1980), nude men coexist with ocean life in an exalted wet dream (see figure 4). The layers create an intriguing veil-like texture, where fantasy and reality meet. Evergon initially intended the photographs as love letters. They embody what the exhibit text calls a “dreamy intimacy” away from the public eye, in closed envelopes sent between partners.

FIGURE 4

Evergon, Rêves de la mer series. Evergon, Théâtres de l’intime, 2022, exhibition view.

A final way in which the tension between evidentiary and imaginative photography is exhibited in Theatres of the Intimate is through Evergon’s documentation of everyday objects as a means to encapsulate elusive experiences of fear, vulnerability, and decline. These ordinary objects – their unruly accumulation for the Chromogenic Curmudgeons,[10] their painful solitude in Cynicism/Chez moi, and their queer resilience in Winter Garden – show how Evergon’s photography documents both the artists’ fears and vulnerabilities and his attempt to transcend them.

The paradoxes evoked in the exhibit rooms dedicated to Evergon’s documentation of everyday life – that is, pieces where objects are both overwhelmingly accumulated and alarmingly absent, or both withering away and renewing hope – offer a nod to the contradiction in the artist’s own chosen name, Evergon.

In sum, the exhibit is of particular interest for those interested in archives and records of the past as it offers avenues for reflection about how to document experiences that tend to leave partially hidden and ephemeral traces. This is particularly important for marginalized intimacies since, as Cvetkovitch writes, “Forged around sexuality and intimacy, and hence forms of privacy and invisibility that are both chosen and enforced, gay and lesbian cultures often leave ephemeral and unusual traces.”[11] As such, Evergon’s photographic documentation of intimacy is at once an aesthetic contribution and a historical one, written in Québec’s own art history by the MNBAQ.

The exhibit also urges us to reflect on the value of imagined and created records of intimacy. Evergon’s multidisciplinary approach to photography indeed constructs an archive of sexuality, desire, and community that is both real and imagined, using photography’s evidentiary power to bring the visitor into mythical worlds. Theatres of the Intimate thus invites scholars of archives and history to consider the power of the arts not only to palliate the limitations of archival absences, either chosen or enforced, but also to transcend them and provide records of felt experiences through imagined sceneries.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

See, for example, Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003); Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019); Marcel Barriault and Rebecka Sheffield, “Note from the Guest Editors,” in “Special Section on Queer Archives,” Special issue, Archivaria 68 (Fall 2009).

-

[2]

Eduardo Ralickas, Evergon: A Photography of Impropriety (Montréal: Dazibao, 2011), 9.

-

[3]

Discussions of political art in Québec often focus on mid-20th-century abstract art and their break with the religious and conservative Duplessis regime. This echoes the words of Nicholas Mavrikakis, who, in a commentary piece for Le Devoir, rightfully reminds us of Québec art history’s oversight of the vast creation between the 1970s and 1990s: “Nous avons tellement célébré Refus global et l’art abstrait des années 1940–1970 que nous en avons oublié qu’il y avait d’autres époques.” “‘Evergon. Théâtres de l’intime’: de l’acceptation de l’imaginaire gai,” Le Devoir, October 27, 2022, https://www.ledevoir.com/culture/arts-visuels/767827/critique-arts-visuels-evergon-theatres-de-l-intime-de-l-acceptation-de-l-imaginaire-gai.

-

[4]

Ralickas, Evergon, 9.

-

[5]

On the evidentiary character of photography and an exploration of Evergon’s series Manscapes as evidence of forbidden desires and sexuality in legal studies, see Derek Dalton, “Arresting Images/Fugitive Testimony: The Resistant Photography of Evergon,” Studies in Law, Politics, and Society 34 (2004): special issue, An Aesthetics of Law and Culture: Texts, Images, Screens, ed. Andrew T. Kenyon and Peter Rush.

-

[6]

Excerpted from the exhibit text in the room titled Making the Image: Signatures.

-

[7]

Ibid.

-

[8]

Ibid.

-

[9]

Ibid.

-

[10]

Evergon’s work with Ringuette, in the series Two Old Friends Play Chess, features photographs of messy collections of objects accumulated in the fear of emptiness and death. See Chromogenic Curmudgeons, “Two Old Friends Play Chess,” accessed August 9, 2023, https://evergonringuette.com/2of. This series constitutes a memento mori, which the exhibit text notes is from the “medieval Latin phrase meaning ‘remember you are mortal.’” It goes on to note that “the duo’s accumulations of objects are loud” and result in overwhelming, psychedelic photographs. Excerpted from the exhibit text in the room titled Inventory of Intimacy/Chromogenic Curmudgeons.

-

[11]

Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 8.

Liste des figures

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 3

Evergon, Road to Vulcan, de la série Manscapes: Truck Stops, Lovers Lanes and Cruising Grounds par Egon Brut, 1995. Selenium-toned gelatin silver print from an instant print negative (Polaroid), 3rd edition, 1/5, 76.2 × 101.6 cm. Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. Gift of the artist (2022.97.02).

FIGURE 4