Résumés

Abstract

This article examines the concept of co-created and person-centred recordkeeping and the needs for this in out-of-home child-care contexts, drawing out a recordkeeping framework. The article uses the research of the UK MIRRA (Memory – Identity – Rights in Records – Access) project as its critical evidence base. MIRRA is a participatory research project, hosted at the Department of Information Studies at University College London (UCL) since 2017, which places Care Leavers as co-researchers at the heart of the work. The study has gathered evidence from care-experienced people, social workers, archivists, records managers, and researchers. The case context of care-experienced people provides a powerful focus for shifting views of records creation and ownership. Care-experienced people across the globe are situated within organizational systems that act as surrogate parents, but where the children or young people are often powerless to co-create and store their own memories, which would enable them to forge positive identities and revisit these through time. Positive and holistic life story narratives are rarely found. In addition, children’s care records are often accessible to care-experienced people only through legislative processes and without critical support. This research reframes the recordkeeping model, placing the care-experienced person at the heart of the process in order to ensure the co-creation of records and the maintenance of identity through time. The research acknowledges the complex and sometimes conflicting needs of diverse actors in children’s recordkeeping, including social workers, archivists, records managers, and researchers. It rethinks the actors’ relationships and responsibilities around the records and systems, drawing out a framework that makes explicit the value of active person-centred recordkeeping.

Résumé

Cet article, en élaborant un cadre d’archivage, examine le concept de co-création et de préservation d’archives basée sur les personnes. Il souligne la nécessité de ce concept dans le contexte de la garde d’enfants hors domicile. L’article utilise la recherche du projet UK MIRRA (Mémoire – Identité – Droits aux documents – Accès) comme fondement critique d’analyse. MIRRA est un projet de recherche participatif chapeauté depuis 2017 par le Department of Information Studies at University College London (UCL). Ce projet positionne ceux et celles ayant quitté les institutions de « soins » comme étant des co-chercheurs.euses se trouvant au coeur de la recherche. L’étude a recueilli des preuves provenant de personnes qui ont été présentes dans ces institutions, de travailleurs.euses sociaux.ales, d’archivistes, de gestionnaires de documents et de chercheurs.euses. Le contexte de l’étude de cas de personnes évoluant dans les milieux de soins offre une démonstration éloquente des changements de perspectives face à la création et la possession des documents. Les personnes ayant vécu dans les milieux de soins à travers la planète sont positionnées à l’intérieur de systèmes organisationnels qui agissent comme parents de substitution. Toutefois, les enfants et les jeunes se trouvent souvent impuissants pour façonner leurs propres récits et mémoires. Cette dimension leur permettrait de se construire des identités et de les revisiter à travers le temps. Des histoires de vie positives et holistiques sont largement absentes. De plus, les dossiers des enfants se trouvant dans les institutions de soins sont souvent accessibles à celles et ceux-ci seulement qu’à travers des procédés légaux et sans soutien critique. Cette recherche recadre le modèle de gestion des archives en positionnant la personne présente dans les milieux de soins au coeur des procédés afin d’assurer la co-création des documents et le maintien de leur identité à travers le temps. La recherche reconnaît les besoins complexes et parfois conflictuels des divers acteurs.trices impliqué.e.s dans la gestion des documents des enfants, entre autres les travailleurs.euses sociaux.ales, les archivistes, les gestionnaires de documents et les chercheurs.euses. Elle repense alors les relations et les responsabilités des différents acteurs.trices concernant les documents et les systèmes, en développant un cadre qui rend explicite la valeur active des personnes impliquées dans la portée des archives.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Historically, recordkeeping models have been driven by those in power, who have been creators, keepers, and voices of authority within the records and recordkeeping systems. However, the need to rebalance recordkeeping, to capture the voices of the marginalized, and to equalize power structures is increasingly being recognized through reframing approaches to provide for participation by all those with vested interests in records creation, management, preservation, and accessibility.[1] A complex discourse has arisen over the last 20 years, with differing approaches to the provision of participatory frameworks from community archives[2] through to other forms of decentralization.[3] Person-centred recordkeeping represents another shift in terms of approaches to equalizing recordkeeping power structures.

Person-centred approaches potentially provide a new lens through which the needs of all actors in the recordkeeping space, especially those marginalized by existing power structures, can be better recognized. While taking into account the needs and values of all parties, this reframes practices to centre those who are most affected by recordkeeping decisions. In addition, it seeks to support each individual. For example, it recognizes the emotional labour and trauma of care-experienced people, social care workers, archivists, and records managers.[4] MIRRA (Memory – Identity – Rights in Records – Access) research suggests that the recordkeeping needs of care-experienced people provide a powerful focus for shifting viewpoints through person-centred perspectives. This article draws on the work of MIRRA to develop a person-centred recordkeeping framework that includes underpinning principles for recordkeeping in out-of-home child-care contexts.

Person-Centred Frameworks in Social Care and Health Contexts

Over the last two decades, person-centred frameworks have been developed in social and health-care contexts.[5] This approach shifts the relationships between the person needing care and others involved in providing care to an equal partner- ship. The person needing treatment or care and those in their lives, that is, other family members, are acknowledged to be experts in terms of that person’s and family’s needs. The partners work together to plan, develop, and monitor the health and care provision to reflect the individual’s needs. As Health Innovation Network in London explains,

This means putting people and their families at the centre of decisions and seeing them as experts, working alongside professionals to get the best outcome. . . . considering people’s desires, values, family situations, social circumstances and lifestyles; seeing the person as an individual, and working together to develop appropriate solutions. Being compassionate, thinking about things from the person’s point of view and being respectful are all important.[6]

Recordkeeping can be an important part of the development of person-centred care. Records are created as part of the discussions with the family and assist with building an equitable relationship and care plan. The record still tracks the person’s health and care, taking into account legal requirements, but it is co-created through discussion, counteracting some of the inequalities that can otherwise emerge.[7] Broderick and Coffey found, in the case of nursing practice, that traditional recording rarely captured the psychosocial care needs of patients. Records were often not created as part of the process but added later. With a person-centred and inclusive approach, the records captured a more holistic sense of need and a fuller, more accurate set of records.[8] New forms of recordkeeping have been imagined by Choi, Gitelman, and Asch, who have suggested that health-care patients co-create the records by providing their own news feeds to integrate with their “official” records.[9] Adopting a person- centred approach has the potential to link social and health-care practitioners with social workers.[10] The potential to extend the approach to child-care settings has, as yet, had limited discussion.

Children’s Care Contexts

Children in out-of-home care are situated within establishment systems that act as surrogate parents. They are some of the most vulnerable people in society. Children may have relationships with many adults with differing roles through time but no one with whom to discuss events and memories. Unlike in family relationships, the children are often powerless to co-create and store their own memories and lack sources that allow them to forge their own positive identities and revisit these through time.[11] The corporate emphasis on recordkeeping has been to track legal liabilities but lacks a framework for the memory and identity needs of care-experienced people.[12]

The MIRRA Research Project

The MIRRA project, funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), explored the recordkeeping surrounding children in out-of-home care contexts in England. In 2017, at the start of the research, there were approximately 75,000 children in out-of-home care in England and Wales.[13] By 2021, the number in England alone had risen to 80,850.[14] Between 2017 and 2019, MIRRA collected data about child social care recording through interviews, focus groups, and workshops with more than 80 Care Leavers, social care practitioners, information managers, and academics. The research was designed in collaboration with a group of six care-experienced co-researchers.[15] A follow-on study in 2020–21, MIRRA+, worked with the Care Leaver co-researchers, teenagers in care, and a social care information technology (IT) systems provider to develop a prototype recordkeeping app enabling children to have a private recordkeeping space.[16]

The article draws on the MIRRA data to develop a person-centred recordkeeping framework that focuses on the rights and needs of care-experienced people at every stage of their lives. The framework seeks to take account of all the actors involved in child social care recording and of their needs and connections. MIRRA research focused on England and its regulatory and legal systems, and while the framework reflects that focus, it will be applicable to other jurisdictions with appropriate revision. A person-centred approach responds to the specific needs and circumstances of individuals, valuing the small alterations that can improve a system for each actor.

Critical Supporting Actors

The MIRRA research identified a number of critical supporting actors with roles to play in records creation, access, and use through time. Within a person-centred context, it is important to see the primary objective of these roles as supporting care-experienced people. The term care-experienced people refers to children and young people in care contexts and adults who are Care Leavers.

While supporting actors will have responsibilities within an employment context, the records they generate are produced to ensure delivery of fundamental care. It is important to ensure that this, as opposed to a misguided loyalty to protect organizations, is the primary motivation of actors. This will assist in removing conflicts of interest. In addition, it is important to recognize that records created about children not only have consequences for those children’s well-being during their time in care but remain critical throughout their lives. They provide access to information about childhood experiences and support the construction of autobiographical memory and sense of self. Recordkeeping needs will alter with life stages and will also be different for each individual. Table 1 lists some of the critical supporting actors and notes their responsibilities and the values of the records they generate. Those involved in the creation and management of care records should contribute to the redesign of practices, taking their lead from care-experienced people.

table 1

Critical supporting actors

In addition to these core supporting actors, others who create essential records and engage with care records include foster carers, residential workers, young offender institutes, legal and law enforcement officers, teachers, doctors, health workers, and others who have contact with children during their time in care.

Problems with Current Recordkeeping

The MIRRA research found that each actor currently looks at the process of records creation from their own (or their employer’s) viewpoint, and in terms of these legal responsibilities, without necessarily centring the needs of the care-experienced person. Few considered other perspectives or understood the value of connected responsibilities to improving care outcomes. In 2020, the British Association of Social Workers reported that social workers spent as much as 80 percent of their time on recording tasks and only 20 percent on family interactions.[17] However, recording was seen as a bureaucratic burden rather than part of the active process of social work. In addition, recordkeeping responsibilities were seen as finite. In England, the corporate parent has not fully assumed the roles and responsibilities of a parent, and by law, a Care Leaver is considered independent at the age of 25 years and the care provider has few further responsibilities toward them.

Care-experienced participants in the MIRRA project often felt that their experiences should not be described as “care.”[18] Care Leavers had not felt involved in the creation of their own care records. They objected to the term official record and to being identified as “subjects” when requesting access to records. MIRRA found that gaining access to records was a bureaucratic process resulting in heavy redaction and a lack of support and aftercare, which left many Care Leavers confused, frustrated, and traumatized. Instead, they wanted to be consulted and involved in recordkeeping and to understand and participate in all discussions about recordkeeping. They wanted an approach to recordkeeping that was person centred and that fully included them and their needs.

Eight key messages were identified from the MIRRA research:

-

Social care records have significant impacts on a care-experienced person throughout their life because the records act as a “paper self” long after the person has become an independent adult.

-

Accessing social care records is often difficult, both practically and emotionally, and can be traumatic and dehumanizing. Very little support is available.

-

Social care records often fail to meet basic memory and identity needs.

-

The voices, experiences, and feelings of children are rarely heard in their records.

-

Records management across the public, private, and voluntary care sectors is inconsistent, putting records at risk.

-

The outsourcing of children’s service provision without clear contractual obligations for recordkeeping is problematic.

-

The legislative and regulatory landscape for recordkeeping in child social care is confused and fragmented.

-

Lack of understanding regarding provisions for access to records for research purposes limits the public benefits of independent scrutiny of child social care.

MIRRA research evidenced that many people who grew up in foster and residential care have gaps in their childhood memories and unanswered questions about their early lives. In family settings, photographs and shared stories often document significant events, creating a sense of belonging and identity. In the absence of these resources, care-experienced people need to turn to their social care records as the only available resource to make sense of their lives. These records can provide answers to a range of questions – from family information and medical data to events in childhood. As Gina, a Care Leaver, noted,

There came a point where I wanted to know where I’d been, I wanted to know who’d fostered me, because there were little chunks of my life missing, like where I’d gone to school? Did I have any friends? How long was I there? And then somebody mentioned to me, “Why don’t you get your files?” . . . that’s what spurred me on to do it, because I wanted to know, I wanted to fill in these bits that were missing in my life.

Gina was given access to her files and supported by a social worker to process the information they contained. The information helped her make sense of her past and understand that she was not to blame for having been placed into the care system. As noted in other research, children commonly associate removal from a family with their own failings.[19] For Gina, the experience of accessing her files was positive and life changing. Sadly, this outcome was rare.

Linda described her experience accessing her records:

What I wasn’t prepared for was the language. The absolutely terrible language, the way that I was written about. I just can’t imagine myself writing like that about a distressed, traumatized child . . . any time you’re writing about a child always think that child could go back and read that, and really think about how you’re writing stuff, because words are so powerful.

As John-george observed,

One of the most profound things for me about the file, and it screams the loudest, is my lack of voice . . . my voice is totally stolen and words are put in my mouth, saying this is how I feel about certain occasions and certain people, and at times there’s conflict with what I believe.

MIRRA evidenced that the full value of the records, both for the care-experienced person and the state, was not recognized and recordkeeping was often poor. Those providing services within the recordkeeping function often felt under-resourced and unsupported and did not recognize the value that better recordkeeping could bring.

Critical Framework Dimensions to Address Current Recordkeeping Problems

MIRRA identified four critical framework dimensions to providing person- centred recordkeeping: people, records creation, managing records, and records access. The first is the central tenet of the framework, connecting all other dimensions (see figure 1). The challenge is to meet the needs of all the actors within the framework, taking into account legal and safeguarding constraints, thus ensuring appropriate and caring person-centred motivation, resourcing, and support for records creation, management, and access.

figure 1

Dimensions of a person-centred framework for recordkeeping in out-of-home child-care contexts

Framework Dimension One: People—Centring People at the Heart of the Recordkeeping Process

A person-centred framework reframes relationships to become balanced partnerships; it positions the needs of the care-experienced person at the heart of the process and acknowledges that person’s role and their ability to contribute to the creation of their records while in care. It acknowledges that the record is created for that person’s benefit and that their relationship with the record continues throughout life.

In a person-centred framework, the roles and responsibilities of all critical supporting actors are recognized. This means that different voices, perspectives, and recording needs are fulfilled, including those of the care-experienced person.

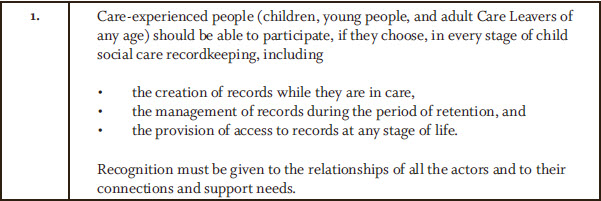

A person-centred framework acknowledges each actor’s requirement for resources and support, including the emotional needs of the child. The emotional labour of those in the professional roles also needs to be supported. Table 2 states the first MIRRA principle, which underpins the entire framework.

table 2

Situating the care-experienced person: The first MIRRA principle

The framework tools that support this principle include policies and processes that embed the needs of the care-experienced person at the centre of all practices. Children at each life stage must be provided with opportunities to create records, with the appropriate support. All those in professional roles need to be connected with training and support to help them better understand records creation and keeping. The emotional labour involved in the tasks needs to be recognized and supported. A stakeholder map with the full range of actors and their needs should be co-created.

Recordkeeping processes need to incorporate review, reflection, and change over time, positioning the care-experienced person at the centre. The corporate parent must understand its responsibilities and how these impact a Care Leaver throughout their entire adult life; that relationship should not end abruptly when a Care Leaver is 25 years old. The value of recordkeeping in maintaining a web of relationships through time needs to be recognized and resourced. Key framework tools associated with this first dimension include but are not limited to the following:

-

nomination of people with oversight for recordkeeping systems that put the care-experienced person at the centre

-

policies that embed the needs of the care-experienced person

-

stakeholder maps that identify all the actors and highlight their needs

-

training for all recordkeeping actors to help them understand how to deliver a caring, person-centred recordkeeping framework

-

support, recognition, and the facilitation of individual voices for all the actors

Framework Dimension Two: Records Creation

Our research has shown how integral records are to an individual’s sense of self and belonging. For children in care, the records are a tangible manifestation of their experiences, representing their most important relationships; for Care Leavers, the records may be the only access points to their past. We suggest that recording and recordkeeping should be seen as integral parts of caring for children.

All organizations that are part of the records creation process should have policies, procedures, and resources to support records creation as part of relationship development. Records co-creation should be an integral social care practice. Co-creation of records can result in relationships of communication, more complete records with recording of positive actions, and resources for sharing emotions.[20] Systems that are provided should allow for recording in ways that are not limited to tick boxes and short statements. Children should feel that the records are for them, and something they have a stake in, rather than a surveillance tool or performance measure for service providers that only reflects “official” views. Children should read, comment, and contribute to plans for their care. They should be actively involved in building their records, which should allow some space for their own independent, private recording. The personalized recording needs of children as they grow up to adulthood should be facilitated. Children need help to maintain, share, and retain those records through time and where they choose.

When different voices are brought in, their limitations need to be recognized and the basis on which they are speaking needs to be acknowledged. When a Care Leaver revisits their records later in life, it is important that they can distinguish between points of opinion and fact, and that they should hear from everyone who was involved in their care. The records need to be understandable (avoiding jargon) and compassionate to the child’s perspectives and to avoid judgmental commentaries. Mechanisms for correcting or adding to a record through time need to be a part of the co-creation and reflection process.

The relationship with a child’s family may vary, and it may not always be appropriate to share information with family members or ask them to contribute to the records. However, where possible, interacting with the child’s record could help family members to understand a situation. In addition, providing the opportunity for a family member to add to the record can assist with understanding family dynamics later.

In addition to textual records, other types of records – for example, photographs, certificates, artwork, and other mementoes – play an important role in memory and identity formation. These needed to be captured in out-of-home care contexts and transferred with the child, including from home or foster care contexts.

Our research shows that child social care produces huge quantities of complex, distributed records, with many organizations, agencies, carers, practitioners, and other stakeholders involved in creating information about each child. Children need to be engaged with recording and consulted about their needs in order to ensure person-centred records creation. Critically, this is about changing records creation cultures.

Table 3 presents MIRRA principles 2 to 17, which articulate critical considerations within records creation.

table 3

MIRRA principles of records creation

Key framework tools in support of the records creation dimension include the following:

-

policies that provide for person-centred records creation

-

training on what a caring record looks like, how to co-create records, and how to manage changes

-

resources and tools for children to create their own private records, which might or might not be shared

-

provisions to create and hold a range of record types but most particularly photographs, artworks, and other physical mementoes

Framework Dimension Three: Managing Records

All aspects of a recordkeeping system need to be reviewed to ensure that they are fit for purpose, including by identifying how the recordkeeping system helps or prevents children from participating. An analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) can assist with refocusing. Important questions include the following:

-

What records do we have?

-

Where are the records, and in what formats?

-

Why are we creating records?

-

Who are the records for?

-

How are they used/shared?

-

What plans do we have for their access, control, and management through time?

-

What are the issues and challenges associated with our current systems and practices?

-

What appropriate systems will enable us to co-create, manage, migrate, and maintain availability for all stakeholders?

Many of these questions can be dealt with through traditional records management tools. However, the person-centred shift comes in reviewing and reflecting upon the management of records from the perspectives of all key actors. Recordkeeping is a responsibility of all – not just of a professional records manager. For this reason, this dimension has been named “managing records” rather than “records management.” MIRRA found that care-experienced people do want to participate in all recordkeeping dimensions.

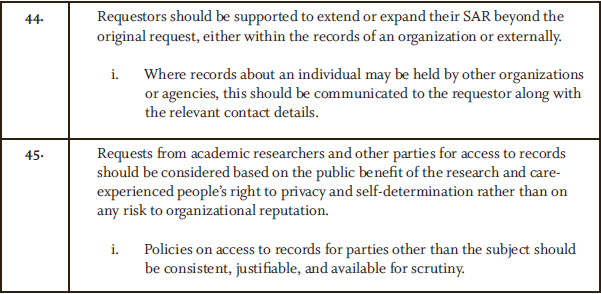

Organizations must have up-to-date policies and plans that embed person- centred principles and have been shaped through consultation with care- experienced people. While involving care-experienced people in service design is relatively common in frontline children’s services, it is less so within functions like records management and information governance.

In order to be properly accountable, organizations should know both what they do have and what they do not have. Where systems to gain control of all assets are lacking, an information audit should be undertaken. This should include surveying digital systems as well as physical records. The information asset register should link to information security programs that take account of these valuable assets. Physical, intellectual, security, and business continuity controls are critical.

As part of the audit, personal data must be identified, and records of processing activities for personal data created. The latter is a requirement of the UK data protection legislation, which requires organizations to map out where personal data are created, by whom, and to whom they relate and then to record where and how they are shared. It is personal information that often matters most to the care-experienced person.

The legal requirements for each organization must be documented and available to all those involved in recordkeeping to provide a minimum requirement for creation and retention. However, the legal picture is not the whole story. Retention and destruction schedules should be created through discussion with all key stakeholders to take account of operational, accountability, research, and, critically, memory needs of individuals. In many cases, retention periods far longer than legislative minimums will be required to meet a range of societal needs.

Where records are retained, they must be stored in appropriate conditions. For paper, this means they must be catalogued, indexed, and stored in a clean, dry place in lidded, clearly labelled boxes, and they must be easily retrievable, including from outsourced services. Digital systems must provide for the needs of the child to co-produce and access records. User requirements and system selection for new systems should involve care-experienced stakeholders.

Individual recordkeeping by children, including creating digital records and capturing physical mementoes, needs to be enabled. MIRRA research underlined the vital importance of tangible and original photographs, life story work, letters, school reports, and certificates to care-experienced people. Any digitization program that involves the subsequent disposal of the paper originals should identify and retain personal memory items.[21]

Where records are destroyed or deleted, this should be documented. Organizations should build up care file histories so that they can account to Care Leavers for destroyed records.

Records must be actively managed and maintained, and clear preservation and digital curation planning must include relationships with archives. In England, records relating to looked-after children must be retained for at least 75 years (and preferably 100 years) and retained in accessible, legible, and usable formats. However, planning and resourcing for digital curation was rarely identified.

Recordkeeping must be properly resourced to ensure organizations can discharge their obligations to care-experienced people. Recordkeeping should be subject to review, reflection, change, and audit by the critical stakeholders. We suggest that organizations work to create a caring culture of child-centred recordkeeping by revisiting recording policies, standards, or guidance collaboratively with Care Leavers. Person-centred recordkeeping responsibilities should be included in the role descriptions of all staff who contribute to records, whether in social care or information management teams.

MIRRA principles 18 to 27, which address person-centred management of records, are set out in table 4.

table 4

MIRRA principles for managing records

Key framework tools for managing records include the following:

-

policies and training that enable person-centred records management

-

information audits and registers that identify all information assets, including personal data and both current and legacy systems

-

records of processing activities for personal data

-

retention and disposition schedules that recognize not only legislative requirements but also the wider value of records to care-experienced people

-

retained disposition records with sign-off processes

-

sharing protocols

-

records management plans that include access by design and processes for indexing and retrieval

-

procurement processes that involve care-experienced stakeholders in selecting user requirements and systems

-

preservation and storage planning for both paper and digital records

-

tender, procurement, and commissioning services agreements

-

histories of custodianship for records

-

audits and reviews of all processes

-

a SWOT analysis that can act as an aid for reflection

Framework Dimension Four: Caring Records Access

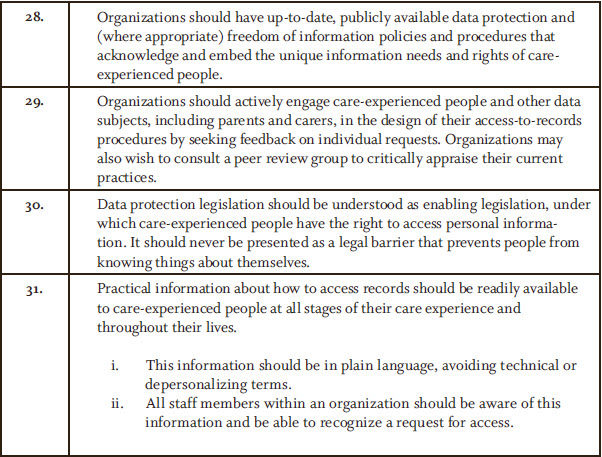

In England, all organizations must comply with data protection legislation, ensuring that they create, collect, manage, process, and keep personal data lawfully and in accordance with key principles. Access by design should be built into recordkeeping frameworks from the outset. Care-experienced people have the right to request access to information and to receive that information, subject to any exemptions, within one month (or three months if the request is complex).

MIRRA underlined the importance of providing information about access to records in multiple ways. When children are in care, age-appropriate access to records should be a standard part of person-centred recording practice. Children who ask questions about their earlier lives can read records with their social workers. Access to records should be through simple and understandable processes with opportunities for support. Frontline staff within organizations should be aware of care-experienced people’s rights and be able to support record access appropriately. The advice that is provided should be clear and honest about the process, what to expect, and how to get support.

While organizations in England have up to three months to respond to complex SARs, many take longer. We would recommend that acknowledgement of an access request explains how the request will be dealt with, including how records will be found, how long it will take to retrieve them, and how redactions may take place. Likely time frames for responses should be provided from the outset and updates given proactively at each step.

Redaction is not solely a functional or administrative task but contributes toward caring corporate parenting throughout a person’s life. The need to exercise discretion and judgment, and to apply nuanced decision-making frameworks, means that this task should not be given to inexperienced staff. Where possible, access requests should be part of a core job role.

MIRRA argues that all information in a person’s individual care file is their information. If a social worker considered it relevant to the process of making decisions about a person’s life, then it is salient to their lived experience and therefore can be disclosed. In these circumstances, true third-party information is rare. Organizations demonstrating best practice in redaction took this position. In addition to improving access outcomes, it greatly reduced the time spent redacting so that requests could be processed more quickly, efficiently, and cheaply.

Where redactions are needed, then they must be specifically explained to help a care-experienced person to accept the decision and navigate their records without getting stuck on what is missing. If each redaction is stamped (literally or virtually) with the explanation – for example, “information relating to unrelated child,” or “information relating to foster carer’s personal life” – a sense of trust and mutual respect could be built. This practice encourages practitioners undertaking redacting to reflect on and justify their reasoning, and it enables the care-experienced person to make informed decisions about whether they wish to challenge redaction decisions. Where the serious harm exemption applies, then this needs to be carefully justified. It is not enough to redact information on the basis that it could be upsetting. While many social workers mistakenly applied this approach, it would be rare to see circumstances where this particular exemption, as understood by the law, was applicable.

Complaint procedures need to be explained. Redaction decisions can be reversed if a Care Leaver can demonstrate that they are unnecessary or unreasonable. Clear information and support should be given to care-experienced people wanting to challenge and question decisions about record access.

If a care file no longer exists or cannot be found, how this news is shared is extremely important. As much information as possible on why the information does not exist should be provided, along with the opportunity to ask questions. We found that organizations that had a developed sense of their own recordkeeping history, for example, Gloucestershire County Council, were more easily able to account for and explain what was missing. In the absence of a personal file, histories can be compiled with reference to organizational minutes, newsletters, and other archival sources. These other records should at least encompass what services were offered, when, and by whom; what institutions or centres were in operation; and what legislation or policy was applicable to the organization’s care of children.

Organizations differ significantly in terms of how much contact they have with care-experienced people during the SAR process. Some organizations maintain high levels of communication throughout, as a way both to guide decision-making (e.g., determining what to redact based on what a person already knows) and to provide personal and emotional support. Barnardo’s, for example, begins the access process with an exploratory phone call. We found that some care-experienced people really appreciated this opportunity to talk and found it valuable to build relationships with the people who were dealing with their requests. It provided them with an opportunity to better understand the process and develop a level of trust. However, we found that some Care Leavers felt the opposite. They wanted no more contact than was absolutely necessary with the organization that had looked after them. They may have had negative associations that make communicating with representatives of the organization difficult.

Accessing records can be a deeply emotional and sometimes traumatic experience. Although, in the long term, many care-experienced people say that they are glad they did it, in the short term, people report a range of feelings and responses – many of which can be intense and upsetting. Under the UK Children and Families Act 2014, trauma-informed support is mandated for Care Leavers up to the age of 25, who meet the government definition of Care Leavers. However, for adults over this age, support is not mandated and rarely given. In some instances, there are specialist in-house teams of social workers, mental health workers, and trauma specialists to provide support. Even if there are no internal resources, organizations should provide information about the available support from national voluntary and peer-led organizations such as Family Action or the Care Leavers’ Association. At least some support options should be independent of the organization fulfilling the request. Some Care Leavers lack trust in the organizations that cared for them, which may have been responsible for harm they experienced. Support should be a critical part of the access package. While some people want to talk about their experiences immediately, others find that it affects them months or even years down the line. Support options should not be time limited.

Our research clearly showed that individual flexibility in processing access requests was important. Every care-experienced person wants and needs different things from the process. Most critical is their right to self-determine what is comfortable and reasonable for them. We therefore suggest that organizations should offer a range of options at the outset of the process.

Freedom of information (FOI) requests can provide another route to accessing broader information about social care and can help Care Leavers contextualize their own experiences. Such requests might enable them to hold an organization to account for inadequate or negligent practices. In England, only public authorities are subject to the Freedom of Information Act 2000. Third-party care providers[22] are exempt, but MIRRA proposes that care providers should nevertheless respond to such requests in a similar and open manner.

Researchers also have a legitimate need to access records for research that will benefit society, to make sense of past child-care provisions, and to improve future services. Organizations that hold records need clear protocols to enable research access, with safeguards to ensure the privacy rights of care-experienced people. When writing about care services and care-experienced people, researchers should fully recognize the rights of these people and work respectfully and caringly.

MIRRA principles 28 to 45, in table 5, address caring and person-centred records access.

table 5

MIRRA principles for accessing records

Key framework tools to enable caring records access include the following:

-

communication strategies, policies, and processes that provide information to care-experienced people, in plain language, on their rights to access information

-

well-trained frontline staff who can direct care-experienced people appropriately

-

well-trained staff to manage access requests

-

different approaches to handling requests to meet individuals’ unique needs, e.g., through phone calls, emails, or letters

-

access by design, with the release of as much information as possible and explanations of any withheld information and processes for complaints and questions

-

custodial histories to assist with explaining the absence of records and providing wider contextual information

-

support for accessing records that takes into account trauma

-

access policies, processes, and safeguards for researchers

Conclusions

Caring, person-centred recordkeeping will help to ensure that the lifelong needs of care-experienced people for memory, identity, and information are met and that there is support and acknowledgement for all the actors involved. Making the records creation processes part of the relationship between critical supporting actors and the care-experienced person will enable delivery of the full value of recordkeeping. Better-quality records should be created to provide a mechanism for exchanging information that captures the child’s voice and includes memory content. Respect for the care-experienced person, including their need for personal recording space, is critical at all stages of the process.

All organizations with safeguarding responsibilities and guardianship of children’s memories should have plans, proper resourcing, and appropriate expertise for managing care-experienced people’s records. These should outline processes for records creation, sharing, and retention and should include recommendations for longer-term archival preservation. Records should not be retained just for legal time frames but should satisfy the longer-term needs of care- experienced people. Recordkeeping should enable better accountability and data sharing between the public sector, third sector, and private sectors. Recordkeeping systems should be designed to incorporate the best-practice principles of access by design from the outset. Care-experienced people should be provided with opportunities to contribute to decisions about their life-records and to be fully informed of their rights and how to exercise them. Recordkeeping systems need to be responsive and flexible to enable person-centred approaches. This is not without challenges and requires reframing ways of designing systems, working, and interacting. If the state is to truly provide “care” and to adopt lifelong responsibilities of the parent as we recommend, then person-centred recordkeeping is an essential step forward.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Elizabeth Lomas is an associate professor in information governance in the Department of Information Studies at University College London (UCL). She is Chair of the UK and Ireland Forum for Archives and Records Management Education and Research. Her research interests focus on shifting perspectives on information rights and delivering empowered recordkeeping processes. She is the policy lead on the MIRRA project. In addition, she is currently working on a number of funded international information change projects. She is a co-editor of the international Records Management Journal and a member of the ISO standards records management and privacy technologies committees.

Elizabeth Shepherd is a professor of archives and records management in the Department of Information Studies at UCL and Head of Department. Her research interests are in rights in records, links between records management and information policy compliance, and government administrative data including the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)-funded project with care-experienced co-researchers, MIRRA. She serves on editorial boards for key journals and served on the UK national research assessment panels for Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) 2008, Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014, and REF 2021. She has published numerous articles and (with Geoffrey Yeo) the best-selling book Managing Records: A Handbook of Principles and Practice (Facet Publishing, 2003).

Victoria Hoyle is a lecturer in public history and Director of the Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past at York University. Her research engages with 20th- and 21st-century histories of health and social care using participatory and co-productive action methodologies. She was the Research Associate on the MIRRA project at UCL from 2017 to 2019. Her current project explores the ways in which histories of child sexual abuse have been constructed and presented in the context of transitional justice processes in Britain and Ireland. Her book The Remaking of Archival Values will be published by Routledge in 2022.

Anna Sexton is Programme Director for the MA in Archives and Records Management at UCL, leading on introducing the students to recordkeeping theory that draws on interdisciplinary perspectives. Her PhD research was in the documentation of lived experience of mental health, and her broader research interests include participatory approaches, friendship as research method, and social justice–oriented recordkeeping, particularly in health and social care contexts. She was previously Head of Research at The National Archives, UK. She is currently a co-investigator on the AHRC-funded MIRRA+ project and Deputy Director of the AHRC London Arts & Humanities Partnership.

Andrew Flinn is an archival and oral history reader at UCL. He is a trustee of the British Library’s National Life Stories, vice-chair of the UK Community Archives and Heritage Group, a member of International Council on Archives’ Archival Education Steering Committee, and co-leader of the Archives Gothenburg/UCL Centre for Critical Heritage Studies. His research interests include independent and community-based archival practices, archival activism and social justice, and participatory approaches to knowledge production aiming at social change and transformation. Recent publications include (with Wendy M. Duff, Renée Saucier, and David A. Wallace) Archives, Recordkeeping and Social Justice and (with Jeannette A. Bastian) Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity.

Notes

-

[1]

Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory,” Archival Science 2, no. 1–2 (2002): 1–19; Rodney Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence,” Archivaria 61 (Spring 2006): 215–33; Anne J. Gilliland and Sue McKemmish, “The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery,” Atlanti: Review for Modern Archival Theory and Practice 24 (2014): 78–88. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12541.

-

[2]

Jeannette A. Bastian and Andrew Flinn, eds., Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity (London: Facet, 2019).

-

[3]

Cassie Findlay, “Participatory Cultures, Trust Technologies and Decentralisation: Innovation Opportunities for Recordkeeping,” Archives and Manuscripts 45, no. 3 (2017): 176–90; P. Van Garderen, “Decentralized Autonomous Collections,” On Archivy, April 11, 2016, https://medium.com/on-archivy/decentralized-autonomous-collections-ff256267cbd6.

-

[4]

Nicola Laurent and Kirsten Wright, “A Trauma-Informed Approach to Managing Archives: A New Online Course,” Archives and Manuscripts 48, no. 1 (2020): 80–87; Jennifer Douglas, Alexandra Alisauskas, and Devon Mordell, “‘Treat Them with the Reverence of Archivists’: Records Work, Grief Work, and Relationship Work in the Archives,” Archivaria 88 (Fall 2019): 84–120.

-

[5]

Mike R. Nolan, Sue Davies, Jayne Brown, John Keady, and Janet Nolan, “Beyond ‘Person-Centred’ Care: A New Vision for Gerontological Nursing,” Journal of Clinical Nursing 13, no. s1 (2004): 45–53; Angela Coulter and John Oldham, “Person-Centred Care: What Is It and How Do We Get There?” Future Hospital Journal 3, no. 2 (2016): 114–16; Maria J. Santana, Kimberly Manalili, Rachel J. Jolley, Sandra Zelinsky, Hude Quan, and Mingshan Lu, “How to Practice Person-Centred Care: A Conceptual Framework,” Health Expectations 21, no. 2 (2018): 429–40.

-

[6]

Health Innovation Network, What Is Person-centred Care and Why Is It Important? ([London]: Health Innovation Network South London, n.d.), https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/system/ckeditor_assets/attachments/41/what_is_person-centred_care_and_why_is_it_important.pdf.

-

[7]

Sanna Rimpiläinen, Person-Centred Records. A High-Level Review of Use (Glasgow: Cases: Digital Health and Care Institute, University of Strathclyde, 2019), https://doi.org/10.17868/69249.

-

[8]

Margaret C. Broderick and Alice Coffey, “Person-Centred Care in Nursing Documentation,” International Journal of Older People Nursing 8, no. 4 (2013): 309–18.

-

[9]

Katherine Choi, Yevgeniy Gitelman, and David A. Asch, “Subscribing to Your Patients – Reimagining the Future of Electronic Health Records,” New England Journal of Medicine 378, no. 21 (2018): 1960–62.

-

[10]

Social Care Institute for Excellence, “Social Care Recording,” SCIE, August 2021, https://www.scie.org.uk/care-providers/recording.

-

[11]

Victoria Hoyle, Elizabeth Shepherd, Andrew Flinn, and Elizabeth Lomas, “Child Social-Care Recording and the Information Rights of Care-Experienced People: A Recordkeeping Perspective,” British Journal of Social Work 49, no. 7 (2019): 1856–74.

-

[12]

Joanne Evans, Sue McKemmish, and Gregory Rolan, “Participatory Information Governance: Transforming Recordkeeping for Childhood Out-of-Home Care,” Records Management Journal 29, no. 1–2 (2019): 178–93.

-

[13]

Department for Education and Office of National Statistics. Statistical Report: Children Looked After in England (Including Adoption), Year Ending 2017 (London: HMSO, 2017), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664995/SFR50_2017-Children_looked_after_in _England.pdf.

-

[14]

National Statistics, “Reporting Year 2021: Children Looked After in England Including Adoptions,” Gov.UK, November 18, 2021, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2021.

-

[15]

MIRRA care-experienced co-researchers gave permission for the use of their own testimonies attributed to their names.

-

[16]

Elizabeth Shepherd, Anna Sexton, Elizabeth Lomas, Peter Williams, Mark Denton, and Tanya Marchant, “MIRRA App SRS: Memory – Identity – Rights in Records – Access Research Project: A Participatory Recordkeeping Application Software Requirements Specification (SRS),” Zenodo, October 26, 2021, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5599430.

-

[17]

British Association of Social Workers, 10 Top Tips: Recording in Child’s Social Work (Birmingham: BASW, 2020), https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_recording_in_childrens_social_work_aug_2020.pdf.

-

[18]

This experience accorded with perspectives of care-experienced people in other countries. See Gregory Rolan, “Agency in the Archive: A Model for Participatory Recordkeeping,” Archival Science 17, no. 3 (2017): 195–225.

-

[19]

Gail Heyman, Carol Dweck, and Kathleen Cain, “Young Children’s Vulnerability to Self-Blame and Helplessness: Relationship to Beliefs about Goodness,” Child Development 63, no. 2 (1992): 401–15.

-

[20]

Dennis Saleebey, The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice, 6th ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013).

-

[21]

Kate Roach, Trish Scott, Kelly Ulugan, and Megan Parker, “Barnardo’s Making Connections: Supporting Care Leavers to Access Records,” Practitioner Perspectives (London: UCL Information Studies, 2019), https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.ucl.ac.uk/dist/1/627/files/2019/07/Practitioner-Perspectives.pdf.

-

[22]

Public authorities may contract parts of their services to private entities. Third parties may be commercial or charitable enterprises with differing emphases on their delivery priorities. Critically, third-party providers are not subject to the same level of accountability as public authorities; for example, they are exempt from freedom of information legislation.

Liste des figures

figure 1

Dimensions of a person-centred framework for recordkeeping in out-of-home child-care contexts

Liste des tableaux

table 1

Critical supporting actors

table 2

Situating the care-experienced person: The first MIRRA principle

table 3

MIRRA principles of records creation

table 4

MIRRA principles for managing records

table 5

MIRRA principles for accessing records