Résumés

Abstract

Urban odonyms and public art that refer to the Chilean dictatorship (1973–1990) are artifacts within the cultural landscapes of Toronto, Laval, and Montreal. As commemorative material devices, I suggest odonyms and public art offer a symbolic way to cope with the experience of exile. Furthermore, these artifacts create social relations between Chilean exiles and Canadian urban spaces that contribute to forming a foreign community and define their present and future. Using a series of photographs, I chronicle the memorialization in Canada of a traumatic period in recent Chilean history.

Keywords:

- odonyms,

- public art,

- exile,

- dictatorship,

- Chile

Résumé

Les odonymes urbains et l’art public qui font référence à la dictature chilienne (1973-1990) sont des artefacts dans les paysages culturels de Toronto, Laval et Montréal. En tant que dispositifs matériels commémoratifs, je suggère que les odonymes et l’art public offrent un moyen symbolique de faire face à l’expérience de l’exil. De plus, ces artefacts créent des relations sociales entre les exilés chiliens et les espaces urbains canadiens qui contribuent à former une communauté étrangère et à définir leur présent et leur avenir. À l’aide d’une série de photographies, je fais la chronique de la commémoration, au Canada, d’une période traumatisante de l’histoire récente du Chili.

Mots-clés :

- odonymes,

- art public,

- exil,

- dictature,

- Chili

Corps de l’article

Introduction

In 2016, I began a long-term project examining memories and materialities of the Chilean dictatorship (1973–1990), particularly with Chilean exile and immigration to Canada. Several quantitative and qualitative studies have investigated Chilean exile and migratory flows in Canada (Bascuñán and Borgoño 2015, 2021; Da 2002; Fornazzari 2018; Landolt and Goldring 2006; Peddie 2012). However, I explore political exile from a material perspective and consider Canadian urban contemporary materiality as part of a broad interest in the politics of commemoration and recognition (Huyssen 2003). The objective is to enhance the interpretation of exile experiences by exploring materialities that create a sense of belonging for Chilean exiles in their new host city. The project examines what I call “exile materialities.” I utilize a combined methodology that includes the analyses of contemporary artifacts (for example, artwork, photographs, objects, monuments), archival documents (for example, letters, diaries, newspapers), participant observation in social events, and interviews with political actors, artists, cultural managers, and mainly, Chilean exiles in Canada.[1] I follow the trend of other studies related to memorials of the recent Chilean past (for example, Obregón Iturra and Muñoz 2015). In the following pages, I do not aim to explain the depth of the theoretical debates around memory and memorialization. Instead, I suggest that certain kinds of materialities, such as odonyms and public art, are exile materialities that connect people, places, and objects. As a Chilean immigrant reflecting on the experience of being a “stranger in a strange land,” I think about exile and immigration more broadly, from a perspective that recognizes the possibilities of social encounters enabled by these contemporary urban artifacts. I hypothesize that this connection through material devices opens and creates symbolic healing spaces for exiled Chileans. Thus far, no research in Canada has studied the healing aspect of urban materialities associated with exile. This approach uses a different angle to understand urban devices as mechanisms for rooting communities in exile—a perspective that deserves to be explored on its own.

16 October 1998

This day was a milestone in Chilean history. The former dictator Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London, and the event quickly became a landmark moment in international politics. “You have no right to do this. You can not arrest me! I am here on a secret mission!” cried the dictator (Montes 2018) (my translation). Pinochet’s bloody dictatorship started with a coup d’état on 11 September 1973 that overthrew Salvador Allende, the world’s first democratically elected socialist president. During the Cold War, the principle of universal jurisdiction had not been applied. Pinochet’s arrest was the first time a former head of state did not have immunity for international crimes, such as torture and genocide. Henceforth, other countries arrested dictators and criminals under the principle of universal jurisdiction. For example, in 2005, Belgium succeeded in having Senegal capture Hissène Habré, the former head of state of Chad from 1982 to 1990, who was accused of political murders, torture, and ethnic persecution, among other crimes. Although Pinochet was eventually released and returned to Chile in early 2000 using questionable political and diplomatic maneuvers, the arrest of the former dictator marked a turning point in the legal application of the principle of universal jurisdiction.

In the early 1990s, Patricio Aylwin’s government had already made some political progress toward investigating human rights abuses committed by the dictatorship (for example, the 1991 Rettig Report). However, it was only in the late 1990s that Chile began an exhaustive institutional process that led to the opening of hundreds of cases of human rights violations. In addition to the judicial prosecution of former members and accomplices of the dictatorship, Chile steadily began to memorialize the dictatorship’s victims by creating symbolic spaces, such as parks and street names, to remember those grim years. For example, the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago (Museo de la Memoria y Los Derechos Humanos) opened in 2010 because of the cooperation between state institutions and social organizations. The same phenomenon began abroad in exiled Chilean communities in countries that had received immigrants or refugees. Canada was one of the major countries to do so[2] (Bascuñán and Borgoño 2015, 2021; Simmons 1993). In this essay, I use photographs with brushstrokes of colour on a colourless background to chronicle, like field notes, this memorialization process that was part of a global phenomenon of commemoration, what Huyssen (2003) calls the “boom of memory.” Photographic intervention is, in a sense, a form of mediation in a virtual space. As James Herbert pointed out about nineteenth-century French paintings, “the strong subjectivity of the artist creates the brushstroke, while the brushstroke divulges the essence of the artist” (Herbert 2015, 1). In each photograph, brushstrokes are also a political stance, as they are a personal kind of virtual appropriation of the artifacts depicted and fixed in the urban space. If, as I argue, odonyms and public art are brushstrokes of colour to memorialize “a past that hurts” (Fuenzalida 2017), in the photographs, they are also an invitation to see and appreciate these exile materialities differently. Like photography, brushstrokes can also be “ends of their own” (Herbert 2015). They both shape together and at once, a form of visual register, a method of intervention, appropriation, and expression.

28 September 2004

Four years after Pinochet’s release from London, the Laval city administration in Quebec confirmed that one of its streets would bear the name of Salvador Allende[3], the former Chilean president overthrown by the Pinochet coup (see Figure 1). An odonym is a name associated with a communication route such as a street, an alley, or an avenue. Its importance for postcolonial, urban, and critical toponymy studies is well known (Azaryahu 1996; Berg and Vuolteenaho 2009; Bouvier and Guillon 2001; Casagranda 2013). As Dominique Badariotti has explained, “it must be noted that it is not insignificant to baptize a street ‘Joan of Arc,’ a square ‘Salvador Allende,’ or to give names of European cities to an entire district” (Badariotti 2002, 285–286) (my translation). Urban odonyms provide symbolic landscapes within urban spaces and give meaning to places. Thus, I can understand a city’s past and present through its odonyms because they bear traces of successive evolutions, extensions, and urban development (Badariotti 2002). Seeing the panel with Allende’s name on it in a residential (and relatively wealthy) neighbourhood in the suburbs of Laval, it seems strange to me to think that the odonyms could express the aspirations of their communities in providing what Don Mitchell (2003) has referred to as “the right to the city.” Nevertheless, the odonym proves to be a good starting point for the project.

Figure 1

16 September 2006

On this date, a new street name is unveiled in Toronto that bears the name of a Chilean individual. Located in the Davenport neighbourhood, the new Victor Jara Lane is not remarkably different from the other alleys in the area (see Figures 2 and 3). Victor Jara was a popular Chilean musician, poet, and cultural manager assassinated two days after Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état. The naming of the lane was part of an artistic initiative fostered by the Latin American Canadian Art Projects (LACAP)[4] association to commemorate Latin American artists and cultural characters. LACAP presented the project to the local government, which authorized it in adherence to the city administration’s public policies that encouraged the expression of cultural diversity.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Walking through the streets of Toronto and discussing the past and political violence made me think about several questions. Far from the CN Tower and other popular, crowded tourist attractions in Toronto, I visited small corners that interested me because of their singular value. Victor Jara Lane immediately drew my attention as the best example to think about the relations that migrant communities create and maintain with places and public spaces (compare Moretti 2017; Yi’En 2014). The lane allowed me to explore discreet artifacts that constitute urban life. Despite its inconspicuous character, it awakened in me memories of the recent political history of Chile (Meade 2004). As I walked down the lane, political events of the 1980s were vivid and coloured. Oddly, Victor Jara Lane also awakened a sense of belonging to an imagined Chilean Canadian community (Anderson 2006) to which, ironically, I had no real connection. It seemed to be a place that reassembles while not physically encountering others. It has symbolic and interpretative significance as a contemporary, discreet, and politically charged urban object. Thus, I followed what Dominique Badariotti (2002, 286) calls “the poetic role” of a street or square name, which is the ability to evoke the past and to create or collect memories.

11 September 2009

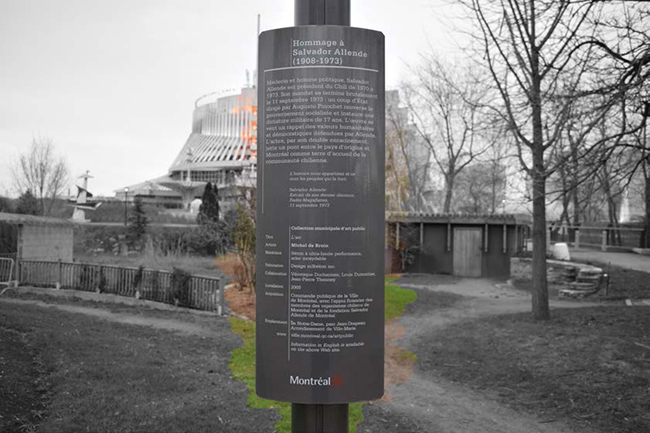

In the Jean Drapeau Park in Montreal, a steel plaque with a brief biography of Salvador Allende is next to Quebec artist Michel De Broin’s sculpture titled “L’Arc” (see Figure 4). Measuring 280 x 472 x 127 centimetres, L’Arc is composed of concrete and stainless steel, a way to highlight the material symbols of urban life (see Figure 5). It was installed in 2009 in the Jardins des Floralies, the section of the park that has featured commemorative and artistic works since the 1967 International and Universal Exposition. L’Arc is located in a natural environment with its materiality creating “a subtle and effective formal dissonance with the surrounding trees.”[5] The sculpture also dilutes the frontier of nature and culture with its form and material. It is lost in its environment, confused with the park’s landscape but outside the imposing visual framework of the nearby city’s casino (see Figure 6). Representing “a curved tree whose canopy seeks the soil of its origin,”[6] through its double roots, the artwork creates a bridge between Chile, the country of origin, and Montreal, a welcoming land for the Chilean community. For the artist, “the circular line that draws the arch can be seen to suggest further an organic relation between the past and the present, as well as a site for circulation, meditation, and contemplation.”[7]

By commemorating an individual and a significant episode in Chile’s history, is L’Arc a symbolic healing space? As a speculative interpretation, I suggest that this artwork connects a foreign community and enables many exiled people to form bonds and interact in a public space, even if they do not know each other. It connects them with the city of Montreal and with other Chileans without the need for them to be physically present. Viewing the sculpture as a mere thing limits how we address and perceive the past’s relevant social and emotional spheres. L’Arc facilitates an understanding of how artwork shapes social life and, perhaps more importantly, how it activates and evokes affection (Navaro-Yashin 2009). Obviously, healing is not the only possible effect of these memorials; they can also elicit feelings of rejection, ignorance, and indifference. I highlight only one of many possible dimensions that we can use to view these objects.

Similarly, I suggest that L’Arc activates different temporalities simultaneously as it evokes the past and celebrates the present and future. As a symbolic object, it allows the exploration of the materialization of intercultural relations. It prompts questions about how and why immigrants arrive in a new city and how they engage with its scattered material world and the past anchored within it. Located in the symbolic Jean Drapeau Park, L’Arc is not only artwork of the past but also an artifact for the future because it provides a sense of belonging to Chilean immigrants. As some interviewees emphasize, the political practices preserve the past or at least a part of it. I argue that the feeling of belonging emerges less through commemorating an event of the past than through participating in the historical trajectory of the commemoration process itself. This interpretative turn allows some Chilean exiles to acknowledge urban artifacts as the materialization of an active agency of spatial appropriation and not simply as monuments that memorialize passive victimhood of a traumatic and overwhelming event. Healing situates itself in part in that turn, where the experience of exile is a continuous “process of becoming” (Deleuze and Guattari 1972), folding the past and the present (Robb 2020). Here also lies the multitemporality of L’Arc—the timelessness of the concrete and steel rods and the transience of the wood of the trees.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

20 September 2012

On this anniversary of Pinochet’s coup d’état, the Laval municipality gave the name Salvador Allende to a little park located on a homonymous street (see Figure 7). The city added a new material device with political significance to a physical space that has little or nothing to do with the name it bears. How many residents know its history? How many residents feel connected to it? Probably none. How many city residents will feel a connection to the name? Perhaps many[8]. What seems more evident is that one should not take for granted the existence of a single type of agency associated with these artifacts.

Figure 7

On the contrary, none of these artifacts has a unique agency for those who live on the streets where they are located or for the urban population. Of course, the point here is not to elucidate a direct relationship between the odonyms and the communities that inhabit the streets where these names are inserted but to evaluate the symbolic value of these artifacts and their relationship to the city’s urban landscape. Street naming is undoubtedly significant for those who reside in the same town and feel connected to them or for those who associate these names with family stories, individual memories, missing relatives, traumas, and uprooting. I do not argue that the mere fact of a street designation is enough to heal the wounds of the past. Healing does not mean closing; on the contrary, it implies resignifying, updating, and reviving the past.

10 September 2017

In commemorating the coup d’état against Salvador Allende, Salvador Allende Court was unveiled in Toronto a few blocks south of Victor Jara Lane. At least a hundred Chilean residents from the city and the surrounding area attended the inauguration (see Figure 8). “You know, the street gives historical content to local space,” said Mauricio,[9] board member of Casa Salvador Allende, a Toronto-based Chilean organization that promotes political, cultural, and social activities for the Chilean resident community (personal interview, 1 October 2020). Naming Salvador Allende Court was a long process that started in at least 2000, the year of Pinochet’s release from detention in London. Mauricio initiated the project to commemorate Salvador Allende, thinking of an object that would be functional in the city’s daily life and thus more visible than a commemorative plaque. The prospect for this new object had three requirements: (1) it must have good visibility, (2) it must be part of the daily life of the residents and the urban traffic, and (3) it must be closely connected with the cultural environment of the neighbourhood, not necessarily linked to the Chilean community living there. Discussed in several City of Toronto administrative meetings, the name of the street was finally approved unanimously in August 2014. But, as Mauricio has explained, this work was only made possible by “the political conditions of a given period” (personal interview, 1 October 2020).

Figure 8

This event for unveiling the street name brought the community together. As the Canadian and Chilean keynote speeches highlighted, the commemoration of the former president demonstrated the relevance of the recognition of a foreign community within a newly constituted urban space. Furthermore, this event openly sought to replicate the so-called actos organized during the Chilean dictatorship by its exiled communities in different countries. “The actos offered an occasion for affected members of the exiled Chilean community to assemble, to communally mourn, and to implicitly forge mutual understanding of circumstance” (Simalchik 2006, 99). The event organizers removed the blue cloth covering the street signage in an almost sacred act between speeches, poetry readings, musical presentations, laughter, and hugs (see Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9

Figure 10

The odonym transcends its mere materiality and intertwines with sensory attributes typical of urban life (Pink 2009), such as vehicle traffic noise, the sound of the bus stop announcement, and the movement of pedestrians at a bus stop (Moretti 2017). Moreover, Salvador Allende Court is not just a residential address, as highlighted by Mauricio in our conversations. It is also a meeting point for local Chileans and even a destination for some tourists visiting the city. Urban landscape artifacts such as odonyms thus become gateways of citizen awareness that convey specific symbols and values (Badariotti 2002). They facilitate understanding some of the reasons and circumstances of the arrival of an exiled community and its connection to the social and symbolic contexts, an understanding made possible through the intrinsic attributes of urban materiality (see Figure 11).

Figure 11

Conclusion

I started the project on exile materialities by examining three odonyms and one sculpture as examples of Canadian urban artifacts that memorialize recent Chilean history: the Victor Jara Lane in Toronto, the Salvador Allende streets in Laval and Toronto, and L’Arc, a sculpture erected in Montreal’s Jean Drapeau Park. This research is distinct because it examines a Chilean living past that refuses to be hidden and forgotten (Cáceres 1992; Carrasco, Jensen, and Cáceres 2004; Fuenzalida 2017; Fuenzalida et al. 2020; Vilches 2011), a living past of political repression that is also materialized in exiled contexts. I approached the above examples with broad and open questions. Can Canadian urban odonyms and public art related to the Chilean dictatorship serve as contemporary artifacts that reflect a city’s cultural and symbolic landscapes as the materialization of intercultural relations? Can Chilean political violence materialized in Canadian urban cultural places and objects be understood not as isolated objects but as symbolic healing spaces for exiled Chileans in Canada that help them cope with the exile experience? The breadth of the questions undoubtedly blurs any possible collective answers, but it does not prevent us from examining the material expressions. As a Chilean immigrant walking the streets of Toronto or Montreal, urban artifacts triggered a connection to a community I did not know existed (see Figure 12). The examples presented here lead me to reflect on concepts related to odonyms and public art as significant urban artifacts, exiled immigrants as dynamic configuring agents of the symbolic urban landscape, and contemporary materialities as possible urban spaces of symbolic healing. I approached them, hoping to add a more nuanced view to commonly used sociological categories, such as immigrants. Joan Simalchik rightly noted that Chilean exiles “were not immigrants seeking a new land, nor were they refugees hoping to be permanently resettled” (Simalchik 2006, 96). What were they? What have they become?

Figure 12

Odonyms are inserted in political and historical contexts; evidently, every public space can be politically manipulated (Guyot and Seethal 2007; Márquez 2018). Odonyms and neotoponymies help us understand how the interaction of people with contemporary materiality produces diverse modes of assessment. Consequently, odonyms can also obliterate memories concerning the history of a place, not by naming a new urban area but by changing an existing name (Adam 2008; Guyot and Seethal 2007). In Canada, these questions may explore how neotoponymies obliterate or revive local Indigenous history. How do odonyms that reflect settler history appropriate Indigenous spaces and contribute to erasing the local past? These questions involve exploring the urban space as a place where diverse voices, such as those of exiles from other countries, seek representation and contest dominant narratives.

Using odonyms and public art, I consider these nuances and the social dynamics of inhabiting urban places, aiming to understand the practices of individuals and communities who comprise these urban spaces. Although fixed in materiality, the odonyms Salvador Allende and L’Arc should be perceived not as mere static things that represent the recent past or relate only to the past but as social devices for the future. It is as much a process of bringing back the past as it is connecting diverse layers of transnational forms of remembering. These exile materialities also open different but interrelated spaces as sites of dialogue and encounter (Fahlander 2007), symbolically reassembling a community in exile. Can these materialities assist in coping with the experience of exile? As Joan Simalchik indicated, the condition of exile faces geographical and temporary disruptions with people living both in the past and present: “The tension of maintaining a balance between shifting coordinates of time, place, and memory serves as a particularly demanding burden of exile” (Simalchik 2006, 96). Expanding from the examples presented in these photographs, other objects and places from Canadian cities invite us to connect with this burden and the personal experiences of confronting political violence. The odonyms Salvador Allende and the sculpture L’Arc create strategies for constructing an intercultural environment in the visual discourses they continually produce through their physicality and through the social practices they enable.

Due to the disruption brought by the COVID19 pandemic, I again walk through the streets of Toronto and Montreal, but this time my walk is virtual on Google Maps. No more bus stop conversations, no in-situ interviews—at least for a while. In my virtual exploration of the cities, Richard Sennett’s words echo loudly: “In the painting the foreigner is making of his or her life, large patches are over-painted in white” (Sennett 2011, 79). Perhaps, in some ineffable way, as testimonies of (up)rootedness, the modest and discreet artifacts in these photographs are brushstrokes of colour on that canvas.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

A first draft was presented in a session co-organized with Paulina Scheck at the 51st Annual Meeting of the Canadian Archaeological Association in Winnipeg, Canada. I am grateful to the Casa Salvador Allende of Toronto, Tiziana Gallo for her multiple proofreadings of the manuscript and the anonymous reviewers who took their time to read and give insightful comments.

Notes

-

[1]

To this date, fieldwork and interviews have focused on Toronto, Montreal, Laval, and Ottawa, with hopes to expand to other cities in the Maritimes and Western Canada.

-

[2]

In 1969, Canada signed the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol. In 1976, the new Immigration Act was the first Canadian immigration law to recognize the status of refugees.

-

[3]

In Canada, the Geographic Commission (Commission de géographie) created in 1912, was responsible for assigning toponymical designations within the province of Quebec. Since 1977, the Toponymy Commission of Quebec (Commission de toponymie du Québec) is the government agency responsible for the “inventory, processing, standardization, officialization, dissemination, and conservation of place names in Québec territory” (Adam 2008, 34) (my translation).

- [4]

- [5]

- [6]

- [7]

-

[8]

In 2011, 12,215 people in Quebec reported being of Chilean origin, concentrated mainly in the Montréal metropolitan region, 10 percent of which reside in the Laval administrative region (Gouvernement du Québec 2014).

-

[9]

Fictitious name. It has been changed for anonymity.

Bibliography

- Adam, Francine. 2008. “L’Autorité et l’autre, parcours toponymiques et méandres linguistiques au Québec.” L’Espace Politique 5(2): 31–39. https://doi.org/10.4000/espacepolitique.143.

- Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure. 2008. “Des territoires sans nom peuvent-ils être sans qualité ? Réflexions sur les modifications de la carte administrative chilienne.” L’Espace Politique 5(2): 112–132. https://doi.org/10.4000/espacepolitique.327.

- Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Azaryahu, Maoz. 1996. “The Power of Commemorative Street Names.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14(3): 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1068/d140311

- Badariotti, M. Dominique. 2002. “Les noms de rue en géographie. Plaidoyer pour une recherche sur les odonymes.” Annales de Géographie 111(625): 285–302. https://doi.org/10.3406/geo.2002.1658

- Bascuñán, Patricio D., and José M. Borgoño, eds. 2015. Chilenos en Toronto. Memorias del Exilio [Chileans in Toronto. Memories of Exile]. Toronto: Casa Salvador Allende.

- Bascuñán, Patricio D., and José M. Borgoño, eds. 2021. Chilenos en Toronto. Memorias del Post-exilio [Chileans in Toronto. Memories of Post-Exile]. Toronto: Casa Salvador Allende.

- Berg, Lawrence D., and Jani Vuolteenaho, eds. 2009. Critical Toponymies: The Contested Politics of Place Naming. Farnham, Burlington: Ashgate.

- Bouvier, Jean-Claude, and Jean-Marie Guillon, eds. 2001. La toponymie urbaine: significations et enjeux. Actes du colloque tenu à Aix-en-Provence, 11–12 décembre 1998. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Cáceres, Iván. 1992. “Arqueología, antropología y derechos humanos.” [Archaeology, Anthropology and Human Rights]. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 15: 15–18.

- Carrasco, Carlos, Kenneth Jensen, and Iván Cáceres. 2004. “Arqueología y Derechos Humanos. Aportes desde una ciencia social en la búsqueda de detenidos desaparecidos.” [Archaeology and Human Rights. Contributions from a social science in the search for detenidos desaparecidos]. In Actas del XVI Congreso de Arqueología Chilena, edited by Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, 665–673. Tomé: Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología.

- Casagranda, Mirko. 2013. “From Empire Avenue to Hiawatha Road: (Post)colonial Naming Practices in the Toronto Street Index.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Onomastics “Name and Naming” 2: 291–302. Retrieved from http://onomasticafelecan.ro/iconn2/proceedings/3_06_Casagranda_Mirko_ICONN_2.pdf.

- Da, Wei Wei. 2002. Chileans in Canada: Contexts of Departure and Arrival. Latin American Research Group, Toronto: York University.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1972. Capitalisme et schizophrénie. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

- Fahlander, Fredrik. 2007. “Third Space Encounters: Hybridity, Mimicry and Interstitial Practice.” In Encounters, Materialities, Confrontations: Archaeologies of Social Space and Interaction, edited by Per Cornell and Fredrik Fahlander, 15–41. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press.

- Fornazzari, Ximena. 2018. Desarraigo. El Golpe de Estado en Chile y los Laberintos del Exilio. Memorias [Uprooting. The Coup d’Etat in Chile and the Labyrinths of Exile. Memories]. Mississauga: Georgian Bay Books.

- Fuenzalida, Nicole. 2017. “Apuntes para una Arqueología de la Dictadura Chilena [Notes for an Archaeology of the Chilean Dictatorship].” Revista Chilena de Antropología 35: 131–147. https://doi.org/10.5354/rca.v0i35.46205

- Fuenzalida, Nicole, Natalia La Mura, Luis Irrazabal, and Camila González. 2020. “Capas de memorias e interpretación arqueológica de Nido 20. Un centro secreto de detención, tortura y exterminio” [Layers of memories and archaeological interpretation of Nido 20. A secret detention, torture and extermination center]. In Arqueología de la dictadura en Latinoamérica y Europa. Archaeology of Dictatorship in Latin America and Europe, edited by Bruno Rosignoli, Carlos Marín Suárez and Carlos Tejerizo-García, 156–170. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

- Gouvernement du Québec. 2014. Portrait statistique de la population d’origine ethnique chilienne au Québec en 2011. Québec: Direction de la recherche et de l’analyse prospective. Ministère de l’Immigration, de la Diversité et de l’Inclusion.

- Guyot, Sylvain, and Cecil Seethal. 2007. “Identity of Place, Places of Identities: Change of Place Names in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” South African Geographical Journal 89(1): 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2007.9713873.

- Herbert, James. 2015. Brushstroke and Emergence: Courbet, Impressionism, Picasso. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Huyssen, Andreas. 2003. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Landolt, Patricia, and Luin Goldring. 2006. “Activist Dialogues and the Production of Refugee Political Transnationalism: Chileans, Colombians and Non-Migrant Civil Society in Canada.” 2nd International Colloquium of the International Network on Migration and Development, Cocoyoc, Mexico.

- Márquez, Francisca. 2018. “Tropiezos y demoras. Monumentos en la ciudad [Stumbles and delays. Monuments in the city].” In Caminando. Prácticas, Corporalidades y Afectos en la Ciudad, edited by Martín Tironi and Gerardo Mora, 59–78. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

- Meade, Teresa. 2004. “Holding the Junta Accountable. Chile’s “Sitios de Memoria” and the History of Torture, Disappearance, and Death.” In Memory and the Impact of Political Transformation in Public Space, edited by Daniel J. Walkowitz and Lisa Maya Knauer, 191–209. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mitchell, Don. 2003. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: Guilford Press.

- Montes, Rocío. 2018. “La detención de Augusto Pinochet: 20 años del caso que transformó la justicia internacional” [The arrest of Augusto Pinochet: 20 years of the case that transformed the international justice system]. El País, 16 October. https://elpais.com/internacional/2018/10/16/america/1539652824_848459.html (accessed 30 November 2020).

- Moretti, Cristina. 2017. “Walking.” In A Different Kind of Ethnography. Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies, edited by Denielle Elliott and Dara Culhane, 91–111. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2009. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15(1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.01527.x

- Obregón Iturra, Jimena, and Jorge Muñoz, eds. 2015. Le 11 septembre chilien. Le coup d’état à l’épreuve du temps. 1973–2013. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Peddie, Francis. 2012. Young, Well-Educated and Adaptable People: Chilean Exiles, Identity and Daily Life in Canada, 1973 to the Present Day. PhD dissertation, York University.

- Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Los Angeles, London: SAGE.

- Robb, John. 2020. “Material Time.” In The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, edited by Ivan Gaskell and Sarah Anne Carter, 123–139. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sennett, Richard. 2011. The Foreigner: Two Essays on Exile. London: Notting Hill Editions.

- Simalchik, Joan. 2006. “The Material Culture of Chilean Exile: A Transnational Dialogue.” Refuge 23(2): 95–105. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.21358

- Simmons, Alan B. 1993. “Latin American Migration to Canada: New Linkages in the Hemispheric Migration and Refugee Flow System.” International Journal 48(2): 282–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070209304800205

- Vilches, Flora. 2011. “From Nitrate Town to Internment Camp: The Cultural Biography of Chacabuco, Northern Chile.” Journal of Material Culture 16(3): 241–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183511412879

- Yi’En, Cheng. 2014. “Telling Stories of the City: Walking Ethnography, Affective Materialities, and Mobile Encounters.” Space and Culture 17(3): 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331213499468.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12