Corps de l’article

I missed going to art exhibitions during the early phases of the pandemic. I’m sure artists and curators felt the lack more acutely, but brushing up against art in the company of strangers excites and inspires me, and I lost that source of pleasure for some time. Galleries and museums put resources into online exhibitions, and art creators and appreciators found their own ways to contribute through digital activities like re-enacting famous artworks with household items as props in the #betweenartandquarantine trend (Barajas 2020; Compton 2020). But art is not the same when set in the grey screen instead of the white cube (see O’Doherty 1986). I was happy, then, to receive an email from the Hermes Art Gallery announcing an exhibition running from February 20 to March 28, 2021 called ESCAPE / The Great Indoors, curated by Liuba González de Armas, Halifax’s Young Curator at the time.[1] In this piece, I explore the exhibition in its pandemic-era context through interviews with the curator and one of the artists, its written documentation

Hermes is a cooperatively run gallery space around the corner from where I live in the North End of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Housed in a small building that could have originally been a store or a home, it is about the size of two large living rooms, though painted the traditional art-gallery flat white. It is the white cube domesticated, and its small scale is the reason why ESCAPE could take place at all. Mentored by the directors of three university art galleries, González de Armas was supposed to do curatorial work in each of those spaces during her year as Halifax’s Young Curator, but the pandemic shut universities down. Hermes emerged as an alternative exhibition space, a small institution not bound by the same COVID-19 restrictions as the campuses. Hermes could comply with provincial public health directives and still exhibit.

González de Armas put the exhibition together quickly. As an emerging curator, she sought emerging artists, keeping an eye out for kindred queer or racialized artists. She assembled four “cozy, bright, and colourful” works that explore and “seek to re-enchant” domestic space.

Anna-Lisa Shandro’s textile installation, Back to your roots, spreads like an indoor bower over one side of the gallery. Embroidered and knitted leaves and vines and flowers climb up hanging handmade blankets and dangle from the ceiling. The installation looks like a chunky woolen Andy Goldsworthy piece, but its arrangement is less precise, its elements less precarious. Shandro tells me they are all made from remnants, thrifted, found, or gifted; “they really are fallen leaves from another project.” As handicrafts made from scraps, they are domestic in form but also in process: Shandro made them at home while watching television or listening to a podcast, during a time when she was working eight hours a day to make medical gear. They were a way to “come back down to my roots, spend some time with myself.” Gradually, she gathered a textile forest around herself:

I just kind of knit nonstop for a really long time and... it kind of worked, I just feel more grounded and better and I feel like I’m at my roots and this is my little garden shrine thing that makes me feel at home and comfy and like myself.

Shandro plans to make it her living room decor when she moves house. This appeals to me too, a den in the woods made into a blanket fort. I would settle down inside it and fondle its fuzzy forms, daydreaming with my fingers.

Figure 1

Anna-Lisa Shandro, Back to your roots, 2020–2021. Large assortment of different sized textile pieces, integrated textile foliage, pillows, and a simple wood kitchen chair.

Figures 2-4

Anna-Lisa Shandro, Back to your roots, 2020–2021. Details.

ME MANGAV TUT feels like a hug for the feet. It is a long-pile woolen rug featuring a doodled kind of a person with eyes closed and arms outstretched, reaching up to offer or embrace a heart. I imagine waking up in bed and, once I had the courage to fling back the blankets, the first thing my feet would touch is this rug, and I would feel held. Here, the rug is not on the floor, and perhaps it never will be anywhere. It’s on the back wall of the gallery, but its vivid yarn pulls the viewer’s gaze in, bringing the wall forward. González de Armas says this is a “tender piece,” one that “speaks of this experience of seeking warmth or comfort, or a return to a place of feeling protected.” The title means “I love you” in the Romani language of Pellerin’s family. The rug is a meditative, meticulous labour of love, each fibre tied precisely to the grid of its canvas, but the result is soft and fluid. “Every time Fern installs it,” González de Armas says, “they fluff it a little bit. … Each time the lines shift just a tiny bit.” The whole piece is easily shifted, too; you can take a small rug with you when you move. Wherever my toes sink into bright fluffy wool, that’s my home.

Figure 5

Fern Pellerin, ME MANGAV TUT, 2020; wool yarn, rug canvas, cotton thread; 29” x 59”.

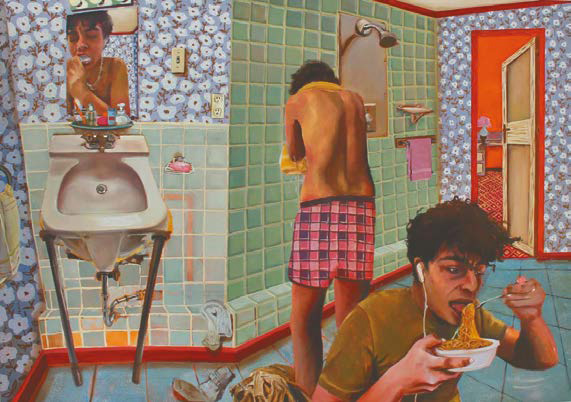

The Bathroom is the most imposing work, an oil painting measuring 60” x 84”. Although it is just one canvas, it feels like a triptych, as it gives three views of the artist, Kayza DeGraff-Ford. They are there in the mirror, brushing their teeth: the washbasin is angled to face the viewer, but it is DeGraff-Ford’s face reflected, eyes closed in concentration. They are also standing between the basin and the shower, washing or maybe drying their face, a yellow towel around their neck, wearing pink checkered boxer shorts, with their bare back turned toward us. And they are sitting down on the tiled bathroom floor, shoveling forkfuls of ramen into their mouth, gazing downwards, absorbed in the sounds channeled through their earbuds. The bathroom walls are mismatched—green glazed tiles and blue and white floral wallpaper—and the washbasin and plumbing reflect light along their cool curves. I absorb the details: the hem of the towel, the lather on the soap, the shadow of the light switch, the dirty sloughed-off socks.

The perspective seems askew, a wide angle in a tight space, though it could just be a funny Halifax bathroom in an old house. A door to the right opens onto a room with red walls and a carpet. González de Armas tells me that the bathroom is actually a composite of fictional and real spaces. The washbasin is a public one at NSCAD University, which all the art students recognize, and the shower is coin-operated. She thinks the painting speaks to “the social reproduction of labour, the kind of work that we do that often gets reframed as self-care when it’s really work that we do in order to be able to do work that is economically productive for other people.” In this sense, The Bathroom is a companion piece to Back to your roots, which relates to the “creative impulse, things that we do almost purely for pleasure.”

Figure 6

Kayza DeGraff-Ford, The Bathroom, 2019. Oil on canvas, 60” x 84”.

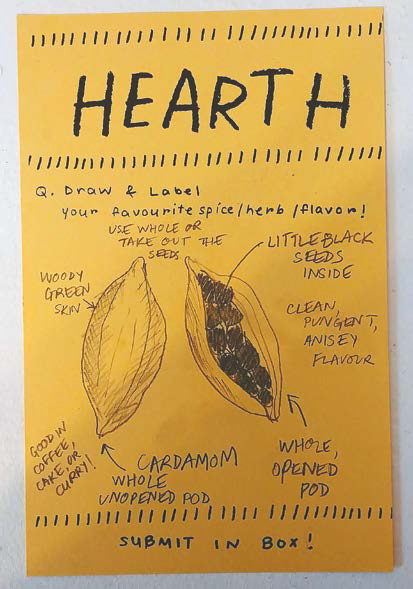

Tee Kundu’s “socially-sourced” piece, Hearth, is the kitchen of this artful home. It is lodged in an alcove separated from the main room of the gallery, so it has its own three walls and a kind of built-in counter. On the counter sits a tub of pencils, a white cardboard filing box, and a stack of yellow printed sheets propped in a book stand. The sheets are printed with different instructions:

Q. Draw & label your favourite fruit!

Q. Draw & label your favourite spice/herb/flavor!

Q. Share the easiest recipe you know!

Q. What have you been eating lately?

Takeout_____________

Home-Cooked___________

Snacks!____________

Q. Top 5 takeout spots in town?

A sheet of the same kind of paper pinned on the wall has a typed artist’s statement, in which Kundu reveals some of their edible sources of comfort, and asks, “What have you been eating? How have you been sustaining yourself? Which recipes would you like to share? What is stocked in your pantry? Where do you find nourishment?” González de Armas explained that she wanted something interactive to reward people for leaving their homes, “to offer something that they wouldn’t necessarily get at home, which is a conversation with strangers. Even if only through traces, right?” The plan is to turn the contributions into an as-yet-undefined new piece of work, but for the time being, some of them are pinned on ten hooks on the wall opposite the counter. One person’s top five takeout spots are all coffee shops. Another’s favourite fruit is a mangosteen. Someone has been eating takeout poutine, homemade breakfast burgers, and rice pudding snacks. I take a photo of an intriguing “easiest recipe” for tomato and ginger salad (which I have not made yet). One favourite spice/herb/flavour is basil, another is salt. I draw two cardamom pods, labelling one whole and unopened, and the other whole and opened to reveal the sticky black seeds nestled inside. As is often the case, kitchen conversation makes Hearth the centre of domestic sociability.

Figures 7, 8

Tee Kundu, Hearth, 2021. Socially sourced and participatory installation.

Figure 9

ESCAPE / The Great Indoors represents an artistic form of what João Biehl and Federico Neiburg call house-ing, “the sensorial process by which peoples and houses co-constitute one another” (2021, 540), and a potential contribution to oikography, “an ethnographic approach that deconstructs ideological premises and statistical assumptions about domiciles and traces the plasticity and relationality of the house across space-times” (ibid.). The artworks of ESCAPE mirror a home: living room (Shandro), bedroom (Pellerin), bathroom (DeGraff-Ford), kitchen (Kundu). The bedroom is even at the back of the gallery and the kitchen off to one side. ESCAPE invites us to reflect on how well so many of us have come to know the details of our own domestic spaces since the pandemic started—perhaps so well we want to escape from them, not just escape into them. On 3 April 2020, as COVID-19 first reached Nova Scotia, then premier Stephen MacNeil exhorted us to “stay the blazes home,” ignoring that some people’s homes are mined with physical or mental dangers, while other people do not have a home at all. In other countries, people were being similarly scolded. Memes joking about staying at home to save the world multiplied, and celebrities tweeted and tiktokked about how delightful it was to do so. “The love of being in one’s home is being reframed as civic virtue: or, to put it another way, the class privilege of home-love is being reframed as civic virtue,” as Jilly Boyce Kay (2020, 885) argued in her critique of the “resurgence of mystificatory images of the heteronormative private household” (ibid., 884) that the pandemic triggered.

One could interpret the coziness of ESCAPE / The Great Indoors as part of this mystification, a panacea for the agoraphobic times of the pandemic. González de Armas’ curator’s statement says, “ESCAPE explores imaginative tactics to transcend domestic confinement, reframing our homes as sites of hidden wonder, both rich in spontaneity and ripe with possibility.” The exhibition, she acknowledged in interview, was “self-consciously lighthearted” with its intention “to celebrate the ways in which we have, after a year of pandemic, found ways to make the experience of being confined in our homes, for the most part, bearable.” ESCAPE did not explicitly engage with critical issues of the pandemic, partly because it had to be mounted so rapidly, and partly because González de Armas was already working on another exhibition that did: Tactics for Staying Home in Uncertain Times, at Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery.[2] Though it is playful, I do not read ESCAPE as apolitical. The way we play can be political too. Besides, I pick up on threads of anxiety and connection running through the exhibition, which weave into a soft politics that alerts us to “how homes are not isolated units, but related and relational, integral to shifting forms of governance” (Biehl and Neiburg 2021, 540).

First, there is ambivalence in these evocations of domesticity, however enchanting and appealing they are. Although DeGraff-Ford painted The Bathroom before the pandemic, its comic/unsettling scenes speak to current concerns of cleanliness and self-isolation. Why is the artist not eating their ramen in the warmer, dryer room we catch a glimpse of through the door? It seems troubling to eat in a bathroom, where smells of shampoo and poo and mildew might linger. But a bathroom can be a refuge, too, the one place you can be alone to eat instant ramen and listen to cheesy music. And the bathroom is clean, and bears repeated cleaning: you can bleach the high-touch surfaces and know that no coronavirus fomite is going to make it from tap to fork to face. To me, the questions of am I clean enough, can I be clean enough, can I avoid contamination echo around The Bathroom—a hygiene theatre of one’s own. In Back to your roots, I think the anxiety is in the tangle: What if my roots trip me up and trap me again? What if I lose my way in the interior forest? And then ME MANGAV TUT offers reassurance, a talisman to make sure I get out of bed on the right side tomorrow morning.

Second, ESCAPE evokes connection. This comes across most explicitly in Hearth, which references how the pandemic disrupted food preparation and commensality. Food shopping had to be strategically planned, and many people, especially young people who returned to live with parents or whose roommates departed, changed their eating habits. “I’ve been home for a while. I miss my partner’s chicken soup, but I’ve been trying out avocado recipes, and my dad brings me coffee sometimes,” writes Kundu in their artist’s statement. “Things are a bit complicated right now, but there is still a lot to be thankful for.” Kundu’s yellow paper forms are a device for connecting and sharing food again, though they also remind me of the shopping lists my partner and I carefully make to minimize expeditions to grocery stores. The forms and the lists connect indoors to outdoors, connect the hungry body to supply chain systems at risk of disruption, connect your recipe for tomato and ginger salad to my taste for cardamom.

More broadly, ESCAPE is relational because it is implicated in the contemporary search for and narration of the self. The selves expressed in the artworks of ESCAPE are singular, and thus universal: as Francisco Cruces points out, “we all identify with the stories of the self, because each one of us is also another” (2016, 20). The small scale of the Hermes Gallery is the perfect stage for telling artful stories of intimate, domestic life, and the telling of stories calls into being a public who will listen (Warner 2005). Cruces names the “growing social pressure to disclose intimate life” as extimacy (2016, 9). Among the risks of this pressure are the commodification or mystification of images of the intimate and the domestic (see Kay 2020). However, extimacy also disrupts the implicit hierarchy that values public affairs above private life and blurs the boundaries between the two (Cruces 2016). The artworks by DeGraff-Ford, Kundu, Pellerin, andShandro, set in context and conversation by González de Armas, playfully question assumptions about the composition, permanence, scope, and circumstances of home and household, participating in an artistic oikography of the pandemic era. ESCAPE / The Great Indoors folds back the screen around private space to invite the public in to listen to the artists’ stories and summon up their own.

Parties annexes

Notes

Bibliography

- Barajas, Joshua. 2020. “Famous Paintings Come to Life in These Quarantine Works of Art.” PBS Newshour, 15 April. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/in-these-quarantine-tableaus-household-items-turn-into-art-history-props (accessed 19 April 2022).

- Biehl, João, and Federico Neiburg. 2021. “Oikography: Ethnographies of House-ing in Critical Times.” Cultural Anthropology 36 (4): 539–547. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca36.4.01.

- Compton, Natalie B. 2020. “People are Re-creating Famous Artworks With Their Pets and Whatever Else is Lying Around.” The Washington Post, 3 April. https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2020/04/03/people-are-re-creating-famous-artworks-with-their-pets-whatever-else-is-lying-around/ (accessed 19 April 2022).

- Cruces, Francisco. 2016. “Personal is Metropolitan: Narratives of Self and the Poetics of the Intimate Sphere.” Urbanities 6 (1): 8–24.

- Kay, Jilly Boyce. 2020. ““Stay the Fuck at Home!”: Feminism, Family and the Private Home in a Time of Coronavirus.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (6): 883–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1765293.

- O’Doherty, Brian. 1986. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. San Francisco: Lapis Press.

- Warner, Michael. 2005. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Anna-Lisa Shandro, Back to your roots, 2020–2021. Details.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Tee Kundu, Hearth, 2021. Socially sourced and participatory installation.

Figure 9