Abstracts

Abstract

Thompson, Manitoba, was established in the late 1950s as both a mining community and a service centre for the north. A collaborative project between provincial officials and the International Nickel Company of Canada (INCO), Thompson borrowed heavily from post–Second World War trends in urban and suburban planning and development while grafting these ideas onto the realities of the boreal forest. At the same time, this orderly design was heavily influenced by the area’s First Nations and the newly arrived inhabitants who came from across Canada and much of the world. While not always a seamless or harmonious process, the interactions and agency of these various players shaped Thompson as a centre for mining and services, as well as a diverse and complex community bridging southern trends and northern realities.

Résumé

La ville de Thompson au Manitoba a été fondée vers la fin des années 1950 à la fois en tant que communauté minière et comme centre de services pour le nord de la province. Ce projet entrepris, en collaboration, par les instances gouvernementales et l’International Nickel Company of Canada (INCO) a emprunté fortement aux tendances d’urbanisme des villes et des banlieues de l’après-guerre tout en les adaptant aux réalités de la forêt boréale. Simultanément, cette conception systématisée a été influencée de façon importante par les premières nations et par les habitants arrivant de partout au Canada et dans le monde entier. Bien que ce processus n’ait pas été toujours aisé et harmonieux, les échanges et les actions des divers intervenants ont façonné la ville de façon à faire de Thompson, non seulement un centre minier et de service, mais aussi une communauté diversifiée et complexe alliant les tendances du sud aux réalités du nord.

Article body

The discovery of nickel deposits in early 1956 in the vicinity of Mystery and Moak Lakes in Northern Manitoba led to the opening of the area for major industrial exploitation. The development of mining and hydroelectricity paved the way for what would become the province’s third-largest urban area. Named for the chair of International Nickel Company of Canada’s (Inco) incumbent chair, Thompson, Manitoba was, as Robert Robson argued, part of a continuous line of resource extraction communities that crossed the northern reaches of the province. As Robson pointed out, however, the establishment of Thompson differed substantially from earlier resource towns, which had been essentially the sole concern of the various mining interests or companies involved. By the 1950s provinces like Manitoba had been increasingly involved in co-operating and even dictating the terms of the establishment of these resource towns, providing them with a vast array of services that distinguished them from the earlier, far more ramshackle communities that had characterized resource extraction before the 1930s.[2]

Tied as they were to broader trends in the design and social realities of postwar Canadian urban development, the government and corporate planners may have perceived the task of establishing a city in the north as essentially starting from scratch. However, they were building a city on traditional Indigenous territory that would lead to the exploitation of local resources and the marginalization of local peoples. Similarly, however much government and industry may have intended to impose their stamp upon the emerging city, in the end the needs, wants, and expectations of the inhabitants who flocked to the new townsite substantially modified these initial plans. The resulting city was therefore born out of complex, fractious, and dynamic interplays between influences and players that created a mid-twentieth-century urban experiment in the midst of the boreal forest.[3]

The history of mining and mining exploration in Canada is littered with examples of communities that exploited the mineral wealth. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century the process was often at best barely controlled chaos, and while some communities emerged slowly, many were boomtowns that grew up almost overnight. The discovery of gold in the Klondike in 1896 led to a stampede involving tens of thousands of would-be gold prospectors who headed toward the remote region of what became Canada’s Yukon Territory to stake claims. Entrepreneurs like Joseph Ladue staked claims on the strategic junction of the Yukon and Klondike Rivers to establish a sawmill and townsite for Dawson City that quickly became the largest city west of Winnipeg. While popular works of history by Pierre Berton have immortalized that chaos of what some called “the Paris of the North,” work by Charlene Porsild has done more to illuminate the social conditions of this blossoming boomtown and its environs.[4] Similarly, the discovery of silver deposits in northeastern Ontario in the first decade of the twentieth century led to the nearly overnight birth of the town of Cobalt. As work by Douglas Baldwin and David Duke has illustrated, the complete lack of imposed order made Cobalt the site of severe environmental degradation, which resulted in ecological collapse and the disastrous outbreaks of disease. The attempts by Cobalt’s nascent municipal council to combat the worst of these excesses often ran afoul of mining interests and rendered it frequently helpless in safeguarding the health and well-being of the population during the height of the short-lived boom.[5] In the context of Depression-era Manitoba, communities like the gold-mining settlement of Herb Lake emerged almost exclusively from the efforts of miners of modest means, with little or no government intervention or oversight.[6]

The “boom” that centred on Thompson did not replicate the exponential and disordered growth of earlier towns. In relatively sharp contrast to earlier centres, the discovery of nickel led to a series of negotiations between Inco and the government of Manitoba. The two bodies hammered out an agreement whereby the town that would house the employees of the new mine would be free of direct company control and therefore built as a service centre for Northern Manitoba.[7] While the insistence of the government in having a hand in establishing new resource towns was a comparatively new development, so too was the increasing tendency for Inco and similar companies to create what has been termed “an open town.” Such collaborations permitted private landownership and development, though these were unavoidably tied to the well-being of Inco’s fortunes in any particular region.[8]

This new development led to a stampede of those seeking employment into the region in early 1958. Some 750 workers had to wait in The Pas before enough trains could be found to take them to Thompson, where they were initially housed in the burgeoning campsite near the planned townsite.[9] The transformation was abrupt and stunningly fast. Until the mid-1950s the site on which Thompson would arise had been within the traditional territory of the people of the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation at Nelson House. It had been primarily the site of traplines, with few intrusions of outsiders. Before 1956 the provincial government had occasionally hired local First Nations people from surrounding communities to work as part of survey crews. As one man remembered,

We were working with the Manitoba government surveys, me and my father, my uncle, [and] two of my cousins. I don’t know how many years we did that but every winter we would leave Norway House in January and lived out in the bush until March, cutting survey lines. And I can remember one year we were out camped by Moak Lake … that was before nickel was discovered. The next year we came [and] already they were hauling in freight from Thicket Portage by the tractor train. And then after that I worked on laying the railroad from the main line going to Churchill into Thompson.[10]

From the beginning there was a determination that this new city would be “a bright new star in Manitoba’s Northern Development.”[11] In a far cry from the haphazard development of earlier mining boomtowns, starting in 1957 Thompson was carefully planned by private firms hired by Inco in the newly minted Mystery Lake Local Government District. Provision was also made for water mains, a pumping station, and treatment centre, as well as for sewers and waste disposal to comply with the Provincial Health Act. Inco also provided for the building of schools, a hospital, and municipal buildings. The city was surveyed and laid out in a pattern that mirrored contemporary developments across southern Canada. These plans reflected the use and pre-eminence of the automobile with wide thoroughfares, winding residential streets, and a clear demarcation of residential, commercial, and industrial activities. This focus drew much from postwar suburban developments across North America.[12] Although many harboured great hopes for the new northern metropolis, the fact remained that while it had gained between 5,000 and 6,000 inhabitants by 1961, and projections suggested a rise to 17,500 by 1966, others worried that its population might stagnate at around 12,000 to 13,000. However, more confident promoters felt that with the proliferation of the automobile Thompson would emulate cities from the southerly, spawning suburban developments. Indeed, it was projected that “small communities … will inevitabl[y] grow in the surrounding district.” Countering concerns that such peripheral development would siphon off important property tax revenue from Thompson itself, it was still argued that “the central business district will nevertheless be their supply centre.”[13]

While the “suburban” developments did not materialize to the extent predicted, surrounded as the community was by seemingly endless boreal forest, dotted with lakes and crisscrossed by rivers and their tributaries, Thompson was centred in what many thought of as a hunter or recreational playground. (This did, however, come at the expense of local First Nations trappers, whose traditional traplines were displaced by the emergence of the townsite and its related developments). Most prominently, just south of the townsite was Paint Lake, which was set aside by Manitoba’s Department of Natural Resources as a recreation area for Thompson residents. In 1961 building lots were surveyed, which could be leased for the construction of summer cottages or cabins.[14]

While the plans were carefully outlined for Thompson and Paint Lake, implementation did not immediately translate into a fully functional urban environment. Nor did the process occur without hiccups. Inco’s initial campsite was exclusively male, and men also dominated the emerging townsite for the many months. The resident administrator zealously removed women who attempted to enter the camp, and even when families began to arrive in Thompson proper he met all incoming women “to check their credentials” and removed any women he deemed to be of questionable morality. Unlike developments further south, the gender imbalance was acute. Even at the end of 1959 the number women in the community remained well below fifty, and concerns about their safety were paramount in the minds of local planners. Any whiff of scandal could have damaged the emerging town’s plan to attract more nuclear families.[15]

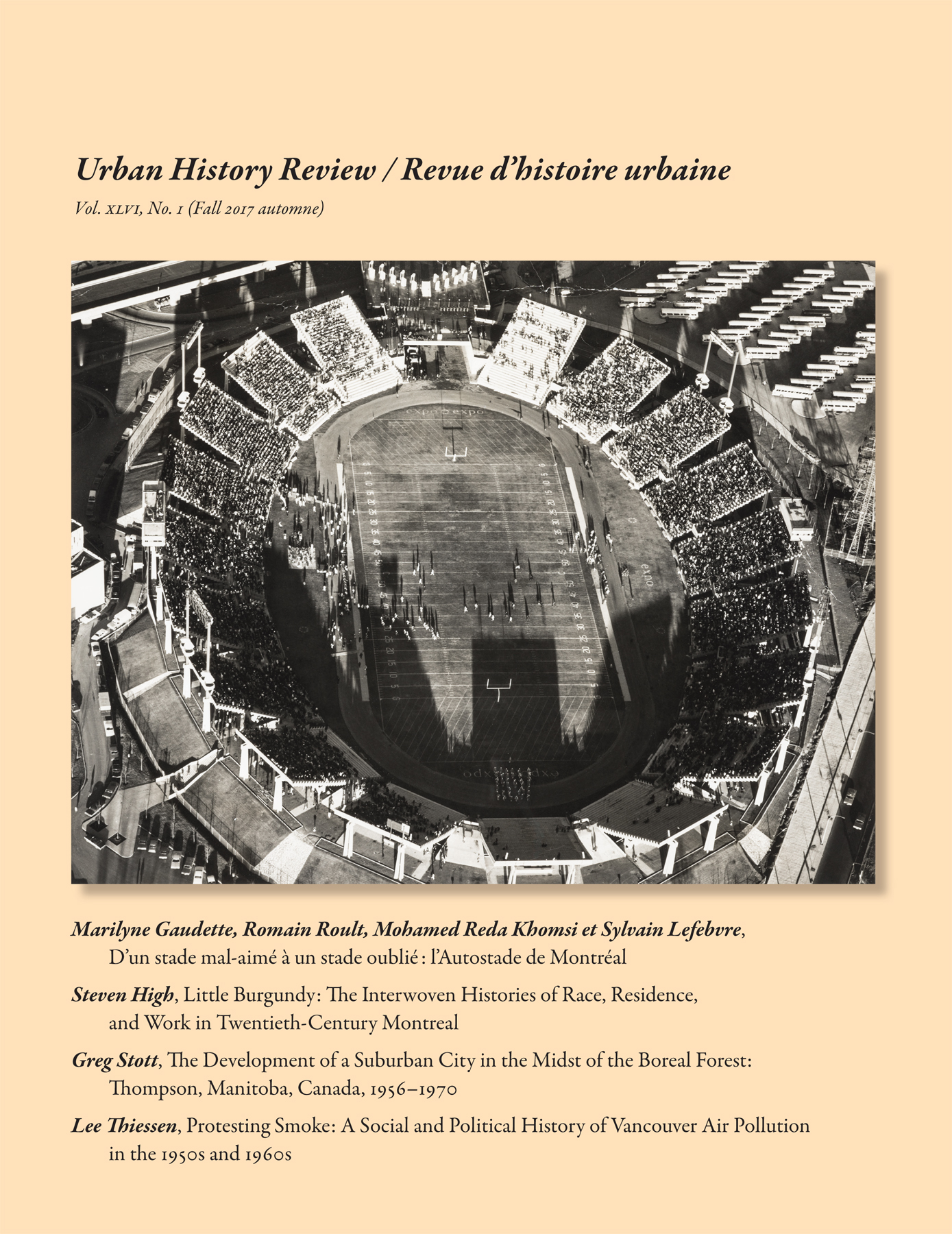

Figure 1

A change in government in June 1958, and differences of opinion between the incumbent administrator and one of the town’s planners made for further setbacks. Shortly after it was announced that some 12 per cent of the planned 200 housing units would be ready to welcome the first families into town, Inco officials voiced the opinion that this goal would be impossible to meet. Whatever the state of readiness, the first non-Aboriginal women and children began to arrive late that year by the newly completed spur of the Hudson Bay Railway. Many of the new arrivals would have to take up temporary residence with multiple families sharing limited quarters, as workers attempted to complete enough housing stock to accommodate everyone.[16]

The housing reflected similar designs proliferating in the south. However, the realities of melting permafrost and unpaved roadways often created difficulties for the first families taking up residence in the newly completed Juniper neighbourhood. Some arrived to find their houses were not yet habitable, while other householders were left waiting for shipments of their belongings and often had to make do with camping equipment and jerry-rigged furniture. Nonetheless, there was a concerted effort to ensure that other basic services were in place to make the transition as smooth as possible. By the end of 1959 the first of four planned schools was opened, with nineteen students and one teacher. (By the time the first permanent school opened in September 1959, the school-aged population had risen to 150). Bus service was quickly established to link the emerging town with the main Inco plant. Residents were served by two banks, a tiny hospital, and the townsite’s own Hudson’s Bay Store—where “shopping is a pleasure … and prices compare favourably with Winnipeg”—opened in February 1959. One Inco booster claimed that with a rail link and proposed airport, “Thompson is swiftly shedding the remoteness in which it was wrapped during the preliminary stages of development.”[17]

Figure 2

The Thompson Inn in 1958. This establishment was the first commercial hotel and a favourite gathering place for locals and miners.

Whatever the boasts of local planners, some residents, particularly some of the newly arrived women, found these conveniences did little to alleviate feelings of isolation, and a number of suicides were the result.[18] As one resident explained, “I can remember being down at the grocery store and seeing women shopping; and I’m sure their mind wasn’t in Thompson. They were isolated and [a] lot of them were homesick, too.” Some of the men brought in as managers of businesses found that their wives were miserable in the new town, and “so in the end they had to move to keep peace in the family.”[19]

Those who stayed developed coping mechanisms and adapted. Many, like school-teacher Grace Bindle, intended to be in Thompson only a short while. Bindle came from The Pas to spend part of her summer with an old acquaintance. However, matters conspired so that she courted and married the manager of the local Thompson Inn and therefore made Thompson her home, although it was far from family and most friends. Bindle explained, “Once you were here for a little bit, everyone was your friend. I could go downtown shopping and it would take me hours and hours, because you meet and you visit and visit and visit. And everybody was stopping and welcoming everybody else, because they remembered [the isolation and loneliness they had experienced] … when they came.”[20]

While companies redoubled their efforts to meet the demands for housing, after the initial influx the backlog did not abate. Families that opted to stay had to “put in” for a house and sometimes had to wait for months before contractors could get it built. In 1961 Inco employee Axel Lindquist and his wife, Doreen, put in for a house that took several months to build next to a swamp that separated it from the centre of the town. Once the concrete slab was laid, a construction crew came in to put up the walls and another company had the structure roofed. Given the house’s location and the local topography Doreen Lindquist explained, “We needed a sidewalk so that we wouldn’t track in all of the mud. That was kind of annoying for awhile, because everyone who lived on the other side of the treeline from us would use the walkway and clean their boots off, and pretty soon there were bicycles, and the final straw was when a motorcycle went roaring past the kitchen window.”[21]

Thompson’s layout mimicked the urban designs of neighbourhoods like Winnipeg’s Windsor Park, where primacy of the automobile was a given. In the instance of Thompson, however, for the first years this planning neglected the reality that, like Kitimat on the Pacific coast, Thompson was not yet tied into the highway network connecting it to other centres.[22] Any cars that came into the community had to be transported from The Pas by train. Indeed, it would not be until March 1965 that the people of Thompson would be able to drive to The Pas and points beyond.[23] The lack of road access was mitigated by the railway link and the establishment of regular air travel, so that by December 1961 one commentator noted,

Thompson will be a partly deserted town during the Christmas season if bookings on airlines, trains and other means of transportation across the country and to Europe are any indication of the number of people that are leaving the town for Christmas…. Transair reports heavy bookings for all of next week. They may have to put on two planes a day to handle the holiday crowd…. Many people are leaving Thompson for only a few days. Some are making it the occasion of a visit home to the old country. Some are leaving for good.[24]

Beyond mere transportation grids, the early 1960s were marked by a series of new innovations that lessened Thompson’s overall isolation and increased it linkages to the world beyond. The installation of telephone service for 200 subscribers in June 1960 created excitement. The community’s two weekly newspapers also kept the local population abreast of other developments. In what the Thompson Citizen titled “Progress Notes,” readers learned, “Soil tearing and site layout is progressing for fifteen new apartment blocks. These will represent a project of the Kent Development Co. and will be situated along Cree Road. Progression on this enterprise has been termed satisfactory.”[25]

The pervasive emphasis on “modern” permeated most media discussion in both the Thompson Citizen and the Nickel Belt News. The opening of a cinema in June 1960, lauded as “Manitoba’s most modern theatre,” led to the boast that “Thompson is really beginning to roll as the most up-and-coming community in Manitoba.”[26] If there was any doubt about Thompson’s progress, the implementation of a program to pave streets in the townsite further emphasized what many saw as its progress.[27] The opening of a franchise of the A&W fast food restaurant in the spring of 1961, replete with a genuine “A&W cook from Winnipeg” and carhops, reinforced the image of Thompson as a “modern” city, despite its location on the fringes of what many might have viewed as civilization.[28] While the introduction of the fast food outlet was part of modernization, so too was news that Norrec Billiards would be opening their “modern” facility, for which “there is nothing in Canada comparable.” At the same time the provisioning of natural gas to the housing stock led the local gas company to bring in a Vancouver-based entrepreneur “to demonstrate to the ladies of Thompson the advantages of gas cooking,” which many residents who came from rural regions had never experienced. While Thompson got used to such new amenities, a group of enterprising residents worked to ensure that Thompsonites enjoyed the benefits of free television. They began by corresponding with television stations in Eastern Canada to learn how to develop a community-based and -financed station of their own.[29] When closed-circuit television service finally arrived in early December 1961, subscribers were provided with programs from other parts of Canada, the United States, and even Great Britain, albeit on a more limited scale than their contemporaries further south.[30]

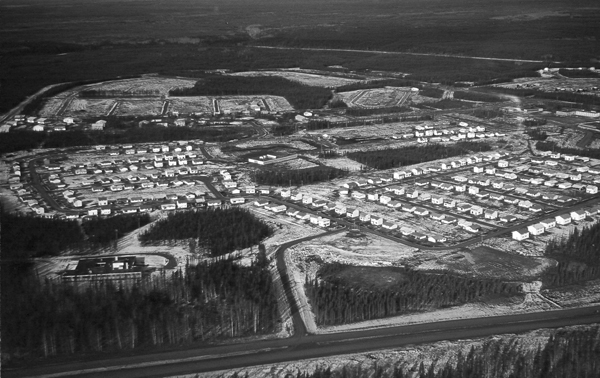

Figure 3

The Juniper subdivision under construction, 1958.

The preoccupation with “modernity” did not dissipate quickly. In the summer of 1961 the Thompson Inn opened its “modern” cocktail lounge, which was described by manger Otto Bindle as “among the most up-to-date in Manitoba, and those who have seen the new local lounge agree.”[31] However much they may have lauded the opening of the sophisticated drinking establishment, the opening of the Thompson Plaza Shopping Centre late in 1961 was viewed by many as one of the community’s early crowning achievements. The initiative of the Winnipeg-based Capital Developments, the plaza had its own unique set of obstacles to overcome, particularly in the “decaying permafrost,” which forced engineers to develop hydraulic lifts to counter dramatic shifting and settling of the building. Opening festivities included formal presentations, tours, and a dance for most of the 6,000 residents of Thompson who, until recently, “had almost no stores at all.”[32]

Since the end of the nineteenth century shopping had been increasingly characterized as a predominantly “feminine” activity, with stores and advertising agencies increasingly tailoring their advertising and services to women shoppers.[33] However, while the creation of a shopping plaza in Thompson mirrored similar commercial enterprises across North America, the peculiar nature of resource extraction, dominated as it was by single men, tempered this continental trend. As the Nickel Belt News explained,

A customer leaves the icy blasts of Thompson’s streets and enters the shopping centre at any one of the three canopied entrances, or at the 40-foot-wide main entrance. He can leave his coat in a locker, and plan to spend the day. He can move from the Bata Shoe store to the Shop-Easy supermarket; leave orders at Eaton’s or Simpson-Sears Mall Order Offices; visit Woolworth’s and Cochrane-Dunlop hardware. He can choose among the Toronto-Dominion Bank, Bank of Montreal and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. He can pay his bill at Thompson Gas Co. Ltd., stop in at the Manitoba Liquor Commission outlet and buy a present at McKinnon Jewellers.

His hair will be cut by F. Bakos, barber; and his vacation planned by Byron Watt Travel Agency. He can meet his wife at the Chez Continental Beauty Parlor or have a look at the closed circuit T.V. studio run by Canadian engineering surveys. He can pick up his suit at Modern Cleaners, fill a prescription at F. Soble, Druggist, and buy a pie from Michelle’s Bakery. Before long, the range will be increased by sixteen more commercial concerns.[34]

The opening of the plaza and the establishment of a local chamber of commerce was meant to signal that Thompson was “open for business.”[35] However, there were local residents and budding entrepreneurs who felt that Inco and the management of the Thompson Plaza were colluding to block the exercise of free enterprise. Inco employee Joe Borowski sold goods to men living in the neighbouring camp and indicated that he planned to establish “a general import store,” which included jewellery, but his attempts to secure rental space had been thwarted. When Borowski finally secured an agreement to sublet a small space in the Thompson Plaza from an existing tenant, the plaza’s management stepped in to kill the deal. Eventually it was agreed that a larger space—some four times the requested size—could be rented at what seemed to be prohibitive costs. The would-be shop owner believed this was done “by design, to prevent competition” to other tenants. Having written to Manitoba’s attorney-general and submitted copies of the same letter to Winnipeg and Thompson newspapers, Borowski was banned from selling his wares in the camp and informed by Inco security that if he were caught flouting this directive, his merchandise would be confiscated and he would lose his position with Inco. Decrying “this (Moscow Type) restriction,” the thwarted businessman perversely went on to compare the bumptiousness of Inco’s security to Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann.[36] Whatever his initial setbacks, Borowski would go on to establish both his business and his reputation for political activism, which contributed to Thompson attaining responsible government and his own election to the Manitoba Legislative Assembly, where he would fill several ministerial portfolios.[37]

Figure 4

Thompson’s main commercial section in 1966 showing the Strand Theatre in the centre and the Hudson’s Bay Store on the right.

While considerable development was left to business and government, as Borowski had demonstrated, members of the new community also pushed for changes and created their own institutions. The establishment of a volunteer fire department and the acquisition of a “new” pumper truck in November 1960 was widely praised by the community. Voluntarism spearheaded numerous campaigns and led to the establishment of various churches, although by December 1961 only St. Lawrence Catholic Church had its own sanctuary built, while the Presbyterian, Mennonite, and United Churches met in commercial or municipal buildings. Despite the proliferation of religious and secular societies, there were concerns about an overall lack of coordination of charitable and community-building activities in Thompson. This led to calls for creation of a Community Chest, to correct what some saw as unnecessary overlap and chronic disorganization.[38] A chapter of the Rotary Club was initiated in June 1961, while grassroots organizations like the “Circle 55” club for square dancing began to proliferate and meet in the school gymnasium.[39] The local chapter of Boy Scouts hosted a dance for the wider community in October 1960, and the Thompson Athletic Society worked to promote and facilitate sport for all members of the community.[40] A talent show catering to the residents of Thompson and the nearby Inco camp was planned for October 1961. Held at the town school, the program was replete with “a variety of acts, combos, western singers, modern singers and student participation.” In a departure from earlier events, however, there was also a beauty contest to name “Miss Campsite of 1961.”[41] Given its climate and plans for the construction of arenas, hockey became a mainstay throughout Thompson’s protracted winters. Early in the town’s history, local enthusiasts formed a local league and adopted the constitution of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association, which would govern four or five teams. By the end of November 1963 the ice in both the town and camp rinks was ready and being utilized.[42]

Local women’s organizations also shaped shape the development of Thompson. By the end of 1961 the Ladies’ Community Club was devoting much energy to the establishment of a library. As the Thompson Citizen reported on an organizational meeting at which “the turnout was gratifying … It was felt, however, that now the scope of the club should be enlarged from that of providing recreational and hobby interests to more worthwhile community projects. Accordingly two conveners were elected to look into the establishment of a lending library for the town and campsite. Already inquiries have been made into this project and the library should be open for use by the end of January or at the latest, by early February. Donations of books from interested citizens would be most gratefully welcomed.”[43]

It was made clear that the club’s “ultimate objective is the realization of the proposed community center.”[44] The original library was housed in the school, until the town built a separate library as part of their commemorations of Canada’s Centennial celebrations.[45] Subsequent incarnations of the community club provided financial support to sporting organizations and offered organized swimming lessons for local children and courses for adults in areas like typing and cooking.[46]

However much the promoters and many inhabitants of the townsite may have wished to emphasize their community’s modernity and accoutrements, the marriage of primary extraction and modern town life did not always work seamlessly. While the campsite was being phased out, there were undercurrents of tension between the apparent domestic serenity of the town and the single men of the camp.[47] The newspapers often reported transgressions of the public peace, and local magistrates were confronted with numerous examples of those residents, both in the town and in the mining camp, that harkened back to the rowdyism that marked earlier mining communities. In May 1961 six men were fined for participating in a street fight.[48] Thompson’s relative remoteness and the isolation of many individuals was viewed as a major source of the trouble. It was commonly believed that many young men came into the town from the camp to indulge in disorderly behaviour. In December 1961 magistrates handed down a two-year suspended sentence and a fine of $150 to a man who breached the public peace and possessed an offensive weapon, while another was handed down a one-year suspended sentence and fined $50 for shoplifting from the Hudson’s Bay store. Underage alcohol possession and disorderly conduct rounded out the rest of the charges in the community.[49]

The dangers of work in the mines, however, could provide a form of cohesion and unity between town and camp, particularly when tragedy resulted. The deaths of four young miners in September 1961 shocked the broader community. Similar accidents would be constant reminders of the dangers inherent in the mining industry.[50]

Although Thompson may have been adopting the trappings of “modern” urban realities from the south, there was no escaping the fact that whatever its relative distance from the affairs of the townsite, Inco still had a major influence on the lives of most of its inhabitants. Employment, accidents, and tragedies aside, Inco’s influence remained pervasive. In November 1961 the company’s senior vice-president, R.D. Parker (for whom Thompson’s high school was ultimately named) was the keynote speaker at a banquet for the local branch of Inco’s Quarter Century Club.[51] Although Thompson was officially an “open town” and the town’s resident administrator was not a company appointment, the original contract between the province and Inco made it clear that the appointee had to be acceptable to the company, who paid a significant portion of his salary.[52] The result was that there was no clear line between civic and company policies, and in times of labour stress the separations were even more obscured, given the heavy reliance most of the town’s population had on Inco. In an ill-concealed rant the Nickel Belt News explained, “These miserable tools of the bosses, enemies of all workers, in the name of Steel Liberators, have left behind them a shameful record-raiding, dividing families, father against son, husband against wife…. Ask these Steel Pork Choppers in Thompson today how many unorganized workers they have organized in the past ten years. Ask them what they have done to justify their fat salaries of $15,000 per year. Does buying free beer for workers improve the conditions for Thompson workers or the community as a whole?”[53]

Crime and union politics were certainly not absent from urban centres in southern Canada. However, the relative isolation and dominance of one corporation in a community like Thompson was typical in northern resource towns. The predominance of men, particularly of young single men, could make for a potentially explosive mixture. However, the degree to which race and ethnicity played a role in difficulties is difficult to assess. Local histories often pay little if any attention to these issues and tend to place an emphasis on “progress” and growth.[54]

Contemporary accounts suggest that Thompson seemed to embrace the growing cultural diversity that was slowly gaining acceptance across Canada. A Trinidadian visitor to Thompson commented on the city’s “cosmopolitan population.”[55] Attempts were made to accommodate the newcomers, and one teacher remembered that there was a “non-English-speaking class at the high school” that included students “from Finland, Italy, and all around.” Technologies were employed to help them improve their English, although their teacher remembered “the kids they could communicate with the others, whether they knew their language or not.”[56]

Inco itself seemed to celebrate the diversity of its Thompson workforce, highlighting the fact that many Thompsonites came from as near as Roblin, Manitoba, or further afield from Ireland, France, Scotland, Latvia, Belgium, Spain, and Brazil. One worker came to the town from Jamaica, although of Hawaiian ancestry. Indeed the company liked to point out that one worker from Crane River, Manitoba, was “of Indian parentage.”[57]

Despite the fact that Thompson lay within the traditional territory of the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation, based at Nelson House, and occupied a part of the province where the vast majority of the population were Indigenous, the general absence of these people in local newspaper reports from the early 1960s is pointed.[58] While Thompson was an overwhelmingly Euro-Canadian enclave during its earliest stage of development, Indigenous people were certainly not absent.[59] Local Indigenous residents participated in the initial construction and preparation of both the mine and Thompson townsite but were deemed to lack the necessary skills for the post-construction period.[60] Although by 1960 Thompson boasted at least one stop sign in both English and Cree that was said to cater to the town’s “mixed population,” it is equally possible this isolated example of bilingualism existed as much for its apparent “exoticism.”[61]

The stark reality was that Indigenous men were officially discouraged from continued residency in Thompson or the campsite after the initial establishment work had been completed. A large number of these men established a tent city in the bush beyond the town’s train station, which had no official standing within the Thompson scheme. Several of the men were joined by their families. While some of these men found work in the initial building, the continued housing shortages and official discrimination meant that there was no room for them in the town itself, with the result that most First Nations people were essentially homeless. While jobs were sometimes available, many faced overt discrimination or racism that either barred them from taking up these positions or made them untenable.[62]

The situation in nearby communities was not much better. Reports from missionaries of the relative destitution at Nelson House in December 1962 created a flurry of negative national and international attention and condemnation. There was pressure on Inco to suspend their policy against hiring Indigenous people.[63] Negotiations between authorities representing the federal and provincial governments were started with Inco to see if the company might change their exclusionary policies. The chief of Nelson House explained that should these talks fail to produce results, plans were underway that would see 16,000 Indigenous demonstrators march on Thompson in protest. As a stopgap measure, however, the premier promised to speed up construction of a winter road connecting Nelson House to Thompson, as well as the building of an airstrip, all of which would employ Indigenous people.[64]

That the proposed protest did not materialize was due in no small part to a period of serious labour unrest within Thompson proper, which led to a protracted strike by Inco workers that dominated the summer and early autumn of 1964.[65] However, once the dust had settled on this matter, enough interest remained concerning local Indigenous people that officials came to address the local Thompson Religious Council on “work [that] will benefit the situation of the Indians and Metis in Northern Manitoba.”[66] By the end of 1964 some local Indigenous people were “admitted to an assortment of mining jobs in which they had demonstrated their competence,” but suggestions remained that local organizations such as the United Steelworkers of America had difficulty breaking old ethnic stereotypes.[67]

Undoubtedly spurred on by the attention created by the initial impasse between Indigenous peoples and Inco, the local Anglican congregation created a committee for “Indian Works” in January 1963.[68] The presence of First Nations and Métis in Thompson was attested to by the fact that members of the community formed the Keewatin Club, which sought “to help people of Indian origin adapt themselves to a different way of life such as living in a modern community like Thompson” and to provide social supports and networks. Almost immediately the club organized for the display and sale of “Indian handicrafts” made by women from Nelson House at the Thompson Plaza in May 1963.[69] Several months later Thompson’s Community Development office sponsored a sale of birchbark baskets and other goods made by women from Nelson House and the more distant communities of Shamattawa and York Landing. It subsequently held a “social” at the newly completed Friendship Centre, which was viewed “as a bridge between the Indian and non-Indian cultures.”[70]

Channelling this spirit of understanding, the membership of the local Steelworkers Union eventually made overtures to the Keewatin Club to assist with work that “will bring dignity and equality to the Indian-Metis population.”[71] The degree to which these diverse communities were brought together is debatable, given that the local hockey league created “the all-Indian club” to play the other non-Indigenous teams.[72] At least one of Thompson’s Euro-Canadian residents was dubious that the poverty and injustice faced by Thompson’s Indigenous residents was the result of “a white racist society.” Instead they preferred to fall back on negative stereotypes as a more satisfying explanation.[73] At least one resident was affronted by what he saw as sanctimonious reporting on local Indigenous people.[74] Early in 1970 a reader of the Thompson Citizen forwarded a letter apparently written to someone in Ontario who caught an unfavourable television program that decried life in Thompson. Ostensibly the contents were not the words of a Thompson resident, although they may have reflected attitudes in certain circles. The letter noted that women found it too expensive a place to board, while men tended only to remain for seventeen days for “lack of female companionship and the absence of any kind of recreation except to go to the hotel and drink with the Indians.”[75]

The ugly truth was that by the late 1960s Thompson, a city that constantly revelled in and boasted about its modernity, was confronted by a less savoury reality. The “mushrooming” population had made for a serious strain on resources. Originally designed for 8,000 people, the town could conceivably grow to far more. The Manitoba Metis Federation and various women’s organizations within Thompson itself began to publicly highlight what many people were aware of: the growing population, high cost of living, and general levels of poverty amongst Manitoba’s First Nations had contributed to deplorable housing conditions, which had become a national scandal.[76] There was resistance from within Thompson to an idea floated that would see hundreds from the most impoverished outlying communities relocated to Thompson. The most vocal protests came from those who feared such a move would “depreciate property values.” Others saw that it as “a golden opportunity to operate our north country in a civilized way.” There was a strong hope that integration, well handled, would avoid the creation of a “ghetto” as existed for the Dene people forcibly removed to Churchill in previous decades.[77] While there was a growing sense of the inequalities and injustices imposed on the Indigenous population, it would be decades more before the tough work of reconciliation would really begin.[78]

By the late spring of 1970 Thompson was an established community that could boast a population of close to 19,000. A recently completed ten-storey residential apartment building, aptly called Highland Towers, loomed over the city’s east end. The new Westwood Shopping Centre opened to complement the original plaza. As with most municipalities, there were divided opinions on new programs and projects and considerable discussion about the construction of a new pool and talk of further commercial and residential units. Other disputes—professional, labour-oriented, and personal—were part of life in Thompson.[79] Given its population and apparent vigour, Thompson, which had become a town only in January 1967, was proclaimed a city in July 1970, during a visit by the Queen and members of her family before a crowd estimated at between 12,000 and 15,000.[80]

Thompson’s relatively orderly origins and early development through the late 1950s and the 1960s distinguished it from earlier mining and resource towns in the Canadian north. The involvement and cooperation of private industry and the provincial government were part this process. The result was a fully serviced and planned community that borrowed heavily from urban and suburban planning that was so dominant in post–Second World War Canada. The influence of some inhabitants of this newly established enclave, however, also played a significant role in shaping the social, religious, and cultural landscape of this community, reflecting the values and ideals of urban life they brought with them from other parts of Manitoba and Canada, while adapting and shaping them to realities of the northern resource frontier. However, policies and predominant attitudes often placed local Indigenous peoples on the margins of this urban experiment that had emerged in their traditional lands. The process of finding employment and acceptance would be hard fought.

Much of the optimism that bolstered Thompson peaked in 1970. Less than a year after the fanfare that had accompanied the city’s new status, an international drop in nickel prices spelled a new era of uncertainty and a precipitous decline. While the economic situation would stabilize, the city’s population would never recover to the heady days of the late 1960s and very early 1970s.[81] In this way Thompson shared a link with other predominantly resource towns across the Canadian north. While the community would be buffeted and altered by the economic and social change of subsequent decades, the original planning and institutions that established it cast long shadows that continue to effect and shape Thompson into the early twenty-first century.

Appendices

Biographical note

Greg Stott is an associate professor of history in the Faculty of Arts, Business, and Science at University College of the North in Thompson, Manitoba. His work tends to focus on community and social history in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Canada.

Notes

-

[1]

A very early draft of this article was presented in August 2011, at the Northern Atlantic Connection Conference Canada and the Nordic Countries at Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark. A much more up-to-date version was presented at the Urban History Association Conference held at Loyola University in Chicago, in October 2016,

-

[2]

Robert Robson, “Manitoba’s Resource Towns: The Twentieth-Century Frontier,” Manitoba History 16 (Autumn 1988): 1–2; Norman E.P. Pressman and Kathleen Lauder, “Resource Towns as New Towns,” Urban History Review 1 (June 1978): 79–95.

-

[3]

Similar observations have been made about Fort McMurray, the centre of Alberta’s Tar Sands development. However, Fort McMurray had already been established as a trading and transportation centre long before the serious development of the oil industry in the 1960s. Arthur Krim, “Fort McMurray: Future City of the Far North,” Geographical Review 93, no. 2 (2003): 258–66.

-

[4]

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896–1899 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1972), 46–8, 280–309; Charlene L. Porsild, “Culture, Class and Community: New Perspectives on the Klondike Gold Rush, 1896–1905,” PhD diss., Carleton University, 1994; Robson, “Manitoba’s Resource Towns,” 1–10.

-

[5]

Douglas O. Baldwin and David Duke, “‘A Grey Wee Town’: An Environmental History of Early Silver Mining at Cobalt, Ontario,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 34 (Fall 2005): 71–87; Douglas O. Baldwin, “Public Health Services and Limited Prospects: Epidemic and Conflagration in Cobalt,” Ontario History 75, no. 4 (1983): 374–402.

-

[6]

Will Steinburg, “High Stakes and Hard Times: Herb Lake and Depression-Era Mining in Northern Manitoba,” Manitoba History 68 (Spring 2012): 17–27.

-

[7]

Hugh S. Fraser, A Journey North: The Great Thompson Nickel Discovery (Thompson: Inco, 1985), 210–28; “Better 1959 Nickel Demand Expected,” Winnipeg Free Press, 4 May 1959. Thompson was not the first proposed metropolis for Northern Manitoba. Much earlier in the century, Winnipeg-based architect William Burns created fantastic designs for the proposed Roblin City at the mouth of the Churchill River on Hudson Bay. The plan borrowed heavily from popular urban design of the early twentieth century but paid scant attention to the realities of life in the far north of the province and was never realized. Only with the completion of the Hudson Bay Railway in the late 1920s did the vastly more modest town of Churchill emerge at site. James Burns and Gordon Goldsborough, “Roblin City: A Gleaming Metropolis on Hudson Bay,” Manitoba History 68 (Spring 2012): 40–3.

-

[8]

Robson, “Manitoba’s Resource Towns,” 8–10; Graham Buckingham, Thompson: A City and Its People (Thompson: Thompson Historical Society, 1988), 38.

-

[9]

Doug McBride, “Job Seekers Continue to Stream into North,” Winnipeg Free Press, 7 January 1958.

-

[10]

Elder Jack Robinson, interview by Greg Stott, 8 December 2016, Thompson, Manitoba. Subsequently some of the local First Nations men were employed by other companies such as Comstock to help prepare the townsite.

-

[11]

“The Bay at Your Service in Thompson!” Advertisement in the Central Manitoba News and Advertiser, 6 April 1960; “This Year’s Winter Job Campaign Was ‘Fruitful,’” Winnipeg Free Press, 26 March 1960. The National Employment Service office in Winnipeg reported that a number of construction projects in Thompson meant that approximately 1,000 construction workers had found employment over the winter season.

-

[12]

“Carefully Planned Townsite Experiencing a Terrific Growth,” Thompson Citizen, 10 May 1961; Richard Harris, Creeping Conformity: How Canada Became Suburban, 1900–1960 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 1–17, 129–54. One thing Thompsonites had to contend with was the ravens that wreaked havoc by infiltrating garbage cans and scattering refuse around the streets. “Ravens Create Local Garbage Nuisance,” Nickel Belt News, 1 November 1961.

-

[13]

“Story of Progress,” Nickel Belt News, 1 November 1961. See Steve Penfold, “‘Are We to Go Literally to the Hot Dogs?’: Parking Lots, Drive-ins, and the Critique of Progress in Toronto’s Suburbs, 1965–1975,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 33 (Fall 2004): 8–23; Statistics Canada, 1966 Census of Canada Census Profiles, Divisions and Subdivisions Western Provinces, “Table 9: Population by Census Subdivisions 1966 by Sex, and 1961,” catalogue 92-606, vol. 1 (1–6), June 1967, page 50. The population of Mystery Lake—of which Thompson was the overwhelming population centre—had 8,989 residents in 1966, of whom 5,152 were male and 3,837 were female. The total population in 1961 stood at 3,449.

-

[14]

“Paint Lake Lots Will Be Available This Summer,” Nickel Belt News, 17 May 1961. In early July 1961 two parties from Thompson were lost overnight on Paint Lake when they became disoriented and lost their way back to the landing area. All were found the following morning. “All Okay Following Long Night,” Thompson Citizen, 20 July 1961. Elder Robinson, interview.

-

[15]

Buckingham, Thompson, 42.

-

[16]

Buckingham, Thompson, 46–50.

-

[17]

“Manitoba’s Thompson to Be Big, Smartly Modern Community: New Town Will Keep Pace with Great Inco Plant,” Inco Triangle 19, no. 7 (February 1959): 4, 8–9; “Community Pride Soars as First Thompson School Opened,” Inco Triangle 19, no. 6 (September 1959): 6–7; Statistics Canada, 1971 Census of Canada Census Profiles, Population Census Subdivisions Historical, “Table 10: Population by Five-Year Age Groups and Sex, for Incorporated Cities, Towns, Villages, and Other Municipal Subdivisions of 10,000 Population and Over, 1971,” 19–20. In 1971 women constituted just under 44 per cent of the population of 19,000. The objectification of women survived well beyond the early days. In August 1968 women between eighteen and twenty-five were encouraged to enter the local Steelworkers’ beauty contest. “Steelworkers Queen Contest Open to All Girls 18–25,” Thompson Citizen, 13 August 1968. Even in 1970 it was alleged that a woman was not advised to go to Thompson “unless she was already married, because the majority of the ones that do go get tangled up with some man that won’t marry them and then they live common-law and never get back out of the place.” “T.V. Gives Poor Show for Thompson,” Thompson Citizen, 19 March 1970. Provision for education did not initially include services for young school-aged children, so in 1962 schoolteacher Doreen Lindquist started a kindergarten class in her living room. She explained, “We had a fold-up table and a couple of benches that we could move in and out and push our furniture back. We played outside. It was something to get kids used to routines.” When demand increased, classes were moved to the Sunday School room of the United Church. Lindquist explained, “People would apply and be so disappointed when they couldn’t get in. So we had one class in the morning and one in the afternoon. Pretty soon it was every second day. There were four different classes operating at the same time.” Axel and Doreen Lindquist, interview by Greg Stott, 8 December 2016, Thompson, Manitoba, transcript.

-

[18]

“Community Memories from Lovina McTavish,” Heritage North Museum, http://heritagenorthmuseum.ca/thompson-area/community-memories/community-memories-from-7.html.

-

[19]

Axel and Doreen Lindquist, interview.

-

[20]

Grace Bindle, interview by Greg Stott, 7 December 2016, Thompson, Manitoba, transcript. The level of intimacy varied, but as Bindle explained she took to walking to the post office every afternoon, taking “the postmaster a piece of cake for his coffee break. Of course, everybody was waiting there to see what I brought him!”

-

[21]

Axel and Doreen Lindquist, interview.

-

[22]

Axel and Doreen Lindquist, interview. Given its northern location and climatic realities, regulations had to also focus on other modes of transportation. New provisions made to the Manitoba Traffic Act were to be strictly enforced by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Thompson, and it included the fact that “motor toboggans” or snowmobiles were not permitted to operate on the roads. It also noted that “vehicles will not be given a license due to inadequate safety devices such as brakes [!] on the machines.” “New Traffic Acts Says No Motor Toboggans on Roads,” Thompson Citizen, 19 November 1966. Brad Cross, “Modern Living ‘Hewn Out of the Unknown Wilderness’: Aluminum, City Planning, and Alcan’s British Columbian Industrial Town of Kitimat in the 1950s,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 45 (Fall 2016): 13.

-

[23]

Buckingham, Thompson, 137; “Thompson Car Club Hold First Rally Sunday,” Thompson Citizen, 13 August 1968.

-

[24]

“Many Leave Thompson for Xmas,” Nickel Belt News, 14 December 1961.

-

[25]

“Progress Notes,” Thompson Citizen, 27 June 1960. On 31 May 1961 it was announced that Thompson would be getting local tri-weekly milk delivery after Frechette’s Dairy at The Pas completed negotiations with the Thompson Supply Company.

-

[26]

“Manitoba’s Most Modern Theatre,” Thompson Citizen, 3 June 1960.

-

[27]

“Thompson’s Streets Will Be Paved,” Thompson Citizen, 19 April 1961.

-

[28]

“A&W Chain Restaurant to Open in Thompson,” Nickel Belt News, 17 May 1961; Penfold, “‘Are We to Go Literally to the Hot Dogs?’” 8–23.

-

[29]

“Thompson Gas Sponsors Cooking School” and “C.E.S.M.—T.V. Releases Programs,” Nickel Belt News, 30 November 1961.

-

[30]

“Simpson Visits Thompson,” Thompson Citizen, 7 September 1961; “T-V Station Manager Named,” Thompson Citizen, 5 October 1961.

-

[31]

“Modern Lounge Opened,” Thompson Citizen, 20 July 1961.

-

[32]

“Shopping Centre Opens,” Nickel Belt News, 1 November 1961; “Shopping Plaza Ready by July,” Thompson Citizen, 26 April 1961. Initial hopes to have the plaza opened by July were unrealistic and the official opening was delayed for several months. On a front page article, “Thompson Plaza Official Opening,” the Thompson Citizen of 8 November 1961 reported, “The three-day celebration that marked the official opening of the Thompson Shopping Plaza was concluded on Saturday with a community-wide dance in the mall.” Lizabeth Cohen, “From Town Center to Shopping Center: The Reconfiguration of Community Marketplaces in Postwar America,” American Historical Review 101 (October 1996): 1050–81. See also “Thompson Gets Enclosed Giant Shopping Centre,” Winnipeg Free Press, 8 November 1960.

-

[33]

Donica Belisle, “A Labour Force for the Consumer Century: Commodification in Canada’s Largest Department Stores, 1890 to 1940,” Labour / Le Travail 58 (Fall 2006): 107–44; Belisle, “Exploring Postwar Consumption: The Campaign to Unionize Eaton’s in Toronto, 1948–1952,” Canadian Historical Review 86, no. 4 (2005): 641–72; Mark A. Swiencicki, “Consuming Brotherhood: Men’s Culture, Style and Recreation as Consumer Culture, 1880–1930,” Journal of Social History 31 (Summer 1998): 773–809; Gretchen M. Herrmann, “His and Hers: Gender and Garage Sales,” Journal of Popular Culture 29 (Summer 1995): 127–45.

-

[34]

“Story of Progress,” Nickel Belt News, 1 November 1961. See also Nicholas Hrynyk, “Strutting Like a Peacock: Masculinity, Consumerism, and Men’s Fashion in Toronto, 1966–72,” Journal of Canadian Studies 49 (Fall 2015): 76–110.

-

[35]

“Chamber of Commerce Formed for Thompson,” Nickel Belt News, 7 December 1961.

-

[36]

Joe Borowski, “Citizens of Thompson: For Your Information,” Thompson Citizen, 25 April 1963.

-

[37]

Buckingham, Thompson, 197, 203, 213, and 217.

-

[38]

“Need for Community Chest Here” and “Xmas Church Services,” Nickel Belt News, 21 December 1961. By the spring of 1961 there were five churches established with regular services, although only St. Lawrence’s Catholic Church had a building erected. Three more congregations anticipated building soon.

-

[39]

“Charter Night for the Rotarians,” Thompson Citizen, 29 June 1961; “‘Circle 55’ Resuming Square Dancing,” Thompson Citizen, 19 October 1960.

-

[40]

“Boy Scouts Have Successful Dance,” Thompson Citizen, 26 October 1960. On 10 May 1961 the Thompson Citizen reported that the Thompson Athletic Association was planning for summer baseball as well as a Fish Derby for 1 July and a Labour Day Field Day. “T.A.A. Meeting Plans Summer Program,” Thompson Citizen, 31 May 1961.

-

[41]

“Another Talent Show,” Thompson Citizen, 14 September 1961.

-

[42]

“CAHA Constitution Adopted,” Thompson Citizen, 21 November 1963; see “Senior Hockey Campaign Opens Sunday,” Thompson Citizen, 28 November 1963.

-

[43]

“Ladies’ Community Club Planning Lending Library,” Thompson Citizen, 30 November 1961.

-

[44]

“Ladies’ Community Club Planning Lending Library”; “Thompson Town Notes,” Thompson Citizen, 6 December 1961. The mothers of Thompson’s Girl Guides and Brownies sponsored a bake sale at the newly completed plaza early in December 1961. Other women’s organizations included chapters of the IODE and the Order of the Royal Purple. Buckingham, Thompson, 125, 139, 149, 176.

-

[45]

Buckingham, Thompson, 124, 152. Thompson’s Centennial Chorus raised funds in their concerts and contributed funds toward the purchase of a clock for the library in 1968. “Centennial Chorus Donate $50 toward Purchasing a Clock for Library,” Thompson Citizen, 19 January 1968.

-

[46]

“You May Still Register for Swimming,” and “Community Club Wants to Pay All Accounts of Thompson Athletic Club,” Thompson Citizen, 9 July 1964. The best statistics for early Thompson come from the 1971 census, which clearly indicate the relative youth of the community’s population. Thirty-six per cent of the population was under fifteen years of age, and only 150 people out of 19,000 were over the age of sixty, or less than 1 per cent. More than 63 per cent of Thompsonites fell between the ages of fifteen and fifty-nine. Males outnumbered females in every age category except for those between sixty-five to sixty-nine and those over seventy-five. Statistics Canada, 1971 Census of Canada Census Profiles, catalogue 92-715, vol. 1, part 2, “Table 10: Population by Five-Year Age Groups and Sex, for Incorporated Cities, Towns, Villages and Other Municipal Subdivisions of 10,000 Population and Over, 1971,” 19–20. Overall in Manitoba the gender balance was much closer to 50 per cent, with women representing 493,637 of the province’s population of 988,247 inhabitants. In Manitoba’s Census Division 16, of which Mystery Lake and Thompson were a part, just under 47 per cent of the population were female. See Statistics Canada, 1971 Census, catalogue 92-702, vol. 1, “Table 6: Population by Sex, for Census Subdivisions, 1971,” 50, 52; Bindle interview.

-

[47]

“Union Has Successful Labor Day Banquet,” Thompson Citizen, 7 September 1961. On Labour Day a banquet was hosted by the newly established Union of Mine-Mill and Smelter Workers, Local 1026 for 200.

-

[48]

“Six Men Each Fined for Fighting,” Nickel Belt News, 17 May 1961. In June 1961 magistrates dealt with cases of pickpocketing, liquor possession, and one charge of possession of a revolver. “Police Court,” Thompson Citizen, 22 June 1961.

-

[49]

“Court News,” Nickel Belt News, 21 December 1961.

-

[50]

“Thompson Mine Tragedy,” Thompson Citizen, 14 September 1961. Twenty-one-year-old Harold Oren Kines was from Neepawa, Manitoba, while Jack Walter Parr, twenty-five, hailed from Neudorf, Saskatchewan, James Ivan Ryan, twenty-two, from Marian Bridge, Nova Scotia, and Hans Peter Heeg was a twenty-five-year-old German immigrant. Similar accidents would remain part of life in the northern mining town. See “Death Reported at Inco Mine,” Thompson Citizen, 20 August 1968; and “Injured Miner Dies,” Winnipeg Free Press, 21 July 1969.

-

[51]

“High School Column,” Thompson Citizen, 29 November 1961. The opening of the high school, slated for the fall of 1961, was delayed until 15 November 1961 “because some important equipment hadn’t been either delivered or installed.” Nickel Belt News, 1 November 1961. Within two weeks of its opening, however, the high school was well-enough established to warrant a column in the Thompson Citizen reporting on sports, social activities, and plans for a graduation banquet. “High School Column,” Thompson Citizen, 29 November 1961.

-

[52]

Buckingham, Thompson, 59.

-

[53]

“Mine-Mill Claim Bargaining Split,” Nickel Belt News, 14 December 1961; “Hard Rock Miners to Hold Conference Here,” Nickel Belt News, 21 December 1961; Sophie Blais, “Nouvelles réflexions sur les travailleurs et la grève de Kirkland Lake, 1941–1942,” Labour / Le Travail 64 (Fall 2009): 107–33; Robert S. Robson, “Strike in the Single Enterprise Community: Flin Flon, Manitoba, 1934,” Labour / Le Travail 12 (Fall 1983): 63–86.

-

[54]

“Woman Dies Following Stabbing: Husband Held in Custody,” Thompson Citizen, 3 January 1963. See Morley Gunderson, Allen Ponak, and Daphne G. Taras, Union-Management Relations in Canada, 5th ed. (Toronto: Pearson Education, 2005); Alison Braley-Alison, “Harnessing the Possibilities of Minority Unionism in Canada,” Labor Studies Journal 38, no. 4 (December 2013): 321–40.

-

[55]

“Our Cover Girl an Attractive Town Visitor,” Thompson Citizen, 12 July 1968.

-

[56]

Bindle, interview.

-

[57]

“On the Job at Thompson,” Inco Triangle 22, no. 10 (January 1963): 5; “Operation Cuneo,” Inco Triangle 24, no. 2 (May 1964): 12, 16. When famed British artist Terence Tenison Cuneo (1907–1996) was commissioned to complete a series of paintings on Thompson, he arrived in the community and was feted. He apparently revelled in the northern scenery and even donned what were deemed “Indian mukluks” and was taken to see an abandoned trapper’s cabin preserved on the mine property. Beverley Cole, “Cuneo, Terence Tenison (1907–1996),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/60751. The comparative diversity of Thompson’s population was also reflected in the staff at the Thompson Inn. Schoolteacher Grace Bindle spent her summers in the early 1960s working at the hotel. She remembered, “It was very exciting because there were people from all over the world coming here to work…. There was an Italian lady cleaning rooms, a Finnish lady, myself, and I forget how many others.” Bindle, interview.

-

[58]

One article published in the local paper in 1966 suggested that many saw Thompson as a non-Indigenous community. A presentation was to be made about “the Indians who come to work and live in our community” (author’s emphasis). “Round the Town,” Thompson Citizen, 18 November 1966. There was acknowledgement of this earlier history, but there seems to have been an assumption of a distinct break with the past. See “A Link with the Days before Inco Came to Manitoba,” Thompson Citizen, 19 October 1960.

-

[59]

Buckingham, Thompson, 1–6. Buckingham’s work sheds some light on the people who lived in the vicinity of what would become Thompson in the early twentieth century, but subsequently the pre-1956 inhabitants are paid scant attention.

-

[60]

“3 Fatal Accidents in the Burntwood,” Thompson Citizen, 7 September 1961. Twenty-six-year-old Jonathan Spence drowned when the boat he was travelling in was swamped in the river. He had arrived in Thompson a year before to find work with a contractor.

-

[61]

“Our Fast-Growing Indian Problem: Government Realizing Responsibility Role,” Financial Post, 9 February 1963; clipping from Winnipeg Tribune, ca. 1960, as quoted in Buckingham, Thompson, 136.

-

[62]

Elder Robinson, interview.

-

[63]

“The State of Manitoba Indians,” Ottawa Citizen, 18 December 1962; “Inco Reported Hiring Indians,” [Regina] Leader-Post, 20 December 1962; “Three-Point Aid Program for Nelson House Indians,” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 29 December 1962; Dominique Marshall and Julia Sterparn, “Oxfam Aid to Canada’s First Nations, 1962–1975: Eating Lynx, Starving for Jobs, and Flying a Talking Bird,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada 23, no. 2 (2012): 298–343.

-

[64]

“Indians Threaten Protest March on Thompson,” Thompson Citizen, 3 January 1963. Those listed on the initial negotiating team included Premier Duff Roblin, Chief Gilbert MacDonald, two clergymen serving in Nelson House, the local supervisor of Community Development, and an interpreter. A decade later the development of Leaf Rapids, 220 kilometres northwest of Thompson, was markedly different both in the techniques used in developing the townsite as well and the ways Indigenous people were involved in all aspects of the community. Sarah Ramsden, “Developing a Better Model: Aboriginal Employment and the Resource Community of Leaf Rapids, Manitoba (1971–1977),” Manitoba History 68 (Spring 2012): 6–16. The marginalization of Indigenous people was not unique to Thompson. Officials in Winnipeg forcibly removed a number of Métis families from a suburban area in order to complete further development. David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 42, no. 1 (2013): 3–25.

-

[65]

Buckingham, Thompson, 140–5. The strike caused considerable hardship to many, and many single men and entire families left the town before it was over. As one resident remembered, “I was the financial secretary for the Steelworkers at the time. Many on the workforce were discontented. Some had mortgages, some second mortgages, as well as bank loans for furniture and necessities. Many were overextended financially, and without accommodation after the closure of the campsite, they had to have a place to live. Those who remained during the strike lived in basement suites or boarded with families who had already purchased homes. Conditions were crowded, but for the most part, workers were treated well.” Axel Lindquist, interview by Greg Stott, 8 December 2016, Thompson, Manitoba. Transcript.

-

[66]

“Robert Langin Will Speak at T.R.C. Meeting,” Thompson Citizen, 24 January 1963.

-

[67]

“What Our Indians Want,” Montreal Gazette, 10 October 1964.

-

[68]

“Church Officers Elected for 1963,” Thompson Citizen, 31 January 1963.

-

[69]

“Indian and Metis Organize Club,” Thompson Citizen, 9 May 9, 1963. In 1957 a Winnipeg-based reporter was increasingly concerned about the flooding of Manitoba markets by cheaply priced merchandise from Japan. On a visit to Thompson he found these good there as well, including “Indian moccasins” made in Japan. Gene Telpner, “Japanese Goods Hit Heavily at Winnipeg’s Garment Trade,” Winnipeg Free Press, 29 November 1957. In February 1964 the congregation of St. James Anglican Church discussed a proposal to develop “outreach to persons of Indian descent in the community.” “St. James Holds Annual Meeting,” Thompson Citizen, 27 February 1964.

-

[70]

“Handicraft Sale Friday,” Thompson Citizen, 26 September 1963; “Hold Season’s First Social,” Thompson Citizen, 7 November 1963, page.

-

[71]

“Membership Present $100,” Thompson Citizen, 12 December 1963. This organization apparently eased to function sometime in the middle of the decade. It was reconstituted in October 1968: “Indian and Metis Club Formed Here,” Thompson Citizen, 24 October 1968.

-

[72]

“CAHA Constitution Adopted,” Thompson Citizen, 21 November 1963. Tensions mounted when a local resident calling himself “An Unpaid Landlord” complained that a fledgling program sponsored by the federal government “to allow a few Indian children to integrate and help them overcome the big hurdle of discrimination,” commencing on 1 September 1963, created ire when the monies being paid to the host families for room and board did not materialize until the end of November. While the beef was not with the children or their families but with federal authorities, the upset citizen asked, “‘Does the Indian Affairs Branch … doom every good program it starts by financially tying the hands of those who are trying to make the program work?” Letter to the editor, Thompson Citizen, 16 January 1964. Thompson’s branch of the Order of the Royal Purple sponsored a clothing drive in Thompson to send to the children of nearby Nelson House in May 1964: “Thompson Town Notes,” Thompson Citizen, 14 May 1964.

-

[73]

Letter to the editor, Thompson Citizen, 26 February 1968.

-

[74]

Ted Willcox, letter to the editor, Thompson Citizen, 1 November 1964.

-

[75]

“T.V. Gives Poor Show for Thompson,” Thompson Citizen, 19 March 1970.

-

[76]

“Thompson Women Discuss Housing,” Thompson Citizen, 1 November 1968; “Metis Group Air Their Housing Gap,” Thompson Citizen, 11 November 1968.

-

[77]

“Chamber Briefs,” Thompson Citizen, 4 November 1968. The Thompson Citizen had earlier declared that a war on poverty had to be taken on by residents of the north. “Northern Manitoba, Too, Must Declare War on Poverty!” Thompson Citizen, 12 January 1966. Interestingly enough, a correspondent from the tiny community of Ilford, some 200 kilometres northeast of Thompson along the Hudson Bay Railway, complained, “There has been a lot of talk of work for the Indian and Metis population in the north. A strange thing though, no one has asked these people what they think of this.” Cliff Thompson, “Views and News from Ilford,” Thompson Citizen, 13 May 1966. See Ila Bussidor and Ustun Bilgen-Reinart, Night Spirits: The Story of the Relocation of the Sayisi Dene (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1997).

-

[78]

Kacper Antoszewski, “Thompson Council Endorses TRC Calls to Action,” Thompson Citizen, 23 March 2016. On21 June 2009 the City of Thompson and local Indigenous leaders signed the Thompson Aboriginal Accord after months of consultation. “Thompson Aboriginal Accord,” City of Thompson, http://www.thompson.ca/p/thompson-aboriginal-accord.

-

[79]

Buckingham, Thompson, 187, 200–5; “Mayor Brian Campbell Opens Westwood Shopping Centre,” Thompson Citizen,1 June 1970.

-

[80]

Buckingham, Thompson, 167, 199, 203.

-

[81]

Buckingham, Thompson, 211–17.

Appendices

Note biographique

Greg Stott est professeur agrégé d’histoire à la Faculté des arts, des affaires et des sciences de la University College of the North in Thompson, au Manitoba. Son travail se concentre surtout sur l’histoire sociale et communautaire des dix-neuvième et vingtième siècles au Canada.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4