Abstracts

Abstract

This paper discusses the Flemish Literature Fund (FLF), an autonomous government organisation created in 1999 by the Flemish Community to support Flemish literature at home and abroad. It traces the institutional history of the FLF, situating the organisation in the context of Flanders’ longstanding struggle for cultural autonomy within the Belgian state on the one hand and its strong but unequal ties to the Netherlands on the other. Using a translation sociological analytical framework, it goes on to argue that the FLF’s outgoing translation grant decisions reflect two strategies of international dissemination: a focus on the central languages of English, German and French, and a strategic use of the picture book genre to break into emerging languages on the periphery, especially Chinese. While the case of the FLF clearly illustrates the shifting power relations between state and market agents in the era of globalisation, it also indicates a novel approach to state-supported literary export designed to maximise a small, stateless nation’s international resonance in a world market for translations dominated by larger (nation-) states and languages.

Keywords:

- translation sociology,

- world market for translations,

- Flanders Literature,

- Flemish Literature Fund,

- Dutch literature in translation,

- cultural policy

Résumé

Cet article traite du Fonds flamand des lettres (FFL), une organisation gouvernementale autonome fondée en 1999 par le gouvernement flamand pour promouvoir la littérature flamande en Flandre et à l’étranger. Il retrace l’histoire institutionnelle du FFL, situant l’organisme dans le contexte de la lutte de longue date de la Flandre pour une autonomie culturelle au sein de l’État belge, d’une part, et de ses liens forts mais inégaux avec les Pays-Bas, d’autre part. Par l’intermédiaire d’un cadre analytique sociologique de la traduction, il soutient ensuite que les décisions relatives aux bourses de traduction du FFL reflètent deux stratégies disparates de diffusion internationale : l’accent mis sur les langues centrales que sont l’anglais, l’allemand et le français, et l’utilisation stratégique du livre d’images en tant que genre pour pénétrer des langues périphériques émergentes, en particulier le chinois. Si le cas du FFL illustre clairement l’évolution des relations de pouvoir entre l’État et les agents du marché à l’ère de la mondialisation, il témoigne également d’une approche novatrice d’exportation de la littérature soutenue par l’État, visant à maximiser la résonnance internationale d’une petite nation apatride dans un marché mondial de la traduction dominé par des langues plus parlées et par de plus grands États(-nations).

Mots-clés :

- sociologie de la traduction,

- marché mondial de la traduction,

- Fonds flamand des lettres,

- littérature néerlandaise dans la traduction,

- politique culturelle

Article body

Books travel through translation. A book’s international circulation depends in large part on how its transnational intermediaries navigate the world market for translations. Three types of boundaries most clearly delineate this market today: those enclosing nations, states and languages.[1] As publishers increasingly look outward in search of new content and new readers, the business of producing (translated) books becomes more and more about mediating across these boundaries: spotting and responding to industrywide trends, studying the editorial strategies of peers in other regions, cultivating contacts across culturally and geographically dispersed space, and pitching and acquiring translation rights. These activities are carried out and facilitated both by market agents (publishers and their transnational intermediaries: acquisitions editors, rights managers, scouts, trusted translators) and by state agents (governments and their cultural policy deputies specialised in literature and its international promotion). Relations between these two categories of agents have changed fundamentally in the era of globalisation.

This paper seeks to understand how one small state agent, the Flemish Literature Fund (FLF)[2], navigates today’s vast world market for book translations. The FLF is an autonomous government organisation created by a sub-sovereign state entity (the Flemish Community) to promote the literary works of a nation-specific grouping of authors (Flemish) working in a small language (Dutch). Exploring how such an agent gains access to and acts in the world market for translations gives novel insight into this market’s structure and dynamics. In what follows, I divide the discussion of the FLF’s outgoing translation and international promotion efforts into two parts: politics and policy. I first give an overview of the FLF’s institutional history, calling out three interconnected levels of power inscribed in it: the FLF’s position within the Flemish cultural field (nation), the Belgian state (state) and the Dutch-language literary field (language area). These levels correspond to the boundary types described above and overlap in interesting ways to condition how Flanders came to intervene in the world market for translations, itself a fourth level of power (transnational) to which the three others are constituent. In a second section, I zoom in on one important policy mechanism used by the FLF to promote titles internationally: translation subsidies for foreign publishers who publish books by Flemish authors and illustrators. Here, I analyse a dataset of 808 translated titles that have received support from the FLF since it began operations in 2000, looking particularly at which languages and genres were most subsidised, and to what strategic aim.[3] Both sections are informed by quantitative data sourced from the freely available translation database maintained by the FLF and its Dutch counterpart,[4] and qualitative data from the FLF’s year-end reports and interviews with FLF grant managers conducted by the author.

The World Market for Book Translations

The political, linguistic and economic boundaries that structure the world market for book translations are interconnected and co-implicated. Canada, for instance, is a sovereign, bilingual (arguably nation-) state. English is its largest (but not only) language and its English-language book producers share a market with the United States. Flanders is a sub-sovereign, autonomous community within the multilingual, federal Belgian state and its book producers share a language and a common book market with the Netherlands. The power dynamics pertaining within and across these boundaries manifest clearly in the process of determining which titles cross them. When a book by a Flemish author is being considered for translation, say, into English by a Canadian publisher, the exchange involves much more than the straightforward selling of intellectual property in the form of translation rights. There are any number of considerations that precede the foreign publisher’s decision: Does it fit its list? Will it register with readers? Did it sell well in the home market? Was it well-received by reviewers? Has it won prizes? Have rights already been sold for other languages or territories and if so, which ones and to which publishers? Conditioning these considerations are the very systemic constraints that give rise to the world market’s boundaries: politics (To what extent is the state involved in a translated book’s coming-into-being?), language (Are the source and target languages central or peripheral? What power relationships hold within and between them?) and economics (To what extent are profits a driving force in the decision to produce a translated book? How crucial is a subsidy to its coming-into-being?). Furthermore, once a book is in fact selected for translation—when it commences its international travels—it becomes a vehicle for other forms of capital. Alongside its economic potential, a translated title may also carry symbolic capital (prestige) vis-à-vis its original language, publisher, author, etc., and social capital (credibility) vis-à-vis its producers and transnational intermediaries. In this sense, a homologous relationship exists between a title and its makers: a critically acclaimed, well-executed book begets prestigious, credible producers, and vice-versa.

The socio-economic sphere described above is captured in the expression “world market for translations,” a heuristic device created by translation studies scholars working in the subfield of translation sociology to understand how books circulate internationally in the era of globalisation.[5] Two main models have been put forward to explain the current structure of this market. The first is Johan Heilbron’s Immanuel Wallerstein-inspired “world-system of translation,” which posits a core-periphery model for explaining global book translation flows. For Heilbron, a language’s position in the world-system of translation is determined by the literary trade balance of its incoming and outgoing book translations. Languages that export more and import less are central while those that import more and export less are peripheral. Using bibliographic data from UNESCO’s Index Translationum database, Heilbron found the world-system of translation to be highly asymmetrical, with English occupying a hyper-central position, French and German as semi-central, and all other languages as peripheral (Heilbron, 1995, 1999).[6] For its part, Dutch is situated squarely on the periphery of this system, supplying just under 1% of the world’s source titles for translated books (Heilbron and Sapiro, 2016, p. 382) and importing upwards of a quarter of its domestic literary production through translation (Van Baelen, 2013, p. 35).

The other model is Gisèle Sapiro’s “transnational literary field” concept (Sapiro, 2015), a multi-field rendition of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s single-field framework for understanding the world of French publishing (Bourdieu, 2008). Sapiro groups producers of translated books according to scales of production and distribution (small-scale versus large-scale) on the one hand and their oppositional logics of valuation (aesthetic versus profit-driven) on the other. She finds that transnational literary transfer tends to accumulate at the small-scale pole, where publishers are less interested in turning a profit than they are in producing intellectually challenging, culturally important or artistically innovative titles (Sapiro, 2008a). It is here, too, that diversity (in terms of variety of source languages) is greatest (Sapiro, 2010).

Sapiro’s approach has its explanatory basis in field theory, which starts from the assumption that any social sphere organised around a common pursuit can be approached as an arena of social activity in which individuals and organisations (agents) are linked together through a shared set of objectively observable “rules of the game” and relations of competition and cooperation. Agents are endowed with unequal resources (capital) and struggle to advance their position through the strategic use and pursuit of these resources. In the transnational literary field, as in all fields of cultural production, capital can be divided into different types (Sapiro focuses on economic and symbolic), and can be interchanged through various instruments of conversion such as a steadily earning backlist (symbolic-to-economic), the acquisition of symbolically well-endowed titles from other literary fields (economic-to-symbolic), and so forth (Sapiro, 2012a, 2012b, 2015). Fields are always more than the markets they contain. The world market for translations can thus be thought of as a product of the contemporary transnational literary field, the political, linguistic and economic constraints of which structure all contexts in which translated books are produced, valued and received.

Other interventions have added new dimensions to this mode of analysis. Using a dominant/dominated distinction similar to Heilbron’s, Pascale Casanova shows that some languages (and, by extension, the agents that work in them) are historically endowed with more literary capital than others (2004). Thomas Franssen argues for a focus on genre sub-fields, which function according to their own internal rules and systems of valuation and respond to trans-border constraints differently (2015). James F. English’s work on instruments of capital intraconversion, which focuses on prizes but can easily be extended to other instruments like guest-of-honour platforms, adds new capital types and shows how one can be exchanged for another (2005). Brian Moeran demonstrates how trade events like international book fairs can be important “tournaments of value” for the arbitration of competing systems of symbolic, social and economic valuation (2010), and as spaces where performative interactions between agents help to define, hierarchize and display gradations of prestige and recognition in otherwise geographically dispersed, disembodied fields (see Moeran and Strandgaard Pedersen, 2011). All of these understandings underwrite the work of Canadian translation studies scholars such as Brian Mossop, whose call for a sociological approach to translation predates Heilbron and Sapiro’s influential article on the subject, “Outline for a Sociology of Translation” (2007), by almost twenty years (1988). That said, a similar mode of thinking about how books cross borders can be traced back at least to the Danish critic and author Georg Brandes, who was writing thoughtfully about the international dissemination strategies of book producers from smaller literatures at the turn of the nineteenth century (2013 [1899]).

State Versus Market in the Era of Globalisation

Alongside the source/target distinction—that is, whether an agent is looking to pitch a title for translation or acquire one—is a second important distinction: that between state agents and market agents. State agents have traditionally played a central role in mediating which books go beyond the borders of a source field, be it through ideology (projecting ideas and ideals globally), censorship (dictating what books are deemed acceptable for import and export) or cultural diplomacy and branding (presenting a particular image of country or nation through its literature). However, the role of state agents in today’s world market for translations has changed significantly as a result of Anglo-American-led processes of globalisation and conglomeration, which have been transforming the global publishing industry (indeed, all creative industries) since the 1980s (see Hesmondhalgh, 2007; Greco, 1989, 1999). The market for translated books has become more autonomous from state control as a result, but it has also become more constrained by economic imperatives. Transnational mergers and acquisitions have brought many major publishers of translated books together under a few very large international media corporations. And while many formerly independent houses vigilantly maintain their image and manner of working (sometimes purposely obscuring their new corporate affiliations), they inevitably must reconcile their editorial strategies with corporate profit expectations (Thompson, 2012). This has been found to contribute to decreased diversity in terms of source languages in the large-scale segment of the market and a tendency toward repertory standardisation, or publishing only “books that sell” (ibid.). Today, conglomerate-owned publishers often deem translations too risky because they are relatively expensive and time-consuming to produce, difficult to match to domestic literary tastes and rarely profitable. The concentration of distribution networks around large “big-box” chains such as Barnes & Noble in the US and Waterstones in the UK only exacerbates this (see Thompson, 2012; Sapiro, 2016). Many mainstream distributors simply do not make new translated books available to retailers, opting instead for a frontlist of bestsellers-in-translation and a backlist of canonical works of “world literature.”

At the same time, globalisation has brought about an increase in the number and diversity of small-scale publishers (Thompson, 2012, pp. 152-169), and in the number of translated books overall. According to the Index Translationum, the number of translations in the world increased by 50% between 1980 and 2000 (Sapiro, 2016, p. 87). In that time, the market has seen a flourishing of small-scale niche publishers committed to producing “literature across borders,” upstart publishers looking to capitalise on profitable titles from other language markets, and established independents seeking to diversify their lists. Some publishers with international aspirations have cut out foreign publishers altogether, opting to publish translations themselves under an affiliated imprint. This strategy of “in-house” transnational transfer can be a means to more easily access new language markets. One recent example of this is the Italian independent publisher Edizioni E/O, which had tremendous success with Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels published in English translation by its New York-based affiliate Europa Editions. Another example, this time from the Dutch literary field, is the children’s book publisher Lemniscaat, which publishes many of its titles in English translation under an imprint based in New York (McMartin, 2019).

Despite these processes of globalisation and conglomeration, today’s world market for translations remains to a significant extent structured by national literatures, or rather, by “the well-founded fiction of the existence of national literatures” (Sapiro, 2015, p. 341), which, in step with the rise of nationalism in the late eighteenth century, helped to transpose the lines of nationally delineated imagined communities onto the geopolitical map (Anderson, 2006). More than two centuries later, cultural policy in the domain of literature remains largely an affair of nation-states and stateless nations with official competency in cultural affairs. Many national governments (particularly in Europe) have policies to support “their” book producers, including fixed book prices, bursaries for authors, illustrators and translators and production supports for domestic publishers. These policies are often paired with translation support schemes and international promotion efforts. The German Publishers and Booksellers Association, which organises the Frankfurt Book Fair, lists 39 government organisations active in international promotion on their website (Häfner, 2018). Translation support schemes can also be found at the supranational level (translation projects supported under the European Commission’s “Creative Europe” programme, for instance) and at the transnational level in various forms (PEN International and its national chapters). In a recent development, representatives of 22 government organisations from 19 countries and regions in Europe converged to establish the European Network for Literary Translation (ENLIT),[7] indicating a new level of cooperation among state agents in Europe.

Whereas the nation has retained its importance as a principal category organising today’s transnational literary field, the state agents that exist to sustain national literatures no longer play the dominant producer role they once did. What was, pre-1980s, a supply-driven market dominated by governments’ foreign and cultural affairs bureaus has become a demand-driven market where decisions about what books are offered and selected for translation and how they are brought to market are largely made by market agents. As Heilbron and Sapiro have it,

this recent shift from political to more economic constraints has had the effect of weakening the supply-side and strengthening the demand-side, that is to say, diminishing, within the process of mediation, the preponderant role of agents of export (social bodies, translations institutes, cultural attachés, etc.), which are now increasingly obliged to take into account the space of reception and the activities of importing agents, specifically, the various agents in the book market: literary agents, translators, and most particularly, publishers.

2007, p. 99

While this shift has, as we have seen, facilitated an increase in the number of translated books and eased access to the market for many agents, it also “seriously impinges upon governments’ ability to control culture and cultural content in any nationalistic or protectionist way” (Flotow, 2007, p. 14). State agents now must “play by the rules” set by publishers and are obliged to traffic in the same types of capital and strategies of dissemination. This precludes any real power on the part of governments to dictate what gets translated and what does not. On the contrary, it limits the target of outbound cultural policy to the dominant vehicles of production—publishers—leaving cultural policy deputies to embrace a role as a new kind of literary agent: one that serves its mandate by courting foreign publishers, offering up only those books from “the national catalogue” that best fit publishers’ lists, and facilitating market-based production by subsidising costs. In short, government cultural deputies today “do not shape or control [culture] but simply deliver it” (ibid., p. 15). And while delivering culture is not as politically innocuous as Flotow makes it sound here (because culture delivered by state agents is the product of internal valuation and selection processes), she accurately describes the game plan many state agents have put in place to maximise their effectiveness in today’s world market for translations: “improved production at home with increased culture budgets, better distribution methods abroad, [...] and changes in the profiles of diplomats to make them culturally informed salespeople” (ibid.). Flanders is no exception here.

Translation Politics: Situating the FLF

Flanders is represented in the world market for translations by the Flemish Literature Fund (FLF), the government organisation tasked with formulating and carrying out its cultural policy in the field of literature. The FLF was founded in 1999 by decree of the Flemish Parliament with a mandate to “support Dutch-language literature and the translation of literary work in the broad sense of the word into and out of Dutch and to improve the socio-economic position of authors and translators” (Anonymous, 1999, p. 4).[8] In its early years, support mainly took the form of subsidies for authors and translators producing for the domestic market, but it has since expanded to include a robust international policy. Today, the FLF divides its resources more or less equally between its “domestic” and “international” cells, which together deploy an integrated support framework spanning all stages of production, from initial creation to outgoing translation and international promotion. In 2016, the FLF employed 18 people, or 15.5 full-time equivalents (FTEs), and had a yearly operational budget of 7.9 million euros, including a 6.5-million-euro endowment from the Flemish Community (Van Bockstal et al., 2017, p. 85). Day-to-day operations are overseen by a director (1 FTE). His team is organised into a general staff for bookkeeping and communication (2.6 FTE), a domestic cell (5.3 FTEs), which administers the fund’s various domestic subsidy schemes and work bursaries for Flemish authors, illustrators, and translators working in(to) Dutch, and an international cell (5.6 FTEs) which handles the fund’s translation grants for foreign publishers and its international promotion efforts (ibid.).[9] All subsidy decisions are made on the recommendation of one of eleven advisory committees, each made up of five members who serve staggered, four-year, non-renewable terms. Six committees are genre-specific (fiction, poetry and essay, children’s and young adult literature, theatre, comics and graphic novels, and non-fiction), four serve various literary support platforms or themes (literary journals, literary events and organisations, author readings, literature and society) and one is dedicated to translations into Dutch. Committee members are recruited from the broader literary field—authors, translators, critics, essayists, academics, publishers—and are tasked with evaluating the literary merits of (proposed) works up for subsidy on the basis of criteria stipulated in the relevant subsidy regulation.

The key criterion for all of the FLF’s various subsidies is literary quality; no application can advance without a positive evaluation on that account. The regulatory definition of literary quality, however, is kept vague—“elements such as style, composition, usage, character development, innovation, suspense, theme and storytelling technique are to be considered” (Van Bockstal et al., 2018a, p. 4)[10]—and committee members arrive at recommendations through intersubjective debate and consensus. Once a recommendation on an application has been reached, it is forwarded to a “decisions college” made up of the heads of each committee and an independent chairperson from the literary field, who together make the final decision. As we will see in the “translation policy” section, the decision-making process for providing translation grants to foreign publishers is somewhat different because additional criteria are in play. In any case, the committees’ initial stamp of literary quality remains an important prerequisite for any eventual international support from the FLF.

How did Flanders come to intervene in the world market for translations? An answer lies in the institutional history of the FLF. Taking my cue from Heilbron and Sapiro, I call out three levels of power here—Flanders (nation), Belgium (state) and the Dutch-language literary field (language area)—and describe how their political, cultural and linguistic contours have converged to give shape to the FLF as we know it today.

The Road to Cultural Autonomy

Cultural policy in Flanders today cannot be separated from the region’s tumultuous political past, particularly as regards language. Since the creation of the Belgian state in 1830, when the southern provinces of the short-lived United Kingdom of the Netherlands seceded with the support of the French, tensions have existed in the country between its Dutch-speaking and French-speaking communities (see Meylaerts, 2007). Language politics played a central role in the constitutional reorganisation of the Belgian state, beginning in the 1960s with the arrival of monolingual, regionalist political parties seeking greater autonomy. This was paired with the splitting of Belgium’s main political parties into Flemish and French-speaking factions. In 1970, as tensions mounted between the two halves of the country and it became clear that differences went far beyond language, the Belgian constitution was revised to recognise the autonomy of the communities and regions and stipulated mechanisms for diffusing power downward to them. It formally acknowledged the cultural particularity of Belgium’s linguistic communities (Flemish, French and the small German-speaking community on the eastern border) and created Flemish and Francophone councils with authority in matters relating to language and culture. The Act of 16 July 1973, known as the Cultural Pact, provides a framework for implementing cultural policies, including advisory committees and councils comprised of cultural sector professionals and representatives from the various political parties and ideological movements active in Belgian society (Janssens et al., 2014).

Cultural policy became an official competency of the Flemish Community upon the establishment of that body in 1980, when the Belgian Parliament passed a devolution bill and amended the constitution as required in the 1970 revision. (Belgium would not officially become a federal state until another constitutional reform in 1993.) The bill created a legislative assembly and government for each language community (Flemish and Francophone) with competencies in culture, language, and educational affairs on the one hand, and a legislative assembly and government for each region (Flanders and Wallonia) with competencies in economic policy on the other. Flanders immediately fused the latter into the former, thus consolidating culture, language, education, and regional economic affairs under a single Flemish Community. Throughout the 1980s and 90s, the Flemish Community further developed its cultural support structures into sector-specific areas: heritage, the artistic disciplines (music, theatre, dance, plastic arts), continuing education, youth, the audiovisual sector, and literature. This period saw a professionalization and modernisation of Flanders’ cultural policy, as well as increased international cooperation (ibid.).

Enter the FLF, which began operations in 2000. Unlike the other sector-specific cultural policy bodies in Flanders (with the exception of the Flanders Audiovisual Fund), the FLF operates outside of the principle of political primacy. That is, its policy and implementation is created and carried out “at an arm’s length” from the government as per a management agreement renewed every five years. The director of the FLF and the chairman of its board report yearly to the Flemish minister for culture on its activities but are otherwise free to formulate and implement policy in the domain of literature within the bounds of its governing decrees and budget.[11]

Neighbours to the North

Flanders has long looked to the Netherlands both as a source of inspiration for its cultural policy with regard to literature, and as an important strategic partner. The two had collaborated for decades previous to the founding of the FLF. However, Flemish-Dutch cooperation before 2000 tended to take an adjunct institutional form: policy was Dutch-led, with Flanders participating in a supporting role and on a fairly ad hoc basis. The first institutional link between Flanders and the Netherlands in the area of literature dates to 1964, when Flanders was formally included in the Foundation for the Promotion of the Translation of Dutch Literary Works (Stichting ter Bevordering van de Vertaling van Nederlands Letterkundig Werk, established in 1954), contributing one-third of the organization's (rather limited) budget (see Heilbron and van Es, 2015, p. 45). Additional groundwork for Dutch-Flemish cooperation in the domains of language policy and literature was laid in 1980 with the founding of the Dutch Language Union (Nederlandse Taalunie), a treaty-based, intergovernmental organisation representing the Netherlands and the Flemish Community with a mandate to jointly promote the Dutch language and its literature in Dutch-speaking areas and abroad. For Flanders, the Union was also a way to strengthen the position of Dutch within a multilingual Belgium and to lend a measure of legitimacy to its fledgling government.

The FLF owes much of its organisational structure and policy toolkit to what is now the Dutch Foundation for Literature (Nederlands Letterenfonds, DFL), a government organisation within the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science created in 2010 by the fusion of two legacy organisations: the Foundation for Literature (Stichting Fonds voor de Letteren, established in 1965) and the Dutch Literary Production and Translation Fund (Nederlands Literair Productie- en Vertalingenfonds, NLPVF, established in 1991). The former aimed to advance the quality and diversity of Dutch and Frisian literature, and literature in Dutch and Frisian translation, by providing work bursaries to Dutch authors and translators. The latter provided grants to foreign publishers for the translation and production of books out of Dutch. These two missions would effectively be transposed into the FLF’s organisational structure as its domestic cell and international cell, respectively.

A strong emphasis on translation, both outgoing and incoming, would become one of two main preoccupations driving official discussions of how to operationalise the FLF’s mandate. From the beginning, there was a clear consensus for combining domestic literary production supports (including support for incoming translation) and support for outgoing translation into a single institution, something the Netherlands would do only in 2010 with the founding of the DFL. As Carlo Van Baelen, the first director of the FLF, put it during a Flemish parliamentary hearing in 2000: “Clearly, we are talking not only about Dutch-language literature, but also translation into and out of Dutch.” This was a mission to be carried out cooperatively,

in maximal collaboration with the Flemish government and with the Dutch literary foundations, which have been working in this field for some time now. [...] We certainly do not want to play a cavalier-seul role and are firm believers in broad cooperation and discussion.”

Vermeulen et al., 2000, p. 4[12]

The FLF currently collaborates closely with the DFL on a number of joint projects including a 19,000-entry database of Dutch literature in translation, translator training and accreditation schemes, and special events like guest-of-honour presentations, most recently at the 2016 Frankfurt Book Fair.

The emphasis on cooperation also belies a second preoccupation: the FLF’s real or perceived underdog status vis-à-vis its neighbours to the north, particularly in terms of the translation and international promotion of its literature. This concern was voiced in the FLF’s earliest days, to return to Van Baelen:

As far as translation is concerned, there is still a lot of catching up to do. Our Flemish literary products are not profiled as such internationally and it is clear that the [FLF] will need to make up for lost ground here.

ibid.[13]

Speaking nearly two decades later, Michiel Scharpé, the current grant manager for fiction, echoes this sentiment:

The DFL, by virtue of its predecessors, has been around much longer, has built up much more, and has much more to show for it. We work closely with our Dutch colleagues but they have a much longer tradition and a much larger apparatus.

2017, n.p.[14]

To wit, the Netherlands launched its outgoing translation support framework in 1991 under the NLPVF and maintains a staff and yearly budget at the DFL that is roughly twice (26 FTEs and 15.1 million euros) that of the FLF (Anonymous, 2017b, pp. 31-32).[15]

The institutional imperative to “catch up” also drives budget decisions. When we set relative staff and budget size alongside other measures of Flemish versus Dutch stakes in the Dutch-language literary field, we see that Flanders appears to invest relatively more than its share in the market. For every euro of public funds allotted to literature in the Low Countries between 2009 and 2016, 30 eurocents went to the FLF and 70 eurocents went the DFL.[16] Compare this with the 22/78 benchmark distribution figure for domestic literary production arrived at by the Dutch Language Union on the basis of data from the Flemish and Dutch segments of the Dutch-language book market (Van Bockstal et al., 2014, p. 47), and the “normal” 27/73 distribution of native speakers of Dutch, and we may conclude that the Flemish Community invests more resources in literary transfer than its Dutch counterpart, relative to the Flemish share of the field. If we look at the budget for the 2016 Frankfurt Book Fair, this becomes even more clear: the project’s 5.6-million-euro price tag was split 43/57 between Flemish and Dutch government funding sources. Temporary staffing for the event’s conception and execution (as well as the official author delegation) was split 50-50 (Van Bockstal et al., 2017).

Flanders’ outsized support for literature appears to be a strategic effort not only to “close the gap” between itself and the Netherlands, as Van Baelen suggested, but also to help overcome structural barriers to access faced by Flemish authors and illustrators. This, to recall the FLF’s mission statement, is part of the organisation’s “market-correcting” mandate. These barriers not only affect literary transfer out of the Dutch-language field and into the world market for translations, where Dutch state and market agents are clearly better positioned. They also affect literary transfer within the Dutch-language literary field: for many (but not all) genres, publishers in Amsterdam are dominant and Flemish authors are obliged to publish their work there, particularly those with international ambitions and those seeking to access the Netherlands’ significantly larger market segment within the Dutch-language field. This is exacerbated by uneven power relations between the variants of Dutch used in Flanders and the Netherlands, respectively. Despite the fact that the two regions share a language and a single dictionary, books published in Amsterdam must conform to Netherlandic Dutch norms, prompting some Flemish authors to self-censor and key down the use of language that could be flagged as “too baroque” or “too regional,” the two most common complaints Dutch editors have about Flemish authors’ style.[17] Intralingual translation in the opposite direction, from Netherlandic Dutch to Flemish Dutch, is virtually non-existent (Brems, 2018).

Perhaps the clearest indication of the compounding of internal and outgoing market barriers facing Flemish authors and illustrators is to be found in the figures on literary export. While generous state support for literature in Flanders has certainly contributed to a vibrant literary scene at home and increased visibility abroad, it has not brought about an increase in Flanders’ relative share of outgoing book translations. In fact, Flemish authors’ share of literary export has shrunk from 30% of the total in 1998 to 20% in 2017 (McMartin, 2019, p. 66). Flemish publishers, too, lost significant ground to their Dutch colleagues, providing 21% of translated titles out of Dutch in 1998 and just 13% in 2018 (ibid.).

In sum, Flanders’ longstanding struggle for cultural autonomy within the Belgian state and its strong but unequal ties to the Netherlands are part and parcel of the FLF’s institutional history. The FLF has its political impetus in the former and its policy impetus in the latter. Both emphasise outgoing translation and international promotion as centrally important aspects of a successful cultural policy for literature. Let us take a closer look at the FLF’s outgoing translation policies now.

Translation Policies: Promoting Flemish Literature Abroad

All of the FLF’s various outgoing policy tools—special events like guest-of-honourships, pitch meetings at book fairs, publishers’ tours, flandersliterature.be, translation grants—are geared toward one target: foreign publishers.[18] Foreign publishers are, in other words, the preferred dissemination vehicle through which the FLF exercises its outgoing policy. As Michiel Scharpé puts it, “everything goes through the foreign publisher—for us, they are the key player” (2017, n.p.).[19] In this sense, the FLF can be seen as an archetype of the new state agent: the nationally embedded, culturally informed facilitator, matchmaker and marketeer to foreign publishers. I would now like to take a closer look at the FLF’s most widely used international policy tool: translation grants. Which languages and genres were most subsidised, and to what strategic aim?

It is important to acknowledge that the FLF’s outgoing translation policies are integrated into a larger strategy of literary talent development, where international promotion is “the last link in a long chain” (ibid.) that begins with cultivating authors and illustrators at home. For many Flemish titles, the first link in that chain is made or broken in an FLF advisory committee. Here, titles are evaluated on their literary merits as part of authors’ initial work bursary applications. By the time a title has found its way to a foreign publisher, it has notched additional links: publication by a Dutch or Flemish publishing house, reception in the Dutch and Flemish press, sales figures, and perhaps even translation out of Dutch into one or more other languages. At this stage, the FLF’s translation grants are designed for one of two scenarios: either a foreign publisher has independently acquired the translation rights to a Flemish title, in which case a translation grant is given, or the publisher has encountered a book through the intervention of one of the FLF’s grant managers, in which case the grant is offered, carrot-like, as part of a pitch. The majority of translations fall in the first category. However, a fair number reach foreign publishers via the targeted outreach of FLF grant managers.

In both cases, the FLF exercises an important quality control function: in return for a translation grant, the foreign publisher must agree to allow the FLF to review its rights and translator contracts and vet its selected translator. If the FLF finds the contracts unsatisfactory or the translator underqualified, the grant is withheld. The FLF is also careful to screen the publishers themselves. Its regulations specifically mention “the status of the publisher” as a criterion to be evaluated as part of a grant application. This criterion is listed second, after the literary quality of the original book and before fair-minded contracts, the quality of the translator and the quality of the translation (Van Bockstal et al., 2018b, p. 2). By “publisher status,” the FLF means “catalogue, speciality, distribution and marketing efforts, special interest in translation, editorial accuracy, etc.” (ibid.).

I argue that these various quality controls also suggest a particular form of capital transfer whereby the FLF itself acts as a mechanism for adding value to a title by ensuring that its outgoing translations are of high quality, the publishers producing them are reputable, and the marketing plans steering their entry into the market are viable (or at least present). This serves to frontload Flemish titles with the largest possible store of transnational capital potential, be it social, symbolic or economic. Furthermore, by working exclusively with publishers “of status,” the FLF also seeks to establish its own name as a well-regarded transnational intermediary, adding to a title’s social capital by association. Here is how the FLF’s Michiel Scharpé puts it:

You have many government agencies or cultural organisations that say, “we need to export our culture. Ah, ok, we have a budget and we’re going to translate books.” And then they are published in large print runs and dropped off at embassies. That is not what we would call professional. To us, professional is: a book should be published by a professional publisher. This is something we want to support, and that is what makes us professional.

2017, n.p.[20]

From the above, I distil two guiding policy goals: to maximise the overall number of translations of literature by Flemish authors and illustrators, and to maximise each individual title’s capital potential. The former is served first and foremost by the FLF’s chosen dissemination vehicle (foreign publishers), which translation grants are designed to assist. The latter is served by the quality controls built into the translation grant mechanism, which frontload translations with as much capital potential as possible.

Both goals are also clearly discernible in the FLF’s decisions about which languages and genres to subsidise. Let us now take a look at the data on FLF-subsidised book translations to see the various ways this bears out. Data were sourced from the freely accessible DFL/FLF translation database (Nederlands Letterenfonds/Dutch Foundation for Literature, n.d.), which, while not exhaustive, is the most complete database for recent literary book translations out of Dutch. In total, 808 entries were included, spanning the period 2000-2016 and encompassing the vast majority of translations that received support from the FLF since it began issuing translation grants in 2000. The FLF offers grants for fiction, non-fiction and children’s and youth titles, which cover up to 60% of translation costs (to a maximum of 4,000 euros); 100% of translation costs are covered for “classic” works from the Flemish canon. Poetry has a second support structure, where subsidies cover all translation costs and 25% of production costs. For picture books, comics and graphic novels, grants cover all translation costs and some costs related to production and promotion. Actual subsidy amounts vary according to the length of the work, but 2,900 euros for fiction and non-fiction titles, 2,500 euros for poetry titles and 1,300 euros for picture books, comics and graphic novels can be taken as approximate averages (Van Bockstal et al., 2017). While it is impossible to say with certainty, we can safely assume that receiving a subsidy played a significant role in many publishers’ decision to publish a Flemish title in translation and thus that many titles in the sample would not have materialised without FLF support.

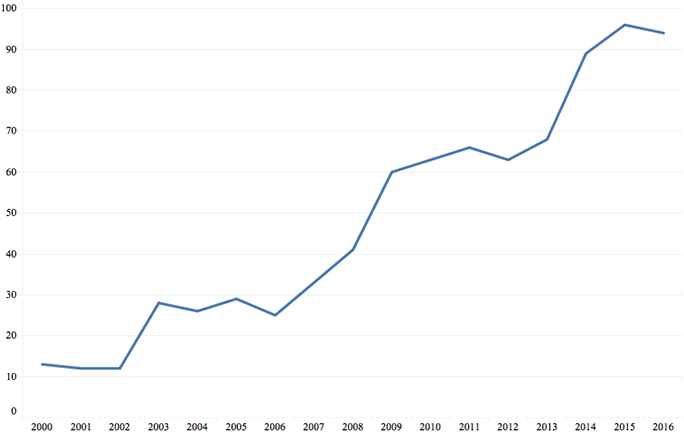

A first observation is that the number of translation grants issued per year has increased dramatically over the course of the FLF’s sixteen-year existence, from just 11 in 2000 to over 90 in 2016 (figure 1). This can be attributed to the simple fact that, prior to the establishment of the FLF, outgoing translation policy was carried out on an ad hoc basis via the now-defunct Ministry of the Flemish Community. The steady rise in the yearly number of translation grants reflects the institutional solidification of the FLF and the gradual fine-tuning and growth of its policy tools.

Figure 1

Distribution of subsidised translations per year over time (all languages)

Periphery to Centre

A more interesting picture begins to emerge when we look at the distribution of subsidised translations by language (figure 2), where it is clear that the FLF favours translations into German, French and English.

Figure 2

Distribution of subsidised translations by language (10 or more titles, 2000-2016)

This, I argue, reflects both a clear dissemination strategy and the systemic realities structuring Flanders’ position in the world market for translations.

Let us start with strategy. The two policy aims discussed above (maximising total translations and maximising each individual translation’s capital potential) are also discernible in the FLF’s decisions about what languages to subsidise. Speaking to the first aim, once a title has been translated into one or more of the three (semi-)central languages, translations into others are much more likely to follow. The FLF was clearly aware of this and identified German, French and English as strategic languages as early as 2005 (Van Baelen, 2006, p. 107).[21] This has a straightforward but important practical aspect: very few acquisitions editors are capable of reading Dutch, however most do have German, French or English. This is also why the FLF (and many other source agents in the market) invests in English samples for titles they would like to see translated. Alongside this practical aspect is a symbolic one, which brings us to the second aim: German, French and English are also the three languages carrying the largest stores of literary capital, to use Casanova’s term (Casanova, 2010, p. 289-290). By facilitating translations into these languages, the FLF thereby contributes to a title’s overall transnational capital potential. Indeed, the FLF actively advertises a title’s translation pedigree, with English, French and German (in that order) at the top of the list, when pitching to prospective publishers in other language markets (McMartin, 2019, p. 133).

And then there are structural aspects. That English comes in at a fairly distant third can be partly explained by its relative imperviousness to incoming translations, as the by-now almost mythical “3%” suggests, and as recent empirical work on Dutch-to-English translation flows bears out (Heilbron and van Es, 2015). The strong showing for French can, in its turn, be linked to the cultural and geographic proximity of France to Flanders, especially via Brussels and Wallonia, and France’s increasing openness to incoming translations, including translations from peripheral literatures (Sapiro, 2008b). Subsidised translations from Dutch into French peaked in 2003, when the Netherlands and Flanders were joint guests of honour at the influential Salon du Livre book fair in Paris (Heilbron, 2008; Voogel and Heilbron, 2012). This event would also be the “motor” behind the hiring of the FLF’s first permanent staff member for international promotion (2017, n.p.). As it happens, subsidised translations into German saw a provisional peak in 2015 and 2016 in the lead-up to another guest of honourship—that of Flanders and the Netherlands at the 2016 Frankfurt Book Fair—showing that guest-of-honour platforms clearly have an impact on presenters’ outgoing translation flows, and that these flows are helped along by translation grants (McMartin, 2016). German’s dominance in the list of subsidised titles can also be explained by Germany’s geographic and cultural proximity to the Low Countries and the extensive network of literary exchange between the two language areas (Wilterdink, 2017).

On the whole, it is striking to see how closely the FLF’s subsidy decisions at the level of language mirror the asymmetric structure of the world-system of translation. This is an indication that a centre-periphery model, which thus far has mainly been used to understand the hegemonic position of English as a language of literary export (cf. Apter, 2001; De Swaan, 2002; Franssen and Kuipers, 2013; Heilbron, 1995, 1999, 2011; Luey, 2001; Mélitz, 2007; Sapiro, 2008b, 2010), can also be used to show the attraction of English, alongside German and French, as languages of literary import. Our case shows that periphery-to-centre transfer is not only happening, it is more prevalent and more handsomely subsidised than transfer to the peripheries.

Picture Books as a Strategic Literary Export

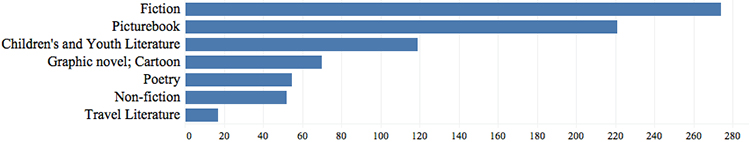

This is not to say that periphery-to-periphery transfer out of Dutch does not occur (see Hacohen, 2014; Pięta, 2016). In fact, the FLF strategically supports and targets translations from Dutch on all counts. In the remaining pages, I would like to briefly discuss one dissemination strategy deployed by the FLF to gain a foothold in new markets on the periphery: translation subsidies for picture books. As before, this dissemination strategy serves the dual policy aims of maximising total translations and maximising each individual translation’s capital potential. To see how this works in the picture book genre, we must first take a closer look at the generic distribution of the FLF’s subsidy choices (figure 3). Fiction (274 titles) and picture books (221) are far and away the two most commonly subsidised genres, followed by children’s and youth literature at a distant third (119), and graphic novels and cartoons (70), poetry (55), non-fiction (52) and travel literature (17) rounding out the list.

Figure 3

Distribution of subsidised translations by genre (all languages, 2000-2016)

The high number of (subsidised) picture books in the sample is grounded, I argue, in strong domestic supply. This is undergirded by Flanders’ excellent tertiary training programme for illustrators, and a thriving domestic publisher landscape in the genre. By all accounts, Flanders’ picture book producers are among the world’s top. But how do grants for picture books stack up in the central languages of German, French and English (figures 4, 5 and 6, next page)?

In all of the central language markets, fiction outranks picture books in terms of translation support. This, I argue, reflects these markets’ status as fully “exploited,” that is, markets in which both state and market agents from the Dutch-language field already have longstanding contacts and for which translation flows at the level of genre have “stabilised” to meet target market demand. In these language markets, more fiction titles receive subsidy than picture books because, simply put, more target publishers are looking to publish translated fiction than picture books.

Figure 4

Distribution of subsidised translations into German, by genre (2000-2016)

Figure 5

Distribution of subsidised translations into French, by genre (2000-2016)

Figure 6

Distribution of subsidised translations into English, by genre (2000-2016)

In “unexplored” language markets (all of which are peripheral according to the core-periphery model), the generic distribution of translation subsidies looks radically different. Take Chinese, for example (figure 7). Here, grants for picture books (43) vastly outnumber grants for fiction (just 1). This reflects a clear dissemination strategy on the part of the FLF to break in to the Chinese market, the idea being that once a foothold has been gained, other genres will follow.

Figure 7

Distribution of subsidised translations into Chinese, by genre (2000-2016)

What is more, as a largely visual medium, picture books do not face the technical and translational challenges commonly encountered in text-rich genres, making them particularly good “travellers”. Michiel Scharpé explains:

If we really want to break into a new region—and we did this for China a few years ago—then we always start with a sort of fact-finding mission: what are [publishers] looking for, how is the market put together? What is out there already, and so forth. At that point, it’s pretty much uncharted territory and we know, for instance, that our picture books always do well because they’re world-class. We have plenty of good literature in all genres but our illustrators are just top-notch, so the quality is there. At the same time, it is a genre that is easy to promote because it’s visual. Normally, you have to paint a picture with words, and the publisher is thinking, “fine, you can tell a story, but is the book really any good, and what is the style?”. With picture books, you can show the illustrations, so that’s another thing. And third, it is a genre that is increasingly in demand, especially in emerging markets like China, where there is more demand and still only a limited supply. [...] So those are three factors that lead us to say: for new markets, picture books almost always work. And once they do, other genres follow.

2017, n.p.[22]

Conclusions

In this article, I endeavoured to give a brief institutional history of the Flemish Literature Fund, situating the organisation in the context of Flanders’ longstanding struggle for cultural autonomy within the Belgian state on the one hand and its strong but unequal ties to the Netherlands on the other, particularly with regard to cultural policy in the area of literature. I went on to investigate one important policy tool—translation grants for foreign publishers—used by the FLF to promote literature by Flemish authors and illustrators abroad. In analysing how this policy is put to use, I identified two strategies of international dissemination: a focus on the central languages of English, German and French, and a focus on picture books as a means to break into new translation markets on the periphery, particularly China. Both serve the FLF’s dual policy goals of maximising total translations of titles by Flemish authors and illustrators, and maximising each individual translation’s capital potential. Clearly, the FLF targets and tailors its outgoing translation policy to foreign publishers, preferring to let publishers do the circulating after controlling for quality and capital potential.

This analysis underwrites characterisations of the shifting relations between state and market agents put forward by Flotow, Heilbron, Sapiro and others and signals, in my view, a particular need for further sociological investigation (and theorisation) at two levels of analysis: language area and agent. What is the situation for homologous agents in different language-specific fields? A comparative, global study of agents situated on the periphery of their respective language-specific fields would provide new insights into relations of dominance within different language areas; of relative measures of autonomy and dependence across language areas; and of various strategies for circumventing barriers to access at levels of power (nation, state, language area) that are subordinate to the transnational. Comparing the present case with that of other stateless nations that pursue active translation policies pertaining to literary export, particularly Quebec and the various autonomous communities of Spain, would be of great interest. From María Sierra Córdoba Serrano (2010), we learn that the majority of books from Quebec that travelled beyond its borders through translation were originally published outside the literary centre in Paris, whereas the vast majority of books by Flemish authors available in translation were originally published in Amsterdam. This would suggest that Quebec is more autonomous within the French language area than Flanders is in the Dutch. Furthermore, the consecration power of the central languages of English, French and German clearly varies from context to context. Córdoba Serrano finds that, “when it is a question of exporting Quebec authors, the French ‘verdict’ continues to be of prime importance (and not for instance, or not so far, the verdict of other literary centers, like the American, British or German)” (ibid., p. 254). For Flemish authors, the German reception tends to be the most crucial, followed by the French and British. (American publishers tend to adopt a “wait-and-see” strategy, cherry-picking only those books that have proven their economic and symbolic potential for translation.) Furthermore, it is clear that proximity (geographic, cultural, institutional, linguistic) also plays an important role in determining relations of dominance and interdependence as both the Quebecois and Flemish cases suggest.

While the “sociological turn” in translation studies has shifted attention to the agents and institutions involved in the production, promotion and circulation of translated books, there is a need to better understand the often significant impact government intervention can exert on the editorial strategies of publishers competing for public funds, on the international careers of state-supported writers, illustrators and translators and on the balance of power between state and market in the world market for translations. This article tried to show one particular state agent’s novel approach to state-supported literary export designed to amplify a small, stateless nation’s international resonance in a world market otherwise dominated by larger (nation-) states and languages.

Appendices

Biographical note

Jack McMartin is a postdoctoral researcher in translation studies at KU Leuven. His doctoral dissertation, Boek to Book (defended in June 2019), investigated contemporary production, circulation and reception contexts of Dutch literature in translation in order to gain insight into the world market for book translations and the institutions, people, and spaces that shape it. He is co-editor of Children’s Literature in Translation: Texts and Contexts (Leuven University Press, forthcoming). He has also published on the life and work of the poet, translator and translation studies scholar James S Holmes.

Notes

-

[1]

For larger, geographically dispersed languages, we can add a fourth type of boundary: “territories” consolidating contiguous, co-lingual states and/or nations into singular markets. For English, these are North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia/New Zealand, respectively. Generally speaking, publishers prefer to claim world English rights, however the original publisher may choose to divide the rights up by territory in order to maximise gains. British publishers usually consider the European continent and former colonies as part of “their” territory, while American publishers have increasingly tried to expand their claim beyond North America to the Pacific. (Uncovered areas are declared “open market.”) The delimitation of territories takes place during the drawing up of the translation rights contract.

-

[2]

The FLF changed its name in March 2017 to Flanders Literature. This article uses the former name throughout because the research reported here took place before the name change.

-

[3]

The FLF was founded on 30 March 1999 and began operations on 1 January 2000.

-

[4]

See https://letterenfonds.secure.force.com/vertalingendatabase/search

-

[5]

For an overview of sociological perspectives on translation, see Wolf (2011).

-

[6]

The main shortcomings of the Index Translationum are by now well known: countries are responsible for submitting their own data and do not always do so systematically and consistently, and UNESCO does not define what constitutes a book, hence some countries report publications such as doctoral dissertations and companies’ annual reports as books. Heilbron is aware of these deficiencies but affirms nonetheless that the database can be used with caution as an indicator of translation flows between languages. The pattern that emerges from his data unambiguously exhibits a core-periphery structure.

-

[7]

The ENLIT network came about at the initiative of Koen Van Bockstal, director of the FLF, and Tiziano Perez, managing director of the DFL, and has its headquarters at the FLF offices in Antwerp.

-

[8]

All translations out of the Dutch are mine. In Dutch: “Het VFL heeft tot doel de Nederlandstalige letteren en de vertaling in en uit het Nederlands van literair werk in de brede zin van het woord te ondersteunen en de sociaal-economische positie van auteurs en vertalers te verbeteren.”

-

[9]

Two additional FTEs were temporarily employed in 2016 as part of the guest-of-honourship at the 2016 Frankfurt Book Fair.

-

[10]

In Dutch: “Literaire kwaliteit wordt beoordeeld op elementen als stijl, compositie, taalgebruik, karaktertekening, inventiviteit, spanning, thematiek en verteltechniek.”

-

[11]

The functioning of the FLF is established by the decree of 30 March 1999 (Anonymous, 1999), the decree of 30 April 2004 amending the establishment decree (Anonymous, 2004), the current organisational code (Anonymous, 2017a), and the specific regulations of each grant type.

-

[12]

In Dutch: “Deze opdracht wensen we te realiseren in een maximale samenwerking met de Vlaamse overheid en met de Nederlandse literaire fondsen die al langer met deze opdracht bezig zijn. [...] We willen zeker en vast geen cavalier-seul spelen en geloven in een brede samenwerking en overleg.”

-

[13]

In Dutch: “Het gaat duidelijk niet alleen om de Nederlandstalige letteren op zich, maar dus ook om vertaling in en uit het Nederlands. Op dit punt is er echter nog heel wat achterstand is in te halen. We zijn in het buitenland immers niet geprofileerd als Vlaamse literaire produkten, en het is duidelijk dat we daar als Fonds een fors inhaalmaneuver zullen moeten opzetten.”

-

[14]

“Het Nederlands Letterenfonds, in welke gedaante dan ook, bestaat al veel langer, heeft al veel meer opgebouwd en heeft toch al veel meer gerealiseerd. We hebben heel veel te maken met onze Nederlandse collega’s maar zij hebben dus een veel grotere traditie en een veel groter apparaat.”

-

[15]

The operating budget of the DFL is set for the period 2013-2016; 15.1 million euros is one third of that three-year budget, which totaled 45.3 million euros.

-

[16]

This figure is calculated on the basis of budget information from the two organizations’ year-end reports.

-

[17]

This claim is based on anecdotal evidence shared by two of Flanders' foremost fiction authors, Stefan Hertmans and Tom Lanoye, at a panel discussion hosted on 26 October 2018 at Ghent University. (Both authors have Dutch publishers.)

-

[18]

In this paper, I limit the focus to outgoing translation grants. I discuss other policy tools in McMartin (2019).

-

[19]

In Dutch: “Alles gaat via de buitenlandse uitgever—voor ons is die de key player.”

-

[20]

In Dutch: “Je hebt heel veel fondsen of culturele instanties die zeggen, ‘wij moeten onze cultuur exporteren. Ah, oké, we hebben een budget en we gaan boeken vertalen.’ En die worden groot gedrukt en die worden aan ambassades afgezet. Dat noemen we bijvoorbeeld niet professioneel. Voor ons is professioneel: een boek moet worden uitgegeven door een professionele uitgever. En dat willen we ondersteunen en daarom zijn we professioneel.”

-

[21]

Interestingly, early FLF policy identified Spanish as a strategic language as well. The year-end report for 2005 states: “We want to shake loose more translations in the big European languages areas (Germany, England, Spain and France) in order to generate as great a secondary effect as possible in other language areas” (Van Baelen, 2006, p. 107). In Dutch: “We willen meer vertalingen losweken in de grote Europese taalgebieden (Duitsland, Engeland, Spanje en Frankrijk), om een zo groot mogelijk secundair effect te genereren naar andere taalgebieden.” Spanish is reiterated again in the 2012 year-end report alongside a new strategic language: Chinese (Van Bockstal, 2013, p. 46).

-

[22]

In Dutch: “Als we echt naar een nieuw gewest gaan, en we zijn een aantal jaar geleden naar China geweest, dan proberen we natuurlijk ook altijd wel eerst een soort van fact-finding mission te doen van: wat zoeken ze, hoe zit die markt in mekaar? Wat is er al, enzovoort, ehm, maar dan is het bijna onontgonnen terreinen en weten we bijvoorbeeld dan dat onze prentenboeken het altijd goed doen omdat onze prentenboeken sowieso van wereldniveau zijn. We hebben heel veel goeie literatuur in alle genres maar onze illustratoren zijn echt wel wereldtop dus je hebt die kwaliteit. Anderzijds is dat een genre dat makkelijk te promoten is omdat dat grafisch is. Want normaal moet je vertellen en moet die uitgever [denken van] ‘wel, ah, die kan goed vertellen maar is die echt wel goed en hoe is die stil?’. Met prentenboek kan je de illustraties tonen dat is dus één. Of, één is die wereldtop en twee is het is gemakkelijk te promoten omdat het grafisch is, en drie is ook: dat is een genre waarin dat in veel van de opkomende markten zoals in China waar er veel vraag naar is en weinig aanbod op de thuismarkt. Dus dat zijn er drie factoren waarom dat wij zeggen: bij nieuwe markten, die prentenboeken, die marcheren bijna altijd. En eens dit gebeurd is, zullen de andere genres volgen.”

Bibliography

- Anderson, Benedict (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections of the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. 2nd ed. London and New York, Verso.

- Anonymous (1999). “Decreet houdende oprichting van een Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren, 17 maart 1999” [Decree on the Founding of the Flemish Literature Fund, 17 March 1999].” Belgian Bulletin of Acts, Orders and Decrees. Numac 1999036057.

- Anonymous (2004). “30 april 2004. Decreet houdende wijziging van het decreet van 30 maart 1999 houdende oprichting van een Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren [30 April 2004. Decree on Amendment to the Decree of 30 March 1999 on the Founding of the Flemish Literature Fund].” Belgian Bulletin of Acts, Orders and Decrees. Numac 2004035972.

- Anonymous (2017a). “Huishoudelijk Reglement van kracht vanaf 25 januari 2017 [Organisational Code in force as of 25 January 2017].” Flemish Literature Fund. [http://www.vfl.be/_uploads/Downloads/downloads/20170125_Huishoudelijk_reglement.pdf].

- Anonymous (2017b). “Jaarverslag 2016 [Year-end Report 2016].” Dutch Foundation for Literature. [http://www.letterenfonds.nl/images/issue_download/Nederlands-Letterenfonds-Jaarverslag-2016.pdf].

- Apter, Emily (2001). “On Translation in a Global Market.” Public Culture, 13, 1, pp. 1-12.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (2008). “A Conservative Revolution in Publishing.” Trans. Ryan Fraser. Translation Studies, 1, 2, pp. 123-154.

- Brandes, Georg (2013 [1899]). “World Literature.” In T. D’haen et al., eds. World Literature: A Reader. London and New York, Routledge.

- Brems, Elke (2018). “Separated by the Same Language: Intralingual Translation between Dutch and Dutch.” Perspectives, 26, 4, pp. 509-524.

- Casanova, Pascale (2004). The World Republic of Letters. Trans. Malcolm B. DeBevoise. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Casanova, Pascale (2010). “Consecration and Accumulation of Literary Capital: Translation as Unequal Exchange.” Trans Siobhan Brownlie. In M. Baker, ed. Critical Readings in Translation Studies. London and New York, Routledge.

- Córdoba Serrano, María Sierra (2010). “Translation as a Measure of Literary Domination: The Case of Quebec Literature Translated in Spain (1975-2004).” MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, 2, pp. 249-281.

- De Swaan, Abram (2002). Words of the World: The World Language System. Cambridge, Polity Press.

- English, James F. (2005). The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Flotow, Luise von (2007). “Telling Canada’s ‘Story’ in German: Using Cultural Diplomacy to Achieve Soft Power.” In L. von Flotow and R. M. Nischik, eds. Translating Canada. Charting the Institutions and Influences of Cultural Transfer: Canadian Writing in German/y. Ottawa, University of Ottawa Press.

- Franssen, Thomas (2015). “Book Translations and the Autonomy of Genre-subfields in the Dutch Literary Field, 1981-2009.” Translation Studies, 8, 3, pp. 302-320.

- Franssen, Thomas and Giselinde Kuipers (2013). “Coping with Uncertainty, Abundance and Strife: Decision-making Processes of Dutch Acquisition Editors in the Global Market for Translations.” Poetics, 41, 1, pp. 48-74.

- Greco, Albert (1989). “Mergers and Acquisitions in Publishing, 1984-1988: Some Public Policy Issues.” Book Research Quarterly, 5, 3, pp. 25-44.

- Greco, Albert (1999). “The Impact of Horizontal Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Concentration in the US Book Publishing Industry: 1989-1994.” Journal of Media Economics, 12, 3, pp. 165-180.

- Hacohen, Ran (2014). “Literary Transfer between Peripheral Languages: A Production of Culture Perspective.” Meta, 59, 2, pp. 297-309.

- Häfner, Anne-Kathrin (2018). “Book Markets.” [https://www.buchmesse.de/en/international/book_markets/].

- Heilbron, Johan (1995). “Nederlandse vertalingen wereldwijd. Kleine landen en culturele mondialisering [Dutch Translations Worldwide. Small Countries and Cultural Globalisation].” In J. Heilbron et al., eds. Waarin een klein land. Nederlandse cultuur in internationaal verband [In a Small Country. Dutch Culture in an International Context]. Amsterdam, Prometheus.

- Heilbron, Johan (1999). “Towards a Sociology of Translation. Book Translations as a Cultural World-System.” European Journal of Social Theory, 4, 2, pp. 429-444.

- Heilbron, Johan (2008). “Responding to Globalization: The Development of Book Translations in France and the Netherlands.” In A. Pym et al., eds. Beyond Descriptive Translation Studies: Investigations in Homage to Gideon Toury. Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

- Heilbron, Johan (2011). “De weg naar wereldroem [The Path to World Fame].” In C. Bringreve, et al., eds. Cultuur en Ongelijkheid. Diemen, Uitgeverij AMB.

- Heilbron, Johan and Gisèle Sapiro (2007). “Outline for a Sociology of Translation. Current Issues and Future Prospects.” In M. Wolf and A. Fukari, eds. Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

- Heilbron, Johan and Nicky van Es (2015). “Fiction from the Periphery: How Dutch Writers Enter the Field of English-Language Literature.” Cultural Sociology, 9, 3, pp. 296-319.

- Heilbron, Johan and Gisèle Sapiro (2016). “Translation: Economic and Sociological Perspectives.” In V. Ginsburgh and S. Weber, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Economics and Language. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hesmondhalgh, David (2007). The Cultural Industries. 2nd ed. London, Sage.

- Janssens, Joris et al. (2014). “Country Profile Belgium.” Commissioned report. Brussels. Council of Europe/ERICarts Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe, 15th ed.

- Luey, Beth (2001). “Translation and the Internationalization of Culture.” Publishing Research Quarterly, 16, 4, pp. 41-49.

- Mélitz, Jacques (2007). “The Impact of English Dominance on Literature and Welfare.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 64, pp. 193-215.

- Meylaerts, Reine (2007). “‘La Belgique vivra-t-elle?’ Language and Translation Ideological Debates in Belgium (1919-1940).” The Translator, 13, 2, pp. 297-319.

- Moeran, Brian (2010). “The Book Fair as a Tournament of Values.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 16, pp. 138-154.

- Moeran, Brian and Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen, eds. (2011). Negotiating Values in the Creative Industries. Fairs, Festivals and Competitive Events. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Mossop, Brian (1988). “Translating Institutions: A Missing Factor in Translation Theory.” TTR, 1, 2, pp. 65-71.

- McMartin, Jack (2016). “Transnational Pole Coherence and Dutch-to-German Literary Transfer: A Study of Book Translations Published in the Lead-Up to the Guest of Honourship at the 2016 Frankfurt Book Fair.” Journal of Dutch Literature, 7, 2, pp. 50-72.

- McMartin, Jack (2019). Boek to Book: Flanders in the Transnational Literary Field. PhD dissertation. KU Leuven. Unpublished.

- Nederlands Letterenfonds/Dutch Foundation for Literature (n.d.). Translation Database. [https://letterenfonds.secure.force.com/vertalingendatabase/search].

- Pięta, Hanna (2016). “On Translation Between (Semi-)Peripheral Languages: An Overview of the External History of Polish Literature Translated into European Portuguese.” The Translator, 22, 3, pp. 354-377.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2008a). “Translation and the Field of Publishing: A Commentary on Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘A Conservative Revolution in Publishing’.” Translation Studies, 1, 2, pp. 154-166.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2008b). Translatio: Le marché de la traduction en France à l’heure de la mondialisation. Paris, CNRS Editions.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2010). “Globalization and Cultural Diversity in the Book Market: The Case of Literary Translations in the US and in France.” Poetics, 38, pp. 419-439.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2012a). “Editorial Policy and Translation.” In Y. Gambier and L. van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies. Vol. 3, Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2012b). “Strategies of Importation of Foreign Literature in France in the Twentieth Century. The Case of Gallimard, or the Making of and International Publisher.” In S. Helgesson and P. Vermeulen, eds. Institutions of World Literature. Writing, Translations, Markets. London and New York, Routledge.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2015). “Translation and Symbolic Capital in the Era of Globalization: French Literature in the United States.” Cultural Sociology, 9, 3, pp. 320-346.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2016). “How Do Literary Works Cross Borders (or Not)? A Sociological Approach to World Literature.” Journal of World Literature, 1, pp. 81-96.

- Scharpé, Michiel (30 November 2017). Interview with Jack McMartin. Berchem.

- Thompson, John B. (2012). Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Industry in the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Polity Press.

- Van Baelen, Carlo (2006). “Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren Jaarverslag 2006 [Flemish Literature Fund Year-end Report 2006].” Bergem, Flemish Literature Fund. [http://www.vfl.be/_uploads/Downloads/downloads/VFL_JAARVERSLAG_2006.pdf].

- Van Baelen, Carlo (2013). 1+1=zelden 2. Over grensverkeer in de Vlaams-Nederlandse literaire boekenmarkt [1+1=rarely 2. On Crossborder Traffic in the Flemish-Dutch Literary Book Market]. Commissioned report. Amsterdam, Nederlandse Taalunie [Dutch Language Union].

- Van Bockstal, Koen et al. (2013). Jaarverslag 2012 [Year-end Report 2012]. Journal of Dutch Literature, 7, 2, pp. 50-72.

- Van Bockstal, Koen et al. (2014). Landschapstekening Letteren [Landscape of the Literary Field]. Commissioned report. Bergem, Flemish Literature Fund. [https://www.kunstenloket.be/sites/default/files/upload/document/file/landschapstekening_etteren.pdf].

- Van Bockstal, Koen et al. (2017). Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren Jaarverslag 2016 [Flemish Literature Fund Year-end Report 2016]. Bergem, Flemish Literature Fund. [http://www.vfl.be/_uploads/Downloads/downloads/VFL_jaarverslag_2016___spread.pdf].

- Van Bockstal, Koen et al. (2018a). Werkbeurzen Literaire Auteurs Subsidiereglement 2018 [2018 Subsidy Regulations for Work Bursaries for Literary Authors]. Bergem, Flemish Literature Fund. [http://www.vfl.be/_uploads/Downloads/downloads/Reglement_werkbeurzen_voor_literaire_auteurs_2018.pdf].

- Van Bockstal, Koen et al. (2018b). Translation Grants Guidelines 2018. Berchem, Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren. [https://s3-eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/files-flandersliterature-be/www.flandersliterature.be/production/documents/Translation%20grants%20guidelines%202018.pdf].

- Vermeulen, Jo et al. (2000). Verslag van de hoorzitting op 4 juli 2000 in het kader van de bespreking van de ontwerp-overeenkomst Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren [Minutes of the parliamentary hearing of 4 July 2000 on the proposed governing agreement for the Flemish Literature Fund]. Brussels, Commission for Culture, Media and Sport, Flemish Parliament. [http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=1015785].

- Voogel, Marjolijn and Johan Heilbron (2012). “Comment faire découvrir une littérature inconnue: Les traductions du néerlandais en France.” In G. Sapiro, ed. Traduire la littérature et les sciences humaines: conditions et obstacles. Paris, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication/DEPS.

- Wilterdink, Nico (2017). “Breaching the Dyke. The International Reception of Contemporary Dutch Translated Literature.” In E. Brems et al., eds. Doing Double Dutch. The International Circulation of Literature from the Low Countries. Leuven, Leuven University Press.

- Wolf, Michaela (2011). “Mapping the Field: Sociological Perspectives on Translation.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 207, pp. 1-28.

List of figures

Figure 1

Distribution of subsidised translations per year over time (all languages)

Figure 2

Distribution of subsidised translations by language (10 or more titles, 2000-2016)

Figure 3

Distribution of subsidised translations by genre (all languages, 2000-2016)

Figure 4

Distribution of subsidised translations into German, by genre (2000-2016)

Figure 5