Abstracts

Abstract

Research on the ecology, biodiversity and toxicology of cyanobacteria in Moroccan inland waters has been carried out since 1994. The results demonstrate the existence of several taxa of cyanobacteria. Most of them are toxic, bloom‑forming species present in various water bodies of the country. The present study follows upon this earlier work and spans the 2003-2006 period. The major aim was to update and supplement the existing national cyanobacteria inventory and to isolate new toxic strains. During the study period, more than 40 aquatic environments were visited and sampled.

Almost 300 taxa of cyanobacteria were recorded. They belonged to 3 orders, 14 families and 46 genera. Among these, about 78 taxa are recorded for the first time in Morocco; 29 strains of cyanobacteria were successfully isolated and cultured in the laboratory. All the collected cyanobacteria, including natural blooms, mats, and cultured strains, were analyzed for toxicity and hepatotoxins (microcystins) were quantified. Using the High-performance liquid chromatography technique coupled to photodiode array (PDA) detector (HPLC-PDA), four samples of Microcystis blooms showed the presence of microcystins (MCs), with a concentration ranging between 1.87 and 64.4 µg•g‑1 MC‑LR eq (microcystin-LR equivalents). A total of five different structural variants of MCs were detected (MC-LR, -RR, -YR, -FR, -WR). Furthermore, 3 of 29 isolates were confirmed as MCs producing strains.

The results show that the widening of the survey led to a better knowledge of the diversity of cyanobacteria. The taxonomic inventory was greatly increased and several cyanobacteria strains were characterized for their toxicity. The results should be useful as a database for the identification of various aquatic environments contaminated by cyanobacterial toxins (microcystins), which represent a potent sanitary risk for human and animals.

Key words:

- Cyanobacteria,

- taxonomy,

- microcystins,

- blooms,

- isolates,

- inland waters,

- Morocco

Résume

Au Maroc, les recherches sur l’écologie, la biodiversité et la toxicologie des cyanobactéries des eaux continentales ont été entamées à partir de 1994. Les résultats obtenus ont montré l’existence de plusieurs taxons de cyanobactéries, dont certains sont responsables de la formation de blooms toxiques. Faisant suite aux précédents travaux, la présente étude, réalisée lors de la période 2003-2006, où plus de 40 milieux aquatiques ont été prospectés, a pour objectif de compléter et d’actualiser l’inventaire national des cyanobactéries d’eau douce du Maroc et d’isoler de nouvelles souches toxiques.

Plus de 300 taxons de cyanobactéries appartenant à 3 ordres, 14 familles et 46 genres ont été inventoriés. À notre connaissance, 78 taxons sont cités pour la première fois au Maroc et 29 souches de cyanobactéries ont pu être isolées et cultivées en laboratoire. Le matériel cyanobactérien planctonique ou benthique collecté sur le terrain (blooms, écumes, films benthiques, etc.) et la biomasse des souches isolées produite en culture au laboratoire, ont été analysés pour l’évaluation de la toxicité et la quantification des cyanotoxines (microcystines).

L’utilisation de la technique HPLC-PDA (High-performance liquid chromatography technique coupled to photodiode array (PDA) detector) a permis d’identifier quatre blooms toxiques à Microcystis et la détection de microcystines (MCs) à des concentrations variant entre 1,87 et 64,4 µg•g‑1 eq MC-LR (microcystin-LR equivalents). Cinq variantes structurales de MCs ont pu être détectées (MC-LR, -RR, -YR, -FR, -WR). Parmi les 29 souches isolées et produites au laboratoire, trois seulement ont confirmé la production de microcystines.

Les résultats obtenus constituent un apport substantiel à la taxonomie des cyanobactéries et à l’évaluation de la biodiversité des cyanobactéries du Maroc. Ces données peuvent être utilisées comme base pour identifier les milieux aquatiques potentiellement contaminés par les cyanobactéries et capables de générer un haut risque sanitaire pour les hommes et les animaux.

Mots clés:

- Cyanobactéries,

- taxonomie,

- microcystines,

- blooms,

- souches isolées,

- eaux continentales,

- Maroc

Article body

1. Introduction

Cyanobacteria (Prokaryotic blue green algae or cyanoprokaryotes) occur especially in freshwater and brackish environments, but may be found also in marine and terrestrial ecosystems. They may dominate the phytoplankton of lakes and rivers, forming respectively blooms and mats, when environmental conditions are appropriate for their growth (OLIVER et GANF, 2000).

Cyanobacteria have received growing attention as producers of a diverse array of biologically active natural products. Some of these compounds have potential biotechnological uses (THAJUDDIN et SUBRAMANIAN, 2005) and others, called “cyanotoxins”, appear to be toxic and pose a hazard to many organisms, including humans, who contact, ingest or use water contaminated by theses toxins (CODD et al., 2005, a review). Cyanotoxins include potent hepatotoxins, neurotoxins, cytotoxins, irritants or gastrointestinal toxins (WIEGAND et PFLUGMACHER, 2005, a review). Among hepatotoxins, the microcystins (MCs) are the best documented. Until now more than 75 natural MCs structural variants have been characterized (CODD et al., 2005, a review).

Over 100 species of cyanobacteria belonging to 40 genera are reported to be toxic (JAYATISSA et al., 2006). Microcystis is the most frequent bloom-forming cosmopolitan genus (CARMICHAEL, 1996).

The problem of massive proliferation of cyanobacteria seems more accentuated in temperate zones, known by a remarkable diversity. In these areas, cyanobacterial blooms are most prominent during late summer and early autumn. In Mediterranean regions and subtropical areas, the bloom season may start earlier and persist longer (COOK et al., 2004).

Benefiting from its subtropical geographical situation, Mediterranean climate and two maritime frontages, Morocco has a mosaic of naturally diversified aquatic ecosystems, in addition to more than 100 reservoirs. This great heterogeneity of habitats and biotopes offers varied ecological conditions leading to a rich and diversified micro-flora. Moreover, previous works, although relatively limited in time and space, revealed the presence of an un‑negligible cyanobacterial microflora. Since then, the national taxonomic list of cyanobacteria has increased, following the appearance of new taxonomic records in recent limnological studies (LOUDIKI et al., 2002).

Cyanobacteria blooms are common in some freshwater bodies used for recreation and/or as drinking water reservoirs. This is likely the result of a rapid eutrophication due to high nutrient loads and semi-arid climate factors (LOUDIKI et al., 2002 ; OUDRA et al., 2001a).

In Morocco, it is only in 1994 that a research program on diversity of cyanobacteria was started when many cyanobacteria bloom-forming species have been identified and studied. These results confirmed that Morocco, like other countries in the world, was affected by massive proliferation of toxic cyanobacteria (LOUDIKI et al., 2002 ; OUDRA et al., 2001a ; SABOUR et al., 2002, 2005 ; SBIYYAA et al., 1998).

This work, especially in its taxonomic part, represents a substantial addition to the North African and Mediterranean previous studies, which remain often limited (ABDEL‑RAHMAN et al., 1993 ; ABOAL et PUIG, 2005 ; ALBAY et al., 2003 ; BOUAÏCHA et NASRI, 2004 ; COOK et al., 2004 ; OUDRA et al., 2001a ; PRATI et al., 2002 ; SABOUR et al., 2002 ; VASCONCELOS et al., 2001).

The Moroccan taxonomic inventory of cyanobacteria remains relatively limited. Our study, which spans over the period between March 2003 and September 2006, aims firstly to extend the investigation to other and new aquatic environments and to update and supplement the existing cyanobacteria inventory, secondly, to isolate new cyanobacterial strains and thirdly, to assess their potent toxicity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Sites description and sampling

More than 40 various aquatic environments (10 natural lakes, 19 reservoirs, 3 lagoons and estuaries, 15 streams and rivers, etc.) including fresh and salted waters have been sampled. The choice of sites was based essentially on their trophic conditions and ecological importance. Some sites have biological and ecological interest, called SIBES (as Sebkha Zima, Dayèt Aoua, Assif Ait Mizane, Massa estuary, etc.) or are Ramsar sites (as Daya Sidi Boughaba, Al Massira reservoir, etc.). Other sites are used for drinking water production reservoirs (as Al Massira, Mansour Eddahbi, Youssef ben Tachfine, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah, etc.) and /or are agricultural and recreational waters (as Lalla Takerkoust reservoir, etc.). These sites are located in different Moroccan hydrographic basins (32 00 N, 5 00 W), under various climatic conditions, at various altitudes and characterized by different trophic status. The sampling was done between 2003 and 2006 each time, at the summer and early autumn period, corresponding to the phases of massive cyanobacteria proliferation blooms and generally to the peak of cyanobacterial biomass.

In reservoirs and lakes, the sampling of planktonic cyanobacteria was done using a 37 µm mesh phytoplankton net. In the running waters (streams, rivers, channels, etc.), the sampling was carried out either using a 37 µm mesh net with handle or by scraping benthic species attached to various substrates (blocks, stones, sediments, vegetation, etc.).

The cyanobacteria bloom‑forming were collected in three reservoirs: Lalla Takerkoust (TAK), Al Massira (ALM), Mansour Eddahbi (MED) and from two natural lakes: Dayèt Erroumi (DE) and Tigalmamines (TI). Whereas, the cyanobacteria mat‑forming were collected in two streams: Oued Ourika (OUR) and Oued Oukaïmeden (OK). For some localities like TAK, OUR and OK, the sampling was realized several times according to the cyanobacteria bloom occurrences. In order to supplement the laboratory culture collection with more cyanobacteria strains, 29 isolates, planktonic or benthic, coming from 24 different water bodies, were isolated and cultured in laboratory conditions.

2.2 Taxonomic study

The taxonomic identification of the species was carried out under the light microscope. Species were observed, measured, and identified using several specialized cyanobacteria taxonomic books (KOMÁREK et ANAGNOSTIDIS 1999, 2005 ; STARMACH, 1966). Identification was based on morphologic criteria such as form of cells (width, length), filaments or colonies, their mucilaginous envelopes, coloration, pigmentation and mode of cell division.

2.3 Cyanobacteria isolation and strain culture conditions

Z8 medium (KOTAI, 1972) was used for the isolation and culture of cyanobacteria. Cultures were maintained at 25 °C ± 2 °C, at a light intensity of 82•µE•m‑2•S‑1 fluorescent continuous light and with a light/dark cycle of 16h/8h. The cyanobacterial biomass produced was harvested at the end of the exponential growth phase by flotation, centrifugation or filtration through a 37 µm pore net filter. The concentrated material was freeze‑dried and stored at -20 °C prior to toxicity assessment and MCs detection and quantification.

2.4 Toxicity assessment, detection and quantification of hepatotoxins (microcystins)

2.4.1 Mice bioassay

Cyanobacteria mammals’ toxicity was measured by intra-peritoneal (i.p) mouse bioassay, using 18-22 g male white Swiss mice. The method was already described by OUDRA et al. (2001b). Briefly, a determined mass of lyophilized cyanobacteria material was suspended in 0,9% NaCl. The obtained physiological solution was injected into pairs of mice per each dose level. Animal behaviour, toxicity symptoms and survival time were registered. After death, animals were autopsied internally for signs of hepatotoxicity (hemorrhagic shock, liver swelling, etc.). The toxicity was evaluated as LD50 (mg•kg‑1 dry weight) determination (LD50 : Lethal dose for 50% mortality of tested animals). By the mice bioassay, the toxicity of three kinds of samples was evaluated: three natural cyanobacteria bloom-forming (TAK, ALM, MED), three natural cyanobacetria mat-forming (Nos. M., Lyn. A1, Lyn. A2) and two isolated cyanobacteria strains laboratory cultures (Pseud. C. S24., Pseud. G. S25).

2.4.2 Artemia salina bioassay

Cyanobacteria Crustacean toxicity was determined and evaluated by Artemia salina test only for four kinds of cyanobacterial samples, including natural blooms and strain cultures (Mic. A. TAK, Mic. A. MED, Mic. A. ALM, Mic. W. Ti). The method was already described by SABOUR et al. (2005). Briefly, the dried brine shrimp eggs were purchased from special stores. The larvae (8-20 in, each well of a multi well microtiter plate) were used in the tests 24 h after hatching. Toxic fractions were pre-purified from 75% methanol extracts by using an activated Octadecyl Silane - ODS gel cartridge. The toxicity of cyanobacterial fractions to Artemia salina larvae was tested in natural seawater, in loosely covered micro-plates at 25 °C ± 2 °C. The test results were expressed as percentage of dead and 24 h‑LC50 (lethal concentration (µg dry weight•mL‑1), for 50% of the tested animals), calculated by EPA Probit Analysis Program (Version 1.5).

2.4.3 Cyanotoxins (MCs) extraction

All collected cyanobacteria materials including blooms, mats and laboratory cultures, were subjected to hepatotoxins analysis (detection of hepta-peptide microcystins). Lyophilized biomass was extracted with 70% aqueous methanol (2 mg DW•mL‑1) and dried by rotary evaporation at 45 ºC. Two extract types were obtained as follows: 1) a concentrated extract, by extracting twice the biomass with 150 µL of 70% methanol and 2) a dilute extract, by extracting with 500 µL of 70% methanol, the residue of the biomass extracted with the said 300 µL. This procedure ensures total recovery of MCs. All extracts were filtered through a 1.2 µm GF/C glass filter before being subjected to HP a photodiode array detector.

2.4.4 Microcystins HPLC-PDA analysis

Chromatographic analysis was performed by HPLC Waters equipment (model 2695) with a photodiode array detector (model 996). The column used was Chromolith C18 (250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5µm.). The mobile phase system was: a) H2O + 0.05% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and b) Acetonitrile (MeCN) + 0.05% (v/v) TFA. A linear gradient of 30 to 70% for a) and 30 to 100% for b). The volume injected was 100 µL or 50 µL, as advisable, and the mobile phase run at 1 mL•min‑1. MCs were identified on the basis of their UV‑spectra at 238 nm and retention time. Standard MC-LR, -YR, -RR, -LF and -LW were purchased from Calbiochem (Germany). MC-FR and -WR were purified in the Autonomous University of Madrid laboratory. Other MCs different from the ones said earlier were quantified using microcystin-LR as a standard. All the chemicals used were of chromatographic grade (Scharlau Chemie Barcelona, Spain).

3. Results

3.1 Cyanobacterial biodiversity

Following the examination of the various existing cyanobacteria records in Moroccan waterbodies, the resulting inventory counted 377 taxa (DOUMA et al., 2004). This analysis allowed the extension of the list quoted by LOUDIKI et al. (2002), in which the total number of taxa inventoried at the time was 150. The additional survey allowed the inventory of 299 taxa, of which 78 species (26% of the total taxa) were observed for the first time in Morocco and belonged to 31 different genera. 54% of inventoried new taxa are among the 8 dominating genus which are: Phormidium, Lyngbya, Leptolyngbya, Pseudanabaena, Geitlerinema, Gloecapsopsis, Oscillatoria, Synechocystis (Table 1).

Table 1

New taxa inventoried for the first time in Moroccan inland waters.

Nouveaux taxons inventoriés pour la première fois dans les eaux continentales du Maroc.

|

Achroonema macromeres Sku. Anabaena oscillarioides Bory. Aphanocapsa conferta (W. et G.S. We.) Leg.et Cro. Aphanocapsa hyalina (Lyn.) Han. Aphanothece smithii Len. et Cron. Arthrospira maxima Set. et Gar. Chroococcopsis gigantea Geit. Chroococcus obliteratus Rich. Coelosphaerium kutzingianum Näg. Cyanobacterium minervae (Cop.) Kom. Cyanonephron styloides Hick. Cyanothece aeruginosa (Näg.) Kom. Geitlerinema acus (Cop.) An. Geitlerinema bigranulatum Tiw. Geitlerinema lemmermannii (Wol.) An. Gloecapsopsis dvorakii (Nov.) Kom. et An. Gloecapsopsis pleurocapsoides (Nov.) Kom. et An. Gloeocapsopsis magma (Bréb.) Kom. et An. Homoeothrix juliana (Born. et Flau.) Kir. Homoeothrix margalefii Kom. et Kal. Hormoscilla spongeliae Gom. Hormoscilla xishaensis Hu. Jaaginema homogeneum (Frém.) An. et Kom. Jaaginema unigranulatum (Bis.) An. Leptolyngbya faveolarum (Rab.) An. et Kom. Leptolyngbya benthonica (Sku.) An. Leptolyngbya boryana An. et Kom. |

Leptolyngbya ercegovici (Cado) An. et Kom. Leptolyngbya fragilis (Gom.) An. et Kom. Leptolyngbya lurida (Gom.) An. et Kom. Limnothrix guttulata (Van Goor) Ume. et M. Wat. Limnothrix obliqueacuminata (Skuj.) Mef. Limnothrix pseudovacuolata (Uter.) An. Limnothrix rosea (Uter.) Meff. Lyngbya biebliana Clau. Lyngbya confervoides C. Ag. Lyngbya nigra Ag. Lyngbya semiplena J. Ag. Lyngbya stagnina Kütz. Nostoc Punctiforme (Kütz.) Har. Oscillatoria acuminata Geit. et Rut. Oscillatoria nigra Ag. et Kut. Oscillatoria ornata Kütz. Pascherinema moniliforme (Pas.) De Ton. Phormidiochaete balearica (Born.e Flau.)Kom. Phormidiochaete nordstedtii Kom. et Kan. Phormidium alaskense Gom. Phormidium bekesiense (I. Kiss) K. Kiss Phormidium bohneri Schm. Phormidium bulgaricum (Kom.) Kom. et An. Phormidium chalybeum ( Mer.) An. et Kom. Phormidium chungii Gar. Phormidium fonticolum Kütz. Phormidium kolkwitzii Kom. |

Phormidium lacustre (Cad.) An. Phormidium lusitanicum Samp. Phormidium paulsenianum (Boy.) Nov. Phormidium rosea (Skuj.) An. Phormidium simplicissimum (Gom.)An.et Kom. Phormidium stagninum (Kütz. ex Gom.) An. Phormidium tergestinum An. Phormidium versicolor Wart. Pseudanabaena biceps Bour. Pseudanabaena lonchoides An. Pseudanabaena moniliformis Kom. Pseudanabaena papillaterminata Kuk. Pseudanabaena starmachii An. Pseudocapsa sphaerica (Pro.) Kov. Romeria chlorina Böch. Schizothrix calcic la Gom. Spirulina nordstedtii Gom. Symploca cavernarum Cop. Synechococcus sciophilus sku. Synechocystis crassa Vorn. Synechocystis endobiotica Elen. et Holl. Synechocystis minuscule Vorn. Synechocystis pevalkii Erc. Woronichinia naegeliana (Ung.) Elen. |

For many taxa (123), the taxonomic identification was stopped at the generic level. These taxa were also taken into account in the total national inventory, which currently counts 578 taxa (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Specific richness evolution of cyanobacteria in Moroccan inland waters.

Évolution de la richesse spécifique des cyanobactéries dans les eaux intérieures du Maroc.

The taxa listed in this study (299) were distributed in 3 orders, 14 families and 46 genera. Oscillatoriales constituted the more diversified order with 73% of the totality of taxa, followed by Chroococcales (17%) and Nostocales (10%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Spectrum of the orders of cyanobacteria inventoried in Moroccan inland waters.

Répartition des ordres de cyanobactéries dans les eaux intérieures marocaines.

This study enabled us to describe wild strains considered toxic or potentially toxic in literature reports. However, other strains were found to be toxic for the first time in our work.

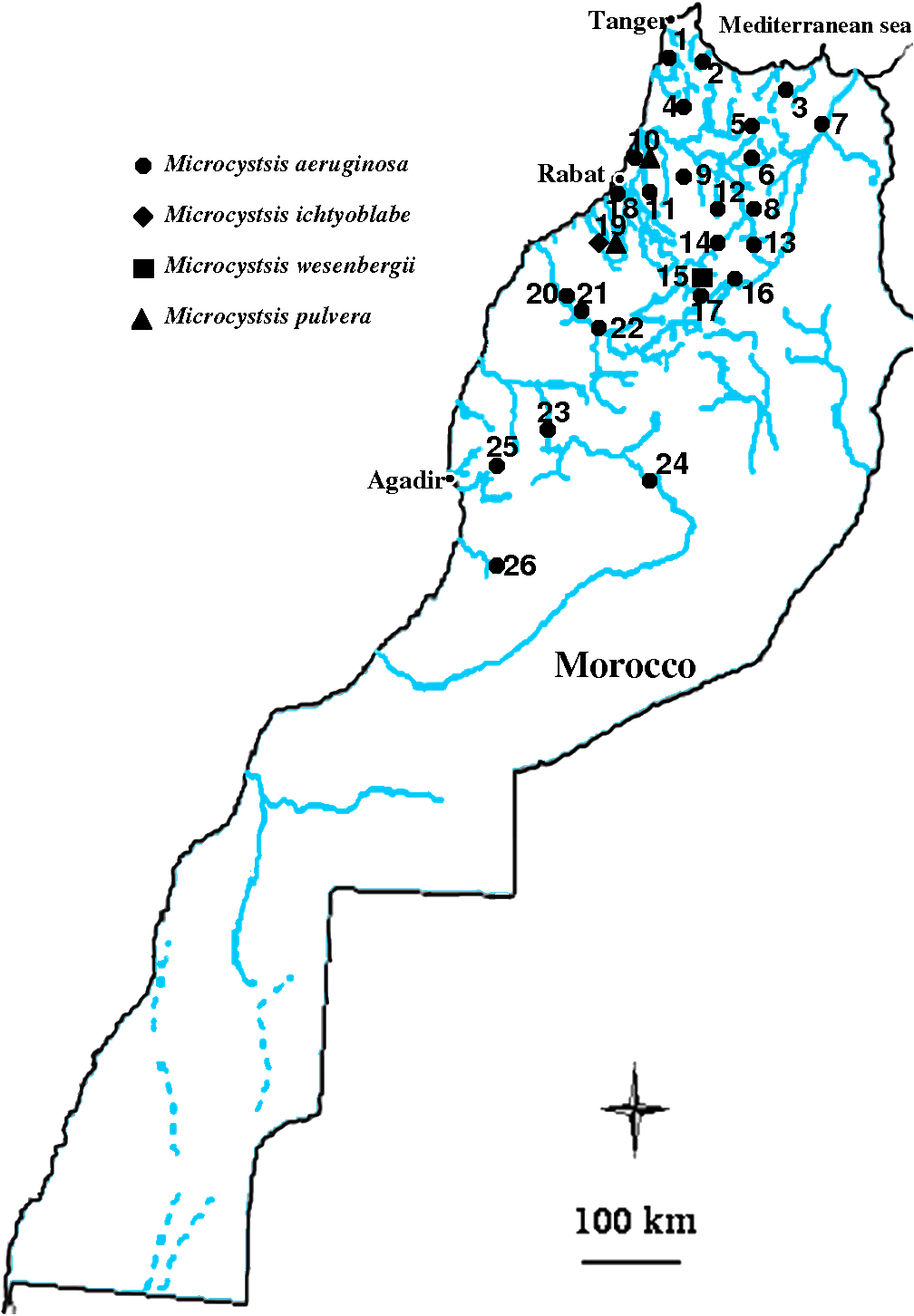

Table 2 gives the geographical distribution of all these toxic strains in the Moroccan territory. It appears that Microcystis is the predominant phytoplanctonic bloom-forming genus. We present here a mapping of its distribution in some waterbodies (Figure 3). In addition, table 2 reveals the presence of two filamentous species (Nostoc muscorum and Lyngbya attenuata), which are responsible for mat‑forming in some particular aquatic ecosystems (particularly in stream ecosystems).

Table 2

Distribution of toxic and potentially toxic cyanobacterial strains in some Moroccan inland waters that were surveyed.

Distribution des souches toxiques et potentiellement toxiques dans certains milieux hydriques continentaux marocains prospectés.

SPECIES |

RESERVOIRS |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

AB |

AM |

EK |

IB |

IM |

KT |

LT |

ME |

NAK |

OE |

SM |

SMBA |

YBT |

|

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

|

* |

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

* |

Coelosphaerium naegelianum Ung. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

Gomphosphaeria aponina Kütz. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

Lyngbya birgei G. M. Smit. |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

Microcystis aeruginosa (Kütz.) Kütz. |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

* |

|

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

Microcystis flos-aquae (wit.) Kirch. |

* |

|

|

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

|

|

* |

|

Phormidium formosum (Bor.) An. et Kom. |

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Planktothrix agardhii (Gom.) An. et Kom. |

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

Planktothrix isothrix (Skuj.) Kom. et Koma. |

* |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

Pseudanabaena catenata Laut. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

Pseudanabaena galeata Böch. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pseudanabaena mucicola Nau. et Hub. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schizothrix calcicola Gom. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Woronichinia naegeliana (Ung.) Elen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NATURAL LAKES |

||||||||||||

AA |

AF |

AW |

DA |

DE |

IF |

IFR |

SBG |

SZ |

TI |

||||

Anabaena spiroides Kleb. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|||

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|||

Microcystis aeruginosa (Kütz.) Kütz. |

* |

* |

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

|||

Microcystis flos-aquae (wit.) Kirch |

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Microcystis wesenbergii (Kom.) Kom. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|||

Phormidium formosum (Bor.) An. et Kom. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

|||

Pseudanabaena galeata Böch. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|||

|

RIVERS AND ESTUARIES |

||||||||||||

AMI |

BR |

MAS |

OK |

OTE |

OUR |

||||||||

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

|

* |

* |

|

|

|

|||||||

Nostoc muscorum Ag. |

* |

|

|

* |

|

* |

|||||||

Phormidium formosum (Bor.) An. et Kom. |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|||||||

Pseudanabaena biceps Bour. |

|

|

|

|

|

* |

Reservoirs : |

AB : Abdelmoumen ; AM : Al Massira ; EK : El Kansera ; IB : Ibn Batouta ; IM : Imfout ; KT : Kasba Tadla ; LT : Lalla Takerkoust ; ME : Mansour Eddahbi ; NAK : Nakhla ; OE : Oued El Makhazine ; SM : Smir ; SMBA : Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah ;YBT : Youssef Ben Tachfine. |

Natural lakes : |

AA : Aguelmam Azigza ; AF : Aguelmam Afourgah ; AW : Aguelmam Wiwane ; DA: Dayet Awa ; DE : Dayet Erroumi ; IF : Dayet Iffer ; IFR : Dayet Ifrah ; SBG: Merja de Sidi Boughaba ; SZ : Sebkha Zima ; TI : Tiguelmamines. |

Rivers and estuaries : |

AMI : Oued Aït Mizane ; BR : Bou Regreg estuary ; MAS : Estuaire Massa ; OK : Oued Oukaimden ; OTE: Oued Tensift OUR: Oued Ourika |

Figure 3

Geographic localisation of some Moroccan reservoirs, natural lakes and ponds where Microcystis strains have been inventoried.

Localisation géographique des réservoirs, des lacs naturels et des étangs où des souches de Microcystis ont été inventoriées.

Reservoirs:

1- Ibn Battouta, 2- Smir, 3- M.B.A. Khettabi, 4- O. El Makhazine, 5- Sahela, 6- Mohammed V, 7- Idriss I, 8- Allal El Fassi, 9- Elkansera, 18- S. M. Ben Abdellah, 19- Oued Mellah, 20- Al Massira, 21- Imfout, 22- Daourat, 23- Lalla Takerkoust, 24- M. Eddahbi, 25- Abdelmoumen, 26- Y.B. Tachfine.

Natural lakes and ponds:

10- Sidi Boughaba, 11- Dayèt Erroumi, 12- Dayèt Aoua, 13-Dayèt Affourgah, 14- Dayèt Iffrah, Dayèt Aoua, Dayèt Iffrah, 15- Aguelmane Azigza, 16- Aguelmane Sidi Ali, 17- Tiguelmamines.

The diversity of the cyanobacteria is especially remarkable in the reservoirs (47% of the total specific richness), whereas, in natural lakes and the plain rivers, the biodiversity is respectively about 26% and 17% (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Distribution of inventoried cyanobacteria by type of aquatic biotope.

Distribution des cyanobactéries inventoriées selon les différents types de biotopes aquatiques.

3.2 Toxicological assessment and microcystins detection

The cyanobacteria taxonomic study was supplemented by a toxicological assessment leading to approve the toxicity of the collected cyanobacteria material both by mice and Artemia bioassays. Forty-two samples, among which 29 isolates, planktonic or benthic, coming from 24 different waterbodies, were analyzed for toxicity and/or detection of cyanobacterial hepatotoxins microcystins (MCs) (Table 3).

Table 3

Toxicological data of tested cyanobacteria (isolates, mats, blooms) in various Moroccan inland waters.

Données toxicologiques des cyanobactéries testées (isolats, blooms, films benthiques) dans divers milieux hydriques continentaux marocains.

|

Sampling Date |

Locality |

|

Toxicity |

HPLC Species |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Mouse bioassay LD50 (mg DW•kg‑1) |

Artemia assay LC 50•24 h‑1 (μg•mL‑1) |

Content (μg•g‑1 eq MC‑LR) |

Microcystins profile ratio |

Blooms |

07‑2003 |

L.Takerkoust |

Mic. A. TAK |

176,8 |

1 414 |

13,94 |

RR (14), LR (16,6), FR (23,1) WR (46,4) |

10‑2004 |

M. Eddahbi |

Mic. A. MED |

352 |

1 712 |

64,4 |

RR (41,3),YR (21,7), LR (33,7), FR (1,1), WR (2,3) |

|

07‑2004 |

Al Massira |

Mic. A. ALM |

829 |

4 343 |

9,9 |

LR (100) |

|

10‑2004 |

Dayèt Erroumi |

Mic. A. ER |

- |

- |

1,87 |

RR (15,3) XZ* (8,2) LR (3,6) FR (20,3) WR (52,6) |

|

Mats |

10‑2004 |

Tiguelmamines |

Mic. W. Ti |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D |

06‑2003 |

Oued Ourika |

Nos. M. OUR |

119,5 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

06‑2003 |

Oued Ourika |

Lyn. A1 |

742 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

06‑2003 |

Oued‑Oukaimeden |

Lyn. A2 |

1 450 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

Isolates |

07‑2003 |

L.Takerkoust |

Mic. A. S13 |

- |

- |

9,44 |

RR (62), YR (2,6), LR (6,7) FR (7,9), WR (20,8) |

08‑2005 |

M. Eddahbi |

Plank. A. S22 |

- |

- |

3,19 |

RR (100) |

|

12‑2004 |

Oued Ourika |

Pseud. B. S23 |

- |

- |

0,28 |

XZ* (100) |

|

07‑2003 |

L.Takerkoust |

Pseud. C. S24 |

1 192,7 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

06‑2003 |

Lac Zima |

Pseud. G. S25 |

292,8 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

* : Unknown MC variant, N.D. : Not detected

Plank. A. S22: Planktothrix agardhii; Pseud. B. S23: Pseudanabaena biceps ; Pseud. C. S.24: Pseudanabaena catenata; Pseud. G. S.25: Pseudanabaena galeata ; Mic. A. Tak, ALM, ER : Microcystis aeruginosa; Lyn. A1,2 : Lyngbya attenuata ; Nos. M. OUR : Nostoc Muscorum. Mic. W. Ti : Microcystis wesembergii. TAK: L. Takerkoust; ALM : Al Massira; MED : Mensou Eddahbi: OUR: Oued Ourika; OK: Oued Oukaimeden; LZ : Lac Zima; TI: Tiguelmamine.

3.2.1 Cyanobacteria “in situ” forming natural blooms and mats

As it was well indicated in table 3, the toxicity determined as LD50 values for the Microcystis phytoplanktonic cyanobacteria blooms (Mic. A. TAK, Mic. A. MED and Mic. A. ALM) were respectively 176.8 mg•kg‑1 DW, 352 mg•kg‑1 DW and 829 mg•kg‑1 DW. However, the mat-forming cyanobacterial, OUR mats (Nos. M., Lyn. A1) and OK mat (Lyn. A2) were respectively 119.5 mg•kg‑1 DW, 742 mg•kg‑1 DW and 1,450 mg•kg‑1 DW (Table 3). During mice bioassays, both for the Microcystis forming blooms and Nostoc or Lyngbya forming mats, the survival time (1 to 4 h) and poisoning signs are similar to those observed for Microcystins hepatotoxicity.

For the three Microcystis natural blooms occurring at TAK, ALM and MED reservoirs, the toxicity was also evaluated by 24 h LC50 Artemia biotest. The obtained values of 24 h LC50 were respectively, 1.41 mg•mL-1 , 1.71 mg•mL‑1 and 4.34 mg•mL-1 for the TAK, MED and ALM blooms.

For these collected natural bloom samples, the HPLC analysis revealed a clear difference of both for MCs content and variants composition, with a concentration of total MCs ranging between 1.87 and 64.4 µg•g‑1 eq MC-LR (Table 3).

3.2.2 Cyanobacteria isolates strains (culture)

Twenty‑nine cyanobacteria strains belonging to the genera Phormidium, Pseudanabaena, Leptolyngbya, Microcystis, Synechocystis, Planktothrix, Oscillatoria, Lyngbya, Limnothrix, Jaaginema, Geitlerinema, Cyanobacterium and Anabaenopsis were isolated from natural samples collected from various waterbodies (reservoirs, lakes, rivers, streams, estuaries, irrigation channels, basins) (Table 4). Twelve strains were planktonic collected in the open water, forming or not scum or bloom. Seventeen are benthic collected from substrate such as gravel, mud in rivers, on the banks of reservoirs or attached to other filamentous species (Table 4).

Table 4

Isolated cyanobacteria strains screened for microcystin detection, sampling sites, type of biotope and sample characteristics.

«Screening» des souches isolées : détection de microcystins, sites échantillonnés, type de biotope, caractéristiques d’échantillons.

Strains code |

Species |

Sampling site / type of biotope / date |

Characteristic of the strain in original sample |

|---|---|---|---|

S1 |

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

Bou Regreg / Estuary / 07‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S2 |

Anabanopsis circularis Gayr. |

Sidi Bou Rhaba / Estuary / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S3 |

Cyanobacterium minervae (Cop.) Kom |

Palmeraie / Bassin, Marrakech / 06‑2003 |

In the water mass |

S4 |

Geitlerinema lemmermannii.Tav. |

Benslimane / Daya ( temporary lac) / 10‑2004 |

Attached to ground submerged or not by water |

S5 |

Jaaginema sp. |

Azigza / Lac / 11‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks or with other filamentous species |

S6 |

Leptolyngbya faveolarum (Rab.) An. et Kom. |

Sidi Bou Rhaba / Lac / 07‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks reservoir or with other filamentous species |

S7 |

Leptolyngbya boryana An. |

Safi / Reservoir / 08‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks reservoir |

S8 |

Leptolyngbya lurida (Sku.) An. |

Ourika / Stream / 11‑2006 |

Attached to substrate of the edge of the stream |

S9 |

Leptolyngbya sp. |

Sebkha Zima / Lac / 07‑2005 |

Attached to other filamentous species |

S10 |

Limnothrix rosea (Ute.) Mef. |

Oued Tassaout / River / 06‑2004 |

Attached to gravels in the calm zones of river |

S11 |

Lyngbya hieronymusii Lemm. |

Imfout / Reservoir / 07‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks or with other filamentous species |

S12 |

Microcystis wesembergii. (Kom.) Kom. |

Tigelmamines / Lac /10‑2005 |

Float on the surface of the water mass forming scum or bloom |

S13 |

Microcystis aeruginosa(Kütz.) Kütz. |

L. Takerkoust / Reservoir/ 07‑2003 |

Float on the surface of the water mass forming scum or bloom |

S14 |

Oscillatoria limosa Ag. |

My. Youssef / Reservoir / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass and other filamentous species |

S15 |

Phormidium articulatum Clau. |

Bouznika / River / 10‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S16 |

Phormidium chalybeum (Mer.ex Gom.) An. et Kom. |

Bouznika / River / 10‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S17 |

Phormidium Koprophilum (Sku.) An. |

Oued Mellah / River / 07‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S18 |

Phormidium lusitanicum Sam. |

Oued Cherat / Benslimane / 07‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S19 |

Phormidium paulsenianum (Boy.) Nov. |

Oued Mellah / River / 07‑2004 |

Attached to substrate of the edge of the river with other filamentous species |

S20 |

Phormidium sp. |

ElKansera / Reservoir / 10‑2005 |

Attached to other filamentous species forming floating mats |

S21 |

Phormidium subfuscum Kütz. |

Sidi Daouad / Canal, Marrakech / 10‑2004 |

Attached with other filamentous on the edge of canal |

S22 |

Planktothrix agardhii(Gom.) An. et Kom. |

M. Eddahbi / Reservoir/ 10‑2004 |

Float on the surface of the water mass forming scum or bloom |

S23 |

Pseudanabaena biceps Bour. |

Ourika / Stream / 11‑2005 |

Attached to substrate of the edge of the stream |

S24 |

Pseudanabaena catenata Laut. |

L. Takerkoust / Reservoir / 07‑2003 |

In the water mass and other filamentous benthic species |

S25 |

Pseudanabaena galeata Böch. |

Lac Zima / Lac / 07‑2003 |

Attached to other filamentous species forming floating mats |

S26 |

Pseudanabaena lonchoides An. |

M. Eddahbi / Reservoir / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S27 |

Pseudanabaena papillaterminata Kuk. |

M. Eddahbi / Reservoir / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S28 |

Synechocystis minuscula Vorn. |

Azigza / Lac / 10‑2005 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S29 |

Synechocystis salina Wis. |

Bou Regreg / estuary / 07‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

Among all isolated strains, two showed a positive toxicity (Pseud. C. S24 and Pseud. G. S25) with respective LD50 of 292.8 mg•kg‑1 DW and 1,192.7 mg•kg‑1 DW. After i.p mice bioassay, the observed poisoning signs are similar to those observed with Microcystis, MCs producing extract, except for the strain (Pseud. G. S25), which present severe diarrhea and a longer survival time (5 to 7 h), more than one to two hours specific for hepatotoxins. Although the positive mice biotest, the HPLC-PDA analysis showed a negative result for detecting MCs in both isolated strains (Pseud. C. S24 and Pseud. G. S25), whereas, for the three others (Mic. TAK. S13, Plank. A. S22 and Pseud. B. S23) are confirmed as MCs producers with a detection of five MCs variants (see Table 3 for details). According to HPLC-PDA results, only three strains, Mic. TAK. S13, Plank. A. S22 and Pseud. B. S23, among the 29 tested species, are confirmed as MCs producers.

4. Discussion

The widening of the survey in various Moroccan aquatic environments allows a thorough knowledge of the diversity of cyanobacteria. The priority to evaluate the potential risk of these micro-organisms led us to couple survey with toxicological assessment of blooms and/or mats and isolated strains.

4.1 Cyanobacterial biodiversity

The taxonomic richness of cyanobacteria was remarkably increased (Figure 1). This is due to several factors like the diversity of the Moroccan aquatic environments and the widening of the study scale, in the context of the research program on toxic cyanobacteria initiated in the last years.

The predominance of taxa of Oscillatoriales (Figure 2) in these aquatic environments is not a surprise because several works all over the world already indicated this predominance, often in mesotrophic or eutrophic waterbodies (BRANCO et al., 2003 ; MUR et al., 1999 ; SCHEFFER et al., 1997). Microcystis genus is the most common taxon in all lakes and reservoirs of Morocco (LOUDIKI et al., 2002). Other species of cyanobacteria are cosmopolitan and are frequent in fresh waters and mineralized water.

In lakes and reservoirs (Figure 4), it seems that the stability of water column and nutrient increasing input are in favour of higher biodiversity and cyanobacteria massive proliferation. In contrast, in streams and mountain springs, the diversity of the cyanobacteria is relatively low (12%) with the predominance of some particular genera forming often mat (Nostoc, Lyngbya).

4.2 Toxicological assessment

4.2.1 Cyanobacteria bloom or mat‑forming

The toxicity and cyanobacterial toxins (MCs) content of natural blooms and mats have been analyzed in several Moroccan freshwaters. The positive toxicity and detection of MCs were obtained in three reservoirs: Lalla Takerkoust, Mansour Eddahbi and Almassira, and in the natural lake Dayet Erroumi. In all these localities, although the M. aeruginosa is the predominant species responsible for blooms, the toxicity determined both by mice and Artemia bioassays, is different (Table 3). With respect to bloom toxicity level and according to classifications suggested by Lawtonet al., (1994) ; Mic. A. TAK bloom exhibiting an LD50 = 176.8 mg•kg‑1 is highly toxic and both for Mic. A. MED (LD50 = 352 mg•kg‑1) and Mic. A. ALM blooms (LD50 = 829 mg•kg‑1) are moderately toxic.

The toxicity of the Mic. A. TAK and Mic. A. MED bloom could be regarded as higher than that of a bloom from the brackish Moroccan Oued Mellah lake (LD50 = 502 mg•kg‑1), whose dominant species was Microcystis ichtyoblabe (SABOUR et al., 2002).

According to the mouse biotest, the Mic. A. ALM bloom was only moderately toxic (829 mg•kg‑1). The toxicity is about six times lower than that observed (142 mg•kg‑1) in a Microcystis bloom from the same reservoir in 1999 (OUDRA et al., 2001b). The toxicity dissimilarity could be attributed to the difference in the growth phase of the bloom and also to the environmental conditions during blooms occurrence. To this respect, SABOUR et al. (2002), while studying Microcystis bloom in Oued Mellah reservoir, observed a change in the mouse LD50 from 518 to 1924 mg•kg‑1, corresponding respectively to the exponential and decline growth phase of the bloom. During the decline growth phase, most of the MCs should be detected in the water, since these toxins are released to the medium after cell disruption. The highest toxicity reported corresponds to a M. aeruginosa bloom from the Lalla Takerkoust reservoir (OUDRA et al., 2002a).

A similar highly variable toxicity in Microcystis blooms from a Mediterranean reservoir has been reported for Kastoria lake, in Greece, with a LD50 ranging from 40 to 1,500 mg•kg‑1 (COOK et al., 2004). In other cases, as in Portugal, in a previous work carried out during 1989-1992, the studied blooms, dominated by Microcystis, had a LD50 remaining lower than 700 mg•kg‑1 (VASCONSELOS, 2001).

According to the Artemia biotest, the Mic. A. TAK, Mic. A. MED and Mic. A. ALM blooms are classified as toxic. But a significant difference between them is observed, 24‑h LC50 = 1.41 mg•mL‑1 for Mic. A. TAK bloom, 24‑h LC50 = 1.71 mg•mL‑1 for Mic. A. MED bloom and 4.34 mg•mL‑1 for Mic. A. ALM bloom.

As with the mouse bioassay, these toxicity values are higher than those previously reported for the Microcystis bloom in Oued Mellah reservoir, 24‑h LC50 of 6‑46 mg•mL‑1 (SABOUR et al., 2002).

In general, our results with Artemia bioassay clearly confirm that this bioassay can be used as an alternative test to evaluate cyanobacteria toxicity.

MCs concentration in Mic. A. TAK, Mic. A. MED, Mic. A. ALM and Mic. A. blooms were 64.4, 13.94, 9.9 and 1.87 µg•g‑1 eq MC-LR respectively.

The MCs concentration in all blooms is higher than that observed before in the ALM (OUDRA et al., 2001b) and Oued Mellah (SABOUR et al., 2002) reservoirs. However, the content is very low compared with that reported for Microcystis blooms of diverse origins such as the Moroccan Lalla Takerkoust lake (8.8 mg•g‑1, OUDRA et al., 2001a), various Portuguese reservoirs (1-7.1 mg•g‑1; VASCONCELOS, 2001), the Spanish Santillana reservoir (13.5 mg•g‑1; PADILLA et al., 2006) and some French reservoirs (0.07-3.97 mg•g‑1, VEZIE et al., 1997).

The toxicity evaluation by mouse biotest of mat-forming N. Muscorum (Nos. M) and L. attenuata (Lyn. A1,2) in Ourika and Oukaïmeden streams was positive (Table 3). The symptoms were also similar to those of hepato-toxicosis. In one of these mats, MCs were detected (Table 2). This could be explained by the presence of small quantities undetectable by HPLC or the presence of other types of toxins. Indeed, for a sample of Nostocmuscurum bloom collected in April, 1999 from OK stream, the MCs concentration was about 229.4 µg, equivalent MC-LR•g‑1 DW and an LD50 of 125 mg•kg‑1 (OUDRA et al., 2008). Over the world, a few studies related to benthic toxic cyanobacteria that could be cited (HITZFELD et al., 2000 ; IZAGUIRRE et al., 2007 ; MEZ et al., 1998 ; OUDRA et al., 2008 et ZAKARIA et al., 2006). According to Zakariaetal. (2006), these benthic cyanobacteria could produce anatoxins, saxitoxins or microcystins.

With respect to MCs characterization, the cyanobacterial natural bloom shows a net difference in composition: the ALM bloom producing only MC-LR is the less diversified one, whereas the TAK bloom presents four MCs variants and the most diversified blooms are MED and DE Microcystis blooms with five MCs variants (Table 3).

The predominance of hydrophobic variant MC‑WR (known as slightly toxic) in Mic. A. TAK bloom and Mic. A. MED bloom constitutes an exceptional case, not only for the studied reservoirs but also for Morocco and, to our knowledge, for the Mediterranean region.

The predominance of MC-RR over the other variants has been reported for M. aeruginosa in the Philippines (CUVIN-ARALAR, 2002). Predominance of MC‑LR, MC‑RR and MC‑YR was also reported for some countries of the Mediterranean region, like Egypt (ABDEL-RAHMAN et al., 1993), Morocco (OUDRA et al., 2001a), Portugal (VASCONSELOS, 2001), Spain ( PADILLA et al., 2006) and Algeria (NASRI et al., 2004).

The presence of only one variant of MCs in Mic. A. ALM bloom suggests that several toxic cyanobacteria often contain one major toxin. They may also contain several other toxins but in minor quantities (HARADA et al., 1991 ; SHIRAI et al., 1991). In Portugal, microcystin LR is usually the major toxin with a dominance ranging from 45.5 to 99.8% (VASCONCELOS, 2001).

The predominance of a variant may be related to the difference in strain composition dominating the bloom because microcystin-producing and non-producing strains can coexist in populations of cyanobacteria (ROHRLACK, 2001 ; KURMAYER et al., 2002 ; VEZIE et al., 1998).

4.2.2 Cyanobacteria isolate strains

The results obtained show that Pseud. G. S25 strain has a relatively high toxicity (292.8 mg•kg‑1 DW) while Pseud. C. S24 strain reveals a medium toxicity (1,192.74 mg•kg‑1).

In spite of their hepatotoxicity, MCs were not detected by HPLC in Pseud. C. S24 or Pseud. G. S25 strains. This can be explained by the presence of small undetectable quantities of MCs or other types of cyanotoxins. In fact, a species morphologically similar to Pseud. G. S25, determined as Pseudanabaena galeata, which was already isolated from the experimental wastewater stabilisation ponds of Marrakech, was confirmed as MCs producer (OUDRA et al., 2002b).

In addition, the mat‑forming Pseud. B. S23 strain, isolated from a High‑Atlas stream, was identified for the first time as a MCs producer strain in Morocco. The complete HPLC‑MS characterization of the unknown microcystin variants is in progress. Related to producing toxins amount, MCs content in the Mic. TAK. S13 strain (9.44 µg•g‑1 eq MC‑LR) was about three times higher than in the Plank. A. S22 strain (3.19 µg•g‑1 eq MC‑LR) and about 34 times than in Pseud. B. S23 (0.28 µg•g‑1 eq MC-LR) (Table 3).

The comparison of the diversity of MCs in Mic. A. TAK bloom and their isolated strains, shows the appearance of MC‑YR variant under normal conditions of culture at the laboratory. The variation of the percentage (quotas) and type of MCs is related to the conditions of the culture medium. MC-YR was already observed in Mic. A. TAK bloom (OUDRA et al., 2002a). These results indicate that blooms have the potential to contain these toxins or others. However, the Plank. A. S22 strain produced only one variant (MC‑RR). This strain is known for the production of MC‑RR and demethylmicrocystins variants (FASTNER et al., 1998 ; MESSINEO et al., 2006 ; SIVONEN et JONES 1999).

Though no sign of toxicity or presence of toxins was revealed, the strains S1-S12, S14-S21, S26-S29 remain potentially toxic, knowing that some of them are already known as toxic such as S1‑S12. This observation is supported by the fact that we tested only the cultures when it is often observed that blooms are more toxic. Culture conditions (temperature, nutrients, trace metals, etc.) can act on the strains nature and on their toxinology (KOTAK et al., 2000).

Only a genetic approach of some natural strain isolates can reveal this potential in order to draw up, firstly, a red list of the high-risk zones likely to have a proliferation of the toxic cyanobacteria, and secondly, to exploit biotechnologically the non‑toxic strains.

5. Conclusion

The taxonomic study provided a recent, updated and relatively complete national inventory of the cyanobacteria, whose current number is now 578 taxa described for the first time in Morocco. Genetic analysis is necessary to determine their taxonomic identity. These results constitute a primary database for the establishment of a national cyanobacteria culture collection in Morocco.

The toxicological results show the presence and the toxicity of the MCs in four natural Microcystis blooms and three isolates. Five MCs variants are detected.

Further research, focused on the presence of other variants of cyanobacterial toxins, seems necessary. In this direction, a future approach will focus on the detection of the toxigenic genes.

This study has the merit to bring additions to previous knowledge and to map toxic strains that can generate harmful effects on human and environmental health. Thus, it could be very useful for any Moroccan water quality monitoring and sanitary risk survey program.

Appendices

Acknowledgments

The cyanotoxins (MCs) analyses by HPLC-PDA were funded by the Moroccan government and the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation AECI (Bilateral Spain-Morocco Project A/011422/07 granted to Profs F.F. Del Campo and B. Oudra).

This work was financially supported by an Excellence Grant N° 03-008/2004, accorded to Douma Mountasser by the National Center of Scientific and Technical Research (CNRST) - Minister of National Education, Higher Education, Staff Training and Scientific Research, Morocco.

We are thankful to unknown reviewers for helping us to improve the manuscript rather considerably.

References

- ABDEL-RAHMAN, S., Y.M. EL-AYOUTY and H.A. KAMAEL (1993). Characterization of heptapeptide toxins extracted from Microcystis aeruginosa (Egyptian isolate). Comparison with some synthesized analogs. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res., 41, 1-7.

- ABOAL, M. and M.-A. PUIG (2005). Intracellular and dissolved microcystins in reservoirs of the river Segura basin, Murcia, SE Spain. Toxicon, 45, 509-518.

- ALBAY, M., R. AKCAALAN, H. TUFEKCI, J.S. METCALF, K.A. BEATTIE and G.A. CODD (2003). Depth profiles of cyanobacterial hepatotoxins (microcystins) in three Turkish freshwater lakes. Hydrobiol., 505, 89-95.

- BOUAÏCHA, N. and A.-B. NASRI (2004). First report of Cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii from Algerian freshwaters. Environ. Toxicol., 19, 541-543.

- BRANCO, L.H.Z., A.N. MOURA, A.C. SILVA and M.C. BITTENCOURT-OLIVEIRA (2003). Biodiver-sidade e considerações biogeográficas das Cyanobacteria de una area de manguezal do estado de Pernambuco. Brasil. Act. Bot. Bras., 17, 585-596.

- CARMICHAEL, W.W. (1996). Toxic Microcystis and the environment. In : Toxic Microcystis. K.H. HARADA, W.W. CARMICHAEL et H. FUJIKI (Editors), CRC Press, Boca Raton, USA, pp. 1-11.

- CODD, G.A., L.F. MORRISON and J.S. METCALF (2005). Cyanobacterial toxins: risk management for health protection. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 203, 264-272.

- COOK, C.M., E. VARDAKA and T. LANARAS (2004). Toxic cyanobacteria in Greek freshwaters, 1987-2000: Occurrence, toxicity, and impacts in the Mediterranean region. Act. Hydrochim. Hydrobiol., 32, 107-124.

- CUVIN-ARALAR, M.L., J. FASTNER, U. FOCKEN, K. BECKER and E.V. ARALAR (2002). Microcystins in natural blooms and laboratory cultured Microcystis aeruginosa from laguna de Bay, Philippines. Syst. Appl. Microbiol., 25, 179-182.

- DOUMA, M., M. LOUDIKI, B. SABOUR, B. OUDRA and K. MOUHRI (2004). Biodiversité des cyanobactéries des écosystèmes aquatiques du Maroc : Inventaire et distribution géographique. Dans : Actes du Colloque International sur la gestion et la préservation des ressources en eau « CIGPRE ». Meknès, Maroc, pp. 33.

- FASTNER, J., M. ERHARD, W.W. CARMICHAEL, F. SUN, K.L. RINEHART, H. RONICKE and I. CHORUS (1999). Characterization and diversity of microcystins in natural blooms and strains of the genera Microcystis and Planktothrix from German freshwaters. Arch. Hydrobiol., 145, 147-163.

- HARADA, K.I., K. OGAWA, Y. KIMURA, H. MURATA, M. SUZUKI, P.M. THORN, W.R. EVANS and W.W. CARMICHAEL (1991). Microcystins from Anabaena flos-aquaeMRC-525-17. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 4, 535-540.

- HITZFELD, B.C., S.J. HÖGER and D.R. DIETRICH (2000). Cyanobacterial toxins: removal during drinking water treatment and human risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect., 108, 113-122.

- IZAGUIRRE, G., A.D. JUNGBLUT and B.A. NEILAN (2007). Benthic cyanobacteria (Oscillatoriaceae) that produce microcystin-LR, isolated from four reservoirs in southern California. Water Res., 41, 492-498.

- JAYATISSA, L.P., E.I.L. SILVA, J. MCELHINEY and L.A. LAWTON (2006). Occurrence of toxigenic cyano-bacterial blooms in freshwaters of Sri Lanka. Syst. Appl. Microbiol., 29, 156-164.

- KOMÁREK, J.K. and K. ANAGNOSTIDIS (2005). Cyano-prokaryota: Oscillatoriales. BÜDEL, B., L. KRIENITZ, G. GÄRTNER and M. SCHAGERL (Editors), Susswasserflora von Mitteleuropa, 19/2, 759 p.

- KOMÁREK, J.K. and K. ANAGNOSTIDIS (1999).Cyano-prokaryota: Chroococcales. H. Ettl, G. Gärtner, H. Heynig and D. Mollenhauer (Editors), Sübwasserflora von Mitteleuropa, 19/1, 548 p.

- KOTAI, J. (1972). Instructions for preparation of modified nutrient solution Z8 for algae. Norwegian Institue for Water Research, Blindem, Oslo, B-11/69, 5 p.

- KOTAK, B.G., A.K.Y. LAM, E.E. PREPAS and S.E. HRUDEY (2000). Role of chemical and physical variables in regulating microcystin-LR concentration in phytoplankton of eutrophic lakes, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 57, 1584-1593.

- KURMAYER, R., E. DITTMAN, J. FASTNER and I. CHORUS (2002). Diversity of microcystin genes within a population of the toxic cyanobacterium Microcystis spp. in lake Wannsee (Berlin, Germany). Microb. Ecol., 43, 107-118.

- LAWTON, L.A., K.A. BEATTIE, S.P. HAWSER, D.L. CAMPBEL and G.A. CODD (1994). Evaluation of assay methods for the determination of cyanobacterial hepatotoxicity. In : Detection methods for Cyanobacterial toxins. CODD, G.A., T.M. JEFFRIES, C.W. KEEVIL and E. POTTER (Editors). The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, U.K, pp. 111-116.

- LOUDIKI, M., B. OUDRA, B. SABOUR, B. SBIYYAA and V. VASCONCELOS (2002). Taxonomy and geographic distribution of potential toxic cyanobacterial strains in Morocco. Ann. Limnol., 38, 101-108.

- MESSINEO, V., D. MATTEI, S. MELCHIORRE, G. SALVATORE, S. BOGIALLI, R. SALZANO, R. MAZZA, G. CAPELLI and M. BRUNO (2006). Microcystin diversity in a Planktothrix rubescens population from Lake Albano (Central Italy), Toxicon, 48, 160-174.

- MEZ, K., K.A. BEATTIE, G.A. CODD, K. HANSELMANN, B. HAUSER, H. NAEGELI and H.R. PREISIG (1997).Identification of a microcystin in benthic cyanobacteria linked to cattle deaths on alpine pastures in Switzerland. Eur. J. Phycol., 32, 111-117.

- MUR, L.R., O.M. SKULBERG and H. UTLIKEN (1999). Cyanobacteria in the environment. In : Toxic Cyanobacteria in water: A guide to their Public Health Consequences, Monitoring and Management.Chorus, I. and J. Bartram (Editors), E & Spon, London, pp. 15-40.

- NASRI, A.B., N. BOUAICHA and J. FASTNER (2004). First report of a microcystin containing bloom of the cyanobacteria Microcystis spp. in Lake Oubeira, eastern Algeria. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 46, 197-202.

- OLIVER, R.L. and G.G. GANF (2000). Freshwater blooms. In : The Ecology of Cyanobacteria: Their Diversity in Time and Space. Whitton, B.A. and M. Potts (Editors), Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 149-194.

- OUDRA, B., M. LOUDIKI, B. SBIYAA, R. MARTINS, V. VASCONCELOS and N. NAMIKOSHI (2001a).Isolation, characterization and quantification of microcystins (heptapeptides hepatotoxins) in Microcystis aeruginosa dominated bloom of Lalla Takerkoust lake reservoir (Morocco).Toxicon, 39, 1375-1381.

- OUDRA, B., M. LOUDIKI, B. SABOUR, B. SBIYYAA and V. Vasconcelos (2001b). Étude des blooms toxiques à cyanobactéries dans trois lacs réservoirs du Maroc : Résultats préliminaires. Rev. Sci. Eau, 15, 301-313.

- OUDRA, B., M. LOUDIKI, B. SBIYYAA, B. SABOUR, R. MARTINS, A. AMORIM and V. VASCONCELOS (2002a). Detection and variation of microcystin contents of Microcystis blooms in eutrophic Lalla Takerkoust Lake, Morocco. Lake Reser. Manag., 7, 35-44.

- OUDRA, B., M. LOUDIKI, V. VASCONCELOS, B. SABOUR, B. SBIYYAA, K.H. OUFDOU and N. MEZRIOUI (2002b). Detection and quantification of microcystins from cyanobacteria strains isolated from reservoirs and ponds in Morocco. Environ. Toxicol., 17, 32-39.

- OUDRA, B., M. DADI-EL ANDALOUSSI and V. VASCONCELOS (2008). Identification and quantification of microcystins from a Nostoc muscorum bloom occurring in Oukaïmeden River (High-Atlas mountains of Marrakech, Morocco). Environ. Monit. Assess., DOI 10.1007/s10661-008-0220-y.

- PADILLA, C., S.-A. SOLEDAD and F.F. DEL CAMPO (2006). Toxin characterization and identification of a Microcystis flos-aquae strain from a Spanish drinking-water reservoir. Arch. Hydrobiol., 165, 383-399.

- PRATI, M., M. MOLTENI, F. POMATI, C. ROSSETTI and G. BERNARDINI (2002). Biological effect of Planktothrix sp FP 1 cyanobacterial extract. Toxicon, 40, 267-272.

- ROHRLACK, T., M. HENNING and J.G. KOHL (2001). Cyanotoxins: occurrence, causes, consequences. In: Isolation and Characterization of Colony-forming Microcystis aeruginosa Strains. CHORUS, I. (Editor), Springer, Berlin, Germany, pp. 152-158.

- SABOUR, B., M. LOUDIKI, B. OUDRA, V. VASCONCELOS, S. OUBRAIM and B. FAWZI (2005). Dynamics and toxicity of Anabaena aphanizomenoides (Cyanobacteria) waterblooms in the shallow brackish Oued Mellah lake (Morocco). Aquat. Ecosys. Health Manage., 8, 95-104.

- SABOUR, B., M. LOUDIKI, B. OUDRA, V. VASCONCELOS, R. MARTINS, S. OUBRAIM and B. FAWZI (2002). Toxicology of a Microcystis ichthyoblabe waterbloom from Lake Oued Mellah (Morocco). Environ. Toxicol., 17, 24-31.

- SBIYYAA, B., B. OUDRA, M. LOUDIKI, A. BOUGUERNE and A. TIFNOUTI (1998). Acute toxicity of Microcystis aeruginosa KÜTZ to three cladoceran species. In: Harmful Algae. REGUERA, B., J. BLONCO, M.L. FERNANDEZ et T. WYATT, (Editors), Xunta de Galicia and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO, pp. 29-31.

- SCHEFFER, M., S. RINALDI, A. GRAGNANI, L.R. MUR and E.H. VAN NES (1997). On the dominance of filamentous cyanobacteria in shallow, turbid lakes, Ecology, 78, 272-282.

- SHIRAI, M., A. OHTAKE, T. SANO, S. MATSUMOTO, T. SAKAMOTO, A. SATO, T. AIDA, K. HARADA, T. SHIMADA, M. SUZUKI and M. NAKANO (1991). Toxicity and toxins of natural blooms and isolated strains of Microcystis spp.(Cyanobacteria) and improved procedure for purification of cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 57, 1241-1245.

- SIVONEN, K. and G. JONES (1999). Cyanobacterial toxins.In: Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water: A Guide to Their Public Health Consequences, Monitoring and Management. CHORUS, I. et J. BARTRAM (Editors), E & Spon, London, pp. 41-111.

- STARMACH, K. (1966). Cyanophyta- Since Glaucophyta- glaukofity- Flora Slodkow. - Polski. PWN. Warszawa, 2, pp. 807.

- THAJUDDIN, N. and G. SUBRAMANIAN (2005). Cyanobacterial biodiversity and potential applications in biotechnology. Curr. Sci., 89, 47-57.

- VASCONCELOS, V.M. (2001) Toxic freshwater cyanobacteria and their toxins in Portugal. In: Cyanotoxins: Occurrence, Causes, Consequences. CHORUS, I. (Editors), Springer, Berlin, Germany, pp. 64-69.

- VEZIE, C., L. BRIENT, K. SIVONEN, G. BETRU, J.C. LEFEUVRE and M. SALKINOJA-SALONEN (1997). Occurrence of microcystins containing cyanobacterial blooms in freshwaters of Brittany (France). Arch. Hydrobiol., 139, 401-413.

- VEZIE, C., L. BRIENT, K. SIVONEN, G. BETRU, J.C. LEFEUVRE and M. SALKINOJA-SALONEN (1998). Variation of microcystin content of cyanobacterial blooms and isolated strains in Lake Grand-Lieu (France). Microb. Ecol., 35, 126-135.

- WIEGAND, C. and S. PFLUGMACHER (2005). Ecotoxicolo-gical effects of selected cyanobacterial secondary metabolites: a short review, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 203, 201-218.

- ZAKARIA, A.M., M.E. HASSAN and S.M.A. WAFAA (2006).Microcystin production in benthic mats of cyanobacteria in the Nile River and irrigation canals, Egypt, Toxicon, 47, 584-590.

List of figures

Figure 1

Specific richness evolution of cyanobacteria in Moroccan inland waters.

Évolution de la richesse spécifique des cyanobactéries dans les eaux intérieures du Maroc.

Figure 2

Spectrum of the orders of cyanobacteria inventoried in Moroccan inland waters.

Répartition des ordres de cyanobactéries dans les eaux intérieures marocaines.

Figure 3

Geographic localisation of some Moroccan reservoirs, natural lakes and ponds where Microcystis strains have been inventoried.

Localisation géographique des réservoirs, des lacs naturels et des étangs où des souches de Microcystis ont été inventoriées.

Reservoirs:

1- Ibn Battouta, 2- Smir, 3- M.B.A. Khettabi, 4- O. El Makhazine, 5- Sahela, 6- Mohammed V, 7- Idriss I, 8- Allal El Fassi, 9- Elkansera, 18- S. M. Ben Abdellah, 19- Oued Mellah, 20- Al Massira, 21- Imfout, 22- Daourat, 23- Lalla Takerkoust, 24- M. Eddahbi, 25- Abdelmoumen, 26- Y.B. Tachfine.

Natural lakes and ponds:

10- Sidi Boughaba, 11- Dayèt Erroumi, 12- Dayèt Aoua, 13-Dayèt Affourgah, 14- Dayèt Iffrah, Dayèt Aoua, Dayèt Iffrah, 15- Aguelmane Azigza, 16- Aguelmane Sidi Ali, 17- Tiguelmamines.

Figure 4

Distribution of inventoried cyanobacteria by type of aquatic biotope.

Distribution des cyanobactéries inventoriées selon les différents types de biotopes aquatiques.

List of tables

Table 1

New taxa inventoried for the first time in Moroccan inland waters.

Nouveaux taxons inventoriés pour la première fois dans les eaux continentales du Maroc.

|

Achroonema macromeres Sku. Anabaena oscillarioides Bory. Aphanocapsa conferta (W. et G.S. We.) Leg.et Cro. Aphanocapsa hyalina (Lyn.) Han. Aphanothece smithii Len. et Cron. Arthrospira maxima Set. et Gar. Chroococcopsis gigantea Geit. Chroococcus obliteratus Rich. Coelosphaerium kutzingianum Näg. Cyanobacterium minervae (Cop.) Kom. Cyanonephron styloides Hick. Cyanothece aeruginosa (Näg.) Kom. Geitlerinema acus (Cop.) An. Geitlerinema bigranulatum Tiw. Geitlerinema lemmermannii (Wol.) An. Gloecapsopsis dvorakii (Nov.) Kom. et An. Gloecapsopsis pleurocapsoides (Nov.) Kom. et An. Gloeocapsopsis magma (Bréb.) Kom. et An. Homoeothrix juliana (Born. et Flau.) Kir. Homoeothrix margalefii Kom. et Kal. Hormoscilla spongeliae Gom. Hormoscilla xishaensis Hu. Jaaginema homogeneum (Frém.) An. et Kom. Jaaginema unigranulatum (Bis.) An. Leptolyngbya faveolarum (Rab.) An. et Kom. Leptolyngbya benthonica (Sku.) An. Leptolyngbya boryana An. et Kom. |

Leptolyngbya ercegovici (Cado) An. et Kom. Leptolyngbya fragilis (Gom.) An. et Kom. Leptolyngbya lurida (Gom.) An. et Kom. Limnothrix guttulata (Van Goor) Ume. et M. Wat. Limnothrix obliqueacuminata (Skuj.) Mef. Limnothrix pseudovacuolata (Uter.) An. Limnothrix rosea (Uter.) Meff. Lyngbya biebliana Clau. Lyngbya confervoides C. Ag. Lyngbya nigra Ag. Lyngbya semiplena J. Ag. Lyngbya stagnina Kütz. Nostoc Punctiforme (Kütz.) Har. Oscillatoria acuminata Geit. et Rut. Oscillatoria nigra Ag. et Kut. Oscillatoria ornata Kütz. Pascherinema moniliforme (Pas.) De Ton. Phormidiochaete balearica (Born.e Flau.)Kom. Phormidiochaete nordstedtii Kom. et Kan. Phormidium alaskense Gom. Phormidium bekesiense (I. Kiss) K. Kiss Phormidium bohneri Schm. Phormidium bulgaricum (Kom.) Kom. et An. Phormidium chalybeum ( Mer.) An. et Kom. Phormidium chungii Gar. Phormidium fonticolum Kütz. Phormidium kolkwitzii Kom. |

Phormidium lacustre (Cad.) An. Phormidium lusitanicum Samp. Phormidium paulsenianum (Boy.) Nov. Phormidium rosea (Skuj.) An. Phormidium simplicissimum (Gom.)An.et Kom. Phormidium stagninum (Kütz. ex Gom.) An. Phormidium tergestinum An. Phormidium versicolor Wart. Pseudanabaena biceps Bour. Pseudanabaena lonchoides An. Pseudanabaena moniliformis Kom. Pseudanabaena papillaterminata Kuk. Pseudanabaena starmachii An. Pseudocapsa sphaerica (Pro.) Kov. Romeria chlorina Böch. Schizothrix calcic la Gom. Spirulina nordstedtii Gom. Symploca cavernarum Cop. Synechococcus sciophilus sku. Synechocystis crassa Vorn. Synechocystis endobiotica Elen. et Holl. Synechocystis minuscule Vorn. Synechocystis pevalkii Erc. Woronichinia naegeliana (Ung.) Elen. |

Table 2

Distribution of toxic and potentially toxic cyanobacterial strains in some Moroccan inland waters that were surveyed.

Distribution des souches toxiques et potentiellement toxiques dans certains milieux hydriques continentaux marocains prospectés.

SPECIES |

RESERVOIRS |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

AB |

AM |

EK |

IB |

IM |

KT |

LT |

ME |

NAK |

OE |

SM |

SMBA |

YBT |

|

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

|

* |

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

* |

Coelosphaerium naegelianum Ung. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

Gomphosphaeria aponina Kütz. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

Lyngbya birgei G. M. Smit. |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

Microcystis aeruginosa (Kütz.) Kütz. |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

* |

|

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

Microcystis flos-aquae (wit.) Kirch. |

* |

|

|

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

|

|

* |

|

Phormidium formosum (Bor.) An. et Kom. |

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Planktothrix agardhii (Gom.) An. et Kom. |

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

Planktothrix isothrix (Skuj.) Kom. et Koma. |

* |

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

Pseudanabaena catenata Laut. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

Pseudanabaena galeata Böch. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pseudanabaena mucicola Nau. et Hub. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schizothrix calcicola Gom. |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Woronichinia naegeliana (Ung.) Elen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NATURAL LAKES |

||||||||||||

AA |

AF |

AW |

DA |

DE |

IF |

IFR |

SBG |

SZ |

TI |

||||

Anabaena spiroides Kleb. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|||

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|||

Microcystis aeruginosa (Kütz.) Kütz. |

* |

* |

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

|||

Microcystis flos-aquae (wit.) Kirch |

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Microcystis wesenbergii (Kom.) Kom. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|||

Phormidium formosum (Bor.) An. et Kom. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

|||

Pseudanabaena galeata Böch. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|||

|

RIVERS AND ESTUARIES |

||||||||||||

AMI |

BR |

MAS |

OK |

OTE |

OUR |

||||||||

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

|

* |

* |

|

|

|

|||||||

Nostoc muscorum Ag. |

* |

|

|

* |

|

* |

|||||||

Phormidium formosum (Bor.) An. et Kom. |

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|||||||

Pseudanabaena biceps Bour. |

|

|

|

|

|

* |

Reservoirs : |

AB : Abdelmoumen ; AM : Al Massira ; EK : El Kansera ; IB : Ibn Batouta ; IM : Imfout ; KT : Kasba Tadla ; LT : Lalla Takerkoust ; ME : Mansour Eddahbi ; NAK : Nakhla ; OE : Oued El Makhazine ; SM : Smir ; SMBA : Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah ;YBT : Youssef Ben Tachfine. |

Natural lakes : |

AA : Aguelmam Azigza ; AF : Aguelmam Afourgah ; AW : Aguelmam Wiwane ; DA: Dayet Awa ; DE : Dayet Erroumi ; IF : Dayet Iffer ; IFR : Dayet Ifrah ; SBG: Merja de Sidi Boughaba ; SZ : Sebkha Zima ; TI : Tiguelmamines. |

Rivers and estuaries : |

AMI : Oued Aït Mizane ; BR : Bou Regreg estuary ; MAS : Estuaire Massa ; OK : Oued Oukaimden ; OTE: Oued Tensift OUR: Oued Ourika |

Table 3

Toxicological data of tested cyanobacteria (isolates, mats, blooms) in various Moroccan inland waters.

Données toxicologiques des cyanobactéries testées (isolats, blooms, films benthiques) dans divers milieux hydriques continentaux marocains.

|

Sampling Date |

Locality |

|

Toxicity |

HPLC Species |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Mouse bioassay LD50 (mg DW•kg‑1) |

Artemia assay LC 50•24 h‑1 (μg•mL‑1) |

Content (μg•g‑1 eq MC‑LR) |

Microcystins profile ratio |

Blooms |

07‑2003 |

L.Takerkoust |

Mic. A. TAK |

176,8 |

1 414 |

13,94 |

RR (14), LR (16,6), FR (23,1) WR (46,4) |

10‑2004 |

M. Eddahbi |

Mic. A. MED |

352 |

1 712 |

64,4 |

RR (41,3),YR (21,7), LR (33,7), FR (1,1), WR (2,3) |

|

07‑2004 |

Al Massira |

Mic. A. ALM |

829 |

4 343 |

9,9 |

LR (100) |

|

10‑2004 |

Dayèt Erroumi |

Mic. A. ER |

- |

- |

1,87 |

RR (15,3) XZ* (8,2) LR (3,6) FR (20,3) WR (52,6) |

|

Mats |

10‑2004 |

Tiguelmamines |

Mic. W. Ti |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D. |

N.D |

06‑2003 |

Oued Ourika |

Nos. M. OUR |

119,5 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

06‑2003 |

Oued Ourika |

Lyn. A1 |

742 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

06‑2003 |

Oued‑Oukaimeden |

Lyn. A2 |

1 450 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

Isolates |

07‑2003 |

L.Takerkoust |

Mic. A. S13 |

- |

- |

9,44 |

RR (62), YR (2,6), LR (6,7) FR (7,9), WR (20,8) |

08‑2005 |

M. Eddahbi |

Plank. A. S22 |

- |

- |

3,19 |

RR (100) |

|

12‑2004 |

Oued Ourika |

Pseud. B. S23 |

- |

- |

0,28 |

XZ* (100) |

|

07‑2003 |

L.Takerkoust |

Pseud. C. S24 |

1 192,7 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

|

06‑2003 |

Lac Zima |

Pseud. G. S25 |

292,8 |

- |

N.D. |

N.D |

* : Unknown MC variant, N.D. : Not detected

Plank. A. S22: Planktothrix agardhii; Pseud. B. S23: Pseudanabaena biceps ; Pseud. C. S.24: Pseudanabaena catenata; Pseud. G. S.25: Pseudanabaena galeata ; Mic. A. Tak, ALM, ER : Microcystis aeruginosa; Lyn. A1,2 : Lyngbya attenuata ; Nos. M. OUR : Nostoc Muscorum. Mic. W. Ti : Microcystis wesembergii. TAK: L. Takerkoust; ALM : Al Massira; MED : Mensou Eddahbi: OUR: Oued Ourika; OK: Oued Oukaimeden; LZ : Lac Zima; TI: Tiguelmamine.

Table 4

Isolated cyanobacteria strains screened for microcystin detection, sampling sites, type of biotope and sample characteristics.

«Screening» des souches isolées : détection de microcystins, sites échantillonnés, type de biotope, caractéristiques d’échantillons.

Strains code |

Species |

Sampling site / type of biotope / date |

Characteristic of the strain in original sample |

|---|---|---|---|

S1 |

Anabaena variabilis Kütz. |

Bou Regreg / Estuary / 07‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S2 |

Anabanopsis circularis Gayr. |

Sidi Bou Rhaba / Estuary / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S3 |

Cyanobacterium minervae (Cop.) Kom |

Palmeraie / Bassin, Marrakech / 06‑2003 |

In the water mass |

S4 |

Geitlerinema lemmermannii.Tav. |

Benslimane / Daya ( temporary lac) / 10‑2004 |

Attached to ground submerged or not by water |

S5 |

Jaaginema sp. |

Azigza / Lac / 11‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks or with other filamentous species |

S6 |

Leptolyngbya faveolarum (Rab.) An. et Kom. |

Sidi Bou Rhaba / Lac / 07‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks reservoir or with other filamentous species |

S7 |

Leptolyngbya boryana An. |

Safi / Reservoir / 08‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks reservoir |

S8 |

Leptolyngbya lurida (Sku.) An. |

Ourika / Stream / 11‑2006 |

Attached to substrate of the edge of the stream |

S9 |

Leptolyngbya sp. |

Sebkha Zima / Lac / 07‑2005 |

Attached to other filamentous species |

S10 |

Limnothrix rosea (Ute.) Mef. |

Oued Tassaout / River / 06‑2004 |

Attached to gravels in the calm zones of river |

S11 |

Lyngbya hieronymusii Lemm. |

Imfout / Reservoir / 07‑2004 |

Attached to the substrate of the banks or with other filamentous species |

S12 |

Microcystis wesembergii. (Kom.) Kom. |

Tigelmamines / Lac /10‑2005 |

Float on the surface of the water mass forming scum or bloom |

S13 |

Microcystis aeruginosa(Kütz.) Kütz. |

L. Takerkoust / Reservoir/ 07‑2003 |

Float on the surface of the water mass forming scum or bloom |

S14 |

Oscillatoria limosa Ag. |

My. Youssef / Reservoir / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass and other filamentous species |

S15 |

Phormidium articulatum Clau. |

Bouznika / River / 10‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S16 |

Phormidium chalybeum (Mer.ex Gom.) An. et Kom. |

Bouznika / River / 10‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S17 |

Phormidium Koprophilum (Sku.) An. |

Oued Mellah / River / 07‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S18 |

Phormidium lusitanicum Sam. |

Oued Cherat / Benslimane / 07‑2004 |

Attached to muddy substrate or with other filamentous species |

S19 |

Phormidium paulsenianum (Boy.) Nov. |

Oued Mellah / River / 07‑2004 |

Attached to substrate of the edge of the river with other filamentous species |

S20 |

Phormidium sp. |

ElKansera / Reservoir / 10‑2005 |

Attached to other filamentous species forming floating mats |

S21 |

Phormidium subfuscum Kütz. |

Sidi Daouad / Canal, Marrakech / 10‑2004 |

Attached with other filamentous on the edge of canal |

S22 |

Planktothrix agardhii(Gom.) An. et Kom. |

M. Eddahbi / Reservoir/ 10‑2004 |

Float on the surface of the water mass forming scum or bloom |

S23 |

Pseudanabaena biceps Bour. |

Ourika / Stream / 11‑2005 |

Attached to substrate of the edge of the stream |

S24 |

Pseudanabaena catenata Laut. |

L. Takerkoust / Reservoir / 07‑2003 |

In the water mass and other filamentous benthic species |

S25 |

Pseudanabaena galeata Böch. |

Lac Zima / Lac / 07‑2003 |

Attached to other filamentous species forming floating mats |

S26 |

Pseudanabaena lonchoides An. |

M. Eddahbi / Reservoir / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S27 |

Pseudanabaena papillaterminata Kuk. |

M. Eddahbi / Reservoir / 10‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S28 |

Synechocystis minuscula Vorn. |

Azigza / Lac / 10‑2005 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |

S29 |

Synechocystis salina Wis. |

Bou Regreg / estuary / 07‑2004 |

In the water mass, non forming bloom |