Article body

In her 2014 book Graphesis, Johanna Drucker imagines the “book of the future” having “data trails as guidebooks for the experience of reading, pointing to milestones and portals for in-depth exploration of stories, inventories, and the rich combination of cultural heritage and social life in a global world” (63). Based on this prognostication, Matthew Sangster, might be said to have created such a “book of the future” in Romantic London , his site that plots Romantic-era books onto interchangeable base maps of the English metropolis. In some respects, Sangster’s project shares research and methodological characteristics with several recent spatial visualization projects, including Map of Early Modern London , Locating London’s Past, and Layers of London . The unique value of Romantic London, however, comes in how, by mapping key books on the city, it “curates” London into distinct metropolitan exhibits, making this still-expanding resource particularly relevant to an issue on “Romantic Museums.” In this review essay, I will introduce the site’s interface, describe its book-historical and digital features, and offer a case study of how it might inform and enable new work in our field.

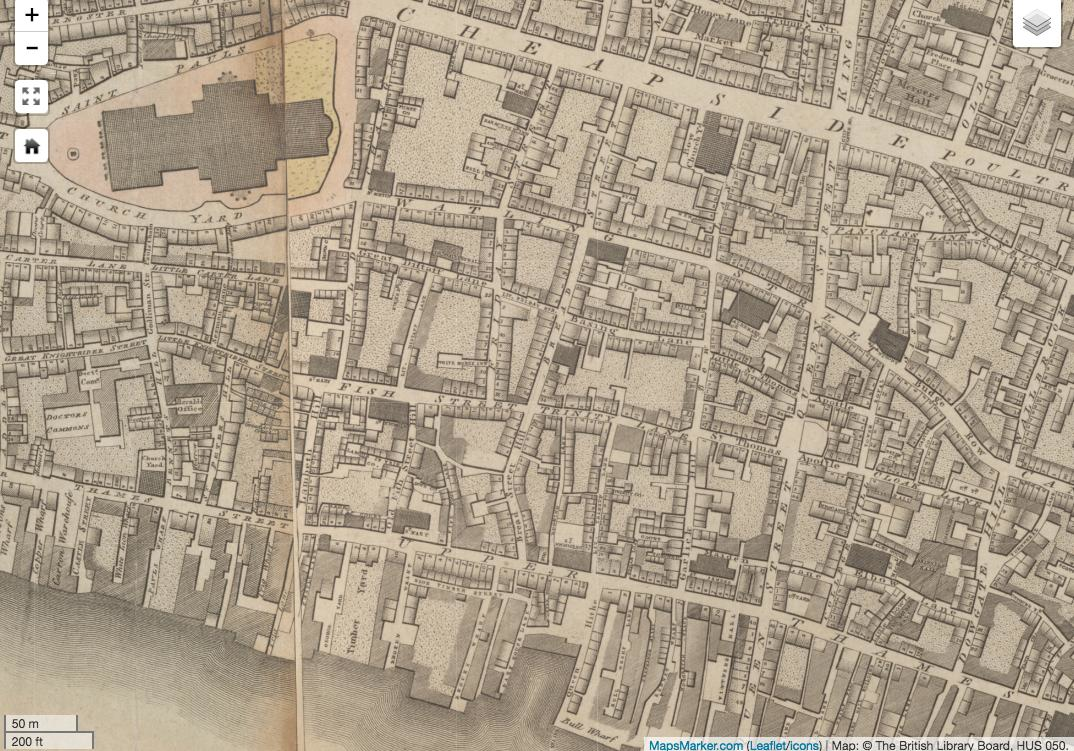

Romantic London is intuitive to navigate once one understands its structure and goals. The heart of the project is an interactive digital edition of Richard Horwood’s Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, the Borough of Southwark, and Parts Adjoining, Shewing Every House , a map published in 1792 and regularly updated through 1799 (Fig. 1). Sangster’s main menu steers users first to a page introducing Horwood, his map, and the multi-layered project that rests upon it. Additional menu links point to individual pages for the nine books Sangster has thus far mapped onto Horwood’s Plan and a blog describing recent updates. All nine books are guides of sorts to London, ranging from picturesque tours, to a directory for prostitutes, to Book 7 of Wordsworth’s 1850 Prelude. For each title, Sangster provides an introductory essay as well as a subpage mapping the book onto an interactive digital edition of the Plan. For each pin marking a location from one of these books, he includes a note situating the site within its source text. For some books, he offers additional image galleries or slideshows, and all nine books can be simultaneously mapped using the “All Curations” feature.

Conceived and launched in 2014, Romantic London began to experience significant traffic in 2015. In the year that followed, approximately 20,000 unique visitors spent a total of 4,000 hours on the site. In 2017, those numbers jumped to 53,500 visitors spending 7,500 hours. Sangster’s maps and images are now being used not only by scholars at such universities as Simon Fraser, York, and Queen Mary, but also by non-academics, many of whom reportedly visit simply to plot their current home on Horwood’s eighteenth-century map.

Figure 1

Close-up from Romantic London showing the intricate detail—note the street names and numbers—of Horwood’s Plan

In his introduction to Horwood’s map, Sangster details the bibliographic methods informing his project and describes how the Plan ranks among the most remarkable achievements of eighteenth-century cartography and publishing. Horwood’s surpassed other London maps in showing individual properties by house number, an endeavor so daunting that more than a century had passed since a mapmaker had attempted this feat. Initially self-published on 32 separate printed sheets, the Plan attracted 883 subscribers, who either paid the full price up front or upon delivery of individual sheets. When pieced together like a puzzle, the sheets created a master map measuring over thirteen feet by seven feet. Gratefully, Romantic London allows modern users to view the entire map at once on a screen, neatly aligning the 32 sheets and allowing users to zoom in and out as needed.

More than just a static online reproduction of Horwood’s influential map, however, Romantic London places the Plan in dialogue with an array of guidebooks to important aesthetic, social, and geographical landmarks. In “Accumulating London,” a separate essay published as part of the British Library’s “Picturing Places” collection, Sangster analyzes some of these landmarks and concludes that Romantic-era print culture created London’s “topographical heritage” as “an ordered accumulation that is structured in discursive, idealistic, pragmatic, quotidian and surprising ways.” By mapping books from the period onto Horwood’s Plan, Romantic London visualizes this “ordered accumulation” of landmarks and a systematized vision of late Georgian London’s most notable places.

A brief survey of the nine books currently on Romantic London reveals the variety among Sangster’s selections to date:

-

Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies (1788) is an annual catalog of London prostitutes. Published annually between 1757 and 1795, it provides descriptions in verse of the women’s names, locations, prices, and physical attributes.

-

Samuel Fores’s New Guide for Foreigners (1789?) is a handbook to London and Westminster offering “an Account of all the Palaces, Seats, Villas, Parks, Gardens, Collections of Pictures, Towns, and Villages, within a Distance of Twenty-Five Miles around the Metropolis.”

-

John Smith’s Antiquities of London (1791-1800) features 96 plates depicting an array of historic buildings. Besides theaters, castles, surgeries, inns, fountains, and prisons, it includes miscellaneous oddities like “A Curious Pump, in the yard belonging to the Company of Leather Sellers, opposite their Hall.”

-

Thomas Malton’s A Picturesque Tour Through the Cities of London and Westminster (1792-1801) captures London’s ornate architectural facades in lavish aquatint plates designed to monumentalize and celebrate the nation’s wealth.

-

Richard Phillips’s Modern London; being the History and Present State of the British Metropolis (1804) claims to represent “London as it is” in the early 1800s via two sets of plates. The first 22 plates show London landmarks, and the second 31 plates depict various classes of the city’s itinerant tradespeople.

-

The Microcosm of London, published by Rudolph Ackermann between 1808 and 1810, is a three-volume series with 104 striking architectural prints. Charles Pugin’s engravings of buildings are overlaid with human figures by Thomas Rowlandson.

-

Select Views of London (1816), compiled and arranged by John B. Papworth and published by Ackermann, features 76 plates of major architectural landmarks like St. James Palace and Whitehall Chapel. Because this book was published two decades after Horwood’s original map of 1792, Sangster pins its sites to the updated fourth edition of the Plan (1819) that William Faden published after Horwood’s death.

-

Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1821) follows the rambles of three stock male characters: a London social elite, a country cousin, and an indelicate instigator. The volume chronicles in prose and image everything from the regal Throne Room at Carleton Place to street brawling in Leicester Fields to “masquerading” in the “Black Slums.”

-

Book VII of the 1850 Prelude—the most recent addition to Romantic London, being added in July 2017—includes Wordsworth’s recollections of various London sites he visited during the 1780s and 1790s.

Among the titles Sangster hopes to add later are children’s books, walking guides, essays by Charles Lamb, and, most excitingly, Frances Burney’s Evelina, which might prove a provocative complement to Wordsworth’s Prelude.

On his page “Creating the Online Plan,” Sangster details the technical infrastructure behind Romantic London. After obtaining British Library scans of the 32 sheets of Horwood’s map in .tiff format, he first aligned these pages using GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) before exporting a master .png image of the composite map. Then he used MapTiler Plus to convert this .png file into a tiled map capable of being layered onto Google Maps and OpenStreetMap. From here, he used surviving monuments and intersections to align eighteenth- and twenty-first-century maps. Finally, he used a Maps Marker Pro plugin to place annotated pins on the layered maps. The end result is that, when the mouse hovers over a particular pin, Sangster’s annotation for that site appears. Clicking the mouse on a pin opens a pop-up window with an image or text from the original Romantic-era book (see Fig. 2). Other helpful tools include buttons in the top-right corner of each map that allow users to download the marker data as KML (for Google Earth/Maps), GeoJSON, or GeoRSS files. Users can also create QR codes for particular map views, a feature that might, for instance, allow library exhibits of the 1850 Prelude to include a QR code enabling visitors to pinpoint sites featured in the book on their mobile phones.

Romantic London currently offers five possible base map layers on which to view pinned locations from the nine books. Two of the base layers feature Romantic-era maps (Horwood’s Plan [1792-99] and Faden’s 1819 revision of the Plan), and the remaining three are up-to-date maps in OpenStreetMap, Google Maps roadmap view, and Google Maps satellite view. Pins marking sites from each book constitute the second type of layering. Currently there are nine possible layers of pins (one per book) on each base map. As seen in Figure 2 below, the “All Curations” screen allows researchers to view one, several, or all of these layers—with up to 636 pins total—by selecting or deselecting individual books via the “layer” icon in the top right corner. Book layers can be altered by clicking on the “pin” icon just below the “layer” icon.

Figure 2

Sample “All Curations” view from Romantic London, with pinned sites from all nine books and a pop-up illustration for one particular location

Regarding the utility of projects like Romantic London, Richard White recently argued that “spatial history” is

not about producing illustrations or maps to communicate things that you have discovered by other means. It is a means of doing research; it generates questions that might otherwise go unasked, it reveals historical relations that might otherwise go unnoticed, and it undermines, or substantiates, stories upon which we build our own versions of the past. (emphasis in original)

(par. 36)

From this perspective, a site like Romantic London is best approached as a research tool in the service of further analysis, not a static set of completed analyses. Accordingly, the potential value of Sangster’s site is most apparent when its data and interface are applied to a specific research question.

Since I am currently working with the Francis Stainforth Library of Women’s Writing, my first impulse upon discovering Romantic London was to see if it might illuminate London-based women’s lives in general and their activities within the book trade in particular. Sangster’s plotting of sites from Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies (1788) seemed particularly promising for such research; and, in fact, a basic search of his Mapping Harris’s List page revealed that most late-eighteenth-century London prostitutes worked in today’s northeast Mayfair and south Bloomsbury, with the highest concentration in the triangle between the modern Underground stations at Goodge Street, Oxford Circus, and Tottenham Court.

The concentration of red pins in the northwest corner led me to wonder how this same neighborhood was depicted in Modern London (1804), since I recalled seeing women depicted as itinerant merchants in Sangster’s map of that book. The “All Curations” page made such a comparison easy, as I only needed to select the views for Harris’s List and Modern London (see Fig. 3). The resulting map reveals how the majority of itinerant traders featured in Modern London worked in the city’s northwest quadrant.

Figure 3

Customized “All Curations” view, with red pins for prostitutes included in Harris’s List and orange pins for itinerant traders in Modern London

Zooming in further, we discover a woman trader (the orange pin near the center) operating at the epicenter of a large cluster of prostitutes’ addresses (the red pins) provided by Harris’s List. Clicking on this particular orange pin generates the pop-up window seen in Figure 4 below. This plate from Modern London shows a working girl who sells “new potatoes” from a cart outside Middlesex Hospital. She is attired in a black bonnet, a bright checkered headscarf, a blue dress, and a red overcoat, with the sleeves rolled up above her elbows. Her forearm muscles are flexed and she leans forward, knees bent, preparing to move her cart. If we turn to Sangster’s “Itinerant Trades Map” for Modern London , we learn that late June and July are the months when potatoes were plentiful enough to be sold cheaply in the streets for three halfpence or a penny per pound, on average.

Figure 4

This potato seller is one of ten female itinerant merchants depicted in Modern London. All nameless, they are represented entirely by their bodies, their work, and their addresses—or exactly as the “Covent-Garden Ladies” are catalogued in Harris’s List. By pinpointing the trader among so many prostitutes and including a plate accentuating her body and posture, Romantic London invites a reading of "New Potatoes" in which the seller satisfies appetites beyond those satiated by the tiny root vegetables barely visible in her cart. Another intriguing insight comes from noting that the pin for the potato merchant is adjacent to a Harris’s List pin for the escort Miss Cl–nt–on, who is said to operate “near Middlesex Hospital […] at No. 17, read____ Street.” Harris’s verse description of her attributes has Miss Cl–nt–on inviting prospective clients to “Mark my eyes, and as they languish, / Read what your’s [sic] have written there.” It goes on to paint her as “a very genteel made little girl, with the languishing eye of an Eloise; like her too, she is warm with the fire of love” (42). This “languishing eye” of Miss Cl–nt–on is a blank page or a canvas for her male client to “mark” or write upon.

The maps generated by Romantic London also loosely connect this “Covent-Garden lady” to women languishing just yards away at the Middlesex Hospital. The “All Curations” view reveals a third pin for this location, this one marking the hospital and including a sketch of its interior from Ackermann’s The Microcosm of London (see Fig. 5). Pugin and Rowlandson’s image shows a ward with nine patients attended by nurses and visitors and a small group in the foreground huddled around someone who appears to be a doctor. Looking more carefully, we realize this scene is dominated by women, as, besides the predominantly female nurses and visitors, all nine patients are women.

Figure 5

A sequence of searches on Romantic London, then, can open up a range of new and potentially important insights into gender and geography at the turn of the nineteenth century. We discover that the streets around Middlesex Hospital were apparently a nexus for women’s labor and suffering: prostitutes selling their bodies, street merchants peddling potatoes and perhaps more, and nurses attending to female patients. Turning from here to Google Books, I learned from Erasmus Wilson’s 1845 History of the Middlesex Hospital During the First Century of Its Existence that the hospital opened in 1745, offered medical care and assistance specifically to the poor, and controversially assisted only married women with their pregnancies, since donors refused to fund out-of-wedlock births. In this respect, the pregnant women at Middlesex Hospital, whose bodies are carefully spaced in Pugin and Rowlandson’s sketch in beds that encircle the room, might be read as “pins” demarcating an interior “plan” of the hospital in terms of female sexuality.

Romantic London, in this instance, allows us to see a whole quadrant of the metropolis being given over to women who were poor, laboring, or in labor. Beyond this, Sangster’s lucid and informative critical commentary reveals that publishers produced and sold these depictions of women to clients who were overwhelmingly male (e.g., Harris’s List) or could afford expensive sets of fine-art prints (as with Microcosm and Modern London ). While we still need sources like Stainforth’s catalog to understand women’s roles in producing and consuming texts, Sangster’s “spatial history” offers compelling evidence for how sometimes women were the texts.

Like many of the best digital projects, Romantic London is a work in progress. Ideally, future expansions of the corpus will include works authored or edited by women. Particularly prime titles are Elizabeth Helme’s Instructive Rambles in London, and the Adjacent Villages (1798) and Catharine Kearsley’s Stranger’s Guide, or Companion through London and Westminster, and the Country Round (1791), both of which are currently available in the Women’s Travel Writing, 1780-1840) database. Adding such books would facilitate important queries into whether women’s mappings of London counter or accord with men’s. Already, though, Sangster’s “book of the future,” like other spatial visualization projects, might help us literally remap Romantic-era literary history.

Appendices

Biographical note

Kirstyn Leuner is Assistant Professor of English at Santa Clara University. She specializes in British literature of the long eighteenth-century, Digital Humanities, and women's writing. She is Director of the Stainforth Library of Women’s Writing and working on a related monograph.

Works Cited

- Drucker, Johanna. Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Harvard UP, 2014.

- White, Richard. “What is Spatial History?” The Spatial History Project, 1 Feb. 2010. https://web.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/pub.php?id=29.

- Wilson, Erasmus. The History of the Middlesex Hospital During the First Century of its Existence. John Churchill, 1845.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5