Abstracts

Abstract

In 2018, Canada became the first G7 nation to legalize recreational cannabis. In response, at least a dozen prominent employers in safety-sensitive industries implemented policies to prevent workers from using legal cannabis for extended periods before reporting for duty, ranging from 28 days to a continual ban. The various unions that represent these workers allege an unnecessary breach of employee privacy and intend to challenge the legality of the policies. Informed by labour arbitration and Supreme Court decisions, this paper proposes a custom-made test and uses it to assess the enforceability of the new cannabis workplace policies. Notwithstanding the significant challenges facing employers, it is the position of this paper that the new policies are enforceable under certain conditions.

Summary

Informed by labour arbitration and Supreme Court decisions, this paper proposes a custom-made test and uses it to assess the enforceability of the new cannabis workplace policies, which prohibit legal consumption for safety-sensitive workers.

The analysis identifies two main challenges facing employers.

Establishing that a problem exists in the workplace. Consumption of cannabis must have an impairing effect during the period of prohibition.

Demonstrating that the policy has sufficient benefits to justify the consequences. The improvements in workplace safety must outweigh the breech of employee privacy.

To identify a problem in the workplace, employers will rely on the strongest available evidence linking cannabis to impairment during the entire period of prohibited consumption. Medical research is helpful in this regard. A substantial body of evidence points to significant motor and cognitive deficiencies immediately following consumption (first eight hours). Although some studies indicate a prolonged period of impairment, the evidence is less compelling as a user approaches 30 days of abstinence. At the same time, employers must contend with the difficulty of establishing the benefits of a workplace policy that relies on existing cannabis testing technology and which, at best, identifies an unspecified level of consumption at some time during the preceding 30 days.

The employer thus faces a conundrum. On the one hand, the period of prohibited consumption can be shortened to align with current scientific evidence on the length of impairment. The policy will then be more difficult to enforce because existing testing technology cannot prove that the consumption took place during the shorter period. On the other hand, the period can be lengthened to 30 days to align with the limitations of existing testing technology. The policy will then be criticized because the longer period is not justified by current scientific evidence. Notwithstanding the significant challenges facing employers who pursue either option, it is the position of this paper that the policies are defendable under certain conditions.

Key Words:

- drug policy,

- privacy,

- workplace safety,

- unions

Résumé

En 2018, le Canada est devenu le premier pays du G7 à légaliser le cannabis à usage récréatif. Par conséquent, au moins une douzaine d’employeurs de premier plan dans des secteurs où la sécurité est primordiale ont mis en oeuvre des politiques visant à empêcher les travailleurs de consommer légalement du cannabis pendant de longues périodes avant de se présenter au travail, allant de 28 jours à une interdiction totale. Les divers syndicats qui représentent ces travailleurs allèguent une violation inutile de la vie privée des employés et ont l’intention de contester la légalité de ces politiques. Se basant sur des décisions de la Cour suprême et d’arbitrage en matière de relations du travail, le présent document propose un test adapté servant à évaluer l’applicabilité des nouvelles politiques relatives au cannabis en milieu de travail. Malgré les défis importants auxquels les employeurs doivent faire face, le présent document soutient que les nouvelles politiques sont applicables sous certaines conditions.

Sommaire

Se basant sur des décisions de la Cour suprême et d’arbitrage en matière de relations du travail, le présent document propose un test adapté servant à évaluer l’applicabilité des nouvelles politiques relatives au cannabis en milieu de travail, lesquelles interdisent la consommation légale de cannabis aux travailleurs effectuant des tâches où la sécurité est critique.

L’analyse décrit les deux principaux défis auxquels les employeurs doivent faire face.

Établir la présence d’un problème dans le milieu de travail. La consommation de cannabis doit avoir un effet perturbateur pendant la période d’interdiction.

Démontrer que la politique présente des avantages suffisants pour justifier ses conséquences. Les améliorations de la sécurité dans le milieu de travail doivent l’emporter sur l’atteinte à la vie privée des employés.

Pour cerner un problème dans un milieu de travail, les employeurs s’appuieront sur les preuves disponibles les plus probantes liant le cannabis à l’affaiblissement des facultés pendant la période où la consommation est interdite. La recherche médicale est utile à cet égard. Un ensemble substantiel de preuves souligne des déficiences motrices et cognitives importantes immédiatement après la consommation (les huit premières heures). Bien que certaines études démontrent une période prolongée d’affaiblissement des facultés, les preuves sont moins convaincantes lorsque l’utilisateur s’abstient de consommer pendant près de 30 jours. Par ailleurs, les employeurs doivent faire face à la difficulté d’établir les avantages d’une politique en milieu de travail qui s’appuie sur les tests actuels de dépistage du cannabis et qui, au mieux, détermine un niveau non spécifié de consommation au cours des 30 derniers jours.

L’employeur fait donc face à un dilemme. D’une part, la période de consommation interdite peut être raccourcie pour correspondre aux preuves scientifiques actuelles concernant la durée de l’affaiblissement des facultés. La politique sera alors plus difficile à appliquer, car la technologie des tests actuels ne pourra pas prouver que la consommation a eu lieu pendant la période plus courte. D’autre part, la période peut être allongée à 30 jours pour correspondre aux limites de la technologie des tests actuels. La politique sera alors critiquée parce que la période prolongée n’est pas justifiée par les preuves scientifiques actuelles. Malgré les défis importants auxquels se heurtent les employeurs qui choisissent l’une ou l’autre de ces options, le présent document soutient que les politiques sont applicables sous certaines conditions.

Mots clés:

- politique sur les drogues,

- confidentialité,

- sécurité au travail,

- syndicats

Article body

Introduction

On October 17, 2018, consumption of cannabis for recreational purposes became legal in Canada. For good reasons, managers responsible for workplace safety are worried about how legalization will impact existing workplace drug policies. In response, several Canadian employers in safety-sensitive industries are in the early stages of implementing new workplace rules to prohibit employees from consuming legal recreational cannabis. These policies prohibit consumption before the start of a work shift, and this period varies in length from policy to policy, typically ranging from 28 days to continual abstinence. For regular full-time employment, a period longer than a few weeks requires continual abstinence in practice, since an employee is never likely to be away from work for more than two weeks, even when taking an annual vacation.

In Canada, many safety-sensitive positions are unionized and therefore have a mechanism to challenge the new cannabis abstinence policies (CAPs) as an unjustified intrusion of employee privacy. Certainly, the parties may avoid a grievance by negotiating satisfactory language in their collective agreement ; to date this has not occurred. At the time of writing, the grievances are making their way through the initial stages of the internal dispute resolution processes in various organizations across Canada (e.g., see Mitchell 2018 or CBC News 2018a). This is uncharted legal territory. Given the potential hazard to the general public, the intrusion into employee privacy and the implications for other safety-sensitive industries (e.g., bus and truck drivers, heavy machine operators, surgeons, prison guards, etc.), the legal arguments will not take long to end up before labour arbitrators. Without considering the legal implications of enforcement (mandatory testing and storage of personal information) or the burden of a set of case facts, this article is an initial attempt to address the enforceability of workplace cannabis rules.

Prior to legalization, employers often relied on the legal classification of cannabis as a controlled substance, along with other drugs such as cocaine and opioids, to prohibit its use in the workplace. Often the illegality of the misconduct was just cause for discipline. There has nonetheless been an established line of reasoning according to which the illegality of such misconduct is not dispositive. Although it is a recent development for arbitrators to overlook the illegality of narcotic consumption when considering disability in cases involving human rights law, there is a history of arbitrators treating addiction to illegal drugs as a non-culpable offence, akin to innocent absenteeism, with particular emphasis on the employee’s rehabilitative potential (e.g., see British Columbia Telephone Co. and T.W.U. (1978), 19 L.A.C. (2d) 98). In the post-legalization era, existing drug policies no longer apply to cannabis. Thus, the new CAPs are appropriately understood as an attempt by employers to safeguard the workplace from risks associated with intoxication due to cannabis use, without circumventing the human rights considerations entrenched in labour jurisprudence.

Largely through labour arbitration and Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decisions on the acceptability of mandatory drug and alcohol testing, a jurisprudence has developed to guide future decision makers on how to balance workplace safety with employee privacy. By synthesizing key decisions from the jurisprudence, this paper proposes a custom-made test to assess the enforceability of CAPs. The proposed CAP Test is offered as an aid to the parties and to future decision makers for assessing the enforceability of a CAP, and will contribute to the scholarship on employee privacy rights. With respect to this test, several important considerations are discussed here, including workplace and medical research on the severity and length of impairment caused by cannabis and the limited detection technology currently available.

An obvious question should first be addressed : why not treat cannabis like alcohol ? After all, both are (now) legal and cause impairment, and there are effective and accepted alcohol policies already in place in safety-sensitive workplaces, such as fit-for-duty policy. The existing rules prohibit the consumption of alcohol during a short defined period leading up to the start of the work shift, typically 8 to 12 hours beforehand. Because unions have not contested alcohol fit-for-duty policies, we may infer that such policies are viewed as a reasonable breach of employee privacy. Two reasons contribute to their acceptability :

Evidence of the impairing effect of alcohol : The restriction imposed by fit-for-duty policy (8 to 12 hours) matches the medical and workplace evidence on the impairing effects of alcohol consumption.

Alcohol detection technology : Existing testing methods provide a means to enforce the fit-for-duty policy. Breathalyzer analysis detects blood alcohol levels and is regarded as an effective first detection method. Increased precision is then achieved with a more invasive blood extraction test. Both tests can detect blood alcohol levels that a substantial body of medical research has shown to cause impairment at specified levels. Furthermore, because the rate at which alcohol is eliminated from the bloodstream is fairly consistent from person to person, the test provides a sufficiently accurate measure of whether the alcohol was consumed during the period of prohibited consumption (8 to 12 hours before work).

So why not just treat cannabis like alcohol and apply a fit-for-duty policy that prohibits consumption for a period of time that matches the known impairment period ? Inconveniently, the above two justifications do not hold true for cannabis consumption.

Evidence of the impairing effect of cannabis : The existing medical and workplace evidence of the effects of cannabis consumption are reviewed in detail later in the paper, but for now it is sufficient to note that the research is in a preliminary stage and that there is no consensus within the expert community on which functions are impaired and how long the effect lasts.

Cannabis detection technology : Unlike the case with alcohol, there is no reliable way to determine impairment. Existing testing technology can only determine that some cannabis was consumed in the past 30 days. It cannot determine the amount consumed or provide a reliable indication of impairment, nor is it possible to determine when the cannabis was consumed during the 30-day period.

Although some organizations are implementing a cannabis fit-for-duty policy (see CBC News 2018b regarding the Ottawa Police Service), these limitations have led many employers in safety-sensitive industries to draft workplace policy that requires a more drastic restriction of cannabis consumption than is required for alcohol consumption. At the time of writing, at least a dozen prominent employers with safety-sensitive workplaces have implemented policies that prohibit consumption of cannabis for an extended period of time, ranging from 28 days (Toronto Police, see Shum 2018 ; and the RCMP, see Connolly 2018) to continual abstinence (Calgary Police, see Pearson and Ramsay 2018).[1]

Striking a Balance : Lessons from Mandatory Random Alcohol and Drug Testing Jurisprudence

Two important decisions serve as the basis of the accepted standard for balancing workplace safety and employee privacy : the longstanding KVP Test from a 1965 decision (KVP Co v Lumber & Sawmill Workers’ Union, Local 2537 (Veronneau Grievance), [1965] OLAA No 2) on the enforceability of a unilaterally imposed employer rule (as opposed to a rule agreed to by the union in collective bargaining) ; and the SCC’s evaluation of a mandatory random alcohol testing policy implemented by Irving Pulp and Paper Ltd in 2013 (Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Local 30 v. Irving Pulp & Paper, Ltd., [2013] 2 SCR 458.). Since these important decisions, the jurisprudence has widely applied an ‘Irving Informed KVP Test.’ This jurisprudence has been used to design the CAP Test.

The 1965 KVP Decision

Discipline is generally enforceable even when justified by a workplace policy that the employer has unilaterally imposed, instead of being negotiated through collective bargaining, provided it holds up to scrutiny. The validity of an employer rule was determined primarily by Arbitrator Robinson over fifty years ago in the KVP decision. Having stood the test of time, the KVP framework has been consistently applied by arbitrators and appeal courts, as well as the highest court in Canada. The SCC endorsed the KVP Test in Irving (ibid at para 24) as the “persuasive” standard on the scope of the employer’s right to impose workplace rules and again in 2017 as “[T]he well-established approach to determining whether a policy that affects employees is a reasonable exercise of management rights …” (Association of Justice Counsel v Canada (Attorney General), [2017] 2 SCR 456, at para 24).

According to the decision in KVP, if an employer rule has been implemented without the union’s consent, a violation of that rule will serve as just cause for discipline only if the rule is consistent with the collective agreement and is reasonableIn keeping with recent decisions that read employment legislation into the collective agreement, Canadian privacy legislation is considered later in the paper.[2]

The second principle of the KVP Test (i.e., that the policy should be reasonable) is the focus of most privacy grievances. Here the employer’s legitimate business interests are weighed against employee privacy. In general, the intrusion into employee privacy must be justified as reasonably necessary for advancing the employer’s interests, such as productivity, workplace safety or security or cost savings. A standard of proportionality has long been developed in the jurisprudence, whereby an employer is required to demonstrate a sufficient need for the intrusion on employee privacy. The standard of proportionality was refined and given its ultimate authority by the SCC in the 2013 Irving decision on mandatory alcohol testing.

The 2013 SCC Irving Decision

In Irving, the union sought leave for appeal from the SCC and succeeded in reinstating the original arbitration decision ; the random alcohol policy was ruled to be an unnecessary violation of employee privacy mainly because the employer failed to demonstrate a problem of alcohol abuse in the workplace. The SCC decision in Irving provides important guidance for assessing the reasonableness of employer rules that affect employee privacy within the framework of the accepted KVP standard of ‘reasonableness.’ Writing for the majority, Justice Abella explains the evidentiary burden on the employer to justify the need for a policy that compromises employee privacy :

A substantial body of arbitral jurisprudence has developed around the unilateral exercise of management rights in a safety context, resulting in a carefully calibrated ‘balancing of interests’ proportionality approach. Under it, and built around the hallmark collective bargaining tenet that an employee can only be disciplined for reasonable cause, an employer can impose a rule with disciplinary consequences only if the need for the rule outweighs the harmful impact on employees’ privacy rights. (at para 4)

The SCC decision in Irving is one part affirmation of the KVP Test and one part progressive directive for employing the ‘balancing of interests’ proportionality approach. Specifically, the SCC identified three necessities in Irving :

The workplace must be obviously dangerous ;

There must be evidence of a workplace problem ;

The breach of employee privacy must be offset by the benefits of the policy.

This is not to suggest that these considerations are absent from the pre-Irving jurisprudence. Certainly, they featured in the deliberations of adjudicators ; however, the SCC’s oversight provides affirmation and clarity, and thus guidance for subsequent challenges to employer policy on employee privacy.

Evaluating CAPs

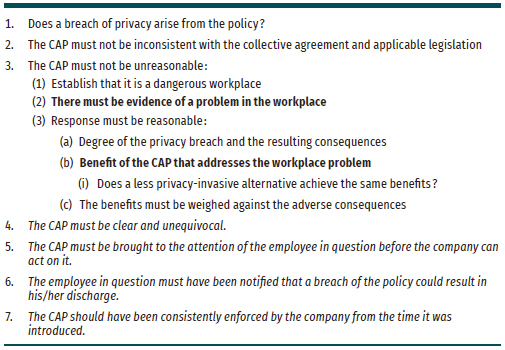

In Figure 1 the CAP Test is presented. It incorporates the KVP conditions for evaluating a rule imposed by the employer and the standard of reasonableness described in Irving by the SCC.

For a CAP to be judged enforceable, all of the conditions of the CAP Test must be met after being considered sequentially. Failure to meet a condition ends the analysis and renders the cannabis policy unenforceable. The bolded text (workplace problem and benefit of the policy) flags the conditions that are likely to attract the greatest debate and which are carefully explored in the subsequent analysis. Conditions 4 to 7 (italicized text) rely on the facts of the case and are not discussed.

Figure 1

The Irving-Informed KVP Privacy Test for Cannabis Abstinence Policy : The CAP Test

CAP Test Condition 1 : Does a breach of privacy arise from the policy ?

Employers will not likely deny that CAPs result in a breach of privacy. The new policies restrict a legal entitlement : consuming cannabis for recreational purposes. To defend a policy that violates employee privacy, the argument is generally not to deny the invasion of privacy but rather to justify it. The degree and consequences of the invasion of privacy form part of the ‘reasonableness’ analysis and is discussed later.

CAP Test Condition 2 : The policy must not be inconsistent with the collective agreement or applicable legislation

Setting aside unusual contract language to safeguard an employee’s prerogative to consume legal cannabis, it is not likely that unions will argue that a CAP is inconsistent with the collective agreement. However, as discussed earlier, this KVP principle is now being interpreted to make CAPs comply with applicable legislation.

A recent book on workplace law characterizes employee privacy rights in Canada as a “loose collection of concepts and doctrines that establish a sort of legal checkerboard” (Craig and Lindner 2016 : 438). Of all the sources of legal protection, privacy statutes, where they exist, have the greatest potential impact on determination of CAP enforceability. Less applicable here are other privacy-related statutes that are intended to regulate private information and which are therefore not considered by this paper.[3] Without discounting the importance of common law in informing arbitration decisions, tort and individual contract law rarely provide direct grounds for establishing precedence, especially in emerging areas of the law and in areas where employees enjoy the benefits of a grievance process (ibid : 438). Although the 2013 Irving decision considers the jurisprudence of human rights provisions that protect against discrimination on the grounds of disability as it relates to mandatory alcohol and drug testing in general, two older decisions are worth noting for the insight they provide into cannabis use in safety-sensitive employment.

Until the SCC articulated the three-stage proportionality approach (described above), the jurisprudence on drug and alcohol policies was fragmented, especially on cannabis policies. In 2000, the Ontario Court of Appeal issued a decision (Entrop v. Imperial Oil Ltd. 189 D.L.R. (4th) 14) confirming that a blanket prohibition of drug use is prima facie discriminatory on the grounds of disability. As a result, the employer now has to satisfy the bona fide occupational requirement (BFOR) to survive a challenge under human rights legislation (for a more complete review see Mitchnick and Etherington 2018 : 402). The decision expressly applied the same logic to mandatory pre-employment testing and declarations of abstinence. If mandatory testing and the requirement to declare drug use are considered discriminatory, it follows that a workplace rule to punish any consumption of cannabis would also violate human rights statutes and warrant a BFOR defence.

And yet cannabis is not so easily lumped together with other drugs. After all, the federal government legalized cannabis but not cocaine or any other narcotic almost certainly because a body of scientific evidence suggests it can be enjoyed in a safe and recreational manner. Along these lines, in a 2007 decision (Alberta (Human Rights and Citizenship Commission) v. Kellogg Brown & Root (Canada) Co. (2007), 289 D.L.R. (4th) 95) the Alberta Court of Appeal expressly declined to follow the logic used in Ontario in Entrop. Citing concern over the residual effects of cannabis use, mandatory pre-employment testing was declared an acceptable requirement in safety-sensitive positions. The employer was not subject to meeting a BFOR, since the Court did not consider cannabis users to be drug addicts ; therefore, they could not find refuge in a prohibition against discrimination on the basis of disability.

Since then, the Irving (2013) decision has clarified the obligations that an employer must meet to enforce blanket drug policy, such as mandatory drug testing. Furthermore, the Alberta Court of Appeal decision is regarded as an outlier, and certainly some levels of cannabis use have subsequently qualified as a disability for the purpose of obtaining protection from discrimination under human rights statutes (e.g., see Ottawa (City) and Ottawa-Carleton Public Employees Union, Local 503, ONSC 4072 (CanLII), [2013] O.J. No. 2721 (QL) 9 Ont. Div. Ct.). Despite the added considerations that come with recreational cannabis use, human rights laws are not likely to block CAPs, provided the employer meets the obligations outlined in Irving (2013).

In addition to human rights law, some jurisdictions rely on standalone privacy statutes ; four of the ten Canadian provinces have enacted privacy laws, but no such statute exists in the federal jurisdiction or the other six provinces. If a CAP is deemed consistent with legislation in jurisdictions with a standalone privacy statute, it will certainly be deemed so in jurisdictions without an equivalent act. For this reason, the analysis here will focus on the four existing provincial privacy statutes.

When considering the intent and scope of the provincial statutes, it is important to keep in mind that provincial legislators almost certainly did not anticipate the federal 2018 Cannabis Act, which legalized recreational cannabis ; Newfoundland and Labrador had last revised their legislation in 1996, British Columbia and Manitoba in 2008 and Saskatchewan more recently in 2018, although the amendments are limited to the distribution of intimate images. While these statutes do not specifically deal with CAPs, they provide some general protections for employees and guidelines for employers.

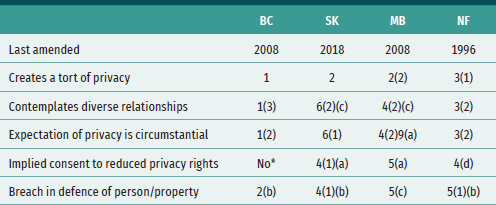

The four provincial standalone privacy statutes are remarkably similar. In Table 1, they are compared with reference to specific sections about five considerations that are used to assess CAPs.

Table 1

A Comparison of Privacy Legislation in Canada

*In BC (2(a)), ‘implied consent’ is not mentioned but obtaining ‘consent’ (without specifying express or implied) is an enumerated defence for a breach of privacy.

Likely the most significant effect of the privacy statutes has been to create the tort of invasion of privacy, which is not an absolute right and may be infringed upon for an acceptable reason. Section 3(1) of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Privacy Act has language that is representative of all four statutes :

3.(1) It is a tort, actionable without proof of damage, for a person, willfully and without a claim of right, to violate the privacy of an individual.

This provision provides employees with grounds to object to an action that violates their privacy, on its face, and without the need to demonstrate that the act caused a consequence. With respect to a CAP, an expectation of privacy is identified ; however, it is not an absolute right and, under certain circumstances, “a claim of right,” such as workplace safety, can likely be established to justify a breach of employee privacy.

Notice that the language that creates a tort of invasion of privacy considers only the ‘person to person’ relationship (this is also the case in the other three statutes). It is reasonable to question whether this language is sufficiently inclusive to capture the relationship between an employer and an employee. It appears so ; the Saskatchewan Privacy Act, which is similar to the other statutes, clearly contemplates a diverse array of relationships :

-

6(2) … regard shall be given to :

(c) any relationship whether domestic or otherwise between the parties to the action ; and…

Although the legislation does not specifically reference the employment relationship, it does describe the privacy rights of individuals engaged in ‘any relationship,’ which would logically include the employment relationship.

Next, it is relevant to note that privacy entitlements are conditional on the circumstances of the relationship. Of interest is whether an employer may argue, based on the privacy statute, that an employee has a diminished expectation of privacy by entering into an employment relationship. Indicative of the other statutes, Newfoundland and Labrador’s act states :

3.(2) The nature and degree of privacy to which an individual is entitled in a situation or in relation to a matter is that which is reasonable in the circumstances, regard being given to the lawful interests of others ;…

This language does appear to support the argument that employers are potentially entitled to restrict the off-duty activities of employees in safety-sensitive positions when workplace safety is compromised.

There is a further consideration related to a potential reduced expectation of privacy. If an employee signs an employment contract to perform a safety-sensitive job does that person thereby give implied consent to a reduced expectation of privacy ? For instance, when a person accepts a job as a commercial airplane pilot, is it reasonable to assume that he or she recognizes that some legal off-duty conduct will be prohibited, such as consuming cannabis ? In general, the statutes appear to provide the basis for a justification of implied consent. In all acts except British Colombia’s, consent need not be expressly given but may be implied by the circumstances, such as entering into an employment relationship. For instance, the Privacy Act of Manitoba holds :

-

5. In an action for violation of privacy of a person, it is a defence for the defendant to show

(a) That the person expressly or by implication consented to the act, conduct or publication constituting the violation ; or… (emphasis added)

A final observation relates to the justification that an employer is responsible for protecting the property and safety of employees and the general public. The Privacy Act of British Columbia reads :

-

2. An act or conduct is not a violation of privacy if any of the following applies :

(b) the act or conduct was incidental to the exercise of a lawful right of defence of person or property ;

While this may read as being intended to protect the lawful use of surveillance cameras, it may be more encompassing if we consider the language in all four statutes. Manitoba’s statute reads :

-

5. In an action for violation of privacy of a person, it is a defence for the defendant to show

(c) That the act, conduct or publication at issue was reasonable, necessary for, and incidental to, the exercise or protection of a lawful right of defence of person, property, or other interest of the defendant or any other person by whom the defendant was instructed or for whose benefit the defendant committed the act, conduct of publication constituting the violation ; or….

This additional language suggests a wider scope of adequate defences and lends support, at least in principle, to prohibition of cannabis in order to protect workplace safety.

In sum, analysis of the four provincial privacy statutes leads to six observations, all of which support the abstract concept that an employee’s right to privacy is subject to reasonable limitations. CAPs thus seem to be consistent with the applicable privacy legislation. The observations are listed below.

The legislation creates a tort of invasion of privacy but places limits on employee privacy entitlements.

The legislation contemplates a diverse array of relationships, which reasonably could include the employment relationship.

Regard is given to the special conditions and responsibilities of specific relationships, such as an employer’s interest in protecting company property and especially the safety of employees and the general public.

A person’s expectation of privacy is mediated by the circumstances of the situation ; hence, an employee in a safety-sensitive position should reasonably expect some employer oversight of off-duty conduct whenever workplace safety is compromised.

The legislation recognizes that an employee may provide consent (even implied consent in three of the four statutes) for reduced privacy rights by virtue of entering into an employment contract for a safety-sensitive position.

The legislation expressly mentions the protection of persons and property as an acceptable defence for a breach of privacy, thus supporting the employer’s assertion that the privacy breach that arises from a CAP is justified by the need for workplace safety.

Given these six observations, a CAP is not likely to be found in violation of the four provincial privacy statutes, where they have authority, provided it meets the other CAP Test conditions and is reasonable. In the federal jurisdiction and the five provinces without a privacy statute, the legislated privacy protections are weaker, and a CAP is even less likely to contravene legislated employee privacy entitlements.

CAP Test Condition 3(1) : A danger must be shown to exist in the workplace

Where CAPs have been introduced, the unions are not likely to dispute the safety-sensitive status of the workplace. To date, CAPs have been limited to occupations with an established history of safety-sensitive classification, such as commercial airplane piloting, air traffic control, parts of the armed forces, the rail transport industry and law enforcement. When the unions that represent these workers file grievances against unilaterally imposed policies that breach employee privacy, they have not disputed the safety-sensitive nature of the workplace.

CAP Test Condition 3(2) : There must be evidence of a problem in the workplace

To demonstrate that a workplace has a cannabis-related problem, the employer must meet at least one requirement and possibly a second. At a minimum, the employer must show that cannabis is impairing performance to the point of becoming a concern in safety-sensitive jobs and that the length of the period of prohibited consumption is justified by evidence of an impairing effect equal in duration. In addition, the employer may also be required to demonstrate that the workplace suffers from a greater-than-normal cannabis problem. Employers defending mandatory random testing policies have been consistently required to demonstrate an actual drug or alcohol problem in the workplace (e.g., see the SCC commentary in Irving (at para 6) and more recently in Suncor (Unifor Local 707A v Suncor Energy Inc, [2017] SCCA No 445)). The potential requirement to establish an existing cannabis problem in the workplace is discussed after the evidence on impairment is assessed.

In the post-legalization era, when a grievance is filed against a CAP, the onus falls on the employer to establish a connection between cannabis consumption and impairment during the entire period of prohibited consumption. Research on the effects of cannabis is at a very early stage, and most experts agree that much more enquiry is required before the degree and length of impairment can be described with an acceptable level of certainty. Dr. Adams, a leading Canadian expert writes “… the actions of marijuana are extremely complex and nuanced.” He explains that cannabis is not a “sledgehammer” drug like alcohol and that its effects during the different phases of post-consumption are often subtle and may be overlooked if the appropriate experimental design is not employed :

It will take a combination of data, constantly evolved and re-examined, to make intelligent statements about this drug. Laboratory human performance data are only part of the puzzle, and equally intriguing are analysis of accident data in the real world.”.

Adams 2017 : 2

The existing research largely comes from medical scholarship ; however a limited number of driving and workplace studies exist. The driving studies have yielded mixed results. One comprehensive study of superior design published in 2016 reports that unlike alcohol, which was detected at a higher frequency in drivers involved in a crash, cannabis was not found at a significantly higher frequency after controlling for gender, age, race/ethnicity and the presence of alcohol (Lacey et al.). In contrast, an analysis of eleven peer-reviewed studies, finds “…a robust risk increase, exceeding a doubling of the risk, with cannabis consumption for the outcome of road traffic collisions” (Els et al. 2019). Another review study, by Asbridge et al. (2012), reports a similar twofold increase in risk.

While these studies are helpful for understanding the effect of cannabis on job tasks that demonstrably resemble the tasks required for driving, they do not necessarily imply a detrimental effect on workplace safety. For instance, a police officer who scores worse on a driving simulation test after consuming cannabis may still be within the acceptable range of driving performance : the officer may be a split second slower in responding to a road hazard but still quick enough to safely conduct a high-speed chase. To get around this limitation, researchers would need to administer cannabis to a group of safety-sensitive workers and observe actual workplace performance by counting the resulting accidents, injuries and fatalities. As you can well imagine, ethical considerations make this more direct method unfeasible. One lone item of workplace research is available : the National Cannabis Survey of Statistics Canada (2019) provides evidence that daily users are over three times more likely to report to work impaired (self-assessed) than are non-daily users (27 % and 7 %, respectively).

Medical Evidence of Impairment

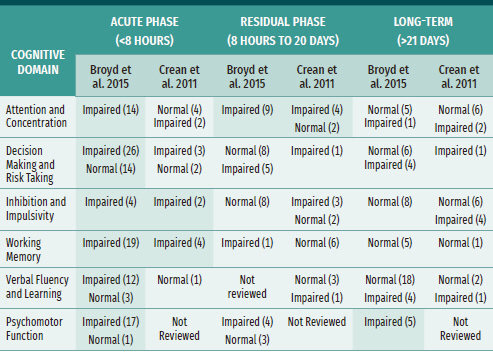

Two systematic meta-analyses offer a useful window on an emerging area of medical research. In a review published in the Biological Psychiatry Journal, Broyd et al. (2015) used key search terms to identify 105 relevant studies in a database of reputable academic peer-reviewed journals.[4] A second meta-analysis published a few years earlier by Crean et al. (2011) in the Journal of Addiction Medicine used a more restricted list of search terms and identified 66 relevant studies. Although 17 studies are reviewed in both meta-analyses, the two studies target different, though partially overlapping, areas of medical research. Broyd et al. focus on medical and psychiatric studies, and Crean et al. on addiction and mental health research.

Together these two meta-analyses provide a thorough review of medical scholarship. The impairing effect of cannabis is examined across different aptitudes, from basic motor coordination to more complex cognitive functions, such as ability to maintain attention and concentration on one or more tasks, capacity to make critical decisions, propensity for impulsive and risky behaviours and effectiveness of working memory and verbal fluency. All of these capacities are ostensibly important for the satisfactory performance of a safety-sensitive job. For instance, a pilot must control a plane’s instruments with a steady hand while processing multiple sources of mechanical and meteorological information, and while making critical real-time assessments of competing strategies to minimize risk in the event of an emergency. Similarly, police officers are expected to operate a vehicle, sometimes at excessive speeds, in addition to confronting dangerous suspects and making split-second decisions on the appropriate use of force. A mistake may have lethal consequences. Similar risks exist for other safety-sensitive jobs.

Table 2 summarizes medical findings on the cognitive effects of cannabis. With a high degree of consistency, the studies differentiate the post-consumption period into three phases : an acute phase (first six to eight hours) ; a residual phase (up to 20 days) ; and a long-term phase, understood as lasting 21 days or more of abstinence. The number of studies finding each effect is given in parentheses.

Table 2

Medical Evidence of the Cognitive Effects of Cannabis during Three Phases of Post-Consumption

The number of studies identifying a specific effect is given in brackets. Shaded cells denote at least a partial consensus in the literature that an impairing effect is observed. A partial consensus is identified where more than twice as many studies report ‘Impaired’ as those that report ‘Normal.’ The time periods given for each phase (in brackets) are approximations ; some variation across studies exists.

Acute Phase

A substantial body of evidence suggests an impairing effect on a wide range of cognitive domains within the first six to eight hours after consumption. Several studies find the impairing effect to be stronger in less experienced users than in those with an established physical and mental drug tolerance. Interestingly, the more experienced users suffer greater disruption to their attention and concentration from acute abstinence than from acute consumption. Overall, there is strong evidence that cannabis has an impairing effect on several executive cognitive functions that are arguably critical for safety-sensitive employment, such as decision making and risk taking, inhibition and impulsivity, working memory, verbal fluency and learning, and psychomotor functions that require coordination and fine motor skills.

Residual Phase

The residual phase begins after the acute phase and ends up to approximately 20 days after consumption. During this phase, attention and concentration appear to be the domains the most associated with lingering impairment as the body eliminates cannabis from the body. Interspersed among studies showing no observable effect on decision making and risk taking are six that report lasting impairment, including a highly cited gambling experiment by Whitlow et al. (2004). There is limited evidence that psychomotor functions are diminished and, in contrast to the observable impairment during the acute phase, the evidence points to a recovery of inhibition and impulsivity, working memory, and verbal fluency and learning. The greatest deficiencies in executive functions during this phase are shown in studies whose subjects had been consuming heavy doses of cannabis over a longer period (Crean et al. 2011). Thus, it is abstinence from heavy use that appears to have negative effects on psychomotor functions.

Long-Term Phase

As a typical cannabis user reaches approximately three weeks of abstinence, the evidence indicates a restoration of the majority of cognitive functions, including attention and concentration, both of which were, to some extent, observed to be impaired in the residual phase. However, a limited number of studies point to two domains where deficiencies continue to be observed. Five studies note a long-lasting effect on psychomotor skills and, together with the studies finding impairment during the residual phase, there is good reason to suspect an effect lasting 21 days or longer. Findings are mixed concerning the long-term effect on decision making. Where decision making is observed to be impaired, the impairment is in subjects with a history of heavy and chronic cannabis use, whereas lighter and more short-term users demonstrate a return of normal decision-making functions.

Summary of the Impairment Evidence

There is strong evidence that users experience compromised executive and psychomotor function during the first eight hours after consumption. Cognitive performance returns to normal between eight hours and 20 days of abstinence but attention and concentration remain disrupted as the effects of withdrawal are observed. Ongoing impairment appears to be strong in heavy and chronic users struggling with the effects of withdrawal. Normal cognitive performance is reported to return after 21 days of abstinence ; however, there is limited evidence that psychomotor functions continue to be negatively impacted.

An Additional Consideration : Evidence of an Existing Cannabis Problem in the Workplace

The design of the CAP Test is largely informed by the jurisprudence on mandatory random testing. In these cases, and especially in the recent Suncor SCC decision (supra), the award was heavily influenced by the employer’s ability to demonstrate a general problem in the workplace. This requirement is necessary to justify a new intrusion on employee privacy that is not otherwise justified by the evidence of safety risks associated with impairment (i.e., mandatory random testing for non-drug users). To justify testing non-drug users, the employer must show that the average worker in a particular workplace, even among those who claim to abstain from drugs, has a reasonable chance of testing positive.

This requirement may be unnecessary to justify CAPs, since non-cannabis users suffer only a minor new intrusion on their privacy : the choice to abstain is replaced with a rule requiring abstinence. This distinction and the resulting privacy invasion is small and is not likely to justify placing an evidentiary burden on the employer to demonstrate a general workplace problem, as is the case with mandatory random testing.

Cap Test Condition 3(3) : The response must be reasonable

Further to the SCC decision in Irving, the reasonableness of a CAP is assessed in three stages : examine the degree of the privacy breach and the resulting consequences ; evaluate the proposed benefits of the policy ; and weigh the adverse consequences against the benefits.

(a) Degree of the privacy breach and the consequences

When enacted in 2018, the Cannabis Act legally entitled Canadians to consume cannabis for recreational purposes. CAPs cause a breach of employee privacy by prohibiting a legal activity. To understand the consequences, it is helpful to examine employees at the extremes of the cannabis consumption spectrum : heavy users and non-users. For heavy chronic consumers, an abstinence requirement may pose a significant hardship : they may turn to other harmful vices, such as alcohol or unhealthy food ; they may lose friends and even feel unwelcome in social activities where cannabis plays a prominent role ; furthermore, the pleasure some derive from being under the influence of cannabis should not be understated. A Canadian study summarizes the main reasons why respondents reported consuming cannabis :

Today, people often use cannabis for specific activities and occasions. When used properly, it helps some to relax and concentrate, making many activities more enjoyable. Eating, listening to music, socializing, watching movies, playing sports, having sex and being creative are some things people say cannabis helps them to enjoy more. Sometimes people also use it to make mundane tasks like chores more fun.

Osborne and Fogel 2008

As noted in the previous section, the consequences for non-users are minor : they are required by a workplace rule to abstain, rather than being permitted to continue choosing to abstain. This is a small distinction, but one not without consequences for some non-users ; some may feel disrespected and judged incapable of making appropriate lifestyle decisions by an overly paternalistic employer and/or lose the value derived from making a decision (not to consume) that they perceive as demonstrating responsibility and commitment to health, work, family, etc… Without discounting the potential consequences for a small proportion of non-users, the overall effect on non-users is likely to be judged minor. Although this paper evaluates CAPs without considering the realities of enforcement, which almost certainly necessitate some level of mandatory testing, it should be noted that non-users will be subject to saliva or blood tests and will thus experience some hardship.[5]

Having charted the consequences for the extremes : heavy users and non-users, it is appropriate to consider the cannabis consumption habits of the average safety-sensitive worker who likely lies somewhere in-between. There is no available evidence on the consumption patterns of safety-sensitive workers ; however, the National Cannabis Survey conducted by Statistics Canada reports that when asked about consumption in the past three months 5.2 percent of Canadians reported using cannabis once or twice, 1.8 percent monthly, 3.4 percent weekly and 5.6 percent daily or almost daily (Statistics Canada 2019). If the cannabis consumption patterns of the general population are similar to those of safety-sensitive workers, approximately 84 percent would be non-users. The remaining 16 percent would consume some cannabis and a third of them would use it daily (or almost daily). The consequences of CAPs for daily users would be significant and more modest for those who consume it less often.

(b) Benefits of a CAP in addressing a problem in the workplace

In defending CAPs, employers will surely promote the benefits : a reduction in cannabis-related impairment, which in turn will result in a safer workplace. They will evoke a hypothetical disaster to illustrate the magnitude of the harm that could arise from an impaired worker’s diminished performance in a safety-sensitive position. Plane crashes, out-of-control heavy machinery and high-speed police chases ending in fatality are not trivial workplace incidents that can be easily dismissed out of concern for employee privacy. However, a CAP is effective in promoting safety only if it is enforceable. Employers must have a method to catch offenders ; they must identify cannabis-related impairment and determine that the consumption took place during the period of prohibited consumption.[6]

Unlike alcohol fit-for-duty policies, CAPs cannot be enforced by using an accepted measurement of impairment and an accepted test to detect impairment and estimate the quantity and time of consumption (Health Canada 2016 : 41). Because cannabis metabolites are detectable for many days and even weeks after cessation of use, a positive drug test result does not imply impairment ; instead, it merely establishes that some cannabis has been consumed, likely in the past 30 days (Reis et al. 2014 : 217). Furthermore, because serum levels of cannabis poorly correlate with impairment, there is no reliable way to test for the latter (Health Canada 2016). A leading Canadian medical expert has recently explained that work is proceeding urgently on developing an acceptable test ; nonetheless, it is his position “…that attempting to find a particular blood level of THC or cannabinoids at which an individual might be viewed as impaired, or not impaired, is not a practical or useful goal to pursue in ensuring worker safety and fitness to work” (Adams 2017 : 12).

In the limited number of labour arbitration decisions that have relied on cannabis testing results, arbitrators question the validity of the existing cannabis testing technology (Lam 2019). For example, very early in the drug testing jurisprudence the Ontario Court of Appeal commented :

… drug testing suffers from one fundamental flaw. It cannot measure present impairment. A positive drug test shows only past drug use. It cannot show how much was used or when it was used.

Entrop v Imperial Oil Ltd], 50 OR (3d) 18, at para 99

In this case, the imposed workplace policy (random testing for drugs) was deemed unreasonable partly because the testing method was not valid, given its inability to measure actual impairment. This assessment has never been disputed by subsequent reviewing courts. For employers defending CAPs, the limitations of existing drug testing technology will pose a challenge.

(b)(i) Is there a less privacy-invasive alternative that produces the same benefit ?

Notwithstanding the evidence of cannabis impairment during different phases of post-consumption, an arbitrator is likely to consider a shorter period of prohibited consumption as a less privacy-invasive alternative. As noted above, medical research provides two sets of findings : 1) impairment during the acute phase in all users ; and 2) withdrawal-associated impairment of heavy users during the residual and long-term phases.

Accordingly, an alternative policy that may produce a similar benefit but cause a slighter breach of privacy is to prevent an employee from consuming cannabis during a shorter period that equals the length of time from the end of the work shift to the beginning of the next one when scheduled to work on consecutive days, thus eliminating the performance deficiencies during the acute phase and preventing the employee from engaging in chronic/heavy use. Such a policy would eliminate the withdrawal effects associated with impairment of heavy users during the residual and long-term phases. In keeping with the requirements of the proposed CAP Test, a policy with a shorter period of prohibited consumption would still need to be justified and would be highly dependent on the specific safety concerns of the affected jobs.

(c) Weigh the benefits against the adverse consequences

While employee privacy has long been protected by legal decisions, the SCC has noted that an employee’s right to privacy is “a core workplace value, albeit one that is not absolute” (Irving at para 82 citing Trimac Transportation Services – Bulk Systems v Transportation Communications Union, [1999] CLAD No 750, at para 42). In other words, while an employee’s expectation of privacy is worthy of legal protection, it must be weighed against the employer’s needs.

Conclusion

To ensure a necessary standard of fairness, the CAP Test imposes a number of broadly accepted conditions : establish a breach of privacy (Condition 1) ; show consistency with the collective agreement and applicable statutes (Condition 2) ; and identify the workplace as dangerous (Condition 3.1). These conditions are necessary and will certainly make further analysis unnecessary if any cannot be met. A CAP is enforceable if there is evidence of a problem in the workplace (Condition 3.2), if impairment has adverse consequences (Condition 3.3(a)) and if the benefits of the policy outweigh the adverse consequences of not having one (Condition 3.3(b)).

To identify a problem in the workplace, employers will rely on the strongest available evidence linking cannabis to impairment for the entire period of prohibited consumption. The medical research is helpful in this regard. A substantial body of evidence points to significant motor and cognitive deficiencies immediately following consumption (first eight hours). Although some studies indicate a prolonged period of impairment, the evidence is less compelling as a user approaches 30 days of abstinence. At the same time, employers must consider the limitations of existing cannabis testing technology, which, at best, can identify an unspecified level of consumption at some time during the preceding 30 days.

Thus, the employer is faced with a dilemma. On the one hand, the period of prohibited consumption can be shortened to align with the scientific evidence on the length of impairment. The policy will then be harder to enforce because existing testing technology cannot prove that the consumption took place during the shorter period. On the other hand, the period of prohibited consumption can be lengthened to 30 days to align with the limitations of existing testing technology. The policy will then be criticized because there is little scientific evidence to justify the longer period. Either way, the employer is faced with a considerable challenge. It is nonetheless the position of this paper that CAPs are defendable, provided the right case facts are at hand and the appropriate arguments are made at arbitration. The jurisprudence does not require a flawless policy, just one that does more good than harm.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Although not intended to be an exhaustive list, a search of media reports conducted in November 2019 offers insight into the prevalence of the types of cannabis workplace policies being contemplated by the police, the military, the aeronautics industry and the rail transport industry. Please contact the author for a list of all the media reports consulted. Organizations considering a total ban on cannabis : Calgary, Edmonton, Gatineau and Windsor Police Services, the Canadian Armed Forces, Air Canada ; Jazz Air ; WestJet ; CN, VIA, CP Rail ; Metrolink/Go Transit. Organizations contemplating an extended period of prohibited consumption : Toronto and Halifax Police Services, and the RCMP (28 days) ; and Timmins Police Service (24 hours). Organizations considering a fit-for-duty policy : Hamilton, Winnipeg, Regina, Saskatoon, Vancouver, Montreal, Quebec City, Niagara Regional, Thunder Bay, and Peel Regional Police Services.

-

[2]

The leading authorities are cited by the Arbitrators Andy Simms and Allen Ponak ; see David Thompson Health Region v United Nurses of Alberta, Local 2 (Absenteeism Policy Grievance), [2009] AGAA No 57, at para 24) ; and Prairie North Health Region v Canadian Union of Public Employees, Local 5111 (Employee Name Tags Grievance), [2015] SLAA No 17, at para 135.

-

[3]

PIPEDA (Personal Informational Protection and Electronic Documents Act) introduced information privacy law into the federally regulated private sector in 2001.

-

[4]

The studies reviewed by Broyd et al. (2015) include samples of adults and youths (up to 19 years of age). This age range is problematic for drawing conclusions about safety-sensitive workers, who are almost exclusively over the age of 19 years. Considering the strong evidence of cannabis impairment in youth samples (see Camchong et al. 2016), there may be a potential for sample bias, i.e., the effects on safety-sensitive workers may be overstated. Therefore, all studies examining exclusively samples of youths or using mixed samples but not controlling for age have been excluded from the evidence reported here. Conveniently, the review of 66 studies by Crean et al. (2011) excluded all studies involving samples that included adolescents.

-

[5]

The appropriateness of mandatory drug testing is explored elsewhere ; the leading authority, Arbitrator Francis, puts forward a six-stage test to show when mandatory testing is reasonable despite employee or union objections. Please see Weyerhaeuser Co. and CEP, Local 447, 2012 CanLII 77353, 225 L.A.C. (4th) 294 (Francis).

-

[6]

It is unlikely that an employer could demonstrate before an arbitrator that an employee consumed cannabis, let alone was intoxicated, without an approved detection test. Unlike the case with alcohol, cannabis intoxication is difficult to identify, especially in experienced users. Dr. Adams, a leading Canadian expert explains :

Because our society is most familiar with alcohol, and its acute and subacute effects, we tend to generalize our understanding of the concepts of “impairment”. Alcohol is known to adversely affect fine motor and gross motor control. Hence an individual who is acutely intoxicated by alcohol will be slurring his speech because of the loss of fine motor control governing the lips/mouth/tongue, and weaving, because of loss of gross motor control. Neither of these are significantly impacted by marijuana, hence the common observation “he was not impaired because he was not slurring his speech or weaving”. As the discussions above reveal, the impairment caused by marijuana is typically more subtle and of higher function than that caused from alcohol. (Adams 2017 : 14)

References

- Adams, Brendan (2017). Marijuana and the Safety Sensitive Worker. A Review for CLRA. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2d4a/2c33884903acee1d069b8ce43c4486c9ad27.pdf, (September 10, 2019).

- Asbridge, Mark, Jill Hayden and Jennifer Cartwright (2012). “Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk : systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis.” BMJ, 344, e536.

- Broyd, Samantha, Hendrika van Hell, Camilla Beale, Murat Yuecel and Nadia Solowij (2016). “Acute and chronic effects of cannabinoids on human cognition—a systematic review.” Biological Psychiatry, 79(7), 557-567.

- Camchong, Jazmine, Kelvin Lim and Sanjiv (2016). “Adverse effects of cannabis on adolescent brain development : a longitudinal study.” Cerebral Cortex, 27(3), 1922-1930.

- CBC News (2018a). Ban on off-duty cannabis use for Metrolinx workers ‘extremely disappointing,’ union says. Posted on January 29, 2019. Retrieved from : https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/metrolinx-pot-ban-employees-1.4994796 (November 20, 2019)

- CBC News (2018b). Ottawa police allowed to use cannabis off-duty. Posted October 2018. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ottawa-police-officers-allowed-to-use-cannabis-off-duty-1.4846162 (November 20. 2019)

- Connolly, Amanda (2018). Mounties will be barred from smoking pot almost a month prior to any shift. Global News. Posted on October 12, 2018. Retrieved from : https://globalnews.ca/news/4529324/rcmp-cannabis-legalization-policy/ (November 20, 2019)

- Craig, John and Justine Lindner (2016) “Privacy Law at Work.” In David Doorey, The Law of Work : Common Law and the Regulation of Work. Toronto : Emond, 437-448.

- Crean, Rebecca, Natania Crane and Barbara Mason (2011). “An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions.” Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(1), 1.

- Drug and Alcohol Crash Risk : A Case-Control Study. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Office of Behavioral Safety Research.

- Els, Charl, Tanya Jackson, Ross Tsuyuki, Henry Aidoo, Graeme Wyatt, Daniel Sowah, … & Chris Stewart-Patterson, C. (2019). “Impact of Cannabis Use on Road Traffic Collisions and Safety at Work : Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Canadian Journal of Addiction, 10(1), 8-15.

- Health Canada (2016). Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation. A framework for the legalization and regulation of cannabis in Canada : the final report of the task force on cannabis legalization and regulation. Retrieved from : https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/laws-regulations/task-force-cannabis-legalization-regulation/framework-legalization-regulation-cannabis-in-canada.html (November 20, 2019)

- Lacey, John, Tara Kelley-Baker, Amy Berning, Eduardo Romano, Anthony Ramirez, Julie Yao, Christine Moore, Katharine Brainard, Katherine Carr, Karen Pell and Richard Compton (2016). Drug and alcohol crash risk : A case-control study (No. DOT HS 812 355). United States. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Office of Behavioral Safety Research.

- Lam, Helen (2019). “Marijuana Legalization in Canada : Insights for Workplaces from Case Law Analysis.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 74(1), 39-65.

- Mitchell Don (2018). Toronto police union boss says 28 day ban on pot ‘is simply not practical’. Posted on October 13, 2018. Global News. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/4545159/pot-ban-toronto-police-union/ (November 20, 2019)

- Mitchnick, Mortan and Brian Etherington (2018). Labour Arbitration in Canada. Lancaster House.

- Osborne, Geraint and Curtis Fogel (2008). “Understanding the motivations for recreational marijuana use among adult Canadians.” Substance Use & Misuse, 43(3-4), 539-572.

- Pearson, Heidie and Caley Ramsay (2018). Calgary police officers to be banned from consuming marijuana off duty. Global News. Posted on October 15, 2018. Retrieved from : https://globalnews.ca/news/4490716/calgary-police-officers-cannabis-ban/ (November 20, 2019)

- Ries, Richard, David Fiellin, Shannon Miller and Richard Saitz (2014). The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine. 5th Ed. Seattle : Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Shum, David (2018). Toronto police to ban officers from consuming cannabis within 28 days of reporting for duty. Global News. Posted on October 9, 2018. Retrieved from : https://globalnews.ca/news/4531051/cannabis-toronto-police-consumption-policy/ (November 20, 2019).

- Statistics Canada (2019). Table 4, Frequency of cannabis use among past-three-month users, by gender and age group, household population aged 15 or older, Canada, first quarter 2018 and first quarter 2019. National Cannabis Survey. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190502/t004a-eng.htm (October 28, 2019)

- Whitlow, Christopher, Anthony Liguori, Brooke Livengood, Stephanie Hart, Becky Mussat-Whitlow, Corey Lamborn, … & Linda Porrino (2004). “Long-term heavy marijuana users make costly decisions on a gambling task.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 76(1), 107-111.

List of figures

Figure 1

The Irving-Informed KVP Privacy Test for Cannabis Abstinence Policy : The CAP Test

List of tables

Table 1

A Comparison of Privacy Legislation in Canada

Table 2

Medical Evidence of the Cognitive Effects of Cannabis during Three Phases of Post-Consumption

The number of studies identifying a specific effect is given in brackets. Shaded cells denote at least a partial consensus in the literature that an impairing effect is observed. A partial consensus is identified where more than twice as many studies report ‘Impaired’ as those that report ‘Normal.’ The time periods given for each phase (in brackets) are approximations ; some variation across studies exists.

10.7202/1059464ar

10.7202/1059464ar