Abstracts

Summary

The purpose of this article is to highlight the role that Izzat played in the unfolding industrial disputation that emerged at the Toyota plant in Bangalore between 1999 and 2007. Isolated instances contributed to a build-up of employee and community resentment at what was perceived as an attack on Izzat. Behind the events is the attempt to transpose Japanese “lean production and management systems” into an Indian subsidiary where local industrial and cultural conditions were not suitable for the imposition of such practices from headquarters to a subsidiary.

The result of the analysis contributes to the understanding of workplace industrial relations (IR) in India and the centrality of Izzat. Within India, the significance of trade unions; the respect of employees; the importance of family and community; the importance of seniority; and the role of respect and honour are factors that multinationals often fail to understand in the design and implementation of their production and HRM systems.

The study contributes to the debate over the transferability of standardized HRM policies and practices. MNEs should play a proactive role in supporting the employees of subsidiaries to adjust to and accommodate new paradigms in workplace industrial relations. The aggressive production and HRM practices at the Toyota plant were not compatible with the norms and cultural institutions of the Indian workforce. One of the key implications of this research is that foreign production, organizational and industrial relations systems and practices cannot be transplanted into host-country environments without the due recognition of key cultural conditions, notably Izzat in India.

Keyworks:

- Izzat,

- India,

- auto production,

- workplace conflict,

- employee resistance

Résumé

Le but de cet article est de faire ressortir le rôle joué par l’Izzat dans le développement d’un conflit de travail qui s’est déroulé à l’usine Toyota de Bangalore entre 1999 et 2007. Des incidents isolés ont contribué à une accumulation du ressentiment des employés et de la communauté envers ce qui a été perçu comme une attaque contre le code d’honneur Izzat. En toile de fond de ces évènements se trouve la tentative de transposer à une filiale indienne les systèmes de production et de gestion en flux tendu (lean production) japonais, alors que les conditions industrielles et culturelles locales ne se prêtaient pas à une imposition de telles pratiques par le siège social.

Le résultat de l’analyse contribue à la compréhension des relations de travail en Inde et du rôle central d’Izzat. En Inde, l’importance des syndicats, du respect des employés, de la famille et de la communauté, de l’ancienneté, tout comme des notions de respect et d’honneur constituent des facteurs dont les multinationales n’arrivent souvent pas à saisir lors de la conception et la mise en oeuvre de leurs systèmes de production et de gestion des ressources humaines.

L’étude se veut une contribution au débat sur la transférabilité des politiques et des pratiques standardisées de GRH. Les entreprises multinationales devraient jouer un rôle proactif en aidant les employés de leurs filiales à s’ajuster et à s’adapter à de nouveaux paradigmes en relations industrielles sur les lieux de travail. Les pratiques agressives de production et de gestion des ressources humaines à cette usine de Toyota n’étaient tout simplement pas compatibles avec les normes et les institutions culturelles de la main-d’oeuvre indienne. L’une des principales implications de cette recherche est que les systèmes étrangers de production, d’organisation et de relations industrielles ne sauraient être transplantés dans l’environnement du pays hôte sans la reconnaissance explicite de conditions culturelles clés, notamment d’Izzat en Inde.

Mots-clés:

- Izzat,

- Inde,

- production automobile,

- conflit industriel,

- résistance des employés

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es esclarecer el rol jugado por el Izzat en el desarrollo de un conflicto de trabajo ocurrido en la fábrica Toyota de Bangalore entre 1999 y 2007. Los incidentes aislados contribuyeron a una acumulación de resentimiento de los empleados y de la comunidad contra lo que sido percibido como un ataque al código de honor Izzat. Detrás de dichos acontecimientos se encuentra la tentativa de transponer los sistemas japoneses de producción y gestión racionalizadas (lean production) a una empresa filial india donde las condiciones industriales y culturales locales no se prestaban a una imposición de tales prácticas desde la sede central a la empresa filial.

El resultado del análisis contribuye a la comprensión de las relaciones laborales en India y del rol central del Izzat. En India, el rol significativo de los sindicatos, el respeto de los empleados, la importancia de la familia y de la comunidad, la importancia del sistema de antigüedad, y el rol de las nociones de respeto y honor, constituyen factores que, a menudo, las multinacionales no logran comprender al momento de la concepción y de la implantación de sus sistemas de producción y de gestión de recursos humanos.

El estudio contribuye al debate sobre la transferibilidad de políticas y de prácticas estandarizadas de GRH. Las empresas multinacionales deberán jugar un rol proactivo ayudando los empleados de las empresas filiales a ajustar y adaptar los nuevos paradigmas de relaciones industriales en los lugares de trabajo. Las prácticas agresivas de producción y de gestión de recursos humanos en esta fábrica de Toyota no fueron compatibles con las normas y las instituciones culturales de la mano de obra hindú. Una de las principales implicaciones de esta investigación es que los sistemas extranjeros de producción, de organización y de relaciones industriales no pueden ser trasplantados a los contextos del país anfitrión sin el debido reconocimiento de las condiciones culturales claves, especialmente del Izzat en India.

Palabras claves:

- Izzat,

- India,

- producción automotriz,

- conflicto industrial,

- resistencia de los empleados

Article body

Introduction

The Toyota Motor Corporation had a reputation for industrial harmony that was evident even in its US and UK subsidiaries, countries traditionally renowned for industrial unrest in the automobile industry. However, the Indian subsidiary proved to be a rare exception to this trend. From the start of the operations in Bangalore, India in 1999 Toyota experienced ongoing industrial unrest. This gradually escalated culminating in a lock out of employees in 2006. In this paper the ongoing industrial confrontation is mapped and its eventual resolution outlined. Crucial to understanding the long-term industrial conflict is the Indian construct of Izzat. The questions examined in the paper are: Why did Toyota encounter employee and community resistance and militancy in its Indian plant? Why were the company’s human resource management (HRM) and production programs that were acceptable and effective globally, treated with hostility by employees at its Indian subsidiary? In answering these questions the contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it highlights the difficulty of transmitting HRM policies across subsidiaries without sufficient consideration for cross-country differences in institutions, including culture. Such barriers to policy transmission have been highlighted in the institutional international HRM and industrial relations (IR) literature (Uysal, 2009; Brewster, Wood and Brookes, 2008). Second, the article demonstrates how apparently successful HRM programs in an MNE with a record of harmonious IR can be eroded in the face of workforce hostility and resentment, and in the application of management practices that embody underlying assumptions about workforce behaviour independent of any understanding of local culture. Third, the article highlights the importance of Izzat to understanding how, in the Indian context, plant-based workplace disputes can become a source for community protest.

The Concept of Izzat

Izzat is unique to the Indian society and culture. Beyond its literal translation as respect and honour (Allied Chambers Transliterated Hindi English Dictionary, 1993), Izzat has a deeper cultural value in India, and cannot be understood or analyzed from a foreign perspective (Dusenbery, 1990). Izzat is woven not only with the status of an individual in India but also with groups, society, culture, caste, and religion, making it incomprehensive in its pure local sense for outsiders. Gilbert et al. (2004) define Izzat as a learnt, complex set of rules individuals follow in order to protect the family honour as well as his/her position in the community. Therefore, the phenomenon could be argued as ‘discourse of familiarity’ versus ‘outsider oriented discourse’ (Bourdieu, 1977: 18). Though Izzat is a Hindi word, the value of the concept as a matter of pride and prestige remains the same across India. Any attempt to intrude the space of Izzat is treated as a misdemeanour prompting retaliation.

Izzat in India works at three mutually reinforcing levels: individual, familial, and social. The individual Izzat is constructed and shaped by membership in the family and society. Familial and social Izzat are likewise the product of historical pride (stories of the heroes who upheld Izzat) merged with present interactions, outlining the future. In such a complex relationship, Izzat has a ripple effect in a centripetal and centrifugal manner, reflecting the hypersensitive nature of Indians in regard to Izzat. Chaudhary and Sriram (2001) identify ‘dialogical self’ as the construction of ‘self’ based on interpersonal and intrapersonal dialogues in a social context. Izzat in India is evaluated in a deeper realm where a dialogue determines the ‘self’. This internal process of analysis is automatic in the Indian psyches leading to either acceptance or dejection based on the merit of interactions. Izzat in India is deeper than the Western concept and understanding of honour. It is deeply embedded in the cultural psyche of India and is entangled in the caste and class factors. Whilst dignity at work in the Western context is situated within the individualism dimension of national culture (Hofstede, 1980), the same is collective in the Indian context. As a result, we identify that Izzat in the Indian context has a ripple effect and travels across the individual-family-society axis. As a result, disturbances at the workplace are not contained within the walls of the factory but immediately cross the gates, causing social unrest, as is evident in this case. Undermining Izzat causes humiliation, degradation, and insult inflicting injury to positive self-understanding (Honneth, 1992) leading to impairment of ‘moral experiences’ and ‘violation of identity claims acquired in socialisation’ (Honneth, 2007: 70). Izzat of an Indian is both inherited (e.g. born in a particular caste) and acquired (education and social status), which is naturally shared by the family and society; and hence offence to Izzat has an impact on multiple players. Offences targeted at Izzat are highly inflammable, leading to violent retaliation with widespread industrial and community unrest.

Local Obstacles to Global HRM Practices of Multinational Enterprises

There is much literature on standardization versus localization, isomorphism pressures, convergence versus divergence of best practice, and whether Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) adapt to contextual factors to shape their HRM practices (e.g. Pudelko and Harzing, 2007; Rowley et al., 2016). While MNEs aim to introduce standardized HRM practices across subsidiaries (Pudelko and Harzing, 2007), and subsidiaries succumb to the influences (mimetic isomorphism) of the “country of origin effect” (Edwards and Kuruvilla, 2005), in practice, legal and cultural constraints prevent global HRM homogenization (Rowley etal., 2016). Contextual opposition, such as the incompatibility with local culture, is often overridden by mimetic forces such as a production model (Smith and Meiksins, 1995). Institutional factors such as politico-legal (Kostova and Zaheer, 1999) and socio-cultural (Sousa and Bradley, 2006) play a restraining role in the standardization and homogenization program attempts of MNEs across subsidiaries (Festing, Eidems and Royer, 2007). For example, a traditional paternalistic culture that underpins employment regulations in India (Ramaswamy, 1983) results in organizational separateness impeding the transfer of HRM practices to MNE subsidiaries (Dasi et al., 2017). The power and influence of local institutions underpins the calls for localization in HRM program development, as opposed to mimetic isomorphism (Bjorkman et al., 2008; Kostova and Roth, 2002), an argument found relevant to HRM in Asia (Schaaper et al., 2013).

In the context of this study, literature on the Japanization of British manufacturing indicates that researchers were skeptical of the transplantation of Japanese manufacturing practices into the British context due to the contrast in the economic and social structure of the two countries (Ackroyd et al., 1988). Oliver and Wilkinson (1993) argued that the level of worker commitment required in the Japanese production system suited that country’s social structure but had the potential for disruption in the British IR context. Across other countries, Dohse et al. (1985) argued that lean production was a response to the then Japanese institutional framework of innovation, which was implemented by way of work intensification. However, the pressures on employees through work intensification were met with resistance from the European and American workers (Elger and Smith, 1994).

Contextual legitimacy (Kostova and Roth, 2002) helps MNEs in shaping subsidiary organizational culture contributing to product, process and projects (De-Waal and De-Boer, 2017). This implies the localization of HRM programs whereby MNEs behave as local entities (Rosenzweig and Nohria, 1994) and engage within that context. As a consequence, a process of hybridization emerges (Horwitz et al., 2002) and the “structural contingency approach” (Smith and Meiksins, 1995: 252) is argued to better represent the application of HRM programs for emerging economies such as India (Uysal, 2009). However, in our case study, the evidence suggests a process of initial unilateral imposition of a production and voice model from headquarters, independent of local contextual conditions. As practised by many Japanese MNEs (Furusawa 2008), ethnocentric policies are often adopted as a control mechanism for standardization (Vance and Paik, 2006), uniform corporate culture (Rosenzweig and Nohria, 1994), internalization of ownership specific advantages (Cooke, 2006) and globally standard products and services (Morgan and Kristensen, 2006). In the Indian context, the consequence was long-term industrial and community unrest driven by damages to Izzat.

Izzat and Indian Workplace Relations

Izzat embodies the ‘face’ of an individual approved and agreed by society (Goffman, 1972), which helps individuals to maintain honour and dignity in the family and society through a variety of means such as deference to seniors and avoiding public disagreements (Storti, 2007). Challenges to Izzat could exclude individuals from the mainstream of a social ecosystem (Bar-Tal, 1990) resulting in the dehumanization of individuals and reflecting badly on their family and the immediate society. Izzat could be argued as being a key factor in determining the success of HRM practices of MNE subsidiaries in India. In a typical Indian workplace situation, work and working conditions are equally important, as offence to Izzat affects motivation leading to a lack of employee commitment and engagement (Tyler and Bladder, 2003; Bhatnagar, 2007) and counterproductive work behaviours (Goyal, 2012). For instance, many Japanese automobile companies practising lean require skilled workers to do menial jobs, which undermine their Izzat (Singh-Sengupta, 1999). This suggests that there is an association between locally responsive employee engagement strategies and the effective operation of subsidiaries (Farndale, 2013).

In an MNE context, emotional relationships and interpersonal trust are key factors in determining the state of workplace IR (Yahiaoui, 2014). A well- maintained Izzat acknowledges the emotional health of not only individual employees, but entails the discourse of communal trust with the organization. However, where an individual’s Izzat is damaged through culturally insensitive work practices, this may result in opposition from individual workers and their families and the community (Heine et al., 1999). The potential conflict between lean production and cultural makeups such as Izzat may affect MNE workplace relations. The lean discourse demands loyalty characterized by a level of individual commitment fairly detached from familial and social relationships (Miroshnik, 2013). This contradicts the Indian collective work culture extending to family and society (Smith et al., 1999).

Izzat enables Indian employees to develop a positive ‘self’ that contributes to self-actualization, achievement, and growth (Haslam et al., 2000). In a workplace context, since the audience factor (Tedeschi and Felson, 1994) has a strong influence on Izzat, disrespectful supervisor-subordinate interactions in the presence of others may affect the positive ‘self’ (Honneth, 1992). A damaged Izzat may adversely affect the psychic boundary resulting in employee withdrawal and employee disengagement (Schmader et al., 2001) and affecting individual dignity (Jaber, 2000). Prolonged emotional turbulence due to damaged Izzat devalues (Leary et al., 1998) and displaces individuals, forcing individuals to restore social membership (Honneth, 1997) by recapturing Izzat. Therefore, the role and importance of Izzat in the Indian workplace is argued as being the key to understanding the described industrial unrest at the Toyota plant.

Methodology

Our analysis is based on interviews with key respondents and reference to reports and media in the public domain. We are interested in understanding the complex, dynamic and longitudinal issues (Miles and Huberman, 1994) behind the flow of events over eight years of industrial unrest at the plant, as the workers, unions, and the community perceived a challenge to their Izzat. Researching a topic as diverse as community and workplace industrial unrest presupposes the vital significance of interpersonal relationships. Since qualitative research enjoys ‘a preference for naturally occurring data’ (Silverman, 2000: 8), these are more fruitfully uncovered and understood through the medium of methods such as observation and unstructured interviews.

This study is based on thirty-five interviews collected in India, Thailand and Australia from 2008 to 2012, representing a cross section of stakeholders including senior executives from Toyota, journalists, trade union officials, shop floor workers, managers, and former employees. The data collected from the first interview in 2008 with a former employee sought to understand the reason behind the period of prolonged industrial unrest at the plant. The interview identified resistance to lean production as the major reason behind the industrial unrest. From this, further interviews were conducted in order to understand why the unrest extended beyond the plant, and this resulted in interviews extending to stakeholders beyond the workplace. From these interviews certain themes emerged, with ‘cultural disrespect’ and ‘industrial unrest’, according to open coding principles (Strauss and Corbin, 1998), being terms that recurred throughout the interviews.

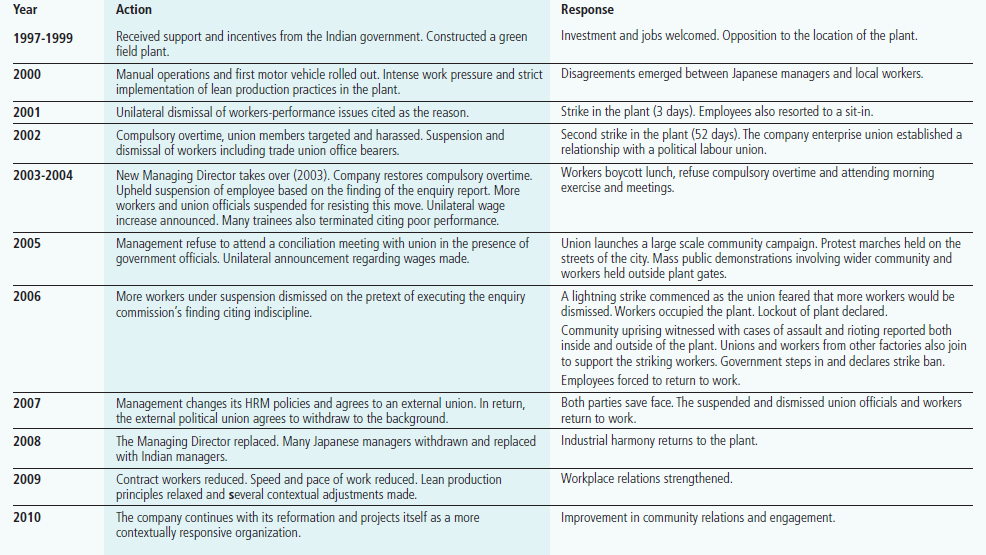

This was followed by secondary data collection by internet using search words such as ‘unrest at Toyota’, with an intention to validate the themes that emerged from the interviews, as well as to gather more information to support further data collection. The news items were downloaded and sorted chronologically so that a running history of the plant could be created from 1999 to 2010. These events are detailed in Table 1.

On the basis of this preliminary data collection and analysis, trips to India generated interviews over several years with a senior executive of the company, nine managers, two management academics from the location, eleven shop floor workers, two external trade union leaders, and two journalists as listed in Table 2. The journalists were included based on secondary data that revealed them as reporting on the automobile industry in India and particularly the industrial unrest at Toyota. The academics were locally-based and one of them had conducted studies on lean practices at Toyota’s local plant. Being locally based, like the journalists, the purpose of their inclusion was to assist in the validation of the findings, especially about the cultural aspects of the industrial dispute.

The semi-structured interviews, which lasted between 30 minutes and two hours, were tape-recorded and transcribed. Additional data were also collected from observations recorded by one researcher who visited the plant. The observations recorded in the field notes were simultaneously analyzed with the primary and secondary data, achieving triangular validation of conceptual ordering and themes, thus meeting the requirements of an inquiry audit (James and Jones, 2014).

The complexity behind the flow of organizational events due to the ongoing process of industrial unrest and the iterative information collection process that identified new informants enabled a longitudinal understanding to emerge in which data collection is best thought of as a cause-consequence process (Miles and Huberman, 1994) that evolves so as to capture the ‘naturally occurring data’ (Silverman, 2008: 8).

Table 1

Key Industrial Relations Events at the Bangalore Toyota Plant

Table 2

Interviewee Profile

From the interviews, public documents and field notes, recurrent themes emerged from the analysis. In particular, the theme of Izzat emerged as one of the main factors contributing to the plant’s ongoing industrial unrest (Glaser, 2001: 177). The task was then to explain why Izzat was a key component of Indian IR.

A Chronology of Industrial Unrest at the Bangalore Plant

Toyota Motors in Bangalore is the company’s only subsidiary in India. During the period of this study, the company was still in its formation stage, with one single product, a passenger car, and had less than a thousand employees. Since this time, it has grown to an annual capacity of 320,000 vehicles, two plants and variety of vehicles. Toyota had a propitious beginning in India, with favourable investment support from Indian governments, including fiscal and regulatory exemptions. However, the first offence to Izzat was immediate when the company flattened a sacred hill for plant construction.

Contrary to the expectation about Japanese technology and high-quality autos, Toyota started with a low degree of automation, leading to community disappointment:

… it is not a new line….it is a scrap line from some other country…..already used line… and they have brought that technology here ;

union leader

… initially we started with manual operation, there was no automation, all operations were manual; we emphasize to instil the process ;

interview with Manager 7

…we expected to work in high technology, and even boasted about it in our family and to neighbours. But, here… it is all manual… very tough, backbreaking. It is very upsetting.

shop-floor worker

Izzat was further challenged when the first vehicle rolled out: “It was criticized for not being a new offering but a redesigned for India car which had already been phased out in other parts of the world” (local journalist).

As production expanded and lean processes were introduced into the plant, employees who were inexperienced as regards to the pace, discipline, long hours and intensity of work were affected as they perceived a disregard to the individual, family, and social Izzat. This is contrary to the Indian work practice relating to the inclusivity of familial and social obligations (Sinha, 2004): “…it is very difficult to work in such conditions, no care, no concern… only job, job, and job” (shop-floor worker).

As the line was manual and the demand for the first car surged, there was initial enthusiasm among the Japanese managers to lift production through work intensification. This led to compulsory overtime for shop-floor workers, filling the four-hour gap between the two shifts (Mikkilineni, 2006): “… strict production targets forced the management to enforce compulsory overtime” (journalist).

As the workers were inexperienced in lean production practices, the enthusiastic Japanese managers tried to forcefully and strictly implement lean practices such as just-in time (JIT), Kanban, and Jumbiki (synchronized supply) (The Hindu, 2005). These caused considerable ergonomic issues among the workers, with many reporting health problems. From the early days of operation, stories began to emerge from the plant concerning offences to the local customs and practices through the production and management systems that were being imposed:

“… so many arrogant Japanese people came to India…they did not want to listen to anybody”.

union leader

Conflicts were soon reported around cultural issues such as: “… there was an incident of a Japanese manager abusing a worker by seizing his cap, throwing it to the floor, and stamping on it, whilst shouting ‘you Indians’”.

local journalist

This was later confirmed in another interview: “…yes, that thing happened…..they don’t know our values”.

shop-floor employee

Given the general importance of headwear in India as a symbol of status and Izzat, abuse of it affected not only individual Izzat, but that of the family and society. Moreover, aggressive behaviour that is of a personal nature is also offensive to the Izzat of Indian workers.

It was also reported that: “The Japanese did not appreciate Indian workers eating with hands”.

local journalist

The harsh treatment of workers in the plant was a serious issue for the trade union: “The burning issue is the treatment of workers, that’s the problem here”.

trade union leader

Imposed requirements on the workforce to mop and clean the workplace were perceived as being demeaning: “Men do not like to clean anything, they think cleaning is left to women […] they don’t keep everything in order, but that is a mental block, a cultural thing” (Manager 1).

According to the traditional Indian culture, the practice of such menial jobs being done by skilled workers is contrary to their Izzat.

Job insecurity was yet another challenge for young workers, as they were hired as contractual workers. As a matter of individual, familial and social Izzat, these workers, as the male members of the family, had no financial security. In addition, management followed a unilateral approach in work-related decision making without prior consultation.

The series of disappointments that were linked to damaged Izzat suddenly flared up into an open confrontation in the form of a three-day strike in 2001 when workers were sacked on the grounds of unsatisfactory performance. A protest by employees over the dismissals escalated via employees boycotting the plant lunchrooms: “it was a peaceful protest without affecting the work. The workers expressed their disappointment by boycotting the lunch, only […] but were victimized” (union leader).

There was a misunderstanding of the Indian way of protest (Mathew and Jones, 2012). The over-reaction to a mild protest resulted in further unrest at the plant. Though this first industrial confrontation was settled, with the management agreeing to conduct a review of the dismissals, a series of offensive actions by the management contributed to an undermining of Izzat. This was especially the case with collective representation. The workers, when attempting to register TMA (Team Member Association) as a trade union, were shocked to learn of the pre-existence of a management sponsored union since 1999 that had no role in collective bargaining and only dealt with workplace safety. In addition, the company had exemptions from legal dispute resolution procedures by being classified as a public utility, and this provided exemption from the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947. This process is in keeping with Josserand and Kaine’s (2016) concept of vicarious voice; a substitute IR system where employee representation is assigned to management sponsored organizations. It was also alleged that the performance management system falsely targeted workers to be punished or sacked: “It is just a tool to punish us. We protest and we are targets in the firing line, either sacked or our training period extended” (shop-floor worker).

The second wave of unrest lasted 52 days and erupted in 2002 with the union declaring a strike. The claims of the union included reinstatement of dismissed workers, non-interference by the management in union activities, recognition of an external trade union, the removal of compulsory overtime, and a reduction in the workload. The industrial unrest moved outside the plant, with external unions supporting the workers. The management labelled the strike as illegal and accused the workers of poor performance. The state government imposed a ban on strike actions through the special legislation accorded to Toyota and this was followed by the arrest of workers. The strike ended, the workforce returned to work and Toyota imposed a global performance appraisal system as a means to discipline workers. The global performance appraisal system follows contemporary HRM practices that are more individualistic, which sits uneasily with the Indian IR system which is collectivist and welfare oriented. This action further eroded Izzat through reducing employee self-worth and ‘weakening the class consciousness of the ordinary workers’ (Das and George, 2006). The company also remained entrenched in its stand of non-recognition of external trade unions within the plant.

The new Managing Director who took over in 2003 insisted on actively contributing to the company’s global aspirations by extending lean production processes. By now, the employee opinion about lean was that: “It is a Nazi system, no respect or care for human beings and their lives, no respect…..what is this?” (union leader).

The workers again resorted to protest by refusing to accept compulsory overtime, not performing compulsory morning exercises and boycotting lunch. Protests followed and management could still not comprehend this unique Indian style of peaceful protest, as it again resorted to retaliatory measures such as suspension and dismissals. This eventually culminated in the third wave of unrest, again in the form of a strike at the end of 2003 that continued until mid-2004. Throughout this period, several union leaders and workers were suspended. The unrest was ongoing and continued in passive and active forms throughout 2004. In early 2005, the union filed a demand for conciliation with the District Labour Court over a charter of demands that had been submitted to the company management. However, the management refused to attend the conciliation meeting, which the union interpreted as arrogance and as an insult to authorised worker representatives: “It is not only we union leaders, but our workers’ community and our society also is insulted. How dare they disrespect our system?” (union leader).

A protest involving workers, external unions, family members of the workers, and local social organizations was staged drawing national publicity. The workers notified the management about its plan to strike unless all the issues were resolved immediately. This time, instead of the company agreeing to negotiate with the workers, they resorted to threatening to move the plant elsewhere, away from the locality, to another State: “You see the Izzat of the local government was at stake. If this company moved out, it would affect other foreign companies to come here and set up their operations. So the government had no choice but to support the company” (local journalist).

The workers were undeterred by the relocation threat of the company, and declared yet another strike in 2005. A visiting management guru from Japan stated that: “Indians are not good at manufacturing. Even if they do what we tell them to do, they always need to understand why they are doing it that way. They are more inquisitive than the Chinese” (Sangameshwaran, 2005).

The above statement, aligned with the aggressive imposition of lean practices and institutionally irresponsible actions, was viewed as offensive to the Izzat of the workers. Moreover, the workers were physically and mentally drained from the intensity of lean production practices, which they viewed as being inhuman: “We are sick, our health is down, we can’t move our hands, our back is hurt…. Moreover, we are humiliated every day in one way or the other” (shop-floor worker).

The intervention of the state government using the yet undisclosed ‘public utility company’ legislation forced the workers to return to work, though with a loss of face and a damaged Izzat. In an attempt to restore the lost Izzat, the workers, with the support of external unions, declared further industrial action in 2006. A senior union official commented: “The issue is not of wages but respect for workers and job security. The inquiry had to be completed in three months according to the Industrial Disputes Act but it had dragged on for such a long time”.

The workers and the union were also critical of the company on several unresolved issues such as “disrespectful and ‘illegal practice’ of making skilled workers mop the floors, compulsory overtime, harsh working conditions under the pretext of lean production practices and so on” (union official).

The workers were in a militant mood and soon occupied the plant. One of the workers jumped up on the roof and threatened to blow up the LPG plant. When asked about this violent action, the worker replied: “It was a do or die battle as we were losing everything. We completely lost our prestige, nowhere to go, no support from government. […] our family, everything was affected.”

A journalist commented: “It was a war-like situation, with violent workers inside, armed supporters outside, families of the workers some shouting, some screaming, total chaos. A large police contingent also arrived and the supplies to the plant were stopped with employees holed in.”

The management declared an indefinite lockout, citing safety concerns due to the violent and disruptive acts by the workers and their community supporters. In response, the Labour Commissioner convened a reconciliation meeting at his office but the management was too scared to attend, as the violence spread to the streets. A journalist present at the venue described the situation outside the Labour Commissioner’s office as ‘unnerving’.

The media gave prominence to the views of a leading HR consultant who blamed the Japanese MNEs in India for failing to handle sensitive issues: “The management goofed up on both the PR as well as the HR front […] Japanese managements have hardly made any effort to learn how to deal with India’s highly politicized unions” (Majumdar, 2006: 8).

The industrial relations situation at the plant was snowballing into wider community protests. There were demonstrations against not only Toyota, but other Japanese subsidiaries, and even other multinational subsidiaries operating in India (Business Line, 2006). The entire issue of industrial unrest that started with the dismissal of three individuals thus spread across to reach the local, national and international arena. Even the Japanese ambassador to India appealed to Japanese managers to re-work their perception of India, and openly called them to bring in the best technology and to form effective partnerships within India, making the country a hub of their global production strategies (Surendran, 2010).

Resolution

The first step towards resolution and settlement was the recall of several managers from India to Japan. The new Managing Director (MD) initiated several strategic actions, code named ‘operation jumpstart’ to rebuild the company’s image in India. He also took over several key portfolios including HRM. The new MD stated: “The cultures may be different, but the key to success of this joint venture is based on mutual respect. We are humans after all, and what shores up this mutual admiration is very deep and frequent” (Mitra, 2010).

A manager admitted: “Yes, in the past there has been a misunderstanding, now we are trying to correct this”.

By 2006, Toyota had introduced several programs that helped workers, their families and community feel that Izzat was restored. Manager 3 identified the key initiatives as:

Almost all the Japanese executives were replaced with Indian managers

The trade union is now recognized by the company and workers are free to form unions

A participative work environment is created

There are now restrictions on work intensification

Several other concessions in line with the Indian context are accepted.

The ethnocentric management policy of Toyota was diluted as Indian managers were promoted. As a result, Manager 8, who had left the company, returned to his job. He stated:

Previously we did not have a voice, and our opinions were voiced down by the Japanese block. As a result, many poor decisions were made in terms of models, marketing strategies, people relations and so on…..now they have realized….we have a say now. These replacements played a key role in re-establishing the strained relationship within the plant.

Manager 5

The company accepted the trade union by allocating an office within the plant and allowing networking activities, thus recognizing the workforce attachment to a local form of union organization.

In addition, sacked workers were reinstated: “Now the union is recognized and workers are respected….we have real negotiations, and trust is there. Now the management wants to discuss all issues, on the table….before, we were just told what to do, and management only wanted to hire and fire” (shop-floor worker).

Positive workplace measures such as reduced work intensification, work-process consultations, encouragement of workers’ feedback, ending the compulsory cleaning of work areas, reductions in the number of contract workers, regularizing the employment of existing contract workers, and relinquishing the ‘public utility service’ status that effectively prohibited strike action, were implemented. This resulted in: “Less pressure on team members and more respect” (shop-floor worker).

Moreover, the company attempted to reach out to the family of workers by constructing a housing village, and undertaking several initiatives to reach out to the wider community. As Manager 4 proudly stated: “Do you know, unlike the corporate practice, we have a brand ambassador (a popular Bollywood actor) in India? This is a mark of respect to Indian culture.”

Despite these developments, Toyota India has not achieved complete industrial harmony as evidenced by another dispute in 2014. This substantiates our claim about the uniqueness of Izzat in India. If it was confined to a minority of employees, the company could have dealt with it, but the flow-on effects and community antipathy towards the company continue.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that standardization and ‘one best practice’ approaches towards HRM and production systems grounded in strong discourses such as lean production may risk industrial unrest if they are implemented without regard to local customs and community expectations. Local institutional factors, such as culture, can act as a coercive isomorphic force restraining the mimetic and normative isomorphism of HRM practices of MNE subsidiaries. In short, the subsidiary is caught up in an identity crisis between the management and employees/community due to contextual factors that prevent the seamless transfer and implementation of production and HRM systems. An inclusive and culturally sensitive approach could help MNEs better balance modern management practices and local conditions to create a holistic organizational discourse (Kostova and Zaheer, 1999). The case study demonstrates the impeding role of culture against unilateral attempts to transfer lean production practices into the Indian context. Local communities and local unions resisted attempts to unilaterally impose a Japanese production system and plant based unions. The offence to Izzat was triggered as Toyota hastily and unilaterally attempted to replace the political model of IR with a management driven organization model (Cameron, 1983). Trade unions in India are affiliated to political parties and, as a result, unions enjoy the patronage and protection of political parties in order to garner their political support (Ramaswamy, 1983; Chaudhuri, 1996). The Industrial Disputes Acts of 1947 demonstrates this patronage as, under it, the government has the right to interfere in, and adjudicate on, any labour dispute so as to promote industrial peace (Saini and Budhwar, 2004). The Indian workforce has enjoyed a welfare-oriented employment system since independence. The collectivist workplace system and the political importance of trade unions have supported employee rights and have been embedded in the industrial relations system ever since the formation of the first independent government in India (Roychowdhury, 2005).

Past attempts in India to transition from a collectivist welfare-oriented approach towards an efficiency-oriented approach in workplace relations (Budhwar and Khatri, 2001) have always been hampered by the influence of religion, caste, and politics (Amba-Rao, 1994). Industrial relations, post 1991 economic liberalization in India ,has seen ongoing tensions as the State has struggled to balance between attracting FDI and supporting labour conditions. Political patronage often hampered reformation of the IR laws, and hence governments created a flexible work environment through the light enforcement of labour laws and selective intervention at the workplace in support of capital (Shyam Sundar, 2015). At the height of industrial unrest, Toyota threatened to move the plant out of Kamataka and relocate to another part of India. Mosley and Uno (2006) claim that MNEs regularly use relocation threats as an attempt to erode State based IR laws and avoid trade unions.

Roychowdhury’s (2008) analysis of industrial disputes in Bangalore identifies a macro (social) undercurrent beneath the micro (firm specific) disputes. As the society at large is affected by waves of globalization, with subsequent pressures on employee conditions, the State’s approach to industrial dispute resolution in India has been diminished to that of a mere onlooker, leaving the parties to engage in prolonged disputation as globalization confronts local culture (Roychowdhury, 2008).

The research suggests that Izzat, had a deep impact on workplace IR at the Indian subsidiary. The damage incurred on Izzat, at the individual, familial and social levels was due to two factors: the company following a standardized production and HRM approach and ignoring local institutions, especially culture; and the company failing to understand the dynamics of Izzat in terms of its reachability beyond individuals (workers), and often misreading or over-reading employees’ actions and reactions. These led to an overall breakdown in the IR climate in the subsidiary which caused a ripple effect across the country and overseas. Eventually, the company worked through the same local cultural conditions to restore its credibility through a series of consultative and trust building measures in order to restore Izzat. Toyota’s ethnocentric, authoritarian and unilateral approach in the transplanting of lean production resulted in a process of employee and then wider community resistance and protest. It took almost a decade after the plant’s establishment for Toyota to realize the necessity of contextual adaptation, as openly admitted by the firm. The Japanese production system faced several cultural obstacles in India, and the development of HRM and IR systems in India require an understanding of the local socio-cultural institutional dynamics if they are to be effective (Budhwar, 2003; Mathew and Jones, 2012, 2013; James and Jones, 2014). Saini’s (2005: 73-74) research on the violent unrest at Honda Scooters and Motorcycles India had a few striking parallels related to Izzat in that the unrest followed perceived insults to the workforce.

The focus of this paper is on an industrial relations conflict that developed because of the implementation of lean production in a host country environment without taking into consideration the underlying cultural and institutional conditions. In the context of India, Izzat is an important condition that extends beyond the workplace to the community, and an industrial relations conflict can become a source of community unrest due to the force of Izzat.

There are several instances in the Bangalore plant history where Izzat generated reactions beyond the workplace:

When the team leaders were appointed on the basis of performance, it contradicted the traditional seniority and age-based career structure, as a junior person became a leader. This became an Izzat issue for those affected, which immediately resulted in community agitation. Strong family orientation and a respect for elders support the Izzat of the Indian society (Kakkar et al., 2006). Moreover, when the new managers belonged to another caste, especially lower castes, this challenged the Izzat of the upper caste community.

When the workers followed the Gandhian mode of peaceful protest (Satyagraha) by boycotting lunch, the management forced the workers out of the factory and declared the action taken by the workers amounted to strike. As Mahatma Gandhi is the father of the nation, and his Satyagraha principles are deeply embedded in the psyche, the workers and later the wider society perceived this heavy action as a questioning of their national Izzat. As a consequence, external unions affiliated to political parties found this as an opportunity to raise their voice against the company.

The power of unions in India is built upon their contribution to the Indian freedom movement. Ramaswamy (1983) points out how one union leader could create chaos in a well-managed automobile company in a neighbouring region. Following the lean paradigm of the enterprise-level union, external unions were neither recognized nor allowed to operate in the IR affairs of the plant, and, in turn, this affected the Izzat of the unions. As is evident from a union leader’s statement: “It is not only we union leaders, but the workers’ community and society is affected”, the Izzat was not confined to workers, but the wider community, when affected.

The workers’ experience was contradictory to their expectations of a relaxed and peaceful work environment in foreign companies. However, as is evident from the data, when the parents found their children returning home tired and sick due to intense work conditions following the rigid lean production system, their Izzat was affected. Moreover, the lack of job security and the suspensions and dismissals on the basis of performance affected the Izzat of individuals, their families and societies, as they lost face in society.

Conclusions

This article outlines a case study that demonstrates the failure of a successful MNE auto maker in acknowledging and appreciating local cultural factors when transplanting lean production practices into India. Toyota preferred unilateral decision making and process implementation, thereby affecting the overall organizational climate that is strongly underpinned by the social and psychological needs of the employees (Sharma, 1988). Though Japan and India are Asian countries, and lean is of Japanese origin, it is argued that lean production is Western-oriented and is a form of modified Taylorism, or inverted Scientific Management (Parker and Slaughter, 1994). Lean production comprised modified Western managerial practices and, in this case, combined with a Japanese work culture. The Indian work ethic contradicts the Japanese production system, which attaches more importance to work over family and community. For Indian workers, family and community are more important than work (Jain, 1987). This difference has led to considerable misunderstandings and conflict at Toyota and Honda Motors in India.

One of the key implications of our study is the significance of Izzat in the Indian IR system, which provides a deeper insight into the studies on global transferability of standardized HRM policies and practices. It is suggested that organizational ‘best practice’ is an adaptive process involving the fusion of local and global factors contributing to industrial harmony and firm efficiency. As MNEs are argued to be ‘role-players’ in influencing host-country institutions, they should play a proactive role in sympathetically facilitating the ability of subsidiary employees to adjust to and to accommodate new paradigms in workplace industrial relations. The Toyota plant was established in the initial days of the country’s economic liberalization, and aggressive modern production and HRM practices were not compatible with the norms and cultural institutions of the Indian workforce.One of the key implications of this research is that foreign production, organizational and industrial relations systems and practices cannot be transplanted into host country environments without due recognition of key cultural conditions such as Izzat.

Our study extends the criticism of lean production that is applied globally without adjustment to local conditions (Stewart et al., 2016). In this way, we advance the social exchange theory of Blau (1964) and critical theory of Honneth (1992) that Izzat, as a fundamental cultural condition for the Indian workforce, underpins positive social exchange and stops dehumanization tendencies. The successful transfer of HRM systems must consider contextual adaptations. This is more so the case with countries such as India that have a strong and ingrained cultural heritage. The intertwining of local institutions makes the transplant process more sensitive and complicated as the reflection of any action causes ripple effects across the workplace, the organization and the community.

One important limitation of this paper is the case study approach that we have adopted and the context of the study. The case study is not representative and represents the analysis of local conditions that may not be replicated elsewhere.

The study is also limited in terms of the limited number of respondents. In terms of further research, Izzat as a key cultural concept is presently under researched, particularly in terms of its significance in understanding workplace relations in India.

Appendices

References

- Ackroyd, Stephen, Gibson Burrell, Michael Hughes and Alan Whitaker (1988) “The Japanization of British Industry”? Industrial Relations Journal, 19 (1), 11-23.

- Allied Chambers Transliterated Hindi English Dictionary. (1993) New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

- Amba-Rao, Sita C. (1994) “US HRM Principles: Cross-Country Comparisons and Two Case Applications in India.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5 (3), 755-778.

- Bar-Tal, Daniel (1990) “Causes and Consequences of Delegitimization: Models of Conflict and Ethnocentrism.” Journal of Social Issues, 46 (1), 65-81.

- Bhatnagar, Jyotsna (2007) “Predictors of Organizational Commitment in India: Strategic HR Roles, Organizational Learning Capability and Psychological Empowerment.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18 (10), 1782-1811.

- Bjorkman, Ingmar, Pawan S. Budhwar, Adam Smale and Jennie Surnelius (2008) “Human Resource Management in Foreign-owned Subsidiaries: China versus India.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19 (5), 964-978.

- Blau, Peter Michael (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brewster, Chris, Geoffrey Wood and Michael Brookes (2008) “Similarity, Isomorphism or Duality?: Recent Survey Evidence on the Human Resource Management Policies of Multinational Corporations.” British Journal of Management, 19 (4), 320-342.

- Budhwar, Pawan S., Ingmar Bjorkman and Virendra Singh (2009) “Emerging HRM Systems of Foreign Firms Operating in India.” In Pawan S. Budhwar and Jyotsna Bhatnagar (eds.), The Changing Face of People Management in India, New York: Routledge, p. 115-134.

- Budhwar, Pawan S. (2003) “Employment Relations in India.” Employee Relations, 25 (2), 132-148.

- Budhwar, Pawan S. and Naresh Khatri (2001) “HRM in Context: Applicability of HRM Models in India”, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 1 (3), 333-356.

- Business Line (2006) Commissioner Sends Report to State Govt. on Toyota Stir. Retrieved from https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/todays-paper/tp-corporate/Commissioner-sendsreport-to-State-Govt-on-Toyota-stir/article20195642.ece (January 12th, 2016).

- Cameron, Samuel (1983) “An International Comparison of the Volatility of Strike Behavior.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 38 (4), 767-784.

- Chaudhary, Nandita and Sujata Sriram (2001) “Dialogues of the Self.” Culture and Psychology, 7 (3), 379-392.

- Chaudhuri, Dutta M. (1996) “Labour Markets as Social Institutions in India”, Working Paper Series, 10 (March), 1-31.

- Das, Krishnadas L. and Sobin George (2006) “Labour Practices and Working Conditions in TNCs: The Case of Toyota Kirloskar in India.” In Dae-oup Chang (ed.), Labour in Globalising Asian Corporations: A Portrait of Struggle, Hong Kong: Asia Monitor Resource Centre, p. 273-302.

- Dasi, Angel, Torben Pedersen, Paul N. Gooderham, Frank Elter and Jarle Hildrum (2017) “The Effect of Organizational Separation on Individuals’ Knowledge Sharing in MNCs.” Journal of World Business, 52 (3), 431-446.

- De Waal, Andre A. and Freke A. De Boer (2017) “Project Management Control within a Multicultural Setting.” Journal of Strategy and Management, 10 (2), 148-167.

- Dohse, Knuth, Ulrich Jurgens and Thomas Malsch (1985) “From Fordism to Toyotism? The Social Organization of the Labor Process in the Japanese Automobile Industry”, Politics and Society, 14 (2), 115-146.

- Dusenbery, Verne A. (1990) “On the Moral Sensitivities of Sikhs in North America.” In Owen M. Lynch (ed.), Divine Passions: The Social Construction of Emotion in India, Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 239-261.

- Elger, Tony and Chris Smith (1994) “Global Japanization? Convergence and Competition in the Organization of the Labor Process.” In Tony Elger and Chris Smith (eds.) Global Japanization? The Transnational Transformation of the Labor Process, London: Routledge, p. 31-59.

- Farndale, Elaine (2013) “A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Supervisor Support in Performance Appraisal and Employee Engagement.” Academy of Management Proceedings, 1 (1), aomafr-2012.

- Furusawa, Masayuki (2008) The Theory of Global Human Resource Management. Tokyo: Hakutou Shobou.

- Gilbert, Paul, Jean Gilbert and Jaswinder Sanghera (2004) “A Focus Group Exploration of the Impact of Izzat, Shame, Subordination and Entrapment on Mental Health and Service Use in South Asian Women Living in Derby.” Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 7 (2), 109-130.

- Glaser, Barney G. (2001) The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Goffman, Erving (1972) Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. London: Penguin Press.

- Haslam, Alexander S., Clare Powell and John Turner (2000) “Social Identity, Self-Categorization, and Work Motivation: Rethinking the Contribution of the Group to Positive and Sustainable Organisational Outcomes.” Applied Psychology, 49 (3), 319-339.

- Heine, Steven J., Darrin R. Lehman, Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama (1999) “Is There a Universal Need for Positive Self-Regard?” Psychological Review, 106 (4), 766-794.

- Hofstede, Geert (1980) Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- Honneth, Axel (2007) Disrespect: The Normative Foundations of Critical Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Honneth, Axel (1997) “Recognition and Moral Obligation.” Social Research, 64 (1), 16-35.

- Honneth, Axel (1992) “Integrity and Disrespect: Principles of a Conception of Morality based on the Theory of Recognition.” Political Theory, 20 (2), 187-201.

- Horwitz, Frank M., Ken Kamoche and Irene K H Chew (2002) “Looking East: Diffusing High Performance Work Practices in the Southern Afro-Asian Context.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13 (7), 1019-1041.

- Jaber, Dunja (2000) “Human Dignity and the Dignity of Creatures.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 13 (1), 29-42.

- Jain, Hem C. (1987) “The Japanese System of Human Resource Management”, Asian Survey, 27 (9), 1023-1035.

- James, Reynold and Robert Jones (2014) “Transferring the Toyota Lean Cultural Paradigm into India: Implications for Human Resource Management.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25 (15), 2174-2191.

- Josserand, Emmanuel and Sarah Kaine (2016) “Labour Standards in Global Value Chains: Disentangling Workers’ Voice, Vicarious Voice, Power Relations, and Regulation.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 71 (4), 741-767.

- Kakar, Sudhir, Shveta Kakar, Mafred F. R., Kets Vries and Pierre Vrignaud (2006) “Leadership in Indian Organizations from a Comparative Perspective.” In Herbert J. Davis, Samir R. Chatterjee and Mark Huer (eds) Management in India: Trends and Transitions, New Delhi and Thousand Oaks, CA: Response Books, p. 105-119.

- Kostova, Tatiana and Kendall Roth (2002) “Adoption of an Organizational Practice by Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations.” Academy of Management Journal, 45 (1), 215-233.

- Kostova, Tatiana (1999) “Transnational Transfer of Strategic Organizational Practices: A Contextual Perspective.” Academy of Management Review, 24 (2), 308-324.

- Kostova, Tatiana and Srilata Zaheer (1999) “Organizational Legitimacy under Conditions of Complexity: The Case of the Multinational Enterprise.” Academy of Management Review 24 (1), 64-81.

- Leary, Mark R., Carrie Springer, Laura Negel, Emily Ansell and Kelly Evans (1998) “The Causes, Phenomenology, and Consequences of Hurt Feelings.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (5), 1225-1237.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S. (1995) “Emerging Criteria for Quality in Qualitative and Interpretive Research.” Qualitative Inquiry, 1 (3), 275-289.

- Majumdar, Supratim (2006) Labour Unrest at Toyota: The Decision Dilemma. Kolkotta, India: IBS Research Centre.

- Mathew, Saji K. and Robert Jones (2013) “Toyotism and Brahminism: Employee Relations Difficulties in Establishing Lean Manufacturing in India.” Employee Relations, 35 (2), 200-221.

- Mathew, Saji K. and Robert Jones (2012) “Satyagraha and Employee Relations: Lessons from a Multinational Automobile Transplant in India.” Employee Relations, 34 (5), 501-517.

- Mikkilineni, Pushpanjali (2006) IR Problems at Toyota Kirloskar Motors Private Limited, ICFAI Centre for Management Research: Kolkotta, India, 1-15.

- Miles, Matthew B. and Michael A. Huberman (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- Miroshnik, Victoria (2013) Organizational Culture and Commitment: Transmission in Multinationals. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mitra, Moinak (2010) Toyota Way Leaves a Window Open for Improvement: Hiroshi Nakagawa. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/toyota-way-leaves-a-window-open-for-improvement-hiroshi-nakagawa/articleshow/6482076.cms?prtpage=1 (September 6th, 2016).

- Mosley, Layna and Saika Uno (2006) Racing to the Bottom or Climbing to the Top? Economic Globalization and Collective Labour Rights. Retrieved from http://www.unc.edu/~lmosley/mosleyunojuly2006.pdf, May 25, 2018.

- Oliver, Nick and Barry Wilkinson (1993) The Japanization of British Industry. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Parker, Mike and Jane Slaughter (1994) “Lean Production is Mean Production.” Canadian Dimension, 28 (1), 21-22.

- Pudelko, Markus and Anne-Wil Harzing (2007) “Country of Origin, Localization, or Dominance Effect?: An Empirical Investigation of HRM Practices in Foreign Subsidiaries.” Human Resource Management, 46 (4), 535-559.

- Ramaswamy, E. A. (1983) “The Indian Management Dilemma: Economic vs Political Unions.” Asian Survey, 23 (8), 976-990.

- Rowley, Chris, Johngseok Bae, Sven Horak and Sabine Bacouel-Jentjens (2016) “Distinctiveness of Human Resource Management in the Asia Pacific Region: Typologies and Levels.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28 (10), 1393-1408.

- Roychowdhury, Supriya (2008) “Class in Industrial Disputes: Case Studies from Bangalore.” Economic and Political Weekly, 43 (22), 28-36.

- Roychowdhury, Supriya (2005) “Labour and Economic Reforms: Disjointed Critiques.” In Mooij, J. E. (ed.) The Politics of Economic Reforms in India. New Delhi and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, p. 264-290.

- Saini, Debi S. (2005) “Honda Motor Cycles and Scooters India (HMSI).” Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 9 (4), 71-81.

- Saini, Debi S. and Pawan S. Budhwar (2004) “HRM in India.” In Pawan S. Budhwar (ed.), Managing Human Resources in Asia Pacific, London: Routledge, 113-140.

- Sangameshwaran, Prasad (2005) Indians Are Not Good at Manufacturing. Retrieved from http://www.rediff.com/money/2005/dec/20inter.htm (April 20th, 2012).

- Schaaper, Johannes, Bruno Amann, Jacques Jaussaud, Hiroyuki Nakamura and Shuji Mizoguchi (2013) “Human Resource Management in Asian Subsidiaries: Comparison of French and Japanese MNCs.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24 (7), 1454-1470.

- Schmader, Toni, Brenda Major and Richard H. Gramzow (2001) “Coping with Ethnic Stereotypes in the Academic Domain: Perceived Injustice and Psychological Disengagement.” Journal of Social Issues, 57 (1), 93-111.

- Sharma, Baldev R. (1988) “Not by Bread Alone: A Study of Organisational Climate and Employer-Employee Relations in India: New Delhi, Shri Ram Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 43 (1), 208-209.

- Shyam Sundar, K. R. (2015) “Sub-national Governance of Labor Market and IRS: Is this a Panacea or a Problematic?” Indian Journal of Labor Economics, 58 (1), 67-85.

- Sinha, Jai B. P. (2004) Multinationals in India: Managing the Interface of Cultures. New York: Sage Publications.

- Silverman, David (2000) Doing Qualitative Research, London: Sage.

- Smith, Chris and Peter Meiksins (1995) “System, Society and Dominance Effects in Cross-National Organisational Analysis.” Work, Employment and Society, 9 (2), 241-267.

- Smith, Eliot R., Julie Murphy and Susan Coats (1999) “Attachment to Groups: Theory and Measurement.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 (1), 94-110.

- Stewart, Paul, Adam Mrozowicki, Andy Danford and Ken Murphy (2016) “Lean as Ideology and Practice: A Comparative Study of the Impact of Lean Production on Working Life in Automotive Manufacturing in the United Kingdom and Poland.” Competition and Change, 1 (1), 1-19.

- Storti, Craig (2007) Speaking of India: Bridging the Communication Gap when Working with Indians. Boston, MA: Intercultural Press.

- Strauss, Anselm and Juliet Corbin (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tedeschi, James T. and Richard B. Felson (1994) Violence, Aggression and Coercive Actions. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- The Hindu (2005) «Toyota Kirloskar Likely to set up Second Unit in Bangalore», from https://www.thehindu.com/2005/09/28/stories/2005092804280500.htm (retrieved 17th October 2016).

- Tyler, Tom R. and Steven L. Blader (2003) “The Group Engagement Model: Procedural Justice, Social Identity, and Cooperative Behavior.” Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7 (4), 349-360.

- Uysal, Gurhan (2009) “Human Resource Management in US, Europe and Asia: Differences and Characteristics.” Journal of American Academy of Business, 14 (1), 112-117.

- Womack, James P., Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, New York: Macmillan.

- www.rediff.com (2009) “Karnataka CM Urges Toyota to Expand Indian Operations” (retrieved 17th December 2009).

- Yahiaoui, Dorra (2014) “Hybridization: Striking a Balance between Adoption and Adaptation of Human Resource Management Practices in French Multinational Corporations and their Tunisian Subsidiaries.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26 (13), 1665-1693.

- Yin, Robert (1994) Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

List of tables

Table 1

Key Industrial Relations Events at the Bangalore Toyota Plant

Table 2

Interviewee Profile

10.7202/1038530ar

10.7202/1038530ar