Abstracts

Abstract

In New Zealand in the 1990s, labour market decentralization and new employment legislation precipitated a sharp decline in unionism and collective bargaining coverage; trends that continued well into the 2000s even after the introduction of the more supportive Employment Relations Act 2000 (ERA). The ERA prescribed new bargaining rules, which included a good faith obligation, increased union rights and promoted collective bargaining as the key to building productive employment relationships (Anderson, 2004; May and Walsh, 2002). In this respect the ERA provided scope for increased collective bargaining and union renewal (Harbridge and Thickett, 2003; May, 2003a and 2003b; May and Walsh, 2002). Despite these predictions and the ERA's overall intent, the decline in collective bargaining coverage begun in the 1990s has continued unabated in the private sector. It has naturally been questioned why the ERA has not reversed, or at least halted, this downward trend. So far research has focused on the impact of the legislation itself and much less on employer behaviour and perceptions, or on their contribution to these trends. This article addresses the paucity of employer focused research in New Zealand. The research explores views of employers on the benefi ts of collective bargaining, how decisions to engage or not engage in collective bargaining are made and the factors instrumental to them. It is demonstrated that the preferred method of setting pay and conditions continues to be individual bargaining. This is especially so for organizations with less than 50 employees, by far the largest majority of fi rms in New Zealand. Frequently, these smaller organizations see no perceived benefits from collective bargaining. Overall, these fi ndings suggest that despite a decade of supportive legislation there are few signs that the 20 year decline in collective bargaining coverage in New Zealand will be reversed.

Keywords:

- employers,

- unions,

- collective bargaining,

- attitudes,

- Unitarist

Résumé

Durant les années 1990 en Nouvelle-Zélande, la décentralisation sur le marché du travail et la nouvelle législation en matière d'emploi ont mené à un déclin abrupt de la syndicalisation et de la population en emploi couverte par la négociation collective. Ces tendances se sont poursuivies tard durant les années 2000, même après l'introduction d'une législation plus favorable à la négociation collective, l'Employment Relations Act 2000 (ERA) de 2000. L'ERA prévoyait en eff et de nouvelles règles en matière de négociation collective qui incluaient une obligation de négocier de bonne foi, un accroissement des droits des syndicats et encourageait la négociation collective en tant qu'élément central pour le développement de relations d'emplois productives (Anderson, 2004; May et Walsh, 2002). À cet égard, l'ERA allait permettre une plus grande place à la négociation collective et encourager le renouveau syndical (Harbridge et Thickett, 2003; May, 2003a, 2003b; May et Walsh, 2002). En dépit de ces prédictions et de l'intention générale de l'ERA, le déclin de la couverture de la négociation collective débuté durant les années 1990 s'est poursuivi de plus belle dans le secteur privé. On a cherché à savoir pourquoi l'ERA n'a pas permis de renverser, sinon mettre un frein à cette tendance à la baisse. Jusqu'à présent la recherche avait surtout mis l'accent sur l'impact de la législation elle-même et beaucoup moins sur le comportement et les perceptions des employeurs, ou sur leur contribution à cette tendance. Cet article veut enrichir la recherche orientée vers les employeurs en Nouvelle- Zélande. Il explore les points de vue des employeurs sur les avantages perçus de la négociation collective, comment les décisions de s'engager ou non dans le processus de négociation collective sont prises et les facteurs qui leur sont instrumentaux. Il y est démontré que la méthode préférée pour déterminer les salaires et les conditions de travail demeure la négociation individuelle. Cela est particulièrement le cas pour les organisations de moins de 50 employés, formant de loin la très grande majorité des fi rmes en Nouvelle-Zélande. Souvent, ces plus petites organisations ne perçoivent pas les avantages qu'elles pourraient tirer de la négociation collective. Dans l'ensemble, les résultats suggèrent qu'en dépit d'une décennie de législation du travail plus favorable, il y a peu de signes que le déclin de la couverture de la négociation qui s'opère depuis 20 ans soit près de se renverser.

Mots-clés :

- employeurs,

- syndicats,

- négociation collective,

- attitudes,

- Unitaristes

Resumen

Durante los años 1990 en Nueva Zelanda, la descentralización del mercado de trabajo y la nueva legislación en materia de empleo condujeron a un deterioro abrupto de la sindicalización y de la población al empleo que es cubierta por la negociación colectiva. Esas tendencias continuaron mas tarde durante los anos 2000, incluso después de la introducción de una legislación mas favorable a la negociación colectiva, la Ley de relaciones laborales 2000 (LRL) del ano 2000. La LRL introducía, en efecto, nuevas reglas en materia de negociación colectiva incluyendo una obligación de negociar de buena fe, un incremento de los derechos sindicales, y promovía la negociación colectiva en tanto que elemento central para el desarrollo de relaciones laborales productivas. A este respecto, la LRL debía permitir un mayor espacio a la negociación colectiva y promover la renovación sindical. A pesar de estas predicciones y de la intención general de la LRL, el deterioro de la cobertura de la negociación colectiva que ya había comenzado durante los anos 1990 continuó en el sector privado. Se quiso saber porqué la LRL no ha permitido contrarrestar, o al menos poner un freno a esta tendencia de decrecimiento. Hasta ahora la investigación había puesto el acento sobretodo en el impacto de la legislación en sí misma y mucho menos en el comportamiento y las percepciones de los empleadores o sobre su contribución a esta tendencia. Este artículo pretende contribuir a la investigación orientada hacia los empleadores en Nueva Zelanda. Se explora los puntos de vista de los empleadores sobre las ventajas percibidas respecto a la negociación colectiva, cómo se adoptan las decisiones de implicarse o no en el proceso de negociación colectiva y los factores que les sirven de instrumento. Se demuestra que el método preferido para determinar los salarios y las condiciones de trabajo sigue siendo la negociación individual. Es particularmente el caso de las organizaciones de menos de 50 empleados, que forman de lejos la gran mayoría de las empresas en Nueva Zelanda. Frecuentemente, esas pequeñas organizaciones no perciben las ventajas que podrían obtener de la negociación colectiva. En general, los resultados sugieren que a pesar de una década de legislación laboral mas favorable, hay pocos indicios que el deterioro de la cobertura de la negociación, que se opera desde hace 20 anos, pueda ser contrarrestado.

Palabras clave:

- empleadores,

- sindicatos,

- negociación colectiva,

- actitudes,

- unitaristas

Article body

Introduction

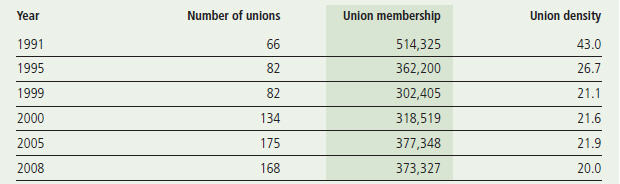

New Zealand employment relations have been in turmoil for at least 25 years, with major changes in the 1980s, the 1990s and post 2000. These changes had initially been driven by employers and their associations as they sought more decentralized and individualized employment relations practices. The pinnacle of this approach − the Employment Contracts Act 1991 (ECA) − abolished a nearly 100-year old system of state sponsored conciliation and arbitration. The ECA has been described as an employer charter (Anderson, 1991). It facilitated a steep decline in union density (see Table 1), a sharp reduction in collective bargaining coverage (see Table 2), a shift from industry and occupational based bargaining to workplace and individualized bargaining, and the emergence of new forms of employee representation (Dannin, 1997).

Table 1

Unions, Union Membership and Union Density, 1991-2008

Table 2

Private Sector Collective Bargaining Density, 1990-2009

The Employment Relations Act 2000 (ERA) and its subsequent amendments have taken a very different approach to employment relations. It is regarded as a more union friendly statute that has offered significant hopes for a reversal in the decline in union density and collective bargaining coverage experienced in the 1990s. Indeed, section 3(a) iii of the ERA specifically states that the promotion of collective bargaining is a key objective of the statute. New bargaining rules, including a good faith obligation, and increased union access and bargaining rights granted by the ERA, are regarded as fundamental to this objective. Despite the ERA’s intent, collective bargaining in the private sector has yet to undergo a process of renewal. Both collective bargaining coverage and union density have continued to decline under the ERA (see Tables 1 and 2) and it has naturally been questioned what the reasons are for the Act’s failure to reverse this trend. So far research has focused on whether the legislation itself is at fault, the role played by unions and employee attitudes to collective bargaining (see Rasmussen, 2009). There has been much less focus on employer behaviour and perceptions, the main exception has been a rather narrow debate on employer’s role in the “passing on” of collectively agreed terms and conditions to non-union employees (Waldegrave, Anderson and Wong, 2003).

This article reports on survey and interview research conducted as part of a national study of employers’ attitudes to collective bargaining and employment relations in New Zealand. The surveys demonstrate that employers’ preferred method of pay and conditions settlement is through individual bargaining. Frequently, smaller organizations (those with less than 50 employees) see no perceived benefits from collective bargaining and feel it is irrelevant to their business. Interestingly, even organizations that have a history of collective bargaining find little in the way of perceived benefits. Overall, this is consistent with numerous other research findings on employer attitudes (e.g. Freeman and Medoff, 1984; Geare, Edgar and McAndrew, 2006). Public policy changes post 2008 have been less supportive of unions, collective bargaining and employee protections and these changes could further marginalize unions and collective bargaining. Overall, these trends and the findings of this research strongly suggest future improvement in collective bargaining coverage is unlikely in the current employment relations environment.

Employment Relations in New Zealand

New Zealand has a colourful employment relations history, having ventured through a full range of employment relations systems over the past 30 years, each giving a different shape and character to collective bargaining.

For over 90 years, from 1894, the predominant system was one of compulsory conciliated bargaining for blanket-coverage awards, backed by the availability of arbitration if needed. Some awards were limited to local industry labour markets, but many of them were regional or national in scope. Conciliated bargaining for award renewals was the order of the day, but given the broad coverage of so many documents, opportunities for involvement in bargaining were limited. Awards were negotiated by necessarily limiting the number of representatives of employers and employees and their respective organizations. To most employers and employees the bargaining process was pretty remote. Fixed wage relativities and the tendency towards common wage movements across industry meant that much award bargaining was confined to just a few days, with the outcome being fairly predictable. There were limited exceptions in some industries where second-tier bargaining for above award rates produced some vigorous and localized negotiations. There were also industries and workplaces in which employment relations were notoriously difficult and the bargaining hard-nosed and uncompromising year after year (for an overview of this system, see Rasmussen 2009: 51-74). While major employers had first-hand experience of direct collective bargaining, during this period most employers had limited or no experiences of negotiating with unions as this was carried out on a centralized basis (Holt, 1980; McAndrew and Hursthouse, 1990).[1]

From the 1970s onwards, there were concerns that this system had difficulty adjusting to economic volatility. It conserved outdated organizational structures and bargaining behaviour and necessitated excessive state involvement in collective bargaining (Boston, 1984; Walsh, 1989). As such, there were considerable legislative adjustments to the conciliation and arbitration system in the 1970s and 1980s (Walsh, 1993). These gathered speed in the post-1984 period when between 1984 and 1990 an incoming Labour government went about deregulating all aspects of the New Zealand economy. There was considerable pressure from the New Zealand Business Roundtable, a rightwing lobby group, Treasury, and its own Minister of Finance to improve the efficiency of the labour market. The government introduced the Labour Relations Act 1987 which tried to facilitate more enterprise bargaining, and labour market flexibility (Deeks and Boxall, 1989). Generally, these were attempts to decentralize bargaining and allow more flexible bargaining outcomes, however, this had limited effect as the previous system continued to provide detailed minima for most employees and traditional patterns of occupational and industry wage relativities continued until the end of the 1980s (Harbridge and McCaw, 1989).

An Employment Relations “Revolution”: The Employment Contracts Act 1991

The ECA cut short the fine-tuning attempts of the 1980s and radically transformed New Zealand employment relations. It was based on neo-classical economics, a libertarian philosophy and contained few of the principles associated with the arbitration model. The ECA abolished the award system, removed union monopoly rights and facilitated enterprise-bargaining in the private and public sector. Compared to the previous employment legislation the ECA was also far less prescriptive in relation to bargaining and employment relationships (Grills, 1994; Deeks and Rasmussen, 2002: 67-72). This prompted a sharp fall in union density and in collective bargaining coverage (see Tables 1 and 2). Union density halved to around 20% in just a matter of 5 years and collective bargaining moved from being a largely national or industry level arrangement to being a process that occurred mainly at workplace level with most employees being covered by individualized employment agreements.[2]

Coupled with labour market changes, including high unemployment throughout the 1990s, the ECA shifted bargaining power and outcomes substantially. Although significant regional, industry and occupational variations existed, this was a new situation for many employers and employees and surveys revealed that even “mainstream employers” were implementing radical changes to their employment arrangements and conditions (Heylen Research Centre, 1992 and 1993). Traditional penal rates and overtime rates were modified or abolished, there was an increase in atypical employment patterns and many employees had to accept greater job and income insecurity (Barrett and Spoonley, 2001; Conway, 1999).

Unsurprisingly, research indicates that employers’ attitudes shifted toward a more Unitarist perspective in the post 1991 period. Research conducted on behalf of the New Zealand Department of Labour found that under the ECA it was the employer who normally decided the bargaining unit associated with collective bargaining and made the choice between collective or individual agreements (Heylen Research Centre, 1992 and 1993). It was also found that some employers were adopting new bargaining approaches and seeking substantial bargaining concessions. Research by McAndrew (1993: 183) found that amongst several groups of employers conventional bargaining behaviour has not been widely evident, for the most part initial management proposals appear to have been accepted with only minor if any modifications and with little debate. In was into this climate that a new Labour Government was elected in 1999 and new legislation was introduced in 2000.

The Employment Relations Act 2000: An Attempt to Rekindle Collectivism

Between 1999 and 2008, a Labour-led coalition government pursued different economic, social and employment relations policies (to the National government of the 1990s), inspired by “social democracy” and “third way” philosophies (Haworth, 2004). These included an emphasis on bipartite and tripartite policy formulations and implementation, workplace partnerships, increased investments in industry training and a considerable expansion of statutory employment minima. The Employment Relations Act 2000 (ERA) and its amendments promoted explicitly collective bargaining and made numerous changes to facilitate union membership growth (Rasmussen, 2009). Union registration was re-introduced, collective agreements could only be negotiated by unions, the ability to strike in connection with multi-employer bargaining was re-introduced, “passing on” of union-negotiated improvements (“free-riding”) was constrained, unions’ workplace access was improved and bargaining behaviour was influenced by the legal requirement to bargain in “good faith.” These changes were broadly intended to promote collective bargaining as the basis of good faith productive employment relationships and they were expected to reverse a decade of decline in union density and collective bargaining coverage (Wilson, 2004).

Despite the intent of the ERA, both union membership and collective bargaining coverage have continued to decline in the private sector where collective bargaining density fell to less than 10% (see Tables 1 and 2). Comprehensive research on employers, unions and employees found that the Act had had far less impact than expected (Waldegrave, Anderson and Wong, 2003). This trend is more complex than it seems as the figures in the 1990s included both union and non-union negotiated collective agreements (the latter agreement being associated with “collective contracting”).[3] The prohibition of “collective contracting” under the ERA meant that many of these so-called collective employment contracts negotiated without unions lapsed into individual agreements (Waldegrave, Anderson and Wong, 2003). Thus, the decline in collective agreements in the private sector may have been exaggerated by the disappearance of non-union negotiated collective agreements (May, Walsh and Kiely, 2004: 12).

In an overview of existing research (Rasmussen, 2009: 129-133), it has been suggested that the following explanatory factors are important to the decline in collective bargaining and union density: employer resistance or lack of support, employee apathy or lack of interest, the inability of unions’ to gain ground on multi-employer collective agreements, and the existence of a “representation gap.” Thus, employer resistance or antipathy can only be seen as one of several factors in a rather complex decision-making process surrounding collective bargaining. Employer attitudes are linked, however, to a number of issues which have figured prevalently when the reduction in union density in the private sector has been discussed. Significantly, research also indicates that negative attitudes toward unions and collective bargaining have become ensconced since the ECA, especially amongst employers without previous experience of collective bargaining.

While survey and case study research has found limited evidence of overt employer hostility to collective bargaining, there have been indications that employer attitudes can have some influence on employees’ interest in pursuing collective bargaining (Waldegrave, Anderson and Wong, 2003). One of the major issues under the ERA has been “free-riding” or the “passing on” of union-negotiated improvements to non-unionized employees. This may make sense for the employer in terms of transaction costs, workplace harmony and fairness considerations but it can clearly undermine the benefits associated with being a union member. There is also the well-known employer hostility to multi-employer bargaining which has effectively blocked unions’ interest in moving away from enterprise-based bargaining arrangements.

The benefits of union membership, and by proxy collective bargaining, may also have been undermined by two other contextual factors. First, in a tight labour market with extensive skill shortages, employers have been keen to attract and retain skilled staff and this has coincided with above-inflation average pay rises and individualized rewards and employment conditions in the 2000-2008 period. Second, the government’s attempt to lift employment standards through higher and more encompassing statutory minima may also have undermined the perceived relevance of unionism (Rasmussen, Hunt and Lamm, 2006). In many low-paid sectors (which frequently have relatively low union density, anyway), the statutory minima often constitute a clear guideline for actual wage rates and employment conditions. This raises the question of why workers should pay union fees when there may be few perceived benefits?

In summary, the Employment Relations Act 2000 has not delivered the expected new growth in collective bargaining. In a matter of just 20 years, there has been a decentralization (workplace-based collective bargaining has become the dominant collective bargaining mode) and individualization of bargaining. Over 90% of private sector employees are now covered by individual employment agreements and this aligns with the preferred mode of bargaining amongst employers.

Survey and Interviews of Employers Attitudes

Methodology

Three surveys were carried out providing a national coverage of private sector organizations employing ten or more staff (for a more detailed description, see Cawte, 2007; Foster, Murrie and Laird, 2009; Foster and Rasmussen, 2010). These were undertaken using a cross-sectional survey design where the surveys matched the sample demographics used by previous New Zealand studies (McAndrew, 1989; McAndrew and Hursthouse, 1991). It also allowed the entire population of employers (6800 individual firms) to be surveyed and employers within all seventeen standard industry classifications used by previous researchers could be included (e.g., Blackwood et al., 2007).

Survey

The three surveys involved a self-administered questionnaire in two regions (firstly, Taranaki, Manawatu-Wanganui and Hawkes Bay, and secondly Wellington and South Island). A hard copy was mailed to respondents in 2005 and 2008 respectively and in the third region (the upper half of the North Island) an online survey was used which was carried out in 2007. Three separate surveys were carried out because the researchers were originally going to test the attitudes of employers only in the catchment of Massey University which is the central part of the North Island. The second survey was carried out by a post graduate student as part of her dissertation. The final survey was carried out as the researchers managed to obtain significant funding to complete a national survey.

The response rates from the two postal surveys resulted in acceptable response rates of 20.1% and 19.0% respectively, whereas the online survey only produced a disappointing 8.0% response rate. The reasons for the low online response rate could be attributable to the disadvantages associated with conducting such surveys, which include participants’ time (Wright, 2005), concerns about participants’ representation (McDonald and Adams, 2003) and the possible threat of internet viruses (Fricker and Schonlau, 2002). Overall, there were 892 responses out of the total sample of 6800 private sector organizations, resulting in an overall response rate of 13.1%, acceptable by comparative studies. The questionnaire sought to gauge employer opinions and attitudes to collective bargaining, which, because of the questionnaire length, had to involve very specific questions. Therefore, participants were also asked if they wanted to partake in semi-structured interviews which would allow the researchers to extract any underlying issues that could not be gleaned from a questionnaire.

Interviews

We received 120 acceptances for participating in interviews and of these, 60 employers were selected to be interviewed; 30 employers not engaged in collective bargaining and 30 who were. This also ensured that participants covered the various regions of New Zealand, represented a wide range of industries and held positions as HR managers, owner managers and general managers. The interviews, using a semi-structured schedule, were all conducted by telephone and taped. Responses were transcribed and thematic analyses conducted on the findings.

Results

The study divided the respondents into two groups, those currently involved in collective bargaining with unions, and those not currently involved. The overall results showed a strong correlation between the responses of each group, with a few key exceptions. Areas of commonality were found in respondents’ attitudes toward collective bargaining such as transactional costs and their views on factors that would increase its coverage such as the introduction of compulsory unionism. It was in relation to the perceived benefits of collective bargaining that the responses and attitudes of each group were found to differ significantly.

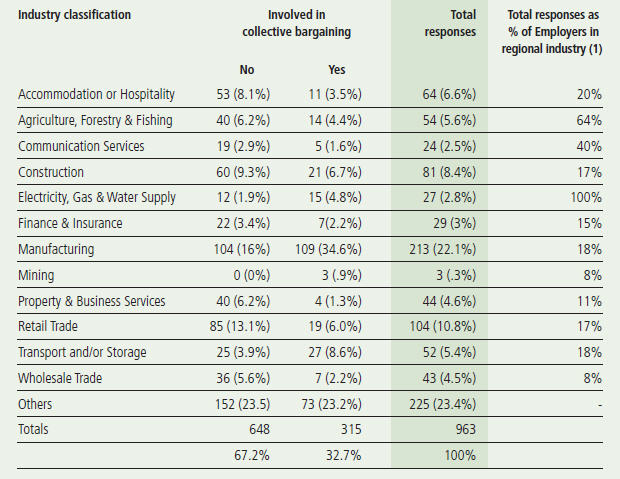

Table 3 provides a detailed representation of the distribution of the sample across standard industry classifications, and the extent to which respondent employers in each classification are involved in collective bargaining. The main concentration of collective bargaining is in manufacturing (34.6%), retail (6.0%), transport (8.6%), and construction (6.7%). Please note that the industry classification of “Others” is approximately 24% of the total.

Table 3

Proportion of Respondents Involved in and Not Involved in Collective Bargaining by Industry Classification

The results of Table 4 demonstrate that there is uniformity across all regions with approximately two-thirds of respondents not being involved in collective bargaining and one-third being involved.

Table 4

Regional Coverage by Collective Bargaining

Respondent’s Attitudes to Collective Bargaining

Table 5 sets out responses to the question: how do the attitudes of employers who are engaged in collective bargaining compare with those who are not? Those variables that are of significance showed marked differences such as the interest of employees in the process, its relevance to the business, and whether it has been considered. Of those engaged in collective bargaining, only 21% believed their employees lacked interest in the process. Of those not engaged, the proportion is reversed with 70.1% arguing their employees lacked any form of interest in collective bargaining.

Table 5

Respondents Attitudes to Collective Bargaining

# Chi-squared test for differences in more than two proportions. *** P < 0.000; CB = Collective Bargaining

Similar differences were found in the proportion of respondents who agreed that collective bargaining was not relevant to their business; 15.9% of those engaged agreed versus 74.1% of those not engaged in the process. Further strong differences can be seen when employers were asked if they had considered engaging in the collective bargaining with 74.8% of those not currently engaged having never done so against 6.2% of those engaged. It is interesting to note that even firms involved in collective bargaining agree with those not involved in collective bargaining on the point that individual bargaining offers greater benefit. Many employers involved in collective bargaining found that the transactional costs were high (31.8% agreed).

Table 6 illustrates the factors that our respondents believe would contribute to an increase in collective bargaining coverage, again comparing those employers involved in collective bargaining and those not involved as separate sub-samples. Only two factors attracted a high level of agreement amongst those employers not involved with unions or collective bargaining. In their collective view, only research showing the value of collective bargaining or business groups endorsing collective bargaining would increase collective bargaining coverage. Amongst employers engaged in collective bargaining there are several factors that could increase collective bargaining coverage, with “workers showing more interest” attracting 62% support and 56.9% agreeing with the statement: “research showing value of collective bargaining.”

Table 6

Respondents Views of the Factors that Would Increase Collective Bargaining Coverage

Perceived Benefits of the Collective Bargaining Process

Table 7 shows the perceived benefit or not of the collective bargaining process by employers with or without CEAs. Respondents selected from a list of variables widely described and commonly held by literature as being key benefits of collective bargaining to firms, though room was given for additional benefits to be self-identified by participants.

Table 7

Perceived Benefits of the Collective Bargaining Process

Again there is a significant difference in the profiles of the two sub-samples, although only minorities in both groups saw any benefits at all from being involved with collective bargaining. For both groups, reducing conflict between employer and employees in the workplace was an often cited advantage to be gained from collective bargaining; this was particularly pronounced with the group of employers presently involved in collective bargaining. Interestingly, employers not engaged in collective bargaining had 17.6% agreeing that collective bargaining could improve the ability of firms to restructure and design jobs.

Only very small minorities of the non-bargaining sub-sample saw any benefits to them at all from becoming involved with unions and collective bargaining. In the bargaining group, just under half endorsed collective bargaining as reducing conflict, while there were quite substantial minorities (in the neighbourhood of one-quarter) endorsing each of the other listed benefits – improving productivity, assisting management’s ability to manage, and facilitating restructuring and modernizing of production technologies.

Interview Analysis

Employers – whether engaged (CB-YES; n = 30) or not engaged (CB-NO; n = 30) in collective bargaining – demonstrated a consistent attitude that union involvement had a detrimental impact on the employer – employee relationship, and that the principal benefit of collective bargaining (where one was argued to exist) was procedural only. Attitudes toward unions were regarded as significant as, under the ERA, only unions may negotiate a collective agreement with an employer. Consequently, attitudes towards unions and collective bargaining frequently go hand in hand. Interviews showed that collective bargaining was seen as positive where it allowed employers to simplify management of the contractual relationship between employers and employees, but not the substantive inter-personal one which still relied upon the success of individual managerial initiatives. However, the opposite opinion was taken by those not involved in collective bargaining who argued strongly that standardization of terms and conditions through third party collective bargaining was wholly detrimental. Though how this was reconciled with the use of standardized individual employment agreements was not explained.

I don’t believe it works, I simply don’t believe it works, collective bargaining, there just can’t be any advantage, it breeds mediocrity and that’s all it means to me... to me it’s just a stone-age thing, goes back to the 20s and 30s of the last century. (CB-NO)

These attitudes, while generally similar, showed some variations when responses of employers engaged in collective bargaining were compared with those who were not. For those engaged in collective bargaining the detrimental impact of union involvement in the employer-employee relationship occurred predominantly as a consequence of spill over from inter- and intra-union dialogue into the employee-employer dynamic. On multi-union sites some employer responses indicated that conflict between unions and union members would prolong and unnecessarily complicate the bargaining process, but was otherwise workable. In extreme circumstances such conflict would have a detrimental impact on the employer-employee relationship. This was a consequence reported by both employers engaged and not engaged in collective bargaining. When taken as part of the complete narrative, these responses often highlighted a belief that third party involvement in the employment relationship was both an unnecessary and a negative influence on the employment relationship.

I think a disadvantage of having a union is that the employer relationship becomes more political than it needs [to be]... the noise of the vocal few becomes the norm for everyone and I think that can create a bullying culture within the workplace. (CB-NO)

Also significant was the impact of the personalities of individual union representatives on the bargaining dynamic and the employer–employee relationship. In some cases the employment relationship was argued to suffer where union members would adopt the attitudes of particularly confrontational delegates.

It affects staff. Every time we move into collective bargaining we have I would say unhappiness in the firm. There seems to be a division of our staff. I would say it causes conflict in the business which we don’t experience you know between times if you like. (CB-YES)

This latter attitude was usually accompanied, when probed further, by suggestions that management-employee relationships were sound and happy workers did not require a union presence or collective bargaining. Overall, these responses suggest that the legislative monopoly unions have on collective bargaining may be a significant barrier to employers accepting the process; particularly where employers viewed both it and unions in a negative light.

This attitude was exemplified when respondents – both engaged and not engaged in collective bargaining – argued that a key handicap of third party (union) involvement in the workplace was the introduction of national union agendas and interests into the firm. These would typically be at odds with the specific interests and needs of the firm, both financial and relational, and served to undermine and prolong collective negotiations where they occurred. Several responses were indicative of employer preference for enterprise level bargaining arrangements.

A disadvantage of collective bargaining you get the unions pushing... a particular mandate which tends not to be site specific. It tends to be something they are pushing nationally. They are pushing something that’s not particularly of interest to the guys on site. (CB-YES)

It was very difficult to get the union to take any sort of offer the company made back to its members for ratification. (CB-YES)

This also reflected a belief that unions were not able, or perhaps unwilling, to fairly represent workers’ interests where they diverged from such national mandates.

We had a strike a couple of years ago that was basically perpetrated by a union agenda. There was a national agenda that the [union] negotiators were driving and the negotiators were from outside [the firm] and they were trying for some political movement using us as a means to an end. (CB-YES)

Employers expressed a strong belief that employees would be better served by the removal and/or absence of third party interests from their firm and presumably the collective bargaining they were associated with. While benefits could occur by having a third party involved, at least by those currently negotiating collectively, there was an underlying Unitarist theme arguing the benefit would exist only in so far that any union involved was capable of sharing the firm’s interests and restricting itself to managing the process of bargaining only.

Conclusions

What we have presented are the results of research into employment relations context and the views of “mainstream” New Zealand employers on collective bargaining and its impact or likely impact on their organizations. We have presented the data in aggregate form in two sub-samples – those employers who presently are engaged in collective bargaining and those who are not. Several points stand out quite clearly.

Firstly, employers who are not engaged in collective bargaining almost unanimously reject the option of collective bargaining. They believe that their employees have no interest in unions or collective bargaining, a finding that is consistent with other contemporary New Zealand research that says which most business managers have a Unitarist view of employment relations at their workplace (Geare, Edgar and McAndrew, 2006 and 2009).

Secondly, the sub-sample of employers who are involved in collective bargaining is unconvinced that collective bargaining offers the benefits argued for by research e.g., improvements in productivity and managerial freedom, reductions in workplace conflict and the facilitation of organizational change. It was noteworthy that the views of these participants are substantially more favourable toward, or perhaps only tolerant of, collective bargaining than the sub-sample of non-participating employers. Substantial minorities saw benefits from collective bargaining in each dimension, most obviously on reducing workplace conflict but on the others as well.

Thirdly, substantial majorities of the employers who participate in collective bargaining appear to be quite comfortable with the process. While close to half think that it takes too long, most are relaxed about the transactional costs of the process, and they believe that they know how to bargain and what to bargain about. They are, as a group, considerably more relaxed about the process than those employers who are not involved in it. Their views on factors which might lead to a spread of collective bargaining can also be interpreted to mean that they have, again as a group, a more flexible and pragmatic, less ideological or intimidated view of collective bargaining than those employers who are not presently involved in it.

Finally, there are factors other than employer resistance credited with the decline in unionization and collective bargaining coverage. Legislative regimes, worker apathy, labour market conditions and union strategies and limited resources are among them. In this paper, our focus has been on auditing where New Zealand employers stand on collective bargaining, and assessing the role of employer resistance – initially at the attitudinal level – in containing the spread of collective bargaining, despite the sympathetic environment created by the ERA. It would appear that despite this highly favourable environment (albeit not as favourable as the pre-1991 arbitration and conciliation system) collective bargaining will remain marginalized within the New Zealand private sector. Employer attitudes, even those of employers actively engaged in the process, further suggest little prospect of any substantial renewal of collective bargaining coverage in this country. The question then remains what steps could be taken to reverse the 20 year decline in union density and collective bargaining coverage, or indeed should any steps be taken at all?

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

It is often difficult to explain to current New Zealand employment relations students that most employers were not involved in collective bargaining. “The arbitration system divorced wage fixing from the concerns of individual enterprises and from the purview of individual workers. For employers and workers alike, basic wage rates were something established through mysterious processes in smoke-filled rooms in Wellington. These centralised wage-fixing processes were dominated by full-time paid officials and advocates on both sides, with the individual members of unions and employers associations in the role of, predominantly, spectators. The limited amount of direct bargaining at plant and enterprise level meant bargaining and negotiation skills became largely the preserve of full-time union and employer officials.” (Rasmussen, 2009: 63).

-

[2]

While the terminology has shifted under different pieces of legislation from employment contracts to employment agreements the same terminology – employment agreements – will be used throughout this article.

-

[3]

Under “collective contracting” employees are nominally covered by a collective agreement but no collective bargaining actually takes place – there is no union involvement – as the collective agreement is developed by the employer and normally employees sign the agreement one by one (Dannin, 1997; Dannin and Gilson, 1996).

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Barry Foster is Lecturer at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Erling Rasmussen is Professor at Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand.

John Murrie is Tutor at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Ian Laird is Associate Professor at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

References

- Anderson, Gordon. 1991. “The Employment Contracts Act 1991: An Employer’s Charter?” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 16 (2), 127-142.

- Anderson, Gordon. 2004. A New Unionism? The Legal Definition of Union Structures in New Zealand. AIRAANZ 2004: Proceedings of the 18th Association of Industrial Relations Academics of Australia and New Zealand Conference. Noosa, 3rd - 6th February.

- Barrett, Peter and Paul Spoonley. 2001. “Transitions: Experiencing Employment Change in a Regional Labour Market.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 26 (2), 171-185.

- Blackwood, Linda, Goldie Feinberg-Daneili, George Lafferty, Paul O’Neil, Jane Bryson and Peter Kiely. 2007. Employment Agreements: Bargaining Trends and Employment Law Update 2006/2007. Wellington: Industrial Relations Centre, Victoria University of Wellington.

- Blumenfeld, Stephen. 2010. “Collective Bargaining.” Employment Relationships: Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 40-55.

- Boston, Jonathan. 1984. Incomes Policy in New Zealand: 1968-1984. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

- Boxall, Peter. 1993. “Management Strategy and the Employment Contracts Act 1991.” Employment Contracts: New Zealand Experiences. R. Harbridge, ed. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 148-164.

- Burton, Barbara. 2004. “The Employment Relations Act according to Business New Zealand.” Employment Relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 134-144.

- Burton, Barbara. 2010. “Employment Relations 2000-2008: An Employer View.” Employment Relationships: Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 94-115.

- Carroll, Peter and Paul Tremewan. 1993. “Organising Employers: The Effect of the Act on Employers and Auckland Employers Association.” Employment Contracts: New Zealand Experiences. R. Harbridge, ed. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 185-196.

- Cawte, Tenisha. 2007. Employers’ Attitudes Toward Collective Bargaining: A Comparative Study. Honours Degree Dissertation. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- Conway, Peter. 1999. “An ‘Unlucky Generation?’ The Wages of Supermarket Workers Post-ECA.” Labour Market Bulletin, 1 (1), 23-50.

- Cullinane, Joanna and Diana McDonald. 2000. “Personal Grievances in New Zealand.” Research on Work, Employment and Industrial Relations 2000. Proceedings, the 14th AIRAANZ Conference. J. Burgess and G. Strachan, eds. Newcastle, 2-4 February, 52-60.

- Dannin, Ellen, and Clive Gibson. 1996. “Getting to Impasse: Negotiations under the National Labour Relations Act and the Employment Contracts Act.” American University Journal of International Law and Policy, 11, 917.

- Dannin, Ellen. 1997. Working Free: The Origins and Impact of New Zealand’s Employment Contracts Act. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Deeks, John and Peter Boxall. 1989. Labour Relations in New Zealand. Auckland: Longman Paul.

- Deeks, John and Erling Rasmussen. 2002. Employment Relations in New Zealand. Auckland: Pearson Education New Zealand.

- Deeks, John, Jane Parker and Rose Ryan. 1994. Labour and Employment Relations in New Zealand. Auckland: Longman Paul.

- Department of Labour. 2009. The Effect of the Employment Relations Act 2000 on Collective Bargaining. Wellington: Department of Labour. www.dol.govt.nz (accessed June 9, 2010)

- Foster, Barry and Erling Rasmussen. 2010. “Employers’ Attitudes to Collective Bargaining.” Employment Relationships: Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 116-132.

- Foster, Barry, John Murrie and Ian Laird. 2009. “It Takes Two to Tango: Evidence of a Decline in Institutional Industrial Relations in New Zealand.” Employee Relations, 31 (5), 503-514.

- Freeman, Richard B. and James L. Medoff. 1984. What Do Unions Do? New York: Basic Books.

- Fricker, R. and M. Schonlau. 2002. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Internet Research Surveys: Evidence from the Literature.” Field Methods, 14 (4), 347-367.

- Geare, Alan, Fiona Edgar and Ian McAndrew. 2006. “Employment Relationships: Ideology and HRM Practice.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17 (7), 1190-1208.

- Geare, Alan, Fiona Edgar and Ian McAndrew. 2009. “Workplace Values and Beliefs: An Empirical Study of Ideology, High Commitment and Unionisation.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20 (5), 1146-1171.

- Gilson, Clive and Terry Wager. 1998. “From Collective Bargaining to Collective Contracting: What is the New Zealand Data Telling Us.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 23 (3), 169-180.

- Grills, Walter. 1994. “The Impact of the Employment Contracts Act on Labour Law: Implications for Unions.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 19 (1), 85-101.

- Harbridge, Raymond and Stuart McCaw. 1989. “The First Wage Round under the Labour Relations Act 1987: Changing Relative Power.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 14 (2), 149-167.

- Harbridge, Raymond, and Glen Thickett. 2003. Unions in New Zealand: A Retrospective. AIRAANZ 2003: Proceedings of the 17th Association of Industrial Relations Academics of Australia and New Zealand Conference. Melbourne, 4th - 7th February.

- Harris, Paul and Linda Twiname. 1998. First Knights. Auckland: Howling at the Moon Publishing.

- Haworth, Nigel. 2004. “Beyond the Employment Relations Act: The Wider Agenda for Employment Relations and Social Equity in New Zealand.” Employment Relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 190-205.

- Hector, Janet and Michael Hobby. 1998. “Labour Market Adjustment under the Employment Contacts Act: 1996.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 23 (1), 311-327.

- Heylen Research Centre and Teesdale Meuli and Co. 1992. A Survey of Labour Market Adjustment under the Employment Contracts Act 1991. Wellington: Department of Labour.

- Heylen Research Centre. 1993. A Survey of Labour Market Adjustment under the Employment Contracts Act 1991. Wellington: Department of Labour.

- Holt, Jim. 1980. The Historical Legacy: The 1894 Conciliation and Arbitration Act. Paper presented as part of the winter lecture series on New Zealand’s industrial relations, Auckland University, 17 June.

- May, Robyn. 2003a. Labour Governments and Supportive Labour Law. Retrieved 18th August 2003 from http://www.actu.asn.au/cgi-bin/printpage/printpage.pl.

- May, Robyn. 2003b. New Zealand Unions in the 21st Century: A Review. AIRAANZ 2003: Proceedings of the 17th Association of Industrial Relations Academics of Australia and New Zealand Conference. Melbourne, 4th - 7th February.

- May, Robyn, and Pat Walsh. 2002. “Union Organising in New Zealand: Making the Most of the New Environment?” International Journal of Employment Studies, 10 (2), 157-180.

- May, Robyn, Pat Walsh, and Ian Kiely. 2004. Employment Agreements: Bargaining Trends and Employment Law Update 2003/2004. Wellington: Victoria University.

- McAndrew, Ian. 1989. “Bargaining Structure and Bargaining Scope in New Zealand: The Climate of Employers Opinion.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 14 (2), 149-167.

- McAndrew, Ian. 1993. “The Process of Developing Employment Contracts: A Management Perspective.” Employment Contracts: New Zealand Experiences. R. Harbridge, ed. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 165-184.

- McAndrew, Ian and Paul Hursthouse. 1990. “Southern Employers on Enterprise Bargaining.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 15 (2), 117-128.

- McAndrew, Ian and Paul Hursthouse. 1991. “Reforming Labour Relations: What Southern Employers Say.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 16 (1), 1-11.

- McDonald, H. and S. Adams. 2003. “A Comparison of Online and Postal Data Collection Methods in Marketing Collection.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21 (2), 85-95.

- Rasmussen, Erling. 2009. Employment Relations in New Zealand. Auckland: Pearson Education.

- Rasmussen, Erling. 2010. “Introduction.” Employment Relationships: Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1-8.

- Rasmussen, Erling and Danae Anderson. 2010. “Between Unfinished Business and an Uncertain Future.” Employment Relationships: Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 208-223.

- Rasmussen, Erling, Colm McLaughlin and Peter Boxall. 2000. “Employee Awareness and Attitudes: Survey Findings.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 25 (1), 49-67.

- Rasmussen, Erling, Vivienne Hunt and Felicity Lamm. 2006. “Between Individualism and Social Democracy.” Labour & Industry, 17 (1), 19-40.

- Waldegrave, Tony. 2004. “Employment Relationship Management under the Employment Relations Act.” Employment Relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 119-133.

- Waldegrave, Tony, Diana Anderson and Karen Wong. 2003. Evaluations of the Short Term Impacts of the Employment Relations Act 2000. Wellington: Department of Labour.

- Walsh, Pat. 1989. “A Family Fight? Industrial Relations Reform under the Fourth Labour Government.” The Making of Rogernomics. B. Easton, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Walsh, Pat. 1993. “The State and Industrial Relations in New Zealand.” State and Economy in New Zealand. B. Roper and C. Rudd, eds. Auckland: Oxford University Press, 172-191.

- Wanna, Jim. 1989. “Centralisation without corporatism: The Politics of New Zealand Business in the Recession.” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 14 (1), 1-16.

- Wilson, M. 2004. “The Employment Relations Act: A Framework for a Fairer Way.” Employment Relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act. E. Rasmussen, ed. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 9-20.

- Wright, K. B. 2005. “Researching Internet-based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10 (3) http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue3/wright.html

List of tables

Table 1

Unions, Union Membership and Union Density, 1991-2008

Table 2

Private Sector Collective Bargaining Density, 1990-2009

Table 3

Proportion of Respondents Involved in and Not Involved in Collective Bargaining by Industry Classification

Table 4

Regional Coverage by Collective Bargaining

Table 5

Respondents Attitudes to Collective Bargaining

Table 6

Respondents Views of the Factors that Would Increase Collective Bargaining Coverage

Table 7

Perceived Benefits of the Collective Bargaining Process