Abstracts

Abstract

While the union’s duty of fair representation (DFR) toward its members is well established in Canadian labour law, relatively little research has examined Canadian DFR cases or factors that may affect the outcome of DFR complaints. This paper examines 138 DFR cases filed with the British Columbia Labour Relations Board between 2000 and 2006. Only eight of the 138 cases resulted in a decision in favour of the complainant. The most common reasons for DFR complaints were the union’s alleged failure to pursue grievances relating to termination or to pursue grievances relating to job changes. The majority of complainants represented themselves in the process. Future research could expand upon these findings to improve understanding of the duty of fair representation and its application.

Keywords:

- labour law,

- union,

- duty of fair representation,

- complaint,

- British Columbia

Résumé

Le devoir de représentation équitable du syndicat envers ses membres est clairement établi dans le droit du travail canadien. On attend que les syndicats représentent leurs membres de manière non arbitraire, sans discrimination et de bonne foi. Ce devoir est interprété comme englobant les actions du syndicat durant les négociations collectives, ainsi que dans le cadre de ses autres interactions avec ses membres et afférentes à leurs intérêts, ce qui peut présenter un défi aux syndicats car on attend aussi d’eux qu’ils agissent pour protéger les intérêts collectifs de tous leurs membres. Le devoir de représentation équitable offre également aux membres du syndicat un recours externe s’ils pensent que les actions de leur syndicat ne sont pas équitables.

Relativement peu de recherches ont examiné les actions visant le devoir de représentation équitable au Canada, ou cerné les facteurs qui peuvent influer sur le traitement des plaintes de manquement à ce devoir. Ce document examine 138 plaintes associées à ce devoir déposées au British Columbia Labour Relations Board (Conseil des relations du travail de Colombie-Britannique) entre 2000 et 2006. Dans chaque cas, l’information suivante a été enregistrée : l’identité des parties en cause, s’il s’agissait d’un plaignant ou d’une plaignante, le fondement de la plainte, la résolution de la plainte, et si une des parties ou toutes étaient représentées par un avocat durant les délibérations.

L’article 12 du Code des relations du travail de Colombie-Britannique décrit brièvement le devoir de représentation équitable. Les plaignants déposant une plainte en vertu de l’article 12 doivent payer un droit de dépôt de 100 dollars. Le Conseil rend disponible la documentation sur son site Web, en expliquant la démarche de résolution de la plainte et avisant les plaignants éventuels des résultats de plaintes antérieures associées au devoir de représentation équitable qui ont établi des normes et des lignes directrices relatives à l’évaluation par le Conseil des plaintes déposées en vertu de l’article 12. Les données du Conseil indiquent que les plaintes associées à ce devoir représentaient entre 4 % et 8 % du nombre des causes déposées chaque année entre 2001 et 2005. La majorité de ces plaintes ont été rejetées par manque d’établissement d’une preuve prima facie.

Les résultats de cette analyse indiquent que seules huit des 138 affaires examinées ont abouti en faveur du plaignant. Les syndicats qui faisaient le plus souvent l’objet d’une plainte associée au devoir de représentation équitable étaient de grands syndicats représentant de multiples lieux de travail et des travailleurs dans diverses occupations. Les industries qui, le plus souvent, ont donné lieu à des plaintes associées à ce devoir étaient celles de la construction, des soins de santé et de l’assistance sociale, et de l’administration publique. Les raisons les plus courantes de ces plaintes étaient le prétendu manquement du syndicat à poursuivre un grief concernant une cessation d’emploi ou des griefs concernant des changements de poste. La majorité des plaignants n’ont pas cité un type spécifique de comportement de la part du syndicat (comportement arbitraire, discrimination ou avoir agi de mauvaise foi) en soumettant leur plainte. Il n’y avait pas de différences évidentes entre les plaignants et plaignantes en ce qui concerne le nombre de plaintes déposées ou le résultat des plaintes.

Les résultats de l’analyse suggèrent plusieurs orientations que devraient suivre la recherche future. Il n’est pas clair si le nombre de plaintes associées au devoir de représentation équitable déposées, et le taux de succès de ces plaintes, représentent réellement le nombre de cas où un syndicat a en fait agit de façon inéquitable en représentant ses membres. Une autre considération consiste à déterminer s’il pourrait y avoir des circonstances, tel que le droit de 100 dollars à payer pour déposer une plainte, qui découragent des plaignants éventuels. Il semble également que plusieurs plaignants dans les causes analysées pourraient ne pas comprendre les implications des dispositions de l’article 12, ou comment ces dispositions sont appliquées pour déterminer le résultat des plaintes associées au devoir de représentation équitable, malgré l’information présentée sur le site Web du Conseil des relations du travail de C.-B. Le fait que de nombreux plaignants ne précisent pas la nature du comportement prétendument inéquitable du syndicat valide cette possibilité. On pourrait toutefois faire valoir qu’en raison de la disparité potentielle sur le plan des connaissances et des ressources entre le plaignant et le syndicat, les conseils des relations du travail devraient faire preuve d’une certaine souplesse ou latitude lorsqu’ils appliquent la « lettre de la loi » dans les causes relatives au devoir de représentation équitable.

La recherche future pourrait approfondir ces constatations en examinant plus en détail les caractéristiques des plaintes associées au devoir de représentation équitable qui ont eu des résultats positifs et négatifs. Les formes qualitatives de collecte de données, telles que les entrevues avec les plaignants ou avec les représentants syndicaux qui traitent avec ces plaintes, serviraient grandement à recenser éventuellement des facteurs moins tangibles qui influent sur le dépôt ou les résultats d’une plainte de manquement au devoir de représentation équitable qui pourraient ne pas être détectés par des formes plus quantitatives d’analyse. Les caractéristiques de ces plaintes pourraient aussi être évaluées en fonction d’autres dimensions, comme par exemple en fonction de différentes sphères de compétence et à différentes dates.

Mots-clés:

- droit du travail,

- syndicat,

- devoir de juste représentation,

- plainte,

- Colombie-Britannique

Resumen

Mientras el deber de justa representación (DJR) de parte del sindicato hacia sus miembros está bien establecido en las leyes laborales canadienses, son relativamente pocas las investigaciones que han examinado los casos DJR en Canadá o los factores que pueden afectar los resultados de las quejas respecto al DJR. Este documento examina 138 casos DJR seguidos por la Oficina de relaciones laborales de Colombia Británica entre 2000 y 2006. Solo ocho de los 138 casos resultaron en una decisión a favor del demandante. Las razones más comunes para presentar quejas fueron el fracaso alegado por el sindicato para proseguir los recursos relativos a la cesación de empleo o los recursos relativos a cambios de empleo. La mayoría de demandantes se representaron ellos mismos durante el proceso. Investigaciones futuras podrían desarrollar más ampliamente estos resultados para mejorar la comprensión sobre el deber de justa representación y su aplicación.

Palabras clave:

- ley laboral,

- sindicato,

- deber de justa representación,

- queja,

- Colombia Británica

Article body

The duty of fair representation (DFR), as established in Canadian labour law, places upon a trade union “in its capacity as bargaining agent…some obligation to the employees it represents in the bargaining unit” (Adams, 1985). Nevertheless, despite the importance of DFR legislation as a mechanism to provide union members with a means of holding their unions accountable for actions or decisions, relatively little research has investigated the substance or disposition of DFR cases. The purpose of this paper is to examine a set of DFR complaints in order to identify the common characteristics of these cases.

Research Context: The Development of the Duty of Fair Representation

The concept of the duty of fair representation was first developed in the United States in the mid-1940s through the outcome of two Supreme Court cases (Adams, 1985). Both cases involved unions which were found to have practiced racial discrimination against black employees through supporting various forms of restrictions on their employment. The Supreme Court found the DFR expectation to be grounded in the contractual relationship between the union and the members it represented, and in constitutional law guaranteeing individuals the freedom from discrimination. It ruled that the union had a duty to represent all of its members and “to act for and not against those who it represents” (Adams, 1985: 711). In Canada, the DFR expectation was initially developed through labour relations boards’ decisions starting in the early 1960s, which initially drew on an implied rather than a statutory expectation. However, the DFR expectation is now enshrined in legislation or through a common law obligation in every Canadian jurisdiction (Lynk, 2002).

The DFR expectation poses a number of challenges for the unions whose actions it regulates. The DFR addresses “the need to protect individuals from the collective sanctioned on their behalf” (Bentham, 1991: 2). In other words, while unions are expected to act for the betterment of all their members, the DFR obligation recognizes that actions taken on behalf of a collective whole may have negative effects on individuals within that whole. Unions who represent diverse constituencies thus must be careful that their actions do not result in undue impact on a subsection of their constituents.

Along with the widened scope of applicability of DFR, a few general principles have emerged through labour relations board decisions that outline the practical implications of the DFR expectation. Generally, Canadian labour relations boards have recognized that in representing diverse constituencies, unions often must make strategic choices. For example, unions may have to select some grievances to pursue while abandoning others, or may decide to proceed with a grievance only if they feel they have a reasonable chance of winning. Labour relations boards have acknowledged that evidence of such decisions being made is not in and of itself evidence of failure to fairly represent a member (Brown and Beatty, 2007). Thus, the DFR expectation does not, for example, grant union members the automatic right to have their grievances accepted, or to have their grievances carried as far as required for resolution. Nevertheless, it has also been widely established that dealings between unions and their members must follow the principles of natural justice. As such, to uphold the DFR expectation, union practices must include such factors as giving sufficient notice for preparation for meetings, and allowing union members to participate in proceedings that affect them (Arthurs, 1981). Arthurs (1981: 143-4) contends that such expectations “[threaten] one of the very fundaments of collective bargaining…[undermining] the trade union’s right to behave authoritatively and [diminishing] the possibility of maintaining an informal, expedited means of settling problems”. However, it could also be argued that the DFR expectation is one of the few regulatory mechanisms that permit the individual rank-and-file union member (as opposed to the collective membership) to hold his or her union accountable for its performance. The existence of DFR legislation also ensures that the individual member has an external recourse in those situations where the union does indeed act unfairly.

A more detailed definition of the DFR expectation has also emerged through labour relations boards’ decisions exploring what exactly is meant by “fair representation”. In most Canadian jurisdictions, “fair representation” includes three components: conduct that is not arbitrary, conduct that is not in bad faith, and conduct that is not discriminatory (Adams, 1985). “Arbitrary” union behaviour has been described as including, for example, carelessness in administering the collective agreement, not giving serious consideration to a matter in dispute, or showing hostility to a grievor (Adams, 1985). “Bad faith” may include conduct motivated by revenge, prior hostility, or lack of honesty, and “discrimination” may be defined either as behaviour that contradicts the relevant human rights legislation, or as behaviour that unduly affects the interests of certain types of union members (Adams, 1985).

Literature Review

Previous research involving the duty of fair representation has focused primarily on its practical implications for the behavior of a union. It has been recognized that it is important for union members to have access to a mechanism to hold the union accountable for its performance, especially when “majoritarianism”—running the union on the principle of majority rule—can result in unfair discrimination against a minority of members (Harper and Lupu, 1985). However, it has also been acknowledged that it is often extremely difficult for union members to succeed in proving unfair treatment, even when their claims are merited. Courts and labour boards are reluctant to undermine union democracy by intervening in internal union affairs, and, in situations such as grievance handling, any malicious intent by union officials in handling the grievance can easily be disguised as simple negligence (Goldberg, 2000). It has also been noted that in situations involving large-scale changes to the employer, such as downsizing or mergers, “in many cases the union is simply caught between two opposing interests—those of two sets of members, or those of an individual versus those of the union as an institution” (Stephens, 1993: 696). In such situations, the union may be the subject of DFR complaints not because it failed to represent its members fairly, but simply because it was not able to satisfy some or all of its members’ expectations.

Despite the development and expansion of the DFR expectation in Canada, there has been relatively little research investigating the particulars of Canadian DFR cases. Bentham (1991) indicates that DFR-related decisions by Canadian labour relations boards initially applied DFR only to the context of collective agreement administration, but in some jurisdictions, the DFR expectation has now expanded to encompass other areas of union activity, such as negotiations of collective agreements. This places a larger DFR responsibility on unions, since the DFR is now expected to be considered in a broader range of forms of member representation. Lynk (2002) adds that despite this expanded range of responsibility, the rate of success of DFR complaints across Canada has remained low, which he attributes to “the modest standard of representation that the law has imposed, and the generally satisfactory quality of the work that unions perform on behalf of the employees they represent” (p. 23).

The largest quantitative study of Canadian DFR cases (Knight, 1987a) addressed the possibility that DFR complaints are filed for tactical purposes. This study analyzed DFR complaints in British Columbia from 1975 to 1983 at two levels: all complaints filed with the British Columbia Labour Relations Board during that period, and all complaints involving the conduct of a specific union (the twelve locals belonging to the BC council of the International Woodworkers of America). Knight found that a pattern of tactical activity was apparent within the DFR complaints relating to the individual union. Some locals were “high-complaint” locals but also had higher rejection rates for complaints, indicating that members knew their complaints were without merit but might file them simply to annoy the union leadership. Knight also found that at both levels, men filed more DFR complaints than women during the period of analysis, but women’s complaints were more likely to be found to establish a prima facie case against the union and thus were less likely to be rejected for that reason.

In a subsequent study, Knight (1987b) surveyed 88 British Columbia union staff members to examine the impact of DFR expectations on grievance handling. The survey responses indicated that most staff who handled grievances were aware of the potential for DFR complaints, and ensured that they undertook actions (e.g. written documentation of decisions) that would strengthen the union’s position if a DFR complaint were to occur. This finding was reinforced by the results of another British Columbia-based study (Bemmels and Lau, 2001), which indicated that when union leaders had a higher level of concern about potential DFR complaints during the grievance handling process, they were more satisfied with the grievance procedure in general, suggesting the same DFR-related procedural caution indicated by the respondents in Knight’s study. However, many respondents in Knight’s study also indicated that DFR complaints were often filed for frivolous or vexatious reasons, and that dealing with these complaints placed a possibly unnecessary burden on the union’s resources.

The relatively small amount of research on DFR in the Canadian context means that there is little information available to indicate what characterizes DFR complaints in Canada. There has been little investigation of such issues as whether certain occupations or industries generate more DFR complaints, or to what extent legal counsel become involved in DFR proceedings (the involvement of counsel has been suggested as an influence on the outcome of other labour relations proceedings, such as arbitrations [Harcourt, 2000]). Analyses of the particulars of DFR cases could be of great value to many parties in the industrial relations system: for example, unions wishing to identify practices most likely to generate DFR complaints; legislators or labour relations board members concerned with the effectiveness of existing DFR legislation; or union members wanting to know what factors may affect their own possibility of success in filing a DFR complaint. Thus, the study reported herein examines a set of DFR complaints to determine the more common characteristics of successful and unsuccessful DFR complaints.

The Duty of Fair Representation in British Columbia

As the analysis in this paper only uses DFR-related data from British Columbia, it is important to briefly review British Columbia legislation and practice in this area, in order to understand the legal and procedural context for the cases analyzed. Currently, the duty of fair representation is enshrined in Section 12(1) of the British Columbia Labour Relations Code, which reads:

12(1) A trade union or council of trade unions shall not act in a manner that is arbitrary, discriminatory or in bad faith

in representing any of the employees in an appropriate bargaining unit, or

in the referral of persons to employment whether the employees or persons are members of the trade union or a constituent union of the council of trade unions.

Section 12(2) of the Code states that Section 12(1) is not violated if a union enters into an agreement with an employer to hire certain union members by name, to give hiring preference to union members in a particular geographic area, or to hire specific individuals to perform supervisory duties.

A complainant making a Section 12 complaint to the British Columbia Labour Relations Board (BCLRB) must complete and file a complaint form, available online, along with a $100 fee (British Columbia Labour Relations Board, 2007). The BCLRB website provides an information bulletin and a practice guideline, both of which explain the process of filing a Section 12 complaint and the Board’s procedure in dealing with the complaint (British Columbia Labour Relations Board, 2001, 2009). Among other information, these documents explain the definitions of “arbitrary”, “discriminatory” and “bad faith”, and also explain that the applicant must have satisfied any available internal union procedures, such as filing a grievance or appealing a union decision, before making a Section 12 complaint.

The BCLRB also identifies several key decisions involving the application of Section 12 (British Columbia Labour Relations Board, 2007, 2009). The board points to the Judd case (James W.D. Judd, BCLRB No. B63/2003) as an example of a case describing the general nature of union representation and the standards of behaviour a union is expected to meet in cases involving the duty of fair representation. The Rayonier decision (Rayonier Canada (B.C.) Ltd., BCLRB No. 40/75 [1975]), established the three components of “fair representation” as non-arbitrary behaviour, non-discrimination, and acting in good faith. Complainants must file cases “without excessive delay” or with a “persuasive explanation” for the delay (Joe Frank, BCLRB No. 236/99 and Andre Henri, BCLRB No. B76/00). The BCLRB will not proceed with cases where the complainant has not established a prima facie case that a violation of Section 12 has occurred (Terry Norris, BCLRB No. B156/94). The BCLRB also does not expect that a union be correct in the decision that it makes; instead it expects that unions have “conducted an adequate expectation and made a reasoned decision” (Donato Franco, BCLRB No. B90/94). Unions are empowered to agree with the employer on the interpretation of the collective agreement (Marko Bosnjak, IRC No. C221/89); to agree with the employer to modify the terms of a collective agreement (Peter Blackburn, BCLRB No. B180/84); or to reach a grievance settlement with the employer (Marie Ellison, IRC No. C38/92). Unions have the right to pursue a grievance on behalf of one member if the outcome of the grievance may negatively affect another member (Cindy Chan Piper, IRC No. C245/92), and to trade off the interests of one constituent group against another in collective bargaining (Mervin Klaudit, BCLRB No. B85/93).

The BCLRB’s own data on recent complaints under Section 12 gives some idea of the disposition of these complaints (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Duty of Fair Representation Complaints in British Columbia, 2001-2005

Data drawn from British Columbia Labour Relations Board Annual Reports, 2002-2005.

a “Dismissed” includes complaints that were investigated but were dismissed because no prima facie case was found. The number of cases dismissed for this reason is 37 (49.3% of dismissed complaints) in 2001; 29 (32.9%) in 2002; 69 (65.1%) in 2003; 32 (45%) in 2004; and 17 (40.4%) in 2005.

Several general observations can be made based on the information in Table 1. First, the number of complaints under Section 12 has gradually declined over the five years for which the most recent data are available. This decline has occurred both in absolute numbers and also as a percentage of the overall yearly number of cases filed with the BCLRB. The rate at which Section 12 complaints were granted (“granted” meaning the complaint was decided in favour of the complainant) varies quite widely, but never exceeds 9% in any year, indicating that DFR complainants in British Columbia generally are not successful in having their complaints upheld.

Methodology

Sample

The DFR cases included in this analysis are drawn from British Columbia Labour Relations Board (BCLRB) decisions in 2000, 2002, 2004, and 2006. This timeframe was chosen for ease of access to data, as all BCLRB decisions from 2000 to the present are available on the BCLRB website. Four years’ worth of data were chosen from the seven complete years for which decisions were available, since resource constraints made it difficult to analyze every year’s decisions. Selecting data from even-numbered years randomized the sample, while also including periods representing different levels of activity for cases involving Section 12.

Section 12 cases were identified by reviewing the alphabetized list of decisions for each year selected for analysis; listing the case numbers for each case where the named plaintiff was an individual or group of individuals; and then examining the posted decision for each identified case to determine if the case involved a complaint under Section 12. The cases that were excluded from analysis involved, for example, requests to grant leaves of reconsideration for arbitration awards; requests for religious exemptions from union dues; and complaints from individual union members involving other sections of the Labour Relations Code.

Data Collection

For each decision that was included in the analysis, the following information was recorded on a standardized form:

the name of the complainant;

the name of the respondent union;

the name of the respondent employer;

the nature of the complaint (the issue involved);

whether the complaint involved arbitrary behaviour, bad faith behaviour, or discrimination;

a brief summary of the specifics of the complaint and the events leading to the complaint being filed;

the decision on the complaint;

the reason(s) for the decision;

the gender of the complainant;

whether the complainant, the union, or the employer were represented by counsel.

These data were then coded and entered into an SPSS file. The only data that were not coded were the summaries of the complaints and the related events, simply because this information varied widely between decisions and was difficult to capture numerically without creating an unwieldy number of coding categories. These data were, however, retained for qualitative review. The coding for employers was based on the type of industry their organization belonged to, using the industry classification system of the National Occupational Classification (NOC) employed by Statistics Canada for labour market data analysis. This form of coding was selected so that trends of Section 12 cases across industries would be more obvious, rather than unduly narrowing the analysis to focus on specific employers.

The analysis of the data consisted of calculating and comparing frequencies and percentages across data categories. As Table 1 indicates, in most years in British Columbia, there is such a large discrepancy between the numbers of “successful” and “unsuccessful” cases that conducting statistical analyses such as correlations, T-tests, or regressions would not produce meaningful results. As such, and given the exploratory nature of this study, the results presented below are primarily intended to identify and compare the characteristics of the analyzed cases.

Results

The analysis included 138 cases. Of these cases, 130 were dismissed (i.e. the complaint was not upheld) and eight resulted in decisions in favour of the complainant, representing an overall success rate of 6.15%. Men filed 86 (62.3%) of the complaints, women filed 33 (23.9%) of the complaints, and 19 complaints (13.8%) were filed by more than one complainant—nine with both male and female complainants, seven with multiple female complainants, and three with multiple male complainants. Of the eight cases in which the complaint was upheld, five (62.5%) were filed by men and three (37.5%) were filed by women. None of the complaints that were upheld involved multiple complainants. There were no major differences by gender in the types of complaints filed or the industries involved in the complaints.

The unions that had the most complaints filed against them were the Canadian Union of Public Employees (17 cases, representing 12.3% of the total number of cases), the B.C. Government and Service Employees’ Union and the International Woodworkers of America (IWA) (each involved in 12 cases, representing 8.7% of the total number of cases) and the Teamsters (11 cases, representing 8% of the total number of cases). During the period covered by the analysis, the IWA merged with the United Steelworkers of America, so some of the seven cases involving the steelworkers’ union might have involved workplaces that were formerly certified by the IWA. Since all of these unions have large numbers of members and represent workers in a variety of occupations and workplaces, it is not surprising that they would be named more often in complaints involving Section 12, simply because these unions must manage more relationships with more members in differing circumstances.

The industries that were involved in the most complaints were manufacturing (23 cases, or 16.7% of the total), health care and social assistance (17 cases, or 12.3% of the total), public administration (16 cases, or 11.6% of the total), educational services (16 cases), and construction (14 cases, or 10.1% of the total). Again, these industries include a wide range of employers and different types of work, including workers that frequently move between different projects or contracts, so it is likely that work-related complaints may be more prevalent in these industries. Also, the latter part of the period covered by the analysis includes a time when the British Columbia government was undertaking widespread reorganization of the provincial health-care system. This may partially explain the number of complaints involving public administration and health care or social assistance.

The most common issues resulting in complaints under Section 12, and the frequency of allegations of the specific behaviour which resulted in the complaint, are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 2

Basis for Section 12 Complaints

N = 138

a Includes, e.g., shift changes; changes in work location; changes in job duties.

b Includes, e.g., manner in which member’s complaint was handled; decision made by union staff or internal union committee.

As indicated by the data in Table 2, the union’s alleged failure to pursue a termination-related grievance was by far the most common type of Section 12 complaint. The next most common types of complaints involved the union’s alleged failure to pursue a grievance related to changes in the worker’s job, and alleged poor behaviour by the union in handling a grievance.

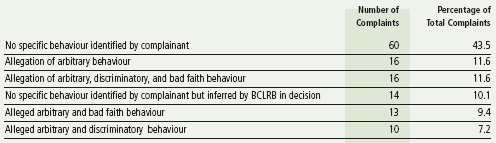

TABLE 3

Frequency of Allegations of Arbitrary, Discriminatory, or Bad Faith Union Behaviour, Section 12 Complaints

The data in Table 3 indicate that nearly half of the Section 12 complaints in the sample did not specifically name the type of behaviour that violated the duty of fair representation. This is somewhat surprising, given that the wording of Section 12 clearly identifies the three grounds on which a union can be found to have not fulfilled its duty of fair representation. When a specific type of behaviour was named, it was most likely to be arbitrary behaviour alone, or arbitrary, discriminatory and bad faith behaviour in combination. In approximately 10% of the cases analyzed, no specific behaviour was identified by the complainant, but the BCLRB member hearing the case inferred the behaviour in making their decision. This was usually accomplished by comparing the case facts to each of the three types of behaviour, and determining whether the case facts indicated that a specific type of behaviour had occurred.

The next direction of analysis was to identify the most common reasons for the BCLRB to dismiss a Section 12 complaint. Table 4 summarizes these findings. There is no single overwhelmingly common reason for dismissal, but the reason occurring most frequently was the determination that the union adequately investigated the situation and made a reasoned decision based on the results of that investigation. This reason tended to occur in cases where the complainant alleged that the union had abandoned a grievance, or had refused to file a grievance on the basis that the grievance had a limited chance of being successful. The wording of Section 12 does not specify a time limit within which Section 12 complaints must be filed, but the information which the BCLRB makes available on its website states: “[T]he complaint must be filed within a reasonable time: if it is filed more than three months after the conduct complained of, it must set out the reasons for the delay (i.e., why it took so long). If there is more than three months’ delay and the reasons for the delay are not provided, or if those reasons are not compelling, then the complaint may be dismissed for unreasonable delay. Note: if the delay is more than one year, the complaint will generally be dismissed unless very compelling reasons for the delay are provided” (British Columbia Labour Relations Board, 2009: 19).

TABLE 4

Most Common Reasons for Dismissal of Section 12 Complaints

N = 138

a Complaint was filed too long after events in question, and/or no adequate explanation was provided for the delay in filing the complaint.

b Part or all of the dispute is currently being adjudicated elsewhere (e.g. grievance still in progress, BC Human Rights Tribunal complaint, civil or criminal court case), and/or complainant has access to other methods of resolution that have not yet been utilized (e.g. internal union appeal process).

The analysis also examined the characteristics of the eight Section 12 complaints that were upheld. Although these cases are a very small percentage of the overall number of cases included in the analysis, they are still worthy of examination on their own to see if there are any distinctive characteristics that emerge in comparison to the cases where the complaints were not upheld. Five of these cases involved male complainants and three involved female complainants. Four of these complaints involved the construction industry, and two involved health care and social assistance. Five of the eight complaints involved a union’s alleged failure to pursue a grievance related to dismissal, and one each involved a failure to pursue a grievance related to pay, alleged problems with internal union processes, and an alleged failure to pursue a grievance related to a change in job. Four of the eight complaints alleged arbitrary behaviour on the union’s part; two complaints did not specify which of the three types of unfair representation the union had engaged in; one involved allegations of arbitrary and discriminatory behaviour; and one alleged arbitrary, discriminatory, and bad faith behaviour.

Finally, the analysis also investigated to what extent counsel were involved in Section 12 complaints. Table 5 shows the frequency with which the parties were represented by counsel in all the cases in the sample. “Counsel” for the employer and for the union was defined to include staff members such as business agents, and lawyers, who may be full-time staff or who may be contracted to represent the party. “Counsel” for the complainant was defined to include lawyers and other types of representatives or advocates (e.g. family members).

TABLE 5

Frequency of Different Types of Representation in Section 12 Complaints

As the data in Table 5 indicate, nearly three-quarters of those filing Section 12 complaints represented themselves in the process. It is also notable that the number of cases in which the employer was not represented is nearly double the number of cases in which the union was not represented. However, as a Section 12 complaint involves a dispute between the union and a union member, it may be that the employer does not play a pivotal role in many of these complaints, and thus does not feel it necessary to invest the time and effort in representation. In four of the eight cases in which the LRB upheld the Section 12 complaints, the complainant represented himself or herself. In all of these eight cases, the union was represented by counsel; however, the employer was either not represented or represented themselves in three of the eight cases.

Discussion of Results

The duty of fair representation, and the legislation embodying it, is clearly intended to ensure that unions can be held accountable for their performance in representing their members. DFR legislation also provides union members with a mechanism to obtain redress if their union acts unfairly in representing them. The data and analysis presented above raise several questions as to whether this mechanism is indeed serving this regulatory function.

The low success rate of DFR complaints in British Columbia raises a number of different questions. First, as Knight (1987) indicates, meritless DFR complaints may be filed simply to punish or harass a union’s leadership. Such complaints may be filed with the complainant being fully aware that the complaint will not succeed; thus, the overall success and failure rates of DFR complaints may not accurately reflect the number of instances in which a union has truly treated its members unfairly, or instances in which a union member has a valid reason to believe that he or she has been treated unfairly. Second, the success rate only represents the outcome of complaints that were actually filed. It is difficult to measure how many times a union member may have felt unfairly treated, or indeed may have been unfairly treated, but did not have the knowledge or resources to file a formal DFR complaint. Previous commentators (e.g. Goldberg, 2000) have noted that it is problematic to assume that DFR complaint rates measure the quality of unions‘ representation of their members, as suggested by some commentators (e.g. Lynk, 2002). Thus, the low success rate represented in these results may suggest that union members in British Columbia are generally satisfied with their representation, but on reflection, it is apparent that this is not a reliable indicator of how well British Columbia unions are fulfilling their DFR responsibilities. It may instead simply reflect that Section 12 complainants in British Columbia generally are unsuccessful, and that the reasons for this lack of success appear to depend on the circumstances of the individual case.

The costs associated with filing a DFR complaint may be a significant factor in determining whether a potential complainant pursues their case. A fee such as the $100 charged by the BCLRB may offset the costs incurred in processing a complaint, but it could also discourage financially challenged individuals from filing a valid complaint. Financial resources may be particularly critical for those without a regular income—and, as the data above show, nearly 35% of Section 12 complaints in British Columbia involve a union’s alleged failure to pursue a grievance related to termination or layoff. Presumably, a union member who has lost their job also has a reduced income, and as a result, may not have a great deal of financial resources to expend on legal proceedings. Thus, again, even if a union has indeed behaved unfairly toward a member, such behaviour does not always result in an actual Section 12 complaint, much less a successful Section 12 complaint, if the member cannot afford to file or pursue a complaint.

Another issue raised by the general lack of success of Section 12 complaints is the apparent misunderstanding on the part of complainants of the purpose and application of Section 12. In looking at the specific details of the 138 cases included in this analysis, and the BCLRB’s assessment of the complaints, a number of themes consistently reoccur. The application of Section 12 does not determine the merits of a grievance; instead, it assesses the union’s behaviour in managing the grievance. A union’s behaviour need not be consistently faultless; instead, the application of Section 12 assesses the totality of a union’s behaviour across time, and the effect of the totality of that behaviour. Also, a union member disagreeing with a union’s decision does not mean the union’s behaviour is arbitrary, discriminatory or in bad faith. The presence of these three themes in multiple decisions across time suggests that perhaps complainants are not being adequately informed about, or do not understand, the purpose of Section 12 or the situations in which it is relevant. As noted, the BCLRB’s website contains easily-located materials that describe how Section 12 complaints are processed and what is expected of complainants. However, many of the BCLRB decisions under Section 12 suggest that this information is not being effectively communicated or understood.

Along similar lines, nearly 44% of the complaints in this analysis did not specifically identify the union’s behaviour as being arbitrary, discriminatory, or in bad faith. This poses a problem for the BCLRB in reaching a decision in these cases, in that the BCLRB is bound by the legislation it administers, and thus must be able to identify the union’s behavior as falling into at least one of these three categories if the complaint is to be upheld. As noted in the analysis, in only 10% of the cases examined did the board member hearing the case take the initiative to infer whether any of the three types of behaviour had occurred, when the complainant did not specify which type of behaviour was being alleged. Thus, complainants who do not specify which type of unfair behaviour they are alleging probably cannot rely on the BCLRB to make that specification for them. The BCLRB’s information directed to Section 12 complainants may need to state more explicitly that complainants should attempt to clearly identify which type of unfair behaviour they are alleging.

However, a counter-argument involving the same issue is whether a labour relations board hearing a DFR complaint should show some flexibility or latitude in applying the “letter of the law”, given that DFR complainants may not be well-versed in legal practice or formal complaint and hearing procedures. It could be argued that labour relations boards traditionally have the discretion to allow broader interpretations or applications of legislation if there are exceptional circumstances affecting the case situation—for example, when a labour relations board ruling on a certification application incorporates the consideration of the “difficult to organize” nature of certain industries or occupations. The point could be made that since DFR complainants may be facing the resources and knowledge of large unions accustomed to labour relations board practices, labour relations boards should perhaps not always hold complainants to the rigid standard of compliance or proof implied by the wording of DFR legislation. The BCLRB shows some evidence of this latitude, in those cases where the complainant did not specify arbitrary, discriminatory, or bad faith behaviour, but the board member hearing the case took the initiative to apply these criteria to the evidence presented. Goldberg (2000) argues that this sort of flexibility is particularly important in cases where there is a history of previous internal conflict between the complainant and the union: “Where a plaintiff, especially in a discharge case, can prove that his or her grievance was mishandled, and that the union officials responsible for it had reacted with hostility towards the plaintiffs’ dissident activities in the past, that should be enough…to draw whatever inferences are appropriate regarding a causal connection between the two. Anything less leaves unscrupulous union leaders with a powerful club to hold over the heads of dissidents and reformers, creating an atmosphere hardly conducive to democratic unionism” (p. 20).

Another issue raised by the data is the effect of involvement of counsel in the process. The complainant’s representation by counsel does not seem to affect whether a complaint is successful or not. But it is also worth considering the unions that are the most frequent targets of the Section 12 complaints in this sample are large, well-established unions with a great deal of experience in interactions with the BCLRB and with labour relations proceedings in general. Also, unions were represented by counsel in 80% of the cases included in this analysis. Therefore, a union that is a subject of a Section 12 complaint is very likely to file a response to a complaint and to retain representation for the process of the complaint’s adjudication. A complainant who seriously intends to pursue a Section 12 complaint would be well advised to keep in mind the legal resources and experience that the respondent union will likely have access to, and to ensure as much as possible that their own representation will be at a comparable level.

Implications for Future Research

Clearly, the study of DFR legislation and the cases involving DFR complaints is a potentially rich area of future research which could enhance understanding of the relationship between a union and the members it represents, and the functions of union democracy in general. Further research could build on the results presented here in directions such as investigating in more detail the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful DFR complaints. Qualitative forms of data collection, such as interviews with DFR complainants or with union representatives who deal with DFR complaints, would add great value in possibly identifying more intangible factors affecting the initiation and outcome of DFR complaints that may not be captured by more quantitative forms of analysis. Characteristics of DFR complaints could also be assessed on additional dimensions such as across different jurisdictions or across time. Research could also address more closely the impact on DFR complaints of external factors such as employment rates or economic conditions, and whether these may influence union members’ willingness to challenge their unions’ behaviour or decisions, particularly in situations where the members’ employment or working conditions are being affected. And research within specific unions or locals could examine whether the disposition of Section 12 complaints has any lasting effect on union practices; for example, whether a successful complaint motivates a union to change its policies or procedures in order to avoid similar complaints occurring again. The duty of fair representation, particularly in the Canadian context, has been the subject of relatively little research to date, and it offers much potential for relevant research in the future.

Appendices

Note biographique

Fiona A. E. McQuarrie

Fiona A. E. McQuarrie is Professor at the Department of Business Administration, University of the Fraser Valley, Abbotsford, British Columbia.

References

- Adams, G.W. 1985. Canadian Labour Law: A Comprehensive Text. Aurora, Ont.: Canada Law Book.

- Arthurs, H.W. 1981. Labour Law and Industrial Relations in Canada. Scarborough, Ont.: Butterworths.

- Bemmels, B. and D.C. Lau. 2001. “Local Union Leaders’ Satisfaction with Grievance Procedures.” Journal of Labor Research, 22 (3), 653-668.

- Bentham, K.J. 1991. The Duty of Fair Representation in the Negotiation of Collective Agreements. Kingston, Ont.: Industrial Relations Centre, Queen’s University.

- British Columbia Labour Relations Board. 2001. Duty of Fair Representation: What Does It Mean? <http://www.lrb.bc.ca/guidelines/representation.htm> (retrieved October 9, 2007).

- British Columbia Labour Relations Board. 2003. Form 12 (Duty of Fair Representation Complaints [Section 12(1)]). <http://www.lrb.bc.ca/forms> (retrieved January 11, 2008).

- British Columbia Labour Relations Board. 2007. Summary of Key Section 12 Decisions. <http://www.lrb.bc.ca/bulletins/summary.htm> (retrieved October 9, 2007).

- British Columbia Labour Relations Board. 2009. Section 12 Guide. <http://www.lrb.bc.ca/bulletins/section%2012%20guide.pdf> (retrieved November 9, 2009).

- Brown, D.J.M. and D.M. Beatty. 2007. Canadian Labour Arbitration. 4th ed. Aurora, Ont.: Canada Law Book.

- Goldberg, M.J. 2000. “An Overview and Assessment of the Law Regulating Internal Union Affairs.” Journal of Labor Research, 21 (1), 15-36.

- Harcourt, M. 2000. “How Attorney Representation and Adjudication Affect Canadian Arbitration and Labour Relations Board Decisions.” Journal of Labor Research, 21 (1), 149-159.

- Harper, M.C. and I.C. Lupu. 1985. “Fair Representation as Equal Protection.” Harvard Law Review, 98 (6), 1211-1283.

- Knight, T.R. 1987a. “Tactical Use of the Union’s Duty of Fair Representation: An Empirical Analysis.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 40 (2), 180-194.

- Knight, T.R. 1987b. “The Role of the Duty of Fair Representation in Union Grievance Decisions.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 42 (4), 716-736.

- Lynk, M. 2002. “Union Democracy and the Law in Canada.” Just Labour, 1 (1), 16-30.

- Stephens. E.C. 1993. “The Union’s Duty of Fair Representation: Current Examination and Interpretation of Standards.” Labor Law Journal, 44 (1), 685-696.

List of tables

TABLE 1

Duty of Fair Representation Complaints in British Columbia, 2001-2005

Data drawn from British Columbia Labour Relations Board Annual Reports, 2002-2005.

a “Dismissed” includes complaints that were investigated but were dismissed because no prima facie case was found. The number of cases dismissed for this reason is 37 (49.3% of dismissed complaints) in 2001; 29 (32.9%) in 2002; 69 (65.1%) in 2003; 32 (45%) in 2004; and 17 (40.4%) in 2005.

TABLE 2

Basis for Section 12 Complaints

TABLE 3

Frequency of Allegations of Arbitrary, Discriminatory, or Bad Faith Union Behaviour, Section 12 Complaints

TABLE 4

Most Common Reasons for Dismissal of Section 12 Complaints

N = 138

a Complaint was filed too long after events in question, and/or no adequate explanation was provided for the delay in filing the complaint.

b Part or all of the dispute is currently being adjudicated elsewhere (e.g. grievance still in progress, BC Human Rights Tribunal complaint, civil or criminal court case), and/or complainant has access to other methods of resolution that have not yet been utilized (e.g. internal union appeal process).

TABLE 5

Frequency of Different Types of Representation in Section 12 Complaints

10.7202/050360ar

10.7202/050360ar