Abstracts

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to examine the effects of working conditions in part-time and casual work on worker stress and the consequences for their workplaces. Data were collected through interviews with occupational health and safety representatives, and focus groups and interviews with workers in retail trade. Results show that job insecurity, short- and split-shifts, unpredictability of hours, low wages and benefits in part-time and casual jobs in retail sector, and the need to juggle multiple jobs to earn a living wage contribute to stress and workplace problems of absenteeism, high turnover and workplace conflicts. Gendered work environments and work-personal life conflicts also contribute to stress affecting the workplace. Equitable treatment of part-time and casual workers, treating workers with respect and dignity, and creating a gender-neutral, safe and healthy work environment can help decrease stress, and in turn, can lead to positive workplace outcomes for retail workers.

Résumé

On en sait peu au sujet de la santé occupationnelle des travailleurs occasionnels ou à temps partiel concernant le stress et ses effets sur les lieux de travail. Cet essai analyse les conditions de travail chez les salariés occasionnels ou à temps partiel dans le commerce de détail dans un secteur urbain du sud de l’Ontario. Plus précisément, il se centre sur le stress de ce groupe particulier de travailleurs, les facteurs qui y contribuent et ses conséquences organisationnelles.

Dans cette étude, le travail à temps partiel consiste en un travail qui dure généralement moins de 30 heures par semaine sur une base régulière. Ceux qui sont employés sur appel et qui n’ont aucun horaire de travail préétabli sont qualifiés de salariés occasionnels. Le stress comprend la manifestation d’une variété de problèmes physiques de l’ordre de la fatigue, de l’épuisement professionnel, des maux de tête, de l’irritabilité et de l’anxiété. Le commerce de détail comprend ceux de l’alimentation, du vêtement et des marchandises en général et les travailleurs sont les employés sur la ligne de front.

Au moment de la restructuration du secteur du commerce au détail au début des années 1990, le travail occasionnel et à temps partiel est devenu la norme. Depuis ce temps, les emplois sont surtout caractérisés par des quarts de travail courts et fractionnés, des salaires et avantages sociaux relativement bas, l’absence de sécurité d’emploi et très peu ou presque pas de formation. La main-d’oeuvre dans ce secteur se recrute en grande partie chez des femmes mariées d’âge moyen, des mères célibataires et de jeunes travailleurs, tous cherchant un certain équilibre entre leur travail et les responsabilités personnelles et familiales. De nombreux emplois dans ce secteur exigent un effort physique lourd, sous des conditions extrêmes, dans des milieux contraignants, tant au plan physique qu’émotif.

Nous soutenons dans cet essai que les conditions de travail dans les emplois à temps partiel et occasionnels, que les milieux de travail sexués dans le secteur du commerce de détail, que les caractéristiques des travailleurs et que les facteurs physiques liés au travail, associés aux responsabilités personnelles, contribuent au niveau de stress qui, à son tour, entraîne un taux de roulement et d’absentéisme élevé et une propension à créer des conflits sur les lieux de travail.

Nous présentons un modèle d’analyse qui englobe tous ces facteurs. Nous avons fait appel à une méthodologie d’ordre qualitatif, comportant des entrevues semi-structurées avec des représentants syndicaux et des travailleurs ainsi que des rencontres avec des groupes témoins de travailleurs. Tous les résultats analysés proviennent des comptes-rendus faits par les travailleurs eux-mêmes. Huit représentants en santé et sécurité au travail du Syndicat international des travailleurs unis de l’alimentation et du commerce ont participé à cette étude.

Ces représentants en santé et sécurité ont souligné le fait de tenter de concilier plusieurs emplois à temps partiel ou occasionnels, les taux faibles de salaire, le faible niveau de sécurité d’emploi, les quarts de travail courts et scindés, les horaires de travail imprévisibles et irréguliers, l’absence de formation professionnelle et de possibilités d’avancement sont autant de facteurs qui viennent alimenter le stress de ces travailleurs. Ils ont aussi constaté que le travail féminin et l’environnement physique de travail dans le secteur ajoutaient au stress.

Les représentants ont aussi analysé la façon dont la charge physique de travail conduit à l’épuisement, aux migraines, aux maux de tête. Ils ont constaté un niveau plus élevé d’absentéisme et de roulement et la présence de conflits sur les lieux de travail. Les observations faites chez les travailleurs du secteur ont révélé que les heures irrégulières de travail et la difficulté de planifier autres choses à l’intérieur de ces heures devenaient des sources importantes de stress, plus particulièrement chez les femmes et les hommes qui avaient une famille. Les enjeux touchant l’ancienneté, les faibles salaires, l’absence d’avantages sociaux, le travail posté, la divulgation des horaires de travail à courte échéance, les assignations de travail fractionnées et brèves contribuaient également au stress. Le statut de travailleur à temps partiel et l’absence de sécurité d’emploi qui en découle occasionnaient un stress additionnel. Enfin, les facteurs physiques de travail, les conditions minables dans le secteur du commerce de détail et les milieux de travail à forte densité féminine aggravaient le stress.

Presque tous les participants ont vécu une expérience de stress lié au travail. Ils étaient conscients des niveaux élevés d’absentéisme et de roulement et de la fréquence élevée de conflit qui en résultait sur les lieux de travail. Les recommandations fondées sur ces résultats en vue de réduire l’incidence du lieu de travail sur le stress comprennent le traitement équitable de ces travailleurs qui soit comparable à celui de leurs collègues à plein temps, l’offre de conditions de travail saines et sécuritaires et le traitement de ces travailleurs avec respect et dignité.

Resumen

El propósito de este artículo es de examinar los efectos de las condiciones de trabajo de los empleos a tiempo parcial y ocasional sobre el estrés ocupacional y las consecuencias para sus respectivos lugares de trabajo. Los datos fueron recopilados a través de entrevistas con representantes de salud y seguridad ocupacional y de focus groups y entrevistas con trabajadores del comercio de detalle. Los resultados muestran que la inseguridad de empleo, los turnos de trabajo cortos y escindidos, los horarios impredecibles, los bajos salarios y pocos beneficios de los empleos a tiempo parcial y ocasional en el comercio de detalle y la necesidad de juntar múltiples empleos para ganar un salario de subsistencia, contribuyen al estrés y al problema de absentismo, al alto movimiento de personal y a los conflictos de trabajo. Los ambientes de trabajo sexistas y los conflictos trabajo – vida personal contribuyen también al estrés que afecta los lugares de trabajo. Un tratamiento equitativo de los trabajadores a tiempo parcial y trabajadores ocasionales, tratar los trabajadores con respeto y dignidad y crear un ambiente de trabajo neutro respecto al género, un medio sano y seguro puede ayudar a disminuir el estrés y, a su turno, conducir a resultados positivos para los trabajadores del sector comercio de detalle.

Article body

Since the late-1970s, part-time and casual employment increased in Canada (Zeytinoglu and Lillevik 2002) in all sectors of the economy including the public sector (Ilcan, O’Connor and Oliver 2003), though the increase has been stabilized in the last few years (Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003). Part-time and casual workers now form a permanent minority share in the labour force. The largest percentage of the part-time and casual workforce is in retail trade (WES Compendium 2001), and most of these workers are women (Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003; Statistics Canada 2002).

A recent review of the literature found precarious employment, particularly casual work, to be associated with negative consequences for occupational health (Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle 2001), and Statistics Canada showed that about 20% of part-time workers are stressed (Williams 2003). With little known about factors affecting stress and related occupational health problems of part-time and casual workers and the consequences for their organizations, further research is urged by many in the field (see for example, Aronsson 2001; Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll 2001; NIOSH 2002; Zeytinoglu et al. 1999).

The purpose of this article is to examine the effects of working conditions in part-time and casual work on worker stress and the consequences for these workplaces. Data were collected through interviews with occupational health and safety union representatives, and from focus groups and interviews with workers in retail trade. The study covers both unionized and nonunion workers. To control some of the external factors that can affect worker stress and organizational outcomes, our study focuses on workers in a single sector (retail trade), a single occupational group (front-line staff), and a small geographical area (an urban area in Southern Ontario).

Definitions of Key Terminologies Used in the Study

In this study, we refer to part-time work as less than full-time hours in a continuous employment contract with a guaranteed number of hours or a somewhat fixed work schedule. This type of schedule is often called “regular” or “permanent part-time” in the literature (Kalleberg 2000; Zeytinoglu 1999). We refer to casual work as employment typically completed on an on-call temporary basis, with no guaranteed hours of work or fixed schedule of work hours. The work can involve full-time or part-time hours, although casual work in retail trade is mostly casual part-time (Zeytinoglu and Crook 1997).

The retail trade sector in Canada contains seven major groups (food, drugs, clothing, furniture, automotive, general merchandise, and other). Retail food stores consisting of supermarkets and grocery stores are the largest trade group in this sector (Zeytinoglu and Crook 1997). In this study, retail trade refers to the food, clothing and general merchandise retail sector, and retail workers are the front-line sales staff, who regularly have direct contact with customers.

The primary occupational health problem examined in this research is stress. Stress has been studied in medical, behavioral and social science research over the past 60 years, but there are wide discrepancies in the literature on how experts define and operationalize stress, and there are numerous scales to measure occupational stress (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll 2001; Di Martino 2000; Fields 2002; Jex 1998). In this study, stress refers to self-reported symptoms occurring as a result of transactions between the individual and the environment (Lazarus 1990). Using the definition from Denton et al. (2002) and Zeytinoglu et al. (2000), symptoms of stress include frequent exhibition of the following (over the preceding six months): exhaustion, burnout, inability to sleep, lack of energy, feeling like there is nothing more to give, wanting to cry, difficulties with concentration, feelings of anger and helplessness, irritability, anxiety, feeling dizzy and feeling a lack of control over one’s life.

Research shows that occupational stress affects organizations through high levels of absenteeism and turnover, and in some cases, through the willingness of employees to engage in conflict with co-workers and supervisors (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll 2001; Lowenberg and Conrad 1998; NIOSH 2002; Wilkins and Beaude 1998). These outcomes are examined in this study. All outcomes discussed are perceived outcomes, as they are measured through self-reports of individuals.

Literature Review

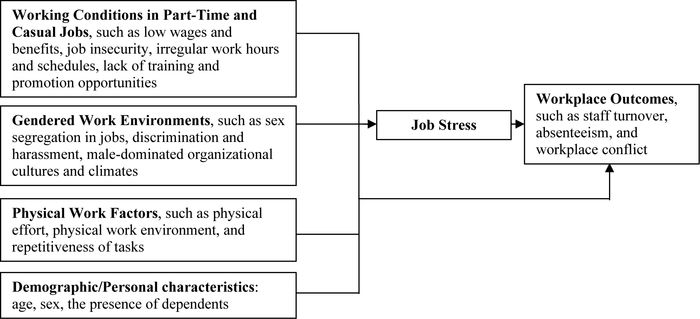

In this section we first examine working conditions in part-time and casual jobs in retail trade, followed by a review of the gendered work environment literature, and the physical work environment factors in the retail trade that affect workers’ stress and workplace outcomes. We include factors that contribute to stress, which are unique to part-time and casual work, such as unpredictability of work hours and schedules, job insecurity and low wages and benefits. Workplace factors that are common to all workers in retail trade include industry restructuring and hazardous work conditions, which impact worker stress and organizational outcomes. Our model, presented in Figure 1, shows the interrelationships among work environment factors with stress acting as a mediator between employment precariousness in the retail environment and workplace outcomes. Our model is influenced by Karasek’s (1979) demand-control model, Ivancevich and Matteson’s (1980) organizational stress model, Marshall and Cooper’s (1979) work environment related stressors and resultant physical and mental health problems model, Davidson and Fielden’s (1999) model of stress and the working woman, and O’Connor et al.’s (1999) feminist participatory model for health promotion research. Since conducting this research, two studies (Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle 2001; Lewchuk et al. 2003) have emerged in the literature conceptualizing precarious work and occupational health consequences.

Figure 1

The Model of Part-time and Casual Work, Worker Stress, and Workplace Outcomes

Working Conditions in Part-time and Casual Jobs in Retail Trade

Part-time and casual work have always existed within retail trade, even before the standard “typical” work of “nine-to-five”, Monday to Friday, permanent, full-time hours was popularized in many other sectors in the mid-1940s (Zeytinoglu 1999). While the structure of many jobs has remained in this model for many years, what has recently changed in the labour market is the high proportion of part-time and temporary jobs that have emerged in retail trade over the last two decades, with employment shifting from a sector characterized largely by full-time jobs to a sector where part-time and casual jobs are now the norm (Hinton, Moruz and Mumford 1999; Kainer 2002; Zeytinoglu and Crook 1997). Presently, in comparison with other occupations and sectors, consumer services occupation and the retail sector have the highest percentage of part-time and casual workers (WES 2001).

In terms of working conditions, part-time and casual work is conceptualized within the context of the dual (segmented) internal labour market theory (Osterman 1984, 1992) with part-time and casual workers employed in the periphery of the workplaces, earning much less on an hourly basis than their full-time permanent counterparts, and having fewer benefits than their full-time co-workers (Atkinson 1987; Beechey and Perkins 1987). Empirical studies throughout the years have consistently showed the marginalized location of part-time and casual workers within the firm in terms of both earnings and benefits (Marshall 2003; Tabi and Langlois 2003; Zeytinoglu and Muteshi 2000a, 2000b) particularly in the retail trade sector (Kainer 2002; Zeytinoglu et al. 2003).

The predominance of the precarious nature of part-time and casual retail employment is fairly recent in retail trade and in the consumer services sector. In the mid-1980s, many front-line customer service jobs in the retail trade were full-time positions; part-time workers were only employed to cover peak periods during the workweek (Hinton, Moruz and Mumford 1999; Zeytinoglu 1991, 1992). The restructuring of the sector started in the early 1990s, and since that time, the number of full-time jobs has consistently declined, with employers making a conscious effort to convert the full-time jobs of those who quit, retired or went on disability pension into part-time and casual jobs (Kainer 2002). Changing economic conditions, corporate restructuring and labour strife undermined the privileged position of unionized workers in large food stores in the retail sector (Kainer 2002). As Kainer discusses, and as we observed, within the last decade, industry-wide labour standards have been eroded, and the majority of unionized workers in the sector no longer receive high wages. Multi-tiered part-time wage structures now segment workers into old and new hires, and many in the latter group earn just above minimum wage with few benefits, despite being unionized. For example, in the region where this study took place, there was a three-month strike in 1993 at Miracle Food Mart stores (owned by the US company A&P), and the strike was not over wage increases but rather job retentions and avoiding wage cuts. In the decade following the strike, experience in these stores suggests that the employer obtained its demands, and was able to push wages downwards. The trend is nowhere near an end with many examples of low wage, no benefit, insecure, marginalized jobs emerging in retail trade as the supermarket giant Wal-Mart pushes workers’ earnings and benefits downward in the US and Canada (see, for example, Goldman and Cleel 2003; Cleel, Iritani and Marshall 2003; Fishman 2003; Lamey 2004; Shepard 2003; Wal-Mart Workers’ Website).

In terms of hours of work and work schedules, Zeytinoglu and Crook’s (1997) study shows that employers are increasingly reducing hours of work provided to workers into shorter and shorter segments of part-time or casual work (while extending store service/operation hours), eliminating rest/meal breaks, and introducing split-shifts. Split-shifts occur when an individual works, for example, in the morning from 8 a.m. to 12 noon and from 5 to 9 p.m. on the same day. Some part-time and casual workers hold multiple jobs, working in split-shifts in different workplaces in order to achieve full-time hours of work (and to earn a livable income), even though this arrangement may increase their work-related expenses of transportation, expand the time lost in commuting from one to the other job, and create difficulties arranging child care and attending to other family responsibilities or schoolwork and activities. Workers in cashier, store clerk or bakery jobs are often scheduled to work in split shifts or work a single 4-5 hour shift per day so that the employer may eliminate the costs associated with giving the legally required lunch and/or rest breaks (Zeytinoglu and Crook 1997). In addition, job insecurity and income insecurity are serious concerns for workers because of the limited hours of work and/or the intermittent scheduling of their work. In many retail workplaces, work schedules for the following week are posted on Thursdays, allowing workers only a few days to arrange their personal life schedules.

As Hinton, Moruz and Mumford (1999) show, for the majority of workers entering the service sector in part-time and casual jobs, there is now less job security and fewer positions with stability than in the past, particularly in non-unionized jobs. Unionized workers generally have more certainty about their employment status because the collective agreement guarantees a minimum number of hours of work per week, or a requirement that temporary/casual jobs become permanent after a defined time period. In terms of training, research suggests that part-time and other non-standard workers often do not receive the same amount and quality of training as their full-time counterparts (Zeytinoglu and Weber 2002), with 8% of part-time workers reporting unmet training needs (Sussman 2002).

Gendered Work Environments and Demographics in Part-Time and Casual Jobs

The negative effects of gendered work environments, which often encompass male-dominated organizational cultures and climates, discrimination against women, harassment, prejudice and sex stereotyping, are all well known to increase stress symptoms of women (Messing 1998; Theobald 2002; Zeytinoglu et al. 1999). Empirical research shows that women suffer from many work-related health problems (Messing and de Grosbois 2001) including occupational stress (Ibrahim et al. 2001; Walters and Denton 1997). In the retail sector, occupational segregation based on sex and the employment status divide between full-time and part-time/casual workers is still prevalent. Management positions, and warehouse and meat cutting jobs are full-time and primarily occupied by males, while front-line staff positions are invariably part-time or casual and are largely filled by women (Kainer 2002; Zeytinoglu and Crook 1997).

In terms of age, the workforce in retail food stores largely consists of middle-aged married women with children, single mothers, and young workers of both genders with no dependents. While middle-aged women and single mothers consider their employment in retail sector as their career (and for many the only employment option), young workers consider their employment in retail sector as jobs necessary to support themselves while studying to pursue other careers (Zeytinoglu 1999; Zeytinoglu and Muteshi 2000a, 2000b). Regardless of gender and age, all of these workers attempt to balance their personal life responsibilities of juggling work and home life, raising children, or completing schoolwork while earning money to support themselves and their dependents.

Physical Work Factors in Retail Trade

Studies show that for all workers, regardless of working full-time, part-time or casually, many jobs in the retail trade require heavy physical effort, may be performed in extreme hot or cold temperatures, or can be in physically or emotionally harassing environments (Hinton, Moruz and Mumford 1999; Messing 1998). The type of tasks typically found in the retail trade sector includes heavy lifting and repetitive motions, mostly in standing positions. Some jobs, such as cashier positions in retail food stores, require a stationary standing position with constant movement of the upper body. These physical work conditions can lead to a variety of debilitating occupational health problems (Messing 1998). Work in a retail store kitchen requires using sharp objects such as knives and other meat cutting machinery, using an oven with constant high heat, using solvents in cooking or cleaning that can ignite easily, breathing solvents that have evaporated to the working area, or working in a constantly cold environment such as in the cold storage or meat cutting area. Customer service jobs entail carrying heavy grocery boxes to delivery rails for customers to pick up, or carrying groceries to customers’ cars, thus repeatedly moving in and out of the building from hot to cold air or vice versa. Work in garden/flower centres has its own physical health problems, as workers are often forced to work in extreme weather conditions, in physically demanding jobs, and with fertilizers and other chemicals whose long-term health effects are just beginning to emerge. Some customer service jobs are prone to violence due to the hours of work and location, such as working alone at night or in early morning hours in isolated areas, or as a result of being responsible for handling money or valuables, such as closing the cash register(s) and depositing the money after work or being in charge of opening and closing the store.

Stress and Organizational Consequences

As presented in our model, stress is a multi-causal outcome of working conditions, gendered work environments, demographic characteristics and physical work factors. The effect of the work environment on stress is well known (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll 2001; Hales and Bernard 1996; Kahn and Byosiere 1992). The unique work environment of part-time and casual employment, in particular, the economic pressure in terms of competition for jobs/contracts, pressure to retain a job, and pressure to earn a livable income, are all conceptualized as factors affecting stress levels of precarious workers (Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle 2001). Stress among part-time and casual workers can also be attributed to the “employment strain” in these jobs due to uncertainty in employment, earnings, scheduling, location of employment and tasks, and the precariousness of the household and demands required to manage employment uncertainty such as time spent in looking for work, time spent travelling between jobs, and conflicts from holding more than one job (Lewchuk et al. 2003).

Stress as an occupational illness can have organizational effects with workers showing higher propensity to leave their jobs, higher rates of absenteeism, and increased tensions in the workplace (Cooper, Dewe and O’Driscoll 2001; Denton et al. 1999; Lowenberg and Conrad 1998; Wilkins and Beaude 1998). A recent study on part-time workers (Buchanan and Koch-Schulte 2000) found that stress in part-time and low-paid employment can have both physical and emotional consequences for employees, ultimately leading to high levels of turnover.

Thus, based on the literature reviewed, we argue that working conditions in part-time and casual jobs, the prevalence of the gendered work environment, demographic characteristics of workers, and the physical work factors in the retail trade contribute to workers’ stress resulting in high turnover and absenteeism, and a higher propensity to engage in workplace conflicts.

Methodology

Research Design

A qualitative research methodology is used in this study. We used semi-structured interviews with union representatives, and semi-structured interviews and focus group sessions with workers. Worker stress in the work environment is analyzed in a holistic manner, and it is largely assessed on what the respondents tell us from their perspectives. Unlike quantitative data, which aims for total objectivity and generalizability through the elimination of extraneous factors and issues while collecting data, a qualitative approach allows researchers to understand the context of the data gathered from the interviews and focus groups. Focus groups are particularly useful in this type of research, as they can produce information that can be enriched by the interactive discussion among group members (Lee 1999). The qualitative approach provides voice to participants, which acknowledges the value of their knowledge and the importance of their perspectives on the issues being discussed, and is also well suited to gathering rich and holistic data to gain a deeper understanding of the issues that participants live and experience daily in their jobs (Lee 1999).

Sample and Data Collection Process

The sample consists of eight Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) representatives of the retail food stores represented by the UFCW Canada and 59 workers in the retail trade. Interviews were initially conducted with union members who are OHS committee representatives so as to develop an understanding of the overall occupational health issues among the workers they represent. We then conducted interviews and focus groups with workers to gather their input on health issues in the workplace. The intermittent and unpredictable schedules of part-time and casual workers make it almost impossible to reach a larger population for focus groups given the available time constraints and resources. A sample size of 59 is a respectable size as long as the themes that come up in the meetings arise on a consistent basis (Lee 1999; Marshall and Rossman 1989), which was the case in our study. For unionized part-time and casual workers, the UFCW Canada members were selected for this study because this union has a large percentage of members in part-time and casual jobs in retail trade. For non-unionized workers, this study focuses on the retail trade by sampling from a variety of retail trade outlets with a high utilization of part-time and casual workers and female workers (as they characterize much of this type of employment in this sector).

Data are collected through interviews and focus groups from retail trade workers in the Hamilton Area (Statistics Canada census metropolitan area), as well as from St. Catharines, and Kitchener/Waterloo in Ontario. Workers became aware of this project through notices posted in their workplaces, from their union steward or occupational health and safety representative, and from telephone contact. The primary contact was the union and the majority of the participants are union members who work in different organizations in the retail trade. A few participants in this project are employed in non-unionized retail establishments in the Hamilton Area. Those participants were contacted through connections of research participants and researchers, using a snowballing sampling approach.

Interview and Discussion Group Questions

During the interviews and focus groups, each participant was given a project information package, then was asked whether they or their members experience stress on the job, which factors contribute to stress, and what they believed were the workplace outcomes of stress (organizational problems). All responses are perceived outcomes measured through self-report of individuals. Table 1 gives the questions used. At the end of each interview and focus group, the participant was asked to fill out a short demographic questionnaire and was given $20 as an honorarium to cover the costs of attending the meeting (such as child care and transportation costs).

Table 1

Questions Asked in Interviews and Focus Groups

Data Analysis

Data analysis of the union representative interviews has been achieved through a content analysis of the transcribed interviews by the research team. Because of the small number of interviews, the data analysis was done by researchers manually. For focus group and interview transcriptions, the first author developed a coding scheme, and the transcriptions were double-coded by the first three authors. This qualitative information was analyzed for common themes and emerging issues, using QSR-N5, a qualitative data analysis software. A report for each theme and sub-theme was prepared, and after thorough readings of the reports, samples were selected for inclusion in this article. Each OHS representative received a code, which appears at the end of the quotes. Each focus group participant and interviewee received a unique, personal identification code, and these are also included at the end of each quote. F refers to a focus group participant, I refers to an individual interview respondent, NU refers to a non-unionized worker and U refers to a union member or those covered by a collective agreement.

Limitations of the Methodology

While there are some limitations of the methodology in a qualitative study such as the one presented here, these limitations can also be a source of strength. First, the data in this article is based on a small number of individuals and thus, the study results cannot be generalized to the population of part-time and casual workers. However, this methodology has permitted an in-depth study of the explored issues. Interviews and focus group methodologies reveal detailed information and explore the interrelationships among several factors affecting an outcome variable in a holistic manner.

Second, sampled workers are largely from unionized environments. Unionized workers were contacted through UFCW Canada locals because of the first author’s previous difficulties in receiving the assistance and support of employers in gaining access to workers in part-time and casual retail trade work. A large amount of research evidence indicates that unionized workers have better pay and benefits and better working conditions than non-unionized workers; therefore, this sample is likely biased towards those who are working in better working conditions than that which actually exists in many workplaces. Sampling from workers represented by the UFCW Canada has benefited the study by reaching individuals from a variety of different workplaces. Including non-unionized workers using a snowballing sampling technique permitted access to individuals in non-unionized settings, which likely have poorer working conditions and are in more marginalized workplaces.

Third, it is important to note that all of these individuals are self-selected in this research, and thus, although these findings are reliable and valid for the participants in this study, further research is needed to corroborate these findings. Although this research does not focus on a single workplace, we argue that the results can be comparable for front-line staff in many other retail workplaces.

Characteristics of the Respondents

OHS Representatives

Eight OHS representatives from unionized food store and retail organizations participated in key informant interviews, seven of which completed demographic questionnaires. The sample consists of mostly married women (5), supporting two to four dependants (young or adult children, elderly parents) in their homes. The majority of the OHS representatives are between the ages of 30 and 55 years. The respondents are, in general, a healthy group of workers who are satisfied with their jobs although they describe their jobs as being rather stressful. The OHS representatives’ employment varied, including such occupations as customer service representative, truck driver/delivery crew member, and photo lab technician. Four members have been working in their occupation for more than twenty years. All of the OHS representatives in our study have prior and/or current experience in part-time and casual employment, and all of these workers have considerable experience working in the retail trade (between seven and 37 years experience). Two representatives hold second jobs in order to obtain full-time work hours or the hours that they would prefer to work. As is typical of work arrangements in the sector, six of the representatives are paid on an hourly basis, and only one receives a salary.

Focus Groups and Worker Interviews Participants

Data were collected from fifty-nine workers who participated in focus groups or interviews, 41 of which are UFCW Canada members (and the rest are non-unionized workers) (see Table 2 for further information on the worker respondents). The majority of worker participants in this project are young females; only three men participated in focus groups. Compared to Statistics Canada data (WES 2001), this sample is representative of the general population of part-time and casual retail trade workers in Canada. All of our study participants work or have worked in part-time or casual jobs in retail establishments such as supermarkets, food stores, clothing stores, garden centres, and beer stores. The majority of our respondents are well educated (and thus overqualified for their positions), young, single, and without dependants. Their self-reported health is at least good, but most indicate that they experience job stress. The tenure in occupation is low for our sample, with most respondents having worked five years or less. The majority are hourly-paid workers, and some work at additional jobs to reach full-time work hours.

Table 2

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group and Interview Participants*

** 3 respondents did not fill out the questionnaire.

** Some answers have fewer than 56 responses because some questionnaires were incomplete.

Results from the OHS Representatives

Sources of Stress

There are a variety of factors that the OHS representatives identified as sources of the stress that part-time and casual workers experience. Included here are juggling multiple jobs (often to complete full-time hours/week), low wages, lack of job security due to the inability of the employer to guarantee hours, short shifts and split shifts, irregular and unpredictable work schedules, and the lack of career development and promotion opportunities offered to part-time and casual workers. The OHS Representatives also noted that demographic characteristics such as gender, and working conditions in retail stores such as the physical work environment tended to add to the stress of part-time and casual workers.

Holding multiple jobs is definitely a source of stress, as seen by the OHS representatives. Stress can compound since the workers are aware that the employers typically frown on this practice. Working odd, irregular and unpredictable hours can be a source of stress, particularly for women. The split-shifts that part-time and casual workers are often faced with can add to this stress, since they make it difficult to manage work and life responsibilities. As one said,

Definitely part-time [is a source of stress] because of the odd hours they work. Our stores are open from 8 in the morning until 10 at night. And so you can be working anywhere from a four-hour to a nine-hour shift on any of those days. And of course it could be that you worked until 10:00 one day and had to be back for 8 in the morning, depending on how your schedule goes. And, that’s a problem. (OH5)

The OHS representatives discussed the fact that part-time and casual workers earn around half of what full-time employees make, for doing exactly the same work, and they are often passed over for promotional opportunities. One of the factors that has contributed to a wider gap in pay between full-time permanent and part-time and casual workers is the method of seniority used in the workplace, which is often tied to the number of hours that are accumulated over a lifetime of working at that one establishment.

Some people have been working [in X workplace] 14-15 years full-time [hours], and some of them even working close to 40 hours a week at a part-time wage. And that again causes a lot of stress, I think, and anxiety within them, because they see everybody else doing the same job they’re doing for triple the pay that they’re getting, and yet they’re not being considered for being hired [for full-time permanent positions]. (OH7)

Job security is a common concern among part-time and casual workers in the retail trade. The OHS representatives identified this factor as a major contributor to stress when downsizing efforts are imminent, especially since seniority tends to be lower for part-time and casual workers as compared to their full-time counterparts.

I think that one of the biggest contributors to [stress] is the uncertainty of the job itself. As the company is downsizing, they’re amalgamating numerous… areas outside of our city into one large organization. And people are inevitably going to lose the job that they have now. Possibly, they may fall down further in seniority lists. And there’s such an uncertainty as to where, what direction the company’s going, and that very much plays a big role in the stress that’s being caused in the individual. (OH7)

Being a female in a retail establishment often also meant that a worker was more likely to fill a part-time and casual position than a male was, which seemed to have inherent disadvantages for the women workers. One OHS representative felt that the women were treated poorly, compared to the men in the organization.

I find it in this store, stress levels are higher in a female employee than a male employee. I really do. I’ve been to all the stores, and I find that in most stores…[males are] in the business with power…have an easier time contacting each other, they have better communication. They’re taken more seriously than women in higher positions in this company. I’ve seen it, I’ve dealt with it. That’s one reason [for the stress]. […] They’re taken more seriously than I find the women in the store [who are] part-time employees and department heads. (OH4)

Physical work environment in retail stores presented an additional source of stress. These problems can range from dangers from poor housekeeping to prolonged exposure to dangerous substances, depending on the position. One OHS representative who works in a grocery store described the potential hazards of the work environment, which she saw as a source of stress.

For the grocery department…we have a lot of cuts…because we have a lot of big knives when it comes to the meat department…sometimes equipment isn’t as guarded as well as what we want it, and so then we’re having to work to get guards [to protect against injury] specially made for it. We’ve got everything from a pharmacy, where they can injure themselves maybe if they slip and fall, to photo labs, which is very much chemicals. […] Physically, one of these things people worry [about]—women worry about is pregnancy: “are these chemicals going to be dangerous for them?” And we usually say, “we don’t know—yet.” […] (OH5)

This same representative also identified that because these workers often deal with the public, they are exposed to customers’ ailments, particularly those who work in the pharmacy.

The OHS representatives’ Views on Stress Experienced by Part-Time and Casual Workers

The OHS representatives explained how, in particular, the physical workload led to stress symptoms of exhaustion, migraines, or headaches for workers in part-time and casual jobs.

[I] definitely [see] being exhausted at the end of the day, because, especially with cashiers who are…just standing. And so by the end of the day, you really are exhausted. And, we just did a scale on how much a cashier is lifting during a four-hour shift, and they lift about 4000 kilos. So that in itself is exhausting. And because of repetitive strains, yes, they very often don’t sleep well at night because of the pain. And, I think everybody, because of the pressures of the job, they need to get more work done in a shorter period of time, they get burnt out. (OH5)

Other symptoms of stress that have been identified by OHS representatives include anger, lack of energy, burnout, difficulties in sleeping at night, irritability, anxiety, and wanting to cry. This OHS representative talks about anxiety attacks that she has seen in her workplace, and how stress overall seems to exacerbate any existing health conditions. “Anxiety, it’s a big one…I’ve seen it happen right on the floor. One worker will have an anxiety attack, like myself. Stomach ulcers, people with irritable bowel syndrome, whenever you’re stressed, that affects it.” (OH4)

The OHS Representatives’ Views on Organizational Effects of Stress

The OHS representatives recognized that as a result of the stress experienced by part-time and casual workers, there were higher levels of absenteeism, turnover, and conflict in the workplace. Stress has led to more people “calling in sick” and not showing up for work. The OHS representatives stated that being in a stressful work environment caused some of the workers to risk their wages and stay at home rather than come into another stressful day at work. The organizational outcomes of stress seemed particularly pronounced for female workers.

I’d say when you’re stressed, you wake up in the morning and you just don’t want to come to work, and when you get here, you just don’t want to do anything. It’s like all of a sudden, you just give up and you don’t care. I’ve seen people take stress leaves, legitimate stress leaves, nervous breakdowns I’ve seen. I never see it in the males, but I see it in the women. (OH4)

As a result of the stress in the workplace, some OHS representatives found that tensions can run high among the workers, resulting in conflict.

There are a lot of problems in the workplace because we’ve got a lot of people who, when they get stressed, they’re on medication, and may or may not be taking their medications for their problems. And it causes a lot of shouting matches, there’s a lot of tension amongst workers when one person is feeling stressed. It’s like they’re trying to take it out on somebody else, and it kind of snowballs down the line. (OH7)

Turnover was discussed as an issue for part-time workers in retail organizations, but the OHS representatives noted that this was largely a result of the nature of part-time jobs and the people who held such jobs, rather than a direct result of stress only. Turnover was often a result of the combination of high workload, low wages, and the fact that many of the part-time positions are filled by people who are returning to school.

Results from Workers

Factors Affecting Stress

There were many reasons listed by our participants as to why they felt stressed at work. Referring to the nature of part-time and casual jobs, participants said that the irregular hours of work and the inability to schedule other commitments in between those hours were causes of stress for them. Over half (31 out of 59) of the participants had difficulties with their work schedules and hours. Also included in the discussion on the nature of part-time and casual jobs were issues related to seniority, the lack of or low benefits they received, shift work, the lack of regularity and continuity in work schedules, the short notice of the work scheduling, split shifts and hours of work. These aspects of non-standard work made it difficult for many to fulfill the needs of their personal and social lives. As one part-time worker explained:

I think working part-time, for me, is stressful. More stressful than a full-time job because of the hours and how they vary. I can work till ten o’clock one night and before I had a car I’d get home by eleven. And then I’d have to work at seven in the morning so I’d have to leave the house at six. So there’s only seven hours there and I have to sleep and come home and wind down from working. And sometimes it’s right in the middle of the day and it takes up your whole day. Most of the time I don’t have the time even to look for another job because the resources aren’t open. (F2U7)

There was also a complaint about the few hours workers are getting per shift.

We used to get forty hours and now, it’s twenty-four hours or under [per week]. And some people are getting five hours [per week]. It was straight eight-hour shifts and now there’s a lot of five-hour shifts…I still have eight-hour shifts, but it’s the constant uncertainty. (F1U1)

Referring to working conditions in part-time and casual jobs, participants explained how working in the same place over a long period of time but only for a few hours per week resulted in low seniority for them. Full-time employees typically passed them by, gained more seniority and consequently earned more money. This inequity contributed to job stress for part-time workers. One said,

I’ve been there for seven years - I’m still not at top rate. Because when I started with X Company I was the first one hired for my department but it was a new store and they take all your names and they spin it around the computer and where you land is where you land in seniority. I was at the bottom, I quit a full-time job for it. I got laid off and then I switched stores, it took me two and a half years to get to twenty hours. And the people who I’ve trained are making way more than me because they got [long] hours right away. (F2U5)

Differences in wages and benefits between full-time and part-time/casual workers were a particular source of stress for part-time and casual workers. In many instances these earned less than their full-time, permanent co-workers, even when performing exactly the same tasks with the same responsibilities. This issue was brought up by half of the respondents (30 of 59), citing it as a source of stress.

Another thing that bothers me is there’s such a pay difference, full-time workers make double what we [part-timers] make. They get uniforms, benefits, paid holidays, lieu days, sick days. They get four or five weeks holidays, they get twenty lieu days, twenty sick days, you know. They change the uniforms like every three years. Well, then we [part-timers] have to pay for them. (F4U18)

Workers also identified the classification of being a “part-time employee” as contributing to stress, especially since part-time workers received no benefits despite working the same hours as full-time employees. One participant said:

I feel the stress with working part-time, especially [working] in the office. I found that was difficult because it was almost like you had a full-time job. I was working almost thirty-nine hours every week. And I was still classified as part-time and I wasn’t getting any benefits out of it. (F3U11)

Having part-time or temporary status often meant for these participants that their jobs were never secure. For some, they constantly worried that they may be fired at any point in time, for any given reason, because they did not see themselves as having a permanent contract with their employers. This factor was particularly pronounced when combined with the seniority and wages issues as discussed above. The following discussion illustrates this point:

…they’re stingy with their money, they’re just going to hire part-time people. They can do the same work as the full-time people. So why pay [full-timers] $24 when these [part-time] people will come in. You know what? I’m sure if you and I really put up a fight they’d say – “you know what? If you don’t like it, get out and we’ll hire someone new”. I don’t really think they care… (F4U19)

Physical work factors in part-time and casual jobs in retail trade were also discussed as resulting in stress. The physical effort in the work environment was a source of stress for 25 of 59 participants. One participant outlines how standing on her feet is very difficult, especially for long periods of time. “…I usually try to make sure to get the second break but sometimes it doesn’t happen…it’s tough because you’re going like maybe three hours without a break, without sitting down. That’s tough.” (F3U15)

Uncomfortable and poor working conditions in retail workplaces provided a significant source of stress. A considerable number of respondents (42 out of 59 respondents) in most of the focus groups and interviews described their workplaces as being hot, cold, dusty, noisy, etc. The poor layout of the work area resulted in a lot of lifting, twisting and bending, and some work environments are very cold because they are located near the door or because the air conditioning is running even if outdoor weather conditions are cold, with some workers’ hands becoming almost frozen from the cold before management did something about the problem.

Being a female part-time or casual worker appeared to be a particular stress for the study participants (mentioned by 27 of 59 participants). They discussed the stereotyped behaviour of their managers and co-workers, such as totally ignoring them at work, or placing them in jobs that they deemed as appropriate for women, or disguising their contributions in producing a service or product to customers. A hardware store worker explained how she was not allowed to home deliver a barbeque that she assembled because she was ‘a girl’ and customers should not see that, and how this discrimination based on her gender created stress for her. Participants discussed how females and males were segregated into certain positions and this created stress among women, particularly when the ‘male jobs’ that they can easily perform, paid up to $6 more per hour, and they were not allowed to work in those jobs simply due to their gender. Often they discussed the effect of their gender and working in part-time and casual jobs as inseparable components of a factor contributing to the management’s and (some) co-workers’ discriminatory behaviour affecting their stress levels such as asking them why a ‘girl’ was sent to deliver the chickens and where were the men to do this job. Needless to say, the tone of the women’s voice in saying ‘the girl’ showed how much they resented being called as a ‘girl’ in their adult age.

Stress seems to be a particular problem for women and for those who have families to take care of. The irregular hours, combined with inconsistent shift schedules, caring for children, running errands and managing the household, can take a toll on female part-time and casual workers. One said,

Our scheduling is really difficult. Maybe a couple of days you get the early shift and then all of a sudden you’ll go to closing shift. […] I’ve got one that goes from 12 to 9 but Friday morning I have to be in there at seven a.m. I mean if you have children at home, that you have to get them ready for school and you don’t drive, and you have to get a bus and you’ve got to make sure that things are done for them before you even get out to work, so for women that have kids at home it can be stressful. And then you’re dealing with your job and you’re only there for five hours. So in that five hours you’re running around. Your day may start at four a.m., but it may not finish until ten or eleven o’clock at night because you’ve had to leave everything because you’ve worked twelve to nine the night before, you didn’t have time to do all your errands, you run home from work and you race around…a full-time job is much easier, it’s more stable, you’d have a nine to five or an eight to four [shift]. (F2U8)

Stress Experienced by Part-Time and Casual Workers

Nearly all of the participants in this study (50 out of 59 participants) said that they experienced symptoms of work-related stress. One participant explained that as a result of stress, she was so ill, that she actually ended up in the hospital. Her doctor told her that she had become severely ill due to stress as a result of overwork. Her symptoms included nausea and depression.

So I went back to the doctor on Monday and she told me I was getting myself so stressed that I was making myself sick. Like I could almost…I feel like I’m going to throw up all the time and everything so she put me on stomach medication and I guess an anti-depressant almost, like a lower dose. Just so I wouldn’t worry about anything and that. And I’ve never felt that way before except I guess I’m trying to save up for a car, I’m trying to work as hard as I can. I’ve come to work sick just because I didn’t want to look like I was irresponsible. Like my head cashier would be like – “no, go home, you’re sick” – and I’d have to tell her – “no, no, I’m going to stay” – you know, and just get through the day. Because I don’t want to be looked upon like – “oh, look she’s a wimp, she’s going home sick” – you know. So finally the next couple of days, I had to give in, I was so sick, I had to go to the hospital. (F9NU37)

Organizational Effects of Stress as Seen by Workers

Interview and focus group participants felt that, in many cases, what they perceived as high levels of absenteeism and turnover were a result of the stress that they experienced on the job. Absenteeism as a workplace outcome was mentioned by many participants in the study (17 out of 59). One focus group participant explained the link between stress and absenteeism in her workplace and said, “There’s a high rate of absenteeism too because…people work so much they get sick.” (F6NU26) Employee turnover was the most discussed organizational outcome in this study; a number of participants (22 out of the 59) identified turnover as an organizational outcome. Though some reasons for turnover are related to the seasonal nature of some jobs, many other reasons mentioned are indirectly related to the stress that the nature of part-time and casual jobs create. Low wages and benefits in part-time and casual jobs, inconsistent hours, lack of promotion opportunities, being overworked, having an undesirable or unglamourous job, and poor treatment of part-time and casual workers by management were reasons that were most often mentioned which caused them stress and prompted them to leave the job. One participant describes how some of her former co-workers became frustrated and angry at work, and how this eventually led them to quit their jobs.

I hear a few of my co-workers saying – “I can’t stand this” – and they’ll tell me about it, an incident that they just experienced. They’ll be [saying] – “I was so close to quitting”. And they’ll have this in their minds for a few months and then finally they do quit…because they’ve just been fed up with the whole environment. (F11U41)

The workers also felt that where workplace stress was high, workplace morale was lower and the work environment was less enjoyable, leading to a higher likelihood of employees being willing to engage in conflict with other workers and with their supervisors and management. A number of participants (17 out of 59) also discussed the willingness to engage in conflict as a manifestation of stress in the work environment. One participant expressed why there is conflict between the part-time staff and the managers in her store: “I think there’s a lot of conflict between workers in our store because all the part-timers, when we’re in together and the managers go on break [without inviting us and leaving the full responsibility to us], there’s resentment.” (F6NU24) The resentment was turning into stress because they were responsible for running the store but they were paid a fraction of managers’ pay, and they were treated as second class people at work. One participant stated that the difficulties that the demands from both workers and managers place on one another lead to stress and workplace conflict.

Well in our department, I think there’s a lot of conflict with the supervisor, just because I think a lot of it has to do with the stress, just because some people want times off or different schedules or things like that and then it’s hard for her to work around everybody, because I mean it’s a large department but there’s not a lot of give and take and I think that’s the problem which makes it even more stressful. (I4U4)

Discussion and Conclusions

In examining part-time and casual work in retail trade, we found the effects of working conditions in part-time and casual work, the gendered work environments and demographic characteristics, and physical work factors contributing to worker stress affecting their workplaces. These outcomes stem primarily from the precariousness in the work environment of part-time and casual workers in retail trade. Scheduling problems such as short shifts and split shifts made it difficult for part-time and casual workers to schedule their work and life responsibilities. The unpredictability of hours, low wages and benefits, and the resulting need to juggle multiple jobs in order to earn a living wage also contributed to stress. The low seniority that these workers have due to their part-time and casual hours and the resulting pay differential between part-time and full-time workers added to the stress. For some workers, especially female non-standard workers, caring for dependants and the conflicts between work and family responsibility demands augmented the stress levels that they experienced. Participants pointed out that women, who were more likely to hold part-time and casual positions, were treated with less respect than the males in their organizations, which exacerbated the stress of these individuals. Work and organizational characteristics such as handling dangerous equipment with no or minimal training and exposure to toxic substances but having no knowledge of possible side effects of those substances caused stress among these part-time and casual workers. Extreme temperatures in the work environment made the work uncomfortable and unhealthy for some workers. Most of these findings were in line with the conceptualizations of the effects of precarious work on workers’ health as discussed by Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle (2001) and Lewchuk et al. (2003), and the gendered work environments and discrimination and harassment of women at work contributing to their stress levels as discussed by Messing (1998), Theobald (2002), and Zeytinoglu et al. (1999), among many others.

There was a wide range of symptoms of stress that were identified by the participants. This included difficulties with sleeping through the night, fatigue, dizziness, headaches or migraines, exhaustion, wanting to cry, having no energy on the job, feeling burnt out, the desire to yell at people, and feeling irritable and tense. In some instances, the stress led to nausea, depression, and anxiety attacks as experienced by the workers in the study. As for the organizational problems of absenteeism, turnover, and workplace conflict, our study showed that they were partially an outcome of part-time and casual work and stress resulting from the characteristics of and working conditions in these jobs. Workers often felt that their employers did not show support to them, by such acts as consistently giving them undesirable shifts (i.e. Friday and Saturday evenings and Sunday mornings), paying them lower wages and benefits than full-time workers, creating superficial barriers between full-time and part-time workers by not allowing the latter group to take training to perform their jobs more easily and efficiently, and threatening to replace these workers if they became assertive about their job. These factors, in turn, seem to lead to stress and lower commitment on the part of part-time and casual workers to their places of employment. Since they feel disposable and less valued than their full-time, permanent counterparts, they are less likely to feel like making a contribution to their team or department, and also feel that no one will miss them if they decide not to show up, or if they quit their jobs. In some cases, the stress that many of the retail workers felt exploded into shouting matches among workers.

The results of this study lead to a number of issues that need to be addressed in the workplace, with respect to improving and maintaining the occupational health of part-time and casual workers, and to lowering levels of absenteeism, turnover, and workplace conflict. Since absenteeism and turnover in these part-time and casual jobs are highly linked to low wages and benefits, employers should rethink how they compensate their employees. Employers should consider the option of compensating employees according to the tasks they perform, as opposed to separating based on full-time versus part-time/casual contract status. Some part-time workers were resentful that they were working alongside full-timers who earned much more than they did for performing the identical job. Many of the participants cited that they felt disposable, as they lack job security, and thus employers may want to evaluate the messages they send to part-time and casual workers. Shifts should be assigned in such a way that split-shifts can be avoided as much as possible, so that part-time and casual workers can adequately juggle their personal and professional responsibilities. In addition, maintaining an overall climate of respect for all workers in a work environment will lead to increased workplace morale. A safe and healthy work environment can also contribute to lower turnover and absenteeism. Management should treat part-time and casual workers equitably and not as disposable resources. Encouraging a respectful, supportive environment for part-time and casual workers in the retail sector can contribute to an improved work environment and decreased organizational problems. What these workers expect, and should receive, is the same type of praise and acknowledgement of good work as shown to full-time workers, and eliminating the gender segregation in many workplaces between these groups of employees would further make part-time and casual workers feel humanized, respected, and valued. These actions, taken together, will contribute to decreased stress, and in turn, to decreased rates of turnover, absenteeism, and conflict in the workplace.

In this study we wanted to give voice to the primarily female workforce in front-line service jobs. These women are one of the most marginalized groups of workers in our society, and their precarious employment conditions and overall poor quality jobs create an environment where they are powerless—neither heard, nor seen—even though they provide services to consumers in the 24-hour, 7-day a week North American economy (Zeytinoglu and Cooke 2004). It is important that such workers have a voice in the occupational health literature because only then, there will be attempts to improve their working conditions.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Status of Women Canada, Policy Research Fund, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. This article is partially based on data collected under a study conducted for the Status of Women Canada. The authors wish to thank Michael J. Fraser, Director, UFCW Canada, Sue Yates, Coordinator for Health and Safety Issues, UFCW Canada, and the UFCW Union Locals involved in this study for their assistance in this research, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

References

- Aronsson, G. 2001. “Editorial: A New Employment Contract.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment& Health, Vol. 27, No. 6, 361–364.

- Atkinson, J. 1987. “Flexibility or Fragmentation? The United Kingdom Labour Market in the Eighties.” Labour and Society, Vol. 12, No. 1, 87–105.

- Beechy, V., and T. Perkins. 1987. A Matter of Hours: Women, Part-time Work and the Labour Market. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Buchanan, R., and S. Koch-Schulte. 2000. Gender on the Line: Technology, Restructuring and the Reorganization of Work in the Call Centre Industry. Status of Women Canada. On-line: www.swc-cc.gc.ca. Accessed April 25, 2001.

- Cleel, N., E. Iritani, and T. Marshall. 2003. “The Wal-Mart Effect.” Los Angeles Times, November 24.

- Cooper, C. L., P. J. Dewe, and M. O’Driscoll. 2001. Organizational Stress: A Review and Critique of Theory, Research, and Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cranford, C. J., L. H. Vosko, and N. Zukewich. 2003. “The Gender of Precarious Employment in Canada.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 58, No. 3, 454–482.

- Davidson, M. J., and S. Fielden. 1999. “Stress and the Working Woman.” Handbook of Gender & Work. G. N. Powell, ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 413–426.

- Denton, M., M. Hajdukowski-Ahmed, M. O’Conner, and I. U. Zeytinoglu. 1999. “Introduction.” Women’s Voices in Health Promotion. M. Denton, M. Hajdukowski-Ahmed, M. O’Conner, and I. U. Zeytinoglu, eds. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1-8.

- Denton, M., I. U. Zeytinoglu, S. Webb, and J. Lian. 2002. “Job Stress and Job Dissatisfaction of Home Care Workers in the Context of Health Care Restructuring.” International Journal of Health Services, Vol. 32, No. 2, 327–357.

- Di Martino, V. 2000. Introduction to the Preparation of Manuals on Occupational Stress. Safe Work, InFocus Programme on Safety and Health at Work and the Environment, ILO. On-line: www.ilo.org. Accessed March 8, 2002.

- Fields, D. L. 2002. Taking the Measure of Work: A Guide to Validated Scales for Organizational Research and Diagnosis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Fishman, C. 2003. “The Wal-Mart you don’t know.” Fast Company, No. 77, 68. http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/77/walmart.html.

- Goldman, A., and N. Cleel. 2003. “Wal-Mart Gives, and Wal-Mart Takes Away.” Los Angeles Times, November 30.

- Hales, T. R., and B. P. Bernard. 1996. “Epidemiology of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders.” Orthopedic Clinics of North America, Vol. 27, No. 4, 679–709.

- Hinton, L., J. Moruz, and C. Mumford. 1999. “A Union Perspective on Emerging Trends in the Workplace.” Changing Work Relationships in Industrialized Economies. I. U. Zeytinoglu, ed. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 171–182.

- Ibrahim, S. A, F. E. Scott, D. C. Cole, H. S. Shannon, and J. Eyles. 2001. “Job-Strain and Self-Reported Health Among Working Women and Men: An Analysis of the 1994/5 Canadian National Population Health Survey.” Women & Health, Vol. 33, No. ½, 105–124.

- Ilcan, S. M., D. M. O’Connor, and M. L. Oliver. 2003. “Contract Governance and the Canadian Public Sector.” Relations Industrielles/ Industrial Relations, Vol. 58, No. 4, 620–643.

- Ivancevich, J. M., and M. T. Matteson. 1980. Stress and Work: A Managerial Perspective. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

- Jex, S. M. 1998. Stress and Job Performance: Theory, Research, and Implications for Managerial Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Kahn, R. L., and P. Byosiere. 1992. “Stress in Organizations.” Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. M. D. Dunnette and L. M. Hough, eds. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 571–650.

- Kainer, J. 2002. Cashing in on Pay Equity? Supermarket Restructuring and Gender Equality. Toronto: Sumach Press.

- Kalleberg, A. L. 2000. “Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-time, Temporary and Contract Work.” Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 26, 341–365.

- Karasek, R. A. 1979. “Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign.” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 24, 285–307.

- Lamey, M. 2004. “Wal-Mart Faces Union Threat.” The Gazette, January 27.

- Lazarus, R. S. 1990. “Theory-Based Stress Measurement.” Psychological Inquiry, Vol. 1, 3–13.

- Lee, T. W. 1999. Using Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lewchuk, W., A. de Wolff, A. King, and M. Polanyi. 2003. “From Job Strain to Employment Strain: Health Effects of Precarious Employment.” Just Labour: A Canadian Journal of Work & Society, Vol. 3, 23–35.

- Lowenberg, G., and K. A. Conrad. 1998. Current Perspectives in Industrial/Organizational Psychology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 1989. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Marshall, J., and C. Cooper. 1979. “Work Experiences of Middle and Senior Managers: The Pressure and Satisfaction.” International Management Review, Vol. 19, 81–96.

- Marshall, K. 2003. “Benefits of the Job.” Perspectives on Labour and Income. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75-001-XIE, Vol. 4, No. 5, 5–12.

- Messing, K. 1998. One-Eyed Science: Occupational Health and Women Workers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Messing, K., and S. de Grosbois. 2001. “Women Workers Confront One-Eyed Science: Building Alliances to Improve Women’s Occupational Health.” Women & Health, Vol. 33, No. ½, 125–141.

- NIOSH. 2002. The Changing Organization of Work and the Safety and Health of Working People: Knowledge Gaps and Research Directions. Cincinnati, OH: NIOSH-Publications Dissemination. Publ. No. 2002–116.

- O’Connor, M., M. Denton, M. Hajdukowski-Ahmed, and I. U. Zeytinoglu. 1999. “A Theoretical Framework on Women’s Health Research.” Women’s Voices in Health Promotion. M. Denton, M. Hajdukowski-Ahmed, M. O’Connor and I. U. Zeytinoglu, eds. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 9–20.

- Osterman, P. 1992. “Internal Labor Markets in a Changing Environment: Models and Evidence.” Research Frontiers in Industrial Relations and Human Resources. D. Lewin, O. Mitchell and P. Sherer, eds. Madison, WI: IRRA Series, 273–308.

- Osterman, P., ed. 1984. Internal Labor Markets. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Quinlan, M., C. Mayhew, and P. Bohle. 2001. “The Global Expansion of Precarious Employment, Work Disorganization, and Consequences for Occupational Health: A Review of Recent Research.” International Journal of Health Services, Vol. 31, No. 2, 335–414.

- Shephard, T. 2003. “Loblaws May Build Superstores.” Toronto Star, July 20.

- Statistics Canada. 2002. Women in Canada: Work Chapter Updates. Catalogue No. 89F0133XIE.

- Sussman, D. 2002. “Barriers to Job-related Training Needs.” Perspectives on Labour and Income. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75-001-XIE, Vol. 4, No. 3, 5–12.

- Tabi, M., and S. Langlois. 2003. “Quality of Jobs Added in 2002.” Perspectives on Labour and Income. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75-001-XIE, Vol. 4, No. 2, 12–16.

- Theobald, S. 2002. “Gendered Bodies: Recruitment, Management, and Occupational Health in Northern Thailand’s Electronic Factories.” Women & Health, Vol. 35, No. 4, 7–26.

- Wal-Mart Workers’ Website. http://www.walmartworkerscanada.com.

- Walters, V., and M. Denton. 1997. “Stress, Depression and Tiredness Among Women: The Social Production and Social Construction of Health.” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, Vol. 31, No. 1, 53–70.

- WES Compendium (Workplace and Employee Survey Compendium). 2001. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 71-585–XI.

- Wilkins, K., and M. Beaude. 1998. “Work Stress and Health.” Health Reports, Vol. 10, No. 3, 47–62.

- Williams, C. 2003. “Sources of Workplace Stress.” Perspectives on Labour and Income. Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75-001-XIE, Vol. 4, No. 6, 5–12.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U. 1991. “A Sectoral Study of Part-Time Workers Covered by Collective Agreements: Why Do Employers Hire Them?” Relations Industrielles/ Industrial Relations, Vol. 46, No. 2, 401–418.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U. 1992. “Reasons for Hiring Part-Time Workers.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 31, No. 3, 489–499.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U. 1999. “Introduction and Overview.” Changing Work Relationships in Industrialized Economies. I. U. Zeytinoglu, ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins, ix–xx.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and M. Crook. 1997. “Women Workers and Working Conditions in Retailing: A Comparative Study of the Situation in a Foreign-Controlled Retail Enterprise and a Nationally Owned Retailer in Canada.” International Labour Organization Working Paper, No. 79. Geneva: ILO.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and J. Muteshi. 2000a. “Gender, Race and Class Dimensions of Non-standard Work.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 55, No. 1, 33–167.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and J. Muteshi. 2000b. “A Critical Review of Flexible Labour: Gender, Race and Class Dimensions of Economic Restructuring.” Resources for Feminist Research, Vol. 27, No. ¾, 97–120.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and W. Lillevik. 2002. “Conceptualizations of and International Experiences with Flexible Work Arrangements.” Flexible Work Arrangements: Conceptualizations and International Experiences. I. U. Zeytinoglu, ed. The Hague, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International, 3–10.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and C. Weber. 2002. “Heterogeneity in the Periphery: An Analysis of Non-Standard Employment Contracts.” Flexible Work Arrangements: Conceptualizations and International Experiences. I. U. Zeytinoglu, ed. The Hague, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International, 13–24.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and G. B. Cooke. 2004. “Who is Working When We are Resting? Weekend Work in Canada.” International Symposium on Working Time, 9th Meeting, Paris, February.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., M. Denton, S. Webb and J. Lian. 2000. “Self-Reported Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Visiting and Office Home Care Workers.” Women & Health, Vol. 31, No. 2/3, 1-35.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., J. Moruz, B. Seaton, and W. Lillevik. 2003. Occupational Health of Women in Non-Standard Employment. Ottawa: Status of Women Canada, Research Directorate, Policy Research.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., M. Denton, M. Hajdukowski-Ahmed, M. O’Connor, and L. Chambers. 1999. “Women’s Work, Women’s Voices: From Invisibility to Visibility.” Women’s Voices in Health Promotion. M. Denton, M. Hajdukowski-Ahmed, M. O’Connor and I. U. Zeytinoglu, eds. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 21-29.

List of figures

Figure 1

The Model of Part-time and Casual Work, Worker Stress, and Workplace Outcomes

List of tables

Table 1

Questions Asked in Interviews and Focus Groups

Table 2

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group and Interview Participants*

10.7202/007495ar

10.7202/007495ar