Abstracts

Abstract

This essay examines the central role of women in modelling Keats’s posthumous reputation during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by focusing on the visual heritage of his narrative poems. While the Pre-Raphaelite’s interest in and well-known renderings of Keats’s poems have been the subject of previous critical attention, many comparable images by women artists have been neglected. This essay analyses a wide variety of paintings, drawings and illustrations based on Keats’s “Isabella; or, the Pot of Basil” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci” by women artists at the turn-of-the-century. This examination of women artists, who were celebrated during their own lifetimes but are now virtually forgotten, culminates in a detailed discussion of Jessie Marion King. Her highly innovative illustrations for Keats’s poetry are not only indicative of the final phase of Pre-Raphaelitism and the distinctive “Glasgow Style;” they also underline the significance of women’s artistic responses to literature during this period.

Article body

Despite remaining largely resistant to women readers during his lifetime, Keats’s poetry became increasingly popular with this sector of the literary market during the nineteenth century, a trend which has, almost without exception, been dismissed as trivial.[1] One of the few examples that is sometimes cited of a Victorian woman’s response to Keats’s poetry is an article of 1870 entitled “The Daintiest of Poets—Keats.” Women were not alone, however, in expressing an appreciation of Keats’s charming “gems of poetry” (66).[2] Moreover, there were many interesting and interested women readers of Keats’s life and work during the mid to late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Among the women who published studies on Keats during this period were: Frances Mary Owen, Dorothy Hewlett, Betty Askwith and, of course, Amy Lowell, whose landmark two-volume biography of Keats, published in 1925, sold out four editions in five days.[3] The prominence of women in the modelling of Keats’s posthumous reputation is equally apparent in the various publications aimed at raising funds for the Keats-Shelley House during the first part of the twentieth century; these included eminent female patrons, actresses, a significant number of female writers, including Amy Lowell, Alice Meynell and Marie Corelli, and a widespread contingent of female painters and illustrators, many of whom will be discussed shortly.[4]

The virtual absence of women from accounts of Keats’s cultural heritage is nowhere more evident than in the artwork inspired by his poetry.[5] Pre-Raphaelite paintings, such as John Everett Millais’s “Isabella and Lorenzo” and William Holman Hunt’s “The Eve of St Agnes,” are widely known, as are John William Waterhouse's and Frank Dicksee’s celebrated versions of “La Belle Dame sans Merci.” In stark contrast, many of the paintings, drawings and illustrations based on Keats’s poetry by women artists are rarely referred to or reproduced. The more famous Pre-Raphaelite images undoubtedly offer inspired and challenging visual renderings of Keats’s narratives; I have privileged these paintings in previous research, largely because of their significant place in Keats’s cultural afterlife and the influence they have exerted over popular perceptions of his poetry.[6] However, working on such celebrated images uncovered a considerable number of virtually unknown images by female artists. Many of these women, and the records of their lives, have almost disappeared from view; their visual renderings of Keats’s poetry are now lost or simply labelled “untraced.” Admittedly, some of these works, as with comparable works by male artists, were produced to meet the demand for sentimental paintings with “poetical tags” in the High Victorian period (Yeldham 150). Yet it can also be argued that such artworks are not only important for seeing the whole “picture” of Keats’s visual heritage, but for tracing the changing fortunes of narrative artwork during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Furthermore, as I hope to demonstrate in this essay, the designs of certain women artists—Jessie Marion King in particular—are indicative of prevailing trends in Keats-based visual representations while, at the same time, retaining a remarkable individuality.

During the High Victorian period, scenes from Keats’s poetry were often produced to cater for a demand in art derived from popular literary sources. Two fin-de-siècle paintings of “Isabella” by women artists that were exhibited in the Royal Academy illustrate this trend.[7] Ella M. Bedford’s 1898 version of Keats’s narrative poem (fig. 1: Ella M. Bedford, “Isabella and the Pot of Basil,” 1898), which has only survived as a rudimentary sketch in Academy Notes, pictures the heroine in strained reverie, wearing a voluminous, patterned gown with a section of her hair angled, somewhat awkwardly, into the basil plant.[8] The original painting is named in Christopher Wood’s Victorian Painters as is Isobel L. Gloag’s painting on this theme, dated 1895 (fig. 2: Isobel L. Gloag, “Isabella and the Pot of Basil,” 1895).[9] Like many of the women artists discussed here, Gloag was highly versatile: she was a consummate portraitist, illustrator and stained glass window designer. Gloag exhibited some nineteen works at the Royal Academy, including an erotically-charged “Rapunzel” and “The Magic Mantle” (also known as “The Enchanted Cloak”), an intriguing painting that shows a woman, who is naked except for a cloak of diaphanous peacock feathers, running from onlookers.[10] Gloag’s “Isabella and the Pot of Basil,” also reproduced in Academy Notes, captures the melancholic gloom that dominates the end of Keats’s poem. The heroine jealously guards her basil plant like the protective hen-bird that Keats describes in stanza 59. Her stare demonstrates, as in the poem, a distracted psychological state that “looked on dead and senseless things,” and cried out to the wandering pilgrims with “melodious chuckle in the strings/ Of her lorn voice.”[11]

Figure 1

Figure 2

Another visual rendering of “Isabella” exhibited at this time is by Henrietta Rae (fig. 3: Henrietta Rae, “Isabella,” 1897). This painting, dated 1897, is also untraced; what remains is a full-page colour reproduction in a biography of the artist.[12] Although not widely known today, Rae emerged as one of the foremost female artists of her day, exhibiting every year at the Royal Academy from the early 1880s onwards; she even overcame entrenched prejudice to win a scholarship at the same institution on her sixth attempt. As well as the evident Pre-Raphaelite tendencies in Rae’s work, the influence of successful classical revival artists, such as Edward Poynter, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Frederick Leighton and George Frederick Watts, can be detected in her version of “Isabella.” The viewer is invited, through the arch that frames the heroine, to observe an intimate scene of mournful longing as Isabella embraces the pot that contains the remains of her lover, Lorenzo. Rae was inspired by Keats’s Florentine tale while on a trip to Italy—as was Holman Hunt some thirty years before—which can be felt in the warm colours, full blooms and view of the sea (providing a contrast with Gloag’s claustrophobic interior). Rae’s biographer describes the painting as “a most successful realization of the subject” and praises its “surpassing beauty” (Fish 99).

Figure 3

Whether or not we appreciate the “beauty” and “femininity” that Rae’s paintings were often prized for, this cluster of late nineteenth-century Isabellas raises an immediate question: why were so many female artists attracted to this particular poem at this particular time? The answer is two-fold: first, in every visual interpretation of this poem by a woman artist that I have seen, the heroine is physically demure, either bending over or crouching, while the pathos of this “sad ditty” (501), to use Keats’s words, is emphasised. As Charlotte Yeldham states, “The majority of these ‘literary’ works share two common points: female subjects and the theme of sadness” (135). In a decade that witnessed the rise of the New Woman, female artists were lamenting the hopeless plight of Keats’s medieval heroine; condemned to the “stiller doom” that Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre rails against in 1847 (121), Isabella wastes away as a result of the callous disregard of her brothers (affording an opportunity, perhaps, to criticise the artistic brotherhoods that women were excluded from yet heavily influenced by). Focusing on a heroine whose prospects are formed by loss and incarceration provides a strong counter-response to—or, at the very least, a commentary on—the conservative cultural anxieties that were prevalent during this period.

A second factor determining the preponderance of Isabellas at this time is less related to ideology and more to prevailing artistic trends. Female artists, as well as their male counterparts, were indebted to the compelling iconography of a single image. With a prominent female figure, flourishing pot of basil, and an emphasis on rich, decorative fabrics, these women artists demonstrate the potent influence of Holman Hunt’s “Isabella and the Pot of Basil” (1867). The image was so widely reproduced, largely in the form of Blanchard’s engraving (published in 1869), that The Times declared it to be “a picture which has long since become the classic rendering in art of this last episode of Keats’s poem.”[13] Hunt’s painting therefore becomes, as Christine Torney suggests, a “stock property,” the primary source for subsequent visual interpretations of “Isabella” (cited in Pearce 98). It could even be said that, to a large extent, Keats’s poem is effectively “painted out” of these pictures.

The dominance of Hunt’s Isabella is not only evident in paintings of the period. One critic described “Isabella” as “a design which every black and white artist is doomed to attempt sooner or later” (E. B. S. 108). Examples of the widespread dissemination of Hunt’s image include W. J. Neatby’s illustration for A Day with the Poet Keats (circa 1909), and Averil Burleigh’s highly derivative illustration of 1910.[14] The prominence accorded to illustrations, as well as paintings, in The Bookman Keats-Shelley Memorial Souvenir of 1912 (which features Neatby’s illustration and two by Burleigh), indicates the demand for lavishly illustrated volumes of Keats’s poetry during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with a number of individual poems published as ornamental keepsakes.[15] It is the medium of book illustration that produced some of the most innovative images of Keats’s “Isabella” by women artists, however.

Regarded as a late or “neo” Pre-Raphaelite, Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale’s highly detailed and symbolic style made her an ideal illustrator for the exclusive editions of well-known literary texts produced during this period. A versatile and accomplished artist, Brickdale produced at least one painting a year for submission to the Royal Academy, worked in watercolour, and later became a designer of stained glass (there is a window by her in Bristol Cathedral). Brickdale’s reputation was, however, primarily as an illustrator and her output was extensive. For example, she illustrated two volumes of Robert Browning’s poems in 1908 and 1909 respectively while also, during the same period, producing 28 images based on a Pre-Raphaelite favourite, Tennyson’s Idylls of the King.

Brickdale’s design for “Isabella” (fig. 4: Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale, “Isabella”) exemplifies what an article in The Times praised as the “great force and solidity” of her drawings, which are “bold and vivid in the extreme.”[16] Her “Isabella”, as reproduced in The Studio in 1898, evokes an oppressive atmosphere: yet, unlike Hunt’s “Isabella,” where the enclosed surroundings emphasise the accessibility of and potential for intimacy with the heroine, this version comments on psychological and social constraints. The unconventional choice of a landscape, as opposed to a portrait, format compresses the heroine (forcing her to hunch over the basil plant) while opening out the rest of the room. A series of closed windows, with only one revealing a chink of the landscape outside, represents the limits of the heroine’s existence. Her surroundings suggest the possibility of space, yet her confinement is reinforced by the vertical and horizontal lines that structure the composition. At the same time, any deviation from this uniformity is necessarily highlighted; for example, the pattern created by the three square cushions to the left of the heroine is echoed but not mirrored in the two cushions to the right. Most tellingly, the sweeping train of Isabella’s gown challenges the linear conformity of the image and redirects attention on to the irregular folds of the drapes, the heart-shaped cushion to the right of the heroine, and the undulating hills beyond. Brickdale’s design may, at first glance, seem to be imitating the common Pre-Raphaelite trope of framing, or metaphorically imprisoning, the heroine (see, for instance, Millais’s “The Eve of St Agnes,” 1863), but here Isabella’s soft, flowing curves exceed the boundaries of any potential restraints.

Figure 4

Aspects of Brickdale’s style and approach are discernible in the work of a fellow illustrator of this period, Jessie Marion King, whose visual renderings of literary texts are arguably even more unconventional.[17] Janice Helland rightly describes King as an “outstandingly accomplished designer”: before graduating, she was offered and took up a teaching post in book decoration and bookbinding at the Glasgow School of Arts and was awarded a gold medal for her book designs at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in 1902 (781). Her oeuvre is astonishingly wide-ranging, encompassing posters, bookplates, wallpaper, murals, fabrics, costumes, ceramics, interior design, silver, jewellery, and work in batik, a technique she learned in Paris and introduced to Scotland. It is, however, for her highly individual illustrations—with flowing, gossamer lines, controlled spaces and stylised motifs—that King is best known, having designed and illustrated around two hundred books over the course of her career. As one contemporary critic noted: “the stamp of a strong personality is seen on everything that is produced” (Watson 187).

King returned to Keats’s poetry on a number of separate occasions. As well as illustrations for Keats’s “Isabella” in 1907, her first commission for the Envelope Books series, King produced the following: a later watercolour on this theme, dated 1935; at least two elaborate bookplates inscribed with the last two lines from “Ode on a Grecian Urn;” a pen, ink and pencil sketch inspired by the same ode, entitled “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter;” and three very different illustrations for “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” which will be examined shortly.[18] King’s watercolour illustrations for “Isabella” demonstrate the customary debt to Hunt’s version in a full-page portrait of the heroine clasping her basil plant, while a billowing lilac gown and abundance of hair denote broader Pre-Raphaelite influences (fig. 5: Jessie Marion King, “Isabella and the Pot of Basil,” 1907 [a]).[19] The colouring is soft in all the illustrations—predominantly blues, greens and purples—with only the brothers depicted in bold primaries (perhaps borrowing the reds and yellows of Millais’s controversial painting, “Isabella and Lorenzo,” 1849). King’s early work was undoubtedly indebted to the Pre-Raphaelites: yet while the “Glasgow Style” can be seen, in some respects, as a final flourishing of Pre-Raphaelitism, it also signals a departure, demonstrating how, as Jan Marsh and Pamela Gerrish Nunn argue, “from the end of the Pre-Raphaelite impulse, the women artists of the Glasgow group were able to develop a style and an art practice that looked forward to the art of the twentieth century” (137). Indeed, King can be considered a Symbolist and her work in Paris influenced the beginnings of the Art Deco movement. Furthermore, the graphic art of Aubrey Beardsley had an evident impact on her style, particularly in the use of lines and dots, but there is little trace of decadence in King’s work; in fact, there is as much of Italian art here, Botticelli in particular, as there is of Beardsley or the Pre-Raphaelites.[20] King’s Isabella and, as we shall see, her Belle Dames display both an indebtedness to, and conscious detachment from, sources of artistic influence, an approach which mirrors the “mixture of progress and retrenchment” characteristic of all her work (Marsh and Nunn 118).

Figure 5

King is one of only a few illustrators to engage with the disturbing scene of Lorenzo’s disinterment in “Isabella” (fig. 6: Jessie Marion King, “Isabella and the Pot of Basil,” 1907 [b]). Robert Anning Bell’s illustration of 1897 presents this “wormy circumstance” (385) as a moment of grotesque fantasy: Lorenzo’s exhumed remains lie discarded in the foreground of the image while the old nurse who, in Keats’s poem, assists in the “dismal labouring” (379) here shields her eyes (directing the implied viewer’s response).[21] This image of female triumph is not only reminiscent of Beardsley’s influential illustrations for Salome, most notably “The Climax” (1893), but can also be traced back to Keats’s poem. Illicit desires surface when Isabella nurtures the head of her dead lover; her “prize” or “jewel” is wrapped in a silken scarf and kept sweet with “divine liquids [that] come with odorous ooze” (402, 431, 411). Typically singular in her treatment of the source, King does not capitalise on the potentially perverse eroticism of these “purple phantasies” (370). Instead, King contrasts the rigid vertical lines of the trees, which emphasise Isabella’s imprisonment within a thwarted desire that will leave her “lone and incomplete” (487), with the curves of her feminine form as she delicately lowers Lorenzo’s head into the pot. The scene concentrates on a touching yet macabre emotional intimacy, such as that depicted in stanza 51:

401-8She calm’d its wild hair with a golden comb,

And all around each eye’s sepulchral cell

Pointed each fringèd lash; the smeared loam

With tears, as chilly as a dripping well,

She drench’d away:—and still she comb’d, and kept

Sighing all day—and still she kiss’d, and wept.

What King manages to capture is the complex inter-relationship between sadness and sensuality in Keats’s poem.

Figure 6

That King is no ordinary artist is similarly apparent in her illustrations to “La Belle Dame sans Merci.” Once again, however, female artists have been largely sidelined or omitted from accounts of the visual afterlife of this poem. Joseph Kestner, in Masculinities in Victorian Painting, reads images of “La Belle Dame” as important sites for contesting monolithic ideas of masculinity, yet asserts that only one representation of Keats’s poem was by a female artist (110). The painting in question is by Anna Lea Merritt and was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1884; this version, now lost, envisages a buxom Belle Dame in Grecian pose with her hair cascading onto the drowsy knight.[22] Admittedly, “La Belle Dame sans Merci” was not quite as popular with women artists as “Isabella,” a trend that is equally discernible amongst male artists until William Waterhouse’s painting of 1893 signalled a flurry of visual representations during the fin-de-siècle and early twentieth century. Nonetheless, Elizabeth Siddal produced a series of rather stark sketches on this theme in the early to mid 1850s, generating a complex dialogue with Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s attempts to visualise this poem at the same time, and Mildred Collyer exhibited a painting entitled “La Belle Dame sans Merci” at the Royal Academy in 1897, although no trace of the work now survives.[23]

While it is understandable, even if unfortunate, that Kestner overlooks such works, it is less forgivable that King’s designs for this poem are not acknowledged. Grant F. Scott’s article on the visual heritage of “La Belle Dame sans Merci” is more comprehensive, making reference to interpretations by women artists, albeit sometimes in passing. Most notably, Scott reproduces a pen and ink drawing by King, yet sees it as “an anomaly of sorts,” produced by an artist who “worked outside the London-based art world of the Royal Academy” (532).[24] King’s lady is neither a predator nor a victim which, for Scott, relegates the sketch to a coda at the end of the article (effectively dislocating the image from the construction of a visual history in the main argument). King’s responses to Keats’s poetry, while exceptional, do not run counter to the tradition of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Belle Dames. She is, for instance, indebted to Waterhouse’s well-known version for the heroine’s expression of honest affection for her mate; and, looking ahead, her renderings of Keats’s poem also anticipate some of Frank Cadogan Cowper’s post-war iconography, particularly the cobwebs and poppies, in his painting of 1926.[25]

King produced three distinctive designs based on Keats’s ballad between 1902 and 1908.[26] King’s eclectic style and unique combination of indebtedness and innovation informs all her renderings of this poem; these designs capture what Cordelia Oliver describes as her “expressive web of flickering lines and tiny sharp accents of black” (9). Her illustration to the lines “They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci/ Thee hath in thrall’” (39-40), circa 1902 (fig. 7: Jessie Marion King, “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” c.1902), initially appears to inherit a legacy of Victorian conservatism, focusing on the fraternity between the “pale kings and princes” and the knight (37). His cupped hands gesture towards the brotherhood that stand before him and his attire indicates kinship. Rather than the knight becoming her latest conquest, the Belle Dame appears to be attempting to prevent his movement towards the group. Yet her lowly position at the foot of the drawing, hanging on to the knight’s coat-tails, suggests that her efforts will be in vain. It is not the woman who has bewitched the man—he disregards the maiden at his feet—but a sense of belonging, the irrepressible urge to preserve an old, established order. La Belle Dame is spatially peripheralised and bound to a chain of events she cannot stop (the rose design hanging from her dress literally resembles a ball and chain). This is, as Scott perceptively states in a footnote, a “provocative and revisionist drawing” (n. 532), which effectively shifts any blame for the knight’s thralldom onto the kings and princes—or, indeed, onto the knight himself and his own construction of a nightmare scenario. In fact, I would argue that this sketch has more in common with feminist interpretations of Keats’s poem than turn-of-the-century anxieties over the New Woman.[27]

Figure 7

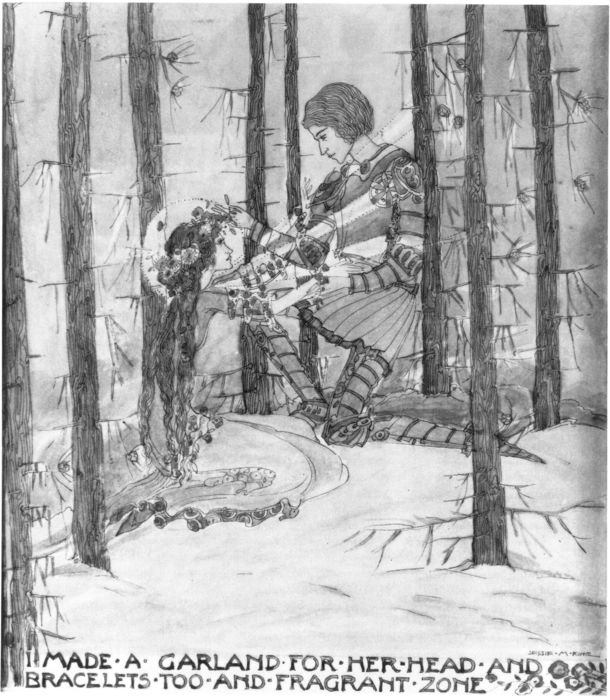

In the version dated circa 1907 (fig. 8: Jessie Marion King, “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” c.1907), the same year as King produced her illustrations for “Isabella,” the kings and princes have disappeared and the knight has fallen to his knees (although he still remains positioned above the Belle Dame). The lines included on the base of the drawing are taken from the verse in which the male courts the female, “I made a garland for her head,/ And bracelets too, and fragrant zone” (17-18), suggesting a reading of the lady as receptive foil for his chivalric pursuit. La Belle Dame is suitably devoid of any threatening intent; her head is framed by a halo—represented by a crown of stars in the earlier drawing—which radiates shafts of light onto the knight.[28] The knight can be seen, in this drawing, to be worshipping at a shrine. As Scott suggests, “King’s knight disguises no darker purpose…[He] regards her not with suspicion but with affection” (534). Contrary to the expectations raised by the verso, this version circumvents readings of the poem, and other visual renderings, that prioritise a gender battle. King’s lovers embrace through the delicacy of touch and a mutual adoration. In other words, this version encourages a reading of communion rather than conflict between the sexes.

Figure 8

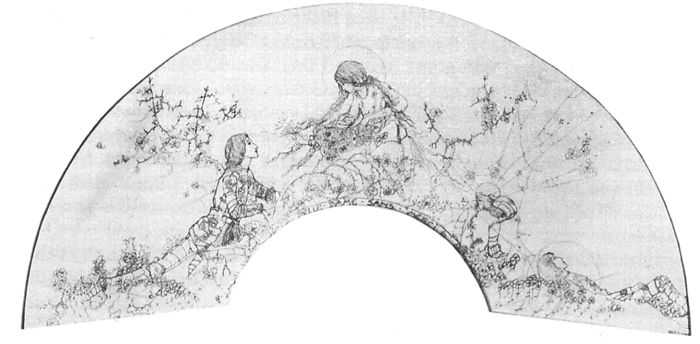

The theme of mutual adoration is explored further in King’s final reworking of Keats’s poem: a pen and ink fan design, circa 1908 (fig. 9: Jessie Marion King, “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” c.1908). This is, to my knowledge, the only image that perceives the poem as a sequence; from left to right, a series of seamless vignettes construct a visual narrative. The lady occupies the central position at the apex of the fan; she bends towards the depiction of the knight on the left of the design as he leans forwards against the inner curve. The intense gaze shared by the lovers in the 1907 version is evident here: yet the dense foliage growing up between them suggests an imminent separation (whereby, as in the many Pre-Raphaelite images based on Sleeping Beauty, suitors become enmeshed in the deadly undergrowth).[29] This ominous sign seems to be averted by a small scene of the lovers huddled together on the right-hand side of the fan. Their embrace is not sexual, resembling an almost child-like alliance; rather than a devastatingly attractive woman whose charms lure unsuspecting men, this Belle Dame is girlishly innocent. However, we view this scene through the frame of a cobweb, the epicentre of which falls across the lady’s face, indicating that she is either the subject or the architect of an impending doom. If this organic structure is the visual representation of Keats’s narrative—with strands of the web linking objects like words—then King is suggesting that both the hero and the heroine are caught in the machinations of this ballad. Yet directly beneath this scene, the figure of the lifeless knight is laid out across the bottom edge of the fan. His halo, denoting a virtuous aura, seems to create a protective bubble around the upper-half of his inert figure, but the spider’s web above him and the poppies that carpet the floor beside him indicate a more tragic end.

Figure 9

This version of “La Belle Dame” is the first visual interpretation of the poem to engage with Keats’s themes of inertia and decay. Primarily, this is highlighted through the medium of the fan, with its visual evocation of nature’s cycle and, perhaps, the process of artistic composition: conversely, it also reminds us of the knight’s lethargy, an unseasonable fruitlessness at odds with his role. There is a sense of continuity, but not necessarily progression, within this semi-circular form. The viewer’s gaze travels from the figure of the dead knight back to the beginning of the visual narrative where the hero is, once again, attempting to win the heroine. The compulsion to court, and the resulting waste of the knight’s youth and vigour, constitutes an inevitable and recurring path. The lovers may be restricted by the knight’s pessimistic view of their liaison, but they are also bound by the conventions of the romance, reflecting a Keatsian scepticism about the genre.

What makes King such a successful visual interpreter of Keats’s poems is her sustained interaction with and sensitivity to his trademark indeterminacy; Keats’s negative capability, the creative possibilities that arise from his verse, are realised through King’s distinctive “language of line” (Watson 177). Indeed, King’s husband, E. A. Taylor, perceptively referred to her as “the poet’s artist” (cited in Helland 782). After establishing a thriving artistic community in Kirkcudbright, which also acted as an important centre for women painters, King became a legend in her own lifetime; unhappily, however, her work has largely slipped from view, except for studies of Scottish art or the “Glasgow Style.” In part, this essay has been an attempt to restore King to her rightful place “among the great illustrators of the twentieth century" (A Guide to the Printed Work of Jessie M. King 12). More broadly, I have endeavoured to reintroduce a missing, or merely forgotten, aspect of Keats’s visual heritage; and, with it, provide what I consider to be an essential chapter in the development of artistic responses to literature. This essay has not succeeded in being comprehensive; there are many other visual renderings of Keats’s poetry by women artists that I could have discussed.[30] However, what I hope to have achieved, or even approximated, is what Nina Auerbach refers to as “the recovery of the lost history of life” (52).

Appendices

Biographical notice

Sarah Wootton is a Lecturer in English Studies at Durham University. She is the author of Consuming Keats: Nineteenth-Century Representations in Art and Literature (Palgrave, 2006), and has published a wide range of book chapters and journal articles on nineteenth-century literature and the visual arts. Her second book, entitled The Rise of the Byronic Hero in Fiction and on Film, is under contract with Palgrave. She is a co-director of the “Romantic Dialogues and Legacies Research Group” at Durham University.

Notes

-

[1]

In her essay “Keats Reading Women, Women Reading Keats,” Margaret Homans examines the poet’s fears about women readers and the interrelated issues of gender and class. By contrast, comparatively little attention is devoted to the ways in which women have read Keats, except to argue that his apparent femininity renders him an “honorary woman” (343). On the subject of Keats’s femininity, see Wolfson, “Feminizing Keats,” Critical Essays on John Keats, ed. Hermione De Almeida.

-

[2]

The author’s effusive praise for the “glorious word-pictures” of Endymion, “an inexhaustible treasury of the sweetest and most delicate poetry” (65, 61), is remarkably similar to nineteenth-century descriptions of “The Eve of St Agnes” as, for instance, a ray of sunlight falling “gorgeously and delicately upon us” (cited in Hill 61-2).

-

[3]

Amy Lowell, John Keats. Lowell’s first volume of poetry, A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass (1912), is infused with Keats’s influence. William Henry Marquess has argued that Lowell’s love of Keats bordered on obsession. More recently, Homans has explored the ways in which Lowell’s fascination with Keats was connected to, and helped facilitate, her same-sex tendencies. See Untermeyer, Marquess, and Homans.

-

[4]

Marie Corelli’s poem “Keats to Severn” appears in both The Bookman Keats-Shelley Memorial Souvenir and The John Keats Memorial Volume. The latter publication also features a poem by Amy Lowell, entitled “On a Certain Critic,” and Alice Meynell’s “A Retrospective Note.” Meynell wrote a fascinating elegy, “On Keats’s Grave” (1869), and later wrote an introduction for Poems by John Keats, which was published in 1903.

-

[5]

The volume on Keats in the Critical Heritage Series does not include any named female critic or biographer. One poet, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, is given two pages; see Matthews.

-

[6]

See Wootton; short sections of my book appear here in revised form.

-

[7]

A third version, by Ida Nettleship, was exhibited at the National Gallery in 1898, but no trace of the painting now survives. Nettleship’s reputation as an artist was eclipsed by her more famous husband and sister-in-law, Augustus and Gwen John. For further details, see Thomas.

-

[8]

For further details of the lost or untraced paintings discussed in this essay, including where they were exhibited and reproduced, see Yeldham.

-

[9]

Wood 1: 45, 196. A painting by Gloag, “Four Corners to My Bed,” is reproduced in the plates section of Wood’s survey (2: 217).

-

[10]

In an article for the Magazine of Art, James Greig comments on the “distinct impression” made by “The Magic Mantle” when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1898. In addition, Greig notes that the expression on the face of the fleeing woman in this painting is one of anger rather than shame, and commends the “flesh-painting” on display in “Rapunzel” (289-91).

-

[11]

John Keats, “Isabella; or, the Pot of Basil” 489, 491-2.

-

[12]

See Fish. The painting was sold at auction in 1989 for £28,600.

-

[13]

The Times, 15 Mar. 1886: 12. The influence of Hunt’s “Isabella” is not only felt in renditions by female artists; its widespread dissemination is apparent in numerous images by male artists, such as John Melhuish Strudwick’s 1879 painting on this theme. See also John White Alexander’s “Isabella and the Pot of Basil,” first exhibited in 1897, and Mary Lizzie Macomber’s “Isabella” of 1908 (both paintings are now owned by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston).

-

[14]

The inlay that decorates the wooden table in Neatby’s illustration is an almost exact replica of Hunt’s. Such direct borrowings are not only confined to lesser-known illustrators. In Waterhouse’s painting of “Isabella” (1907), for instance, the skull-head that decorates the stone plinth and the design on the watering can are strikingly similar to details in Hunt’s painting.

-

[15]

Also included in The Bookman, Rae’s “Isabella,” now virtually unknown, is accorded a full-page reproduction in contrast with the quarter-page devoted to Hunt’s image.

-

[16]

Brickdale’s “Isabella” is reproduced in “Eleanor F. Brickdale: Designer and Illustrator”: 106. The article from The Times is cited in Marsh and Nunn 144.

-

[17]

Like Brickdale, Jessie Marion King achieved early recognition with a full-length illustrated article in The Studio. Another parallel between these two artists is the transition from a highly detailed style to flat colour and outline illustrations.

-

[18]

One of the bookplates for “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” dated 1900, illustrates the front cover of an exhibition catalogue of King’s work (see Jessie M. King and E. A. Taylor: Illustrator and Designer). The design shows two kneeling women facing one another in perfect symmetry. The sphere at the top of the design, which radiates loops of stars across and around the women, generates a circular pattern that captures visually the enigmatic poise of Keats’s famous lines, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

-

[19]

Figures 5-9 are reproduced courtesy of Dumfries and Galloway Council and The National Trust for Scotland as copyright holders in the work of Jessie M. King. Colin White claims that King’s illustrations for “Isabella” were “sensitively done,” but the poor colour reproduction process of the time “hardly did justice to the understanding and sympathy that Jessie had put into her illustrations" (The Enchanted World of Jessie M. King 66). With regards to the images included in this essay, every effort has been made, where relevant, to locate copyright holders.

-

[20]

King was inspired by the works of Botticelli during a tour of Italy in 1902.

-

[21]

Anning Bell’s illustrations for Keats’s poems are rather uneven. Alongside unimaginative head and tailpieces of coquettish women, the controlled use of space and line singles out a few images as insightful commentaries on concealment and perception, prominent themes in Keats’s narrative poems. An illustration for “Isabella,” for instance, shows the brothers peering through a chink in the curtains as the unsuspecting lovers move out of view, while an illustration for “The Eve of St Agnes” shows the “agèd creature” (91), Angela, shuffling along as Porphyro waits, concealed behind a pillar. The artist’s facing-page illustration for “La Belle Dame sans Merci” is particularly effective; the slumbering knight, in the arms of his lover, dreams of the kings and princes as they emerge, menacingly, out of the rock face. Anning Bell also produced an oil painting based on this poem, which shows the knight pleading with the Belle Dame.

-

[22]

A sketch based on Merritt’s painting appeared in Academy Notes (see Yeldham 123). Kestner also asserts: “Only in this canvas by a woman is the male shown asleep, although it is a major motif of the Keatsian source. Thus did males edit and expurgate their sources to present dangers but not defeat” (110). This overlooks the figure of the sleeping, or even dead, knight in Russell Flint’s, Henry Meynell Rheam’s and Frank Cadogan Cowper’s paintings, as well as a number of illustrations.

-

[23]

Grant F. Scott states that Elizabeth Siddal and Dante Gabriel Rossetti produced at least seven images based on this poem between 1848 and 1855. There has also been some speculation that Siddal produced a watercolour version of “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” but no trace survives. Scott also makes reference to an oil painting based on the poem by Sarah Lane in 1868, which is now lost; see 505-6.

-

[24]

Scott estimates that the drawing was produced between 1900 and 1910: it is more precisely dated by Marsh and Nunn at 1907.

-

[25]

Cowper produced an earlier work on this theme, exhibited at the Royal Watercolour Society in 1905, which bears little resemblance to his later painting (in the 1905 version, the Belle Dame sits at the base of a tree playing a lute, a reference perhaps to the “ancient ditty” called “La belle dame sans mercy” that Porphyro plays on Madeline’s lute in “The Eve of St Agnes,” 291-2). The artist returned to Keats’s ballad a third time, as late as 1946, to produce a watercolour based on his 1926 version.

-

[26]

In addition, King staged the poem as a tableau vivant in 1917 to raise money for war charities.

-

[27]

See, for instance, Mellor 93-4.

-

[28]

For King, this visual trope reflects a spiritual belief in auras.

-

[29]

See, for example, Burne-Jones’s Briar Rose sequence.

-

[30]

Keats’s “Lamia” was another popular source of visual renderings for women artists during the period under discussion. For example, Anna Lea Merritt produced an oil painting entitled “Lamia, The Serpent Woman” in 1906. Elenore Abbott also produced illustrations for both “Lamia” and Endymion.

Works Cited

- Auerbach, Nina. Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1982.

- Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. 1847. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2002.

- E. B. S. “Eleanor F. Brickdale: Designer and Illustrator.” The Studio 13 (1898): 103-8.

- Fish, Arthur. Henrietta Rae. London: Cassell, 1905.

- Greig, James. “Isobel Lilian Gloag and her Work.” Magazine of Art (1902): 289-92.

- Helland, Janice. “King, Jessie M(arion).” Dictionary of Women Artists. Ed. Delia Gaze. 2 vols. London: Dearborn, 1997. 780-2.

- Hill, John Spencer, ed. Keats: Narrative Poems. London: Macmillan, 1983.

- Homans, Margaret. “Amy Lowell’s Keats: Reading Straight, Writing Lesbian.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 14.2 (2001): 319-51.

- Homans, Margaret. “Keats Reading Women, Women Reading Keats.” Studies in Romanticism 29 (1990): 341-70.

- Jessie M. King and E. A. Taylor: Illustrator and Designer. London: Belgravia, 1977.

- Keats, John. The Complete Poems. Ed. John Barnard. 3rd edn. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988.

- Kestner, Joseph A. Masculinities in Victorian Painting. Aldershot: Scolar, 1995.

- Lowell, Amy. John Keats. 2 vols. Boston: Mifflin, 1925.

- Marquess, William Henry. Lives of the Poet: The First Century of Keats Biography. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP, 1985.

- Marsh, Jan, and Pamela Gerrish Nunn. Women Artists and the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. London: Virago, 1989.

- Matthews, G. M., ed. Keats: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge, 1971.

- Mellor, Anne K. English Romantic Irony. London: Harvard UP, 1980.

- Meynell, Alice. Introduction. Poems by John Keats. London: Blackie, 1903.

- Oliver, Cordelia. Jessie M. King 1875-1949. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council, 1971.

- Pearce, Lynne. Woman/Image/Text: Readings in Pre-Raphaelite Art and Literature. London: Harvester, 1991.

- Scott, Grant F. “Language Strange: A Visual History of Keats’s ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci.’” Studies in Romanticism 38 (1999): 503-35.

- The Bookman Keats-Shelley Memorial Souvenir. London: Hodder, 1912.

- “The Daintiest of Poets—Keats.” Victoria Magazine 15 (1870): 55-67.

- The John Keats Memorial Volume. London: Lane, 1921.

- Thomas, Alison. Portraits of Women: Gwen John and Her Forgotten Contemporaries. 1994. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

- Untermeyer, Louis, ed. The Complete Poetical Works of Amy Lowell. Boston: Mifflin, 1955.

- Watson, Walter R. “Miss Jessie M. King and her Work.” The Studio 26 (1902): 176-88.

- White, Colin. A Guide to the Printed Work of Jessie M. King. London: Knoll, 2007.

- White, Colin, The Enchanted World of Jessie M. King. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1989.

- Wolfson, Susan. “Feminizing Keats.” Critical Essays on John Keats. Ed. Hermione De Almeida. Boston: Hall, 1990. 317-56.

- Wood, Christopher. Victorian Painters. 2 vols. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1995.

- Wootton, Sarah. Consuming Keats: Nineteenth-Century Representations in Art and Literature. Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave, 2006.

- Yeldham, Charlotte, Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France and England: Their Art Education, Exhibition Opportunities and Membership of Exhibiting Societies and Academies, with an Assessment of the Subject Matter of their Work and Summary Biographies. 2 vols. London: Garland, 1984.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9