Abstracts

Abstract

The Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation, colloquially known as the “McGill Guide,” is both a strong symbol of, and a prerequisite for, any form of engagement within Canadian legal academia. While studying law requires a deep understanding of the Guide, it does not inherently encourage interrogation of the pedagogical structures the Guide upholds. In this sense, critical engagement with the politics of citation is often overlooked in legal curricula.

Examining their own attempts to centre Indigenous knowledge systems in legal research, the authors suggest that a critical failure in efforts towards decolonization of the legal academy resides in the exclusionary and Eurocentric nature of legal citation practices. They argue that citational politics become more problematized when scholars must “fit” Indigenous Knowledge into one of the pre-existing Western sources of law included in the Guide, a process that frequently results in Indigenous Knowledge being relegated to the unenviable bibliographic category of “other materials.”

The authors argue that there is an opportunity to valourize long-subjugated Indigenous knowledge and amplify voices often silenced within the academy through the decolonization of legal citation methods. Situating the conversation of Indigenous citation politics and exploring the input of Indigenous librarians and scholars from a variety of academic fields, the authors survey a variety of citation manuals across disciplines and present the case for creating inclusive Indigenous legal citation practices. Beyond Indigenous oral knowledge citation, the authors specifically turn their minds to the citation of wampum and “extra-intellectual knowledge” including art, beadwork, and personal knowledge such as dreams, encouraging learners and researchers to engage in thoughtful citation practices and imagine decolonial legal futures grounded in a spirit of traitorous love.

Résumé

Le Manuel canadien de la référence juridique, plus couramment appellé le « Guide McGill », est à la fois un symbole important et une condition préalable à toute forme de participation dans le milieu universitaire juridique canadien. Bien que l’étude du droit exige une compréhension approfondie du Guide, elle n’encourage pas en soi l’interrogation des structures pédagogiques qu’il soutient. En ce sens, l’engagement critique en ce qui concerne les politiques de la référence juridique est souvent négligé dans les programmes d’études juridiques.

En examinant leurs propres tentatives cherchant à mettre en évidence le savoir autochtone dans la recherche juridique, l’auteur et l’auteure avancent que l’échec flagrant des efforts déployés vers la décolonisation du milieu juridique universitaire réside dans la nature excluante et eurocentrique des pratiques de la référence juridique. Ils et elles soutiennent que les politiques de la référence juridique deviennent plus problématiques lorsque les chercheurs et chercheuses doivent « faire rentrer » le savoir autochtone sous l’une des sources occidentales de droit préexistantes qui figure dans le Guide, un processus qui aboutit souvent à la relégation du savoir autochtone à la catégorie bibliographique peu enviable « Autres documents ».

L’auteur et l’auteure soutiennent qu’il y a une possibilité de faire valoir le savoir autochtone, longtemps subjugué, et d’amplifier les voix souvent réduites au silence dans le milieu universitaire par la décolonisation des méthodes de référence juridique. En situant la conversation autour des politiques de références autochtones et en explorant les contributions de bibliothécaires et de chercheurs et de chercheuses autochtones dans plusieurs domaines d’étude, l’auteur et l’auteure font l’examen d’une variété de manuels de référence dans diverses disciplines et présentent des arguments en faveur de la création de pratiques de référence juridique autochtones inclusives. Au-delà du savoir autochtone oral, l’auteur et l’auteure s’intéressent plus particulièrement à la référence concernant de « wampums » et du « savoir extra-intellectuel », qui comprend l’art, le perlage et le savoir personnel comme les rêves, encourageant ainsi les apprenants et apprenantes et les chercheurs et chercheuses à s’engager dans des pratiques de référence réfléchies et à imaginer des avenirs juridiques décolonisés fondés dans un esprit d’amour traitre.

Article body

Relationality Statement

As members of the legal profession, we must seek to acknowledge and confront our past and present contributions to, and complicity in, the ongoing colonization of Indigenous peoples and lands. We purposely use “we” because the process of decolonization is impossible to engage in alone. While personal engagement is integral to decolonial thought and action, it alone will not accomplish decolonial objectives.[1] To attempt decolonial action solely as individuals would be to perpetuate and reinforce the hyper-individualistic mindset that breeds colonial constructions of society in the first place.[2] In contrast, decolonial action is “derived from a web of consensual relationships that is infused with movement (kinetic) through lived experiences and embodiment.”[3] These consensual relationships help us to address gaps in our legal knowledge and practice that we may not consciously appreciate.[4]

In fact, to do decolonial action as a collective, across Indigenous-settler and more than human relations, “allows us to move together and address renewal of our relationships.”[5] This renewal can occur at multiple sites of life and living, including friendships,[6] kinship,[7] lands, water, and relations with more than human entities,[8] and ideally through Indigenous-state relations.[9] Exploring these sites in our own lives is what Dwayne Donald refers to as ethical relationality in which we acknowledge all relations that support life.[10] Grounding decolonial work in ethical relationality allows us to see where we come from and where we are going, and informs the ways in which we can contribute to the resistance of colonial progression.[11]

Despite the inherently relational nature of law and legal education, Western academia typically discourages us from self-identifying in our work and fails miserably at understanding the important relationships and enduring bonds that can form between educators and Learners. As Dr. Aaron Mills states, academia would have us believe that our words exist as self-producing sentences removed from our personal histories and connections to the topics on which we write[12] We resist these colonial notions by situating our identities and our relationships here, from the outset.

Dr. Danielle Lussier (she/her/elle) is Red River Métis, born and raised in the homeland of the Métis Nation on Treaty 1 Territory, who now raises her three children as a citizen of the diaspora and a long-term visitor on on the shores of Lake Ontario. She holds a PhD in Law, and her research considers the development of Indigenous legal pedagogies, the role decolonized methodologies can play in the revitalization of Indigenous legal orders and valorizing of Indigenous knowledge systems, and the pathways towards the decolonization of legal education and the legal profession. She believes there is room for Indigenous ways of knowing, including the foundational law of love, in the practice of law and legal education.

Steven Stechly (they/them) is a graduate of McGill University with a BASc in Psychology and Political Science and a current Learner in the JD program at the University of Ottawa. Steven is the descendant of Polish refugees and is deeply connected to the British Isles, from where their maternal family originates.

We state our backgrounds both to position ourselves within the work and to meet specific ethical and community needs. For Danielle, a statement of relationality is critical to provide context to her position within both communities and the academy. For Steven, they have used this moment to interrogate their identity as a “Canadian” and better understand how they came “to” rather than “from” this land. Steven is also a proud queer and non-binary person, which they believe inherently shapes their lived experiences and relationships; this mirrors Danielle’s experience of her own identities as an Auntie, mother, and long-term visitor on someone else’s territory, shaping her understandings of law and legal learning.

We are connected through a complex web of relationships developed at the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa, beginning in the autumn of 2019. Our relationship is the result of reciprocal learning and support on a journey of decolonizing legal education. The dialogue that follows documents and builds on conversations in which we engaged while footnoting Law with Heart.[13]

As we engage in this dialogue, one that we hope might prompt both personal reflection and individual and institutional action, we are guided by Dr. Tracey Lindberg’s encouragement for those engaging in decolonial and anti-colonial work within the academy:

You need to love law so much that you suspend your disbelief, decolonize your education, and open your mind to the possibility that colonization is a thing that happened and that you are going to learn it, deconstruct it, replace it, and support the work of Indigenous peoples in our re-build. You are going to need to be a traitor, because allyship is not enough.[14]

We offer this humble contribution to the important and ongoing conversations within the academy in a spirit of traitorous legal love.

Introduction

Footnotes, they tell stories.

The Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (the Guide),[15] colloquially known as the “McGill Guide,” is both a strong symbol of, and a prerequisite for, any form of engagement within Canadian legal academia. While studying law requires a deep understanding of the Guide, it does not inherently encourage interrogation of the pedagogical structures the Guide upholds. In this sense, critical engagement with the politics of citation is often overlooked in legal curricula.

The politics of citation are a foreign concept to many, but choosing whom to cite, when to cite, and how the works of others are positioned within one’s own scholarship, is an active resistance strategy often employed by those pursuing Indigenist, decolonial, and anti-colonial research agendas.[16]

For Steven, this started in the course “Indigenous Laws and Legal Orders & Critical Indigenous Legal Theory” taught by Dr. Tracey Lindberg at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law. Dr. Lindberg’s course was built around the process of (un)learning Indigenous exclusion within the legal academy. This learning journey often begins with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, particularly Calls 28 and 50. We share these responsibilities here:

28. We call upon law schools in Canada to require all law students to take a course in Aboriginal people and the law, which includes the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations. This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and antiracism.[17]

50. In keeping with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, we call upon the federal government, in collaboration with Aboriginal organizations, to fund the establishment of Indigenous law institutes for the development, use, and understanding of Indigenous laws and access to justice in accordance with the unique cultures of Aboriginal peoples in Canada.[18]

With such important responsibilities, one might question why citation practices should be a priority on the legal academy’s radar. On this point, we highlight Professor Jeffrey Hewitt’s call for reflection when considering Indigenous inclusion in legal education: “[i]n what ways have law schools failed to make room for Indigenous legal orders, Indigenous scholars, and Indigenous legal research methodologies?”[19]

We maintain that one critical failure resides in the exclusionary nature of legal citation practices. In a 2018 interview, Dr. Kyle Powys White and Dr. Sarah Hunt discussed the politics of citation and explained how Eurocentric citation practices have excluded Indigenous voices from academia.[20]

Although often seen as a tedious part of research, citations highlight important ideas, legitimize knowledge, and can bolster intellectual influence and reputations.[21] While some citation manuals, such as the APA 7th edition, have recently included frameworks for citing Indigenous Knowledge,[22] the Guide still offers no direction. Citation politics become more problematized when scholars in the legal profession must “fit” Indigenous Knowledge into one of the pre-existing Western sources of law included in the Guide.

We acknowledge that the 9th edition of the Guide states that projects are in motion to address Indigenous inclusion,[23] and we understand that Dr. Kerry Sloan at the McGill Faculty of Law will be proposing amendments to the Guide that will include Indigenous Legal Knowledge.[24] We welcome the news of this work, in particular given the current global context. As we have weathered almost two years of COVID-19, Indigenous Knowledge is being lost at a devastating rate due to the loss of Elders.[25] Charles Kamau Maina points out that in some African and Alaskan Native cultures there is a saying that “when an Elder dies, a library burns down.”[26] This rapid rate of knowledge loss requires innovation in the ways in which we research, store, write about, and transmit Indigenous Knowledge.

It was also during these waves of COVID-19 isolation and stay-at-home orders that we worked through our collective frustration at our inability to properly cite Indigenous Knowledge sources. In particular, it was the formation of bibliographies in which the Guide classifies knowledge under specific headings where Indigenous exclusion was perhaps the most obvious. Under the Guide’s recommendations, a vast majority of Indigenous Knowledge sources were to be filed under the heading of “Other Materials.”[27] Furthermore, the Guide requires scholars to fit Indigenous Knowledge into neat Western categories of monographs and academic articles in order to legitimize the sources. This process of assimilating Indigenous Knowledge into Western citational frameworks was the source of our mutual discomfort in the current paradigm of legal citational politics. That mutual discomfort is what informed our dialogue on legal citations, which is inherently a reflection of the broad and overarching colonial ideologies that still operate in the academy.

In the pages that follow, we will situate the conversation of Indigenous citation politics, explore the input of Indigenous librarians and scholars from a variety of academic fields, and present the case for creating inclusive Indigenous legal citation practices. We will survey a variety of citation manuals across academic disciplines before specifically turning to legal citation in Canada.

Though we will by no means canvas all sources of Indigenous Knowledge in this short paper, we will discuss Indigenous oral knowledge citation before specifically turning our attention towards selected “extra-intellectual knowledge,” including art, beadwork, and personal knowledge, such as dreams. We will also explore the specific case of Wampum citation.

Finally, we will argue that there is an opportunity to valorize long-subjugated Indigenous Knowledge and amplify voices, which are often silenced within the academy, through the decolonization of legal citation methods. Footnotes and other citation styles offer a window into a scholar’s research journey, and these stories must be presented in a way that recentres Indigenous Knowledge and research methodologies.

Indigenous Representation In the Canadian Legal Landscape

In 1998, Patricia Monture wrote: “[w]hen reading the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Delgamuukw, I did not fail to notice that the imminent scholars the Court chose to quote were (significantly) all white men.”[28] Now leading precedent in Canadian Aboriginal law, the decision produced in Delgamuukw v British Columbia has been cited countless times in both the courts and the legal academy.[29] Coincidentally, Delgamuukw was one of the first cases[30] where the Supreme Court of Canada conclusively stated that Indigenous oral histories were admissible evidence as an exception to the hearsay rule.[31] Now, over two decades of jurisprudence and academic commentary later, the Guide still remains silent on how to reference Indigenous oral histories despite their significant contribution and importance to Aboriginal law. While it would be impossible to measure, based on our own experiences within the academy and legal profession, we note that the implications of this silence are severe and can result in a cooling effect on reliance or engagement with Indigenous Knowledge systems and knowledge keepers. The lack of guidance effectively replicates and compounds colonial understandings of legal knowledge, and through its erasure, ranks Indigenous Knowledge as lesser than other forms that are expressly enumerated in the Guide.

Citation guidance for a diverse range of Indigenous Knowledge would greatly expand the pool of available “legal” resources. We draw attention to the word “legal” in order to acknowledge that inclusive Indigenous citation practices would include scholars in the colloquial sense as well as Elders, peers, and youth.[32] We would note that such knowledge has been previously categorized as “extra-intellectual,”[33] and Indigenous citation guides would ignite a process of legitimizing the use of Indigenous Knowledge, shared by Indigenous peoples, in both the courts and academic institutions.

Professor Hewitt defines decolonization as the complicated work of acknowledging and claiming responsibility for wrongdoings through “naming, dismantling, countering and neutralizing both the collective and individual assertions and assumptions made in relation to Indigenous peoples.”[34] This is not an insignificant project, in the context of post-secondary education. The academy often makes the ridiculous assumption that research and law is a European import to North America,[35] building off a long-held pretense of positional superiority—the theory that positioned Indigenous Knowledge as existing for Europeans to discover, extract, appropriate, and distribute.[36]

However, Indigenous peoples have employed Nation-specific research methodologies to investigate problems, gather and analyze data, present findings, and theorize, since time immemorial.[37] The process of decolonization addresses and seeks to undo a collective amnesia of Indigenous memories, knowledge, and research methodologies caused by colonization.[38] However, in an effort to classify decolonial work as active rather than reactive, Dr. Tracey Lindberg employs a narrative of Indigenous resurgence (renewal).[39] This language is echoed by many other Indigenous scholars.[40]

Indigenous resurgence within academia takes place across a breadth of fields, methodologies, and identities, too diverse to sufficiently cover in this short paper. Paulina Johnson warns that employing a generalized decolonial theory risks overlooking unique and even multicultural worldviews that are expressed through Nation-specific research methodologies.[41] However, in the spirit of reconciling uniform legal citation with diverse and complex Indigenous Knowledge systems, we will approach citational politics with a generalized view of decolonial thought in order to contribute to this emerging conversation.[42]

A common thread throughout various approaches to Indigenous resurgence is relationality. Dr. Shawn Wilson states that a “relational way of being is at the heart of what it means to be Indigenous … [i]t’s collective, it’s a group, it’s a community.”[43] In espousing a scholar-sisterhood practice, Dr. Heather Shotton, Dr. Amanda Tachine, Dr. Christine Nelson, Dr. Robin Zape-tah-hol-ah Minthorn, and Dr. Stephanie Waterman assert that relationality is the core that informs Indigenous scholarship.[44] Furthermore, the relationality imbued within community information transfer contributes to the continuity of cultural knowledge.[45] Indigenous citation guides would uphold and contribute to the resurgence of communally held knowledge by employing relationality in ways, for which Western approaches to legal citation fail to account. As Dr. Margaret Kovach states, by incorporating Indigenous Knowledge systems and research frameworks that are distinctive of cultural epistemologies we are able to challenge and transform the institutional hegemony of the academy.[46]

Indigenous legal citation practices would also contribute to a much broader conversation on Indigenous style guides and knowledge transmission. Importing relationality into citation practices will help bolster existing Indigenous publishing and editing practices which uphold protocols observing respect for Elders, knowledge holders, and oral traditions generally.[47] It is worth expressly stating, for the sake of absolute clarity, that nothing in the following discussion should be read as an absolute or as a proposed universal standard practice. Indigenous information and protocols are not standardized and there is no universal protocol to apply to every Indigenous Nation.[48] Gregory Younging suggests, and we wholeheartedly agree, that any person doing work that centres Indigenous Knowledge should collaborate with the Nation at the centre of the work.[49] Younging further states: “[o]nly Indigenous Peoples speak with the authority of who they are, connected to Traditional Knowledge, their Oral Traditions, their cultural Protocols, and their contemporary identity.”[50] We absolutely agree that communities who have long been excluded from research must be recentred in research processes. Here, we offer a contribution on this academic concern in a spirit of exchange and with a view to ensuring that when knowledge is shared or generated, it can be properly valorized and, where possible and appropriate, amplified.

We are cognizant of the fear of making mistakes while engaging in decolonial work and the cooling effect that fear can have on open dialogue. In offering our perspectives here, we are reaffirming our commitment to consenting to learn in public and welcome the dialogue that may flow from it.

Citational Politics In the Legal Academy

Daniel Heath Justice teaches that when pieced together, citations have the potential to demonstrate the “embraided influence of words, ideas, and voices on the topic at hand.”[51] However, before engaging in a decolonial approach to legal citation, specifically with regard to the Guide, it is important to situate what citational politics are and how Indigenous scholars have mobilized this conversation. We acknowledge that this is a contribution to a collection of much deeper discussion on Indigenous experiences in legal academia.[52] The “Citation Practices Challenge,” organized by Dr. Eve Tuck, Dr. K. Wayne Yang, and Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández, offers critical context:

Indeed, our practices of citation make and remake our fields, making some forms of knowledge peripheral. We often cite those who are more famous, even if their contributions appropriate subaltern ways of knowing. We also often cite those who frame problems in ways that speak against us. Over time, our citation practices become repetitive; we cite the same people we cited as newcomers to a conversation. Our practices persist without consideration of the politics of linking projects to the same tired reference lists.[53]

When speaking about how non-Indigenous scholars cite Indigenous authors, Dr. Kyle Powys Whyte points out that Indigenous women and Two-Spirited authors are rarely acknowledged.[54] Additionally, Indigenous scholars are mostly cited for their “critical work and not their main body of work.”[55] In the same conversation, Dr. Sarah Hunt argues that not only should Indigenous scholars be cited more, so should community sources.[56]

Citing a diverse range of Indigenous Knowledge holders is important because citations are a tool that are used to measure an academic’s intellectual influence with implications for hiring, promotions, and performance evaluations.[57] Dr. Carrie Mott and Daniel Cockayne suggest that academics should adopt conscientious citation practices and acknowledge that citations directly impact the cultivation of diverse information.[58]

Where To Begin With an Indigenous Legal Citation Style?

In speaking about Indigenizing publishing practices, Wendy Whitebear, a manuscript reviewer at the University of Regina Press, shares: “Indigenous ways of knowing and being should inform the work of publishing. I would like to see a future where this is usual and ordinary, like the pen on your desk.”[59] The work of Gregory Younging is an essential starting point for these discussions as he offers 22 guiding principles for elements of Indigenous style guides.[60] We are guided by the first of such principles, which states that “[t]he purpose of Indigenous style is to produce works that: reflect Indigenous realities as they are perceived by Indigenous Peoples; are truthful and insightful in their Indigenous content; [and] are respectful of the cultural integrity of Indigenous Peoples.”[61]

Throughout the available literature, decolonial citation methods are most often centred around Indigenous oral knowledge. While oral knowledge undoubtedly plays a significant role across Indigenous Laws and Legal Orders, we will also provide a sample of Indigenous citation methods for “extra-intellectual knowledge,”[62] such as personal knowledge and dreams,[63] along with constitutionally significant beadwork.[64] Our discussion seeks to contribute to a more fulsome discussion of culturally appropriate citation practices for all forms of Indigenous Legal Knowledge. While we do so, we are cognizant that across many modes of Indigenous Knowledge transmission, social media, and other forms of digital dissemination and storage have increasingly contributed to cultural resurgence.[65] With this in mind, inclusive legal citation methods require significant digital focus in order to sufficiently uphold Indigenous Knowledge.

Citing Indigenous Oral Knowledge

Review of the Guide in its 9th edition reveals that beginning the process of Indigenous Knowledge inclusion actually requires only slight adaptations of existing citation formats. For example, section 6.10 “Addresses and Papers Delivered at Conferences” already provides some direction on oral knowledge transmission. The Guide suggests the following format:

Speaker, | “title” or Address | (lecture series, paper, or other information | delivered at the | conference or venue, | date), | publication information or [unpublished].[66]

The Guide therefore recognizes that oral transmission of knowledge is not a foreign concept in legal spheres and this could serve as a starting point on which to build more inclusive citation practices that can account for Indigenous Knowledge sources.

Other academic citation manuals such as the APA 7th edition and MLA 8th edition have adopted versions of an Indigenous oral knowledge citation format created by Lorisia MacLeod at NorQuest College Library.[67] MacLeod is a member of the James Smith Cree Nation and one of several Indigenous librarians who are at the forefront of decolonizing libraries and academic information systems.[68] Indigenous citation methods contribute to prioritizing Indigenous voices through the concept of “nothing about us without us.”[69] The original citation format suggested by McLeod is as follows:

Last Name, First Initial., | Nation/Community. | Treaty Territory if applicable. | Where they live if applicable. | Topic/subject of communication if applicable. | Personal communication. | Month, Day, Year.[70]

This citation practice is used when in direct communication with an Elder or Knowledge Keeper, and should be used in consultation with the person providing the information.[71] For example, where the person lives could raise safety concerns, and may or may not be included depending on individual preferences.[72]

Under section 8.9 “Personal Communications,” the APA 7th edition echoes ethical concerns and suggests working with Indigenous peoples in order to ensure the material is appropriate to publish, and the integrity of Indigenous perspectives are upheld.[73] The MLA 8th edition offers similar yet less robust versions of this citation practice, and an Indigenous style guide is being worked on in the Chicago format.[74]

However, across existing citation practices, if oral knowledge is “recoverable by readers” in articles, books, or digital formats, it is suggested that the information be cited in the format of the main source.[75] Applying this practice, an oral teaching from an Elder published in an academic journal would, therefore, forever after, be most appropriately cited as a journal article. The same would be true for any oral knowledge found in a digital format that has an existing citation style.

While citing electronic sources may initially seem like a Eurocentric approach to citation, this would ignore how Indigenous peoples have mobilized digital knowledge acquisition, storage, and sharing.[76] In fact, the digital is beginning to replace or supplement the physical when it comes to Indigenous Knowledge and online sources are innovative and integral pieces to Indigenous cultural resurgence.[77]

The Guide is already poised to include digital Indigenous Knowledge, albeit inexplicitly. In Section 6.19 “Electronic Sources,” the Guide offers fairly robust guidance ranging from websites to podcasts, to social media posts.[78] That being said, there are multiple considerations to assess before, somewhat blindly, incorporating the oral knowledge methods of APA and others into the Guide.

Some scholars have expressed caution in revealing too much Indigenous Knowledge through Western forms of research, making “available through texts what should have never been written down.”[79] In this sense, introducing Indigenous Knowledge into the academic sphere through Indigenous citation methods that later become engulfed in a Western approach may strip oral histories and stories of their significance, and may be culturally inappropriate. In fact, some Indigenous storytellers are so concerned about protecting cultural knowledge from widespread use and appropriation that they recommend copyright be retained before sharing stories.[80] Copyright and intellectual property rights to oral knowledge reflects the need for acknowledgement “based on respect for territorial origins and cultural protocols.”[81] While intellectual property law is not the focus of this paper, it is important to acknowledge the need for responsible stewardship of Indigenous oral knowledge.

The citation of a story presented by Dr. John Borrows reimagined as an Anishinaabe case, entitled Nanabush v Duck, Mudhen and Geese,[82] offers insight into this discussion. An initial approach could be to cite it as the APA citation manual would suggest—simply a pinpoint within an academic journal—as the Guide provides inadequate guidance. Dr. Borrows, meanwhile, proposes his own citation for the teachings formatted as Anishinaabe case law as follows:

Nanabush the Trickster v. Ducks, Mudhen and Geese (Time Immemorial), 004 Ojibway Cases (O.C.) (1st) (Anishinaabe Supreme Court) 40, [hereinafter Nanabush]. G.E. Laidlaw wrote the judgement of John York, Alec Philemon and Rose Holiday concurring, Justice Windigo dissenting. See G. Laidlaw, ‘Ojibway Myths and Tales,’ Twenty-Seventh Annual Archaeological Report 86 (1915); R. Dorson, Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952) at 49.[83]

Although we are unable to determine whether the footnote was included in the bibliography of this article, it demonstrates that, as early as 1997, Indigenous scholars were formulating decolonial legal citation practices. In addition to the proposed citation format, Dr. Borrows also provides an introductory footnote explaining the Neyaashinigmiing origin of the story and offers it to the reader: “John Nadijwon was a friend of my grandfather’s. They often hunted together, and over the years my grandfather shared many stories with him. John told me these stories in this context, and I pass them along in the same way to acknowledge the influence of my grandfather in their continuation.”[84] This demonstrates just one example of how Indigenous Knowledge may be conveyed, and how the footnotes of academic work tell very important stories. In the future, it will be our responsibility to listen to Indigenous authors and peoples we collaborate with for specific ethical considerations when reproducing or transforming oral knowledge.

Citing Indigenous Extra-Intellectual Knowledge

In the section that follows, we will offer insights into citation of Indigenous Extra-Intellectual Knowledge production including, but not limited to, artistic expression, hand work, and beadwork. Unlike oral information, the Guide is silent on citing artistic works. The lack of guidance for citing extra-intellectual knowledge is likely due to the fact that Western legal theory has degraded the legitimacy of laws found outside of written text.[85] Dr. Darcy Lindberg states that:

[T]he continued movement of legal systems towards technical efficiency has created a new aesthetic of Western legal systems. Industrial and decontextualized, it produces rhythms that seem unnatural in comparison to those of the life worlds that give law its purpose. Its new aesthetic is increasingly black letter and dispassionate, an unmelodic reasoning.[86]

This Western approach to legal aesthetics has actively delegitimized and attempted to destroy the aesthetics of Indigenous legal systems.[87]

Meanwhile, Indigenous legal scholars are increasingly incorporating acts of persuasive legal aesthetic as described by Dr. Darcy Lindberg into their academic and legal practices.[88] For example, Métis lawyer Kelly Duquette, from Atikokan, Ontario, incorporates elements of beadwork into her practice of knowledge creation and transfer.[89] Her 2017 work “To Reconciliation Wrongs” includes art of layered acrylic paint, gold leaf, pouring medium, and beadwork on canvas created in parallel with written work exploring questions of Métis participation on juries.[90]

For her part, Dr. Lussier also produced hand work to supplement the written word of her Doctoral Dissertation in law in 2021.[91] Building on the pedagogical practices developed in her dissertation, she teaches a novel Indigenous Legal Traditions Seminar covering the legal significance of beadwork. The unfortunate reality is that works generated by Learners in the course, including Steven, are considered uncitable under the existing Guide. The citation of the works of scholarship such as these are critical to advancing decolonial perspectives in legal education.

While the Guide is devoid of legal aesthetics, the three primary academic citation manuals — APA, MLA, and Chicago — all contain some form of citation format for “visual works.” Visual works are outlined in section 10.14 of the APA Publication Manual, which contains guides for museum artwork, “including paintings, sculptures, photographs, prints, drawings, and installations” along with clip art or stock images and infographics.[92] Very similar citations exist in MLA and Chicago styles, albeit with slight differences. The general formats are produced below:

APA: Artist Last Name, First Initial. | (year). | Title [medium/format]. | Museum, City, State/Country. | URL (if applicable).[93]

MLA: Artist Last Name, First Name. | Title or Description. | Year of Creation | Museum, City. | Title of Website, | URL (if applicable).[94]

Chicago: Artist Last Name, First Name. | Title of Painting. | Year of Creation. | Description of materials. | Dimensions (metric or imperial). | Museum, City. | Accessed Month Day, Year. | URL (if applicable).[95]

Citing Wampum

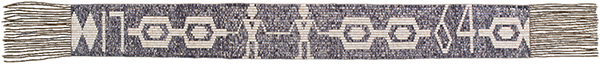

While many forms of Indigenous Extra-Intellectual Knowledge can carry law, there are specific manifestations of Indigenous Law and Indigenous-settler law, such as Wampum, which may require separate citational attention for their constitutional significance. While Wampum has been a form of political and legal communication for over 4,500 years,[96] it has also been an integral tradition between Indigenous and settler peoples since the exchanging of Two Row Wampum/Gaswënta between the Iroquois and Dutch in 1613.[97] As Dr. Penelope Myrtle Kelsey points out, the Gaswënta was precedent setting with “nearly every treaty proceeding from the seventeenth century until the late nineteenth century [beginning] with the European and Six Nations delegates reciting the principles of Two Row.”[98] The creation of new Wampum also forged forward in Treaty relationship building with the British Crown post-1613.[99] In fact, in the process of ratifying and clarifying the Royal Proclamation, 1763,[100] a total of 84 separate Wampum belts were passed between the parties of the Great Council of Niagara.[101] It is impossible to argue the fact that “law lives in beads.”[102]

Covenant Chain Wampum Exchanged at the 1764 Great Council of Niagara (The Crooked Place)[103]

Given the foundational importance of Wampum, any legal citation method would have to account for constitutional, or at the very least, quasi-constitutional status. In section 4.2.5 “Intergovernmental Documents,” the Guide provides citation formats for Indigenous Treaties and Land Claims Agreements.[104] The general form that Treaty and Land Claims follow is as follows:

Title, | date, | pinpoint, | online: | title of the website | <URL> | [archived URL].

We acknowledge that the interpretation, or reading, of Wampum is an intergenerational practice that requires highly specialized training.[105] In Canada, this form of knowledge has been actively disrupted through acts of Wampum dispossession. [106] Therefore, it may be difficult at first to find sufficient information to cite Wampum using the above guide found in section 4.2.5. The existing format could also be adapted to include more information about the parties involved in the Wampum exchange to reclaim the relational aspect of the law contained in the beads. Additionally, all Treaty, Land Claims, and Wampum sources could be moved to Section 2.2 “Constitutional Statutes” to acknowledge their constitutional status. As the conversation around citational politics unfolds, it would be important to hear from Indigenous Wampum keepers on appropriate and ethical citation practices.

Citing Personal Knowledge and Dreams

Across conversations about Indigenous intellectual methodologies, personal knowledge, and dreams contribute integral knowledge.[107] Indigenous Laws and Legal orders are no exception.[108] This is an area where the Guide must start from scratch. This section primarily focuses on dream work contained in some Anishinaabe scholarship that we interacted with in the course of this research. However, we recognize there are unique nuances across Indigenous understandings of dreams and knowledge acquisition,[109] and we hope that this section will prompt a broader conversation.

Citation guides tend to express no need to cite personal knowledge when writing an academic piece. For example, the APA 7th edition suggests that personal knowledge does not require a citation, but personal information about the author, such as the Nation they belong to, could be added in a parenthetical reference.[110] A Western lens may classify knowledge from Dreams as personal and ignore spiritual and legal importance.[111] In fact, Dr. Margaret Kovach states “[t]he proposition of integrating spiritual knowings and processes, like ceremonies, dreams, or synchronicities, which act as portals for gaining knowledge, makes mainstream academia uncomfortable.”[112]

This discomfort in academia has driven scholars such as Dr. Amy Shawanda to infuse citational politics with decolonial Indigenous understandings of Dreams.[113] Citing Dreams is similar to citation practices for oral teachings we explored above; Dreams are co-creations with ancestors.[114] An example of Dreams informing academic works can be found in Kathleen E Absolon’s writing where a Dream of a petal flower later informed the author’s components of Indigenous research methodologies.[115] Similarly, Taryn Michel, a law student at the University of Ottawa, is approaching the study of Canadian jury systems through teachings on trees that have been guided by a Dream.[116]

Dr. Shawanda suggests multiple style formats for citing various forms of Dreams and their contents. We reproduce the generalized format here:

Name of Ancestor in Dream (if applicable) | Topic of Dream | Dream Visitation | Location (if applicable)

Dr. Shawanda explains that “[t]his citation format allows the inclusion of Ancestors from the past and future Spirits, who await in the Great Unknown. For those future Spirits we have not met yet, they can be anyone from a partner, neighbour, unborn children, friends, etc.”[117] Although this citation practice was presented for use in a health-related field using APA referencing, “[d]ream referencing would be supported within any discipline because it allows Indigenous students to incorporate their dreams as part of their own knowledge journey.”[118] With this in mind, we suggest that the Guide should include dreams and other personal knowledge as valuable legal knowledge within the next edition.

Next Steps Towards Decolonizing Legal Citation

In this paper, we have barely scratched the surface of the conversations required to truly decolonize legal citation practices in Canada. Without a doubt, there are countless other forms of Indigenous Legal Knowledge that deserve specific citational attention, and we look forward to exploring those in collaboration with peers and colleagues. We once again acknowledge that this paper is but a small contribution to the pool of existing, ongoing projects to decolonize the Guide. What we hope to have provided is a window into the thought and conscious effort required to acknowledge, take responsibility for, and adapt our shortcomings in citational politics.

Moving forward, we hope this paper and the stories it holds could be used as a primer or conversation starter for the greater project of decolonizing the legal academy generally. As Gregory Younging suggests,[119] it will be important to collaborate with a diverse range of Indigenous folks in order to formulate inclusive and adaptable Indigenous legal citation guides for communities and Nations.

We understand that, as with any moment of learning that challenges the status quo, conscientious citation is a difficult conversation. We have offered a gentle introduction to these ideas, and have demonstrated that, in many cases, such as oral knowledge, the Guide includes citation formats that could be easily modified to ensure Indigenous Knowledge can be properly valorized. Approaching this decolonial project with kindness and a good heart will reveal that being mindful when citing is a responsibility for all who are labouring in legal spheres towards a more just society.

Appendices

Notes

-

[*]

Danielle Lussier, Red River Métis born and raised in the homeland of the Métis Nation on Treaty 1 Territory, is a Beadworker and mum to a trio of tiny Métis. Dr. Lussier served as the inaugural Indigenous Learner Advocate and Director of Community and Indigenous Relations at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law from 2018–2022, and she now serves as Assistant Professor and Academic Director of Indigenous Education Programs at the Royal Military College of Canada.

-

[**]

Steven Stechly, they/them, is a graduate of McGill University and a J.D. candidate at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law. Upon completion of their academic credentials in 2022, they will be articling at the Ottawa office of Gowling WLG in the Advocacy Directorate.

-

[1]

See Lana Ray & Paul Nicholas Cormier, “Killing the Weendigo with Maple Syrup: Anishinaabe Pedagogy and Post-Secondary Research” (2012) 35:1 Can J Native Education 163 at 164.

-

[2]

See Jarrett Martineau & Eric Ritskes, “Fugitive Indigeneity: Reclaiming the Terrain of Decolonial Struggle Through Indigenous Art” (2014) 3:1 Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 at 2.

-

[3]

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation” (2014) 3:3 Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 at 16.

-

[4]

See John Borrows, “Heroes, Tricksters, Monsters, and Caretakers: Indigenous Law and Legal Education” (2016) 61:4 McGill LJ 795 at 802.

-

[5]

Tracey Lindberg, Critical Indigenous Legal Theory (LLD Thesis, University of Ottawa, 2007) at 37 [unpublished].

-

[6]

See Sarah Hunt & Cindy Holmes, “Everyday Decolonization: Living a Decolonizing Queer Politics” (2015) 19 J Lesbian Studies 154 at 161.

-

[7]

Simpson, supra note 3 at 7.

-

[8]

See generally Dwayne Donald, “From What Does Ethical Relationality Flow? An Indian Act in Three Artifacts” in Jackie Seidel & David W Jardine, eds, The Ecological Heart of Teaching: Radical Tales of Refuge and Renewal for Classrooms and Communities (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2016) 10 at 10 (where he explains that human beings are enmeshed in a series of relationships that provide us the ability to live).

-

[9]

See Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Winnipeg: TRCC, 2015) at 3.

-

[10]

Donald, supra note 8 at 11.

-

[11]

Lindberg, supra note 5 at 37–38.

-

[12]

See Aaron Mills, “Aki, Anishinaabek, kaye tahsh Crown” (2010) 9:1 Indigenous LJ 107 at 110.

-

[13]

See Danielle Lussier, Law With Heart and Breadwork: Decolonizing Legal Education, Developing Indigenous Legal Pedagogy, and Hearing Community (PhD Dissertation, University of Ottawa, 2021) [unpublished].

-

[14]

Dr Tracey Lindberg, “Engaging Indigenous Legal Knowledge in Canadian Legal Institutions: Four Stories, Four Teachings, Four Tips, and Four Lessons About Indigenous Peoples in the Legal Academy” (2019) 50:3 Ottawa L Rev 119 at 124–25.

-

[15]

9th ed (Toronto: Thomson Reuters, 2018) [McGill Guide].

-

[16]

Lussier, supra note 13 at 186.

-

[17]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, supra note 9 at 3.

-

[18]

Ibid at 5–6.

-

[19]

Jeffery G Hewitt, “Decolonizing and Indigenizing: Some Considerations for Law Schools” (2016) 33:1 Windsor YB Access Just 65 at 69.

-

[20]

See Kyle Powys Whyte & Sarah Hunt, “The Politics of Citation: Is the Peer Review Process Biased Against Indigenous Academics?” (last modified 24 August 2018), online (podcast): CBC <cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/decolonizing-the-classroom-is-there-space-for-indigenous-knowledge-in-academia-1.4544984/the-politics-of-citation-is-the-peer-review-process-biased-against-indigenous-academics-1.4547468>.

-

[21]

Ibid. See also Carrie Mott & Daniel Cockayne, “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation Toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement’” 24:7 Gender, Place & Culture 954.

-

[22]

See American Psychological Association, Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th ed (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2020), s 8.36 [APA].

-

[23]

See Nicolas Labbé-Corbin, “A Word from the Editor” in McGill Guide, supra note 15.

-

[24]

See McGill Faculty of Law, News Release, “Kerry Sloan to Join the Faculty of Law as Assistant Professor in 2019” (29 May 2018), online: McGill University <mcgill.ca/law/channels/news/kerry-sloan-287401>.

-

[25]

See Jack Healy, “Tribal Elders are Dying From the Pandemic, Causing a Cultural Crisis for American Indians”, New York Times (12 January 2021), online: <www.nytimes.com/2021/01/12/us/tribal-elders-native-americans-coronavirus.html>.

-

[26]

Charles Kamau Maina, “Traditional Knowledge Management and Preservation: Intersections with Library and Information Science” (2012) 44:1 Intl Information & Library Rev 13 at 13.

-

[27]

McGill Guide, supra note 15 at E-3.

-

[28]

Patricia Monture-Angus, “Standing Against Canadian Law: Naming Omissions of Race, Culture and Gender” (1998) 2:1 YB NZ Jurisprudence 7 at 9.

-

[29]

[1997] 3 SCR 1010, 153 DLR (4th) 193 [Delgamuukw].

-

[30]

However, the court actually relied on earlier precedence from Simon v The Queen, [1985] 2 SCR 387, 24 DLR (4th) 390 (here Justice Dickson stated that disregarding oral histories would “impose an impossible burden of proof” at 408).

-

[31]

Delgamuukw, supra note 29 at para 87.

-

[32]

See Heather J Shotton et al, “Living Our Research Through Indigenous Scholar Sisterhood Practices” (2018) 24:9 Qualitative Inquiry 636 at 639.

-

[33]

Shawn Wilson, Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2008) at 58.

-

[34]

Hewitt, supra note 19 at 70.

-

[35]

See Larry Chartrand, “The Story in Aboriginal Law and Aboriginal Law in the Story: A Métis Professor’s Journey” (2010) 50 SCLR (2d) 89 at 96–97.

-

[36]

See Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed (London, UK: Zed Books Ltd, 2012) at 61.

-

[37]

Shotton et al, supra note 32 at 639.

-

[38]

See James (Sákéj) Youngblood Henderson, “Postcolonial Ghost Dancing: Diagnosing European Colonialism” in Marie Battiste, ed, Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000) 57 at 65.

-

[39]

Lindberg, supra note 5 at 10–12.

-

[40]

See also Adam Gaudry & Danielle Lorenz, “Indigenization as Inclusion, Reconciliation, and Decolonization: Navigating the Different Visions for Indigenizing the Canadian Academy” (2018) 14:3 AlterNative 218. See generally Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Indigenous Resurgence and Co-Resistance” (2016) 2:2 Critical Ethnic Studies 19.

-

[41]

See Paulina R Johnson, “Indigenous Knowledge Within Academia: Exploring the Tensions That Exist Between Indigenous, Decolonizing, and Nêhiyawak Methodologies” (2016) 24:1 U Western Ontario J Anthropology 44 at 56.

-

[42]

See Gaudry & Lorenz, supra note 40 (we suggest the reader visit this work to gain more information on a variety of approaches to Indigenization and Decolonization).

-

[43]

Shawn Wilson, Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2008) at 80.

-

[44]

Shotton et al, supra note 32 at 637.

-

[45]

See Gregory Younging, Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing by and About Indigenous Peoples (Edmonton: Brush Education Inc, 2018) at 39.

-

[46]

See Margaret Kovach, Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009) at 12.

-

[47]

Younging, supra note 45 at 43.

-

[48]

Ibid at 39.

-

[49]

Ibid.

-

[50]

Ibid at 31.

-

[51]

Daniel Heath Justice, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018) at 242.

-

[52]

See e.g. Chartrand, supra note 35. See also Tracey Lindberg, “What do you Call an Indian Woman with a Law Degree? Nine Aboriginal Women at the University of Saskatchewan College of Law Speak Out” (1997) 9 CJWL 301; Monture-Angus, supra note 28.

-

[53]

Eve Tuck, K Wayne Yang & Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández, “Citation Practices Challenge” (April 2015), online: Critical Ethnic Studies <criticalethnicstudiesjournal.org/citation-practices>.

-

[54]

Whyte & Hunt, supra note 20 at 00h:07m:50s.

-

[55]

Ibid at 00h:09m:00s.

-

[56]

Ibid at 00h:06m:05s.

-

[57]

See Carrie Mott & Daniel Cockayne, “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation Toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement’” 24:7 Gender, Place & Culture 954 at 955.

-

[58]

Ibid.

-

[59]

Younging, supra note 45 at 5.

-

[60]

Ibid at 99–104.

-

[61]

Ibid at 6.

-

[62]

Wilson, supra note 33 at 58.

-

[63]

See e.g. Amy Shawanda, “Baawaajige: Exploring Dreams as Academic References” (2020) 1:1 Turtle Island J Indigenous Health 37.

-

[64]

See e.g. Angela M Haas, “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice” (2007) 19:4 Studies in American Indian Literatures 77.

-

[65]

See e.g. National and State Libraries Australasia, “Born Digital 2016: Indigenous Voices with Dr. Rachael Ka’ai-Mahuta” (8 August 2016), online (video): YouTube <youtube.com/watch?v=QDocFXLhOCI&feature=emb_logo>; Marcia Nickerson & Jay Kaufman, “Aboriginal Culture in a Digital Age” (July 2005), online (pdf): KTA Centre for Collaborative Government <kta.on.ca>.

-

[66]

McGill Guide, supra note 15 at E-97 [emphasis in original].

-

[67]

See NorQuest College, “Indigenous 101: Decolonizing the Library” (7 June 2019), online: <www.norquest.ca/media-centre/featured-stories/indigenous-101-decolonizing-the-library.aspx>.

-

[68]

Ibid.

-

[69]

Ibid.

-

[70]

See Theresa Bell, “How Should I Cite Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers?” (20 December 2019), online: Royal Roads University <writeanswers.royalroads.ca/faq/202367>.

-

[71]

See Centre for Teaching Learning and Technology, “Decolonizing Citations Workshop” (2 November 2020) at 00h:40m:09s, online (video): YouTube <www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSqkdo91gn8&feature=youtu.be>.

-

[72]

Ibid at 00h:44m:34s.

-

[73]

APA, supra note 22 at 260–61.

-

[74]

See Bronwen McKie, “Decolonizing Citations: Help Xwi7xwa Create a Template for Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers in Chicago Style” (1 September 2020), online: Indigenous Research Support Initiative <irsi.ubc.ca/blog/decolonizing-citations-help-xwi7xwa-create-template-citing-indigenous-elders-and-knowledge>.

-

[75]

APA, supra note 22 at 261.

-

[76]

NorQuest College, supra note 67.

-

[77]

National and State Libraries Australasia, supra note 65 at 00h:02m:42s.

-

[78]

McGill Guide, supra note 15 at E-102 to E-105 (although there could be slightly more guidance on Instagram posts).

-

[79]

Johnson, supra note 41 at 56.

-

[80]

See Jo-ann Archibald, Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008) at 145.

-

[81]

Ibid at 146.

-

[82]

See John Borrows, “Living Between Water and Rocks: First Nations, Environmental Planning and Democracy” (1997) 47:4 UTLJ 417 at 456 (for context this is a case about Anishinaabe legal consequences for poor environmental management).

-

[83]

Ibid.

-

[84]

Ibid.

-

[85]

See Darcy Lindberg, “Miyo Nêiyâwiwin (Beautiful Creeness): Ceremonial Aesthetics and Nêhiyaw Legal Pedagogy” (2018) 16/17:1 Indigenous LJ 51 at 53.

-

[86]

Ibid at 54.

-

[87]

Ibid; See Penelope Myrtle Kelsey, Reading the Wampum: Essays on Hodinöhsö:ni’ Visual Code and Epistemological Recovery (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014) at xiv.

-

[88]

Lindberg, supra note 85 at 55.

-

[89]

Kelly Duquette, “About Me” (last visited 23 October 2021), online: Kelly Duquette Art <www.kellyduquetteart.com/about/>.

-

[90]

See Kelly Duquette, “To Reconciliation Wrongs” (2017), online: Kelly Duquette Art <www.kellyduquetteart.com/work#/portfolio/>.

-

[91]

See “Canada’s First PhD in Law Delivered Partly in Beadwork” (28 May 2021), online: University of Ottawa Gazette <www.uottawa.ca/gazette/en/news/canadas-first-phd-law-delivered-partly-beadwork>.

-

[92]

APA, supra note 22 at 346.

-

[93]

Ibid.

-

[94]

See “How to Cite a Painting or Artwork in APA, MLA or Chicago” (last modified 21 September 2021), online: EasyBib <www.easybib.com/guides/citation-guides/how-do-i-cite-a/how-to-cite-a-painting-you-see-in-person-or-online>.

-

[95]

Ibid.

-

[96]

See Lois Elizabeth Edge, My Grandmother’s Moccasins: Indigenous Women, Ways of Knowing and Indigenous Aesthetic of Beadwork (PhD Thesis, University of Alberta, 2011) [unpublished] at 137.

-

[97]

Kelsey, supra note 87 at 2.

-

[98]

Ibid at 4.

-

[99]

See Nathan Tidridge, The Queen at the Council Fire: The Treaty of Niagara, Reconciliation, and the Dignified Crown in Canada (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2015) at 58–59.

-

[100]

See George R, Proclamation, 7 October 1763 (3 Geo III), reprinted in RSC 1985, App II, No 1.

-

[101]

Tidridge, supra note 99 at 59.

-

[102]

Lussier, supra note 13 at 289.

-

[103]

See Wampum belt, 1764 Niagara Covenant Chain (reproduction). Ken Maracle. Canadian Musuem of History, LH2016.48.2, IMG2016-267-250. The Covenant Chain, 1764, Exchanged between the Algonquins, Chippewas, Crees, Fox, Hurons, Pawnees, Menominees, Nippisings, Odawas, Sac, Toughkamiwons, Potwatomies, Cannesandagas, Caughnawagas, Cayugas, Conoys, Mohicans, Mohawks, Nanticokes, Onondagas, Senecas & the British Crown. See also “The Covenant Chain, Royal Proclamation and Treaty of Niagara” (last visited 21 March 2022), online: Canadian Museum of History <www.historymuseum.ca/history-hall/covenant-chain-royal-proclamation-treaty-niagara>.

-

[104]

McGill Guide, supra note 15 at E-64.

-

[105]

See Ruth Buchanan & Jeffrey G Hewitt, “Treaty Canoe” in Jessie Hohmann & Daniel Joyce, eds, International Law’s Objects (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018) 491 at 501.

-

[106]

Kelsey, supra note 87 at xiv.

-

[107]

See generally Jean-Guy Goulet, “Dreams and Visions in Other Lifeworlds” in David E Young & Jean-Guy Goulet, eds, Being Changed: The Anthropology of Extraordinary Experience (Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd, 1994) 16.

-

[108]

See John Borrows, Drawing Out Law: A Spirit’s Guide (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010).

-

[109]

See e.g. Deborah McGregor, “Coming Full Circle: Indigenous Knowledge, Environment, and Our Future” (2004) 28:3/4 American Indian Q 385 at 388.

-

[110]

APA, supra note 22 at 260–61.

-

[111]

Shawanda, supra note 63 at 39.

-

[112]

Kovach, supra note 46 at 67.

-

[113]

Shawanda, supra note 63.

-

[114]

Ibid at 41.

-

[115]

See Kathleen E Absolon (Minogiizhigokwe), Kaandosswin: How We Come to Know (Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2011).

-

[116]

Taryn Michel, Michipicoten First Nation, Ottawa, Ontario, Tree Teachings, Personal Communication (2020). The authors recognize that even in the process of publishing this article, we were confronted with the inadequacy of the Guide and were required to fit this knowledge into the “Interview” format contained in the Guide, which does not fully capture the relational exchange of knowledge that occurred in the conversation. See McGill Guide, supra note 15 at E-100.

-

[117]

Shawanda, supra note 63 at 43.

-

[118]

Ibid at 45.

-

[119]

Younging, supra note 45 at 39.

List of figures

Covenant Chain Wampum Exchanged at the 1764 Great Council of Niagara (The Crooked Place)[103]