Abstracts

Abstract

In this essay I argue that in order to understand debates in jurisprudence one needs to distinguish clearly between four concepts: validity, content, normativity, and legitimacy. I show that this distinction helps us, first, make sense of fundamental debates in jurisprudence between legal positivists and Dworkin: these should not be understood, as they often are, as debates on the conditions of validity, but rather as debates on the right way of understanding the relationship between these four concepts. I then use this distinction between the four concepts to criticize legal positivism. The positivist account begins with an attempt to explain the conditions of validity and to leave the question of assessment of valid legal norms to the second stage of inquiry. Though appealing, I argue that the notion of validity cannot be given sense outside a preliminary consideration of legitimacy. Following that, I show some further advantages that come from giving a more primary place to questions of legitimacy in jurisprudence.

Résumé

Dans cet essai, je soutiens qu’afin de comprendre les débats en théorie du droit, il faut bien distinguer les quatre concepts suivants : la validité, le contenu, la normativité, et la légitimité. Je démontre que cette distinction nous aide d’abord à comprendre les débats fondamentaux en théorie du droit entre les positivistes et Dworkin : nous ne devrions pas comprendre ces débats, comme certains le font, comme des débats sur les conditions de la validité ; ils portent plutôt sur la bonne façon d’apprécier la relation entre ces quatre concepts. Ensuite, je me sers de cette distinction entre les quatre concepts pour critiquer le positivisme juridique. Le récit positiviste essaie d’abord d’expliquer les conditions de la validité, pour ensuite repousser la question de l’évaluation des normes juridiques valides à la deuxième étape de l’analyse. L’idée est intéressante, mais j’affirme toutefois que la notion de validité ne peut avoir de sens qu’après avoir considéré la notion de légitimité dans un premier temps. Suivant cette discussion, j’identifie quelques-uns des avantages additionnels liés au fait d’accorder une place plus primaire aux questions de légitimité en théorie du droit.

Article body

Introduction

The debates between legal positivists and Ronald Dworkin loom large over contemporary jurisprudence. And yet, these are unusual debates. Dworkin is one of the leading legal philosophers of the last fifty years, who has been engaged in debates extending over decades with other legal philosophers and whose work has been the subject of voluminous commentary. At the same time Dworkin is an outsider of sorts to the field, not hiding his view that he finds much of the work in it uninteresting, even fundamentally misguided. Other legal philosophers in their turn have expressed a similarly ambivalent attitude toward his work, often questioning the importance and quality of his work[1] and even whether he should be considered to belong among their ranks.[2] Yet despite this ambivalent attitude, legal philosophers keep returning to his work. Legal positivists in particular are almost uniform in taking Dworkin’s arguments to be both the most significant challenge to their position and at the same time (almost) wholly unsuccessful.

If I venture down these well-trodden paths of the debate between Dworkin and the legal positivists yet again it is in order to explain the source of this odd state of affairs. I will argue that it is grounded in different understandings of legal theory, and in particular of the right way to characterize the relationship between four fundamental concepts: validity, content, normativity, and legitimacy. I will argue that legal positivists have understood the relationship between these concepts in one way and have erroneously assumed that Dworkin holds a similar view of their relationship. Relying on this point I will develop along the way an argument against legal positivism that is different from what is found in Dworkin’s work.

Though I will discuss some aspects of Dworkin’s work in some detail, I should stress that my concern is not primarily with his work. However, the centrality of the debate between legal positivists and Dworkin and his followers in contemporary jurisprudence makes Dworkin’s work difficult to ignore and serves as useful basis for illustrating my own argument. In the end, I do not particularly care whether what I say here is a faithful presentation of Dworkin’s views or to what extent it captures what he would consider the core of his ideas. This should be clear from the fact that I ignore here many of the elements that are central to Dworkin’s work in jurisprudence (for example, interpretive concepts, integrity, the distinctions between rules, principles and policies, the distinction between fit and justification, the view that political morality is grounded in equal concern and respect, Dworkin’s arguments against what he called “Archimedeanism”, the semantic sting, the chain novel and so on). Dworkin’s views on these matters, with which I do not necessarily agree, are irrelevant for either highlighting what I take to be the fundamental difference between positivist theories and Dworkin’s or for bringing out what I take to be the central flaw in positivist theories.

I will start, nonetheless, with Dworkin’s critique of legal positivism. Already in 1964 Ronald Dworkin opened one of his earliest published works with the following words: “What, in general, is a good reason for decision by a court of law? This is the question of jurisprudence; it has been asked in an amazing number of forms, of which the classic ‘What is Law?’ is only the briefest.”[3] Some twenty years later Dworkin expressed a similar idea when he said that “[t]he central problem of analytical jurisprudence is ... [w]hat sense should be given to propositions of law?”[4] Shortly afterwards, Dworkin entitled the opening chapter of Law’s Empire “What is Law?”, a question that matters, he immediately explained, because “[i]t matters how judges decide cases.”[5] And recently, some forty years after his early essay, Dworkin made essentially the same point when he said that his main concern is understanding what law is “in what I shall call the doctrinal sense,” namely in “what the law requires or prohibits or permits or creates.”[6]

It is thus already at the very first lines of the article published in 1964, before Dworkin’s first direct attacks on Hart’s positivism and long before the supposed radical shift in views that came with his turn to interpretivism,[7] that others concerned with the question “what is law?” should have begun to be puzzled by Dworkin’s approach. For on its face it seems odd to say that “what is law?” is only a shorter way of saying “what is a good reason for deciding a case?” or “how should a court decide this particular case?” Not only do these sentences seem to have utterly different meanings, it does not even seem that answering the first question is particularly helpful in answering the second. It is usually thought that an answer to the question “what is law?” should look something this: “law is the set of rules in which a state determines certain permissions, prohibitions and other normative requirements that govern the lives of those under its jurisdiction.” This suggestion is no doubt incomplete and vague, but it does not seem that any elaboration or clarification on any of its elements would give us anything that is going to be helpful in answering the question of how cases should be decided. For this we need to know the content of the rules in a given jurisdiction, as well as a theory of adjudication or a theory of interpretation. And though such theories are probably going to be related in some way to a theory of law, they do not look like the same thing at all.

This is indeed how many legal positivists reacted to Dworkin’s work, and I believe much of the disagreement with, even incomprehension of, Dworkin’s views stems from failure to understand in what sense the question “what is law?” is similar to Dworkin’s question “how should judges decide cases?” To see how these two questions are related, why Dworkin is not guilty of such a basic error that it thwarts his theory right from the start, and therefore why many legal positivists’ replies to Dworkin miss their target, we must look more closely at the building blocks of jurisprudential inquiry.

I. Four Concepts of Legal Theory

My contention is that Dworkin’s concerns are not very different from those of other legal philosophers, including legal positivists. But I hope to show that while the questions he is interested in are similar, the way Dworkin answers them is radically different; and so the nature of the challenge he puts to legal positivism is not just that he thinks the answer they give to the question “what is law?” is wrong. Rather, legal positivists are wrong in the way they go about answering it.

To see why positivists are wrong, we need to distinguish between four different concepts: the validity of legal norms, the content of legal norms, the normativity of law, and the legitimacy of law. A legal norm is said to be valid if and only if it is a member of a class of norms that can be identified (in some yet unspecified way) as belonging to a certain legal system. The validity of a legal norm is what explains why it is a legal norm (as opposed to a social or moral norm). The content of a legal norm is what that norm prescribes, proscribes, empowers, and so on, usually by linking certain sets of facts that have to obtain (signing certain documents; earning certain amount of money) to certain legal outcomes (the creation of certain contractual rights and duties; the duty to pay a certain amount of tax). The normativity of a legal norm is the sense in which the legal responses just mentioned are “non-optional”,[8] the way in which legal norms create (or purport to create) obligations that people take or refrain from taking certain actions. Finally, legitimacy is concerned with the question of when an issuer of putative legal norms is entitled to make such demands. Though normativity and legitimacy are obviously related—and on some accounts, inseparable—they seem to address two distinct issues: normativity deals with the metaphysical question, “how could a social, factual, practice, create norms?”, that is, it tries to explain what has to be the case for a social practice such as law to, even in principle, create obligations; by contrast, legitimacy deals with the moral or political question, “what gives any particular putative law-maker the right to demand that one should, prima facie, obey?” Another way of putting the difference is that the question of normativity asks “how are legal obligations possible?”, whereas the political question of legitimacy asks “what political conditions need to be in place for law to bind those subject to it?”

Clarifying these concepts is important because it will help us see where positivists have often misunderstood Dworkin’s arguments. As we shall see, Dworkin is sometimes taken to be making claims about validity, when in fact his main concern has always been with the question of content, and ultimately of legitimacy. More generally, with the aid of these four concepts it is easier to identify and articulate more sharply the differences between different legal theories on both abstract questions like “what is law?” and on smaller-scale questions like whether every legal system contains a rule of recognition.

II. The Mistaken Positivistic Readings of Dworkin

Positivists disagree among themselves on many questions, but as a first cut what unites all of them is that they treat the question of validity as prior to and distinct from the question of content. And they often assume that this picture is shared by all legal theorists. Thus, for example, Andrei Marmor presents the positivist methodological suppositions as though they are uncontroversial starting points shared by all legal theorists: the goal of “[c]ontemporary legal theories”, he writes, is “to understand the general conditions which would render any putative norm legally valid”; only secondarily are they also “interest[ed] in the normative aspect of law.”[9] Following this approach critics of Dworkin either assume that Dworkin accepts this formulation but holds different views on validity (roughly that he thinks morality always belongs among the conditions of validity), or criticize him for failing to see the need to describe law prior to engaging in normative analysis of it.[10]

As a result, Dworkin’s argument against positivism has often been misunderstood. Here is, for example, how Marmor describes Dworkin’s argument against positivism:

[Dworkin] denies that the criteria employed by judges and other officials in determining what counts as law are rule governed, and thus he denies that there are any rules of recognition at all. But as far as I can see, Dworkin’s argument is based on a single point, which is rather implausible. He argues that it cannot be the case that in identifying the law judges follow rules, because judges often disagree about the criteria of legality in their legal systems, so much so, that it makes no sense to suggest that there are any rules of recognition at all; or else, the rules become so abstract that it becomes pointless to insist that they are rules.

The problem is this: To show that there are no rules of recognition, Dworkin would have had to show that the disagreements judges have about the criteria of legality in their jurisdiction are not just in the margins; that they go all the way down to the core. But this is just not plausible. Is there any judge in the United States who seriously doubts that acts of Congress make law? Or that the U.S. Constitution prevails over federal and state legislation?[11]

I think this is a mistaken reading of Dworkin’s argument, and it stems from the tendency to think that Dworkin’s critique of positivism was limited to the right test of legal validity. It is true that disagreements form a central component of Dworkin’s argument against positivists. No one, however, doubts that American judges consider acts of Congress to be sources of law (or that acts of Congress “make law”), and Dworkin never said anything to suggest otherwise. Nonetheless, this quotation from Marmor helps identify two issues that Dworkin is concerned with and about which his view is different from that of legal positivists. The first is what gives Congress the law-making power that it has, or, to take another example, why the words written on those ancient parchments lodged in the National Archives in Washington are thought to determine (or are considered relevant to) issues judges are concerned with today. Positivists answer that this is because of the existence of a social rule, which Hart dubbed “the rule of recognition”; Dworkin rejects this answer. The second question is what those congressional acts (which judges agree on their relevance for their job) mean. It is this—the content of those congressional acts—that Dworkin argued is deeply contested among lawyers, and it is this disagreement that Dworkin argued legal positivism, of whatever stripe, cannot explain. For Dworkin, these two issues are closely related, and when put together we can understand the positivists’ failure. To put the matter briefly, the reason why the positivist answer fails as an answer to the first question is because it does not give a satisfactory response to the second question.

Much of the discussion of Dworkin’s work has misunderstood this point because, just like the quote above, it assumed that Dworkin’s arguments were concerned with validity. But there has also been a response to Dworkin’s position that addressed it head-on: Dworkin may be interested in questions of content, but these are questions about how judges should decide cases; that is, this is all part of a theory of adjudication. These questions are indeed steeped in political suppositions, about which different legal systems (and judges) hold different views, but it is for this reason exactly that they are not part of the domain of “general” jurisprudence. Joseph Raz’s comment that Dworkin offered a theory of adjudication, which he “regard[ed] ... willy-nilly and without further argument as a theory of law”[12] is representative of this line of criticism, but probably the most popular way of making this point is to say that Dworkin failed to distinguish between the question “what is law (in general)?” and the question “what is the law (applicable in a particular case)?”[13]

According to this line of criticism, before we decide what judges should do with the law, that is, before we turn to adjudication (or its theory), we need an account on what law is, or else we cannot know what materials are relevant for deciding the question. Indeed, the critics contend, Dworkin’s protestations to the contrary notwithstanding, his account must presuppose some answer to this question, some account of validity. And on this point the most convincing account remains that offered by legal positivists, specifically something like Hart’s rule of recognition. In fact, as some legal theorists have added mischievously, upon close inspection it turns out that Dworkin is a closeted legal positivist.[14] I think this line of argument, though very popular, is mistaken.

III. Legal Validity and Its Problems

The positivist approach to explaining law looks at first quite plausible: to know how to decide a case we must first identify the legal norm that governs the case, and to know that we need to know how to identify legal norms in general. And the way positivists fill in the details of this general approach also seems straightforward: it seems natural to say that there are certain law-making properties that make something into law regardless of whether these legal norms are part of contract law, competition law, or constitutional law, in short, regardless of their content. It seems to follow that identifying legal norms then calls for identifying those law-making properties. Since these properties do not depend on their content, they must then be related to their source and, by implication, to their method of promulgation. After all, this seems to be the only thing common to all the things we call “English law” or “French law”.

This is the essence of the positivist rationale for separating a legal norm’s validity from its content and for focusing their attention on the former. Many positivists have also argued that we can understand in what way a legal norm is binding (“non-optional”) independently of its content. On this view it is not what the law requires that makes it binding; rather, it is the fact that it is the law that makes it binding.[15] In this way the question of normativity is tied to the question of validity, but is separated from the question of content. At the same time, this account of the normativity of law is kept distinct from the question of whether we should follow the law—a matter about which (in the positivist picture) the identification of valid legal norms tells us nothing.

But despite the initial appeal of this approach, closer inspection reveals serious difficulties with it. Take the distinction between validity and content first. To make sense of this distinction it would be helpful to think of legal norms as closed boxes. The content of the norm, that is, what it requires, is found inside the box, whereas its validity is some mark outside the box by which we can identify it without having to look inside the box to examine its content. Now there are two ways of understanding the positivist claim. According to the first, the mark identifies those things that are legal norms, but it cannot identify which norm is applicable to which case, since this is already a question dealing with the norm’s content, and as such this is something that identifying the mark of legal norms cannot tell us. According to the second, validity is the test for identifying the sources of legal norms, not the legal norms themselves. Here, to continue with the box analogy, the rule of recognition does not identify any individual box but tells us where the boxes might be.

Different positivists, sometimes even the same theorist in different places, seem to vacillate between these two theses. At times we are told that with the rule of recognition “both private persons and officials are provided with authoritative criteria for identifying primary rules of obligation”[16] in a particular jurisdiction; in another formulation, “[t]o say that a given rule is valid is to recognize it as passing all the tests provided by the rule of recognition and so as a rule of the system.”[17] This view is also behind Hart’s claim that the rule of recognition is introduced as a solution to the problem of knowing what the law requires. Whether or not Hart meant his account of the emergence of secondary rules to represent some historical event, on this view it is clear that the point of the rule of recognition is to identify valid legal norms, as they are applicable to particular cases.

The problem with this approach is that it is hard to see how a test that looks to the procedures of promulgation, as the rule of recognition is understood to be, could identify individual legal norms; or, put in the terms distinguished above, how one could identify legal norms without looking at their content. No formal test (even a highly complex one) could alone tell us how to identify the individual cases to which particular legal norms apply. For this we must add an account that explains how to move from the identification of something as belonging to the group of legal norms to knowing the content of individual legal norms.[18] The main problem with this approach may be put as follows: the image of norms as boxes, with the rule of recognition identifying the legal ones, is misleading, because the law is not made up of discrete units of normative requirements ready to be identified and applied to individual cases. Indeed, given that what counts as an individual legal norm may be identified only by the scope of cases it covers, it is unclear how any meaningful distinction between a single, valid, legal norm and its content is even possible.

I cannot deal with this difficulty here in detail, but I believe none of the (few) attempts to address it has been successful. If I am right about this then this version of legal positivism suffers from a problem more fundamental than the one ascribed to it by Dworkin: as already mentioned, Dworkin’s best known argument against legal positivism is, roughly, that it cannot explain the existence of prevalent disagreements about the content (not validity) of legal norms among lawyers in non-marginal cases. But we now see that the problem is not so much the existence of fundamental disagreements about the content of legal norms, but that of identifying their content in the first place. Even if there were no disagreements among lawyers at all, this interpretation of legal positivism would offer an implausible account of law in suggesting that with the identification of the mark of validity of legal norms we can also identify individual legal norms applicable to particular cases.

Perhaps recognizing these difficulties, legal positivists seem increasingly more sympathetic to the other interpretation of validity mentioned earlier. According to this view the positivist notion of validity—and the corresponding rule of recognition—is not supposed to give judges a procedure for deciding cases or even for identifying legal norms.[19] Rather, on this view what the rule of recognition recognizes are the relevant sources for knowing what the law requires. Hart, for example, seems to have moved toward this view in the postscript to The Concept of Law, where he wrote that the rule of recognition “identif[ies] the authoritative sources of law.”[20] Legal positivism on this view is not based on the possibility of identifying individual valid legal norms, but on the identification of the marks of validity, which themselves cannot identify valid legal norms. (Notice that on this version of legal positivism what drives the distinction between law and morality is not so much a substantive claim, but rather a methodological one: if one wishes to understand a certain phenomenon, it is helpful to see in what ways it is different from similar things.[21])

This version of legal positivism seems more plausible than the previous one, simply because it is not faced with the challenge of explaining how any test of validity could identify individual legal norms. A further advantage of this approach is that it seems to answer Dworkin’s arguments: because his arguments against positivism are about content, limiting the scope of the positivist thesis in this way seems to imply that Dworkin’s arguments are incapable of hitting their intended target. But these advantages come at a great cost. This version of legal positivism turns out to be seriously incomplete, for here is a supposedly descriptive theory of law that says nothing on how to fill the gap between identifying the sources of legal norms and identifying legal norms. In other words it is a theory of law that, by its proponents’ own admission, is silent on the question that most people who come into contact with the law care most about: what it requires and how one could get to know this.

A positivist might respond that she has other things to say about these questions, which may or may not be logically related to her legal positivism. But as I will try to show now, this position is not just incomplete; even in this weakened form the account it offers is unsuccessful. Even if it is not challenged by the problem of legal content, it can be challenged by the concept of legitimacy.

IV. The Place of Legitimacy in Legal Theory

A. The Positivist Framework

The “rule of recognition” stands for at least two ideas. The first is that there are limits to the law, and correspondingly that when legal decision-makers decide according to law they cannot use certain sources that they might have available to them had they sought to answer the question in their personal capacity.[22] This view by itself, however, is consistent with many non-positivist views. The more significant claim is that every legal system contains a social rule (or rules) necessary for identifying legal rules, and that this rule is the reason why, at a minimum, certain officials follow the law.[23] As we have seen, there is some ambiguity in positivist writings with regard to what it is that the rule of recognition recognizes. In what follows I will assume it is the weaker thesis, according to which the rule of recognition recognizes the sources of legal norms. Typically, in a legal system we can distinguish between mandatory sources (for example, statutes, precedents), permissible but non-binding sources (judgments of other jurisdictions, academic writings, and so on), and still other materials that are completely impermissible (for example, in some jurisdictions, public opinions on the case).[24] Is it not clear that Hercules, and if not him then at least the mere mortals who decide legal disputes in our world, implicitly rely on such a social rule?

The view presupposed by this question is a combination of three propositions: first, that the rule of recognition is concerned with the identification of the sources of legal norms; second and correspondingly, that legal positivism is a thesis about validity, not content; and third, that the social fact of agreement on what things count as sources of law (even if there is disagreement on what makes it the case that they are sources of law) is sufficient for the existence of a rule of recognition, and in turn for the existence of law.[25] Taken together these propositions aim to show that the question of the identification of legal sources is a matter of social fact, and does not (necessarily) depend on moral or political considerations. This view would turn out to be false if it were shown that questions of legitimacy affect even the determination of the sources of law.

The weight of argument falls, of course, on the third proposition. As I see it there are two possible strategies for trying to make good on the claim of separation between validity and legitimacy. The first strategy attempts to do so by effectively eliminating the question of legitimacy. In the book The Vocabulary of Politics by T. D. Weldon, an Oxford philosopher and a contemporary of Hart, one finds the following: “‘Why should I obey the laws of England?’ is the same sort of pointless question as ‘Why should I obey the laws of cricket?’ ... The chief source of trouble is a verbal confusion which tends to infect our talk about ‘law’ both in its scientific and its political usage.”[26] On this view once we understand the vocabulary of “valid” legal norms there is no further question—apparently not even a political one—to answer. To look for anything deeper in a social obligation is akin to looking for a ghost in the machine (to borrow from Gilbert Ryle, one of this approach’s leading proponents).

There are some hints of this view in Hart’s discussion of the “gunman situation”,[27] but ultimately I do not think this represents his view.[28] We need not spend too much time on this exegetical question because I believe few today would consider this approach very promising, and as a result the attempt to reduce the question of legitimacy to the question of normativity seems misguided, at least in the manner Hart on this interpretation proposed to do it. (A further problem with this approach in the context of law, even if we accept the linguistic approach in certain other contexts, is explaining the way law imposes obligations on others. Even if we had been willing to accept the view that through attention to language and with the aid of speech act theory we can solve all philosophical questions surrounding, say, the practice of promising, it is more difficult to see how such an approach could help us with obligations imposed by the law.)

The other approach seeks to deny the relevance of questions of legitimacy to jurisprudence. Raz’s approach to the question of legitimacy serves as an example. Raz’s “normal justification thesis” is the basis for his distinction between de facto and legitimate authority. Raz argues that authority (including the authority of law) is justified so long as one is more likely to conform to reasons one has by following the authority than by not.[29] Roughly, what typically justifies law is that it provides guidance such that those subject to it are more likely to act in accordance with reason than if they tried to decide how to act on their own devices. The crucial point is that this moral assessment is conducted independently of the law, “before” the law if you will, and it is largely unaffected by law. To be sure, law or social norms may add “conventional” wrinkles to under-determinate moral requirements (the speed limit could be set at 50 or 55; elections could take place every four or five years), but even this is a matter that leaves morality itself untouched and separate from law. This is ultimately why it follows from such an account that there is no general obligation to obey the law. An obligation to obey the law depends on whether the conditions of the normal justification thesis are satisfied, something that is determined based on a particularistic determination both of what is required and of whom the legal demand is directed at.[30] As such it cannot give rise to any general obligation.

Translating this to the terminology developed above, the question of legitimacy is tied to the question of content, but kept apart from the other two concepts, validity and normativity (which, as we have seen, are themselves linked to each other). An implication of the link between content and legitimacy is that the question of legitimacy is not, strictly speaking, a question of analytic jurisprudence (as the term is understood by legal positivists). As legitimacy hangs primarily on the content of law, and as content is a contingent matter on which legal systems differ, these subjects do not belong within legal theory, concerned as it is with finding the necessary features of law. On this view, the determination of these matters properly belongs within political theory.

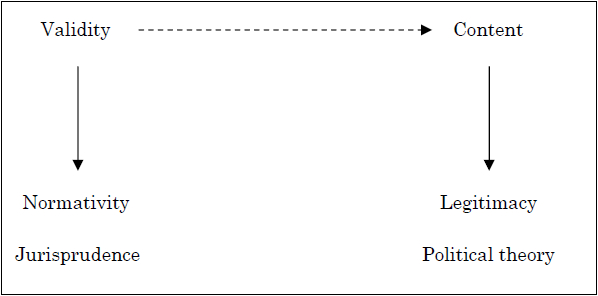

I believe this is a fair characterization of the way legal theory is understood by most contemporary legal positivists. The following chart provides a rough illustration of the relationship between the four concepts as they are understood within such a framework:

The starting point for analysis is validity. The existence of valid norms is required for legal content, and whatever counts as valid legal norms will obviously have an effect on the content of legal norms (this link is represented in Figure 1 by the dashed arrow), but apart from that, validity and content represent two distinct inquiries—exactly the distinction between “law” and “the law” we encountered earlier. This separation allows us to separate the political inquiry of what the content of law should be in order to be legitimate, from the morally neutral and descriptive account of the way in which valid legal norms create obligations. These links—between validity and normativity, and between content and legitimacy—are conceptual in the sense that it is the validity of legal norms that explains their normativity,[31] and it is the content of legal norms that explains their legitimacy. (This link is indicated by the solid arrows in Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The four concepts in contemporary versions of legal positivism

If this approach were successful we could maintain the separation between the jurisprudential question of validity and the political question of legitimacy. But it is not. The argument for this conclusion consists of two ingredients: first, that the question of legitimacy is a moral and political question on which people disagree; and second, that legal validity is connected to and affected by questions of legitimacy. If this argument is successful, even the narrow claim that it is possible to identify the sources of legal norms without appeal to morality will turn out to be false. More specifically, if successful, the argument shows that the only way to maintain the rule of recognition is not as a social rule that purports to explain why people behave in a particular way and in this way explains how law operates. Rather, the rule of recognition will turn out to be a generalization that can only be applied ex post facto to all situations, and as such is devoid of explanatory power with regard to any puzzling feature of law.[32]

I will take it for granted that different people have different views about the legitimacy of political authority. It is ultimately this question that is behind most books in political theory; in less abstract form these debates are also found in discussions about the proper “size” of government, or in debates about the adequate allocation of and limits to the power of government. The next step in the argument is to show that these debates are relevant to the determination of which sources are “valid”. This is not very difficult to show: there is, for example, right now an ongoing debate in the United States and in other countries on the question of the permissibility of relying on foreign court decisions, a debate on which both legal academics and judges have weighed in. Both proponents and critics of reliance on foreign sources do not just accuse the others of misunderstanding how the business of judging is properly done, or of failing to take note of an accepted social rule among judges. Rather, supporters of the practice defend it in terms of its ability to reveal certain moral truths, or emerging global moral consensus, considerations whose relevance to a decision rests on a particular conception of legitimacy. Critics, on the other hand, have responded with arguments that are couched in terms of national sovereignty, separation of powers, the proper role of the judiciary, the locality of value judgments, and so on.[33]

This is not all: clearly questions of legitimacy have an effect on questions of the content of legal norms. Thus, for instance, it is considerations about legitimacy that ultimately determine the level of deference judges give to pronouncements of other branches of government on the law; in federal states it is the question of the relationship between state and federal government; for the member states of the European Union it is the relationship between their domestic law and European law. These issues are often discussed in terms of separation of powers, national sovereignty, and democratic accountability, and the different views on them clearly reflect different views on legitimacy. Perhaps most commonly, any determination of the content of legal norms will require resort to theories, canons, or practices of interpretation. Though debates on these matters are often described in terms of “fidelity” to law, of finding the “true” or “real” meaning of statutory phrases, here too questions of legitimacy are never far from the surface. For whatever counts as “faithful” interpretation will depend on the division of labour between branches of government, and this, in part, is a question of legitimacy.[34]

These considerations affect issues that legal positivists would classify as belonging to the question of validity. Take, for example, the question of whether, in interpreting statutes, judges should favour the “plain meaning” of the words over the “intention” of the legislature or the “purpose” of the law. This looks at first like a debate about the correct meaning of legal sources, but as the linguistic question on this matter is often indeterminate, what decides the matter are considerations of legitimacy. Familiar arguments in these debates (for example, debates about the value of accessibility of the law to those without legal training or the importance of giving incentives to the government to make sure its legislative intentions are clearly stated) are relevant not just for the question of the right method for reading the sources of law, they are also arguments about which sources are legitimate. For example, arguments used in support of “plain meaning” have often been used to argue against the use of legislative history and preparatory work as permissible sources of law and in favor of using dictionaries as aides in statutory interpretation.

So questions of what counts as law, or as sources of law, are shot through with considerations of legitimacy. Indeed, even with the “obvious” sources—legislative acts or precedents—considerations of legitimacy are part of the story. True, it may be that if asked to explain why she relied on a statute, a judge would first respond, “because it is the law,” or even “because that is how we do things around here.” But if pressed I doubt whether any judge would say that this is where her spade turned. This, of course, is an empirical claim for which I cannot provide conclusive proof. But neither have legal positivists offered contrary evidence. Hart’s claim that “surely an English judge’s reason for treating Parliament’s legislation (or an American judge’s reason for treating the Constitution) as a source of law having supremacy over other sources includes the fact that his judicial colleagues concur in this as their predecessors have done,”[35] is equally unsupported by evidence. There are, however, plenty of examples of judges explaining their judicial practice and its limits by appealing to the political and institutional constraints of the judicial role. It does not matter whether their arguments are astute or not. What matters is that in doing so judges show that the boundaries of their practice are not (exclusively) set by social conventions. Moreover, even if Hart’s claim is true, it is very weak, as it only demands that the practice be one among several reasons that motivate the judge. Therefore, while this view is not contradicted by my claim that political considerations affect judges’ views on the legitimate sources for their decisions and the legitimate boundaries of their adjudicatory role, it cannot challenge it either.

Going back to the quotation from Marmor with which we opened the discussion we can now understand where he misunderstands Dworkin. It is not that American judges disagree about whether acts of Congress are sources of law; they agree about that. What they disagree about is the political theory that underlies the fact that acts of Congress are sources of law. While their disagreements are modest enough that they allow positivists and Dworkin to work together, which explains why they all accept acts of Congress as legal sources, it does affect the question of the recognition of other legal sources (as well as the question of what content to give to those sources) and explains, at least in part, why they disagree where they disagree.

If we aim for our theory to be “descriptive sociology”, and especially if we believe, as Hart did, that it is important take participants’ attitudes into account in understanding the practice, then the conclusions just reached cast doubt on the very foundations of the account told by legal positivists. At least as long as we stick to the legal systems that legal theorists usually talk about, those of contemporary Western democracies, we can easily find examples for the significance of legitimacy to the questions of sources of law.

B. Recasting the Relationship between Validity, Content, Normativity, and Legitimacy

The failure of existing positivist theories to give a satisfactory account for all this suggests that perhaps, despite the intuitive appeal of legal positivism, the source of the problems lies in the way positivists formulate the relationship between validity, content, normativity and legitimacy. At this point we should return to Dworkin’s account. Using these four concepts I will present what I take to be the core of his position. Again, my purpose here is not to defend every aspect of his view, which is why I ignore many familiar themes from his work. Many of them are no doubt central to Dworkin’s conception of law, but they are irrelevant, even possibly distracting, in explicating what I take to be the fundamental contrast between legal positivism and his position. I use his position as an example of the viability of an alternative approach to jurisprudence. Along the way I also aim to show that the difference between his view and legal positivism is not to be traced to some specific idiosyncrasy of his theory and why it is a fundamental mistake to think that his account presupposes the truth of legal positivism.

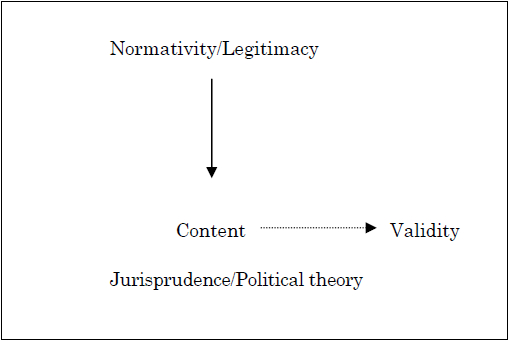

I begin with a rough sketch that illustrates the way in which the four concepts are related to each other in my reconstruction of Dworkin’s account:

Figure 2

The four concepts in Dworkin’s theory

In Dworkin’s account validity, if it plays any role in his account at all, is the least important of the four: validity for him is the conclusion of the inquiry. The starting point, by contrast, is the question of legitimacy. Dworkin makes this point, albeit somewhat obliquely, when he says in Law’s Empire that “[j]urisprudence is the general part of adjudication, a silent prologue to any decision at law.”[36] This passage puzzled—and has been vigorously contested by—many a reader of Dworkin.[37] I think it has also been misunderstood. Raz, for example, took Dworkin as claiming that in order “to know the law governing each case one must be making, explicitly or implicitly, assumptions about the nature of law.”[38] John Gardner interpreted Dworkin as believing that “[h]ow law is depends entirely on how it ought to be. Law is comprehensively tailored to its purpose.”[39]

But this is not what Dworkin meant by this passage. Properly understood this passage fits Dworkin’s general account very well and, as I shall try to show, is quite plausible. Dworkin claims here that jurisprudence is presupposed by every legal decision, because it is jurisprudence that can explain how the coercive acts of the state—including those involved in the legal decision—are (potentially) legitimate, and are not merely force backed by the threat of punishment.[40] It is in this sense that we can understand his claim that the point of jurisprudence is to explain the “coercive” force of state power.[41] It is thus not assumptions about the nature of law that is implicit in every legal decision, but rather a view about the fact that one can only make sense of the fact of legal coercion by offering an account of what can make it legitimate.

That Dworkin is concerned with the question of legitimacy is clear also from his immediately subsequent discussion of the law of evil regimes. As he says there it is, of course, possible to use the word “law” to describe state-run mechanisms of social control and that in this sense it is obvious that most evil regimes have “law”. But there is nothing philosophically deep in saying so: it may be true by virtue of linguistic stipulation, or it may be offered as an empirical observation—usually unsubstantiated—about prevalent linguistic usage. Either way the claim is of no philosophical interest and the debates surrounding it are pointless. However, understood as a debate about the limits of the legitimate use of force, the discussion becomes interesting, for it is then that the question we are required to consider is the boundary between legitimate use of force and what in essence is no different from the demands of the robber. This is clearly a normative question to be derived from political theory.

On this view the starting point for the inquiry is legitimacy. We are trying to identify the conditions under which a state’s use of force (and more broadly power) may be legitimate. Apart from avoiding the difficulties we encountered in the validity-first approach, this approach offers three additional advantages. First, it highlights the role that legitimacy plays at every stage of the inquiry. In the positivist story the only point where questions of legitimacy enter into the picture is when dealing with the rather exotic question of the obligation to obey the law. But observation of legal reality, from high-minded academic legal discourse to demonstrators’ placards, reveals the significance of legitimacy to law in the distinction between law and non-law, as well as in questions regarding the identification of sources, the role of the courts, the content of legal norms, and so on. This means that rather than (potential) legitimacy being the product of norms having the right content, it is recognized that considerations of legitimacy play a role in determining the sources and content of legal norms. By contrast, legal validity plays little role in these questions. True propositions of law may be called “valid legal norms” if one wishes, but the separation, crucial to legal positivism, between validity and legitimacy is rejected. To the extent that we can specify certain general features that distinguish law from non-law, these features are a product of an account of legitimacy.

Another advantage to starting with the question of legitimacy is that we can see how it affects the concrete form of certain institutional features of legal systems. In this way considerations of legitimacy help us understand the place of law within the broader political and social structure of the state as an answer to problems that at least in part have to do not just with efficiency and convenience (which were predominant in Hart’s account of the move from the pre-legal to the legal society with the addition of the secondary rules), but with right; on most accounts courts are not just added because of the inconvenience of a system in which there is no mechanism to settle disputes, but rather because they are a necessary part of a structure of government that maintains the legitimacy of the use of force. And to the extent that we want to justify the existence of law alongside many other mechanisms of social control (markets, politics, majoritarian decision making, experts, social norms, and so on), it may well be that considerations of legitimacy will play a role on this score too with different views on these matters likely to result in fundamentally different answers to the question “what is law?” Indeed, even the hallmark of legal positivism—the idea that law may be immoral and remain “valid” becomes clearer within this framework—as it offers an argument aimed to explain why it is that law and morality are treated as separate domains. It is this framework that makes sense of the question of how it is that courts may sometimes be legally wrong even when they reach the morally right answer, as questions of legitimacy arguably relate not just to what is decided, but also to the question of who should decide and why. Likewise, it is considerations of legitimacy (such as the considerations about the proper limits of political authority associated with the harm principle) that explain why we leave certain moral issues ungoverned by law.

The third reason to start with legitimacy is that it helps solve a familiar paradox that bedevils positivist theory. The positivist account presupposes that valid legal norms are created by “officials”; in fact, if we adopt Hart’s version of the rule of recognition for a legal system to exist at a minimum there must exist a social rule of recognition accepted by officials. But those officials can only be officials if they were so recognized by a pre-existing legal system, that is, by valid legal norms that make certain people officials by giving them certain legal powers. But these legal norms could only have been created if there had been legal officials beforehand, and so on ad infinitum.[42]

The paradox is resolved, however, if we begin with legitimacy. For as we have seen our starting point is not with legitimate legal rules, but rather with the legitimacy of use of force. We avoid the circle if we can formulate an argument about the origin of political yet pre-legal authority. Law on this view may be one, perhaps the predominant but not necessarily exclusive, means by which a political authority exercises its powers. A distinct advantage of this view is that it clearly separates the question of the legitimacy of political institutions from the question of the legitimacy of law: a legitimate political authority may still make individual laws, but, on the contrary, illegitimate political authority will not be salvaged by maintaining those elements that guarantee the legitimacy of law (for example by adhering to the principles of legality). In a way, of course, this only postpones rather than solves the problem, for it requires us to give an account of the legitimacy of political authority; but though controversial this is a problem for which most political philosophers (and, apparently, lay people) believe we can find a satisfactory solution. It should be noted that law may play a role in such an account. As a historical matter we may find out that all legitimate government began with illegitimate use of force (this was, for instance, Hume’s view), in which case the establishment of a legal system will often be meant (and taken) to be a step in the direction of turning illegitimate use of force into a civil society. Against this the Hartian account of the emergence of a legal system looks so unrealistic not because it does not reflect historical reality, but because it leaves out the most important aspect in the transition from pre-legal use of force to that of a potentially legitimate legal regime.

The legitimacy-first account is also valuable in illuminating existing juriprudential debates. It reveals, in particular, why legal positivists’ insistence that any account of law must presuppose something like a rule of recognition is in some sense true but unimportant, and false in the sense in which it poses a challenge to Dworkin’s theory (or for that matter any legitimacy-first account). The rule of recognition performs both the role of identifying the sources of law and of accounting for their binding force. Because Hart and his followers invoked the idea of convention for both roles, the two roles are sometimes confused, but it is important to keep them apart. In the former sense Hart relied on conventional ideas to explain why judges rely on certain sources and not on others: they do so because other judges do the same. Hart also relied on some rudimentary notion of convention (what is sometimes called “the practice theory of rules”) as the explanation for why these rules are binding.

Untangling the two issues helps us see that, at least as far as the first question is concerned, all that needs to be shown is that within a particular community there is an accepted distinction grounded in a social norm between accepted and impermissible sources of law. But the existence of such a norm is perfectly consistent with an account that begins with legitimacy. In fact, there are good reasons for thinking such an account would be closer to reality, since (as already mentioned), if asked to explain why they consider only certain sources as binding, it is unlikely that judges would only say is “this is how we do things around here”; in all probability a judge will offer legitimacy-based reasons for the distinction between permissible and impermissible sources.

This response, however, may seem too quick. It may be replied that legitimacy is neither sufficient nor necessary for identifying the sources of law. It is not sufficient because there are many different legitimate ways for a legal system to be structured. So even if a person can appeal to considerations of legitimacy in explaining her actions, these considerations under-determine the sources of law and leave room for different local conventions. Legitimacy is also not necessary because we can imagine a legal system in which all that judges offer in answer to the question of why they act in a particular way is appeal to an accepted standard without ever invoking considerations of legitimacy. The claim may be that something like the rule of recognition is required to explain these situations.

Let me begin with the second point. This point is significant only if we are shown that there are such societies in which legitimacy does not play any role in determining what things count as permissible or mandatory sources of law, or that when appeals to legitimacy are being made, they are for one reason or another disingenuous. Until either possibility is made out, I think we can ignore this point as a hypothetical fantasy. Without further argument there is no basis for the view that we will understand what human law is by hypothesizing legal systems that are fundamentally different from any example of law among humans.

As for the claim that legitimacy is not sufficient to determine the sources of law, it is no doubt true that the answer will be in some sense “conventional” in the everyday sense of the term: the legitimate sources for a particular legal system will be, in part, determined by contingent historical facts, which might have been different. In this sense, however, the existence of a rule of recognition is so weak it does not pose a challenge to any competing view. The question is—and this ties us with the issue of law’s normativity—whether the fact that there is a conventional element in the law in this sense requires us to accept the idea that it is what explains the normativity of law. And here I think the answer is: not necessarily. That many people act in a way that is arbitrary in the sense that if history had been different, they would have acted differently, does not entail that they currently act in the way they do because others do the same. Furthermore, there is good evidence for the claim that such a norm need not be a convention; there is just too much diversity in the way individual judges treat their “rule of recognition”, and differences in their views on how to interpret statutes, how much to respect authority, how much to defer to the interpretations of other branches of government, and so on. This is consistent with the existence of a (weak) social norm, which each person follows for his or her own (slightly different) reasons. Such diversity in rules of recognition, however, is not consistent with a conventional explanation of the normativity of law.

Furthermore, much of the motivation for invoking the idea of convention (or its more recent alternatives such as plans or shared cooperative activities) is gone if we accept that the basis of the judges’ adherence to a certain standard on what things count as accepted sources of law is an argument from legitimacy. In that case we can look for an answer to the question of normativity in the more natural domain of political morality. This does not necessarily require subsuming the question of normativity within the question of legitimacy, nor does it solve all problems—there are, after all, those who deny the normative force of morality and those who deny that the state can ever exercise legitimate political authority. But if we think there is, at least in principle, a good answer to these challenges, then much of the motivation for proposing the rule of recognition as a conventional solution to the problem of normativity disappears.

V. The Significance of Legitimacy to Legal Theory

Though the debate between legal positivists and Dworkin figures so prominently in legal philosophy over the last forty years or so, it is important to stress that the significance of the argument developed here is broader. I will therefore begin this section by showing some implications of the argument developed for Dworkin’s theory and on legal positivism, and will then turn to examine its impact on other jurisprudential issues.

A. Making Sense of Dworkin

I think what emerges from the previous discussion is that rather than being, as one commentator called it, “quite bizarre”,[43] Dworkin’s approach is a sensible way of posing a central philosophical question about law, one that should be particularly appealing to those interested in providing a descriptively accurate account of law. Several features of Dworkin’s account are worth highlighting. First, the characterization of legal philosophy as concerned first and foremost with the question of validity is not an accurate presentation of the scope of its concerns, although it is probably a fairly accurate description of legal positivists’ answer to its most general questions. A more accurate way of understanding the concerns of analytic jurisprudence—among other things, because it is more conspicuous in revealing the way Dworkin’s work is engaged with the work of legal positivists (and, importantly, the way it challenges it)—is that jurisprudence is concerned with explaining the relationship between the validity, normativity, legitimacy, and content of legal norms. Legal positivists offer one characterization of this relationship (in fact, this may be one of the few things that unite the otherwise diverse group of self-styled legal positivists), one which gives validity conceptual precedence over the other three concepts; non-positivists, or at least some of them, offer others.

Second, Dworkin’s competing account explains why, to the extent that we ground our account in the question of legitimacy, the fact that there exists a practice of paying attention to, say, certain pronouncements that come out of Congress, does not suffice. Even if this practice is conventional and gives us a satisfying answer to the question of the normativity of law, the existence of such a convention matters only if we can provide an explanation for the conditions under which such a convention and its products are legitimate.

Third, because the question of legitimacy can be raised with regard to every legal norm, we can understand Dworkin’s otherwise surprising claim that his theory of law “is equally at work in easy cases [as in hard cases], but since the answers to the questions it puts are ... obvious [with regard to easy cases], or at least seem to be so, we are not aware that any theory is at work at all.”[44] Whichever way we draw the line between easy and hard cases,[45] legitimacy is equally pressing and goes “all the way down” in easy cases as in hard cases.

Fourth and related, it explains Dworkin’s claim that legal theory is properly understood as a branch of political philosophy.[46] More specifically, it explains why the question of legitimacy can be asked (and in practice is frequently asked) both at the level of entire legal systems and at the level of particular cases. Even though we could make some general claims on the question of legitimacy, the question of the legitimacy of law arises in the context of particular cases, and may—through doctrines of interpretation, the status of certain potential sources of law, the degree of “deference” the court should display toward the work of other branches of government, and of course the particular subject matter in question—affect the outcome of individual decisions. And given that the determination of what the law demands is grounded in an analysis of what follows from the political question of legitimacy, it is correct to say that jurisprudence and political philosophy are presupposed by (even though they do not determine) every judicial decision.

We can now also see why the distinction between “law” and “the law” is not as fundamental as legal positivists assume. There is no question that we may speak about law in general. The question is whether the inquiry of understanding “law” is fundamentally different from the inquiry of understanding “the law” in particular cases. As we have seen this view is closely tied to the validity-first view; in a sense it is nothing but shorthand summary of it. But once the view that it is possible to identify individual valid legal norms separately from their content is rejected, the theoretical distinction between “law” and “the law” goes with it. On the view that starts with the question of legitimacy, the latter is just the aggregate of the former, and the boundaries between norms (however those are defined) must be the outcome of looking at their content. Similarly, under the legitimacy-first framework the separation between the question of what law is and how judges should decide cases becomes rather blurred. Given prevalent (albeit perhaps false) views on legitimacy, it is plausible that judges should decide cases by following “the law”. It follows that to identify what the law is, what it requires, is (normally) also to identify how judges should decide cases.

Fifth, the account offered here explains the connection between interpretation and legitimacy and the centrality of interpretation within Dworkin’s account. One need not accept everything Dworkin says about interpretation to recognize that different theories of interpretation in law are ultimately different theories about the division of powers between branches of government and between government and the people. As such they owe more to questions of legitimacy than to theories of meaning.

Sixth, Dworkin’s account is “descriptive” in the sense that he believes it captures the essence of law; Dworkin has also always maintained that his overall account is more accurate in describing existing legal practices, at least in contemporary Western legal systems. Nonetheless, the descriptive element of his claim is not as central to his account as it is to “descriptive” legal positivism, and a challenge that his account does not capture how law is practiced in a particular jurisdiction would not undermine his theory in the way that such a claim would undermine positivist theories. For even if it were conclusively shown that the way Dworkin fills in the details of his account—matters that I largely ignored in this essay—does not fit existing practices in any existing jurisdiction, it would be open for him to say, that the “legal system” in question is not really distinguishable from a gunman demanding money by force, and that that society would do well to develop a richer account of political morality that would acknowledge the role of law as one means by which political authorities can legitimately operate.

I must stress yet again that though this section has sought to defend certain aspects of Dworkin’s enterprise, as presented it is neither complete nor without weaknesses. At least as an interpretation of Dworkin’s work, its incompleteness should not come as a surprise given how many elements from his work were left out. It may be that some of those other elements are less convincing (as it happens, I think this is indeed the case), but if I am right, at least what I take to be the core of Dworkin’s position can be severed from those other components. As for its weaknesses, I shall only briefly mention a few that relate to the present discussion of legitimacy. For Dworkin, as I understand him, integrity is the primary value that law has to maintain in order to be legitimate, but in discussions of other institutions he seems to think that integrity is (or should be) what legitimates them as well.[47] This seems to me to ignore, or at least downplay, the significance of having different institutions which may be differentiated by, among other things, their legitimating values and practices. Relatedly, and more directly opposed to the argument as presented here, I believe Dworkin gives too prominent a role to the content of law in his account of legitimacy. It is at least arguable that the way the law makes its requirements has some bearing on the question of legitimacy. When Dworkin talks of morality, he speaks almost exclusively about getting to the morally right result. But I think one of the most important ideas in twentieth century moral and political philosophy has been the recognition of distinct institutional morality. I believe that these have a much more important role in legitimating law than does Dworkin, who has not accorded them much significance.

I have also said little about the place of the question of normativity in Dworkin’s account. The reason is that in Dworkin’s account the distinction between the metaphysical question of normativity and the political question of legitimacy is mistaken, for it is a form of what he called Archimedeanism.[48] Whether this view is defensible is something I will not examine here. His arguments on this score have been criticized, and I find some of these criticisms cogent. Beyond that, the closest he gets to an independent examination of the question of normativity is his discussion of associative obligations, and even there questions of normativity and legitimacy are not kept apart.

All this does not change my view that at the abstract level discussed in this essay Dworkin’s account is coherent, and does not presuppose legal positivism of any sort, and that the challenge it poses to legal positivism is much more fundamental than legal positivists assume. I stress this point because it is sometimes claimed that Dworkin rules out in advance and on dubious methodological grounds competing jurisprudential enterprises like the one most legal positivists are engaged in.[49] The better view is that Dworkin’s views are a direct, substantive challenge to positivists’ views on the correct relationship between the concepts of validity, content, normativity, and legitimacy.

B. The Future of Legal Positivism

Ultimately, however, I do not much care whether the view presented here is a successful interpretation of Dworkin’s work. What is more important is whether this is a defensible view, which presents a challenge to legal positivism, at least as the term is understood these days. It clearly is a challenge if we understand legal positivism to be the claim that there is no necessary connection between law and morality;[50] but I think it undermines even weaker versions of legal positivism, such as the view that “whether a given norm is legally valid ... depends on its sources, not its merits,”[51] primarily because it challenges their starting point. Whether there is some thesis that is close enough to contemporary versions of legal positivism and that can be accommodated within the argument presented here is a separate matter. Defenders of legal positivism have a long history of changing what they mean by the term in the face of adversity. Here I will consider briefly several potential changes the term might take and consider whether they could be accommodated within the framework proposed here.

Perhaps the positivist thesis can be narrowed down in the manner similar to that adopted by inclusive positivists in response to the claim about the relationship between validity and content. Legal positivism would be then defined roughly along these lines: “as a conceptual matter, a legal system could exist when judges (or officials) follow certain social rules identifying valid legal norms only because other judges (officials) do the same.” The problem with this thesis is that it is hard to see how it could be tested. If we try to examine it by appealing to intuitions, all I can do is report my intuition that such a legal system could never exist given what we know about human nature.[52] Legal positivists may have different intuitions, but if the whole discussion ends up with competing speculations as to which social structures could exist or what kind of strange hypothetical situations the word “law” (or the concept law) could bear before breaking down, I doubt there is any point in engaging in the debate in the first place. It would be very unfortunate indeed (but, I fear, not without precedent) if jurisprudence were reduced to these sorts of debates.

A more promising approach, then, would be to accept the framework that begins with legitimacy, but to deny that this forces a breakdown of the distinction between political theory and jurisprudence. Jurisprudence can remain “descriptive” because the legal theorist can only describe views on legitimacy without endorsing them. The only plausible reason for engaging in such an enterprise that I am familiar with is that it “helps us understand our institutions and, through them, our culture.”[53] The problem with this approach is that it is at odds with the generalist aims of discovering the nature of law endorsed by virtually all contemporary legal positivists. By ignoring the differences, this approach lacks the means for accounting for the contingent elements that are crucial for the understanding of one (“our”) culture; and it is unlikely to succeed in this task as long as jurisprudents stick to the ahistorical and fact-thin methods of analytic philosophy which are predominant among the very same legal positivists who extol the virtues of descriptive jurisprudence. There are very many books I will recommend before The Concept of Law to anyone interested in “our (legal) culture”, not because it does not reflect a particular culture—it does—but because Hart does all he can to hide this fact. Rather than learning about them in The Concept of Law one needs to look elsewhere and then go back to that book to be able to notice just how deeply it is steeped in a particular legal, political, philosophical, and cultural worldview.

The more interesting question therefore is whether we can accommodate a theory that captures some important positivist ideas within the framework summarized in Figure 2. Perhaps the most obvious way of doing so is the position sometimes known as “ethical positivism”. On this view it is a good thing for law to be understood in positivist terms. There are two species of this view. According to one, “theoretical ethical positivism” if you wish, understanding the concept of law in ethical terms would tend to encourage a more critical attitude among members of society toward their laws; according to the other, “practical”, strand of ethical positivism there are good political reasons for designing a legal system in a way that reduces courts’ ability to make politically controversial decisions. Proponents of the latter view, for example, favour intentionalistic theories of interpretation, oppose judicial review of legislation, and urge legislatures to avoid employing moral terms like “fairness” or “good faith” in their statutes.

Conceptual legal positivists usually deny any important links between their position and either version of ethical positivism, and in fact often regard the former as a fallacy. What law is, is one thing, they say, what we wish it to be, is another. Theoretical ethical positivism is thus dismissed as nothing more than “wishful thinking”.[54] By contrast, the practical version of ethical positivism is regarded as irrelevant or even antithetical to the concerns of conceptual legal positivists since the former is taken to be morally neutral whereas the latter is avowedly not.

The argument developed here suggests that it is in fact something like the view of the ethical positivists that may have the upper hand. The argument should not be that people will tend to have a more critical attitude toward the law if we maintain a positivist conception of it: this is an empirical claim, and one that will be hard to accept without empirical support (especially as some natural lawyers have made the exact opposite claim). Rather, it is the suggestion that for law or legal institutions to be legitimate they should be designed in a way that keeps moral judgment, as much as possible, beyond the purview of courts.

C. A Lease of Life for Legal Philosophy

Bentham and Hobbes are often considered the founders of legal positivism. But their legal positivism was very different from its contemporary incarnation. Both of them treated law, and legal theory, as part of, and subsidiary to, a broader moral, political, even metaphysical picture of the world.[55] Central also to both was the desire to give an account of law based on what they thought was the best available scientific account of human nature and psychology. True, these days philosophers rarely attempt such all-embracing enterprises, but what may have started as a narrowing down of the subject out of convenience or academic specialization has become the very definition of the subject: jurisprudence is that part of (philosophical) theorizing on law that is not political. One result of this change is that contemporary “conceptual” legal positivism is very different from the legal positivism of its supposed forefathers.

Central to this project of insulating law from political theory has been the attempt to give an account of the concept or nature of law. Daniel Dennett wrote in a different context that “[f]illing in the formula (x) (x is a conscious experience if and only if ...) and defending it against proposed counterexamples is not a good method for developing a theory of consciousness.”[56] I suspect much of the nature of law enterprise is driven by a similar sort of inquiry only with law in place of conscious experience, and I think the results have been equally unsatisfactory. Contemporary debates in analytic jurisprudence often seem so pointless exactly because questions such as whether there is a necessary connection between law and morality, which kind of connection exists, and other questions of this sort, are discussed without apparent concern as to whether an answer one way or the other will help our understanding of the social institution called “law”.

The approach to jurisprudence that starts with validity has played a central role in this story. The sensible but misguided theoretical assumption it is based on is that in order to understand law we must first identify it, and only then go on to assess it. This assumption is misguided exactly because in answering this question considerations pertaining to legitimacy happen to play a significant role. Therefore, the question cannot be answered in isolation from the inquiry into the legitimacy of law as one of several institutions for, and as such as one of several ways of, regulating behaviour and achieving social order that operate within the state. Abandoning this misguided approach would enable us to reorient “general” jurisprudence towards both questions of political theory and the work in legal theory that focuses on particular legal areas. Analytic jurisprudence has been separated from both for too long.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Brian Leiter, “The End of the Empire: Dworkin and Jurisprudence in the 21st Century” (2004) 36 Rutgers LJ 165 at 165-66 (Dworkin’s work in jurisprudence is “implausible, badly argued for, and largely without philosophical merit”). A similar attitude is expressed in Thom Brooks, Book Review of Dworkin and His Critics with Replies by Dworkin by Justine Burley, ed, (2006) 69 Mod L Rev 140 at 142. See also Larry Alexander, “Striking Back at the Empire: A Brief Survey of Problems in Dworkin’s Theory of Law” (1987) 6:3 Law & Phil 419; Jules L Coleman, The Practice of Principle: In Defence of a Pragmatist Approach to Legal Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) at 105, 184-85 [Coleman, Practice].

-

[2]

Julie Dickson, Evaluation and Legal Theory (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2001) at 22-31, n 31. C.f. HLA Hart, The Concept of Law, 2d ed, Penelope A Bulloch & Joseph Raz, eds (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994) at 240-41 [Hart, Concept]; Michael S Moore, Educating Oneself in Public: Critical Essays in Jurisprudence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) at 104, 306; Matthew H Kramer, In Defense of Legal Positivism: Law Without Trimmings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) at 128; John Gardner, “The Legality of Law” (2004) 17:2 Ratio Juris 168 at 173 [Gardner, “Legality”].

-

[3]

Ronald Dworkin, “Wasserstrom: The Judicial Decision” (1964) 75:1 Ethics 47 at 47.

-

[4]

Ronald Dworkin, A Matter of Principle (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985) at 146 [Dworkin, Principle]. See also Ronald Dworkin, “Legal Theory and the Problem of Sense” in Ruth Gavison, ed, Issues in Contemporary Legal Philosophy: The Influence of H.L.A. Hart (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987) 9 at 9, where Dworkin explained he was interested in the question of “the sense of propositions of law ... [which] asks what these propositions of law should be understood to mean, and in what circumstances they should be taken to be true or false or neither.”

-

[5]

Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1986) at 1 [Dworkin, Empire].

-

[6]

Ronald Dworkin, Justice in Robes (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 2006) at 2 [Dworkin, Robes].

-

[7]