Abstracts

Abstract

This article studies entrepreneurship education as a living ecosystem, on the basis of the ecological metaphor. It contributes to a multidimensional model to analyse Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystems (EEE). This model contains six key dimensions, extracted from the literature review: a/the learning framework; b/networks, connections and relational proximity; c/entrepreneurial culture; d/pedagogical solutions; e/learning spaces and materials; and f/the motivation of its actors. Based on these dimensions, we analyse nine case studies (53 interviews) of best practice programmes across schools in Spain, Germany and Finland to understand how the single actors experience their ecosystem at individual and collective levels.

Keywords:

- Entrepreneurship education,

- Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem (EEE)

Résumé

Cet article étudie l’éducation à l’entrepreneuriat en tant qu’écosystème dynamique. Nous modélisons l’écosystème éducatif entrepreneurial à partir de six dimensions issues de la revue de littérature : a/le cadre d’apprentissage; b/ les réseaux, les liens et la proximité relationnelle; c/ la culture entrepreneuriale; d/ les solutions pédagogiques; e/ les espaces et le matériel d’apprentissage; et f/ la motivation des acteurs. Ces dimensions sont utilisées pour analyser neuf études de cas provenant des écoles d’Espagne, d’Allemagne et de Finlande pour comprendre comment les différents acteurs forment leur écosystème aux niveaux individuel et collectif.

Mots-clés :

- Education entrepreneuriale,

- Ecosystème Educatif Entrepreneurial (EEE),

- enseignement primaire,

- secondaire et formation professionnelle

Resumen

Este artículo examina la educación empresarial como un ecosistema dinámico. Modelamos el ecosistema educativo empresarial basado en seis dimensiones de la revisión de la literatura: a/marco de aprendizaje; b/ redes, vínculos y proximidad relacional; c/ cultura empresarial; d/ soluciones pedagógicas; e/ espacios y materiales de aprendizaje; y f/ motivación de las partes interesadas. Estas dimensiones se utilizan para analizar nueve estudios de caso de escuelas de España, Alemania y Finlandia para entender cómo los diferentes actores forman sus ecosistemas a nivel individual y colectivo.

Palabras clave:

- Educación Emprendedora,

- Ecosistema Educativo Empresarial (EEE),

- enseñanza primaria,

- secundaria y formación profesional

Article body

Entrepreneurship education is dealt with in multiple publications that refer to numerous educational contexts (Toutain et al, 2017; European Commission, 2008; 2013). These publications also mention a variety of stakeholders. We may even speak about an entrepreneurial society (Audretsch, 2007) that considers individual aspirations but builds on social collaboration. Minniti (2005) states that we need to include the milieu in which the entrepreneurial process is embedded, which drives and supports it. Increasing attention has been given to a more organic and contextual perspective to understanding entrepreneurial learning as placed within an ecosystem (Isenberg, 2011; Aldrich et al., 2008; Nambisan and Baron, 2013). But how may entrepreneurship education be considered within its ecosystem? Our study responds to some major gaps in the literature on Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystems (EEE) by looking at the social environment that has an educative impact and shapes the mental and emotional disposition of its individuals (Dewey, 1916). More concretely, we ask how do the major actors (pupils, teachers, parents, directors, external partners) experience the EEE at individual and collective levels?

The theoretical framework draws upon the original definition of ecosystems in the field of ecology. The ecological definition of ecosystems is used as a metaphor to create a more specific and informed understanding of entrepreneurship education ecosystems. This process points out gaps in research and practice regarding the analysis and development of EEE. Based on findings from both the ecology and management literature, we gradually extract six dimensions to analyse and develop EEE and arrange them in a model called ’EEE-Model’ (see figure 1). The EEE-Model then serves as a methodological basis for the research design. The case study approach is used to explore the nature and functioning of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem from the inside. We look at a chosen number of European cases in primary and secondary education, as well as vocational training. We contrast individual perceptions of the ecosystem to obtain both an individual and collective picture of the ecosystem. Our research sample includes 53 recorded and typed interviews and 51 proximity maps, using an inter-case analysis method[1]. The methodology section is followed by the presentation and discussion of the research results. We conclude our work by addressing its limitations and implications for research and practice.

The 6 Key Dimensions of Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystems (EEE)

Today, educational institutions of all types are expanding their connections to the outside world. They adopt an increasingly systemic view on entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education as part of an ecosystem. In this section we introduce a model to analyse EEE, which we call the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem-Model (EEE-Model). It is constituted of 6 key dimensions, which we gradually extract from a review of literature on ecosystems and entrepreneurship education. These key dimensions are 1/The learning framework; 2/ Networks & Connections; 3/Culture; 4/Pedagogical Solutions; 5/Spaces and Materials; and 6/Motivation. The following subchapters introduce the key dimensions. Thereby, the review looks at the roots of ecosystems in ecology and their contribution to understanding entrepreneurship environments. We take a closer look at entrepreneurship education at primary and secondary school level, as well as in vocational training. At the end of the chapter we sum up the single key dimensions with the EEE-model (see figure 1).

Key Dimension “Entrepreneurial Culture”

Ecosystems consist of a community of living organisms that interact as a system with the non-living components of the ecosystem. The living and non-living components are linked through nutrient cycles and energy flows (Chapin et al., 2000). In 1930, the British botanist Arthur Roy Clapham first mentioned the notion of ecosystems (Willis, 1994). Five years later, Arthur Tansley looked at the exchanges between living organisms and their environment inside the ecosystem (Trudgill, 2007). Ever since, the concept of ecosystems has been part of the business and educational context. The concept of ecosystems gained paradigm status (Morin and Hulot, 2007). It is used, for example, to analyse the goods and services provided to human beings (Daily et al., 2009), or the management of resources to promote sustainable ecosystems (Chapin et al., 2000). Further research that is closely related to ecosystems was realised in the field of socio-ecological systems, for example in educational sciences (Weible et al., 2010; Colucci Grey et al., 2006). In the field of management sciences, Isenberg (2011) studied how entrepreneurship ecosystems increase venture creation and sustainable growth. He defined a number of elements to be considered, such as “leadership, culture, capital markets, and open-minded customers” (Isenberg, 2011, p 40). Ecosystems are complex, and it is difficult to predict what determines the quality of an entrepreneurship ecosystem, which can vary from region to region despite similar entrepreneurship activities (Kenny and Von Burg, 1999; Zacharakis, Shepherd and Coombs, 2003). Aldrich et al. (2008) tried to understand the development of ecosystems by introducing Darwin’s theory of evolution from the field of biology into business. Similarly, in education sciences, the psychologist Bronfenbrenner (1977, 1979) suggested viewing the ecology of human development as a mutual accommodation between the growing organism and the constant changes in the (social) environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1977, p. 514). More precisely, Bronfenbrenner takes into account various interactions beyond the classroom, such as parent-school relationships (Epstein, 1987; Hoover-Dempsey, 1995). More recently, Zahra et Nambisan (2011) sought to compare the effect of strategic reflections and entrepreneurship activities on the development of ecosystems. They studied the effects of interactions between companies and suggested four types of business ecosystems that determine a company’s successes and failures. Iansiti and Levien (2004) and Nambisan and Baron (2013) studied how companies and entrepreneurs activate cognitive strategies in an ecosystem and develop processes of self-regulation to adapt to their environment. In that context, the very nature of entrepreneurship education requires us to observe collaborations (Rae and Wang, 2015) and interactions beyond the content of programmes. EEE operates on a systemic/eco-systemic level (Henry and Lewis, 2018; Toutain et al., 2017).

Clark (2001) took reflections on ecosystems to an educational level and introduced the notion of entrepreneurial universities. His studies observed the capacity of universities to stimulate an entrepreneurial spirit inside their system. Universities are also places that provide infrastructure and resources to facilitate the development of entrepreneurial communities and the economy of territories in general (Greene et al., 2010). The entrepreneurial university has been explored through numerous case studies (Clark, 2001; Gibb, 2009; Gjerding et al., 2006; Smith, 1999), which revealed as a common finding that, despite common practices, there are as many models as there are universities to study. Therefore, we consider the entrepreneurial culture, with its predominant values and the entrepreneurial spirit that is transmitted, as a key dimension of entrepreneurship education ecosystems. It is probably the most complex dimension to capture and compare.

Key Dimension “The Learning Framework”

Theoretical and conceptual contributions to entrepreneurship ecosystems as a field of research are still very recent (Neumeyer and Corbett, 2017). Even fewer contributions to entrepreneurship education ecosystems exist. Regele and Neck suggested that entrepreneurship education is a “nested sub-ecosystem within the broader entrepreneurship ecosystem” (2012, p. 25). They insisted that more attention needs to be paid to this sub-ecosystem “due to its critical role in developing entrepreneurial attitudes, aspirations, and activity” (ibid., p.25). They examined American entrepreneurship education in different contexts, such as programmes targeting children of kindergarten age, and participants in vocational training programmes and programmes at higher education institutions. They concluded that current programmes in the US fail to meet the needs of entrepreneurs at all levels and that a stronger coherence and structure must be given to existing programmes. Indeed, Brush (2014) provides a framework for examining a school’s role in the development of local entrepreneurship ecosystems, suggesting a typology of roles that schools may pursue in developing their own internal entrepreneurship education ecosystems. Those roles can focus on entrepreneurship education programmes, co-curricular activities or research. A further study explores the functioning of the “Arthur Blanc Center For Entrepreneurship” (Brush, Corbett and Strimaitis, 2015). Consequently, we consider the learning framework of an entrepreneurship education – meaning curriculum-related information such as the number and nature of programmes and their learning objectives - as a key dimension of EEE.

Key Dimensions “Pedagogical Solutions”, “Spaces & Materials”, “Motivation of Actors”

According to established definitions in ecology (e.g., Chapin et al., 2000; Hagen 1992), ecosystems consist of a community of living organisms. In entrepreneurship education those are mainly represented by pupils, lecturers, school directors, parents, or external partners and are mentioned as key actors in this article. The living organisms interact as a system with the non-living components of the ecosystem. These non-living components apply to school buildings, classrooms, learning spaces and materials, as well as technology. The living and non-living components are linked through nutrient cycles and energy flows. The energy that flows through the ecosystem is conserved. In the educational environment, the fuelling energy may be translated by the motivation of its actors to contribute to the ecosystem and thus enliven it. Consequently, a lack of motivation can lead to dysfunctions in the ecosystems and eventually its death. Accordingly, looking at the field of education, motivation is considered an essential driving force of EEE (Deci, 1972; Deci et al., 1991). The flow of energy may be expressed through specific learning goals, pedagogies or learning philosophies that enliven and stimulate the education. As such, motivation and pedagogical solutions are two further key dimensions of the EEE.

Key Dimension “Networks, Connections and Relational Proximity”

The community of living organisms and their interactions define an ecosystem. Consequently, developing the networks and connections of a school is considered to be beneficial for the development of its entrepreneurship education ecosystem. In the field of primary, secondary schools and vocational training, recent studies (Leffler and Näsström, 2014) explore the relationship between education, entrepreneurship, the school, teachers, and the external environment. Schools with high levels of engagement in entrepreneurship education collaborate more closely with external actors of their environment (e.g., the local community) and know more about entrepreneurship pedagogies. Furthermore, a relationship with members of the local community was found to positively influence students’ learning. This is in line with a study by Ruskovaara and Pihkala (2015) demonstrating the importance of collaboration between the school, pupils and teachers with companies, external networks and society in developing entrepreneurial competences through an ’authentic’ learning process.

Consequently, proximity plays an essential role. Proximity law states that what is close, regardless of its nature, is more important than what is far (Moles and Rohmer, 1978). It is a multidimensional concept illustrating the qualitative judgement that a person has on social distance (Granovetter, 1973). Social Proximity has so far been neglected in entrepreneurship education research; only spatial dimensions[2] of proximity have been researched. In the functioning of networks, proximity enables the transfer and exchange of information and knowledge. Social proximity defines the social embeddedness of relationships at the microlevel (Boschma, 2005), including norms, values, rules of thought and action (Coenen et al., 2004). It relies on trust, kinship and experience (Boschma, 2005; Oerlemans and Meeus, 2005) and is equally mentioned as relational proximity (Coenen et al., 2004) or personal proximity.

We may conclude that the most recent developments in entrepreneurship education at the school level point towards a school whose borders breakdown towards the outside world and open up for the construction of closer collaborations (Tuunainen, 2005), while stronger connections between existing actors of an ecosystem are created. We therefore identify networks, connections and relational proximity as another key dimension of EEE.

Key Actors at the School Level - Needs and Limitations

We can see six groups of key actors inside an EEE on school level: pupils, teachers, school directors, parents and external partners; each with particular needs and limitations. The prior professional experience of teachers positively influences the entrepreneurial learning activities within the school; more precisely, their experience-related knowledge, social capital and external connections (Ruskovaara et al., 2016). According to Penaluna et al. (2015), enterprising educators might benefit from teacher-training provision, such as interdisciplinary approaches that promote cross-connections, creativity, innovation and opportunity recognition. Looking at schools where directors promote creative activities to develop entrepreneurial attitudes, limitations to entrepreneurial development were observed on the level of school authorities, trust and the distribution of power and responsibilities within their teaching staff (Hörnqvist and Leffler, 2014). More generally, Birdthistle, Hynes and Fleming (2007) found that teachers create awareness of self-employment possibilities and encourage entrepreneurial behaviour, capacities and competences. To meet their needs, teachers would like to establish more entrepreneurial ways of working by collaborating with the community (Seikkula-Leino et al., 2010). They confirm using a large spectrum of active pedagogies but provide insufficient links with true entrepreneurship experiences such as entrepreneurship practices, work experience or incubator methods (Seikkula-Leino et al., 2015). Parents remain sceptical regarding entrepreneurship education and the idea of imagining their child as an entrepreneur (Räty et al., 2016).

A Multi-Dimensional Model to Analyse Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystems

As introduced above, we distinguish six dimensions that constitute an EEE: (a) framework, (b) connections, (c) culture, (d) pedagogy, (e) spaces and materials, and (f) motivation. Those are captured in the model below (graph 1). From these dimensions we draw a model that we call the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem- Model (EEE-Model).

The dimensions in the EEE-model refer to the following aspects.

The learning framework of an education refers to curriculum-related information, such as the number and nature of programmes, their learning objectives and how they are assessed;

Networks, connectionsand relational proximity encouraged by the education. This refers to the connections between actors inside the ecosystem and connections created towards external actors and stakeholders and the way they are perceived;

Entrepreneurial culture of the ecosystem. The entrepreneurial culture is based on key values that its actors perceive in the education;

Pedagogical solutions privileged to stimulate learning. This dimension identifies the pedagogical solutions that receive preference (e.g., traditional teaching, experiential methods, learning by doing) and looks at the way they stimulate learning;

The motivation of actors to act or not inside the ecosystem is an essential driving force for its development and thus needs to be investigated. This refers to which aspects stimulate the will to contribute, or limit motivation (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

Research Gap and Research Question

The current entrepreneurship literature mentions the importance of taking a holistic look at entrepreneurship education as an ecosystem (Regele and Neck, 2012; Toutain et al., 2015); however, very little research has been carried out so far. Some have taken a qualitative lens to analyse existing educational ecosystems by comparing their success factors and challenges on the basis of a single expert perspective on the examined programmes (Rice et al., 2014); but

, no previous study has examined an entrepreneurship education ecosystem from the inside. This lack of examination means taking a closer look at the perspectives of its actors. Moreover, no study has approached the issue as an unknown to the examined ecosystem: existing studies have been conducted on cases of the researchers’ home universities.

Our research focuses on understanding an ecosystem from the inside by contrasting the individual perceptions of all its actors. We ask:

How do the single actors (teachers, pupils, directors, parents and external partners) experience the Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem (EEE) at individual and collective levels?

Since ecosystems are by nature very complex and constantly evolving organisms, we focus on investigating the six dimensions identified above (figure 1). This allows us to draw a momentary picture of the ecosystems of the examined schools.

FIGURE 1

Dimensions & Dynamics of Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystems

Methodology

We carried out a qualitative exploratory study (Dey, 2003) based on a multiple case study (Stake, 1995). We interviewed different stakeholders of the educative ecosystem who are engaged in entrepreneurship education. We decided to value the opportunity offered by a European call for best practices in entrepreneurial learning launched by the entrepreneurship 360 programme[3] of the OECD and the European Union. This programme is targeted at primary & secondary education, and vocational training. In 2014, approximately 100 schools applied to a call for entrepreneurship initiatives. Twenty-seven cases from 15 European countries were selected by OECD scientific experts. The cases were submitted by teachers or trainers of entrepreneurship initiatives who aim to create environments that best support entrepreneurial learning and an entrepreneurial school culture, but who also seek exchange and mutual learning from other initiatives. The cases are presented in detail on the OECD website of the entrepreneurship 360 programme[4].

We visited 9 out of these 27 schools from 3 different European countries – Germany, Finland and Spain. This selection allowed us to accommodate internal limitations and to choose theoretically useful cases (Eisenhardt, 1989). Internal limitations are related to financial restrictions that would not allow us for more than 3 excursions and to linguistic limitations since qualitative research at the primary and secondary school levels requires a native or near native language command of at least one of the researchers.

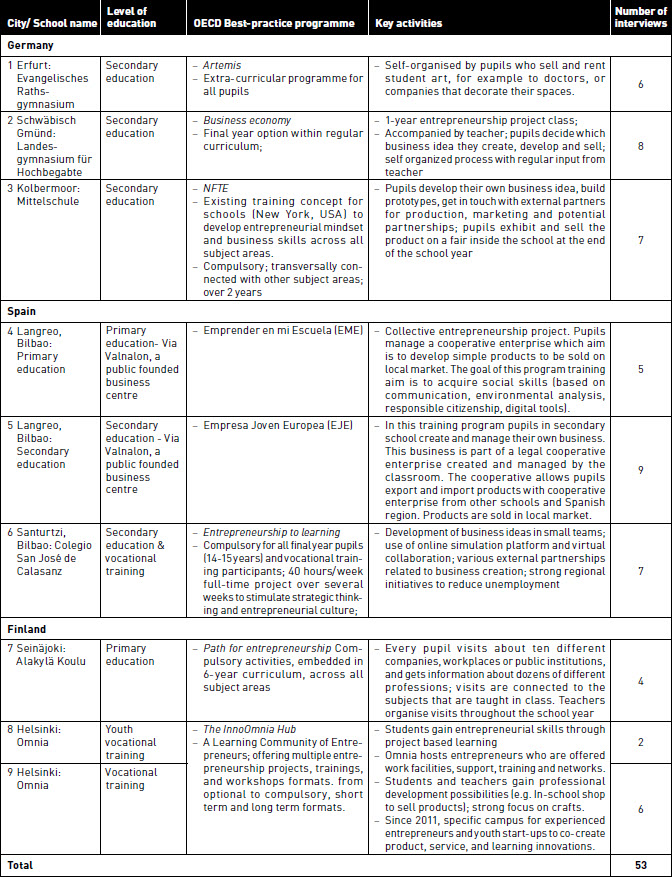

To build useful theory, we selected cases that would offer the greatest possible diversity within one category: we covered a northern, southern and central European country. We then made sure to cover primary schools, secondary schools and vocational training in each of these countries to contrast findings and “search for cross-case patterns” (ibid: 533). Prior to our visit, we sent out a request to speak to at least one representative of each major category of ecosystem actors: teachers, learners, directors, parents, and external partners. We overlapped data collection and analysis between the three excursions. This allowed us to better monitor when saturation of results was achieved. All examined cases used specific entrepreneurship activities, and exclusively worked with experiential learning approaches and action learning. Additional details of the examined case studies are presented in table 1 below.

Generally, most schools created or applied existing entrepreneurship programmes that are provided in a limited timeframe such as one school year and mostly as an option within the curriculum that is sometimes compulsory. The project leads students through an entrepreneurship experience from generating business ideas to developing them, thinking about budget questions, building prototypes and selling the idea – usually in form of small working teams. These ideas are often for products but rarely for services. Most programmes provide contacts with external partners, such as banks, entrepreneurs, or company visits and public occasions to sell their ideas (internal shops, exhibitions, etc.). Parents and their networks thus represent the majority of clients. Typically, pupils are given stronger instructions and guidance at the beginning of the project and then work increasingly autonomously, managing their own meetings and distributing tasks, especially in secondary education and vocational training. All programmes provide specific learning & and working spaces for pupils, often classrooms, sometimes dedicated workshop areas where handcraft is possible.

Our research design responds to recent criticism of research in entrepreneurship education as being too self-centred and isolated (Blenker et al., 2014). None of the chosen cases was known to us previously, nor did they stem from our own professional culture. Moreover, our team consists of three researchers from two different business schools, and with different cultural backgrounds (French and German). The study was conducted in 2015 when we spent one week per country to collect data, sharing roles and responsibilities in a rotation system.

In their review of methods in entrepreneurship education research, Cummins and Dallat (2004) suggest better defining enterprise and entrepreneurship to develop further links between enterprise culture and education (Gibb, 1993). Blenker et al. (2011) distinguish different levels of analysis with specific research designs.

Accordingly, our research focuses on the institutional level, using studies of processes, and looking amongst others at programmes, faculties and courses of an institution as subunits of analysis (ibid, 2011).

To define the elements of an education ecosystem we refer to the traditional literature from ecology (Chapin et al., 2000) and use the multidimensional model presented above (figure 1).

According to the EEE-Model (figure 1), the basic dimensions to investigate are: 1/ The learning framework; 2/ networks and connections encouraged by the education; 3/ entrepreneurial culture produced by the ecosystem; 4/ pedagogical solutions provided to stimulate learning; 5/ learning spaces & materials; and, as a driving force of the system - 6/ the motivation of actors.

Consequently, we based the guideline for the semi-structured interviews on the following questions in the following order:

What is the profile of a typical pupil/learner of your school? (dimension 1)

Who are external partners involved in entrepreneurial activities? (dimension 2)

What are most dominant learning/teaching methods in your entrepreneurial activities? (dimension 4)

Which materials and spaces are available for entrepreneurial activities & learning? (dimension 5)

How are entrepreneurial activities expressed in the curriculum? (dimension 1)

What are key activities to transmit entrepreneurial values? (dimension 4)

What is the most important learning through the education? (dimension 3)

What motivates you to engage in entrepreneurial activities? Where do you see limitations? (dimension 6)

TABLE 1

Research sample

To study how entrepreneurship education ecosystems are perceived by their actors we capture the perspectives of major actors involved (teachers; learners; directors; external partners; and parents) on each of the dimensions.

To complete data on individual perceptions of the dimensions, we captured the way actors perceive each other in the ecosystem - the relational proximity. We created a simple visual tool that any person, children included, would easily understand.

We used a proximity estimation method, including a form of numeric scale within a visual representation of relational proximity, which we called proximity map. This kind of map is frequently used to represent the different circles of proximity of a person, or for instance to illustrate Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory of development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Interviewees were asked to localize themselves and other actors they thought were playing a role in the programme on 5 concentric circles, with the name of the programme we studied at the centre. Each circle was weighted with a number from 1 to 5, with 1 being the closest circle to the education (and indicating the qualitatively highest degree of relational proximity) and 5 being the furthest away (the lowest degree of proximity).

The map suggested eleven potential actors for the interviewees in a multiple-choice format which they were free to locate in the map or complete with further actors: pupils, teachers, volunteers, school directors, companies, programme coordinators, parents, institutions/administrations, non-profit organizations, other schools and school staff. We specify that the proximity maps were filled out by the interviewees before the actual interview without any prior influence on potential actors through the interview questions. This helped us to estimate of the number of actors involved in a single ecosystem. The maps were analysed by considering the number of actors cited on the map (map density illustrating the “width” of the perception of the ecosystem) and the proximity score of each type of actor, indicating their “social visibility” and their perceived own proximity to the enterprise education (see the case’s data and analysis in tables 4, 5 and 6 of the appendices).

At each school, we collected four types of material:

A visit of premises documented with photographs, to capture the nature of the different spaces, materials and environment, as well as the type of interactions between actors;

A non-participating observation of an entrepreneurship class to get a feel for the type of pedagogy and relations in the classrooms;

Semi-structured interviews with different actors of the ecosystem (videotaped and voice registered);

Individually completed proximity maps.

We collected 51 proximity maps and held 53 interviews lasting 25 minutes on average with five categories of actors – learners, teachers, school directors, parents and external actors (e.g., entrepreneurs, bank directors, coordinators of external initiatives). We proceeded with a process of qualitative content analysis (Strauss, 1987) using methods of open, axial and selective coding (Corbin and Strauss, 1990) to develop theory. We organized and analysed data with the help of the software QSR-NVivo (Richards, 2014), which is compatible with principles of Grounded Theory and is recommended for data analysis (Hutchison et al., 2010). All interviews are based on the same interview guideline, while the formulation of the question was slightly adapted to the perspective of the interviewees based on their role in the ecosystem (e.g., parent, pupil, or teacher). Each set of data was gradually coded and discussed in the team after collection until agreement on saturation was achieved.

FIGURE 2

Proximity map

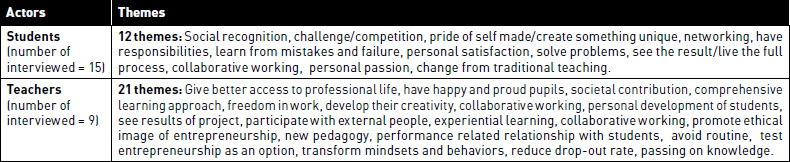

To illustrate inter cases thematic analysis the table 2.1 presents the theme “ Sources of motivation in EEE” for two main actors, teachers and pupils.

Table 2.2 then gives examples of teachers verbatim that were coded in these motivation themes.

Results

We present the core results regarding our qualitative investigation of an EEE’s key dimensions at the individual and collective level. These dimensions refer to:

the motivation of actors and limitations to motivation;

learning contents and key values of the programmes;

networks, connections and relational proximity.

Motivation at the Individual and Collective Levels

We described motivation as the driving force of an EEE, with the potential to decide about both its expansion and deterioration. Consequently, strong attention is given to this key dimension in the results section. We start with a description of the major limitations to motivation, followed by the key sources of motivation, and deepen reflections on the motivation of the coordinating teachers who demonstrate a particular type of motivation.

Limitations to Motivation

The perceived limitations to motivation strongly connect to the systemic idea of a school functioning as a family system where collaboration is required. For learners, aspects related to teamwork are of major concern. Collaboration can hinder motivation for various reasons; Pupils mention a “lack of motivation or performance of other team members”; or “conflicts with peers”. Some are demotivated by “not finishing a project”, since most initiatives do not actually create a company, and some are limited to a simulation of a project. Teachers see 3 categories of limitations: 1/ “Unfavourable conditions and resources” related to staff, material, available money or spaces, and a lack of family support; 2/ “Behavioural limitations”, referring to a lack of motivation and collaboration of pupils; and 3/ “The pedagogical culture”, which can limit motivation through “insecurities of teachers” who are “afraid of losing control” or “breaking with traditional class schemes”. Directors and external partners see “resistance to change” as a major limitation, Directors see resistance mainly on the side of “other teachers” who would like to stick to their usual programme and pedagogies, and external partners see resistance within all actors of the ecosystem – pupils, teachers, directors, and parents (following verbatim).

“The attitude of students, teachers and director is key! Taking risks is not easy for teachers and solving a problem and taking initiatives is often difficult for students”.

Interview School 1, Finland, external partner Marco, former school director

TABLE 2.1

Inter Cases Thematic Analysis of the Theme “sources of motivation in EEE”

(What motivates you to take part in this education? Why do you engage?) From the most cited to least cited

TABLE 2.2

Coding Process on Teachers’ verbatims

They state that everyone needs to be open to new ways of thinking and acting and that resistance is strong and deeply anchored. Hereby, the perceived influence of single actors on the overall evolution of the ecosystem becomes apparent, as does the necessity for change to be collective.

Sources of Motivation

Sources of motivation, just as their limitations, are of a social nature. “Social recognition”, for example, appears as a major motivation to participate in entrepreneurship education programmes across all actors of the ecosystem. While directors are concerned with recognition from “regional partners” and “other schools”, teacher seek “recognition from colleagues” and the “director”, and pupils are concerned with social recognition from “classmates and parents”.

“Open up a newspaper and see that you have 3 published articles in it. It’s great! It’s really nice to see that what I do becomes something in the end. And what I do is read by people. If someone, if only one person, reacts to what I wrote, it was worth it”

School 1, Germany, pupil, translated from German

To parents, social recognition from peers and teachers is also important. However, their major concern is about the “future of their child”, the “economic situation in their region” or country and the need to “create societal change”. Additionally, external partners, especially from private companies, focus on “societal change” as a major motivation to contribute to entrepreneurship education programmes.

Many teachers are motivated by the idea of “preparing pupils for the business world” and of enhancing their chances for both “employability” and “self-employment”. However, they also wish to simply see them “happy” and “satisfied” with their work.

“It’s my vocation! To see that traditional methods don’t work with these types of pupils who are not disinterested and in difficulty. To see that they take initiatives, not only for themselves! Teachers of other colleges always tell us that our pupils are not afraid, they are more mature.”

School 1, Spain, school director

For pupils, networking is an important aspect. Working in a team is what is most limiting and stimulating to their work. Additionally, “collaboration with teachers” motivates them. Finally, the ideas of “succeeding in a challenge”, “finishing a project”, the related “pride” and “self-satisfaction”, and the “joy of working on a project they are passionate about” stimulates them positively.

Motivation of Teachers as A Driving Force of the Ecosystem

We would like to specify the particularity of teachers in regard to motivation. We clearly observed the initiating force of highly engaged teachers who initiate, push and maintain entrepreneurial initiatives within and beyond their school. Throughout all cases, their motivation is expressed through the following qualities:

A strong capacity to motivate other actors in the ecosystem to participate and engage in their projects (such as learners, directors, entrepreneurs, parents, other teachers, etc.);

Consciousness of values they would like to stimulate through their initiatives;

A way of connecting to their surrounding that is both dissident and socially integrated.

These coordinating teachers possess a very good understanding of the context in which they are acting and the value they would like to generate through their actions, regardless of the actors with whom they are collaborating (learners, colleagues, entrepreneurs, etc.), as the following quotation illustrates.

My motivation is to develop some ethics related to entrepreneurship. Helping them to create something meaningful, not only as a means of enriching themselves financially (...). Valnalon (the regional entrepreneurship accelerator) is very much engaged; public institutions are helping, a bank and some private businesses, too. For example, we are offered favourable terms to send merchandise and renew our catalogue. All of them are located outside the school building, but inside the region. (...)

Interview School 1, Spain, business teacher, translated from Spanish

At the same time, the teachers (or coordinators) behind entrepreneurial initiatives demonstrate various degrees of dissidence within the existing system, which frequently creates conflicts between other actors such as colleagues, school directors or school staff. However, their initiative taking needs to be embedded into the social network of a school and to be supported by the schools’ authorities. Hereby, the systemic, or rather “family”, function of a school’s ecosystem becomes apparent. The following quotation illustrates this need for collective support on the institutional level.

It’s important that the project has “a home” inside the school, it has to be carried by the school family; otherwise, it cannot function. Also, regarding events, the director and vice-director must be behind the project (…) A Miss K. (coordinating teacher) alone – even with all her power – would have quickly burned out if she had faced a lot of closed doors. The entire school needs to engage.

Interview School 3, Germany, external partner, Association of Family entrepreneurs, President of the region South-east Bavaria

Even though all cases are based on the initiative of an individual teacher who demonstrates a certain degree of dissidence with existing approaches and programmes, there always is a solid basis of support from the school authority.

Learning Contents and Transmitted Key Values

As part of the key dimension “learning framework”, we investigated the perceived learning contents of existing entrepreneurship education programmes to contrast the descriptions of the different actors. Most of the programmes we visited run over an entire class or semester in the form of start-up challenges and simulation games, realized as teamwork. A few programmes are offered over 2-3 years and are connected to other subject areas. All actors of the ecosystem unanimously describe the key activities of their programmes as knowledge based, using descriptions such as “technical skills”, “start-up knowledge”, “marketing”, “finance”, “sales”, etc. Some of the directors also see “collaborative working” as part of the central activities. Interestingly, when looking at the descriptions of the key values of the programmes (related to the key dimension “entrepreneurial culture”), they are clearly seen in the development of human or social skills acquired through collaborative learning, as two pupils explain below.

“What I learned from last year is that collaboration and agreement are very important, as well as reliability. If you cannot rely on the others, the entire project will suffer in the end. Then it is best to know your own strengths, (…) because you can better attribute yourself to a task and those can be attributed more easily (…)”

School 2, Germany, pupils Jonathan and Philipp, translated from German

For pupils, the most frequently mentioned key values throughout all programmes are “problem solving”, “teamwork”, “creativity”, “conflict management” and “developing self-confidence”. For teachers, most important values are “socializing” and “making compromises”, “collaboration” and “team working skills”, “problem solving” and “creativity”. All actors confirm that these aspects make the programmes special and attractive to learners and distinguish them from their other classes. We state that programmes whose learning content is perceived as knowledge based may at the same time develop social skills within learners as a major perceived value of the programme.

Networks, Connections and Relational Proximity

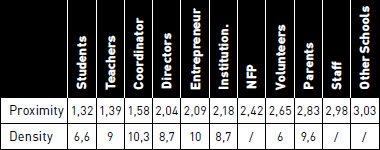

This section presents the results of the analysis of the 51 completed proximity maps, which allows us to better understand the relational proximity between actors.

Teachers and school directors appear to be the two most visible actors in the ecosystem. On average, the most cited actors per case study out of 11[5] possible actors are the teachers (5.4 times), followed by school directors (5.2), companies (5) and learners (4.9); coordinators, parents and school staff are at the same level (4.4).

Teachers are indeed “visible actors”, as they are most involved in the entrepreneurial programmes (organization, planning, delivery, contact creation, grading, etc.) and thus take more responsibility in the process than other actors, especially learners. Teachers are perceived as very close to the programme (average proximity of 1.39) by other actors, especially by directors (average score of 1.2 for teachers amongst directors). However, they do not place themselves at the very core of the programme (average proximity of 2 when teachers evaluate their own proximity).

Directors see a number of connections with other actors. They possess managerial functions and need to look from a meta-level on their educations. Their vision of the ecosystem may thus be wider than that of the learners or administrative staff. The actor who perceives the most other actors involved are programme coordinators (average density of their map is 10.3), with parents (9.6) and professors (9).

Interestingly, the perceived visibility of learners comes after teachers, directors and external partners, while they are supposed to be the main beneficiaries of the education. This correlates with another noticeable phenomenon regarding their perceived proximity. While pupils indicate the fewest number of connections on the proximity map (average of 6.6), the ones they do perceive are indicated to be very close (most often on level 1= closest). Surprisingly, some pupils do not include themselves (learners) in their map or put themselves on proximity level 2-4. Even though they are supposed to be the main actors of the programmes, they often perceive themselves as less involved and “close” than teachers. Consequently, we took a closer look at the interviews of students who did not place themselves on the proximity maps or who placed themselves very far from the entrepreneurship programme. There is no verbal explanation for this in the interviews. In fact, these pupils appear very enthusiastic. For instance, they do not see limitations to their motivation and they “love” the fact that “it’s different from the normal school”. They may simply not be aware of their central role in the programme and perceive teachers as being closer to the entrepreneurship programmes than they are themselves.

TABLE 3

Average proximity score per actor in ascending order and average density of actor’s maps

Average measures on the 51 proximity maps, proximity scale between 1 and 5 (1 being highest proximity), density between 1 and 11 possible actors.

Looking at the estimations of all actors, the quality of their relational proximity on a scale from 1-5, the average score for proximity shows that pupils, teachers and programme coordinators are equally perceived to be most involved (table 3).

School staff and parents are rated to be furthest away from the entrepreneurship programmes. However, they are indicated on the proximity maps and can thus be confirmed as members of the ecosystem.

When we look at the density of categories cited (= number of different categories spontaneously cited), teachers note an average of 9 connections, and school directors note 8.7. Interestingly, the parents we interviewed indicate an average of 9.6 groups of actors involved. This is surprising since parents are not directly involved in the programme. There is no participation in actual classes or programmes other than through their children at home. This is reflected in the proximity score attributed to parents with an average of 2.2, one of the most distant results. Most of the presented parents are part of school committees and were selected by the school. They demonstrate a high degree of involvement in entrepreneurial activities, which is not necessarily representative of parents in general. Consequently, they perceive a high number of involved actors, most of which they have never seen themselves. Their knowledge on the entrepreneurship programmes is generally wide but not very deep; especially detail questions can often not be answered.

Each of the suggested actors was mentioned at least one time per case study, even though they have not been interviewed directly and we cannot confirm their existence or implication (e.g., non-profit organizations or other schools). This result confirms our inventory of the members of an entrepreneurship education ecosystem.

As far as connections outside of the ecosystem are concerned, different elements appear. While teachers of the innovative programmes actively seek and create connections with external actors and within the school, pupils seem to naturally remain within a known territory. Links to external partners were initiated by pupils in none of the programmes without the explicit help or encouragement of teachers (and sometimes parents). It seems that the boundaries of an EEE do not naturally expand but need to be actively pushed by its actors. Currently, teachers take a leading role in that endeavour. In schools where collaboration between teachers and directors was strong, the process of network creation was more powerful and had a greater reach. At the same time, strong ties between the teacher and director can easily elicit jealousy or refusal of collaboration from other staff members. Interestingly, it appears that the diversity of actors involved correlates with the openness of an ecosystem to new ideas and perspectives. For example, one of the Spanish schools possesses a large network of external actors that each add different ideas and programmes to the school. At the same time, one of the Finnish schools incorporates all actors within their walls; all have similar views on entrepreneurship.

We sum up the key observations and conclusions from the results section in table 4 below, that is grouping the 6 key dimensions of the EEE-Model.

The eleven types of actors were confirmed as playing a role in the functioning of the ecosystem, but to different degrees. At its core are pupils and teachers. Creative energy was systematically added by the teachers and enabled through the support of the school director, who spreads this energy inside the school. Even though the observed ecosystems differ in size, they are usually driven by only one or few individuals (usually teachers). These individuals have developed a form of entrepreneurial connectivity that is both independent/dissident and socially integrated. Their activity is focused on expanding connections inside and outside the ecosystem, which is transmitted to learners through their entrepreneurship programmes. Even though the motivation of all actors is mainly driven by peer recognition, the teachers’ endeavour to connect actors and expand borders goes beyond the individual learning of their pupils. It clearly aims at contributing to the development of society through entrepreneurial initiatives. This intention is shared by school directors, external actors (especially entrepreneurs) and by parents.

Discussion

Individual and Collective Motivation

Morin (Morin, 2005, 2014) suggests that an ecosystem is created on the base of collective initiative. This initiative is clearly expressed in the motivation of actors, which is not only based on individual aspirations but seeks collective recognition for their work and engagement. Pupils would like their team to be rewarded, teachers would like to see their pupils successful and happy, and school directors wish for the entire school to make a good appearance. In the field of education sciences, Dewey (1916) stresses the importance for learners to participate in their community. The active role of individuals can stimulate participation in others and in return convert them into leading individuals. In that sense, the profile of coordinating teachers in our case studies is close to the one of entrepreneurs: reality and action are two driving forces that allow new forms of teaching and learning entrepreneurship to be developed through motivation. Ansari et al. (2014) conclude that “reality is an act of co-creation between an actor and her environment” (ibid: 34). The profile and behaviour of the teachers we interviewed illustrates the definition of entrepreneurial leaders provided by Greenberg et al. (2011): “Entrepreneurial leaders are individuals who, through an understanding of themselves and the contexts in which they work, act on and shape opportunities that create value for their organizations, their stakeholders, and the wider society” (Ansari et al. 2014, p. 32).

FIGURE 3

Actor’s relational proximity

Legend: actor’s relational proximity case by case (histograms). Level one indicates the highest proximity, level 5 the lowest proximity; the line indicates the average actor’s level of proximity across the 9 cases.

TABLE 4

Summary of key results

Dissidence with traditional structures appears to a certain extent as a natural component to spur entrepreneurship education ecosystems. At the same time, however, a certain degree and capacity of social integration and collaboration is required to allow the entire ecosystem to evolve with and benefit from the newly implemented initiatives. Mueller and Anderson (2014) identify the capacity for both independent thinking and social connection as part of an ’entrepreneurial maturity’ (ibid, 2014) that teachers of entrepreneurship should possess, and its learners progressively develop. Their study confirms that independent thinking as a critical ability may collide with other people’s opinions and consequently challenges social relations.

However, the rejection and isolation that some teachers encounter from peers when trying to implement entrepreneurship education programmes may also be explained from another perspective. Regarding the activity-based character of the examined cases, the EEE may also be viewed as sub-ecosystems inside the school ecosystem (Regele and Neck, 2012). In that sense, resistance of internal actors to collaborate may be related to the competition with other sub-ecosystems in the school (for resources, teaching hours and influence, etc.).

Consequently, the results of our analysis call for the consideration of a wider context to understand the motivation of pupils and teachers. A broadened context would consider all internal and external actors, who are directly involved in the creation, development and continuity of entrepreneurship education. This would open up research perspectives based on a local systemic analysis (the school and its environment). Research based on an inventory of actors of the ecosystem and their interactions would serve to 1/ identify what limits and drives the emergence of a ’teacher-leadership’; 2/ better understand the motivation of single actors of the ecosystem (directors, coordinators, teachers, staff, pupils/students, external professionals, entrepreneurs, parents); 3/ understand how the single sub-ecosystems may outgrow competition for the benefit of collaboration.

Education For and Through Entrepreneurship

Moberg (2014) found that education for entrepreneurship, focusing on content and cognitive skills, positively influences pupils’ entrepreneurial intentions but has a negative impact on their school engagement. He also found that education through entrepreneurship, focusing on pedagogical orientation and non-cognitive entrepreneurial skills, has the opposite impact. Looking at the perceptions of the actors in our case study we made a confusing discovery. The described contents of education point towards an education for entrepreneurship using knowledge-based approaches, while the identified key values indicate learning through entrepreneurship, based on social skills and an action-learning orientation. A response may be found in the reflections of Gibb (2007), stating that entrepreneurship should be seen neither as only “business-like” in the formal administrative sense, “nor should it be taken to be synonymous with core skills or transferable personal skills. It is more than both.” (ibid, 2007, p. 1). He emphasizes the existence of multiple goals and outcomes, ranging from pure new venture creation to development of personal skills. In any case, the needs of the audience need to be considered.

These observations open up new research perspectives. Entrepreneurship education programmes are usually designed by one leader or a small group of leaders. Future research may investigate experiences where educations are co-designed by all actors and most importantly by the learner’s. This would imply a shift from a top down organisation towards a more horizontal and flexible bottom up approach.

EEE As an Individual Initiative?

Regarding the density of networks and connections, we identify eight out of nine EEE that rest upon very few individuals, sometimes just one person. These cases were described by the OECD as best practice cases and seem to be no exceptions. This points towards organizational limitations and the difficulty to spread an entrepreneurial culture within the educative ecosystem. For parents, the literature shows that their decision to involve in the programme is linked to the extent to which they believe themselves to be invited to participate actively in the educational process (Hoover-Dempsey, 1997). In line with Räty et al. (2016), we suggest actively inviting and involving all actors, especially other teachers and parents, in the creation of an EEE at the earliest stage. At the same time, to avoid jealousy and the fear of lacking recognition, they need to be reassured about the possible co-existence of other sub-ecosystems (other subject areas, projects, etc). It is also important to encourage them to create synergies with their respective fields of expertise. This aspect should be addressed as early as possible and will depend on the director’s readiness to let parents interfere in the school’s life. In line with studies on “entrepreneurial schools” (Leffler and Näsström, 2014; Hörnqvist et al., 2014; Ruskovaara et al., 2015; Seikkula-Leino et al., 2010, 2015; Penaluna et al., 2015) we notice that the more open schools/programmes are towards external actors and ideas, the more the educations are diversified. They possess heterogeneous actors and have positive effects on teachers and pupils’ engagement in the learning process.

Further research may investigate the effects of collective actions on the learner’s engagement by analysing different levels of interaction: 1/Relations of connection between members of the EEE (members know each other and exchange resources if needed); 2/Collaborative relations (members share their competences to accomplish a shared task like a course); 3/ Cooperative relations (members of the EEE chose to help each other to build a common project that is larger than the sum of their individual competences).

Limitations and Conclusions

Our study presents a picture of the moment in the evolution of entrepreneurial education ecosystems of primary and secondary education, as well as vocational training in Europe. This study presents a scientific attempt to define and understand the functioning of entrepreneurship education as an ecosystem.

Our research does have some limitations. The small research sample certainly presents the first limitation given the large number of entrepreneurial learning initiatives in European schools today. Second, we cannot predict the extent to which the selection of cases has impacted the outcomes of the study; however, we did reach significant theoretical saturation in the data collection process, which may allow for a careful transfer of findings to further initiatives on ecosystems. Third, we used a multi-dimensional model to measure a highly complex and dynamic reality; the results will remain incomplete and their transferability arguable. Furthermore, we did not place the examined programmes within a regional or national context. Our purpose was to draw a general picture of the examined cases. Further studies could examine regional particularities and look at their impact on the EEE.

That said, the article contributes to the comprehension of what characterizes entrepreneurship education it contributes to the following ecosystems in a social context. More precisely, it contributes the following:

Profiles and roles involved in EEE: We confirmed a total number of 11 types of actors and 3 core actors to be involved in EEE (figure 2).

The nature of their relationships: their motivations, social proximity, visions and values, as well as the targeted competences and applied pedagogies.

New research tools to analyse EEE: The EEE-Model consisting of 6 key dimensions (figure 1) to qualitatively investigate an EEE, and a proximity map (figure 2), to raise an inventory of actors of the ecosystem and for possible qualifications of different types of EEE.

We state that the process of filling out proximity maps proved to be a useful exercise to stimulate reflection on and awareness of other actors in the ecosystem and how the single actors judge their own and other actors’ involvement. In the process of developing a school’s EEE, the map could indeed be used to expand awareness of existing actors and spur reflection on potential actors to be stronger involved. The instruction to fill out the map could be adapted as follows: “Ideally, which actors would you like to see involved in entrepreneurship education, and how close?” To the same extent, the EEE-Model can serve as a tool for reflection on the status quo of an EEE, but also to compare and align individual preferences towards a common objective and vision of an EEE.

We note the discrepancy between a growing interest in and importance given to EEE in research and practice, and a reality that often shows standalone actors with high engagement and at best support from the school director. Unless a school’s existence is dedicated to entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial learning (the case of one Finnish school and partly one Spanish school), the legacy of an entrepreneurship education ecosystem to be more than a sub-ecosystem within the school remains arguable.

Considerable work to invite, engage and reassure staff, parents and external actors needs to be undertaken to help an entrepreneurship activity grow towards an ecosystem status. These initiatives should not neglect other (non-entrepreneurship) activities and should put its focus on entrepreneurial learning as a transversal quality throughout all subject areas. The school director will have a major initiating role in this process. More generally, we confirm the call of Neck and Regele (2012, p. 26) for better coherence within the educative ecosystem by building networks of educational programmes that fit together in a coordinated way. At the school level, our study brought to light the necessity of supporting local teams of teachers who provide impulse and energy to the ecosystem.

Appendices

Appendix

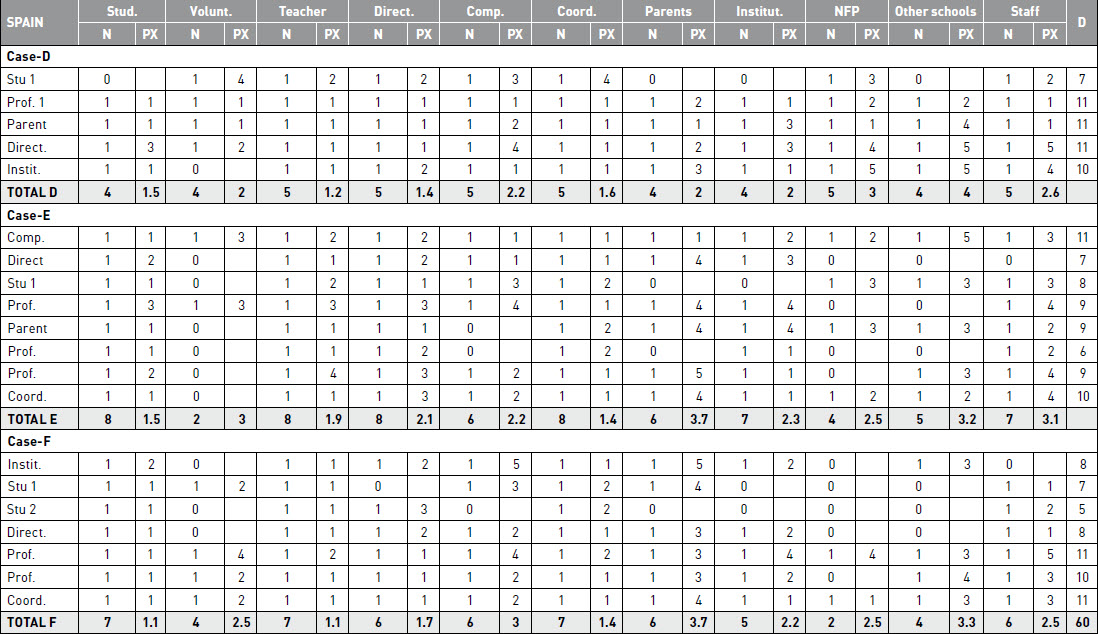

TABLE 5

Proximity scores in Germany

N: number of citation of the actor (1 or 0); PX: proximity score (1 to 5); D: proximity map density (number of actors spontaneously cited, 0 to 11-+).

TABLE 6

Proximity scores in Spain

N: number of citation of the actor (1 or 0); PX: proximity score (1 to 5); D: proximity map density (number of actors spontaneously cited, 0 to 11-+).

TABLE 7

Proximity scores in Finland

N: number of citation of the actor (1 or 0); PX: proximity score (1 to 5); D: proximity map density (number of actors spontaneously cited, 0 to 11-+).

Biographical notes

Olivier Toutain : Involved in the professional world of entrepreneurship for 20 years, Olivier Toutain is an associate professor in entrepreneurship and head of the TEG “The Entrepreneurial Garden” centre for experimentation and pedagogical innovation in entrepreneurship (Burgundy School of Business, Dijon). For the past 15 years, he has been conducting research in the field of entrepreneurship education through three main areas: 1/ the social construction of knowledge, cooperation, emancipation and freedom to undertake; 2/ the entrepreneurial educational environment through the study of the training and development of Entrepreneurial Educational Ecosystems (EEE); 3/ artificial intelligence and big data in entrepreneurship education.

Sabine Mueller is a researcher and external lecturer at Burgundy School of Business (Dijon, France). She is also self-employed as a personal development trainer and counselor in several European countries. She completed her PhD in Entrepreneurship Education at the Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen and her research is focused on entrepreneurial learning and how a school environment stimulates this process.

Fabienne Bornard is assistant professor in INSEEC School of Business & Economics, specialised in Entrepreneurship, Strategy and Innovation, with a first part of career as founder of a consultancy and training company dedicated to the development of small businesses. Her research interests are entrepreneurship and more specifically the entrepreneur’s cognition and entrepreneurial education. She is associated to the Entrepreneurship Research Center and Entrepreneurship Education Research Center of EM Lyon and member of the editorial committee of the Revue Entreprendre & Innover.

Notes

-

[1]

See tables 5, 6, 7 in appendix section.

-

[2]

For instance, the spatial dimension of proximity is used with a strategic approach of education (stakeholders’ proximity in higher education, the spatial profile of university-business research partnerships, physical proximity in the classroom...) or with an economist’s approach (e.g., at a regional level: proximity and human capital, working forces and education institutions, proximity, knowledge integration and innovation).

- [3]

- [4]

-

[5]

The interviewees were systematically given the suggestion to add other possible actors to this inventory but none of them did.

Bibliography

- Aldrich, Howard e.; Geoffrey M. Hodgson; David L. Hull; ThorbjØrn Knudsen; Joel Mokyr;Viktor J. Vanberg (2008). “In defence of generalized Darwinism”, Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol. 18, p. 577-596.

- Ansari, Shahid; Jan Bell; Bala Iyer; Phyllis Schlesinger (2014). “Educating entrepreneurial leaders”, Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, Vol. 17, N° 2, p. 31.

- Audretsch, David B. (2007). The entrepreneurial society, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Birdthistle, Naomi; Briga Hynes; Fleming Patricia (2007). ’Enterprise education programmes in secondary schools in Ireland: A multi-stakeholder perspective’. Education+ Training, Vol. 49, N° 4, p. 265-276.

- Blenker, Per.; Elmholdt, Stine. T.; Frederiksen, Signe. H.; Korsgaard, Steffen.; Wagner, Kathleen (2014). “How do we improve the methodological quality of enterprise education?”, 3E Conference - ECSB Entrepreneurship Education Conference, Turku, Finland.

- Blenker, Per; Korsgaard, Steffen; Neergaard, Helle; Thrane, Claus. (2011). “The questions we care about: paradigms and progression in entrepreneurship education”. Industry and Higher Education Vol. 25, p. 417-427.

- Boschma, Ron. (2005). Role of proximity in interaction and performance: conceptual and empirical challenges, Taylor & Francis.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. (1977). “Toward an experimental ecology of human development”. American psychologist, Vol. 32, N° 7, p. 513.

- Brush, Candida G. (2014). “Exploring the concept of an entrepreneurship education ecosystem”. In Innovative Pathways for University Entrepreneurship in the 21st Century. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p. 25-39.

- Brush, Candida. G.; Corbett Andrew.; Strimaitis, Janet. (2015). “The heart of entrepreneurship practice at Babson College: The Arthur M”. In Crittenden, Victoria L., et al., eds. Evolving Entrepreneurial Education: Innovation in the Babson Classroom. Emerald Group Publishing, p. 427-442.

- Chapin, F.Stuart; Zavaleta, Erika.S.; Eviner, Valérie.T.; Naylor, Rosamond L.; Vitousek, Peter M.; Reynolds, Heather.L.; Hooper, David U.; Lavorel, Sandra; Sala, Osvaldo E.; Hobbie, Sarah E.; Mack Michelle C.; Diaz Sandra (2000). “Consequences of changing biodiversity”, Nature, Vol. 405, N° 6783, p. 234-242.

- Clark, Burton R. (2001). “The Entrepreneurial University: New Foundations for Collegiality, Autonomy, and Achievement”, Higher Education Management, Vol. 13, N° 2, p. 131.

- Coenen, L.; Moodysson, J.; Asheim, B. T. (2004). “Nodes, networks and proximities: on the knowledge dynamics of the Medicon Valley biotech cluster”. European Planning Studies, Vol. 12, N° 7, p. 1003-1018.

- Colucci-Gray, Laura; Camino, Elena; Barbiero, Giuseppe; Gray, Donald (2006). “From Scientific Literacy to Sustainability Literacy: An Ecological Framework for Education”. Science Education, Vol. 90, N° 2, p. 227-52.

- Corbin, Juliet M.; Strauss, Anselm (1990). “Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria”, Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 13, N° 1, p. 3-21.

- Cummins, Brian J; Dallat, John P. (2004). “Helping teachers to make sense of how enterprise and entrepreneurship may be defined”. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, Vol. 6, p. 88-100.

- Daily, Gretchen C.; Polasky Stephen; Goldstein Joshua; Kareiva Peter M.; Mooney, Harold A.; Pejchar, Liba; Ricketts, Taylor H.; Salzman, James; Shallenberger, Robert (2009). “Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver”, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, Vol. 7, p. 21-28.

- Deci, Edward L. (1972). “Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 22, p. 113-120.

- Deci, Edward L.; Vallerand, Robert J.; Pelletier, Luc G.; Ryan, Richard M. (1991). “Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective”. Educational Psychologist, Vol. 26, p. 325-346.

- Deci, Edward L.; Ryan, Richard M. (2000). “The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior”. Psychological Inquiry, Vol. 11, p. 227-268.

- Dewey, John (1916). Democracy and education, Macmillan Press Limited.

- Dey, Ian (2003). Qualitative data analysis: A user friendly guide for social scientists, Routledge.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen.M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review, Vol. 14, N° 4, p. 532-550.

- Epstein, Joyce. L. (1987). “Toward a theory of family-school connections: Teacher practices and parent involvement”. In K. Hurrelmann, F. Kaufman and F. Loel (Eds.), Social Intervention: Potential and Constraints. New York: Walter de Gruyter, p. 121-136.

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2008). “Entrepreneurship in higher education, especially within nonbusiness studies”, Final Report of the Expert Group, European Commission.

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2013). ’Entrepreneurship education: a guide for educators’, Brussels: European Commission.

- Gibb, Allan A. (1993). “Enterprise culture and education: understanding enterprise education and its links with small business, entrepreneurship and wider educational goals”. International Small Business Journal, Vol. 11, p. 11-34.

- Gibb, Alan A. (2007). Enterprise in education. Educating tomorrow’s entrepreneurs, Pentti Mankinen, p. 1-19.

- Gibb, Allan; GayHaskins; Robertson Ian (2009). “Leading the entrepreneurial university.” NCGE Policy Paper, October, NCGE, Birmingham.

- Gjerding, Allan N.; Wilderom, Celeste PM; Cameron, Shona PB; Taylor, Adam; Scheunert, Klaus-Joachim (2006). “L’université entrepreneuriale”. Politiques et gestion de l’enseignementsupérieur, N° 18, p. 1-30.

- Granovetter, Mark. S. (1973). “The strength of weak ties”. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78, p. 1360-1380.

- Greenberg, Danna; Mckone-Sweet, Kate; Wilson, H. James (2011). The new entrepreneurial leader: Developing leaders who shape social and economic opportunity, Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Greene, Patricia G.; Rice, Mark P.; Fetters, Michael L. (2010). ’University-Based Entrepreneurship Ecosystems: Framing the Discussion’. In The Development of University-Based Entrepreneurship Ecosystems. Global Practices. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 1-11.

- Hagen, Joel Bartholemew. (1992). An Entangled Bank: The origins of ecosystem ecology. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J.

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V; Sandler, H. M. (1997). “Why do parents become involved in their children’s education?” Review of Educational Research, Vol. 67, N° 1, p. 3-42.

- Hörnqvist, Maj-Lis; Leffler, Eva. (2014). “Fostering an entrepreneurial attitude–challenging in principal leadership”. Education+ Training Vol.56, p. 551-561.

- Hutchison, Andrew John; Johnston, Lynne Halley; Breckon Jeff David (2010). “Using QSR-NVivo to facilitate the development of a grounded theory project: an account of a worked example”, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, N° 13, p. 283-302.

- Iansiti, Marco; Levien, Roy. (2004). “Strategy as ecology”. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82, p. 68-78.

- Isenberg, Daniel. (2011). The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship, Institute of International European Affairs, Dublin, Ireland.

- Kenny, Martin; Von Burg, Urs. (1999). ’Technology and path dependence: the divergence between silicon valley and route 128’. Industrial ans Corporate Change, Vol. 8, N° 1, p. 67-103.

- Leffler, Eva; Näsström, Gunilla. (2014). “Entrepreneurial learning and school improvement: a Swedish case”. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education, N° 1, p. 243-254.

- Minniti, Maria. (2005). “Entrepreneurship and network externalities”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, N° 57, p. 1-27.

- Moberg, Kaare. (2014). ’Two approaches to entrepreneurship education: The different effects of education for and through entrepreneurship at the lower secondary level’, The International Journal of Management Education, Vol. 12, N° 3, p. 512-528.

- Moles, Abraham; Rohmer, Elisabeth. (1978). La psychologie de l’espace, 2e éd. Casterman, Paris.

- Morin, Edgar. (2005). Introduction à la pensée complexe, Paris: Seuil.

- Morin, Edgar. (2014). Enseigner à vivre: manifeste pour changer l’éducation, Éditions Actes Sud.

- Morin, Edgar; Hulot, Nicolas (2007). L’an I de l’ère écologique: La Terre dépend de l’homme qui dépend de la Terre, Paris: Editions Tallandier.

- Mueller, Sabine; Anderson, Alistair R. (2014). “Understanding the entrepreneurial learning process and its impact on students’ personal development: A European perspective”, The international management journal, N° 12, p. 500-511.

- Nambisan, Satish; Baron, Robert A. (2013). “Entrepreneurship in Innovation Ecosystems: Entrepreneurs’ Self-Regulatory Processes and Their Implications for New Venture Success”, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, Vol. 37, N° 5, p. 1071-1097.

- Neumeyer, Xaver; Corbett. Andrew C. (2017). “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Weak Metaphor or Genuine Concept?”. In The Great Debates in Entrepreneurship. Emerald Publishing Limited, p. 35-45.

- Oerlemans, Leon; Meeus, Marius. (2005). “Do organizational and spatial proximity impact on firm performance?”, Regional Studies N° 39, p. 89-104.

- Penaluna, Kathryn; Penaluna, Andy; Usei, Caroline; Griffiths, Dinah. (2015). “Enterprise education needs enterprising educators: A case study on teacher training provision”. Education + Training, N° 57, p. 948-963.

- Rae, David; Wang, Catherine L. (2015). ’Entrepreneurial learning: past research and future challenges’. In: Entrepreneurial Learning. Routledge, p. 25-58.

- Räty, Hannu; Korhonen, Maija; Kasanen, Kati; Komulainen, Katri; Rautiainen, Riita; Siivonen, Païvi. (2016). “Finnish parents’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship education”. Social Psychology of Education, N° 19, p. 385-401.

- Regele, Matthiew D.; Neck, Heidi M. (2012). “The Entrepreneurship Education Sub-ecosystem in the United States: Opportunities to Increase Entrepreneurial Activity”, Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, Vol.23, N° 2, p. 25-47.

- Rice, Mark P.; Michael L. Fetters; Greene Patricia G. (2014). “University-based entrepreneurship ecosystems: a global study of six educational institutions”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 18, N° 5/6, p. 481-501.

- Richards, Lyn (2014). Handling qualitative data: A practical guide, Sage.

- Ruskovaara, Elena; Pihkala, Timo. (2015). “Entrepreneurship education in schools: empirical evidence on the teacher’s role”. The Journal of Educational Research, N° 108, p. 236-249.

- Ruskovaara, Elena.; Hämäläinen, Minna.; Pihkala, Timo. (2016). “HEAD teachers managing entrepreneurship education–Empirical evidence from general education”. Teaching and Teacher Education, N° 55, p. 155-164.

- Seikkula-Leino, Jaana; Ruskovaara, Elena; Ikavalko, Markku; Mattila, Johanna; Rytkola, Tiina. (2010). “Promoting entrepreneurship education: the role of the teacher?”, Education+ Training, N° 52, p. 117-127.

- Seikkula-Leino, Jaana; Satuvuori, Timo; Ruskovaara, Elena; Hannula, Heikki (2015). “How do Finnish teacher educators implement entrepreneurship education?”, Education+ Training, N° 57, p. 392-404.

- Smith, David. (1999). “Burton R. Clark 1998. Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational Pathways of Transformation”, Higher Education, Vol. 38, N° 3, p. 373-374.

- Stake, Robert E. (1995). The art of case study research, Sage.

- Strauss, Anselm L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists, Cambridge University Press.

- Toutain, Olivier; Mueller, Sabine. (2015). The Outward Looking School and its Ecosystem. OECD.

- Trudgill, Stephen. (2007). “Tansley, A.G. 1935: The use and abuse of vegetational concepts and terms”, in Ecology 16, 284 307. Progress in Physical Geography, Vol. 31, N° 5, p. 517-522.

- Tuunainen, Juha. (2005). “Contesting a Hybrid Firm at a Traditional University”, Social Studies of Science, Vol. 35, N° 2, p. 173-210.

- Weible, Christopher M.; Pattison, Andrew; Sabatier, Paul A. (2010). “Harnessing expert-based information for learning and the sustainable management of complex socio-ecological systems”. Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 13, N° 6, p. 522-34.

- Willis, A.J. (1994). “Arthur Roy Clapham. 24 May 1904-18 December 1990”, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, N° 39, p. 72-80.

- Zacharakis, Andrew L.; Shepherd Dean A.; Coombs. Joseph E. (2003). ’The development of venture-capital-backed internet companies: An ecosystem perspective’, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol.18, N° 2, p. 217-231.

- Zahra, Shaker A.; Nambisan, Satish. (2011). ’Entrepreneurship in global innovation ecosystems’. AMS review, Vol. 1, N° 1, p. 4.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Olivier Toutain : Impliqué dans le monde professionnel de l’entrepreneuriat depuis 20 ans, Olivier Toutain est professeur associé en entrepreneuriat et responsable du centre d’expérimentation et d’innovation pédagogique en entrepreneuriat TEG «The Entrepreneurial Garden» (Burgundy School of Business, Dijon). Depuis 15 ans, il mène des recherches dans le champ de l’éducation à l’entrepreneuriat via trois axes majeurs : 1/ la construction sociale des connaissances, la coopération, l’émancipation et la liberté d’entreprendre ; 2/ le milieu éducatif entrepreneurial via l’étude de la formation et du développement des Écosystèmes Éducatifs Entrepreneuriaux (EEE) ; 3/ l’intelligence artificielle et le big data dans l’éducation à l’entrepreneuriat.

Sabine Mueller est chercheuse et chargée de cours à Burgundy School of Business (Dijon, France). Elle est également formatrice et conseillère en développement personnel à son compte dans plusieurs pays européens. Elle a obtenu son doctorat en éducation à l’entrepreneuriat à l’Université Robert Gordon d’Aberdeen et ses recherches portent sur l’apprentissage entrepreneurial et la façon dont un milieu scolaire stimule ce processus.

Fabienne Bornard est professeur assistant à l’INSEEC School of Business & Economics, spécialisée en Entrepreneuriat, Stratégie et Innovation, avec une première partie de carrière comme fondatrice d’une société de conseil et de formation dédiée au développement des petites entreprises. Ses intérêts de recherche sont l’entrepreneuriat et plus particulièrement la cognition et l’éducation entrepreneuriale de l’entrepreneur. Elle est associée au Centre de Recherche en Entrepreneuriat et au Centre de Recherche en Education à l’Entrepreneuriat de l’EM Lyon et membre du comité éditorial de la Revue Entreprendre & Innover.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Olivier Toutain Involucrado en el mundo profesional del emprendimiento desde hace 20 años, Olivier Toutain es profesor asociado de emprendimiento y director del centro de innovación pedagógica en emprendimiento TEG «The Entrepreneurial Garden» (Burgundy School of Business, Dijon). Durante los últimos 15 años, ha llevado a cabo investigaciones en el ámbito de la educación empresarial a través de tres áreas principales: 1/ la construcción social del conocimiento, la cooperación, la emancipación y la libertad de emprender; 2/ el entorno educativo empresarial a través del estudio de la formación de los Ecosistemas Educativos Empresariales (EEE); 3/ la inteligencia artificial en la educación empresarial.