Abstracts

Abstract

This article reports on a study about the evolution of SMEs’ Competitive Intelligence (CI) practices, in the French context of a public CI policy. Fifteen Directors of CI programs at Chambers of Commerce were interviewed and 176 SME decision-makers surveyed. An important contribution is a typology of SMEs including perceived constraints, advisors, and attitudes towards CI. We conclude that SMEs find appropriate help through publicly funded programs at the early stages of CI practice, whereas consultants are effective to guide them towards higher levels of performance. The findings are of significance to SME managers, CI providers and policy decision-makers.

Keywords:

- Competitive Intelligence,

- SMEs,

- Public Policy,

- France,

- Typology

Résumé

Cet article présente une étude sur l’évolution des pratiques d’Intelligence Économique (IE) des PME, dans le contexte de la politique publique française d’IE. Ont été interrogés quinze directeurs de programmes d’IE des chambres de commerce et 176 dirigeants de PME. Il en résulte une typologie de PME intégrant contraintes perçues, conseillers et attitudes envers l’IE. Les auteurs concluent que les PME trouvent dans les programmes subventionnés un soutien pertinent aux premiers stades de pratique de l’IE, alors que les consultants sont efficaces aux stades supérieurs. Les résultats intéresseront les gestionnaires de PME, les professionnels de l’IE et les décideurs publics.

Mots-clés :

- Intelligence économique,

- PME,

- Politique publique,

- France,

- Typologie

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un estudio sobre la evolución de las prácticas en Inteligencia Económica (IE) en las PYMES, en el contexto de la política pública francesa de IE. Fueron interrogados quince directores de programas de IE de Cámaras de Comercio y 176 dirigentes de PYMES. De ello resulta una tipología de PYMES integrando las restricciones percibidas, asesores y actitudes hacia la IE. Los autores concluyen que las PYMES encuentran en estos programas subvencionados una ayuda pertinente en las primeras fases de la práctica de la IE, mientras que los consultores son eficaces en las fases superiores. Los resultados interesarán a los administradores de PYMES, a los profesionales de la IE y a las autoridades responsables públicas.

Palabras clave:

- Inteligencia económica,

- PYMES,

- Política Pública,

- Francia,

- Tipología

Article body

Competitive Intelligence (CI) as a public policy for small businesses has been experimented in Canada (Bergeron, 2000a; Calof and Brouard, 2004) Belgium (Larivet and Brouard, 2012) and Switzerland (Bégin, Deschamps and Madinier, 2007), but France has long been regarded as the first country to have tackled this officially and intensively (Dedijer, 1994; Bergeron, 2000b; Smith and Kossou, 2008; Pautrat and Delbecque, 2009; Moinet, 2010, Office of the National Counterintelligence Executives, 2011). In France, funded regional programs, provided primarily via Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCI), started more than 10 years ago, but no rational assessment of SME attitudes has been done since Larivet (2002), a study conducted when CI support programs were in their infancy. Moving the field forward for both practitioners and academics required an inventory of CI manifestations in SMEs in this CI public program environment.

The research purpose of this study therefore was to explore the attitudes of SME decision-makers towards CI and CI policy, their antecedents and possible evolutions in this funded environment. The overarching research question became “what are the manifestations of CI in SMEs operating in a CI public programme environment?” Following a mixed methods methodology and building on previously published typologies, an empirically based framework was developed.

As a result, this paper provides a significant contribution to the CI literature, notably by presenting an original five stage, multi-level CI manifestations typology. This typology can facilitate small business CI support policies in the field for company targeting, needs analysis, and behavior change interventions. Additionally, the typology provides a framework for future research.

The next section presents the theoretical background of the study, which includes the context of the research and prior work. Methodology and results are followed by a meta-analysis and discussion section where results are linked back to the literature. The last section presents the SME manifestation typology and implications for research and practice.

Theoretical Background

The Concept of Competitive Intelligence and the French School of Thought

Competitive Intelligence (CI) is an evolving business process which fundamentally integrates analysis of the external and internal business environment, including competitors, into decision-making to improve business performance (Fleisher and Wright, 2009). It is an entirely legal activity which uses publicly available information (Prescott, 2001; Wright, Pickton and Callow, 2002). CI includes the process of analysis and transformation in addition to the intelligence acquisition (Wright, 2011).

Not to be confused with market research, which is typically customer centric (West, 1999), CI is holistic in nature, involving and drawing on the knowledge from all members of a firm, regardless of hierarchy (Calof and Wright, 2008). Expert execution of CI practice is a primary feature and foundation for the attainment, development and ultimate protection of a firm’s intellectual capital (Wright, 2011).

As with many other countries, French CI practice and philosophy exhibits both US and Scandinavian influences (Favier, 1998; Larivet, 2002; Clerc, 2004; Goria, 2006). However a unique French school of thought has emerged from the work of Martre, Clerc and Harbulot (1994), Carayon (2003), Jakobiak (2006), Smith and Kossou (2008), Larivet (2009) and Moinet (2010). The commonly accepted translation of the French term, Intelligence Économique is only an approximate, if overlapping, conceptual equivalence for the Anglo-Saxon term Competitive Intelligence (Dou, 2004; Larivet, 2006; Salles, 2006). Intelligence Économique is considered a larger concept in France (Baumard, 1991; Bloch, 1996; Jakobiak, 2006) to include counter-intelligence, sometimes called defensive protection or economic security as well as influence techniques such as lobbying (Larivet, 2002). The term Intelligence Économique therefore can easily be seen as being connected with an activity which is both politically, and commercially, motivated. In some cases this has had a detrimental effect, or has caused reluctance, on the part of some SME owners, to adopt CI practices (Larivet, 2006). That said, former Prime Minister François Fillon (Premier Ministre, 2011) stated that the objective for the State was not to practice CI for businesses, but to aid them to practice CI, notably by setting up training programs.

French CI public policy and Chambers of Commerce and Industry Programs for SMEs

Since the early 1990’s CI in France has been viewed as a means of enhancing not only a firm’s competitiveness (Jakobiak, 2006; Smith and Kossou, 2008; Smith, Wright and Pickton, 2010; Wright, 2011) but national competitiveness (Martre, Clerc and Harbulot, 1994; Carayon, 2003; 2006; Smith and Kossou, 2008). The impetus came from French government-sponsored reports by Martre, Clerc and Harbulot (1994) and later by Carayon (2003), which solidified CI as a public policy (Goria, 2006; Jakobiak, 2006; Francois, 2008; Moinet, 2010; Premier Ministre, 2011; Elysée, 2013).

French governments have notably funded SME dedicated CI programs throughout all French regions (Clerc, 2004; Moinet, 2010; Smith, Wright and Pickton, 2010; Larivet and Brouard, 2012) with varying success (Dufour, 2010; Moinet, 2010). Support comes not only from regional State security organizations (Prefects and Gendarmerie) but also from public, quasi-government or private actors with a public mission (Chambers of Commerce, Public Investment Bank, DIRRECTE, UbiFrance).

Among these organizations, the French Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCIs, whose membership is compulsory) have become key players in implementing CI support for SMEs (Smith and Kossou, 2008; Clerc, 2009; Smith et al, 2010; Dufour, 2010). CCI France co-ordinates and represents 123 territorial (local) chambers, 27 regional chambers, in excess of 1.8 million enterprises and enjoys an annual budget circa €4 billion (CCI France, 2013).

CCI CI programs began over 10 years ago (Smith, Wright and Pickton, 2010; Moinet, 2010). In 2005, ACFCI (Assemblée des Chambres Françaises de Commerce et d’Industrie, the former name of CCI France) announced its own national plan for CCI CI programs as an integral part of the national CI plan. CCI funded CI programs then flourished. Their purpose was to change the naivety and inertia that existed in a great number of SMEs and to mobilize local public administrations (Carayon, 2003). Both conventional and non-conventional methods were used to enhance CI awareness, improve SMEs competencies and furnish resources. A non-exhaustive list of these methods includes: Conferences, scholarly or expert speeches, sharing of best practices, workshops on specific issues such as data collection or patents, theatrical sketches, and funding of consultant level input.

Whereas Smith, Wright and Pickton (2010) recognized the on-going innovation and positive results of the CCI programs, Moinet (2010) noted that the ACFCI national plan was never fully deployed. Dufour (2010) acknowledged the political, economic and budgetary constraints which had hampered implementation of the national plan.

Prior CI Typologies and SME Positioning

A simple classification which emerged from the USA, applied to large corporations, has been the reference to Ostriches and Eagles as CI performance types, the most ineffective being termed Ostriches and the most effective being termed Eagles. Introduced and developed by Harkleroad (1996; 1998), this framework was promoted and also published by two notable consulting firms: The Futures Group (Wergeles,1998) and Outward Insights (2005). The sample frame for these studies was circa 100 senior executives from US corporations covering diverse industries. As can be seen from Table 1, the personality descriptors for this typology were not expansive.

Table 1

Ostriches and Eagles Typology (derived from Harkleroad, 1996; 1998)

From their studies of European (including French) and US firms of various size, Rouach (1999) and Rouach and Santi (2001) developed five attitude profiles of CI activity, illustrated in Table 2. On a scale of one to five, ‘sleepers’, showed no planned CI activity with management identifying no need for it. ‘Reactives’ undertook some CI activity but only when facing competitive challenge. ‘Actives’ provided continuous low level CI but with limited funding. The final two profiles were called ‘Assault’ and ‘Warrior’. These types enjoyed substantial resources and a dedicated unit set up to carry out CI activity ranging from patent searches to war gaming. Of Rouach’s sample, most French SMEs were ‘Reactives’ while most US SMEs and many large firms fell into the ‘Actives’ category.

Bournois and Romani (2000) then developed the first survey-based typology (table 3). The sample included 1199 French firms of more than 200 employees. Four groups were identified using two main factors: CI function strategic autonomy (the level of reporting of the CI Head, CI priority) and CI formalization (specific CI budget, indicators, procedures and tools). Bournois and Romani (2000) found that the size of the company was the most influential factor in CI management. They doubted that they could have found someone to answer questions about CI in French SMEs, but still were convinced that CI needed to be practiced in small firm.

Table 2

Five Types of Intelligence Attitudes (derived from Rouach, 1999 and Rouach and Santi, 2001)

Table 3

Typology of CI Practice in French Big Companies before the Settlement of a CI Public Policy (derived from Bournois and Romani, 2000)

Table 4

Typology of CI Practice in UK Firms (derived from Wright, Pickton and Callow, 2002)

Wright, Pickton and Callow (2002) developed an evidence-based typology of CI practices in UK companies covering four strands of CI activity: gathering, attitude, use and location. Illustrated in Table 4, this approach provided a framework for illustrating a firm’s position in terms of its current CI practice, showing how it might incrementally progress. This typology has been applied in a corporate setting (Comai, 2004; Bouthillier and Jin, 2005; Liu and Wang, 2008), in a non-profit context (Hudson and Smith, 2008), for SMEs (Wright, Bisson and Duffy, 2012) and in a country comparison conceptual study (Smith, 2008).

These typologies were not specifically built to describe SMEs CI practices, but subsequent empirical studies have suggested that SMEs rarely correspond to the top categories of previously described typologies (Bournois and Romani, 2000; Rouach, 1999; Rouach and Santi, 2001; Wright, Bisson and Duffy, 2012; Smith, 2012). Studies which have straddled both large companies and SMEs can shed light on the different CI dynamics related to size. According to Saayman et al (2008), size was determined to be an important factor in a successful CI process, whilst the lack of availability by the owner-manager, who normally leads the CI effort, was also stated to handicap SMEs, far more frequently than the expected issues of resources constraints.

In small businesses, Groom and David (2001) indicated informal practices were in place, which realised potential returns. In France, Larivet (2002) surveyed French SMEs before the implementation of CCI CI programs. She identified three types of information management practices: intelligence économique, environmental scanning and inaction. The study findings are provided in Table 5, which revealed that more than 40% of SMEs engaged in very little, almost no, CI activities.

A later study in France by Salles (2006) indicated that SME needs were related to company profile (independent, subsidiary, and activity) company strategy, and the environment. In Canada, Tarraf and Molz (2006) noted significant differences between sectors whilst Larivet and Brouard (2012) reported a low level of practice in Belgian SMEs, but conversely, a greater interest in CI training programs. The story is similar in Turkish SMEs where Wright, Bisson and Duffy (2012) applied the previously cited typology by Wright, Pickton and Callow (2002) extended to include the use of technology for CI and decision-making purposes. That research reported a largely unsophisticated approach at the weak end of the proficiency scale.

We can conclude that despite attempts to research SME CI practices, and results showing differences in practice with big companies, no instruments designed to identify, classify or describe CI practices were specifically conceived to adapt to small businesses specificities. This might have led to bias in the comprehension of CI manifestation in SMEs. Following a very classical approach in small business research, we believe that SMEs are different from big companies, but also that there is a behavioral diversity inside the SME community (Torrès and Julien, 2005). A specific typology was clearly needed to recognize this diversity.

The typology of Larivet (2009) might be considered as an exception, but the author acknowledged that it was incomplete, and that additional new variables describing SMEs behavior were required to fit with the centralized management style that often prevails in SMEs (Julien, 1990). One of those new variables suggested by Larivet (2009) was that the attitude of the manager towards CI. Having taken stock of the prior work typologies, the ambition of this study was twofold. First, to engage with the key informants within the CI public policy programs, and second, to examine the attitudes and behaviors of SME decision-makers.

Table 5

Three Types of SMEs Information Management Practice (derived from Larivet, 2002)

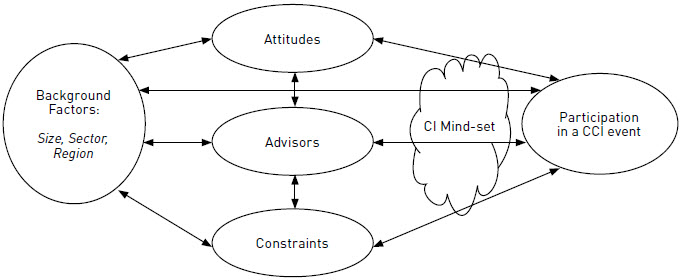

FIGURE 1

Research Design

Methodology

Mixed Methods

Management research is an area where mixed methods arose as conducive to a pragmatic methodological paradigm according to which both quantitative and qualitative methods, techniques, and approaches can be combined in a single study (Cameron, 2009; Cameron, 2011).

According to Greene et al. (1989) there are five major reasons why mixed methods are chosen: Development (a method is used to inform the development of another), complementing (the use of different methods helps to enhance, illustrate or clarify results), triangulation (different types of data are used to corroborate findings), expansion (various methodologies are used to increase the scope of the investigation by covering various components of the question) and initiation (the use of different methods aims to discover potential inconsistencies or new perspectives that may stayed uncovered if employing only one method).

In this research, the overarching question was the identification of CI practices and evolution in SMEs operating in a CI public policy environment. This specific environment required to investigate the two communities involved in this environment: the SMEs themselves, but also representatives of this public policy. More precisely, it was decided to interview CCI CI programs directors, who had both a broad view of the CI public policy and a deep knowledge of SMEs. The number of Directors commanded a qualitative approach. The second population consisted in SMEs managers. This population being bigger, it was possible to opt for a quantitative method which would allow a greatest degree of generalization.

Sub-questions were adapted to each population (see Figure 1), but remained globally the same, with the exception of an additional theme for SMEs managers (CI advisors and participation in a CCI event).

In line with the argument that the findings of a qualitative phase facilitates and validates the development of a research instrument (Greene et al, 1989) for a subsequent quantitative phase, a two-phase, sequential mixed methods study was chosen. Therefore the use of a mixed methods design was supported, not only for triangulation reasons, but also for development and complementarity purpose.

Qualitative Phase

In total, there are 27 regional CCIs in France (French Regions are large geographical and administrative areas) and 126 départemental ones (Each Region is divided into smaller local authorities called Départements). Fifteen CCI CI Program Directors were interviewed. Four of them were working for regional CCIs and ten for départemental ones, all operating for at least one year. The interviews, which were mostly face to face, lasted for approximately two hours. Nvivo was used as a tool to code, organize, and analyze the qualitative data.

The Program Directors’ impression of SME managers’ attitudes towards CI, the terminology they used, and the perceived constraints to conducting CI were all explored. In addition to an interview guide, typologies from Harkleroad (1996) and Rouach (1999) were used as research instruments to entice insight and commentary on the SME types witnessed in CCI programs.

Quantitative Phase

A panel of 176 SME decision-makers was accessed using the Createst panel. Createst is an online panel owned by Netetudes, a well-known provider of online surveys for French companies, as well as for academic research (Assaker and Hallak, 2012; Pechpeyrou, 2013). The sample characteristics are presented in Table 6.

Table 6

Sample Characteristics

As the quantitative phase was conducted after the qualitative phase, it was decided to explore not only the same sub-themes as those addressed in the first phase (types of SMEs, terminology, attitude, constraints), but also the potential associations between the sub-questions. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) produced by Ajzen (1985) served as an authoritative framework to support the exploration of relationships between variables (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010). The TPB postulates that intentions (presented as CI mind-set in Figure 2) are a good predictor of behaviors. In turn, the antecedents of intentions are attitudes towards the behavior, the subjective norms (i.e. the social pressure to conduct or avoid certain behaviors presented as advisors) and the perceived behavioral control (i.e. the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior, presented as constraints).

The variables of the questionnaire were identified from the literature review and qualitative data from the first phase analysis. An adapted TPB framework, specifically applied to this research, is presented in Figure 2. The use of a TPB approach for this study was appropriate because it includes background factors which might influence individual intentions.

The actual behavior in the model was represented by the SME’s participation in a CCI CI event. The intention was not to attempt to predict this behavior, rather to compare SME manifestation variables of those which do participate in CI public policy initiatives, with those which do not. Due to the exploratory nature of this phase, it was decided to test the existence of associations between variables rather than to perform more rigid regression tests. The observed associations were used to enrich the results of the qualitative phase in a meta-inference final step (see Figure 1), following the principles of the mixed-methods approach (no quantitative typology was performed).

Results

Qualitative Results

Qualitative analysis consisted mainly of coding CCI program directors’ answers and counting the frequencies of some items. Table 7 presents selected verbatim accounts or occurrences, and the quantitative variables which were developed from these qualitative results.

Quantitative Results

Quantitative analysis consisted mainly of descriptive statistics and in testing the significance of the relationships between each pair of variables of the model. Table 8 illustrates the significant relationships.

Considering the nature of the variables of our model (nominal and ordinal), both parametric and non-parametric tests were applied to the different pairs of variables. Following Jolibert and Jourdan (2011), chi-square tests were chosen to test pairs of nominal data, Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Spearman’s rank order correlation tests were used for other pairs. All the tests were conducted at a 5% significance level. When a relationship was found significant, descriptive statistics were used to determine if variables were positively associated (both varying in the same direction) or negatively associated (varying in opposite directions).

Meta-analysis and Discussion

Results obtained from the two phases were jointly analyzed to integrate both the perspectives of the CI programs directors and the responses from the SME decision-makers.

FIGURE 2

Research Model for Quantitative Analysis (adapted from Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010)

Table 7

Results from the Qualitative Phase and Quantitative Variable Correspondences

Size

Previous research in France had contradictory results about the role of size to explain CI behavior. Larivet (2002) found no significant relation, nor did Bégin, Deschamps and Madinier (2007). In contrast, Bournois and Romani, 2000; Bulinge (2001); Saayman et al, (2008); and Salles (2006) all highlighted different levels of CI practice between large and small firms with larger sizes demonstrating greater effectiveness and commitment. The CCI CI directors in this study considered 20 to be a pivotal employee count, stating that management engagement became more intense in SMEs which exceeded this number. Nevertheless the quantitative analysis found size was not a significant determinant of SME CI attitudes. The conclusion from this evidence is that as a single factor, size is not a good predictor of a firm’s willingness, or ability, to engage in CI practices.

Attitudes

The CI typologies in Tables 1 and 2 helped to elicit the CCI CI directors’ opinions and insights about positioning SMEs. Varying attitude types were relevant to all of the CCI CI directors, even if they did not claim to work with or witness a particular type. It also encouraged them to share and compare examples of different types. A key finding here was that CI program directors perceived their SMEs to be progressing from one competence level to a more advanced one as a consequence of their CI programs. Specifically this referred to Sleeper/Immune/Ostrich types moving to Reactive/Task Driven types and from this, to Active/Operational types. More importantly, no cases of higher order advances were reported.

Table 8

Significant Relationships Between Variables

Bold (+): Positive significant relationship (both items vary in the same direction)

Bold (-): Negative significant relationship (items vary opposite directions)

The responses of the CCI CI directors emphasized that perceived resistance from many small businesses still exists. They highlighted the lack of time, CI not being a management priority, and their tendency to react to, rather than attempt to prepare for, events. Conversely, a sense that attitudes could, and have, changed was conveyed, and that the roles of CCIs have played a part in this transition. According to the CCI CI program directors, the conceptual ambiguity of CI was a sizable barrier for their SMEs. Despite this, no significant relationships were found between SME attitudes and SME perceived constraints in the quantitative analysis. Received wisdom suggests that finance and time constraints are typically found in SMEs, yet the lack of statistical significance between perceived constraints and other elements of the funded environment would appear to dispel this perception. The results suggest that constraints are convenient excuses for inaction rather than underlying drivers of behavior. The findings of this study have shown that SMEs can, and do, progress in identifiable stages of CI competence within a funded environment.

Advisors

Only a minority of SMEs (10.79%) declared that they had no CI advisor. SMEs without a CI advisor were less likely to have positive attitudes towards conducting a CI needs analysis (p-value=0.000), investing in information management (p-value=0.033) or setting up a CI system (p-value=0.020). Similarly, they were less likely to have participated in a CCI event (p-value=0.000).

The CCI CI directors benefit from considerable exposure to SMEs in terms of CI needs, attitudes towards CI, and the effectiveness of their CI activities. Most have interacted with over a hundred SMEs in some form of their program implementation. With 29% of positive answers, the CCI was ranked by SME decision-makers as the second most used advisor, after consultants. While the attitudes of the CCI CI directors suggested consultants were poorly viewed by SMEs, SMEs themselves had more favourable opinions.

As expected, those SMEs which had participated in a CCI event were more likely to select the CCI as an advisor (p-value=0001). The relative acceptance of the CCIs as advisors contrasts with the findings of Burke and Jarratt (2004) in Australia. They found that SMEs bypassed formal professional advisory services due to a lack of perceived immediate relevance. The CCIs in France, a priori, have not suffered from this point of view. The anchorage of the CCIs in the regions seems to enhance the development of locally based competences.

The findings reveal that CCIs worked closely with CI consultancies and were not seen to be in competition with them. Consultants were the most commonly chosen advice entity by SME decision-makers (31%). SMEs which used CI consultancies were more likely to consider that a CI needs analysis (p-value=0.032) and setting up a CI system (p-value=0.005) would improve company performance. They were also more likely to believe that they were themselves being monitored by the competition (p-value=0.001). Whether positive attitudes towards CI practice cause SMEs to choose consultancies or whether positive attitudes are an outcome of consultancy advice, remains an unresolved ‘chicken and egg’ question. Chartered Accountants were named by 47% of the CCI CI directors and chosen as advisors by 22% of SMEs. SMEs using Chartered Accountants were more likely to recognise the value of setting up a CI system (p-value=0.023). As with other private sector advisors (Consultants), Chartered Accountants, would seem to be a viable source of CI advice for SMEs. In recent years the French professional body of Chartered Accountants has collaborated closely with the French state to increase SME CI awareness and practice (Ordre des Experts-Comptables, 2008). This extension of professional advice services by Chartered Accountants, peculiar to France, may explain the reason behind SMEs making this choice.

With 60% of the CI program directors naming the Gendarmerie, this entity clearly has a role in the French mind-set of CI. It is additional evidence that in France the CI concept has a protection connotation. Leonetti (2008) considered the Gendarmerie to be a key player in both information security and an important bridge between public and private informational exchanges. In contrast however, less than 4% of the SMEs considered the Gendarmerie as a CI advisor. It would appear that whilst the public view of French CI considers the Gendarmerie to be a key player, the SME community is much less convinced. The findings of the quantitative study did not reveal any significant relationship between the users of the Gendarmerie as advisors and their attitudes towards CI practices.

In this study 28% of the SMEs surveyed used the CCIs as a CI advisor, together with a private sector CI advisor (Consultant or Certified Accountant). This showed evidence of public-private collaboration. When including the Gendarmerie, as the French approach to CI as public policy would suggest, the percentage of SMEs using both private and public CI advisors rises to 31%. A stated goal in French CI public policy is to build synergy between public and private sectors (Pautrat and Delbecque, 2009).

Perceived Constraints

None of the five constraints tested had significant relationships with any variable. While previous work has discussed SME constraints with particular reference to CI engagement (Bulinge, 2002; Guilhon, 2004; Salles, 2006), the quantitative data in this study did not identify them as an antecedent to attitudes, or to participation in a CCI CI event. It would seem that while constraints may be on the minds of those SMEs surveyed, and that the CI professionals at the CCIs engaging with them also perceive them as real, they do not translate into, or affect behavior or attitudes. The more objective quantitative data uncovered that perceived constraints had no actual bearing on attitudes or behaviors. These findings are consistent with the results of Nenzhelele and Pelissier (2014). Their research of South African SMEs showed that despite many challenges experienced in implementing and practicing CI, they did, nevertheless, engage with and embrace it as a management philosophy.

Participation in CCI CI Event

The number of SMEs engaging with, or participating in, a CCI CI event was 34.6%. Interestingly, only a few statistically significant relationships between any variable and CCI CI event participation were found to exist, so the model could not be used as an explanation for this behavior. Consequently no regression analysis has been attempted for this study. Those SMEs which did not participate were unlikely to have an advisor for CI (p-value=0.000). Those SMEs which participated in a CCI CI event were more likely to show positive attitudes towards the effectiveness of a CI needs analysis (p-value=0.016). This is consistent with prior research (Salles, 2006) which found CI needs analysis a predominant precursor to engaging with CI practice. Users of the CCIs as advisors were also more likely to have positive attitudes towards CI practice (p-value=0.003).

The findings from the first-hand experience of CI Program Directors together with the analysis of the relationships between the identified variables has significant implications for all the stakeholders in the French funded CI environment.

Contribution and Implications

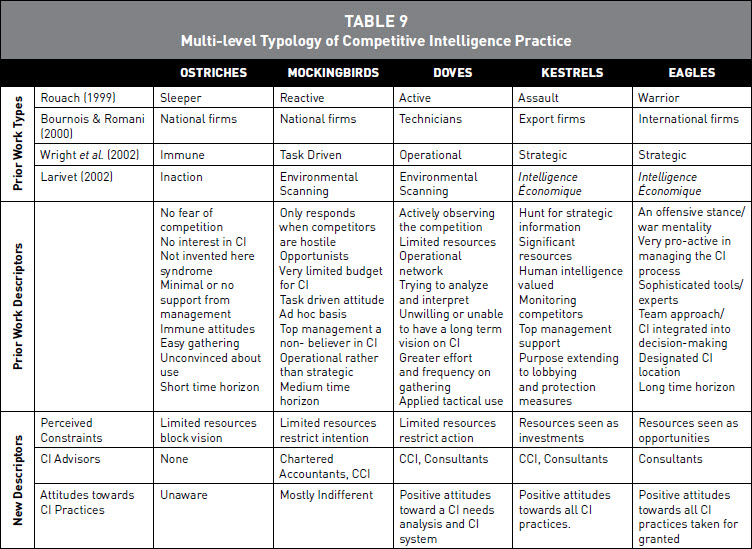

A Multi-level Typology of SME CI Practice

From both the qualitative and quantitative analysis of this study, a multi-level typology depicting SMEs CI competence and practice was developed. In other words, the typology is an outcome of the previous meta-inference, which is an analysis of both the outcomes (inferences) of the qualitative and quantitative phases, as recommended in the mixed methods literature (Cameron, 2009). Based on the two seminal and meaningful types Ostriches and Eagles (Harkleroad, 1996; 1998), it was possible to develop this into five types, in order to capture both the richness and precision of the results garnered from this empirical mixed methods study.

The descriptors from prior typologies were confirmed as pertinent by the qualitative or the quantitative analysis, allowing linkages to be established with these prior typologies. Moreover, new descriptors of SME CI manifestations, identified from the study findings, and related to constraints, advisors and attitude, were added. It was then possible to extend the Ostriches and Eagles analogy to add three further types of SME: Mockingbirds, Doves and Kestrels, with each type defined by the following behavioral characteristics.

Ostriches are in a state of denial. They believe that they have limited resources and this hampers their vision. They consider that they have no need of information management and they do not engage with CI advisors. Not all of the 15 CI program directors had experienced Ostriches, but for others, this was the most common type they had observed. Ostriches think that any required information can be obtained for free, is omnipresent, and not especially relevant for the entity’s future. They are unaware of CI practices specifically and engage in no particular information management practice.

Mockingbirds are reactive and they regard resource constraints as restricting their intentions to conduct CI type practices. Despite their reactive persona, they have some contact with CI advisors, such as Chartered Accountants and their CCI. Their attitude towards CI practice however is typically indifferent, seeing some benefit at times and none at others. The sense of CI being a continuous and continual activity is not fully understood or applied. Their stance on information management practice is typically one of environmental scanning which is further evidence of an arm’s length, passive, approach to observing external events over which the firm has little or no influence.

Doves are numerous. They are active and have a desire for action but they believe that limited resources inhibit their progress. They are likely to be working with the CCIs and consultants to some degree. There is a positive attitude towards CI practice, recognising the benefits of a needs analysis and a dedicated system. There is some attempt to interpret information and to change behaviors but ultimately they are held back both by a lack of conviction and process. Their approach to information management is one of environmental scanning. In other words, they derive information externally on a case by case basis without fully integrating people and systems.

Kestrels are strategic in nature and are at ease with intelligence concepts. Significant resources are available and these are seen as an investment. Consultants are more likely to be used than the CCIs but both could be solicited. Positive attitudes are present and considerable effort is put into monitoring the external and competitive environments. Within the French context described earlier, they practice Intelligence Économique.

Eagles are higher order raptors and provide inspiration to others. Their war mentality, unlimited resources and selective use of consultants are all features which make them exceptional as SMEs. They exhibit positive attitudes towards CI and expect all staff to engage in its practice. They are likely to be partly owned by a larger company from which they would also receive financial and intellectual support. Eagles were rarely seen by the CI program directors but their existence was confirmed.

This expanded, evidence based multi-level typology of CI practice, illustrated in Table 9, provides a valuable tool and targeting mechanism for public policy SME support programs. Tailor-made for SMEs, incorporating attitudes, perceived constraints and advisor relationships, this typology permits firms to position themselves and to strive for higher order CI practice. These are both explicit goals of CI as a public policy in France (Carayon, 2003; Clerc, 2004).

Table 9

Multi-level Typology of Competitive Intelligence Practice

Implications for Research and Practice

This study has resulted in the development of a unique, evidence based, typology on how SMEs can evolve in terms of their CI practices within a funded environment. This opens up at least three avenues for future research. First, recent research in CI has questioned the role of organisational culture on intelligence activities (Tuan, 2013) and has debated the tricky subject of identifying statistical significance between organisational learning and CI performance (Kalantarian, Baratimarnani and Salavati, 2012). Longitudinal studies working in tandem with SME CI support programs could investigate transitions between types. For instance, the role of organisational culture and learning as progressive CI transformations unfold could be considered, as well as obstacles to transition. Second, entrepreneurial capability, although having many definitions (Woldesenbet et al. 2012) is presented as reading the environment, sensing customer needs, technology, and competitive changes (Teece, 2007; Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009; Woldesenbet et al., 2012). In other words, engaging in CI activity. The CI manifestations and SME types presented here as Table 9 and as a direct consequence of this study, provide a new angle for evaluating how entrepreneurial capability evolves in an SME public policy support context. Third, future studies could test whether or not sectors, regions, and differing sized companies to those used in this research, follow the same types and similar manifestations.

Methodological implications relate primarily to mixed method studies in CI. While methods clearly can be mixed (Denscombe, 2008; Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009; Denzin, 2010), the researcher clearly has to justify why this is done (Bazely, 2004). There is a consensus that the CI construct is both broad and interdisciplinary (Silem, 2006, Calof and Wright, 2008; Moinet, 2010; Nenzhelele and Pelissier, 2014; Wright, 2011), therefore, a mixed methods approach may contribute greater insight than mono-methods. Indeed, the qualitative data from the CI programme director interviews was not always consistent with the responses from the SME decision-makers, but these differences provided highly valuable, mutual illumination.

The implications for CI public policy provision is that their focus for SME transformation is likely to be most effective with Ostriches wishing to transform into Mockingbirds and from Mockingbirds to Doves. Here, CCIs can make a difference, whereas higher order transformations towards Kestrels and Eagles may be unrealistic for public support initiatives. Conferences, mass-media communications and SME manager testimonials assist in transforming Ostriches into Mockingbirds. Training, a CI needs analysis and facilitating the setting up of a CI system assist in transforming Mockingbirds into Doves. Higher order types should be directed to private advisors. This would free up the CCI’s limited time and resources to concentrate on where their efforts are likely to be most fruitful, those SMEs making their first or second transformation.

Conclusion

SME support initiatives in CI would seem to be of most benefit when they concentrate on attitude change rather than information exchange initiatives. Attitude change has been shown to be a fundamental critical step in advancing CI performance. When successful, it can anchor behavior change and potentially SME performance in the long run. The evidence suggests that company size, sector, and regions are not determinate indicators of SME CI performance or CI needs. The subjective nature of CI manifestations suggests that a closer relationship between public sector CI providers and SMEs for targeting purposes would be both cost effective and produce higher success outcomes.

The implications for SME decision-makers concern CI advisors, sensitivity to attitudes, and their positioning on the expanded CI manifestations typology. Choice of CI advisors is important for progression in CI practices and these are likely to evolve over time. By consulting the typology, it would be possible for both CCI CI programme directors and SME decision-makers to diagnose their current and desired position. This would provide a platform for the production of a goals and milestone plan which would identify the required resources and investment requirements for both providers and users. These need not be large scale and may be satisfied in the early transformation stages by a mix of both public and private sources, internships and contract specific staff appointments.

The benefits afforded to small firms from government initiated CI support programs manifest a change in attitude and choice of CI advisor, both theoretically and in practice. The findings in this study also imply that CI public support programs can engage meaningfully with SMEs without distorting competition. CI support initiatives, or indeed, SME support initiatives, need to recognize that while constraints can quickly be identified and presented as viable arguments for inertia, they do not necessarily affect behavior in the field.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Dr. Sophie Larivet holds a PhD in business administration. She is an expert in Economic Intelligence, her research focusing on SMEs. Professor and consultant, she published numerous articles and chapters, and is the 2009 laureate of the Economic Intelligence Academy prize. Since 2005, she has been responsible for various programs at École Supérieure du Commerce Extérieur, in Paris. She is a founding board member of the French association of economic security speakers.

Dr. Jamie Smith is Head of Pedagogy at ESCEM Grande École in Poitiers, France. He is an active member of the Entrepreneurial Center of Research at his school, with research interests including Competitive Intelligence (CI) as public policy, decision making in SMEs, and attitude antecedents in CI. He has twice been a speaker at international SCIP conferences and has presented papers at colloquiums on CI across Europe. He has taught CI at IFP school in Paris, integrates CI concepts into his Strategic Marketing courses, and also works with regional Chambers of Commerce in regards to their CI programmes. Jamie completed his PhD at De Montort University, Leceister, UK, in 2012 and has twice been a small business manager himself.

Dr. Sheila Wright is Director of Strategic Partnerships Ltd which has undertaken competitive intelligence (CI) and business development projects in several countries. She has spent over 20 years in higher education, notably as a Reader in CI & Marketing Strategy at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. Sheila has published two books and over 60 refereed journal articles. Her interests centre on securing improved competitive performance and decision making, at individual, organisational and national levels. Sheila was awarded her PhD by Published Works in Competitive Intelligence & Insight Management and is recognised as an influential scholar in the field.

Bibliography

- Ambrosini, Véronique; Bowman, Cliff (2009). “What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management?”, International Journal of Management Review, vol. 11, n°1, p. 29-49.

- Ajzen, Icek (1985). “From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behaviour”, in: J. Kuhl and J. Beckman (Eds), Action-Control: From Cognition to Behaviour, Heidelburg: Springer, p. 11-39.

- Assaker, Guy; Hallak, Rob (2012). “European travelers’ return likelihood and satisfaction with Mediterranean sun-and-sand destinations: A Chi-square Automatic Identification Detector− based segmentation approach”, Journal of Vacation Marketing, vol. 18, n°2, p. 105-120.

- Baumard, Philippe (1991). Stratégie et Surveillance des Environnements Concurrentiels, Paris: Éditions Masson, 181 p.

- Bazely, Pat (2004). “Issues in Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Research”, in R. Buber, J. Gadner and L. Richards (Eds), Applying qualitative methods to marketing management research, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 141-156.

- Bégin, Lucie; Deschamps, Jacqueline; Madinier, Hélène (2007). “Une Approche Interdisciplinaire de l’Intelligence Économique”, Cahiers de Recherche du CRAG, Haute école de gestion de Genève, N°HES-SO/HEG-GE/C-07/4/1-CH, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1083943.

- Bergeron, Pierrette (2000a). “Regional Business Intelligence: The View from Canada”, Journal of Information Science, vol. 26, n°3, p. 153-160.

- Bergeron, Pierrette (2000b). Veille Stratégique et PME: Comparaison des Politiques Gouvernementales de Soutien, Sainte-Foy: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 462 p.

- Bloch, Alain (1996). L’Intelligence Économique, Paris: Éditions Economica, 108 p.

- Bournois, Frank; Romani, Pierre-Jacquelin (2000). L’Intelligence Économique et Stratégique dans les Entreprises Françaises, Paris: Éditions Economica, 300 p.

- Bouthillier, France; Jin Tao (2005). “Competitive Intelligence and Webometrics”, Journal of Competitive Intelligence and Management, vol. 3, n°3, p. 19-39.

- Bulinge, Franck (2001). “PME-PMI et Intelligence Économique: les Difficultés d’un Mariage de Raison”, VSST Conference proceedings, Barcelone, Spain, October 2001, CD-ROM.

- Bulinge, Franck (2002). Pour une Culture de l’Information dans les Petites et Moyennes Organisations: un Modèle Incrémental d’Intelligence Économique, PhD Thesis, Université de Toulon, France.

- Burke, Ian G.; Jarratt, Denise G. (2004). “The Influence of Information and Advice on Competitive Strategy Definition in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises”, Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, vol. 7, n°2, p. 126-138.

- Calof, Jonathan L.; Wright, Sheila (2008). “Competitive Intelligence A Practitioner, Academic and Inter-disciplinary Perspective”, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 42, n°7/8, p. 717-730.

- Calof, Jonathan L.; Brouard, François (2004). “Competitive Intelligence in Canada”, Journal of Competitive Intelligence and Management, vol. 2, n°2, p. 1-21.

- Cameron, Roslyn (2009). “A sequential mixed model research design: Design, analytical and display issues.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, vol. 3, n°2, p.140-152.

- Cameron, Roslyn (2011).“Mixed methods in business and management: A call to the ‘first generation’”, Journal of Management & Organization, vol. 17, n°2, p. 245-267.

- Carayon, Bernard (2006). Patriotisme Économique, Monaco: Éditions du Rocher, 239 p.

- Carayon, Bernard (2003). Intelligence Économique, Compétitivité et Cohésion Sociale: rapport au Premier ministre, Paris: La Documentation Française, 173 p.

- CCI France (2013). Chiffres clefs, available at CCI: http://fr.calameo.com/books/0004751608d0640d3c50d.

- Clerc, Philippe (2004). “Les CCI, Allier Coordination et Autonomie dans le Service à l’Entreprise”, in J.-F. Daguzan and H. Masson (Eds), L’Intelligence Économique: Quelles Perspectives?, Paris: L’Harmattan, p. 73-87.

- Clerc, Philippe (2009). “The Role of the CCI in the French Competitive Intelligence System”, 1st Portuguese-French Meeting on Competitive Intelligence, Fernando Pessoa University, Porto, Portugal, February, 16th available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/porto-ci_cci_clerc1.pdf.

- Comai, Alessandro (2004). “Discover Hidden Corporate Intelligence Needs by Looking at Environmental and Organizational Contingencies”, EBRF Conference Proceedings, Tampere University of Technology, Tampere, Sweden, September 20th-22nd, p. 397-413.

- Dedijer, Stevan (1994). “Opinion: Governments, Business Intelligence – a Pioneering Report from France”, Competitive Intelligence Review, vol. 5, n°3, p. 45-47.

- Denscombe, Martyn (2008). “Communities of Practice, A Research Paradigm for the Mixed Methods Approach”, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 2, n°3, p. 270-283.

- Denzin, Norman K. (2010). “Moments, Mixed Methods, and Paradigm Dialogs”, Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 16, n°6, p. 419-427.

- Dou, Henri (2004). “Quelle Intelligence Économique pour les PME?”, Journal of Business Research, vol. 50, n°8, p. 235-244.

- Dufour, Fanny (2010). Approche Dynamique de l’Intelligence Économique en Entreprise: Apports d’un Modèle Psychologique des Compétences, PhD Thesis, Université Européenne de Bretagne, France.

- Elysée (2013). “Compte-rendu du Conseil des ministres du 29 mai 2013 ”, available at: http://www.elysee.fr/assets/pdf/compte-rendu-du-conseil-des-ministres-du-29-mai-201.pdf.

- Eurostat (2004). “Portrait of the Regions - France - Rhône Alpes – Economy”, available at: https://circabc.europa.eu/webdav/CircaBC/ESTAT/regportraits/Information/fr71_eco.htm.

- Favier, Laurence (1998). Recherche et Application d’une Méthodologie d’Analyse de l’Information pour l’Intelligence Économique, PhD Thesis, Université de Lyon 2, France.

- Fishbein, Martin; Ajzen, Icek (2010). Predicting and Changing Behaviour: The Reasoned Action Approach, New York: Psychology Press, 518 p.

- Fleisher, Craig S.; Wright, Sheila (2009). “Examining Differences in Competitive Intelligence Practice: China, Japan, and the West”, Thunderbird International Business Review, vol. 51, n°3, p. 249-261.

- Francois, Ludovic (2008). Intelligence Territoriale. Paris: Lavoisier, 121 p.

- Goria, Stéphane (2006). L’Expression du Problème dans la Recherche d’Informations: Application à un Contexte d’Intermédiation Territoriale, PhD Thesis, Université Nancy II, France.

- Greene, Jennifer C., Caracelli, Valerie J., & Graham, Wendy F. (1989). “Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs”, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 11, n°3, p. 255-174.

- Groom, Jeremy R.; David, Fred R. (2001). “Competitive Intelligence Activity among Small Firms”, S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, vol. 66, n°1, p.12-20.

- Guilhon, Alice (2004). L’Intelligence Économique dans la PME: Visions Éparses, Paradoxes et Manifestations, Paris: L’Harmattan, 222 p.

- Harkleroad, David (1996). “Too Many Ostriches, Not Enough Eagles”, Competitive Intelligence Review, vol. 7, n°1, p. 23-27.

- Harkleroad, David (1998). “Ostriches and Eagles 2”, Competitive Intelligence Review, vol. 9, n°1, p. 13-19.

- Hudson, Sarah; Smith, Jamie R (2008). “Assessing Competitive Intelligence Practices in a Non- Profit Organisation”, 2nd European Competitive Intelligence Symposium Proceedings, Lisbon, Portugal, March, 27th-28th, p. 1-20.

- Jakobiak, François (2006). L’Intelligence Économique, la Comprendre, l’Implanter, l’Utiliser, Paris: Éditions d’Organisation, 336 p.

- Jolibert, Alain; Jourdan, Philippe (2011). Marketing Research Méthode de Recherche et Etudes en Marketing, Paris, France: Dunod, 624 p.

- Julien, Pierre-André (1990). “Vers une typologie multicritère des PME”, Revue Internationale PME, vol. 3, n°3-4, p. 411-425.

- Kalantarian, Shima; Baratimarnani, Ahmad; Salavati, Adel (2012). “The Relationship between Organizational Learning and Competitive Intelligence on Small and Medium Industries in the City of Kermanshah”, Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, vol. 4, n°6, p. 348-359.

- Larivet, Sophie; Brouard, François (2012). “SMEs’ Attitude Towards SI Programs: Evidence from Belgium”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, vol. 20, n°1, p.5-18.

- Larivet, Sophie (2002). Les Réalités de l’Intelligence Économique en PME. PhD Thesis, Université de Toulon et du Var, Toulon, France.

- Larivet, Sophie (2006). “Intelligence Économique: Un Concept Managérial”, Revue Market Management, vol. 6, n°3, p. 22-35.

- Larivet, Sophie (2009). Intelligence Économique: Enquête dans 100 PME. Paris, France: L’Harmattan, 260 p.

- Leonetti, Xavier (2008). État, Entreprise, Intelligence Économique, Quel Rôle pour la Puissance Publique?, PhD Thesis, Université Paul Cézanne, Marseille, France.

- Liu, Chun-Hsien; Wang, Chu-Ching (2008). “Forecast Competitor Service Strategy with Service Taxonomy and CI Data”, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 42, n°7/8, p. 746-765.

- Martre, Henri; Clerc, Philippe; Harbulot, Christian (1994). Intelligence Économique et Stratégie des Entreprises. Paris: La Documentation Francaise, 167 p.

- Moinet, Nicolas (2010). Petite Histoire de l’Intelligence Économique. Paris: L’Harmattan, 126 p.

- Nenzhelele, Tshilidzi E.; Pellissier, René (2014). “Competitive Intelligence Implementation Challenges of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises”, Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 5, n°16, p.92-99.

- Office of the National Counterintelligence Executives (2011). Foreign Spies Stealing U.S. Economic Secrets in Cyberspace. Report to Congress on Foreign Economic Collection and Industrial Espionage, 2009-2011, available at http://www.ncix.gov/publications/reports/fecie_all/Foreign_Economic_Collection_2011.pdf.

- Ordre des Experts-Comptables (2008). “Intelligence Économique: un Enjeu pour les PME”, Science Indépendance Conscience (SIC), n°262, p. 22-23.

- Outward Insights (2005). Ostriches and Eagles: Competitive Intelligence Usage and Understanding in U.S. Companies, Burlington: Outward Insights, 8 p, available at: http://www.anet.co.il/anetfiles/files/572M.pdf.

- Pautrat, Rémy; Delbecque, Eric (2009). “L’Intelligence territoriale: la rencontre synergique public/privé au service du développement économique”. Revue Internationale d’Intelligence Économique, vol. 1, n°1, p.15-28.

- Pechpeyrou, Pauline de (2013). “Virtual Bundling with Quantity Discounts: When Low Purchase Price Does Not Lead to Smart‐Shopper Feelings”, Psychology & Marketing, vol. 30, n°8, p. 707-723.

- Premier Ministre (2011). Action de l’État en Matière d’Intelligence Économique, Paris: circulaire n°5554/SG, 4 p.

- Prescott, John E. (2001). “Competitive Intelligence: Lessons from the Trenches”, Competitive Intelligence Review, vol. 12, n°2, p. 5-19.

- Rouach, Daniel (1999). La Veille Technologique et l’Intelligence Économique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 127 p.

- Rouach, Daniel; Santi, Patrice (2001). “Competitive Intelligence Adds Value: 5 Intelligence Attitudes”, European Management Journal, vol. 19, n°5, p 552-559.

- Saayman, Andrea; Pienaar, Jacobus; Pelsmacker, Patrick de; Viviers, Wilma; Cuyvers, Ludo; Muller, Marie-Luce; Jegers, Marc (2008). “Competitive Intelligence: Construct Exploration, Validation and Equivalence”, Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives, vol. 60, n°4, p. 383-411.

- Salles, Maryse (2006). “Decision Making in SMEs and Information Requirements for Competitive Intelligence”, Production Planning and Control, vol. 17, n°3, p. 229-237.

- Silem, A (2006). Entretien du Professeur Ahmed Silem, in D. Brüté de Rémur (Ed.), Ce Que Intelligence Economique Veut Dire, Paris: Éditions d’Organisation, p. 136-150

- Smith, Jamie R. (2008). Efficacité de la Veille Concurrentielle et Conséquences Stratégiques, in P. Larrat (Ed.), Benchmark Européen de Pratiques en Intelligence Économique, Paris: L’Harmattan, p. 181-199.

- Smith, Jamie R.; Kossou, Leïla (2008). “The Emergence and Uniqueness of Competitive Intelligence in France”, Journal of Competitive Intelligence and Management, vol. 4, n°3, p. 63-85.

- Smith, Jamie R.; Wright, Sheila; Pickton, David W (2010). “Competitive Intelligence Programs for SMEs in France: Evidence of Changing Attitudes”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, vol. 17, n°7, p. 523-526.

- Smith,Jamie R. (2012). Competitive Intelligence Behaviour and Attitude Antecedents in French Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in a Funded Intervention Environment. PhD Thesis, De Montfort University: United Kingdom.

- Tarraf, Patrick; Molz, Rick (2006). “Competitive Intelligence at Small Enterprises”, SAM Advanced Management Journal, vol. 71, n°4, p. 24-34.

- Teddlie, Charles; Tashakkori, Abbas (2009). Foundations of Mixed Methods Research, London: Sage, 400p.

- Teece, David J. (2007). “Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance”, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 28, n°3, p. 1319-1350.

- Torrès, Olivier and Julien, Pierre-André (2005). “Specificity and Denaturing of Small Business”, International Small Business Journal, vol. 23, n°4, p. 355-377.

- Tuan, Luu T. (2013). “Competitive Intelligence and Other Levers of Brand Performance”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, vol. 21, n°3, p. 217-239.

- Wergeles, Fred (1998). “Ostriches and eagles: Competitive intelligence among US companies”, NACD Directorship, vol. 24, n°2, p.10.

- West, Chris (1999). “Competitive Intelligence in Europe”, Business Information Review, vol. 16, n°3, p. 143-150.

- Woldesenbet, Kassa; Ram, Monder; Jones, Trevor (2012). “Supplying large firms: The role of entrepreneurial and dynamic capabilities in small businesses”, International Small Business Journal, vol. 30, n°5, p. 493-512.

- Wright, Sheila (2011). A Critical Evaluation of Competitive Intelligence and Insight Management Practice, PhD Thesis, De Montfort University, United Kingdom.

- Wright, Sheila; Bisson, Christophe; Duffy, Alistair P. (2012). “Applying a Behavioural and Operational Diagnostic Typology of Competitive Intelligence Practice: Empirical Evidence from the SME Sector in Turkey”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, vol. 20, n°1, p.19-33.

- Wright, Sheila; Pickton, David W.; Callow, Joanne (2002). “Competitive Intelligence in UK Firms: A Typology”, Marketing Intelligence and Planning, vol. 20, n°6, p. 349-360.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Sophie Larivet est docteur en sciences de gestion, spécialiste de l’intelligence économique en PME. Enseignant-chercheur, consultante, formatrice, elle est l’auteur de nombreux articles et lauréate du prix de l’Académie de l’Intelligence économique. Depuis 2005, elle a exercé différentes responsabilités pédagogiques à l’École Supérieure du Commerce Extérieur, à Paris. Elle est membre fondateur du conseil d’administration de l’association des conférenciers en sécurité économique labellisés Euclès.

Jamie Smith est Directeur de la pédagogie à l’ESCEM Grande École à Poitiers en France. Il est un membre actif du Centre de Recherche Entrepreneuriale de cette école. Ses domaines d’intérêt portent entre autres sur les politiques publiques d’intelligence économique (IE), l’attitude envers l’IE et ses antécédents, et la prise de décision en PME. Il a été deux fois conférencier lors de colloques internationaux de la SCIP et a présenté de nombreux papiers sur l’IE lors de conférences européennes. Il a enseigné l’IE à l’École nationale supérieure du pétrole et des moteurs de Paris, et intègre les concepts liés à l’IE dans ses enseignements de marketing stratégique. Il collabore également avec des Chambres de Commerce régionales. Jamie a soutenu son doctorat à l’Université De Montfort (Grande-Bretagne) en 2012 et a été lui-même deux fois dirigeant de PME.

Sheila Wright est Directrice de Strategic Partnerships Ltd. Son cabinet a mené des missions en intelligence économique (IE) et développement d’affaires dans différents pays. Elle a passé plus de 20 ans dans l’enseignement supérieur, entre autre comme professeur en IE et stratégie marketing à l’Université De Montfort (Grande Bretagne). Sheila a publié deux livres et plus de 60 articles de revues académiques. Ses centres d’intérêt sont le maintien et le développement de la performance concurrentielle, et la prise de décision aux niveaux individuel, organisationnel et national. Sheila est titulaire d’un doctorat sur publications en IE et Insight Management. C’est une universitaire à l’influence internationale dans ce champ.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Sophie Larivet es doctora en ciencias de gestión, especialista en Inteligencia Económica en las PYMES. Profesora-investigadora, consultora, formadora, es la autora de numerosos artículos y ganadora del premio de la Academia de la Inteligencia Económica. Desde 2005, ha tenido diferentes responsabilidades pedagógicas en la École Supérieure du Commerce Extérieur, en Paris. Ella es miembro fundador del Consejo de Administración de la asociación de los conferenciantes en seguridad económica certificado Euclés.

Jamie Smith es director de la pedagogía en la Escuela ESCEM, Escuela Superior de Comercio de Poitiers, en Francia. Es miembro activo del Centro de Investigación Empresarial de esta escuela. Sus centros de interés son, entre otros, las políticas públicas de Inteligencia Económica (IE), la actitud hacia la IE y sus antecedentes, y la toma de decisiones en las PYMES. Ha sido dos veces conferencista en coloquios internacionales de la SCIP y ha presentado numerosos documentos sobre la IE en conferencias europeas. Ha enseñado la IE en la Escuela Superior de Petróleo y Motores de Paris, e integra los conceptos relacionados a la IE en sus cursos de marketing estratégico. Colabora también con las Cámaras de Comercio regionales. Jamie obtuvo su doctorado en la Universidad De Montfort (Reino Unido) en 2012 y ha dirigido PYMES en dos ocasiones.

Sheila Wright es Directora de Strategic Partnerships Ltd. Su oficina ha realizado misiones en Inteligencia Económica (IE) y desarrollo de negocios en diferentes países. Ha pasado más de 20 años en la educación superior, y ha sido profesora en IE y en marketing estratégico en la Universidad de Montfort (Reino Unido). Sheila ha publicado dos libros y más de 60 artículos de revistas académicas. Sus centros de interés son el mantenimiento y el desarrollo del rendimiento competitivo y la toma de decisiones a los niveles individual, organizativo y nacional. Sheila tiene un doctorado en publicaciones en IE y Insight Management. Es una universitaria con influencia internacional en este sector.

List of figures

FIGURE 1

Research Design

FIGURE 2

Research Model for Quantitative Analysis (adapted from Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010)

List of tables

Table 1

Ostriches and Eagles Typology (derived from Harkleroad, 1996; 1998)

Table 2

Five Types of Intelligence Attitudes (derived from Rouach, 1999 and Rouach and Santi, 2001)

Table 3

Typology of CI Practice in French Big Companies before the Settlement of a CI Public Policy (derived from Bournois and Romani, 2000)

Table 4

Typology of CI Practice in UK Firms (derived from Wright, Pickton and Callow, 2002)

Table 5

Three Types of SMEs Information Management Practice (derived from Larivet, 2002)

Table 6

Sample Characteristics

Table 7

Results from the Qualitative Phase and Quantitative Variable Correspondences

Table 8

Significant Relationships Between Variables

Table 9

Multi-level Typology of Competitive Intelligence Practice

10.7202/1007988ar

10.7202/1007988ar