Abstracts

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyse the impact of ‘requisite variety’ of an intercultural team on its effectiveness. Using a qualitative, longitudinal case-study method, five successive intercultural teams in one international company are analysed in order to question the effectiveness of the teams from the perspective of requisite variety. The results show that requisite variety is a necessary condition for team effectiveness. Yet, requisite variety is not easily actionable, and team processes moderate the link between requisite variety and team effectiveness. The team also needs enough time for forming, storming and norming, before requisite variety can have a positive impact on performing the task.

Keywords:

- law of requisite variety,

- requisite variety,

- intercultural teams,

- complexity,

- diversity,

- case study,

- team effectiveness

Résumé

L’objectif de cet article est d’analyser l’impact de la « variété requise » d’une équipe interculturelle sur sa performance. Pour ce faire, nous analysons cinq configurations successives d’une équipe interculturelle dans un groupe international, en nous appuyant sur une étude de cas qualitative et longitudinale. Les résultats montrent que la variété requise est une condition nécessaire à la performance de l’équipe. Or, la variété requise n’est pas facilement actionnable, et des processus d’équipe modèrent le lien entre la variété requise et la performance de l’équipe. L’équipe doit aussi avoir suffisamment de temps pour passer les phases de formation, turbulences et normalisation avant que la variété requise ne puisse avoir un impact positif sur la performance.

Mots-clés :

- loi de la variété requise,

- variété requise,

- équipe interculturelle,

- complexité,

- diversité,

- étude de cas,

- performance de l’équipe

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es analizar el impacto de la “variedad requerida” de un equipo intercultural sobre su desempeño. Utilizando un estudio de caso cualitativo y longitudinal, analizamos cinco configuraciones sucesivas de un equipo intercultural en una empresa internacional. Los resultados muestran que la variedad requerida es una condición necesaria para el desempeño del equipo. No obstante, la variedad requerida no es fácilmente utilizable, y los procesos de equipo regulan el nexo entre ésta y el desempeño del equipo. Además, el equipo debe pasar el suficiente tiempo por las etapas de formación, de turbulencia y de normalización antes que la variedad requerida pueda tener un impacto positivo en el desempeño.

Palabras clave:

- ley de la variedad requerida,

- variedad requerida,

- equipo intercultural,

- complejidad,

- diversidad,

- estudio de caso,

- desempeño de equipo

Article body

Intercultural teams are considered by both scholars and practitioners as the answer to many challenges linked to globalization and complex business environments (Schneider and Barsoux, 2003). But it is a considerable challenge to get intercultural teams to function, and many do so poorly (Distefano and Maznevski, 2000).

The aim of this paper is to analyse the impact of team ‘requisite variety’ on team effectiveness. We define team ‘requisite variety’ of a team as the fit between a team’s composition regarding differences among team members, and the complexity of the team’s task. This goes beyond the more commonly used concept of demographic diversity in so far as the degree of variety is analysed in relation to the complexity of the team’s task, and as the categories of diversity are considered in relation to the nature of the task.

Longitudinal access to an intercultural team in a global firm permitted to analyse the fit between different levels of team variety and task complexity, and its impact on team effectiveness. Qualitative findings gathered over five years suggest that requisite variety is a necessary condition for intercultural team effectiveness, but is not a sufficient one in order to make a team succeed. Well-known team processes may influence the expression of the team’s variety, which entails process losses.

We will proceed as follows. In section 1 we review literature on intercultural team effectiveness and question what value the LRV may contribute to this theory. In section 2 we explain our method, a longitudinal and qualitative case study of five successive intercultural teams in a single organizational setting. Section 3 is dedicated to the presentation of the case and to the data and its interpretation. Discussion is developed in section 4.

Intercultural team effectiveness and requisite variety

Intercultural teams

Teams are specific workgroups that exhibit a high degree of “groupness” or member interdependence (Cohen and Bailey, 1997), and consist of two or more members working interdependently together to execute one or more measurable tasks. Workgroup members perceive themselves as a group and are recognized as such by others, which means that the team has clear boundaries. They are social systems that “engage in multiple, interdependent functions, on multiple, concurrent projects, while partially nested within, and loosely coupled to, surrounding systems” (McGrath, 1991: 151). Between team members, some diversity always exists, though to a greater or lesser extent. Team diversity refers to various interpersonal features such as age, race, gender, education, professional background, personal experience, etc. Intercultural teams are assumed to be even more diverse as members have different cultural origins. Culture refers to socialization within a group. It is often reduced to ethnic or national origins (Kirchmeyer and Cohen, 1992; Watson et al., 1993) with reference being made to the nation in which a person has spent the largest and most formative part of her/his life (Hambrick et al., 1998). But culture can also refer to socialization in any kind of social group (e.g. regional, religious, professional, or based on social class, etc.) as long as members “collectively share certain norms, values or traditions that are different from those of other groups” (Cox, 1993: 6). Thus, culture is a pattern of deeply rooted values and assumptions concerning societal functioning which is shared by an interacting group of people (Adler, 2002; Maznevski et al., 2006). Such cultural values concern broad preferential tendencies (Hofstede, 1980). They affect perception, processing, and interpretation of information and also shape individual behaviours (Hambrick et al., 1998). Thus, intercultural teams are assumed to have more intrinsic features of diversity than other sorts of teams.

Variety of intercultural teams

In the context of organizations and teams, diversity is more frequently evoked than is variety. Both of the concepts generally pertain to “any mixture of items characterized by differences and similarities” (Thomas, 1996: 5). “Heterogeneity”, “variety” and “diversity” are sometimes used without explicit distinction and they refer equally to differences between individuals with respect to characteristics or attributes (Milliken and Martins, 1996; Ely and Thomas, 2001; Jackson et al., 2003). But there are clear differences between these two concepts of diversity and variety.

Diversity concerns the “distribution of differences among the members of a unit with respect to a common attribute like tenure, ethnicity (…) or pay” (Harrison and Klein, 2007: 1200). But this distribution may take different forms, including separation, disparity and variety. Separation concerns for example the differences in opinion among team members. If the disagreement or opposition concerning values is strong, the highest level of separation can be reached, even if only two opinions are opposed. Disparity designates inequality or relative concentration of socially valued assets or resources among team members (e.g. pay or power disparity). The highest level of disparity can be reached even if only one team member is different from all of the others. Variety includes more specifically the “composition of differences in kind, source, or category of relevant knowledge or experience among unit members” (Harrison and Klein, 2007: 1203). The highest level of variety is reached when all possible categories are represented (for example, maximum functional variety means that all functional areas of a company are represented in a team). Thus, variety is one particular sub category of diversity and it is the one this paper focuses on.

Task complexity

Intercultural teams are often set up to cope with the diversity of the environment (Weick and Van Orden, 1990; Webber and Donahue, 2001; Schneider and Barsoux, 2003; Gluesing and Gibson, 2004; Greve et al., 2009), to enhance global efficiency and local responsiveness (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1989; Gluesing and Gibson, 2004; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) and, in particular, to accomplish complex tasks (Gluesing and Gibson, 2004).

Task complexity is a continuum that includes four major elements (Gluesing and Gibson, 2004): task environment (static or changing / uncertain), external coupling (team and task environment linking), internal coupling (team members’ interpersonal relationships) and workflow interdependence. This last criterion means that a task is assumed to be complex when team members make sense, solve problems or collaborate together simultaneously. On the other hand, a task is assumed to be simple when it can be split into several distinct activities, when each activity can be performed separately and when fragmented solutions can finally be combined into a homogeneous finished product.

In organizational contexts, performing a task (e.g. developing a new car model in the automobile industry) might require the participation of people with various degrees of expertise in multiple functional areas (e.g. research and development, marketing, design, production, finance) and on several hierarchy levels. Team members might also come from diverse companies (e.g. the car manufacturer, but also subcontractors and consultants) or countries. Thus, a task can be characterised by both a number of distinct variety types (e.g. functional, hierarchical, organizational or international) and an amount of variety for each type (Harrison and Klein, 2007, 1202) (e.g. concerning functional variety, whether there are two or six functional areas concerned).

Intercultural team effectiveness depends on both team composition and team processes

Team effectiveness includes three components (Hackmann, 1987): the productive outcome (objective fulfilment), the extent to which a team develops as a well-functioning performing unit, and the extent to which individual members become more knowledgeable or skilled as a result of their team experiences.

The dominant thinking about team effectiveness is guided by so-called “input-process-output” models (West and Richter, 2007). The output of the team –its effectiveness – is determined by its input –the composition of the team and the nature of the task– which then undergo several team processes.

Managing team variety means paying particular attention to team composition when setting up a team for a particular task. And “complex work requires managers to pay careful attention to the selection of team members” (Gluesing and Gibson, 2004).

Team processes also play a central role in team effectiveness (Mathieu et al., 2008: 420). Team processes include transition processes (e.g. collective leadership enactment, planning and organizing), action processes (e.g. communication, coordination) and interpersonal processes (e.g. conflict, motivation, confidence building, and affect) (Marks et al., 2001). But team processes also include counterproductive dynamics and process losses such as social loafing (individuals’ tendency of contributing less toward the task because of factors such as equity of effort), within-group conflicts (which decrease satisfaction and reduce motivation) and between-group conflict and competition (West and Richter, 2007). Complex tasks require much more interaction and collaboration than tasks that are more repetitive, and this higher interaction can lead to more conflict (Pelled et al., 1999). Thus, task complexity puts particularly high demands on both team composition and processes.

The question of requisite variety (RV) in international management studies

Intercultural team effectiveness also relies on team composition, which includes team variety. But though scholars have produced interesting insights (Milliken and Martins, 1996; Elron, 1997; Thomas, 1999; Randel, 2003; Jackson et al., 2003), solid theoretical grounding is still missing. Thus, “even small modifications to existing theory could prove useful” (Jackson et al., 2003: 813) and exploring other fields might be helpful to build robust theoretical foundations.

In the context of international management, and intercultural teams, the cybernetic “Law of Requisite Variety” (LRV) (Ashby, 1956) is sometimes evoked as a conceptual framework for theorizing about team composition. For example, Lane et al. (2004: 19) point out that in the context of globalisation, “the appropriate response to complexity is through the deliberate development of RV”. Greve et al. (2009) quote Ashby and argue that multinational companies try to balance requisite levels of cognitive and experiential variety at top management team level with the demands of the international operations. Generally speaking, it is assumed that the principle of RV helps explain why companies intentionally increase team variety in response to complex global environments. Jackson et al. (2003) note that several studies on team diversity consider that diversity helps the team deal with the demands of greater complexity.

But though the LRV seems to offer a good conceptual framework for intercultural business issues (Lane et al., 2004), it is rarely discussed in-depth and its basic assumptions are not elucidated. Discussing whether RV could be used as a framework for intercultural teams requires one to consider the origins of this law.

The Law of Requisite Variety (LRV) as formulated in the field of cybernetics

The LRV was first stated by William Ashby in 1956. It can be explained in the following words: let D1 and D2 be two systems and V1 and V2 their respective varieties. The term of “variety” will be used to designate either the number of distinct elements included in a single system, or the number of possible states it can assume. For instance, the variety of a simple electric system that can either assume states “on” or “off” equals 2. The LRV states that in order to control a system, its variety must be controlled. System D1 can only be fully controlled by system D2 provided that the latter’s variety (V2) is equal or superior to the former’s variety (V1). In other words, the number of distinct states that D2 can enter into must be equal to or greater than those of the system D1 (D2≥D1) (Ashby, 1977: 130).

Scholars who refer to Ashby’s work often reduce the LRV to the three following ideas:

Some of the states a system can assume are not desirable, thus it is necessary to control systems in order to avoid undesirable states and to elucidate those which are desirable (Zeleny, 1986: 269).

“Only variety can control variety”. The only way to control, reduce, force down, or absorb variety of a system is through the variety of the controlling system (Beer, 1974: 30; Ashby, 1977: 135; Calori and Sarnin, 1993: 87; Choo, 1997: 30; Choo, 1998: 263).

In order to control a system whose variety is V, another system is required whose variety must be equal to or greater than V (Ashby, 1956; Ashby, 1977; Daft and Wiginton, 1979; Weick, 1979: 188; Le Moigne, 1990; Durand, 1998). In other words, in order to control a system which can assume V states, another system is required that can assume at least each of the same V states, and eventually more.

Can a cybernetic law be used for theorizing on intercultural teams?

The LRV has been widely applied to organization theory to explain how social systems might control complex tasks, and how they might control themselves. But “neither Wiener nor Ashby were experienced or even interested in dealing with social systems. It is only their later interpreters who made the arching leaps which the founders never cared to make” (Zeleny, 1986: 270). Zeleny assumes that, because RV is presented as a law, many scholars in the field of management and organization theory confer a universal value on it. He criticizes the opportunistic and sometimes abusive use of the LRV. But authors have not addressed whether a law from systems, as defined in cybernetics, is relevant for social systems as defined in social sciences.

Indeed, the very idea of a law in management and organization theory makes little sense. Within the modern view of science, a law designates a general formula stating a correlation between physical phenomena, and confirmed by experiment. By extension, a law designates a sine qua non condition, an essential and constant principle. In management and organization theory, where contingency is a basic principle, such essential, irrefutable conditions do not exist. The very idea of constancy does not really make sense as it might in physics and cybernetics. Thus, even if the principles of RV could be transferred, it would be more appropriate to refer to it as a concept rather than a law. It approaches the concept of “fit” in contingency theory (Drazin and Van de Ven, 1985), which is one of the most enduring ideas in the field of organization theory (Drazin and Van de Ven, 1985).

Using the concept of requisite variety in the context of intercultural teams means that in order to perform a task, a team’s variety should fit its task’s complexity. Figure 1 presents the observation grid that over five years was applied to analyse the effectiveness of an intercultural team in charge of an ERP development in a multinational group.

Figure 1

Conceptual framework of the linkage between requisite variety and team effectiveness

Method: a longitudinal case study

This research is based on qualitative data collected and analysed within a single, longitudinal case study. The case studied here is that of an international team, named Global Way team (GWt), managing an enterprise resource planning (ERP) project in an industrial multinational group, here called Alpha.

A qualitative, longitudinal case study

Qualitative research permits to go beyond observable behavior and to understand the meaning and beliefs underlying action. Qualitative methods help theory-generation in immature fields because they allow the researcher to obtain more meaningful results about “soft” inter-relationships between core factors (Marschan-Piekkari and Welch, 2004: 6). This is what is needed for a better understanding of functioning of intercultural teams.

When analyzing a complex phenomenon within its context, case study research appears to be an appropriate strategy. “A case study is an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, when the boundaries between the phenomenon and context are not clearly evident, and in which multiple sources of evidence are used” (Yin, 1989: 23). Case study research is capable of providing testable, novel and empirically valid theory (Eisenhardt, 1989).

There is no consensus among scholars concerning the number of cases needed in order to answer a research question. Science is a process including theory generation through inductive methods, followed by the testing of these theories. Single case studies are one element of this process among others, and their use is most valuable at the beginning of the inductive phase of the process. They frequently permit interesting advances in the knowledge of organizations (Dyer and Wilkins, 1991) because they allow context to be taken into account; in-depth analysis and description are possible. Stake (1994) points out that the mere uniqueness of a case justifies this method. Multiple cases are further to be used if the aim is the construction of a general theory (Eisenhardt, 1989; Stake, 1994).

The selection of the case study

When we had the opportunity to study Alpha, we found it largely deserving a case study because of its high level of internationalisation and its recent but intense intercultural interaction within the group. Moreover, its limited size meant it was possible to interview individuals from nearly all functions, many hierarchical levels and several countries. Within the Alpha setting, the case of the GWt appeared to be particularly worth an in-depth analysis. This case is a “good story” in the sense of Dyer and Wilkins (1991): it has the potential to generate helpful theory for intercultural management. The GWt was an intercultural team working together for several years and confronted with a complex task. The team’s composition, working processes and effectiveness changed several times. Like several authors in the field of intercultural management (see above), we first thought about RV as a metaphor describing this team. We then chose to analyse this concept in depth and completed the data collection on the particular (sub-)case of the GWt, and with respect to the research question addressed here. Finally, within this single case study, the successive phases of the teamwork offer five different settings regarding the conceptual framework (figure 1).

Data collection

We carried out extensive documentary research, including internal documents, in order to triangulate methods. But our case study is based more on half-directive interviews than merely on documents. Thirty half-directive, in-depth interviews were conducted between 2002 (most of the interviews) and 2005 (two interviews) by the authors. Seventeen of those interviewed were members of the GWt, four were executives or supervisors of the team members (e.g. CEO, head of subsidiary, etc.) and nine worked indirectly with this team (e.g. colleagues of the team members; end-users of the successive ERP versions). Seventeen members from Alpha’s French headquarters were interviewed, nine members from the German subsidiary and four from the Spanish subsidiary. When possible (and almost always), the interviews were conducted at the interviewee’s workplace (France, Germany, Spain) and in his or her mother language (but in English or French instead of Spanish).

The aim of the interviews was to collect data on two main themes. The first theme focused on understanding Alpha’s history, organization, strategy and structure, which constitutes the GWt’s context. The second concerned the GWt itself, its composition, task, history, aims, processes, problems and achievements.

Data treatment and analysis

All of the interviews have been fully transcribed. With the aim of content analysis, the interviews and the documents have been coded within N’Vivo, a programme for qualitative data analysis. This process corresponds to the aim of pattern-matching logic where the analyst compares an empirically based pattern of events with a predicted one (Yin, 1989). Chains of process propositions, consisting of hypothesised relations between abstracted events, result from this step (Pauwels and Matthyssens, 2004: 130).

Langley (1999) enumerates seven strategies for sensemaking from process data. In this paper, we use a “narrative strategy” to report the evolution of the GWt and its task. This strategy involves construction of a detailed story from the raw data. Thick description shall allow the reader to judge the transferability of the ideas to other situations. Ideally, the narrative strategy permits one to reproduce in all its subtleness the ambiguity that exists in the situation observed (Langley, 1999). We will combine it with a second strategy, the temporal bracketing strategy. Successive periods of time are delimited in order to structure the description of events. They are not successive phases of a predictable sequential process. Temporal bracketing permits the constitution of comparative units of analysis for the exploration and replication of theoretical ideas (Langley, 1999). These strategies seem appropriate considering the richness of the collected data within a single case setting. They enable the explicit examination of how actions during one period lead to changes in the context that will affect action in subsequent periods.

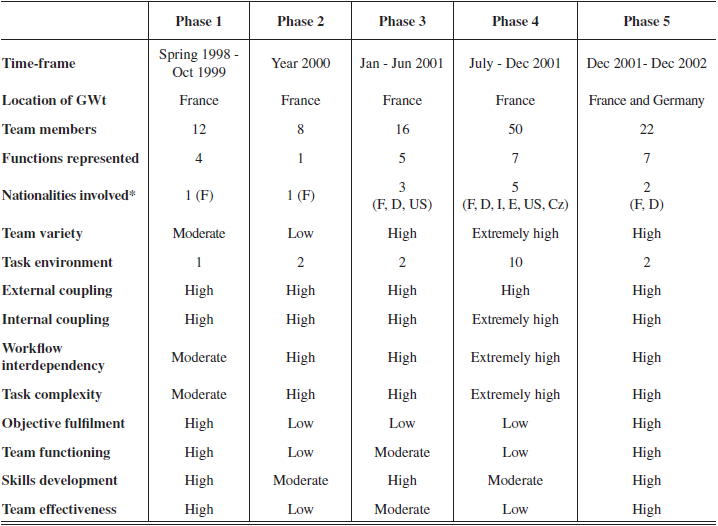

The story of the GWt will be analysed in a step by step manner. Our aim is to analyse whether the conceptual framework of RV (cf. Figure 1) corresponds to the GWt at each period of the process. The observation grid we used to implement this conceptual framework is provided in table 1.

Table 1

Observation grid of the linkage between requisite variety and team effectiveness

The Global Way team and its task: the story of multiple levels of variety

The organizational context of Alpha, a multinational company

Alpha is a world-wide automobile industry supplier with headquarters in France, employing about 3,200 people. It is the leader in the European market and second world-wide. Alpha is highly international with subsidiaries in 20 countries and 4 continents (Europe, the Americas and Asia). The German subsidiary is the group’s largest with over 1,350 employees, while about 700 people work in the French factories and offices.

Until the end of the 1980s, Alpha was a very polycentric group that suited local markets. Strong local adaptation resulted in both strong cultural differences and great diversity between subsidiaries:

Subsidiaries were essentially located in different countries, and managers and employees were exclusively “locals”, natives from the country. There were no expatriates among Alpha’s employees: all employees working in Germany were German, all employees in Italy Italian, and so forth. One exception was an American woman working at the French headquarters, but she was simply “an American living in France”, and not sent there by the company.

Subsidiaries had different customer portfolios, and customer relations were managed locally.

Subsidiaries had different product offerings, and products were mainly manufactured locally.

Interactions with foreign customers and members from other subsidiaries of the group were scarce.

Subsidiaries had developed different routines and work processes to manage, plan and control local activity, and most of the time, work processes had been created and improved locally.

Subsidiaries used different information systems (IS), and most of the time, IS had been designed, developed, implemented and adopted locally to suit local work processes and needs.

Alpha’s polycentric group structure was adapted to their activities as long as their customers, the automobile manufacturers, were not highly international. Alpha’s organization enabled the group to address its customers’ diverse requirements efficiently. Alpha’s internal diversity corresponded to the market environment diversity.

But the automobile industry considerably changed during the 1980s and 1990s. Alpha’s customers, car manufacturers, became increasingly global and suppliers were expected to be able to provide identical products in all international markets. Not only Alpha had difficulties to answer these expectations, but also Alpha’s subsidiaries sometimes acted as if they were competitors not belonging to the same group. Thus, Alpha’s organization no longer met new customer requirements. Stronger international coordination between activities and subsidiaries became vital. A new CEO was appointed in 1998. He gradually modified the group structure into a matrix organization based on increased cooperation and coordination among subsidiaries, but he also strongly believed in the importance of cultural diversity and local adaptation.

The Global Way team (GWt)

Almost simultaneously with new CEO leadership in 1998 and the need for more intensive cooperation among Alpha’s subsidiaries, the French headquarters’ IT department was considering the eventuality of the “year 2000 bug”. It was also worried whether the local IS, designed and implemented during the 1970s, would be adaptable to the Euro.

Alpha’s new CEO considered that the need for a new IS in France was a good way to make a first step towards globalisation, especially regarding both the group structure and the French IS needs. French IT specialists recommended the introduction of an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system. SAP was chosen because it was the only ERP that could integrate every language, including Japanese, spoken in the Alpha Group, Apart from the language aspect, no cultural or organizational differences between subsidiaries were taken into consideration in the specifications.

The GWt was set up in 1998 to design and implement SAP, to support operations, global coordination and group activity control. Since ERP projects always have a strong impact on organizations, processes and workflows, it was a highly complex task considering internal and external coupling.

At the end of 2006, the ERP was implemented and objectives were fulfilled. But between Spring 1998 and December 2002, the GWt processes and effectiveness were far from being satisfying. The team was greatly off target compared with the initial schedule and budget. Objective specifications had to be changed several times. A compromise between the ERP specifications and end-users’ requirements was difficult to find. Moreover, for several years the ERP project had a very negative impact on the relationship between the different subsidiaries, as well as on the organizational climate. Requisite variety was a main issue for this team.

In the following sections, the GWt story is presented in five chronological phases. Between each phase team variety, task complexity and team effectiveness changed. Thus, requisite variety is discussed for each phase.

Phase 1: The balance between team variety and task complexity

Since the French site needed a new IS before 2000, it was decided that a pilot project would be conducted in France. This decision was a pragmatic one as the complexity of a global IS project was reduced to a smaller project. Popular thought at the time was that this approach would help to more easily manage both the schedule and project budget. Although the pilot project was to take place in France, the overall IS project remained global. The long-term vision was that the French pilot project would be progressively rolled-out and simultaneously deployed in the nine foreign subsidiaries of the group.

The composition of the first GWt was the following:

The project leader, an IT specialist who had a knowledge of IS project management.

Four heads of the main functional departments concerned with the project who had overall knowledge of their departments’ business, strategies, organization, objectives and norms. They provided preferences and directives, and tested preliminary versions.

Four end-user experts from the main functional department concerned with the project. They possessed knowledge of their working processes, functional languages, habits and routines. They provided necessary information to implement the ERP and also tested preliminary versions.

Three IT specialists who were knowledgeable about ERP technology. They parameterised the ERP modules to match the managers’ and end-users’ requirements.

All the team members were French and most of them had long working experience in the French subsidiary.

The GWt worked nearly full-time on the project. It took them a year and a half to design, parameterise and deliver the ERP. The ten SAP modules were deployed simultaneously in the French subsidiary during a single week-end in October 1999. The pilot project was delivered on time. The objectives were fulfilled and the budget was respected. The team felt confident with its performance considering that, typically, ERP projects experience delays, budgets usually increase dramatically, and initial objectives are partially abandoned during the process.

During phase 1, team variety seemed to correspond to task complexity, and the team appeared to be effective at that time. But this pilot project was just a first step towards the development of a group-wide international ERP. As a consequence, the task was much more complex than GWt members imagined at that time.

Phase 2: The broken balance between team variety and task complexity

At the beginning of year 2000, a new subsidiary called Alpha Networks was created to capitalize experience, best-practices and feedback from members of the pilot project and its end-users. The creation of a legal corporate entity underlined the importance of the project and increased GWt independence from the French headquarters. Moreover, Alpha Networks would theoretically be able to improve knowledge capitalisation and coordinate the work of the GWt. A former IT specialist who participated in the pilot project was appointed head of Alpha Networks. Managers and end-user experts who took part in the pilot project had returned to their functional activities. Thus, Alpha Networks was an IT department peopled with French IT specialists.

Alpha Network’s mission was to deploy the French IS in the foreign subsidiaries. Since the German subsidiary was the largest, it was the next implementation site. It was decided that the IS implemented in Germany should be at least 80% identical to the French version. Thus, the French ERP system was presented to the German executives. It was explained that the IS they would be using to manage their operations would be identical to the French version, aside from the language.

Indeed, ERPs are known to reshape all operational processes regardless of cultural considerations. SAP is not compatible with a polycentric strategy, but Alpha executives were not aware of this in the beginning of the SAP implementation, in 1999. When the GWt started and SAP was introduced, strategy changed toward a more geocentric one. These major changes in organization and corporate culture were one of the reasons for the problems encountered by the team. The difficulty of the GWt was to design an ERP in a geocentric way, which means by finding a common means of working for all of the subsidiaries without imposing that used by the French headquarters. This was a major element of complexity of the task –and that is why variety of the team was so important here. But the French manager of the GWt presented the ERP as an ordinary software program, and a virtual organization was presented, based on the French subsidiary model. Nobody in the first GWt had ever imagined that the German organization could be completely different from the French one. Nobody in France seemed to have anticipated that the ERP project could have a very strong effect on the German organization, its management methods, production systems and business flows. German executives were outraged. The ERP did not at all match their local organization and requirements. Having always been independent and self directing within the corporate context, they felt completely misunderstood and frustrated. Discussions turned into open conflict. Finally the German executives simply refused to implement the ERP.

Phase 3: New project objectives and new balance between team variety and task complexity

At the beginning of 2001, it became clear that the first ERP solution would not suit the foreign subsidiaries’ requirements and adaptations would not be satisfactory. A completely different ERP solution was needed for the group. GWt members were very frustrated. They felt helpless faced with the problems. They saw no way of resolving the crisis and did not want to restart the project. The head of Alpha Networks and half of the eight GWt members resigned.

A third ERP team was set up with both French and German members. A French engineer, who was not an IT specialist, was chosen to lead this new GWt that contained considerably fewer IT specialists. But tension grew quickly within the team. The German members were not satisfied with the French leadership and considered that their points of view and work methods were not adequately taken into consideration. A schism was perceivable within the team:

From the French point of view, the Germans systematically criticized and undid the work that had been accomplished by the first GWt.

The Germans felt that the French were unwilling to abandon “their” version of the ERP. They considered that the French members of GWt did not sufficiently take into account the procedures of the German subsidiary. Moreover, the Germans did not appreciate the “French” approach to teamwork as called for by the French team leader. Well-known stereotypes were brought up by both of the national subgroups, concerning precision of schedules and working hours and participative versus directive leadership styles.

Given both the growing tensions between members of the GWt, and the poor results of the team, the leadership was changed once again. Two project managers were appointed:

An American woman who had worked at the French headquarters for several years. She became project head representing the “consultancy” side, meaning SAP.

A German manager who was former director of the German subsidiary IT department. He was appointed project head representing the “customer” side, being Alpha’s subsidiaries. He considered himself more a “businessman” than a “technician” as he was not an IT specialist.

They started developing a jointly defined system for team work. The GWt was divided into sub-teams composed of both German and French members. Each sub-team was to find common solutions for specific sub-tasks of the overall ERP project.

By the end of this third phase of the project, the need for RV was considered for the first time. Managers were finally aware of the complexity of both the task and the organizational environment. The challenge was larger than simply combining subsidiaries. The task was recognized as more complex than an ordinary IT project. It was also a question of corporate strategy and organizational design. The degree of complexity was all the more important, as the previous phases of the project had significantly damaged corporate climate and confidence between the German subsidiary and French headquarters. The need for a better fit between team variety and task complexity was finally recognized. Team variety was assumed to be achieved thanks to national diversity and “consultancy” (IT) and “end-user” distinction.

Phase 4: Task complexity and team variety enlargement

Alpha’s CEO, together with the GWt leaders, realized that the task complexity had been underestimated. They wanted to avoid repeating the mistakes that had been previously made in the project. The final ERP solution not only had to match the French and German organisations, but the group as whole, along with its subsidiaries in ten countries. This dramatically increased the task’s complexity, but for the first time, the task was no longer reduced to sub-tasks. It was considered in its entirety.

Thus, the GWt composition changed once again. The French and German project members were joined by “function leaders” from the Czech, Italian, Spanish and American subsidiaries. Individuals from the Japanese, Chinese and Brazilian subsidiaries were not included because Alpha never expatriated their employees for longer periods, and travelling back and forth between these countries and France was considered too long and costly. Moreover, the members of these subsidiaries did not speak English very well, and this would have made teamwork still more difficult. British members were not included because of the small size of the British subsidiary. Each “function leader”, regardless of his nationality, represented a specific SAP module, which often corresponded to one department (i.e. quality management) and one subsidiary in particular. Up to 50 people were permanent members of the GWt. Work was organized on the basis of a “global template”. First, the GWt was asked to create a consensual virtual organization. Then it would design the future ERP to fit this commonly defined virtual organization.

Up until October 2001, teamwork had been very difficult. In France, the SAP pilot version had already been rolled-out and people used it for daily work. For the French subsidiary, a new ERP project meant additional future changes in their work processes. Above all, it was impossible to reach a consensual vision of a virtual global organization and common working processes. Six months after the GWt had been restructured again, teamwork progressed very slowly. No agreement was found on any detail of the project. Differences between the function leaders’ points of view seemed irreconcilable. Difficulties were also due to the differences in size between the French and German subsidiaries on the one hand (about 1.000 employees each), and the size of the other subsidiaries (fewer than 100 employees each). Internal organization, management, and work processes were very different. The representatives of the small subsidiaries feared that using and administering SAP would immobilise an excessively large percentage of the workforce as compared to the subsidiary’s size. The project was stopped once more. Almost three years after the beginning of the GWt, no tangible progress had been made.

Alpha’s leadership was now completely aware of variety requirements concerning the GWt. Every subsidiary was now recognized as concerned with the project. The task was finally recognized as being highly complex. Previous phases of the project significantly damaged corporate climate and trust between foreign subsidiaries and the French headquarters. Thus, the task complexity had reached a peak.

Stakeholders of the GWt were representatives from every functional and hierarchical level of the organisation, and six out of the ten subsidiaries participated in the project. Thus, the team showed requisite variety, but still performed poorly. Its variety was too big for consensus to be reached and tasks to be performed within a reasonable timeframe. This phase highlights that, in the field of intercultural team management, though RV might be a necessary condition, it is not sufficient for team effectiveness.

Phase 5: Reduction of team variety and task complexity

At the end of 2001, the project was modified once again and its specifications reduced. The team was given the task of coming up with a common solution for the two “big” subsidiaries of the group (e.g. France and Germany). This extensive ERP solution would later be simplified and adapted to the “small” subsidiaries.

A new (a fifth) GWt was set up. Half of the team members were French, and half were German. In other words, representatives from the Czech, Italian, Spanish and American subsidiaries were withdrawn from the project. The bi-national team members worked together full-time. They moved from France to Germany on a weekly basis (so that everyone could live with his or her family for 9 out of 14 days). The bi-national direction played a linking role between the two cultural groups.

By February 2002, the situation had radically improved. Team member satisfaction was high. They had gotten to know each other, had developed common work methods, and managed to design solutions acceptable for both subsidiaries. Several modules of the ERP had already been designed.

At the end of 2002, the new SAP version was implemented in both the French and German subsidiaries. A simplified and adapted version was rolled out in Italy in 2004, in Spain in 2005, and in the Czech Republic in 2006. The remaining subsidiaries (i.e. Great Britain, USA, Brazil, China, and Japan) followed afterwards.

Table 2 gives an overview of the 5 phases of teamwork.

Table 2

Description of the five phases of teamwork

In both phase 1 and phase 5, the team’s variety fitted the task complexity and teamwork provided satisfying results. But there are significant differences between phase 1 and phase 5. In phase 5, team members and leaders were aware of the “true nature” of the task. They knew the complexity of the task had been purposely reduced, in order to make the task do-able in a reasonable time, but that in the long run, the ERP had to be deployed to all of the subsidiaries. As a consequence, the team tried, whenever possible, to find a solution that could be easily adapted to the smaller subsidiaries at a later time. In other words, the team attempted to find uncomplicated solutions.

Moreover, in phase 1, the GWt had no international variety. In phase 5, the two main nationalities (in terms of number of employees) were equally represented. Even though every subsidiary was not represented in phase 5, the GWt managed to design an ERP solution that was easy to adapt to every subsidiary of the group.

Discussion

The aim of this paper is to analyse the impact of RV in an intercultural team on team effectiveness. Our results show that requisite variety is a necessary condition for team effectiveness. Yet, requisite variety is not easily actionable, and team processes moderate the link between requisite variety and team effectiveness.

Requisite Variety is a necessary condition for team effectiveness

Table 3 shows that in three phases of the case study, the main tenants of the LRV contribute to explaining the effectiveness of intercultural teams, but in two other phases, they do not.

Table 3

Synthesis of main results

When team variety and task complexity fit, which means that requisite variety is achieved, the effectiveness of the team was quite good (see phases 1 and 5). But when team variety was clearly inferior to task complexity, effectiveness was very poor (see phase 2). This observation is consistent with the LRV. It suggests that if a team is composed of enough different people to imagine the variety of “states” its task might assume, then the team should be able to perform the task.

When team variety and task complexity did not fit, either team variety was amplified in the subsequent phase (see phase 3 and 4) or task complexity was attenuated (see phase 5). This observation is consistent with previous theoretical propositions suggesting that when fit between team variety and task complexity is lacking, “there are two general strategies, which may be combined: the first is to amplify variety in an organization or a team, and the second is to attenuate variety from the task environment” (Choo, 1997: 30; 1998: 263).

When there was no international variety within the team (see phase 1), the team was unable to understand the complexity of the task and perform it. Incorporating international variety in the team contributed to amplifying its variety (see phase 3), and made it capable of imagining the different states the task might take. This result highlights that the team variety and task complexity do not necessarily have to exactly fit to one another. However, it seems important that every type of variety required by the task is represented in the team. The task, here, had a high level of complexity because of its international nature. International variety in the team was required to master it, but not necessarily a very high level.

When team variety became too great, team management was very difficult, and teamwork progressed very slowly (phase 4). This result highlights the key role of team processes for team effectiveness. It is consistent with previous research on intercultural teams and calls for further analysis of this literature.

The case study shows that the LRV delivers insights concerning the composition of a team with regard to the definition of the task it shall perform. More precisely, it stresses that fit must be sought between task complexity and team variety. On the one hand, if the task complexity is too high for the team to understand and manage it, the team might fail to achieve the task. On the other hand, if the team variety is too high, it can also have counter productive effects that might result in failure.

RV appears as a condition for team effectiveness, in the same way as it has been considered as a favourable condition for knowledge creation or sense-making in other contexts (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Weick, 1995). But the fulfilment of this initial condition does not guarantee successful team processes and/or results.

Requisite Variety is not easily actionable

The balance between team variety and task complexity can be difficult to establish and maintain. In cybernetics, RV is stated as a mathematical equilibrium between two distinct stable and calculable variables. But in social systems such as intercultural teams, variables of variety cannot be easily identified or calculated. They can also be very difficult to recognize, evaluate and anticipate. Team variety results from the differences in observable and non-observable personal characteristics of the team members (Milliken and Martins, 1996). But these characteristics overlap and interact, and a general “measure” of team variety still seems difficult to establish. Several criteria have been developed to evaluate task complexity, but here again, we lack a precise quantitative measure. Moreover, criteria for team variety (e.g. values, age, gender, nationalities, functional background) do not match those for task complexity (i.e. workflow interdependence, task environment, internal and external coupling). Therefore, a transposition of the “law” as such is impossible.

What is needed is fit between task complexity and team variety, but also an adequate level of each of them. Successful interaction and results are more likely when teams are able to achieve a balance between too much complexity and uncertainty on the one hand, and too much routine on the other hand (Earley and Gibson, 2002). Therefore, “managers should create a design that will keep the team ‘at the edge of order and chaos’” (Gluesing and Gibson, 2004). “If a task is too complex it can paralyse a team because members are unable to determine or agree on what actions to take” (Gluesing and Gibson, 2004: 201). In such cases, managers may need to do more to structure the task and determine workable expectations at the outset. Otherwise, team members might quickly “experience information overload and shutdown when faced with more complexity than they can handle” (Gluesing and Gibson, 2004: 201) – (like in phase 2 of the GWt). But managers should also be careful not to make the team too large in an effort to match the complexity of the task. It is tempting to assign too many different people, representing all possible groups (like in phase 4 of the GWt), but complexity of team functioning might become too high.

Team processes moderate the link between Requisite Variety and team effectiveness

Team output like effectiveness is not only influenced by RV and the “input”. It is also influenced by team processes like the capacity of the team to interact, to learn and to create knowledge together. During two phases (phase 3 and 4), the GWt possesses the RV to fulfil its task, but nevertheless, teamwork was not effective. Two types of team processes inhibited effectiveness: interpersonal processes concerning commitment and conflict, and action processes linked to leadership and coordination.

Interpersonal processes: commitment and conflict among sub-groups

During phase 3 of the GWt, conflict between the French and German team members and insufficient cooperation between the team members caused negative results on the affective and productive level. Research on diversity largely acknowledges that the organizational context moderates the link between diversity, group processes and outcome (Kochan et al., 2003). In the Alpha Group, the transition from a polycentric organization to a more standardized group structure was poorly managed, because the aims and concrete implementation of this process were not clearly explained. As a consequence, collaborators from the foreign subsidiaries thought that the objective of the implementation of SAP was to exert a stronger control on their activities. Therefore, the German members were not truly committed to the GWt work during phase 3.

Culturally diverse teams experience strong conflicts (Pelled et al., 1999). Teams consisting of two or more strong, defined subcultures (like the GWt in phase 3) elicit the most entrenched cultural conflicts (Gibbs, 2006). Moderate variety is more likely to lead to polarization than extreme diversity, especially when that diversity is salient.

Diverse teams also find it more difficult to communicate and are less willing to cooperate (Thomas, 1999). When team members decide not to really commit themselves to the teamwork (“social loafing”, West and Richter, 2007), the variety of the team finds no expression in the teamwork. Reasons for social loafing can be a lack of motivation, perceived inequity of rewards or a willingness to make the team fail. This attitude of non-commitment can also be a way of opposing the team leader. During the first half of phase 3, these phenomena occurred and as a result reduced the GWt’s variety. As a consequence, the variety became insufficient for the team to master a complex task.

Action processes: leadership, coordination and coupling

An intercultural team is not merely a group of individuals within which interpersonal processes occur. The team has a task to accomplish, within an organizational setting. By organizing the teamwork and by structuring interaction among team members, the team leader acts on the “coupling” of the team seen as a system. “Coupling” implies that the elements (team members) are connected, “tightly” (rigidly) or “loosely” (weakly, flexibly) (Weick, 1979). Cultural diversity, dynamic structure and geographical dispersion are elements of decoupling in intercultural teams, resulting in more loosely coupled team interactions (Gibbs, 2006). It acts as a centrifugal force that pulls such teams apart.

Tight or loose coupling influences the expression of a team’s variety. Some team leaders let their teams completely express their variety, the different points of view and working methods. Others, on the contrary, restrain the team’s variety by imposing routines on the team that do not take into account the cultural differences, or by refraining certain team members from expressing their opinions. This is what happened in the beginning of phase 3 of the GWt, when a French engineer managed a bi-cultural team in a context of strong tension between the French and the German “sides”.

The LRV provides an incomplete explanation for residual variety of complex systems. “Because social systems are organized systems and their ‘components’ are highly interdependent, their variety can be reduced by discovering or imposing constraints; also, for the same reasons, by increasing their interdependence” (Zeleny, 1986: 270). More complex control phenomena emerge that guide interactions and influence the system’s residual variety. The control exerted on a social system can reduce its variety by forcing it to assume only some of the states it can theoretically or potentially assume (Zeleny, 1986). In organizational contexts, control is exerted by the team manager and the organization’s requirements. Non-participative leadership styles and tight coupling do not permit the group to express its variety.

While excessively tight coupling reduces the team variety, excessively loose coupling also impedes team effectiveness. During phase 4 of the GWt, work was so poorly coordinated and variety of the team so high that finding a consensus became impossible. Maloney and Zellmer-Bruhn (2006) state that effective global teams need to find a balance between self-verification and social integration. Self-verification means that team members recognize the deliberate heterogeneity of the team and acknowledge its presence, and accept therefore loose coupling. Social integration means the finding of common norms and functioning (tight coupling). Bachmann (2006) suggests that effective intercultural teams should be simultaneously tightly coupled within the structural domain (e.g. action processes, cooperation and coordination) and loosely coupled within the cultural domain. During phase 4 of the GWt, coupling in the structural domain was too loose, and the high variety within the team led to the impossibility of finding a consensus.

Time and team life cycles moderate the link between requisite variety and team effectiveness

Time also appears as a key element for understanding the link between requisite variety and intercultural team effectiveness. A team’s life-cycle consists of five distinct stages: “forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning” (Tuckman and Jensen, 1977). Even before it starts performing the task, the team might fail during the preceding phases.

Because of their internal variety, intercultural teams are known to need more time than other teams to validate ideas, participants and procedures, to find a consensus and to set up collective action (Adler, 2002). Variety affects all of the phases of teamwork. On the one hand, requisite variety is necessary to perform the task successfully. But on the other hand it raises difficulties during the stages of forming, storming and norming, and can lead to failure.

Gluesing and Gibson (2004) recommend to “convey a sense of urgency” to the team in order to reduce complexity and maintain task focus. In other words, this “sense of urgency” might help to spend less time on the phases of forming, storming and norming, and focus on performing the task more rapidly. But forming, storming and norming is necessary for members to consider themselves as a team, and efficiently perform the task together. Designing an ERP as it was the case in the Alpha group has a strong impact on organizational language, procedures, and control. Thus, performing such a task requires time to take into account and benchmark the differences between the subsidiaries cultures and practices. And this mainly occurs during the forming and storming stages. During both phases 3 and 4 of the GWt, little attention was paid to norming (inventing shared working styles for the team), and the team failed. Spending more time on forming, storming and norming might have enabled members to better consider variety, and favoured the team’s performance. In phases 3 and 4, the GWt apparently displayed requisite variety, but failed to fulfill the task. The lack of time might be another reason why RV did not explain team effectiveness during these phases.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to question to what extent RV of an intercultural team explains its effectiveness. Though the discussion of existing literature showed that if the LRV can not be used as a “law” in management contexts, an application of the concept of RV to the context of intercultural teams is possible. This means that in theory, the more complex a team’s task is, the higher the variety among team members should be. The longitudinal study of the “Global Way team”, whose task was to set up an ERP for the “Alpha” group, led to the conclusion that RV appears as a condition for effectiveness of the team. RV previously was identified as a favourable condition for knowledge creation or sense-making in other contexts. But RV is not easily actionable. It is difficult to implement and manage. Moreover, RV does not guarantee that the team will be successful. In coherence with existing literature, team processes mediate the link between the RV of the team and its effectiveness. In the case studied here, interpersonal and action processes lead to process losses that made the team fail during phases where RV was observed. These processes also influenced the expression of the team’s variety, which can be different, in social settings, from the “theoretical” variety of the team. Interpersonal processes such as within-group conflict and lack of commitment reduced the expression of the team’s variety, which added to the negative effects of process losses. The discussion also points to the importance of adequate “coupling” in intercultural teams. A balance should be found between tight coupling in the structural area and loose coupling in the cultural area, in order to maintain an adequate expression of the cultural differences between the team members. Requisite variety can have a positive impact on task performing, but the team needs enough time to form, storm and norm before it can focus on task fulfilment.

Managerial implications

Managers need to carefully evaluate task complexity. This evaluation is of great importance and can sometimes be very difficult. A task can reveal itself as being much more complex than was initially perceived. If the complexity of the task is underestimated, there is a serious risk of creating a team whose variety is too low, and that will as a result, perform poorly. If on the other hand the task is too complex, the team variety appropriate for performing the task may be so high that the team becomes impossible to manage. In this case, it can be helpful to divide the task into sub-tasks, but then the team is not confronted by the task in its entirety.

Then, managers should pay a careful attention to team composition. In particular the complexity of the task, the variety of the team should neither be too low nor too high. In intercultural environments, one could assume that the team should include members from as many cultural origins as countries that are concerned by the task. But in many cases, the size and complexity of the team becomes too cumbersome to be managed. If all the cultures concerned by the task cannot be represented in the team, at least some cultural variety should be maintained.

One way to master this trade-off is to “start simply” (by reducing task complexity) and progressively increase both task complexity and team variety.

Management should be particularly attentive to the expression of the team’s variety. A balance should be sought between a clear definition of team rules and procedures on the one hand, and participative leadership styles on the other hand.

Limits and avenues for future research

This single case study is a small step in a long-term process of knowledge development. Two distinct theoretical backgrounds, LRV and intercultural teams, are combined here. Further research is needed to extend the results that emerge from this research. More case studies would be helpful in order to further deepen the understanding of the RV of a team. Further case studies might examine teams working on different sorts of tasks. Here, the main aspect of variety is intercultural / international. Further research projects could focus more strongly on other types of variety.

Managerial recommendations issuing from this study could be more precise if the complexity of the task and the variety of the team were measured with greater accuracy. By analogy with risk analysis, where risk typologies and cartographies help in risk evaluation and management, a method for the evaluation of task complexity variables is likely to be helpful in evaluating team and workgroup RV and will assist in more effectively matching the team with the task.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to four anonymous Management International reviewers for their constructive critique, to Anne S. Bachmann and Ariane Berthoin Antal for precious discussions on former versions of this paper, and to Jean O'Donnell and Edison Loza for help with copy-editing and translations.

Biographical notes

Anne Bartel-Radic is an associate professor in business administration at Université de Savoie, IAE Savoie Mont-Blanc, France, and researcher at IREGE (Institut of Research in Business and Economics). As a German living in France, she has been interested for years in intercultural competence of people and organizations, and in intercultural teams. Her research in the field of intercultural management has been published, among others, in Management International, Management International Review and Revue Sciences de Gestion.

Nicolas Lesca is associate professor in business administration at Université Pierre Mendès France, IAE de Grenoble, France, and researcher at CERAG-CNRS (center for studies and researches applied to management). His has been interested for years in information systems, knowledge management, strategic scanning and weak signals. His research in the field of has been published, among others, in Finance Contrôle Stratégies, Systèmes d’Information et Management, European Journal of Information Systems. Hi also published several books.

Bibliography

- Adler, N. (2002) International dimensions of organizational behavior. South-Western, Cincinnati

- Ashby, W. R. (1956) Introduction to cybernetics. Chapman and Hall, London

- Ashby, W. R. (1977) Variety, constraint, and the Law of Requisite Variety. in Buckley, W. and Rapoport, A. Modern systems research for the behavioral scientist. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, 129-136

- Bachmann, A. S. (2006) Melting Pot or Tossed Salad? Implications for Designing Effective Multicultural Workgroups from a Coupling Perspective. Management International Review, 46, 6, 721-747

- Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S. (1989) Managing across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

- Beer, S. (1974) Designing Freedom. CBC Publications, Ontario

- Calori, R. and Sarnin, P. (1993) Les facteurs de complexité des schémas cognitifs des dirigeants. Revue Française de Gestion, 93. 86-94

- Choo, C. W. (1997) Information management for the intelligent organization: the art of scanning the environment. Information Today, Medford, NJ

- Choo, C. W. (1998) The knowing organization: how organizations use information to construct meaning, create knowledge, and make decisions. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Cohen, S. G. and Bailey, D. E. (1997) What Makes Teams Work: Group Effectiveness Research from the Shop Floor to the Executive Suite. Journal of Management, 23, 3. 239-290

- Cox, T. H. (1993) Cultural diversity in organizations. Theory, research and practice. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco

- Daft, R. L. and Wiginton, J. C. (1979) Language and organization. Academy of Management Review, 4, 2. 179-191

- Distefano, J. J. and Maznevski, M. L. (2000) Creating Value with Diverse Teams in Global Management, Organizational Dynamics, 29, 1, 45-63

- Drazin, R. and VandeVen, A. H. (1985) Alternative Forms of Fit in Contingency Theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30, 4. 514-539

- Durand, D. (1998) La systémique. PUF, Paris.

- Dyer, W. G., Jr. and Wilkins, A. L. (1991) Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: a rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Academy of Management Review, 16, 3, 613-619.

- Earley, P. C. and Gibson, C. (2002). Multinational Work Teams, Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989) Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 4, 532-550.

- Elron, E. (1997) Top Management Teams within Multinational Corporations: Effects of Cultural Heterogeneity. Leadership Quarterly, 8, 4. 393-412

- Ely, R. J. and Thomas, D. A. (2001) Cultural Diversity at Work: The Effects of Diversity Perspectives on Work Group Processes and Outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46, 229-273

- Gibbs, J. L. (2006). Decoupling and coupling in global teams: implications for human resource management. in Stahl, G. K. and Björkman, I. (Eds), Handbook of Research in International Human Resource Management. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing, 347-363.

- Gluesing, J. C. and Gibson, C. (2004) Designing and forming global teams. in Lane, H. C., Maznevski, M. L., Mendenhall, M. and McNett, J. The Blackwell Handbook of Global Management: A guide to managing complexity. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 199-226.

- Greve, P., Nielsen, S. and Ruigrok, W. (2009) Transcending borders with international top management teams: A study of European financial multinational corporations. European Management Journal, 27, 3, 213-224.

- Hackmann, J. R. (1987) The design of work teams. in Lorsch, J. (Eds), Handbook of organizational behavior, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 315-342.

- Hambrick, D. C., CanneyDavison, S., Snell, S. A. and Snow, C. C. (1998) When groups consist of multiple nationalities: towards a new understanding of the implications. Organization Studies, 19, 181-205

- Harrison, D. A. and Klein, K. J. (2007) What’s The Difference? Diversity Constructs as Separation, Variety or Disparity in Organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 4. 1199-1229

- Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s consequences: International differences in work related values. Sage, London.

- Jackson, S., Joshi, A. and Erhardt, N. L. (2003) Recent Research on Team and Organizational Diversity: SWOT Analysis and Implications. Journal of Management, 29, 6. 801-830

- Kirchmeyer, C. and Cohen, A. (1992) Multicultural Groups. Group & Organization Management, 17, 2. 153-170

- Kochan, T., Bezrukova, K., Ely, R. J., Jackson, S., Joshi, A., Jehn, K., Leonard, J., Levine, D. and Thomas, D. A. (2003) The Effects of Diversity on Business Performance: Report of the Diversity Research Network. Human Resource Management, 42, 1, 3-21.

- Lane, H. W., Maznevski, M. L., Mendenhall, M. and McNett, J. (2004) Handbook of Global Management. A Guide to Managing Complexity. Blackwell, Oxford.

- Langley, A. (1999) Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data. Academy of Management Review, 24, 4. 691-710

- LeMoigne, J.-L. (1990) La modélisation des systèmes complexes. Dunod, Paris.

- Maloney, M. M. and Zellmer-Bruhn, M. (2006) Building Bridges, Windows and Cultures: Mediating Mechanisms between Team Heterogeneity and Performance in Global Teams. Management International Review, 46, 6. 697-720

- Marschan-Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. (2004) Qualitative Research Methods in International Business: The State of the Art. in Marschan-Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. (Eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for International Business, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing, 5-24

- Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. and Zaccaro, S. J. (2001) A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes, Academy of Management Review, 26, 3, 356-376.

- Mathieu, J., Maynard, M. T., Rapp, T. and Gilson, L. (2008) Team Effectiveness 1997-2007: A Review of Recent Advancements and a Glimpse Into the Future, Journal of Management, 34, 3, p.410-476

- Maznevski, M. L., CanneyDavison, S. and Jonsen, K. (2006) Global Virtual Team Dynamics and Effectiveness. in Stahl, G. K. and Björkman, I. (Eds), Handbook of Research in International Human Resource Management, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing, 364-384

- McGrath, J. E. (1991) Time, interaction, and performance (TIP). A theory of groups. Small Group Research, 22, 147-174

- Milliken, F. J. and Martins, L. L. (1996) Searching for Common Threads: Understanding the Multiple Effects of Diversity in Organizational Groups. Academy of Management Review, 21, 2. 402-433

- Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The knowledge creating company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Pauwels, P. and Matthyssens, P. (2004) The Architecture of Multiple Case Study Research in International Business. in Marschan-Piekkari, R. and Welch, C. (Eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for International Business, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing, 125-143.

- Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M. and Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict and performance, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44. 1-28.

- Randel, A. (2003) The salience of culture in multinational teams and its relation to team citizenship behaviour. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 3, 1. 27-44

- Schneider, S. and Barsoux, J.-L. (2003) Management interculturel. Pearson, Paris.

- Stake, R. (1994) Case Studies. in Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds), Handbook of qualitative research, London, Sage, 236-247.

- Thomas, A. (1996) Psychologie interkulturellen Handelns. Hogrefe

- Thomas, D. C. (1999) Cultural diversity and work group effectiveness. An experimental study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 2. 242-263

- Tuckman B.W. and Jensen M.A. (1977) Stages of small-group development revisited, Groups & Organization Studies, 2, 419-442.

- Watson, W. E., Kumar, K. and Michaelsen, L. K. (1993) Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 3. 590-602

- Webber, S. S. and Donahue, L. M. (2001) Impact of highly and less job-related diversity on work group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 27, 2. 141-162

- Weick, K. E. (1979) The social psychology of organizing. Addison Wesley, Reading, M.A.

- Weick, K. E. (1995) Sensemaking in organizations. Sage, London.

- Weick, K. E. and VanOrden, P. W. (1990) Organizing on a global scale: A research and teaching agenda. Human Resource Management, 29, 1. 49-61

- West, M. A. and Richter, A. W. (2007). Team Performance, International Encyclopaedia of Organization Studies, http://www.sage-ereference.com/organization/Article_n526.html

- Yin, R. K. (1989) Case study research. Design and methods, London, Sage

- Zeleny, M. (1986) The law of requisite variety: is it applicable to human systems? Human Systems Management, 6, 4. 269-271

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Anne Bartel-Radic est maître de conférences en Sciences de Gestion à l’Université de Savoie, IAE Savoie Mont-Blanc, et chercheur à l’IREGE (Institut de Recherche en Gestion et Economie). Allemande vivant en France, elle s’intéresse depuis des années à la compétence interculturelle des personnes et des organisations, et aux équipes interculturelles. Ses recherches dans le champ du management interculturel ont été publiées, entre autres, dans Management International, Management International Review et la Revue Sciences de Gestion.

Nicolas Lesca est maître de conférences en Sciences de Gestion à l’Université Pierre Mendès France, IAE de Grenoble, France, et chercheur au CERAG-CNRS (Centre d’études et de recherches appliquées à la gestion). Il s’intéresse depuis des années aux systèmes d’information, à la gestion des connaissances, à la veille stratégique et aux signaux faibles. Ses recherches ont été publiées, entre autres, dans Finance Contrôle Stratégies, Systèmes d’Information et Management, European Journal of Information Systems. Il a aussi publié plusieurs livres.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Anne Bartel-Radic es profesora asociada en administración de empresas de la Universidad de Savoie, IAE Savoie Mont-Blanc, Francia, e investigadora en el IREGE (Instituto de Investigación en Gestión y Economía). De origen alemán, actualmente radicada en Francia, sus principales centros de interés por años han sido los equipos interculturales, y la competencia intercultural de personas y organizaciones. Sus investigaciones en el campo de la gestión intercultural han sido publicadas, entre otras, en Management International, Management International Review y la Revue Sciences de Gestion.

Nicolas Lesca es profesor asociado en administración de empresas en el IAE de la Universidad Pierre-Mendès France en Grenoble, Francia, e investigador del CERAG-CNRS (Centro de estudios e investigaciones aplicadas a la administración). Durante años se ha interesado por los sistemas de información, la gestión de conocimientos, las señales débiles, y el análisis estratégico del entorno. Además de ser el autor de varios libros sobre la materia, sus investigaciones han sido publicadas, entre otras, en Finance Contrôle Stratégies, Systèmes d’Information et Management y el European Journal of Information Systems.

List of figures

Figure 1

Conceptual framework of the linkage between requisite variety and team effectiveness

List of tables

Table 1

Observation grid of the linkage between requisite variety and team effectiveness

Table 2

Description of the five phases of teamwork

Table 3

Synthesis of main results