Abstracts

Abstract

The aim of this article is to contribute to the establishment of a sub-field of translation studies, namely a sub-field devoted to the research of intralingual translation. The article’s contribution to this project is both theoretical and empirical. In the theoretical part of the article, an already existing, five-partite typology of intralingual translation is reviewed and on certain points refined. The empirical part is taken up by three case studies, each representing a particular subcategory of intralingual translation. The first study investigates translation between two geographical dialects (American and British English), the second examines the rewriting of a specialized, pharmaceutical product summary into a register aimed at lay readers, and the third investigates the modernization of one of Shakespeare’s plays. A primary concern of the case studies is to chart the range and nature of the translation strategies employed in the transformation of source texts into intralingual target texts. Translation strategies are conceptualized as shifts in the article, and well-known concepts from translation studies are applied in the analyses. The analytical results reflect clear differences, but also certain striking similarities between the types of shifts manifested in the individual cases.

Keywords:

- intralingual translation,

- typology,

- dialects,

- registers,

- translation strategies

Résumé

L’objectif de cet article est de contribuer à l’établissement de la traduction intralinguale comme sous-domaine de la recherche traductologique. L’article apporte une contribution à la fois théorique et empirique à ce projet. La partie théorique se compose d’une revue de la typologie pentapartite actuellement appliquée en traduction intralinguale, ainsi que d’un raffinement de certains de ses critères. La partie empirique comprend trois études de cas, chacune recouvrant l’une des catégories spécifiques à la traduction intralinguale. La première étude se penche sur la traduction entre deux dialectes géographiques (anglais américain et anglais britannique), la deuxième étude examine la retranscription d’un résumé de produit pharmaceutique dans un registre destiné aux non-experts, tandis que la troisième étude est consacrée à l’investigation de la version modernisée d’une des pièces de Shakespeare. Les études de cas s’appliquent à recenser la nature et la portée des stratégies de traduction employées dans la transformation des textes source en textes cible intralinguaux. Dans l’article, les stratégies de traduction sont conceptualisées comme des shifts, alors même que des concepts traductologiques reconnus sont appliqués tout au long des analyses. Les résultats analytiques reflètent de nettes différences, mais aussi des similitudes frappantes entre types de shifts se manifestant dans chaque cas individuel.

Mots-clés :

- traduction intralinguale,

- typologie,

- dialectes,

- registres,

- stratégies de traduction

Resumen

Con este artículo se pretende contribuir con la creación de un subcampo de los estudios de traducción, dedicado a la investigación de la traducción intralingüística. El objetivo es a la vez teórico y empírico. En la parte teórica se revisan y se perfeccionan cinco tipologías existentes de traducción intralingüística. La parte empírica se compone de tres estudios de casos, cada uno representando una subcategoría particular de traducción intralingüística. El primero estudia la traducción entre dos dialectos geográficos (inglés americano e inglés británico), el segundo examina la reescritura de una nota relativa a un producto farmacéutico en un registro destinado a un público no especialista y el tercero analiza la modernización de una obra de Shakespeare. El objetivo principal de estos tres estudios de caso consiste en inventariar la naturaleza y el alcance de las estrategias de traducción adoptadas para transformar los textos originales en textos meta intralingüísticos. En el artículo, las estrategias de traducción se conceptualizan como shifts y los análisis se basan en conceptos muy conocidos de los estudios de traducción. Los resultados revelan claras diferencias, pero igualmente notables semejanzas entre los tipos de shift que aparecen en cada caso.

Palabras clave:

- traducción intralingüística,

- tipología,

- dialectos,

- registros,

- estrategias de traducción

Article body

1. Introduction

This article is concerned with the particular translational phenomenon known as intralingual translation (henceforth INTRA), the language-internal rewriting of a source text (ST) into a target text (TT) with the purpose of neutralizing a potential comprehension barrier. Thus conceived, INTRA is a type of text production that, over the past few years, appears to be growing. The so-called Plain Language Movement in the US, for example, would seem to reflect a recognition on the part of public authorities that there is a need for registerial simplification of certain types of official communication with the public.[1] A parallel initiative in Germany bears witness to the same awareness, with federal authorities being now required to simplify certain types of official documents that are deemed inaccessible for ordinary citizens (Maaß, Rink, et al. 2014: 53). Similarly, EU institutions such as the European Court of Justice (CURIA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) now publish popularized versions of (longer) specialized documents, such as court rulings,[2] and reports on clinical trials[3] of medicinal products authorized for marketing in the EU.

In certain academic fields, however, INTRA is treated with outright suspicion, for instance in literary studies and philosophy, where it is sometimes perceived as an activity that had better not be undertaken at all. Thus, calls for a linguistic modernization of the 19th-century Danish author-philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s works have met with strong opposition from Kierkegaard experts (Libak 2013[4]), and attempts to modernize the language of Shakespeare have been exposed to similar criticism (Crystal 2002; Dean 2016). When it comes to the intralingual versioning of literary works in a different dialect, attitudes are mixed. On the one hand, Denton (2007) strongly advocates for intralingual translation of British literature into American English, pointing to the culturally rooted comprehension problems between different parts of the Anglophone world. Nel (2002), Pillière (2010) and Eastwood (2011), on the other hand, all reject INTRA in literature, arguing that dialectal or sociolectal features tend to be stylistically significant and that the modification of such features may jeopardize literary quality.

Within translation studies, INTRA encounters resistance, too, being treated as a phenomenon that is not fully worthy of scholarly attention by the discipline. The present article takes the exact opposite stance, aiming to contribute to the further integration of INTRA into the research field of TS, as initially called for by Zethsen (2009: 810), according to whom “[…] we need much more empirically-based research to provide a thorough and comprehensive description of intralingual translation and of the similarities and differences between intralingual and interlingual translation.” While comparisons of interlingual translations will not be among this article’s concerns, the aim will indeed be to contribute to a more “thorough and comprehensive description” (Zethsen 2009: 810) of INTRA than is presently available. One cardinal aspect of INTRA that has hitherto received virtually no attention is the diversity of the phenomenon and it is this diversity that will be explored here, both theoretically and empirically. Thus, INTRA can be seen to span a number of very heterogeneous sub-categories, already charted in a five-partite typology proposed by Gottlieb (2008). This article will therefore contribute to the theorizing of INTRA by reviewing Gottlieb’s typology. Empirically, the article will feature a comparative study of three out of five INTRA species, with the purpose of charting the differences as well as the similarities in how STs are transformed into intralingual TTs. The ST-to-TT transformation will be investigated along four different parameters initially identified in Hill-Madsen (2014):

Degree of transfer, that is the extent to which the semiotic content of the ST is represented in the TT. Not all ST content may be transferred.

Degree of derivation: Here the focus is the opposite, namely the extent to which the TT’s semiotic content originates in the ST. Parts of the TT may have no ST origin.

Degree of translation: This aspect is concerned with those parts of the TT that do originate in the ST. In those parts, the question is to what extent the ST-to-TT conversion is a result of linguistic changes, rather than simple reduplication of ST wordings.

The nature and range of the translation strategies deployed: The concept of strategy relevant for the present investigation consists of changes in lexis, grammar and spelling. This aspect, in other words, is a continuation of aspect no. 3, being concerned with those parts of the TT that have not only been derived from the ST, but have also been rewarded or have undergone changes in spelling. The question concerns the nature of these lexico-grammatical and orthographic changes.

The structure of the rest of the article will be as follows: Section 2 will outline the translation-theoretical underpinnings of the article, Section 3 will be devoted to a review of Gottlieb’s (2008) INTRA typology, and Section 4 will be concerned with three case studies, all of which are based on English-language data. An introduction to each case will be given in Section 4.

2. Theoretical underpinnings: INTRA as a translation category

Relying on Jakobson’s (1959: 233) famous tripartite translation typology (consisting of three species: intralingual, interlingual, and intersemiotic) as its theoretical point of departure, this article is premised on the recognition of INTRA as a translational category which must be accorded full membership in the overall concept of translation, completely in line with interlingual translation. Translation, in other words, must be regarded as a superordinate concept, with INTRA and interlingual translation as two parallel sub-categories (and intersemiotic translation as a third). However, not all TS scholars subscribe to this view, including Newmark (1991: 69), Mossop (1998: 252; 2016), Schubert (2005: 126), Eco (2003: 127-30) and Trivedi (2007: 285-86), who all oppose extending the boundaries of the translation concept beyond interlingual translation. Eco (2003: 127-30), in fact, goes so far as to ridicule the concept of intralingual translation, making a point of putting inverted commas around the word translation when using it to refer to other forms of semiotic conversion than translation in the ordinary sense (Eco 2003: 2). A similar practice (putting inverted commas around the word translation) is found in Nel (2002), who nevertheless wavers between inserting and omitting the inverted commas when referring to INTRA (between dialects of English - see Section 4.1). The inconsistency appears to reflect hesitations about treating INTRA as a truly translational category.

A number of other scholars, on the other hand, concur in widening the boundaries of the translation concept beyond its common-sense content, including Petrilli (2003a), Ponzio (2003), van Vaerenbergh (2003), Göpferich (2004, 2007), Tymoczko (2007), Zethsen (2007, 2009, 2018), Schmid (2008, 2012), Albachten (2013, 2014), Maaß, Rink, et al. (2014), Hill-Madsen (2015a), Karas (2016), and Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016). Of these authors, Zethsen (2007), Schmid (2008, 2012) and Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) offer extensive, theoretical arguments in favour of broadening the translation concept so as to include INTRA. Aiming to move beyond this debate, the present article is premised on this recognition of INTRA as a translational category, which is why only two cardinal points made by Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) will be briefly restated here. Firstly, in defining translation, Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) introduce the possibility of separating an academic conception of translation from a common-usage, or lay, understanding (according to which translation is interlingual only). To be more specific, an academic perspective may not only depart from lay or ‘folk’ notions, but may also cover a more well-defined and fine-grained taxonomy. Secondly, Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) argue that since translation centrally consists of the mediation of meaning across a (potential) comprehension gap, it is immediately apparent that these are traits that translation in the ordinary sense shares with numerous other possibilities of meaning transfer, from a ST to a TT, across semiotic barriers. Accordingly, building on Stecconi (2004, 2007), Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) hold that, in a definition of translation, the perspective should be expanded to mediated semiosis, irrespective of the particular type of semiotic resource deployed in the source and target, irrespective of any particular type of semiotic difference that constitutes the ST-TT divide. A semiotic barrier that necessitates translation may be a language-internal one, for exemple between two mutually unintelligible language varieties, as much as it may reside in the difference between two ‘national’ languages such as English and French, or in the difference between language as such and another sign system altogether. On the basis of this broad semiotic perspective, Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) reject the restricted, common-usage notion of translation, concluding that an academic concept of translation must be expanded far beyond this. As already mentioned, this conclusion is the present article’s theoretical point of departure, which means that the translational status of INTRA will not be further debated here but treated as a given.

3. A typology of INTRA

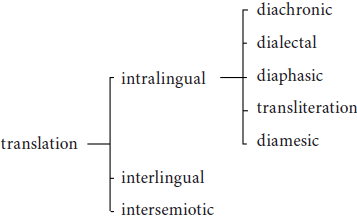

Following the previous section’s outline of the translation-theoretical foundations of the article, the present section proceeds to theorize INTRA through a review of a typology offered by Gottlieb (2008). The translational status of the individual categories of the typology will be discussed in the cases where this status may be questionable, and borderline cases will be identified and discussed where relevant. It should be noted that less comprehensive typologies have been proposed by Petrilli (2003b) and Gottlieb (2007), both of whose categories correspond to those found in Gottlieb (2008), but since the latter cogently argues for additional categories, it is the one adopted as a point of departure here[5]. Gottlieb (2008) identifies a total of five INTRA sub-categories: 1) diachronic; 2) dialectal (termed diglossic in Petrilli (2003b: 19); 3) paraphrasing (termed diaphasic in Petrilli 2003b: 19); 4) transliteration and 5) diamesic (same term in Petrilli 2003b: 19). Only the third category (paraphrasing/diaphasic) is not represented in Gottlieb (2007). The typology is to be seen as a continuation of Jakobson’s (1959: 233) primary, tripartite subdivision of the translation concept, taking the first level of the taxonomy to the next step in granularity. A graphical representation is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1

A graphic representation of Gottlieb’s (2008) INTRA typology

3.1. Diachronic INTRA

The diachronic category is concerned with translation between different historical varieties of the same language, typically in the form of modernized versions of pre-modern literary works (Gottlieb 2008: 56). Examples are the Old Testament translated into modern Hebrew (see Karas 2016), and the New Testament and ancient Greek classics translated into modern Greek (see Remediaki 2013; Seel 2015). In English, classics such as Chaucer and Shakespeare exist in modern-language versions (for an overview of Shakespeare modernizations, see Delabastita 2017).

3.2. Dialectal INTRA

The dialectal category (Gottlieb 2008: 57) represents translation between synchronic language varieties on a geographical dimension, which makes the category in itself a borderline case between inter- and intralingual translation (Toury 1986: 1113). The well-known linguistic concept of dialect continua, the phenomenon by which different dialects shade into separate languages (Heap 2006; Trudgill 2006), means that translation between closely related and mutually intelligible languages such as Polish, Czech and Slovakian or between Danish and Norwegian (Trudgill 2006) borders on INTRA. Conversely, translation between distant dialects such as the Cantonese and the Mandarin varieties of Chinese can be seen as bordering on interlingual translation.

3.3. Diaphasic INTRA (paraphrasing)

The category that Gottlieb (2008: 57) terms paraphrasing is one for which Petrilli’s alternative label diaphasic will be preferred here, in order to avoid confusion with the ordinary use of the term paraphrase within translation studies, namely as a reference to a specific type of micro-level translation strategy (for exemple Chesterman 1997: 104). Diaphasic INTRA refers to a simplification of linguistic register, exemplified in “[…] situations where public authorities wish to communicate more effectively with clients or voters by making syntactically complex and expert-sounding texts easier to read for the non-expert” (Gottlieb 2008: 57). It should be noted, however, that this ‘downward’ transformation from a highly specialized to a non-specialized register has its counterpart in a converse ‘upward’ movement, namely in cases where non-expert utterances are translated into the expert’s field-specific terminology (see also Hill-Madsen 2015a: 88). Examples would include lawyers drawing up legal documents such as wills on the basis of clients’ non-legal input or civil servants drafting new legislation from the directions of elected parliamentarians. An examination of such ‘layman-to-expert’ INTRA will have to be left out of the investigation, however, owing to the huge obstacles to be foreseen in obtaining authentic instances.

3.4. Transliteration

Transliteration (Gottlieb 2008: 57) is the one category that is not represented in either of the two other typologies referred to above (Gottlieb 2007; Petrilli 2003b). It may be defined as a “one-to-one conversion of the graphemes of one writing system into those of another writing system” (Coulmas 1999: 511), such as the rewriting of Greek words with Roman letters (for instance, a word like µεταφρασή transliterated into the Latin characters metaphrasè). This simplicity of translational procedure may possibly be considered prejudicial to the translational status of the category, since only changes in lettering occur while wordings are left intact. However, although a difference in wording may be a surface characteristic of much translation, especially interlingual translation, it cannot be recognized as a necessary condition of translationhood. As mentioned in Section 2, Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016) broaden the criterion into any kind of semiotic difference, which would logically include differences between systems of lettering. Hence, transliteration must be recognized as a member of the translation concept.

3.5. Diamesic INTRA

Diamesic INTRA (Gottlieb 2008: 56) refers to a change in channel, that is between speech and writing, and may be in either ‘direction.’ In the same way as the dialectal category was seen to constitute a borderline case between inter- and intralingual translation as such, diamesic INTRA may be seen as a borderline case between intralingual and intersemiotic translation, or even, as is Chuang’s (2006) view, as truly belonging in the intersemiotic category. Gottlieb (2008: 56), however, cogently refutes this approach, pointing out that diamesic INTRA is language-internal, in other words an intrasemiotic phenomenon, because “what is verbal in the source text remains verbal.”

The switch from the oral to the graphic channel is exemplified in intralingual subtitles for hearing-impaired TV-viewers (Gottlieb 2008: 57; see also de Linde and Kay 1999: 8-18; Nagel, Hinderer, et al. 2009: 45-46), of which a special instance is so-called subtitle re-speaking, which consists of the live production of subtitles during TV broadcasts (Lambourne 2006; see also Jekat 2014). As for the opposite diamesic ‘direction,’ that is writing to speech, an example is audiobooks (Gottlieb 2008: 57). Like intralingual transliteration, the translational status of diamesic INTRA may appear questionable, since the translational procedure ‘merely’ consists of replacing phonemes with graphemes (or vice-versa). Nevertheless, considering that the function of diamesic transformation is to provide a certain group of recipients with access to semiotic content from which they would otherwise be barred, and since a semiotic barrier (between phonemes and graphemes) is crossed in the process, the view taken here is that diamesic transformation must also be recognized as a type of translation.

3.6. A summary of revisions proposed

In conclusion to the above review, the modifications proposed ought to be highlighted, along with others that have yet to be brought to the fore. The modifications all consist of the addition of further taxonomic levels to Gottlieb’s typology. Firstly, the five species can actually be seen to fall into two distinct categories: Nos. 1-3 (dialectal, diachronic, and diaphasic) and 4-5 (transliteration and diamesic). The reason is that the first three species are all intervarietal, being all concerned with translation between different language varieties: geographical (the dialectal species), temporal (the diachronic category), and functional (diaphasic) (for the equation of registers with ‘functional varieties’ or ‘varieties according to use,’ see Halliday 1978: 31-32). As opposed to the first three categories, transliteration and diamesic INTRA are both intravarietal, since the particular language variety of the ST remains unaffected by the rewriting in these two cases. Secondly, a further taxonomic level can be identified in the intervarietal category, with the three species subdividing into two superordinate categories, diachronic (No. 1) and synchronic (Nos. 2 and 3, dialectal and diaphasic INTRA). Finally, an extension of the diaphasic category into two subtypes has already been proposed, that is to say an expert-to-lay vs. a lay-to-expert subspecies.

A full graphic representation of the revised typology, with modifications and extensions included, is as follows:

Figure 2

A fully developed graph of the revised Gottlieb (2008) INTRA typology

4. Empirical section: Case studies of diachronic, dialectal and diaphasic INTRA

The following section will be concerned with case studies[6] of three out of the five INTRA categories identified in Section 3: 1) a case of dialectal INTRA between the British and the American dialects of English, represented by the American versioning of the first Harry Potter novel (Section 4.1); 2) a case of diaphasic INTRA, where a specialized pharmaceutical text is rewritten into an information leaflet aimed at lay readers (Section 4.2); and 3) a case of diachronic INTRA, for which the modernization of an extract from Shakespeare’s Hamlet has been selected (Section 4.3). Transliteration and diamesic INTRA will be left out of the investigation, partly owing to spatial constraints, but also because both species must be taken to consist, at their core, of completely predictable translation strategies.

As briefly mentioned in the introductory section, translation strategies will be conceived of as shifts (see van Leuven-Zwart 1989, 1990; Bakker, Koster, et al. 2009), that is as changes in lexis and grammar. The analyses will primarily be based on Chesterman’s (1997) taxonomy of shift types, but in some cases Chesterman’s framework will be supplemented with categories from Newmark (1988), Vinay and Darbelnet (1958/1995), and Vermeer (2008) among others. Since, as the following analyses will show, only a comparatively few shift types altogether are pertinent for present purposes, only relevant categories will be defined, and not until they are needed in the analyses. It should be noted that, also for reasons of space, a few peripheral types of shifts have had to be ignored in the case studies. These primarily pertain to shifts in morphology in the diachronic case.

4.1. Dialectal INTRA: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

Outside subtitling, the versioning of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels for the American readership is probably the most prominent example of dialectal INTRA. The US versions contain a number of intralingual changes which were explicitly motivated – and defended against criticisms – by the American editor, Arthur Levine, as a deliberate measure to remove potential comprehension obstacles in the original British version for the young American readership (Nel 2002: 274). Here, the nature and extent of these intralingual changes will be investigated in the first novel in the series, published originally in the UK as Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Rowling 1997[7]), and in the US the following year under the title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (Rowling 1998[8]).

When the two versions are compared, it is immediately apparent – and fully to be expected – that the degree of transfer and the degree of derivation (defined in the introductory section) are both 100%, as evidenced in the following short extract:

As Example (1) illustrates, most of the American TT consists of reduplication of ST wordings, making the degree of translation very low, with only a very small number of changes between ST and TT being in evidence. Like the ones underlined in Example (1), most are lexical shifts, of which the following is a complete list of those found in the novel as a whole:[9]

Table 1

Lexical shifts between the British ST and the American TT

In terms of translation strategies, the items on the above list can largely be divided into instances of adaptation/cultural filtering on the one hand and literal translation on the other, with certain items appearing as borderline cases. Literal translation is defined by Newmark (1988: 46) as follows: “The SL grammatical constructions are converted to their nearest TL equivalents but the lexical words are again translated singly, out of context.” Thus literal translation applies to those TT items from the above list that must be deemed “the nearest [US English] equivalent” to the corresponding British English ST item. Examples are pairs like dustbins/trash cans, post/mail, holidaying/vacationing, sweets/candy, register/roll call, pitch/field, fortnight/two weeks. The same even applies to a number of the specific food and sports items, which might otherwise be expected to be culture-specific. Pairs like chips/fries, crisps/chips, lolly/pop, jacket potato/baked potato and football/soccer are all cases where the exact same cultural phenomenon is simply labelled differently in the two cultures, and where no change of cultural content (see further below) can be said to have taken place. It is noteworthy, for example, that reference to a source-culture phenomenon such as football has in fact been retained through replacement by the lexical item soccer, which is the American label for the European sport that plays only a marginal role in the US.

It needs to be considered, however, if the category synonymy, defined by Chesterman (1997: 102) as the selection of “not the ‘obvious’ equivalent but a synonym or near-synonym,” better captures the strategy involved in the instances categorized as literal translation above. After all, it was argued that the paired items in examples such as post/mail and holidaying/vacationing are completely synonymous. From the perspective of the English language as a whole, these items must indeed be regarded as dialectal synonyms, but from the perspective of the individual dialect the category of synonymy is only relevant if both items (ST and TT item) actually exist within the lexicon of that dialect. That, however, is not the case with (British English) items such as the noun post and the verb holiday, which do not exist in these specific senses in US English. In the American dialect, such elements are indeed ‘foreign’ elements, and hence the category literal translation is deemed to make the best analytical sense in these cases. A few cases of synonymy do occur, however, which are mad/crazy and timetable/schedule (when these two words are considered in isolation from their combination with revision and study, respectively). Mad and crazy both exist in US English in the sense of ‘insane,’ but the latter item has obviously been chosen in the TT in order to avoid confusion with the informal use of the word (‘very angry’). Timetable and schedule exist in the British dialect, but also in the American and are synonyms in both places.

In connection with certain other ST-TT pairs from the above list, the lexical replacement does entail a decided change in semantic content, with culture-specific British items being replaced by TT items that are specific to American culture. In these cases, the relevant translation-strategy would be Vinay and Darbelnet’s (1958/1995: 39) adaptation, used to solve the problem that occurs “where the type of situation being referred to by the SL language is unknown in the TL culture.” The corresponding category in Chesterman (1997: 108) is cultural filtering, which “describes the way in which SL items, particularly culture-specific items, are translated as TL cultural or functional equivalents, so that they conform to TL norms.” It might perhaps be expected that the ‘Americanization’ of the British source text would entail frequent instantiation of this strategy, but only relatively few instances can in fact be identified, such as rounders/baseball and crumpets/English muffins.Rounders and baseball refer to relatively similar, but nevertheless different types of sport, and crumpets and English muffins are not completely identical types of cake. Jelly/Jell-O and sellotape/Scotch tape are dubious cases, in that TT Jell-O is a registered American trademark and thus refers to a branded product, while jelly, being a common noun, does not. The same difference applies to sellotape/Scotch tape, the latter also being a registered trademark. Whether exactly the same cultural phenomenon is being referred to or not in each of these two pairs must be left an undecided question.

Apart from the lexical shifts, the only other changes are orthographic ones which reflect the familiar differences in British and American English spelling conventions, such as the British -ise ending converted into -ize, like in realise (Rowling 1997: 8; Rowling 1998: 2), the British -our converted into American -or, like in armour (Rowling 1997: 96; Rowling 1998: 129), and the British -mme in ST programme (Rowling 1997: 32) becoming TT program (Rowling 1997: 37). Other similar changes in spelling can be found, but will not receive any further attention here, since in terms of translation strategy they must all be assigned to the category of literal translation, just like some of the lexical changes analyzed above. This is because the orthographic changes in the TT represent not only the “nearest” but indeed the direct TL (or target dialect) equivalents at the level of graphology.

4.2. Diaphasic INTRA: Patient Information Leaflets

The case study selected for the investigation of diaphasic INTRA is the rewriting of specialized pharmaceutical product specifications (so-called Summary of Product Characteristics) as STs into information leaflets aimed at the end user of the medicinal product (official English title: Patient Information Leaflet) as TTs. The Patient Information Leaflets, which accompany the packaging of the product, set out the pharmaceutical details that are relevant to the patient: information concerning the ingredients of the drug, the type of medical condition for which the drug is used as a treatment, the proper way to administer it, cases where its use is not recommended, possible side effects, and storage instructions.

All the pharmaceutical information contained in the TTs originates in the specialized STs.[10] However, the information is rewritten in a (mostly) non-expert register, which reflects a legal requirement. According to official guidelines, “the package leaflet should be written in a language understandable by the patient and should reflect the terminology the patient is likely to be familiar with” (EMA 2016: 25). For the case study below, the Summary of Product Characteristics and the Patient Information Leaflet for the product Cholib (EMA 2019[11]), available on the website of the European Medicines Agency, have been chosen.

4.2.1. Degree of transfer, derivation and translation

Of the three INTRA categories investigated in this article, the diaphasic type turns out to be the one that exhibits the lowest degree of both derivation and transfer, as the following example bears out:

As Example (2) shows, only a few elements from the ST section, for instance in some patients, at high risk of future diabetes and should be monitored, have found their way into the TT as (your doctor) will monitor you and (you) are at risk of developing diabetes, respectively. Characteristically, the more technical elements from the ST, such as may produce a level of hyperglycaemia, the reduction in vascular risk with statins, and fasting glucose 5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L, BMI>30 kg/m2, raised triglycerides, hypertension have been omitted in the TT.

When it comes to the degree of derivation represented by the TT as a whole, a rough estimate is that only about half the text originates in the ST. Non-derivation, or addition (Chesterman 1997: 109), or the presence of TT elements with no ST origin, occurs, for exemple in repeated admonitions to consult a medical professional in cases of side effects, doubts about dosage and the like.

With regard to degree of translation, the TT also represents far from 100%, in that a certain proportion of the TT elements that do originate in the ST represent pure reduplication. This, too, is in evidence in Example (2) above, where the ST lexical items monitor, risk, and diabetes have all been preserved in the TT.

4.2.2. Translation strategies: Grammatical shifts

Four types of grammatical shifts have been identified, of which two must be assigned to Chesterman’s (1997: 96-97) umbrella category clause structure change. These are shifts in voice from passive to active and shifts in mood from the declarative to the imperative. The shift in voice was in fact present in Example (2), where the ST wording patients at risk… should be monitored… is rewritten as your doctor will monitor you. Since passive constructions tend to be associated with formal, ‘bureaucratic’ discourse (Charrow 1988), there is good reason to assume that shifts from the passive into the active are motivated by a wish to achieve a less formal register in the TT.

The shift in mood is exemplified in the following pair:

The ST clause is a declarative which has been turned into an imperative (Do not crush…) in the TT. A possible explanation for this shift is that the imperative is the most straightforward way to express a command or an instruction (Matthiessen 1995: 438-39), which is the pragmatic function of the TT segment. It may be noted that the shift in Example (3) combines with a change in voice from passive to active, and it may also be noted that these two grammatical changes are the only two shifts that affect the segment. Both not and the three lexical items crush, chew, and tablet are all reduplications of ST items.

The third type of grammatical shift identified is one for which there is no obvious category in Chesterman (1997), Newmark (1988) or Vinay or Darbelnet (1958/1995). It consists of a shift within the person system and has in fact already been illustrated in Example (2), where ST patients became TT you, that is a third to second person shift based on the replacement of a lexical item (patient) with a grammatical one (the pronoun you).

A fourth grammatical shift type in the text pair consists of the transformation of noun phrases into clausal structures, called unit shift by Catford (1965: 79) and Chesterman (1997: 95):

The TT clausal structure you being able to is derived from the ST noun phrase the ability to drive, which also involves what Vinay and Darbelnet (1958/1995: 36) term transposition, or a change of word class, from noun (ability) to adjective (able). In the specific cases as in the present where the TT structure is derived from a ST nominalization (ablility), I suggest the term de-nominalization. Since, according to Halliday (1989), nominalized constructions are a key feature of written language, de-nominalization may be interpreted as a means of achieving a more ‘spoken’ register in the TT (for an extensive analysis of this specific shift type in Hallidayan terms, see Hill-Madsen 2015b).

4.2.3. Lexical shifts

The type of lexical shift which must be deemed central for the purpose of registerial simplification is what is best captured by Piorno’s (2012: 181) term determinologization, which refers to the replacement of specialized medical and pharmaceutical terms with popular ones. An example is:

The TT item high levels of fats in the blood is a manifestation of, or is at least very close to, what Vermeer (2008: 7) terms morphematic translation, in that the original Greek morphemes of the medical term are recognizable in specific elements of the TT item: ST hyper- has become TT high levels of, triglycerid- has become fats, and -aem- has become blood. It should be noted that Example (5) also contains another lexical shift type that repeatedly occurs in the text pair, which is synonymy: ST due to has been replaced by caused by in the TT. Another example of synonymy was found in Example (4), where ST influence was changed into TT affect, with a concomitant change in word class (the ST item is a noun and the TT item a verb).

A shift type that is closely related to, yet slightly different from determinologization, is represented by cases where the ST origin is not a decidedly specialized term, but nevertheless a relatively formal/academic one that is replaced by a more colloquial item in the TT. This is seen in Example (6) below, where ST report can hardly be categorized as a technical term, but is nevertheless more formal than TT tell:

Finally, the shift type known as paraphrase is prevalent in the text pair. Chesterman’s definition is the following:

The paraphrase strategy results in a TT version that can be described as loose, free, sometimes even undertranslated. Semantic components at the lexeme level tend to be disregarded, in favour of the pragmatic sense of some higher unit such as a whole clause.

Chesterman 1997: 104

One example is:

The relation between ST recommended and TT usual is not explicable in terms of a semantic relation such as synonymy or hyponymy, and rather must be considered a “loose” or “free” rendition, where only a kind of logical or consequential relation appears to obtain between the two items: The dose of one tablet a day may be said to be usual because it is the recommended one.

To sum up the translation strategies in the diaphasic case as a whole, it turns out that the range of strategies is somewhat broader than in the dialectal case, spanning not only four lexical categories[12], three of which differed from the ones identified in the Harry Potter case, but also four different grammatical types.

4.3. Diachronic INTRA: The case of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

According to Delabastita (2017), modernizations of Shakespeare fall into two distinct categories, with some remaining loyal to the iambic pentameter of the original while others are translated into prose. In this investigation, a prose translation has been selected, since a prose version is more likely to bridge the comprehension gap between Shakespeare’s original readership and a one. For the present case study, an extract from the middle of Hamlet[13] was selected, that is the beginning of Act III, Scene 1 (lines 1-57). The modernized TT is taken from Sparknotes.[14]

4.3.1. Degree of transfer, derivation and translation

In respect to degree of transfer and derivation, it turns out that the diachronic INTRA of Hamlet is quite similar to the Harry Potter case, in that both transfer and derivation are close to 100%:

Virtually all ST content in Example (8) has been transferred to the TT, with the exception of the ST element To hear of it, for which there appears to be no corresponding TT element. A handful of similar elements in the ST extract as a whole have not been transferred, which means that the degree of transfer is actually not a full 100%. In the TT, it is debatable whether all elements can in fact be traced back to corresponding ST elements. With regard to degree of translation, the underlined elements in Example (8) are those which represent grammatical and lexical changes, illustrating that a considerable proportion of the TT is constituted by reduplication of ST items. The relatively small size of the sample selected here (namely the first 57 lines of Act III) has in fact made it possible to reach a rather precise calculation of the translation degree. The TT extract numbers 371 words in total (excluding the names indicating who speaks the lines), of which 239 words represent translation and 132 represent mere reduplication of ST words. This makes the degree of translation in the sample 64.4%, or about two thirds. What Example (8) also illustrates is the nature of the non-translated elements, which primarily include grammatical items such as pronouns (We, him, They, I), articles (the), conjunctions (and) and prepositions (on), whereas most of the lexical items have been translated. Exceptions are relatively simple lexical items such as way, told, seem, and night.

4.3.2. Translation strategies: Grammatical shifts

Only relatively few instances of grammatical shifts have been uncovered in the sample, with the majority belonging to one single category, which is the one previously termed de-nominalization:

The ST nominalization Your loneliness has been converted into the TT clause you’re all alone, where the ST possessive pronoun Your now features as the subject pronoun you in the TT and the adjectival root of ST loneliness has become subject complement in the TT.

The only other grammatical strategies that can be identified are two cases that belong in Chesterman’s (1997: 96-97) category clause structure change. These shifts were both seen in Example (8), where the subordinate clause (that certain…) of ST Madam, it so fell out, that certain players / We o’erraught on the way has been rearranged so that what is the direct object in the ST (certain players) is made to serve as the subject in the corresponding TT clause some actors happened to cross our paths on the way here. In the next sentence in Example (8) (original Shakespeare, line 17), Of these we told him, a change of constituent order has taken place so that the complement that occupies thematic position in the ST (Of these) has been moved to the end position in the TT (We told him about these).

4.3.3. Translation strategies: Lexical shifts

Among the lexical shifts, literal translation is also represented in the present case study, as in Example (10) below:

According to the Oxford English Dictionary[15], one of the senses of assay is, or rather was, indeed ‘tempt.’ Since the ST item is now obsolete in English, and since tempt must thus be considered “the nearest TL equivalent” (Newmark 1988: 46, which we quote yet again) the shift is a case of literal translation between the two diachronic varieties. Other unequivocal instances are ST hither (line 30) translated into TT here and ST affront into run into in Example (11) below:

Hither as well as affront in the specific senses used here are both obsolete and have both been replaced by modern-English equivalents in the TT.

While literal translation is a strategy which the present case has in common with the Harry Potter case, it is interesting to note that certain lexical strategies found in the diachronic case also overlap with those uncovered in the diaphasic case. Thus, synonymy is a frequent strategy:

Both TT admits and say must be regarded as synonyms of ST confess and speak, respectively. Another strategy observable in Example (12) is one which has not been found in either of the two other case studies: compression, defined by Chesterman (1997: 104) as “the distribution of the ‘same’ semantic components over […] fewer items.” In Example (12), this is in evidence in ST will by no means becoming TT refuses and ST from what cause becoming TT why. This is a relatively frequent strategy which explains why the TT segments are often somewhat shorter than the corresponding ST segments.

Two other strategies manifested in the extract are paraphrase and explicitation, the latter being definable as “the technique of making explicit in the TT information that is implicit in the ST” (Klaudy 2008: 104; for similar definitions, see Chesterman 1997: 108-9 and Vinay and Darbelnet 1958/1995: 342). Both categories occur in Example (13) below:

TT this happens all the time is a paraphrase, a free rendering, of the ST unit ‘Tis too much proved, in that there is no synonymy between individual lexical items. The instance of explicitation occurs in the TT unit to God, which must be considered implicit in ST devotion, possibly together with pious action. What Example (13) also instances is a strategy that falls under Chesterman’s (1997: 105-6) category trope change, which is an umbrella term for a number of more specific ways of translating metaphors. Here the term de-metaphorization is preferred as a reference to the particular strategy in evidence in Example (13), where the metaphorical ST expression The devil himself is rendered non-metaphorically as TT bad deeds. To the extent that TT mask may be said to have lost its metaphoricity, the item similarly represents de-metaphorization, namely of ST sugar o’er.

5. Conclusion

This article has aimed to contribute to the description of intralingual translation, partly through typologization of the phenomenon and partly through a comparative investigation of three subtypes. In the theoretical discussion, Gottlieb’s (2008) taxonomy was reviewed and modified through the addition of further taxonomic levels. Empirically, the article has charted the heterogeneity in the transformation of STs into intralingual TTs along four parameters, and while considerable diversity was indeed found in all four aspects, certain points of similarity were also identified. Thus, in respect of degree of translation, what emerges as a central characteristic of all three types of INTRA investigated is the fact that they are partial translations only, in that the derivation of TT content from ST content was found to be only partially a result of changes across the ST-TT divide. As a logical result, reduplication of ST items in the TT was seen to be a prominent feature of all three species, though to markedly different extent. In two other respects, namely degree of transfer and degree of derivation, the diaphasic case was seen to differ from both the dialectal and the diachronic case because only a minor part of the ST content was found to be represented in the TT and because certain TT content was seen to be without origin in the ST. With regard to translation strategies, the investigation also uncovered considerable diversity, since in each case study one or several lexical shift types were identified that proved unique to that particular case: cultural filtering/adaptation in the dialectal case, de-terminologization in the diaphasic case, and de-metaphorization, compression, and explicitation in the diachronic case. Moreover, the three cases differed significantly when it came to grammatical strategies, with the diaphasic case being the only one where grammatical shifts were prominent, whereas the shifts identified in the two other cases were either predominantly or even exclusively lexical. On the other hand, some overlap in translation strategies was also registered. Synonymy was observed in all three cases studies, and literal translation was seen to apply to two (dialectal and diachronic), as did paraphrase (diaphasic and diachronic).

Despite these overlaps, the final conclusion is that when the three cases are compared from an overall perspective, it turns out that the diachronic and the diaphasic cases have more in common with each other than with the dialectal case, and that the Harry Potter case is ‘the odd man out’ in the comparison. The Shakespeare case and the diaphasic case both exhibited a relatively large variety of translation strategies, which the Harry Potter case did not. Similarly, the two cases (diachronic and diaphasic) both exhibited a relatively high degree of translation, unlike the Harry Potter case where the translation degree proved extremely low – so low, in fact, that the American version as a whole barely qualifies as a case of translation. Presumably, the explanation for these differences is to be found in the proximity/distance between the intralingual varieties involved in each case. There is a marked distance between Shakespearean and modern English (the diachronic case) and possibly an even greater distance between the specialized register of the pharmaceutical texts and the general-language register of the Patient Information Leaflets (the diaphasic case). The differences between the two English dialects investigated in the Harry Potter case, on the other hand, are in fact very few. This appears to explain the high degree of mere reduplication from ST to TT and the very limited range of translation strategies in the dialectal case. A more elaborate attempt to explain the differences observable between the invidual types of INTRA, however, must remain the subject of a future study.

Coda

During the review process of this article, a number of interesting theoretical points were debated that are highly pertinent to the ongoing debate within TS about the very definition of the translation concept and about the status of INTRA within TS. As a coda to the article, the four most salient points in the debate, along with the clarifications that the debate gave rise to, are reproduced here.

A first point concerned the article’s dismissal (in Section 2) of ‘folk’ conceptualizations of translation. A clarification of the article’s standpoint is that ‘folk’ notions regarding translation, while far from meaningless and to be simply ignored, may be unacceptably narrow by disregarding translational phenomena that should be theoretically recognized as such (for instance INTRA). Thus, a scholarly conceptualization may well be able to adopt certain elements of a lay perspective that are found to be theoretically valid, whereas the reverse is much less likely to be the case.

A second point of contention sprang from the fact that, in the article’s discussion of Gottlieb’s (2008) INTRA typology, all subcategories are accorded equal and full membership in the superordinate translation concept, rather than gradient membership, which would have been the consequence if a prototype/family-resemblances approach had been adopted. The reason why a prototype/gradient/scalar concept (in the case of INTRA) was not taken into consideration is that such a concept is an unclear one with an underspecified content. If gradient membership was assigned to the members of the INTRA category, then what exactly, it must be asked, are the characteristics that the five subcategories purportedly exhibit to such varying degrees? If, for example, the switch between two divergent lexico-grammatical systems is to be seen as one such key characteristic, then it must be asked why such a characteristic should be ascribed centrality. A conceivable answer is that it is a feature which unites virtually all interlingual translation, and that interlingual translation represents the prototypical case of translation, but this only begs the question why interlingual translation is the prototypical case. If the answer is that interlingual translation involves a switch between two different lexicogrammatical systems (for exemple, the grammar-lexis of English vs. that of French), then the argument is circular. And if the answer is that interlingual translation is what is prototypically meant by the word ‘translation’ in ordinary parlance, it is a definition which has brought us back to the lay notions on which that no scientific discipline can and should be based. What the above deliberations show is that unequivocal, scholarly argued definitions are unavoidable in any scientific pursuit (see also Robinson 2011: 69-70), which is exactly why in Korning Zethsen and Hill-Madsen (2016: 704-5) we concluded by formulating a criterial definition of the translation concept which specifed clear criteria for membership, and on which a scientific taxonomy of translation could be built. Membership under such terms is absolute and not gradable, which, however, does not mean that membership is equally obvious in all cases. Nevertheless, the point is that in each case the question can be settled with reference to the specified criteria for membership. In the present article, such consideration of membership is undertaken with both the diamesic category and with transliteration (Sections 3.4 and 3.5), since both categories admittedly represent some of the less obvious types of translation in the INTRA typology.

A third point of debate was whether, by extending the translation concept to INTRA, the article risks ‘diluting’ the concept to such a degree that any kind of rewriting or metatextuality must be recognized as translation. This danger, however, is precluded by the very fact that the article’s definition of the translation concept is a criterial one. The two criteria are: the neutralization of a comprehension obstacle and the presence of a semiotic border between ST and TT, or a border between two different meaning-making systems. This means that intralingual rewriting as such, for instance a summary of a longer text in the same language, would not in itself qualify as translation, whereas the presence of a semiotic border such as that between two different registers would. Thus, summaries of specialized texts for lay readers may be regarded as intralingual translations. Obviously, in the same way as the semiotic-border criterion was applied to certain INTRA species (transliteration and diamesic INTRA), the criterion must be rigorously applied to borderline cases within the individual subcategories. As a case in point where the ST-TT difference appears to be so negligible as to render the INTRA concept absurd is the borderline example of transliteration where a typeface is simply enlarged to facilitate reading and comprehension for elderly people. Measured against the two criteria, however, this example would not qualify as INTRA. Though such a transformation may indeed facilitate comprehension, no semiotic border is crossed between ST and TT in this case, since enlarging a typeface is simply a matter of ‘turning up the volume’ of the channel and corresponds to raising one’s voice in spoken interaction. Another borderline case of transliteration that must be discounted is the conversion of the Gothic script into ‘ordinary’ Latin characters (or vice-versa): Since the Gothic script does not in effect constitute an independent alphabet, but simply a different font and thus not a different meaning-making system, the example must be excluded from the translation category. The difference, for example, between the Greek and the Roman alphabets, on the other hand, is one between two different meaning-making systems (α, β, γ, δ, etc. vs. a, b, c, d, etc.) and so is the diamesic difference between a phonemic system (/ɔ/, /ʌ/, /ə/, /ŋ/, etc.) and a system of graphemes (o, u, e, -ng-, etc.).

A final point worth clarifying pertains to the status of shifts in translation. It is important to emphasize that the presence of shifts in the three case studies is in no way to be read as ‘proof’ of translationhood. The article in no way aims to deduce translationhood from the occurrence of (certain) shifts and the empirical analyses thus do not serve as the ‘building blocks’ of any larger theoretical argument. The reverse, rather, is the case. Since the three empirical cases can theoretically be argued to be instances of translation, the implicit assumption is that the analytical tools of translation studies (in this case shift analysis) can be fruitfully applied in the empirical investigation of them. The analyses of shifts in the three case studies are thus to be seen as empirical research in their own right, aimed at uncovering (part of) the nature of the three INTRA subtypes in question.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Plain Language Action and Information Network (Last update: 30 March 2019): Why use plain language? plainlanguage.gov. Consulted on 1. May 2019, <https://www.plainlanguage.gov/about/benefits/>.

-

[2]

Court of Justice of the European Union (1996-): Press releases. CURIA. Consulted on 19 September 2018, <https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/Jo2_7052/en/>.

-

[3]

European Medicines Agency (Last update: 3. July 2019): European public assessment reports: background and context. European Union. Consulted on 1 May 2019, <https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/what-we-publish-when/european-public-assessment-reports-background-context>.

-

[4]

Libak, Anna (11 January 2013): Forstyr Gravfreden! [Desecrate the graves!]. Weekendavisen. 4.

-

[5]

See also Gottlieb (2018) for a very recent version of the typology. For a non-typological description of INTRA, see Zethsen (2009).

-

[6]

We have so far been using italics to highlight terms and concepts. To better distinguish the ST and TT, we will be using the following typography: ST examples and TT examples.

-

[7]

Rowling, Joanne K. (1997): Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. London: Bloomsbury.

-

[8]

Rowling, Joanne K. (1998): Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. New York: Scholastic Inc.

-

[9]

The list is a result of a careful scrutiny of both versions in their entirety

-

[10]

For a charting of the derivation of TT sections from corresponding ST sections, see van Vaerenbergh (2007: 172) and European Medicines Agency (Last update: 28 July 2019): QRD product-information annotated template (English). Version 10.1. European Union. 25-39. Consulted 10 August 2019, <https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/template-form/qrd-product-information-annotated-template-english-version-101_en.pdf>.

-

[11]

Both ST and TT are contained in the document. European Medicines Agency (Last update: 12 March 2019): Cholib: EPAR - Product Information. European Union. Consulted on 11 April 2019, <https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/cholib-epar-product-information_en.pdf>.

-

[12]

For a lexical analysis of diaphasic INTRA by means of concepts from Systemic-Functional Linguistics not covered in the present article, see Hill-Madsen (2015a).

-

[13]

Shakespeare, William (~1602/2002): Hamlet. (Edited by Roma Gill) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

[14]

Shakespeare, William (~1602/2006): Act III, Scene 1. In: William Shakespeare. Hamlet. Sparknotes. Consulted on 29 October 2017, <http://nfs.sparknotes.com/hamlet/page_134.html>.

-

[15]

Oxford English DictionaryOnline (2019): Assay, v. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Consulted on 19 November 2018, <https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/11757?rskey=3mqqwf&result=2&isAdvanced=false>.

Bibliography

- Albachten, Özlem Berk (2013): Intralingual Translation as ‘Modernization’ of the Language: The Turkish Case. Perspectives. 21(2):257-271.

- Albachten, Özlem Berk (2014): Intralingual Translation: Discussions within Translation Studies and the Case of Turkey. In: Sandra Bermann and Catherine Porter, eds. A Companion to Translation Studies. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 571-585.

- Bakker, Matthijs, Koster, Cees, and Van Leuven-Szwart, Kitty (2009): Shifts of translation. In: Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha, eds. Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 269-274.

- Catford, John Cunnison (1965): A Linguistic Theory of Translation: An Essay in Applied Linguistics. London: Oxford University Press.

- Charrow, Veda (1988): Readability vs. Comprehensibility: A Case Study in Improving a Real Document. In: Alice Davison and Georgia M. Green, eds. Linguistic Complexity and Text Comprehension: Readability Issues Reconsidered. Hillsdale/London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 85-114.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1997): Memes of Translation: The Spread of Ideas in Translation Theory. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Chuang, Ying-Ting (2006): Studying Subtitle Translation from a Multi-Modal Approach. Babel 52(4):372-383.

- Coulmas, Florian (1999): The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Crystal, David (2002): To Modernize Or Not to Modernize – there is no Question. Around the Globe. 21:15-17.

- De Linde, Zoë and Kay, Neil (1999): The Semiotics of Subtitling. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Dean, Paul (2016): Insubstantial Pageants. New Criterion. 34(10):13-16.

- Delabastita, Dirk (2017): ‘He Shall Signify from Time to Time.’ Romeo and Juliet in Modern English. Perspectives. 25(2):189-25.

- Denton, John (2007): “…Waterlogged Somewhere in Mid-Atlantic.” Why American Readers Need Intralingual Translation but Don’t often Get It. TTR. 20(2):243-270.

- Eastwood, Alexander (2011): A Fantastic Failure: Displaced Nationalism and the Intralingual Translation of Harry Potter. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada/Cahiers de la Société bibliographique du Canada. 49(2):167-188.

- Eco, Umberto (2003): Mouse Or Rat?: Translation as Negotiation. London: Orion books.

- Göpferich, Susanne (2004): Wie man aus Eiern Marmelade macht: Von der Translationswissenschaft zur Transferwissenschaft [How to make marmelade from eggs: from translation studies to transfer studies]. In: Susanne Göpferich and Jan Engberg, eds. Qualität fachsprachlicher Kommunikation [Quality in LSP communication]. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 3-30.

- Göpferich, Susanne (2007): Translation Studies and Transfer Studies. In: Yves Gambier, Miriam Shlesinger, and Radegundis Stolze, eds. Doubts and Directions in Translation Studies: Selected Contributions from the EST Congress, Lisbon 2004. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 27-39.

- Gottlieb, Henrik (2007): Multidimensional Translation: Semantics Turned Semiotics. In: Sandra Nauert and Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast, eds. Challenges of Multidimensional Translation: Proceedings of the Marie Curie Euroconferences MuTra. (MuTra: Challenges of Multidimensional Translation, Saarbrücken, 2-6 May 2005). Consulted on 15 April, 2017, http://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2005_Proceedings/2005_Gottlieb_Henrik.pdf.

- Gottlieb, Henrik (2008): Multidimensional Translation. In: Anne Schjoldager, ed. Understanding Translation. Aarhus: Academica, 39-65.

- Gottlieb, Henrik (2018): Semiotics and Translation. In: Kirsten Malmkjaer, ed. The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies and Linguistics. Abingdon: Routledge, 45-63.

- Halliday, Michael A. K. (1978): Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, Michael A. K. (1989): Spoken and Written Language. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heap, David (2006): Dialect Chains. In: Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 528-530.

- Hill-Madsen, Aage (2014): Derivation and Transformation: Strategies in Lay-oriented Intralingual Translation. PhD thesis, unpublished. Aarhus: Aarhus University.

- Hill-Madsen, Aage (2015a): Lexical Strategies in Intralingual Translation between Registers. HERMES. 54:85-105.

- Hill-Madsen, Aage (2015b): The ‘unpacking’ of grammatical metaphor as an intralingual translation strategy: From de-metaphorization to clausal paraphrase. In: Karin Maksymski, Silke Gutermuth, and Silvia Hansen-Schirra, eds. Translation and Comprehensibility. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 195-226.

- Jakobson, Roman (1959): On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In: Reuben A. Brower, ed. On Translation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 232-239.

- Jekat, Susanne Johanna (2014): Respeaking: Syntaktische Aspekte des Transfers [Respeaking: syntactic aspects of transfer]. In: Susanne J. Jekat, Heike Elisabeth Jüngst, Klaus Schubert,et al., eds. Sprache barrierefrei gestalten: Perspektive aus der angewandten Lingvistik [Language without barriers: perspectives from applied linguistics]. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 87-108.

- Karas, Hilla (2016): Intralingual Intertemporal Translation as a Relevant Category in Translation Studies. Target. 28(3):445-466.

- Klaudy, Kinga (2008): Explicitation. In: Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha, eds. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, 2nd ed. Routledge: Abingdon, 104-108.

- Korning Zethsen, Karen and Hill-Madsen, Aage (2016): Intralingual Translation and Its Place Within Translation Studies - A Theoretical Discussion. Meta. 61(3):692-708.

- Lambourne, Andrew (2006): Subtitle Respeaking: A New Skill for a New Age. InTRAlinea. 8. Consulted 8 February 2018, http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/Subtitle_respeaking.

- Maass, Christiane, Rink, Isabel, and Zehrer, Christiane (2014): Leichte Sprache in der Sprache- und Übersetzungswissenschaft [Easily understandable language in linguistics and translation studies]. In: Susanne J. Jekat, Heike Elisabeth Jüngst, Klaus Schubert,et al., eds. Sprache barrierefrei gestalten: Perspektive aus der angewandten Lingvistik [Language without barriers: perspectives from applied linguistics]. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 53-86.

- Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M. (1995): Lexicogrammatical Cartography: English systems. Tokyo: International Language Sciences.

- Mossop, Brian (1998): What is a Translating Translator Doing? Target. 10(2):231-266.

- Mossop, Brian (2016): ’Intralingual Translation’: A Desirable Concept? Across Languages and Cultures. 17(1):1-24.

- Nagel, Silke, Henkel Susanne, Hinderer Katharina, et al. (2009): Audiovisuelle Übersetzung [Audiovisual translation]. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Nel, Philip (2002): You Say ‘Jelly,’ I Say ‘Jell-O’? Harry Potter and the Transfiguration of Language. In: Lana A. Whited, ed. The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 261-301.

- Newmark, Peter (1988): A Textbook of Translation. Hertfordshire: Prentice-Hall.

- Newmark, Peter (1991): About Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Petrilli, Susan (2003a): The Intersemiotic Character of Translation. In: Susan Petrilli, ed. Translation Translation. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 41-51.

- Petrilli, Susan (2003b): Translation and Semiosis. Introduction. In: Susan Petrilli, ed. Translation Translation. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 17-37.

- Pillière, Linda (2010): Conflicting Voices: An Analysis of Intralingual Translation from British English to American English. E-Rea. 8(1):1-10.

- Piorno, Pilar E. (2012): An example of genre shift in the medicinal product information genre system. Linguistica Antverpiensia New Series - Themes in Translation Studies. 11:173-186.

- Ponzio, Augusto (2003): Preface. In: Susan Petrilli, ed. Translation Translation. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 13-16.

- Remediaki, Ionna (2013): Intralingual Translation into Modern Greek. In: Georgios K. Giannakis, ed. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistices. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill, 256-260.

- Robinson, Richard (2011): Definition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schubert, Klaus (2005): Translation studies: Broaden or deepen the perspective? In: Helle V. Dam, Jan Engberg, and Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast, eds. Knowledge Systems and Translation. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 125-146.

- Schmid, Benjamin (2008): A duck in rabbit’s clothing: Integrating intralingual translation. In: Michelle Kaiser-Cooke, ed. Das Entenprinzip: Translation aus neuen Perspektiven [The duck principle: translation from new perspectives]. Bern: Peter Lang, 19-80.

- Schmid, Benjamin (2012): A bucket or a searchlight approach to defining translation? Fringe phenomena and their implications for the object of study. In: Isis Herrero and Todd Klaiman, eds. Versatility in Translation Studies: Selected Papers of the CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2011. (CETRA Summer School 2011, Leuven, 22 August to 2 September 2011). Consulted on 18 April 2017, https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/files/schmid.pdf.

- Seel, Olaf-Immanuel (2015): The Pragmatic-Functional Nature of Intralingual Translation and its Affinity to Top-Down-Procedures. Parallèles. 27(2):71-82.

- Stecconi, Ubaldo (2004): Interpretive Semiotics and Translation Theory: The Semiotic Conditions to Translation. Semiotica. 150(1):471-489.

- Stecconi, Ubaldo (2007): Five Reasons Why Semiotics is Good for Translation Studies. In: Yves Gambier, Miriam Shlesinger, and Radegundis Stolze, eds. Doubts and Directions in Translation Studies: Selected Contributions from the EST Congress, Lisbon 2004. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 15-26.

- Toury, Gideon (1986): Translation: A Cultural-Semiotic Perspective. In: Thomas A. Sebeok, ed. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics. Vol. 2. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1111-1124.

- Trivedi, Harish (2007): Translating Culture Vs. Cultural Translation. In: Paul St-Pierre and Prafulla C. Kar, eds. In Translation: Reflections, Refractions, Transformations. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 277-287.

- Trudgill, Peter (2006): Language and Dialect: Linguistic Varieties. In: Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 647.

- Tymoczko, Maria (2007): Enlarging Translation, Empowering Translators. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Van Leuven-Zwart, Kitty (1989): Translation and Original: Similarities and Dissimilarities, I. Target. 1(2):151-182.

- Van Leuven-Zwart, Kitty (1990): Translation and Original: Similarities and Dissimilarities, II. Target. 2(1):69-96.

- Van Vaerenbergh, Leona (2003): Fachinformation and Packungsbeilage: Fachübersetzung oder Mehrsprachiges Inter- und Intrakulturelles Technical Writing? [Technical information and package inserts: technical translation or multilingual inter- and intracultural technical writing?] In: Klaus Schubert, ed. Übersetzen und Dolmetschen: Modelle, Methoden, Technologie [Translation and interpreting: models, methods, technology]. Tübingen: Günter Narr Verlag, 207-224.

- Van Vaerenbergh, Leona (2007): Wissensvermittlung und Anweisungen im Beipackzettel. Zu Verständlichkeit und Textqualität in der Experten-Nichtexperten-Kommunikation [Knowledge transfer and instructions in package inserts. On comprehensibility and quality in communication between experts and non-experts]. In: Claudia Villiger and Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast, eds. Kommunikation in Bewegung: Multimedialer und multilingualer Wissenstransfer in der Experten-Laien-Kommunikation [Communication in motion: Multimedia and multilingual knowledge transfer in expert-lay communication]. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 167-185.

- Vermeer, Hans J. (2008): Translation today: Old and new problems. In: Anthony Pym, Miriam Shlesinger, and Daniel Simeoni, eds. Beyond Descriptive Translation Studies: Investigations in Homage to Gideon Toury. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 3-16.

- Vinay, Jean-Paul and Darbelnet, Jean (1958/1995): Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A Methodology for Translation. (Translated from French by Marie-Josée Hamel and Juan C. Sager) Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Zethsen, Karen Korning (2007): Beyond Translation Proper – Extending the Field of Translation Studies. TTR. 20(1):281-308.

- Zethsen, Karen Korning (2009): Intralingual Translation: An Attempt at Description. Meta. 54(4):795-812.

- Zethsen, Karen Korning (2018): Access is not the same as understanding. Why intralingual translation is crucial in a world of information overload. Across Languages and Cultures. 19(1):79-98.

List of figures

Figure 1

A graphic representation of Gottlieb’s (2008) INTRA typology

Figure 2

A fully developed graph of the revised Gottlieb (2008) INTRA typology

List of tables

Table 1

Lexical shifts between the British ST and the American TT

10.7202/038904ar

10.7202/038904ar