Abstracts

Abstract

The limitations of current terminology tools for specialized translators may, to a large extent, be explained by the complexity of the search process involved in producing good quality translations in specialist domains. This paper introduces a new approach to the development of this kind of resources aimed at satisfying the specific needs of specialized translators. This change of paradigm is reflected in the development of a prototype tool designed for use in legal translation. The tool – for use in English-Spanish translations of technological law in the localization of End User License Agreements – incorporates a revised corpus, comparative law information, and a terminological database. The features and advantages of the terminological database proposed are described in detail. Focusing on the specific needs of translators of this type of texts, comments are included on the acceptability of different terminological options on the basis of comparative legal analysis in different translation scenarios. The incorporation of these comments is a distinctive feature of this new approach to the development of resources and provides a value-added service to translators. The prototype tool designed is intended to serve as a model for the future development of similar applications in any type of specialized translation, in any given field and language combination.

Keywords:

- equivalent search in specialized translation,

- translation-oriented terminological entries,

- translation decision making,

- end-user license agreements

Résumé

Les limites des ressources actuelles quant aux outils de documentation pour les traducteurs spécialisés peuvent s’expliquer dans une large mesure par la complexité du processus de documentation quand il s’agit de produire de bonnes traductions. Cet article présente une nouvelle approche concernant les ressources de documentation pour répondre aux besoins spécifiques des traducteurs spécialisés. Cette nouvelle approche transparaît dans la conception d’un prototype d’outil pour la traduction juridique. Cet outil, conçu pour une utilisation dans les traductions anglais-espagnol de droit technologique pour la localisation de contrats de licence utilisateur final (CLUF), intègre un corpus révisé, des informations comparatives sur les différents systèmes juridiques, une base de données terminologique, ainsi qu’une description détaillée des caractéristiques et des avantages de la base de données terminologiques proposée. D’autre part, l’outil tient compte des besoins spécifiques des traducteurs de ce type de textes, des commentaires sur l’acceptabilité des différentes options terminologiques à partir de l’analyse juridique comparative dans différents scénarios de traduction. Ainsi, ces commentaires – une particularité de cette nouvelle approche – fournissent aux traducteurs un service à valeur ajoutée. Cet outil prototype est destiné à servir de modèle pour la mise au point future d’applications similaires, quel que soit le type de traduction spécialisée, le domaine ou la langue.

Mots-clés :

- documentation en traduction spécialisée,

- entrées terminologiques pour la traduction,

- prise de décisions en traduction,

- contrat de licence utilisateur final

Resumen

Es posible que las limitaciones de los recursos terminológicos disponibles para los traductores especializados en la actualidad se deban en gran medida a la complejidad del proceso de documentación que implica llevar a cabo una traducción de buena calidad en un ámbito de especialidad. Este artículo presenta un nuevo enfoque para el desarrollo de este tipo de recursos, dirigido a satisfacer las demandas de los traductores especializados. El cambio de paradigma se refleja en el diseño de un prototipo de herramienta orientada a la traducción jurídica, en concreto al ámbito del derecho tecnológico y al subcampo de la “localización” o traducción de licencias de uso del inglés al español. El prototipo incluye un corpus revisado, información de derecho comparado, una base de datos terminológicos cuyas características y ventajas se describen en detalle, así como comentarios para cada entrada sobre la aceptabilidad de diferentes opciones de traducción de los términos, en base a un análisis jurídico comparativo que tiene en cuenta los diferentes contextos de traducción posibles, dado que la herramienta está pensada para satisfacer las necesidades de los traductores de este tipo de textos. Estos comentarios constituyen uno de los rasgos destacables del nuevo enfoque para la creación de recursos, ya que ofrecen un importante valor añadido al traductor. El prototipo que se presenta pretende servir como modelo y base para el futuro desarrollo de bases de datos o aplicaciones similares en cualquier ámbito de la traducción especializada y para cualquier combinación lingüística.

Palabras clave:

- documentación en traducción especializada,

- fichas traductológicas,

- toma de decisiones en traducción,

- licencias de uso

Article body

1. The need for a comprehensive tool for specialized translators

Many authors have written about the search for equivalents in translation, the steps involved, and the complexity of the process in specialized translation.[1] The different types of information required for the purposes of translation – monolingual definitions, lexical equivalents, collocations, conventions and metadata in texts of a given field, thematic or domain-specific information, parallel texts, etc. – and the many sources that translators must consult to obtain this information makes the ideal search process a time-consuming task. Calvo and Calvi (2014) have analyzed many of the studies conducted on the types of tools currently used by specialized translators and have produced a list of six types of dictionaries and six other tools – including terminological databases, corpora and search engines – that are usually consulted by specialized translators. They conclude that “given the myriad of resources, it could be asked if one can talk about a translation dictionary and if any of those works can be considered as such” (Calvo and Calvi 2014: 48). Here, the authors are referring to the ‘ideal’ dictionary or tool that a translator would like to have, i.e., a resource ‘built’ for the translator covering all the needs.

Besides dictionaries and term banks, current technological advances and the Internet now provide us with ready access to much more information than has hitherto been available.[2] However, most of this information is neither well organized (Abadal 2004) nor revised or evaluated either by language experts or experts in the field to which the information pertains. Thus, both conceptual and linguistic errors in translation may go undetected by the translator. Bestué (2016) draws attention to the free-access Internet resources most frequently consulted by both expert and novice translators, such as multilingual digital corpus (Webitext,[3] Glosbe[4]), bilingual text alignment tools (Linguee,[5] 2lingual[6]), bilingual dictionaries that also offer aligned corpora (as Reverso dictionary[7]) and states that “consulting these sources may compel translators to simply select terms and phrases that, having been translated previously, may be considered as validated.” However, as she points out,

Search engines provide ready-made, statistically-validated solutions for translation problems. These, however, do not necessarily guarantee the quality of the translation product. Indeed, it has become increasingly difficult for both expert and novice translators to justify not following the ‘google rule,’ i.e. adopting the most commonly-used translation, when making their translation decisions (…) It is true that translators remain in charge of their own translation decisions, but it is not less true that the viral spread and lightning-fast uptake of equivalents can lead them to discard other translation procedures or equivalents that they fear will have less communicative impact on target readers, who are bound to be users of search engines.

Bestué 2016

The complexity of the search process holds true not only in traditionally complex domains such as legal translation, but also in all specialized fields.[8]

Although many new dictionaries and term banks have appeared recently and those already in existence have in some cases been subject to important changes, they still tend to disappoint specialized translators who hope to find all the information they require in lexicographical or terminographical resources. Many authors have drawn attention to the shortcomings of existing term banks[9] and bilingual specialized dictionaries, both on paper[10] and online.[11] In fact, Tarp (2014), after studying online dictionaries, concludes that many of them are identical copies of the paper dictionaries and many of the new ones that have been created originally in digital form, have been created taking as a reference their paper counterpart. Therefore “little has been done to adapt them to the need of their users”[12] (Tarp 2014: 80).

These shortcomings could well be the result of lack of communication or understanding between lexicographers and translators, as Hartmann pointed out some 25 years ago:

Translators ignore lexicographers, monolingual lexicographers ignore the work of their bilingual colleagues, the people working in so-called general areas ignore those in so-called technical specialisms. We can only function efficiently in society if we keep our own houses in order.

Hartmann 1989: 18

There are, however, other reasons to explain the limitations of bilingual specialized dictionaries and term banks. These include the complexity of the elements involved in the communication between cultures and languages in general, and in specialized fields such as legal translation,[13] in particular, as well as many other elements central to lexicography[14] and/or terminography,[15] such as the concept of equivalence. Gómez (2006: 216) speaks of dynamic meaning and anisomorphism and states that “due to the asymmetries experienced in any interlinguistic transfer, specialized bilingual dictionaries should approach meaning in an approximate way; otherwise, they could hardly reflect the equivalences between systems.”

However, the fact remains that studies carried out over the last years[16] show that bilingual specialized dictionaries have evolved less than the translators would like, and in most cases they “are useful in so far as they add explanations to their word lists but they still disappoint in that they do not fully meet all the requirements of legal translators” (Van Laer 2014: 75). Although Van Laer is here referring to legal dictionaries, this affirmation could be extended to almost all specialized fields. The fact that efficient equivalent search continues to be an unresolved issue can be seen in the interest shown by translation researchers in the recent literature.[17]

There are, of course, some exceptions to this generalization, such as the English-Spanish dictionary of medical terms Cosnautas[18] which has clearly been built for translators by translators and experts in the medical domain, or recent initiatives of translation researchers, such as Trandix (Durán and Fernández 2014). They are however few and far between and do not include all the types of resources translators need to consult in the specialized terminology search process.

We believe that current technological advances have provided us with the opportunity of overcoming the traditional limitations of existing equivalent search tools, as pointed out by Bothma (2011). In an attempt to solve the problem of the need for search tools fit for the translator’s task, we have used the potential of the information technologies to develop the prototype of a tailor-made tool for specialized translators that includes contextual and domain-specific information, corpora, terminological information and other innovative features.[19] It was decided to create an application that proved to be useful in the most difficult situation – for instance legal translation between systems that belong to different legal families – to ensure that the model could then be more easily adapted for other specialized fields.

2. Legal and communicative context for the prototype tool

The research project LAW10n (Localisation of Technology Law: Software Licensing Agreements) provided the perfect opportunity for creating the proposed prototype tool, since it focused on legal translation and, more specifically, the problem of translating into Spanish End-User License Agreements (EULA) that had been originally written in English, mostly from the United States. EULAs are a particularly suitable genre with which to work when creating a complex terminology search tool because two different approaches to translation may be taken depending on the translation brief and the legal use that will be made of the target text.

Given the fact that EULAs translated into Spanish by licensors are made available directly to users of licensed software in Spain, these documents have now attained legal status within Spanish law. Translated end-user license agreements are thus documents that have legal implications in Spain. Therefore, the translation of EULAs falls mostly into the category of instrumental translations as defined by Nord (1997: 45-52 and 127) where the reader expects “that the target text fits nicely into the target-culture text class or genre it is supposed to belong to” (Nord, 2006: 39). When the end user is a consumer, protected by European and Spanish laws, the target text becomes the only contract between the parties and therefore the only source of interpretation of its legal terms. In practice, this means that the target text should avoid the use of terms that are non-existent or unknown under Spanish law in order to ensure the intended legal interpretation. There are, however, cases in which the translated EULA (i.e., the target text in Spanish) is not a legal instrument because the license is not directed to a consumer but rather to a company or a professional. In these cases, the legal system of the source text (for example USA laws) is the one that rules, and the document in the target language (i.e., Spanish) is only informative, so that the users/readers have the information in their own language. Therefore, in this case the translations fall into the category of documentary translations as defined by Nord (1997: 45-52 and 127) where the reader of the target text knows that the text is a translation and is not supposed to be bothered by the “strangeness” of the target text, as pointed out by Nord (2006: 39) since the “purpose would be precisely not to resemble any text existing in the target culture repertoire.” This means that terms that are non-existent under Spanish law may be used in the form of calques or loan words and their meaning will always be determined by reference to the source legal system.

The research project LAW10n described in detail the process of translation of EULAs from English into Spanish after a thorough investigation including direct observation, interviews and questionnaires to translators and companies involved in London and Barcelona (see Orozco-Jutorán 2014a). The analysis of this process yielded different conclusions. One of them was the detailed description of the specific steps involved in the process that resulted in translations which did not take into account the purpose of the target text and often produced agreements that would be rendered void by a Spanish judge because they did not comply with the requirements of Spanish law.

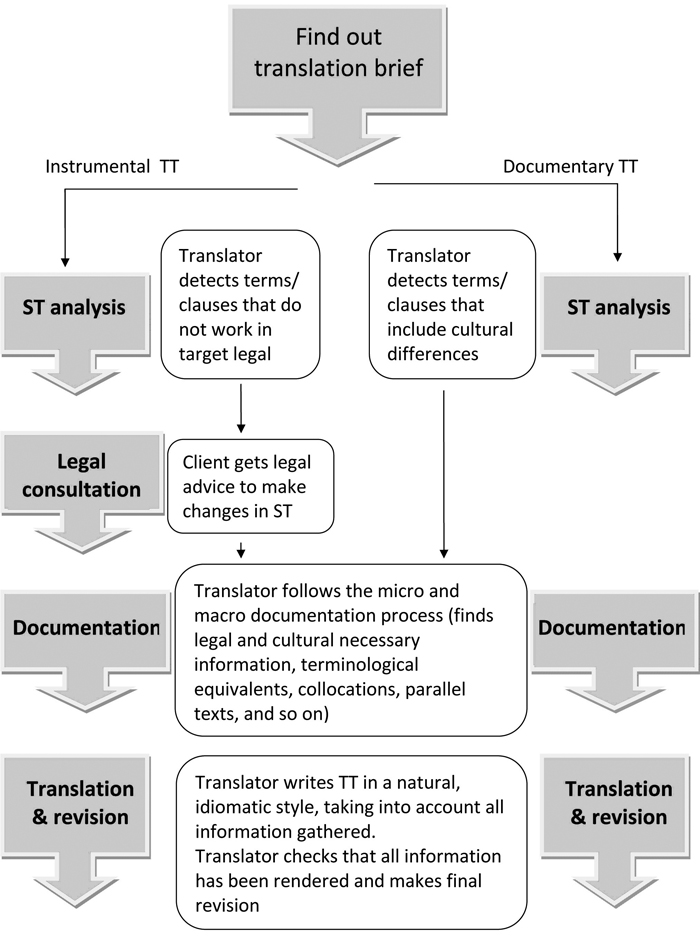

In the light of these findings, the “ideal” process of translation of EULAs was determined (Figure 1). If applied by translators and companies, this process would ensure that clients’ different translation briefs (instrumental or documentary) would be taken into account and the resulting translation would efficiently fulfill its communicative purpose thereby providing the best possible quality translation.

The LAW10n research team’s proposal (Figure 1) clearly differentiates between two possible translation briefs – and consequently two possible functions of the target text –right at the very beginning of the translation process. This clarification of the purpose of the target text ensures translators take one of two different first steps depending on the approach to be taken (instrumental or documentary). When the target text is to be used as a legal instrument, the analysis of the source text focuses on detecting the terms, phrases and/or clauses that would be inappropriate in translation in the target legal system, and this is reported to the client. The client then has the responsibility of consulting with a legal expert who can give advice and help the client to decide which legal terms and conditions are to be included in the target text, thereby ensuring that the text conforms to the requirements of the target legal system. The translator is then given the revised source text and begins the translation process, always mindful of the fact that the resulting text is to be used as a legal instrument.

When a documentary approach is taken, source text analysis focuses on the cultural differences that the text may include, so that any necessary decisions can be made at the beginning of the translation process, including possible consultation with client.

After that, the two approaches merge taking two more steps: one focusing on documentation, where the translator finds all the necessary information to complete the translation task in hand; and a second focusing on the actual translation and revision of the target text.

The difference between the translation process proposed for an instrumental or a documentary target text is efficiently established in the first two steps of the translation process, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Ideal process of translation of EULAs as proposed by LAW10n research team

Having determined the ideal process of translation, the LAW10n team then put a great deal of effort when creating the prototype tool into explaining the differences between an instrumental and a documentary approach to translating EULAs and providing translators with different translation solutions depending on the function of the text. Thus, the differences between instrumental and documentary translations are explained in the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ); an interactive questionnaire helps translators determine whether the target text is intended for instrumental or documentary purposes;[20] and the terminological entries give translators different translation solutions from which to choose depending on the translation approach (instrumental or documentary) adopted. At the syntactic level, the revised corpus includes notes that indicate whether the solution proposed is intended for documentary or instrumental use – or if it is valid for both approaches.

This difference between an instrumental or documentary approach is very specific to some legal translations and genres, and therefore does not need to be taken into account in many other translation domains, such as in most of the scientific or economic translations. In these cases, taking into account the possible cultural differences between the languages and cultures involved is enough. Therefore, for these domains, the tool would only offer one translation-oriented record which may include different types of equivalents and explain cultural differences that affect the term if there are any.

Besides these features, the prototype tool created includes translation-oriented terminological records, a revised corpus to consult collocations and verify lexical equivalents, and contextual information providing all the necessary legal information about EULAs in the legal systems involved, for example American, European and Spanish. The search process is thus speedy and efficient, and enables translators to make well-informed decisions based on reliable sources.

3. Contents of the prototype tool

The application, available online at http://lawcalisation.com/, contains four tools in a single website. On accessing the website, a general explanation of the application appears and eight tabs are presented. All information is provided in Spanish, since the prototype has been designed for use by translators who wish to translate EULAs from English into Spanish, for use in Spain. As explained in the main screen, only the use of the variety of Spanish spoken in Spain is contemplated at present, so that if the tool is to be used for translations into Argentinian or Mexican Spanish, for instance, the legal terminology and context of those countries and cultures would need to be added. One of the advantages of the prototype tool developed is precisely the fact that it has been designed for application in as many legal fields and language combinations as desired.

3.1. Informative tabs

Of the eight tabs currently present on the main screen of the website, the two on the right contain information about the team that developed the tool – the tab “EQUIPO LAW10n” (LAW10n team) – and about the different actions made by the team in order to make the project visible, that is, articles published in journals, conferences given and organized – the tab “DIFUSIÓN” (Dissemination).

3.2. Interactive tabs

The six remaining tabs on the left contain all the features of the application. The first tab, starting on the left-hand side of the website, is ADVERTENCIA (Warning). It provides information about two possible approaches to the translation of EULAs, i.e., instrumental or documentary (Section 2). It also contains a questionnaire that may be used by translators to determine whether the EULA to be translated is to be used for instrumental or documentary purposes. The questionnaire is interactive so that, depending on translators’ answers to each of the questions posed, they are directed either to the final result or to further questions until the final result is reached. The three possible final results are: (a) the text you are going to translate will be used as a legal instrument and it must therefore comply with Spanish legal requirements; we recommend you use the options marked as instrumental both at the corpus and translation records; (b) the text you are going to translate will be used as an informative tool and must therefore reproduce the original or source text legal requirements; we recommend that you use the options marked as documentary both in the corpus and translation records; (c) the end use of the target text is not absolutely clear; a lawyer should therefore advise the licensor, i.e., the client, so that a decision may be made as to whether the translated text will serve as a legal instrument or only an informative text.

The second tab P+F (FAQs) includes over 50 questions and answers on five different topics: (a) the translation of EULAs; (b) the use and features of the LAW10n website; (c) software licenses in the Spanish legal system; (d) copyrights that apply in EULAs and (e) standard contents of the EULAs produced in the USA.

The third tab, which gives access to translation-oriented terminological records, will be explained in detail in Section 3.3.

The fourth tab is DETECTOR (Detector) and contains a tool aimed at speeding up the terminology search. It enables translators to enter the text to be translated in a window – by writing or copy-pasting from any of the usual text formats, such as .txt .doc or .pdf. Then, by clicking on the button analizar (analyze), the tool finds: (i) all the terms included in the records of the tool and (ii) all the sentences or word chains included in the corpus of the tool. These features appear highlighted for translators – the terms in orange and the sentences or chains of words in yellow – so that just by clicking on them they can access records of all the terms in the text and the corpus of all the related sentences or words chains.

The fifth tab, NORMATIVA (Regulations) contains direct links to all the relevant Spanish and European laws and regulations regarding the legal context of EULAs, classified into six categories: Intellectual Property; Consumer Rights; Electronic Commerce and Electronic Contracts; Information Society Development; Personal Data Protection; Private International Law.

Finally, the sixth interactive tab is CORPUS, and contains a tool into which translators can enter any given word, chain of words or sentence, either in English or Spanish, and obtain all the paragraphs where the words/sentence entered appear in the corpus analyzed by members of the LAW10n Project. The results always appear in three columns, as in Figure 2: the source text in English on the left-hand side of the screen; the reviewed translation of the paragraph in Spanish in the centre of the screen, and the purpose of the translation – instrumental, documentary or indistinct – on the right hand-side of the screen.

This corpus is unique because it is a revised corpus. By revised we mean that the LAW10n research team analyzed, revised and edited the 75 end-user licenses, translated from English into Spanish, that they located[21] to ensure that they complied with all the legal, linguistic and communicative requirements to be considered adequate translations. Two other corpora of monolingual licenses in English and in Spanish were also used to build the tool. The result is a revised corpus where all linguistic levels (lexical, syntactic, style) have been taken into account in order to produce an idiomatic translation that is acceptable to the target reader. An example of revision at the linguistic level is, for instance, the use of capital letters in English legal documents. Capital letters are used to emphasize and denote areas of special importance so that they do not get overlooked by the reader. Too often, in legal translations from English into Spanish, these areas are wrongly translated into Spanish using the same emphatic system, i.e., capital letters, but this is not idiomatic or correct in Spanish, where bold letters or underlining is the traditional mechanism used to emphasize words or sentences.

Figure 2

Example of results of searching non-infringement in the corpus

Finally, the corpus has also been revised and edited from the legal point of view, in order to ensure that all legal terms are correctly used and to determine whether a specific sentence or clause is fit to be used as a legal instrument in Spanish – because it complies with Spanish law – or whether it is fit to be used as a mere informative document that explains in Spanish the agreement that complies with the source country’s laws. In some cases, the sentence or clause could be used for both purposes, and then it is duly noted.

3.3. Translation-oriented terminological records

The third tab FICHAS (Records) contains terminological records, i.e., all the information needed by translators to be able to correctly translate a specialized term in the field[22] of EULAs. In cases in which the same term in English would need a different translation solution depending on whether the text is to be used for instrumental or documentary purposes, there is a separate record for each option. Such is the case for the terms strict liability, merchantability or non-infringement, for instance. In cases where the same solution serves for both options, only one record is provided. This is the case for the terms tort, statute, severability, remedy, consideration or representation, for instance.

Each record contains seven fields which together provide all the information needed by translators to be able to fully comprehend the original term in English in its context before choosing an equivalent term in Spanish, having clearly understood the legal implications of the term used. The seven fields included in each record (as shown in Figures 3 and 4) are:

Definición (Definition): Definition of the English term together with its source (i.e., “Black’s Law Dictionary”).

ES: Term or terms proposed to translate English term into Spanish. Next to ES there is either the word instrumento, to remind the user that these solutions are adequate if the purpose of the translated text is to be used as a legal instrument (as in Figure 3), or the word documento, when the solutions proposed in the record are adequate for a translated text for documentary or informative purposes, as in Figure 4.

Técnicas de traducción (Translation techniques): Next to each proposed solution in Spanish in Field b), on the right and in orange colour – orange indicates throughout the website that the word or sentence marked in this colour is a hyperlink that can be accessed by clicking on it – there is the acronym of the translation technique used for translating the term. For instance, “EF” stands for Equivalente funcional (Functional equivalent), and a whole list and explanation of the possible translation techniques used can be found by clicking on any given technique, marked in orange. For a thorough explanation of the different possible techniques considered and their definition, see Orozco-Jutorán 2014b.

Subcampo (Sub-domain): All records currently belong to the same sub-thematic field, that is, software licenses, but as this tool is a prototype, it is important that this feature appears in all records in order to be able to include other fields and sub-domains in the future.

Opciones no recomendadas (Solutions not recommended): This field is unique in that it is not contained in any dictionary or terminological database that we know of and is of particular importance to translators since there are many translation solutions that are bad solutions (as mistranslations). These bad solutions are however widespread on the Internet where we can find many examples of badly translated EULAs. It is important to bear in mind that a solution can only be considered a bad solution in relation to the domain under study (software licenses) and the approach defined in the specific record consulted, so that a bad solution listed in the record of a term used for instrumental purposes (such as mercantibilidad as a translation of merchantability for instrumental purposes) may be listed as an appropriate solution for the same term in the record used for documentary purposes.

Comentarios para la traducción (Translation comments): This field is also unique to the tool developed and is one of the features that saves translators most time and effort. It includes all the relevant comments on the legal and linguistic contexts of terms in English and Spanish all in one place, thereby providing translators with the information they would usually have to consult in several places (monolingual specialized dictionaries, multilingual databases, law reference publications, comparative law treaties, etc.).

Contexto (Context): This field includes, on the left-hand side of the screen, one of the original contexts in which a term was found (all terms were found in a corpus of original EULAs in English) and, on the right-hand side of the screen, a revised translation of the sentence or paragraph in Spanish. The term the translator is consulting appears in bold type in both contexts, to enhance visibility. It should be noted that a comparison of the contexts appearing in Figures 3 and 4 shows that the contexts and the translations change, since they have been chosen to be representative of two different approaches to translation, instrumental or documentary. By clicking on either of the two contexts, English or Spanish, the translator can access the corpus tool and see other contexts where the same term can be found with its translation into Spanish.

Figure 3

Example of translation record of the term non-infringement for an instrumental approach

As shown in Figure 3, each record has a heading showing whether the record is intended for instrumental or documentary purposes. In this case, Figure 3 displays the instrumental approach for the term non-infringement, while Figure 4 displays the record for the documentary translation of the same term.

In Figure 3 we can see how, besides the definition (Definición) and the sub-domain (Subcampo) of the term on the left-hand side of the screen, the special features of the term translated for instrumental purposes (ES instrumento) appear on the right-hand side.

First of all, four possible translation solutions for the term are proposed. The first is garantía de no infracción de los derechos de propiedad intelectual, industrial u otros derechos registrados de terceros, which is marked in orange as an “EC” (Equivalente contextual, i.e., contextual equivalent, since this translation solution can be used only in some contexts). Then, three other possible translation solutions are provided: (a) no vulneración de los derechos de propiedad intelectual e industrial; (b) no violación de los derechos de propiedad intelectual e industrial; and (c) no violación de los derechos de terceros, all marked as “TP” (Traducción perifrástica or descriptive translation). The mainly legal but also linguistic explanations that help translators choose between using one translation solution or another, depending on the particular communicative situation encountered, are found in the translation comments (Comentarios para la traduccion) below.

Immediately below the translation solutions proposed are the solutions that are not recommended (Soluciones no recomendadas). These include nine solutions for the term non-infringement that were found in translations in search engines, dictionaries and corpus on the Internet and that are considered to be bad translation solutions or inappropriate solutions for the reasons explained in the translation comments of that same record. The solutions that are not recommended are ausencia de incumplimiento; incumplimiento; incumplimiento de los derechos; ausencia de infracción; ausencia de violación de derechos; derechos no infringidos; inexistencia de infracción; no incumplimiento and no incumplimiento de los derechos.

Below these terms, in the translation comments, is an explanation in layman’s language of the legal concept behind the term non-infringement: The source context or legal system and the target legal system are contrasted and the recommendations made for using the different translation solutions listed explained.

Finally, at the bottom left-hand side of the screen, an example is given of the way in which the term non-infringement is used in English, together with the corresponding translation proposed in Spanish. The translation solution used, which is one of the proposals made above in the same record, garantía de no infracción de los derechos de propiedad intelectual, industrial u otros derechos registrados de terceros, is highlighted in bold letters. When the translator clicks on any of the contexts, in English or in Spanish, direct access is given to the revised corpus for this term (see Figure 2).

As for the translation solutions proposed for the same term, non-infringement, Figure 4 shows the translation-oriented record proposed for a documentary approach to translation of this term.

Figure 4 shows that some of the contents of this record are the same as in the instrumental-oriented record displayed in Figure 3; for instance, the definition of the term and the sub-domain. However, the translation solutions proposed and the comments on the solutions are different. Thus, the contextual equivalent offered as a translation solution in Figure 3, garantía de no infracción de los derechos de propiedad intelectual, industrial u otros derechos registrados de terceros, is not deemed a good solution here, since it refers to a reality existing in the Spanish legal system that would not make any sense in a documentary translation, whilst, in this case, the three descriptive translations that appear in Figure 3 are considered good solutions and are thus included. A fourth translation solution, garantía de no infracción is added and marked again as a TP (descriptive translation). The comments on the solutions given are completely different from the ones displayed in the instrumental-oriented record, for obvious reasons.

Figure 4

Example of translation record of the term non-infringement for a documentary approach

Finally, the context included for the documentary-oriented record in Figure 4 is also different from the one displayed in the instrumental-oriented record. The documentary-oriented term in the revised corpus is the first proposed translation solution, garantía de no infracción. This is a noun phrase, that involves merging the noun (garantía) with the subject of the main sentence and merging the phrase (de no infracción) with the other phrases included in the paragraph, resulting in a sentence which is perfectly natural and idiomatic in Spanish, “…incluidas entre otras las garantías implícitas de comerciabilidad e idoneidad para una finalidad particular, de calidad satisfactoria y de no infracción.”

4. Conclusion

A prototype tool has been created to complement the translation model for end-user license agreements proposed by members of the LAW10n research project. This translation model was designed to ensure, on the one hand, that target texts fulfilled the legal requirements of the target country whilst, on the other, remaining faithful to the spirit and legal effects of the source text. The prototype tool developed cannot only improve the quality of translation of EULAs by making the terminology search more efficient, but it also represents a new approach to the development of resources that respond more closely to the current needs of specialized translators.

We believe that specialized translators would welcome the creation of more tools that replicate some of the features of the prototype tool presented in this paper, namely, the translation-oriented terminological records, the revised corpus and contextual information.

The introduction of translation-oriented entries in existing tools and dictionaries would already be very good news for translators in any domain, since much time and effort is currently spent on consulting bilingual dictionaries, comparing the results found in monolingual dictionaries, checking which type of equivalents are proposed as translation solutions (for instance which translation technique has been used to propose an equivalent), and verifying that the concept behind the term chosen in the target language is the one they are indeed looking for.

We find the inclusion of comments on the acceptability of terminological options in different translation scenarios particularly useful, since this can help translators make informed decisions when choosing between different translation solutions. In the case of legal translation, the benefits of the proposed entries go far beyond this, since they present the translator with an exercise in comparative law, which sometimes proves to be very difficult and time consuming to carry out.

The revised corpus may also be most useful in the search for good quality, idiomatic translations in any domain, because it would wean translators off many of the existing corpora online, which unfortunately contain documents of all kinds and sources that often include error-ridden translation texts.

To sum up, the prototype tool presented aims at helping the specialized translator to save time and effort and to make better informed decisions regarding solutions to translation problems, which is the basis for good quality translation. We believe that our prototype can be easily adapted to any specialized domain simply by using the features that are most appropriate for the specific domain and language combination in hand. In the case of scientific translation, for example, a tool including the translation-oriented records, the revised corpus, the FAQs tab, and perhaps substituting the Rules tab with a tab containing contextual or factual information about the sub-domain being translated, would prove to be very useful, and it could be done in any given language combination.

In case the professional community of translators finds the tool useful, it would be very interesting to carry out an evaluation concerning the use of the tool and its weaknesses and strengths, which may then lead to further development of the prototype.

With this prototype tool we hope to contribute to the development of new applications that take advantage of the technological advances we have access to today to help the specialized translator. We strongly believe that if translators have access to good quality information that allows them to make informed decisions, this will have a positive impact on the quality of their translations. In other words, we hope to contribute added value to the human dimension of quality management in translation.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

For instance Tarp (2014) provides an in-depth review of the literature on the subject.

-

[2]

See Bestué 2016; Sales 2005; Castro 2004; Catenaccio 2005; Corpas 2004.

- [3]

- [4]

- [5]

- [6]

- [7]

-

[8]

See for instance Alcina and Gamero 2002; Corpas and Roldán 2014; Engberg 2013; Sales 2005; Suau 2010; Nord 1991.

-

[9]

For instance Agnese, 2001; Cicile and Voituriez 2005; Gallego 2014; Mayor 2010; Prieto Ramos 2013; Sager 2002.

-

[10]

Abu-Ssaydeh 1991; Adamska-Salaciak 2010. Varantola 1998.

-

[11]

Fuertes-Olivera 2013; Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014; Granger and Paquot 2012.

-

[12]

Our translation from Spanish: “poco se ha hecho para adaptarlos a las necesidades de los usuarios en cada tipo de situación.”

-

[13]

See for example Harvey 2000; Šarčević 1985 and 1989; Sandrini 1996; Peruzzo 2012.

-

[14]

See for instance Garner 2003; Tarp 2008; Bergenholtz and Tarp 1995; De Schryver 2012.

-

[15]

See for instance Bowker and Mewyer 1993; Cabré 2003; Sager 1990 and 2002: Faber et al. 2006; Sandrini 1999.

-

[16]

For instance, see De Groot and Van Laer 2008; Iamartino 2006; Thiry 2009; Kim-Prieto 2008.

-

[17]

For instance, a special number of the international translation journal MONTI (number 6) was devoted to this subject in 2014, and other publications include Bowker 2006; Durán Muñoz 2010; Fuertes-Olivera 2010; Fuertes-Olivera and Bergenholtz 2011; Fuertes-Olivera and Nielsen 2012; Heid et al 2012; Humblé 2010; Nielsen 2013; Pastor and Alcina 2010; Prinsloo et al 2012; San Vicente 2006; Sin-Wai 2004; Tarp 2008; Zucchini 2011.

- [18]

-

[19]

The design and development of the tool has been carried out by the interdisciplinary research team LAW10n, integrated by the author and eight other researchers from five universities and lead by Dr. Olga Torres-Hostench. The research project has been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Official reference FILO: FI2010-22019).

- [20]

-

[21]

The list of the licenses used can be seen in <http://lawcalisation.com/contenidos-y-fuentes>.

-

[22]

For a thorough analysis of the unique features of the translation-oriented records, see Prieto and Orozco-Jutorán 2015.

Bibliography

- Abadal Falgueras, Ernest (2004): Contenidos digitales en Internet: algunos problemas. In: Ana Cristina García de Toro and Isabel García Izquierdo, eds. Experiencias de traducción. Reflexiones desde la práctica traductora. Castellón: Universitat Jaume I, 31-42.

- Abu-Ssaydeh, Abdul-Fattah (1991): A Dictionary for Professional Translators. Babel 37(2):65-74.

- Adamska-Salaciak, Arleta (2010): Examining Equivalence. International Journal of Lexicography 23(4):387-409.

- Agnese, Alicia (2001): What, When and Why in Key English-Spanish Financial Terminology. The ATA Chronicle. 30(5):46-48.

- Alcina, Amparo and Gamero, Silvia, eds. (2002): La traducción científico-técnica y la terminología en la sociedad de la información. Castellón: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I.

- Bergenholtz, Henning and Tarp, Sven (1995): Manual of Specialised Lexicography. The Preparation of Specialised Dictionaries. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Bestué, Carmen (2016): Translating law in the digital age. Translation problems or matters of legal interpretation? Perspectives. 24:576-590.

- Bothma, Theo J. D. (2011): Filtering and Adapting Data and Information in an Online Environment in Response to User Needs. In: Pedro Fuertes Olivera and Henning Bergenholtz, eds. e-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography. London & New York: Continuum, 71-102.

- Bowker, Lynne and Meyer, Ingrid (1993): Beyond ‘Textbook’ Concept Systems: Handling Multidimensionality in a New Generation of Term Banks. In: Klaus-Dirk. Schmitz ed., Proceedings of Terminology and Knowledge Engineering (TKE’93). Frankfurt: IndeksVerlag, 123-137.

- Bowker, Lynne ed. (2006): Lexicography, Terminology, and Translation: Text-based Studies in Honour of Ingrid Meyer. Ottawa: Université d’Ottawa.

- Cabré, Teresa (2003): Theories of Terminology: Their Description, Prescription and Explanation. Terminology, 9(2):163-199.

- Calvo, Cesáreo and Calvi, MariaVittoria (2014): Translation and lexicography: a necessary dialogue. MonTI. 6:37-62.

- Castro, Xose (2004): Teletrabajo: Internet como recurso documental y profesional. In: Consuelo Gonzalo García and Valentín García Yebra, eds. Manual de documentación y terminología para la traducción especializada. Madrid: Arco, 399-407.

- Catenaccio, Paola (2005): Internet per traduttori: le risorse in rete. In: Giuliana. Garzone, ed. Experienze del tradurre. Aspettiteorici e applicative. Milano: Franco Angeli, 215-240.

- Cicile, Jan-Michel and Voituriez, Maurice (2005): Terminologie bancaire, économique et financière, français-anglais / anglais-français. Traduire 204:47-50.

- Corpas Pastor, Gloria (2004): La traducción de textos médicos especializados a través de recursos electrónicos y corpus virtuales. In: Luis. González and Pollux Hernúñez, eds. Las palabras del traductor. Actas del II Congreso El Español, Lengua de Traducción. Bruselas: ESLETRA, 137-164.

- Corpas Pastor, Gloria and Roldán Juárez, Marina (2014): Análisis de necesidades documentales y terminológicas de médicos y traductores médicos como base para el diseño de un diccionario multilingüe de nueva generación. MonTI 6:167-202.

- De Groot, Gerard. and Van Laer, Conrad (2008): The Quality of Legal Dictionaries: An Assessment. Maastricht Faculty of Law Working Papers, 6:1-63. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1287603 [Accessed 1 April 2015].

- De Schryver, Gilles-Maurice (2012): Trends in Twenty-Five Years of Academic Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography, 25(4):464-506.

- Durán Muñoz, Isabel. (2010): Specialized lexicographical resources: a survey of translators’ needs. In: Sylviane Granger and Magali Paquot, eds. eLexicography in the 21st century: New Challenges, new applications. Proceedings of ELEX 2009. Cahiers du Cental, vol. 7. Lovaine-La-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, 55-66.

- Durán Muñoz, Isabel and Fernández Sola, Alejandro (2014): Trandix: herramienta proactiva para la búsqueda terminológica del traductor y su evaluación. MonTI 6: 115-139.

- Engberg, Jan (2013): Comparative Law for Translation: The Key to Successful Mediation between Legal Systems. Legal Translation in Context: Professional Issues and Prospects. In: Anabel Borja Albi and Fernando Prieto Ramos, eds. Oxford, etc.: Peter Lang, 9-25.

- Faber, Pamela et al. (2006): Process-oriented Terminology Management in the Domain of Coastal Engineering. Terminology, 12(2):189-213.

- Fuertes Olivera, Pedro and Bergenholtz, Henning, eds. (2011): e-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography. London and New York: Continuum.

- Fuertes Olivera, Pedro (2013): The theory and practice of specialised online dictionaries for translation. Lexicographica 29:69-91.

- Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro and Nielsen, Sandro (2012): Online dictionaries for assisting translators of LSP texts: The Accounting Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 25(2):191-215.

- Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro, ed. (2010): Specialized Dictionaries for Learners. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, 69-82.

- Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro and Tarp, Sven (2014): Theory and Practice of Specialised Online Dictionaries. Lexicography and Terminography. Lexicographica Series Maior, Berlin/ Boston: De Gruyter.

- Gallego Hernández, Daniel (2014): Terminología y traducción económica francés-español: evaluación de recursos terminológicos en el ámbito contable. MonTI, 6:141-166.

- Garner, Bryan (2003): Legal lexicography: A view from the front lines. English Today, 19:33-42.

- Gómez González-Jover, Adelina (2006): Meaning and anisomorphism in modern lexicography. Terminology 12(2):215-234.

- Granger, Sylviane and Paquot, Magali, eds. (2012): Electronic Lexicography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hartmann, Reinhard Rudolf Karl. (1989): Sociology of the Dictionary User: Hypotheses and Empirical Studies. In: Franz J. Hausmann, Oskar Reichmann, Herbert E. Wiegand and Ladislav Zgusta, eds. Worterbucher. Dictionaries. Dictionnaires. Ein internationales HandbuchzurLexikographie. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter, 102-111.

- Harvey, Malcolm (2000): A Beginners Course in Legal Translation: the Case of Culture-Bound Terms. La traduction juridique: Histoire, théorie(s) et pratique / Legal Translation: History, Theory/ies, Practice. Bern and Geneva: ASTTI and ETI, 357-369.

- Heid, Ulrich, Prinsloo, Danie J. and Bothma, Theo (2012): Dictionary and corpus data in a common portal: state of the art and requirements for the future. Lexicographica 28:269-291.

- Humblé, Philippe (2010): Dictionnaires et traductologie: le paradoxe d’une lointaine proximité. Meta 55(2):329-337.

- Iamartino, Giovanni. (2006): Dal lessicografo al traduttore: un sogno che si realizza? In: Félix San Vicente, ed. Lessicografia bilingue e traduzione: metodi, strumenti, approcci attuali. Monza: Polimetrica, 101-132.

- Kim-Prieto, Dennis (2008): En la tierra del ciego, el tuerto es rey: Problems with Current English-Spanish Legal Dictionaries, and Notes toward a Critical Comparative Legal Lexicography. Law Library Journal, 100(2):251-278.

- Mayor Serrano, María Blanca. (2010): Necesidades terminológicas del traductor de productos sanitarios: evaluación de recursos (EN, ES). Panacea 11(31):10-14.

- Nielsen, Sandro. (2013): Domain-specific knowledge in lexicography: how it helps lexicographers and users of accounting dictionaries intended for communicative usage situations. Hermes, Journal of Language and Communication in Business 50:51-60.

- Nord, Christiane (1991): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi.

- Nord, Christiane (1997): Translating as a Purposeful Activity. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Orozco-Jutorán, Mariana (2014a): The EULAs labyrinth: mapping the process. Across Languages and Cultures, 15 (2):199-217.

- Orozco-Jutorán, Mariana (2014b): Propuesta de un catálogo de técnicas de traducción: la toma de decisiones informada ante la elección de equivalents. Hermeneus, Revista de Traducción e Interpretación, 16:233-264.

- Pastor, Verónica; Alcina, Amparo (2010): Search Techniques in Electronic Dictionaries: A Classification for Translators. International Journal of Lexicography 23(3):307-354.

- Peruzzo, Katia (2012): Secondary term formation within the EU: term transfer, legal transplant or approximation of Member States’ legal systems? Journal of Specialised Translation, 18:175-186.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando (1998): La terminología procesal en la traducción de citaciones judiciales españolas al inglés. Sendebar, 9:115-135.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando (2013): Traducción institucional y cogestión de neologismos: entre la armonización y la congestión terminológicas. In: C. Sinner, ed. Comunicación y transmisión del saber entre lenguas y culturas.Munich: Peniope, 387-400.

- Prieto Ramos, Fernando and Orozco-Jutorán, Mariana (2015): De la ficha terminólogica a la ficha traductólogica: hacia una lexicografía al servicio de la traducción juridical. Babel, 61(1):110-130.

- Sager, Juan (1990): A Practical Course in Terminology Processing. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Sager, Juan (2002): La terminología y la traducción en la sociedad de la información. In: Amparo Alcina and Silvia Gamero, eds. La traducción científico-técnica y la terminología en la sociedad de la información. Castellón: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, 17,17-44.

- Sales, Dora, ed. (2005): La Biblioteca de Babel: documentarse para traducir. Granada: Comares.

- San Vicente, Félix, ed (2006): Lessicografia bilingue e traduzione: metodi, strumenti, approcci attuali. Monza: Polimetrica.

- Sandrini, Peter (1996): Comparative Analysis of Legal Terms: Equivalence Revisited. In: Christian Galinski and Klaus-Dirk Schmitz, eds. Terminology and Knowledge Engineering (TKE ‘96). Frankfurt and Main: Indeks, 342-351.

- Sandrini, Peter (1999): Legal Terminology: Some Aspects for a New Methodology. Hermes, 22:101-112.

- Šarčević, Susan (1985): Translation of Culture-Bound Terms in Laws. Multilingua, 4(3):127-133.

- Šarčević, Susan (1989): Conceptual Dictionaries for Translation in the Field of Law. International Journal of Lexicography, 2(4):277-293.

- Sin-Wai, Chan, ed. (2004): Translation and Bilingual Dictionaries. Tübingen: Max Miemeyer.

- Suau Jiménez, Francisca (2010): La traducción especializada (en inglés y español en géneros de economía y empresa). Madrid: Arco Libros.

- Tarp, Sven (2008): Lexicography in the Borderland between Knowledge and Non-knowledge.General Lexicographical Theory with Particular Focus on Learner’s Lexicography. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Tarp, Sven (2014): Reflexiones sobre el papel y diseño de los diccionarios de traducción especializada. MonTI, 6:63-89.

- Thiry, Bernard (2009): Análisis crítico de algunos diccionarios jurídicos publicados. Entreculturas, 1:443-468.

- Van Laer, Coen J.P. (2014): Bilingual Legal Dictionaries: Comparison Without Precision? In: Máirtín Mac Aodha, ed. Legal Lexicography. Farnham: Ashgate, 75-87.

- Varantola, Krista. (2002): Use and Usability of Dictionaries: Common Sense and Context Sensibility? In: Marie-Hélène Corréard, ed. Lexicography and Natural Language Processing. A Festschrift in Honour of B.T.S. Atkins: Euralex, 30-44.

List of figures

Figure 1

Ideal process of translation of EULAs as proposed by LAW10n research team

Figure 2

Example of results of searching non-infringement in the corpus

Figure 3

Example of translation record of the term non-infringement for an instrumental approach

Figure 4

Example of translation record of the term non-infringement for a documentary approach

10.7202/044243ar

10.7202/044243ar