Abstracts

Abstract

The integration of the concept of “social norm” into research on conference interpreting dates back to the late 1980s (Shlesinger 1989). This paper will show that conference interpreting is governed by role-related normative expectations which ultimately can all be traced back to the metaphoric concept of interpreters as conduits. This metaphoric concept that can be found in so many of the extratextual (re)sources on conference interpreting (Toury 1995) is extremely binding for conference interpreters and can therefore be regarded as an omnipotent norm – a supernorm that governs it all. Not only professional bodies such as the International Association of Conference Interpreters (AIIC), probably the most influential and powerful norm-setting authority in the field, but also individual authoritative personalities play a key role in promoting this supernorm. It is only in recent years that this supernorm, which demands that interpreters passively channel a message from one side or party to the other and thus tries to prevent an interpreter’s agency, has been challenged by empirical research (Angelelli 2004; Diriker 2004; Zwischenberger 2013). The discussion on norms in simultaneous conference interpreting will be enhanced by some selected findings of a web-based survey which was conducted among AIIC members. The survey’s main objective was to find out whether and to what degree professional conference interpreters adhere to the supernorm so strongly advocated by their professional body.

Keywords:

- conference interpreting,

- AIIC,

- social norm,

- supernorm,

- web-based survey

Résumé

L’intégration du concept de « norme sociale » dans la recherche sur l’interprétation de conférence date de la fin des années 1980 (Shlesinger 1989). Cet article montrera que l’interprétation de conférence est régie par des attentes normatives de stéréotypes qui remontent, en fait, au concept métaphorique de l’interprète comme simple « conduit ». Ce concept métaphorique, si fréquent dans les (res)sources extratextuelles en matière d’interprétation de conférence (Toury 1995), est un impératif pour les interprètes de conférence et peut donc être considéré comme une norme omnipotente – comme une supernorme qui gouverne tout. Les associations professionnelles telles que l’Association internationale des interprètes de conférence (AIIC), probablement l’autorité exerçant l’influence la plus grande sur les normes dans ce domaine, mais aussi des personnalités jouissant d’une certaine autorité, jouent un rôle clé dans la promotion de cette supernorme. Or, ces dernières années, cette supernorme qui demande aux interprètes de transmettre « passivement » un message et qui tente d’empêcher l’interprète de s’impliquer activement est contestée par la recherche empirique (Angelelli 2004 ; Diriker 2004 ; Zwischenberger 2013). La discussion sur les normes dans le domaine de l’interprétation de conférence simultanée sera enrichie par quelques résultats sélectionnés d’un sondage en ligne, réalisé parmi des membres de l’AIIC. L’objectif principal de ce sondage a été de découvrir si et dans quelle mesure les interprètes de conférence professionnels s’en tiennent à cette supernorme si ardemment défendue par leur association professionnelle.

Mots-clés :

- interprétation de conférence,

- AIIC,

- norme sociale,

- supernorme,

- sondage en ligne

Article body

1. Introduction

Toury (1980) was the first translation scholar to introduce the concept of norms into translation studies. In this first and introductory phase, research on norms was primarily conducted in the field of literary translation.

Toury (1999: 14) defined norms as “the translation of general values and ideas shared by a group – as to what is conventionally right and wrong, adequate and inadequate – into performance instructions appropriate for and applicable to particular situations.” From this definition it becomes clear that the function of norms consists in promoting a certain (group) ideology. Furthermore, norms are also supposed to make life easier as they bring about behavioural regularities and thus help predict how people will behave in certain situations (Chesterman 1999: 93).

It should be pointed out, however, that to date no uniform and consensual definition of the norm concept has been established – either in translation studies or in sociology where the concept has its roots. In both sociology and translation studies, norms are very often traced back to values. Values represent attitudes, preferences, behavioural expectations and prescriptions. In addition, expectations are very frequently directly related to the norm concept in literature on sociology and translation. They can be of normative character, depending on how binding they are: “What I mean by a norm is neither more or less than a kind of loaded expectation” (Hermans 1997: 7).

As a result of Toury’s pioneering work, norms have become a key concept in translation studies. In interpreting studies the same concept has often been used to account for phenomena which cannot be explained by the cognitive paradigm alone (Gile 1999).

Shlesinger (1989) was the first interpreting scholar to apply the norm concept to research on conference interpreting. Shlesinger (1989), however, doubted the existence of norms in the field of conference interpreting as the profession was still rather young, whilst also highlighting the difficulties involved in carrying out research on norms in interpreting. She pointed out the lack of representative interpreting corpora[1] and underlined the difficulties of obtaining permission to observe interpreters at work and record them. In her contribution on the extension of norms to the field of conference interpreting, Shlesinger (1989) exclusively referred to what Toury (1995: 65) would call “textual sources.” These sources comprise an analysis of a translation or a textual comparison of a source and target text allowing an investigation of the professionals’ regularities in their actions. Consequently, norms can be deduced from this and separated from idiosyncrasies.

As a reaction to Shlesinger (1989), Harris (1990) indicated a handful of socio-professional norms such as the norm of interpreting in the first person, the norm of an interpreting turn[2] not lasting longer than 20-30 minutes in simultaneous interpreting, the norm advocated by Western European interpreter training institutions, and notably also AIIC to only interpret into one’s A language, etc. The empirical proof of these norms cannot be found in textual sources alone, but one would also need to use what Toury (1995: 65) calls “extratextual sources.” These sources refer to prescriptive comments on translations or translators made by insiders (translators, editors, publishers, etc.) as well as outsiders to the profession.

The focus of the present paper will be on the extraction of norms from extratextual sources which regulate and dominate the belief system in the field of simultaneous conference interpreting. There will be an extraction of norms from the metatexts generated by norm-giving authorities such as AIIC and individual pioneers alike in the field of conference interpreting. In a second phase it will be analysed via the help of a web-based survey[3] conducted among AIIC members whether and to which degree professional conference interpreters adhere to the norm(s) extracted.

Firstly, however, the theoretical background of the norm concept will be analysed in greater depth. In the absence of a uniform and consensual definition of the norm concept, certain indicators of norms may be of help to better comprehend what could constitute a norm.

2. Norm indicators

The German sociologist Eichner (1981) listed some criteria which can be regarded as indicators of the existence of a social norm.

As the first indicator Eichner (1981: 15) named regularity in social behaviour. Yet Toury (1999) warned against confusing observable regularities in social behaviour with social norms: “Whatever regularities are observed, they themselves are not the norms. They are only external evidence of the latter’s activity, from which the norms themselves (that is, the “instructions” which yielded those regularities) are still to be extracted” (Toury 1999: 15).

In relation to the regularity of social behaviour, the use of sanctions is a further norm indicator (Eichner 1981: 24-38). According to Popitz (2006: 69) one can only speak of a norm if a deviation from an expected behavioural regularity has the use of sanctions as a consequence.

A further indicator of norms is the use of orders or imperatives. In this respect, social norms can be regarded as a class of speech acts which determine the behaviour of people. On the one hand, these speech acts or social norms may actually immediately change a person’s behaviour as a consequence which can be observed and perceived. The social norm does have a binding character for a certain group of people if they are confronted with its respective speech act and react accordingly. On the other hand, speech acts as social norms can also operate on a more abstract and less immediately and directly observable level. One can also speak of a norm if a given speech act appears with a certain frequency within a group of people and/or if the behaviour prescribed by the speech act occurs with regularity (Eichner 1981: 42-46). In the field of conference interpreting, the norms of interpreting in the first person and of being loyal to a speaker and his/her original are examples of normative speech acts which appear regularly and frequently in the oral and written discourses of the profession.

The last indicator which Eichner (1981: 46-75) named was behavioural predications. A certain type of behaviour is evaluated and associated with a certain degree of correctness, appropriateness, etc. If a certain type of behaviour is judged according to its correctness and appropriateness, then norms of correctness, appropriateness, etc. surely exist too. Furthermore, there must be underlying normative instructions too: “As long as there is such a thing as appropriate vs. inappropriate behaviour (according to an underlying set of agreements), there will be a need for performance instructions as well” (Toury 1999: 15). This also shows that any kind of judgement and evaluation is governed by and based on norms. Thus, one of the most prominent research topics in conference interpreting – quality – which was empirically realized mainly with the help of questionnaires, is eventually also an investigation of and into norms (Zwischenberger 2013).

3. (Re)sources for the empirical proof of norms

The lack of a consensus regarding the definition of the norm concept also gives rise to dissent concerning how best to investigate social norms as a consequence.

As mentioned above, Toury (1995) proposed textual as well as extratextual sources for the empirical proof of norms. For the field of interpreting, Gile (1999) points out that research into norms is probably best done using extratextual (re)sources:

[…] I believe that research about norms does not have to rely on large speech corpora. In the field of interpreting, such research is probably more efficiently done by asking interpreters about norms, by reading didactic, descriptive and narrative texts about interpreting (what Toury, 1995: 65 calls ‘extratextual’ sources), by analyzing user responses, and by asking interpreters and non-interpreters to assess target texts and to comment on their fidelity […].

Gile 1999: 100

Gile (1999: 101-104) himself presented the results of an assessment of the fidelity norm or the norm of the interpreter’s loyalty towards a speaker and his/her original in his contribution. The results of the case study showed a relatively high degree of variability in the assessment of this norm by a group of professional interpreters and non-interpreters.

Ten years after her extension of the discussion of norms from translation to interpreting studies, Shlesinger (1999) was much less critical about the existence of norms in interpreting and agreed on the above quotation according to which extratextual sources are particularly appropriate for research on norms in conference interpreting: “It is there that one finds a generous sprinkling of “should”s, “must”s and “ought to”s, representing what interpreters are expected to do under different circumstances” (Shlesinger 1999: 67).

Diriker (1999) was the first interpreting scholar to use extratextual resources in the form of written discourse on simultaneous conference interpreting generated by scholars of translation studies in order to find out more about norms in interpreting. She problematized and questioned the discourse on simultaneous interpreting with the help of critical discourse analysis (CDA).

In later works she also investigated written discourses on simultaneous interpreting generated by professional organizations, the media, academia outside the field of translation studies, etc. (Diriker 2003; 2004). Apart from an analysis of the written, published discourse on simultaneous interpreting, Diriker (1999: 78) also explicitly mentioned questionnaires and in-depth interviews as further extratextual sources from which to gain insights into the norms advocated by insiders and outsiders to simultaneous interpreting alike.

Marzocchi (2005) analyzed various codes and pronouncements on the conduct of interpreters to deduce norms from it and integrated the concept of ethics into the discussion on norms in conference interpreting.

Schjoldager (1995/2002) was the first interpreting scholar to investigate norms via a text corpus, thus basing her work on a textual resource. In her research she focused on the didactic setting and compared the transcribed simultaneous interpretation of novice interpreting students with those of advanced students. She also included translation students and professional interpreters into her experiment.

One of the most recent contributions to the investigation of norms in translation studies is the ethnographic research on the professional socialization of EU conference interpreters undertaken by Duflou (2007). In her PhD project she investigates the socio-professional norms of conference interpreters working for the European Commission and those who work for the European Parliament. For her project she uses extratextual resources (metadiscourses of the interpreting services of the EU institutions or in-depth interviews with the service’s interpreters) as well as textual resources (an interpretation corpus consisting of the output produced by the Dutch, English and Polish booths).

After having clarified what constitutes a norm and how it can be extracted, one of the pending questions to be answered is that of who establishes and validates norms.

4. Norm authorities

According to Chesterman (1993: 5-7) norms are validated either by their very existence or by a norm authority. He cites the norms governing queue behaviour in many societies as an example of norms that, despite not being laid down by an authority, are nevertheless followed since they are considered to constitute rational and desirable behaviour. It may, however, be questioned whether the norms governing the behaviour and belief system of interpreters or translators also exist without a norm authority, as interpreting and translating are subject to economic as well as ideological interests. Therefore, those fields need to be regulated by norm authorities which also control the fulfilment of norms by applying sanctions.

Chesterman (1993) names the following norm authorities for the translation profession: “Translation teachers, examiners, translation critics, even professionals who check the drafts of other professionals – all are implicit norm-authorities, who are accepted as having norm-giving competence” (Chesterman 1993: 9). In his listing he omits, however, the norm-giving power of professional associations. In the case of conference interpreting, the International Association of Conference Interpreters (AIIC) is more than just an implicit force in the establishment of norms.

4.1. AIIC (International Association of Conference Interpreters)

On its website AIIC presents itself explicitly as a norm-setting authority in the field of conference interpreting: “AIIC promotes the profession of conference interpretation in the interest of both users and practitioners by setting high standards, promoting sound training practices and fostering professional ethics.”[4] Conference interpreters are obliged to follow the rules and regulations as laid down by the association. The code of ethics and the professional standards in place serve as a form of vademecum for professionals: “To become a member of AIIC, you are expected to observe the association’s rules and regulations.”[5] Non-compliance with the association’s rules and regulations leads to sanctions: “The Council acting in accordance with the Regulation on Disciplinary Procedure shall impose penalties for any breach of the rules of the profession as defined in this Code” (see note 5).

In one of AIIC’s short definitions of conference interpreting, the profession is defined as follows: “Conference interpretation is conveying a message spoken in one language into another. It is practised at international summits, professional seminars, and bilateral or multilateral meetings of heads of State and Government.”[6] In this brief definition, the activity of conference interpreting was purposely simplified as the website is not visited only by the professionals themselves, but also by the interested public and possible clients. Only the essential seems to be given in this definition, i.e., conveying a message from one side to the other. The association, however, also gives more detailed and accurate definitions of the work and duties of a conference interpreter whose primary function seems to be that of absolute loyalty to the speaker and his/her original:

Interpretation is all about understanding what the speaker means in the context of a particular meeting […]. Not only must interpreters understand what the speaker is saying, but they must also be able to transpose the meaning into the target language. […] real professionals will constantly be looking for the meaning that lies beneath the words.[7]

Absolute loyalty to the speaker and his/her original is not only a normative expectation that is directed to the conference interpreter within the system of conference interpreting itself, but also from outside the system. Nevertheless, Diriker (2011) points out a fundamental difference between the normative expectation of “absolute loyalty to the speaker and his/her original” of insiders and that of outsiders to the profession:

While the interpreters and their organisations have carefully underlined the salience of “transferring the meanings intended by the speakers,” the discourse of the outsiders has almost obsessively defined the task of the interpreters as entailing a transfer of the speaker’s words. (Diriker 2011: 29)

AIIC, however, also directs contradicting normative expectations to conference interpreters which inevitably leads to role overload. On the one hand, the association demands absolute loyalty from interpreters, but on the other hand interpreters are also expected to make a speech their own:

It is your job to communicate the speaker’s intended messages as accurately, faithfully, and completely as possible. At the same time make it your own speech, and beclear and lively in your delivery. […] make sense in every sentence […] be not only accurate but convincing.”[8]

Here the question arises as to whether the norm of absolute loyalty would strictly speaking not exclude an immediately intelligible and clear interpretation. The same applies to a lively and convincing interpretation which, however, also has to reflect “the emphasis, tone, and nuance of what is said” (see note 8).

The norm of loyalty towards the speaker also implies the norms of the interpreter’s non-intervention and detachment: “The interpreter must never change or add to the speaker’s message. Furthermore, the interpreter must neverbetray any personal reaction to the speech, be it scepticism, disagreement, or just boredom” (see note 8).

All of the above normative expectations are speech acts and in the imperative. A norm is always presented as if it were the only logical and natural reality that is unquestioned and shared by a certain group of people (Eichner 1981: 43). AIIC presents its vademecum for its members “The practical guide for Professional Conference Interpreters” as something natural and to be accepted as a matter of course by everyone who works professionally: “Naturally, experienced interpreters will find many statements of the obvious, while newcomers may not understand all the reasons behind some of the suggestions. […] A lot of this advice is really just common sense.”[9]

4.2. Conference interpreting pioneers

The primary function of interpreters as professionals who are loyal to the speaker and his/her original by conveying the one and only intended meaning can be traced back to Seleskovitch (1968) and her “théorie du sens.” The process of interpreting is basically comprised of three stages:

Seleskovitch 1968: 35

audition d’un signifiant linguistique chargé de sens; appréhension (domaine de la langue) et compréhension (domaine de la pensée et de la communication) du message par analyse et exégèse;

oubli immédiat et volontaire du signifiant pour ne retenir que l’image mentale du signifié (concepts, idées, etc.);

production d’un nouveau signifiant dans l’autre langue, qui doit répondre à un double impérati f: exprimer tout le message original, et être adapté au destinataire.

The théorie du sens is thus based on the assumptions of objective linguistics and the communication model devised by Shannon and Weaver (1963) which is also founded on the idea of an active source which is responsible for the sense of the message and a passive receiver that decodes this particular message.

Seleskovitch was not only a very influential interpreting researcher and teacher, but also one of the profession’s pioneers who helped promote and professionalize conference interpreting. The théorie du sens was very well received within the circle of conference interpreting pioneers. In the introduction to Seleskovitch’s “L’interprète dans les conférences internationales” (1968), Constantin Andronikof, founder and first president of AIIC, subsumed the function of a conference interpreter as follows: “[…] dire dans une langue ce qui a été dit dans une autre. C’est la logique du plan suivi par la thèse qu’on va lire” (Andronikof 1968: 8).

Furthermore, the interpretative theory was also successfully integrated into conference interpreting pedagogy (Seleskovitch and Lederer 1989). In addition, Seleskovitch herself was among the founding members of AIIC and helped build up the association. All of this may partly explain the success story of the théorie du sens in the fields of interpreting pedagogy and practice. The interpretative theory, however, has been sharply criticized by interpreting researchers as the theory can neither be scientifically proven nor deemed false (Gile 1990; Pöchhacker 1994).

Be that as it may, the main reason for its success among practitioners lies in the simplicity and efficacy of the concept of interpreters as conveyors of the speaker’s intended meaning. It is a concept that is immediately intelligible and an image that can be marketed and sold very well, since the interpreter is presented as a powerless and uninvolved communication agent who therefore appears trustworthy. The concept of interpreters as absolutely loyal, emotionally detached and non-intervening professionals is based on the metaphoric conduit concept (Reddy 1993; Roy 1993). Thus, the normative expectation according to which interpreters should act as a detached conduit or channel by conveying the one and only sense that lies beneath a speaker’s words as completely as possible can be regarded as a type of supernorm that still governs the social system of conference interpreting.

5. Survey on “Quality and Role: The professionals’ view”

The survey on “Quality and Role: The professionals’ view,” of which some selected findings will be presented below, was conducted among the members of AIIC.[10]

Its main objective was to find out whether and to what degree conference interpreters adhere to the supernorm of interpreters as conduits or whether they see themselves in a more active and co-productive position. As norms are culture-, time- and context-bound and thus not stable phenomena, the socio-demographic and -professional background of interpreters was also deemed to have an impact on the (dis)agreement on the supernorm.

5.1. Methods and survey design

The web-based survey was conducted as a full population survey among the members of AIIC in autumn 2008. A personalized link to the survey that could only be used once was sent out via e-mail to all the members of the association who were listed in the printed version of the 2008 AIIC directory. In total, 2523 e-mails were sent out, of which 49 could not be successfully delivered due to mail delivery errors. The survey fielding time was seven weeks (09/22/08 – 11/10/08), including two reminders. The web survey yielded a response rate of 28.5 percent which corresponds to 704 completed questionnaires.

The web-based questionnaire was divided into three main parts. All the survey items referred exclusively to simultaneous conference interpreting. In Part A the conference interpreters’ socio-demographic background variables such as age, gender, working experience, etc. were elicited.

Part B was devoted explicitly to the issue of quality in simultaneous conference interpreting. The beginning of this section was essentially a replication of Bühler (1986) and thus a rating of various output-related quality criteria. Survey respondents were furthermore asked to link the relative importance of the various norms to concrete conference interpreting contexts (Zwischenberger 2010). Part B also contained a web-based experiment for which respondents were asked to listen to a one-minute audio sample of a simultaneous interpretation and give their impressions.

The questionnaire’s longest part, Part C, was dedicated to the simultaneous conference interpreter’s role aspects. The core of this part was 14 role items which were reduced to the four factors or (anti-)normative role constructs of “loyalty towards the speaker/original,” “intervention into the original,” “detachment of the interpreter” and “reaction to working conditions” by means of a statistical factor analysis.

5.2. AIIC interpreters and their socio-demographic and -professional background

Of the 704 conference interpreters who completed and submitted the web-questionnaire, 76 percent were female, and 24 percent were male. Eighty-nine percent were freelance interpreters, whereas only 11 percent indicated that they work as staff interpreters. These ratios closely match the AIIC membership structure as surveyed by Neff (2008).

The average age of AIIC respondents was 52 years, with a minimum of 30 and a maximum of 87 years. Representing 35 percent, the relative majority of AIIC respondents was in the age category of 50 to 59 years, followed by the category from 40 to 49 years which contained 30 percent of survey participants. The average working experience expressed in years among AIIC respondents was 24 years, with a minimum of four and a maximum of 57 years of working experience. Here the relative majority of survey participants was in the category of 20 to 29 years (31.5%), followed by the category from 10 to 19 years of working experience (29%). The average period of affiliation to AIIC was 15 years, with a minimum of one and a maximum of 55 years. These figures tell us that there was at least one founding member or at least a member from the founding year 1953 among the survey participants (Zwischenberger 2011).

As far as the working languages were concerned, the most frequently reported A language was French (24%), closely followed by English (22%) and German (18%). Quite unsurprisingly, English (55%) was the clear leader among B languages, followed by French (27%) and German (9%). The pattern was rather similar for C languages with English (47%) in the lead again, followed by French (43%) and then Spanish (29%) (Pöchhacker and Zwischenberger 2010).

5.3. (Anti-)normative metaconstructs

A total of 14 role-related expectations were reduced to the four (anti-)norms of loyalty towards the speaker/original, intervention into the original, detachment of the interpreter and reaction to working conditions with the help of a statistical factor analysis. The latter construct of reaction to working conditions will not be dealt with here as it is not of direct relevance to the overall discussion of this contribution.

All of the role-related items were to be rated on a six-point metrical scale of which only the extreme poles were verbally anchored (1=completely disagree, 6=completely agree).

The role construct of “loyalty towards the speaker/original,” which is normative in its very essence and explicitly demanded by AIIC in its various metatexts on conference interpreting, can be directly traced back to the conduit supernorm. “Loyalty towards the speaker/original” contains the following four items:

It is always desirable for my interpretation to have the same effect on my listeners as the original speech has on the speaker’s audience;

My interpretation reflects the speaker’s tone and register as closely as possible;

Ensuring that the speaker will be fully understood means also conveying emotions, even if they are not verbalized;

My work as a simultaneous interpreter should attract as little attention as possible.

The role construct of the “detachment of the interpreter” also directly relates to the conduit supernorm as the professional conference interpreter is expected to act as an emotionless channel. The construct includes the following two items:

My professional distance as an interpreter keeps me from being influenced by emotional events in the meeting room;

For the speaker’s feelings to be interpreted they have to be expressed in words.

The role construct of “intervention into the original” is the exact opposite of “loyalty towards the speaker/original” and can therefore be regarded as a kind of “anti-norm” which is not authorized by norm-setting authorities as the construct clashes with the image of the passive channel. It contains the following five items:

I help shape the speaker’s message;

If a speaker’s words clash with cultural conventions I try to moderate them;

When interpreting I use my own language and style;

I try to ensure that my interpretation is intelligible, even if the original is not.

It is my duty to explain culture-specific terms to my listeners.

5.3.1. Factor analysis

A factor analysis is a method frequently employed in economic and social sciences to examine whether certain variables can be reduced to common constructs or factors. The overall objective of such a factor analysis lies in dimension reduction.

However, before certain factors can be extracted, the fulfilment by the factor analytical model of specific preconditions for a given study must be ascertained. In this study, the fit of the entire model or measure of sampling adequacy[11] was 0.685 and is thus high enough to accept the entire model.

Table 1

KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity

Bartlett’s test of sphericity is significant which shows that the variables underlying the factor analytical model actually correlate with each other in the AIIC population. Thus, they can most probably be reduced to common latent background variables or factors.

While the KMO measure of sampling adequacy gives information on the quality or acceptability of the entire model, the MSA (Measure of Sampling Adequacy) values also need to be checked for the acceptability of the single items. Five out of the 14 items showed an MSA value between 0.7 and 0.8 and seven items had an MSA value between 0.6 and 0.7, with the vast majority of items displaying a value very close to 0.7. Only two items revealed an MSA value which was slightly under 0.6. Therefore, the quality of the single items used in this factor analytical model is high enough to integrate all of them into the factor analytical model.

With the factor extraction, a total of four factors were extracted which explains approximately 50% of the overall variance. The four extracted factors were rotated for the actual determination and interpretation process.

The rotated component matrix in Table 2 shows the factors 1, 2, 3 which were interpreted as “intervention into the original,” “loyalty towards the speaker/original” and “detachment of the interpreter,” as well as their single underlying items and their loading coefficients[12] for the three respective factors.

Table 2

Factor loadings

Table 2 shows that “I help shape the speaker’s message” loads the most highly on the anti-normative role construct of “intervention into the original.” Thus, this item reflects the anti-norm the best. The same applies to “Ensuring that the speaker will be fully understood means also conveying emotions, even if they are not verbalized” which loads the most highly on “Loyalty towards the speaker/original” and “My professional distance as an interpreter keeps me from being influenced by emotional events in the meeting room” which loads the most highly on “Detachment of the interpreter.”

5.3.2. Loyalty towards the speaker/original

The following graph shows the level of agreement on the normative construct of “loyalty towards the speaker/original” and its underlying items. Quite unsurprisingly, all four items which reflect this norm received a very high average level of agreement on the scale ranging from 6=completely agree to 1=completely disagree.

Table 3

Average ratings of the items underlying “loyalty towards the speaker/original”

Item 1 in Table 3 did not only receive the highest average degree of agreement of all items underlying “loyalty towards the speaker/original,” but it also received the highest mean of the 14 items to be rated. The median, which is the more stable measure, is even at 6 points. With the overall lowest standard deviation of 0.733 of the 14 role-related items to be rated, that same item also yielded the highest level of consensus regarding its rating among respondents. This comes as no real surprise as the normative expectation “It is always desirable for my interpretation to have the same effect on my listeners as the original speech has on the speaker’s audience” is one of AIIC’s maxims (Déjean Le Féal 1990: 155). There was, however, one perceptive comment in the final field for comments that was very sceptical towards this statement which expresses the concept of interpreters as conduits as does the entire metaconstruct to which it belongs: “Just to say that I disagree about producing the same effect on the listeners as the original on the original audience. Why? Because the two groups are different and will react differently” (AIIC R 25; see note 10).

This first item is closely followed by “My interpretation reflects the speaker’s tone and register as closely as possible.” The standard deviation here is 0.757 which again shows a large consensus among survey participants, while the median is 6. Once more, the item did not only yield the second-highest degree of agreement of the four items that reflect the role construct of “loyalty towards the speaker/original,” but also of the total of all the 14 items to be rated. In the final field for comments one interpreter confessed that fulfilling this normative expectation was not feasible in practice: “Comments: On the question: ‘My interpretation reflects the speaker’s tone and register as closely as possible.” – I wish I could do that all the time, but I have to confess it is very difficult’ (AIIC R 402; see note 10).

Item 3 “Ensuring that the speaker will be fully understood means also conveying emotions, even if they are not verbalized” reveals a mean of 5.22 points, a standard deviation of 1.001 and again a median of 6. This again expresses a very high consensus regarding the rating of this statement underlying “loyalty towards the speaker/original.” The interpreter, however, should not go too far when doing this as expressed in one comment: “We should most definitely convey emotions in the words we interpret, explaining the meaning of cultural jargon […] as best as we can without putting words into the speaker’s mouth” (AIIC R 639; see note 10). The interpreter’s job once again remains being faithful to what was intended by the speaker when interpreting.

Item 4 “My work as a simultaneous conference interpreter should attract as little attention as possible” was the only one of the four items that received a mean and thus an average degree of agreement which was below 5 points. The item also shows the highest standard deviation (1.334) of all the items underlying the norm of “loyalty towards the speaker/original” which also indicates the most dissent regarding attracting as little attention as possible as a simultaneous conference interpreter. Furthermore, it is also the only item of the four which shows a median of 5 points. The item yielded quite a few spontaneous comments. The wish of being visible is, however, expressed rather cautiously: “My work as a simultaneous interpreter […]. I believe in the interpreter’s low profile but sometimes being too transparent can be dangerous” (AIIC R 356; see note 10), “I certainly want to be visible rather than nonexistent but I’m aware I’m not the most important person there and try not to make a nuisance of myself with unreasonable demands or expectations” (AIIC R 516; see note 10), “Do I want my job as an interpreter to attract as little attention as possible? Yes, as little negative attention as possible of course but as much positive attention as possible. I want my listeners to be aware of me as an interpreter and my (hopefully) good work, but naturally I don’t want to intrude in or distort my client’s work” (AIIC R 524; see note 10).

The possible influence of the respondents’ social background on the overall rating of the norm “loyalty towards the speaker/original” was investigated. A single background variable proved to have a significant impact on the rating of this norm.

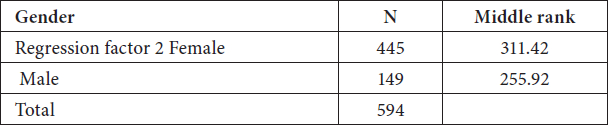

The middle ranks in Table 4 show that female interpreters agreed more highly on the overall construct of being loyal to the speaker/original. This difference proved to be statistically significant in a Mann-Whitney U-test (U=26957; p=0.001<0.05).

Table 4

Influence of the background variable gender on “loyalty towards the speaker/original”

Female conference interpreters thus show a higher tendency to comply with this norm which is so frequently explicitly demanded in the metatexts on conference interpreting. This result is also in line with another finding of the Survey on Quality and Role according to which female interpreters rated the importance of positive feedback coming from the reference group of speakers significantly higher than male interpreters did (Zwischenberger 2013: 286).

Table 5 shows the single ratings for female and male interpreters and proves that women actually gave consistently higher ratings to the single items underlying “loyalty to the speaker/original.”

Table 5

Level of agreement by female and male interpreters on the single items underlying “loyalty towards the speaker/original”

Thus, the norm of “loyalty towards the speaker/original” obviously seems to be more anchored in the habitus of female interpreters than in that of their male colleagues.

5.3.3. Detachment of the interpreter

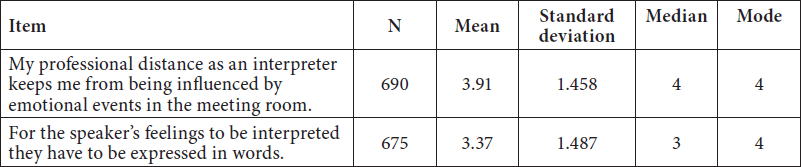

There are two role items which reflect the normative metaconstruct of “detachment of the interpreter.” Table 6 reports the average level of agreement on its two underlying items “My professional distance as an interpreter keeps me from being influenced by emotional events in the meeting room” and “For the speaker’s feelings to be interpreted they have to be expressed in words.” While item 1 received an average level of agreement of almost 4 points, item 2 was rated considerably lower.

Table 6

Average ratings of the items underlying “detachment of the interpreter”

Item 1 in Table 6 reveals a standard deviation of 1.458 and a median of 4. Item 2, however, shows a slightly higher standard deviation of 1.487 and a median of just 3 points. The mode in both cases was 4. On the whole, the data suggests that the normative metaconstruct of the “detachment of the interpreter” seems to be less important than the norm of “loyalty towards the speaker/original.” Thus, the normative construct of the “detachment of the interpreter” may also be less binding than the norm of “loyalty towards the speaker and her/his original.”

A further hint that seems to support this interpretation of the data is the fact that “For the speaker’s feelings to be interpreted they have to be expressed in words” was conceptualized as a control item for the statement “Ensuring that the speaker will be fully understood also means conveying emotions even if they are not verbalized” which belongs to “loyalty of the speaker/original.” The item received an average level of agreement of 5.22 points and was thus rated in a diametrically opposed manner (see section 5.3.2). Control items were used to ascertain the consistency of responses.

One statistically significant influence of the respondents’ socio-demographic background was found. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed that, in sum, the youngest third of respondents agreed statistically significantly the least on being emotionally detached when interpreting (c² (N=582, df=2)=16.765; p=0.000<0.05).

Table 7

Influence of the background variable age on “detachment of the interpreter”

This overall lowest agreement on being emotionally detached when interpreting by the youngest third of respondents (30-47 years) as expressed by the sum of the middle ranks in Table 7 is also confirmed by the rating of the two single items underlying “detachment of the interpreter” in Table 8.

Table 8

Level of agreement by the age groups on the single items underlying “detachment of the interpreter”

The youngest third consistently expressed the lowest degree of agreement on the two items reflecting the interpreter’s detachment.

5.3.4. Intervention into the original

The “anti-norm” of intervention into the original contains five role-related items, of which “I try to ensure that my interpretation is intelligible, even if the original is not” received the highest average level of agreement. It was also the only of the five items which yielded a standard deviation under 1, a median of 6, and a mode of 6.

Table 9

Ratings of the items underlying “intervention into the original”

This result comes as no real surprise as the item reflects one of the most highly rated and ranked parameters for quality in simultaneous interpreting in the various surveys on quality undertaken among users and interpreters since the mid-1980s, namely logical cohesion. In the Survey on Quality and Role: The professionals’ view, this parameter was again rated as the second most important parameter of 11 output-related quality criteria for a simultaneous interpretation (Zwischenberger 2010). There were also a few spontaneous comments which indicate that interpreters seem to feel the need to intervene into the original to improve its intelligibility: “[the interpreter] must do his utmost to render intelligibly an unintelligible message (more often than not)” (AIIC R 203; see note 10), “Logical cohesion depends on the speaker, although we must do our best to improve its logic” (AIIC R 129; see note 10).

The other four items underlying the metaconstruct of “intervention into the original” received much lower average degrees of agreement. Furthermore, they also show very high-standard deviations, indicating that there was a lot of dissent regarding the rating of these statements which reflect an intervention into the original. The item “I help shape the speaker’s message” is in sharp contrast to the metatexts on conference interpreting generated by AIIC (see section 4.1). One of the respondents also felt the need to explicitly specify that the interpreter was by no means the co-creator of sense: “For me to shape the message goes beyond the duty of the interpreter. As a conference interpreter I have to convey the speaker’s message, but I don’t have to shape it…It has already been shaped by the speaker” (AIIC R 631; see note 10).

The anti-normative item “When interpreting I use my own language and style” received the lowest average degree of agreement of all five items forming part of “intervention into the original.” According to the various metatexts produced by the authorities in the field of conference interpreting, the adding of something of one’s own by the interpreter is definitely not acceptable. This item also yielded the second-lowest average degree of agreement of the 14 items that were rated.

The anti-norm “intervention into the original” yielded two statistically significant influences of the respondents’ socio-demographic background. Older and professionally more experienced interpreters agreed the most on intervening in the original in general.

A Kruskal-Wallis test showed that in sum the oldest third of interpreters expressed the highest level of agreement on intervening into an original. The differences among the three age groups proved to be statistically significant (c² (N=582; df=2)= 6.959; p= 0.031<0.05).

Table 10

Influence of the background variable age on “intervention into the original”

As results from Table 10 and the middle ranks show, the agreement rises proportionally with age. The rating of the single items in Table 11 shows that the oldest third indeed expressed the highest degree of agreement overall on intervening into an original.

Table 11

Level of Agreement by the age groups on the single items underlying “intervention into the original”

The same applies to the correlation between the amount of working experience expressed in years and an intervention into the original. Again, the level of agreement rises proportionally with the professional experience of respondents as can be seen in Table 12. A Kruskal-Wallis test shows that the differences among the groups are statistically significant (c² (N=594; df=2)= 10.052; p= 0.007<0.05).

Table 12

Influence of the background variable working experience on “intervention into the original”

The third of respondents with the most working experience expressed the highest agreement on intervening into the original on an overall level. This is also confirmed by the ratings of the single items underlying the anti-norm as can be seen in Table 13.

Table 13

Level of agreement by the working experience groups on the single items underlying “intervention into the original”

The difference among the third with the most working experience and the other two thirds regarding the rating of “I help shape the speaker’s message” is particularly striking, and interpreters with greater experience seem to perceive themselves more as co-creators of a sense.

Generally speaking, the age and working experience of interpreters seem to go hand-in-hand with more self-confidence in handling the communication process: “Of course as you age you realize that completeness is relative – sometimes you do the speaker a kindness by leaving some of the original out” (AIIC R 575; see note 10). This is then further expanded by another spontaneous comment: “Normally not only is [completeness] not essential, but it tends to be counterproductive, forcing the interpreter into inordinate speed (if even when he manages it, will be excruciating for the listener) and the listener to process information that, to him, is totally irrelevant” (AIIC R 203; see note 10).

6. Conclusions

The two norms of “loyalty towards the speaker/original” and “detachment of the interpreter” frequently appear as speech acts in the discourse on conference interpreting produced by AIIC. Both normative expectations can be traced back to the metaphoric concept of interpreters as conduits. Thus, the primary function of a conference interpreter is to act as a passive and emotionless channel which solely has to convey a sense that is inherent in the message as delivered by the speaker. This constitutes an unrealistic oversimplification of the complex roles of an interpreter. This idea in turn is based on the interpretative theory of Seleskovitch (1968). The interpretative theory proved to be very successful in conference interpreting practice and also pedagogy.

AIIC definitely is a norm-setting authority in the field of conference interpreting and explicitly defines the primary task of professional conference interpreters as per the conduit metaphor and demands that its members fulfil this supernorm. The metatexts on conference interpreting produced by AIIC are, however, also full of contradictions. On the one hand the “interpreter as conduit” concept is overemphasized, whilst on the other hand interpreters are also confronted with expectations which collide with this metaphoric concept. The tension created by these contradictions inevitably leads to an overload of the expectations with which the conference interpreter is confronted and also shows that the supernorm is not really tenable in professional practice.

The web-based Survey on Quality and Role: The professionals’ view set out to investigate whether the members of AIIC actually adhere to this supernorm so vehemently demanded by their association. The results of the survey confirm the importance of this supernorm to a large extent. The normative expectation of interpreters as loyal allies of the speaker and her/his original in particular yielded a very high level of agreement and consensus. The results show that being loyal to the speaker and her/his original seems to be more important and may thus also be more binding than being detached when interpreting. The rating of the two norms generally yielded a higher consensus than the rating of anti-normative and thus not-officially-authorized behaviour as represented by the statements underlying an “intervention into the original.” There is, however, one exception. The item which requires an interpreter to produce an intelligible interpretation, even if the original lacks it yielded almost the same consensus and level of approval as the items underlying the norm of “loyalty towards the speaker/original.” The rating of this item which constitutes an intervention into an original reflects the contradictory nature of the entire discourse on conference interpreting as produced by AIIC. The interpreter is expected to be a loyal conduit and yet he/she is also expected to produce an immediately intelligible rendition (section 4.1).

While women appear to be more in line with the supernorm, older and more experienced interpreters seem to be more willing to intervene into the original. The age and working experience of professionals thus seem to go hand-in-hand with a greater reliance on one’s own competences and qualifications when handling the communication process.

Furthermore, in some of the not-directly-solicited metatexts that were generated as comments, the professionals admit that the fulfilment of the supernorm is neither always tenable nor desirable in practice.

The contradictions found in the metatexts produced by AIIC as well as the ones found in the not-directly-solicited data of the Survey on quality and role suggest that the supernorm is not realistic. Yet professional associations like AIIC will keep on propagating the idea of interpreters as conduits since this image can be marketed very well. Notably in the field of conference interpreting, which often is the marketplace of powerful leaders, the image of the uninvolved and passive channel is a welcome one. Adhering to this image, however, also relegates the interpreter to a secondary position – from being a potential partner who takes responsibility in the communication process to being a subordinate who is just there to process information.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

The existence of representative interpreting corpora seems to be a diminishing problem now that the World Wide Web has opened up new possibilities. There is, for example, the large EPIC (European Parliament Interpreting Corpus) corpus which was set up by a research group on corpus-based interpreting studies at the University of Bologna (Bendazzoli and Sandrelli 2005).

-

[2]

As empirical research on prolonged simultaneous interpreting turns shows, this seems to be more of a physiological and psychological necessity than a norm (Moser-Mercer, Künzli et al. 1998).

-

[3]

The web-based Survey on Quality and Role: The professionals’ view was conducted as part of a larger research project on “Quality in Simultaneous Interpreting.” The research project was financed by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and led by Franz Pöchhacker at the Center for Translation Studies, University of Vienna.

-

[4]

AIIC (2010): Introducing AIIC. Visited on 10 February 2014. <http://aiic.net/page/1280>.

-

[5]

AIIC (2009; my emphasis in italics): Code of Professional Ethics. Visited on 10 February 2014,<http://aiic.net/page/54>.

-

[6]

AIIC (2012; my emphasis in italics): Conference Interpreting. Visited on 10 February 2014, <http://aiic.net/page/4003/conference-interpreting/lang/1>.

-

[7]

AIIC (2005; my emphasis in italics): Budding Interpreter FAQ. Visited on 10 February 2014, <http://aiic.net/page/1669>.

-

[8]

AIIC (2004: page 9; my emphasis in italics): Practical Guide for Professional Conference Interpreters. Visited on 10 February 2014, <http://aiic.net/page/628>. file:///C:/Users/p0512104/Downloads/Practical%20Guide%20(PDF).pdf

-

[9]

AIIC (2004: page 1): Practical Guide for Professional Conference Interpreters. Visited on 10 february 2014, <http://aiic.net/page/628>.

-

[10]

In sections 5.3.2, 5.3.3, 5.3.4 and 5.3.5 I directly quote from statements made by survey respondents (referred to as R = respondent followed by the questionnaire’s respective number). The respective emphases in italics were added by me.

-

[11]

The measure of sampling adequacy assumes a value of between 0 and 1.

-

[12]

The loading coefficient assumes a value of between 0 and 1. An item with a loading coefficient under 0.40 should no longer be accepted.

Bibliography

- Andronikof, Constantin (1968): Introduction. In: Danica Seleskovitch. L’interprète dans les conférences internationales, problèmes de langage et de communication. Paris: Lettres modernes Minard: 3-20.

- Angelelli, Claudia V. (2004): Revisiting the Interpreter’s Role: A study of conference, court, and medical interpreters in Canada, Mexico and the United States. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Bendazzoli, Claudio and Sandrelli, Annalisa (2005): An Approach to Corpus-based interpreting studies: Developing EPIC (European Parliament Interpreting Corpus). Visited on 11 February 2014, http://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2005_Proceedings/2005_Bendazzoli_Sandrelli.pdf.

- Bühler, Hildegund (1986): Linguistic (semantic) and extra-linguistic (pragmatic) criteria for the evaluation of conference interpretation and interpreters. Multilingua. 5(4):231-235.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1993): From “Is” to “Ought”: Laws, Norms and Strategies in Translation Studies. Target (1):1-20.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1999): Description, Explanation, Prediction: A Response to Gideon Toury and Theo Hermans. In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation and Norms. Clevedon/Philadelphia/Toronto/Sydney/Johannesburg: Multilingual Matters, 90-97.

- Déjean Le Féal, Carla (1990): Some thoughts on the evaluation of simultaneous interpretation. In: David Bowen and Margareta Bowen, eds. Interpreting – Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Binghampton (NY): Suny, 154-160.

- Diriker, Ebru (1999): Problematizing the discourse on interpreting – A quest for norms in simultaneous interpreting. TextconText. 13(3):73-90.

- Diriker, Ebru (2003): Simultaneous Conference Interpreting in the Turkish printed and electronic media. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 12:231-243.

- Diriker, Ebru (2004): De-/Re-Contextualizing Conference Interpreting: Interpreters in the Ivory Tower. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Diriker, Ebru (2011): Agency in Conference Interpreting: Still a Myth? Gramma. 19:27-36.

- Duflou, Veerle (2007): Norm research in conference interpreting: Some methodological aspects. In: Peter A. Schmitt and Heike E. Jüngst, eds. Translationsqualität. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag, 91-99.

- Eichner, Klaus (1981): Die Entstehung sozialer Normen. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Gile, Daniel (1990): Scientific theories vs. Personal theories in the investigation of interpretation. In: Laura Gran and Christopher Taylor, eds. Aspects of Applied and Experimental Research on Conference Interpretation. Udine: Campanotto Editore, 28-41.

- Gile, Daniel (1999): Norms in Research on Conference Interpreting: A Response to Theo Hermans and Gideon Toury. In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation and Norms. Clevedon/Philadelphia/Toronto/Sydney/Johannesburg: Multilingual Matters, 98-105.

- Harris, Brian (1990): Norms in Interpretation. Target. 2(1):115-119.

- Hermans, Theo (1997): Translation as institution. In: Mary Snell-Hornb, Zuzana JettmaRová and Klaus Kaindl, eds. Translation as Intercultural Communication. Selected Papers from the EST Congress – Prague 1995. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 3-20.

- Marzocchi, Carlo (2005): On Norms and Ethics in the Discourse on Interpreting. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 13:87-107.

- Moser-Mercer, Barbara, Künzli, Alexander and Korac, Marina (1998): Prolonged turns in interpreting. Interpreting. 3(1):47-64.

- Neff, Jacquy (2008): A statistical portrait of AIIC:2005-06. Visited on 11 February 2014, http://aiic.net/page/2887.

- Pöchhacker, Franz (1994): Simultandolmetschen als komplexes Handeln. Tübingen: Narr Verlag.

- Pöchhacker, Franz and Zwischenberger, Cornelia (2010): Survey on Quality and Role: conference interpreters expectations and self-perceptions. Visited on 14 February 2014, http://aiic.net/page/3405/survey-on-quality-and-role-conference-interpreters-expectations-and-self-perceptions/lang/1.

- Popitz, Heinrich (2006): Soziale Normen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Reddy, Michael J. (1993): The conduit metaphor: A case of frame conflict in our language about language. In: Andrew Ortony, ed. Metaphor andThought. 2nd ed. Cambridge: University Press, 164-201.

- Roy, Cynthia B. (1993): The Problem with Definitions, Descriptions, and the Role Metaphors of Interpreters. Journal of Interpretation. 6(1):127-154.

- Schjoldager, Anne (1995/2002): An exploratory study of translational norms in simultaneous interpreting. Methodological reflections. In: Franz Pöchhacker and Miriam Shlesinger, eds. The Interpreting Studies Reader. London/New York: Routledge, 301-311.

- Seleskovitch, Danica (1968): L’interprète dans les conférences internationales, problèmes de langage et de communication. Paris: Minard Lettres Modernes.

- Seleskovitch, Danica and Lederer, Marianne (1989): Pédagogie raisonnée de l’interprétation. Collection Traductologie 4. Luxemburg/Paris: OPOCE and Didier Érudition.

- Shannon, Claude E. and Weaver, Warren (1963): The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Shlesinger, Miriam (1989): Extending the Theory of Translation to Interpretation: Norms as a Case in point. Target. 1(1):111-115.

- Shlesinger, Miriam (1999): Norms, Strategies and Constraints. How do we tell them apart? In: Alberto Álvarez Lugrís and Anxo Fernández Ocampo, eds. Anovar/Anosar estudios de traducción e interpretación. Vigo: Servicio de Publicacións da Universidade de Vigo, 65-77.

- Toury, Gideon (1980): In Search of a Theory of Translation. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute of Poetics and Semiotics.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Toury, Gideon (1999): A Handful of Paragraphs on “Translation” and “Norms.” In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation and Norms. Clevedon/Philadelphia/Toronto/Sydney/Johannesburg: Multilingual Matters, 9-31.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia (2010): Quality criteria in simultaneous interpreting: an international vs. a national view. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 15:127-142.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia (2011): Conference interpreters and their self-representation: A worldwide web-based survey. In: Rakefet Sela-Sheffy and Miriam Shlesinger, eds. Identity and Status in the Translational Professions. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 119-134.

- Zwischenberger, Cornelia (2013): Qualität und Rollenbilder beim simultanen Konferenzdolmetschen. Berlin: Frank & Timme Verlag.

List of tables

Table 1

KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity

Table 2

Factor loadings

Table 3

Average ratings of the items underlying “loyalty towards the speaker/original”

Table 4

Influence of the background variable gender on “loyalty towards the speaker/original”

Table 5

Level of agreement by female and male interpreters on the single items underlying “loyalty towards the speaker/original”

Table 6

Average ratings of the items underlying “detachment of the interpreter”

Table 7

Influence of the background variable age on “detachment of the interpreter”

Table 8

Level of agreement by the age groups on the single items underlying “detachment of the interpreter”

Table 9

Ratings of the items underlying “intervention into the original”

Table 10

Influence of the background variable age on “intervention into the original”

Table 11

Level of Agreement by the age groups on the single items underlying “intervention into the original”

Table 12

Influence of the background variable working experience on “intervention into the original”

Table 13

Level of agreement by the working experience groups on the single items underlying “intervention into the original”